Abstract

The aim of the study was to determine the effect of repeated hot thermal stress and cold water immersion on the endocrine system of young adult men with moderate and high levels of physical activity (PA). The research was conducted on 30 men aged 19–26 years (mean: 22.67 ± 2.02) who attended four sauna sessions of 12 min each (temperature: 90−91°C; relative humidity: 14–16 %). Each sauna session was followed by a 6-min cool-down break during which the participants were immersed in cold water (10−11°C) for 1 min. Testosterone (TES), cortisol (COR), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), and prolactin (PRL) levels were measured before and after the sauna bath. The participants’ PA levels were evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Serum COR levels decreased significantly (p < .001) from 13.61 to 9.67 µg/ml during 72 min of sauna treatment. No significant changes (p >.05) were noted in the concentrations of the remaining hormones: TES increased from 4.04 to 4.24 ng/ml, DHEA-S decreased from 357.5 to 356.82 µg/ml, and PRL decreased from 14.50 to 13.71 ng/ml. After sauna, a greater decrease in COR concentrations was observed in males with higher baseline COR levels, whereas only a minor decrease was noted in participants with very low baseline COR values (r =−0.673, p <.001). Repeated use of Finnish sauna induces a significant decrease in COR concentrations, but does not cause significant changes in TES, DHEA-S, or PRL levels. Testosterone concentrations were higher in men characterized by higher levels of PA, both before and after the sauna bath.

Keywords: Finnish sauna, thermal stress, physically active men, testosterone, cortisol, prolactin, DHEA-S

Introduction

Finnish sauna bathing involves brief exposure to high environmental temperature (80°C–100°C), and it has long been used for pleasure, wellness, and relaxation (Laukkanen et al., 2018). There is ample evidence to suggest that regular sauna use by healthy individuals, persons with health problems and athletes exerts beneficial effects as a form of heat therapy and biological regeneration (Biro Masuda et al., 2003; Pilch et al., 2014; Podstawski et al., 2016; Scoon et al., 2007; Sutkowy et al., 2017). Regular sauna bathing may alleviate and prevent the risk of both acute and chronic diseases (Laukkanen et al., 2019). Emerging evidence suggests that sauna bathing delivers numerous health benefits by lowering the risk of vascular diseases such as high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and neurocognitive diseases, as well as nonvascular conditions, including pulmonary diseases such as the common flu. Sauna bathing reduces mortality, contributes to the treatment of specific skin conditions, and alleviates pain in conditions such as rheumatic diseases and headache (Heinonen & Laukkanen, 2018; Hussain & Cohen, 2018; Laukkanen et al., 2018; Laukkanen & Laukkanen, 2018).

Podstawski et al. (2013) demonstrated that a visit to the sauna can be a stressful experience for people who are rarely subjected to heat therapy. In the cited study, sauna bathing significantly contributed to the psychological and physical well-being of the vast majority of the participants, leaving them refreshed and relaxed. In the studied population, 23.70% of males and 14.93% of females experienced discomfort due to high temperature, a large number of participants, and the presence of the opposite sex (Podstawski et al., 2013). These findings suggest that the stress associated with sauna use can lead to changes in hormone secretion, and similar observations have been made by other researchers (Rissanen et al., 2019). Some of these changes resemble the processes that occur in response to other stressors, whereas other changes are typical of sauna-induced stress (Kukkonen-Harjula & Kauppinen, 1988). Stress activates the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal hormonal axis to maintain thermal balance in the body (Kauppinen & Vuori, 1986; Kukkonen-Harjula & Kauppinen, 1988). Hormones are chemical transmitters that participate in numerous physiological processes. The production of some hormones increases during physiological stress when physical effort exceeds the body’s regulatory capabilities and induces an excessive response that triggers neurohormonal changes (Jaskólski & Jaskólska, 2006). Elevated blood pressure and sweating during sauna trigger a number of responses and activate mechanisms that are responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis. The production of the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and aldosterone is intensified to normalize blood pressure (Hannuksela & Ellahham, 2001; Kauppinen, 1989). Kosunen et al. (1976) and Lammintausta et al. (1976) observed an increase in the plasma concentrations of renin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone during a single sauna session.

