Abstract

Background

Many hospitals seek to increase patient safety through interprofessional team-trainings. Accordingly, these trainings aim to strengthen important key aspects such as safety culture and communication. This study was designed to investigate if an interprofessional team-training, administered to a relatively small group of nurses and physicians would promote a change in healthcare professionals’ perceptions on safety culture and communication practices throughout the hospital. We further sought to understand which safety culture aspects foster the transfer of trained communication practices into clinical practice.

Methods

We conducted a pre-post survey study using six scales to measure participants’ perceptions of safety culture and communication practices. Mean values were compared according to profession and participation in training. Using multiple regression models, the relationship between safety culture and communication practices was determined.

Results

Before and after the training, we found high mean values for all scales. A significant, positive effect was found for the communication practices of the physicians. Participation in the training sessions played a variably relevant role in the communication practices. In addition, the multiple regression analyses showed that specific safety culture aspects have a cross-professional influence on communication practices in the hospital.

Conclusions

This study suggest that interprofessional team-trainings of a small group of professionals can successfully be transferred into clinical practice and indicates the importance of safety culture aspects for such transfer processes. Thus, we recommend the consideration of safety culture aspects before starting a training intervention.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-021-06137-5.

Keywords: Patient safety, Interprofessional team training in hospitals, Implementation, Communication in health care, Safety culture

Background

Effective collaboration and communication in interprofessional teams are key to high quality and safety in healthcare delivery. Studies have shown that poor team communication contributes to potentially avoidable adverse events and patient harm [1–4]. Moreover, complex patient care involves clinicians from multiple specialties and professional backgrounds and requires frequent handovers and transitions. Thus, skills in interprofessional team communication are fundamental to ensuring effective information transmission along the patient care process

Communication practices such as 2-way-communication (closed-loop communication), briefings, and feedback can support interprofessional communication and hence contribute to improved quality and safety of care [5–7]. 2-way-communication is a communication technique in which a received verbal message is followed by an explicit confirmation to the sender of the message. This method is already used in high-risk sectors, such as the army and aviation, to avoid misunderstandings and to confirm actions taken. Briefings are used in interprofessional teams to create an equal level of information, discover unsolved problems, and establish or maintain a common understanding of the situation. This should minimize the risk of possible loss of information [8]. Feedback is used to reflect on the performance of the team as well as the individual performance, and can lead to alternative solutions in the future, or strengthen existing good practices.

Team-trainings were shown to be effective at improving communication processes in healthcare [9, 10], especially if following a holistic, organisation-wide and interprofessional approach [11]. However, such approaches are challenging to implement and depend heavily on organisational culture [12–14]. Different professions in the hospital setting usually have different education and qualifications, possess different roles and use different professional jargons, all of which may lead to different perspectives on patient safety [15, 16]. Consequently, small-scale local trainings of communication skills, especially delivered for individual professional groups, may have limited impact on interprofessional collaboration..

In 2015, the University Hospital Muenster launched an interdepartmental, interprofessional training project to strengthen safety culture and train employees in communication skills. The project group, ‘Safety Training’, therefore developed interprofessional team-training courses for relatively small groups of nurses and physicians (9% of overall participants), representing 17 participating departments with a total of approximately 2000 employees. These representatives of nurses and physicians from participating departments served as so-called ‘champions’ to transfer training contents into clinical practice [17]. However, it is unclear how many trained champions are required to initiate change at the department level and which cultural aspects support a transfer of training content into clinical practice.

In patient safety research, a culture of safety is generally considered an important factor for improving healthcare delivery [18–21]. Safety culture is a multidimensional construct [22], previous studies identified different safety culture aspects as important facilitators for successful implementation of quality improvement initiatives. Leadership [23, 24], teamwork [25, 26], and psychological safety [27] were identified as strong catalysts to successfully implement quality improvement strategies such as interprofessional trainings. Thus, we seek to understand whether these aspects of safety culture support the interdisciplinary training of patient safety champions in the hospital setting.

Research questions/objectives

Firstly, this study aims to investigate, if the interprofessional team-training of champions can be successfully transferred into clinical practice. Thus, we examine whether there are changes in professionals’ perceptions on safety culture aspects and communication practices before and after the intervention and whether the results differ between training participants and nonparticipants.

Second, we seek to understand which safety culture aspects serve to foster the transfer of trained communication practices into clinical practice. In this regard, we seek to understand the relevance of nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions on safety culture aspects and its influence on trained communication practices. Results from this study will help to understand if trained champions can make a difference at the department level and what cultural aspects are instrumental in making that happen.

Methods

Study context

Between January and November 2016, the project group conducted a series of interprofessional team-trainings of clinical managers and champions. The University Hospital Muenster comprises about 9600 employees working in 42 departments. Of these, 17 departments (with approximately 2000 employees) participated in team-trainings. These departments were chosen based on either their high patient flow, their risky profile for patient care or their time-critical processes and/or complex interprofessional composition (e.g. operating areas, intensive care units, and emergency outpatient departments).

