Abstract

Tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) is a medical emergency occurring when large numbers of cancer cells rapidly undergo cell death. The resultant metabolic abnormalities results in significant morbidity and mortality. Tumour lysis syndrome most commonly occurs in 5% of haematological malignancies and is less commonly described in solid organ cancers. In breast cancer, TLS has been reported to occur both spontaneously and as a result of cancer chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or radiotherapy. However, only 1 TLS case in a breast cancer patient has been reported as a consequence of aromatase inhibitor letrozole. With the increased recent use of CDK4/6 inhibitors, 2 cases of hyperuricaemia in patients with breast cancer treated with palbociclib/letrozole combination treatment have also been reported. We present the second case of letrozole-induced TLS in a 74-year-old woman with occult breast adenocarcinoma. Despite treatment with recombinant urate oxidase and intravenous fluids, the patient deteriorated and was discharged with hospice care. Although rare, this life-threatening condition should be considered in an acutely unwell patient commencing treatment for solid malignant tumours.

Keywords: Medical oncology, tumour lysis syndrome, adverse effects, aromatase inhibitors

Introduction

Tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) occurs as a result of the rapid death of malignant cells and the subsequent necrosis-related release of potentially harmful metabolites and electrolytes. The syndrome was first reported in a case of solid organ malignancy in 1983.1 The syndrome can be detected based on laboratory biochemical parameters, namely an increase in serum potassium, uric acid, and phosphate and a reduction in serum calcium. The widely accepted criteria for diagnosing laboratory TLS were published by Cairo and Bishop in 2004.2 Clinical TLS diagnosis is made when renal impairment, cardiac arrhythmias, and seizures occur in the context of these biochemically detected changes.

Tumour lysis syndrome is typically seen in haematological malignancies rather than solid organ malignancies and most commonly in Burkitt’s lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. The incidence of TLS in acute leukaemias and non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) in an international retrospective analysis was 5.3%.3 The incidence of TLS in solid organ malignancies is difficult to determine because the data are mostly limited to case reports and case series.

Several factors are known to increase the risk of TLS, the most significant being large tumour burden of a rapidly proliferating cancer, pre-existing renal impairment, advanced age, and presence of a chemo-sensitive tumour. The risk is also greater at the induction of chemotherapy.3 Intravenous fluids and/or prophylactic medication in the form of either allopurinol or rasburicase is usually given before the induction of chemotherapy to patients considered at risk. Guidance for identifying high-risk patients with haematological malignancies has been offered by other authors.4 Tumour lysis syndrome may also occur spontaneously before any chemotherapy has been given in the presence of large tumour burden and cell death occurring at a significant rate.

We present the case of a 74-year-old female patient with a diagnosis of occult metastatic oestrogen-positive breast cancer, who developed TLS days after commencing treatment with the aromatase inhibitor letrozole. Given that the occurrence of TLS was rare in this context, a search of the literature using a PubMed search with the search terms ‘Breast cancer’/‘breast adenocarcinoma’/‘breast carcinoma’ and ‘tumour lysis syndrome’/‘TLS’ returned 40 results, 14 of which were deemed to be of relevance to review. One publication was in Japanese, but the abstract was available in English.5 Within these results, there was only one published case of TLS reported following treatment with letrozole. These papers will be elaborated in the discussion.

Case Report

A 74-year-old woman with no prior history of cancer was admitted under the acute medical team, presenting with a 3-month history of progressively worsening dyspnoea and a 1-month history of nonproductive cough. She denied presence of haemoptysis, fevers, chest pain, or palpitations. She complained of significant lethargy and anorexia but denied weight loss.

Her past medical history included hypothyroidism, Type-II diabetes, hypertension, and osteoarthritis. She was independent with all Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and was able to perform tasks such as mowing the lawn. She was an ex-smoker having stopped 18 years ago with 5-pack years cigarette smoking history. She had never had spirometry performed and did not have need for any inhalers; she was not suspected to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). She had been prescribed furosemide by her general practitioner (GP) for presumed cardiac failure as the cause of her dyspnoea, but this had not improved the symptoms.

On examination, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score at presentation was 3. Her oxygen saturations on arrival to the emergency department were 91% on room air. She had reduced air entry of the left lung base and pitting leg oedema bilaterally up to the shins. She had no palpable breast masses or adenopathy.

