Abstract

Twitter is among the most used online platforms for the political communications, due to the concision of its messages (which is particularly suitable for political slogans) and the quick diffusion of messages. Especially when the argument stimulate the emotionality of users, the content on Twitter is shared with extreme speed and thus studying the tweet sentiment if of utmost importance to predict the evolution of the discussions and the register of the relative narratives. In this article, we present a model able to reproduce the dynamics of the sentiments of tweets related to specific topics and periods and to provide a prediction of the sentiment of the future posts based on the observed past. The model is a recent variant of the Pólya urn, introduced and studied in Aletti and Crimaldi (2019, 2020), which is characterized by a “local” reinforcement, i.e. a reinforcement mechanism mainly based on the most recent observations, and by a random persistent fluctuation of the predictive mean. In particular, this latter feature is capable of capturing the trend fluctuations in the sentiment curve. While the proposed model is extremely general and may be also employed in other contexts, it has been tested on several Twitter data sets and demonstrated greater performances compared to the standard Pólya urn model. Moreover, the different performances on different data sets highlight different emotional sensitivities respect to a public event.

1 Introduction

In the last few years, the internet has become the main source for news for citizens both in EU [1] and in USA [2]. Such a rapid change in the media system has created a symmetric change in the way news are delivered: before the diffusion of the web, information was intermediated by journals, newspapers, radio and TV newscast, that represented the authority, being publicly responsible for the diffusion of reliable news. Nowadays, such intermediation is not present anymore: every blog or account on Facebook or Twitter assumes truthfulness just for existing online [3–6]. Due to this abrupt change of paradigm in the fruition of news, we observe a great increase of the diffusion of misinformation [7–9], that appears on the web via the use of automated [10–16] or genuine accounts [4, 16–20]. It has been observed that the diffusion of disinformation or misinformation campaigns leans on the emotionality of users [3, 4, 6, 21].

Twitter is one of the most famous microblogging service, where people freely express their views and feelings in short messages, called tweets [22]. Twitter is reknown to be used especially for the political communications [23], due to the limited amount of characters, perfectly suitable for political slogans, and for the quick sharing of messages. Due to the availability of its data, via the official API, it represents an extremely rich resource of “spontaneous emotional information” [24]. Sentiment analysis, also known as opinion mining, is a collection of techniques in order to automatically detect the positive or negative connotation of texts. An overview of the latest tools, updates and open issues in sentiment analysis can be found in [25–27] (see also the references therein). Some examples of applications, where predictions are formulated based on the sentiment extracted from on-line texts are provided in [28–35]. In [36], sentiment analysis is used to investigate the emotion transmission in e-communities; while in [37], it is employed in order to investigate on the interplay between macroscopic socio-economic, political or cultural events and the public mood trends, showing that these events have a significant and immediate effect on various aspects of public mood. The Ref. [24] provides a matrix-factorization method to predict individuals’ opinions toward specific topics they had not directly given. In [38], the authors consider the sentiment curve of Twitter posts along time in order to infer the causes of sentiment variations, leveraging on the idea that the emerging topics discussed in the variation period could be highly related to the reasons behind the variations. In [39], the authors present the data prediction as a process based on two different levels of granularity: i) a fine-grained analysis to make tweet-level predictions on various aspects, such as sentiment, topics, volume, location, time-frame, and ii) a coarse-grained analysis to predict the outcome of a real-world event, by aggregating and combining the fine-grained predictions. With respect to this classification, the present work can be placed in the stream of literature regarding the fine-grained analysis to model/predict the sentiment of Twitter posts.

While an important body of research target the issue of predicting the information cascades [40–47], to the best of our knowledge, there are not works that provide models for the evolution of Twitter sentiment. We aim at filling in this gap, presenting a model that is able to reproduce the sentiment curve of the tweets related to specific topics and periods and to provide a prediction of the sentiment of the future posts based on the observed past. We achieve this purpose employing a recent variant of the Pólya urn, introduced in [48] and called Rescaled Pólya (RP) urn. In brief, the RP urn model differs from the standard Pólya urn for the presence of a “local” reinforcement, i.e. elements that are recently observed have a greater impact on the near future and may be identified as the “fashion” of the moment. In the online social networks applications, this local reinforcement aims at representing the persistence of an emotional response to a public event, capturing the phenomenon observed in [3]. Moreover, it is able to correctly reproduce the sentiment dynamics of the tweets, outperforming the standard Pólya urn model, as we will see, on several different data sets. Its prediction ability is also quite high. It is important to note that we also include a delay in information: indeed, it is plausible that, when the user decides to write the tweet posted at time-step n + 1, he /she only knows the previous tweets until a certain time-step t(n)<n.

Finally, we underline that the proposed model may be also employed in other contexts.

The sequel of the work is so structured. In Section 2 we will present the model: after introducing the standard Pólya model in Subsection 2.1, in Subsection 2.2 we formally describe the Rescaled Pólya urn model in general and, then, we focus on the case with two colors and, next to the general model (Complete model), we identify two special cases (“Only fashion” model and “No fashion” model). Finally, in Subsection 2.3, we explain how we include a delay in information. In Section 3, we describe the considered datasets and we illustrate the performed analysis and the obtained results. In Section 4 we comment the results and draw our conclusions. The paper is enriched by an appendix regarding the evolution of the estimated model parameters and additional analyses.

