Abstract

Most corn (Zea mays) seeds planted in the United States in recent years are coated with a seed treatment containing neonicotinoid insecticides. Abrasion of the seed coating generates insecticide‐laden planter dust that disperses through the landscape during corn planting and has resulted in many “bee‐kill” incidents in North America and Europe. We investigated the linkage between corn planting and honey bee colony success in a region dominated by corn agriculture. Over 3 yr we consistently observed an increased presence of corn seed treatment insecticides in bee‐collected pollen and elevated worker bee mortality during corn planting. Residues of seed treatment neonicotinoids, clothianidin and thiamethoxam, detected in pollen positively correlated with cornfield area surrounding the apiaries. Elevated worker mortality was also observed in experimental colonies fed field‐collected pollen containing known concentrations of corn seed treatment insecticides. We monitored colony growth throughout the subsequent year in 2015 and found that colonies exposed to higher insecticide concentrations exhibited slower population growth during the month of corn planting but demonstrated more rapid growth in the month following, though this difference may be related to forage availability. Exposure to seed treatment neonicotinoids during corn planting has clear short‐term detrimental effects on honey bee colonies and may affect the viability of beekeeping operations that are dependent on maximizing colony size in the springtime. Environ Toxicol Chem 2021;40:1212–1221. © 2020 The Authors. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of SETAC.

Keywords: Apis mellifera, Clothianidin, Glycine max, Pollinators, Seed treatment, Fugitive dust, Thiamethoxam

INTRODUCTION

Based on the most recent estimate, 79 to 100% of corn (Zea mays) in the United States is grown from seed treated with neonicotinoid insecticides (Douglas and Tooker 2015). The predominant neonicotinoids used in corn seed treatments are clothianidin (Poncho®, US Environmental Protection Agency [USEPA] registration no. 264‐789) and thiamethoxam (Cruiser®, USEPA registration no. 100‐1208) at rates between 0.125 and 1.25 mg active ingredient per seed, depending on the corn insect pest of concern (Douglas and Tooker 2015). Assuming a seeding rate of 54 000 to 82 000 seeds per hectare (Thomison 2015), up to 100 g/hectare of insecticide active ingredients are applied to sown fields each year. In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, nearly 1.6 million kg of clothianidin and 0.4 million kg of thiamethoxam were applied in the form of corn seed treatment in the United States (US Geological Survey 2017; Hitaj et al. 2020). These broad‐spectrum insecticides are highly toxic to many insects, including honey bees (Apis mellifera L.), to which they are lethal in nanogram quantities—as low as 0.003 μg/bee for oral median lethal dose (LD50) and 0.02 μg/bee for contact LD50 over 48 h (Decourtye and Devillers 2010; Laurino et al. 2013).

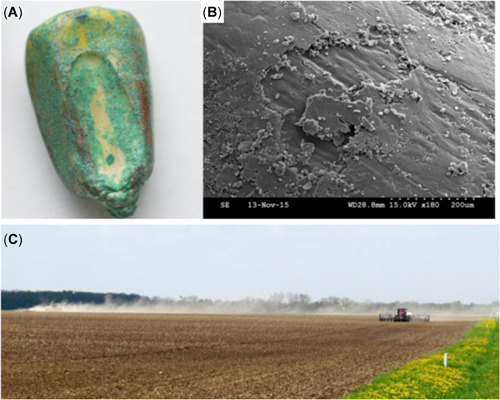

During the planting process, seed treatment material sloughs off the seed surface in small particles that are available to disperse in the environment (Figure 1). Bees may encounter these particles as dust deposited on flowers (Krupke et al. 2012) or as aerial dust during flight (Girolami et al. 2013). Particles may also contaminate surface water consumed by bees (Samson‐Robert et al. 2014; Schaafsma et al. 2015). Insecticide residues present in soil from seed treatments used in previous years may become airborne during planting and contribute to bee exposure during this period (Forero et al. 2017). Pollen and airborne particles adhered to the hair of a foraging bee are incorporated into the pollen baskets during grooming and enter the colony as the bee deposits its pollen load as “bee bread” in storage cells. The bee bread is then consumed by young worker bees nursing honey bee larvae, and subsequently the insecticidal contaminants are circulated within the colony.

Figure 1.

Seed treatments are applied to seeds as flowable solids that dry to form a coating. In corn, this coating results in visibly patchy coverage of the seed (A). The seed treatment forms particles of varying size on the surface of the seed as captured using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), (B). The striated surface visible in the center of the micrograph is the seed surface. Particles of the seed treatment coating are then emitted as planter dust during the sowing process (C). Macrophotography was performed by M. Spring and SEM preparation by K. Kaszas.

A link between observations of honey bee mortality and the planting of neonicotinoid‐treated corn seeds was suspected as early as the late 1990s, when researchers in Italy noted a rise in colony damage reports coinciding with spring corn planting (Bortolotti et al. 2009). In subsequent years, similar patterns of honey bee mortality were observed in Italy (Schnier et al. 2003; Greatti et al. 2006; Mutinelli et al. 2010), France (Giffard and Dupont 2009), and Slovenia (Alix et al. 2009; Žabar et al. 2012). In 2008, a large‐scale bee kill in Germany and neighboring parts of France was attributed to the planting of neonicotinoid‐treated corn seed after an extensive investigation found neonicotinoid residues in dead bees, bee bread, and plant samples collected from the affected area (Forster 2009; Nikolakis et al. 2009; Pistorius et al. 2009; Chauzat et al. 2010). Since then, additional incidents of honey bee mortality during corn planting have been reported in Slovenia (van der Geest 2012), the United States (Krupke et al. 2012; L. Keller, personal communication, 2016), and Canada (Health Canada 2013; Samson‐Robert et al. 2017).

