ABSTRACT

Background

Glucocerebrosidase gene mutations are a common genetic risk factor for Parkinson's disease. They exhibit incomplete penetrance. The objective of the present study was to measure microglial activation and dopamine integrity in glucocerebrosidase gene mutation carriers without Parkinson's disease compared to controls.

Methods

We performed PET scans on 9 glucocerebrosidase gene mutation carriers without Parkinson's disease and 29 age‐matched controls. We measured microglial activation as 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 binding potentials, and dopamine terminal integrity with 18F‐dopa influx constants.

Results

The 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 binding potential was increased in the substantia nigra of glucocerebrosidase gene carriers compared with controls (Student t test; right, t = −4.45, P = 0.0001). Statistical parametric mapping also localized significantly increased 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 binding potential in the occipital and temporal lobes, cerebellum, hippocampus, and mesencephalon. The degree of hyposmia correlated with nigral 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 regional binding potentials (Spearman's rank, P = 0.0066). Mean striatal 18F‐dopa uptake was similar to healthy controls.

Conclusions

In vivo 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 PET imaging detects neuroinflammation in brain regions susceptible to Lewy pathology in glucocerebrosidase gene mutation carriers without Parkinson's. © 2020 The Authors. Movement Disorders published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, microglia, substantia nigra, glucocerebrosidase, positron emission tomography

The glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA) encodes the lysosomal hydrolase glucocerebrosidase. In the biallelic (homozygous or compound heterozygous) state, GBA mutations may cause Gaucher disease (GD) which leads to glucosylceramide accumulation in visceral organs and, in a minority of cases, the central nervous system (neuronopathic GD). GBA mutations are the most significant genetic risk factor for Parkinson's disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)1, 2, 3; however, penetrance is only 10%–30%.4, 5, 6 PD patients carrying a GBA mutation have an earlier disease onset and a higher risk of dementia. 7

At postmortem, α‐synuclein aggregations identical to those found in idiopathic PD 1 and DLB 8 are present in GBA‐PD subjects. Asymmetrically reduced striatal 18F‐dopa uptake,9, 10 striatal dopamine transporter binding,11, 12 and an altered striatal asymmetry index 13 have been reported in PD patients with GBA mutations. Conversely 123I‐isoflupane dopamine transporter uptake has been demonstrated to be upregulated in non‐PD GBA carriers compared with controls and is higher in GBA PD compared to idiopathic PD cases.14, 15 GBA mutation carriers without PD exhibit prodromal PD features,16, 17, 18, 19 which progress with time. 20

Glial activation has been demonstrated in postmortem PD brains.21, 22 Nigral microglial activation along with reduced striatal 18F‐Dopa uptake is present in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD). 23 It is also a feature of neuronopathic GD at postmortem 8 and in GD mouse models. 24 No studies have investigated in vivo the presence of brain microglial activation in GBA mutation carriers and related this to the presence of striatal dopaminergic dysfunction. We therefore measured 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 regional binding potentials (BPND) and 18F‐dopa Ki in GBA mutation carriers without evidence of Parkinson's disease.

Methods

Recruitment and Clinical Assessments

Between 2015 and 2016, 9 biallelic (homozygous or compound heterozygous) or heterozygous carriers of GBA mutations were recruited from University College London, UK (see Table 1 for characteristics). All subjects had exons 1–11 of the GBA gene sequenced (Table 1). Biallelic carriers had type 1 GD, whereas heterozygous carriers were drawn from GD kindreds. No subjects met PD (UK Brain Bank) diagnostic criteria, and none were genetically related. Two of 5 GD patients were receiving enzyme replacement therapy (ERT; velaglucerase 800 IU weekly and 4000 IU monthly) and 3 of 5 substrate reduction therapy (SRT: eligustat 84 IU twice daily in 2 of 3, miglustat 300 mg once daily in 1 of 3). Both SRT and ERT were administered throughout the duration of the study. Ethical approval was obtained from London, UK (10/H0720/21), and Midtjylland, Denmark (M‐2014‐397‐14), research ethics committees.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of control and GBA carrier groups