2 Model

2.1 Standard Pólya urn

The standard Pólya urn (see [49–51]) is a stochastic model driven by a reinforcement mechanism (also known as “rich get richer” principle): the probability that a given event occurs increases with the number of times the same event occurred in the past. This rule is a key feature governing the dynamics of many biological, economic and social systems (see, e.g. [51]) and it seems plausible that it plays a role also in the sentiment dynamics of the Twitter posts as the emotional state of an individual influences the emotions of others [36, 52]. The Pólya urn model has been widely studied and generalized (some recent variants can be found in [48, 53–65]) and in its simplest form, with c-colors, works as follows. An urn contains N0i balls of color i, for i = 1, …, c, and, at each discrete time-step, a ball is extracted from the urn and then it is returned inside the urn together with α > 0 additional balls of the same color. Therefore, if we denote by Nni the number of balls of color i in the urn at time-step n, we have

where ξni = 1 if the extracted ball at time-step n is of color i, and ξni = 0 otherwise. The parameter α regulates the reinforcement mechanism: the greater α, the greater the dependence of Nni on .

2.2 Rescaled Pólya (RP) urn

The “Rescaled” Pólya (RP) urn model, introduced in [48], is characterized by the introduction of the parameter β, together with the initial parameters (b0i)i = 1, …, c and (B0i)i = 1, …, c, next to the parameter α of the original model, so that

Therefore, the urn initially contains b0i + B0i > 0 balls of color i and the parameter β ≥ 0, together with α > 0, regulates the reinforcement mechanism. More precisely, the term βBn−1i links Nni to the “configuration” at time-step n − 1 through the “scaling” parameter β, and the term αξni links Nni to the outcome of the extraction at time-step n through the parameter α. Note that the case β = 1 corresponds to the standard Pólya urn with an initial number N0i = b0i + B0i of balls of color i. When β ∈ [0, 1), this variant of the Pólya urn is characterized by a “local” reinforcement, i.e. a reinforcement mechanism mainly based on the most recent observations, and by a random persistent fluctuation of the predictive mean ψni = E[ξn+1i = 1 |“past”]. As we will show, this latter feature is capable of capturing the trend fluctuations in the sentiment curve of Twitter posts (see Figs 1–6).

Fig 1. “Migration” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

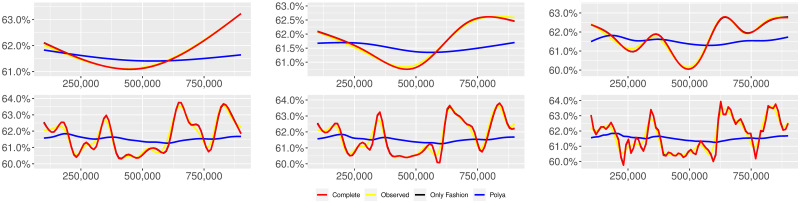

Fig 6. “Covid” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D′ = 3, S = 1000 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves for BOTs’ posts.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

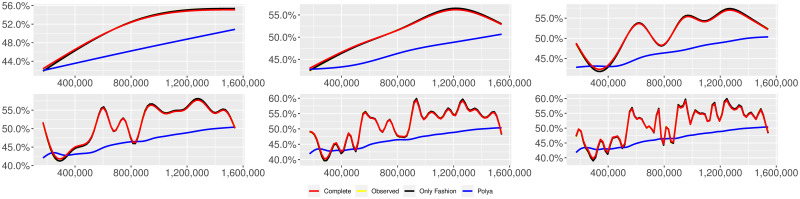

Fig 2. “Migration” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves for BOTs’ posts.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 3. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 4. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves for BOTs’ postsx.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 5. “Covid” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, S = 1000 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

More formally, given a vector , we define . Moreover, we set b0 = (b01, …, b0c)⊤ and B0 = (B01, …, B0c)⊤, we assume |b0|>0 and we define . At each discrete time-step (n + 1)≥1, a ball is drawn at random from the urn, obtaining the random vector ξn+1 = (ξn+11, …, ξn+1c)⊤ defined as

The number of balls in the urn is so updated:

| (1) |

which gives (since |ξn+1| = 1)

| (2) |

Therefore, setting , we get

| (3) |

Moreover, denoting by the filtration representing the information along time-steps (formally, this means to set equal to the trivial σ-field and for n ≥ 1), the conditional probabilities ψn = (ψn1, …, ψnc)⊤ of the extraction process, also called predictive means, are

| (4) |

This urn model has been studied in [48, 53]. All the mathematical proofs and details can be found in these papers.

2.2.1 Two colors (c = 2)

With two colors, the quantity of interest are only ξn = ξn1 = 1 − ξn2 and ψn = ψn1 = 1 − ψn2. In the sequel, we consider the RP urn model with β = 1 (i.e. the standard Pólya urn model) and with β < 1. In the first case, we have

In the second case, by (1), (2), (3) and (4), using , we obtain

and

Since β < 1, the dependence of ψn on ξh exponentially increases with h, because of the factor βn−h, and so the main contribution is given by the most recent extractions. We refer to this phenomenon as “local” reinforcement. The case β = 0 is an extreme case, for which ψn depends only on the last extraction ξn. Note that, when β = 1, i.e. the case of the standard Pólya urn, all the past observations ξh equally contribute to ψn, with a weight equal to α. This different dependence on the past leads to a different behaviour of ψn along time-steps (see [48]): in the standard Pólya urn, the process (ψn) asymptotically stabilizes, converging almost surely toward a random variable, while in the RP urn, the process (ψn) persistently fluctuates (see Figs 1–6).

