Abstract

Aims

Tafamidis is an effective treatment for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR‐CM) in the Tafamidis in Transthyretin Cardiomyopathy Clinical Trial (ATTR‐ACT). While ATTR‐ACT was not designed for a dose‐specific assessment, further analysis from ATTR‐ACT and its long‐term extension study (LTE) can guide determination of the optimal dose.

Methods and results

In ATTR‐ACT, patients were randomized (2:1:2) to tafamidis 80 mg, 20 mg, or placebo for 30 months. Patients completing ATTR‐ACT could enrol in the LTE (with placebo‐treated patients randomized to tafamidis 80 or 20 mg; 2:1) and all patients were subsequently switched to high‐dose tafamidis. All‐cause mortality was assessed in ATTR‐ACT combined with the LTE (median follow‐up 51 months). In ATTR‐ACT, the combination of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular‐related hospitalizations over 30 months was significantly reduced with tafamidis 80 mg (P = 0.0030) and 20 mg (P = 0.0048) vs. placebo. All‐cause mortality vs. placebo was reduced with tafamidis 80 mg [Cox hazards model (95% confidence interval): 0.690 (0.487–0.979), P = 0.0378] and 20 mg [0.715 (0.450–1.137), P = 0.1564]. The mean (standard error) change in N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide from baseline to Month 30 was −1170.51 (587.31) (P = 0.0468) with tafamidis 80 vs. 20 mg. In ATTR‐ACT combined with the LTE there was a significantly greater survival benefit with tafamidis 80 vs. 20 mg [0.700 (0.501–0.979), P = 0.0374]. Incidence of adverse events in both tafamidis doses were comparable to placebo.

Conclusion

Tafamidis, both 80 and 20 mg, effectively reduced mortality and cardiovascular‐related hospitalizations in patients with ATTR‐CM. The longer‐term survival data and the lack of dose‐related safety concerns support tafamidis 80 mg as the optimal dose.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01994889; NCT02791230.

Keywords: Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy, Clinical trial, Biomarkers, Mortality

Design of ATTR‐ACT and the LTE and reduction in all‐cause mortality with tafamidis 80 mg/61 mg compared with tafamidis 20 mg

Introduction

Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR‐CM) is caused by the accumulation of wild‐type (ATTRwt) or variant (ATTRv) transthyretin (TTR) amyloid fibrils in the myocardium, leading to cardiomyopathy and symptoms of heart failure (HF). 1 ATTRwt typically has a late symptom onset (>60 years of age) with the majority of patients being male, while symptom onset in patients with ATTRv may occur at younger ages. 1 , 2 Specific TTR mutations, such as Val122Ile, Thr60Ala, Leu111Met, Ile68Leu, 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 are commonly associated with ATTR‐CM, but cardiomyopathy can occur with other mutations. For example, Val30Met is generally associated with polyneuropathy, but many patients also experience cardiac findings, including cardiomyopathy. 2 , 7 , 8 , 9

In this disease, dissociation of the tetrameric TTR into monomers is followed by a rapid misfolding and misassembling of the monomers into aggregates, with tetramer dissociation being the rate‐limiting step in TTR amyloid formation. 10 Tafamidis inhibits TTR dissociation into monomers by binding to the thyroxine‐binding sites, which stabilizes the tetramers, thereby preventing fibril formation, 11 , 12 , 13 and has been shown to slow the progression of peripheral neurologic impairment in transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTR‐PN). 10

The Tafamidis in Transthyretin Cardiomyopathy Clinical Trial (ATTR‐ACT) demonstrated that tafamidis (compared with placebo) improves survival, reduces cardiovascular (CV)‐related hospitalizations, and improves measures of function and health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with ATTR‐CM. 14 In ATTR‐ACT, patients were randomized in a 2:1:2 ratio to tafamidis 80 mg, tafamidis 20 mg, or placebo, and the primary analysis compared the pooled tafamidis (80 and 20 mg) treated group with the placebo group. 14 ATTR‐ACT was not designed to assess the relative efficacy of each dose of tafamidis. The 80 mg dose was included as it results in near maximal TTR stabilization 10 and, together with the 20 mg dose, enabled the assessment of adequately separated doses. 15 Higher doses of tafamidis were previously assessed in a randomized placebo‐controlled study in healthy subjects (n = 42), in which a single supra‐therapeutic dose of tafamidis (400 mg), with a maximum steady‐state tafamidis concentration approximately 7.5 times higher than with a clinical dose of 20 mg, was generally well tolerated. 16

Here we present the results of additional analyses of data from ATTR‐ACT and the long‐term extension study (LTE), separately comparing the safety and efficacy of the 80 and 20 mg doses of tafamidis with placebo, in addition to changes in biomarkers and survival data directly comparing the tafamidis 80 and 20 mg doses.

Methods

Study design and patients

The design of this phase 3, multicentre, international, three‐arm, parallel‐design, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomized study (ATTR‐ACT) has been published previously (NCT01994889). 14 , 15 Briefly, patients were eligible to enrol if they met the following criteria: (i) age ≥18 and ≤90 years with ATTR‐CM defined by the presence of either ATTRv or ATTRwt amyloid deposits; (ii) medical history of HF with at least one prior hospitalization due to HF, or clinical evidence of HF without hospitalization (volume overload or elevated intracardiac pressures) that required treatment with a diuretic; (iii) end‐diastolic intraventricular septal wall thickness >12 mm demonstrated by echocardiography; (iv) 6‐min walk test (6MWT) of >100 m; and (v) N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) concentration ≥600 pg/mL. Exclusion criteria included: (i) prior treatment with tafamidis; (ii) HF not due to ATTR‐CM (based on the opinion of the investigator); (iii) New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV; (iv) modified body mass index (BMI) <600 kg/m2·g/L (serum concentration of albumin multiplied by BMI); (v) estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <25 mL/min/1.73 m2; (vi) prior liver or heart transplantation; and (vii) light chain amyloidosis.

All randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug were included in the safety analysis set and assessed for adverse events. Patients with ATTR‐CM were randomized in a 2:1:2 ratio to receive tafamidis 80 mg, tafamidis 20 mg, or matching placebo once daily for 30 months. Patients were stratified by TTR genotype (ATTRv and ATTRwt) and NYHA baseline severity classification (NYHA class I and NYHA classes II and III combined).

Upon completion of the 30‐month double‐blind study, patients could enrol in the LTE (NCT02791230), in which patients could be treated with tafamidis for up to an additional 60 months. 15 In the LTE, patients continued to receive the tafamidis dose to which they had been randomized in ATTR‐ACT. Patients who had received placebo in ATTR‐ACT were re‐randomized to receive either 80 or 20 mg tafamidis in the LTE [in a 2:1 ratio; stratified by TTR genotype (ATTRv and ATTRwt)]. In ATTR‐ACT and the LTE, a dose reduction could be requested if patients experienced adverse events that may be associated with poor tolerability. The only actual reduction possible was for patients randomized to 80 mg. As of 20 July 2018, the LTE protocol was amended to transition all patients to tafamidis free acid 61 mg; a new, single capsule formulation bioequivalent to the tafamidis meglumine 80 mg used in ATTR‐ACT 17 (graphical abstract). The transition to tafamidis free acid 61 mg followed the protocol amendment date, not a specified duration of treatment. As such, patients were treated with tafamidis 80 or 20 mg during the LTE for different durations prior to the protocol amendment. The median duration of exposure to tafamidis prior to the transition to tafamidis free acid 61 mg was 39 months in total (in ATTR‐ACT and the LTE).

Both studies were approved by the independent review boards or ethics committee at each participating site, and were conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent.

Efficacy outcomes

The primary analysis in ATTR‐ACT was a hierarchical combination of all‐cause mortality (in which transplantation, either heart or combined heart and liver, or implantation of cardiac mechanical assist device were counted as death) and frequency of CV‐related hospitalizations for pooled tafamidis compared with placebo using the Finkelstein–Schoenfeld method. 14 , 15 , 18 Here, this analysis was conducted separately for each tafamidis dose (80 and 20 mg) compared with placebo. The key secondary endpoints were change from baseline to Month 30 in the distance walked during the 6MWT 19 and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Overall Summary (KCCQ‐OS) score, based on a subset of the 23‐item, patient‐completed KCCQ that assesses HRQoL. 20 Additional secondary analyses included CV‐related mortality and TTR stabilization at Month 1. Exploratory endpoints included change from baseline to Month 30 in NT‐proBNP and troponin I concentrations, and TTR stabilization and TTR concentration throughout the study. The TTR stabilization assay was performed using plasma samples (LabCorp, Los Angeles, CA, USA). 10 , 11 , 12

All‐cause mortality with tafamidis 80 mg compared with 20 mg was assessed over a longer duration of treatment by combining data from ATTR‐ACT (median follow‐up 30 months) with the LTE (median follow‐up 51 months). In addition to ATTR‐ACT data alone, analyses were conducted for ATTR‐ACT combined with LTE patients, which included the additional exposure to tafamidis free acid 61 mg after patients transitioned to the new 61 mg formulation (as of 1 August 2019). Patients continued to be compared based on their initial dose randomization (tafamidis 80 vs. 20 mg).

Statistical analyses

Unless stated otherwise, all analyses were carried out on the modified intent‐to‐treat population of the randomized controlled study, which included all randomized patients with at least one post‐baseline efficacy evaluation and who received at least one dose of study drug.

Details on the statistical analyses have previously been published. 14 , 15 Here, the two doses of tafamidis were compared with placebo using the Finkelstein–Schoenfeld method, 18 as applied in the primary analysis. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyse all‐cause mortality. Poisson regression analysis was used to analyse frequency of CV‐related hospitalization. Secondary and exploratory endpoints (NT‐proBNP and troponin I) were evaluated at each time point post‐baseline using a mixed model repeated measures ANCOVA (MMRM) with an unstructured covariance matrix (or as appropriate), centre, and patients within centre as random effects. The fixed effects were treatment, visit, TTR genotype (ATTRv vs. ATTRwt), and visit by treatment interaction; and baseline score was used as a covariate. For all MMRM analyses, there was no imputation of missing values. The proportion of patients achieving TTR stabilization at Month 1 was compared using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test.

All‐cause mortality in ATTR‐ACT alone and combined with the LTE was assessed as above, based on the pre‐specified Cox proportional hazards model with treatment, NYHA baseline classification, and genotype in the model, and also separately adjusted for additional covariates by adding age, NT‐proBNP (log transformed), and 6MWT distance as covariates to the pre‐specified model (both individually and all three combined). Time of initiation of tafamidis was used as time zero in all survival analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics and transthyretin stabilization in ATTR‐ACT

Of the 548 patients screened for ATTR‐ACT, 441 were randomized to receive tafamidis 80 or 20 mg or placebo (176, 88, and 177, respectively), and 113, 60, and 85 patients, respectively, completed the study. Survival status was collected for all 441 patients at Month 30. Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in online supplementary Table S1 .

