Abstract

Sialocele is an uncommon condition in cats. The treatment of choice for sublingual sialocele is excision of the ipsilateral mandibular and sublingual salivary gland/duct complex. Lateral and ventral cervical approaches have been described for mandibular-sublingual sialoadenectomy; however, the transoral approach, described here, has never been reported in cats. Ranula in the present case was likely caused by an inadvertent trauma of the sublingual duct during resection of a sublingual lesion performed by the referring veterinarian. The definitive surgery consisted of mass removal and sialoadenectomy through a unique oral approach. The surgery was effective without complications encountered after 6 months of follow-up.

Key clinical message:

This article reports a novel, transoral approach, for mandibular and sublingual sialoadenectomy in the cat. This approach decreases the surgical time and prevents recurrence of the mucocele.

Résumé

Approche trans-orale pour la sialo-adénectomie mandibulaire et sublinguale chez un chat. La sialocèle est une maladie rare chez les chats. Le traitement de choix pour la sialocèle sublinguale est l’excision du complexe glandes salivaires/canal salivaire ipsilatéral mandibulaire et sublingual. Des approches cervicales latérales et ventrales ont été décrites pour la sialo-adénectomie mandibulaire-sublinguale; cependant, l’approche trans-orale, décrite ici, n’a jamais été rapportée chez les chats. Dans le cas présent, la ranula a probablement été causée par un traumatisme involontaire du canal sublingual lors de la résection d’une lésion sublinguale réalisée par le vétérinaire référent. La chirurgie définitive consistait en un enlèvement de masse et une sialo-adénectomie par une approche orale unique. La chirurgie a été efficace sans complications rencontrées après 6 mois de suivi.

Message clinique clé :

Cet article rapporte une nouvelle approche trans-orale pour la sialo-adénectomie mandibulaire et sublinguale chez le chat. Cette approche diminue le temps chirurgical et empêche la récidive de la mucocèle.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Sialocele is frequently encountered in dogs but is rare in cats (1). Salivary mucocele, also called sialocele, is a subcutaneous or submucosal collection of saliva surrounded by reactive tissue due to extravasation of saliva as a result of discontinuity along the salivary gland-duct complex (2). The gland which is most frequently affected is the sublingual gland, formed by both a posterior monostomatic part in contact with the mandibular gland, with which it shares the same capsule, and an anterior polystomatic part (2–5). The duct of the mandibular gland passes along the superficial surface of the sublingual gland and then runs alongside the sublingual duct up to the oral cavity (4). In 1/3 of dogs, these glands share one common duct opening that exits into the buccal cavity at the level of the ipsilateral buccal floor, lateral to the sublingual frenulum (3). In the remaining dogs and in cats there are 2 separate duct openings (3,6).

In cats, the collection of saliva originating from the sublingual gland/duct is more often sublingual (ranula). Other locations similar to those in dogs include cervical and pharyngeal sialoceles.

Diagnosis of mucocele is based on history and clinical signs. Following centesis, the fluid that is obtained is a dense, honey-colored or blood-stained highly viscous fluid of low cellularity on cytologic examination (2).

Treatment for sublingual sialocele includes excision of the affected mandibular and sublingual salivary gland/duct complex (2,7,8). The mandibular gland is removed even when it is not affected because of its intimate anatomic association with the sublingual gland (2). Concurrent marsupialization of the ranula into the oral cavity has been suggested (2). Ventral and lateral approaches have been described for mandibular and sublingual sialoadenectomy (7–9), but a transoral approach has never been reported in cats; this approach is described herein.

Case description

A 12-year-old, castrated male Persian cat living indoors and weighing 3 kg was referred for further investigation and treatment of an oral mass/swelling, located at the left side of the buccal floor, below the tongue and first observed 4 wk earlier. Other reported clinical signs were dysphagia and drooling.

Three weeks before presentation to our clinic, the cat underwent fine-needle aspiration of the sublingual lesion; cytology was suggestive of a malignant mesenchymal tumor. A marginal resection was attempted by the referring veterinarian; histological diagnosis at that time was suggestive of a reactive cystic wall lined by normal fibroblasts. After surgery, an acute swelling of the left side of the buccal floor developed. The day after this surgery the fluid-filled swelling was still present and was drained by needle aspiration by the referring veterinarian. The fluid aspirated was viscous, honey-colored, and of low cellularity by cytologic examination. One week later the cystic lesion reappeared and the case was referred to our clinic.

