Abstract

A systematic investigation of the silver-doped germanium clusters AgGen with n = 1–13 in the neutral, anionic, and cationic states is performed using the unbiased global search technique combined with a double-density functional scheme. The lowest-energy minima of the clusters are identified based on calculated energies and measured photoelectron spectra (PES). Total atomization energies and thermochemical properties such as electron affinity (EA), ionization potential (IP), binding energy, hardness, and highest occupied molecular orbital-lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO-LUMO) gap are obtained and compared with those of pure germanium clusters. For neutral and anionic clusters, although the most stable structures are inconsistent when n = 7–10, their structure patterns have an exohedral structure except for n = 12, which is a highly symmetrical endohedral configuration. For the cationic state, the most stable structures are attaching structures (in which an Ag atom is adsorbed on the Gen cluster or a Ge atom is adsorbed on the AgGen–1 cluster) at n = 1–12, and when n = 13, the cage configuration is formed. The analyses of binding energy indicate that doping of an Ag atom into the neutral and charged Gen clusters decreases their stability. The theoretical EAs of AgGen clusters agree with the experimental values. The IP of neutral Gen clusters is decreasing when doped with an Ag atom. The chemical activity of AgGen is analyzed through HOMO-LUMO gaps and hardness, and the variant trend of both versus cluster size is slightly different. The accuracy of the theoretical analyses in this paper is demonstrated successfully by the agreement between simulated and experimental results such as PES, IP, EA, and binding energy.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of nanotechnology, the research on the geometric configuration and electronic properties of clusters has become more important because clusters play a pivotal role in the transition from the molecule to the condensed phase, especially for semiconductor clusters owing to their interesting chemical structures and bonding motifs, as well as their importance in the microelectronics industry.1−15 However, pure semiconductor clusters such as germanium clusters are unstable because they show only sp3 bonding characteristics.16−20 Recently, a lot of experimental and theoretical research studies have elucidated that introducing a transition metal atom into germanium clusters can not only heighten their stability, but also deeply affect their electron properties.21−50 Studying the structure and growth model of different transition metal (TM)-doped germanium clusters can not only find a stable cage configuration that can be used as a nanomaterial structure, but also lay a foundation for their special physical and chemical properties. To understand how these attractive physical–chemical properties attribute to the doped clusters, it is important to gain the comprehensive knowledge of the ground state and lower-lying electronic and geometric configurations of charged and neutral TM-doped Ge clusters. Therefore, Nakajima and his colleagues have first explored the electronic and geometric configurations of TMGen (TM = Sc, Y, Ti, Zr, Hf, V, Nb, Ta, and Lu; n = 8–20) clusters by means of dissecting their mass spectra, photoelectron spectra (PES), and reactivities to H2O adsorption.21 Then Zheng and co-workers reported the electron affinities (EAs) and the electronic structures of TMxGen (TM = Ag, Au, Ti, V, Co, Fe, and Cr; x ≤ 2; n ≤ 14) through recording and analyzing their PES.22−31 Prompted by the experimental observations, some theoretical calculations and simulations of TM-doped germanium clusters have been carried out. For instance, the geometries and electronic structures of small sized clusters TiGe2–/0, VGe3–/0, CrGen0/+ (n = 1–5), NbGen–/0/+ (n = 1–3), and VGen–/0 (n = 5–7) have been investigated through multiconfigurational methods.32−36 Wang et al. explored the structural evolution, stability, and electronic properties of MnGen (n = 2–15) by means of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional and found that the threshold size for the formation of caged MnGen and the sealed Mn-encapsulated Gen motif is n = 9 and 10, respectively.37 Kapila et al. investigated the ground-state structures and magnetic moments of CrGen (n = 1–13) using the PBE functional and found that the magnetic moment in their ground-state structure is either 4 μB or 6 μB.38 Bandyopadhyay and co-workers studied the evolution of configuration, electronic properties, and stability of positively charged and neutral TMGen clusters (TM = Mo, Nb, Ni, Sc, Ti, V, Zr, Hf, Cu, and Au; n ≤ 20) using B3LYP or B3PW91 density functional theory (DFT) and presented that the size of the smallest TM-encapsulated into Gen configurations was n = 8 for Nb, n = 9 for Zr, Ti, Hf, and Cu, n = 10 for Mo, and n = 11 for Au atoms.39−45 Rabilloud and co-workers explored the configurations, electronic properties, and magnetic moments of TMGen (TM = V, Nb, Ta, Pd, Pt, Cu, Ag, and Au; n ≤ 21) species using the PBE functional and reported that the smallest size of the TM-encapsulated to Gen cage was n = 10 for Cu and V and n = 12 for Au and Ag.17−20 It is stated that the smallest size of the CuGen cluster evaluated using the PBE functional differs from that evaluated using the B3PW91 functional. For negatively charged ions, Borshch et al. evaluated the ground-state structures of TMGen– (TM = Sc, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta; n ≤ 20), simulated their PES by employing the B3LYP functional, and found that the smallest size of TM@Gen– was n = 12 for Zr, Nb, Hf, and Ta, but n = 13 for Sc atoms.46−50 Kumar and co-workers studied the equilibrium geometry and electronic structure of ZrGen–/0 (n = 1–21) with the PW91 functional, compared their simulated PES with experimental ones, and found that in some cases a higher energy configuration of ZrGen– species may be present in experiments, but the neutral of such an anion is often the lowest energy isomer.51 Trivedi et al. explored the structural stability and electronic and vibrational properties of M@Xn (M = Ag, Au, Co, Pd, Tc, and Zr; X = Ge and Si; n = 10, 12, and 14) with the B3LYP scheme.52,53 Despite performing many theoretical studies on the structural evolution and electronic properties of TM-doped germanium clusters,17−20,32−54 this work, according to our knowledge, is the first systematic study of charged Ag-doped germanium clusters. Moreover, the lowest-energy structures for neutral AgGen with n = 7, 9, 10, 11, and 13 calculated in this study differ from those reported previously.19 In this work, an artificial bee colony algorithm for cluster global optimization (ABCluster)55−57 combined with a double-hybrid density functional is employed for the structure optimization of charged and neutral Ag-doped germanium clusters, AgGenλ (n = 1–13; λ = −1, 0, and +1), with the goal of probing the structural evolution and stability, evaluating thermochemical parameters and electronic properties, and comparing them with charged and neutral pure Ge clusters Gen + 1λ (n = 1–13; λ = −1, 0, and +1), respectively.

2. Computational Methods

The initial isomers for AgGenλ (n = 1–13; λ = −1, 0, and +1) species were based on the ABCluster55−57 combined with the Gaussian 09 codes.58 More than 400 isomers for each cluster were first optimized using the PBE0 functional59 with the effective core potential LanL2DZ basis set60 for Ge atoms and the cc-pVDZ-PP basis set61 for Ag atoms. Then, the lower-lying configurations were selected and reoptimized via the PBE0 functional and cc-pVTZ-PP basis set61,62 for Ge and Ag atoms. Harmonic vibrational frequency calculations were carried out at the same level to guarantee that the configurations were true local minimal structures on the potential energy surface. After completing the initial geometrical optimization using the PBE0/cc-pVTZ-PP scheme, once again, we selected the lower-lying candidates and reoptimized them at the mPW2PLYP/cc-pVTZ-PP level63 without frequency calculations. Finally, single-point energy calculations were carried out using the mPW2PLYP functional in conjunction with the aug-cc-pVTZ-PP basis set61 for Ag atoms and the all-electron aug-cc-pVTZ basis set64 for Ge atoms to further refine the energy. At the mPW2PLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ-PP//mPW2PLYP/cc-pVTZ-PP level, the single-point energy calculations were also performed for comparison.

To check the quality of our used scheme, test calculations were previously performed using the ROCCSD(T) method for ScSin0/– (n = 4–9) clusters and compared with several DFT functionals (PBE, B3LYP, TPSSh, wB97X, and mPW2PLYP).65 The results revealed that (i) only the ground-state structure of ScSin0/– (n = 4–9) clusters predicted by the mPW2PLYP functional is consistent with that calculated by the ROCCSD(T) scheme and (ii) the evaluated vertical detachment energy (VDE) by ROCCSD(T) and mPW2PLYP schemes is in good agreement with the experimental data. The mean absolute deviations of VDE from the experiment for ScSin (n = 4–7 and 9) are by 0.08, 0.09, 0.13, 0.19, and 0.21 eV at the ROCCSD(T), mPW2PLYP, B3LYP, TPSSh, and PBE levels, respectively. Further to check the quality of the mPW2PLYP scheme, the bond length and frequency of Ge2 and AgGe dimers were measured using several DFT functionals (PBE0, TPSSh, B3LYP, and mPW2PLYP) combined with cc-pVTZ-PP basis sets for Ge and Ag atoms and are listed in Table 1. The bond length of Ge2 and AgGe calculated using the mPW2PLYP scheme is 2.38 and 2.45 Å, which agrees with the experimental values of 2.36815 and 2.54 Å,66 respectively. The frequency of Ge2 evaluated using the mPW2PLYP scheme is 286.3 cm–1, which is in excellent agreement with the experimental value of 287.9 cm-1.15 The bond distance of 2.34 Å for Au-Ge predicted by the mPW2PLYP scheme is in good agreement with the experimental value of 2.38 Å.67 Furthermore, the ABCluster’s developers presented many successful examples of ABCluster in a recent article.57 It is proven to be a successful technique for searching the global minimal structure of atomic and molecular clusters to solve the realistic chemical problems.57 Therefore, we believe that the results evaluated using the ABCluster global search technique and the mPW2PLYP functional should be reliable.

Table 1. Bond Length (Å) and Frequency (cm–1) of Ge2 and AgGe Dimers Calculated by Different Functionals Combined with the cc-pVTZ-PP Basis Set for Ge and Ag Atoms.

