Abstract

Coal fueled the Industrial Revolution and the global expansion of electrification in the 20th century. In the 21st century, coal use has declined in North America and Europe, but continues to increase in Asia. Coal contains many of the elements of the Periodic Table, in percent-levels or in trace amounts (ppm, ppb). The impact of many of these elements on the environment via air and water discharges from coal-fired plants has been studied with decades of research on their chemical transformations within combustion systems and on their fates upon reintroduction into the environment. The transformations of the trace elements present in coal burned during combustion can be categorized as thermal volatilizations from the coal in the furnace; thermal decomposition of trace element compounds inside the coal; encapsulation inside ash structures through high-temperature vitrification; oxidation of the trace elements with the myriad species contained in flue gas through gas phase (homogeneous) reactions or catalytic (gas-solid) reactions; adsorption and/or reactions with active sites on entrained fly ash particulates contained in the flue gas; and absorption into solutions. These transformations can, in many cases, impact the fraction of these trace elements that are removed by various pollution control devices compared to the fraction released into the environment. The sampling and measurement of trace elements, in the inlet coal, outlet flue gas, aqueous scrubber solutions, and ash matrices, represents a significant challenge. This review focuses on the behavior of trace elements in industrial coal combustion systems with an emphasis on what has been learned over the past century uniquely related to the use of coal in boilers for electricity and heat production. Key accomplishments in measurement, modeling and control of trace element emissions in coal-fired systems are highlighted.

Keywords: Coal, combustion, trace elements, fly ash, mercury, air pollution, coal combustion residuals, rare earth elements

Introduction

Coal’s Importance in World Energy Usage

Coal has powered the world’s industries for centuries, but at a cost: coal contains many elements that affect human health and the health of ecosystems. Over the last 40 years, global coal usage has increased, especially since the beginning of the 21st century, when rising industrial activity in Asia doubled global coal consumption relative to the end of the 20th century. At the same time, coal consumption in Europe, North America, and the former Soviet republics decreased [1]. With current stated policies, coal consumption world-wide is forecast to be flat for the next 10 years and then rising after 2030 through 2050. However, there is the potential for significant reductions if more sustainable policies are adopted, particularly in the Asian countries which are forecast to drive the mid-century increase in consumption [2].

Coal is primarily used for the generation of electricity and commercial heat, with important quantities also used for the production of chemicals, tars, steel, and activated carbons. In 2017, 66.5% of coal worldwide was used for heating and electricity generation, while in the 37 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the proportion was higher at 82.3%. The global share of heat and power generated from coal has held steady at about 40% over the last 40 years, although the share of electricity and heat produced from coal in OECD countries has continued to decrease to 25% in 2018 because of factors such as low-cost natural gas, decreases in the costs for wind and solar electricity generation, and government policies supportive of renewable energy [3].

Coal contains elements, including trace elements (TEs), that affect human health and the health of ecosystems, if released to the environment in specific forms. Knowledge of the impact of TEs released during coal use grew tremendously during the 20th century.

The Impacts of Trace Elements from Coal Combustion on the Environment and Human Health

On a mass basis, the major air pollutants emitted from coal combustion are sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NO + NO2 or NOx), and particulate matter (PM), all of which affect human health and the health of ecosystems. When coal is burned, the vast majority of TEs are typically collected in the ash by particulate control systems and isolated from the environment. However, TEs are also emitted to the air (as well as discharged to water bodies) in both the gas phase and as part of the emitted PM. These emissions are typically much smaller in relation to the major pollutants. Nonetheless, the impact of TEs on human health and ecosystems can be significant [4, 5]. Furthermore, care must be taken to adequately isolate and store the collected ash or use it in ways that minimize the migration of toxic elements to the environment.

Very early references to the significance of TEs in coal can be found around the turn of the 20th century when coal was used for drying of certain ingredients, like malted barley, used in beer-making. Arsenic could be volatilized from the coal and subsequently condense on the malt [6]. This led to methods for quantifying the arsenic concentration in coals [7]. Arsenic and other TEs have also long been of concern in the domestic use of coal. For much of the 20th century, coal was used for household cooking and heating with impacts on human health, for example, as documented with respect to Chinese households [4,8,9].

In the 1960s, deposition of mercury from the atmosphere was linked to increases in mercury concentration in aquatic environments and in fish [10]. Anthropogenic releases were suspected as important contributors to mercury in the environment because of the large amount of coal burned for electricity production and other industrial purposes [11]. Billings and Matson [12] were among the first researchers to directly measure gaseous emissions of mercury from a coal-fired power plant. They concluded that 90% of the mercury input to the 700 MWe power plant which they sampled was emitted from the stack to the air. In addition to mercury, other TEs, including radionuclides, were identified as having the potential to impact human and ecological health [13].

Evidence of the impact of TEs from coal combustion on the environment accumulated in the 1960s and 1970s. Measurements were made of certain TEs in air emissions from coal-fired plants [12, 14-17]. More ambitious projects attempted to determine the mass balances of TEs in plants, considering the composition of coal and ash, air emissions, and water discharges [18-24]. Determination of mass balances allowed consideration of the partitioning of TEs among various phases in coal-fired power plants. These efforts have led to a growing understanding of the importance of coal type, minor element concentration, and combustion conditions upon the partitioning of TEs between solid and gaseous phases and upon the mobility of TEs from particles when released to the environment.

Numerous studies document the TE content of size-segregated fly ash starting in the 1970s. In one of the earliest, Natusch and co-workers [14] analyzed size-segregated fly ash samples collected from the particulate control devices and the stacks of coal-fired power plants. For certain trace elements (i.e. As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb, Sb, Se, Tl, Zn), the concentration in the fly ash increased with decreasing particle size.

Particles in the range 0.1-1 micron in diameter (i.e., submicron particles) are captured less efficiently than larger particles by particulate control devices [15, 25-27]. These transition-range particles have neither the inertia nor the high diffusivities for efficient removal by impaction or diffusion. It has also been shown that, due to their low settling velocities, the residence time of submicron particles in atmospheric aerosol (ca. 100 h) is an order of magnitude longer than for supermicron particles (10–100 h) [28]. These particles will eventually settle out onto the ground or other surfaces downwind of the combustor. Once deposited, ground moisture and rainfall may dissolve soluble TE-containing compounds out of the ash and carry it into the soil. These compounds may then be adsorbed into plants through roots in the soil, percolate downwards to the water table, or runoff into rivers and lakes. The solubility will depend primarily upon the pH of the soil where the particles deposit, rather than the pH of the ash itself [29,30].

Very small submicron particles (<0.1 micron in diameter), known as the submicron fume or as ultrafine particles, have a very low mass emission but higher number concentrations. However, the residence time of ultrafine particles in an atmosphere aerosol is even longer (ca. 1000 hours) [28]. These particles may present a greater risk of inhalation in human and animal respiratory systems [14,31,32] as they may be deposited more deeply in the lungs if inhaled, and offer large surface area to volume ratios. Mumford and Lewtas reported on the mutagenicity and cytotoxicity of coal fly ash [33]. Gilmour et al. demonstrated that fine (< 2.5 microns) and ultrafine (defined in their study as <0.2 micron) fractions of fly ash from coal combustion generated more pulmonary inflammation in mice than bulk (also known as coarse, >2.5 micron) particles, and that for a subbituminous coal, the ultrafine PM was more toxic than the fine PM [34]. A 2018 modeling study explored the impacts of air quality changes for 20 states in the USA if EPA relaxed air pollution standards for coal-fired power plants from those that were in effect in 2018 to those that were in effect in 2007 [35]. The study concluded that this change would raise atmospheric levels of PM that is less than 2.5 microns in diameter (PM2.5) by 1 to 5 μg/m3 and cause additional premature mortalities in the range of 17-to 39 thousand per year.

Regulation and control of TE air emissions have required increased knowledge of the chemistry of TEs in coal combustion systems and air pollution control devices. Unique chemistry occurs in these systems because of the conditions and/or other elements present in coal combustion systems that would not be present in other systems. The emission of TEs into the air from coal-fired power plants is not the only pathway of concern, although air emissions have received more attention. Discharges of trace elements into water bodies and migration to ground water are also of concern, requiring knowledge of TE partitioning into coal combustion residuals during combustion and post-combustion treatment as well as the mobility of TEs out of these solids.

Coal combustion residuals (CCRs) include bottom ash, fly ash, and solid byproducts from flue gas desulfurization (FGD) units at coal-fired power plants. In the USA, CCRs are considered non-hazardous waste under the Resource, Recovery, and Conservation Act (RCRA); a Final Rule was issued by the U.S. EPA in 2015 on coal ash disposal and remediation of disposal sites [36] In Europe, CCRs are classified as non-hazardous waste and regulated under the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) [37]. When re-used, CCPs must be registered, subject to the Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals (REACH), Directive 2006/121/EC.