The group of hormones that regulate physiological processes during thermal stress involves steroid hormones that are fat-soluble and can easily cross cell membranes. These hormones include cortisol (COR), testosterone (TES) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S). Steroids penetrate cells and bind to the cell nucleus. The time of day should also be carefully planned in experimental loading protocols because serum COR, TES and DHEA-S concentrations change during the day in the circadian rhythm (Rissanen et al., 2019). The hormone-receptor complex then binds to DNA and activates the genes responsible for the production of specific proteins and enzymes (Jaskólski & Jaskólska, 2006). Prolactin (PRL) is yet another multi-functional hormone whose biological potency probably exceeds the combined effects of the remaining pituitary hormones. Prolactin is positively associated with ambient temperature, which could imply that it is involved in acclimatory responses to higher ambient temperature (Cicioglu & Kiyici, 2013) and that its secretion increases significantly under stress conditions (physical exertion, hypoglycemia or dehydration) in both men and women (Lennartsson & Jonsdottir, 2011). A positive correlation between body temperature and PRL secretion was reported by Christensen, Jørgensen, Møller, Møller, and Orskov (1985), whereas Lammintausta et al. (1976) observed a significant decrease in sodium excretion from the body during and after heat exposure in the sauna.

The hormonal system strongly affects the thermoregulatory system, and a number of hormonal changes occur under thermal stress. These changes are particularly pronounced in individuals who are not frequent sauna users (Pilch et al., 2003). During thermal stress, hormone production is altered to adapt to the demand for energy, and it responds to the amount of body water and body temperature. These processes are particularly important in persons who exposed to thermal stress and are at greater risk of dehydration or overheating (Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness, 2005). Stable levels of body water (approximately 60% of body mass in adult men) and stable body temperature are required for healthy circulation and many physiological processes (Mayer & Bar-Or, 1994; Sawka, 1992). Research on the effects of thermal stress in men who use the sauna sporadically demonstrated an increase in the heart rate to the maximum values, in particular during prolonged and repeated sauna sessions lasting 40 min and longer (temperature ˃ 90°C, humidity approx. 15%) (Podstawski et al., 2019). During repeated sauna exposure, a strong relationship was also noted between body mass loss, body surface area and heart rate response in healthy adult males (Boraczyński et al., 2018).

There is a general scarcity of published studies investigating the impact of thermal stress on hormonal changes in men with different physical activity (PA) levels who are regular sauna users. There is evidence to indicate that PA significantly influences hormone levels in the human body (Hagobian & Braun, 2010; Poehlman & Copeland, 1990). According to Kukkonen-Harjula and Kauppinen (2006), sauna is an ancient habit in both cold and warm climates, which is why cooling factors such as cooling time, temperature and the cooling environment (water or air) should be taken into account when analyzing changes in the hormonal milieu. The aim of this study was to analyze the basic responses of the endocrine system in young healthy men with moderate and high levels of PA, who were exposed to heat during four 12-min sessions in a Finnish sauna. Each sauna session was followed by a 6-minute break during which the participants were immersed in cold water for 1 min.

Materials and Methods

Participant Selection

The study was conducted in 2020 on 30 male volunteers aged 19–26 years (22.67 ± 2.02). The prospective participants were informed about the purpose of the study during a meeting held 2 months before the experiment at the University of Warmia and Mazury (UWM) in Olsztyn, Poland. The students who agreed to participate in the study (47 men) were notified by e-mail and a text message whether they met the inclusion criteria and were provided with the date of final recruitment. The planned sauna sessions were relatively long, and the volunteers were asked to visit a sauna regularly (twice a week for 30 min) for 2 months before the study. For this purpose, the prospective subjects were provided with access to two saunas in the UWM in Olsztyn (twice a week on specified days of the week) over a period of 2 months preceding the study. Thirty students meeting the above inclusion criteria were recruited for the study. The participants confirmed that they did not take any medications or nutritional supplements, were in good health, and had no history of blood diseases or diseases affecting biochemical and biomechanical factors. None of the evaluated participants had respiratory or circulatory ailments.

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted upon the prior consent of the Ethics Committee of the UWM in Olsztyn (10/2020), according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study was performed on student volunteers who signed an informed consent statement.

Instruments and Procedures

The participants received comprehensive information about sauna rules during the meeting preceding the study. They were asked to drink at least 1 L of water on the day of the test and 0.5 L of water 2 hr before the session. The participants did not consume any foods or other fluids until after the final body measurements.