Transthyretin stabilization at Month 1 was achieved in a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with tafamidis 80 and 20 mg [144/164 (87.8%) and 67/81 (82.7%) patients, respectively] than with placebo [6/170 (3.5%) patients, P < 0.0001 for both]. Treatment with tafamidis 80 mg also resulted in a greater degree of TTR tetramer stabilization than 20 mg (online supplementary Figure S1 A). Over the 30 months of the study, patients treated with tafamidis 80 mg had higher mean TTR concentrations than those treated with 20 mg or placebo, with tafamidis 20 mg also higher than placebo (online supplementary Figure S1 B).

Efficacy in ATTR‐ACT

In ATTR‐ACT, both tafamidis 80 and 20 mg significantly reduced all‐cause mortality and CV‐related hospitalizations compared with placebo (P = 0.0030 and P = 0.0048, respectively) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Primary analysis with the Finkelstein–Schoenfeld method, all‐cause mortality and frequency of cardiovascular‐related hospitalizations

| Tafamidis 80 mg (n = 176) | Tafamidis 20 mg (n = 88) | Placebo (n = 177) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis | |||

| P‐value from F‐S method | 0.0030 | 0.0048 | |

| Patients a alive, n (%) | 122 (69.3) | 64 (72.7) | 101 (57.1) |

| Average CV‐related hospitalizations during 30 months (PPPY) among those alive at Month 30 | 0.339 | 0.218 | 0.455 |

| All‐cause mortality, n (%) | 54 (30.7) | 24 (27.3) | 76 (42.9) |

| Deaths | 46 (26.1) | 23 (26.1) | 72 (40.7) |

| Heart transplants | 6 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.3) |

| Implantation of a CMAD | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Patients with CV‐related hospitalizations, n (%) | 96 (54.5) | 42 (47.7) | 107 (60.5) |

| Frequency of CV‐related hospitalizations per year | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.70 |

| Tafamidis vs. placebo treatment difference, RRR (95% CI) | 0.70 (0.57–0.85) | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) | – |

| P‐value | 0.0005 | 0.0017 | – |

| CV‐related events, n (%) | 45 (25.6) | 19 (21.6) | 63 (35.6) |

| CV‐related deaths | 37 (21.0) | 18 (20.5) | 59 (33.3) |

| Heart transplants | 6 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.3) |

| Implantation of a CMAD | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Tafamidis vs. placebo treatment difference, HR (95% CI) | 0.69 (0.47–1.01) | 0.68 (0.40–1.14) | – |

| P‐value | 0.0579 | 0.1421 | – |

CI, confidence interval; CMAD, cardiac mechanical assist device; CV, cardiovascular; F‐S, Finkelstein‐Schoenfeld; HR, hazard ratio; PPPY, per patient per year; RRR, relative risk ratio.

Patients who discontinued due to heart or combined heart and liver transplantation, or due to implantation of a CMAD, were counted as death for this analysis.

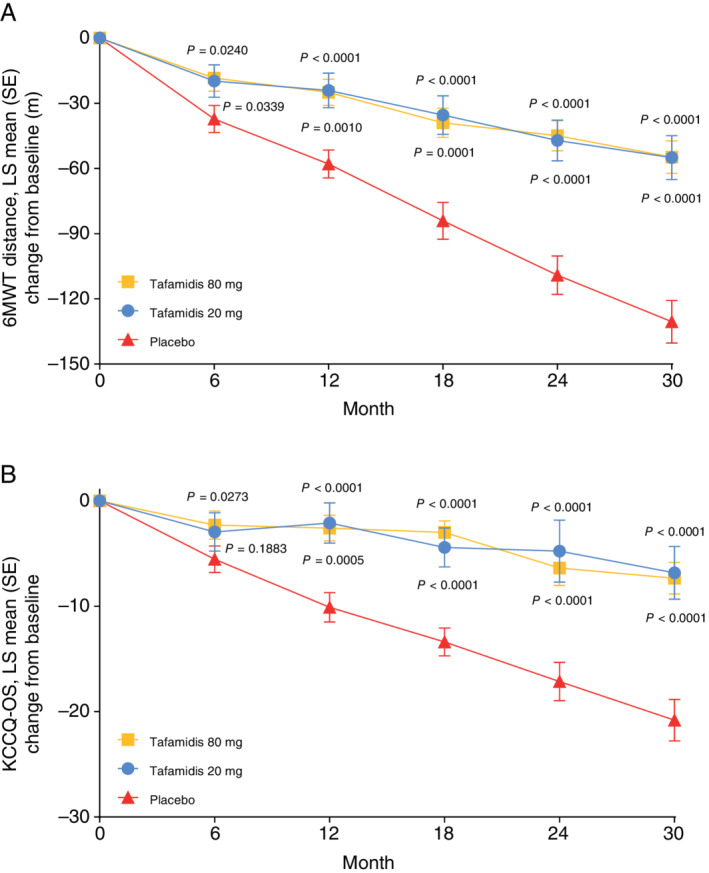

Tafamidis 80 and 20 mg also both significantly reduced the decline in the 6MWT distance at Month 30 compared with placebo [least squares (LS) mean (standard error, SE) metres, 75.77 (10.08) and 75.57 (13.71), respectively; P < 0.0001 for both], with the effect being observed from Month 6 (Figure 1A ).