If we set

we get for a large n

and

Summing up, the model dynamics can be approximated for n large by

where are the parameters. Note that α does not appear among the parameters for the above approximated dynamics, but it is included in the new parameter γ*. Moreover, the quantity is exponentially fast negligible, because we have , with β < 1. Therefore, the fundamental parameters are p0, γ* and β: p0 is a deterministic component, γ* tunes the weight in the predictive mean ψn+1 of the random “fluctuation” component with respect to the deterministic one, and β regulates the dependence of the present state on the previous state and on the present observation ξn+1. We refer to as the “fashion” process, since it reproduces the trend variations of the considered phenomenon (in our case, the sentiment of Twitter posts). In the following applications, we consider the following cases:

Complete RP model: The three parameters θ = (p0, γ*, β) are free to vary.

“Only Fashion” RP model: γ* = 1 (and p0 = 0 irrelevant). This means that the predictive mean is not driven by any deterministic component, but it coincides with the fashion process. The free parameter is given by θ = β.

“No Fashion” RP model: γ* = 0 (and β = 0 irrelevant). In this case ψn is equal to the constant p0 and, consequently, the free parameter is given by θ = p0.

2.3 Model with delay

In applications, the extractions from the urn typically correspond to actions performed by agents. Therefore, it is plausible that there is a delay in information, in the sense that, when the agent decides to make the action that will appear at time-step n + 1, he/she only knows what happened until a certain time-step t(n)<n, i.e. the actions at time-steps 1, …, t(n). For instance, in our framework, the actions are the tweets and so it is plausible that, when the author of the tweet posted at time-step n + 1 is writing, he /she only knows the previous tweets until a certain time-step t(n)<n. In other words, we can image that an agent, after reading the tweets posted until time-step t(n), starts to write his/her tweet and posts it at time-step n + 1. Therefore, tweet n + 1 is not affected by tweets posted at time-steps t(n) + 1, …, n. When this is the case, the predictive means for action n + 1 are given by the composition of the urn until time-step t(n). In particular, if the number of colors is c = 2 and we denote by the information the agent has when performing action n + 1 (formally, equal to the trivial σ-field and ), we have

| (5) |

Assuming to know the real time at which actions appeared (i.e., in our framework, the real time at which the posts are posted), a possible way to define t(n) is the following. Fix a value D > 0, divide (real) time in blocks of length D (choose D so that the blocks contain at least one action), define j(n + 1) the index of the time block containing the action n + 1 and set

It follows that, for all actions appeared in a certain time block j, the missing information are the actions appeared in the immediately previous time block (i.e. block j − 1) plus the preceding actions of the same block. As a consequence, the quantity D is a lower bound for the delay and 2D an upper bound: agents looses at least D units of time and not more than 2D units of time.

In the following, we refer to this variant of the RP urn as “RP urn model with delay”.

3 Results

3.1 Data

Data have been collected from the Twitter platform, using the official API to Stream the exchange of messages on several topics. In the following, the various datasets are described in more details:

-

Italy, Migration debate

Data were collected through the Filter API since 23rd of January to 22nd of February 2019 and targeted the Italian debate on migration. Data were previously analysed in [16]. In the dataset, the information about the nature, automated or not (BOT or not), of the users is present. The BOT detection algorithm embedded is a lightweight version of the classifier proposed in [10]; more details on the dataset can be found in [16].

-

Italy, 10 days of traffic

The dataset collects the entire traffic, compatibly with the Filter API sampling, of messages in Italian in the days from the first to the 10th of September 2019: the keyword used for the query were the Italian vowels, in order to collect all messages that may contain some word. In the dataset, the information about the nature, automated or not (BOT or not), of the users is present. The BOT detection algorithm used was developed in [14].

-

Italy, COVID-19 epidemic

The dataset covers the period from February 21st to April to 20th 2020, including tweets in Italian language, and was previously analysed in [20]. The keywords used for the query are relative to the COVID-19 epidemic; more details can be found in the original reference. The dataset includes information on the automated or not (BOT or not) nature of the accounts, detected using the algorithm developed in [14].

For every message, the relative sentiment was calculated using the polyglot python module developed in [66], that provides a numerical value v ∈ [−1, 1] for the sentiment. We fix a threshold T = 0.35 so that we classify as a tweet with positive sentiment those with v > T and as a tweet with negative sentiment those with v < −T. We discard tweets with a value v ∈ [−T, T]. (There is not a particular reason for our choice of the value of T: indeed, we take the value 0.35 only because the interval [−1, 1] results divided into three parts of almost the same length. In Appendix, Sec. B, we show the results for other values of the threshold T).

Tables 1–3 show some descriptives of the samples obtained with T = 0.35:

Table 1. “Migration” sample: Descriptives of the sample obtained with T = 0.35.

| Migration | Entire | Only BOTs’ posts |

|---|---|---|

| Posts | 367367 | 4124 |

| Percentage of positive posts | 49.60% | 47.97% |

Table 3. “Covid” sample: Descriptives of the sample obtained with T = 0.35.

| Covid | Entire | Only BOTs’ posts |

|---|---|---|

| Posts | 2037584 | 48252 |

| Percentage of positive posts | 50.58% | 54.00% |

Table 2. “10 days of traffic” sample: Descriptives of the sample obtained with T = 0.35.

| 10 days of traffic | Entire | Only BOTs’ posts |

|---|---|---|

| Posts | 3164620 | 102374 |

| Percentage of positive posts | 63.26% | 63.79% |

3.2 Analysis of the prediction ability

We apply the RP urn model with delay, ordering the tweets according to their creation time and taking each tweet with a positive/negative classification as an extraction in the urn model. More precisely, we apply the RP model with c = 2: the time series of the tweets represents the time series of the extractions from the urn, that is the random variables ξn. The event {ξn = 1} means that tweet n exhibits a positive sentiment, while {ξn = 0} means that tweet n exhibits a negative sentiment. Moreover, we include a delay into the model as described in Subsec. 2.3, taking D = 3 minutes for the “migration” and “covid” samples and D = 30 seconds for the “10 days of traffic” sample. These values have been arbitrarily chosen, because we have no information about the real length of the delay. Notably, no significant difference has been observed taking zero delay.