Chest X-ray (CXR) on hospital admission showed a large left-sided pleural effusion. Laboratory work returned an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) of 97 mg/L with normal white cell count (WCC) (8.4 × 109/L) and reduced renal function (urea 11.6 mmol/L, creatinine 100 umol/L, and eGFR 48 mL/min). Liver function tests were all within normal range (bilirubin 5 umol/L, alkaline phosphatase 93 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase 17 U/L, alanine transferase 16 U/L, total protein 76 g/L, and albumin 34 g/L) except for a slightly elevated globulin (42 g/L).

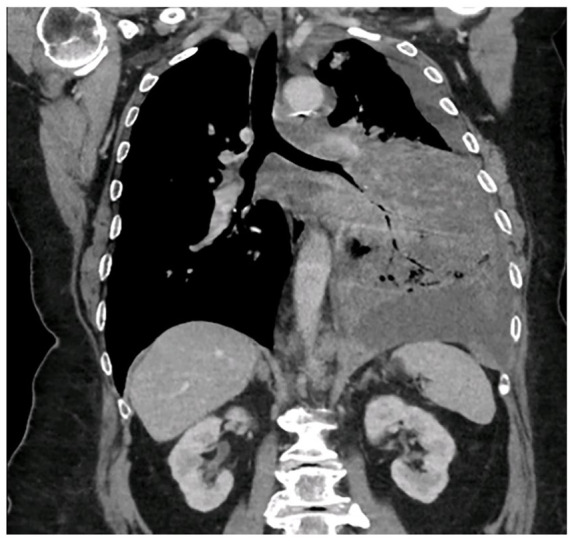

A pleurocentesis was performed, and 1 L of blood-stained fluid was drained which achieved symptomatic improvement. A subsequent CXR performed following pleurocentesis showed a large underlying mass, suspicious for malignancy. Computed tomography (CT) thorax, abdomen, and pelvis scan showed subtotal consolidation and infiltration of the left lower lobe with moderate size left pleural effusion, with widespread mediastinal lymphadenopathy measuring up to 21 mm in the pretracheal region (Image 1). No gastrointestinal or bladder pathology was identified on imaging. Computed tomography brain imaging was not performed because the patient did not have any focal neurology, reduced conscious level, or headache at presentation. Bronchoscopy was performed which showed extrinsic compression, and washings were sent for analysis.

Image 1.

Computed tomography (CT) image showing a large infiltrating mass in the left lung with moderate pleural effusion and bulky mediastinal adenopathy.

CT indicates computed tomography.

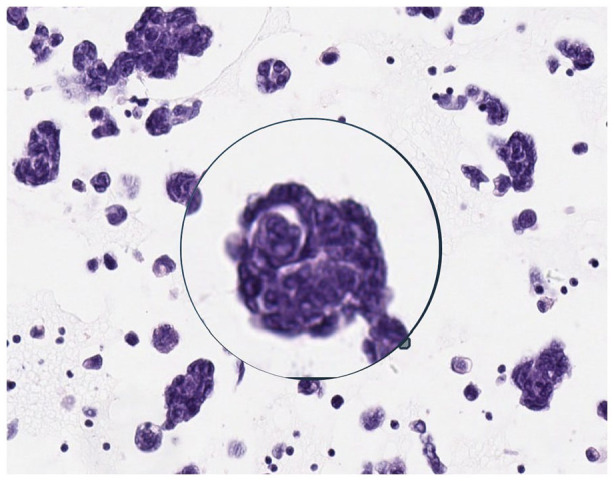

Histology from the pleural fluid returned to be metastatic poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, Gata-3 positive and negative for cytokeratin 20, and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1). While a primary breast tumour was not identified, the presentation, CT imaging, and the patterns of staining were consistent with occult metastatic breast carcinoma. On microscopy, a significant level of cell cannibalism was identified (Image 2). Oestrogen receptor (ER) status was strongly positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) negative. With the patient’s consent, letrozole 2.5 mg per dose orally was commenced as part of palliative treatment for breast cancer. The option of adding a CDK4-6 inhibitor was discussed with the patient to improve progression-free survival but was unfunded in New Zealand at that juncture and was beyond the financial means of the patient.

Image 2.

Microscopy of pleural fluid sample showing cell cannibalism. In the background, there are other vacuolated tumour cells, some of which are engulfing cellular fragments and other material.

