Abstract

Aim

cAMP typically signals downstream of Gs‐coupled receptors and regulates numerous cell functions. In β‐cells, cAMP amplifies Ca2+‐triggered exocytosis of insulin granules. Glucose‐induced insulin secretion is associated with Ca2+‐ and metabolism‐dependent increases of the sub‐plasma‐membrane cAMP concentration ([cAMP]pm) in β‐cells, but potential links to canonical receptor signalling are unclear. The aim of this study was to clarify the role of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptors (GLP1Rs) for glucose‐induced cAMP signalling in β‐cells.

Methods

Total internal reflection microscopy and fluorescent reporters were used to monitor changes in cAMP, Ca2+ and ATP concentrations as well as insulin secretion in MIN6 cells and mouse and human β‐cells. Insulin release from mouse and human islets was also measured with ELISA.

Results

The GLP1R antagonist exendin‐(9‐39) (ex‐9) prevented both GLP1‐ and glucagon‐induced elevations of [cAMP]pm, consistent with GLP1Rs being involved in the action of glucagon. This conclusion was supported by lack of unspecific effects of the antagonist in a reporter cell‐line. Ex‐9 also suppressed IBMX‐ and glucose‐induced [cAMP]pm elevations. Depolarization with K+ triggered Ca2+‐dependent [cAMP]pm elevation, an effect that was amplified by high glucose. Ex‐9 inhibited both the Ca2+ and glucose‐metabolism‐dependent actions on [cAMP]pm. The drug remained effective after minimizing paracrine signalling by dispersing the islets and it reduced basal [cAMP]pm in a cell‐line heterologously expressing GLP1Rs, indicating that there is constitutive GLP1R signalling. The ex‐9‐induced reduction of [cAMP]pm in glucose‐stimulated β‐cells was paralleled by suppression of insulin secretion.

Conclusion

Agonist‐independent and glucagon‐stimulated GLP1R signalling in β‐cells contributes to basal and glucose‐induced cAMP production and insulin secretion.

Keywords: adenylyl cyclase, exendin‐(9‐39), glucagon, glucagon‐like peptide‐1, insulin secretion, pancreatic islets

1. INTRODUCTION

Appropriate insulin secretion from pancreatic β‐cells is critical for glucose homeostasis and defective β‐cell function may consequently lead to impaired glucose tolerance and overt diabetes mellitus. 1 Glucose is the major physiological regulator of insulin release but secretion is also modulated by neural factors and hormones. Glucagon from pancreatic α‐cells, and the incretin hormones glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) and glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide from enteroendocrine L‐ and K‐cells respectively amplify glucose‐stimulated insulin release. 2 , 3 , 4 Glucose stimulus‐secretion coupling involves uptake and metabolism of the sugar in the β‐cell, an increased intracellular ATP/ADP ratio, closure of ATP‐sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, membrane depolarisation and Ca2+ influx through voltage‐dependent channels. The resulting increase of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration triggers exocytosis of insulin secretory granules. 4 , 5 Glucose metabolism also generates factors that amplify insulin secretion by enhancing exocytosis without influencing the triggering Ca2+ signal. 3 , 5 One such amplifying factor is cAMP. It is produced by adenylyl cyclases and degraded via phosphodiesterases and amplifies insulin secretion by activating protein kinase A and Epac2. 6 Adenylyl cyclase activity is typically stimulated by activation of Gsα‐coupled receptors, like glucagon and GLP‐1 receptors, 6 , 7 but also glucose stimulation elevates cAMP in β‐cells. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Recordings of cAMP and protein kinase A activity in single β‐cells have demonstrated that the glucose‐induced cAMP increase often is characterized by oscillations, 10 , 12 , 13 which along with similar oscillations of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration contribute to the generation of pulsatile insulin release. 6 , 10

The mechanisms underlying glucose‐induced cAMP formation in β‐cells remain unclear. It is well established that cAMP production is stimulated by Ca2+, 14 , 15 which is explained by the expression of Ca2+‐activated adenylyl cyclase isoforms. 13 , 16 , 17 Ca2+‐inhibited adenylyl cyclase isoforms 18 , 19 and Ca2+‐activated phosphodiesterases 20 , 21 , 22 appears less important but may contribute to the generation of oscillations. 22 , 23 In addition to Ca2+, there is a stimulatory effect of cell metabolism on adenylyl cyclases, 10 which might be due to increase of ATP, 10 the substrate for cAMP production, and lowering of AMP, 24 an inhibitor of adenylyl cyclase activity. 25 It has been suggested that paracrine glucagon release from α‐cells is crucial for the β‐cell cAMP response. 26 , 27 Glucagon may activate not only glucagon receptors but also GLP‐1 receptors. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 Studies in islets from GLP‐1 receptor‐deficient mice have shown lower glucose‐induced cAMP production, 31 and GLP‐1 receptor inhibition with exendin‐(9‐39) (ex‐9) reduces glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion in mouse and human islets 27 , 30 , 31 and perfused mouse pancreas. 29

In this study, we used live‐cell imaging techniques and ELISA hormone detection to clarify the involvement of Gsα‐coupled receptors for glucose‐induced changes of the sub‐plasma membrane cAMP concentration ([cAMP]pm) in MIN6 cells and primary mouse and human β‐cells. We demonstrate that constitutive agonist‐independent, and glucagon‐activated GLP‐1 receptor signalling is involved in basal and glucose‐stimulated cAMP production and insulin secretion.

2. RESULTS

2.1. GLP‐1 receptor antagonism inhibits both GLP‐1‐ and glucagon‐stimulated cAMP production in β‐cells

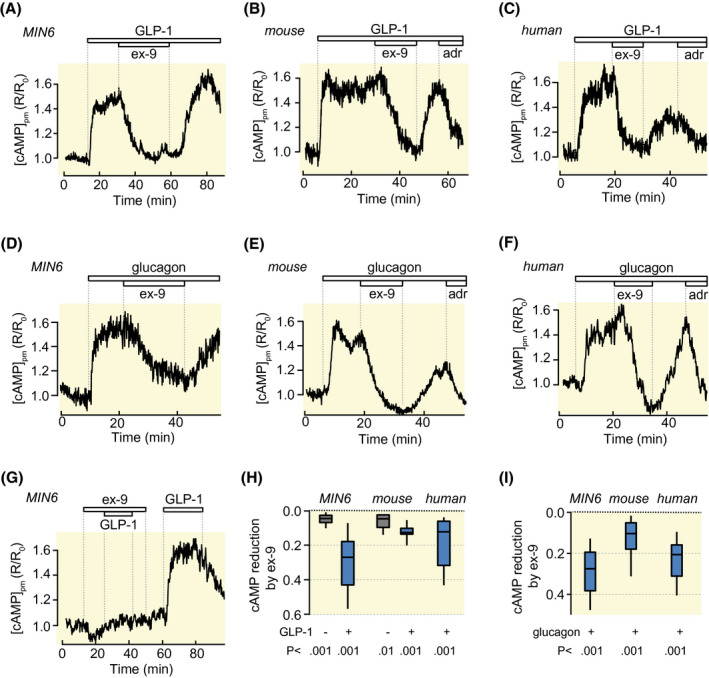

Recordings of [cAMP]pm with a ratiometric translocation biosensor in single MIN6‐cells and primary β‐cells within intact mouse and human pancreatic islets exposed to 3 mmol/L glucose showed that all cell preparations responded as expected to both GLP‐1 (Figure 1A‐C) and glucagon (Figure 1D‐F) at 10 nmol/L with a prompt increase of [cAMP]pm. In most cells, the [cAMP]pm elevation was sustained throughout the stimulation period, whereas in a few cases the response was transient (not shown). The GLP‐1 receptor antagonist ex‐9 suppressed not only the [cAMP]pm increase induced by GLP‐1 (Figure 1A‐C,H), but also that of glucagon (Figure 1D‐F,I), and there was a slight effect also on basal [cAMP]pm (Figure 1G,H). The effect of ex‐9 was reversible and [cAMP]pm often reached near maximally stimulated levels within 10‐15 minutes after washout of the inhibitor.

FIGURE 1.