The model parameters have been estimated by maximum likelihood. More precisely, we have divided the available N (ordered) actions (i.e. the tweets) into S slots of the same size (numbered from s = 0 to s = S − 1). For each slot s = 1, …, S − 1, with training data of the slots s′ = 0, …, s − 1, we have estimated the best parameters for the different proposed models (with delay): Standard Pólya, Complete RP, Only Fashion RP, No Fashion RP. (See Appendix, Sec. A, for a deeper exploration of the evolution of the parameters and further comments.) With these parameters, for each action ξn+1 of the s-th slot, we have computed the conditional probability (see Eq 5), that is the predictive mean for action n + 1, as a function of the estimated parameters and of the actions ξ1, …, ξt(n) (that is the information of the author of action n + 1). The predictive mean represents our prediction of the future action ξn+1. We have quantified the ability of the considered model to predict the future outcomes by means of the relative Squared Error (SErel) with respect to the method that predicts the future outcome taking the value assumed by the majority in the past. More precisely, we have computed the following quantity:

| (6) |

where the sum is over all the observations except the ones in slot s = 0 and mn is the value assumed by the majority of the past actions ξ1, …, ξt(n).

This quantity measures the ability of the model to predict the future outcomes: the greater it is, the better is the prediction with respect to the method based on the past majority. The values SErel obtained for the different considered models are also compared with the “theoretical” value of SErel computed replacing by the mean value on all the considered period. The term “theoretical” is used in order to point out that is of course not a prediction, but it gives the a posteriori best constant fit once we have collected all the data until time-step N. Summing up, our aim is twofold: to obtain a value of SErel greater than 1, that means that the considered models beat the performance of the method based on the past majority, and to get a value greater or equal to the “theoretical” value, that means that the proposed models perform better or similarly than the (theoretical) a posteriori best constant fit.

We summarize the results in Tables 4–6. For each considered sample, we have also analysed the subset obtained by the restriction to the tweets classified as sent by a BOT. In the tables the best values are highlighted in bold. We can observe that, for the “Migration” and “covid” samples, the considered models perform more or less two times better than the method based on the past majority and this performance is similar to (indeed, in the most cases slightly better than) the one given by the (theoretical) a posteriori best constant fit. For the “10 days traffic” sample, the performance of the considered models is one and half times better than the method based on the past majority and this performance is similar to the one given by the (theoretical) a posteriori best constant fit. Moreover, the performances of the “Complete RP” model and of the “Only fashion RP” model do not significantly differ; while the “No Fashion RP” model performs less well. Therefore, in the next subsection, we will discard this last model.

Table 4. “Migration” sample (T = 0.35, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Comparison of the different considered models in terms of (6).

| Migration | Standard Pólya | Complete RP | Only Fashion RP | No Fashion RP | Theoretical value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire | 200.91% | 206.28% | 206.22% | 200.78% | 200.93% |

| OnlyBOT | 194.52% | 199.63% | 199.75% | 194.24% | 194.74% |

Table 6. “Covid” sample (T = 0.35, D = 3′, S = 1000 slots of equal size): Comparison of the different considered models in terms of (6).

| Covid | Standard Pólya | Complete RP | Only Fashion RP | No Fashion RP | Theoretical value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire | 199.97% | 203.15% | 203.15% | 199.96% | 200.02% |

| OnlyBOT | 187.60% | 190.43% | 190.47% | 187.58% | 187.85% |

Table 5. “10 days of traffic” sample (T = 0.35, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Comparison of the different considered models in terms of (6).

| 10 days of traffic | Standard Pólya | Complete RP | Only Fashion RP | No Fashion RP | Theoretical value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire | 160.75% | 160.88% | 160.88% | 160.74% | 160.75% |

| OnlyBOT | 159.57% | 159.70% | 159.62% | 159.57% | 159.58% |

(In Appendix, Sec. B, we collect results obtained with different thresholds T (used for the construction of the sample) and taking the slots (used for the parameters estimation) equal to the available days of observation).

3.3 Fluctuations of the sentiment curve

We provide some tables and figures in order to point out how the different considered models are able to reproduce the trend fluctuation of the sentiment curve. More precisely, in Figs 1–6, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing (Penalized Cubic regression splines with different numbers of nodes: k = 3, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50. See [67]) of the time series of the observed tweets {ξn: n = 1, …, N}, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing (with the same number of nodes) of the time series of the estimated predictive means (see Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model with delay, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models with delay: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In Tables 7–12, we compare the different models by means of the Mean Squared Error (MSE), i.e.

| (7) |

where the sum is over all the observations except the ones in the slot s = 0 and ξn+1 and refer to the values on the curves with a given smoothing.

Table 7. “Migration” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.44 × 10−1 | 2.43 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.44 × 10−9 | 1.41 × 10−6 | 3.03 × 10−4 |

| k = 5 | 1.19 × 10−8 | 3.23 × 10−6 | 3.43 × 10−4 |

| k = 10 | 2.64 × 10−7 | 1.74 × 10−5 | 1.64 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 1.04 × 10−6 | 2.98 × 10−5 | 2.73 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 2.79 × 10−6 | 4.03 × 10−5 | 3.83 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 7.18 × 10−6 | 5.41 × 10−5 | 4.85 × 10−3 |

Table 12. “Covid” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 3′, S = 1000 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing).