The participants’ PA levels were evaluated using the standardized and validated International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (Lee et al., 2011). The IPAQ was used only to select a homogenous sample of male students, and the results were presented only in terms of Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) units indicative of the participants’ PA levels. The students declared the number of minutes dedicated to PA (minimum 10 min) during an average week preceding the study. The energy expenditure associated with weekly PA levels was expressed in MET units. The MET is the ratio of the work metabolic rate to the resting metabolic rate, and 1 MET denotes the amount of oxygen consumed in 1 min at rest, which is estimated at 3.5 mL/kg/min. Based on the frequency, intensity and duration of the PA levels declared by the surveyed students, the respondents were classified into groups characterized by low (L < 600 METs-min/week), moderate (M < 1,500 METs-min/ week) and high (H ≥ 1,500 METs-min/week) levels of activity. Only male students with moderate and high levels of PA (energy expenditure over 600 METs per week) were chosen for the study. All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in the study

All participants visited a dry sauna during the same time of day (between 8:00 and 10:00), in the same location and over the same period of time to minimize the effect of diurnal variation on the results (Valdez et al., 2007). Every participant attended four sauna sessions (temperature: 90°C; relative humidity: 14%–16%) of 12 min each, and remained in a sitting position during each session. After every 12-min session, the students recovered in a neutral room (temperature of 18°C and humidity 50%–55%) in a sitting position. Each of the four recovery sessions lasted 6 min, during which the participants were immersed in a paddling pool (pool width: 100 cm; pool depth: 130 cm; water temperature: +10–11°C). Air temperature and humidity inside the sauna cabin and the neutral room, and the temperature of water in the paddling pool were measured with the Voltcraft BL-20 TRH + FM-200 hygrometer (Germany) and confirmed with the Stalgast 620711 laser thermometer (Poland).

Blood for analysis was sampled from the median cubital vein. Body temperature was measured with a non-contact laser thermometer (Stalgast 620711, Poland) before blood sampling. Blood samples of around 10 ml each were collected into vials with a clot activator. The serum was separated from blood cells by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min. Serum hormone levels were determined. The concentrations of the analyzed hormones were assessed in the electro-chemiluminescence assay (ECLIA) in the Cobas 6000 system with the E601 module (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). Cortisol was separated from endogenous binding proteins, and its concentration was determined with a specific anti-cortisol polyclonal antibody (measurement range: 0.5 to 1750 nmol/L; expected morning concentration between 7 and 10 a.m.: 19.4 µg/ml). Testosterone levels were determined in the competitive ELISA test with a specific anti-testosterone monoclonal antibody (measurement range: 0.069–52.00 nmol/L; expected values: 2.85–8.02 ng/ml). The concentration of PRL II was assayed in the competitive ELISA test with a specific anti-human prolactin monoclonal antibody (measurement range: 1–10,000 ulU/mL; expected values: 5.0 – 20.0 ng/ml). The concentration of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA-S) was determined with a specific rabbit anti-DHEA-S polyclonal antibody. Endogenous DHEA-S and the DHEA-S derivative labeled with a ruthenium complex compete for the binding sites on the antibody (measurement range: 0.100–1000 µg/dL; expected values: 200–900 µ/dL).

Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive statistics (mean, SD and range of variation) were calculated for each of the four hormones, and the normality of distribution (asymmetry coefficient) was examined. All tested parameters had normal distribution, and the Student’s t-test for dependent samples was used to assess the significance of differences between the arithmetic means of hormone levels before and after sauna. The relationships between the studied variables were assessed by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficient r. The calculations were performed using Statistica ver. 10 software at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

The average MET was determined at 1487.73 ± 184.72 (1190–1782), which is indicative of moderate PA levels. In the group of the examined volunteers, 19 participants were characterized by moderate PA levels and 11 participants—by high PA levels.

A significant (p < .001) decrease in serum COR levels (from 13.61 to 9.67 µg/ml) was noted during four 12-min sauna sessions separated by four 6-min breaks. No significant changes were observed in the concentrations of the remaining hormones (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Hormone Levels Before and After Sauna (N = 30).

| Hormones | Before sauna | After sauna | Difference (B-A) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min–Max | As | Mean | SD | Min–Max | As | t | p | |

| Testosterone (ng/ml) | 4.04 | 1.11 | 2.03–5.97 | −0.13 | 4.25 | 1.41 | 1.55–7.84 | 0.59 | −0.628 | ns |

| Cortisol (µg/ml) | 13.61 | 4.38 | 4.50–19.91 | −0.42 | 9.67 | 3.30 | 3.95–16.76 | 0.38 | 6.03 | <.001 |

| DHEA-S (µg/ml) | 357.50 | 168.87 | 148.20–780.00 | 1.06 | 356.82 | 183.14 | 148.20–860.60 | 1.31 | 0.015 | ns |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 14.50 | 5.35 | 6.80–29.70 | 0.94 | 13.71 | 7.05 | 3.90–33.30 | 0.98 | 0.487 | ns |

Note: ns, not significant.

