Abstract

In the current work, some metallabenzenes with one and several fused rings were analyzed in terms of their electronic delocalization. These fused-ring metallabenzenes are known as metallabenzenoids, and their aromatic character is not free of controversy. The systems of the current work were designed from crystallographic data of some synthesized molecules, and their electronic delocalization (aromaticity) was computationally examined in terms of the molecular orbital analysis (Hückel’s rule), the induced magnetic field, and ring currents. The computational evidence allows us to understand if these molecules are or are not aromatic compounds.

1. Introduction

It was in 1825 when Faraday isolated benzene,1 the archetypal of aromatic molecules. In 1979 (more than 150 years after Faraday’s work), Thorn and Hoffman predicted theoretically that metallabenzenes and other conjugated metallacyclic compounds (with six π electrons) would present an aromatic behavior due to their electronic delocalization.2 Metallabenzenes are benzenes with a CH unit of the aromatic ring replaced by one metal fragment; both chemical units are isolobal analogues [similar energy and shape of their frontier molecular orbitals (MOs)].3 Elliot, Roper, and Waters reported the first metallabenzene (an osmabenzene) only 3 years later (1982).4−6 The next metallabenzene reported was ferrobenzene, described by Stone et al.7 Ernst et al. reported molybdenabenzene,8 and Bleeke et al. published the experimental detection of iridabenzenes,9−11 the second largest group of metallabenzenes. The heterometallabenzenes are generated when one CH unit in metallabenzene is replaced by a heteroatom, such as oxygen, sulfur, or nitrogen,12 for example, metallapyryliums,13,14 metallapyridines,15 and metallathiabenzenes.16 Other systems, such as dimetallabenzenes, have been synthesized.17,18 The dimetallabenzenes are benzenes with two CH units of the six-membered ring replaced with two transition metal fragments.

Fused-ring metallabenzenes are known as metallabenzenoids. Unlike the “classical” metallabenzenes, where the electron delocalization of the majority of them are relatively well established but still under discussion, the electronic delocalization of fused-ring metallabenzenes has not been confirmed yet due to limited data.

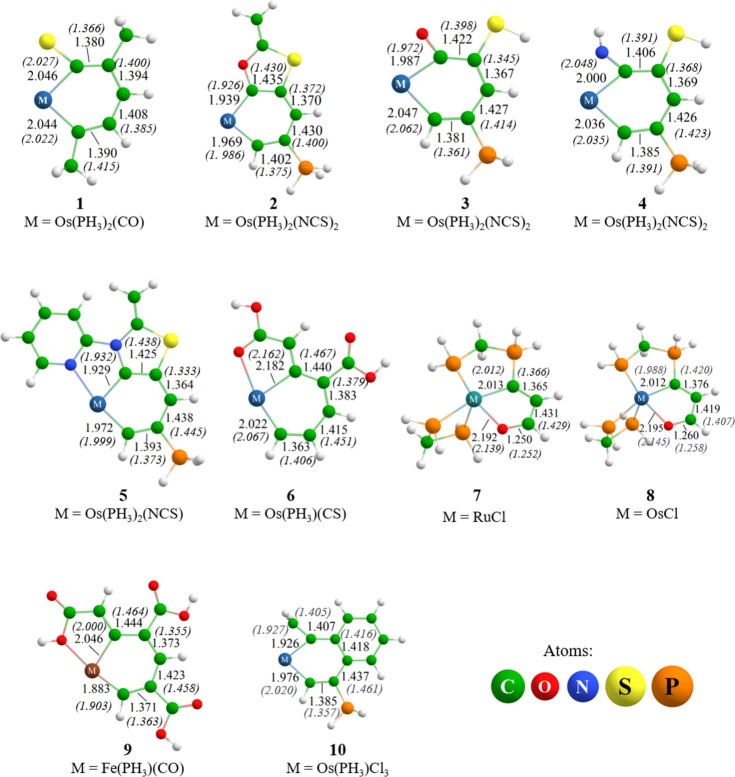

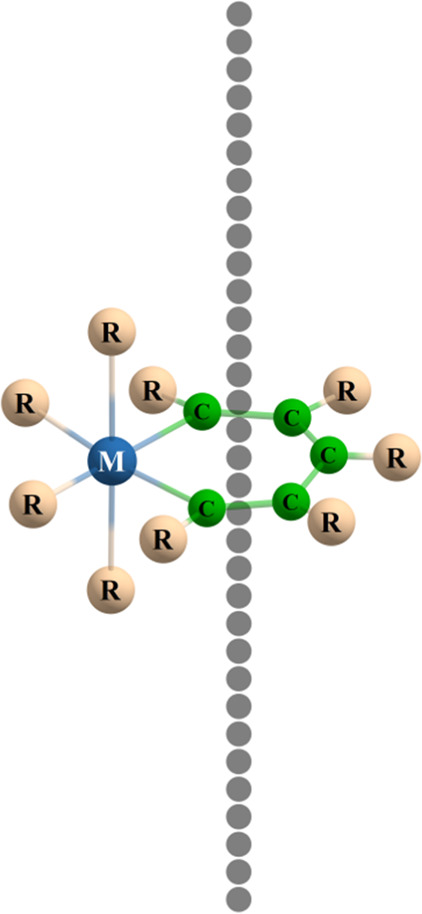

Figure 1 shows the different kind of metallabenzenoids analyzed in the current work, classified according to the size of the secondary ring (three-, five-, or six-membered ring).

Figure 1.

Metallabenzenoids with a second ring fused. Scheme (A) for M = Os and E = S, N, or O. Scheme (B) for M = Fe or Os and E = O. Scheme (C) for M = Os and E = N or O. Scheme (D) for M = Os.

