Key Points

Question

What is the relative cardiovascular (CV) efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to the baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of 17 160 participants included in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, the effect of dapagliflozin (vs placebo) on the relative risk of a composite of CV death and hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) and of major adverse cardiovascular events was similar. However, the absolute risk reduction of CV death and HHF was significantly larger for dapagliflozin-treated patients who had more markers of chronic kidney disease.

Meaning

In this study, the effect of dapagliflozin on the relative risk for CV events was consistent across kidney function and albuminuria status, with the greatest absolute benefit for the composite of CV death or HHF observed among patients with both reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria.

Abstract

Importance

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, such as dapagliflozin, promote renal glucose excretion and reduce cardiovascular (CV) deaths and hospitalizations for heart failure (HHF) among patients with type 2 diabetes. The relative CV efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to baseline kidney function and albuminuria status are unknown.

Objective

To assess the CV efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This secondary analysis of the randomized clinical trial Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58 compared dapagliflozin vs placebo in 17 160 patients with type 2 diabetes and a baseline creatinine clearance of 60 mL/min or higher. Patients were categorized according to prespecified subgroups of baseline eGFR (<60 vs ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2), urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR; <30 vs ≥30 mg/g), and of chronic kidney disease (CKD) markers using these subgroups (0, 1, or 2). The study was conducted from May 2013 to September 2018.

Interventions

Dapagliflozin vs placebo.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The dual primary end points were major adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV death) and the composite of CV death or HHF.

Results

At baseline, 1265 patients (7.4%) had an eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 5199 patients (30.9%) had albuminuria. Among patients having data for both eGFR and UACR, 10 958 patients (65.1%) had an eGFR equal to or higher than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and an UACR below 30 mg/g (mean [SD] age, 63.7 [6.7] years; 40.1% women), 5336 patients (31.7%) had either an eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria (mean [SD] age, 64.1 [7.1] years; 32.6% women), and 548 patients (3.3%) had both (mean [SD] age, 66.8 [6.9] years; 30.5% women). In the placebo group, patients with more CKD markers had higher event rates at 4 years as assessed using the Kaplan-Meier approach for the composite of CV death or HHF (3.9% for 0 markers, 8.3% for 1 marker, and 17.4% for 2 markers) and major adverse cardiovascular events (7.5% for 0 markers, 11.6% for 1 marker, and 18.9% for 2 markers). Estimates for relative risk reductions for the composite of CV death or HHF and for major adverse cardiovascular events were generally consistent across subgroups (both P > .24 for interaction), although greater absolute risk reductions were observed with more markers of CKD. The absolute risk difference for the composite of CV death or HHF was greater for patients with more markers of CKD (0 markers, −0.5%; 1 marker, −1.0%; and 2 markers, −8.3%; P = .02 for interaction). The numbers of amputations, cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, fractures, and major hypoglycemic events were balanced or numerically lower with dapagliflozin compared with placebo for patients with an eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and an UACR of 30 mg/g or higher.

Conclusions and Relevance

The effect of dapagliflozin on the relative risk for CV events was consistent across eGFR and UACR groups, with the greatest absolute benefit for the composite of CV death or HHF observed among patients with both reduced eGFR and albuminuria.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01730534

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial evaluates the relative safety and efficacy of dapagliflozin vs placebo by assessing risks of a composite of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure and of major adverse cardiovascular events according to baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Kidney dysfunction, including both reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and albuminuria, is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular (CV) outcomes.1,2 Patients with both type 2 diabetes and kidney dysfunction, a frequent comorbidity, therefore represent a particularly vulnerable patient population.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) therapy, which promotes urinary glucose excretion, decreases the risk for CV death and hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) among patients with type 2 diabetes.3 The extent of increased glucosuria, and therefore the glucose-lowering efficacy of an SGLT2i, is attenuated in patients with worse kidney function, as reflected by a lower estimated GFR (eGFR).4 However, a meta-analysis of the 3 SGLT2i CV outcomes trials published to date indicates that the benefit for HHF is greatest among patients with lower baseline kidney function.3 These observations support the hypothesis that glucose control per se is not the driving factor in preventing CV events with SGLT2i therapy and underpin the paradigm shift from a glucocentric focus to broader CV risk mitigation considerations in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes. Although the exact mechanisms of CV benefits are incompletely understood, SGLT2i therapy exerts multiple favorable cardiorenal and metabolic effects, including weight loss, improvement in ventricular loading by reducing preload and afterload, reduction in inflammation and oxidative stress, increased oxygen supply by expansion of red blood cell mass, and lowering of intraglomerular pressure.5,6,7,8,9 In light of the well-known association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the risks of volume overload, mineral and bone disorders, and peripheral artery disease, among others,10,11 the safety profile of dapagliflozin is unknown in this particularly susceptible and thus challenging patient cohort. The present study is a secondary analysis of the Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (DECLARE-TIMI) 58 randomized clinical trial to examine the CV efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to baseline kidney function and albuminuria status.12,13,14 The dual primary end points of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial were the composite of CV death or HHF and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), which are the composite of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and CV death. Dapagliflozin has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of CV death or HHF, caused by a reduction in HHF, and is noninferior with respect to MACE.14