In 2016, 1.2 billion metric tons of CCRs were produced world-wide with an overall utilization rate of 64% [38]. Table 1 shows CCR production and utilization by country or region. If not re-used, CCRs are either stored at the power plant in surface impoundments (bodies of water confined within an enclosure, often containing a mixture of water and ash) or landfills (engineered structures built into or on top of the ground containing dry CCR solids), or sent offsite for landfill disposal. Ash in the environment can weather over time (e.g., in unlined landfills), resulting in concentrations of TEs in groundwater that can, in some cases, exceed local drinking water quality standards [39-42]. Individuals living near coal-fired power plants have increased risks of respiratory and cardiovascular disease, higher infant mortality, and poorer child health, associated with air pollutant emissions and the effects of TEs (including radioactive elements), migrating out of locally stored coal ash [5].

Table 1.

2016 Annual Production and Utilization of CCRs in millions of metric tons [38].

| Country or Region | Produced | Utilized | %Utilized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 12.3 | 5.4 | 43.5% |

| Asia | |||

| China | 656 | 396 | 70.1% |

| Korea | 10.3 | 8.8 | 85.4% |

| India | 197 | 132 | 67.1% |

| Japan | 12.3 | 12.3 | 99.3% |

| Asia, Other | 18.2 | 12.3 | 67.6% |

| Europe | 140 | ||

| (EU-15) | (40.3) | 38 | 94.3% |

| Middle East & Africa | 32.2 | 3.4 | 10.6% |

| Israel | 1.1 | 1.0 | 90.9% |

| USA | 107.4 | 60.1 | 56.0% |

| Canada | 4.8 | 2.6 | 54.2% |

| Russia | 21.3 | 5.8 | 27.2% |

| Total | 1,222 | 678 | 63.9% |

In the EU and Japan, almost all CCRs are utilized, instead of being disposed (Table 1). In the USA, where approximately half of the CCRs generated are not used, there are about 300 active on-site landfills at coal-fired power plants, which average more than 0.5 km2 (50 hectares) in area and have an average depth of over 12 meters, and more than 700 active on-site surface impoundments, which average more than 0.2 km2 (20 hectares) and have an average depth of 6 meters [43]. In addition to active landfills and impoundments, many more have been closed as coal-fired power plants retire. However, whether actively in use for ash disposal or closed, landfills and impoundments can be a source of TE contamination of surface waters and groundwater.

CCR landfills in the USA must monitor groundwater, control run-off, and have controls for fugitive dust. New landfills must be lined with an impermeable barrier, but many existing landfills are unlined. New and existing surface impoundments have similar requirements for groundwater monitoring. Surface impoundments also have restrictions regarding structural integrity of dams and other containment structures.

Regulations on CCR disposal facilities in the USA were tightened in 2015 [44], in part because of several large breaches of existing CCR ponds, the most notable of which occurred in December, 2008. The breach of a coal ash pond from the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) power plant in Kingston, Tennessee flooded more than 1.2 km2 (120 hectares) of land and released over 4.1 million m3 of ash. A survey immediately after the spill showed contamination of surface waters in nearby ponds, but only trace levels were found in the downstream rivers due to dilution [45]. A follow-up study eighteen months after the spill, showed TE concentrations, particularly As, B, Ba, Se and Sr, were below U.S. EPA drinking water limits in river water. Elevated levels were found in ponds and surface water with restricted water exchange and in pore water extracted from the river sediments [46]. Eight years after the spill, the concentrations of trace metals measured in river sediments downstream of the Kingston Plant were compared to concentrations at site located outside the zone of the ash spill. This comparison suggested that up to 80% of the As and 60-90% of the Se in the river downstream of the Kingston Plant were sourced from coal ash [47].

In addition to catastrophic events, like the large-scale rupturing of ash impoundments, CCR impoundments can leak into nearby surface waters or groundwater. For example, Harkness et al. [42] tested groundwater and surface water from 22 unlined coal ash storage impoundments in five states in the southeastern USA. Previous work had shown that boron and strontium isotopes could be used as tracers for the presence of other trace contaminants originating from CCRs [48]. Harkness et al. found isotopic fingerprints for B and Sr characteristic of coal ash at all but one site. Concentrations of CCR contaminants, including sulfate, As, Ca, Fe, Mn, Mo, Se and V, at levels above drinking water levels were observed in 10 out of 24 samples of surface water. Sixty-five groundwater monitoring wells (out of 165) showed high B levels and 49 had high levels of other CCR-contaminants [42].

At many municipal drinking water treatment plants, the disinfection of source water (from rivers and lakes) can produce halogenated organic compounds via the reaction between halides and trace amounts of organic compounds. Some of these disinfection byproducts (DBPs) have been determined to be carcinogenic [49]. Although bromide concentrations in natural waters are generally low, elevated levels of bromide in surface waters have been observed recently and coal-fired power plants have been suggested as one source of these elevated bromide levels [50,51]. In the USA, the implementation of the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) in 2014 [52] and the Refined Coal tax credit [53] (both discussed below), motivated some U.S. coal-fired power plants to add bromine to their coal to facilitate Hg removal [54,55]. If those plants also utilized an FGD, an increase in Br concentration was measured in the scrubber effluent. Source apportionment is not always easy or clear-cut, but it is possible that coal-fired power plants have contributed to increases in bromide discharges and DBP formation in municipal drinking water plants downstream of coal-fired power plants.

Review Outline

In summary, TE discharges to the air, soil, and water from coal combustion sources have been shown to have impacts on ecosystems and human health. Devising methods to better control emissions of TEs rests on a clear understanding of the forms of TEs in coal, their transformation during the combustion process, and their behavior in air pollution control devices. This review presents an overview of trace element chemistry in coal combustion systems with an emphasis on what has been learned over the past century uniquely related to the use of coal in boilers for electricity and heat production because these are used world-wide and represent the major pathway for most TEs from coal to be released into the environment for the foreseeable future.

The first section of the review focuses on the combustion system. Before discussing the detailed chemistry of TEs, we explain the concept of modes of occurrence of inorganic elements in coal because the mode of occurrence of a given element can affect its behavior in combustion systems. Semi-volatile elements are those that are partially volatilized from coal during combustion. This category includes all the TEs of environmental concern except mercury. Mercury chemistry differs from the semi-volatile elements (e.g. mercury completely vaporizes in the combustion system, forming different species post combustion with unique properties) and thus is treated separately.

The second section of the review discusses the advances in analytical methods that have allowed greater understanding of the chemistry of TEs and the methods to control TE emissions. Combustion systems are harsh environments and specialized sampling methods had to be developed to collect representative, stable samples from these systems. Measurement techniques were adapted, and new techniques were developed to characterize TE concentrations and forms in coal and coal combustion products. Finally, modeling tools that evolved to predict the behavior of TEs in combustion systems and in air pollution control devices are discussed.

Control of TE emissions to the environment from coal-fired systems was required in the U.S. and other countries as early as the early 21st century. The third section discusses the control of TEs using a variety of air pollution control devices. Emissions into the air of semi-volatile TEs that partitioned to PM are controlled primarily by particulate matter controls on coal-fired systems which represents the vast majority of TE air emissions. However, because of its high volatility and varied speciation in flue gas, mercury emissions were not as easily controlled. Considerable research was carried out in the final decades of the 20th century on mercury control, which is summarized in this section.

Before concluding, we briefly touch on current issues and future concerns regarding TEs in coal combustion systems. No review of such a complex subject can claim to be comprehensive. The authors have endeavored to highlight early, seminal work, which means that more recent work may be omitted or discussed superficially, especially if derived from earlier work.

The Chemistry of Trace Elements in Combustion Systems

The Composition of Trace Elements in Coals

The primary elements in coal are carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, but coal contains many inorganic elements in minor and trace quantities. The process of transforming organic plant matter to coal, a process known as coalification, is outside the scope of this work, but the reader is referred to, for example, references [56-58] for details. Much work has been published regarding the composition of coals from around the world (see, for example, [59-69]). The U.S. Geological Survey maintains databases on coal quality to which the reader is also directed for more information [67].

The mineral matter in coal comprises crystalline and non-crystalline inorganic compounds in discrete particles as well as inorganic elements dissolved in pore water or adsorbed on organic compounds [70-71]. The origins of mineral matter are the result of various processes that occur from coal formation to extraction. The interested reader can consult reviews by Ward [70,71].