3. Results and Discussion

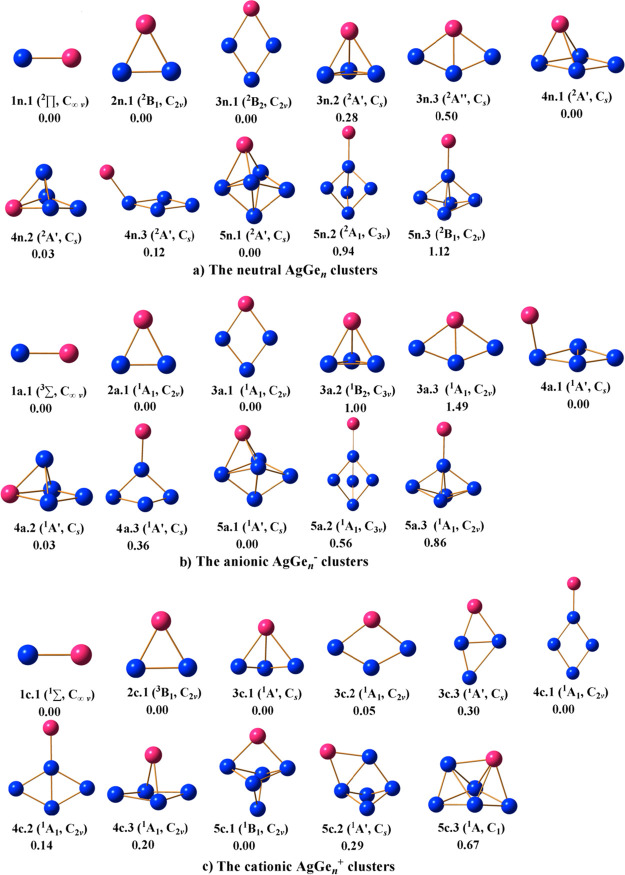

The structures of the optimized geometries of the neutral AgGen, cationic AgGen+, and anionic AgGen– systems, their relative energies, the electronic states, and symmetries are shown in Figures 1–4. For the neutral AgGen (n = 1–13), all the ground states are evaluated to be a doublet; For the cationic state, its lower-lying isomers are calculated to be single except AgGe2+, which is simulated to be a triplet; for the anionic state, the ground state is also simulated to be single except AgGe–, which is simulated to be a triplet.

Figure 1.

Shapes, electron states, and relative energies (ΔE, eV) of the lower-lying isomers AgGen with n = 1–5 at (a) neutral, (b) anionic, and (c) cationic states.

Figure 4.

Shapes, electron states, and relative energies (ΔE, eV) of the lower-lying isomers of (a) AgGe12 and (b) AgGe13.

Figure 2.

Shapes, electron states, and relative energies (ΔE, eV) of the lower-lying isomers AgGen with n = 6–8 at (a) neutral, (b) anionic, and (c) cationic states.

Figure 3.

Shapes, electron states, and relative energies (ΔE, eV) of the lower-lying isomers AgGen with n = 9–11 at (a) neutral, (b) anionic, and (c) cationic states.

3.1. Lower-Lying Isomers of AgGen Clusters and Their Growth Mechanism

From Figures 1–4, it can be seen that the lowest structure and some of its isomers for neutral and charged AgGen (n = 1–13) are carefully selected. Isomers are denoted as nX.Y in which n is the size of Gen, X = n, c, and a stand for a neutral, cation, and anion, respectively, and Y = 1, 2, 3...is arranged in an ascending energy order of the isomers.

n = 1: AgGe, AgGe+, and AgGe–. For AgGe, the ground state 1n.1 is characterized by the 2∏ electron state with [1σ22σ21π41δ22δ23σ22π1] valence electronic configuration in which a bond distance of 2.453 Å is in good agreement with the experimental value of 2.54 Å.65 After attaching an electron, the high spin state 3∑: [1σ22σ21π41δ22δ23σ22π2] is calculated to be the ground state of AgGe– (1a.1). Following the detachment of one electron, the close shell electronic state 1∑: [1σ22σ21π41δ22δ23σ2] becomes the ground state of AgGe+ (1c.1). The bond lengths of 1a.1 and 1c.1 are calculated to be 2.465 and 2.452 Å, showing that gaining or losing an electron has little effect on the bond length of AgGe.

n = 2: AgGe2, AgGe2+, and AgGe2–. A triangular structure 2n.1 with C2v symmetry is found for AgGe2 in which the Ag atom connects with two Ge atoms. For the charged species, the structures of AgGe2– and AgGe2+ are almost unchanged. The anion AgGe2– exhibits the C2v (1A1) structure 2a.1 with a closed shell electronic configuration, and cation AgGe2+ is found to be the 3B1 electron state 2c.1 with C2v symmetry.

n = 3: AgGe3, AgGe3+, and AgGe3–. For AgGe3, the C2v symmetry planar rhombus of the 2A1 electronic state is predicted to be the ground state (3n.1). The isomer 3n.2 in the Cs point group with an 2A′ electronic state can be viewed as attaching an Ag atom to the face of the most stable Ge3 structure,2 which is less stable by 0.28 eV in energy than 3n.1. Following attachment of one electron to form the anionic species, the ground state (3a.1) shape of AgGe3– remains unchanged. In the cationic state, the lowest-energy structure of AgGe3+ is a three-dimensional structure 3c.1 (Cs,1A′), which corresponds to the neutral structure 3n.2. Isomer 3c.2 (C2v,1A1) has a planar shape, which can be viewed as one Ge atom capped in the edge of 2c.1. Interestingly, the 3c.2 in energy is only less stable than the 3c.1 by 0.05 eV, which means that they compete for the ground state of AgGe3+.

n = 4: AgGe4, AgGe4+, and AgGe4–. For AgGe4, isomer 4n.1 and 4n.2 both have the Cs symmetry and 2A′ electronic state. Isomer 4n.1 can be considered as attaching an Ag atom to the face of the most stable Ge4 structure,2 and isomer 4n.2 can be considered as attaching a Ge atom to the face of the most stable AgGe3 structure. Isomer 4n.1 is the lowest-energy isomer, being only 0.03 eV lower than 4n.2, which means both of them compete for the ground state. In the anionic state, the energy of isomer 4a.1 and 4a.2 is also degenerate with an energy gap of 0.03 eV, meaning that the potential energy surface of AgGe4 is relatively shallow. The analysis of simulated PES (see below) indicates that both can coexist in laboratory. The structures of isomer 4a.1 and 4a.2 are both Cs symmetry and 1A′ electronic state. For the cationic state, the C2v symmetry plane geometry of the 1A1 electronic state is predicted to be the ground state (4c.1) in which an Ag atom attached on the top of the most stable rhombus Ge4 structure.2

n = 5: AgGe5, AgGe5+, and AgGe5–. The AgGe5 neutral exhibits a Cs symmetry ground state 5n.1, which can be regarded as an Ag atom capping one face of the most stable Ge5.2 After getting one extra electron, the geometry of the corresponding anion has no significant changes. The ground state 5a.1 with Cs symmetry is more stable in energy than that of isomer 5a.2 and 5a.3 by 0.56 and 0.86 eV, respectively. For the cationic state, the most stable geometry 5c.1 of AgGe5+ has the C2v symmetry with the 1B1 electronic state, which corresponds to the 5n.1.

n = 6: AgGe6, AgGe6+, and AgGe6–. AgGe6 has a Cs (2A′) lowest-energy structure 6n.1, which can be regarded as attaching an Ag atom to the face of the ground state tetragonal bipyramid Ge6.2 The lowest stable geometries of the anion AgGe6– (6a.1) and cation AgGe6+ (6c.1) are almost unchanged as compared to the neutral structure of 6n.1. Interestingly, the degenerate equilibrium ground states are both found in the anionic and cationic state. Energetically, isomer 6a.2 is only less stable than 6a.1 by 0.02 eV for anion AgGe6–, and isomer 6c.2 also is only less stable than 6c.1 by 0.06 eV for cation AgGe6+. Isomer 6a.2 and 6c.2 both can be regarded as attaching an Ag atom to the edge and the top of the most stable Ge6 structure.2 The analysis of simulated PES (see below) indicates that the 6a.1 configuration is the ground-state structure.

n = 7: AgGe7, AgGe7+, and AgGe7–. For AgGe7, the structure of the ground state 7n.1 (C2v, 2B1) and isomer 7n.2 (C5v,2A1) is 0.22 eV higher in energy as compared to 7n.1, and both can be considered as an Ag atom capping on the edge and the apex of Ge7pentagonal bipyramid,2 respectively. The isomer 7n.4, which is considered the most stable structure in ref (19)., is 0.45 eV higher in energy than 7n.1. Following attachment of one electron, the C5v symmetry structure 7a.1, which corresponds to the neutral 7n.2, acts as the ground state for AgGe7–. For the cationic state, the geometry of the best isomer for AgGe7+ is the same as that of the neutral 7n.1. The C2v symmetry state 7c.1 (1A1) is more stable in energy than that of isomer 7c.2 and 7c.3 by 0.50 and 0.85 eV, respectively.

n = 8: AgGe8, AgGe8+, and AgGe8–. The best isomer of neutral AgGe8 (8n.1) with Cs symmetry and 2A″ electronic state can be seen as attaching an Ag atom to the face of the capped pentagonal bipyramid Ge8.2 The next isomer 8n.2 (Cs,2A′), being 0.16 eV less stable than 8n.1, can be viewed as a distorted Ge8quadrangular prism with a capped Ag atom on one face. Two other isomers 8n.3 (C1,2A) and 8n.4 (Cs,2A′), which are both formed by adding one Ge atom into the pentagonal bipyramid Ge7 and then attaching one Ag atom, are 0.19 and 0.46 eV less stable, respectively, in energy than 8n.1. For anion AgGe8–, the isomer 8a.1 (Cs,1A′), corresponding to neutral 8n.1, is only 0.06 eV lower in energy than 8a.2 (corresponds to the neutral 8n.2). Although isomer 8a.1 has the lowest energy, we consider that 8a.2 is the best candidate for the ground-state structure through the comparison of the calculated and experimental PES (see below). In the cationic state, the Cs symmetry and 1A″ electronic state 8c.1, which corresponds to neutral 8n.3, is calculated as the lowest-energy structure of AgGe8+. The next isomer 8c.2 (C1,1A), which is a distorted form of 8n.1, is less stable in energy than the 8c.1 by 0.22 eV.