In the present study, we investigated the link between honey bee mortality and insecticide exposure during corn planting and evaluated colony health in the months following the exposure. To better understand the association between corn planting, neonicotinoid residues in honey bee–collected pollen, and honey bee mortality, we conducted a 3‐yr field study (2013–2015) in Ohio, one of the largest corn‐growing states in the United States (US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service 2019). Each year, we measured worker bee mortality and neonicotinoid residues in bee‐collected pollen prior to, during, and after corn planting. In 2015, we expanded the investigation to examine pollen contamination and bee mortality in apiaries located in landscapes with varying areas of cornfields within foraging range. We also analyzed neonicotinoid residues in stored pollen to evaluate the persistence of corn seed treatment insecticides in honey bee colonies and monitored colony growth and overwinter survival in the year following exposure.

Pesticide exposure and mortality of free‐flying bees are influenced by complex factors that are difficult to measure in the field. The level of exposure depends on the spatial and temporal intersection of foraging bees and active corn planting, both of which are influenced by weather and can be highly variable across sites. Dead bees collected at the colony do not account for intoxicated foragers that fail to return to the colony; therefore, our field study may underestimate worker bee mortality. To experimentally verify the link between contamination of pollen and worker bee mortality, a semifield experiment was conducted in which colonies in a controlled environment were provisioned with pollen collected during corn planting containing a range of concentrations of neonicotinoid insecticides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites

A total of 13 apiary sites located throughout the corn‐growing region of central Ohio were monitored prior to, during, and after corn‐sowing from late April until the end of May in 2013 (3 sites), 2014 (6 sites), and 2015 (10 sites). Four sites (CH, MB, FSR, WB) were studied in multiple years (Supplemental Data, S1). The sites were located at least 4 km from each other and were selected to represent a wide range of cropland area within a 2‐km radius centering on the apiary, including one suburban site in 2015 with minimal corn agriculture within the foraging range of honey bees. Each apiary consisted of 4 to 20 colonies. Two to 4 healthy, actively foraging colonies, varying in sizes and queen ages, were monitored for worker mortality (Supplemental Data, S1). All colonies were housed in 8‐ or 10‐framed Langstroth hives.

The timing of corn planting was identified through direct observation of planter activity near the sites and communication with farmers in this region. The bulk of corn planting activity in the study area occurred between 5 and 16 May in 2013, 5 and 10 May in 2014, and 2 and 8 May in 2015. These dates were in concordance with weekly statewide agricultural statistics on planting progress (US Department of Agriculture 2017). Sporadic corn planting activities continued beyond this period in all years but were particularly drawn out in 2014 when high rainfall resulted in planting and replanting activity through the end of May.

Landscape characterization

Landscape composition at each site was characterized within a 2‐km radius foraging range centered on the apiary. Visual ground‐truthing supplemented by satellite imagery (Google OpenLayers) was used to classify landscapes into crop field, forest, tree lines, and herbaceous strips in field margins, roadsides, and residential lots. Crop type was determined by a second visual inspection in early summer and verified with the CropScape—Cropland Data Layer (US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service 2018). All landscape data were analyzed and visualized using QGIS 2.1 software (QGIS Development Team 2016). Apiaries in the first 2 yr were located in areas with high percentages of corn agriculture within the foraging range (31–45% in 2013 and 21–51% in 2014). In 2015 the gradient of corn agriculture area around sites ranged from 1 to 49%.

Sampling and pesticide screening

Pollen pellets carried on the pollen baskets of foraging bees returning to the colonies were collected using bottom‐mounted pollen traps (Sundance I; Ross Rounds) installed on 2 strong hives at each site. Trapped pollen was collected every 2 to 4 d from late April to the end of May each year (2013–2015) and pooled by sites and sampling dates. In 2015, pollen and honey stored within the colony were also analyzed to evaluate the persistence of corn seed treatment insecticides. Honey and bee bread (compacted pollen in comb cells) were sampled from cells peripheral to the brood area where bees were actively depositing food. In‐hive samples were collected from 2 queenright colonies at 7 sites (DS, SC, IB, BR, HR, TV, MO) during 4 sampling periods in 2015: before planting (27–30 April), during planting (5–7 May), immediately after planting (12–13 May), and 2 wk after planting (20–22 May). All samples were stored in darkness at –20 °C until further analysis.

Five grams of pollen from each site and sampling date were extracted using a modified quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe protocol for the 2013 and 2014 samples (Camino‐Sánchez et al. 2010). Pollen, honey, and bee bread from 2015 were extracted from 1 to 5 g of sample following a method by Yáñez et al. (2014), except that ethyl acetate was used instead of dichloromethane (Supplemental Data, S2). In all years, extracts were analyzed for neonicotinoid insecticides (clothianidin, thiamethoxam, and imidacloprid) using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometric methods. Analysis was performed by the US Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Marketing Service lab in Gastonia, North Carolina (2013 and 2014 samples) and the USEPA National Exposure Research Laboratory in Athens, Georgia (2015 samples). All residues were reported as mass‐mass concentration (nanograms per gram).

Dead bee trapping

Underbasket‐style dead bee traps (102 × 51 × 15 cm; Human et al. 2013) were placed in front of 2 to 6 monitored colonies each year (2013–2015) from late April until the end of May or early June, 1 to 2 wk after corn planting activities had ceased. Dead bees in traps were emptied and counted every 2 to 4 d during the sampling period.

Statistical analyses: Worker mortality and pollen contaminations

The number of bees counted in dead bee traps on each visit was averaged over the number of days elapsed since the last visit to estimate daily dead bee counts for each colony. Because large colonies eject more dead bees than small colonies, a daily mortality index, denoted by M i, was calculated using the following formula to account for size and behavioral differences among colonies:

| (1) |

In Equation 1, N i is the number of dead bees per day on a given date i and N max is the highest number of dead bees per day of a given colony observed during the entire sampling period.