| Biallelic GBA (n = 5) | Heterozygous GBA (n = 4) | Combined GBA (n = 9) | 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 controls (n = 20) | 18F‐Dopa controls (n = 9) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.6 (2.9) | 63.3 (7.7) | 62.9 (2.9) | 66.8 (6.0) | 64.6 (3.6) | ||

| Male, % | 40.0 | 50.0 | 44.4 | 60.0 | 100.0 | ||

| UPSIT | 33.6 (1.1) | 31.5 (3.9) | 32.7 (2.7) | ||||

| MoCA | 27.4 (1.9) | 27.8 (2.2) | 27.6 (1.9) | ||||

| MDS UPDRS II | 2.0 (2.1) | 3.0 (3.6) | 2.4 (2.7) | ||||

| MDS UPDRS III | 12.8 (10.4) | 4.5 (2.4) | 9.1 (8.7) | ||||

| BDI | 2.6 (2.7) | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.2 (2.2) | ||||

| NMSS | 13.8 (9.2) | 17.0 (10.4) | 15.2 (9.3) | ||||

| RBDSQ | 2.0 (1.9) | 4.5 (2.4) | 3.1 (2.4) | ||||

| Mutations of GBA group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaucher disease | Enzyme replacement therapy | Substrate reduction therapy | |||||

| N370s/L444P a | Yes | No | Yes | ||||

| N370S/IVS2 + 1 a | No | No | Yes | ||||

| N370S/F216Y | Yes | Yes | No | ||||

| N370S/R359X b | Yes | No | Yes | ||||

| N370S/V447E | Yes | Yes | No | ||||

| RecNcil (L444P/A456P/V460V) a /wt | No | No | No | ||||

| N370S/wt | No | No | No | ||||

| N370S/wt | No | No | No | ||||

| V394L a /wt | No | No | No | ||||

| Clinical scores of GBA carriers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | MDS UPDRS II | MDS UPDRS III | MoCA | UPSIT | BDI | NMSS | RBDSQ |

| 1 | 0 | 2 | 30 | 37 | 4 | 15 | 7 |

| 2 | 0 | 3 | 25 | 30 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 30 | 35 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| 4 | 5 | 29 | 26 | 32 | 3 | 13 | 4 |

| 5 | 0 | 4 | 26 | 33 | 7 | 28 | 4 |

| 6 | 3 | 11 | 29 | 34 | 1 | 16 | 1 |

| 7 | 0 | 7 | 27 | 31 | 5 | 29 | 0 |

| 8 | 2 | 6 | 29 | 28 | 5 | 20 | 1 |

| 9 | 0 | 16 | 26 | 34 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

GBA, glucocerebrosidase; PD, Parkinson's disease; MDS UPDRS, Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; NMSS, Non‐Motor Symptoms Scale; MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; BDI, Beck's Depression Index; RBDSQ, REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Questionnaire.

For demographics, results are mean (SD).

Severe mutation of GBA carrier group.

Null mutation of GBA carrier group.

Each GBA carrier had 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 and 18F‐dopa PET, an MRI, and neurological examination. Prodromal PD features were rated with the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), Montreal cognitive assessment, RBD questionnaire (RBDSQ), PD Non‐Motor Symptoms Scale, the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS‐UPDRS) parts II and III, and Beck's Depression Inventory.

All scans and examinations were performed at Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark. GBA carrier PET findings were compared with in‐house PET data from 29 age‐matched healthy controls (20 had 11C‐[R]‐PK11195 BPND PET, and 9 had 18F‐dopa PET) recruited for a previously published study. 25 Assessments of control prodromal PD features were not available.