Figure 1.

Change from baseline with tafamidis 80 mg, tafamidis 20 mg, and placebo in (A) 6‐min walk test (6MWT) distance and (B) Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary (KCCQ‐OS) in ATTR‐ACT. P‐values are for the treatment difference vs. placebo for tafamidis 80 mg (shown above the curve) and tafamidis 20 mg (shown below the curve). LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

Similarly, the change from baseline to Month 30 in KCCQ‐OS score showed a reduction in decline in patients treated with both tafamidis 80 and 20 mg compared with placebo [LS mean (SE), 13.48 (2.20) and 13.99 (2.96), respectively, P < 0.0001 for both] (Figure 1B ). The effect was observed from Month 6 with tafamidis 80 mg and from Month 12 with 20 mg (Figure 1B ).

Treatment with tafamidis 80 mg significantly reduced all‐cause mortality vs. placebo [Cox proportional hazards model (95% confidence interval, CI): 0.690 (0.487–0.979), P = 0.0378]. There was a trend towards improvement with tafamidis 20 mg vs. placebo [Cox proportional hazards model (95% CI): 0.715 (0.450–1.137), P = 0.1564].

The frequency of CV‐related hospitalizations was significantly lower with both tafamidis 80 and 20 mg compared with placebo (Table 1 ). There was a trend towards reduced CV‐related mortality with both doses of tafamidis compared with placebo [Cox proportional hazards model (95% CI): 0.690 (0.470–1.012), P = 0.0579 for tafamidis 80 mg; and 0.678 (0.404–1.139), P = 0.1421 for 20 mg].

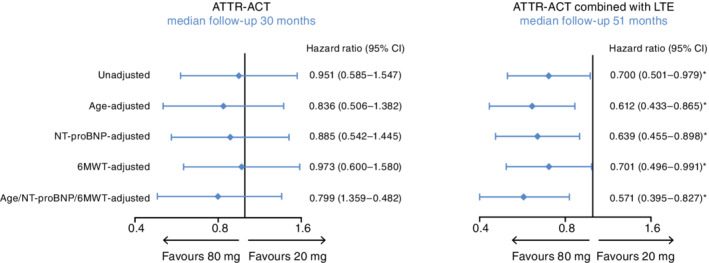

Mortality in ATTR‐ACT and combined with the long‐term extension study

Patients treated with tafamidis 80 mg in ATTR‐ACT were significantly older than those treated with 20 mg (median 76.0 vs. 73.5 years; P = 0.0405) and tended to have more severe disease as assessed by NYHA classification, NT‐proBNP, and 6MWT distance (online supplementary Table S1 ). In ATTR‐ACT there was a trend towards a greater survival benefit with tafamidis 80 mg compared with 20 mg, which was more pronounced (but not significant) with adjustment by covariates (Figure 2 ). In the broader cohort of ATTR‐ACT combined with the LTE (including placebo‐treated patients in ATTR‐ACT randomized to tafamidis), the differences in disease severity between the tafamidis 80 and 20 mg groups appeared to be less pronounced (online supplementary Table S2 ). With the longer exposure of patients in ATTR‐ACT combined with the LTE (median follow‐up 51 months), there was a significant survival benefit with tafamidis 80 vs. 20 mg, with a 30% relative reduction in the risk of death (P = 0.0374). The survival benefit with tafamidis 80 mg compared with 20 mg was also significant (P < 0.05) with all covariate adjustments: 39% reduction in risk of death with age adjustment; 36% with NT‐proBNP adjustment; 30% with 6MWT distance adjustment; and 43% with adjustment by all covariates combined (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of covariate‐adjusted all‐cause mortality in ATTR‐ACT and ATTR‐ACT combined with the long‐term extension study (LTE). Hazard ratios are for: patients in ATTR‐ACT (30 months follow‐up), tafamidis 80 mg (n = 176) compared with 20 mg (n = 88); patients in ATTR‐ACT combined with the LTE and treatment with tafamidis free acid 61 mg (51 months follow‐up), tafamidis 80 mg/tafamidis free acid 61 mg (n = 230) compared with tafamidis 20 mg/tafamidis free acid 61 mg (n = 116). The unadjusted row was based on the prespecified Cox proportional hazards model with treatment, New York Heart Association baseline classification, and genotype in the model. The single covariate‐adjusted rows were generated by adding age, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) (log transformed), and 6‐min walk test (6MWT) distance separately as covariates to the pre‐specified model. The all‐covariate‐adjusted row was generated by adding all covariates to the pre‐specified model. Patients who discontinued due to heart or combined heart and liver transplantation, or due to implantation of a cardiac mechanical assist device, were counted as death for these analyses. *P‐values for ATTR‐ACT combined with the LTE (51 months of follow‐up) were: unadjusted, P = 0.0374; age‐adjusted, P = 0.0054; NT‐proBNP‐adjusted, P = 0.0099; 6MWT‐adjusted, P = 0.0444; age/NT‐proBNP/6MWT‐adjusted, P = 0.0030. CI, confidence interval.