The standardized mortality M i ranges between 0 and 1 for each colony unless N max = 0. In the unlikely event that no dead bee was observed in the trap, then M i = 0. If nonzero dead bee counts were consistent throughout the sampling period (i.e., N i values did not deviate much from N max), then all M i values would be near 1 regardless of the timing of corn planting.

To compare bee mortality between planting and nonplanting periods, colony‐specific means of M i values for each period were calculated, and means of the same colonies were compared using paired‐sample t tests. A separate analysis was performed for each year.

Time‐series intervention analysis

Because the mortality data represent a time series with a known intervention (i.e., corn planting), the mortality response to insecticide concentrations was also examined using time‐series intervention analysis (Box and Tiao 1975). We use M t to denote the mortality rate at time t and X t to denote the insecticide concentration in pollen at time t for a given site‐year‐colony. The test for a linear association between M t and X t can be parameterized as a time‐series regression model:

| (2) |

The hypothesis H0: β 1 = 0 is equivalent to zero correlation between mortality rate and insecticide concentration. Alternatively, the test for differences in worker bee mortality between the planting and nonplanting periods can be modeled by the following time‐series intervention model:

| (3) |

In Equation 3, I t is equal to 1 if t is in the planting period and 0 otherwise. The model parameter β 2 is the difference in mortality rate between the planting and nonplanting periods and represents a step intervention. We can combine Equations 1 and 2 into a time‐series intervention model:

| (4) |

The time‐series intervention model can be generalized to allow for more general types of interventions (i.e., pulse, step, trend) and multiple predictor variables including lagged values of insecticide concentrations. The time‐series intervention model with a first‐order autoregressive structure is

| (5) |

where the predictor variables are indicator variables or continuous variables, possibly lagged values of one or more insecticide concentrations. We assume that M t is a stationary autoregressive‐moving average time series. The null hypothesis, H0: β i = 0, can therefore be tested using a likelihood‐based test statistic for a time‐series model from the Box‐Jenkins class of autoregressive‐moving average models.

The mortality rate time series for each colony at an apiary site is assumed to be an independent representation of a time series. Thus, the time‐series intervention model in Equation 4 was fit individually for each site studied in 2015. For each model, a combination of pesticide concentration terms (current time point and lagged) and intervention terms was chosen to minimize the Akaike information criterion.

Closed colony experiment

A closed colony experiment was performed in 2015 to evaluate mortality of worker bees fed with contaminated pollen collected from colonies during corn planting. Bee Brief Nuc boxes (NOD Apiary Products) were set up to contain a pollen feeder, 2 frames of drawn wax combs with approximately 100 cm2 of capped brood for stabilizing the colony, a mated queen (3–5 wk postmating), and nurse bees shaken from one brood frame in a healthy donor colony. The equipment was weighed when empty and again after bees were added to measure the net weight of bees per closed colony. The pollen feeder was made of two 96‐well cell culture plates (Biotix; AP‐0350‐9CU) affixed to a plastic foundation. Pollen (200 g) harvested from the study sites during corn planting (2–19 May 2015) was provided. All colonies also had unlimited access to fresh 50% (w/w) sucrose water throughout the experiment. Four trials, each including 4 to 7 closed colonies, were conducted (20 colonies total). Each trial also contained a positive control with pollen spiked with 100 ng g−1 technical clothianidin (99.9% PESTANAL®; Sigma‐Aldrich) and a negative control with pollen collected from a low‐exposure site. Five grams of pollen were collected following the experiment for pesticide analysis. Enclosed colonies were kept in a dark room at 19 °C (nighttime) to 24 °C (daytime) for 96 h. Dead bees in the boxes were then counted, and pollen consumption was determined by weight. Two colonies contained <100 g of bees and were excluded from further analysis.

Pairwise correlations between colony weights, pollen consumed, dead bees, and neonicotinoid concentrations in pollen were performed as exploratory analyses to identify possible associations between the variables. To evaluate the effect of clothianidin and its interactive effects with colony parameters on mortality, a linear mixed‐effects model (JMP®, Ver 13.1; SAS Institute) was constructed with dead bees as the response variable; full‐factorial interactions of clothianidin, colony weight, and pollen consumed as fixed effects; and trials as the random effect. Colony parameters that were not significant predictors were dropped, and the model was refitted.

Postplanting colony growth

To address the question of whether exposure to corn seed treatment insecticides in May is linked to long‐term consequences in colony growth, we tracked the colonies in 2015 through the following winter to March 2016. Four detailed colony inspections were performed using a modified Liebfelder method (Delaplane et al. 2013) on 28 to 30 April (before planting), 20 to 22 May (after planting), 19 to 24 June, and 14 to 19 August. During hive inspections, each frame from the monitored colonies was examined to record the area of coverage with the following components: adult bees, brood (open and capped), pollen, and honey. In addition, the total adult bee population was estimated by looking up and down spaces between frames to estimate “seams” of adult bees. All colonies were managed using standard beekeeping practices. Varroa destructor mites were controlled by applying formic acid (Mite Away Quick Strip; NOD Apiary Products) in June and vaporized oxalic acid in November. Plain baker's fondant (Dawn Food Products) and Dadant AP23 winter patties (Dandant & Sons) were fed to the colonies, as needed, through the winter. The number of surviving colonies was recorded on 24 March 2016.