Training concept and implementation

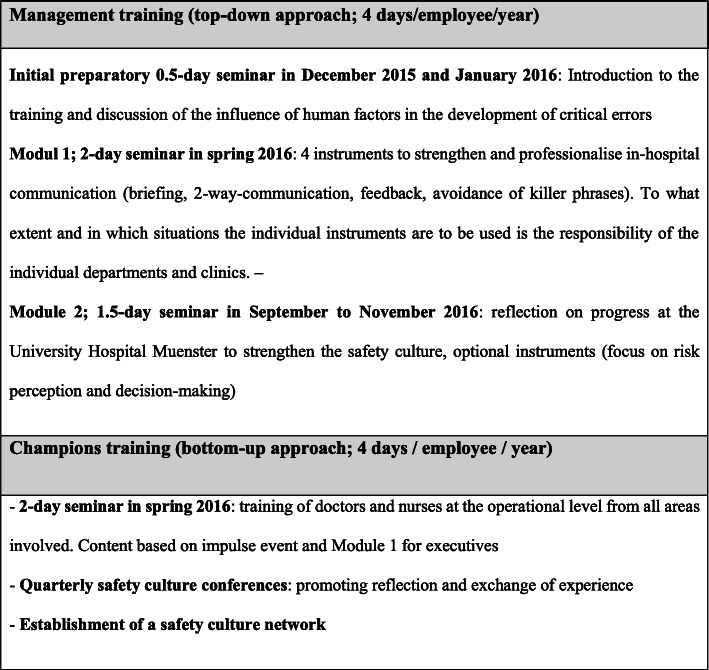

The interprofessional team-trainings aimed to increase employees’ awareness of safety culture within the organisation [27] and to improve the use of standardised communications practices (i.e. 2-way-communication, briefing, and feedback). Descriptions and examples are shown in Fig. 1 [28–30].

Fig. 1.

Description of the key aspects of communication and clarification using methods and examples of the study

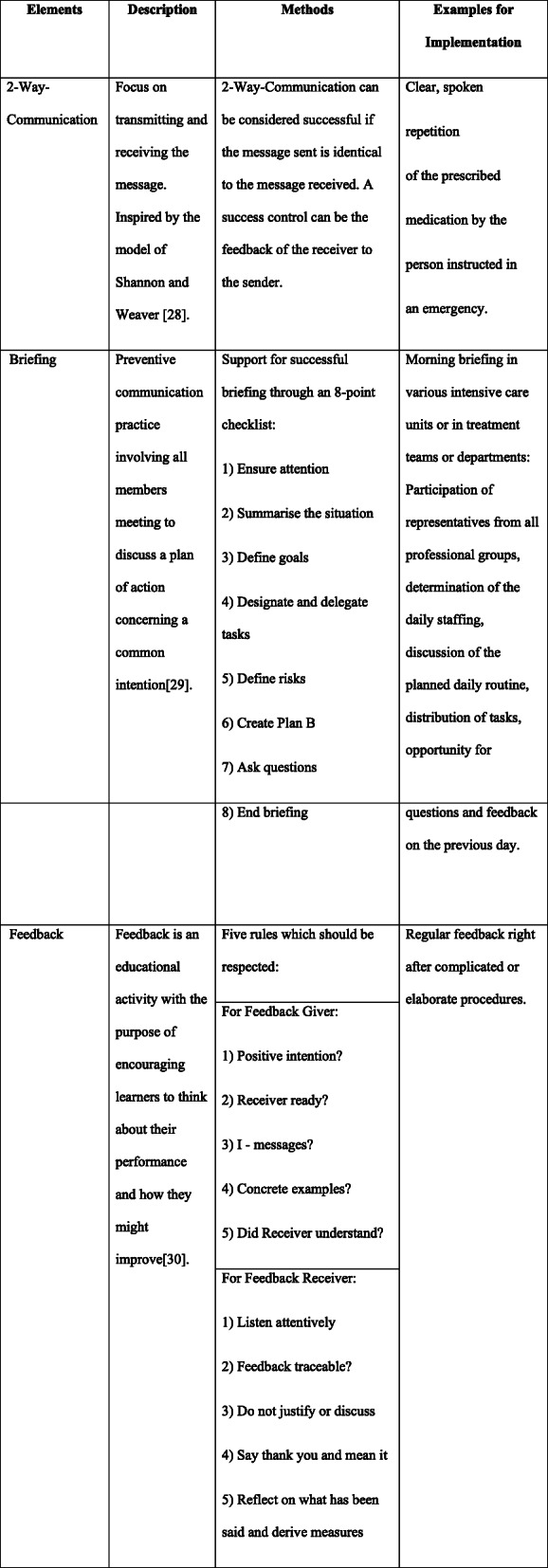

The trainings have been conducted at both the (1) clinical management level and (2) frontline professional level. Clinical managers are responsible for translating senior executives’ visions into routine practices, facilitating efforts in specific improvement strategies, promoting innovative practices, and supporting frontline professionals’ activities for these strategies [31]. Concurrently, this provides an opportunity for transferring frontline needs and information upwards, thus drawing senior executives’ attention to specific requirements at local level [31]. Because frontline professionals are familiar with local requirements for implementing selected communication tools, they served as champions for actions taken in respective departments. Thus, the trainings compiled management trainings for 108 physicians and nurses with executive functions and champion trainings for 71 frontline professionals, reaching a total of 9% of staff in participating departments.