On clinical examination, the cat was alert, but mildly dehydrated, and had a body condition score of 3/9. A direct oral inspection revealed a right-sided tongue deviation caused by a non-painful, 25 × 15 × 12 mm pedunculated, exophytic, and pinkish lesion localized on the left side of the buccal floor, lateral to the sublingual frenulum and medial to the first 2 premolar teeth. This lesion appeared surrounded by a fluid-filled dilatation consistent with a ranula (Figure 1a, b).

Figure 1.

a — Oral cavity. Note the right-sided tongue deviation caused by the lesion localized on the left side of the buccal floor, lateral to the sublingual frenulum and medial to the first 2 premolar teeth. b — Image showing the left side of the buccal floor (white star). The lesion is medial to the premolars and leans over the ranula (white arrow). c — Left side clipped neck of the cat. The left mandibular and sublingual glands are enlarged and may be palpated caudal to the mandibular angle, leaning lateral to jugular vein. d — Left buccal floor after the lesion has been removed. Note the glandular ducts (white star) clamped with the aid of fine curved hemostatic forceps.

On palpation, the left salivary mandibular complex appeared enlarged (Figure 1c) compared to the contralateral side; the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. A signed owner consent for the surgical treatment of both conditions, the sublingual mucocele and the sublingual lesion, was obtained.

The cat was premedicated with methadone (Eptadone 10 mg/mL; L. Molteni & C. dei F.lli Alitti Società di Esercizio S.p.a., Firenze, Italy), 0.2 mg/kg body weight (BW), IV, and anesthesia was induced with propofol (Propovet 10 mg/mL; Zoetis Italia S.r.l., Rome, Italy), 4 mg/kg BW, IV. Following endotracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane in oxygen.

The endotracheal tube was secured to the right side of the tongue to facilitate left-sided maneuvers during surgery. The cat was placed in sternal recumbency, with the head fixed to the surgical table with the help of a gauze tie; gauzes were also applied caudal to the superior and inferior canine teeth and fixed to the surgical table to keep the cat’s mouth open. Diluted chlorhexidine digluconate (0.2%) (Clorexisan 0.2%; Ogna Laboratori Farmaceutici S.r.l., Monza-Brianza, Italy) was used for local disinfection of the oral cavity. Finally, a sterile surgical drape with a hole was adapted around the mouth of the cat, to avoid gross contamination.

A mucosal elliptical incision was made around the base of the lesion base and saliva was aspirated. The incision involved all the left buccal floor, starting 1 cm rostral to the mandibular angle and extending rostrally just caudal to the mandibular symphysis, leaving the alveolar mucosa and the frenulum intact; the incision was made with 1 to 2 cm margins of healthy mucosa. The mass was resected through both sharp and blunt dissection. The excised lesion was placed in formalin for histologic investigation. Bleeding was controlled through electrocauterization.

Since the left buccal floor mucosa was almost completely removed, the sublingual-mandibular ducts were exposed and easily identified (Figure 1d); they were grasped with a pair of hemostatic forceps and pulled cranially. Then, a progressive blunt dissection was made around the ducts in an aboral direction using Metzenbaum scissors. During dissection, the chorda tympani nerve, derived from the lingual nerve and passing backward along the ducts to supply the glands with parasympathetic fibers (4), was identified and preserved.

Digital palpation and gentle ductal cranial traction allowed for easy identification of the sublingual mandibular gland complex on the caudal floor of the mouth, just medial to the angle of the mandible, with the interposition of the digastric muscle and oral mucosa. By blunt dissection through the digastric muscle, which was ventrally retracted with the aid of a thin curved hemostatic forceps (Figure 2a), access to the gland complex was gained. The salivary gland complex was freed of surrounded tissue and further dissected by incision and retraction of the capsule.

Figure 2.

