Abstract

The current management of persistent biliary fistula includes biliary stenting and peritoneal drainage. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is preferred over percutaneous techniques and surgery. However, in patients with modified gastric anatomy, ERCP may not be feasible without added morbidity. We describe a 37-year-old woman with traumatic biliary fistula, large volume choleperitonitis and abdominal compartment syndrome following a motor vehicle collision who was treated with laparoscopic drainage, lavage and biliary drain placement via percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography.

Keywords: general surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, biliary intervention

Background

Major bile leaks following high-grade blunt hepatic trauma present in 0.5%–21% of cases.1–6 Current data suggest a global prevalence of 2.8%–7.4% in all patients sustaining blunt hepatic injuries.3 7 The majority occur with grades III–V hepatic injury, at a rate of 23.9%.3 7 Biliary injuries usually resolve spontaneously if they are small but may present as biliary fistula or choleperitonitis if inadequately drained.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is commonly used in the treatment of biliary fistula or choleperitonitis. In patients who have had Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the traditional ERCP procedure becomes complicated due to the Roux-en-Y anatomy, and various other techniques are used in these patients. However, there is no current literature regarding the treatment of choleperitonitis in patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

In this case report, we present a patient with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass who underwent laparoscopic drainage and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) with biliary drain placement for choleperitonitis.

Case presentation

A 37-year-old woman with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, bipolar disorder, anaemia, cholecystectomy and caesarean section presented after a high-speed motor vehicle collision. In the emergency department her primary survey was unimpressive, and she had symptoms of abdominal and lower extremity pain. She was found to have multiple injuries including a grade II liver laceration through segments IVA and IVB without active extravasation (see table 1, figure 1).

Table 1.

Patientinjuries on presentation

| Injuries | |

| Grade II liver laceration through segments IVA/IVB without active extravasation | Haemoperitoneum |

| Left ankle fracture | Left fibular fracture |

| Right calcaneal fracture | Right tibial-fibular fracture |

| Fractures of right ribs 1–7 | Fractures of left ribs 2–3 |

| Peri-splenic haematoma | Right adrenal haematoma |

| Right pelvic haematoma | |

Figure 1.

Initial CT on presentation demonstrating liver laceration.

The patient was admitted to an intermediate care unit for close monitoring, including daily complete blood count, basic metabolic panel and liver function testing. On hospital day 2, she underwent open reductions and internal fixations of her lower extremity fractures. Over the next week, she remained in the hospital requiring significant intravenous analgesia. She developed abdominal distention and obstipation. She was given an aggressive bowel regimen with minimal effect. She was determined to have clinical and radiographic ileus, which was believed to be paralytic ileus following trauma.