Trainings were conducted in two modules covering the communication practices and providing a set of communication tools that could support local implementations of actions. The first training module (two days) included communication practices and communication tools to support local implementation (e.g. structured briefings, check-backs, avoidance of ‘killer’ phrases). In the second module, training participants were introduced to the concept of safety culture and invited to reflect on implementation progress and share experiences across departments.

As part of an organisational learning process, the latter phase enabled participants – especially the champions – to learn from each other on successful local strategies for transferring training contents into local practice. The trained champions were introduced to possible ways of transferring training contents into practices (e.g. small team trainings, weekly briefings or introduction of checklists). Based on the local needs and context, they could decide how to pass on the contents of the trainings. In the second half of the study phase, the project management initiated additional complementary actions at local level (e.g. feedback workshops, observations of handovers, supervisions) in order, to assess the current status, identify problems and support the transfer from training to practice. An overview of all trainings is displayed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Overview and content of trainings

Data collection procedure

To evaluate the impact of the interprofessional team-training on the perception of safety culture and communication practices, the Institute of Patient Safety conducted a pre-post online survey of all employees in participating departments. In January and February 2016, before the first training module, approximately 2000 clinicians were invited to participate in a baseline survey (t0) – including the 179 participants of the training intervention. The second survey (t1) was conducted six months after completion (of the second training module in September to November 2016). All participants were invited via email and received reminders two and four weeks after the initial invitation. Participation was voluntary and due to data security aspects, survey links at t0 and t1 were sent independently to all employees to enter data anonymously. Thus, we were not able to link participants in pre- and post-surveys nor to request information on non-responders.

Measures

The safety culture aspects Supervisor Expectations (four items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.75) and Teamwork Within Units (four items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.77) were measured with two scales from the German version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSPSC) [32, 33]. Answers for these two scales were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Psychological Safety (seven items Cronbach’s alpha 0.84) was measured using the German adaptation from Edmondson [34, 35]. Answers were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all to 5 = absolutely true).

In order to measure communication practices, we developed three scales capturing the main communication practices covered in the trainings: 2-Way-Communication (three items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88), Briefing (three items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) and Feedback (five items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83). Answers were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all to 5 = absolutely true).

To cover information on sociodemographic characteristics, participants were asked about their profession (1 = nurse, 2 = physician, 3 = other), leadership position (0 = no, 1 = yes), and their participation in the interprofessional team-training (0 = no, 1 = yes).

An overview of scales and items used in the analysis is provided in an additional table (Additional Table 1). The entire German pre-post survey is available on request by contacting the last author.

Statistical analyses

Prior to analyses, cases with more than 30% missing in survey items were excluded from the data set to ensure sufficient data quality. Negatively-worded items were reverse coded for further analyses.

In pre-analyses, we calculated frequencies on participants’ profession, leadership position and participation in interprofessional team-training. Other professional groups besides nurses and physicians were not considered in the further calculations due to their limited numbers. We calculated descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations (SD)) for all six scales (three for safety culture and three for communication) in pre- and post-measures separately for nurses and physicians. In order to identify difference in perceptions of trained and non-trained professionals, we additionally calculated descriptive statistics and used Mann-Whitney-U-tests to analyse changes of means from t0 to t1 of these six scales for training participants and nonparticipants separately for nurses and physicians, by solely using answers given at t1. Significance level was set at p < 0.05. The Cohen-test was used to determine the strength of the significant results in Mann-Whitney-U-test. Results 0.2 ≤ r < 0.5 were considered weak, from 0.5 ≤ r < 0.8 medium and r > 0.8 strong [36].

In order to identify relationships between safety culture aspects and communication practices, we used the Spearman test. Analyses were conducted separately for nurses and physicians.

Finally, we investigated which specific perceptions of safety culture aspects influence the perceptions on communication practices in nurses as well as physicians by running stepwise multiple regression analyses per each of the three communication practices (2-Way-Communication, Briefing and Feedback) as dependent variable and safety culture aspects as independent variable. Regression models were conducted separately for nurses and physicians and points in time. We used multiple linear regression with backwards selection and set the significance level at 5% (p < 0.05). We calculated regression coefficient (β), explained variance (R2), and the corresponding effect size (f2) for each model. Effects 0.02 ≤ f2 < 0.15 were considered small, 0.15 ≤ f2 < 0.35 medium and f2 ≥ 0.35 strong [37]. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics V.25.

