Abstract

In view of the current situation of high cost and low catalytic efficiency of the commercial Pd-based catalysts, adding transition metals (Ni, Co, etc.) to form the Pd-M bimetallic catalyst not only reduces the consumption of Pd but also greatly improves the catalytic activity and stability, which has attracted increasing attention. In this work, the three-dimensional network Pd–Ni bimetallic catalysts were prepared successfully by a liquid-phase in situ reduction method with the hydroxylated γ-Al2O3 as the support. Through investigating the effects of the precursor salt amount, reducing agent concentration, stabilizer concentration, and reducing stirring time on the synthesis of the Pd–Ni nanocatalyst, the three-dimensional network Pd–Ni bimetallic nanostructures with four different atomic ratios were prepared under an optimal condition. The obtained wire-like Pd–Ni catalysts have a uniform diameter size of about 5 nm and length up to several microns. After closely combining with the hydroxylated γ-Al2O3, the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts exhibit nearly 100% conversion rate and selectivity for the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline at low temperature and normal pressure. The stability testing of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts shows that the conversion rate still remained above 99% after 10 cycles. There is no doubt that the supported catalysts show significant catalytic efficiency and recyclability, which provides important theoretical basis and technical support for the preparation of low-cost, highly efficient catalysts for the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline.

1. Introduction

Aniline (AN) is an important chemical intermediate, which is widely used in the fields of dyes, pigments, pesticides, medicines, and other chemical industries. At present, AN is mainly obtained by reduction of nitrobenzene (NB) with alkali sulfide reduction, iron powder reduction, catalytic hydrogenation reduction, electrochemical reduction, or CO/H2O reduction.1−5 The catalytic hydrogenation reduction method has attracted extensive attention due to its advantages such as the low reductive cost, high product quality, and green synthetic process.6,7 However, high pressure and high temperature are usually required in the current catalytic hydrogenation reduction process. Therefore, it is of great significance to develop a new type of catalyst to react at normal pressure and low temperature for the improvement of industrial efficiency and environmental protection. The noble metal palladium (Pd) catalyst has been widely used in the field of hydrogenation NB because of its excellent catalytic activity, good electrical conductivity, high-temperature oxidation resistance, and corrosion resistance.8−11 However, its rare resources, high price, low utilization rate, and poor stability are still big obstacles for further application of Pd. Therefore, it is currently urgent to develop high-efficiency catalysts with low cost and superior catalytic performance.

The catalytic activity and stability of the noble metal Pd depend on the size, morphology, and dispersion state of the catalysts. In order to stimulate the maximum catalytic potential of the catalyst, the following methods are usually adopted: (1) preparation of catalysts with specific morphology for increasing the specific surface area and exposing more active sites of the catalysts; (2) loading the catalysts on the support to improve its stability, avoid the agglomeration, and extend the service life of the catalysts;12−15 and (3) adding the transition metal M (Ni, Co, Fe, Cu, Ag, etc.) to form the bimetal or multiple metal catalysts with Pd, thus reducing the consumption of noble metals, and some synergies will be achieved among the different metals that will substantially benefit the efficiency of the noble catalyst.16−19 At present, most of the catalysts used for hydrogenation of NB to AN are supported catalysts, and the impregnation and precipitation are the commonly used methods. Mark et al.20 used Al2O3 as a carrier to synthesize supported mono-(Pd or Ni) and bimetallic (Pd/Ni = 1:3, 1:1, and 3:1) catalysts by an equal volume impregnation method. Pd and Ni mainly exist in the particle state of 15–30 nm in the catalysts. Compared with the monometallic catalysts, the bimetallic catalysts delivered higher yield when used in the selective hydrogenation of p-chloronitrobenzene (p-CNB) to p-chloroaniline (p-CAN). Feng et al.21 prepared a series of Pd/FeOx catalysts with an average Pd particle size of 2.2 nm using a coprecipitation method by controlling the washing operation after coprecipitation of the catalyst precursors. The catalysts were tested by the hydrogenation reactions of NB, benzaldehyde, and styrene, and the yield was greater than 99% under certain conditions.

Although various Pd-based catalysts have been prepared and proved successfully in improving the hydrogenation performance, there are still some problems to be solved for accelerating the practical application of the hydrogenation of NB to AN.22,23 First, the process of preparation was relatively complex, many factors need to be considered, and most would generate a large amount of waste water. Second, the synthesized catalysts mainly existed in the particle state, but the particle size was usually not well controlled. It was easy to agglomerate and deactivate in the reaction process, so the stability of the catalyst could not be guaranteed. Therefore, it is necessary to find new catalysts with controllable size, good stability, and high catalytic performance under the conditions of a simple preparation process and low cost.