The first category of metallabenzenoids is the three-membered fused-ring family (see structure A in Figure 1). Some examples of this family were reported by Elliot et al. in 198919 and Rickard et al. in 2001;20 in their respective works, they reported osmabenzene fused with one S atom (forming a three-membered ring). The structural analysis of these molecules suggests electronic delocalization of the metallacycle (equalized length bonds). Furthermore, the typical chemical reactions such as nucleophilic aromatic substitution and electrophilic aromatic substitution were observed.21 Similarly, osmabenzenes with O and N substitutions22 present typical bond lengths of aromatic compounds (length equalization). Thus, it could be concluded, experimentally, that double fused-ring osmabenzenes exhibit the chemical characteristics of an aromatic compound such as electrophilic aromatic substitution.23

The second category of metallabenzenoids is the family of osmabenzenes fused with five-membered rings (depicted as B and C in Figure 1). It was also experimentally reported that this set presents typical aromatic reactions24 such as electrophilic substitution25 and geometrical characterization of an aromatic-like system such as planarity and bond length equalization.6 In this set, two different structures for the fused ring are depicted: the molecule labeled as B in Figure 1 has only one heteroatom denoted as E. When M = Os and E = O, the name of this molecules is osmabenzofurane, and this family was previously synthesized by Clark and co-workers.26 The metallabenzenoid denoted as C in Figure 1 was reported by Wang et al. in 2013 with M = Os and E = N and O.22 There is a lack of theoretical calculations about their aromatic character. Nevertheless, the authors classified this set of molecules to higher π-electron metal aromatic compounds without any further information.

Finally, the third category of metallabenzenoids is depicted as D in Figure 1. This category corresponds to metallanaphthalenes. Osmanaphthalene was synthesized by Chu et al. in 2019. In that work, they reported the possible aromatic behavior of osmanaphthalene based on structural parameters (planarity and bond lengths) and typical 1H NMR shifts for aromatic compounds.27

In general, the participation of the metal’s d atomic orbitals in the electronic delocalization is the main difference between the aromaticity of the classic organic rings and the aromaticity of the metallacycles.

In all cases mentioned above, the aromatic character of the molecules is still under discussion, and the electronic delocalization, as previously mentioned, has not been confirmed yet due to limited data. It has been shown that metallabenzenoids have a degree of aromatic character (always less than benzene) based on geometrical parameters (planarity and bond length equalization) and the characteristic 1H NMR shifts.

Computationally, nucleus-independent chemical shifts, or NICS,28,29 are widely employed as an aromaticity criterion: negative values indicate a diatropic behavior associated with aromatic compounds. In metallabenzenes, NICS values must be carefully interpreted due to the anisotropy of the metal fragments,30,31 which can generate false or more negative NICS values.32

The number of well-characterized metallabenzenes remains low and restricted to Os, Ir, and Pt metals.33 These compounds show significant optical or electronic properties,34 playing an important role in the nonlinear optical properties and having potential application in electro-optics and photonics.

In the current work, the electronic delocalization of some metallabenzenoids has been studied by employing in silico methodologies based on the magnetic response of the molecules (vide infra). The systems were selected from synthesized molecules (crystallographic data).

The aim of this research is the confirmation of the electronic delocalization importance in the stability of this set of fused metallacycles. Some previous studies include monocyclic metallabenzenes analyzed by Periyasamy et al.35 and some five-membered metallacycles studied by Islas, Poater, and Solà.36,37

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Details

2.1.1. Geometry Details

The systems analyzed in the current work are depicted in Figure 2. Only bond lengths of the delocalized rings are indicated in Å. For all the systems, the analyzed rings were the six-membered rings (6 MRs), except for 10 and 11, in which the five-membered rings (5 MRs) were the analyzed rings. Also, in Figure 2, the bond distances (in parenthesis and italic) of the experimental rings are depicted for comparison. The rings’ bond lengths of the optimized geometries were in agreement with their experimental counterparts.20,22,26,27,38,39 The osmabenzenes 1, 3, and 4 are monocycles, and they presented similar lengths in their Os–C bonds (around 2 Å). Also, the C–C bonds of the delocalized rings were in agreement with the experimental counterparts. In the fused osmacycles, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 10, and in the fused ruthenium cycle (7) and the ferrocycle (9), the metal–carbon bonds lengths were also around 2 Å.

Figure 2.

Structures of systems analyzed in the current work. The bond lengths are reported in Å. Only bond lengths of the delocalized rings are depicted. The values in parentheses and italic type numbers are the bond lengths reported for the experimental rings.

All the geometries presented planar rings, except for 2, 4, and 6. In Table 1, some selected dihedral angles are reported, where the groups [Os(PH3)2(NCS)2] and [Os(PH3)2(CS)] are represented by M for better depiction. These rings were slightly distorted, but they were analyzed by Bzind and magnetically induced current density (MICD) methodologies.

Table 1. Selected Dihedral Angles of 2, 4, and 6a.

Angle measures are absolute values. The column titled “dihedral” represents the dihedral angles of each system.