Methods

Study Population

The design and the primary results of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial15 have been previously published (trial protocol in Supplement 1).12,13,14 In brief, the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial randomized 17 160 patients with type 2 diabetes and multiple risk factors for or established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) after a 4 week run-in phase to either dapagliflozin or placebo in addition to standard-of-care medical therapy, enrolling patients from May 2013 to June 2015. Eligible patients with established ASCVD had to be 40 years of age or older and have a history of ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral arterial disease. Patients with multiple risk factors were men 55 years of age or older and women 60 years of age or older who had at least 1 of the following CV risk factors: dyslipidemia, hypertension, or current tobacco use. Patients with a creatinine clearance below 60 mL/min (to convert to milliliters per second per millimeter square, multiply by 0.0167) at screening before entering the run-in period were excluded from the trial. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The trial and this analysis were approved by the institutional review boards of all participating sites. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients in a manner consistent with the Common Rule requirements. No one was offered any incentive for participating in this study.

Outcomes of Interest

The goal of the present analyses was to examine the efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to baseline eGFR and albuminuria status. The composites of CV death or HHF and of MACE were used as the primary efficacy outcomes of interest. Additional outcomes were the individual components of the composite outcomes as well as all-cause death. Safety outcomes of interest included major hypoglycemia, amputation, diabetic ketoacidosis, and fracture. All primary, secondary, and tertiary outcomes were prespecified. The eGFR and albuminuria subgroups were prespecified, but the combined analyses (number of risk factors added together) were not.

Patients were categorized according to their baseline eGFR (<60 vs ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration [CKD-EPI] equation) and baseline urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR; <30 vs ≥30 mg/g) and then categorically ranked by the number of CKD markers (ie, 0, 1, or 2 markers). These strata were selected based on diabetes guidelines, including the recommended initiation of treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for patients with type 2 diabetes and with an eGFR lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, UACR equal or higher than 30 mg/g, or both.16 Patients with an eGFR of at least 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR lower than 30 mg/g were therefore considered to have zero markers of CKD. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using the eGFR and albuminuria risk categories of progression of CKD from the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).17 Further analyses were performed using strata of eGFR (<60, 60 to <90, and ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2) and UACR (<30, 30-300, and >300 mg/g).

Statistical Analysis

The baseline characteristics stratified by markers of kidney dysfunction are reported as mean (SD) values or median values with the interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as counts and proportions for categorical variables. To assess the trend across the levels of kidney dysfunction, we used the Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test for continuous variables and the Cochran-Armitage trend test for categorical variables.

To assess the risk of patients with CKD compared with those without in the placebo group, we adjusted the Cox regression models for age (≥65 vs <65 years), sex, race/ethnicity (White vs non-White), median weight (≥89 vs <89 kg), history of heart failure, dyslipidemia, hypertension, ischemic stroke, peripheral artery disease, duration of diabetes (≤10 vs >10 years), insulin use at baseline, and smoking status. The mean changes in eGFR, blood pressure, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level over time and the differences between dapagliflozin and placebo during the trial were assessed using least-squares mean values and tested for interactions between subgroups at 6 months. Cox regression models with interaction testing were used to test the heterogeneity of the relative treatment effect across the subgroups. All Cox models testing the treatment effects of dapagliflozin vs placebo were stratified according to the presence or absence of known ASCVD and hematuria at baseline and analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach. The proportional hazards assumption was confirmed using statistical tests.18 The P values for heterogeneity are reported for the difference in magnitude of the absolute risk difference across subgroups.19

Data were collected from May 2013 to September 2018. Statistical significance was assessed at a nominal α level of .05. All reported P values are 2-sided with no adjustments for multiple testing. Statistical analyses were carried out using R, version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Study Population