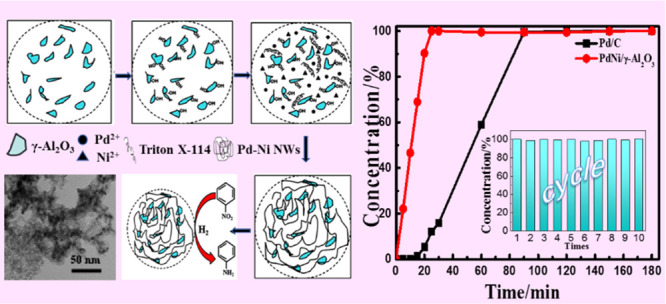

In this work, the supported Pd-based bimetallic catalysts with a low productive cost and high hydrogenation catalytic performance were prepared by the in situ liquid-phase reduction method. Using Triton X-114 as the stabilizer and structure control agent, the three-dimensional network structured catalysts with uniform size and good dispersion were obtained. Compared with the particle catalysts prepared by the traditional method, the supported three-dimensional network catalysts exhibit a long and smooth adsorption surface, large force and strong stability with the support, and thus exhibit excellent catalytic activity in NB hydrogenation reaction under mild conditions. Meanwhile, by introducing Ni to replace part of Pd, the consumption of Pd and the production cost were reduced, and the hydrogenation performance of the catalyst was improved by utilizing the synergistic effect among multimetals. The selectivity of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst to AN was also enhanced. The conversion rate reached 100% when reacting at 25 min, and the turnover frequency (TOF) was 7.2 times higher than that of the commercial Pd/C. The stability testing result showed that the conversion rate of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst still remained above 99% after 10 cycles. All these excellent characteristics contributed from the three-dimensional network structure formed by the bimetal (Pd and Ni) catalysts. This work provides an effective strategy for the synthesis of supported catalysts with controllable morphology and high catalytic activity.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Material Characterization

The in situ liquid-phase reduction method was utilized to obtain the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts under mild conditions. Scheme 1 shows the preparation and hydrogenation process of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts. First, the amorphous commercial γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles were dispersed in the deionized water. When the solution was stirred and heated to a certain temperature, NH3·H2O was added and stirred for a certain time, and then, the hydroxylated γ-Al2O3 was obtained. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used to demonstrate the effect of the NH3·H2O treatment on the surface of the γ-Al2O3. As shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information), the broad absorbance band that peaked at 3310 cm–1 represents the stretching mode of surface −OH groups on the particles, indicating that the hydroxyl groups were successfully introduced onto the surface of γ-Al2O3 by NH3·H2O treatment.24 Second, the modified γ-Al2O3 was added into the metal salt solution with Triton X-114 as the stabilizer and stirred for a certain time, so that metal cations were adsorbed on the surface of the support. The electrostatic adsorption mechanism was used in the preparation of the catalysts to allow the metal ions to be adsorbed on the surface of the support, and then, the catalyst was loaded onto the support in one step by means of in situ reduction. Finally, through reducing the mixed solution with NaBH4, the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts with a three-dimensional network structure could be obtained. Undoubtedly, the linear network structure has the advantages of long segment smoothness, stable structure, being self-supporting, and so forth. Compared with the particles, the Pd–Ni bimetallic catalysts with a linear structure have greater force with the γ-Al2O3 support, thus leading to strong stability, which is favorable for improving the hydrogenation performance and stability of the catalyst. The preparation process is simple, and the conditions are mild. To find out the optimal synthesis conditions, the influencing factors including the precursor salt amount, reducing agent concentration, stabilizer concentration, and reducing stirring time were explored. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of samples obtained under different conditions are shown in Figures S2–S5. Results show that when the precursor salt amount is 0.6 mmol, the mass fraction of the stabilizer Triton X-114 is 0.5%, the concentration of the reducing agent NaBH4 is 2 mg/mL, and the reducing stirring time is 1 min, the obtained Pd–Ni nanocatalysts exhibit a well-controllable linear network structure, uniform size, and good dispersion.

Scheme 1. Preparation and Hydrogenation Process of the Supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts.

The morphology, composition, and microstructure features of samples were investigated by TEM analysis. Figure 1 shows TEM, high resolution TEM (HRTEM), selected area electron diffraction (SAED), and energy-dispersive spectrometry (EDS) images of the Pd–Ni catalysts with different atomic ratios. When the molar ratio of Pd(NO3)2 to Ni(NO3)2 is 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1, the obtained samples exhibit a nanowire structure with a uniform diameter of around 4–6 nm (Figure 1a–c). These nanowires intertwine with each other and form a three-dimensional network. When the molar ratio of Pd(NO3)2 to Ni(NO3)2 decreases to 1:2, the sheet structure instead of nanowires could be found in Figure 1d.

Figure 1.

TEM images of Pd–Ni catalysts with different atomic ratios of Pd/Ni. (a) Pd/Ni = 3:1; (b) Pd/Ni = 2:1; (c) Pd/Ni = 1:1; (d) Pd/Ni = 1:2; (e) HRTEM image, (f) SAED pattern, and (g) EDS spectrum of Pd–Ni catalysts; TEM images of the (h) γ-Al2O3 support and (i) Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts.

HRTEM image (Figure 1e) shows the clear lattice fringe of the Pd–Ni bimetallic catalysts with an atomic ratio of 1:1, and the spacing distance is about 0.231 nm, which is between Pd(111) and Ni(111) crystal plane spacing, indicating the formation of the Pd–Ni alloy. The SAED diagram (Figure 1f) taken from the nanowire in Figure 1c clearly shows the diffraction rings. From the inside to the outside, they correspond to the (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) crystal planes, indicating that the Pd–Ni bimetal catalysts exist in the polycrystalline state. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectra further prove that the product is composed of Pd and Ni elements, and the atomic ratio is close to 1:1, of which C and Cu mainly come from the copper net and carbon film.