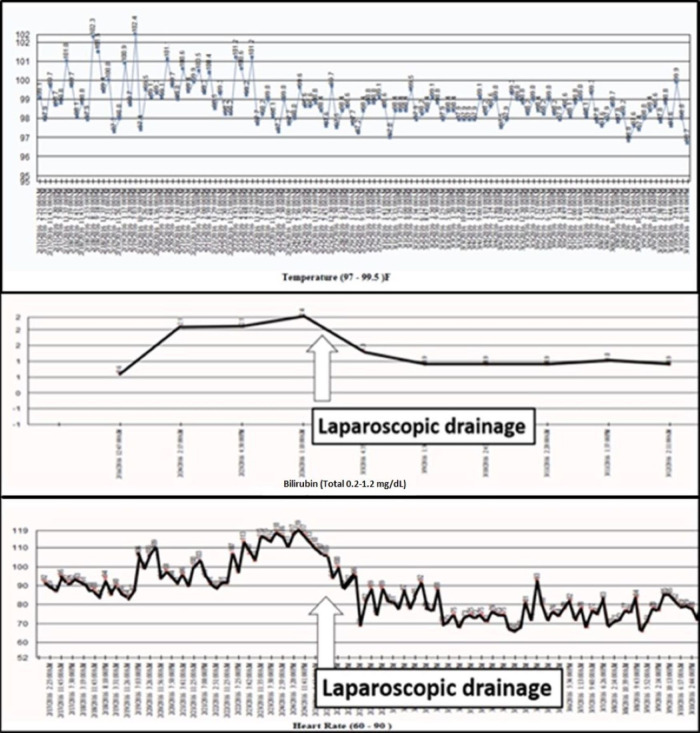

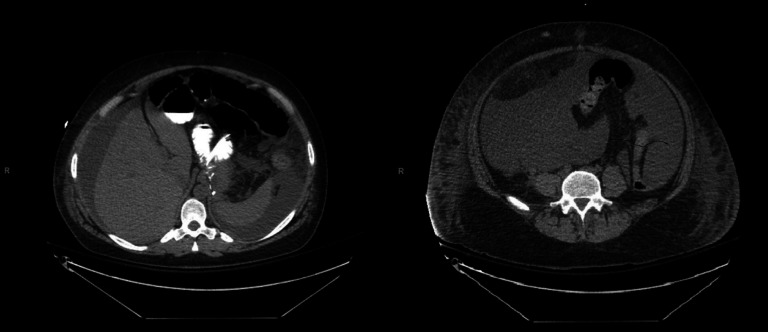

On hospital day 7, the patient became fatigued, febrile (up to 102.4°F, see figure 2), tachycardic, dyspnoeic and mounted a leucocytosis, hyperbilirubinaemia (2.1 mg/dL, see figure 2), along with worsening abdominal distension. A workup including chest X-ray, urine cultures, blood cultures and eventually an abdominal CT scan was performed. A repeat CT scan had not been ordered earlier due to the attribution of the patient’s worsening distension to paralytic ileus. CT scan identified a significant amount of low density intra-abdominal free fluid (see figure 3), which we believed was due to delayed accumulation of bile from a leak sustained at the time of injury.

Figure 2.

Patient temperature, heart rate and bilirubin before and after laparoscopic drainage.

Figure 3.

CT images from hospital day 7 demonstrating significant intra-abdominal free fluid.