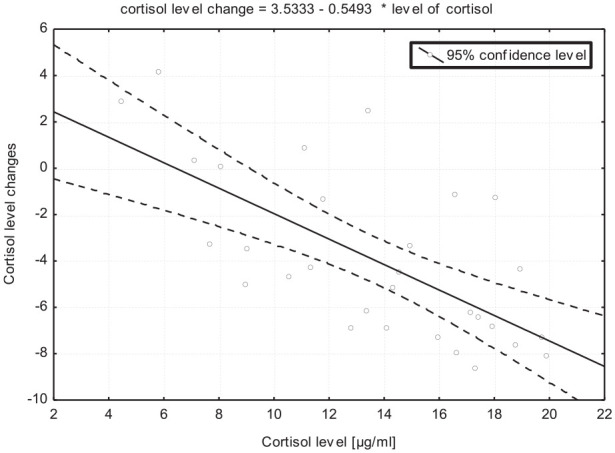

An analysis of the relationship between baseline COR levels and post-sauna concentrations of this hormone produced interesting results (Fig. 1). The correlation coefficient (–0.673) demonstrated that these parameters were bound by a significant (p < .001) negative correlation, which indicates that the higher the baseline COR level, the greater the decrease in COR concentrations after sauna. After the sauna treatment, a very small decrease in COR concentrations was noted in men with very low baseline COR levels, and a minor increase or no change in COR concentrations were observed in four subjects.

Figure 1.

Correlation diagram of changes in cortisol levels before and during sauna.

The relationships between different hormone concentrations before and after sauna and changes in these relationships in view of the participants’ PA levels (expressed in MET units) are presented in Table 2. Men with higher PA levels were characterized by significantly higher TES concentrations both before and after sauna. No significant relationships were found for the remaining hormones (COR, PRL, and DHEA-S) or their changes during the sauna treatment.

Table 2.

Correlation Coefficients of Hormone Levels Before and After sauna, Changes in Hormone Levels During the Sauna Bath, and MET Values.

| Hormones | Before sauna | After sauna | Changes during sauna | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone (ng/ml) | r | .83 | .58 | −.13 |

| p | <.001 | .001 | ns | |

| Cortisol (µg/ml) | r | −.03 | −.32 | −.26 |

| p | ns | ns | ns | |

| DHEA-S (µg/ml) | r | −.07 | −.10 | −.11 |

| p | ns | ns | ns | |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | r | .06 | −.02 | −.08 |

| p | ns | ns | ns | |

Note: ns, not significant.

Discussion

The present study revealed two interesting phenomena in the examined men. Firstly, an analysis of men characterized by moderate and high PA levels demonstrated that the latter had significantly higher serum TES concentrations. According to Foss and Keteyian (1997), TES concentrations increase with the duration of physical effort, but training-induced changes in TES levels have not been fully elucidated. A highly significant increase in mean plasma TES (21%) was observed during 6 months of physical training, and it was associated with a mean 16% increase in the estimated maximal oxygen uptake. In a study by Remes et al. (1979), the mean increase in hormone levels tended to be greater in the well-conditioned group than in the poorly conditioned group of army recruits. Significant differences in TES concentrations were also reported by Ari et al. (2004) between men who exercised regularly (8.3 ± 1.3 ng/mL) and the control group of sedentary males (5.4 ± 1.7 ng/mL). In men, the increase in TES is particularly important for resistance-induced adaptations (Vingren et al., 2010), but a very high and rapid increase in serum TES and COR levels was reported immediately after high-intensity endurance exercise (Kreamer et al., 1995). Rissanen et al. (2019) investigated acute neuromuscular and hormonal responses to endurance, strength, and combined endurance and strength exercise, followed by a 30-minute session in a traditional sauna bath (70° C, 18% relative humidity), and their effects on neuromuscular performance and serum hormone concentrations (TES, COR and growth hormone - GH22kD). They found that high-intensity strength exercise followed by sauna exerted a greater strain on neuromuscular performance than high-intensity endurance exercise or combined endurance and strength exercise followed by sauna. Serum COR, TES, and GH22kD levels increased after high-intensity exercise, but further changes in hormone concentrations were not observed at the end of the sauna session (Rissanen et al., 2019).