The morphological features of the γ-Al2O3 support and the obtained Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts were investigated by transmission electron microscope analysis, as shown in Figure 1h,i. The γ-Al2O3 support (Figure 1h) exhibits sheet-like morphology and almost uniform size of about 20 nm, which could play a good supporting role. Figure 1i shows the morphology of the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst, in which the nanowires are intertwined on the γ-Al2O3 support and closely combined with the support to form the supported three-dimensional network catalyst.

The phase composition and crystal structure of the samples were tested with X-ray diffraction (XRD). Figure 2a,b shows the representative XRD patterns of the Pd–Ni nanocatalysts and Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts with different Pd/Ni atomic ratios. The obvious diffraction peaks of the nickel or nickel oxide are not observed in the XRD spectrum in Figure 2a, indicating that the Ni atoms enter into the crystal structure of Pd, and some Pd atoms are replaced by Ni atoms, thus making the interplanar spacing of Pd become narrowed.25 The position of the diffraction peak shifts to a high angle with respect to the standard peak position of the Pd (standard card PDF#46-1046). The larger the Ni ratio, the shift of the Pd(111) diffraction peak is more obvious, indicating that the Pd–Ni three-dimensional network nanostructures exist mainly as bimetal solid solutions. Figure 2b shows that the γ-Al2O3 support has no effect on the phase change of the catalysts. Compared with the standard Pd, it also could be found that the diffraction peaks shift to higher angles at 40.1, 46.6, 68.1, and 82.1°, indicating that the active component part of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts exist as solid solution. In addition, the presence of Pd and Ni oxide characteristic peaks can be seen from the XRD image. The possible reason is that the Pd and Ni elements mainly exist at the 0-valent state in the center, while existing mainly in the form of oxides on the surface, which might be oxidized to oxide when exposed to oxygen and moisture in air.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of (a) Pd–Ni nanocatalysts and (b) Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 with different Pd/Ni atomic ratios; high-resolution XPS spectra of (c) Pd 3d and (d) Ni 2p of the synthesized Pd–Ni bimetallic nanocatalysts; N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms curves of the (e) γ-Al2O3 support and (f) Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst (inset: pore-size distribution curves).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was tested to explore the valence state of each element in the three-dimensional network Pd–Ni bimetallic catalyst. The presence of Pd 3d and Ni 2p peaks confirms the coexistence of Pd and Ni in the bimetallic catalysts. The Pd 3d XPS spectrum presents two important forms of Pd species (Figure 2c), namely, Pd(0) and Pd(II). The binding energy of the Pd 3d5/2 level at 335.8 eV and the Pd 3d3/2 level at 340.9 eV could be ascribed to Pd(0), while the binding energy of the Pd 3d5/2 level at 336.2 eV and the Pd 3d3/2 level at 341.4 eV could be ascribed to Pd(II).26−28 By comparing the intensities of the peaks of Pd(0) and Pd(II), it is found that Pd(0) is the predominant form in the Pd–Ni nanocatalyst. The Ni 2p XPS spectra (Figure 2d) show that the peaks at the bond energies of 854.5 and 872.1 eV are stronger, which are assigned to Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2, respectively. It is proved that the Ni element mainly exists in the metallic and metal oxide state.29 Owing to the fact that the addition of the Ni element could change the electronic structure of Pd, the Pd 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 peaks of the bimetallic catalyst are both moving toward the higher binding energy compared with that of the monometallic Pd/Al2O3 catalyst.30,31 The positive shift is associated with the upshift d-band center of Pd and indicates a change in the electronic structure of Pd, possibly due to the electron energy relaxation of Pd levels caused by the presence of Ni atoms in Pd. As a result, it is assumed that there is a close contact between Pd and Ni and the Pd–Ni bimetal exists mainly as the solid solution. This observation is consistent with the literature report.32

The specific surface area and pore size distribution of the samples were investigated by N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm curve analysis. Figure 2e,f shows the nitrogen isothermal desorption and pore size distribution curves of the γ-Al2O3 support and the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts, respectively. For the γ-Al2O3 support, the adsorption–desorption curve has a smaller slope at the beginning and a clear platform in the low-pressure area. With the increase in pressure, the curve rises rapidly, and the specific surface area is calculated to be about 148.8 m2/g. The adsorption–desorption curve of the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst in Figure 2f has the same trend as the curve of the γ-Al2O3 support, and the specific surface area is calculated to be 214.4 m2/g. There is an obvious peak at 11.5 nm in the pore size distribution curve, which indicates that the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst has a porous structure. The presence of the active component significantly increases the specific surface area of the catalyst, thus leading to more active sites, which is beneficial to improve the hydrogenation performance.

2.2. Catalytic Performance

The catalytic activity of the samples for NB hydrogenation to AN under atmospheric pressure was investigated, and the optimum conditions for hydrogenation were explored by adjusting the experimental conditions. As analyzed above, the supported Pd–Ni bimetallic nanocatalysts have a larger specific surface area; meanwhile, the addition of Ni metal would change the electronic structure and metal configuration of Pd metal, which is beneficial to increase the active sites exposed by Pd. The proper atomic ratios of Pd–Ni will help give full play to the bimetallic synergistic effect, which is helpful to show a better catalytic effect. Figure 3a and 3b shows the effect of four different atomic ratios (3:1, 2:1, 1:1, and 1:2) of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts on the hydrogenation performance of NB. With the increase in the content of Ni metal, the reaction rate shows a trend from slow to fast and then slow, in Figure 3a. When the molar ratio of palladium nitrate and nickel nitrate is 1:1, the hydrogenation rate of NB is the fastest. The NB can be completely converted at 25 min, and the selectivity of the AN is close to 100%, as shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

Variation of concentration over time under different conditions. (a) NB with different atomic ratios of the Pd/Ni catalysts; (b) AN with different atomic ratios of the Pd/Ni catalysts; (c) NB at different temperatures; (d) AN at different temperatures; (e) NB in different solvents; (f) AN in different solvents.