The following day, the patient was due to be discharged home when she developed a fever of 38.2°C. At this time, she met the clinical criteria for sepsis management and as such broad-spectrum antibiotics were started (co-amoxiclav intravenous, 1.2 g 3 times daily). Laboratory work identified an acute kidney injury and a raised potassium of 6.1 mmol/L. Appropriate treatment was given to manage hyperkalaemia and intravenous fluids were given. Three days later, the serum creatinine had increased further with associated elevated phosphate and uric acid. It was now recognised that the patient was in TLS. Rasburicase 3 mg was given once daily for 3 days with aggressive intravenous (IV) fluid therapy. Serum levels were checked twice daily, and the laboratory analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The renal function results from admission (D − 10), commencement of treatment (D0), and until discharge to hospice care (D + 8).

| D − 10: Day of admission | D0: Letrozole initiated | D + 2 | D + 4 | D + 6: TLS diagnosis suspected, rasburicase given | D + 7 | D + 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na) mmol/L | 137 | 136 | 136 | 133 | 127 | 124 | 124 |

| Potassium (K) mmol/L | 4.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 5.1 |

| Urea mmol/L | 11.6 | 16.3 | 13.9 | 16.0 | 21.4 | 26.1 | 30.5 |

| Creatinine umol/L | 100 | 137 | 114 | 131 | 211 | 284 | 262 |

| eGFR mL/min | 48 | 33 | 41 | 35 | 19 | 14 | 15 |

| Uric acid mmol/L | 0.74 | 0.21 | |||||

| Calcium mmol/L | 2.20 | 2.26 | |||||

| Phosphorous mmol/L | 1.87 | 1.86 | |||||

| CRP mg/L | 97 | 125 | 280 | 462 | 428 |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; TLS, tumour lysis syndrome.

Renal function stabilised for 24 h; however at this point, it was clear that the patient had clinically deteriorated significantly. She was increasingly drowsy throughout the day and less responsive. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score fluctuated between 12 and 14 due to confusion and was often not rousable to pain. Vital signs were progressively worsening with reducing oxygen saturations and an increasing supplementary oxygen requirement. Blood cultures never identified a causative organism, and the patient had a single isolated fever at the time of initiating sepsis management. The authors postulate that this patient was not necessarily septic at all during the acute illness but that these symptoms had been related to malignant disease and the development of TLS. The impression was that the patient was approaching the end of life, and after discussion with family, she was discharged home with hospice cares in place. She passed away 2 days after discharge.

Discussion

Tumour lysis syndrome is more commonly associated with haematological malignancies. It is a medical emergency that rarely occurs in metastatic solid tumours. Tumour lysis syndrome in metastatic solid tumours has predominantly occurred in patients receiving chemotherapy. We present a rare and fatal case of TLS in a patient with luminal metastatic breast cancer which initially posed as a diagnostic challenge and manifested within days upon commencement of letrozole. We conducted a review of the literature and discuss the differential diagnosis and challenges faced with management of this unique case.

Letrozole is a selective aromatase inhibitor, used predominantly in the treatment of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women and has been approved for medical use since 1996.6 Common side effects include dizziness, low mood, fatigue, and arthralgia. The less common but more serious adverse effects included in the safety information for letrozole are osteoporosis and subsequent fractures, increases in cholesterol, and fatigue with dizziness. To our knowledge, there has only been one other case report describing TLS as a consequence of letrozole and 2 cases of hyperuricaemia associated with palbociclib/letrozole combination treatment. Zigrossi et al7 reported in 2001 on a patient who went into cardio-pulmonary shock with laboratory TLS after treatment with a single dose of letrozole. The patient was in a critical condition for 2 weeks but did gradually improve and had a 20-month period in remission following discharge home and remained alive at time of publication.

A recent review of the literature by Mirrakhimov et al identified and reviewed all published cases of TLS in solid organ malignancies.8 A total of 115 cases were reported between 1950 and February 2014. Eighteen cases of TLS occurring in breast cancer have been reported in the literature,9-23 13 of which occurred in the context of systemic anticancer treatment. Twelve of these are written in English and were available to be reviewed. Bromberg et al14 reported 2 cases of hyperuricaemia occurring in patients undergoing combination palbociclib/letrozole treatment, and suggest that one if not both of these cases may be presentations of TLS. A summary of all these cases, as well as 2 cases of spontaneous TLS in breast cancer10,11 and a case of TLS following hemibody irradiation13 can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

A summary of all case reports of TLS and hyperuricaemia available in literature at time of publication, detailing publication author, patient age, any specifics of the tumour type and stage (where reported in the publication), treatment given, risk factors specified, and outcome.