We examined whether the relative change in each colony variable (adult bees, pollen stores, nectar stores, open brood, and capped brood) through time was associated with neonicotinoid concentrations measured in pollen in May. Relative change for each variable was calculated as

| (6) |

We considered each interval between inspection dates, as well as the interval between the first and last inspections. To determine whether neonicotinoid residues in pollen were significantly associated with colony growth through time, we constructed linear regression models with relative change as the response and summed mean clothianidin and thiamethoxam concentrations in pollen in May as the predictor in R, Ver 3.4.3 (R Development Core Team 2017). We also included the relative change in colony pollen coverage over the same time interval as a covariate, to account for the potential that the negative effects of neonicotinoid exposure could be partially offset by the positive effects of abundant floral resources in agricultural landscapes of this region. If the pollen change covariate was not a significant predictor, we dropped the term and refit the model.

RESULTS

Worker bee mortality

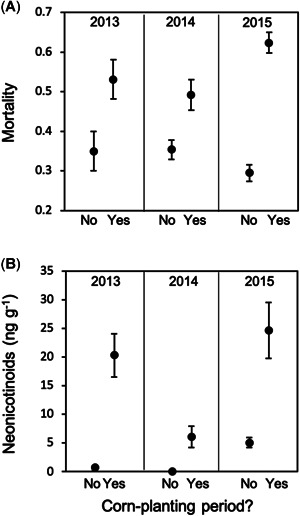

For 3 consecutive yr, increased numbers of dead bees at hive entrances were consistently observed around the time corn was being planted. Worker mortality was significantly and consistently higher during corn planting than the nonplanting periods for the same colonies for all years (paired t test, 2013: t = 2.62, df = 11, p = 0.02; 2014: t = 3.24, df = 23, p = 0.004; 2015: t = 11.82, df = 37, p < 0.0001; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Honey bee worker daily mortality index and neonicotinoid (clothianidin and thiamethoxam) concentrations detected in pollen samples collected during planting and nonplanting periods. Whiskers represent 1 standard error around the means.

Pollen contamination

Analysis of pollen samples collected in pollen traps showed that clothianidin and thiamethoxam, the insecticides present in corn seed treatments, were the most abundant neonicotinoid insecticides detected; and the detection of these compounds occurred more frequently (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.0001) and at higher concentrations (unequal variance t tests, p < 0.0003) during corn planting periods (Figure 2B; Supplemental Data, S3) for all sites. Neonicotinoid insecticides that are not used for corn seed treatments but are applied to other crops in Ohio (imidacloprid, nitenpyram, dinotefuran, acetamiprid, and thiacloprid; Supplemental Data, S4) were detected in some pollen samples, but the timing of detection for other neonicotinoids was not related to corn planting.

The relationship between neonicotinoid residues in pollen and the area of corn grown within the foraging range was evaluated for 10 sites studied in 2015. During corn planting, pollen collected from sites surrounded by more cornfields contained higher concentrations of clothianidin (Pearson's r = 0.65, p = 0.040) and thiamethoxam (r = 0.62, p = 0.056) but not any of the other neonicotinoids (p > 0.15). The total concentration of clothianidin and thiamethoxam together was also significantly correlated with cornfield area (r = 0.68, p = 0.030) during planting. No correlation between cornfield area and clothianidin or thiamethoxam concentrations was detected outside the planting period (p > 0.4).

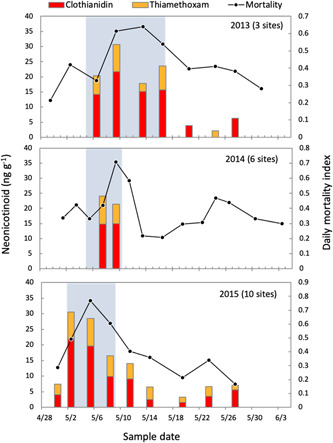

Relating worker mortality to neonicotinoids with time‐series intervention analysis

The onset of corn planting was followed by increased presence of corn seed treatment insecticides in bee‐collected pollen; then, worker bee mortality peaked shortly after (Figure 3). To evaluate the delayed effect of insecticide exposure, temporal variation in worker bee mortality over the sampling period in 2015 was related to neonicotinoid concentrations using a regression‐based time‐series intervention model fit individually by site. The best models, as chosen by the Akaike information criterion, explained 42 to 96% of the variation in mortality, with total concentrations of clothianidin and thiamethoxam being the explanatory pesticide variable at each site (Supplemental Data, S5). Inspection of the residuals and their autocorrelations revealed no model inadequacies. Adding the other pesticides to the analyses did not improve the fit of the time‐series intervention model at any site. Mortality increased linearly with increasing neonicotinoid concentrations at all sites, and there was a lagged mortality response to insecticide exposure at 6 of 10 sites (DS, MB, WB, TV, MO, FSR). Further, the mortality rate peaked during or shortly after the planting period, as indicated by either a positive pulse or a step intervention term in the time‐series model.

Figure 3.

Temporal variation in worker bee mortality and concentrations of clothianidin and thiamethoxam detected in pollen over the sampling periods in 2013 to 2015. The solid lines depict the daily mortality index (ranging 0–1) averaging across sites for each year. Bars depict average neonicotinoid concentrations in pollen sampled on given dates. Gray blocks indicate the corn‐planting periods identified for each year.

Insecticide residues in stored food

Total concentrations of clothianidin and thiamethoxam in stored pollen or bee bread were generally low before planting (<13.5 ng g−1, mean 4.0 ng g−1). The levels increased in samples collected during corn planting (4.8–42.3 ng g−1, mean 21.6 ng g−1) and immediately after planting (4.5–60.8 ng g−1, mean 23.6 ng g−1), which also correlated with concentrations detected in pollen trap samples from the same sites (Pearson's r = 0.87, p = 0.0098; Supplemental Data, S6). Two weeks after corn planting, neonicotinoid concentrations in bee bread returned to a lower level (<11.6 ng g−1), except for one site (TV, 35.8 ng g−1).

Concentrations of clothianidin and thiamethoxam in honey were low during all periods (<0.76 ng g−1 total neonicotinoids), though there were positive detections for honey sampled during and after corn planting (Supplemental Data, S4 and S7).