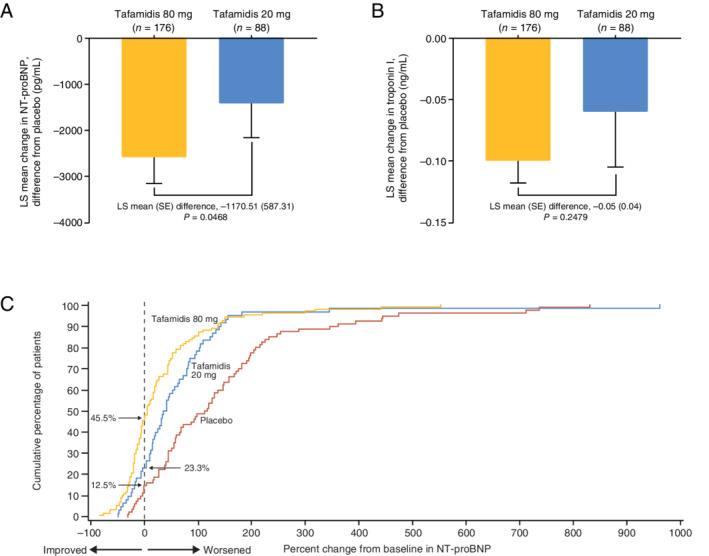

Cardiac biomarkers in ATTR‐ACT

The LS mean (SE) change from baseline to Month 30 in NT‐proBNP concentration for pooled tafamidis (80 and 20 mg doses together) compared with placebo was −2180.54 (583.22) (P = 0.0002). The increase in LS mean (SE) levels of NT‐proBNP from baseline to Month 30 (online supplementary Table S3 ) was significantly reduced with tafamidis 80 mg compared with placebo [−2587.54 (570.25), P < 0.0001], while there was a trend towards a reduction with tafamidis 20 mg compared with placebo [−1417.02 (743.38), P = 0.0571]. Notably, while the increase in NT‐proBNP at Month 30 was lower with each dose of tafamidis separately compared with placebo, the increase with tafamidis 80 mg was also significantly lower than with 20 mg [−1170.51 (587.31), P = 0.0468] (Figure 3A ).

Figure 3.

Least squares (LS) mean (standard error, SE) change in (A) N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) and (B) troponin I from baseline to Month 30 in ATTR‐ACT. The differences from placebo at Month 30 in NT‐proBNP and troponin I were significant for tafamidis 80 mg but not tafamidis 20 mg. (C) Cumulative distribution of percent change from baseline in NT‐proBNP at Month 30 with tafamidis 80 mg, tafamidis 20 mg, and placebo in ATTR‐ACT.

The LS mean (SE) change from baseline to Month 30 in troponin I concentration for pooled tafamidis (80 and 20 mg doses together) compared with placebo was −0.09 (0.023) (P = 0.0002). Similarly to NT‐proBNP, the increase in troponin I at Month 30 was lower with each dose of tafamidis separately compared with placebo [significantly for tafamidis 80 mg: −0.10 (0.018), P < 0.0001; but not 20 mg: −0.06 (0.045), P = 0.2246], with a lower (but not significant) increase in troponin I with tafamidis 80 mg compared with 20 mg [−0.05 (0.042), P = 0.2479] (Figure 3B ).

In a cumulative distribution of the percent change from baseline in NT‐proBNP concentration at Month 30, tafamidis 80 and 20 mg both showed a consistent separation relative to placebo at a range of thresholds for percent change from baseline (Figure 3C ). There was also a consistent separation with tafamidis 80 mg relative to 20 mg.

Safety and tolerability in ATTR‐ACT

Both doses of tafamidis were generally well tolerated and had a safety profile comparable to placebo (online supplementary Table S4 ). The proportion of patients who experienced treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was similar across all three groups, with the majority of TEAEs being mild or moderate in severity. Dose reductions were infrequent, with two patients in the tafamidis 80 mg group and four in the placebo group requesting a dose reduction. Treatment‐related TEAEs were reported by 79 (44.9%), 34 (38.6%), and 90 (50.8%) patients in the tafamidis 80 mg, 20 mg, and placebo groups, respectively, with diarrhoea being the most common treatment‐related TEAE with tafamidis 80 mg [14 (8.0%) patients], compared with two (2.3%) patients with 20 mg and 18 (10.2%) patients with placebo. In the tafamidis 20 mg group, urinary tract infection was the most common treatment‐related TEAE [5 (5.7%) patients] compared with four (2.3%) patients with 80 mg and eight (4.5%) patients with placebo.

A greater proportion of deaths was observed with placebo [49 (27.8%), 23 (26.1%), and 72 (40.7%) patients for tafamidis 80 mg, 20 mg, and placebo, respectively]; the majority of all deaths were considered to be a result of the disease [28 (57.1%), 17 (73.9%), and 49 (68.1%) for tafamidis 80 mg, 20 mg, and placebo, respectively] and none were considered related to treatment with tafamidis.

Safety and tolerability in ATTR‐ACT combined with the long‐term extension study

Safety in the LTE (up to an additional 12 months of treatment with tafamidis, median follow‐up of 36 months across both studies) combined with ATTR‐ACT was similar to the 30‐month ATTR‐ACT alone; safety was comparable for both tafamidis 80 and 20 mg after a prolonged treatment period. In the combined analysis, there were 227 and 115 patients evaluable for TEAEs with tafamidis 80 and 20 mg, respectively. The incidence of serious TEAEs was comparable between tafamidis 80 and 20 mg (69.6% and 72.2%, respectively), as was the incidence of severe TEAEs (53.3% and 53.0%, respectively), and the proportion of patients who discontinued treatment (17.6% and 20.0%, respectively). There were no patients who reduced their dose due to TEAEs.