Trace elements are referred to as those elements in coal with a concentration of 100 μg/g (ppmw) or less [73]. Through the 1980s, TEs were not directly analyzed in coal samples, but analyzed in coal ash that was produced by procedures that often involved heating the sample to 750°C-850°C. These high-temperature coal ashing procedures could volatilize elements like Hg or halogens, resulting in inaccurate concentrations when calculated on a whole-coal basis. Since the 1990s, direct methods of analyzing coal for TEs, such as instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) provide more accurate measurements of TEs in coal. In a review from the early 21st century, Ketris and Yudovich presented average values of TEs for coals from around the world calculated by the authors based on thousands of analyses of coal and coal ash samples [69]. Results from this review for selected elements are presented in Table 2, separated into brown coal (lignite) and hard (non-lignite) coal. Table 2, while not intended to be comprehensive, provides an idea of the order-of-magnitude concentrations of different TEs.

Table 2.

Average trace element concentrations for selected elements in world coals [69].

| Brown Coal | Hard Coal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | No. Samples |

No. Analyses |

Average concentrations (ppmw) |

No. Samples |

No. Analyses |

Average concentrations (ppmw) |

| Ag | 63 | 13,248 | 0.090 ± 0.020 | 96 | 11,799 | 0.100 ± 0.016 |

| As | 66 | 21,092 | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 124 | 22,466 | 9.0 ± 0.7 |

| B | 65 | 5,800 | 56 ± 3 | 103 | 13,834 | 47 ± 3 |

| Be | 80 | 48,001 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 118 | 114,256 | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| Br | 27 | 1,061 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 65 | 6,807 | 6.0 ± 0.8 |

| Cd | 40 | 2,251 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 75 | 15,079 | 0.20 ± 0.04 |

| Cl | 39 | 1,410 | 120 ± 20 | 83 | 9,981 | 340 ± 40 |

| Co | 95 | 69,660 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 142 | 125,023 | 6.0 ± 0.2 |

| Cr | 95 | 46,136 | 15 ± 1 | 141 | 64,442 | 17 ± 1 |

| Cs | 40 | 1,808 | 0.98 ± 0.10 | 70 | 11,765 | 1.1 ± 0.12 |

| Cu | 90 | 69,855 | 15 ± 1 | 139 | 75,121 | 16 ± 1 |

| F | 37 | 3,149 | 90 ± 7 | 77 | 11,249 | 82 ± 6 |

| Hg | 48 | 3,623 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 94 | 34,775 | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| I | 8 | 52 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 18 | 264 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| Mn | 82 | 23,231 | 100 ± 6 | 134 | 29,521 | 71 ± 5 |

| Mo | 80 | 71,606 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 131 | 104,901 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Ni | 93 | 70,560 | 9.0 ± 0.9 | 143 | 135,952 | 17 ± 1 |

| Pb | 78 | 67,744 | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 136 | 93,983 | 9.0 ± 0.7 |

| Sb | 43 | 5,220 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 92 | 13,662 | 1.00 ± 0.09 |

| Se | 39 | 2,323 | 1.0 ± 0.15 | 81 | 16,478 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| Tl | 28 | 1,588 | 0.68 ± 0.07 | 49 | 6,105 | 0.58 ± 0.04 |

| V | 97 | 83,964 | 22 ± 2 | 139 | 99,450 | 28 ± 1 |

| Zn | 84 | 78,908 | 18 ± 1 | 137 | 103,924 | 28 ± 2 |

Mode of occurrence of an element in coal refers to the specific compound or compounds, which can be associated with mineral inclusions and exclusions, or with the organic matrix (Figure 1). The mode of occurrence can determine how effectively pre-combustion coal cleaning can reduce the concentration of the element in cleaned coal. Furthermore, the mode of occurrence can affect the behavior of an element in the combustion process. Finkelman summarized what was known in the early 1990s about the modes of occurrence of the 11 TEs identified as hazardous air pollutants in the 1990 U.S. Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA) [74]. Finkelman acknowledged that elements could be found in multiple modes in a given coal and that the mode of occurrence could vary from coal to coal.

Figure 1.

Forms of occurrence of inorganic elements in coal.

Figure 1 illustrates the three primary categories of TE association in coal. Much of the inorganic material was associated with the original sediment layers which formed the organic structure of the coal. This material is usually organically bound in the final coal product. Larger portions of inorganic material in the original sediment layers may not be incorporated into the organic structure but become mineral inclusions. That is, the organic matrix surrounds the mineral phase. Other exclusions of inorganic material were mixed into the coal during geological events after the coal seam was formed or from non-coal overburden resulting from mining operations. Excluded minerals also include inclusions that are liberated from the carbon matrix during grinding [75].

Most minor inorganic elements are found in discrete minerals, but in certain coals Na, Ca, K, and Mg are associated with the organic matrix. Inorganic TEs are also found primarily in discrete minerals, either in specific mineral phases (e.g., Zn in sphalerite) or substituted in other minerals (e.g., Hg in pyrite). In certain coals Cr, Hg, Mn, Sb, Se, and halogens can be wholly or partially associated with the organic matrix [70-71,76].

Behavior of Trace Elements due to Coal Combustion

Measurement of TE emissions from coal-fired stacks preceded an understanding of how those elements were distributed in air emissions and, in some cases, in what form [14,15,17,77,78]. As discussed in more detail below, certain elements can vaporize during combustion and, in some instances, recondense (homogeneously or heterogeneously) and/or adsorb on or react with ash surfaces, which results in enrichment of the elements in the suspended ash (i.e., fly ash). Small particles offer relatively larger surface areas for these vapor-solid mechanisms to occur. Trace elements can be grouped according to the volatility of the element and its most likely molecular or atomic forms of occurrence in the combustion system as well as by observed partitioning between gas-phase, fly ash, and residual ash in coal-fired power plants [79-83]. Figure 2 depicts this classification of selected TEs into three groups:

Figure 2.

Classification of trace elements by observed behavior in coal combustion systems (adapted from [81]).

Group 1, completely volatilized during combustion with little enrichment in fly ash;

Group 2, partially volatilized during combustion, enriched in fly ash, and depleted in bottom ash;

Group 3, minimal vaporization during combustion with equal distribution between bottom ash and fly ash.

Certain elements showed intermediate behavior between groups that was not predicted from theoretical considerations of boiling points [80], leading to more work to elucidate the chemistry of transformation taking place in the coal boiler and air pollution control devices (APCDs). For example, the high boiling points of B2O3 and B (1800°C and 3297°C, respectively) would suggest that boron is minimally volatilized, contrary to observations in combustion systems.

Early models from the 1990s for predicting the air emission of TEs from coal combustion systems used emission factors that were derived from field observations. An emission factor represents the fraction of the input of a given TE that is emitted from the stack. Szpunar [84] published emission factors for the hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) as defined in the CAAA in the USA derived from field data on emissions. At the time these models were being developed, most coal-fired power plants had a particulate matter (PM) control device as the last control element before the stack. Due to their low pressure drop and corresponding low required fan power requirements, electrostatic precipitators (ESPs) were the most common PM control devices. More sophisticated emission-factor models took into account the distribution of a particular element in the fly ash as a function of particle size and the efficiency of PM removal in ESPs, baghouses or venturi scrubbers as a function of particle size [85,86]. While these models provided a means for estimating emissions, they did not shed light on the underlying chemical reactions taking place within coal combustion systems.

Helble [86] compared emission factors for individual elements with the collection efficiency of PM control devices at coal-fired boilers, noting that for most TEs, the emission factor of the element was approximately equal to the penetration efficiency of the PM control device with a few notable exceptions: mercury, selenium and, in some plants, arsenic. Helble proposed that certain TEs, such as selenium and arsenic, might be more strongly associated with the submicron particulate matter, which was known to be collected less efficiently than supermicron particles in PM control devices [25]. Mercury, on the other hand, was shown to be emitted primarily in the vapor phase [84].

Early work by Natusch and co-workers [14] demonstrated that certain TEs had an increasing concentration in emitted fly ash with decreasing particle size. The grouping of TEs by their potential volatility in the combustion zone [79-82], previously diagrammed in Figure 2, was consistent with the observations of Natusch et al [14], Helble [86], and others.

Unraveling the chemistry of TEs in the combustion and post combustion zones has been an active area of research for more than forty years [30,87-90]. The schematic diagram in Figure 3 (which has been drawn in various forms by many researchers, but was first published by Haynes et al. in 1982 [91]) illustrates the major pathways for inorganic elements in coal combustion systems, from the combustion zone to the inlet of particulate control devices. There are several important “chemical reactors” embedded within the overall process that determine the fate of TEs.