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.45 × 10−1 | 2.45 × 10−1 | 2.49 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.23 × 10−6 | 5.33 × 10−5 | 3.38 × 10−3 |

| k = 5 | 1.16 × 10−5 | 5.16 × 10−5 | 3.38 × 10−3 |

| k = 10 | 2.84 × 10−5 | 6.88 × 10−5 | 3.53 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 5.70 × 10−5 | 9.78 × 10−5 | 3.80 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.67 × 10−4 | 1.81 × 10−4 | 4.01 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 3.05 × 10−4 | 2.94 × 10−4 | 4.38 × 10−3 |

Table 8. “Migration” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.43 × 10−1 | 2.41 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 2.62 × 10−6 | 3.56 × 10−5 | 7.66 × 10−4 |

| k = 5 | 4.19 × 10−4 | 1.90 × 10−4 | 1.10 × 10−3 |

| k = 10 | 1.03 × 10−4 | 3.50 × 10−4 | 3.36 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 5.36 × 10−4 | 8.19 × 10−4 | 6.58 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 9.09 × 10−4 | 1.22 × 10−3 | 9.13 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 2.53 × 10−3 | 2.36 × 10−3 | 1.34 × 10−2 |

Table 9. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.33 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.15 × 10−9 | 2.61 × 10−7 | 1.22 × 10−5 |

| k = 5 | 3.86 × 10−9 | 8.09 × 10−7 | 3.34 × 10−5 |

| k = 10 | 1.94 × 10−8 | 2.02 × 10−6 | 6.88 × 10−5 |

| k = 20 | 7.81 × 10−8 | 2.65 × 10−6 | 8.80 × 10−5 |

| k = 30 | 1.74 × 10−7 | 2.86 × 10−6 | 9.65 × 10−5 |

| k = 50 | 1.08 × 10−6 | 5.15 × 10−6 | 1.53 × 10−4 |

Table 10. “10 days traffic” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.31 × 10−1 | 2.31 × 10−1 | 2.31 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 4.10 × 10−7 | 6.67 × 10−7 | 5.73 × 10−6 |

| k = 5 | 7.95 × 10−7 | 2.02 × 10−5 | 5.97 × 10−5 |

| k = 10 | 6.81 × 10−6 | 2.35 × 10−5 | 7.19 × 10−5 |

| k = 20 | 1.59 × 10−5 | 5.43 × 10−5 | 1.52 × 10−4 |

| k = 30 | 2.59 × 10−5 | 5.98 × 10−5 | 1.75 × 10−4 |

| k = 50 | 9.80 × 10−5 | 1.23 × 10−4 | 3.49 × 10−4 |

Table 11. “Covid” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, S = 1000 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.98 × 10−8 | 7.37 × 10−6 | 2.58 × 10−3 |

| k = 5 | 5.51 × 10−8 | 7.53 × 10−6 | 2.64 × 10−3 |

| k = 10 | 1.54 × 10−7 | 8.63 × 10−6 | 2.92 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 7.93 × 10−7 | 9.37 × 10−6 | 3.10 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.06 × 10−6 | 9.80 × 10−6 | 3.24 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 2.06 × 10−6 | 1.10 × 10−5 | 3.46 × 10−3 |

We can observe that, as explained before in Section 2.2, the RP urn model is able to reproduce the fluctuations of the observed sentiment curve, while the standard Pólya urn model produces a curve that converges to a value.

(In Appendix, Sec. B, we collect results obtained with different thresholds T (used for the construction of the sample) and taking the slots (used for the parameters estimation described in Subsec. 3.2) equal to the available days of observation).

4 Discussion and conclusions

Online Social Networks (OSN) represent a perfect environment for the study of the emotional reaction to public events. It has been observed that the sentiment of a message may be a driver for the diffusion of a message in online social networks [3, 4, 6, 21]. Interestingly, Ref. [3] shows that, on different arguments, the sensitivity, i.e. the emotional reaction to the event, finds a sort of stability.

Leveraging on this feature of the online debate, we apply here a modification of the Pólya urn model, embedding a “local” reinforcement effect [48, 53], representing a sort of “fashion” contribution and capturing the persistence of a common sentiment. Similarly to the standard Pólya urn, the future outcome depends on the past history, but, differently from the original model, in the Rescaled Pólya urn, the influence of the recent outcomes has a greater impact on future extractions. This represents the “fashion” effect and its introduction properly captures the evolution of the sentiment of the online debate. We also include in the model a delay in information as described in Subsection 2.3, introducing the Rescaled Pólya urn with delay.

The results collected in Subsection 3.3 show that indeed the Rescaled Pólya model outperforms greatly the standard Pólya model. Moreover, as shown in Subsection 3.2, the RP urn model permits to have reliable predictions from past observations. As told before, the employed model incorporates itself a delay in information and, in addition, the model parameters are fitted using the data from all the previous slots. As it can be observed from the evolution of the model parameters, all of them converge smoothly to a fixed value. Estimating the parameters using only the closest slots, is going to be the target of near future research, together with the examination of different definitions of the delay included in the model.

Summarising, the present paper has essentially two targets: to propose a novel model for the reproduction and the prediction of the sentiment in the online debate and to examine and study the implications of the Rescaled Pólya urn (with delay). Building a simple and realistic model improves our understanding of the phenomenon: in the particular case, the presence of a local reinforcement, i.e. the “fashion” effect described above, shows how persistent is the emotional reaction to a public event.

It is worth to be mentioned that the application to Online Social Media is one of the possible applications of the proposed model: due to its abstractness and generality, it can be applied to any kind of phenomenon showing a local “fashion” behaviour.