2.1.2. Electron Structure Details

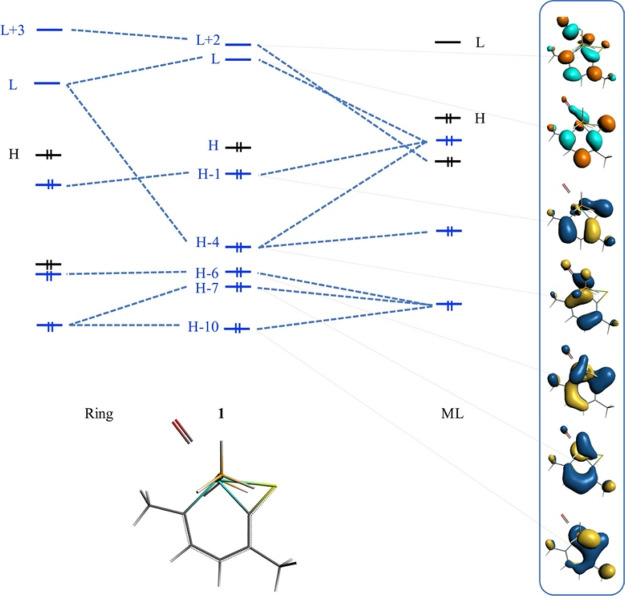

The number of π electrons involved in metallabenzenes has been under discussion. Some authors observe the shape of the highest occupied MO (HOMO), lowest unoccupied MO (LUMO), HOMO – 1, and HOMO – 9, which are homologous to the π MOs from benzene.32 Thorn and Hoffmann, in their original work,2 suggested a six-π electron structure to follow Hückel’s rule for metallabenzenes, while systems such as rhodabenzene have 10-π electrons,40 following Hückel’s rule. In the metallabenzenoids with fused rings, a deep observation of the electronic structure was made, alongside the energy decomposition analysis. The π-electron counting for this set, as well as for metallabenzenes, is not a trivial task. In this counting, all the MOs that involve π symmetry over the rings (totally or partially) were taken into account. All systems under discussion presented a clear π MO structure homologous to that of benzene (or furan in 5 MRs), and they followed Hückel’s rule with 3, 5, 7, or 9 π-type doubly occupied MOs, that is, 6, 10, 14, and 18 π electrons, respectively. Figure 3 shows the MO diagram for 1, where the π space depicts five occupied MOs with 10 π electrons, following Hückel’s rule with n = 2. All MO diagrams are in the Supporting Information, and the MO under interest as well as Hückel’s rule for all molecules is condensed in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Qualitative MO diagram for 1. Only the π space is represented. H and L represent HOMO and LUMO, respectively. For completeness, the MOs without π interest have been incorporated as black lines, while red lines relate the MO figure with the diagram.

Table 2. π MO Description for All Moleculesa.

| molecule | Hückel (n) | π electrons | π-ocupied MO |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 10 | H-1, H-4, H-6, H-7, H-10 |

| 2 | 3 | 14 | H-4, H-7, H-8, H-9, H-10, H-12, H-18 |

| 3 | 3 | 14 | H-3, H-4, H-6, H-8, H-9, H-15, H16 |

| 4 | 2 | 10 | H-4, H-6, H-8, H-10, H-16 |

| 5 | 3 | 14 | H-2, H-5, H-6, H-8, H-9, H-11, H-13 |

| 6 | 3 | 14 | H, H-4, H-7, H-8, H-9, H-12, H-13 |

| 7 | 1 | 6 | H-3, H-8, H-18 |

| 8 | 1 | 6 | H-3, H-8, H-18 |

| 9 | 3 | 14 | H, H-2, H-3, H-8, H-9, H-10, H-12 |

| 10 | 4 | 18 | H, H-2, H-6, H-7, H-10, H-11, H-12, H-13, H-15 |

Where the n from Hückel’s rule is presented, along with the π electrons involved as well as the π-occupied MOs.

As expected, molecules 7 and 8 completed Hückel’s rule with n = 1 because the principal ring is furan and not benzene as in other systems. Furthermore, the fused ring does not have a planar structure and does not contribute to the π space under discussion.

Molecules 1 and 4 completed Hückel’s rule with n = 2 similar to a classical metallabenzene with 10 π electrons. Molecules 2, 3, 5, 6, and 9 expanded their π space with the fused ring and completed Hückel’s rule with n = 3. Finally, 10 presented the bigger fused ring, resulting in a bigger π space with n = 4. 10 also is a perfect example of Clar’s rule, as explained previously by metallatricycles, due to its polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-like structure, while all the other systems studied are not.41 Thus, it can be concluded that, from Hückel’s rule, all the systems of the current work could be considered as aromatic molecules with different π MOs.

To explore the possible Möbius character of the systems and the Möbius aromaticity, the Mauksch and Tsogoeva relationship was used.42 Not only the HOMO but also the whole π space was observed. As expected, some metal contributions to π MOs belong to phase dislocation, but none of them contribute above 10% to the π MO (except for 9 with 30% Möbius character and 70% π character). The contributions of d orbitals to the HOMO are mainly from dx2–y2 and dxy orbitals, which belong to σ symmetry. Thus, none of the molecules exhibit a defined Möbius behavior but present a low Möbius character in the low-lying π MOs.

To quantify these interactions in the MO diagrams, an energy decomposition analysis was done, where two fragments were selected, each fragment with singlet spin multiplicity. The first fragment corresponds to the metal and their ligands (ML) and the second fragment to the ring and their ligands (ring). The interactions computed, as referred to in the Computational Details section, are collected in Table 3. Molecules 6 and 9 had the highest orbital contribution to interaction energy. This ΔEorb was higher than ΔEele due to the interaction between the metal and oxygen in the second ring. All other molecules presented a slightly higher electrostatic contribution than the orbital one, except molecule 2, where the ratio electrostatic/orbital was about 6/4.

Table 3. EDA for All Moleculesa.

| molecule | net charge | ML charge | ring charge | ΔEpau | ΔEele | ΔEorb | ΔEdis | ΔEint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 544.64 | –380.42 | –327.29 | –10.35 | –173.19 |

| 53.76% | 46.24% | |||||||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 444.36 | –374.21 | –266.80 | –11.04 | –207.69 |

| 58.38% | 41.62% | |||||||

| 3 | 1 | 2 | –1 | 366.39 | –416.99 | –411.70 | –8.51 | –471.04 |

| 50.32% | 49.68% | |||||||

| 4 | 1 | 2 | –1 | 386.63 | –444.82 | –418.6 | –9.2 | –485.99 |

| 51.52% | 48.48% | |||||||

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 684.94 | –485.53 | –479.78 | –12.65 | –292.79 |

| 50.31% | 49.69% | |||||||

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 566.26 | –350.06 | –408.71 | –10.35 | –203.09 |

| 46.13% | 53.87% | |||||||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 355.81 | –270.94 | –243.34 | –10.58 | –169.05 |

| 52.69% | 47.31% | |||||||

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 575.00 | –403.65 | –379.90 | –10.35 | –236.90 |

| 50.35% | 49.65% | |||||||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 508.07 | –299.23 | –404.57 | –11.73 | –207.46 |

| 42.53% | 57.47% | |||||||

| 10 | 0 | 1 | –1 | 537.28 | –486.68 | –447.58 | –8.51 | –405.72 |

| 52.09% | 47.91% |

Energy is presented in kcal/mol. The charge of each fragment (ML = metal and its ligands) is depicted as well as the total charge.