PET and MRI

We performed prespecified region‐of‐interest (ROI) analyses comparing GBA mutation carriers with controls. Selected ROIs were the substantia nigra (SN), putamen, and caudate for 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND and the putamen and caudate for 18F‐dopa Ki. We performed statistical parametric mapping (SPM) of 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 uptake across all brain voxels. Technical details of the PET and MRI scanning and analysis procedures are available in the supplementary materials.

Statistics

For the ROI analyses, statistical calculations and graphs were produced with Stata v14.2 software (StataCorp., College Station, TX). The 18F‐dopa Ki and 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND values from specified ROIs were compared in carrier and control groups using the Student t test (P < 0.05). When there was a significant difference in 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND between the GBA and control groups, secondary analyses correlating PD prodromal features with 11C‐(R)‐PK11195BPND were undertaken (Spearman's rank: all clinical scales were non normally distributed, P < 0.05). A Bonferroni correction was applied to all significant results.

Results

Participants

Participant characteristics are listed in Table 1. Nine GBA mutation carriers (5 biallelic and 4 heterozygous) were selected on the basis of their genotype and the absence of PD features. Two age‐matched control groups (20 for 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND PET and 9 for 18F‐dopa PET) were included in the final GBA analysis. Some GD patients had musculoskeletal problems typical of GD reflected in raised MDS UPDRS III scores, but these were not specific for PD. This reflects the limitations of the MDS UPDRS when used in the context of non‐PD comorbidities and applied to subjects without diagnosed PD. No participants had a bradykinetic or rigid syndrome on expert examination. There were no missing data.

Substantia Nigra 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND Is Increased in GBA+ Individuals Compared With Controls

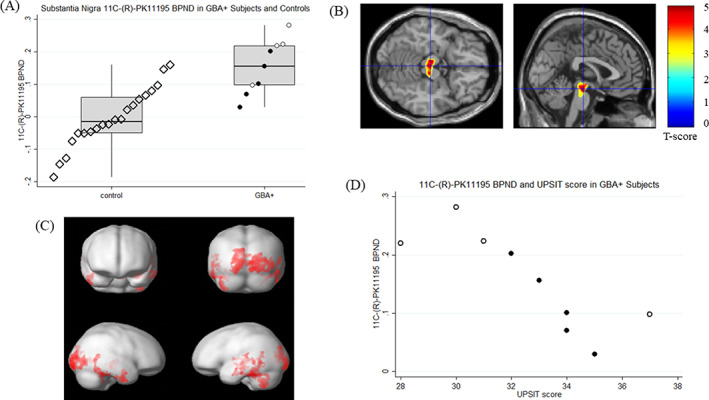

ROI analysis localized a significant increase in mean nigral 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND of the GBA carriers compared with controls (Student t test, t = −4.45, P = 0.0001; Tables S1 and S2). Statistical significance was retained after correction for multiple comparisons (Table S2). For the GBA mutation carriers, mean SN 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND was 0.15 ± 0.08 compared with −0.01 ± 0.09 for the control group (Table S1 and Fig. 1A). Interestingly, heterozygous carriers had disproportionately higher BPND than biallelic (GD) patients (Table S1 and Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Top left, box and dot plots of 11C‐PK11195 binding potential (BPND) in the substantia nigra of GBA+ heterozygous carriers (white circles), biallelic GBA+ carriers (black circles), and controls (hollow black diamonds). Please note data points are offset across x axis for ease of interpretation. Middle line is median, box is interquartile range. (B) Top right, 11C‐PK11195 binding potential (BPND) in GBA carriers > controls. Colored areas depicted on the single‐subject brain template illustrate clusters of voxels of 11C‐PK11195 binding potential (BPND) surviving P < 0.05 with family‐wise error rate (FWE) correction in the brain stem region of GBA+ carriers compared with control subjects. Non–brain stem clusters are masked. GBA, n = 9; controls, n = 20. (C) Bottom left, 11C PK11195 binding potential (BPND) in GBA carriers > controls. Red areas depicted on the brain surface template illustrate clusters of voxels of 11C‐PK11195 BPND surviving P < 0.05 with FWE correction in cortical regions of GBA+ carriers compared with control subjects. GBA+, n = 9; controls, n = 20. (D) Bottom right, scatterplots of 11C‐PK11195 BPND in the substantia nigra of GBA+ carriers against University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) score. GBA+ heterozygous carriers (white), biallelic GBA+ carriers (black).