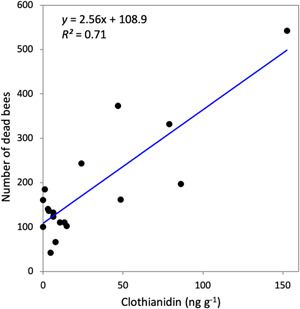

Closed colony experiments

To directly evaluate the effect of seed treatment insecticides in pollen on worker mortality, we conducted a controlled‐feeding experiment where small colonies were fed field‐collected pollen collected from the study apiaries with known concentrations of clothianidin and thiamethoxam. The number of dead bees recorded at the end of 4‐d trials positively correlated with the concentrations of clothianidin (Pearson's r = 0.85, p < 0.001) and thiamethoxam (r = 0.56, p = 0.02) in pollen but not with any of the other insecticides detected in the pollen samples. Initial colony weight correlated with the amount of pollen consumed over the 4‐d period (r = 0.57, p = 0.03), although these parameters did not correlate with dead bee counts (p > 0.60). Linear mixed effect modeling revealed no significant effect of colony weight or pollen consumption on worker bee mortality. Clothianidin concentration alone was the main explanatory variable for worker bee mortality (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The number of dead worker bees in closed‐colony assays increased with the concentration of clothianidin in pollen fed to bees.

Postplanting colony development

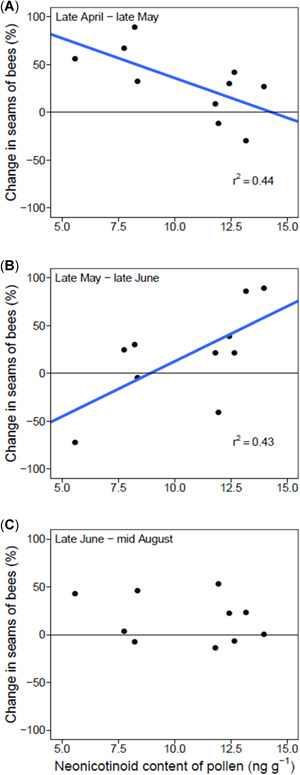

To address the question of whether seed treatment neonicotinoid exposure in May caused longer‐term consequences for colony growth, we tracked 5 hive health metrics (adult bees, pollen stores, nectar stores, open brood, and capped brood; measured by frame area) at 4 time points (April, May, June, and August) in 2015. Exposure to clothianidin and thiamethoxam in May correlated with a reduction in the relative population growth of colonies (measured by area of bees and “seams of bees,” which describes the spaces between frames that are filled with bees) over the earliest time interval (late April to late May; area of bees: t = −3.61, p = 0.01; seams of bees: t = −2.50, p = 0.04; Figure 5A). However, there was an apparent recovery in the second time interval, from late May to late June, because hives exposed to greater neonicotinoid levels in May had a larger increase in adult bee population during this time (for seams of bees only; t = 2.47, p = 0.04; Figure 5B). Finally, in the third time interval, from late June to mid‐August, there was no relationship between neonicotinoids and bee population change (Figure 5C). The cornfield area surrounding apiaries was also positively correlated with increases in stored pollen (Pearson's r = 0.79, p = 0.007) and honey (Pearson's r = 0.68, p = 0.03) during the third interval in summer.

Figure 5.

The relative change in the number of frames occupied by bees plotted against neonicotinoid content over the periods of late April to late May (A), late May to late June (B), and late June to mid‐August (C). Significant relationships are represented by blue regression lines and associated R 2 values.

Of the 38 colonies monitored in 2015, one died in late summer and 3 were relocated and excluded from monitoring over winter. A total of 34 colonies were prepared for overwintering at the end of September 2015, and 31 of those colonies (91%) survived through the end of March 2016, although one of the surviving colonies was queenless. No significant correlation was observed between winter survival and neonicotinoid concentrations in pollen or percentage corn area in the surrounding landscape across the 10 sites (Spearman's rank correlation tests, p > 0.36 for all tests).

DISCUSSION

For 3 yr, we consistently observed elevated mortality in adult honey bee workers during corn planting. This surge of mortality coincided with more frequent detection and higher concentrations of clothianidin and thiamethoxam in pollen collected by honey bees during corn planting. The widespread presence of corn seed treatment insecticides in pollen indicated that the release of seed treatment particles during corn planting is ubiquitous and that released particles are subject to aerial transport, in agreement with previous studies (Schaafsma et al. 2015; Krupke et al. 2017). In addition, our controlled‐feeding study demonstrated that contaminated pollen collected by bees foraging in corn‐dominated landscapes was linked to increased worker bee mortality in honey bee colonies.

Together, these lines of evidence strongly indicate a causal connection between elevated mortality in adult honey bees and seed treatment insecticides emitted during planting. This conclusion is further corroborated by recent work in Italy, where reports of honey bee mortality during corn planting have decreased since the use of neonicotinoid seed treatments was suspended in corn (Sgolastra et al. 2017).

One inconsistency must be considered though. The concentrations of neonicotinoid insecticides detected in pollen samples were below the level that would be expected to cause acute mortality, yet adult mortality was observed in free‐flying colonies during corn planting and in confined colonies fed pollen collected during corn planting. Based on a range of acute oral LD50s for adult workers of 1.11 to 6.76 ng/bee (Laurino et al. 2013) and predicted pollen consumption for nurse bees of 6.5 mg/bee/d (Rortais et al. 2015), substantial mortality would only be expected at concentrations >171 ng/g in pollen. However, neonicotinoid residues detected in bulk pollen samples may not meaningfully reflect doses received by individual bees (Sponsler and Johnson 2017). For example, a bulk pollen concentration of 20 ng/g clothianidin could reflect a uniform distribution of insecticide, or it could reflect a skewed distribution in which one or a few pollen pellets carry very high concentrations while the rest of the pollen is relatively uncontaminated. These 2 distributions would have the same mean concentration but would result in different effects on the colony. The increase in bee mortality that was consistently observed after exposure suggests that many worker bees had ingested a lethal dose of the insecticides. We can therefore infer that the distribution of neonicotinoid concentrations was highly skewed in contaminated pollen.