Due to the possible double interaction of ML with both rings, a visual inspection of the NOCVs is mandatory and useful to understand the interaction between each ML fragment and the ring. Figure 4 shows the first NOCV for 1. This NOCV corresponds to the deformation density of the orbital part of EDA, Δρσorb. This deformation has σ symmetry and presented two important blue zones (“accumulation of electron density” zones). In Figure 4, the color code indicates that the charge flows from red zones to blue zones (from the metal to C and S), though C and S also gave electron density to the metal. This donation to the central zone indicates σ-bond formation. The same situation was depicted for all molecules in the σ symmetry of the deformation density NOCV (see the Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

First NOCV (contour isovalue = 0.003 a.u.) for 1. Hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity.

In some cases, the formation of those sigma bonds requires a reorganization of the electron density from the metal d orbitals. Figure 5 (left) shows the reorganization from the dxy symmetry density to a dx2–y2-like NOCV combined with a flux of charge from both rings to ML fragments. Figure 5 (right) depicts the π symmetry of the NOCV, showing the flux charge from the dyz -like density to the pz of the rings.

Figure 5.

NOCV of 5. (left) Reorganization of the electron density is depicted in σ symmetry and (right) π symmetry Δρπorb. Contour isovalue = 0.003 a.u. and the charge flows from red zones to blue zones.

Furthermore, the flux charge between the ML and the rings can expose backdonation, as depicted in Figure 6. A σ-bond was formed between the metal and carbon from the six-membered ring, while a backdonation is required to form a σ-bond between the metal and oxygen of the five-membered fused ring. Thus, in all cases where the fused ring has a bond between the metal and oxygen or nitrogen, a backdonation process was observed.

Figure 6.

First NOCV (sigma symmetry) for 6. Contour isovalue = 0.003 a.u. The flux charge goes from red zones to blue zones.

The first and the second NOCV for all molecules depict the σ symmetry as well as the π symmetry, exposing the bond between the metal and the six-membered ring. In the fused rings with direct interaction with the metal, a backdonation from oxygen or nitrogen is required, while in the π symmetry, a d-type adapted density from the metal gives electron density to the π space of the rings. All NOCVs are collected in the Supporting Information.

2.2. Electronic Delocalization

2.2.1. Induced Magnetic Field

The induced magnetic field was employed in this set of metallic cycles. As mentioned in the Computational Details section, its z-component or Bzind was used in the current work. The more negative Bz values are, the more diatropic the system is. It was appreciable that the diatropic response of the rings is around 1 Å over and below the molecular plane. All the molecules analyzed in the current work presented negative values of Bzind, indicating a diatropic behavior associated with aromatic compounds (see Figure 7). Benzene43 and borazine44 were employed as references of aromatic and “weak-aromatic” molecules, respectively. (Borazine is used as a reference of weak aromaticity in this work because it is not as equally delocalized as benzene due to the difference in electronegativities of boron and nitrogen atoms.)44 All the metallabenzenoids analyzed in this work presented a higher diatropic behavior if their Bz values were compared with borazine’s values. The benzene values at R = 0 (molecular plane) and R = 1 (1 Å over the molecular plane) were −7.2 and −10 ppm, respectively. All the systems showed smaller Bzind values than benzene, except 3 and 9. The system labeled as 3 had the same value as benzene at the molecular plane, but it was smaller in other points.

Figure 7.

Bzind profiles are depicted and split into two sets for clarity. The orientation of the molecules has been described in Scheme 1: the molecular plane was placed on the xy plane, perpendicular to the z axis. The external magnetic field was oriented parallel to the z axis.

Around 2.5 Å above or below some systems, the presence of phosphine groups ensured that the Bzind values decrease; this is due to the high electron density around the P nuclei and their contribution to the diamagnetic response when an external magnetic field was applied, especially in the systems 2 and 9. This phenomenon is observed in the asymmetry of the plots (Figure 7): the low symmetry of the plot was generated by the orientation of the phosphine groups. In Figure 8, this situation in 9 is depicted; the blue arrows signalize the zones where the Bz values were computed close to the phosphine groups. In spite of these values, both systems could be labeled as diatropic systems.

Figure 8.

The blue arrows signalize the zones where the Bzind values were computed close to the phosphine groups in 9. The pink spheres marked with X represent the points in the space where Bz was calculated.

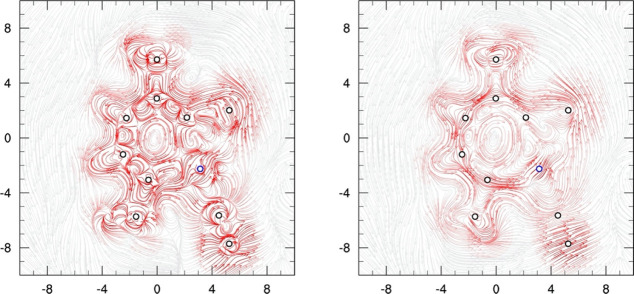

2.2.2. Magnetically Induced Current Densities

The 4-component relativistic calculation of the MICD was previously exploited by Bast, Jusélius, and Saue in the DIRAC package45 and is related with the aromaticity of a system.46 The two-dimensional (2D) plots exhibit the current density of a system in the molecular plane as well as at 1 a0 above the molecular plane. Figure 9 shows that for 1, in the inner part of the metallabenzene, a clockwise current is depicted, while in the outer part, a counterclockwise flux is sustained. This behavior is analogous to that of the benzene molecule (our aromatic reference). The total current strength density is diatropic, suggesting an aromatic behavior of the system.

Figure 9.

MICD for 1. Left: MICD plotted at the molecular plane, and right: MICD placed at 1.0 a0 from the molecular plane. Line intensity is proportional to the norm of the current density vector. The diatropic current goes in the counterclockwise direction. The blue circle belongs to the metal atom.