GLP‐1 receptor antagonism inhibits both GLP‐1‐ and glucagon‐stimulated [cAMP]pm increases in β‐cells. A‐C, [cAMP]pm recordings from a single MIN6 β‐cell (A, representative for 26 cells from four experiments), and single mouse (B, 36 cells from eight experiments) and human (C, representative for 20 cells from five experiments with islets from two donors) β‐cells within intact islets, showing that ex‐9 prevents the [cAMP]pm elevation induced by 10 nmol/L GLP‐1. The [cAMP]pm‐lowering effect of 10 µmol/L adrenaline (adr) is used to verify the identity of the islet β‐cells. D‐F, Similar [cAMP]pm recordings from single MIN6 (D, representative for 25 cells from four experiments), mouse (E, representative for 20 cells from six experiments) and human (F, representative for 14 cells from 6 experiments with islets from three donors) β‐cells showing that ex‐9 prevents [cAMP]pm elevations induced by 10 nmol/L glucagon. G, Recording from a MIN6 β‐cell showing that ex‐9 reduces basal [cAMP]pm and prevents the GLP‐1‐induced elevation. Representative for 23 cells from four experiments. H, I, Box plots of the magnitudes of the [cAMP]pm reductions induced by ex‐9 in cells stimulated with GLP‐1 (H) or glucagon (I). P values are given for comparisons of mean values with Student's paired t test

2.2. GLP‐1 and ex‐9 do not affect glucagon receptor signalling whereas glucagon promotes cAMP elevation via GLP‐1 receptors

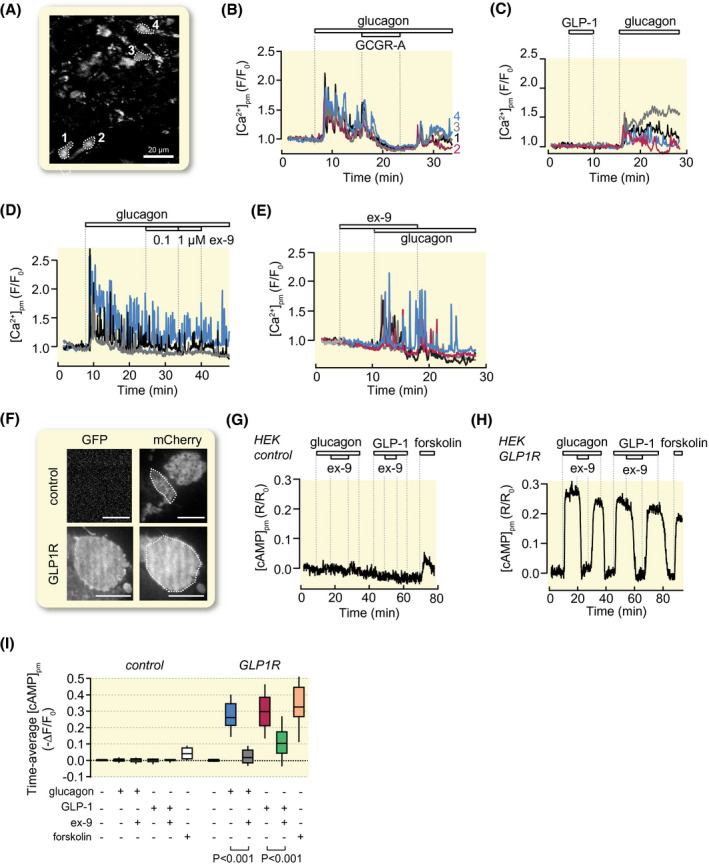

There is a high degree of homology between the GLP‐1 and glucagon receptors and both hormones may activate both receptors. 28 To clarify to what extent GLP‐1 and ex‐9 act on glucagon receptors we took advantage of a reporter cell line that expresses glucagon receptors and G15α, which signals via phospholipase C, thus allowing receptor activation to be monitored as increases in [Ca2+]pm. Some cells exhibited fast [Ca2+]pm oscillations prior to stimulation (not shown) and only cells with low and stable [Ca2+]pm under basal conditions were selected for analyses. While 10 nmol/L glucagon induced prompt increase of [Ca2+]pm with fast oscillations (Figure 2A,B,D), there was no effect of 100 nmol/L GLP‐1 (Figure 2C). The glucagon effect was efficiently reversed by a glucagon receptor antagonist (GCGR‐A; “compound 15” 32 ; Figure 2B), whereas 0.1‐1 µmol/L ex‐9 lacked effect (Figure 2D,E). These data show that GLP‐1 and ex‐9 do not affect glucagon receptors at the concentrations tested. Recordings of [cAMP]pm from HEK293 cells, which lack endogenous glucagon and GLP‐1 receptors, demonstrated that expression of a GFP‐tagged GLP‐1 receptor construct rendered the cells responsive to both glucagon and GLP‐1, and that the hormone‐induced [cAMP]pm increases were inhibited by ex‐9 (Figure 2F‐I). The observation that ex‐9 prevents glucagon‐induced [cAMP]pm elevations in β‐cells therefore indicates that glucagon mainly acts via GLP‐1 receptors in these cells.

FIGURE 2.

GLP‐1 and ex‐9 do not affect glucagon receptor signalling whereas glucagon promotes cAMP production via GLP‐1 receptors. A‐E, Recordings of [Ca2+]pm from single glucagon receptor‐expressing reporter cells loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fluo‐4. A, TIRF image (491/527 nm exc/em) of fluo‐4‐loaded reporter cells. B, Glucagon (10 nmol/L) induces [Ca2+]pm signalling that is reversibly inhibited by 1 µmol/L of glucagon receptor antagonist (GCGR‐A). Representative example traces from the cells highlighted in (A) out of 102 cells in seven experiments. C, GLP‐1 (100 nmol/L) lacks effect while glucagon triggers [Ca2+]pm signalling. Representative for 61 cells from six experiments. D, Ex‐9 fails to reverse [Ca2+]pm signalling evoked by glucagon. Representative for 135 cells from eight experiments. E, Pre‐exposure to 1 µmol/L ex‐9 does not prevent the [Ca2+]pm‐elevating effect of 10 nmol/L glucagon. Representative for 61 cells from 4 experiments. F‐I, Recordings of [cAMP]pm from HEK293 cells expressing GFP‐tagged GLP‐1 receptors. F, TIRF images of HEK293 cells transfected with an mCherry‐based cAMP translocation biosensor together or not with a GFP‐tagged GLP‐1 receptor construct. Scale bar, 10 µm. G, Effects of 10 nmol/L glucagon, 1 µmol/L ex‐9, 10 nmol/L GLP‐1 and 10 µmol/L forskolin on [cAMP]pm in control cells lacking GLP‐1 receptors. Representative for 24 cells from three experiments. H, Similar as in G but with cells expressing GLP‐1 receptors. Representative for 43 cells from three experiments. I, Box plots of the time‐average [cAMP]pm from experiments as shown in G and H. P values are given for the comparison of mean values with Student's paired t test

2.3. GLP‐1 receptors contribute to basal cAMP production and to glucose‐stimulated [cAMP]pm elevation in islets and single β‐cells

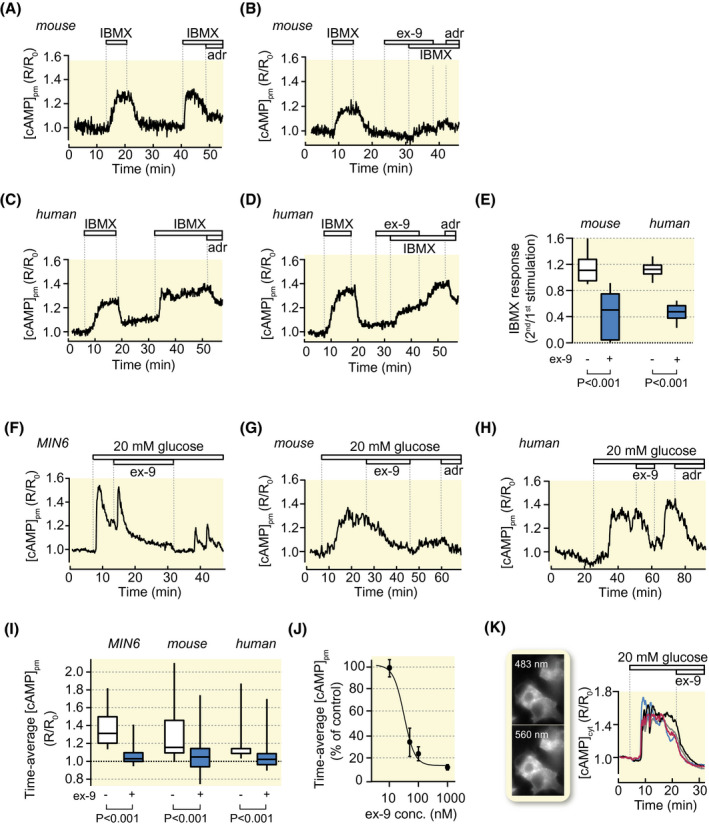

There is high turnover of cAMP in β‐cells and basal cAMP production is balanced by phosphodiesterase‐mediated degradation. Inhibition of phosphodiesterases with IBMX unmasks the basal cAMP formation and increases [cAMP]pm (Figure 3A‐E). Ex‐9 attenuated the effect of IBMX in both mouse and human β‐cells (Figure 3B,D,E) showing that GLP‐1‐receptor signalling contributes to the basal adenylyl cyclase activity.