The number of participants randomized and constituting follow-up have been published previously14 and are shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. In the overall population, the mean (SD) eGFR was 85 (16) mL/min/1.73 m2, and the median UACR was 13 mg/g (IQR, 6-44 g/mg). Overall, 1265 patients (7.4%) had an eGFR lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 5199 patients (30.9%) had albuminuria (4029 patients with UACR 30-300 mg/g; 1169 patients with UACR >300 mg/g). Among patients who had both eGFR and UACR readings, 1234 (7.3%) had an eGFR lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 5198 patients (30.9%) had albuminuria (4030 with UACR 30-300 mg/g; 1169 with UACR >300 mg/g) at randomization. Accordingly, 10 958 patients (65.1%) had no markers of higher than stage 2 CKD (mean [SD] age, 63.7 [6.7] years; 40.1% women), whereas 5336 patients (31.7%) (mean [SD] age, 64.1 [7.1] years; 32.6% women) had 1 marker of CKD (either eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [n = 686] or albuminuria with UACR ≥30 mg/g [n = 4650]), and 548 patients (3.3%) had both (mean [SD] age, 66.8 [6.9] years; 30.5% women) (Table 1). These categories are similar to the KDIGO categories of low, mild, and moderate or high risk of CKD progression (eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 2). Patients with more markers of CKD were more likely to be older, male, and have ASCVD and HF, and they were well treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (87.6%) and statins (81.4%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline According to Baseline Kidney Function and Urinary Albumin Status.

| Characteristic | Marker of CKD, No. (%) of participants | P value for trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR <30 mg/g) (n = 10 958) | 1 (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or UACR ≥30 mg/g) (n = 5336) | 2 (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR ≥30 mg/g) (n = 548) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.7 (6.7) | 64.1 (7.1) | 66.8 (6.9) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 4392 (40.1) | 1738 (32.6) | 167 (30.5) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity (Black/African American) | 371 (3.4) | 189 (3.5) | 28 (5.1) | .12 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 31.8 (5.9) | 32.3 (6.1) | 34.8 (6.1) | <.001 |

| HbA1c, mean (SD), % | 8.2 (1.2) | 8.5 (1.3) | 8.4 (1.2) | <.001 |

| LDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 87.8 (34.7) | 87.3 (36.8) | 84.3 (36.7) | .007 |

| Diabetes duration, median (IQR), y | 10.0 (6.0-15.0) | 12.0 (7.0-18.0) | 15.0 (10.0-20.0) | <.001 |

| ASCVD | 4123 (37.6) | 2396 (44.9) | 297 (54.2) | <.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 3367 (30.7) | 1921 (36.0) | 252 (46.0) | <.001 |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 611 (5.6) | 399 (7.5) | 63 (11.5) | <.001 |

| PAD | 508 (4.6) | 423 (7.9) | 62 (11.3) | <.001 |

| Prior HF | 970 (8.9) | 615 (11.5) | 106 (19.3) | <.001 |

| Prior amputation | 30 (0.3) | 62 (1.2) | 11 (2.0) | <.001 |

| Smoker | 1548 (14.1) | 833 (15.6) | 54 (9.9) | .66 |

| Insulin | 3972 (36.2) | 2559 (48.0) | 343 (62.6) | <.001 |

| Metformin | 9121 (83.2) | 4359 (81.7) | 347 (63.3) | <.001 |

| Sulfonylurea | 4782 (43.6) | 2236 (41.9) | 183 (33.4) | <.001 |

| ACE-I or ARB | 8782 (80.1) | 4425 (82.9) | 480 (87.6) | <.001 |

| Any diuretic | 4204 (38.4) | 2291 (42.9) | 342 (62.4) | <.001 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 6526 (59.6) | 3370 (63.2) | 389 (71.0) | <.001 |

| Statin | 8090 (73.8) | 3988 (74.7) | 446 (81.4) | .002 |

| CKD-EPI eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 88.1 (12.7) | 83.0 (17.7) | 50.7 (7.2) | NA |

| UACR, median (IQR), mg/g | 7.9 (4.7-13.8) | 73.6 (38.7-205.8) | 118.9 (58.5-422.3) | NA |

| UACR, mg/g | ||||

| <30 | 10958 (100) | 686 (12.9) | 0 | NA |

| 30-300 | 0 | 3648 (68.4) | 381 (69.5) | NA |

| >300 | 0 | 1002 (18.8) | 167 (30.5) | NA |

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CKD, chronic kidney disease; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HF, heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NA, not applicable; PAD, peripheral artery disease; UACR, urinary albumin to creatinine ratio.

SI conversion factors: To convert the percentage of total hemoglobin to proportion, multiply by 0.01; LDL-C to millimoles per liter, by 0.0259.