The reaction temperature has an important influence on the hydrogenation reaction rate of NB. To a certain extent, increasing the temperature can effectively enhance the diffusion of the reactant molecule, which could improve the reaction speed.33 However, a large amount of AN molecules generated instantaneously cannot effectively detach from the surface of the catalyst. Therefore, the catalysts will be fully occupied and no active site is available, thus leading to the decrease in the reaction rate.34Figure 3c,d shows the effect of the different temperatures on the conversion of the NB to AN. It can be seen that the NB conversion rate reaches the fastest when the temperature is 40 °C, and the conversion rate of NB changes from fast to slow with the increase in temperature (Figure 3c). Also, the change in the conversion rate is consistent with the trend of the concentration, as shown in Figure 3d. The calculated amount of NB is equal to the amount of AN generated, and the conversion rate of AN is 100%. It shows that the optimum reaction temperature is 40 °C.

The reaction of NB hydrogenation involves three phases of gas, liquid, and solid, so the diffusion rate of the reagent and product can be increased by choosing the suitable solvent, which is helpful for the improvement of the reaction rate.35,36 There is a certain requirement for the selection of the solvent. On the one hand, the solubility of the solvent to the reactant and the product should be great, so that the reactant molecules can be fully exposed to the catalyst and the AN molecule can diffuse in time. On the other hand, the solvent should not be chemically reacted under the experimental conditions, and the catalyst is insoluble in the reaction solvent and is easily separated. Figure 3e,f shows the effect of the different solvents on the conversion of the NB and AN. Due to the high yield of AN under neutral conditions, the effect of methanol, ethanol, and n-hexane on the hydrogenation performance of NB was investigated. It can be concluded that when n-hexane is used as the solvent, the conversion of NB can reach 100% for 25 min, indicating that n-hexane as the solvent is more conducive to the diffusion of the reactants and the separation of the AN. The choice of neutral solvents makes the selectivity of the AN reach 100%.

In order to further explore the NB hydrogenation rate of the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst (precursor salt mole ratio 1:1), the catalytic hydrogenation performance was tested at 40 °C, and the reaction solvent was n-hexane. For comparison, the commercial Pd/C catalyst was also studied. Meanwhile, the monometallic Ni nanoparticles prepared by NaBH4 reduction of the nickel precursor were used for the hydrogenation of NB under the same conditions as the present Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 bimetallic catalyst for comparison. However, the Ni nanoparticles were proved to have no activity at all even though five times the amount of Ni was used. Similar situations were also observed for Raney Ni, a typical Ni catalyst. Figure 4 shows the curve of the conversion of NB and AN over time. The conversion rate could reach 100% at 25 min for the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst, while the Pd/C catalyst needs a longer time of 90 min for complete conversion. The TOF is calculated on the basis of the conversion rates of NB (in mol min–1, determined according to the measured NB conversion) and the amount of catalyst. The TOF of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst is 940.4 h–1, which is almost 8.3 times higher than that of the commercial Pd/C catalyst (130.6 h–1). Figure 4b shows that the reduction amount of NB is equal to the amount of AN produced. The selectivity of AN is calculated to be 100%, and there is no change after the AN production rate reaches 100%, indicating that no other byproducts are generated.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the catalytic hydrogenation performance. Concentration of (a) NB and (b) AN over time.

In order to investigate the service life of the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst, the stability test was carried out. The Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst (precursor salt mole ratio 1:1) with the highest catalytic activity was selected as the test object. The reaction temperature was 40 °C, and n-hexane was used as the reaction solvent for the hydrogenation of NB. Samples were taken for every continuous reaction of 25 min for testing. As can be seen from Figure 5a, the catalytic activity still remains above 99% and even the supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst is recycled 10 times. In order to observe the morphology change in the catalyst, TEM investigation was carried out for the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst after 10 cycles (Figure 5b). Compared with the catalyst before the hydrogenation process shown in Figure 1i, the size of the supported Pd–Ni catalysts has no significant change, and there is almost no agglomeration appearing after 10 cycles. All these confirm an excellent stability for the synthesized three-dimensional network Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts.

Figure 5.

(a) Stability test chart of the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst and (b) TEM image of Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 after 10 cycles.