FIGURE 3.

GLP‐1 receptor antagonism suppresses basal cAMP production and glucose‐induced [cAMP]pm elevations. A, [cAMP]pm recording from a single β‐cell within an intact mouse islet during two consecutive exposures to IBMX. Representative for 27 cells from three experiments. B, As in A but with 1 µmol/L ex‐9 introduced before the second IBMX exposure. Representative for 57 cells in nine experiments. C and D, As in A and B but with human β‐cells. Representative for 28 cells for control and 22 cells with ex‐9, both groups derived from four experiments with islets from a single donor. E, Box plots of the amplitudes of the second IBMX stimulation normalized to the first based on experiments as shown in A‐D. F, [cAMP]pm recording from a single MIN6 β‐cell exposed to an increase of the glucose concentration from 3 to 20 mmol/L. Ex‐9 at 1 µmol/L reversibly suppresses the glucose‐induced [cAMP]pm elevation. Representative for 84 cells from six experiments. G, H, [cAMP]pm recordings from β‐cells within intact mouse (G, representative for 28 cells from 11 experiments) or human islets (H, 24 cells from five experiments with islets from four donors), showing that ex‐9 suppresses the [cAMP]pm increase induced by elevation of glucose from 3 to 20 mmol/L. The lack of effect or lowering of [cAMP]pm in response to 10 µmol/L adrenaline (adr) is used as indication of β‐cell identity. I, Box plots for [cAMP]pm after stimulation with 20 mmol/L glucose and exposure to ex‐9. P values refer to statistical comparisons made with Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. J, Means ± SEM for the effect of different concentrations of ex‐9 on glucose‐induced [cAMP]pm elevation in MIN6 β‐cells. n = 7 to 24 cells for each data point. K, Wide‐field fluorescence microscopy images and recordings of cytoplasmic cAMP from MIN6 cells stimulated by increase of glucose from 3 to 20 mmol/L and subsequently exposed to 100 nmol/L ex‐9. Representative for 63 cells from three experiments

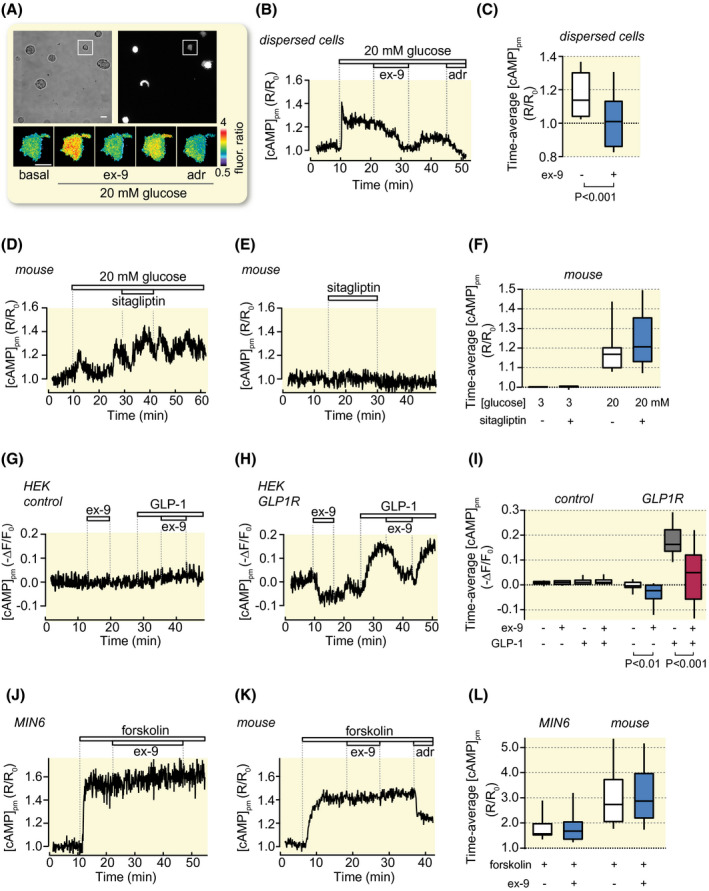

As reported previously, 10 , 12 , 33 high glucose concentrations triggered increases of [cAMP]pm in MIN6 as well as in primary mouse and human β‐cells (Figure 3F‐I). The responses were inhibited by ex‐9 with half‐maximal effect at 32 nmol/L and maximal effect at ~1 µmol/L in MIN6‐cells (Figure 3J). Although the translocation cAMP sensor reports cAMP in the sub‐membrane space, glucose and ex‐9 influenced cAMP globally in the cytoplasm as shown by recordings based on wide‐field imaging and a cytoplasmic FRET cAMP reporter (Figure 3K). To clarify whether the effect of ex‐9 reflected GLP‐1 receptor signalling activated by paracrine secretion of GLP‐1 or glucagon in the islet, the inhibitor was applied to single, dispersed β‐cells superfused with medium containing 20 mmol/L glucose. Like for β‐cells within intact islets, ex‐9 caused a pronounced reduction of the glucose‐induced [cAMP]pm elevation in single cells, sometimes reaching below the baseline (Figure 4A‐C). A potential effect of endogenous GLP‐1 production may be underestimated by the presence of dipeptidylpeptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) on islet cells. 34 , 35 However, 100 nmol/L of the DPP‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin did not enhance [cAMP]pm elevation triggered by either glucose (Figure 4D,F) or GLP‐1 (not shown) and lacked effect on basal [cAMP]pm (Figure 4E,F).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of ex‐9 and sitagliptin on glucose‐, GLP‐1‐ and forskolin‐induced [cAMP]pm signals in dispersed β‐cells, HEK293 cells and β‐cell within intact islets. A, Transmitted light and TIRF images of dispersed mouse β‐cells. The pseudo‐coloured ratiometric [cAMP]pm image sequence shows the effect of an increase of glucose from 3 to 20 mmol/L, 1 µmol/L ex‐9 and 10 µmol/L adrenaline (adr) in the single cell highlighted in the square. B, [cAMP]pm recording from the cell highlighted in (A). Representative for 13 cells from six experiments. C, Box plots of [cAMP]pm in cells exposed to 20 mmol/L glucose and ex‐9 as in (B). The P value refers to comparison of the mean values with Student's t test. D, Effect of 100 nmol/L sitagliptin on [cAMP]pm in a β‐cell within an intact mouse islet stimulated by an increase of the glucose concentration from 3 to 20 mmol/L. Representative for 25 cells from five experiments. E, Lack of effect of 100 nmol/L sitagliptin on [cAMP]pm in a mouse islet β‐cell exposed to 3 mmol/L glucose. Representative for 42 cells from six experiments. F, Box plots of the effects of glucose and sitagliptin in experiments as shown in (D) and (E). G, H, Effects of ex‐9 and GLP‐1 on [cAMP]pm in single HEK293 cells lacking (G) or expressing (H) GLP‐1 receptors. Representative for 21 and 29 cells from three experiments in each group. I, Box plots for the treatments shown in (G) and (H). P values refer to the comparison of mean values using Student's paired t test. J, K, [cAMP]pm recordings from a single MIN6 β‐cell (J; Representative for 18 cells from three experiments) or a mouse islet β‐cell (K; Representative for 47 cells from three experiments) showing that 1 µmol/L ex‐9 lacks effect on [cAMP]pm elevations induced by 10 µmol/L forskolin. L, Box plots of the effects of forskolin and ex‐9 on [cAMP]pm in experiments as in (J) and (K)

2.4. The GLP‐1 receptor shows agonist‐independent activity

To elucidate if there is constitutive activity of the GLP‐1 receptor, the GFP‐tagged receptor was expressed in HEK293 cells, which completely lack paracrine signalling from glucagon or GLP‐1. Recordings of [cAMP]pm showed that control cells did not respond to either ex‐9 or GLP‐1 (Figure 4G,I). However, in GLP‐1‐receptor‐expressing cells, ex‐9 reversibly lowered [cAMP]pm below the base‐line (Figure 4H,I). This observation indicates that the GLP‐1 receptor is constitutively active in the absence of ligand. The receptor‐expressing cells readily responded to GLP‐1 with [cAMP]pm elevation, an effect that was counteracted by the antagonist. In contrast to the effect in hormone‐ and glucose‐stimulated cells, ex‐9 did not reduce [cAMP]pm in MIN6 cells stimulated with the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (Figure 4J‐L) demonstrating that the drug does not exert an unspecific inhibition of cAMP formation.