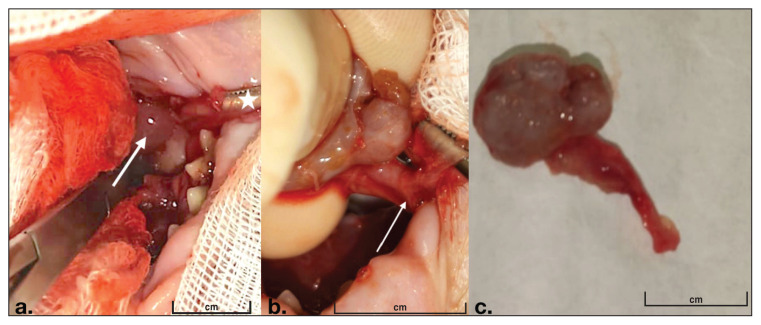

a — Caudal left buccal floor after blunt dissection around the glandular ducts (white star). The digastric muscle is ventrally retracted with the aid of a thin curved hemostatic forceps, to expose the mandibular and sublingual glands capsule (white arrow). b — The mandibular and sublingual glands-ducts complex is freed from surrounding tissues. Note the chorda tympani nerve still intact (white arrow). c — Complete mandibular and sublingual glands-ducts complex after removal.

Once isolation of the gland-duct complex was complete (Figure 2b), the chorda tympani nerve was cut. The entire complex was submitted for histologic evaluation (Figure 2c). The surgical wound was closed by placement of 4-0 poliglecaprone 25 suture material (Monocryl, Ethicon; J&J Medical N.V., Courcelles, Belgium) in a simple interrupted pattern.

Finally, an esophageal feeding tube was placed to manage feeding for the next 6 d. The cat recovered uneventfully and received robenacoxib (Onsior 6 mg; Elanco Italia S.p.a., Firenze, Italy), 2 mg/kg BW, PO, q24h and cefalexin (Icfvet granulare 50 mg/mL; I.C.F., Ind. Chimica Fine SRL, Palazzo Pignano (CR), Italy), 20 mg/kg BW, IV, q12h, for 5 postoperative days. Antimicrobial therapy was used to decrease the odds of esophageal tube stoma site infection, since it was reported to occur in 12.1% of cats that underwent esophageal tube placement in a recent study (10).

Drooling and dysphagia resolved within 2 postoperative days. Two days after surgery, feed was offered and the cat was able to eat spontaneously. Six days after surgery, the buccal mucosa had healed, the esophageal tube was removed, and the cat was discharged.

On histological examination, the sublingual lesion was marked by chronic ulcerative stomatitis with proliferation of granulation tissue. The possible related cause may have been a chronic infectious event (without any evidence of an etiological agent) or a previous trauma. The pathological tissue appeared completely excised. The mandibular and sublingual glands-ducts complex had chronic lymphoplasmocellular and neutrophilic interstitial and periductal sialadenitis with mild interstitial fibrosis and chronic inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding the extra-glandular salivary ducts. This finding was compatible with sialocele and inflammation of the glandular tissue which may be secondary to retention of glandular secretion and/or ascending bacterial infection.

The cat was re-examined at 2 wk (Video 1, available from the authors), 1 mo, and 2 mo (Video 2, available from the authors) after surgery and was in good health. At the time of writing, 6 mo after surgery, the owner reported that the cat was free of clinical signs.

Discussion

Mucocele is a rare condition in the cat; it usually originates from the sublingual salivary glands (ranula) (1,2,11), as in the cat in the present report. The etiopathogenesis of mucocele remains unknown. The most likely cause is trauma, but other causes include sialolithiasis, foreign bodies, inflammation, and neoplasia (2). In experimental studies in dogs, either ligation of or trauma to the sublingual salivary gland or duct may result in atrophy of the gland or rapid healing of the salivary duct, thus negating trauma as a possible cause of mucocele (12). However, in cats, ligation of the sublingual duct led to extravasation of saliva in more than 50% of the cases in another study (4), suggesting ductal obstruction as a possible cause in this species. The cat in the present report was affected by a ranula concurrent with sialadenitis, which occurred acutely after the reactive tissue removal performed by the referring veterinarian. However, brachycephalic cats may often be affected by dental occlusion disorder which may cause continuous trauma, also along the inferior mucosa, finally resulting in proliferative and/or ulcerated lesions, that may even be confused with malignant tumors (13,14). Based on this, it may be speculated that the first lesion operated on by the referring veterinarian was just a reactive lesion, probably associated with self-trauma, as no history of an external trauma was reported by the owner. It is also likely that the development of the ranula was caused by ligation of or trauma to the glandular ducts during the first surgery, with consequent collection of saliva and inflammation of the sublingual gland, as proposed by the histopathology report.