Testosterone is associated with multiple physiological functions in the human body. In males, TES is produced and secreted mainly by the Leydig cells of the testes (Brownlee et al., 2005). In physically active individuals, TES is especially important for the growth and maintenance of skeletal muscles, bones, and red blood cells (Zitzmann & Nieschlag, 2001). Plasma TES concentrations during the sauna bath did not change in the studies conducted by Leppäluoto et al. (1986) and Kukkonen-Harjula et al. (1989). In turn, Kukkonen-Harjula and Kauppinen (1988) demonstrated sauna-induced changes in TES secretion. Testosterone plays a key role in triggering and maintaining sexual functions in males, and there is no scientific evidence to indicate that regular sauna bathing reduces male fertility (Kukkonen-Harjula & Kauppinen, 2006).

The current study investigated the mutual interactions between TES and COR. Similarly to COR, TES increases linearly in response to exercise stress once a specific intensity threshold is reached, and its levels generally peak at the end of exercise (Wilkerson et al., 1980). Testosterone and COR levels can increase significantly even during low intensity exercise that is sufficiently prolonged (Brownlee et al., 2005; Väänänen et al., 2002). COR is a catabolic hormone that is secreted by the adrenal cortex in response to physiological stress. While COR increases during exercise, most of the changes and effects associated with this hormone occur after exercise in the early recovery phase (Daly et al., 2005). Cortisol affects metabolism by maintaining blood glucose levels at a sufficiently high level during physiological stress. Cortisol exerts this effect by mobilizing amino acids and lipids in skeletal muscles and adipose tissue (Galbo, 2001). Previous research revealed a negative relationship between COR and TES under certain circumstances. Cumming et al. (1983) reported that an increase in the pharmacological doses of COR decreased TES production in humans. Nindl et al. (2001), Daly et al. (2005) and Brownlee et al. (2005) confirmed the presence of a relationship between COR and TES during sample recovery, which could suggest that a critical concentration of COR has to be achieved in order to substantially influence circulating TES levels. The present study did not reveal any interactions between TES and COR. Serum COR levels decreased significantly, whereas a significant increase in TES was not observed during repeated thermal stress and cold water immersion. A greater decrease in serum COR was noted in men with higher baseline COR levels, whereas the decrease observed in men with lower baseline COR levels was significantly smaller. The above could indicate that intermittent exposure to hot and cold stress partially stabilizes blood COR levels and alleviates stress in men who are regular sauna users. In research dedicated to thermal stress, COR levels remained unchanged in the experiments performed by Latikainen et al. (1988) and Jokinen et al. (1991); they decreased by 10%–40% in the work of Leppäluoto et al. (1986) and Kukkonen-Harjula et al. (1989), and increased 1.5- to 3-fold in the highest number of published studies (Jezova et al., 1994; Kauppinen et al., 1989; Kukkonen-Harjula et al., 1989; Pilch et al., 2003, 2007, 2013; Vescovi et al., 1997). In the current study, COR levels decreased during repeated hot and cold treatment, which contradicts the results reported by Kauppinen et al. (1989) who observed an increase in COR concentrations during combined sauna treatment, in particular with ice-water immersion. Cooling parameters were not described in detail by the cited authors. In the present study, a significant decrease in COR levels could suggest that users who regularly use the sauna (twice a week) are accustomed to extreme changes in temperature. It should be noted that the temperature of the paddling pool was 10-11°C. Other studies demonstrated a less significant increase in COR levels in young women on day 14 of daily sauna use, which suggests that the body becomes familiarized with a hot environment (Pilch et al., 2003, 2007). An increase in COR concentrations is considered a sensitive indicator of a stress reaction and intolerance of heat, which is most frequently reported in infrequent or first-time sauna users (Follenius et al., 1982).