In this sense, all molecules were cataloged with a diatropic local current density in the metallabenzene part. The second fused ring did not present a diatropic local current density but presents an inner paratropic current (the streamlines of MICD from all molecules were collected in the Supporting Information). To have a complete picture, the strength of the current density was conveniently measured in a plane that bisects the bond between carbon atoms in positions 3 and 4 in the metallabenzene ring, and it is extended in step sizes of 0.1 a0 up to 15 a0, avoiding the cores due to the high diatropic response of atomic nuclei.

Figure 10 shows the strength current path of each molecule. Negative values reference paratropic behavior. The integration plane was extended through the z axis to 8 Å (R value in the plot represents the steps of integration), where the first steps showed the σ nature of the ring current strength.

Figure 10.

Strength current path of each molecule studied. Borazine and benzene are incorporated as references of weak-aromatic and aromatic molecules, respectively. Molecule 9 is outside the plot for clarity with a final value of 26.00 nA/T.

As predicted by the MO analysis and Bzind, all molecules could be considered as delocalized systems according to the ring current criterion. Molecule 9, as expected by Bz, had the largest value in current density (26.00 nA/T). This could be attributed to the atom size (Fe), allowing the delocalization above the molecular plane, combined with the phosphine groups in both sides above the ring, as explained previously for 2 and 9. These phosphine groups were unavoidable, and as expected, close to atomic nuclei, a big diatropic response is observed, that is, the current density can be very large and nonuniform, overestimating the diatropic integration on the molecule. The phosphine groups were avoided in other molecules such as 4 and 6. Both of them presented lower values of strength current compared with borazine. All the other molecules presented less strength current than benzene but higher than borazine. Finally, 6 presented a local paratropic strength close to the molecular ring but a total diatropic strength current density.

3. Conclusions

The geometries of all the systems analyzed here are in good agreement with their experimental counterparts. All molecules present a π MO structure homologous to that of benzene. Also, the systems follow Hückel’s rule (4n +2 π electrons, with n = 1,2,3,4), but aromaticity is a multi-scale property, and several criteria were employed in the analysis of the electronic delocalization of the systems. Furthermore, the analysis was focused only on one of the several rings in the fused systems due to the lack of diatropic current densities in the fused ring. The σ bond as well as the π bond was formed between the metal and the rings. A classical bond is observed between the metal and carbon from the ring. Nevertheless, for the second ring, if there is oxygen or nitrogen, a backdonation is required to form the sigma bond. Otherwise, in the π symmetry, a d-type adapted density from the metal gives electron density to the π space of the rings.

According to the induced magnetic field (Bzind) results, all the molecules could be cataloged as diatropic systems. All of these are more diatropic than borazine, the weak-aromatic compound used as the reference in this work. However, phosphines groups could “interfere” in this measurement (such as in 2 and 9) due to the diatropic contribution of atomic nuclei; for this reason, the MICD analysis was performed.

MICD suggests that a total diatropic behavior in all the systems, the strength of the current density at 4-component, would give a more accurate interpretation of the diatropic response in the magnetic regime. The non-planar rings in 4 and 6 are diatropic with the Bzind results, but the MICD values indicate a weakly aromatic response if the total strength current is integrated. If the current path integration is observed, close to the molecular ring plane, an antiaromatic behavior is depicted. Thus, locally, it can be cataloged as antiaromatic, but the total strength current suggests a low diatropic response, showing a weakly aromatic behavior. On the other hand, it is expected that 9 behaves less aromatically than benzene if phosphine groups are not taken into account; this has been previously observed in pyramidal benzene structures.31 Nevertheless, 9 would probably have a higher aromatic character than borazine due to geometrical effects. All the other molecules are clearly aromatic systems, with their respective diatropic ring current and positive integral values of strength current density.

4. Computational Details

All crystallographic data were obtained from their file published previously by their respective research groups. The crystallographic data were modified in order to reduce the computational cost, changing phenyl or other bigger groups by hydrogens. These new models were optimized in the framework of amsterdam density functional (ADF 2014) code47 with the M06-L functional48 and the all electron TZVP basis of Slater-type orbitals for the metal atom and the TZVP basis set for the non-metal atoms,49 alongside the inclusion of Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction.50

These optimized models were used as the basis to construct the MO diagram to explain Hückel’s rule for aromatic compounds based on a relativistic wave function at the M06-L functional using the Kohn–Sham formalism.51 Also, the zero-order regular approximation52 was employed to take into account scalar relativistic effects. This MO construction was based in the fragments ML (metal with its ligands) and the rings, which helps us to understand the interaction between the fragments through an analysis of bonding energies, combining a fragmented approach to the molecular structure with the decomposition of the interaction energy between fragments according to the Morokuma–Ziegler analysis (EDA decomposition scheme). This interaction between fragments was decomposed as

where ΔEpau, ΔEele, ΔEorb, and ΔEdis represent Pauli repulsion, electrostatic interaction, orbital-mixing terms, and dispersion correction, respectively.53,54

This Morokuma–Ziegler analysis was combined with the extended transition state theory with the natural orbital of chemical valence (ETS–NOCV)55 to have a better description of the ΔEorb in order to set up the interaction between the metal and the ring(s). Each fragment of the EDA is represented by a set of NOCVs, extracting the deformation density, Δρ, in the NOCV representation as a sum of complimentary pairs of eigenfunctions (ψ–k, ψk) with their respective eigenvalues.

where k goes over NOCV pairs and A and B belong to each fragment. The visualization of deformation density provides information of the density charge flows, as well as the symmetry involved. In this work, the density charge flows from the red zones (Δρ < 0) to the blue zones (Δρ > 0). Furthermore, energetic estimations can be done for each Δρk. Thus, the orbital interaction component ΔEorb is expressed as

where the ±F±kTS are the diagonal matrix elements from the Khon–Sham transition state with their respective eigenvalues.