11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND Correlates With Olfactory Deficit in GBA+ Individuals

There was a negative correlation between nigral 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND and UPSIT scores in GBA mutation carriers (Spearman's rank, P = 0.0066; Table S2 and Fig. 1D), which did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (Table S2).

Upregulated Cortical, Hippocampal, and Mesencephalon 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND in GBA+ Group

SPM‐localized clusters of voxels with significantly increased 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND in GBA carriers bilaterally in the occipital and temporal cortices, cerebellum, left hippocampus, and central and anterior mesencephalon (Table S3 and Fig. 1B,C). No brain regions showed reduced 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND compared with controls.

No Difference in Mean 18F‐Dopa Ki Between GBA+ and Control Participants

The GBA carriers showed no significant decreases in mean 18F‐dopa Ki across striatal ROIs compared with controls (Tables S1 and S2, Fig. S1). Two participants had putamen and/or caudate 18F‐dopa Ki more than 2 SDs below the control mean (Table S4). Greater variance in 18F‐dopa Ki (see Table S1) was seen in the GBA group (SD of 0.002 in the putamen and caudate compared with SD of 0.001 in controls). Post hoc analysis (Student t test) comparing the anterior, medial, and posterior putamen did not show any significant mean differences between GBA mutation carriers and controls.

No Correlation Between Nigral 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND and 18F‐Dopa Ki in GBA+ Group

There was no association between the SN 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND and putamen or caudate (Table S2) 18F‐dopa Ki in the GBA group.

Discussion

Our data indicate that both heterozygous and biallelic GBA mutation carriers can have increased 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND in brain regions susceptible to Lewy body formation. 26 It is unclear whether this is a cytotoxic or neuroprotective process. Only 10%–30% of GBA mutation carriers will develop PD. It is therefore unlikely that all the participants in this study will convert. Which GBA carriers are likely to progress to PD and the mechanisms underlying this conversion are of particular interest.

11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND values in the SN correlated with UPSIT scores, suggesting that those GBA carriers who have reduced olfactory function have higher nigral inflammation. Correlation of striatal 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND with age and MDS UPDRS III score has also been shown in early PD cases. 27

Despite mean nigral 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND being increased in the GBA group, no significant reduction in mean putamen 18F‐dopa uptake was seen. It is known that 18F‐dopa lacks the sensitivity to detect early dopaminergic dysfunction because of compensatory upregulation of dopa decarboxylase in the remaining terminals. Early reductions may be better detected with dopamine transporter markers.28, 29 Our finding of normal striatal F‐dopa uptake in GBA carriers may not necessarily equate to normal dopamine terminal function, although no GBA carrier exhibited clinical features of PD.

Interestingly 18F‐dopa Ki was more variable in the GBA group compared with controls. Recently, 184 nonmanifesting GBA carriers were reported to have increased dopamine transporter binding across striatal regions. 15 This is in line with an increase in striatal 18F‐dopa Ki found in a portion of our GBA+ cases. It has been reported that 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 binding to microglia “burns out” as amyloidosis in early Alzheimer's disease advances 30 but increases again as tau tangles form.31, 32 A biphasic trajectory could explain the lack of correlation between 18F‐dopa Ki and 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND in our data set.

Limitations

The relatively small sample size, its cross‐sectional design, and the unknown future disease status of GBA mutation carriers are limitations. We acknowledge that GBA mutations exhibit a variable penetrance and phenotype, in terms of both PD and GD. Reproducing these results in larger (ideally prospective) and more genotypically and phenotypically homogenous cohorts is needed. Nevertheless, we believe these are important and highly relevant pilot data that will inform the design of future studies.