The treatment of choice for sublingual sialocele is excision of the affected mandibular and sublingual salivary gland/duct complex; marsupialization of the ranula has also been suggested (2). For mandibular and sublingual sialoadenectomy, ventral and lateral cervical approaches have been reported (7–9), although a transoral approach has apparently never been reported in cats. An oral approach for the removal of remnants of the sublingual gland in case of sialocele recurrence in 4 dogs has been described (15). In this case report, sialoadenectomy along with an en bloc left buccal floor mucosa removal was performed (Figure 1d) through a single transoral approach. This was facilitated by the fact that the removal of the lesion was associated with the excision of most ventral buccal mucosa, thus exposing the salivary ducts (Figure 1d). Blunt dissection as close as possible to the ducts helped to avoid any damage to the surrounding soft tissues and lingual nerve. Bleeding was controlled effectively through electrocauterization. The procedure was effective and did not result in any intraoperative or postoperative complications within 6 mo after surgery.

This case shows that, with sublingual sialocele in cats, a transoral approach may be feasible, thus reducing the surgical time and allowing a complete glandular-ductal complex removal. However, it should be noted that an excessive cranial traction on the ducts may cause their rupture, thus forcing the surgeon to proceed with a lateral or a ventral approach. Complications after sialoadenectomy are uncommon and include seroma, infection, and recurrence (15,16). The reported mucocele recurrence after sialoadenectomy is 5% and usually results from incomplete removal of the affected glands (2). Recurrence was not seen in this cat 6 mo after surgery, as this approach allowed a complete glandular and ductal removal. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Spangler WL, Culbertson MR. Salivary gland disease in dogs and cats: 245 cases (1985–1988) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;198:465–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritter MJ, Stanley BJ. Salivary glands. In: Johnston SA, Tobias KM, editors. Veterinary Surgery Small Animal. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2018. pp. 1653–1663. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grandage G. Functional anatomy of the digestive system. In: Slatter D, editor. Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders; 1993. pp. 499–521. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison JD, Garrett JR. Mucocele formation in cats by glandular duct ligation. Archs Oral Biol. 1972;17:1403–1414. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(72)90099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans H, De Lahunta A. Digestive apparatus and abdomen. In: De Lahunta A, Edward Evans H, editors. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog. 4th ed. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013. p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiefer KM, Garret JD. Salivary mucoceles in cats: A retrospective study of seven cases. Vet Med. 2007;102:582–585. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papazoglou LG, Tzimtzimis E, Rampidi S, Tzimitris Nicolaos. Ventral approach for surgical management of feline sublingual sialocele. J Vet Dent. 2015;32:201–203. doi: 10.1177/089875641503200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MM. Lateral approach for surgical management of feline sublingual sialocele. J Vet Dent. 2015;32:198–200. doi: 10.1177/089875641503200313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsioli V, Brellou G, Siziopkou C, et al. Sialocele in the cat. A report of 2 cases. J Hellenic Vet Med Soc. 2015;66:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breheny CR, Boag A, Le Gal A, et al. Esophageal feeding tube placement and the associated complications in 248 cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:1306–1314. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassanino J, Palierne S, Blondel M, Reynolds BS. Sublingual sialocele in a cat. JFMS Open Rep. 2019;26:5. doi: 10.1177/2055116919833249. :2055116919833249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulland TJ, Archibald J. Salivary mucoceles in dogs. Can Vet J. 1964;5:109–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gracis M, Molinari E, Ferro S. Caudal mucogingival lesions secondary to traumatic dental occlusion in 27 cats: Macroscopic and microscopic description, treatment and follow-up. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17:318–328. doi: 10.1177/1098612X14541264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mestrinho LA, Louro JM, Gordo IS, et al. Oral and dental anomalies in purebred, brachycephalic Persian and exotic cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253:66–72. doi: 10.2460/javma.253.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsioli V, Papazoglou LG, Basdani E, et al. Surgical management of recurrent cervical sialoceles in four dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2013;54:331–333. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedlund CS. Salivary mucoceles. In: Fossum TW, editor. Small Animal Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby; 2007. pp. 367–372. [Google Scholar]