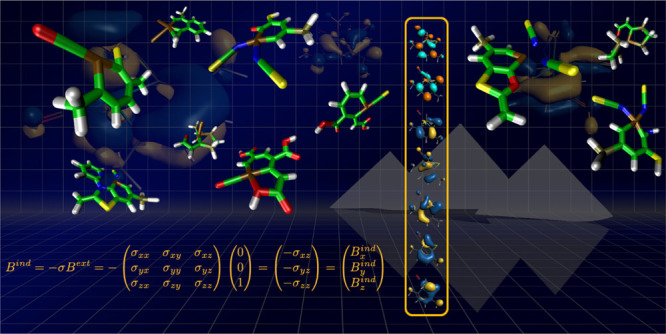

The MICD,46 which is related with aromatic behavior, was calculated using the linear response function56 and the perturbing operator for the magnetic field. The MICD was plotted in the streamline representation of the current density using PyNGL57 and was computed in DIRAC 1758 at the density functional theory level of theory with the B3LYP functional.59−61 The 4-component Dirac-Coloumb Hamiltonian45 has been used alongside the unrestricted kinetic balance. The cc-pVDZ basis set62,63 was employed for all atoms, except for metal atoms. For the latter, the uncontracted and special Dyall double-zeta basis set was employed.64 The integration of the MICD has been done using the 2D Gauss–Lobatto quadrature where the plane was extended from the molecular center to 15 a0 (8 Å) with a step size of 0.1 a0 giving rise to a strength current path, as explained by Sundholm and Gauss.65

The shielding tensors employed for the induced magnetic field (Bind) calculations were computed with the ADF 2014 package using the basis set TZ2P including the scalar relativistic effects and the spin–orbit contribution for the sake of completeness. The Bind was computed with the formula

|

where σ represents the shielding tensor and Bext represents the external magnetic field applied perpendicular to the xy plane and its module is equal to 1 T (|Bext| = 1 T).66 The Bzind (or z-component of the induced magnetic field) is employed as an electronic delocalization criterion.66 This scalar is equivalent to the negative of the zz-component of the shielding tensor, and it is equivalent to NICSzz. This methodology has been employed in different types of molecules including other metallacycles.36,37 In the current work, the metallacycle was placed in the xy plane and the ring’s geometric center was positioned in coincidence with Cartesian coordinates’ origin. Several points were appointed on the perpendicular direction to the molecular plane for the tensor shielding calculations as Morao and Cossio,67 and Jusélius and Sundholm68 proposed in 1999 (see Scheme 1: the black spheres represent the points in the space where the shielding tensors were computed).

Scheme 1. Orientation of the Molecules Studied.

Acknowledgments

R.I. and D.A.O. are grateful for the financial support via the project Fondecyt Regular 1201436. LCGS and ABB acknowledge the CECAD for the Computing Facility and CIDC for the financial support under the project 4-50-598-19.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c00632.

Strength current densities, MICD plots, MO diagrams, and first and second NOCV plots for all the molecules proposed (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

David Arias-Olivares is associated with Universidad Andres Bello (UNAB). Andrés Becerra-Buitrago is associated with Proyecto Curricular Licenciatura en Química, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas.

Supplementary Material

References

- Faraday M. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., London 1825, 115, 440–446. [Google Scholar]