CV Outcomes by Markers of CKD in the Placebo Group

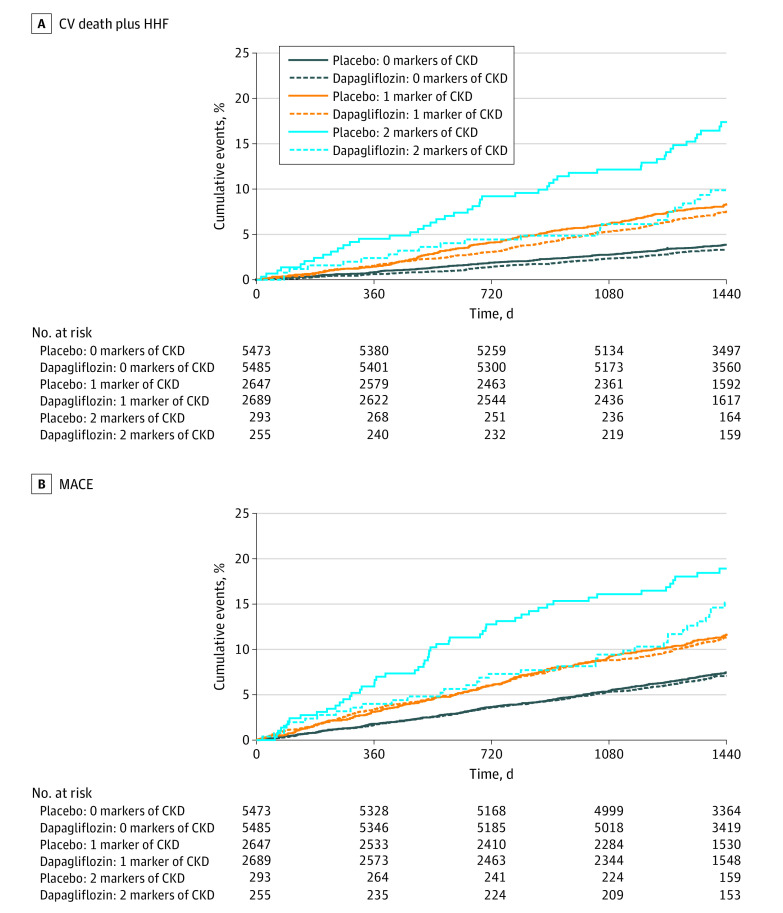

Within the placebo group, patients with more markers of kidney disease had a higher risk for the composite of CV death or HHF (Kaplan-Meier [KM] event incidence at 4 years: 3.9% for 0 markers of CKD, 8.3%, for 1 marker, and 17.4% for 2 markers) (Figure 1A) and MACE (KM event incidence at 4 years: 7.5% for 0 markers of CKD, 11.6% for 1 marker, and 18.9% for 2 markers) (Figure 1B). Patients with only 1 marker of CKD had comparably increased event rates irrespective of whether it was eGFR lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (4-year KM incidence: 7.2% for composite of CV death or HHF, and 12.1% for MACE) or UACR at least 30 mg/g (4-year KM incidence: 8.5% for composite of CV death or HHF, and 11.6% for MACE).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Composite of Cardiovascular (CV) Death and Hospitalization for Heart Failure (HHF) and for Composite of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) Myocardial Infarction, Ischemic Stroke, and CV Death, Stratified by Treatment and Number of Markers of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD).

Solid lines indicate treatment with placebo; dashed lines, treatment with dapagliflozin.

This gradient, with a stepwise increase of risk for patients with more markers of CKD, remained apparent after multivariable adjustment for both the composite of CV death or HHF (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR] with no markers of CKD as reference: AHR, 1.84 [95% CI, 1.52-2.23] for 1 marker; AHR, 2.97 [95% CI, 2.17-4.07] for 2 markers; both P < .001) as well as MACE (AHR, 1.38 [95% CI, 1.19-1.61] for 1 marker; AHR, 2.00 [95% CI, 1.51-2.65] for 2 markers) (both P < .001).

Effects of Dapagliflozin on CV Risk Factors According to Baseline Kidney Function

At 6 months, the extent of HbA1c reduction with dapagliflozin was significantly smaller in patients with lower baseline eGFR compared with patients with more preserved kidney function (least-squares mean absolute difference at 6 months: −0.39 [95% CI, −0.52 to −0.27] for eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2; −0.47 [95% CI, −0.51 to −0. 42] for eGFR 60 to <90 mL/min/1.73 m2; and −0.70 [95% CI, −0.75 to −0.65] for eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; P < .001 for interaction) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). Conversely, the magnitude of effect of dapagliflozin compared with placebo (average least-squares mean absolute difference at 6 months) across baseline kidney function was similar for systolic blood pressure (−3.0 mm Hg for eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; −3.2 mm Hg for eGFR 60 to <90 mL/min/1.73 m2; and −3.6 mm Hg for eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2; P = .20 for interaction), diastolic blood pressure (−1.2 mm Hg for eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; −1.1 mm Hg for eGFR 60 to <90 mL/min/1.73 m2; and −1.6 mm Hg for eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2; P = .53 for interaction), and body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) (−0.6 for eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; −0.6 for eGFR 60 to <90 mL/min/1.73 m2; and −0.5 for eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2; P = .08 for interaction) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo According to Baseline Kidney Function