Cumming et al. (1983) reported similar PRL concentrations to those noted in this study. The cited authors did not observe significant changes in PRL levels during physical stress. In most studies investigating the effects of sauna on the hormonal system, PRL levels increased 2- to 10-fold (Jezova et al., 1994; Jokinen et al., 1991; Kukkonen-Harjula et al., 1989; Latikainen et al., 1988; Leppäluoto et al., 1986; Sirviö et al., 1987 Vescovi et al., 1990, 1992). The influence of thermal stress on changes in DHEA-S concentrations has not been studied to date. DHEA-S sulfate plays a key role in stimulating TES secretion. In the present study, only a non-significant increase in TESe levels was observed. A DHEA-S deficiency can be manifested by low energy and increased sensitivity to thermal pain (Yamamotová et al., 2012). DHEA-S levels in the blood decrease with age, which is why this compound is referred to as the youth hormone.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. The relationships in subgroups (with different PA levels) could not be broadly assessed due the limited number of participants in each subgroup. The results could not be extrapolated to women. A reference group of men with no history of sauna use was not available. Therefore, further research is needed to confirm the effects of repeated sauna-induced thermal stress on specific hormones and the relationships between different hormones (such as the T/C ratio). The mechanisms underlying these responses should be investigated in greater detail in a larger population involving both sexes and a higher number of sauna sessions.

Conclusions

In young men, TES concentrations increase significantly with increasing PA levels, whereas such relationships are not observed in the concentrations of COR, PRL, or DHEA-S. Repeated exposure to hot and cold thermal stress significantly decreases COR levels in young men who are regular sauna users, but it does not induce significant changes in the concentrations of TES, PRL, or DHEA-S. A decrease in serum COR levels could indicate that sauna therapy combined with cold water immersion has a relaxing effect on men.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all students who volunteered for the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The funding for this research received from the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn does not lead to any conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Robert Podstawski  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1492-252X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1492-252X