Results

Of 2038 and 2045 employees invited in 2016 (t0) and in 2017 (t1), 569 (27.92%) and 402 (19.66%) participated in the online survey. After removing cases with more than 30% missing items, 528 (t0) and 366 (t1) cases were included in further analyses. Of these cases, 30.30% were physicians at t0 (25.68% at t1) and 58.90% nurses at t0 (63.11% at t1). At both measurement points, about a quarter of the participants indicated having leadership functions. At t1, after completion of trainings, the percentage of respondents who stated that they participated in trainings was 33.61% Table 1 provides an overview of participant characteristics at t0 and t1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics in t0 (2016) and t1 (2017)

| t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Participants of the study | ||

| Number of employees at the departments | 2038 | 2045 |

| Total of participants | 569 (27.92) | 402 (19.66) |

| Total of participants after excluding Missing > 30% | 528 (25.91) | 366 (17.90) |

| Profession | ||

| Nurses | 311 (58.90) | 231 (63.11) |

| Physicians | 160 (30.30) | 94 (25.68) |

| Others | 57 (10.80) | 41 (11.20) |

| Missing | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Leadership position | ||

| Yes | 134 (25.38) | 88 (24.04) |

| No | 391 (74.05) | 274 (74.86) |

| Missing | 3 (0.57) | 4 (1.09) |

| Participation in training | ||

| Yes | 123 (33.61) | |

| No | 242 (66.12) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.27) | |

Changes in nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions on safety culture aspects and communication practices

Means and standard deviations of all safety culture and communication scales at t0 and t1, and Mann-Whitney-U-tests are presented separately for nurses and physicians in Table 2. Overall, t0 results showed relatively high values for both nurses and physicians in the three safety culture aspects Supervisor Expectations, Teamwork Within Units and Psychological Safety, with physicians generally rating all three scales more positively compared to nurses. At t1, we found a slight decrease in mean values for Supervisor Expectations and Teamwork Within Units for both professions. For Psychological Safety, we observed a decrease for physicians while nurses reported slightly more positive perceptions of Psychological Safety at t1. However, none of these differences were significant.

Table 2.

Safety culture aspects and communication scales by professions and study periods/ training participation

| Profession | Nurses | Physicians | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study periods t0 (2016)/ t1(2017) |

t0 (2016) Mean (SD) |

t1(2017) Mean (SD) |

Δ |

t0 (2016) Mean (SD) |

t1(2017) Mean (SD) |

Δ |

| Safety Culture Aspects | ||||||

| Supervisor Expectations | 3.42 (0.72) | 3.38 (0.71) | −0.04 | 3.58 (0.72) | 3.47 (0.78) | −0.11 |

| Teamwork Within Units | 3.42 (0.60) | 3.36 (0.61) | −0.06 | 3.64 (0.69) | 3.54 (0.78) | −0.10 |

| Psychological Safety | 3.61 (0.66) | 3.69 (0.61) | 0.08 | 3.68 (0.67) | 3.67 (0.66) | −0.01 |

| Communication Practices | ||||||

| 2-Way-Communication | 3.69 (0.94) | 3.65 (0.91) | −0.04 | 3.19 (0.96) | 3.52 (0.84) | 0.33** |

| Briefing | 3.15 (0.86) | 3.27 (0.79) | 0.12 | 3.46 (0.87) | 3.74 (0.79) | 0.28* |

| Feedback | 2.92 (0.81) | 2.86 (0.83) | −0.06 | 3.07 (0.79) | 3.22 (0.79) | 0.15 |

|

Training participants/ non-participants (at t1) |

non-participants Mean (SD) |

participants Mean (SD) |

Δ |

non-participants Mean (SD) |

participants Mean (SD) |

Δ |

| Safety Culture Aspects | ||||||

| Supervisor Expectations | 3.36 (0.72) | 3.44 (0.71) | 0.08 | 3.34 (0.81) | 3.70 (0.70) | 0.36 |

| Teamwork Within Units | 3.33 (0.62) | 3.43 (0.61) | 0.10 | 3.42 (0.84) | 3.72 (0.62) | 0.30 |

| Psychological Safety | 3.64 (0.63) | 3.80 (0.55) | 0.16 | 3.52 (0.72) | 3.91 (0.46) | 0.39** |

| Communication Practices | ||||||

| 2-Way-Communication | 3.70 (0.92) | 3.54 (0.90) | −0.16 | 3.44 (0.90) | 3.64 (0.72) | 0.20 |

| Briefing | 3.26 (0.79) | 3.30 (0.81) | 0.04 | 3.54 (0.83) | 4.07 (0.58) | 0.53** |

| Feedback | 2.83 (0.85) | 2.92 (0.78) | 0.09 | 3.09 (0.84) | 3.46 (0.65) | 0.37* |

Notes: Means, standard deviations (SD) and deltas (Δ) for all six scales of safety culture aspects and communication practices regarding points in time and training participation. Mann-Whitney-U-test significance: *p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01

Concerning communication practices, nurses rated 2-Way-Communication in the t0-survey, higher than physicians. The values of 2-Way-Communication for nurses decreased slightly in the post evaluation (t1). By comparison, the mean value of 2-Way-Communication for physicians increased clearly from t0 to t1 and approached the mean value of nurses at t1. The Mann-Whitney-U-test confirmed a significant difference in pre-post evaluations of 2-Way-Communication by physicians (U = 5598.50 p < 0.01); (Table 2). The effect size according to Cohen was r = 0.2. The mean values of Briefing showed high values for both professions in both points in time and the values were more positive for nurses and physicians at t1 than at t0. However, only the result for physicians reached statistical significance (U = 6177.60, p = 0.02). The effect size, according to Cohen, was r = 0.15. Feedback showed lowest values for both professions and at both measurements. At t1, nurses’ perceptions resulted in lower mean values compared to t0, while the physicians’ ratings increased. However, differences were not significant.