Treatment

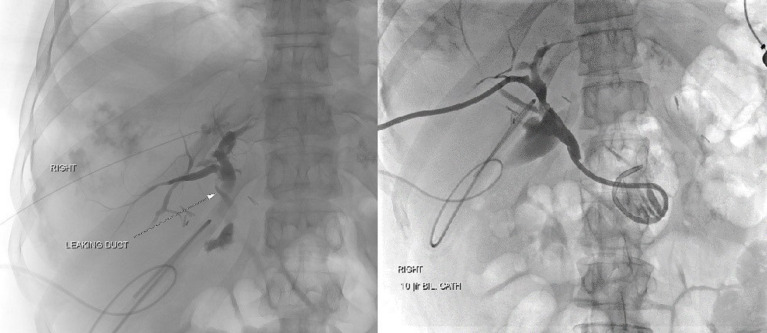

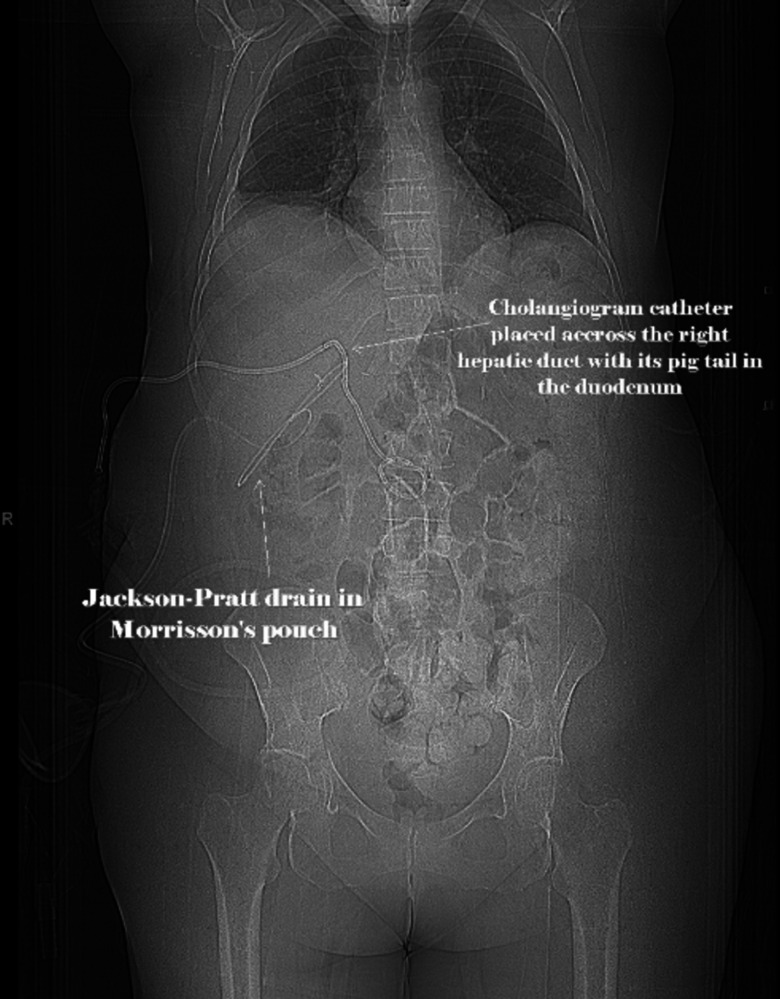

Given the CT findings, her symptoms, fevers (up to 102.4°F, see figure 2), tachycardia, dyspnoea, leucocytosis, suspicion for abdominal hypertension, worsening abdominal distension and hyperbilirubinaemia (2.1 mg/dL, see figure 2), an urgent operative drainage of the suspected choleperitonitis was decided on. A diagnostic laparoscopy with irrigation and drainage of 7 L of bile was done on hospital day 12. On entering the abdomen all four quadrants were inspected. The gallbladder was surgically absent, but clips were present and intact in the gallbladder fossa. Precise injury to the liver was not identified. One #19 French Blake drain was left in the subhepatic recess and another in the recto-uterine pouch. The patient defervesced, and her symptoms improved. However, drain output was persistently elevated, between 500 and 700 mL of bilious drainage daily. An ERCP with laparoscopic access to her Roux limb was considered but determined to be high risk. Instead, she underwent PTC with identification of a right hepatic duct leak and placement of a biliary drain across the right duct into the duodenum (see figures 4 and 5). Subsequently, her surgical drain output decreased to less than 100 mL/day. On hospital day 23, the PTC drain was clamped (internalised), and on hospital day 25, the pelvic drain was removed. The next day she developed fever with gram positive rods in the drain and was started on meropenem. The antibiotics were stopped after 5 days, and the PTC drain was unclamped.

Figure 4.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography images showing isolation of bile leak and catheter placement.

Figure 5.

Radiographic image showing the leak and the placement of cholangiogram catheter and Jackson-Pratt drain post-percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged afebrile with her drain clamped 30 days after admission. She tolerated clamping for a month and the PTC drain was removed in the office after a total of 6 weeks. The patient is currently doing well.

Discussion

Traumatic bile duct injury is an uncommon occurrence in blunt trauma but may lead to the development of biliary fistula or choleperitonitis. Traumatic bile duct injury may be associated with delayed bile leak, which can also be due to bile duct ischemia or subcapsular collections.8 Kozar et al proposed that most bile duct injuries can be treated with PTC or ERCP and stenting, except for choleperitonitis with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) physiology, which should be evaluated with laparoscopy and drainage.9 Many studies have now supported ERCP and intrabiliary stent placement across the ampulla of Vater as preferred management of traumatic and iatrogenic biliary fistulas in an otherwise stable patient with or without sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater.1 5 10 However, in patients with modified gastric anatomy these ERCP procedures may not be plausible.

In the Roux-en-Y population, various techniques have been implemented in non-traumatic pathology of the biliary tree, including double balloon enteroscope-assisted ERCP, laparoscopic-assisted transgastric ERCP (LAERCP), or open biliary surgery. Likewise, PTC has been used successfully in multiple different settings of non-traumatic bile duct pathology.

In patients who develop stone-related complications after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, endoscopic access to the biliary tree is technically challenging due to anatomic rearrangements.11 In one case, a Roux-en-Y patient with common bile duct stones was managed with PTC with sphincter dilation and internal–external drain placement.12 Two large studies have evaluated PTC in removal of common bile duct stones in patients who failed traditional ERCP management: Ozcan et al reported a 100% success rate of stone removal in 37 patients while Lee et al reported a 95.7% success rate and 6.8% complication rate in 261 patients, with cholangitis and subscapular biloma as common complications.10 13 Additionally, Borel et al demonstrated the use of laparoscopic transgastric ERCP for successful treatment of biliary lithiasis in a patient post-gastric bypass procedure.14

A newer approach for patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy includes EUS-directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE) with the deployment of a lumen-apposing metal stent. This technique allows for the completion of an ERCP in patients with the modified anatomy through the creation of a fistula between the gastric pouch and the remnant stomach.15 LAERCP has also shown utility for common bile duct clearance in the Roux-en-Y population. LAERCP involves the creation of a gastrostomy in the gastric remnant. An ERCP is then performed through a purse string or port followed by intraoperative gastrotomy closure or Stamm gastrostomy if subsequent procedures, such as stent removal, are anticipated.16

In the case of our patient, both LAERCP and EDGE would have been successful treatment options. LAERCP has been performed sporadically for common bile duct stone removal in our institution based on the availability of a qualified endoscopist. LAERCP would have been useful for assessment and stenting of the common bile duct in our patient and could have been done at the time of the initial laparoscopic drainage. However, we did not possess the expertise for that specific method or for EDGE at the time. Thus, PTC was chosen over these validated treatment options, despite the risk of complications, such as infection, as it was the only procedure available for use.