We found that exposure to corn seed treatment insecticides during planting was associated with changes in colony development. Colonies that collected pollen with greater clothianidin and thiamethoxam contamination in May had slower population growth, as measured by seams of bees and frame area of bees, during this period. However, these colonies appeared to rebound from late May to late June, with faster population growth compared to the colonies in less agricultural landscapes. By the final survey interval, late June to mid‐August, there was no longer an association between insecticide exposure in May and population change. We also did not observe any effect of the exposure on overwinter survival of the colonies. Interestingly, over the summer time frame, colonies surrounded by more cornfields accumulated stored pollen at a faster rate than colonies surrounded by less agricultural landscapes. The increase in food storage may reflect the trend in the Midwest where conventional corn agriculture is typically associated with areas where weedy floral resources such as clovers (Trifolium spp.) thrive at field margins and roadsides, and other summer wildflowers are abundant in less arable lands managed by farmers for Conservation Reserve Programs (Sponsler and Johnson 2015; Sponsler et al. 2017, McMinn‐Sauder et al. 2020). In some areas honey bees are observed to collect pollen from corn during peak bloom (Danner et al. 2014; Wood et al. 2018). The flowering of soybean, which is often planted in rotation with corn, may also provide substantial nectar resources in July (van der Linden 1981; Dolezal et al. 2019). Taken together, these findings suggest that, although the corn‐dominated Midwestern agricultural landscapes may pose risks during the planting season, honey bee colonies may benefit from the abundant supply of floral resources in Ohio's agricultural landscape in summer.

Our data on neonicotinoid residues in food stored by honey bees also suggest that the negative impacts of insecticide exposure during corn planting, while significant at the colony level, are short‐lived. Although high levels of clothianidin and thiamethoxam were detected in bee bread sampled immediately after corn planting, the concentrations declined to the preplanting level within the following week for most sites. Contaminated food stored inside the hives was likely consumed, broken down, or otherwise diluted to lower concentrations as uncontaminated pollen and nectar were brought in after planting.

Although we did not observe long‐term colony‐level effects resulting from corn seed treatment insecticide exposure, the temporary effects we observed may still be detrimental to beekeeping operations. In Ohio corn planting coincides with the critical time when honey bee colonies are recovering from winter and producing large numbers of new worker bees for provision of contracted pollination services or early summer honey production. A sudden increase in worker bee mortality could set back colony development and reduce the economic value of the colony (Khoury et al. 2013; Samson‐Robert et al. 2017). Though not observed in the present study, in extreme scenarios a colony could fall below the collapsing threshold if it is unable to produce enough workers to offset the loss (Samson‐Robert et al. 2017). Other negative impacts of exposure to neonicotinoids have been reported for honey bees and other pollinators. For example, exposure to sublethal levels of clothianidin and thiamethoxam could reduce the reproductive capacity and life span of honey bee queens and drones (Straub et al. 2016; Tsvetkov et al. 2017; but see Cutler and Rix 2015). Clothianidin and thiamethoxam can also affect honey bee immunity against viral diseases (Di Prisco et al. 2013), reduce survival of colonies under nutritional stress (Tosi et al. 2017), and exhibit synergistic toxicity in the presence of other pesticides (Sgolastra et al. 2016; Tsvetkov et al. 2017).

CONCLUSION

The present study confirms that neonicotinoid seed treatment insecticides released during corn planting can enter honey bee colonies through contaminated pollen collected by foraging worker bees. Honey bee colonies exhibited elevated worker bee mortality during planting, corresponding to neonicotinoid insecticide exposure through contaminated pollen. Although the increase in worker bee mortality was linked to a temporary reduction in population growth, no adverse effects were subsequently observed in late summer colony growth or overwinter survival. However, cautionary measures should still be taken to minimize unintended exposure.

Supplemental Data

The Supplemental Data are available on the Wiley Online Library at https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4957.

Disclaimer

This article has been reviewed in accordance with agency policy and approved for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the USEPA.

Supporting information

This article includes online‐only Supplemental Data.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to I. Barnes at Honeyrun Farm, P. Young, T. and F. Davidson, and E. Percel for providing access to colonies and apiary sites; J. Latshaw at Latshaw Apiaries for providing queen cells; and N. Douridas, J. Davlin, and B. Phelps for permission to install colonies near crop fields and providing the time information of planting activities. We thank K. Goodell for access to laboratory space and microscopes and A. Sankey, M. Blackson, S. Suresh, E. Matcham, E. Oltmanns, L. Sethna, J. Rose, H. Rogers, J. Quijia‐Pillajo, N. Riusech, M. Wransky, and G. Cobb for field assistance and sample processing. M. Jones, J. Lanterman, J. Hung, M. Nash, and K. Goodell provided constructive comments that improved the quality of the manuscript. The present study was funded by the Pollinator Partnership Corn Dust Research Consortium and the USEPA's Regional Applied Research Effort (contract EP12W000097), US Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture's Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (2019‐67013‐29297), and state and federal appropriations to the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center (OHO01412 and OHO01355‐MRF). Current address of D.B Sponsler is Department of Animal Ecology and Tropical Biology, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany. Current address of R.T. Richardson is Appalachian Laboratory, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Frostburg, Maryland, USA.

Data Availability Statement

Data, associated metadata, and calculation tools are available from the corresponding author (lin.724@osu.edu).