Comparing the mean values for training participants and nonparticipants at t1, results showed generally higher mean values in all 6 scales for participating physicians (Table 2). For nurses who had participated in the trainings, mean values were higher on 5 out of the 6 scales (except for 2-Way-Communication) compared to nurses who had not participated. However, none of these differences reached statistical significance. For physicians, all mean values of training participants were higher than those of nonparticipants. These differences proved to be significant for Psychological Safety (U = 673.500, p = 0.008), Briefing (U = 614.000, p = 0.002) and Feedback (U = 704.000, p = 0.017).

Relationship between safety culture aspects and communication practices

Results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 3. We found higher correlations between all aspects of safety culture and communication practices at t1 than at t0 for physicians. However, we did not identify uniform changes in correlations of nurses’ perceptions at t1.

Table 3.

Correlation between the scales of safety culture aspects and communication practices for both professional groups

| Nurses | t0 (2016) | t1(2017) | ||||

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1) Supervisor Expectations | – | 0.38*** | 0.44*** | 0.08 | 0.31*** | 0.52*** |

| 2) Teamwork Within Units | 0.39** | – | 0.51*** | 0.08 | 0.25*** | 0.28*** |

| 3) Psychological Safety | 0.43** | 0.56*** | – | 0.19** | 0.35*** | 0.53*** |

| 4) 2-Way-Communication | 0.12* | 0.19*** | 0.18** | – | 0.41*** | 0.36*** |

| 5) Briefing | 0.34*** | 0.39*** | 0.35*** | 0.39*** | – | 0.55*** |

| 6) Feedback | 0.40*** | 0.48*** | 0.47*** | 0.28*** | 0.53*** | – |

| Physicians | t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) | ||||

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1) Supervisor Expectations | – | 0.50*** | 0.54*** | 0.25* | 0.51*** | 0.55*** |

| 2) Teamwork Within Units | 0.44** | – | 0.65*** | 0.44*** | 0.54*** | 0.65*** |

| 3) Psychological Safety | 0.57*** | 0.54*** | – | 0.41*** | 0.67*** | 0.61*** |

| 4) 2-Way-Communication | 0.20* | 0.20* | 0.19* | – | 0.55*** | 0.50*** |

| 5) Briefing | 0.44*** | 0.52*** | 0.53*** | 0.40*** | – | 0.64*** |

| 6) Feedback | 0.54*** | 0.52*** | 0.52*** | 0.32*** | 0.67*** | – |

Notes: Spearman test for linear correlation between Safety culture aspects and Communication practices

Below the diagonal = t0, above the diagonal = t1; Higher correlation in either t0 or t1 highlighted in bold; significance level: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Impact of safety culture aspects on nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions on 2-way-Communiaction, briefing and feedback

Results of multiple regressions analyses are presented in Table 4. 2-Way-Communication: For nurses, we found a significant effect of Psychological Safety on 2-Way-Communication at both measurement points; t0 (β = 0.21, p < 0.05) and t1 (β = 0.23, p < 0.05). The explained variance remained low and decreased from 5% to 2% at t1 (p < 0.05 f2 = 0.14). Similarly, for physicians we found significant effects of Psychological Safety on 2-Way-Communication at t0 (β = 0.33, p < 0.01) and Teamwork Within Units on 2-Way-Communication at t1 (β = 0.50, p < 0.001). The explained variance increased from 5% at t0 to 20% at t1 corresponding to a strong effect (f2 = 0.50).

Table 4.

Influence of safety culture aspects on communication practices for points in time and professions

| Nurses | ||||||

| 2-Way-Communication | Briefing | Feedback | ||||

| Year | t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) | t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) | t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) |

| Variables (β) | ||||||

| Supervisor Expectations | – | – | 0.23*** | 0.20* | 0.22*** | 0.42*** |

| Teamwork Within Units | – | – | 0.33*** | – | 0.35*** | – |

| Psychological Safety | 0.21* | 0.23* | 0.24** | 0.41*** | 0.33*** | 0.53*** |

| Explained variance R2 | 0.05*** | 0.02* | 0.23*** | 0.17*** | 0.34*** | 0.40*** |

| N | 309 | 228 | 208 | 227 | 309 | 228 |

| Physicians | ||||||

| 2-Way-Communication | Briefing | Feedback | ||||

| Year | t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) | t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) | t0 (2016) | t1 (2017) |

| Variables (β) | ||||||

| Supervisor Expectations | – | – | 0.17 | – | 0.32*** | 0.25* |

| Teamwork Within Units | – | 0.50*** | 0.31** | – | 0.31** | 0.52*** |

| Psychological Safety | 0.33** | – | 0.40*** | 0.79*** | 0.26** | – |

| Explained variance R2 | 0.05** | 0.20*** | 0.33*** | 0.44*** | 0.41*** | 0.48*** |

| N | 158 | 91 | 159 | 91 | 157 | 91 |

Note: Multiple regression analysis with calculated regression coefficient (β) and explained variance for all six models. Independent variables: Supervisor Expectations, Teamwork Within Units, Psychological Safety