The 11C‐PK11195 BPND has high nonspecific binding, which provides a lower specific‐to‐background PET signal ratio than newer markers of activated microglia; therefore, our results may underestimate glial activation. This study used 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND as a marker of the translocator protein (TSPO) expressed by the mitochondria of activated microglia, and, in contrast to newer TSPO tracers available, the binding is not influenced by the polymorphism of the TSPO expressed by individuals. The limitations of supervised cluster analysis in conditions with possible widespread microglial activation should also be acknowledged, as it could lead to an underestimation of 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND, particularly in small ROIs.

Three of 5 and 2 of 5 subjects were taking substrate reduction therapy or enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), respectively. The former is under evaluation as a PD neuroprotective agent (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02906020). ERT is not thought to cross the blood–brain barrier, although 1 report suggests a portion may. 33 We cannot exclude the possibility that the reduced nigral and putamen 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND in biallelic compared with heterozygous cases could represent suppression of glial activation by these drugs.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that GBA mutations are associated with microglial activation in Lewy‐susceptible brain regions in subjects without either a prodromal or clinical diagnosis of PD. Further studies are required to assess whether 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 BPND PET, (with or without additional biomarkers) can predict GBA carrier conversion to PD and striatal dopamine loss.

Author Contributions

The study was designed by S.M., M.S., A.S., D.B., and N.P. Patient identification and recruitment were carried out by S.M., A.S., A.M., and D.H. Imaging was carried out by M.S., R.H., and P.P.. Image analysis was carried out by M.S. Data analysis was carried out by S.M. The article was primarily written by S.M., M.S., and A.S. with contributions from A.M., D.H., N.P., and D.B. and reviewed by all the authors.

Full Financial Disclosures for the Past 12 Months

S.M. has received grant funding from the National Institute of Health Research, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, and fees for consulting from GLG consulting, Horama and Centogene. D.H. has received fees for research from Sanofi and Takeda, administered through UCL consultants with benefits to research in lysosomal storage diseases. D.B. has received grant funding from Horizon 2020, Danish Council for Independent Research, and Lundbeck Foundation. In the last 12 months A.H.V.S. has received funding from the Medical Research Council, H2020 Parkinson's UK, and the Cure Parkinson Trust. He is an employee of UCL. He has served as a consultant for Prevail Therapeutics. N.P. has received grants funding from the Independent Research Fund Denmark, Danish Parkinson's Disease Association, Parkinson's UK, MRC – Center of Excellence in Neurodegeneration (CoEN) network award, GE Healthcare Grant, Multiple System Atrophy Trust, Weston EU Joint Program Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND), EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, Italian Ministry of Health, and Honoria for consultancy from Britannia, Boston Scientific, Benevolent AI, and Bial. D.J.B. has received grant funding from the Independent Research Fund Denmark, Lundbeck Foundation, Danish Parkinson's Disease and Alzheimer's Associations, Horizon 2020, and GE Healthcare. M.S., P.P., and A.M. have nothing to disclose.

Data and Materials Availability

Study data are available on reasonable request.

Supporting information

Table S1. Summary table of positron emission tomography (PET) binding potentials (BPND) for 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 and influx constants (Ki) for 18F‐dopa in control and GBA+ groups

Table S2. Summary table of analyses

Table S3. Summary table of statistically significant statistical parametric mapping findings for 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 regional binding potentials (BPND)

Table S4. The 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 regional binding potentials (BPND) and 18F‐dopa influx constants (Ki) greater than 2 SD below the control group mean with UPSIT and MDS UPDRS III assessment scores in GBA+ group

Figure S1. Box and dot plots of 18F‐dopa Ki in (A) the caudates of heterozygous GBA+ carriers (white circles), biallelic GBA+ carriers (black circles), and controls (hollow black diamonds). Please note data points are offset across x axis for ease of interpretation; and (B) in the putamina of heterozygous GBA+ carriers (white circles), biallelic GBA+ carriers (black circles), and controls (hollow black diamond). Please note data points are offset across x axis for ease of interpretation. For (A) and (B), middle line is median, box is interquartile range.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members of the lysosomal storage unit of the Royal Free Hospital for their help and assistance in patient recruitment.