REFERENCES

- Alix A, Vergnet C, Mercier T. 2009. Risks to bees from dusts emitted at sowing of coated seeds: Concerns, risk assessment and risk management. Julius‐Kühn‐Archiv 423:131–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotti L, Sabatini AG, Mutinelli F, Astuti M, Lavazza A, Piro R, Tesoriero D, Medrzycki P, Sgolastra F, Porrini C. 2009. Spring honey bee losses in Italy. Julius‐Kühn‐Archiv 423:148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Box GE, Tiao GC. 1975. Intervention analysis with applications to economic and environmental problems. J Am Stat Assoc 70:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Camino‐Sánchez FJ, Zafra‐Gómez A, Oliver‐Rodríguez B, Ballesteros O, Navalón A, Crovetto G, Vílchez JL. 2010. UNE‐EN ISO/IEC 17025:2005‐accredited method for the determination of pesticide residues in fruit and vegetable samples by LC‐MS/MS. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 27:1532–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauzat MP, Martel AC, Blanchard P, Clément MC, Schurr F, Lair C, Ribière M, Wallner K, Rosenkranz P, Faucon JP. 2010. A case report of a honey bee colony poisoning incident in France. J Apic Res 49:113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler GC, Rix RR. 2015. Can poisons stimulate bees? Appreciating the potential of hormesis in bee‐pesticide research. Pest Manag Sci 71:1368–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner N, Härtel S, Steffan‐Dewenter I. 2014. Maize pollen foraging by honey bees in relation to crop area and landscape context. Basic Appl Ecol 15:677–684. [Google Scholar]

- Decourtye A, Devillers J. 2010. Ecotoxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides to bees. In Thany SH, ed, Insect Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors, Vol 683—Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Springer‐Verlag, New York, NY, USA, pp 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaplane KS, van der Steen J, Guzman‐Novoa E. 2013. Standard methods for estimating strength parameters of Apis mellifera colonies. J Apic Res 52:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco G, Cavaliere V, Annoscia D, Varricchio P, Caprio E, Nazzi F, Gargiulo G, Pennacchio F. 2013. Neonicotinoid clothianidin adversely affects insect immunity and promotes replication of a viral pathogen in honey bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:18466–18471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal AG, St , Clair AL, Zhang G, Toth AL, O'Neal ME. 2019. Native habitat mitigates feast–famine conditions faced by honey bees in an agricultural landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:25147–25155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas MR, Tooker JF. 2015. Large‐scale deployment of seed treatments has driven rapid increase in use of neonicotinoid insecticides and preemptive pest management in U.S. field crops. Environ Sci Technol 49:5088–5097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forero LG, Limay‐Rios V, Xue Y, Schaafsma A. 2017. Concentration and movement of neonicotinoids as particulate matter downwind during agricultural practices using air samplers in southwestern Ontario, Canada. Chemosphere 188:130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R. 2009. Bee poisoning caused by insecticidal seed treatment of maize in Germany in 2008. Julius‐Kühn‐Archiv 423:126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Giffard H, Dupont T. 2009. A methodology to assess the impact on bees of dust from coated seeds. Julius‐Kühn‐Archiv 423:73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Girolami V, Marzaro N, Vivan L, Mazzon L, Giorio C, Marton D, Tapparo A. 2013. Aerial powdering of bees inside mobile cages and the extent of neonicotinoid cloud surrounding corn drillers. J Appl Entomol 137:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Greatti M, Barbattini R, Stravisi A, Sabatini AG, Rossi S. 2006. Presence of the a.i. imidacloprid on vegetation near corn fields sown with Gaucho® dressed seeds. Bull Insectology 59:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada . 2013. Evaluation of Canadian bee mortalities that coincided with corn planting in spring 2012. Ottawa, Ontario. [cited 2019 December 1]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/reports-publications/pesticides-pest-management/decisions-updates/evaluation-canadian-mortalities-that-coincided-corn-planting-spring-2012.html

- Hitaj C, Smith DJ, Code A, Wechsler S, Esker PD, Douglas MR. 2020. Sowing uncertainty: What we do and don't know about the planting of pesticide‐treated seed. Bioscience 70:390–403. [Google Scholar]

- Human H, Brodschneider R, Dietemann V, Dively G, Ellis JD, Forsgren E, Fries I, Hatjina F, Hu FL, Jaffé R, Jensen AB, Köhler A, Magyar JP, Özkýrým A, Pirk CWW, Rose R, Strauss U, Tanner G, Tarpy DR, van der Steen JJM, Vaudo A, Vejsnæs F, Wilde J, Williams GR, Zheng HQ. 2013. Miscellaneous standard methods for Apis mellifera research. J Apic Res 52:1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury DS, Barron AB, Myerscough MR. 2013. Modelling food and population dynamics in honey bee colonies. PLoS One 8:e59084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupke CH, Holland JD, Long EY, Eitzer BD. 2017. Planting of neonicotinoid‐treated maize poses risk for honey bees and non‐target organisms over a wide area without consistent crop yield benefit. J Appl Ecol 54:1449–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Krupke CH, Hunt GJ, Eitzer BD, Andino G, Given K. 2012. Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS One 7:e29268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurino D, Manino A, Patetta A, Porporato M. 2013. Toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides on different honey bee genotypes. Bull Insectology 66:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- McMinn‐Sauder H, Richardson R, Eaton T, Smith M, Johnson R. 2020. Flowers in Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) pollinator plantings and the upper Midwest agricultural landscape supporting honey bees. Insects 11:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutinelli F, Costa C, Lodesani M, Baggio A, Medrzycki P, Formato G, Porrini C. 2010. Honey bee colony losses in Italy. J Apic Res 49:119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolakis A, Chapple A, Friessleben R, Neumann P, Schad T, Schmuck R, Schnier HF, Schnorbach HJ, Schöning R, Maus C. 2009. An effective risk management approach to prevent bee damage due to the emission of abraded seed treatment particles during sowing of seeds treated with bee toxic insecticides. Julius‐Kühn‐Archiv 423:132–148. [Google Scholar]