The Rescaled Pólya model is defined for any number c of colors. Therefore it is also possible to take into account the previously discarded tweets, say the “neutral” ones, i.e. those with sentiment between −0.35 and 0.35 (more generally, between −T and T). However, it is out of the scope of the present study. We do not think that taking into account more colors could produce a different finding. Indeed, the additional analyses related to different thresholds show that the choice of the threshold does not modify the essence of the outputs.

Appendix

A Parameters evolution

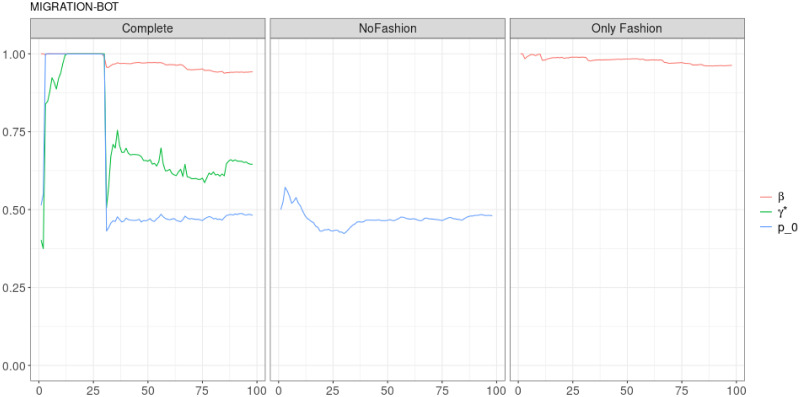

As it is mentioned in the main text, in order to fit the parameters of the model, we divided the entire sample in slots of the same size (the number S of slots and their size for each considered sample is specified in the captions of the figures). Next, we use all slots previous to the one under consideration to fit the parameters. In this sense, we observe an evolution of the parameters as a matter of the evolution of the samples, which is different when focusing on the different nature of users in the debate. Such a difference is particularly evident in the Migration debate. Human accounts show a nearly constant parameter dynamics: while β is nearly constant in the Complete model, γ* and p0 display a smooth slow variation of nearly the 10% of their value, see Fig 7. The dynamics of the parameters for automated accounts is completely different, see Fig 8: in the Complete model, while β is slowly decreasing (but still experiencing a much greater decrease than the one observed for human accounts), parameters γ* and p0 display a step-like dynamics, ending shortly after s = 25.

Fig 7. “Migration” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′): Model parameters evolution with S = 100 slots of equal size (i.e. 3673 observations).

All parameters are slowly varying and converging to stable values.

Fig 8. “Migration” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 3′): Model parameters evolution with S = 100 slots of equal size (i.e. 41 observations).

In the left panel, it is possible to distinguish an “Only fashion” initial phase (γ* ≃ 1) and more balanced phase (γ* ∈ [0.5, 0.75]).

A similar, but less evident, dynamics can be observed in the “10 days of traffic” sample, see Figs 9 and 10: in this case, all parameters converge to 1 quite soon in the case of the entire sample. Instead, we can see that p0 converge, but to something more than 0.6 quite immediately for the social bot subset, while the value of γ* oscillates between 0.5 and 0, before converging to something less than 0.4. The parameter β is nearly 1 for both cases.

Fig 9. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 30′′): Model parameters evolution with S = 100 slots of equal size (i.e. 31646 observations).

All parameters for the complete model converge to 1 quite soon. With γ* ≃ 1, the Complete model is practically equivalent to the “Only Fashion” one.

Fig 10. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 30′′): Model parameters evolution with S = 100 slots of equal size (i.e. 1023 observations).

Every parameter of the complete model, but γ*, are essentially constant. Let us remark that γ* tunes the weight of the fashion process in the predictive mean.

In the case of the online debate during the COVID-19 epidemic, Figs 11 and 12, the differences are extremely low, with the values of γ* quite flickering before converging to a value little lower than the one obtained for the entire sample. All other parameters are quite similar, both in the value and in the dynamics.

Fig 11. “Covid” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′): Model parameters evolution with S = 1000 slots of equal size (i.e. 2037 observations).

All parameters are nearly constant or slowly converging.

Fig 12. “Covid” (T = 0.35, only BOTs’ posts, D = 3′): Model parameters evolution with S = 1000 slots of equal size (i.e. 48 observations).

Differently to the other samples, the parameters evolution for the Bots’ posts follows the one for the entire sample, displaying a greater noise contribution for γ*.

It is worthwhile to point out that, when we deal with the entire samples, the size of each slot is large enough in order to estimate properly the parameters from the very beginning. Therefore, we can guess that the behaviours of the curves in Figs 7, 9 and 11, before the stabilization, are really related to the dynamics of the debates. The situation is different when we deal only with posts sent by BOTs. Indeed, in this case, the initial estimation of the parameters may be affected by the limited size of the slots. However, also Figs 8, 10 and 12 exhibits a final stabilization of the values. An open question is if the differences in the values of the parameters and in their long-term dynamics observed when comparing the entire sample and the subset of BOTs’ posts is due to the different sizes or to an indeed different dynamics. This issue is not the focus of this work and it is going to be the target of further analyses.

B Additional analyses

We here collect the outputs of some additional analyses related to different choices of the threshold T for the construction of the sample and to a different partition into slots associated to the applied estimation technique for the model parameters. More precisely, we perform the analyses described in Subsecs. 3.2 and 3.3 for other two different thresholds (i.e. T = 0.5 and T = 0) and also taking the slots equal to the available days of observation. Table 13 reports the values of the indicator defined in Subsec. 3.2, Eq (6). Tables 14–25 and Figs 13–24 illustrate the results of the analyses described in Subsec. 3.3. We can observe that the main finding of this work does not change: indeed, since its local reinforcement mechanism, the RP urn model (with delay) is able to reproduce the fluctuations of the observed sentiment curve.