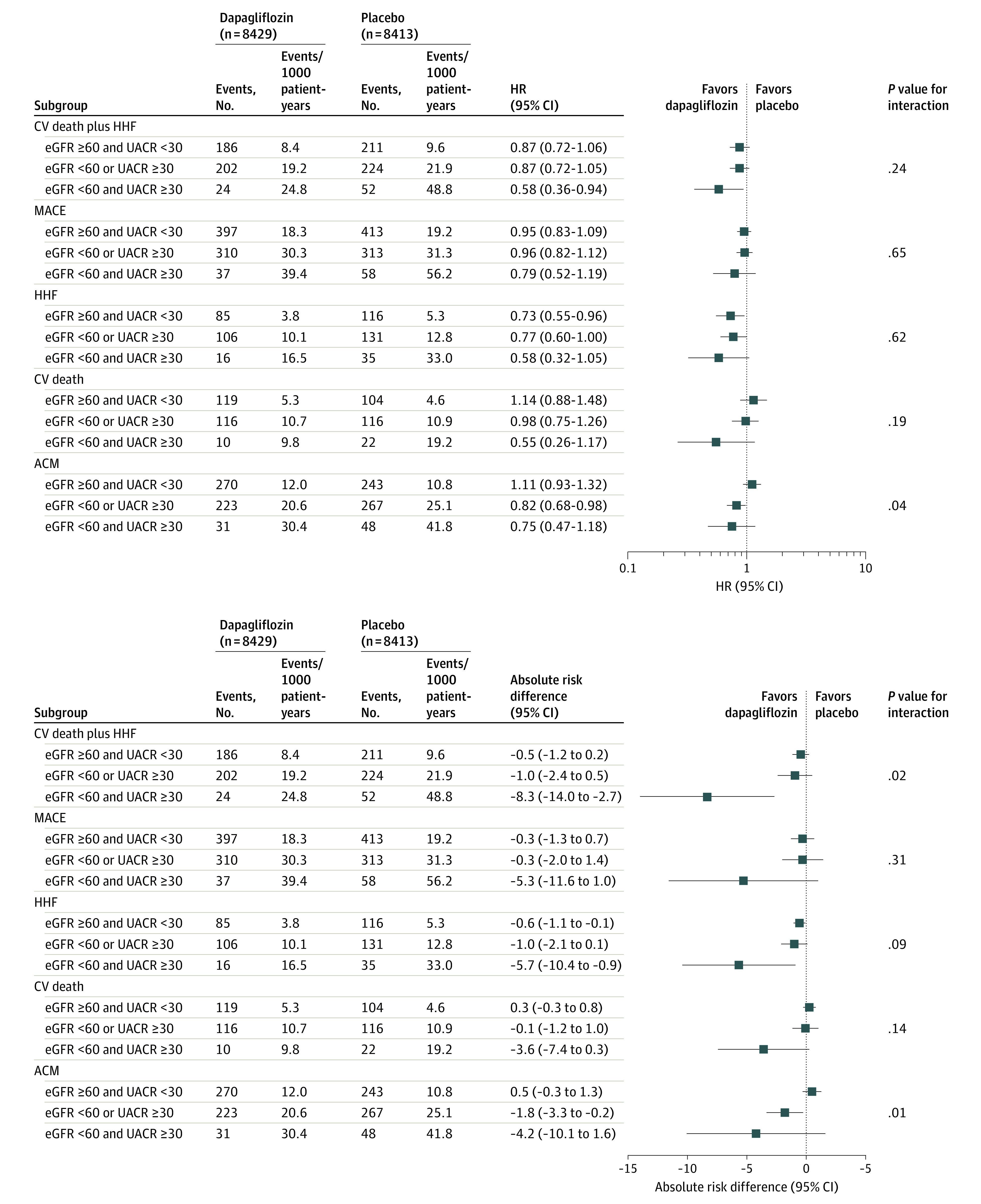

The relative risk reduction for the composite of CV death or HHF for dapagliflozin vs placebo was consistent across the kidney function subgroups (P = .24 for interaction), although numerically greatest (42%) for patients with both reduced eGFR and albuminuria (HR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.72-1.06] for no CKD; HR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.72-1.05] for 1 marker of CKD; HR, 0.58 [95% CI, 0.36-0.94] for 2 markers of CKD) (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Moreover, no effect modification for the magnitude of the relative risk reduction was observed when eGFR (P = .54 for interaction) and log-transformed UACR (P = .24 for interaction) were fit as continuous variables using natural splines with 4 knots. However, given their higher baseline risk, the magnitude of the absolute risk difference was significantly higher for patients with more markers of CKD (−0.5% for 0 markers, −1.0% for 1 marker, and −8.3% for 2 markers; P = .02 for interaction for absolute risk difference). These findings suggest that 13 patients with both eGFR lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR of at least 30 mg/g need to be treated for 4 years to prevent 1 event of the composite of CV death or HHF. An analogous pattern was detected for MACE, with similar relative risk reductions across the subgroups (P = .64 for interaction), but with the absolute risk difference being numerically greatest for patients with more markers of CKD (−0.3% for 0 markers, −0.3% for 1 marker, and −5.3% for 2 markers; P = .31 for interaction for absolute risk difference). For patients with 1 marker of CKD, the results were consistent and qualitatively similar irrespective of whether eGFR was below 60 mL/min or UACR was 30 mg/g or higher (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Relative Effect of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Cardiovascular (CV) Events and Absolute Risk Difference Between Dapagliflozin and Placebo by Number of Markers of Chronic Kidney Disease.