n = 9: AgGe9, AgGe9+, and AgGe9–. For the neutral AgGe9, two degenerate structures, 9n.1 (C1,2A) and 9n.2 (Cs,2A′), are found within an energy gap of 0.04 eV. Isomer 9n.1 is formed by adding one Ge atom on the face of the most stable structure AgGe8. Isomer 9n.2 also can be viewed as attaching an Ag atom to the tricapped trigonal prism Ge9.2 The isomer 9n.3, which is reported as the most stable structure in ref (19)., is 0.37 eV higher in energy than 9n.1. For the anion, the geometries of the ground state 9a.1 for AgGe9– have the same structures corresponding to neutral 9n.2. The best isomer 9a.1 (Cs,1A′) is 0.30 eV lower in energy than the isomer 9a.4 (corresponding to neutral 9n.1). In the cationic state, the most stable structure 9c.1 (Cs,1A′), which is formed by adding an Ag atom on the edge of the most stable structure Ge9,2 is 0.16 eV more stable in energy than the isomer 9c.4 (corresponding to neutral 9n.1).

n = 10: AgGe10, AgGe10+, and AgGe10–. The C3v symmetry structure of the 2A1 electronic state is predicted to be the ground state (10n.1) for AgGe10. It is formed by either adding one Ge atom into the face of structure 9n.2 or adsorbing an Ag atom on the face of the tetracapped trigonal prism Ge10.2 The isomer 10n.3, which is predicted to be the most stable structure in ref (19)., is 0.41 eV higher in energy than 10n.1. In the anionic state, the most stable structure 10a.1 with Cs symmetry and 1A′ electronic state is formed by adding an Ag atom on the face of bicapped tetragonal antiprism Ge10. The isomer 10a.2 with C4v symmetry and 1A1 electronic state can be formed by attaching an Ag atom on the vertex of the bicapped tetragonal antiprism Ge10. It is only less stable than 10a.1 by 0.06 eV in energy. Simulated PES analysis shows that both isomers can exist (see below). For cationic clusters, the ground-state isomer 10c.1 with Cs symmetry (1A′) can also be derived by adding an Ag atom on a different face of the tetracapped trigonal prism Ge10.

n = 11: AgGe11, AgGe11+, and AgGe11–. For AgGe11, the C1 structure 11n.1, which can be viewed as distorted by a substitution of an Ag atom for a Ge atom of icosahedral-like Ge12, is found to be the global minima of the cluster. The isomer 11n.2 with C2v symmetry (2A1), which is reported as the most stable structure in ref (19)., is 0.19 eV higher in energy than 11n.1. Isomer 11n.3 with C2v symmetry (2A1) is an Ag-encapsulated into Ge11 cage, being 0.33 eV higher in energy than 11n.1. Following the attachment of one electron, the most stable structure 11a.1, corresponding to neutral 11n.1, has the C1 symmetry and 1A electronic state. The cage structure 11a.4 (C2v,1A1) is less stable in energy than 11a.1 by 0.79 eV. For the cationic state, the ground state 11c.1 of AgGe11+ is formed by attaching the additional Ge atom on the face of 10c.1. The structure 11c.2, which is a slightly distorted form of neutral cage structure 11n.3, is less stable in energy than 11c.1 by 0.34 eV.

n = 12: AgGe12, AgGe12+, and AgGe12–. The ground state 12n.1 of neutral AgGe12 is an endohedral structure with D2d symmetry in which an Ag atom is located inside a Ge12 cage. The isomer 12n.3 is D5d symmetric icosahedron-like in which an Ag atom is located inside a dicapped pentagonal antiprism cage. The isomer 12n.3 is 0.15 eV higher in energy relative to 12n.1. Following attachment of one electron, the ground state 12a.1 of AgGe12–, which corresponds to neutral 12n.3, has a high Ih (1Hg) symmetric icosahedral structure. This structure is similar to that of the AuGe12– reported by Zheng in the series of studies on Au-doped Gen clusters.26 For the cationic state, the geometry of the best isomer 12c.1 for AgGe12+ is an exohedral structure with Cs symmetry and 1A′ electronic state, which can be viewed as attaching an Ag atom to the face of hexcapped trigonal prism Ge12.2 Isomers 12c.2, 12c.3, and 12c.4 are all cage structures, being 0.38, 0.55, and 1.13 eV higher in energy than 12c.1, respectively.

n = 13: AgGe13, AgGe13+, and AgGe13–. The most stable structure 13n.1 of neutral AgGe13 is not a cage configuration but an exohedral structure, which can be viewed as replacing a Ge atom of the most stable structure of Ge143 with an Ag atom. The best isomer 13n.1 with C1 symmetry is more stable in energy than the cage structure 13n.2 and 13n.3 by 0.32 and 0.39 eV, respectively. Isomer 13n.4 also is a no-cage structure with C1 symmetry, which is reported as the lowest-energy configuration in the literature,19 but here it is 0.54 eV higher than 13n.1. For AgGe13–, the ground state 13a.1 (corresponding to the neutral ground state 13n.1) with Cs symmetry and 1A′ electronic state also is an exohedral structure. The isomer 13a.1 is more stable than the endohedral isomer 13a.2, 13a.3, and 13a.4 by 0.68, 0.70, and 0.82 eV, respectively. For AgGe13+, the ground state 13c.1 with C4v symmetry is calculated to be an endohedral structure, which is a capped fullerene-like cage. The next isomer 13c.2, which can be considered as the Ag-encapsulated into Ge13 cage of the dimer-capped pentagonal-hexagonal prism, is less stable than 13c.1 by 0.06 eV energetically.

3.2. Growth Pattern

Based on the structural features of the determined global minimum structure, the growth mechanism for the clusters AgGen with n = 1–13 emerges as follows: For neutral clusters, the most stable forms of AgGen except the AgGe12 definitely prefer an exohedral structure, which is formed by attaching an Ag atom to a Gen cluster or a Ge atom to an AgGen-1 cluster when n = 1–10, and when n = 13, it is formed by replacing a Ge atom of a Gen + 1 cluster with an Ag atom. For anionic states, although the lowest-energy structures of AgGen– at n = 7–10 are different from the corresponding neutral clusters, the growth patterns of most stable structures are consistent. For cationic states, the global minimal structures of AgGen+ with n ranging from 1 to 12 are formed by attaching an Ag atom to the Gen cluster or a Ge atom to the AgGen–1 cluster, and the endohedral structure becomes the ground-state configuration when n = 13. The ground-state configurations of AgGen+ are different from the corresponding neutral ground-state structure when n = 3, 4, and 8–13.

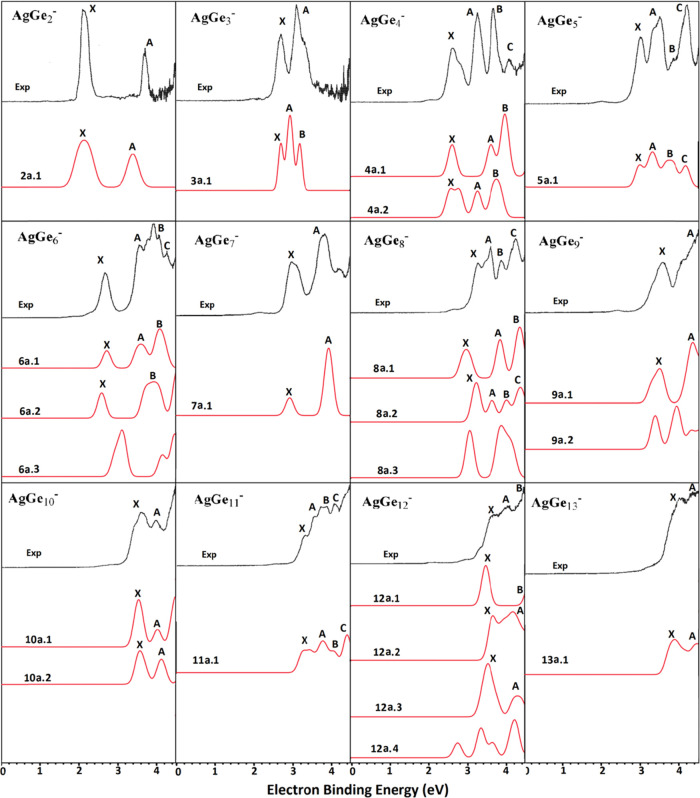

3.3. Photoelectron Spectra

By comparing the PES obtained by theoretical calculation and experiment, it can not only verify the accuracy of the ground-state structure predicted by the theoretical calculation, but also explain the reliability of the theoretical calculation scheme. In this section, the PES of the ground-state isomers for AgGen– (n = 2–13) are simulated based on the generalized Koopmans’ theorem (denoted as ΔDFT) combined with Multiwfn software68 and compared with experimental data.22 First, the VDE which corresponds to the first peak of PES and the adiabatic electron affinity (AEA) of experiment and simulation are compared and listed in Table 2. Then, the number of other peaks and their relative locations are matched by the simulated PES and experimental one. The simulated PES of the most stable structures and experimental spectra are displayed in Figure 5.