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: There were no conflicts of interest. S.M. is a National Institute for Health Research–supported clinical lecturer.

Funding agencies: This research was funded by the Medical Research Council (MR/J009660/1 COEN 1), MRC Experimental Medicine (MR/M006646/1), and Joint Programme Neurodegenerative Disease Research (MR/N028651/1) and was supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. SM is a National Institute for Health Research supported clinical lecturer. Independent Research Fund Denmark, Lundbeck Foundation, Kattan Trust (285), and Joint Programme Neurodegenerative Disease Research (MR/N028651/1). Funders had no role in data analysis and did not have access to the data set.

References

- 1. Neumann J, Bras J, Deas E, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in clinical and pathologically proven Parkinson's disease. Brain 2009;132(Pt 7):1783–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lesage S, Anheim M, Condroyer C, et al. Large‐scale screening of the Gaucher's disease‐related glucocerebrosidase gene in Europeans with Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20(1):202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mata IF, Samii A, Schneer SH, et al. Glucocerebrosidase gene mutations: a risk factor for Lewy body disorders. Arch Neurol 2008;65(3):379–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anheim M, Elbaz A, Lesage S, et al. Penetrance of Parkinson disease in glucocerebrosidase gene mutation carriers. Neurology 2012;78(6):417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosenbloom B, Balwani M, Bronstein JM, et al. The incidence of parkinsonism in patients with type 1 Gaucher disease: data from the ICGG Gaucher registry. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2011;46(1):95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neudorfer O, Giladi N, Elstein D, et al. Occurrence of Parkinson's syndrome in type I Gaucher disease. QJM 1996;89(9):691–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cilia R, Tunesi S, Marotta G, et al. Survival and dementia in GBA‐associated Parkinson's disease: the mutation matters. Ann Neurol 2016;80(5):662–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wong K, Sidransky E, Verma A, et al. Neuropathology provides clues to the pathophysiology of Gaucher disease. Mol Genet Metab 2004;82(3):192–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kraoua I, Stirnemann J, Ribeiro MJ, et al. Parkinsonism in Gaucher's disease type 1: ten new cases and a review of the literature. Mov Disord 2009;24(10):1524–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goker‐Alpan O, Masdeu JC, Kohn PD, et al. The neurobiology of glucocerebrosidase‐associated parkinsonism: a positron emission tomography study of dopamine synthesis and regional cerebral blood flow. Brain 2012;135(Pt 8):2440–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kono S, Ouchi Y, Terada T, et al. Functional brain imaging in glucocerebrosidase mutation carriers with and without parkinsonism. Mov Disord 2010;25(12):1823–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sunwoo M‐K, Kim S‐M, Lee S, Lee PH. Parkinsonism associated with glucocerebrosidase mutation. J Clin Neurol 2011;7(2):99–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McNeill A, Wu R‐M, Tzen K‐Y, et al. Dopaminergic neuronal imaging in genetic Parkinson's disease: insights into pathogenesis. PLoS One 2013;8(7):e69190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simuni T, Brumm MC, Uribe L, et al. Clinical and dopamine transporter imaging characteristics of leucine‐ rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) and Glucosylceramidase Beta (GBA) Parkinson's disease participants in the Parkinson's progression markers initiative: a cross‐sectional study. Mov Disord. 2020;35(5):833–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simuni T, Uribe L, Cho HR, et al. Clinical and dopamine transporter imaging characteristics of non‐manifest LRRK2 and GBA mutation carriers in the Parkinson's progression markers initiative (PPMI): a cross‐sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2020;19(1):71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McNeill A, Duran R, Proukakis C, et al. Hyposmia and cognitive impairment in Gaucher disease patients and carriers. Mov Disord 2012;27(4):526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mullin S, Beavan M, Bestwick J, et al. Evolution and clustering of prodromal parkinsonian features in GBA carriers. Mov Disord. 