To better understand the performance of the synthesized three-dimensional network Pd–Ni/Al2O3 catalyst, we compared the synthesis methods, hydrogenation reaction conditions, and catalytic performance with some previously reported Pd-based catalysts.37−43 As presented in Table 1, the synthesis method in our work is simple,44−49 and the Pd–Ni/Al2O3 catalysts exhibit high hydrogenation catalytic performance under relatively mild reaction conditions, which reaches nearly 100% conversion rate for the hydrogenation of NB to AN at a low temperature of 40 °C and normal pressure, demonstrating important applications in catalyst design.50−55

Table 1. Comparison of the Synthesis Method and Hydrogenation Catalytic Performance of the Synthesized Pd–Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts with Previous Reports.

| |

reaction conditions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | synthesis methods | P H2 (MPa) | T (°C) | catalytic performance conversion (%) | refs | |

| Pd–6Ni–N–C60 | 1.0 | 70 | 98.0 | (37) | ||

| Pd/LDH(Mg, Al) | ion-exchange method | 1.0 | 50 | close to 100 | (38) | |

| Pd3Au0.5/SiC | reduction of Pd(NO3)2 and HAuCl4 in SiC suspension in succession. | in ambient H2 flow | 25 | 100 | (39) | |

| under Xe-lamp irradiation (400–800 nm, 0.8 W/cm2) | ||||||

| UiO-66-NH2@COP@(2.34%)Pd | reverse double-solvent approach | 0.1 | 25 | 99.9 | (40) | |

| Pd/MIL-101 | colloidal deposition method | 0.6 | 120 | 100 | (41) | |

| Pd@mSiO2 | Pd@m14SiO2 | facile one-pot method | 2.0 | 110 | 97.57 | (42) |

| Pd@m16SiO2 | 98.97 | |||||

| Pd@m18SiO2 | 99.01 | |||||

| hierarchical Pd@Ni | combining the hydrothermal synthesis method with spontaneously galvanic replacement reaction | 0.1 | 25 | 93 | (43) | |

| Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 | a liquid phase in situ reduction method | in ambient H2 flow | 40 | nearly 100 | this work | |

3. Conclusions

In summary, the in situ liquid-phase reduction method was utilized to obtain the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts under mild conditions. The metal ions were adsorbed on the surface of the support by the electrostatic adsorption mechanism and then loaded onto the support in one step by means of in situ reduction. The linear structure for the synthesized Pd–Ni catalysts has unique advantages, such as long segment smoothness, stable structure, being self-supporting, and the great force between the Pd–Ni catalysts with the γ-Al2O3 support. Meanwhile, the addition of Ni element can not only reduce the cost of the catalysts but also improve the catalytic efficiency through the synergistic effect of multimetals. All these features contribute to improve the hydrogenation performance and stability of the catalyst. The conversion of NB to AN is much higher than that of the commercial Pd/C catalyst, and it also exhibits great selectivity and stability. Based on the liquid-phase in situ reduction method, the prepared supported catalysts have a controllable morphology and achieve high catalytic efficiency under low-cost conditions, which provides a potential research direction for the controllable synthesis of efficient catalysts for hydrogenation of NB to AN.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Synthesis of the Hydroxylated γ-Al2O3 Support

γ-Al2O3 (1.7 g) and ammonia (1.7 mL) were dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water in the three-necked flask and sonicated for 30 min, and then, the solution was stirred at 90 °C for 2 h. By cooling down to room temperature after completion of the reaction, the white powders were filtered out and washed with distilled water three times. At last, the modified γ-Al2O3 support was successfully prepared.

4.2. Synthesis of Supported Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts

Aqueous solution of Triton X-114 with a mass concentration of 0.5% was prepared by ultrasonic dispersion. Metal salts of 0.6 mmol were placed in a beaker with nickel nitrate (Ni(NO3)2) and palladium nitrate (Pd(NO3)2) of different molar ratios (2:1, 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3). Triton X-114 solution (50 mL) was added to each beaker and dispersed evenly with ultrasound. The prepared modified γ-Al2O3 was added to the abovementioned beaker and stirred magnetically for 30 min at room temperature for mixing uniformly with the solution. The fresh NaBH4 aqueous solution was quickly poured into the metal solution, with stirring for 1 min. The mixed solution was then set for 10 min, washed by centrifugation with ethanol and water five to six times, and dried at 70 °C; finally, the supported Pd–Ni bimetallic catalysts could be obtained.

4.3. Material Characterization

The crystal phase of the catalysts was analyzed with the Philips X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation in the 2θ range from 35 to 90°. TEM and HRTEM images were taken from the FEI Tecnai F30 transmission electron microscope with a field emission gun operating at 200 kV for examining the size and microstructure of the samples. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area and the adsorption/desorption isotherms of the samples after thermal treatment and H2 reduction were determined via N2 adsorption at 77 K, using the Micrometrics ASAP-2020 M automatic specific surface area and porous physical adsorption analyzer. The electronic structure of samples was investigated by a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi XPS instrument using Mg Kα as the exciting source (1253.6 eV).

4.4. Hydrogenation of NB

The hydrogenation performance of NB was tested in a three-necked flask. First, the mixed solution was prepared with 1:999 volume ratio of NB and the solvent and ultrasonicated to make the dispersion even. Second, 0.0798 g of the Pd–Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts (mass percentage of Pd-M is 1%) was added to the mixed solution (15 mL) and transferred to the 100 mL three-necked flask. The gas was replaced by H2 to remove the air in the reaction apparatus four to five times and then heated up to a certain temperature. It was required to record the start and sample on time. Finally, 30 μL of the supernatant was pipetted with a micropipette and diluted with the solvent to 500 μL in a small sample vial for being tested.

