Abstract

Coccidioidomycosis is a systemic fungal infection first described in 1892. More than 95% of annual cases occur in Arizona and California. It is an opportunistic infection (OI) transmitted via inhalation of airborne spores (arthroconidia) and rarely via percutaneous inoculation into a tissue or solid organ transplantation in patients who are immunocompromised and with HIV. With the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART), the incidence of OIs has markedly reduced; however, OIs continue to occur, particularly in patients who present late for medical care or delay ART initiation. In rare cases, immunodeficient individuals may experience a paradoxical worsening or unmasking of OI symptoms, known as the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). We present a case of a 31-year-old man with disseminated coccidioidomycosis affecting the spleen, lymph nodes, lungs, bone marrow, and adrenals who developed IRIS after the initiation of ART.

Keywords: infections, immunology, HIV / AIDS

Background

Our case is unique as the patient presented with right lower lobe infiltrate and was treated as community-acquired pneumonia initially; however, later it was found that the patient had coccidioidomycosis and had moved from an endemic area. The patient also developed immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) when he was initiated with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Only four cases have been reported in patients with coccidioidomycosis in whom initiating ART resulted in IRIS.

Case presentation

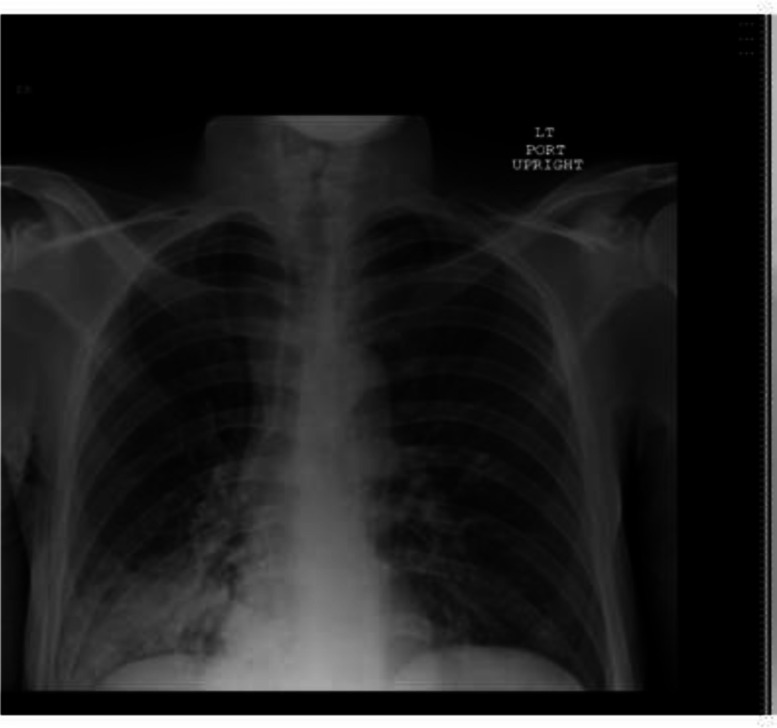

A 31-year-old man with a medical history of AIDS, non-compliant with ART, presented with a cough, low-grade fever and chills of 1-week duration. He denied night sweats or haemoptysis. The patient moved from El Paso (Texas) to the Washington, DC area 9 years prior to admission. He was afebrile on presentation, blood pressure was 100/62 mm Hg and the rest of the vital signs were stable. Physical examination was remarkable for decreased air entry and rales over the right lower lung lobe. Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count 5.6×109/L, haemoglobin 120 g/L and platelets 264 ×109/L. Chest X-ray (figure 1) showed large right lower lobe infiltrates and early consolidation. The CD4 count was 120 cells/mm3 and HIV RNA level was 5 290 000 copies/mL. Arterial blood gas showed no hypoxia and normal A-a gradient (alveolar-arterial gradient).

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray showing large right lower lobe infiltrate.