Table 13. Comparison of the different considered models in terms of (6).

| Sample | Standard Pólya | Complete RP | Only Fashion RP | No Fashion RP | Theoretical value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migration (T = 0, D = 3’, S = 100) | 202.23% | 202.25% | 202.22% | 202.22% | 202.23% |

| Migration (T = 0.5, D = 3’, S = 100) | 194.48% | 194.51% | 194.48% | 194.48% | 194.48% |

| Migration (T = 0.35, D = 3’, slots = days) | 198.84% | 203.11% | 203.46% | 198.02% | 198.86% |

| Migration (T = 0.5, D = 3’, slots = days) | 192.67% | 198.40% | 198.78% | 191.10% | 192.70% |

| 10 days traffic (T = 0, D = 30”, S = 100) | 165.68% | 165.79% | 165.79% | 165.68% | 165.68% |

| 10 days traffic (T = 0.5, D = 30”, S = 100) | 160.18% | 160.32% | 160.32% | 160.17% | 160.18% |

| 10 days traffic (T = 0.35, D = 30”, slots = days) | 158.10% | 158.23% | 158.23% | 158.08% | 158.10% |

| 10 days traffic (T = 0.5, D = 30”, slots = days) | 157.50% | 157.64% | 157.64% | 157.48% | 157.50% |

| Covid (T = 0, D = 3’, S = 100) | 201.60% | 204.33% | 204.33% | 201.51% | 201.70% |

| Covid (T = 0.5, D = 3’, S = 100) | 199.04% | 202.24% | 202.25% | 198.91% | 199.10% |

| Covid (T = 0.35, D = 3’, slots = days) | 198.01% | 201.08% | 201.11% | 197.82% | 198.01% |

| Covid (T = 0.5, D = 3’, slots = days) | 197.10% | 200.20% | 200.23% | 196.85% | 197.10% |

Table 14. “Migration” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.50 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.58 × 10−7 | 5.37 × 10−7 | 5.79 × 10−6 |

| k = 5 | 4.13 × 10−7 | 5.36 × 10−7 | 8.22 × 10−6 |

| k = 10 | 9.97 × 10−6 | 6.04 × 10−7 | 9.65 × 10−6 |

| k = 20 | 1.10 × 10−5 | 2.11 × 10−5 | 2.91 × 10−5 |

| k = 30 | 2.29 × 10−5 | 3.48 × 10−5 | 4.36 × 10−5 |

| k = 50 | 3.44 × 10−5 | 4.51 × 10−5 | 5.73 × 10−5 |

Table 25. “Covid” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 4.50 × 10−8 | 8.47 × 10−6 | 2.37 × 10−3 |

| k = 5 | 5.77 × 10−8 | 8.58 × 10−6 | 2.42 × 10−3 |

| k = 10 | 1.39 × 10−7 | 1.04 × 10−5 | 2.84 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 1.14 × 10−6 | 1.20 × 10−5 | 3.12 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.53 × 10−6 | 1.24 × 10−5 | 3.22 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 2.84 × 10−6 | 1.40 × 10−5 | 3.49 × 10−3 |

Fig 13. “Migration” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 24. “Covid” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 14. “Migration” (T = 0, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 15. “Migration” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 16. “Migration” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 17. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 18. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0, entire, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 19. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 30′′, slots = days): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 20. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 30′′y, slots = days): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 21. “Covid” (T = 0.5, entire, *D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 22. “Covid” (T = 0, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Fig 23. “Covid” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): Sentiment curves.

In each panel, the yellow line is the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the observed tweets ξn+1, together with the default confidence interval (gray), the red line represents the cubic spline smoothing of the time series of the estimated predictive means (defined in Subsec. 3.2), obtained with the complete RP model, the black and the blue lines provide similar approximations obtained with the other models: black = Only fashion RP model and blue = Standard Pólya model. In each panel, the smoothing is obtained with a given number of nodes: k = 3 (top left panel), 5 (top middle panel), 10 (top right panel), 20 (bottom left panel), 30 (bottom middle panel), 50 (bottom right panel).

Table 15. “Migration” (T = 0, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.50 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 1.96 × 10−8 | 1.20 × 10−6 | 3.31 × 10−6 |

| k = 5 | 1.77 × 10−7 | 9.52 × 10−7 | 4.03 × 10−6 |

| k = 10 | 3.70 × 10−6 | 9.94 × 10−7 | 4.20 × 10−6 |

| k = 20 | 4.29 × 10−6 | 7.86 × 10−6 | 1.12 × 10−5 |

| k = 30 | 5.79 × 10−6 | 9.84 × 10−6 | 1.37 × 10−5 |

| k = 50 | 1.26 × 10−5 | 1.79 × 10−5 | 2.36 × 10−5 |

Table 16. “Migration” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.44 × 10−1 | 2.44 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 7.26 × 10−8 | 1.76 × 10−6 | 3.01 × 10−4 |

| k = 5 | 1.10 × 10−7 | 4.16 × 10−6 | 3.43 × 10−4 |

| k = 10 | 1.24 × 10−6 | 2.84 × 10−5 | 1.64 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 5.41 × 10−6 | 5.01 × 10−5 | 2.74 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.20 × 10−5 | 6.92 × 10−5 | 3.84 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 2.59 × 10−5 | 9.73 × 10−5 | 4.87 × 10−3 |