Dependent variables: 2-Way-Communication, Briefing, Feedback

Significance level: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001

Briefing: For nurses, all three safety culture aspects (Supervisor Expectations (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), Teamwork Within Units (β = 0.33, p < 0.001), Psychological Safety (β = 0.24, p < 0.01)) showed significant positive effects on Briefing at t0. At t1, Psychological Safety (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and Supervisor Expectations (β = 0.20, p < 0.05) had significant effects on Briefing, with Psychological Safety showing the strongest effect. The explained variance for the entire model decreased (R2 t0 = 23%; R2 t1 = 17%), resulting in a strong effect of f2 = 0.45. Concerning physicians, Teamwork Within Units (β = 0.31, p < 0.01) and Psychological Safety (β = 0.40, p < 0.001) were positively associated with Briefing at t0. However, at t1, only Psychological Safety showed a significant positive effect (β = 0.79, p < 0.001) on Briefing and considerably increased compared to t0. The explained variance for the entire model increased from R2 = 33% to R2 = 44% in t1, corresponding to a strong effect f2 = 0.89.

Feedback: For nurses, multiple regression at t0 showed again that all predictors ((Supervisor Expectations (β = 0.22, p < 0.001), Teamwork Within Units (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) and Psychological Safety (β = 0.33, p < 0.001)) were positively associated with Feedback. At t1, effects of 2 predictors reached statistical significance: Supervisor Expectations (β = 0.42, p < 0.001) and Psychological Safety (β = 0.53, p < 0.001). The explained variance for the entire model increased (R2 t0 = 34%; R2 t1 = 40%) resulting in a strong effect f2 = 0.82. For physicians, all 3 safety culture aspects showed significant effects on Feedback, while the regression coefficient for Teamwork Within Units increased to β = 0.52 (p < 0.001) at t1. In contrast, the positive effect of Supervisor Expectations decreased from β = 0.32 (p < 0.001) at t0, to β = 0.25 (p < 0.05) at t1. Psychological Safety showed no effect at t1. The explained variance increased to 48% at t1 (p < 0.01, f2 = 0.96).

Discussion

Our results suggest that the interprofessional team-training for a small group of participants (9% of total staff in participating departments) resulted in changes in professionals’ perceptions with regard to communication practices. This may support a possibility for a successful transfer of training components into clinical practice by the means of champions. Nevertheless, the team training seemed to have more effect on communication practices than on aspects of safety culture. These findings are similar to those of Hefner et al., with the plausible explanation that team training addressed communication practices more likely than the influencing factors of supervisors and management [38]. A second explanation is provided by the study of Thomas and Galla, in which a change in aspects of safety culture presented itself much later than the change in communication practices [39]. One approach in order to solve this problem would be further training and data collection over a longer period of time.

The comparison of training participants and non-participants provided interesting results. When it comes to physicians, training participants had significantly higher scores compared to non-participants, which may provide evidence for the positive training effects. In contrast to this, no significant results could be observed when it comes to nurses. This leads to the assumption that the intervention had fewer effects on nurses than on physicians. One possible reason for this result could be different expectations and roles due to different professional backgrounds and hierarchical levels that already have been observed in other studies [40]. They may influence the perception of communication practices and safety culture aspects. For all physicians, the perception of communication practices showed significant changes at t1, indicating a successful transfer supported by the champions for this professional group. The significant differences between the participating and non-participating physicians suggest that the transfer could still be optimized. One opportunity to further strengthen the transfer could be to increase the number of trained champions.

The non-significant and at times negative changes we observed may be explained partially by response-shift bias [41], which occurs when the respondents’ understanding of the constructs in question improves between pre- and post-test, contributing to a more critical evaluation of practices than before and consequently lower scores.

We identified several differences in perceptions of nurses and physicians before and after the training. Physicians generally rated safety culture and communication aspects higher than nurses did, except for Psychological Safety after the training and 2-Way-Communication at both points in time. These results are in line with previous studies [2, 42, 43]. Reasons for these differences may lie in different understandings of the underlying concept of safety culture and communication practices or in different management structures in nurses’ and physicians’ clinical work [42].