Discussion

In ATTR‐ACT, tafamidis was shown to be an effective treatment for ATTR‐CM. Due to the limited number of patients who have been diagnosed with this disease, ATTR‐ACT was not designed to assess the relative efficacy of each tafamidis dose. Further analysis of the data from ATTR‐ACT, together with interim data from its LTE, provides guidance on the optimal dose of tafamidis in patients with ATTR‐CM. In this analysis, tafamidis was generally safe and well tolerated, with a similar safety profile for the two doses of tafamidis after 30 months of treatment and an extended period of treatment, with a median of 36 months. Overall, there were fewer dose reduction requests with tafamidis 80 mg than with placebo.

In ATTR‐ACT, both doses of tafamidis (80 and 20 mg) effectively reduced all‐cause mortality and the frequency of CV‐related hospitalizations in patients with ATTR‐CM. The decline in functional capacity and HRQoL was significantly reduced with both doses of tafamidis compared with placebo. While the reduction in the decline in HRQoL compared with placebo was significant and first observed at Month 6 with tafamidis 80 mg and from Month 12 with 20 mg, the efficacy of each dose of tafamidis was comparable. Overall, in ATTR‐ACT mortality and CV‐related hospitalizations were comparable between the tafamidis doses.

In order to definitively assess the relative efficacy of each dose, combining data from ATTR‐ACT with the LTE provides the opportunity for further comparison. With the longer duration of treatment, and the addition of patients previously treated with placebo, a significant reduction in risk of death with tafamidis 80 mg compared with 20 mg was demonstrated (median follow‐up 51 months). There was a significant difference between the doses, with a 30% relative reduction in the risk of death with 80 mg compared with 20 mg (P = 0.0374). These data were further supported by analyses that accounted for the baseline imbalance in age and disease severity between the doses. As age is a prognostic factor for survival, adjustment by age was included in the post‐hoc analysis. Given that the life expectancy of a 76‐year‐old male in the United States is notably lower than that of a 73‐year‐old male (assuming an exponential distribution and with the life expectancy of 10.58 years for a 76‐year‐old and 12.43 years for a 73‐year‐old male 21 ), there is a 17.5% higher risk of death in the 76‐year‐old male. Similarly, NT‐proBNP and 6MWT distance are prognostic factors for survival in patients with ATTR‐CM or HF. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Adjustment by these three covariates (age, NT‐proBNP, and 6MWT) also resulted in a significant difference between the doses.

Dose‐dependent stabilization of TTR with tafamidis has previously been described in patients with ATTR‐PN and in patients with ATTR‐CM, including patients with ATTRwt and patients with a number of different TTR mutations. 10 , 11 , 12 TTR stabilization was maintained over the duration of those studies (up to 12 months). 12 In ATTR‐ACT, it was anticipated that the 80 mg dose of tafamidis may result in a greater degree of TTR stabilization. 15 , 26 While both doses stabilized TTR in a significant proportion of patients, only tafamidis 80 mg (and not 20 mg) approached the plateau considered the target for stabilization (online supplementary Figure S1 A). There was also a higher mean TTR concentration with tafamidis 80 mg, compared with 20 mg, suggesting that more TTR was conserved in its tetramer structure and less dissociated TTR was consumed in the amyloidogenic cascade.

Cardiac biomarkers such as NT‐proBNP and troponin have previously been used alongside other biomarkers to assess disease progression in patients with ATTR‐CM. 12 , 23 , 24 , 27 Higher baseline levels of NT‐proBNP (>3000 pg/mL) and reduced eGFR (<45 mL/min) were significantly associated with increased mortality in patients with ATTR‐CM. 24 Higher baseline NT‐proBNP and troponin T levels were also significantly associated with increased mortality in patients with ATTRwt. 23 In ATTR‐ACT, there was a significant reduction in the increase in NT‐proBNP and troponin I over time with tafamidis 80 mg compared with placebo, and the reduction in the increase in NT‐proBNP with tafamidis 80 mg was significantly greater than that with 20 mg. Furthermore, the percentage of patients with stable or reduced NT‐proBNP levels at Month 30 was higher with tafamidis 80 mg than 20 mg. NT‐proBNP was reduced in almost half (45.5%) of tafamidis 80 mg patients [compared with one‐quarter (23.3%) with 20 mg].

Limitations

As not all secondary and exploratory outcome measures were collected in the LTE, it was not possible to assess the longer‐term effect of tafamidis treatment on cardiac biomarkers or measures of functional capacity and HRQoL.

Conclusions

Tafamidis, at both 80 and 20 mg, effectively reduced mortality and CV‐related hospitalizations, and the decline in functional capacity and HRQoL in patients with ATTR‐CM. While ATTR‐ACT was not designed to assess the relative efficacy of each tafamidis dose, the lack of dose‐related safety concerns, together with TTR stabilization and NT‐proBNP data, supported the use of tafamidis 80 mg as the preferred dose. This was confirmed by longer‐term (median 51 months) treatment data in which there was a significant, 30% relative reduction in the risk of death with tafamidis 80 mg compared with 20 mg. Taken together, these data support the use of tafamidis 80 mg (bioequivalent to tafamidis free acid 61 mg) as the optimal dose in patients with ATTR‐CM.