- Pistorius J, Bischoff G, Heimbach U, Stähler M. 2009. Bee poisoning incidents in Germany in spring 2008 caused by abrasion of active substance from treated seeds during sowing of maize. Julius‐Kühn‐Archiv 423:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Development Team . 2016. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project, Beaverton, OR, USA. [cited 2019 December 1]. Available from: http://qgis.osgeo.org

- R Development Core Team . 2017. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Rortais A, Arnold G, Halm MP, Touffet‐Briens F. 2015. Modes of honeybees exposure to systemic insecticides: Estimated amounts of contaminated pollen and nectar consumed by different categories of bees. Apidologie 36:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Samson‐Robert O, Geneviève L, Chagnon M, Fournier V. 2017. Planting of neonicotinoid‐coated corn raises honey bee mortality and sets back colony development. PeerJ 5:e3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson‐Robert O, Labrie G, Chagnon M, Fournier V. 2014. Neonicotinoid‐contaminated puddles of water represent a risk of intoxication for honey bees. PLoS One 9:e108443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma A, Limay‐Rios V, Baute T, Smith K, Xue Y. 2015. Neonicotinoid insecticide residues in surface water and soil associated with commercial maize (corn) fields in southwestern Ontario. PLoS One 10:e0118139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnier HF, Wenig G, Laubert F, Simon V, Schmuck R. 2003. Honey bee safety of imidacloprid corn seed treatment. Bull Insectology 56:73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sgolastra F, Medrzycki P, Bortolotti L, Renzi MT, Tosi S, Bogo G, Teper D, Porrini C, Molowny‐Horas R, Bosch J. 2016. Synergistic mortality between a neonicotinoid insecticide and an ergosterol‐biosynthesis‐inhibiting fungicide in three bee species. Pest Manag Sci 73:1236–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgolastra F, Porrini C, Maini S, Bortolotti L, Medrzycki P, Mutinelli F, Lodesani M. 2017. Healthy honey bees and sustainable maize production: Why not? Bull Insectology 70:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sponsler DB, Johnson RM. 2015. Honey bee success predicted by landscape composition in Ohio, USA. PeerJ 3:e838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponsler DB, Johnson RM. 2017. Mechanistic modeling of pesticide exposure: The missing keystone of honey bee toxicology. Environ Toxicol Chem 36:871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponsler DB, Matcham EG, Lin CH, Lanterman JL, Johnson JM. 2017. Spatial and taxonomic patterns of honey bee foraging: A choice test between urban and agricultural landscapes. Journal of Urban Ecology 3:juw008. [Google Scholar]

- Straub L, Villamar‐Bouza L, Bruckner S, Chantawannakul P, Gauthier L, Khongphinitbunjong K, Retschnig G, Troxler A, Vidondo B, Neumann P, Williams GR. 2016. Neonicotinoid insecticides can serve as inadvertent insect contraceptives. Proc R Soc B 283:20160506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomison P. 2015. Getting your corn crop off to a good start in 2015. C.O.R.N. Newsletter 2015–08. The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [cited 2019 November 27]. Available from: https://agcrops.osu.edu/newsletter/corn-newsletter/2015-08/getting-your-corn-crop-good-start-2015

- Tosi S, Nieh JC, Sgolastra F, Cabbri R, Medrzycki P. 2017. Neonicotinoid pesticides and nutritional stress synergistically reduce survival in honey bees. Proc Biol Sci 284:20171711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov N, Samson‐Robert O, Sood K, Patel HS, Malena DA, Gajiwala PH, Maciukiewicz P, Fournier V, Zayed A. 2017. Chronic exposure to neonicotinoids reduces honey bee health near corn crops. Science 356:1395–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Agriculture . 2017. Economics, Statistics and Market Information System. Crop progress. Washington, DC. [cited 2019 December 1]. Available from: https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/8336h188j

- US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service . 2018. CropScape—Cropland data layer. Washington DC. [cited 2019 December 1]. Available from: https://nassgeodata.gmu.edu/CropScape

- US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service . 2019. Crop production: 2018 summary. Washington DC. [cited 2020 March 12] Available from: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Todays_Reports/reports/cropan19.pdf

- US Geological Survey . 2017. Pesticide National Synthesis Project: Estimated annual agricultural pesticide use. Reston, VA. [cited 2019 November 27]. Available from: https://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/pnsp/usage/maps

- van der Geest B. 2012. Bee poisoning incidents in the Pomurje region of eastern Slovenia in 2011. Julius‐Kühn‐Archiv 437:124. [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden JO. 1981. Soybean honey production in Iowa. Am Bee J 121:723. [Google Scholar]

- Wood TJ, Kaplan I, Szendrei Z. 2018. Wild bee pollen diets reveal patterns of seasonal foraging resources for honey bees. Front Ecol Evol 6:210. [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez KP, Martín MT, Bernal JL, Nozal MJ, Bernal J. 2014. Trace analysis of seven neonicotinoid insecticides in bee pollen by solid‐liquid extraction and liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Food Anal Methods 7:490–499. [Google Scholar]

- Žabar R, Komel T, Fabjan J, Kralj MB, Trebše P. 2012. Photocatalytic degradation with immobilised TiO2 of three selected neonicotinoid insecticides: Imidacloprid, thiamethoxam and clothianidin. Chemosphere 89:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This article includes online‐only Supplemental Data.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

Data, associated metadata, and calculation tools are available from the corresponding author (lin.724@osu.edu).