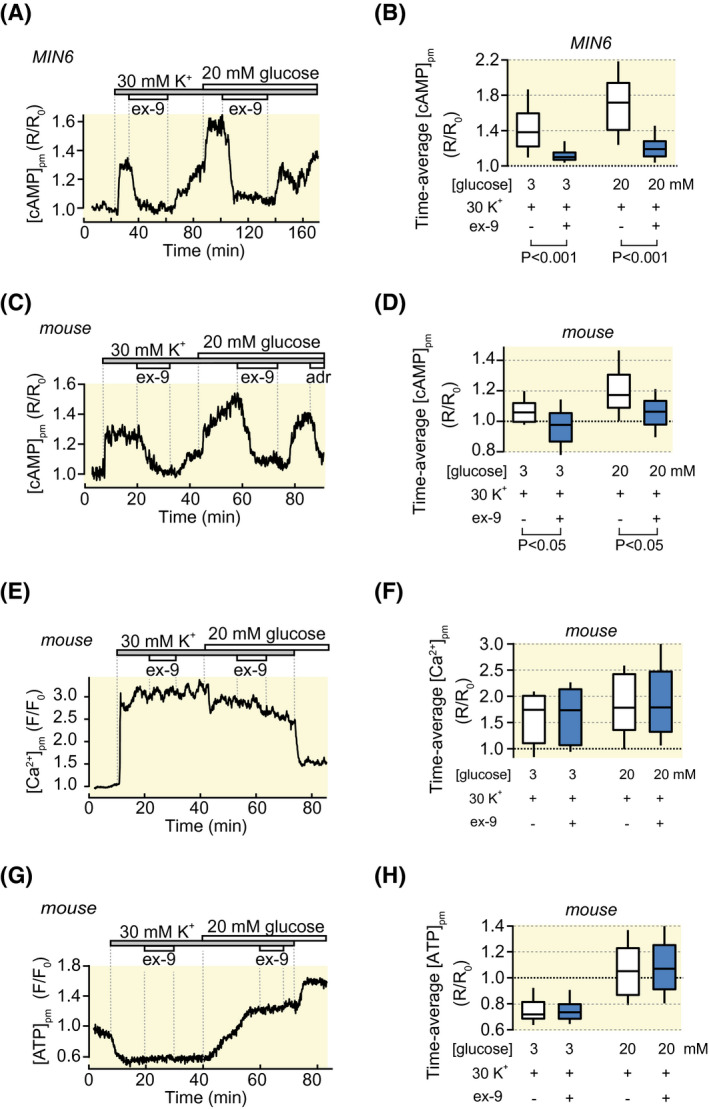

2.5. Ca2+‐stimulated cAMP formation involves GLP‐1 receptor activity

Depolarization of MIN6 cells with 30 mmol/L K+ in the presence of the KATP‐channel opener diazoxide triggered [cAMP]pm elevation, probably by activating Ca2+‐sensitive adenylyl cyclases, 13 , 16 , 17 and this effect was inhibited by ex‐9 (Figure 5A,B). Increasing the glucose concentration from 3 to 20 mmol/L augmented the Ca2+‐triggered [cAMP]pm elevation, an effect that reflects stimulation of cAMP formation by cell metabolism, 10 , 24 and ex‐9 reduced [cAMP]pm also under this condition (Figure 5A,B). Similar findings were made in primary mouse β‐cells (Figure 5C,D). The effects of the GLP‐1 receptor inhibitor on [cAMP]pm were not paralleled by alterations in [Ca2+]pm (Figure 5E,F). It was also tested if ex‐9 influenced cell metabolism. Recordings of [ATP]pm with the fluorescent reporter Perceval showed no effect of ex‐9 but reduction of [ATP]pm in response to K+ depolarization and increase with high glucose (Figure 5G,H), in line with previous reports. 36 , 37

FIGURE 5.

Ex‐9 suppresses Ca2+‐stimulated [cAMP]pm increases. A, [cAMP]pm recording from a single MIN6 β‐cell showing that 1 µmol/L ex‐9 suppresses [cAMP]pm increases induced by depolarization and glucose stimulation in the continuous presence of 250 µmol/L diazoxide. Representative for 95 cells from five experiments. B, Box plots showing the effects of high K+, glucose and ex‐9 on [cAMP]pm. P values refer to statistical comparisons made with Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. C, Similar as in (A) but for mouse islet β‐cells. The [cAMP]pm ‐lowering effect of 10 µmol/L adrenaline (adr) is used to verify the identity of islet β‐cells. Representative for 10 cells from five experiments. D, Box plots showing the effects of high K+, glucose and ex‐9 on [cAMP]pm. P values are given for comparisons of mean values with Student's paired t test. E, [Ca2+]pm recording from a single β‐cell within an intact mouse islet showing that ex‐9 lacks effect on depolarization‐induced [Ca2+]pm increases in the presence of diazoxide and 3 or 20 mmol/L glucose as in (C). Representative for 30 cells from eight experiments. F, Box plot for the effects of K+, glucose and ex‐9 on [Ca2+]pm. G, Recording of [ATP]pm under similar conditions as in (E). Representative for 42 cells from three experiments. H, Box plots showing the effects of K+, glucose and ex‐9 on [ATP]pm

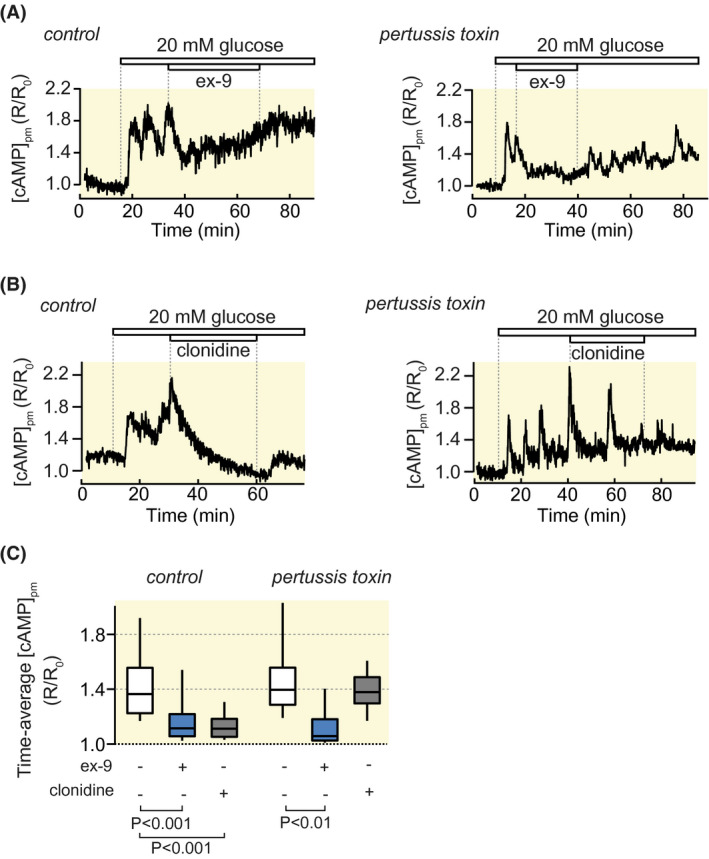

2.6. The [cAMP]pm‐lowering effect of ex‐9 does not involve activation of Giα

Since cAMP‐lowering agonists often act on receptors coupled to the inhibitory G‐protein Giα we checked whether the effects of ex‐9 might be explained by such a mechanism. To this end, MIN6‐cells were treated with 200 ng mL−1 pertussis toxin for 18 hours prior to the [cAMP]pm imaging experiments. This treatment did not inhibit the effect of ex‐9 (Figure 6A,C), while completely preventing Giα‐mediated [cAMP]pm reduction by the α2‐adrenergic agonist clonidine (Figure 6B,C).

FIGURE 6.