2019;34(9):1365–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Avenali M, Toffoli M, Mullin S, et al. Evolution of prodromal parkinsonian features in a cohort GBA mutation‐positive individuals: a 6‐year longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat 2019;90(10):1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beavan M, McNeill A, Proukakis C, et al. Evolution of prodromal clinical markers of Parkinson disease in a GBA mutation‐positive cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(2):201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berg D, Postuma RB, Adler CH, et al. MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2015;30(12):1600–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirsch EC, Hunot S, Hartmann A. Neuroinflammatory processes in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2005;11(Suppl 1):S9–S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hirsch EC, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease: a target for neuroprotection? Lancet Neurol 2009;8(4):382–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stokholm MG, Iranzo A, Østergaard K, et al. Assessment of neuroinflammation in patients with idiopathic rapid‐eye‐movement sleep behaviour disorder: a case‐control study. Lancet Neurol 2017;16(10):789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mistry PK, Liu J, Yang M, et al. Glucocerebrosidase gene‐deficient mouse recapitulates Gaucher disease displaying cellular and molecular dysregulation beyond the macrophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(45):19473–19478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parbo P, Ismail R, Hansen KV, et al. Brain inflammation accompanies amyloid in the majority of mild cognitive impairment cases due to Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2017;140(7):2002–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsuboi Y, Uchikado H, Dickson DW. Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies with reference to striatal pathology. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007;13(Suppl 3):S221–S224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ouchi Y, Yoshikawa E, Sekine Y, et al. Microglial activation and dopamine terminal loss in early Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 2005;57(2):168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adams JR, van Netten H, Schulzer M, et al. PET in LRRK2 mutations: comparison to sporadic Parkinson's disease and evidence for presymptomatic compensation. Brain 2005;128(12):2777–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sossi V, de la Fuente‐Fernández R, Nandhagopal R, et al. Dopamine turnover increases in asymptomatic LRRK2mutations carriers. Mov Disord 2010;25(16):2717–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. team TCI, Lagarde J, Sarazin M, et al. Early and protective microglial activation in Alzheimer's disease: a prospective study using 18 F‐DPA‐714 PET imaging. Brain 2016;139(4):1252–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fan Z, Brooks DJ, Okello A, Edison P. An early and late peak in microglial activation in Alzheimer's disease trajectory. Brain 2017;140(3):792–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gerhard A, Pavese N, Hotton G, et al. In vivo imaging of microglial activation with [11C](R)‐PK11195 PET in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2006;21(2):404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vogler C, Levy B, Grubb JH, et al. Overcoming the blood‐brain barrier with high‐dose enzyme replacement therapy in murine mucopolysaccharidosis VII. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102(41):14777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Summary table of positron emission tomography (PET) binding potentials (BPND) for 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 and influx constants (Ki) for 18F‐dopa in control and GBA+ groups

Table S2. Summary table of analyses

Table S3. Summary table of statistically significant statistical parametric mapping findings for 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 regional binding potentials (BPND)

Table S4. The 11C‐(R)‐PK11195 regional binding potentials (BPND) and 18F‐dopa influx constants (Ki) greater than 2 SD below the control group mean with UPSIT and MDS UPDRS III assessment scores in GBA+ group

Figure S1. Box and dot plots of 18F‐dopa Ki in (A) the caudates of heterozygous GBA+ carriers (white circles), biallelic GBA+ carriers (black circles), and controls (hollow black diamonds). Please note data points are offset across x axis for ease of interpretation; and (B) in the putamina of heterozygous GBA+ carriers (white circles), biallelic GBA+ carriers (black circles), and controls (hollow black diamond). Please note data points are offset across x axis for ease of interpretation. For (A) and (B), middle line is median, box is interquartile range.