He was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia, initiated on appropriate antibiotics and placed on ART and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. The patient completed the antibiotics; however, he started to have fever and hypotension and continued to have a cough. Blood pressure dropped to 70s/50s, and was unresponsive to intravenous fluids. Early morning serum cortisol was obtained, which was low at 2.8 µg/dL. The patient was started on hydrocortisone; however, blood pressure remained low. He also developed pancytopenia with white blood cell count as low as 1×109/L, haemoglobin as low as 55 g/L and platelets 29 ×109/L. A repeat chest X-ray showed persistent right lobe infiltrates. CT scan of the chest without contrast was obtained and showed mediastinal, bilateral axillary, supraclavicular, abdominal periaortic lymphadenopathy, marked hepatosplenomegaly, pericardial effusion and small bilateral pleural effusions (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

CT of the chest revealing pericardial effusion, and right-sided infiltrates.

Figure 3.

CT of the abdomen revealing periaortic lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.

Since the infiltrates were persistent and the patient was having recurrent fevers, bronchoscopy was done. Bronchoalveolar lavage was negative for bacteria, Pneumocystis pneumonia (Pneumocystis jirovecii) and acid fast bacilli. Viral markers for Epstein barr virus, Parvovirus B19, Cytomegalo virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C were negative. Markers for histoplasma, that is, urine histoplasma, histoplasma capsulatum (yeast and mycelial) by compliment fixation, and blastomycosis antigen were negative. Serum coccidiosis antibody titre by complement fixation was 1:64 (normal range <1:2, titres exceeding 1:16 usually indicates disseminated disease).

Oral fluconazole 400 mg daily was started, and 2 weeks later, the blood pressure started to improve. The patient was subsequently discharged on fluconazole and hydrocortisone, with follow-up appointments with pulmonary and infectious diseases clinics. The patient was continued on fluconazole for 12 weeks. Five weeks later patient was restarted on ART.

Outcomes and follow-up

Three months later, repeat chest X-ray showed improved infiltrate (figure 4). CT of the abdomen revealed that hepatosplenomegaly had improved. CD4 count improved to 364 cells/mm3, viral load decreased to 370 copies/mL; pancytopenia improved with haemoglobin 110 g/L and platelets 148 ×109/L.

Figure 4.

Repeat X-ray showing resolution of infiltrates.

Discussion

Coccidioides spp is a dimorphic fungus having two subspecies, C. immitis and C. posadasii. Infection occurs on inhalation of arthroconidia which germinate into spherules that later rupture to release endospores. The overall annual incidence increasing from 5.3 cases per 100 000 in 1998 to 42.6 cases per 100 000 in 2011. The estimated numbers of infections per year have risen to ∼150 000 because of increase in population in southern Arizona and central California.1 2 About two-thirds of these infections are subclinical. The most common clinical manifestation of coccidioidomycosis is a self-limited acute or subacute community-acquired pneumonia that usually presents 1–4 weeks after infection. As evident in our case, such illnesses cannot be distinguished from bacterial infections without specific laboratory tests, such as fungal cultures or coccidioidal serological testing.1

Dissemination occurs only in less than 1% of the patients via the lymphatic and haematogenous route and manifests with systemic symptoms such as fever, cough and night sweats. Immunosuppression and race are predictors of dissemination with individuals of African-American and Filipino descents at increased risk of disseminated disease.1 3 4 Our patient was an African-American and had AIDS that put him at increased risk of dissemination.

Our differential diagnosis was extensive with mycobacterial infection and malignancy at the top of our list. We initially did not order serum coccidioidal antigen test because the patient has not been in an endemic area for about 9 years. By definition, at some point, the patient may have experienced a primary infection after exposure to fungal spores in the endemic area followed by dissemination. Reactivation of an infection leading to dissemination can occur years later after the primary infection.5 In our case, the patient may have been exposed to the organism in Texas about 9 years ago when he used to live there. As evident by pan-CT above, pancytopenia, adrenal insufficiency and positive serology, our patient had a disseminated infection. Such presentation usually requires tissue examination but we avoided it because of markedly low platelet count and deranged coagulation profile.