The [cAMP]pm‐lowering effect of ex‐9 does not involve activation of Giα. [cAMP]pm recordings from single MIN6 β‐cells pre‐treated or not with pertussis toxin. A, Pertussis toxin does not prevent 1 µmol/L ex‐9 from suppressing the [cAMP]pm increase induced by elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 20 mmol/L. Representative for 25 cells from four experiments in the control and 54 cells from eight experiments in the pertussis‐toxin‐treated group. B, Pertussis toxin prevents the suppression of glucose‐induced [cAMP]pm elevation by 100 nmol/L clonidine. Representative for 23 cells from 3 experiments in the control and 20 cells from three experiments with pertussis toxin treatment. C, Box plots showing the effects of glucose, ex‐9 and clonidine on [cAMP]pm. P values refer to statistical comparisons made with Wilcoxon singed‐rank test

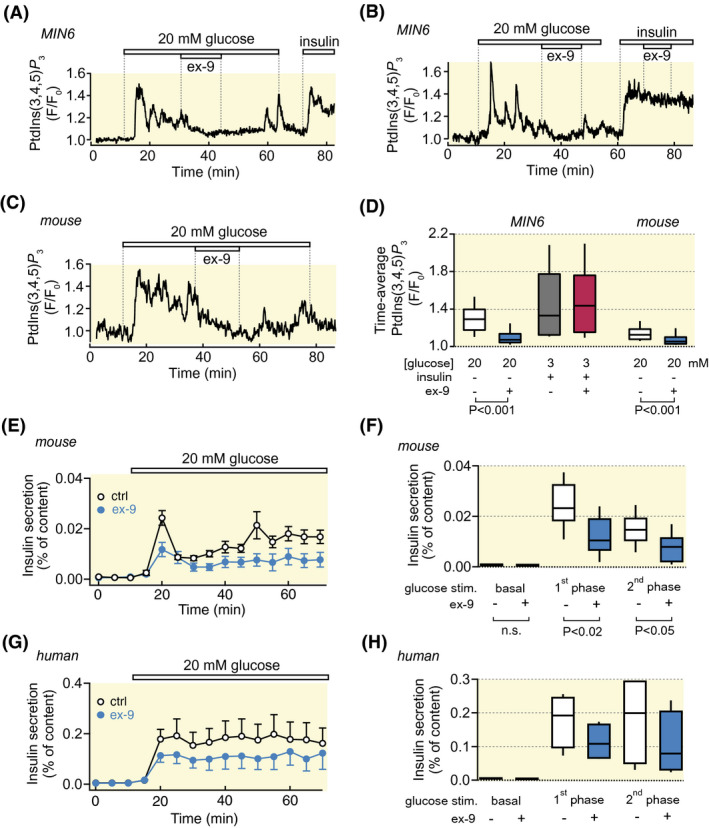

2.7. Ex‐9‐induced reduction of [cAMP]pm suppresses insulin secretion

Insulin secretion dynamics from single β‐cells was monitored by recording the autocrine effect of insulin on the plasma membrane concentration of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5‐trisphosphate ([Ptdlns(3,4,5)P 3]pm). 10 , 33 MIN6‐cells responded to glucose stimulation with prompt [Ptdlns(3,4,5)P 3]pm elevation followed by oscillations reflecting pulsatile insulin secretion (Figure 7A,B). This response was suppressed by ex‐9 in a reversible manner. Addition of 100 nmol/L exogenous insulin caused stable [Ptdlns(3,4,5)P 3]pm elevation, which was unaffected by ex‐9, indicating that the GLP‐1‐receptor antagonist did not interfere with insulin receptor signalling (Figure 7B,D). Ex‐9 also reversed glucose‐elevated [Ptdlns(3,4,5)P 3]pm in primary β‐cells within intact mouse islets (Figure 7C,D). Similar results were obtained when insulin release was measured from perifused mouse islets using conventional ELISA. In islets exposed to 1 µmol/L ex‐9, both first and second phase glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion was reduced by approximately 50% compared to control (Figure 7E,F; P < .2‐.05; n = 9 and 7 for control and ex‐9 respectively). In four experiments with human islets, glucose‐stimulated secretion was reduced by 42%, but this effect did not reach statistical significance, probably because of the low number of observations (Figure 7G,H).

FIGURE 7.

Ex‐9 perturbs insulin secretion dynamics. A, Recording of insulin secretion from a single MIN6 β‐cell with a fluorescent PtdIns(3,4,5)P 3 biosensor. Ex‐9 (1 µmol/L) reversibly suppresses the PtdIns(3,4,5)P 3 response induced by increase of the glucose concentration from 3 to 20 mmol/L. Insulin (100 nmol/L) is added at the end of the experiment as a positive control. Representative for 71 cells from 10 experiments. B, Similar experiment as in (A) showing that ex‐9 does not affect insulin‐triggered PtdIns(3,4,5)P 3 elevation. Representative for 31 cells from 6 experiments. C, PtdIns(3,4,5)P 3 recording as in (A), but from a β‐cell within an intact mouse islet. Representative for 51 cells from 6 experiments. D, Box plots showing the effects of glucose, ex‐9 and insulin on the time‐average PtdIns(3,4,5)P 3 responses. P values refer to statistical comparisons made with Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. E, Means ± SEM for insulin secretion from perifused mouse islets stimulated by an increase in glucose concentration from 3 to 20 mmol/L in the absence or presence of 1 µmol/L ex‐9. F, Box plots showing the effect of ex‐9 on insulin secretion at 3 mmol/L glucose (basal), at 5‐10 min after stimulation with 20 mmol/L (1st phase) and at 20‐60 min stimulation with 20 mmol/L glucose (2nd phase). N = 9 (control) and 7 (ex‐9) independent experiments. P values refer to statistical comparisons made with Mann‐Whitney U‐test. G‐H, As in E‐F, but with human islets. N = 4 experiments with islets from 3 donors for both control and ex‐9

3. DISCUSSION

The present study focused on the mechanisms underlying cAMP generation in pancreatic β‐cells and reinforces the role of GLP‐1 receptors for both glucose‐ and glucagon‐induced cAMP signalling. It is not surprising that the GLP‐1 receptor antagonist ex‐9, a truncated form of the GLP‐1‐receptor agonist exendin‐4 from Heloderma suspectum venom, 38 completely reversed [cAMP]pm elevations induced by GLP‐1, but the peptide turned out to be equally efficient in counteracting the effects of glucagon. It has been demonstrated that glucagon may activate β‐cell GLP‐1 receptors, 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 but patch‐clamp studies in mouse β‐cells have shown that ex‐9 inhibits the effects of GLP‐1 but not those of glucagon on exocytosis, suggesting that the two hormones act via different receptors. 39 Our data support that ex‐9 fails to interfere with glucagon receptor signalling, but indicate that GLP‐1 receptors in islets are more promiscuous.

The observation that ex‐9 suppressed IBMX‐ and glucose‐induced [cAMP]pm signalling in mouse and human islets in the absence of exogenously added GLP‐1 or glucagon may reflect paracrine signalling from endogenous glucagon. This conclusion mirrors early observations that such activation of hormone receptors is critical for the glucose competence of β‐cells, 26 , 40 , 41 a concept that has been reinforced in more recent studies. 27 , 29 , 30 Although GLP‐1 has been reported to be produced in α‐cells, 42 , 43 release of the bioactive hormone from these cells is very low 29 and it seems more likely that glucagon accounts for the GLP‐1 receptor activation. In addition, there seems to be activity in the GLP‐1 receptor also in the complete absence of agonist. There are divergent opinions about constitutive activity of the GLP‐1 receptors. Agonist‐independent activity have previously been reported, 44 but most studies have failed to observe such an effect. 45 In the present study, ex‐9 lowered [cAMP]pm in single, dispersed islet cells, when paracrine influences would be minimal because of the dilution of any endogenous glucagon in the superfusion medium. Moreover, ex‐9 lowered basal [cAMP]pm in HEK293 cells after heterologous expression of the GLP‐1 receptor, an observation that cannot be explained by the presence of glucagon or glucagon‐related peptides in the preparation. The conclusion that there is constitutive signalling in the GLP‐1 receptor in the absence of ligand is in line with the suggestion that ex‐9 acts as an inverse agonist. 46 The peptide has been found to reduce glucose‐induced insulin secretion and cAMP production in normal mouse islets, 31 amino‐acid‐induced insulin secretion and cAMP content in SUR1−/− islets, 47 as well as basal cAMP production in rat islets. 28 The present data are consistent with these findings and extend the conclusions to human β‐cells.