Figure 3.

Pathways for trace elements in coal combustion systems.

Semi-Volatile Trace Elements

A fraction of all TEs vaporize during the combustion process, with the degree of vaporization dependent upon the element’s volatility, its form of occurrence in the coal, and matrix effects from surrounding matter that may inhibit or facilitate vaporization [92]. Understanding the extent of vaporization as a function of combustion conditions (e.g., local temperature, local oxygen concentration) was the focus of much early research. Meserole and Chow [85] derived regression equations for vaporization of specific TEs during combustion based on field data. Yan and co-workers calculated vaporization of individual elements in the combustion zone using thermodynamic equilibrium [93]. More sophisticated single-particle models for vaporization of individual elements around a single burning coal particle were developed, which took into account the effects of local temperature and oxygen concentration [94-97] and the associations of certain elements with the mineral matter [98].

Predicting vaporization of TEs is a first step in understanding their fate in coal combustion systems. In addition to Hg, semi-volatile elements (As, Sb, Se) vaporize in the combustion zone almost entirely [99-102]. More refractory elements (e.g. Al, Fe) may partially vaporize depending on temperatures, local environments, modes of occurrence, and volatility. These elements often nucleate first, and then grow by coagulation and condensation as temperatures fall and partial pressures of increasingly volatile species become supersaturated [103-105]. Nucleation, coagulation, and condensation in the combustion and post-combustion regions produce submicron particles, while release of included material, char fragmentation, and condensation yields fine fragment and coarse particles. Submicron particles offer relatively larger surface areas for condensation processes promoting preferential enrichment. Extremely high number concentrations and high collision frequencies cause coagulating nuclei to grow quickly into an accumulation mode (more commonly known as the submicron fume). Together, these processes result in three size modes of fly ash particles centered at approximately 0.4, 2 and 20 μm, corresponding to accumulation, fine fragmentation, and coarse modes [106-110].

Models were developed to predict the size distribution of fly ash in the combustion zone and the partitioning of semi-volatile TEs to the fly ash [111-113]. Lockwood et al [112] concluded that “heterogeneous condensation of the metal vapours alone is insufficient to explain fully the fate of metal vapours. Surface reaction and gas phase chemical reaction should also be considered, but the necessary chemical kinetic data are currently lacking."

The submicron particles in the combustion and post combustion zone provide a relatively large surface area for chemical reaction. It has been known for some time that the composition of the submicron aerosol is different from that of the supermicron particles [ 14, 114, 115]. The latter have an overall composition similar to that of the bulk average ash in the parent coal, although the composition of individual supermicron particles is not uniform [116,117]. The composition of submicron particles, in contrast, is often enriched in certain major elements (Na, Ca, Fe), minor elements (S, Cl), and TEs (As, Se, Sb, Cd) relative to the bulk ash composition [118]. However, such enrichment in submicron ash has been shown to be dependent on the type of coal or, more specifically, the mode of occurrence of the element in the coal [92,119]. Furthermore, the degree of enrichment of As and Se in submicron particles was shown to depend on the concentrations of iron and calcium in the fine fly ash and the amount of SO2 present in the flue gas, leading to the hypothesis that, for many coals, the enrichment was the result of a surface chemical reaction between As or Se with Fe or Ca, with interference from a competitive reaction of Fe or Ca oxides with SO2 [120]. Models for the reaction of individual fly ash particles with gaseous arsenic [121] and gaseous selenium [122] as a function of temperature, fly ash size and fly ash composition were subsequently developed to provide more insight into mechanisms in actual combustion systems.

Mercury Chemistry

The chemistry of mercury in coal combustion systems has been an active area of study, because of the early documentation of Hg accumulation in the environment from anthropogenic activities, as discussed in the Introduction, which resulted in regulations to limit Hg emissions from incinerators, municipal waste combustors, and coal-combustion sources. Regulations have often been developed to reduce emissions by requiring application of control technologies.

Unlike the other TEs emitted from the stacks of coal combustion systems, Hg is not effectively controlled by PM control devices like ESPs and baghouses. Therefore, considerable research and development work was required to devise effective control strategies for Hg emissions. Control technology could not have been reliably and cost-effectively implemented without a sound scientific understanding of Hg chemistry. In this section, the focus is on Hg chemistry in the combustion and post-combustions zones, while a subsequent section will address how the science was applied to Hg control technologies.

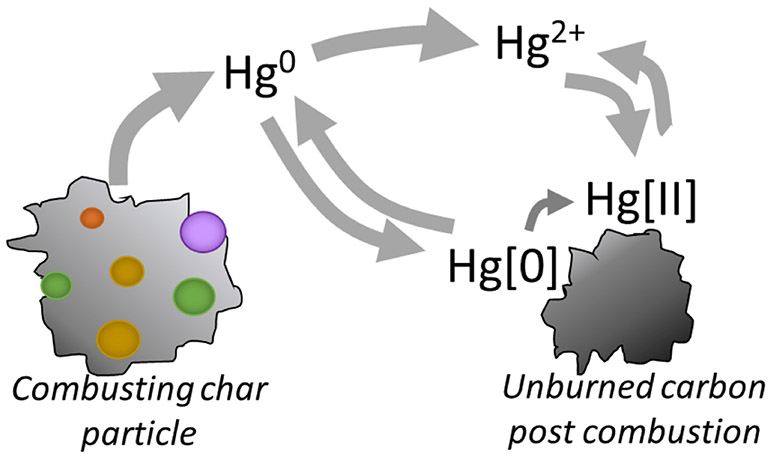

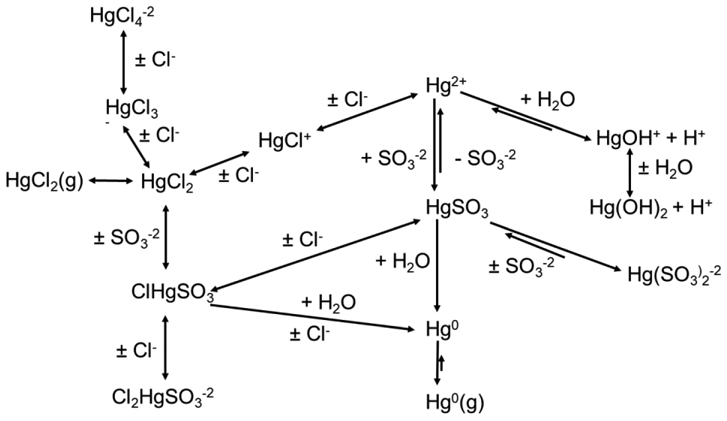

Figure 4 provides an overview of Hg chemistry, which, as will be noted below, is not as simple as the figure would indicate. In the high-temperature regions of coal-fired boilers, Hg primarily exists as the gaseous elemental form (Hg0). As the flue gas cools in the post combustion zone, Hg0 may be converted to gaseous oxidized forms (Hg2+) or partition to particulate-bound mercury (Hgp). As noted above, methods for measurement of mercury in flue gas can distinguish between Hg0 and Hg2+, but cannot identify specific oxidized mercury compounds. In the presence of halogens, gas-phase equilibrium conditions favor the formation of Hg2+ at the temperatures of APCDs [123, 124]. However, the oxidation of Hg0 is kinetically limited by gaseous (homogeneous) and gas-solid (heterogeneous) reaction rates. As a result, mercury enters the APCDs as a mixture of Hgp, Hg2+, and Hg0. Oxidized forms (HgCl2, etc.) have a high solubility in water, whereas Hg0 is only sparingly soluble [125]; thus, oxidized forms of mercury are much easier to remove from the flue gas in flue gas desulfurization processes, as will be discussed in later sections. The chemical form (elemental or oxidized) and partitioning (gas-phase or particulate phase) of Hg affects the ability to control Hg emissions.

Figure 4.

Overview of mercury chemistry in flue gas.

The extent of conversion of Hg0 to Hg2+ and Hgp depends on the flue gas composition, the amount and properties of fly ash, and the flue gas quench (i.e. cool down) rate. Thermodynamic arguments suggest that hot flue gases containing Hg and halogens (like Cl) should contain a high proportion of gaseous oxidized mercury (e.g., HgCl2) as first noted in works on Hg behavior in incinerators [126,127]. An early survey of Hg emissions from coal-fired power plants in the USA showed a correlation between the amount of Cl in the coal and the fraction of oxidized mercury in the flue gas [128]. However, the concentration of oxidized mercury in flue gas was often found to be considerably lower than expected from simple equilibrium considerations, as first noted in work on waste incinerators. Widmer and co-workers postulated that the rate at which the flue gas cools post combustion (the quench rate) was a factor in the gas phase oxidation of Hg0 to HgCl2 and subsequently performed bench-scale experiments to demonstrate the effect of quench rate on oxidation [129]. Quench rate affects the oxidation of mercury by chlorine-containing species, because the major gas-phase pathway for the formation of Hg2+ is via reaction with atomic chlorine, which is kinetically limited at the typical quench rates of commercial combustion systems [130,131]. That is, boiler quench rates are often too high to maintain high atomic Cl concentrations which limits HgCl2 formation.