Regarding our second research question, descriptive results showed that physicians who already had higher values in safety-culture aspects compared to nurses before the training, had significantly higher values in two of three trained communication practices (2-Way-Communication, Briefing) after the training. This supports our theory that a high understanding of safety culture promotes the success of interprofessional team-training. Beyond these descriptive results, we identified Psychological Safety as the most important factor influencing all three communication practices for the nurses before and even stronger after the training. We found similar effects for physicians in Briefing. Results are comparable to a study by Tucker et al. [44], who identified psychological safety as an important aspect for implementing quality improvement practices. Teamwork Within Units was identified as the second most important factor, as we found very strong effects of teamwork on Briefing to 2-Way Communication for physicians after the training, indicating a high relevance of teamwork for these communication practices. These results are related to previous findings, which suggest that culture is required as an important facilitator towards successful implementation of quality-improvement strategies [26].

In summary, our study has indicated that content of interprofessional training of champions can successfully be transferred into practice at the local level. Also, certain aspects of safety culture can promote this transfer of training content.

Strengths and limitations

This study analysed changes in nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of aspects of safety culture and communication practices using champions to transfer training contents into clinical practice. However, we found several limitations in the study. First, within this study, we used a pre-post design with one measurement before interprofessional team-trainings and the second measurement six months after completion of the trainings. Thus, our findings are limited to the two measurement points. In order to draw conclusions on long-term effects and sustainability of these interprofessional team-trainings, it would have been necessary conducting repetitive trainings and collecting further data (e.g. in combining a data collection on these specific topics with legally-required annual employee surveys) [45]. Second, due to data security requirements, data from participants of our pre- and post-surveys were not matched. Therefore, no other personal characteristics such as age or gender were collected. This limits in consequence our analysis to two separate evaluations of the two measurement points and less detailed analyses regarding personal characteristics. Thus, if possible, future studies should consider the possibility of matching data and conducting more detailed analyses on interaction effects regarding further personal characteristics. Third, we encountered a reduced response rate at the second measurement, a common problem in pre-post survey studies. Nevertheless, with about a 28% response rate at t0 and about 20% at t1, this study resulted in a sample size that is comparable to similar health services research studies, this was sufficient for the intended statistical analyses. Fourth, dependent and independent variables in the regression models were measured with the same survey, gathering subjective views of professionals and increasing the risk of common method variance bias [46].

Finally, with the complex structures and processes in a university hospital, it is possible that confounding variables remain undiscovered, but may have influenced the results.

Conclusion

Results of this study suggest that interprofessional team-trainings of champions have a positive impact on routine clinical practice; as well they indicate the importance of safety culture aspects for successful transfer. For this, we recommend measuring the safety culture of the participating teams before starting an intervention. Future studies should address the question of how many champions are needed to achieve the greatest possible effect in the entire employee base.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Used scales and their single item’s mean values and standard deviations (SD).

Acknowledgements

We would especially like to thank all employees of the University Hospital Muenster who agreed to participate in this project and the respondents for their effort and time to complete the surveys. We acknowledge the support of the hospital management and the workers´ council as well as the efforts of the local study coordinators in facilitating data collection.

Abbreviations

- GDPR

General Data Protection Regulation

- HSPSC

Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

AH and TM designed the scientific study and were responsible for the data collection. TG, MK and FN coordinated the interprofessional team trainings at the University Hospital Muenster and were responsible for the supervision of champions. JS and NG performed the statistical analysis and received valuable feedback by the other authors. JS and AH drafted the manuscript. NG and TM contributed with valuable feedback and modifications to the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Data for presented study are part of a project funded by the University Hospital Muenster and have been analysed within the framework of JS’s PhD thesis without funding. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