It is well‐established that increases of [Ca2+]pm in β‐cells stimulate cAMP formation, 10 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 22 , 48 probably as a result of Ca2+/calmodulin activation of the adenylyl cyclases AC1 and AC8. 49 It has also been demonstrated that cell metabolism may directly stimulate cAMP formation, 10 a concept that has obtained support by mathematical modelling. 24 These two parallel mechanisms for cAMP formation were discriminated using a protocol which depolarizes the β‐cell with a high K+ concentration in the presence of diazoxide to evoke an increase of [Ca2+]pm, followed by increase of the glucose concentration to stimulate metabolism. The KATP channel activator prevents glucose from changing the membrane potential and increase [Ca2+]pm. GLP‐1 receptor antagonism not only suppressed glucose‐stimulated cAMP formation, but also that triggered by voltage‐dependent Ca2+ entry was strongly impaired by pharmacological GLP‐1 receptor antagonism. The effect on [cAMP]pm was not due to ex‐9 influencing [Ca2+]pm or [ATP]pm, and it therefore seems that Ca2+/calmodulin stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity is facilitated by Gsα activity.

We also showed that ex‐9 did not directly inhibit adenylyl cyclases, as it lacked effect on forskolin‐stimulated cAMP generation. Moreover the possibility that the [cAMP]pm‐lowering effect was mediated by activation of the inhibitory G‐protein Giα could be excluded, since pertussis toxin failed to prevent the ex‐9‐induced [cAMP]pm lowering while completely abrogating the inhibitory effect of clonidine.

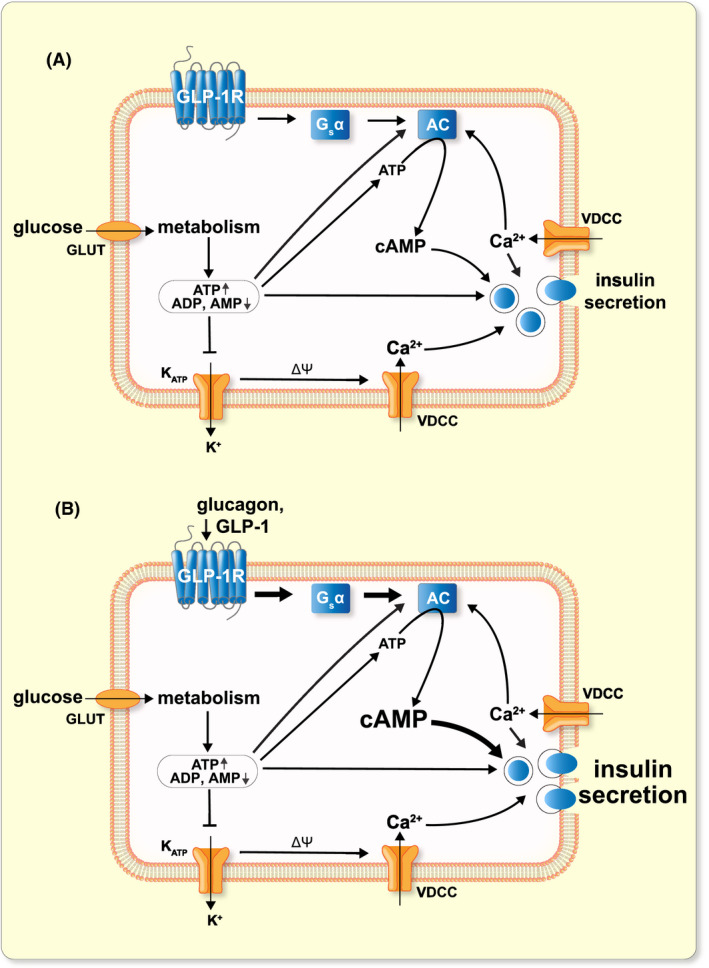

The present study leads to the conclusion that glucose‐induced cAMP production in β‐cells involves amplification of constitutive and glucagon‐activated signalling through the GLP‐1 receptor and that this mechanism is critical for glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion (Figure 8). Glucose metabolism promotes cAMP formation by stimulating adenylyl cyclase activity directly by increasing availability of the substrate ATP and/or by decreasing the concentration of inhibitory AMP. Increases of [Ca2+]pm also contribute to the elevation of [cAMP]pm. Glucagon or GLP‐1 agonism on the GLP‐1 receptor leads to enhanced cAMP formation and insulin secretion and inhibition of receptor signalling accordingly leads to reduced cAMP formation and impaired insulin secretion without effect on the exocytosis‐triggering [Ca2+]pm signal. Incretin hormone effects are impaired in type 2 diabetes 50 and stimulation of GLP‐1 receptor signalling is established as a successful therapeutic approach. 51 , 52 Reduced cAMP formation and cAMP‐secretion coupling in β‐cells have been reported in animal and in vitro models of the disease. 33 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 Future studies will elucidate to what extent lower inherent GLP‐1 receptor signalling contributes to impaired β‐cell function in diabetes.

FIGURE 8.

Proposed model for glucose‐ and hormone‐induced cAMP formation in β‐cells. A, Constitutive signalling from the GLP‐1 receptor (in the absence of ligand) via Gsα and adenylyl cyclases (AC) contributes to glucose‐induced cAMP formation and insulin secretion. Glucose metabolism results in increases of ATP and reductions of ADP and AMP. The change in nucleotide concentrations promotes AC activity by multiple mechanisms and cAMP enhances Ca2+‐triggered exocytosis. See text for details. Glucose metabolism triggers insulin secretion via KATP channel closure, membrane depolarization and influx of Ca2+ through voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCC). B, Activation of GLP‐1 receptors by glucagon or GLP‐1 stimulates Gsα and AC activity and the increased cAMP production leads to amplification of insulin secretion

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Materials

Adrenaline, HEPES, 2‐mercaptoethanol, poly‐L‐lysine, 3‐isobutyl‐1‐methylxanthine (IBMX), GLP‐1‐(7‐36)‐amide and glucagon were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (Stockholm, Sweden). DMEM, Lipofectamine 2000, trypsin, penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine, fluo‐4‐AM and fetal calf serum were from Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Exendin‐(9‐39) was purchased from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Pertussis toxin was from Tocris (Bristol, UK). The glucagon receptor inhibitor “compound 15” 32 was a kind gift from Novo‐Nordisk. A plasmid encoding the GFP‐tagged GLP‐1 receptor was obtained from Prof Sebastian Barg, Uppsala, University. Plasmid or adenoviral vectors containing the two moieties of a cAMP translocation biosensor were generated as previously described. 10 , 48 The biosensor encodes a truncated and membrane‐anchored PKA regulatory RIIβ subunit tagged with CFP and a PKA catalytic Cα subunit tagged with YFP. An alternative version of the sensor lacking fluorescence tag on the RIIβ subunit and with an mCherry tag on the Cα subunit was used for the experiments in Figure 2F‐I and Figure 4G‐I. A plasmid encoding GRP1 (general receptor for phophoinositides‐1) fused to 4 tandem copies of (GFP4‐GRP1) was used to detect plasma membrane PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels, which reflect insulin secretion with concomitant autocrine activation of insulin receptors and PI3‐kinase. 10 An adenovirus‐expressing Perceval was used for ATP recordings. 36 Glucagon‐receptor‐expressing Chem‐1 reporter cells (Ready‐to‐Assay, HTS112RTA) were obtained from Merck Millipore (Solna, Stockholm, Sweden).

4.2. MIN6‐cell culture and transfection

Insulin‐secreting MIN6‐cells (passages 17‐30) 57 were cultured in DMEM with 25 mmol/L glucose and supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, 2 mmol/L l‐glutamine, 50 µmol/L 2‐mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified air atmosphere. For imaging experiments, cells were seeded on poly‐l‐lysine‐coated 25‐mm coverslips. For each coverslip, 0.2 million cells were suspended in Optimen I medium (Invitrogen) containing 0.5 µL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and 0.2 to 0.4 µg of the cAMP or Ptdlns(3,4,5)P3 biosensor plasmids and placed onto the centre of the coverslip. After 4 hours, when the cells were firmly attached, the transfection was interrupted by adding 3 mL complete cell culture medium. Cells were maintained in this medium for 24 to 48 hours.

4.3. Islet isolation and virus transduction

Islets of Langerhans were collagenase‐isolated from 6‐ to 9‐month‐old, normal‐weight C57B16J female mice. The mice were housed in ventilated cages (up to 5 animals/cage) with a 12 hours dark/light cycle and with free access to water and a standard mouse chow. All procedures for animal handling and islet isolation were approved by Uppsala animal ethics committee. After isolation, the islets were cultured for 1 to 2 days in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5.5 mmol/L glucose, 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U mL−1 penicillin and 100 µg mL−1 streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified air atmosphere. Human islets from eleven normoglycemic cadaveric organ donors (Table 1) were obtained via the Nordic Network for Clinical Islet Transplantation in Uppsala. All experiments with human islets were approved by the Uppsala human ethics committee. The isolated islets were cultured up to 7 days at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in CMRL 1066 culture medium containing 5.5 mmol/L glucose, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mmol/L glutamine and 10% FBS. The islets or cells were infected 1 to 2 hours with cAMP or Ptdlns(3,4,5)P3 biosensor adenoviruses at a concentration of 105 fluorescence forming units per islet, and this was followed by washing and further culture for 16‐20 hours before use.