Supporting information

Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteristics in ATTR‐ACT.

Table S2. Demographic and clinical characteristics in ATTR‐ACT combined with LTE.

Table S3. Change in cardiac biomarkers at endpoint in ATTR‐ACT.

Table S4. Treatment‐emergent adverse events (all causalities) in ATTR‐ACT.

Figure S1. (A) TTR tetramer stabilization with tafamidis 80 mg and tafamidis 20 mg in ATTR‐ACT. (B) Mean TTR concentration with tafamidis 80 mg, tafamidis 20 mg, and placebo in ATTR‐ACT. The black line represents the mean percentage TTR stabilization in patients with ATTR‐CM. The orange‐shaded region demonstrates the percentage stabilization expected over the geometric mean steady‐state Cmin to Cmax following daily administration of tafamidis 80 mg. This approaches the plateau considered to be the target for stabilization. The blue‐shaded region demonstrates the tafamidis 20 mg steady‐state exposures and is well below the stabilization plateau. ATTR‐CM, transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; Cmin, minimum plasma concentration; TTR, transthyretin.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and their families, and all study investigators, for their participation in this study. We thank Michelle Casey (Pfizer) for her suggestions and guidance on these analyses and Ben Ebede (Pfizer) for his contribution to the long‐term extension study. Medical writing support was provided by Joshua Fink, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions, and was funded by Pfizer.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer.

Data sharing

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical‐trials/trial‐data‐and‐results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de‐identified participant data from Pfizer‐sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the US and/or EU or (2) in programmes that have been terminated (i.e. development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de‐identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.

Conflict of interest: T.D. has served on a scientific advisory board for Pfizer; received funding from Pfizer for scientific meeting expenses; and his institution has received grant support from Pfizer. P.G.P. has served as a speaker in scientific meetings for Pfizer, Eidos, Akcea, and Alnylam; received funding from Pfizer and Alnylam for scientific meeting expenses; received consultancy fees from Pfizer, Alnylam, Eidos, Akcea, and Neuroimmune; and his institution has received grant/educational support from Pfizer, Eidos, Alnylam, Akcea, and Prothena. M.H. has received honoraria for advisory board participation from Pfizer, Alnylam, Akcea, and Eidos; and served as a speaker for a scientific meeting session funded by Alnylam. D.P.J. has received grants and funding for the trial, for travel expenses, and consultancy fees from Pfizer; received consultancy fees from Alnylam, Blade Therapeutics, and GSK; received clinical trial funding from Array Biopharma and Eidos. G.M. has no conflicts to disclose. B.G., T.A.P., S.R., and M.B.S. are full‐time employees of Pfizer and hold stock and/or stock options. At the time of this analysis J.H.S. was an employee of Pfizer; he holds stock and stock options with Pfizer and is now retired. R.W. has received honoraria for advisory board participation from Pfizer and Alnylam, and funding for clinical trials from Pfizer, Alnylam, and Eidos.