References

- Ari Z., Kutlu N., Uyanik B. S., Taneli F., Buyukyazi G., Tavli T. (2004). Serum testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor-1 levels, mental reaction time, and maximal aerobic exercise in sedentary and long-term physically trained elderly males. International Journal of Neuroscience, 114(5), 623–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro S., Masuda A., Kihara T., Tei C. (2003). Clinical implications of thermal therapy in lifestyle-related diseases. Experimental Biology & Medicine, 228, 1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraczyński T., Boraczyński M., Podstawski R., Borysławski K., Jankowski K. (2018). Body mass loss in dry sauna and heart rate response to heat stress. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 24(4), 258–262. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee K. K., Moore A. W., Hackney A. C. (2005). Relationship between circulating cortisol and testosterone: influence of physical exercise. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 4, 76–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen S. E., Jørgensen O., Møller J., Møller N., Orskov H. (1985). Body temperature elevation, exercise and serum prolactin concentrations. Acta Endocrinologica (Copenh), 109(4), 458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicioglu Í., Kiyici F. (2013). Plasma growth hormone and prolactin levels in healthy sedentary young men after short-term endurance training under hot environment. Montenegrin Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 2(2), 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness (2005). Promotion of healthy weight control in young athletes. Pediatrics, 116, 1557–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming D. C., Quigley M. E., Yen S. C. (1983). Acute suppression of circulating testosterone levels by cortisol in men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 57, 671–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly W., Seegers C., Rubin D. A., Dobridge J. D., Hackney A. C. (2005). Relationship between stress hormones and testosterone with prolonged endurance exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 93, 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follenius M., Brandenberger G., Oyono S., Candas V. (1982). Cortisol as a sensitive index of heat-intolerance. Physiology & Behaviour, 29, 509–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss M. L., Keteyian S. J. (1998). Fox’s physiology basis for exercise and sport. WCB/McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Galbo H. (2001). Influence of aging and exercise on endocrine function. International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism (Suppl.), 11, S49–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagobian T. A., Braun B. (2010). Physical activity and hormonal regulation of appetite: Sex differences and weight control. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 2010, 38(1), 25–30. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181c5cd98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannuksela M. L., Ellahham S. (2001). Benefits and risk of sauna bathing. American Journal of Medicine, 110, 118–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen I., Laukkanen J. A. (2018). Effects of heat and cold on health, with special reference to Finnish sauna bathing. American Journal Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 314, R629–R638. doi:10/1152/ajpregu.00115.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain J., Cohen M. (2018). Clinical effects of regular dry sauna bathing: A systematic review. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Article Volume 2018, Article ID 1857413, 30 pages, 10.1155/2018/1857413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskólski A., Jaskólska A. (2006). Wysiłek a hormony. In Jaskólski A., Jaskólska A. (Eds.), Podstawy fizjologii wysiłku fizycznego z zarysem fizjologii człowieka (pp. 210–227). PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Jezová D., Kvestnanský R., Vigaš M. (1994). Sex differences in endocrine response to hyperthermia in sauna. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 150(3), 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen E., Välimäki I., Marniemi J., Seppänen A., Irjala K., Simell O. (1991). Children in sauna: hormonal adjustments to intensive short thermal stress. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 142, 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen K. (1989). Sauna, shower, and ice water immersion. Physiological responses to brief exposure to heat, cool, and cold. Part I. Body fluid balance. Arctic Medical Research, 48(2), 55–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen K., Pajari-Backas M., Volin P., Vakkuri O. (1989). Some endocrine responses to sauna, shower and ice water immersion. Arctic Medical Research, 48, 131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen K., Vuori I. (1986). Man in the sauna. Review article. Annales of Clinical Research, 18, 173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen-Harjula K., Kauppinen K. (2006). Health effects and risks of sauna bathing. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 65(3), 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen-Harjula K., Kauppinen K. (1988). How the sauna affects the endocrine system. Annales of Clinical Research, 20, 262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen-Harjula K., Oja P., Laustiola K., Vuori I., Jolkkonen J., Siitonen S., Vapaatalo H. (1989). Hemodynamic and hormonal responses to heat exposure in a Finnish sauna bath. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 58, 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosunen K., Pakarinen J., Kuoppasalmi K., Adlercreutz H. (1976). Plasma renin activity, angiotensin II and aldosterone during intense heat stress. Journal of Applied Physiology, 41, 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreamer W. J., Patton J. F., Gordon S. E., Harman E. A., Deschenes M. R., Reynolds K., Dziados J.E. (1995). Compatibility of high-intensity strength and endurance training on hormonal and skeletal muscle adaptations. Journal of Applied Physiology, 78(3), 976–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammintausta R., Syvälahti E., Pekkarinen A. (1976). Change in hormones reflecting sympathetic activity in the Finnish sauna. Annals of Clinical Research, 8, 266–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latikainen T., Salminen K., Kohvakka A., Petersson J. (1988). Response of plasma endorphins, prolaction and catecholamines in women to intense heat in sauna. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 57, 98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen J. A., Laukkanen T., Kunutsor S. K. (2018). Cardiovascular and other health benefits of sauna bathing: a review of the evidence. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 93(8), 1111–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen T., Lipponen J., Kunutsor S. K., Zaccardi F., Araújo C. G. S., Mäkikallio T. H., Laukkanen J.A. (2019). Recovery from sauna bathing favorably modulates cardiac autonomic nervous system. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 45, 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. H., Macfarlane D. J., Lam T. H., Stewart S. M. (2011). Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8, 115. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennartsson A-K., Jonsdottir I. H. (2011). Prolactin in response to acute psychosocial stress in healthy men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(10), 1530–1539. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppäluoto J., Huttunen P., Hirvonen J., Väänänen A., Tuominen M., Vuori J. (1986). Endocrine effects of repeated sauna bathing. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 128, 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F., Bar-Or O. (1994). Fluid and electrolyte loss during exercise: the pediatric angle. Sports Medicine, 18, 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nindl B. C., Kraemer W. J., Deaver D. R., Peters J. L., Marx J. O., Heckman J. T., Loomis G. A. (2001). LH secretion and testosterone concentrations are blunted after resistance exercise in men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 91, 1251–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilch W., Szyguła Z., Pałka T., Pilch P., Cison P., Wiecha S., Tota Ł. (2014). Comparison of physiological reactions and physiological strain in healthy men under heat stress in dry and steam heat saunas. Biology of Sport, 31, 145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilch W., Szyguła Z., Torii M. (2007). Effect of the sauna-induced thermal stimuli of various intensity on the thermal and hormonal metabolism in women. Biology of Sport, 24(4), 357–373. [Google Scholar]