The halogen content of coals varies widely. For example, in a detailed study of coals from the USA [195], Cl concentrations ranged from 10 to 5,000 μg/g. Low-rank coals, such as lignite, have lower Cl contents than bituminous coals, as the average values in Table 2 illustrate. Bromine concentrations are typically 2 to 4% of the Cl concentrations, also shown in Table 2 and Reference [132]. Iodine concentrations are lower than bromine concentrations, although with fewer samples available, it is hard to generalize.

Laboratory testing of homogeneous oxidation (Figure 5) showed that, compared to chlorine, bromine was much more effective at oxidizing mercury at typical commercial combustion system quench rates [133]. Full-scale testing of the effects of different halogens on the degree of Hg oxidation at the APCD inlet demonstrated that Cl was less effective than Br or I in terms of mercury oxidizing efficiency (on an equal weight basis) [134].

Figure 5.

Homogeneous oxidation of mercury by halogens in a laboratory combustor as a function of initial halogen concentration [133].

Early work on gas-phase kinetic modeling using power plant conditions in the late 1990s and early 2000s provided considerable insight into the effects of quench rate, halogen speciation, and other constituents in the gas such as H2O and NO, for example [ 130, 131, 135-137]. After extensive work on gas-phase oxidation kinetics, it became clear that gas-phase models generally underpredicted the degree of mercury oxidation in full-scale boilers at the inlet to the air pollution control devices (approximately 150°C). These results suggested that homogeneous (gas-phase) oxidation was not the only pathway for Hg oxidation. Coal flue gas contains fly ash, containing both metal oxides and unburned carbon, both of which have been shown to be effective, in some circumstances, both for heterogenous oxidation of mercury and for adsorption of oxidized Hg.

Different metals and metal oxides have been shown to be effective oxidation catalysts for Hg in coal flue gas [138]. Metal oxides in fly ash, principally forms of iron oxide, catalyze the oxidation of Hg0 to Hg2+ in the presence of halogens [139-143]. Carbon surfaces, such as the surfaces of unburned carbon in fly ash or activated carbon, have also been shown to act as oxidation catalysts for Hg [141, 144].

Mercury adsorption on carbon is one method to capture Hg from the gas phase. The unburned carbon in fly ash, which can sometime be present in significant concentrations, can adsorb oxidized Hg in the flue gas. Hower et al. [145] observed a correlation between Hg content and carbon content of bituminous fly ash samples collected from ESP hoppers. Senior and Johnson [146] showed a correlation between Hg removal across full-scale ESPs and the carbon content of the fly ash in coal-fired power plants burning bituminous coals, which had between 1.5 and 67 wt.% carbon in ash. These field studies suggested that Hg was adsorbed onto the carbon in fly ash and subsequently removed with the carbon in the particulate control device. More detailed laboratory experiments confirmed the ability of unburned carbon in fly ash to adsorb Hg [141, 147, 148]. This result led to the development of technologies that use activated carbon adsorption as a pollution control method, as discussed in the Trace Elements in Air Pollution Control Devices section of this paper.

Methods

Elucidating chemical mechanisms in a complex environment would not be possible without a variety of analytical methods, some of which were developed specifically to understand TEs behaviors in coal combustion systems. In this section, advancements in sampling procedures, analytical methods, and modeling are discussed.

Sampling Procedures

Before chemical analysis can commence, a stable and representative sample must be obtained. Collecting samples from combustion systems and air pollution control devices presents challenges. The gas phase, whether in the combustion or post-combustion zone, is hot (60 to 1500°C) and wet (8-18 vol% moisture). Phase changes and varying dew points add to the sampling complexity. Flue gas often contains corrosive acid gases (e.g., SO2, SO3, HCl) and a considerable burden of particulate matter as illustrated in Table 3. We note that Table 3 is a broad representation, but allows the reader to envision some of the important species that can interact with TEs such as oxygen, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, halogen species such as hydrogen chloride, and entrained particles.

Table 3.

Flue gas composition at boiler exit estimated from combustion calculations; fly ash concentrations from [25].

| Specie | Units | Range |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 | vol% | 13-16% |

| O2 | vol% | 3-4% |

| H2O | vol% | 8-12% |

| N2 | vol% | Balance, ~73% |

| Fly ash | g/Nm3, dry | 5-20 |

| HCl | mg/Nm3, dry | 1-200 |

| SO2 | mg/Nm3, dry | 400-10,000 |

| SO3 | mg/Nm3, dry | 2-100 |

| NOx* | mg/Nm3, dry | 200-1,000 |

| CO | mg/Nm3, dry | 20-1,000 |

| Total Hg | μg/Nm3, dry | 5-30 |

NO + NO2, mg/m3 calculated as at NO2

Sampling Trace Elements in Flue Gas

Certain TEs in coal combustion flue gas can exist in both gaseous and solid forms along the flue gas path from the combustion zone to the stack, notably As, Hg, Se, and Sb. Quantifying TE concentrations in flue gas requires dedicated sampling systems that could extract a representative sample of the hot gas for analysis. Starting in the 1970s, methods for sampling flue gas for TEs were based on wet chemical methods (i.e., methods designed to capture the elements of interest in solutions for analysis) [12]. An example is U.S. EPA Method 29 [149], illustrated in Figure 6. EPA Method 29 was designed to measure the solid particulate and gaseous emissions of Hg and 16 other TEs (Sb, As, Ba, Be, Cd, Cr, Co, Cu, Pb, Mn, Ni, P, Se, Ag, Tl, Zn). Because of the presence of particles in the flue gas, the method uses a probe inserted into the flue gas stream. The sample gas is drawn through the probe at a nearly identical “isokinetic” velocity to that of the bulk gas. By matching sample and duct gas velocities, streamlines remain straight, ensuring a representative sample of particles. A heated filter removes particles in the sample train. The probe itself is glass-lined so that the acid gases in the sample do not contact metal surfaces. The probe, filter, and sample lines are heated to prevent condensation of water. Following the filter, the sample gas is bubbled through a series of solutions in impingers intended to absorb key chemicals of interest out of the gas. Following sampling, particles collected on the filter and from dried probe rinses are typically weighed, and digested in strong acids for wet chemical analysis.

Figure 6.

U.S. EPA Method 29 for measurement of TEs in flue gas, adapted from [149].

There are practical limitations to the impinger-based methods. The methods often require long sampling times (2-6 hours) in order to obtain TE concentrations above analytical detection limits. Further, if the intent is to absorb chemicals with widely different properties, a complex sample train composed of relatively large amounts of glassware and tubing is required. Furthermore, the glass impingers contain strongly oxidizing and acidic reagents requiring labor-intensive sample recovery and analytical procedures for quantification. Alternate measurement methods have been developed for Hg that are faster and less expensive, including sorbent traps [150] and continuous emission monitors [151]. All methods must still have appropriate sample conditioning systems to remove particles and prevent interference from moisture and acid gases. Continuous emission monitors for gaseous Hg have been widely adopted at coal-fired power plants, which typically use specialized probes that dilute the sample gas (to prevent condensation of moisture) and separate particles from the sample gas, thus delivering a low-moisture and largely particle-free sample to the measurement apparatus.

Size-Segregated Particulate Sampling in Flue Gas

The sampling methods discussed so far either collect all the particulate matter in the flue gas on a filter or discard most of the particulate matter. However, the ability to collect a size-segregated sample of particulate matter for chemical analysis was critical to understanding the interactions between TEs in the gas phase and ash in the combustion and post-combustion environments. This was made possible through the development of cascade impactors, particularly those operated at very low (sub-atmospheric) pressures. The current state of the technology, low-pressure impactors can segregate the PM into 13 size-segregated samples with up to seven different submicron size categories in quantities sufficient for chemical analysis. It should be noted that while cascade impactors are used in most instances, cascade cyclone systems are also available for particle classification and collection. Often both approaches utilize after filters to collect the smallest size fraction of particles.