TABLE 1.

Human islet donor characteristics

| Islet preparation | Sex |

Age y |

BMI kg/m2 |

HbA1c mmol/mol (%) |

Related experiments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1848 | Male | 58 | 21.4 | unknown | Figure 3F |

| H1922 | Male | 55 | 25.8 | 36.6 (5.5) | Figure 3F |

| H2088 | Male | 68 | 25.6 | 39.9 (5.8) | Figures 1C and 3F |

| H2089 | Male | 30 | 26 | 34.4 (5.3) | Figures 1C and 3F |

| H2154 | Male | 66 | 24.3 | 38.8 (5.7) | Figure 1F |

| H2164 | Male | 67 | 24.6 | 34.4 (5.3) | Figure 1F |

| H2176 | Female | 64 | 25.7 | 37.7 (5.6) | Figure 1F |

| H2325 | Female | 71 | 30.8 | Unknown | Figure 3C and 3D |

| H2512 | Female | 56 | 24.6 | 40.0 (5.8) | Figure 7G,H |

| H2516 | Male | 55 | 22.4 | 36.0 (5.4) | Figure 7G,H |

| H2517 | Female | 51 | 28.1 | 35.0 (5.4) | Figure 7G,H |

4.4. Recordings of cAMP, Ca2+, ATP and Ptdlns(3,4,5)P3

Changes of the cAMP, Ca2+ and ATP concentrations in the sub‐plasma membrane space ([cAMP]pm, [Ca2+]pm and [ATP]pm) and of the plasma membrane concentration of the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol‐3,4,5‐trisphophate ([Ptdlns(3,4,5)P3]pm) were recorded with total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Before imaging, the cells or islets were pre‐incubated for 30 minutes in experimental buffer containing in mM: NaCl 125, KCl 4.8, CaCl2 1.3, MgCl2 1.2 and HEPES 25 with pH adjusted to 7.40 with NaOH. For [Ca2+]pm measurements, the cells were loaded with 1.3 µmol/L of the acetoxymethyl ester of the Ca2+ indicator Fluo‐4 by 30 minutes of incubation at 37°C in experimental buffer. After the incubation, the islets were attached to poly‐lysine‐coated 25‐mm coverslips. β‐cells were identified on the basis of their large size and negative [cAMP]pm response to adrenaline, in contrast to alpha cells with small footprints and adrenaline‐induced [cAMP]pm elevation. 12

TIRF imaging was performed using a custom‐built prism‐based setup or an objective‐based system as previously described. 23 Diode‐pumped solid‐state lasers (Cobolt, Solna, Sweden) provided excitation light for Fluo‐4 (491 nm) and the fluorescent protein biosensors (445, 491 and 514 nm for CFP, GFP/Perceval and YFP, respectively). Emission wavelengths were selected with filters [485 nm/25 nm half‐bandwidth for CFP, 527/27 nm for GFP/Perceval and 560/40 nm for YFP (Semrock Rochester, NY)] mounted in a filter wheel (Sutter Instruments). Fluorescence was detected with back‐illuminated EMCCD cameras (DU‐897, Andor Technology) under MetaFluor (Molecular Devices Corp, Downington, PA) software control. For time‐lapse recordings, images or image pairs were acquired every 5 seconds. For the experiment in Figure 3K, the cells were transfected with the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)‐based cAMP reporter EpacSH188; Ref.58 The reporter was excited at 445 nm in the objective‐based TIRF system with the laser angle set for wide‐field illumination. Donor emission was recorded at 483 and sensitized emission from the acceptor at 560 nm. The data are presented as the 483/560 nm fluorescence emission ratio (“FRET ratio”) normalized to the prestimulatory level.

4.5. Measurements of insulin secretion

Groups of 15‐16 islets were placed in a 10‐µl teflon tube chamber and perifused at a rate of 60 µL/min using a pressurized air system (AutoMate Scientific, Berkeley, CA, USA) and equilibrated in experimental buffer containing 3 mmol/L glucose with or without 1 µmol/L ex‐9 during 45 minutes. The perifusate was subsequently collected in 5‐min fractions into ice‐chilled 96‐well plates with a non‐binding‐surface (Corning Inc Kennebunk, ME) while changing the glucose concentration to 20 mmol/L in the absence or continued presence of ex‐9. The islets were retrieved and briefly sonicated in acid ethanol to determine insulin content. Insulin concentrations in the samples were determined with ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

4.6. Data analysis

Image analysis was performed with MetaFluor. The cAMP concentration was expressed as the ratio of CFP over YFP fluorescence or as the relative changes of mCherry fluorescence (experiments in Figures 2G‐I and 4G‐I) after subtraction of the background and normalization to the prestimulatory level. For other fluorescent reporters, changes in fluorescence intensity were normalized to the initial fluorescence intensity after subtraction of background. Curve fitting was carried out using IGOR Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) software. If not otherwise stated, all experiments were performed with at least three independent islet isolations or preparations of cells. Data are presented as box plots and statistical analyses were made with Student's t test, Wilcoxon signed‐rank test or Mann‐Whitney U test as appropriate.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HS designed and performed all TIRF imaging experiments and analysed data. YX contributed widefield imaging experiments and PA immunoassay experiments. AT conceived the study, designed experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (325‐2012‐6778, 2017‐00956), the Swedish Diabetes Foundation, Diabetes Wellness Foundation, Family Ernfors Foundation, European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes/MSD, Novo‐Nordisk Foundation, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Swedish Child Diabetes Foundation and the Swedish national strategic grant initiative EXODIAB (Excellence of diabetes research in Sweden). Human islets were generously provided by the Nordic Network for Clinical Islet transplantation supported by EXODIAB and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Shuai H, Xu Y, Ahooghalandari P, Tengholm A. Glucose‐induced cAMP elevation in β‐cells involves amplification of constitutive and glucagon‐activated GLP‐1 receptor signalling. Acta Physiol. 2021;231:e13611. 10.1111/apha.13611