- Pilch W., Pokora I., Szyguła Z., Pałka T., Pilch P., Cisoń T., Wiecha Sz. (2013). Effect of a single Finnish sauna session on white blood cell profile and cortisol levels in athletes and non-athletes. Journal of Human Kinetics, 39, 127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilch W., Szyguła Z., Zychowska M., Gawinek M. (2003). The influence of sauna training on the hormonal system of young women. Journal of Human Kinetics, 9, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Podstawski R., Boraczyński T., Boraczyński M., Choszcz D., Mańkowski S., Markowski P. (2016). Sauna-induced body mass loss in physically inactive young women and men. Biomedical Human Kinetics, 8(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Podstawski R., Borysławski K., Clark C. C. T., Choszcz D., Finn K. J., Gronek P. (2019). Correlations between repeated use of dry sauna for 4 x 10 minutes, physiological parameters, anthropometric features, and body composition in young sedentary and overweight men: Health implications. BioMed Research International, Volume 2019, Article ID 7535140, 13 pages, 10.1155/2019/7535140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podstawski R., Honkanen A., Tuohino A., Kolankowska E. (2013). Recreational-health use of saunas by 10-20-year old Polish university students. Journal of Asian Scientific Research, 2013, 3(9), 910–923. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlman E. T., Copeland K. C. (1990). Influence of physical activity on insulin-like growth factor-I in healthy younger and older men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 71(6), 1468–1473. 10.1210/jcem-71-6-1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen A., Häkkinen A., Laukkanen J., Kraemer W. J., Häkkinen K. (2019). Acute neuromuscular and hormonal responses to different exercise loadings followed by a sauna. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(2), 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remes K., Kuoppasalmi K., Adlercreutz H. (1979). Effect of long-term physical training on plasma testosterone, androstenedione, luteinizing hormone and sex-hormone-binding globulin capacity. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation, 39(8), 743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawka M. N. (1992). Physiological consequences of hypohydration: exercise performance and thermoregulation. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 24, 657–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoon G. S., Hopkins W. G., Mayhew S., Cotter J. D. (2007). Effects of post -exercise sauna bathing on the endurance performance of competitive male runners. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 10, 259–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirviö J., Jolkkonen J., Pitkänen A. (1987). Adenohypophysis hormones levels during hyperthermia. Revue Roumaine d’Endocrinologie, 25, 21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez P., Ramírez C., García A., Talamantes J., Cortez J. (2007). Circadian and homeostatic variation in sustained attention. Chronobiology International, 27(2), 393–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutkowy P., Woźniak A., Boraczyński T., Boraczyński M., Mila-Kierzenkowska C. (2017). The oxidant-antioxidant equilibrium, activities of selected lysosomal enzymes and activity of acute phase protein in peripheral blood of 18-year-old football players after aerobic cycle ergometer test combined with ice-water immersion or recovery at room temperature. Cryobiology, 74, 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Väänänen I., Vasankari T., Mäntysaari M., Vihko V. (2002). Hormonal responses to daily strenuous walking during 4 successive days. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 88, 122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi P. P., Casti A., Michelini M., Maninetti L., Pedrazzoni M., Passeri M. (1992). Plasma ACTH, beta-en-dorphin, prolactin, growth hormone, and luteinizing hormone levels after thermal stress, heat and cold. Stress Medicine, 8, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi P. P., Di Gennaro C., Coiro V. (1997). Hormonal (ACTH, cortisol, β-endorphin, and met-enkephalin), and cardiovascular responses to hypothermic stress in chronic alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinician and Experimental Research, 21, 1196–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi P. P., Maninetti L., Gerra G., Pedrazzoni M., Pioli G. (1990). Effect of sauna-induced hyperthermia on pituitary secretion of prolactin and gonadotropin hormones. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 12, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Vingren J. L., Kraemer W. J., Ratamess N. A., Anderson J. M., Volek J. S., Maresh C. M. (2010). Testosterone physiology in resistance exercise and training. The up-stream regulatory elements. Sports Medicine, 40(12), 1037–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson J. E., Horvath S. M., Gutin B. (1980) Plasma testosterone during treadmill exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 49, 249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamotová A., Kmoch V., Papežová H. (2012). Role of dehydroepiandrosterone and cortisol in nociceptive sensitivity to thermal pain in anorexia nervosa and healthy women. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 33(4), 401–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitzmann M., Nieschlag E. (2001) Testosterone levels in healthy men in relation to behavioral and physical characteristics: facts and constructs. European Journal of Endocrinology, 144, 183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]