Table 2. Theoretical and Experimental VDEs and AEAs for AgGen– (n = 1–13).

| VDE | AEA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | theor | exptla | Theor | exptla |

| 1 | 1.50(1.47) | 1.50(1.47) | ||

| 2 | 2.13(2.08) | 2.11 ± 0.08 | 2.08(2.05) | 1.97 ± 0.08 |

| 3 | 2.71(2.65) | 2.74 ± 0.08 | 2.55(2.51) | 2.50 ± 0.08 |

| 4 | 2.62(2.58) | 2.65 ± 0.08 | 2.34(2.30) | 2.39 ± 0.08 |

| 5 | 2.98(2.93) | 3.02 ± 0.08 | 2.62(2.58) | 2.73 ± 0.08 |

| 6 | 2.70(2.63) | 2.70 ± 0.08 | 2.37(2.35) | 2.43 ± 0.08 |

| 7 | 2.93(2.87) | 2.99 ± 0.08 | 2.45(2.37) | 2.71 ± 0.08 |

| 8 | 3.24(3.16) | 3.27 ± 0.08 | 2.75(2.67) | 2.97 ± 0.08 |

| 9 | 3.47(3.40) | 3.59 ± 0.08 | 3.07(3.02) | 3.06 ± 0.08 |

| 10 | 3.54(3.40) | 3.64 ± 0.20 | 2.98(2.94) | 3.22 ± 0.20 |

| 11 | 3.32(3.27) | 3.37 ± 0.20 | 3.05(2.99) | 3.06 ± 0.20 |

| 12 | 3.48(3.41) | 3.68 ± 0.20 | 3.19(3.31) | 3.34 ± 0.20 |

| 13 | 3.86(3.74) | 4.04 ± 0.20 | 3.56(3.48) | 3.45 ± 0.20 |

From ref (22).; The values in parentheses are calculated at the mPW2PLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ-pp.

Figure 5.

Simulated PES spectra of the lowest-lying energy structures of AgGen– (n = 2–13) clusters. Experimental PES reprinted with permission from ref (22).

As shown in Figure 5, the simulated PES of the 2a.1 have two different peaks (X and A) within ≤4.5 eV located at 2.13 and 3.39 eV, which are in concordance with the experimental data of 2.11 and 3.70 eV.22 From the PES of AgGe3–, it can be seen that simulated PES of the 3a.1 have three adjacent peaks (X, A, and B) located at 2.71, 2.94, and 3.19 eV. The first and third peak’s positions can be consistent with the experimental values of 2.74 and 3.13 eV. For AgGe4–, the simulated PES of the 4a.1 and 4a.2 have three distinct peaks (X, A, and B) situated at 2.62, 3.62, and 3.98 eV and 2.59, 3.27, and 3.76 eV, respectively. They are in concordance with the experimental data of 2.65, 3.27, and 3.68 eV, respectively. Therefore, we suggest that two energy degenerate isomers 4a.1 and 4a.2 coexist in the experiment. For the simulated PES of 5a.1, there are four peaks (X, A, B, and C) located at 2.98, 3.31, 3.74, and 4.16 eV, which is in good accordance with the experimental data of 3.02, 3.50, 3.85, and 4.22 eV,22 respectively. For AgGe6–, two PES are simulated. The simulated PES of the 6a.1 have three distinct peaks (X, A, and B) situated at 2.71, 3.59, and 4.08 eV, which are in excellent agreement with the experimental values of 2.70, 3.58, and 3.94 eV,22 respectively. The simulated PES of the 6a.2 have two distinct peaks (X and B) situated at 2.58 and 3.93 eV. Although they are in concordance with the experimental data of 2.70 and 3.94 eV, the number of peaks is obviously insufficient. The simulated PES of the 7a.1 have two different peaks (X and A) within ≤4.5 eV located at 2.93 and 3.93 eV, which are in concordance with the experimental data of 2.99 and 3.80 eV.22 For AgGe8–, there are four different peaks (X, A, B, and C) located at 3.24, 3.64, 4.02, and 4.38 eV in the simulated PES of 8a.2, which well reproduce the experimental values22 of 3.27, 3.62, 3.88, and 4.25 eV, respectively. The spectrum of isomer 8a.1 has three distinct peaks (X, A, and B) situated at 2.98, 3.86, and 4.36 eV, which can be ruled out of the most stable structure of AgGe8–. For AgGe9–, two distinct peaks located at 3.47 and 4.33 eV are obtained in the simulated PES of 9a.1, and they are in reasonable agreement with the experimental values of 3.59 and 4.38 eV.22 For AgGe10–, two distinct peaks located at 3.54 and 4.02 eV and 3.57 and 4.11 eV are obtained in the simulated PES of 10a.1 and 10a.2, respectively. They agree with the experimental values of 3.64 and 4.03 eV, respectively.22 It is to say that these two energy degenerate isomers may coexist in the experiment. Four peaks for simulated PES of 11a.1 are situated at 3.32, 3.79, 4.04, and 4.41 eV, which are in excellent agreement with the experimental data of 3.37, 3.61, 3.90, and 4.15 eV,22 respectively. Although Kong22 pointed out that the peak shape of experimental PES of AgGe12– was wide and it was difficult to observe a clear peak because of the overlap of energy levels, three peaks (X, A, and B) can be roughly assigned to 3.68, 4.11, and 4.50 eV. It is interesting that the simulated PES of 12a.1 have two resolved peaks (X and B) centered at 3.48 and 4.61 eV, which is in good accordance with the experimental data of 3.68 (X) and 4.50 (B) eV,22 while the simulated PES of 12a.2 and 12a.3 also have two distinct peaks (X and A) situated at 3.67 and 4.18 eV and 3.54 and 4.30 eV, respectively. They are in concordance with the experimental data of 3.68 (X) and 4.11 (A) eV, respectively. In this case, one cannot determine which isomer is the ground-state structure. Therefore, we highly suggest that the experimental PES of AgGe12– should be further examined. The simulated PES of 13a.1 have two major features centered at 3.86 and 4.45 eV, which are in reasonable agreement with the experimental values of 4.04 and 4.38 eV.22

3.4. EAs and IP

From Table 2, it can be concluded that the first theoretical VDEs of AgGen– (n = 2–13) show a good agreement with available experimental values.22 The average absolute deviation of them is 0.07 (0.14) eV (the value in parentheses is calculated at the mPW2PLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ-PP//mPW2PLYP/cc-pVTZ-PP level). The largest deviation is 0.20 eV for AgGe12, which is within experimental errors of 0.20 eV. For the AEAs, the quantitative analysis suggests that the mean absolute deviation of simulated of AgGen (n = 2–13) from the experimental data is 0.11 (0.12) eV. The largest error is AgGe7 and AgGe10, which is off by 0.26 and 0.24 eV, respectively. The reason may be that their experimental PES exhibit a featureless long and very rounded tail, which means that it is difficult to determine the exact AEA value. If AgGe7 and AgGe10 are removed, the average absolute deviations are only 0.09 eV. All these show that our theoretical method is reliable and once again confirms that the ground-state configurations in this paper are accurate.

Vertical ionization potential (VIP) and adiabatic ionization potential (AIP), as important chemical and physical quantities, are discussed in this section. The VIP [defined as the difference of total energies as follows: VIP = E(cation at optimized neutral geometry) – E(optimized neutral)] and AIP [defined as the difference of total energies in following manner: VIP = E(optimized cation) – E(optimized neutral)] of neutral AgGen cluster and pure Gen + 1 clusters are calculated and listed in Table 3. No experimental IP of AgGen is available for comparison. Therefore, we compared the IP of AgGen with that of pure Gen clusters as shown in Figure 6. From Figure 6, it can be found that (i) The IP with two different types of VIP and AIP for AgGen clusters is lower than that of pure Gen + 1 clusters, respectively, meaning that doping an Ag atom in neutral Gen clusters will decrease their IP. (ii) For AgGen (n = 1–13) clusters, the highest VIP and AIP values are calculated to be 7.71 eV for AgGe3 and 7.07 eV for AgGe2, respectively. AgGe7 and AgGe10 present the minimum values of VIP and AIP by 5.91 and 5.68 eV, respectively. (iii) For Gen + 1 (n = 1–13) clusters, the calculated values of VIP are in good agreement with the experimental data,5 and their average absolute deviation is only 0.08 (0.09) eV.

Table 3. VIP and AIP of AgGen and Gen + 1 (n = 1–13) Clusters.

| cluster | VIP (eV) | AIP (eV) | Cluster | VIP (eV) | expt. of VIP | AIP (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgGe | 7.05 (7.02) | 7.05 (7.02) | Ge2 | 7.57 (7.52) | 7.58–7.76 (7.67)a | 7.57 (7.51) |

| AgGe2 | 7.07 (7.03) | 7.07 (7.03) | Ge3 | 8.01 (7.96) | 7.97–8.09 (8.03)a | 7.92 (7.87) |

| AgGe3 | 7.71 (7.67) | 6.89 (6.84) | Ge4 | 7.80 (7.76) | 7.87–7.97 (7.92)a | 7.53 (7.48) |

| AgGe4 | 6.70 (6.64) | 6.33 (6.32) | Ge5 | 7.96 (7.91) | 7.87–7.97 (7.92)a | 7.79 (7.75) |

| AgGe5 | 7.17 (7.11) | 6.61 (6.54) | Ge6 | 7.76 (7.72) | 7.58–7.76 (7.67)a | 7.36 (7.33) |

| AgGe6 | 6.63 (6.57) | 6.25 (6.23) | Ge7 | 7.89 (7.84) | 7.58–7.76 (7.67)a | 7.55 (7.51) |

| AgGe7 | 5.91 (5.88) | 5.70 (5.67) | Ge8 | 7.01 (6.94) | 6.72–6.94 (6.83)a | 6.61 (6.53) |

| AgGe8 | 6.64 (6.54) | 6.17 (6.09) | Ge9 | 7.20 (7.09) | 7.06–7.24 (7.15)a | 7..1 (6.94) |

| AgGe9 | 6.42 (6.34) | 6.05 (5.94) | Ge10 | 7.55 (7.45) | 7.46–7.76 (7.61)a | 7.38 (7.31) |

| AgGe10 | 6.24 (6.17) | 5.68 (5.60) | Ge11 | 6.59 (6.53) | 6.55–6.72 (6.64)a | 6.34 (6.28) |

| AgGe11 | 6.46 (6.39) | 5.86 (5.81) | Ge12 | 7.10 (7.00) | 6.94–7.06 (7.00)a | 6.88 (6.83) |

| AgGe12 | 6.13 (6.82) | 5.67 (5.81) | Ge13 | 7.03 (6.97) | 6.94–7.06 (7.00)a | 6.82 (6.71) |

| AgGe13 | 6.74 (6.65) | 6.06 (5.92) | Ge14 | 7.14 (7.08) | 7.06–7.24 (7.15)a | 6.86 (6.82) |

The data taken from ref (5). and in parentheses are average values; the values in parentheses are calculated at the mPW2PLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ-pp level.