Patients with advanced immunosuppression are at significant risk of IRIS, if concomitant ART is started along with antifungal treatment, which is an exaggerated inflammatory response usually directed toward microbial antigens. The pathogenesis of IRIS is not well-defined, but it is thought that CD4 recovery with ART leads to the responses that generate an inflammatory reaction. A low CD4 count and high viral load before initiation have been associated with higher risk of developing IRIS.6 7 There are only a few case reports who have described coccidioidal infection during the early phase of immune reconstitution after initiation of ART.6 8 9 Consensus definition has been established by experts for IRIS related to HIV infections. The definition of coccidioidal IRIS requires the following criteria (1) a pre-existing or new diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis, (2) an increase in CD4 count or a decrease in HIV RNA or both, (3) worsening of symptoms after initiating ART, (4) improvement in symptoms by antifungal therapy and (5) the absence of an alternative diagnosis to explain the symptoms.6 8 Our patient’s clinical condition deteriorated after the initiation of ART, even though there was an increase in CD4 count and a decrease in viral load. Later, the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis was confirmed by serological testing and there was a marked improvement in the symptoms when antifungal therapy was started. However, we believe that the severity of IRIS symptoms was masked by the hydrocortisone started for adrenal insufficiency in our patient.

To prevent IRIS-related mortality and morbidity in patients with cryptococcal infection, studies have demonstrated that it is important to wait to complete 5 weeks of antifungal treatment prior to initiating ART.8 10 11 The delay in initiating ART has been shown to decrease IRIS-associated mortality.8 10 The 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis states that initiation of ART should not be delayed due to the concern about coccidioidal IRIS.10 However, there have been coccidioidal IRIS cases reported, which have shown significant mortality and morbidity due to IRIS.8 Our patient responded very well to fluconazole while being on hydrocortisone, so we continued our patient on ART on discharge.

Learning points.

In patients who are immunocompromised, and from an endemic area of coccidioidomycosis, high index of suspicion is required to diagnose coccidioidomycosis, which in turn can reduce the morbidity, mortality and length of hospital stay.

Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis can present with lung infiltrates, pleural effusion and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

The definition of coccidioidal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome requires the following criteria (1) a pre-existing or new diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis, (2) an increase in CD4 count or a decrease in HIV RNA or both, (3) worsening of symptoms after initiating antiretroviral therapy, (4) improvement in symptoms by antifungal therapy and (5) the absence of an alternative diagnosis to explain the symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Hadeel Abdalla MD and Jhansi Gajalla MD.

Footnotes

Contributors: AD reviewed and updated the case report. HY wrote the abstract and discussion. MMM wrote the case and discussion. OS wrote the conclusion and contributed in collecting collateral information.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. Coccidioidomycosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2005;41:1217–23. 10.1086/496991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. TsangCA, TabnakF, VugiaDJ, et al. Increase in reported coccidioidomycosis--United States, 1998-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:217–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McConnell MF, Shi A, Lasco TM, et al. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis with multifocal musculoskeletal disease involvement. Radiol Case Rep 2017;12:141–5. 10.1016/j.radcr.2016.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odio CD, Marciano BE, Galgiani JN, et al. Risk factors for disseminated coccidioidomycosis, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23. 10.3201/eid2302.160505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galgiani JN. Coccidioidomycosis: a regional disease of national importance. rethinking approaches for control. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:293–300. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4-199902160-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mu A, Shein TT, Jayachandran P, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients with AIDS and disseminated coccidioidomycosis: a case series and review of the literature. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2017;16:540–5. 10.1177/2325957417729751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ, et al. AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses in US patients, 1994-2007: a cohort study. AIDS 2010;24:1549–59. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a3967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddow LJ, Easterbrook PJ, Mosam A, et al. Defining immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: evaluation of expert opinion versus 2 case definitions in a South African cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009;49:1424–32. 10.1086/630208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ampel NM. Coccidioidomycosis among persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Semin Respir Infect 2001;16:257–62. 10.1053/srin.2001.29301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. 2016 infectious diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:e112–46. 10.1093/cid/ciw360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lofgren S, Abassi M, Rhein J, et al. Recent advances in AIDS-related cryptococcal meningitis treatment with an emphasis on resource limited settings. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2017;15:331–40. 10.1080/14787210.2017.1285697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]