The reaction products were qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed using the gas chromatograph of the Aligent 7890A with high purity nitrogen as carrier gas and the hydrogen fire source ionization detector (FID detector). The type of capillary column was SE-30 (30 m × 0.5 mm × 0.32 μm) to analyze the component content in the product. The conversion of NB (XNB) and the selectivity to AN (SAN) were calculated according to eqs 1 and 2, respectively.

| 1 |

| 2 |

In the equations, CNB,0 is the initial NB concentration in the gas feed and CNB and CAN are the concentrations of NB and AN monitored by the online GC during the hydrogenation reaction, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 21371149 and 21671168), Hebei Youth Top-notch Talent Support Program, and Hebei Province Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars (C20200509).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c00441.

FTIR spectra of the γ-Al2O3 support and TEM images for morphology information (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ Y.J. and Q.L. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Daems N.; Wouters J.; Van Goethem C.; Baert K.; Poleunis C.; Delcorte A.; Hubin A.; Vankelecom I. F. J.; Pescarmona P. P. Selective Reduction of Nitrobenzene to Aniline Over Electrocatalysts Based on Nitrogen-doped Carbons Containing Non-noble Metals. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 226, 509–522. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.12.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corma A.; Concepción P.; Serna P. A Different Reaction Pathway for the Reduction of Aromatic Nitro Compounds on Gold Catalysts. Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 7404–7407. 10.1002/ange.200700823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Shao Z.-J.; Cao X.-M.; Hu P. Insights into Different Products of Nitrosobenzene and Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation on Pd(111) under Realistic Reaction Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 20337–20350. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b05364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi M.; Khodaei M. M.; Teymouri M.; Rashidi A.; Mohammadi H. Preparation of NiO Nanocatalyst Supported on MWCNTs and Its Application in Reduction of Nitrobenzene to Aniline in Liquid Phase. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 2016, 46, 959–967. 10.1080/15533174.2013.862646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serna P.; Boronat M.; Corma A. Tuning the Behavior of Au and Pt Catalysts for the Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Nitroaromatic Compounds. Top. Catal. 2011, 54, 439–446. 10.1007/s11244-011-9668-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.-F.; Chen Y.-W. Effect of Additive (W, Mo, and Ru) on Ni-B Amorphous Alloy Catalyst in Hydrogenation of p-Chloronitrobenzene. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 8866–8873. 10.1021/ie060751v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Wang L.; Shao Y.; Wang Y.; Gates B. C.; Xiao F. S. A Pd@Zeolite Catalyst for Nitroarene Hydrogenation with High Product Selectivity by Sterically Controlled Adsorption in the Zeolite Micropores. Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 9879–9883. 10.1002/ange.201703938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu J.; Wang J.; Lu C.; Ma L.; Zhang Q.; He X.; Li X. Size-Dependent Halogenated Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation Selectivity of Pd Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 2594–2601. 10.1021/jp411442f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha P.; Shanthi K.; Rao K. S. R.; Viswanathan B.; Selvam P. Hydrogenation of Nitrobenzene over palladium-supported catalysts-Effect of support. Appl. Catal., A 2009, 353, 160–165. 10.1016/j.apcata.2008.10.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verho O.; Gustafson K. P. J.; Nagendiran A.; Tai C. W.; Bäckvall J. E. Mild and Selective Hydrogenation of Nitro Compounds using Palladium Nanoparticles Supported on Amino-Functionalized Mesocellular Foam. Chemcatchem 2015, 6, 3153–3159. 10.1002/cctc.201402488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H.; Zhu X.; Chen R.; Liao Q.; Liu J.; Li L. High-Performance Gas-Liquid-Solid Microreactor with Polydopamine Functionalized Surface Coated by Pd Nanocatalyst for Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 306, 1017–1025. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hout S. I.; El-Sheikh S. M.; Hassan H. M. A.; Harraz F. A.; Ibrahim I. A.; El-Sharkawy E. A. A Green Chemical Route for Synthesis of Graphene Supported Palladium Nanoparticles: A Highly Active and Recyclable Catalyst for Reduction of Nitrobenzene. Appl. Catal., A 2015, 503, 176–185. 10.1016/j.apcata.2015.06.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.; Gu H.; Xu X.; Yan X. Selective Hydrogenation of O-chloronitrobenzene (o-CNB) over Supported Pt and Pd Catalysts Obtained by Laser Vaporization Deposition of Bulk Metals. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2009, 310, 144–149. 10.1016/j.molcata.2009.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Li K.; Xiang Y.; Zhou Y.; Wang Q.; Guo L.; Ma L.; Xu X.; Lu C.; Feng F.; Lv J.; Ni J.; Li X. Sulfur-doped Porous Carbon Supported Palladium Catalyst for High Selective O-Chloro-Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation. Appl. Catal., A 2019, 581, 74–81. 10.1016/j.apcata.2019.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turáková M.; Králik M.; Lehocký P.; Pikna Ĺ.; Smrčová M.; Remeteiová D.; Hudák A. Influence of Preparation Method and Palladium Content on Pd/C Catalysts Activity in the Liquid Phase Hydrogenation of Nitrobenzene to Aniline. Appl. Catal., A 2014, 476, 103–112. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P.; Teranishi T.; Asakura K.; Miyake M.; Toshima N. Polymer-Protected Ni/Pd Bimetallic Nano-Clusters:Preparation, Characterization and Catalysis for Hydrogenation of Nitrobenzene. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 9673–9682. 10.1021/jp992177p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Cui X.; Deng Y.; Shi F. Active Pd/Fe(OH)x Catalyst Preparation for Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation by Tracing Aqueous Phase Chlorine Concentrations in the Washing Step of Catalyst Precursors. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 6050–6054. 10.1016/j.tet.2014.02.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdullaev M. G.; Gebekova Z. G. Hydrogenation of Aromatic Nitro Compounds on Palladium-Containing Anion-Exchange Resins. Pet. Chem. 2016, 56, 146–150. 10.1134/s096554411602002x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Koenigsmann C.; Adzic R. R.; Wong S. S. Probing Ultrathin One-Dimensional Pd–Ni Nanostructures As Oxygen Reduction Reaction Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 2544–2555. 10.1021/cs500125y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Lizana F.; Gómez-Quero S.; Amorim C.; Keane M. A. Gas Phase Hydrogenation of P-chloronitrobenzene over Pd-Ni/Al2O3. Appl. Catal., A 2014, 473, 41–50. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Deng Y.; Shi F. Active Palladium Catalyst Preparation for Hydrogenation Reactions of Nitrobenzene, Olefin and Aldehyde Derivatives. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2014, 395, 195–201. 10.1016/j.molcata.2014.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Lizana F.; Gómez-Quero S.; Hugon A.; Delannoy L.; Louis C.; Keane M. A. Pd-Promoted Selective Gas Phase Hydrogenation of P-chloronitrobenzene Over Alumina Supported Au. J. Catal. 2009, 262, 235–243. 10.1016/j.jcat.2008.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Z.; Dong B.; Wang W.; Yang G.; Cao Y.; Wang H.; Yang Y.; Wang Q.; Peng F.; Yu H. Elucidating Interaction Between Palladium and N-Doped Carbon Nanotubes: Effect of Electronic Property on Activity for Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 2893–2901. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Jiang Z.; Li W.; Wang C.; Chen M.; Zhang G. The role of interfacial H-bonding on the electrical properties of UV-cured resin filled with hydroxylated Al2O3 nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 275710. 10.1088/1361-6528/ab824f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.; Bin D.; Yan B.; Du Y.; Majima T.; Zhou W. Porous Bimetallic PdNi Catalyst with High Electrocatalytic Activity for Ethanol Electrooxidation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 493, 190–197. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L.; Niu Y.; Wang Y.; Jiang Y.; Chen R.; Ma T.; Gao F. Controlled Synthesis of Pt-Pd Nanoparticle Chains with High Electrocatalytic Activity Based on Insulin Amyloid Fibrils. Nano 2016, 11, 1650063. 10.1142/s1793292016500636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mauriello F.; Paone E.; Pietropaolo R.; Balu A. M.; Luque R. Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenolysis of Lignin Derived Aromatic Ethers Promoted by Bimetallic Pd/Ni Systems. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 9269–9276. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Lu Z.-H.; Luo Y.; Zou A.; Yao Q.; Chen X. Mesoporous Carbon Nitride Supported Pd and Pd-Ni Nanoparticles as Highly Efficient Catalyst for Catalytic Hydrolysis of NH3BH3. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 1620–1626. 10.1002/cctc.201701989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.-P.; Wu F.-P.; Song Q.-L.; Fan X.; Jin L.-J.; Wang R.-Y.; Cao J.-P.; Wei X.-Y. Hydrodeoxygenation of Lignin Model Compounds to Alkanes over Pd-Ni/HZSM-5 Catalysts. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 899–910. 10.1016/j.joei.2019.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K.; Iizuka Y.; Xu Q. Nickel-palladium nanoparticle catalyzed hydrogen generation from hydrous hydrazine for chemical hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 11794–11801. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.06.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Li G.; Gao M.; Dong Y.; Yang M.; Cheng H. Wet-impregnated bimetallic Pd-Ni catalysts with enhanced activity for dehydrogenation of perhydro-N-propylcarbazole. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 32168–32178. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.08.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seshu Babu N.; Lingaiah N.; Sai Prasad P. S. Characterization and reactivity of Al2O3 supported Pd-Ni bimetallic catalysts for hydrodechlorination of chlorobenzene. Appl. Catal., B 2012, 111–112, 309–316. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W.; Wang Z.; He S.; Hao F.; Yang Y.; Lv Y.; Luo H. Nitrogen-doped Carbon Nanotubes as a Highly Active Metal-free Catalyst for Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 260, 118105. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.; Khetan A.; Yang F.; Migunov V.; Weide P.; Stürmer S. P.; Guo P.; Kähler K.; Xia W.; Mayer J.; Pitsch H.; Simon U.; Muhler M. Experimental and Theoretical Understanding of Nitrogen-Doping-Induced Strong Metal–Support Interactions in Pd/TiO2 Catalysts for Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1197–1206. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.; Ikushima Y.; Arai M. Hydrogenation of Nitrobenzene with Supported Platinum Catalysts in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide: Effects of Pressure, Solvent, and Metal Particle Size. J. Catal. 2004, 224, 479–483. 10.1016/j.jcat.2004.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Wang Y.; Li Y.; Lan X.; Ali B.; Wang T. Highly Efficient Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes by N-doped Carbon Supported Cobalt Single-atom Catalyst in Ethanol/water Mixed Solvent. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 34021–34031. 10.1021/acsami.0c06632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y.; Chen T.; Wang G. Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene catalyzed by Pd promoted Ni supported on C60 derivative. Asian Soc. Sci. 2019, 465, 888–894. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Du C.; Wei Q.; Shen W. Two-Dimensional Pd Nanosheets with Enhanced Catalytic Activity for Selective Hydrogenation of Nitrobenzene to Aniline. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 4358. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C.-H.; Guo X.-N.; Sankar M.; Yang H.; Ma B.; Zhang Y.-F.; Tong X.-L.; Jin G.-Q.; Guo X.-Y. Synergistic Effect of Segregated Pd and Au Nanoparticles on Semiconducting SiC for Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 23029–23036. 10.1021/acsami.8b04044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Wang W. D.; Sun X.; Fan M.; Hu X.; Dong Z. Palladium Nanoclusters Confined in MOF@COP as a Novel Nanoreactor for Catalytic Hydrogenation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 7285–7294. 10.1021/acsami.9b21802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Shen K.; Ding D.; Chen J.; Fan T.; Wu R.; Li Y. Solvent-driven selectivity control to either anilines or dicyclohexylamines in hydrogenation of nitroarenes over a bifunctional Pd/MIL-101 catalyst. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10641–10648. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv M.; Yu S.; Liu S.; Li L.; Yu H.; Wu Q.; Pang J.; Liu Y.; Xie C.; Liu Y. One-pot synthesis of stable Pd@mSiO2 core–shell nanospheres with controlled pore structure and their application to the hydrogenation reaction. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 7015–7024. 10.1039/c9dt01269a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Zhu X.; Chen R.; Liao Q.; Ye D.; Zhang B.; Feng H.; Liu J.; Liu M.; Wang K. Hierarchical Pd@Ni catalyst with a snow-like nanostructure on Ni foam for nitrobenzene hydrogenation. Appl. Catal., A 2019, 575, 238–245. 10.1016/j.apcata.2019.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.; Zhang X.; Qin Z.; Zhang L.; Ye Y.; Cao M.; Gao L.; Jiao T. Preparation of PdNPs doped chitosan-based composite hydrogels as highly efficient catalysts for reduction of 4-nitrophenol. Colloids Surf., A 2021, 611, 125889. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Wang R.; Deng H.; Zhang L.; Gao L.; Zhang L.; Jiao T. Facile Preparation of Self-Assembled Chitosan-Based POSS-CNTs-CS Composite as High-Efficient Dye Absorbent for Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 294–300. 10.1021/acsomega.0c04565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S.; Wang R.; Hei P.; Gao L.; Yang J.; Jiao T. Self-assembled Ni2P nanosheet-implanted reduced graphene oxide composite as highly efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Colloids Surf., A 2021, 612, 125992. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C.; Yin J.; Zhao J.; Li X.; Wang S.; Bai Z.; Jiao T. Facile preparation and highly efficient photodegradation performances of self-assembled Artemia eggshell-ZnO nanocomposites for wastewater treatment. Colloids Surf., A 2021, 610, 125752. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Wang R.; Liu Z.; Gao L.; Jiao T.; Liu Z. Ni2P/MoS2 Interfacial Structures Loading on N-doped Carbon Matrix for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Green Energy Environ. 2020, 10.1016/j.gee.2020.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H.; Yin J.; Ma J.; Zhou J.; Zhang L.; Gao L.; Jiao T. Exploring the enhanced catalytic performance on nitro dyes via a novel template of flake-network Ni-Ti LDH/GO in-situ deposited with Ag3PO4 NPs. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 543, 148821. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.148821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J.; Ge B.; Jiao T.; Qin Z.; Yu M.; Zhang L.; Zhang Q.; Peng Q. Self-Assembled Sandwich-Like MXene-Derived Composites as Highly Efficient and Sustainable Catalysts for Wastewater Treatment. Langmuir 2021, 37, 1267–1278. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c03297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L.; Yin J.; Yan D.; Hong W.; Jiao T. Construction of Nanocrystalline Cellulose-Based Composite Fiber Films with Excellent Porosity Performances via an Electrospinning Strategy. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 4958–4967. 10.1021/acsomega.0c06002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Wang R.; Wang J.; Li J.; Jiao T.; Liu Z. Facile fabrication of molybdenum compounds (Mo2C, MoP and MoS2) nanoclusters supported on N-doped reduced graphene oxide for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction over broad pH range. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129233. 10.1016/j.cej.2021.129233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Yin J.; Wei K.; Li B.; Jiao T.; Chen Y.; Zhou J.; Peng Q. Fabrication of hierarchical SrTiO3@MoS2 heterostructure nanofibers as efficient and low-cost electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 205604. 10.1088/1361-6528/ab70ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J.; Zhan F.; Jiao T.; Wang W.; Zhang G.; Jiao J.; Jiang G.; Zhang Q.; Gu J.; Peng Q. Facile preparation of self-assembled MXene@Au@CdS nanocomposite with enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production activity. Sci. China Mater. 2020, 63, 2228–2238. 10.1007/s40843-020-1299-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.; Yin J.; Liu S.; Wang Y.; Li B.; Jiao T. Facile Synthesis of Ag/Pd Nanoparticles-Loaded Polyethyleneimine Composite Hydrogels with Highly Efficient Catalytic Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 3725–3733. 10.1021/acsomega.9b04408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.