- Thorn D. L.; Hoffmann R. Delocalization in metallocycles. Nouv. J. Chim. 1979, 3, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann R. Building Bridges Between Inorganic and Organic Chemistry (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1982, 21, 711–724. 10.1002/anie.198207113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott G. P.; Roper W. R.; Waters J. M. Metallacyclohexatrienes or ‘metallabenzenes.’ Synthesis of osmabenzene derivatives and X-ray crystal structure of [Os(CSCHCHCHCH)(CO)(PPh3)2]. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1982, 14, 811–813. 10.1039/c39820000811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeke J. R. Metallabenzenes. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1205–1228. 10.1021/cr990337n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X.-Y.; Zhao Q.; Lin Z.; Xia H. The Chemistry of Aromatic Osmacycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 341–354. 10.1021/ar400087x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein J.; Jeffery J. C.; Sherwood P.; Stone F. G. A. Chemistry of polynuclear metal complexes with bridging carbene or carbyne ligands. Part 65. Reactions of the complexes [FeW(μ-CR)(CO)5(η-C5Me5)] and [Fe2W(μ3-CR)(μ-CO)(CO)8(η-C5Me5)](R = C6H4Me-4) with alkynes R′C2R′(R′= Me or Ph); crystal structures of [FeW{μ-C(R)C(O)C(Me)C(Me)}(CO)5(η-C5Me5)]·CH2Cl2 and [FeW{μ-C(R)C(Et)C(H)C(Me)C(Me)}(μ-CO)(CO)3(η-C5Me5)]. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1987, 2211–2218. 10.1039/dt9870002211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kralik M. S.; Rheingold A. L.; Ernst R. D. (Pentadienyl)molybdenum carbonyl chemistry: conversion of a pentadienyl ligand to a coordinated metallabenzene complex. Organometallics 1987, 6, 2612–2614. 10.1021/om00155a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeke J. R. Aromatic Iridacycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1035–1047. 10.1021/ar700071p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeke J. R.; Behm R.; Xie Y.-F.; Chiang M. Y.; Robinson K. D.; Beatty A. M. Synthesis, Structure, Spectroscopy, and Reactivity of a Metallabenzene1. Organometallics 1997, 16, 606–623. 10.1021/om961012p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeke J. R.; Xie Y. F.; Peng W. J.; Chiang M. Metallabenzene: synthesis, structure, and spectroscopy of a 1-irida-3,5-dimethylbenzene complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 4118–4120. 10.1021/ja00193a064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frogley B. J.; Wright L. J. Fused-ring metallabenzenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 270-271, 151–166. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeke J. R.; Blanchard J. M. B. Synthesis and Reactivity of a Metallapyrylium1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 5443–5444. 10.1021/ja970779l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeke J. R.; Blanchard J. M. B.; Donnay E. Synthesis, Spectroscopy, and Reactivity of a Metallapyrylium1. Organometallics 2001, 20, 324–336. 10.1021/om0008068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weller K. J.; Filippov I.; Briggs P. M.; Wigley D. E. Pyridine Degradation Intermediates as Models for Hydrodenitrogenation Catalysis: Preparation and Properties of a Metallapyridine Complex. Organometallics 1998, 17, 322–329. 10.1021/om970749r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. R. W.; Harris S. π Delocalization in iridathiabenzenes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2008, 361, 3012–3016. 10.1016/j.ica.2008.04.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Profilet R. D.; Fanwick P. E.; Rothwell I. P. 1,3-Dimetallabenzene Derivatives of Niobium or Tantalum. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1992, 31, 1261–1263. 10.1002/anie.199212611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riley P. N.; Profilet R. D.; Salberg M. M.; Fanwick P. E.; Rothwell I. P. ‘1,3-dimetallabenzene’ derivatives of niobium and tantalum. Polyhedron 1998, 17, 773–779. 10.1016/s0277-5387(97)00316-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott G. P.; McAuley N. M.; Roper W. R.; Shapley P. A. An Osmium Containing Benzene Analog, Os(CSCHCHCHCH)(CO)(Pph3)2, Carbonyl(5-Thioxo-1, 3-Pentadiene-1, 5-Diyl-C 1, C 5, S)-Bis(Triphenylphosphine)Osmium, and its Precursors. Inorg. Synth. 1989, 26, 184–189. 10.1002/9780470132579.ch33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard C. E. F.; Roper W. R.; Woodgate S. D.; Wright L. J. Reaction between the thiocarbonyl complex, Os(CS)(CO)(PPh3)3, and propyne: crystal structure of a new sulfur-substituted osmabenzene. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 623, 109–115. 10.1016/s0022-328x(00)00717-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Lin R.; Hong G.; Wang T.; Wen T. B.; Xia H. Nucleophilic Aromatic Addition Reactions of the Metallabenzenes and Metallapyridinium: Attacking Aromatic Metallacycles with Bis (diphenylphosphino) methane to Form Metallacyclohexadienes and Cyclic η2-Allene-Coordinated Complexes. Chem.—Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6999–7007. 10.1002/chem.201000324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Zhang H.; Han F.; Long L.; Lin Z.; Xia H. Key Intermediates of Iodine-Mediated Electrophilic Cyclization: Isolation and Characterization in an Osmabenzene System. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9251–9255. 10.1002/anie.201302863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard C. E. F.; Roper W. R.; Woodgate S. D.; Wright L. J. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions of a Metallabenzene: Nitration and Halogenation of the Osmabenzene [Os{C(SMe)CHCHCHCH}I(CO)(PPh3)2]. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 750–752. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Zhang H. Reactions of Metal–Carbon Bonds within Six-Membered Metallaaromatic Rings. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 8962–8973. 10.1002/chem.201705679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung W. Y.; Liu B.; Shou W.; Wen T. B.; Shi C.; Sung H. H.-Y.; Williams I. D.; Lin Z.; Jia G. Electrophilic Substitution Reactions of Metallabenzynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18350–18360. 10.1021/ja207315h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark G. R.; Johns P. M.; Roper W. R.; Wright L. J. An Osmabenzofuran from Reaction between Os(PhC⋮CPh)(CS)(PPh3)2 and Methyl Propiolate and the C-Protonation of this Compound to Form a Tethered Osmabenzene. Organometallics 2006, 25, 1771–1777. 10.1021/om0510371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z.; He G.; Cheng X.; Deng Z.; Chen J. Synthesis and Characterization of Cyclopropaosmanaphthalenes Containing a Fused σ-Aromatic Metallacyclopropene Unit. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 9174–9178. 10.1002/anie.201904815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleyer P. v. R.; Maerker C.; Dransfeld A.; Jiao H.; van Eikema Hommes N. J. R. Nucleus-independent chemical shifts: A simple and efficient aromaticity probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6317–6318. 10.1021/ja960582d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Wannere C. S.; Corminboeuf C.; Puchta R.; Schleyer P. v. R. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS) as an Aromaticity Criterion. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888. 10.1021/cr030088+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleyer P. v. R.; Kiran B.; Simion D. V.; Sorensen T. S. Does Cr(CO)3 Complexation Reduce the Aromaticity of Benzene?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 510–513. 10.1021/ja9921423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Olivares D.; Páez-Hernández D.; Islas R. The role of Cr, Mo and W in the electronic delocalization and the metal–ring interaction in metallocene complexes. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 5334–5344. 10.1039/c8nj00510a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iron M. A.; Lucassen A. C. B.; Cohen H.; van der Boom M. E.; Martin J. M. L. A Computational Foray into the Formation and Reactivity of Metallabenzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11699–11710. 10.1021/ja047125e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright L. J. Metallabenzenes and metallabenzenoids. Dalton Trans. 2006, 101, 1821–1827. 