ACM indicates all-cause mortality; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in units of mL/min/1.73 m2); HHF, hospitalization for heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; and UACR, urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (in units of mg/g).

After examination of the individual components of the composite of CV death or HHF, eGFR appeared to have a greater association with the magnitude of risk reduction with dapagliflozin for HHF, whereas UACR appeared to have a greater association with the magnitude of risk reduction with dapagliflozin for CV death (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). Moreover, an interaction (P = .04 for interaction) was observed for effects of dapagliflozin vs placebo on all-cause mortality, indicating a relatively greater treatment benefit for patients with more markers of CKD (HR, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.68-0.98] for 1 marker; HR, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.47-1.18] for 2 markers), whereas no effect was detected for patients with 0 markers (HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.93-1.32]). This effect modification appeared to be caused by UACR (P = .007 for interaction) and not by eGFR (P = .61 for interaction). In particular, patients with a greater UACR tended to derive a greater reduction in all-cause mortality (HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.94-1.30] for UACR <30 mg/g; HR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.62-0.95] for UACR 30-300 mg/g; and HR, 0.73 [95% CI, 0.53-1.01] for UACR >300 mg/g; P = .007 for interaction).

Similar results were found when examining patients categorized according to the KDIGO risk grouping (eFigure 5 in Supplement 2). Moreover, applying the inclusion criteria of the Canagliflozin and Renal Events in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) trial4 (ie, eGFR between 30 and <90 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR >300 mg/g; 718 participants) identified a subgroup that showed a 32% relative risk reduction (HR, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.46-1.00]) for CV death or HHF composite and a 17% relative risk reduction (HR, 0.83 [95% CI, 0.58-1.18]) for MACE. The observed point estimates were thus similar to those observed in the CREDENCE trial (HR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.57-0.83] for CV death or HHF composite; HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.67-0.95] for MACE).4

The safety profile of dapagliflozin was similar across all tested subgroups (Table 2). Most notably, the numbers of amputations, cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, fractures, and major hypoglycemic events were balanced or numerically lower with dapagliflozin compared with placebo in patients with an eGFR lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and an UACR of 30 mg/g or higher.

Table 2. Safety Outcomes of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo by Number of Markers of CKD.

| Event or CKD marker subgroup | Dapagliflozin (n = 8424) | Placebo (n = 8409) | P value | P value for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | Events/1000 patient-years | No. of events | Events/1000 patient-years | |||

| Amputation | ||||||

| eGFR ≥60 and UACR <30 | 54 | 2.4 | 43 | 2.0 | .27 | .53 |

| eGFR <60 or UACR ≥30 | 59 | 5.6 | 62 | 6.0 | .67 | |

| eGFR<60 and UACR ≥30 | 6 | 6.2 | 6 | 5.4 | .79 | |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | ||||||

| eGFR ≥60 and UACR <30 | 21 | 1.1 | 6 | 0.3 | .009 | .36 |

| eGFR <60 or UACR ≥30 | 6 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.6 | .83 | |

| eGFR <60 and UACR ≥30 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | NA | |

| Fracture | ||||||

| eGFR ≥60 and UACR <30 | 274 | 12.7 | 262 | 12.1 | .65 | .98 |

| eGFR <60 or UACR ≥30 | 159 | 15.5 | 153 | 15.1 | .88 | |

| eGFR <60 and UACR ≥30 | 15 | 15.9 | 18 | 16.7 | .98 | |

| Major hypoglycemic event | ||||||

| eGFR ≥60 and UACR <30 | 30 | 1.5 | 36 | 1.9 | .40 | .59 |

| eGFR <60 or UACR ≥30 | 21 | 2.2 | 35 | 3.9 | .04 | |

| eGFR <60 and UACR ≥30 | 4 | 5.0 | 8 | 9.0 | .36 | |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in units of mL/min/1.73 m2); NA, not applicable; UACR, urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (in units of mg/g).