Figure 6.

IP of the ground-state structure of AgGen and Gen + 1 (n = 1–13) clusters.

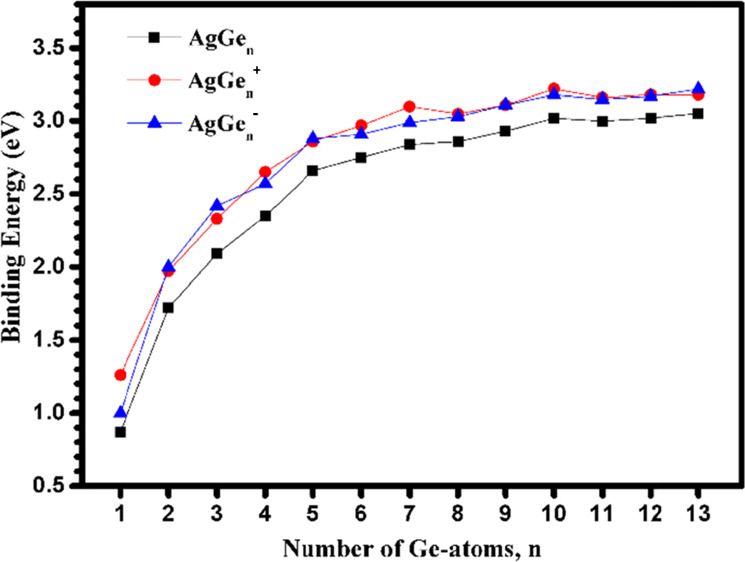

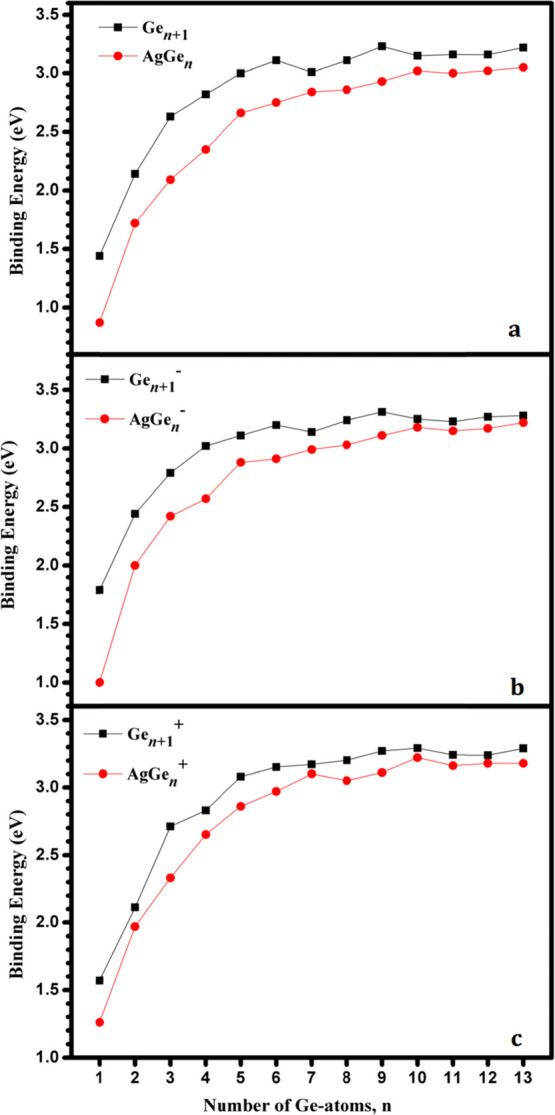

3.5. Binding Energy and Relative Stability

The relative stabilities of the most stable structures of AgGenλ (λ = −1, 0, and +1; n = 1–13) clusters are examined in terms of both binding energy per atom (Eb) and second-order difference in energy (Δ2E). Eb(AgGenλ) and Δ2E(AgGenλ) are defined as the following reactions:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

Where E(Ag), E(Ge), E(Ge+), and E(Ge–) are the total energies of the Ag atom, Ge atom and the charged Ge+ and Ge–, respectively. E(AgGen), E(AgGen+), and E(AgGen–) are the total energies of the cluster AgGen at neutral, cationic, and anionic states, respectively. To understand how the Ag dopant influences the stability of pure Gen clusters, the Eb and Δ2E of Gen + 1λ (λ = −1, 0, and +1; n = 1–13) are further examined and are defined as follows:

| 5 |

| 6 |

Where E(Genλ) are the total energies of neutral, cationic, and anionic Gen clusters, respectively. These total energies are calculated through the mPW2PLYP scheme combined with the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set for the most stable structures of neutral and charged Gen clusters reported in previous studies.2,3,9,67 The Eb values are listed in Table 4, and the plots are shown in Figures 7 and 8. The plots of Δ2E are given in Figure 9.

Table 4. Average Binding Energies (Eb, eV) of AgGenλ and Gen + 1λ (λ = −1, 0, and +1; n = 1–13) Clustersa.

| Eb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | AgGen– | AgGen | AgGen+ | Gen + 1– | Gen + 1 | Gen + 1+ |

| 1 | 1.00 (1.00) | 0.87 (0.87) | 1.26 (1.25) | 1.79 (1.77) | 1.44 (1.42) | 1.57 (1.56) |

| 2 | 2.00 (1.98) | 1.72 (1.70) | 1.97 (1.95) | 2.44 (2.41) | 2.14 (2.12) | 2.11 (2.09) |

| 3 | 2.42 (2.40) | 2.09 (2.07) | 2.33 (2.31) | 2.79 (2.76) | 2.63 (2.61) | 2.71 (2.68) |

| 4 | 2.57 (2.55) | 2.35 (2.33) | 2.65 (2.62) | 3.02 (2.99) | 2.82 (2.80) | 2.83 (2.80) |

| 5 | 2.88 (2.86) | 2.66 (2.63) | 2.86 (2.84) | 3.11 (3.08) | 3.00 (2.98) | 3.08 (3.05) |

| 6 | 2.91 (2.88) | 2.75 (2.72) | 2.97 (2.94) | 3.20 (3.17) | 3.11 (3.09) | 3.15 (3.13) |

| 7 | 2.99 (2.96) | 2.84 (2.81) | 3.10 (3.08) | 3.14 (3.10) | 3.01 (2.99) | 3.17 (3.14) |

| 8 | 3.03 (3.00) | 2.86 (2.84) | 3.05 (3.02) | 3.24 (3.21) | 3.11 (3.08) | 3.11 (3.17) |

| 9 | 3.11 (3.09) | 2.93 (2.90) | 3.11 (3.09) | 3.31 (3.28) | 3.23 (3.20) | 3.27 (3.25) |

| 10 | 3.18 (3.15) | 3.02 (2.99) | 3.22 (3.19) | 3.25 (3.22) | 3.15 (3.12) | 3.29 (3.26) |

| 11 | 3.15 (3.12) | 3.00 (2.97) | 3.16 (3.13) | 3.23 (3.20) | 3.16 (3.13) | 3.24 (3.21) |

| 12 | 3.17 (3.16) | 3.02 (3.00) | 3.18 (3.15) | 3.27 (3.24) | 3.16 (3.13) | 3.24 (3.22) |

| 13 | 3.22 (3.19) | 3.05 (3.02) | 3.18 (3.16) | 3.28 (3.26) | 3.22 (3.19) | 3.29 (3.26) |

The values in parentheses are calculated at the mPW2PLYP/aug-cc-pVTZ-pp level.

Figure 7.

Average binding energy (Eb, eV) of AgGenλ (λ = 0, +1, and −1; n = 1–13) clusters.

Figure 8.

Binding energy (Eb, eV) of AgGenλ and Gen + 1λ (λ = 0, −1, and +1; n = 1–13) clusters at (a) neutral, (b) anionic, and (c) cationic states.