| Author | Age | Diagnosis | Current treatment | Risk factors specified | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zigrossi et al7 | 61 | Invasive ductal cell carcinoma, T2N0. ER+, PR+. | Letrozole | Developed TLS on D2. Letrozole held, supportive management given was alive 20 months later. | |

| Bromberg et al14 | 78 | Advanced, ER+, HER2− ductal tumour. | Palbociclib/letrozole | Widespread metastases | Severe kidney injury resolved with intravenous fluids and allopurinol. Palbociclib dose reduced for ongoing treatment. |

| Bromberg et al14 | 86 | Advanced, ER+, HER2− ductal tumour. | Palbociclib/letrozole | Liver metastases | Developed hyperuricaemia was given allopurinol and encouraged to increase oral fluid intake. Uric acid level reduced and palbociclib restarted at lower dose. |

| Mott et al15 | 44 | Metastatic ER+, PR+ and HER2 overexpressing carcinoma. | Gemcitabine and cisplatin | Developed nausea and vomiting. Fluids and allopurinol then rasburicase given, full recovery of renal function made. | |

| Aslam et al16 | 58 | Invasive poorly differentiated ductal carcinoma with widespread metastases. ER−, PR−, HER+. | Gemcitabine | Widespread metastases | Developed TLS on D4. Was discharged to hospice. |

| Baudon et al17 | 58 | Invasive grade-III ductal carcinoma, ER−, PR−, HER2−. Locally advanced and very widespread bony metastases. | Trastuzumab and pertuzumab | High LDH at start of treatment and reduced eGFR (53). Widespread disease | Developed organ failure on D2 and died 48 h later from multiorgan dysfunction. |

| Taira et al18 | 69 | Invasive ductal carcinoma, triple-disease, T2N1M0, stage IIB | Trastuzumab | Liver metastases present. | Developed a cardiac arrhythmia on D6 of trastuzumab, died from acute renal failure on D11. |

| Mott et al15 | 47 | Stage I, ER+, PR−, HER2− cancer diagnosed 4 years earlier. | 5-Fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide | Developed TLS 24 h into treatment. Fluids given with allopurinol and renal function gradually improved. | |

| Stark et al19 | 53 | Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinoma, ER+, PR−. | 5-Fluorouracil, docetaxel, cyclophosphamide | Extensive metastases, very elevated LDH, and raised urea. | 18 h posttreatment developed TLS, suffered cardiac arrest 48 hours later. |

| Vaidya and Acevedo20 | 52 | Locally recurrent, invasive ductal cell carcinoma, ER+, PR+, HER2−. | Single dose paclitaxel | Liver metastases | Became encephalopathic on D7 and died during haemofiltration. |

| Ustündağ et al21 | 56 | Tumour type not specified. | Paclitaxel | Metastases, pre-existing elevated LDH. | Became oliguric during first infusion and became confused. Started haemofiltration but died within 24 h from cardiac arrest. |

| Kurt et al22 | 42 | Invasive ductal carcinoma, stage IIB. | Capecitabine | Liver metastases present. | 11 h into capecitabine became confused, bradycardic, and oliguric. GCS 11 and died shortly after. |

| Drakos et al23 | 31 | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma, T2N1M0, ER+. | Mitoxantrone | Liver metastases. Normal renal function. | Developed biochemical and clinical TLS on D3. Died 1 month later from hepatic failure secondary to infiltrative disease. |

| Cech et al9 | 94 | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma. Hormone profile not performed. | Tamoxifen | Extensive metastatic disease including widespread bony metastases. | Renal function deteriorated on D7. Patient died 2 months later from congestive cardiac failure. |

| Parsi et al12 | 36 | Grade-4 invasive ductal carcinoma. ER+, PR+, HER2+. | No treatment started before developing TLS. | Widespread innumerable metastases. | Spontaneous development of TLS after diagnosis of breast cancer but before starting treatment. Recovery from acute TLS with IV fluids and rasburicase. |

| Idrees et al11 | 48 | Infiltrating ER+, PR+, HER2−, p53−, Ki67 10% carcinoma with bony and liver metastases. | No treatment had been given before TLS. | Bony and liver metastases. | Presentation with abdominal pain and oliguria. Found to be in spontaneous TLS from an as-yet undiagnosed breast cancer with widespread metastatic disease. |

| Sklarin and Markham10 | 62 | Infiltrating lobar carcinoma, with lung, liver, and bone metastases. | No treatment before TLS diagnosis. Then recurred with treatment. | Bony and liver metastases. | Already fulfilling criteria for TLS at time of initially presented with breast mass. Further episode of TLS following treatment with dibromodulcitol, doxorubicin, vincristine, tamoxifen, Halotestin, methotrexate, and leucovorin. |

| Rostom et al13 | 73 | Male patient with widespread LN infiltration and bony disease. | Hemibody irradiation | Widespread metastases. | Developed renal failure 48 h after irradiation treatment, failed to respond to allopurinol and IV fluids, developed coma, and died 5 days following treatment. |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ER, oestrogen receptor; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LN, lymph node; −, negative; +, positive; PR, progesterone receptor; TLS, tumour lysis syndrome.