Impactors and cyclones utilize particle inertia to separate particles from gas. A cascade impactor is an inertial separation device consisting of size-dependent PM collection stages. In each stage the inlet particle-laden gas stream is forced to make a turn around an obstruction before passing through a specifically sized nozzle. In general, the nozzle sizes get smaller and smaller as the gas travels through the impactor. The stage may consist of a single jet (Figure 7a) or multiple jets (Figure 7b). As the gas makes the turn around the obstruction, particles with a mass that corresponds to a size larger than the design size for the stage will have too much momentum to make the turn and enter the nozzle and will impact the collection plate surrounding the nozzle and be removed from the gas. The correspondence between particle mass and particle size is known as the aerodynamic diameter (note: physical and aerodynamic diameters are identical only for spheres of unit density, 1 g/cm3). Smaller particles will travel with the gas to the next smaller sized stage meaning that smaller and smaller particles are captured on each subsequent stage.

Figure 7.

Cross-sectional schematic of cascade impactor stages with (a) single jet or (b) multiple jets.

Extraction of particles from gases by means of inertial separation and impaction has been used since the 19th century (see Marple [152] for a detailed history of the impactor). The cascade impactor, first developed by May [153], allowed particles to be collected and segregated by size. May’s impactor used four stages, each with a single jet, to collect particles in the range of 50 micron down to 1.5 micron in aerodynamic diameter. The Battelle impactor, developed in the 1950s, used six single-jet stages to collect particles down to 0.5 micron in aerodynamic diameter [154]. Andersen [155] developed a six-stage impactor with multiple jets per stage, which allowed the collection of larger samples. In the late 1960s, cascade impactors started to be used to sample directly from ducts and stacks of industrial processes, including coal-fired boilers. These impactors, such as the University of Washington impactor [156], were made of stainless steel to allow direct insertion into hot flue gases. Hering and co-workers [157] improved the cut-off diameter of collection by designing an eight-stage impactor with a sonic orifice in between stages four and five, thus allowing the lower stages to operate at reduced (sub-atmospheric) pressure. The lowest stage collected particles down to 0.05 micron in aerodynamic diameter. While Hering and co-workers used a single jet per stage for their low-pressure impactor, Berner and co-workers [158] developed a multi-jet low pressure impactor that could collect particles down to 0.08 micron in aerodynamic diameter. Hillamo and Kauppinen [159] demonstrated a version of the Berner impactor that could collect particles as small as 0.032 micron in aerodynamic diameter on the lowest stage.

In sampling from combustion flue gas, the isokinetically collected sample gas is often diluted with a dry, inert gas like nitrogen to remain above the dew point, preventing condensation of moisture on the stages (particularly at the low pressures of the stages that collect the smallest particles), and to freeze any subsequent reaction or agglomeration in the gas during sampling. Certain coals (e.g., bituminous) produce a higher fraction of large (>10 μm) particles, which can quickly overload the initial stages of the impactor. When this occurs, subsequent particles will no longer stick to the stage plate surface, but will bounce off and through the nozzle onto the next (smaller sized) impactor stage. This effect will bias the particle size distribution measurement and may cause particles from different PM formation modes to blend together, which would contaminate chemical measurements. A cyclone pre-separator is often used upstream of the cascade impactor to remove the largest particles, if good resolution of submicron particles is desired. Impaction surfaces may also be treated with thin coatings of inert materials (typically high-purity grease) to minimize particle bounce effects. The stages (and the pre-separator catch) are subsequently weighed to generate a distribution of particle mass as a function of aerodynamic diameter.

Development of the ability to collect representative samples of size-segregated fly ash and gaseous TEs from flue gas for subsequent analysis enabled the understanding of chemical mechanisms. The next section discusses analytical methods applied to such samples to quantify concentration and speciation of TEs.

Analytical Methods

Trace Elements in Coal and Ash

Considerable work was done in the 1980s and 1990s on methods for identifying the modes of occurrence of TEs in coal and coal byproducts. Knowing the form of the TE in the coal (the starting point) and the form of the TE in the gas phase or solid phase post combustion (the end point), led to greater understanding of the physical and chemical mechanisms controlling TE transformations in combustion environments. In some cases, analytical methods were developed or adapted specifically for samples from coal combustion systems.

Several factors led to the generation of useful information on mode of occurrence. Large collaborative programs, in which multiple researchers analyzed the same coals, took place in the 1990s [160,161]. In addition to traditional mineralogical analysis, several highly specialized methods were used to good effect. Selective leaching (also known as chemical fractionation) provided element-specific, quantitative information on associations of TEs with specific mineral phases [161-164]. X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy (XAFS) used specially tuned x-ray energy to probe the local structure, including bond distance and electronic states, of a specific element. Much use was made of XAFS and X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) to understand the speciation of elements in coal [165-167]. Trace element microanalyzers such as laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) and ion microprobes such as the Sensitive High-Resolution Ion Microprobe with Reversed Geometry (SHRIMP-RG) were used to probe the distribution of TEs in individual mineral inclusions, which clearly demonstrated associations with specific mineral phases [168].

Specialized analytical methods were also developed and applied to fly ash and carbonaceous sorbents to better understand the fate of TEs in the combustion or post-combustion zones. Batch wet chemistry methods developed to digest coal ash, while time-consuming, allowed comprehensive analysis by ICP-MS, inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES), graphite furnace atomic emission spectrometry (GFAAS), and neutron activation analysis (NAA) even when the sample size was on the order of milligrams, micrograms, or nanograms of material. Both XAFS and XANES were used to study speciation of many different elements in fly ash, including Hg, As, Cr, and Se [169-174]. Analysis of leachates from fly ash by ion chromatography also yielded speciation information [175-177]. Surface chemical analysis of fly ash composition has been carried out by such methods as scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS), LA-ICP-MS [178], and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [179-183].

Laboratory testing of the leaching of TEs from CCRs has been used to predict the potential for leaching in the environment. Laboratory work in the 1980s was conducted using column leaching and batch methods [184-187]. The speciation of certain elements like As and Se was also measured in leachate to better understand the impact and environmental fate of these elements [185, 188, 189]. Laboratory evaluations of leaching were improved to better represent the varied environments in which CCRs may reside. The Leaching Environmental Assessment Framework developed by U.S. EPA is a set of laboratory protocols that provide flexibility in test methods to simulate key environmental conditions affecting leaching [190, 191].

Utilizing the specialized sampling methods discussed above, the size distribution of coal combustion aerosols has been measured by optical, electrical or inertial means in laboratory combustors and at coal-fired boilers (see, for example, [106,192]). As discussed in subsequent sections, knowledge of the number and mass distribution of the fly ash, either in-process or in-stack, provides valuable information on the physical mechanisms of ash formation and environmental fate. However, to understand the chemical mechanisms leading to speciation and emissions of TEs, chemical analysis of size-segregated fly ash was necessary.

Early work on fly ash from a coal-fired power plant by Davison et al. [114] analyzed fly ash from the hopper of a PM collection device, which had been mechanically sieved, and in-stack samples collected using a cascade impactor. Trace elements in the size-classified samples were analyzed by different methods, depending on the specific element, including DC arc emission spectrometry, atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS), X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, and spark source mass spectrometry. Other analysis methods have been used for chemical analysis of individual impactor stages, including instrumental NAA [193] and GFAAS [20, 107]. Seames and co-workers [194] modified U.S. EPA's Toxicity Characterization Leaching Protocol (TCLP) Method 1310 to allow the testing of inorganic compounds contained on cascade impactor stages. The modified method was used to explore the solubility of four TEs from five different types of coal fly ash as a function of particle size, which provided information on element speciation in ash.

Wet Chemistry Methods for Mercury Quantification

Mercury emissions from incinerators became a concern in the 1980s [195]. In the USA, EPA’s Method 101A (“Hg in sewage sludge incinerators”) was first promulgated in 1982 as a method for measuring both particulate-bound and gaseous mercury. This was an impinger-based, wet chemistry method for measuring total mercury in incinerator stacks. Because incinerator feed streams often contain Cl, theoretical considerations suggested that Hg in air emissions from incinerators would be in an oxidized form, i.e., HgCl2 [196]. Methods were developed in the 1980s to measure elemental and total mercury in incinerator air emissions to allow discrimination between elemental and oxidized forms of mercury [197].

In the 1990s, wet chemistry and batch or discrete sampling methods (e.g., EPA Method 101A, EPA Method 29) were accepted methods for measuring total gaseous and particulate mercury from coal combustion sources. The Ontario Hydro method was subsequently developed as a wet-chemical method intended to measure elemental and oxidized gaseous mercury as well as particulate-phase mercury, later codified as ASTM Method D-6784 [198].