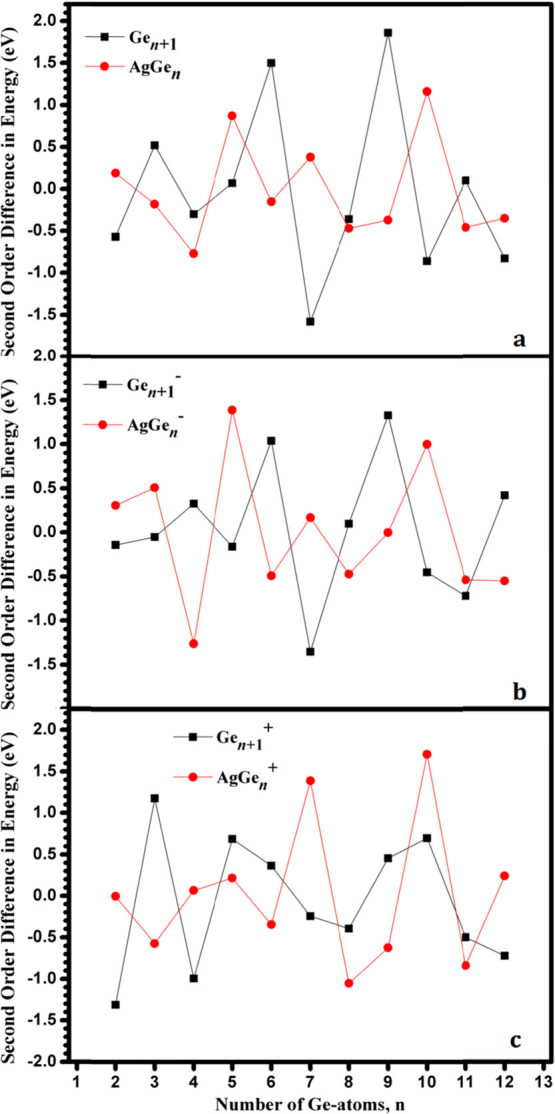

Figure 9.

Second-order difference in energy (Δ2E, eV) of AgGenλ and Gen + 1λ (λ = 0, −1, and +1; n = 1–13) clusters at (a) neutral, (b) anionic, and (c) cationic states.

From Figures 7 and 8, it can be seen that: (i) The Eb(AgGen–) and Eb(AgGen+) are larger than the corresponding Eb(AgGen). This is because AgGen clusters possess an open-shell electronic structure. When an electron is obtained or lost, AgGen– (except for AgGe–, the most stable state is a triplet) or AgGen+ (except for AgGe2+, the most stable state is a triplet) clusters have the closed shell electronic structure, enhancing the stability. It should be noted that the simulated binding energy of AgGe is 0.87 eV, which is perfectly in line with the experimental value of 0.89 eV.66 (ii) Whether it is neutral or charged AgGen and Gen + 1, the binding energy is increased with the increase of the cluster sizes. The binding energies of pure Gen + 1 and its charged clusters are slightly larger than those of Ag-doped germanium corresponding clusters, respectively, which indicates that doping of an Ag atom may decrease the stability of neutral and charged Gen + 1 clusters. (iii) The maximum values of Eb are calculated to be 3.02 eV (AgGe12) and 3.05 eV (AgGe13) for neutral AgGen clusters and 3.23 eV (Ge10) and 3.22 eV (Ge14) for neutral Gen + 1 clusters, which indicates that they show a good thermodynamic stability. At the anionic state, the value of Eb is the maximum at n = 10 (3.18 eV) and n = 13 (3.22 eV) for AgGen– clusters and at n = 10 (3.31 eV) and n = 14 (3.28 eV) for Gen– clusters. At the cationic state, AgGe10+ presents the highest Eb value by 3.22 eV for AgGen+ clusters, and Ge11+ and Ge14+ present the highest binding energy at the same value (3.29 eV) for Gen+ clusters.

The second-order difference in energy of the nanoalloy cluster is the feature that reflects the relative stability between one cluster and its two directly adjacent clusters. The higher the value of Δ2E, the better the relative stability of the cluster. It can be observed from Figure 9 that the Δ2E for AgGe50/–/+, AgGe70/–/+, AgGe100/–/+, AgGe120/–/+, Ge40/+, Ge70/–, Ge100/–, Ge12, Ge5–, Ge6+, and Ge11+ clusters all have obvious peaks, indicating that their stability is higher than that of the adjacent clusters.

3.6. HOMO-LUMO Gap and Hardness

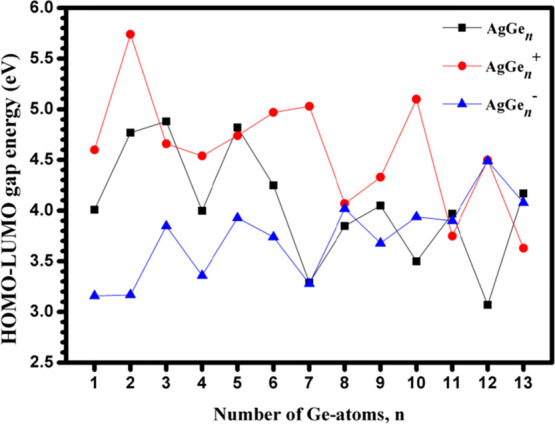

HOMO-LUMO energy gap (Egap) is an electronic property of clusters, which can be used to express the performance of related chemical properties, such as photochemistry and conductivity. The value of Egap means the minimum energy required to transfer an electron from the HOMO to the LUMO. The value of the HOMO-LUMO gap has an inverse response to the external perturbations, which means that a small value corresponds to a large response. Therefore, the Egap of neutral and charged AgGenλ (λ = 0, −1, +1; n = 1–13) clusters has been computed using the mPW2PLYP scheme and is pictured in Figure 10. It can be found that: (i) For neutral clusters, the values of Egap range from 3.07 to 4.88 eV. The maximum value is calculated at AgGe3, and the minimum value is calculated at AgGe7. In anionic states, Egap ranges from 3.16 to 4.49 eV. The maximum value is calculated at AgGe12–, and the minimum value is calculated at AgGe– and AgGe2–. For cationic states, it ranges from 3.63 to 5.74 eV. The minimum value is simulated at AgGe13+, and the maximum value is calculated at AgGe2+. (ii) The Egap of AgGen clusters are larger than that of AgGen– clusters with the exception of n = 8 and 12, indicating that an additional electron reduces their chemical stability. Furthermore, after losing an electron, the Egap of AgGen+ is narrower than that of AgGen for n = 3, 5, and 11–13 and is wider for n = 1, 2, 4, and 6–10.

Figure 10.

Highest occupied molecular orbital-lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO-LUMO) energy gap (Egap, eV) of AgGenλ (λ = 0, −1,+1; n = 1–13) clusters.

Hardness (η), as another important parameter reflecting the chemical properties, is calculated for AgGen (n = 1–3), and it can be defined as follows:

| 7 |

To facilitate comparison, hardness and HOMO-LUMO gap of AgGen are shown in Figure 11 as a function of cluster sizes. To better understand the relationship of changes between them, the comparison of HOMO with VIP and LUMO with VDE is also given in Figure 11. It can be seen from Figure 11 that the trend of Egap and hardness is slightly different. For example, the hardness analysis of AgGe shows that it has a weak chemical reactivity, but HOMO-LUMO gap analysis indicates that it possesses a strong chemical activity. The reason is that the trend of HOMO and VIP is the same. However, the trend of LUMO and VDE is slightly different.

Figure 11.

Chemical hardness and HOMO-LUMO gap of AgGen clusters.

3.7. Charge Transfer and Partial Density of States (PDOS)

In this section, NPAs of the most stable structure for AgGenλ (n = 1–13; λ = −1, 0, and +1) clusters were performed using the mPW2PLYP scheme. The results are shown in Table 5. From Table 5, it can be seen that the valence configurations of the Ag atom in AgGenλ (n = 1–13; λ = −1, 0, and +1) clusters are 5s0.36–1.224d9.77-9895p0.01–2.70. Regardless of being neutral or charged, the 4d electrons of Ag atoms are almost unchanged, meaning that the 4d electrons of Ag hardly participate in bonding. The calculated charges of Ag atoms in AgGen (n = 1–13) with the exception of n = 1 and 12 are 0.02–0.48 a.u, indicating that Ag atoms mainly act as electron donors. The charges of Ag atoms in anionic clusters are the same as those in neutral clusters, revealing that the extra electron is completely localized in the germanium clusters. Ag atoms in cationic AgGen+ (n = 1–12) clusters also act as electron donors. The charges of Ag atoms in cationic AgGen+ (n = 1–12) clusters are 0.20–0.69 a.u. which are larger by 0.14–0.47 a.u. as compared with the charges of Ag atoms in neutral clusters. That is to say the germanium clusters provide the majority of lost charges for cationic AgGen+ (n = 1–12) species. The charges of Ag atoms in the cage-like configuration of AgGe12, AgGe12–, and AgGe13+ clusters are by −1.8 a.u., indicating that Ag atoms in these clusters act as an electron acceptor.

Table 5. Natural Population Analysis (NPA) Valence Configurations and Charge of Ag Atoms (in a.u.) Calculated with the mPW2PLYP Method for the Most Stable Structure AgGen (n = 1–13) and Their Charged Clusters.

| species | charge | electron configuration | species | charge | electron configuration | species | charge | electron configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgGe | –0.05 | [core]5s1.074d9.865p0.05 | AgGe– | –0.05 | [core]5s1.224d9.875p0.11 | AgGe+ | 0.20 | [core]5s0.844d9.855p0.05 |

| AgGe2 | 0.20 | [core]5s0.794d9.875p0.08 | AgGe2– | 0.20 | [core]5s0.844d9.875p0.19 | AgGe2+ | 0.41 | [core]5s0.614d9.865p0.07 |

| AgGe3 | 0.28 | [core]5s0.704d9.865p0.11 | AgGe3– | 0.28 | [core]5s0.884d9.865p0.24 | AgGe3+ | 0.45 | [core]5s0.564d9.865p0.07 |

| AgGe4 | 0.32 | [core]5s0.634d9.875p0.12 | AgGe4– | 0.32 | [core]5s1.064d9.885p0.09 | AgGe4+ | 0.68 | [core]5s0.384d9.895p0.01 |

| AgGe5 | 0.28 | [core]5s0.594d9.865p0.22 | AgGe5– | 0.28 | [core]5s0.694d9.865p0.29 | AgGe5+ | 0.42 | [core]5s0.504d9.855p0.18 |

| AgGe6 | 0.30 | [core]5s0.624d9.855p0.18 | AgGe6– | 0.30 | [core]5s0.734d9.835p0.38 | AgGe6+ | 0.69 | [core]5s0.364d9.895p0.01 |