References

- 1. Ruberg FL, Berk JL. Transthyretin (TTR) cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation 2012;126:1286–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rapezzi C, Quarta CC, Riva L, Longhi S, Gallelli I, Lorenzini M, Ciliberti P, Biagini E, Salvi F, Branzi A. Transthyretin‐related amyloidoses and the heart: a clinical overview. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Almeida MR, Hesse A, Steinmetz A, Maisch B, Altland K, Linke RP, Gawinowicz MA, Saraiva MJ. Transthyretin Leu 68 in a form of cardiac amyloidosis. Basic Res Cardiol 1991;86:567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jacobson DR, Pastore RD, Yaghoubian R, Kane I, Gallo G, Buck FS, Buxbaum JN. Variant‐sequence transthyretin (isoleucine 122) in late‐onset cardiac amyloidosis in black Americans. N Engl J Med 1997;336:466–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ranløv I, Alves IL, Ranløv PJ, Husby G, Costa PP, Saraiva MJ. A Danish kindred with familial amyloid cardiomyopathy revisited: identification of a mutant transthyretin‐methionine111 variant in serum from patients and carriers. Am J Med 1992;93:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sattianayagam PT, Hahn AF, Whelan CJ, Gibbs SD, Pinney JH, Stangou AJ, Rowczenio D, Pflugfelder PW, Fox Z, Lachmann HJ, Wechalekar AD, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD. Cardiac phenotype and clinical outcome of familial amyloid polyneuropathy associated with transthyretin alanine 60 variant. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1120–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Damy T, Judge DP, Kristen AV, Berthet K, Li H, Aarts J. Cardiac findings and events observed in an open‐label clinical trial of tafamidis in patients with non‐Val30Met and non‐Val122Ile hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2015;8:117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Damy T, Maurer MS, Rapezzi C, Plante‐Bordeneuve V, Karayal ON, Mundayat R, Suhr OB, Kristen AV. Clinical, ECG and echocardiographic clues to the diagnosis of TTR‐related cardiomyopathy. Open Heart 2016;3:e000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rapezzi C, Quarta CC, Obici L, Perfetto F, Longhi S, Salvi F, Biagini E, Lorenzini M, Grigioni F, Leone O, Cappelli F, Palladini G, Rimessi P, Ferlini A, Arpesella G, Pinna AD, Merlini G, Perlini S. Disease profile and differential diagnosis of hereditary transthyretin‐related amyloidosis with exclusively cardiac phenotype: an Italian perspective. Eur Heart J 2013;34:520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coelho T, Merlini G, Bulawa CE, Fleming JA, Judge DP, Kelly JW, Maurer MS, Plante‐Bordeneuve V, Labaudiniere R, Mundayat R, Riley S, Lombardo I, Huertas P. Mechanism of action and clinical application of tafamidis in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Neurol Ther 2016;5:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bulawa CE, Connelly S, Devit M, Wang L, Weigel C, Fleming JA, Packman J, Powers ET, Wiseman RL, Foss TR, Wilson IA, Kelly JW, Labaudiniere R. Tafamidis, a potent and selective transthyretin kinetic stabilizer that inhibits the amyloid cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:9629–9634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maurer MS, Grogan DR, Judge DP, Mundayat R, Packman J, Lombardo I, Quyyumi AA, Aarts J, Falk RH. Tafamidis in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: effects on transthyretin stabilization and clinical outcomes. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saelices L, Johnson LM, Liang WY, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Ruchala P, Whitelegge J, Jiang L, Riek R, Eisenberg DS. Uncovering the mechanism of aggregation of human transthyretin. J Biol Chem 2015;290:28932–28943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington‐Cruz M, Kristen AV, Grogan M, Witteles R, Damy T, Drachman BM, Shah SJ, Hanna M, Judge DP, Barsdorf AI, Huber P, Patterson TA, Riley S, Schumacher J, Stewart M, Sultan MB, Rapezzi C; ATTR‐ACT Study Investigators. Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maurer MS, Elliott P, Merlini G, Shah SJ, Waddington‐Cruz M, Flynn A, Gundapaneni B, Hahn C, Riley S, Schwartz J, Sultan MB, Rapezzi C. Design and rationale of the phase 3 ATTR‐ACT clinical trial (Tafamidis in Transthyretin Cardiomyopathy Clinical Trial). Circ Heart Fail 2017;10:e003815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klamerus KJ, Watsky E, Moller R, Wang R, Riley S. The effect of tafamidis on the QTc interval in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;79:918–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lockwood PA, Le VH, O'Gorman MT, Patterson TA, Sultan MB, Tankisheva E, Wang Q, Riley S. The bioequivalence of tafamidis 61‐mg free acid capsules and tafamidis meglumine 4 × 20‐mg capsules in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2020;9:849–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Finkelstein DM, Schoenfeld DA. Combining mortality and longitudinal measures in clinical trials. Stat Med 1999;18:1341–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories . ATS statement: guidelines for the six‐minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Social Security Administration . Actuarial Life Table 2016. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html (20 October 2020).

- 22. Witteles RM, Bokhari S, Damy T, Elliott PM, Falk RH, Fine NM, Gospodinova M, Obici L, Rapezzi C, Garcia‐Pavia P. Screening for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in everyday practice. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grogan M, Scott CG, Kyle RA, Zeldenrust SR, Gertz MA, Lin G, Klarich KW, Miller WL, Maleszewski JJ, Dispenzieri A. Natural history of wild‐type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and risk stratification using a novel staging system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1014–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gillmore JD, Damy T, Fontana M, Hutchinson M, Lachmann HJ, Martinez‐Naharro A, Quarta CC, Rezk T, Whelan CJ, Gonzalez‐Lopez E, Lane T, Gilbertson JA, Rowczenio D, Petrie A, Hawkins PN. A new staging system for cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2799–2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ingle L, Rigby AS, Carroll S, Butterly R, King RF, Cooke CB, Cleland JG, Clark AL. Prognostic value of the 6 min walk test and self‐perceived symptom severity in older patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2007;28:560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cho Y, Baranczak A, Helmke S, Teruya S, Horn EM, Maurer MS, Kelly JW. Personalized medicine approach for optimizing the dose of tafamidis to potentially ameliorate wild‐type transthyretin amyloidosis (cardiomyopathy). Amyloid 2015;22:175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kristen AV, Maurer MS, Rapezzi C, Mundayat R, Suhr OB, Damy T. Impact of genotype and phenotype on cardiac biomarkers in patients with transthyretin amyloidosis – report from the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcome Survey (THAOS). PLoS One 2017;12:e0173086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteristics in ATTR‐ACT.

Table S2. Demographic and clinical characteristics in ATTR‐ACT combined with LTE.

Table S3. Change in cardiac biomarkers at endpoint in ATTR‐ACT.

Table S4. Treatment‐emergent adverse events (all causalities) in ATTR‐ACT.

Figure S1. (A) TTR tetramer stabilization with tafamidis 80 mg and tafamidis 20 mg in ATTR‐ACT. (B) Mean TTR concentration with tafamidis 80 mg, tafamidis 20 mg, and placebo in ATTR‐ACT. The black line represents the mean percentage TTR stabilization in patients with ATTR‐CM. The orange‐shaded region demonstrates the percentage stabilization expected over the geometric mean steady‐state Cmin to Cmax following daily administration of tafamidis 80 mg. This approaches the plateau considered to be the target for stabilization. The blue‐shaded region demonstrates the tafamidis 20 mg steady‐state exposures and is well below the stabilization plateau. ATTR‐CM, transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; Cmin, minimum plasma concentration; TTR, transthyretin.