Wet chemical methods for measuring Hg proved cumbersome and expensive. Typically, three replicate measurements were made, each six hours in duration. The sampling train (see Figure 6) was complex, carrying out the measurement required trained personnel, and results from an off-site laboratory were ready in one to two weeks. Such methods hampered research and development efforts to understand Hg chemistry and to develop Hg control technologies for coal combustion systems.

Mercury Sorbent Traps

To produce less expensive and faster measurement of Hg in flue gas, dry batch methods (also known as sorbent trap methods) were developed. Sorbent trap methods involved a probe inserted into the flue gas duct, as with the wet chemistry methods, but the probe itself contained glass tubes filled with solid sorbents that trapped Hg as the sample gas was pulled through them [68]. The sample time of sorbent trap methods can vary from 30 minutes to a week. On-site analysis of the sorbent in the traps was introduced to provide rapid turnaround for the results. Specialized sorbent traps for distinguishing between gaseous oxidized and gaseous elemental mercury were also developed [199] as well as sorbent traps specific to gas-phase As and Se [200].

Continuous Emission Monitors for Mercury Measurement

While sorbent traps provided faster measurement than wet chemical methods, the discrete nature of the sampling process could not produce the continuous measurement needed to dynamically control Hg emissions in certain control technology applications. Continuous emission monitoring (CEM) systems for Hg measurement in flue gas face similar sampling challenges as discrete methods in that a hot, particle-laden gas containing water and acid gases must be sampled. The most frequently used detection methods for continuous measurement of Hg concentration in combustion gases are AAS and atomic fluorescence spectroscopy (AFS). To use either detection method, Hg must be present in the gaseous elemental form. Because gaseous mercury can be in the elemental form or in the oxidized form, reductants are used to convert all the mercury in the gas to the elemental form so that it could be detected. The detection methods are susceptible to interference or performance degradation from acid gases present in combustion flue gas (HCl, SOx, etc.).

Early models of CEMs used liquid-filled impingers in the sampling systems to convert oxidized mercury in part of the sample to elemental mercury, while measuring only elemental mercury in another part of the sample gas. This allowed CEMs to measure both total gaseous mercury and elemental gaseous mercury in flue gas while removing acid gases. More recently, conversion to elemental mercury in the CEM is done in the gas phase, either thermally or catalytically. Dilution of the sample gas is used as a way to greatly reduce the interference of acid gases on the measurement. Newer CEMs can also measure total or elemental mercury, and have proved to be rugged and reliable enough for permanent installation as compliance monitors. Details can be found in [151].

Significant advances in Hg measurement technology in combustion systems have occurred since early efforts in the 1970s. Without such advances, the study of Hg chemistry in combustion systems as well as the development of effective control technology would have been severely hampered. Furthermore, the promulgated emission limits are based on measurements in coal-fired utility boilers, and compliance with those limits depends on reliable, continuous stack measurements of Hg.

Modeling and Computational Methods

New computational methods were also required to understand the complex chemistry of TEs in coal combustion flue gas and in air pollution control devices. This section highlights the tools that contributed to the many models developed to understand and to predict TE behavior. Later sections discuss some of the modeling efforts in context.

Thermodynamic equilibrium models have been used to define the limits of possible behavior of TEs in both oxidizing and reducing conditions typical of coal combustion or gasification environments [123, 124]. These equilibrium models rest upon early U.S. National Institutes of Standards and Technology and Joint U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force (NIST-JANAF) databases from the 1970s with updated and expanded thermodynamic data [201,202]. Such models provide insight into the chemical forms of occurrence that are possible for each TE, but cannot predict the actual presence of any specific specie, and therefore must be used with care. With the notable exception of Hg, the molecular forms of gas-phase TEs are primarily formed in the highly dynamic environment surrounding the TE’s original ash or coal particle location. As discussed in more detail in subsequent sections, gas-phase mercury oxidation is kinetically limited, even at higher temperatures, because of low concentrations of Hg and kinetic limitations on halogen speciation. Gas-phase mercury can approach equilibrium distributions in the presence of certain catalysts (e.g., SCR catalysts). Post combustion, the flue gases are subject to rapid cooling as heat is extracted to superheat steam, which means the assumption of equilibrium is not valid.

Powerful computational tools have been developed which can accurately predict key properties of molecules that are useful for understanding chemical reactions. These developments have come about because of dramatic increases in computer speed and memory and because of the design of efficient quantum chemical algorithms. The goal of ab initio quantum computations is to provide an accurate approximation of the energy states of atoms and molecules. Chemical properties are obtained from derivatives of the energy with respect to external parameters. Many properties can be computed by these methods, including (but not limited to):

Bond energies and bond lengths;

Reaction energies;

Vibrational frequencies;

Reaction pathways and mechanisms.

The functions used to describe atomic orbitals are known as basis functions and collectively form a basis set. Larger basis sets give a better approximation of the atomic orbitals, but they require more computational power. Many basis sets are available, depending on the nature of the atoms and the bonds between atoms. Choosing the correct basis set and using the appropriate level of theory are crucial for obtaining an accurate description of atoms and hence their properties.

Starting in the late 1990s, detailed kinetic mechanisms were developed to predict the gas-phase oxidation of mercury in coal combustion systems. Individual rates constants were developed using ab initio quantum computations, first with a focus on Cl species [130,137,203-208], then extended to bromine [208-212] and iodine species [212-214]. The interaction of Hg and surfaces has also been modeled using quantum computational methods. Carbonaceous surfaces, which might represent unburned carbon in fly ash or activated carbon sorbents, have been the subject of a number of studies (for example, [183, 215-219]). Metal and metal oxide surfaces, which might represent metal oxides in fly ash, metal oxides in SCR catalysts, or noble metals, have also been modeled (for example, [220-223]). While most of the quantum chemical modeling has applied to Hg chemistry, these methods have also been applied to selenium and arsenic species (for example, [224-225]).

Quantum computational chemistry does not replace experimental measurements, but can be used to explore new or unknown chemistry. This has proved useful for certain TEs such as mercury, selenium, and arsenic in coal combustion systems.

Trace Elements in Air Pollution Control Devices

In this section, we discuss some of the ways that APCDs affect trace elements. Trace element chemistry starts in the combustion zone, but doesn’t always end when flue gas leaves the boiler and enters the various APCDs. In some cases, years of research were needed to unravel the complexities.

There is no standard set of APCDs, but the most commonly used APCDs on the newest generation of coal-fired power plants will be assumed here. For more detailed information, the reader is referred to [226]. Figure 8 depicts a common configuration of the current generation of coal-fired power plants that are being built around the world. These plants use pulverized coal, that is, coal that has been ground to about 90 microns average size. The coal is pneumatically conveyed to the boiler through distribution piping and then injected into the combustion zone using specially designed burners. Coal particles experience the high-temperature combustion zone (~1700°C), generating a mixture of gaseous and solid combustion products (flue gas). A portion of the solid ash components (bottom ash) settle within and are removed from the boiler, and the remaining portion (fly ash) are carried by the gas flow downstream. The combustion zone contains heat transfer surfaces in which water is boiled to make steam, then, post combustion, the steam is superheated by means of more heat transfer surface, which cools the flue gas to 350 to 400°C. After passing through the air heater, a gas-gas heater exchanger to preheat the combustion air, the flue gas is further cooled to 130 to 200°C.

Figure 8.

Modern pulverized coal-fired power plant, from coal pile to stack with common air pollution control devices: selective catalytic reduction (SCR), electrostatic precipitator (ESP) or baghouse, wet gas desulfurization (FGD) scrubber.

As the gas cools, it passes through a series of APCDs — that function as a series of chemical reactor/PM separator units — in order to reduce the concentrations of certain regulated pollutants. However, the APCDs also often transform some of the minor and trace elements in the flue gas and entrained ash as it passes through them. Temperatures and residence times will vary from one boiler to another, depending on the fuel characteristics, operating conditions, and specific design of APCDs. Figure 9 provides a representative time-temperature history.

Figure 9.

Representative flue gas time-temperature history for pulverized coal-fired boiler (refer to text for definitions of acronyms).

Selective Catalytic Reduction

Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) is commonly used to reduce NO and NO2 in the flue gas. Arsenic and mercury have significant interactions with SCR catalysts, which are discussed here. SCR processes typically use a V2O5 catalyst to promote the reaction of ammonia and NO at a gas temperature of approximately 370°C. For NO, the global reaction is written as:

A similar global reaction can be written for NO2, although at SCR temperatures almost all the NOx consists of NO. The detailed mechanism [2272] is initiated by the adsorption of an ammonia molecule on a vanadia (V5+-OH) site. The ammonia molecule is activated by reacting with a V=O redox site, which is converted to (V4+-OH). The activated ammonia reacts with gaseous (or weakly adsorbed) NO to produce N2 and H2O. In a final step, O2 oxidizes V4+-OH back to V=O.