All patients were female. Number of days after treatment represented by ‘D’.

The differential diagnosis in this case of a febrile elderly patient with known cancer commencing antiendocrine treatment initially included sepsis, hyperprogression of cancer or pulmonary embolus (PE). Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started when the patient developed a fever; however, there was no significant change in her other vital signs, no further fever, no rise in WCC to accompany the rise in CRP, and no evidence for a focus of infection such as new infective symptoms or positive investigations such as urinalysis. She was not complaining of new chest pain and had no electrocardiograph (ECG) changes characteristic of PE. A D-dimer test was not performed because this is likely to be raised in widespread malignancy and is of less diagnostic use. Alveolar-arterial gradient was calculated by way of arterial blood gas and was not reduced, thus was not in keeping with PE. Blood cultures were sent and no causative organism was ever cultured. Serial CXR excluded the presence of empyema or parapneumonic effusion. The manner in which the patient deteriorated with fluctuating but reduced conscious level and renal failure, without ongoing fevers, tachycardia, or tachypnoea, was clinically less convincing for infection and resultant sepsis.

Disease hyperprogression would be a possible cause for clinical deterioration. A trending rise in CRP may well herald a disease progression. This rise was very rapid, with a tripling of CRP over a few days. C-reactive protein rise is a well-known predictor for cardiovascular mortality but poorly described in association with TLS; a literature search for the significance of rising CRP in the context of TLS did not return any results of relevance to this case. Tumour lysis syndrome was not immediately suspected, and indeed it was only on review by a medical oncologist that TLS was suggested as a differential diagnosis and the appropriate laboratory work was sent. There may have been a delay in recognition of the development of TLS, partly as a result of the patient being managed on a general medical ward and the scarcity of reports highlighted in the medical literature of TLS induced by letrozole. The rapid deterioration in renal function within 24 h of commencing letrozole, with the rise in potassium, phosphate, and uric acid and accompanying clinical deterioration is diagnostic of laboratory and clinical TLS. Serum calcium remained within normal range in this case. Whether tumour lysis was spontaneous versus that induced by letrozole also remains debatable. However, given the likely lengthy time between carcinogenesis and presentation to hospital, it would seem less likely that a spontaneous TLS would happen to occur within 24 h of commencing Letrozole treatment.

Microscopy performed on a sample of the pleural fluid taken before commencing letrozole identified high levels of cell cannibalism. Abodief et al24 performed microscopy on fluid from both malignant and benign pleural effusions and exclusively identified cell cannibalism in malignant effusions. Siddiqui et al25 identified a higher rate of cell cannibalism in more aggressive de-differentiated oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCCs) when compared to well-differentiated OSCC and concluded that higher rates of cell cannibalism are suggestive of aggressive tumour behaviour. The risk of TLS is greater when treating a more aggressive and more rapidly growing tumour. Whether significant levels of cell cannibalism should raise clinical suspicion for the development of TLS in a solid organ malignancy requires further research.

Tumour lysis syndrome secondary to letrozole is a rare occurrence, and it is not possible to calculate an incidence with small numbers of case reports; larger cohort studies would be required. Cohort studies would also be required to determine any statistical significance of these factors to better stratify risk and aid appropriate monitoring in future.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of TLS in an elderly patient with occult luminal breast cancer with large tumour burden and metastatic disease who developed TLS when commenced on letrozole. Physicians should include TLS as a differential diagnosis for an acutely deteriorating patient with metastatic cancer. In particular, elderly patients with large tumour bulk, pre-existing renal impairment, and those who have just commenced on anticancer treatment are at greater risk. Whether cell cannibalism is associated with tumour lysis requires further research.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: G.W. was the author of the paper. P.H.D. was a supervising clinician and also edited the manuscript before submission.