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kahn SE, Cooper ME, Del Prato S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1068‐1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campbell JE, Drucker DJ. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab. 2013;17(6):819‐837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prentki M, Matschinsky FM, Madiraju SR. Metabolic signaling in fuel‐induced insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 2013;18(2):162‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rorsman P, Ashcroft FM. Pancreatic β‐cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: Of mice and men. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(1):117‐214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Henquin JC. Regulation of insulin secretion: a matter of phase control and amplitude modulation. Diabetologia. 2009;52(5):739‐751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tengholm A, Gylfe E. cAMP signalling in insulin and glucagon secretion. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(Suppl 1):42‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moens K, Heimberg H, Flamez D, et al. Expression and functional activity of glucagon, glucagon‐like peptide I, and glucose‐dependent insulinotropic peptide receptors in rat pancreatic islet cells. Diabetes. 1996;45(2):257‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grill V, Cerasi E. Activation by glucose of adenyl cyclase in pancreatic islets of the rat. FEBS Lett. 1973;33(3):311‐314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hellman B, Idahl LÅ, Lernmark Å, Täljedal IB. The pancreatic β‐cell recognition of insulin secretagogues: does cyclic AMP mediate the effect of glucose? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3405–3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dyachok O, Idevall‐Hagren O, Sågetorp J, et al. Glucose‐induced cyclic AMP oscillations regulate pulsatile insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 2008;8(1):26‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim JW, Roberts CD, Berg SA, Caicedo A, Roper SD, Chaudhari N. Imaging cyclic AMP changes in pancreatic islets of transgenic reporter mice. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):e2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tian G, Sandler S, Gylfe E, Tengholm A. Glucose‐ and hormone‐induced cAMP oscillations in α‐ and β‐cells within intact pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2011;60:1535‐1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dou H, Wang C, Wu X, et al. Calcium influx activates adenylyl cyclase 8 for sustained insulin secretion in rat pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2015;58(2):324‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Charles MA, Lawecki J, Pictet R, Grodsky GM. Insulin secretion. Interrelationships of glucose, cyclic adenosine 3:5‐monophosphate, and calcium. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(15):6134‐6140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharp GW, Wiedenkeller DE, Kaelin D, Siegel EG, Wollheim CB. Stimulation of adenylate cyclase by Ca2+ and calmodulin in rat islets of langerhans: explanation for the glucose‐induced increase in cyclic AMP levels. Diabetes. 1980;29(1):74‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Delmeire D, Flamez D, Hinke SA, Cali JJ, Pipeleers D, Schuit F. Type VIII adenylyl cyclase in rat beta cells: coincidence signal detector/generator for glucose and GLP‐1. Diabetologia. 2003;46(10):1383‐1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raoux M, Vacher P, Papin J, et al. Multilevel control of glucose homeostasis by adenylyl cyclase 8. Diabetologia. 2015;58(4):749‐757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leech CA, Castonguay MA, Habener JF. Expression of adenylyl cyclase subtypes in pancreatic β‐cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1999;254(3):703‐706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tengholm A. Cyclic AMP dynamics in the pancreatic β‐cell. Upsala J Med Sci. 2012;117(4):355‐369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pyne NJ, Furman BL. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases in pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2003;46(9):1179‐1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Han P, Werber J, Surana M, Fleischer N, Michaeli T. The calcium/calmodulin‐dependent phosphodiesterase PDE1C down‐regulates glucose‐induced insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22337‐22344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landa LR Jr, Harbeck M, Kaihara K, et al. Interplay of Ca2+ and cAMP signaling in the insulin‐secreting MIN6 β‐cell line. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(35):31294‐31302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tian G, Sågetorp J, Xu Y, Shuai H, Degerman E, Tengholm A. Role of phosphodiesterases in the shaping of sub‐plasma‐membrane cAMP oscillations and pulsatile insulin secretion. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 21):5084‐5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peercy BE, Sherman AS, Bertram R. Modeling of glucose‐induced cAMP oscillations in pancreatic β cells: cAMP rocks when metabolism rolls. Biophys J. 2015;109(2):439‐449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson RA, Yeung SM, Stubner D, Bushfield M, Shoshani I. Cation and structural requirements for P site‐mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;35(5):681‐688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schuit FC, Pipeleers DG. Regulation of adenosine 3',5' monophosphate levels in the pancreatic B cell. Endocrinology. 1985;117:834‐840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Capozzi ME, Svendsen B, Encisco SE, et al. β‐Cell tone is defined by proglucagon peptides through cyclic AMP signaling. JCI Insight. 2019;4(5):e126742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moens K, Flamez D, Van Schravendijk C, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Schuit F. Dual glucagon recognition by pancreatic β‐cells via glucagon and glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptors. Diabetes. 1998;47(1):66‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Svendsen B, Larsen O, Gabe MBN, et al. Insulin secretion depends on intra‐islet glucagon signaling. Cell Rep. 2018;25(5):1127‐1134 e1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu L, Dattaroy D, Pham J, et al. Intra‐islet glucagon signaling is critical for maintaining glucose homeostasis. JCI Insight. 2019;4(10):e127994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flamez D, Gilon P, Moens K, et al. Altered cAMP and Ca2+ signaling in mouse pancreatic islets with glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor null phenotype. Diabetes. 1999;48(10):1979‐1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kodra JT, Jørgensen AS, Andersen B, et al. Novel glucagon receptor antagonists with improved selectivity over the glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor. J Med Chem. 2008;51(17):5387‐5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tian G, Sol ER, Xu Y, Shuai H, Tengholm A. Impaired cAMP generation contributes to defective glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion after long‐term exposure to palmitate. Diabetes. 2015;64(3):904‐915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Omar BA, Liehua L, Yamada Y, Seino Y, Marchetti P, Ahren B. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP‐4) is expressed in mouse and human islets and its activity is decreased in human islets from individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2014;57(9):1876‐1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Augstein P, Naselli G, Loudovaris T, et al. Localization of dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (CD26) to human pancreatic ducts and islet alpha cells. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;110(3):291‐300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li J, Shuai HY, Gylfe E, Tengholm A. Oscillations of sub‐membrane ATP in glucose‐stimulated beta cells depend on negative feedback from Ca2+ . Diabetologia. 2013;56(7):1577‐1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Merrins MJ, Poudel C, McKenna JP, et al. Phase Analysis of Metabolic Oscillations and Membrane Potential in Pancreatic Islet β‐Cells. Biophys J. 2016;110(3):691‐699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eng J, Kleinman WA, Singh L, Singh G, Raufman JP. Isolation and characterization of exendin‐4, an exendin‐3 analogue, from Heloderma suspectum venom. Further evidence for an exendin receptor on dispersed acini from guinea pig pancreas. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(11):7402‐7405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gromada J, Ding WG, Barg S, Renström E, Rorsman P. Multisite regulation of insulin secretion by cAMP‐increasing agonists: evidence that glucagon‐like peptide 1 and glucagon act via distinct receptors. Pflügers Archiv Eur J Physiol. 1997;434(5):515‐524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pipeleers DG, Schuit FC, In’tveld PA, et al. Interplay of nutrients and hormones in the regulation of insulin release. Endocrinology. 1985;117(3):824‐833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Holz GG, Kühtreiber WM, Habener JF. Pancreatic beta‐cells are rendered glucose‐competent by the insulinotropic hormone glucagon‐like peptide‐1(7–37). Nature. 1993;361(6410):362‐365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marchetti P, Lupi R, Bugliani M, et al. A local glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) system in human pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2012;55(12):3262‐3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Masur K, Tibaduiza EC, Chen C, Ligon B, Beinborn M. Basal receptor activation by locally produced glucagon‐like peptide‐1 contributes to maintaining beta‐cell function. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(5):1373‐1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Al‐Sabah S, Al‐Fulaij M, Shaaban G, et al. The GIP receptor displays higher basal activity than the GLP‐1 receptor but does not recruit GRK2 or arrestin3 effectively. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen G, Jayawickreme C, Way J, et al. Constitutive receptor systems for drug discovery. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1999;42(4):199‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Serre V, Dolci W, Schaerer E, et al. Exendin‐(9–39) is an inverse agonist of the murine glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor: implications for basal intracellular cyclic adenosine 3',5'‐monophosphate levels and β‐cell glucose competence. Endocrinology. 1998;139(11):4448‐4454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. De Leon DD, Li C, Delson MI, Matschinsky FM, Stanley CA, Stoffers DA. Exendin‐(9–39) corrects fasting hypoglycemia in SUR‐1‐/‐ mice by lowering cAMP in pancreatic beta‐cells and inhibiting insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(38):25786‐25793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dyachok O, Isakov Y, Sågetorp J, Tengholm A. Oscillations of cyclic AMP in hormone‐stimulated insulin‐secreting β‐cells. Nature. 2006;439(7074):349‐352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Willoughby D, Cooper DM. Organization and Ca2+ regulation of adenylyl cyclases in cAMP microdomains. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):965‐1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nauck M, Stockmann F, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W. Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non‐insulin‐dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia. 1986;29(1):46‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lovshin JA, Drucker DJ. Incretin‐based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(5):262‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ahrén B. Islet G protein‐coupled receptors as potential targets for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2009;8(5):369‐385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rabinovitch A, Renold AE, Cerasi E. Decreased cyclic AMP and insulin responses to glucose in pancreatic islets of diabetic Chinese hamsters. Diabetologia. 1976;12(6):581‐587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dachicourt N, Serradas P, Giroix MH, Gangnerau MN, Portha B. Decreased glucose‐induced cAMP and insulin release in islets of diabetic rats: reversal by IBMX, glucagon, GIP. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(4 Pt 1):E725‐E732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dolz M, Movassat J, Bailbe D, et al. cAMP‐secretion coupling is impaired in diabetic GK/Par rat beta‐cells: a defect counteracted by GLP‐1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301(5):E797‐E806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Abdel‐Halim SM, Guenifi A, Khan A, et al. Impaired coupling of glucose signal to the exocytotic machinery in diabetic GK rats: a defect ameliorated by cAMP. Diabetes. 1996;45(7):934‐940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Miyazaki J, Araki K, Yamato E, et al. Establishment of a pancreatic β cell line that retains glucose‐inducible insulin secretion: special reference to expression of glucose transporter isoforms. Endocrinology. 1990;127(1):126‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Klarenbeek J, Goedhart J, van Batenburg A, Groenewald D, Jalink K. Fourth‐generation epac‐based FRET sensors for cAMP feature exceptional brightness, photostability and dynamic range: characterization of dedicated sensors for FLIM, for ratiometry and with high affinity. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.