Because of data security considerations, data from this study will not be made available in the public domain. However, data will be used by students of both project partners for their theses. Data will be stored in accordance with national and regional data security standards. Data are available from the last author upon reasonable request and with permission of University Hospital of Muenster.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee at University Hospital Bonn (#389/15). Data collection was complied with confidentiality requirements according to German law. Informed consent was sought from all participants in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and electronically indicated. This procedure has been approved by the ethics committee. All data were analysed anonymously.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Awad SS, Fagan SP, Bellows C, Albo D, Green-Rashad B, De La Garza M, et al. Bridging the communication gap in the operating room with medical team training. Am J Surg. 2005;190:770–774. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills P, Neily J, Dunn E. Teamwork and communication in surgical teams: implications for patient safety. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies JM. Team communication in the operating room. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:898–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brindley PG, Reynolds SF. Improving verbal communication in critical care medicine. J Crit Care. 2011;26:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(SUPPL. 1):85–90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salas E, Wilson KA, Murphy CE, King H, Salisbury M. Communicating, coordinating, and cooperating when lives depend on it: tips for teamwork. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:333–341. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lingard L, Whyte S, Espin S, Ross Baker G, Orser B, Doran D. Towards safer interprofessional communication: constructing a model of “utility” from preoperative team briefings. J Interprof Care. 2006;20:471–483. doi: 10.1080/13561820600921865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabøl LI, Østergaard D, Mogensen T. Outcomes of classroom-based team training interventions for multiprofessional hospital staff. A systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e27 LP–e27e27. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver SJ, Dy SM, Rosen MA. Team-training in healthcare: a narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:359–372. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:149–154. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mardon RE, Khanna K, Sorra J, Dyer N, Famolaro T. Exploring relationships between hospital patient safety culture and adverse events. J Patient Saf. 2010;6:226–232. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181fd1a00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer S, Lin S, Falwell A, Baker L, Gaba D. Relationship of safety climate and safety performance in hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2008;44:399–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00918.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardt DCM. The relationship between patient safety culture and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Patient Saf. 2015;11:135–142. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foronda C, MacWilliams B, McArthur E. Interprofessional communication in healthcare: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;19:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: professional cultures as barriers. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(SUPPL. 1):188–196. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roeder N, Wächter C, Güß T, Klatthaar M, Schwalbe D, Würfel T. Patientensicherheit – eine Frage der Kultur. das Krankenhaus. 2016;8:668–675. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellings J, Schrooten W, Klazinga NS, Vleugels A. Improving patient safety culture. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2010;23:489–506. doi: 10.1108/09526861011050529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson HT, Teman FS, Connors HR. A safety culture transformation: its effects at a Children’s hospital. J Patient Saf. 2012;8:125–130. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31824bd744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morello RT, Lowthian JA, Barker AL, McGinnes R, Dunt D, Brand C. Strategies for improving patient safety culture in hospitals: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:11–18. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver SJ, Lubomksi LH, Wilson RF, Pfoh ER, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting a culture of safety as a patient safety strategy. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5_Part_2):369–374. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guldenmund FW. The nature of safety culture: a review of theory and research. Saf Sci. 2000;34:215–257. doi: 10.1016/S0925-7535(00)00014-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCaughey D, Halbesleben JRB, Savage GT, Simons T, McGhan GE. Safety leadership: extending workplace safety climate best practices across health care workforces. Adv Health Care Manag. 2013;14:189–217. doi: 10.1108/S1474-8231(2013)00000140013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schyve PM, Brockway M, Carr M, Giuntoli A, Mcneily M, Reis P. The joint commission guide to improving staff communication. 2nd ed. Joint Commission Resources; 2009.

- 25.Epstein N. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: a review. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:295. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.139612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes RG. Tools and strategies for quality improvement and patient safety. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leroy H, Dierynck B, Anseel F, Simons T, Halbesleben JRB, McCaughey D, et al. Behavioral integrity for safety, priority of safety, psychological safety, and patient safety: a team-level study. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97:1273–1281. doi: 10.1037/a0030076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948;27:379–423. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allard J, Bleakley A, Hobbs A, Vinnell T. “Who’s on the team today?” The status of briefing amongst operating theatre practitioners in one UK hospital. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:189–206. doi: 10.1080/13561820601160042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cantillon P, Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337:1292–1294. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pannick S, Sevdalis N, Athanasiou T. Beyond clinical engagement: a pragmatic model for quality improvement interventions, aligning clinical and managerial priorities. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:716–725. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gambashidze N, Hammer A, Brösterhaus M, Manser T. Evaluation of psychometric properties of the German hospital survey on patient safety culture and its potential for cross-cultural comparisons: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfeiffer Y, Manser T. Development of the German version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: Dimensionality and psychometric properties. Saf Sci. 2010;48:1452–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2010.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44:350. doi: 10.2307/2666999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety – development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:281. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;4:279–282. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hefner JL, Hilligoss B, Knupp A, Bournique J, Sullivan J, Adkins E, et al. Cultural transformation after implementation of crew resource management: is it really possible? Am J Med Qual. 2017;32:384–390. doi: 10.1177/1062860616655424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas L, Galla C. Building a culture of safety through team training and engagement. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:394–401. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-001011rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romijn A, Teunissen PW, De Bruijne MC, Wagner C, De Groot CJM. Interprofessional collaboration among care professionals in obstetrical care: are perceptions aligned? BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:279–286. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rohs FR, Langone CA, Coleman RK. Response shift bias: a problem in evaluating nutrition training using self-report measures. J Nutr Educ. 2001;33:165–170. doi: 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gambashidze N, Hammer A, Wagner A, Rieger MA, Brösterhaus M, Van Vegten A, et al. Influence of gender, profession, and managerial function on clinicians’ perceptions of patient safety culture. J Patient Saf. 2019;Publish Ah. 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Kristensen S, Hammer A, Bartels P, Suñol R, Groene O, Thompson CA, et al. Quality management and perceptions of teamwork and safety climate in European hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27:499–506. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tucker AL, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Implementing new practices: an empirical study of organizational learning in hospital intensive care units. Manag Sci. 2007;53:894–907. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.St. Pierre M, Gall C, Breuer G, Schüttler J. Does annual simulation training influence the safety climate of a university hospital?: Prospective 5-year investigation using dimensions of the safety attitude questionnaire. Anaesthesist. 2017;66:910–923. doi: 10.1007/s00101-017-0371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Used scales and their single item’s mean values and standard deviations (SD).

Data Availability Statement

Because of data security considerations, data from this study will not be made available in the public domain. However, data will be used by students of both project partners for their theses. Data will be stored in accordance with national and regional data security standards. Data are available from the last author upon reasonable request and with permission of University Hospital of Muenster.