| AgGe7 | 0.48 | [core]5s0.494d9.885p0.11 | AgGe7– | 0.48 | [core]5s1.034d9.885p0.06 | AgGe7+ | 0.64 | [core]5s0.374d9.885p0.07 |

| AgGe8 | 0.16 | [core]5s0.594d9.825p0.37 | AgGe8– | 0.16 | [core]5s0.624d9.815p0.67 | AgGe8+ | 0.37 | [core]5s0.654d9.885p0.05 |

| AgGe9 | 0.19 | [core]5s0.604d9.845p0.31 | AgGe9– | 0.19 | [core]5s0.614d9.875p0.22 | AgGe9+ | 0.63 | [core]5s0.404d9.875p0.05 |

| AgGe10 | 0.32 | [core]5s0.634d9.865p0.14 | AgGe10– | 0.32 | [core]5s0.604d9.885p0.19 | AgGe10+ | 0.58 | [core]5s0.404d9.885p0.09 |

| AgGe11 | 0.02 | [core]5s0.564d9.825p0.53 | AgGe11– | 0.02 | [core]5s0.634d9.815p0.74 | AgGe11+ | 0.50 | [core]5s0.514d9.865p0.09 |

| AgGe12 | –1.80 | [core]5s0.674d9.775p2.24 | AgGe12– | –1.80 | [core]5s0.634d9.845p2.70 | AgGe12+ | 0.53 | [core]5s0.464d9.875p0.09 |

| AgGe13 | 0.23 | [core]5s0.634d9.835p0.25 | AgGe13– | 0.23 | [core]5s0.704d9.845p0.25 | AgGe13+ | –1.78 | [core]5s0.684d9.785p2.21 |

To better explore the electronic properties and HOMO-LUMO gap changes caused by the doping of Ag atoms, the detailed density of states (DOS) of AgGe7 as an example is provided. The PDOS of pure Ge7 and AgGe7 is shown in Figure 12. It can be seen from Figure 12 that the position of occupied spin up and spin down states is identical for DOS of pure Ge7. However, after the doping of Ag atoms, a new occupied spin up state in DOS is created, which causes a significant change in the HOMO-LUMO gap (from 4.86 to 3.29 eV). The electronic states of the HOMO mainly come from the 5s orbital of Ag atoms and 4s and 4p orbitals of the Ge7 cluster because the 0.48 a.u. charge transfer from the 5s orbital of Ag atoms to the 4s4p orbital of the Ge7 cluster as can be seen from Table 5.

Figure 12.

PDOSs for Ge7 and AgGe7 show a significant change in the PDOS at the Fermi level because of doping of Ag.

4. Conclusions

A systematic investigation of the silver-doped germanium clusters AgGen with n = 1–13 in the neutral, anionic, and cationic states is performed using the unbiased global search technique combined with the double-density functional scheme. The lowest-energy minima of the clusters are identified based on calculated energies and the measured PES. Total atomization energies and thermochemical properties such as EA, IP, binding energy, hardness, and HOMO-LUMO gap are obtained and compared with those of pure germanium clusters. The structural evolution for AgGenλ (n = 1–13; λ = −1, 0, and +1) emerges as follows: For neutral and anionic clusters, although the most stable structures are inconsistent when n = 7–10, the structure patterns both are exohedral structures except for n = 12, and a highly symmetrical endohedral configuration is formed when n = 12. For the cationic state, the most stable structures are attaching structures (in which an Ag atom is adsorbed on the Gen cluster or a Ge atom is adsorbed on the AgGen–1 cluster) at n = 1–12, and when n = 13, the cage configuration is formed. The analyses of binding energy indicate that doping of an Ag atom into the neutral and charged Gen clusters may decrease their stability. The EAs of AgGen clusters including AEAs and VDEs are presented and are in perfect agreement with the experimental values. The IP including VIP and AIP of neutral Gen clusters is decreased when doped with an Ag atom. The HOMO-LUMO gaps of neutral AgGen (n = 1–13) excluded n = 8 and 12 are larger than that of anionic clusters. For cationic states, the HOMO-LUMO gaps of AgGen+ are wider than that of AgGen for n = 1, 2, 4, and 6–10 and are narrower for n = 3, 5, and 11–13. The variant trend of the HOMO-LUMO gap and hardness versus cluster size is slightly different. The accuracy of the theoretical analyses in this paper is demonstrated successfully by the agreement between simulated and experimental results such as PES, IP, EA, and binding energy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21863007) and by the Science and Technology Plan Project in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Grant No. JH20180633).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Ravi P. Academic and Industry Research Progress in Germanium Nanodevices. Nature 2011, 479, 324–328. 10.1038/nature10678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong B. T.; Minh T. N. A Stochastic Search for the Structures of Small Germanium Clusters and Their Anions: Enhanced Stability by Spherical Aromaticity of the Ge10 and Ge122– systems. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 11190–11130. 10.1021/ct1006482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulusu S.; Yoo S.; Zeng X. C. Search for Global Minimum Geometries for Medium Sized Germanium Clusters: Ge12-Ge20. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 164305. 10.1063/1.1883647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei A. Predicting the Structural Evolution of Gen– (3≤n≤20) Clusters: an Anion Photoelectron Spectroscopy Simulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 25746–25751. 10.1039/C8CP04782K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S.; Fuke K. Photoionization Studies of Germanium and Tin Clusters in the Energy Region of 5.0-8.8 eV: Ionization Potentials for Gen (n=2-57) and Snn(n=2-41). J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 3880–3890. 10.1063/1.479691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich K. A.; Schmude R. W. Jr.; Baba M. S.; Meloni G. Atomization Enthalpies and Enthalpies of Formation of the Germanium Clusters, Ge5, Ge6, Ge7, and Ge8 by Knudsen Effusion Mass Spectrometry. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 7443–7448. 10.1063/1.481343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich K. A.; Baba M. S.; Schmude R. W. Jr.; Kingcade J. E. Jr. Atomization Enthalpies and Enthalpies of Formation of Ge3 and Ge4 by Knudsen Effusion Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Phys. 2000, 262, 65–74. 10.1016/S0301-0104(00)00271-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. M.; Fye J. L.; Jarrold M. F.; Bower J. E. Structural Transitions in Size-selected Germanium Cluster Ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 2063–2066. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. D.; Zhao Z. G.; Wu H. S.; Jin Z. H. Ionization Potentials, Electron Affinities, and Vibrational Frequencies of Gen (n=5-10) Neutrals and Charged Ions from Density Functional Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 9255–9259. 10.1063/1.1412878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi Y.; Kawamata H.; Hayakawa F.; Nakajima A.; Kaya K. The Infrared HOMO-LUMO Gap of Germanium Clusters. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 294, 370–376. 10.1016/S0009-2614(98)00874-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi Y.; Kawamata H.; Hayase T.; Gomei M.; Kishi R.; Hayakawa F.; Nakajima A.; Kaya K. Photoelectron Spectroscopy of Germanium-Fluorine Binary Clusteranions: the HOMO-LUMO Gap Estimation of Gen Clusters. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997, 269, 199–207. 10.1016/S0009-2614(97)00284-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton G. R.; Xu C.; Arnold C. C.; Neumark D. M. Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Zero Electron Kinetic Energy Spectroscopy of Germanium Cluster Anions. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 2757–2764. 10.1063/1.471098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kingcade J. E.; Nagarathna-Naik H. M.; Shim I.; Gingerich K. A. Electronic Structure and Bonding of the Molecule Ge2 from All-Electron ab Initio Calculations and Equilibrium Measurements. Phys. Chem. 1986, 90, 2830–2834. 10.1021/j100404a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur K.; Bernard H. S. Atomization Energies of the Polymers of Germanium, Ge2 to Ge7. J. Chem. Phys. 1966, 45, 822–826. [Google Scholar]