The catalyst consists of porous ceramic material impregnated with V2O5 and supported on closely spaced plates or extruded in a honeycomb configuration. Gaseous ammonia reagent is mixed into the flue gas at the inlet to the SCR reactor. In addition to reducing NOx, SCR catalysts interact with gaseous or particulate-bound TEs in the flue gas.

Catalyst Deactivation by Arsenic

Ideally, the catalyst would retain its initial activity for NOx reduction indefinitely, although catalyst manufacturers typically assume a certain loss of catalyst activity as a function of time when specifying a catalyst for specific operating conditions. Over time the activity of an SCR catalyst declines either from physical means (e.g., blockage of pores by fly ash, erosion) or by chemical reactions between the active sites and flue gas constituents (e.g., As, Na, K) [228]. Sometimes this decline is steeper than predicted, because the plant operating conditions or the fuel properties were not as originally assumed.

SCRs were first used on coal-fired boilers in Japan and Germany, which burned coals with relatively low As contents, and thus little impact of As on SCR operation was observed except in specific power plant configurations. Certain power plants in Germany recirculated fly ash back into the boiler and experienced accelerated deactivation of the SCR catalyst [229]. Reinjecting fly ash back into the combustion zone causes As from the ash to vaporize, thus increasing the concentration of gaseous arsenic (As2O3) in the flue gas. Gaseous arsenic reacts with vanadium sites in SCR catalysts, which reduces the catalytic activity for NOx reduction. Fly ash recirculation at a power plant in Germany was estimated to increase the total As concentration in the flue gas by 6.5 times [229].

As SCRs began to be widely deployed in the USA, excessive deactivation from As was noted at certain plants, either because of fly ash re-injection at cyclone-fired boilers [228] or because the coal in use had a very low calcium content in the ash [230]. As discussed above, gaseous arsenic reacts with calcium compounds in the fly ash. If the coal calcium content is too low relative to the As content of the coal, gaseous arsenic oxide will be present in the SCR reactor at high enough concentrations to cause accelerated deactivation of the catalyst.

Based on thermodynamic considerations, arsenic is assumed to be gaseous As2O3 or the dimer As4O6 at the temperature of the SCR. Catalyst deactivation by arsenic oxide is thought to occur by blocking micropores in the catalyst, which prevents NO and NH3 from reaching active sites, and by chemical reaction with vanadium sites. One approach to improving performance under high-arsenic conditions is to reformulate the catalyst, both chemically and physically [231]. Another approach is to add limestone (primarily CaCO3) to the boiler [228-232]. In the furnace, limestone decomposes to CaO, which reacts with gaseous arsenic oxide upstream of the SCR to form solid Ca3(AsO4)2, which can then be removed in the downstream particulate control device [232]. Other power plants use blends of higher calcium-containing coals with the original coal to obtain the same effect.

Figure 10 illustrates the effect of adding limestone to reduce the gas-phase As concentration in three coal-fired combustion systems that used fly ash re-injection, and thus had high arsenic oxide concentrations in the gas [228]. The figure shows gaseous arsenic concentrations measured at the inlet of the SCR, that is, at operating temperatures in the range of 350°C to 400°C. The addition of limestone reduced the concentrations of vapor-phase arsenic by about two orders of magnitude. Knowledge of the chemistry of arsenic in coal combustion systems supported a successful strategy for mitigating the effects of arsenic on SCR catalysts.

Figure 10.

Measured arsenic concentration at SCR inlet (in μg/Nm3) as a function of coal arsenic content. Data of Pritchard et al. [228] shown for boilers with 100% fly ash recycle, with and without limestone injection for three different plants.

Catalytic Oxidation of Mercury

Gaseous oxidized mercury is more easily removed from flue gas than gaseous elemental mercury, particularly in FGD units. Thus, maximizing oxidized mercury in the flue gas is an effective strategy for control of emissions in APCDs. Commercial SCR catalysts used at coal-fired power plants for NOx control are good mercury oxidation catalysts. Measurements of mercury speciation after full-scale SCRs showed that substantial oxidation of elemental mercury can take place across the catalyst [233, 234]. This has been observed in bench-scale experiments (see, for example, [235-241]) either using simulated flue gas or in slipstream reactors using actual flue gas [242,243].

In the SCR, V2O5 catalyst adsorbs Hg0, where it reacts with HCl to form HgCl2. A reaction scheme was proposed by Madsen [241] as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Steps (1) through (5) represent a Mars-Maesson redox mechanism for the catalytic oxidation of elemental mercury. Vanadium is a transition metal that can be found in several different oxidation states, which facilitates the oxidation of elemental mercury. In well-controlled laboratory experiments, the SCR catalyst has been shown to reduce gaseous oxidized mercury to Hg0(g) [241, 244], but this has not been observed in full-scale plants. Most of the research in this area has been carried out using Cl as the halogen, but bromine and iodine have also been shown to promote Hg oxidation across SCR catalysts [240, 244, 245].

In the SCR elemental mercury must compete with ammonia for access to catalytic sites, and the ammonia concentration at the SCR inlet is several orders of magnitude greater than the Hg concentration in the gas. It has been observed that the presence of ammonia in the flue gas inhibits the oxidation of elemental mercury [242] and can also cause oxidized Hg to be reduced to elemental Hg [241, 244]. In SCR reactors, ammonia concentration decreases inside the catalyst from the inlet to the outlet as it reacts with NOx. Thus, Hg oxidation increases along the flue gas path within the SCR reactor. Models of mercury oxidation across SCR catalyst have incorporated these effects, as well as the importance of the pore structure of the catalysts on mercury oxidation [246-248].

While V2O5 is the active agent in most SCR catalysts at coal-fired power plants, the catalysts contain other metal oxides as substrates (Al2O3, TiO2) or modifying additives (WO3, MoO3). These other metal oxide components of the catalyst can also affect Hg oxidation [232].

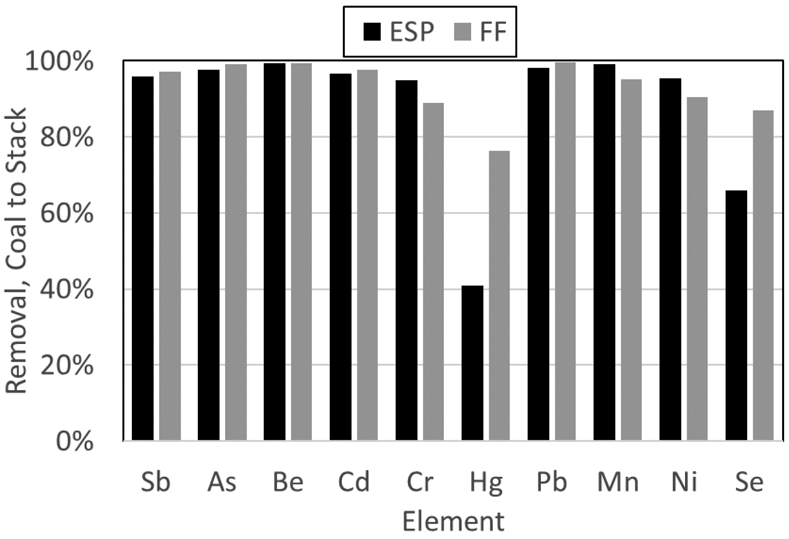

Particulate Control Devices

All modern coal-fired boilers have PM control devices, which can, in some cases, affect the behavior of certain TEs. Two primary PM control devices are used in coal-fired boilers: ESPs and fabric filters. ESPs remove particles by first charging the particles with an electric discharge and then subjecting the charged particles to an electric field, which induces the charged particles to move to a collection surface. Once the particles are collected, there is limited interaction between the gas and the particles. Helble [86] surveyed reported emissions of TEs from U.S. power plants (all equipped with ESPs) sampled in the 1990s. With the exception of As, Se, and Hg, the emission rates of TEs could be modeled adequately using the rate of emissions of particulate matter from the ESP.

In a fabric filter, all the gas passes through a porous material, which collects the ash in a thin layer (or filter cake). After sufficient ash accumulates, the filter cake is removed. A key difference between ESPs and fabric filters is that in a fabric filter, the flue gas is in intimate contact with fly ash removed from previously flue gas until the ash is removed, which can be many hours. In this regard, fabric filters are similar to fixed bed reactors, and there can be physical or chemical interaction between the flue gas and the ash, which does not occur in ESPs.