Discussion

The results from the present analyses of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial showed largely consistent relative risk reductions with dapagliflozin in CV events irrespective of baseline eGFR and albuminuria status in a broad population of patients with type 2 diabetes who had or were at risk for ASCVD. However, patients with more markers of CKD derived a significantly greater absolute risk reduction for the composite of CV death or HHF, reflecting a consistent effect in the context of their higher baseline risk, and with a clear disconnect between CV efficacy and measures of glucose control. Consistent with the results in the overall patient population, those favorable effects were not counterbalanced by adverse events because there were no differences in major hypoglycemic events, amputations, or fractures by treatment group in patients with more markers of CKD. Baseline kidney function also did not modify the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Initial concerns about the glucose-lowering efficacy of dapagliflozin in patients with a lower eGFR led to requested modifications of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial protocol by the US Food and Drug Administration to exclude patients with a creatinine clearance below 60 mL/min at screening. The timing (enrollment before entering the run-in period vs randomization) and the use of the CKD-EPI creatinine equation that tends to yield eGFR values lower than the corresponding creatinine clearance estimates may explain why a small proportion of patients with an estimated creatinine clearance below 60 mL/min at enrollment had eGFR levels below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at randomization. Treatment with dapagliflozin is not recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration for glycemic control in patients with an eGFR below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 and is contraindicated for glycemic control in patients with an eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 without established CV disease or CV risk factors. However, these regulations were established because of attenuated urinary glucosuria and thus lower efficacy in HbA1c reductions in those patients and not because of safety concerns. In the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, we observed lower, albeit still significant, reductions in HbA1c levels in patients with a lower baseline eGFR compared with patients who had more preserved baseline kidney function, whereas the magnitude in blood pressure and body mass index reductions were consistent irrespective of baseline kidney function, suggesting that these effects are mediated through nondiuretic mechanisms.

Although no difference was appreciated in secondary analyses of the individual trials by baseline kidney function,20,21 meta-analyses of the 3 completed SGLT2i CV outcomes trials indicated even greater protection from HHF among patients with worse baseline kidney function.3 In addition to the favorable CV outcomes across the different stages of CKD, SGLT2i therapy preserved the effect on risk reduction of kidney events among patients with worse baseline kidney function. The prognostic importance of the cardiorenal interaction and its bidirectional nature has been well established.1,22,23 Both acute and chronic disorders of the heart and kidneys may cause acute or chronic disorders in the other.1,22 However, SGLT2i therapy has multiple favorable effects that may interrupt this vicious circle by decreasing the risk of HHF, preventing deterioration of kidney function, and reducing the progression of albuminuria.24,25,26,27,28 The exact mechanisms of action remain incompletely understood and are subject to current research, but they are believed to include lowering blood pressure, reducing volume overload, changing myocardial energetics, and reducing intraglomerular pressure, inflammation, and oxidant stress.5,9,29

The first dedicated SGLT2i kidney outcomes trial, the CREDENCE trial,4 lends further support for the use of SGLT2i therapy for patients with kidney dysfunction. The CREDENCE trial, which included 4401 patients with diabetes and an eGFR between 30 and <90 mL/min/1.73 m2 and concomitant macroalbuminuria (UACR >300 mg/g to 5000 mg/g), was terminated early for overwhelming efficacy.4 As compared with placebo, canagliflozin reduced the risk of the primary end point, a composite of end-stage kidney disease, doubling of serum creatinine levels, or kidney or CV death, by 30%. In addition, significant reductions for CV outcomes, including the composite of HHF or CV death (31%) and the composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, or CV death (20%), were observed.4,30 As compared with the CREDENCE trial4 (and the 2 other SGLT2i CV outcomes trials31,32), patients in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial had more preserved baseline kidney function. Even though only a small proportion of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 patient population would have met the inclusion criteria of the CREDENCE trial (and thus the CIs are wide), it is noteworthy that the point estimates of CV efficacy from analyses of this small subset in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial yielded relative risk reductions nearly identical to those observed in the CREDENCE trial for the composite of CV death or HHF (32% vs 31%) and for MACE (17% vs 20%).

Kidney outcomes in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, according to baseline kidney function, have been recently reported showing a consistent favorable effect supporting the use of SGLT2i therapy for patients with CKD.33 Dedicated kidney outcome trials studying the role of SGLT2i therapy for patients with or without type 2 diabetes are currently ongoing. Recently, the Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA-CKD) trial showed a significant reduction of kidney events in patients with CKD irrespective of the presence or absence of diabetes.34 Those data with their favorable safety profile across the different subgroups of CKD support the use of dapagliflozin in this patient population and support further investigation of patients with more severe stages of CKD despite the lower glucose-lowering effectiveness of dapagliflozin for this condition.

Limitations

These analyses are subject to the known limitations of subgroup analyses, including their exploratory nature and limited statistical power. In addition, no adjustment for multiple testing was conducted. Furthermore, as aforementioned, owing to the inclusion criteria of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, most of the patients had an eGFR of at least 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, constraining the generalizability of the present results to patients with a lower eGFR.