10.1039/b517928a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karton A.; Iron M. A.; van der Boom M. E.; Martin J. M. L. NLO Properties of Metallabenzene-Based Chromophores: A Time-Dependent Density Functional Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 5454–5462. 10.1021/jp0443456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periyasamy G.; Burton N. A.; Hillier I. H.; Thomas J. M. H. Electron Delocalization in the Metallabenzenes: A Computational Analysis of Ring Currents. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 5960–5972. 10.1021/jp7106044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islas R.; Poater J.; Solà M. Analysis of the Aromaticity of Five-Membered Heterometallacycles Containing Os, Ru, Rh, and Ir. Organometallics 2014, 33, 1762–1773. 10.1021/om500119c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez-Espinal A.; Poater J.; Solà M.; Tiznado W.; Islas R. Testing the effectiveness of the isoelectronic substitution principle through the transformation of aromatic osmathiophene derivatives into their inorganic analogues. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 1168–1178. 10.1039/c6nj02972h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birk R.; Grössmann U.; Hund H.-U.; Berke H. Koordination und Chemie von Acetylenen an dicarbonylbis(tirmethlphosphit)eisen-fragmenten. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988, 345, 321–329. 10.1016/0022-328x(88)80096-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung C. F.; Chung L. H.; Ng S. W.; Shek H. L.; Tse S. Y.; Chan S. C.; Tse M. K.; Yiu S. M.; Wong C. Y. Phosphonium-Ring-Fused Bicyclic Metallafuran Complexes of Ruthenium and Osmium. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 9159–9163. 10.1002/chem.201901080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández I.; Frenking G.; Merino G. Aromaticity of metallabenzenes and related compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6452–6463. 10.1039/c5cs00004a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.; Zhu Q.; Rouf A. M.; Zhu J. Probing the Aromaticity and Stability of Metallatricycles by DFT Calculations: Toward Clar Structure in Organometallic Chemistry. Organometallics 2020, 39, 80–86. 10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mauksch M.; Tsogoeva S. B. Strict Correlation of HOMO Topology and Magnetic Aromaticity Indices in d-Block Metalloaromatics. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10059–10063. 10.1002/chem.201802270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine T.; Islas R.; Merino G. σ and π contributions to the induced magnetic field: Indicators for the mobility of electrons in molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 302–309. 10.1002/jcc.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islas R.; Chamorro E.; Robles J.; Heine T.; Santos J. C.; Merino G. Borazine: to be or not to be aromatic. Struct. Chem. 2007, 18, 833–839. 10.1007/s11224-007-9229-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bast R.; Jusélius J.; Saue T. 4-Component relativistic calculation of the magnetically induced current density in the group 15 heteroaromatic compounds. Chem. Phys. 2009, 356, 187–194. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundholm D.; Fliegl H.; Berger R. J. F. Calculations of magnetically induced current densities: theory and applications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2016, 6, 639–678. 10.1002/wcms.1270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- te Velde G.; Bickelhaupt F. M.; Baerends E. J.; Fonseca Guerra C.; van Gisbergen S. J. A.; Snijders J. G.; Ziegler T. Chemistry with ADF. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 931–967. 10.1002/jcc.1056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 194101. 10.1063/1.2370993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J. Optimized Slater-type basis sets for the elements 1–118. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1142–1156. 10.1002/jcc.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn W.; Sham L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133. 10.1103/physrev.140.a1133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Snijders J. G.; Baerends E. J. The zero-order regular approximation for relativistic effects: The effect of spin–orbit coupling in closed shell molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 6505–6516. 10.1063/1.472460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak A.; DeKock R. L.; Ziegler T. Bond Multiplicity in Transition-Metal Complexes: Applications of Two-Electron Valence Indices. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 7256–7263. 10.1021/jp800139g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoraj M. P.; Michalak A.; Ziegler T. A Combined Charge and Energy Decomposition Scheme for Bond Analysis. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2009, 5, 962–975. 10.1021/ct800503d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoraj M. P.; Michalak A.; Ziegler T. On the Nature of the Agostic Bond between Metal Centers and β-Hydrogen Atoms in Alkyl Complexes. An Analysis Based on the Extended Transition State Method and the Natural Orbitals for Chemical Valence Scheme (ETS-NOCV). Organometallics 2009, 28, 3727–3733. 10.1021/om900203m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saue T.; Jensen H. J. A. Linear response at the 4-component relativistic level: Application to the frequency-dependent dipole polarizabilities of the coinage metal dimers. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 522–536. 10.1063/1.1522407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- London F. Théorie quantique des courants interatomiques dans les combinaisons aromatiques. J. Phys. Radium 1937, 8, 397–409. 10.1051/jphysrad:01937008010039700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DIRAC A Relativistic Ab Initio Electronic Structure Program, Release DIRAC17, written by Visscher L.; Jensen H. J. A.; Bast R.; Saue T., with contributions from V. Bakken, K. G. Dyall, S. Dubillard, U. Ekström, E. Eliav, T. Enevoldsen, E. Faßhauer, T. Fleig, O. Fossgaard, A. S. P. Gomes, E. D. Hedegård, T. Helgaker, J. Henriksson, M. Iliaš, Ch. R. Jacob, S. Knecht, S. Komorovský, O. Kullie, J. K. Lærdahl, C. V. Larsen, Y. S. Lee, H. S. Nataraj, M. K. Nayak, P. Norman, G. Olejniczak, J. Olsen, J. M. H. Olsen, Y. C. Park, J. K. Pedersen, M. Pernpointner, R. Di Remigio, K. Ruud, P. Sałek, B. Schimmelpfennig, A. Shee, J. Sikkema, A. J. Thorvaldsen, J. Thyssen, J. van Stralen, S. Villaume, O. Visser, T. Winther, and S. Yamamoto, 2017. (see http://www.diracprogram.org).

- Becke A. D.; Edgecombe K. E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397–5403. 10.1063/1.458517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosko S. H.; Wilk L.; Nusair M. Accurate spin-dependent electron liquid correlation energies for local spin density calculations: a critical analysis. Can. J. Phys. 1980, 58, 1200–1211. 10.1139/p80-159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard B. P.; Altarawy D.; Didier B.; Gibson T. D.; Windus T. L. New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-Date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4814–4820. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. H. Jr Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. 10.1063/1.456153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall K. G.; Gomes A. S. P. Revised relativistic basis sets for the 5d elements Hf–Hg. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2010, 125, 97. 10.1007/s00214-009-0717-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jusélius J.; Sundholm D.; Gauss J. Calculation of current densities using gauge-including atomic orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121, 3952–3963. 10.1063/1.1773136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islas R.; Heine T.; Merino G. The Induced Magnetic Field. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 215–228. 10.1021/ar200117a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morao I.; Cossío F. P. A simple ring current model for describing in-plane aromaticity in pericyclic reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 1868–1874. 10.1021/jo981862+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusélius J.; Sundholm D. Ab initio determination of the induced ring current in aromatic molecules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999, 1, 3429–3435. 10.1039/A903847G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.