Ethical Approval/Patient Consent: The patient in the case died before gaining their consent for this case to be written up. Verbal consent was gained from family members. No identifiable data are contained within this case report. Only age, gender, and the name of the treatment centre are contained within the report.

ORCID iD: George E Watkinson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7398-4333

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7398-4333

References

- 1. Vogelzang NJ, Nelimark RA, Nath KA. Tumor lysis syndrome after induction chemotherapy of small-cell bronchogenic carcinoma. JAMA. 1983;249:513-514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:3-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Annemans L, Moeremans K, Lamotte M, et al. Incidence, medical resource utilisation and costs of hyperuricemia and tumour lysis syndrome in patients with acute leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in four European countries. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:77-83. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000054661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cairo MS, Coiffier B, Reiter A, Younes A; TLS Expert Panel. Recommendations for the evaluation of risk and prophylaxis of tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) in adults and children with malignant diseases: an expert TLS panel consensus. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:578-586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawaguchi Ushio A, Hattori M, Kohno N, Kaise H, Iwata H. Gemcitabine-induced tumour lysis syndrome caused by recurrent breast cancer in a patient without haemodialysis. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2013;40:1529-1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/020726s014lbl.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2020.

- 7. Zigrossi P, Brustia M, Bobbio F, Campanini M. Flare and tumor lysis syndrome with atypical features after letrozole therapy in advanced breast cancer. A case report. Ann Ital Med Int. 2001;16:112-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mirrakhimov AE, Ali AM, Khan M, Barbaryan A. Tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors: an up to date review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5389. doi:10.4081/rt.2014.5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cech P, Block JB, Cone LA, Stone R. Tumor lysis syndrome after tamoxifen flare. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:263-264. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607243150417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sklarin NT, Markham M. Spontaneous recurrent tumor lysis syndrome in breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1995;18:71-73. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Idrees M, Fatima S, Bravin E. Spontaneous tumor lysis syndrome: a rare presentation in breast cancer. J Med Case. 2019;10:24-26. https://journalmc.org/index.php/JMC/article/view/3237/2532 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parsi M, Rai M, Clay C. You can’t always blame the chemo: a rare case of spontaneous tumor lysis syndrome in a patient with invasive ductal cell carcinoma of the breast. Cureus. 2019;11:e6186. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rostom AY, El-Hussainy G, Kandil A, Allam A. Tumor lysis syndrome following hemi-body irradiation for metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1349-1351. doi: 10.1023/a:1008347226743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bromberg DJ, Valenzuela M, Nanjappa S, Pabbathi S. Hyperuricemia in 2 patients receiving palbociclib for breast cancer. Cancer Control. 2016;23:59-60. doi: 10.1177/107327481602300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mott FE, Esana A, Chakmakjian C, Herrington JD. Tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors. Support Cancer Ther. 2005;2:188-191. doi:10.3816/SCT.2005.n.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aslam HM, Zhi C, Wallach SL. Tumor lysis syndrome: a rare complication of chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:e4024. doi:10.7759/cureus.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baudon C, Duhoux FP, Sinapi I, Canon JL. Tumor lysis syndrome following trastuzumab and pertuzumab for metastatic breast cancer: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:178. doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-0969-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taira F, Horimoto Y, Saito M. Tumor lysis syndrome following trastuzumab for breast cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Breast Cancer. 2015;22:664-668. doi: 10.1007/s12282-013-0448-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stark ME, Dyer MC, Coonley CJ. Fatal acute tumor lysis syndrome with metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1987;60:762-764. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870815)60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vaidya GN, Acevedo R. Tumor lysis syndrome in metastatic breast cancer after a single dose of paclitaxel. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:308.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ustündağ Y, Boyacioğlu S, Haznedaroğlu IC, Baltali E. Acute tumor lysis syndrome associated with paclitaxel. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:1548-1549. doi: 10.1177/106002809703101221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurt M, Eren OO, Engin H, Güler N. Tumor lysis syndrome following a single dose of capecitabine. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:902. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drakos P, Bar-Ziv J, Catane R. Tumor lysis syndrome in nonhematologic malignancies. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1994;17:502-505. doi:10.1097/00000421-199412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abodief WT, Dey P, Al-Hattab O. Cell cannibalism in ductal carcinoma of breast. Cytopathology. 2006;17:304-305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Siddiqui S, Singh A, Faizi N, Khalid A. Cell cannibalism in oral cancer: a sign of aggressiveness, de-evolution, and retroversion of multicellularity. J Cancer Res Ther. 2019;15:631-637. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_504_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]