Conclusions

Patients with more markers of kidney dysfunction had higher rates of adverse CV outcomes. The use of dapagliflozin showed generally consistent relative risk reductions but greater absolute risk reductions for the composite of CV death or HHF for patients with more severe kidney disease (evidenced by both reduced eGFR and albuminuria), reflecting their increased baseline risk.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) and Urinary Albumin to Creatinine Ratio (UACR) Values in DECLARE-TIMI 58

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics According to KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) Grouping

eFigure 1. Consort Diagram

eFigure 2. Change in Cardiovascular Risk Factors According to Baseline Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) Over Time

eFigure 3. Relative Effect and Absolute Risk Difference of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Cardiovascular Events by the Individual Markers of Chronic Kidney Disease

eFigure 4. Effect of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Cardiovascular Events (A) by eGFR and (B) by UACR Categories

eFigure 5. Relative Effect and Absolute Risk Difference of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Cardiovascular Events According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Risk Classification

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, Blair JEA, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and Council on Clinical Cardiology . Cardiorenal syndrome: classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment strategies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(16):e840-e878. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scirica BM, Mosenzon O, Bhatt DL, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes according to urinary albumin and kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk: observations from the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(2):155-163. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):31-39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32590-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. ; CREDENCE Trial Investigators . Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zelniker TA, Braunwald E. Cardiac and renal effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in diabetes: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(15):1845-1855. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidokoro K, Cherney DZI, Bozovic A, et al. Evaluation of glomerular hemodynamic function by empagliflozin in diabetic mice using in vivo imaging. Circulation. 2019;140(4):303-315. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazer CD, Hare GMT, Connelly PW, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on erythropoietin levels, iron stores, and red blood cell morphology in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2020;141(8):704-707. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zelniker TA, Braunwald E. Clinical benefit of cardiorenal effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(4):435-447. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zelniker TA, Braunwald E. Mechanisms of cardiorenal effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(4):422-434. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moen MF, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1121-1127. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00800209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1238-1252. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32064-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. The design and rationale for the Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events (DECLARE)-TIMI 58 Trial. Am Heart J. 2018;200:83-89. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raz I, Mosenzon O, Bonaca MP, et al. DECLARE-TIMI 58: participants’ baseline characteristics. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(5):1102-1110. doi: 10.1111/dom.13217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. ; DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators . Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):347-357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dapagliflozin effect on cardiovascular events: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the effect of dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily on the incidence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke in patients with type 2 diabetes (DECLARE-TIMI 58). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01730534. Updated December 26, 2019. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01730534?cond=NCT01730534&draw=2&rank=1

- 16.American Diabetes Association . 11. Microvascular complications and foot care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S135-S151. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapter 1: Definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2013;3(1):19-62. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515-526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gail M, Simon R. Testing for qualitative interactions between treatment effects and patient subsets. Biometrics. 1985;41(2):361-372. doi: 10.2307/2530862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neuen BL, Ohkuma T, Neal B, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with canagliflozin according to baseline kidney function: data from the CANVAS Program. Circulation. 2018;138(15):1537-1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanner C, Lachin JM, Inzucchi SE, et al. ; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators . Empagliflozin and clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, established cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2018;137(2):119-129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, Anavekar N, Bellomo R. Cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(19):1527-1539. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronco C, McCullough P, Anker SD, et al. ; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) consensus group . Cardio-renal syndromes: report from the consensus conference of the acute dialysis quality initiative. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(6):703-711. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al. ; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators . Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):323-334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: results from the CANVAS Program randomised clinical trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(9):691-704. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30141-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. Comparison of the effects of glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for prevention of major adverse cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2019;139(17):2022-2031. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2019;139(22):2528-2536. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braunwald E. Diabetes, heart failure, and renal dysfunction: the vicious circles. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;62(4):298-302. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heerspink HJ, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, Husain M, Cherney DZ. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms, and clinical applications. Circulation. 2016;134(10):752-772. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahaffey KW, Jardine MJ, Bompoint S, et al; CREDENCE Study Investigators. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention groups: results from the randomized CREDENCE Trial. Circulation. 2019;140(9):739-750. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. ; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators . Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. ; CANVAS Program Collaborative Group . Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):644-657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, Cahn A, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on development and progression of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(8):606-617. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30180-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436-1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) and Urinary Albumin to Creatinine Ratio (UACR) Values in DECLARE-TIMI 58

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics According to KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) Grouping

eFigure 1. Consort Diagram

eFigure 2. Change in Cardiovascular Risk Factors According to Baseline Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) Over Time

eFigure 3. Relative Effect and Absolute Risk Difference of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Cardiovascular Events by the Individual Markers of Chronic Kidney Disease

eFigure 4. Effect of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Cardiovascular Events (A) by eGFR and (B) by UACR Categories

eFigure 5. Relative Effect and Absolute Risk Difference of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Cardiovascular Events According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Risk Classification

Data Sharing Statement