An important consideration following traumatic bile duct injury is the identification of delayed bile leaks. We believe that our patient’s bile leak began at the time of liver injury but was not identified until hospital day 7 due to the onset of symptoms. Although literature regarding delayed bile leak following traumatic liver injury is sparse, a case report by Al-Hassani et al described the use of ERCP to treat a biloma as a result of delayed bile leak in a patient with normal gastric anatomy.8 This patient’s bile leak was also identified 1 week following initial injury on repeat imaging.8 Due to the delayed presentation, studies have suggested repeating imaging in high-grade liver injuries between days 7 and 10 to assess for delayed bile leak or other complications.8

Various techniques are available to assess the biliary tree. However, PTC may prove useful in cases of traumatic biliary fistula when transoral ERCP is not possible, such as patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy as in the case of our patient.

Learning points.

Biliary tract injuries are uncommon but may present with biliary fistula or choleperitonitis if inadequately drained.

Modified gastric anatomy complicates the typical endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedure used in the treatment of choleperitonitis.

Laparoscopy and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage may be possible treatment options for choleperitonitis, specifically in patients with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM, JM and MT contributed to the writing of this case report. MM, OO and MT edited this case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Anand RJ, Ferrada PA, Darwin PE, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is an effective treatment for bile leak after severe liver trauma. J Trauma 2011;71:480–5. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181efc270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asensio JA, Demetriades D, Chahwan S, et al. Approach to the management of complex hepatic injuries. J Trauma 2000;48:66. 10.1097/00005373-200001000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bala M, Gazalla SA, Faroja M, et al. Complications of high grade liver injuries: management and outcomewith focus on bile leaks. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012;20:20. 10.1186/1757-7241-20-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrillo EH, Spain DA, Wohltmann CD, et al. Interventional techniques are useful adjuncts in nonoperative management of hepatic injuries. J Trauma 1999;46:619–24. 10.1097/00005373-199904000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castagnetti M, Houben C, Patel S, et al. Minimally invasive management of bile leaks after blunt liver trauma in children. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41:1539–44. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh V, Narasimhan KL, Verma GR, et al. Endoscopic management of traumatic hepatobiliary injuries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:1205–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollands MJ, Little JM. Post-Traumatic bile fistulae. J Trauma 1991;31:117–20. 10.1097/00005373-199101000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Hassani A, Jabbour G, ElLabib M, et al. Delayed bile leak in a patient with grade IV blunt liver trauma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;14:156–9. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozar RA, Moore JB, Niles SE, et al. Complications of nonoperative management of high-grade blunt hepatic injuries. J Trauma 2005;59:1066–71. 10.1097/01.ta.0000188937.75879.ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozcan N, Kahriman G, Mavili E. Percutaneous transhepatic removal of bile duct stones: results of 261 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012;35:621–7. 10.1007/s00270-011-0190-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chahine E, Kassir R, Chouillard E. How to manage bile duct injury in patients with duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14:428–30. 10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milella M, Alfa-Wali M, Leuratti L, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography for choledocholithiasis after laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5:249–52. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Kim HW, Kang DH, et al. Usefulness of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy for removal of difficult common bile duct stones. Clin Endosc 2013;46:65. 10.5946/ce.2013.46.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borel F, Branche J, Baud G, et al. Management of acute gallstone cholangitis after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with laparoscopic transgastric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Obes Surg 2019;29:747–8. 10.1007/s11695-018-3620-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyberg A, Kedia P, Tawadros A, et al. EUS-Directed transgastric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (edge): the first learning curve. J Clin Gastroenterol 2020;54:569–72. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habenicht Yancey K, McCormack LK, McNatt SS, et al. Laparoscopic-Assisted transgastric ERCP: a single-institution experience. J Obes 2018;2018:1–4. 10.1155/2018/8275965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]