- Hostutler D. A.; Li H. Y.; Clouthier D. J.; Wannous G. Exploring the Bermuda Triangle of Homonuclear Diatomic Spectroscopy: The Electronic Spectrum and Structure of Ge2. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116, 4135–4141. 10.1063/1.1431281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Du Q.; Zhou S.; Kumar V. Endohedrally Doped Cage Clusters. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 9021–9163. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siouani C.; Mahtout S.; Rabiloud F. Structure, Stability, and Electronic Properties of Niobium-Germanium and Tantalum-Germanium Clusters. J. Mol. Model. 2019, 25, 113. 10.1007/s00894-019-3988-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasmi M.; Mahtout S.; Rabilloud F. The Effect of Palladium and Platinum Doping on the Structure, Stability and Optical Properties of Germanium Clusters: DFT Study of PdGen and PtGen (n=1-20) Clusters. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2020, 1181, 112830. 10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtout S.; Siouani C.; Rabilloud F. Growth Behavior and Electronic Structure of Noble Metal-Doped Germanium Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 662–677. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b09887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siouani C.; Mahtout S.; Safer S.; Rabilloud F. Structure, Stability, and Electronic and Magnetic Properties of VGen(n = 1–19) Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 3540–3554. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b00881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atobe J.; Koyasu K.; Furusea S.; Nakajima A. Anion Photoelectron Spectroscopy of Germanium and Tin Clusters Containing a Transition- or Lanthanide-Metal Atom; MGen– (n= 8-20) and MSnn– (n=15-17) (M = Sc-V, Y-Nb, and Lu-Ta). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 9403–9410. 10.1039/c2cp23247b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y. K.The Electronic Structures and Properties of Transition Metal Doped Si, Ge Clusters and Ag-BO2 clusters .Ph.D. Dissertation, Institute of Chemistry, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Deng X. J.; Kong X. Y.; Xu X. L.; Xu H. G.; Feng X. G.; Zheng W. J. Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Calculations of VGen– (n=3-12) Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 11048–11055. 10.1021/jp511694c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X. J.; Kong X. Y.; Xu X. L.; Xu H. G.; Zheng W. J. Structural and Magnetic Properties of CoGen– (n=2-11) Clusters: Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Calculations. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2014, 15, 3987–3993. 10.1002/cphc.201402615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X. J.; Kong X. Y.; Xu H. G.; Feng X. G.; Zheng W. J. Structural and Magnetic Properties of FeGen–/0 (n=3-12) Clusters: Mass-Selected Anion Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Theory Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 147, 234310. 10.1063/1.5000886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S. J.; Hu L. R.; Xu X. L.; Xu H. G.; Chen H.; Zheng W. J. Transition from Exohedral to Endohedral Structures of AuGen– (n=2-12) Clusters: Photoelectron Spectroscopy and ab initio Calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 20321–20329. 10.1039/C6CP00373G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X. J.; Kong X. Y.; Xu X. L.; Xu H. G.; Zheng W. J. Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Calculations of TiGen– (n=7-12) Clusters. Chin. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 29, 123–128. 10.1063/1674-0068/29/cjcp1511232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X. J.; Kong X. Y.; Xu X. L.; Xu H. G.; Zheng W. J. Structural and Bonding Properties of Small TiGen– (n=2-6) Clusters: Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Calculations. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 25963–25968. 10.1039/C4RA02897J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S. J.; Farooq U.; Xu H. G.; Xu X. L.; Zheng W. J. Structural Evolution and Electronic Properties of Au2Gen-1/0 (n=1-8) Clusters: Anion Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Theoretical Calculations. Chin. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 32, 229–240. 10.1063/1674-0068/cjcp1902036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. Q.; Deng X. J.; Lu S. J.; Huang X. M.; Zhao J. J.; Xu H. G.; Zheng W. J. Probing Structural, Electronic, and Magnetic Properties of Iron-Doped Semiconductor Clusters Fe2Gen–/0 (n=3-12) via Joint Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 7037–7046. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. Q.; Kong X. Y.; Lu S. J.; Huang X. M.; Zhao J. J.; Xu H. G.; Zheng W. J. Structural Evolution and Magnetic Properties of Anionic Clusters Cr2Gen (n=3-14): Pphotoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Theory Computation. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2018, 30, 335501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham L. N.; Nguyen M. T. Titanium Digermanium: Theoretical Assignment of Electronic Transitions Underlying its Anion Photoelectron Spectrum. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 1940–1949. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham L. N.; Nguyen M. T. Insights into Geometric and Electronic Structures of VGe3–/0 Clusters from Anion Photoelectron Spectrum Assignment. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 6949–6956. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b07459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X. J.; Gopakumar G.; Lievens P.; Nguyen M. T. Chromium-Doped Germanium Clusters CrGen (n=1-5): Geometry, Electronic Structure, and Topology of Chemical Bonding. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 13544–13553. 10.1021/jp0773233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V. T.; Tran Q. T. Electronic Structures of NbGen–/0/+ (n=1-3) Clusters from Multiconfigurational CASPT2 and Density Matrix Renormalization Group-CASPT2 Calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2020, 41, 2641–2652. 10.1002/jcc.26420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V. T.; Tran Q. T. Spin State Energetics of VGen–/0 (n=5-7) Clusters and New Assignments of the Anion photoelectron Spectra. J. Comput. Chem. 2018, 39, 2103–2109. 10.1002/jcc.25527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. G.; Ma L.; Zhao J. J.; Wang G. H. Structural Growth Sequences and Electronic Properties of Manganese-Doped Germanium Clusters: MnGen (2-15). J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 335223. [Google Scholar]

- Kapila N.; Garg I.; Jindal V. K.; Sharma H. First Principle Investigation into Structural Growth and Magnetic Properties in GenCr Clusters for n=1-13. J. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 2885–2893. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2012.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R.; Dhaka K.; Bandyopadhyay D. Study of Electronic Properties, Stabilities and Magnetic Quenching of Molybdenum-Doped Germanium Clusters: a Density Functional Investigation. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 64825–64834. 10.1039/C4RA11825A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triedi R. K.; Bandyopadhyay D. Insights of the Role of Shell Closing Model and NICS in the Stability of NbGen (n=7-18) Clusters: a First Principles Investigation. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 515–528. 10.1007/s10853-018-2858-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay D.; Sen P. Density Functional Investigation of Structure and Stability of Gen and GenNi (n=1-20) Clusters: Validity of the Electron Counting Rule. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 1835–1842. 10.1021/jp905561n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay D.; Kaur P.; Sen P. New Insights into Applicability of Electron-Counting Rules in Transition Metal Encapsulating Ge Cage Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 12986–12991. 10.1021/jp106354d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M.; Bhattacharyya N.; Bandyopadhyay D. Architecture, Electronic Structure and Stability of TM@Ge(n) (TM=Ti, Zr and Hf; n=1-20) Clusters: a Density Functional Modeling. J. Mol. Model. 2012, 18, 405–418. 10.1007/s00894-011-1122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay D. Architectures, Electronic Structures, and Stabilities of Cu-Doped Gen Clusters: Density Functional Modeling. J. Mol. Model. 2012, 18, 3887–3902. 10.1007/s00894-012-1374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay D. Electronic Structure and Stability of Anionic AuGen (n=1-20) Clusters and Assemblies: A Density Functional Modeling. Struct. Chem. 2019, 30, 955–963. 10.1007/s11224-018-1239-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borshch N. A.; Pereslavtseva N. S.; Kurganskii S. I. Spatial Structure and Electron Energy Spectra of ScGen– (n=6-16) Clusters. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 9, 9–18. 10.1134/S1990793115010030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borshch N. A.; Kurganskii S. I. Atomic Structure and Electronic Properties of Anionic Germanium-Zirconium Clusters. Inorg. Mater. 2018, 54, 1–7. 10.1134/S0020168518010028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borshch N. A.; Kurganskii S. I. Spatial Structure and Electron Energy Spectrum of HfGen– (n=6-20) Clusters. Inorg. Mater. 2015, 51, 870–876. 10.1134/S0020168515080075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borshch N. A.; Kurganskii S. I. Anionic Germanium-Niobium Clusters: Atomic Structure, Mechanisms of Cluster Formation, and Electronic Spectra. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 92, 1720–1726. 10.1134/S0036024418090078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borshch N. A.; Pereslavtseva N. S.; Kurganskii S. I. Spatial and Electronic Structures of the Germanium-Tantalum Clusters TaGen– (n=8-17). Phys. Solid. State 2014, 56, 2336–2342. 10.1134/S1063783414110055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal S.; Kumar V. Growth Behavior and Electronic Structure of Neutral and Anion ZrGen(n=1-21) Clusters. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016, 1075, 87–97. 10.1016/j.comptc.2015.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R.; Bandyopadhyay D. Evolution of Electronic and Vibrational Properties of M@Xn (M=Ag, Au, X=Ge, Si, n=10, 12, 14) Clusters: a Density Functional Modeling. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 8263–8273. 10.1007/s10853-018-2002-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R.; Mishra V. Exploring the Structural Stability Order and Electronic Properties of Transition Metal M@Ge12 (M=Co, Pd, Tc, and Zr) Doped Germanium cage clusters – A Density Functional Simulation. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1226, 129371 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W.; Lu W. C.; Xia L. H.; Zhao L. Z.; Zang Q. J.; Wang C. Z.; Ho K. M. Structures and Stability of Metal-Doped GenM (n=9, 10) Clusters. AIP. Adv. 2015, 5, 067159 10.1063/1.4923316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Dolg M. ABCluster: the Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm for Cluster Global Optimization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 24173–24181. 10.1039/C5CP04060D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Dolg M. Global Optimization of Clusters of Rigid Molecules Using the Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 3003–3010. 10.1039/C5CP06313B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Glezakou V. A.; Rousseau R.; Nguyen M. T. NWPEsSe: an Adaptive-Learning Global Optimization Algorithm for Nanosized Cluster Systems. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16, 3947–3958. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b01107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.;. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision C.01,Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Toward Reliable Density Functional Methods without Adjustable Parameters: The PBE0 Model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hay P. J.; Wadt W. R. Ab Initio Effective Core Potentials for Molecular Calculations. Potentials for the Transition Metal Atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 270–283. 10.1063/1.448799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson K. A.; Puzzarini C. Systematically Convergent Basis Sets for Transition Metals. II. Pseudopotential-Based Correlation Consistent Basis Sets for the Group 11 (Cu, Ag, Au) and 12 (Zn, Cd, Hg) Elements. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2005, 114, 283–296. 10.1007/s00214-005-0681-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson K. A. Systematically Convergent Basis Sets with Relativistic Pseudopotentials. I. Correlation Consistent Basis Sets for the Post-d Group 13-15 Elements. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 11099–11112. 10.1063/1.1622923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe T.; Grimme S. Towards Chemical Accuracy for the Thermodynamics of Large Molecules: New Hybrid Density Functionals Including Non-local Correlation Effects. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 4398–4401. 10.1039/b608478h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. K.; Woon D. E.; Peterson K. A.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. IX. The Atom Gallium through Krypton. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 7667–7676. 10.1063/1.478678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Yang J.; Cheng L. Structural Stability and Evolution of Scandium-Doped Silicon Clusters: Evolution of Linked to Encapsulated Structures and Its Influence on the Prediction of Electron Affinities for ScSin(n=4-16) Clusters. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 12934–12940. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neckel A.; Sodeek G. Bestimmung Der Dissoziationsenergien Der Gasformigen Molekule CuGe, AgGe and AuGe. Monatsh. Chem. 1972, 103, 367–382. 10.1007/BF00912960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Wang X.; Yang J. Comparative Research of Configuration, Stability and Electronic Properties of Cationic and Neutral [AuGen]λ and [Gen+1]λ (n=1-13, λ=0,+1). Mater. Today. Commun. 2021, 26, 101989 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.; Chen F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]