Table 17. “Migration” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.42 × 10−1 | 2.42 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 2.66 × 10−7 | 2.29 × 10−6 | 3.56 × 10−4 |

| k = 5 | 6.47 × 10−7 | 2.49 × 10−6 | 3.75 × 10−4 |

| k = 10 | 2.75 × 10−6 | 3.75 × 10−5 | 2.79 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 6.37 × 10−6 | 5.80 × 10−5 | 3.92 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.66 × 10−5 | 8.32 × 10−5 | 5.33 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 3.15 × 10−5 | 1.09 × 10−4 | 6.54 × 10−3 |

Table 18. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.32 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 4.32 × 10−8 | 4.49 × 10−8 | 7.88 × 10−6 |

| k = 5 | 5.40 × 10−9 | 6.29 × 10−9 | 5.56 × 10−5 |

| k = 10 | 1.43 × 10−8 | 1.70 × 10−8 | 7.56 × 10−5 |

| k = 20 | 6.65 × 10−8 | 8.04 × 10−8 | 9.78 × 10−5 |

| k = 30 | 2.62 × 10−7 | 2.89 × 10−7 | 1.04 × 10−4 |

| k = 50 | 1.00 × 10−6 | 1.20 × 10−6 | 1.53 × 10−4 |

Table 19. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0, entire, D = 30′′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.37 × 10−1 | 2.37 × 10−1 | 2.37 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 6.56 × 10−9 | 5.77 × 10−9 | 3.68 × 10−5 |

| k = 5 | 7.12 × 10−9 | 5.97 × 10−9 | 5.20 × 10−5 |

| k = 10 | 1.86 × 10−8 | 1.62 × 10−8 | 6.71 × 10−5 |

| k = 20 | 7.66 × 10−8 | 6.46 × 10−8 | 7.92 × 10−5 |

| k = 30 | 2.69 × 10−7 | 2.44 × 10−7 | 8.49 × 10−5 |

| k = 50 | 1.23 × 10−6 | 1.02 × 10−6 | 1.25 × 10−4 |

Table 20. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 30′′, slots = days): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.33 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.15 × 10−9 | 2.63 × 10−7 | 1.22 × 10−5 |

| k = 5 | 3.86 × 10−9 | 8.15 × 10−7 | 3.34 × 10−5 |

| k = 10 | 1.94 × 10−8 | 2.03 × 10−6 | 6.88 × 10−5 |

| k = 20 | 7.81 × 10−8 | 2.68 × 10−6 | 8.80 × 10−5 |

| k = 30 | 1.74 × 10−7 | 2.88 × 10−6 | 9.65 × 10−5 |

| k = 50 | 1.08 × 10−6 | 5.19 × 10−6 | 1.53 × 10−4 |

Table 21. “10 days of traffic” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 30′′, slots = days): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.32 × 10−1 | 2.32 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 4.32 × 10−8 | 1.62 × 10−7 | 7.88 × 10−6 |

| k = 5 | 5.40 × 10−9 | 1.94 × 10−6 | 5.56 × 10−5 |

| k = 10 | 1.43 × 10−8 | 2.71 × 10−6 | 7.56 × 10−5 |

| k = 20 | 6.65 × 10−8 | 3.65 × 10−6 | 9.78 × 10−5 |

| k = 30 | 2.62 × 10−7 | 3.58 × 10−6 | 1.04 × 10−4 |

| k = 50 | 1.00 × 10−6 | 5.86 × 10−6 | 1.53 × 10−4 |

Table 22. “Covid” (T = 0.5, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 4.50 × 10−8 | 8.40 × 10−6 | 2.37 × 10−3 |

| k = 5 | 5.77 × 10−8 | 8.51 × 10−6 | 2.42 × 10−3 |

| k = 10 | 1.39 × 10−7 | 1.03 × 10−5 | 2.84 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 1.14 × 10−6 | 1.19 × 10−5 | 3.12 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.53 × 10−6 | 1.23 × 10−5 | 3.22 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 2.84 × 10−6 | 1.39 × 10−5 | 3.49 × 10−3 |

Table 23. “Covid” (T = 0, entire, D = 3′, S = 100 slots of equal size): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.47 × 10−1 | 2.47 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.20 × 10−8 | 4.23 × 10−6 | 2.37 × 10−3 |

| k = 5 | 4.57 × 10−8 | 4.32 × 10−6 | 2.40 × 10−3 |

| k = 10 | 2.09 × 10−7 | 5.23 × 10−6 | 2.65 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 7.14 × 10−7 | 5.56 × 10−6 | 2.72 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.04 × 10−6 | 6.02 × 10−6 | 2.89 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 1.70 × 10−6 | 6.91 × 10−6 | 3.06 × 10−3 |

Table 24. “Covid” (T = 0.35, entire, D = 3′, slots = days): MSE for different levels of smoothing.

| smoothing | Only Fashion RP | Complete RP | Standard Pólya |

|---|---|---|---|

| no smooth | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.46 × 10−1 | 2.50 × 10−1 |

| k = 3 | 3.98 × 10−8 | 7.43 × 10−6 | 2.58 × 10−3 |

| k = 5 | 5.51 × 10−8 | 7.59 × 10−6 | 2.64 × 10−3 |

| k = 10 | 1.54 × 10−7 | 8.70 × 10−6 | 2.92 × 10−3 |

| k = 20 | 7.93 × 10−7 | 9.44 × 10−6 | 3.10 × 10−3 |

| k = 30 | 1.06 × 10−6 | 9.88 × 10−6 | 3.24 × 10−3 |

| k = 50 | 2.06 × 10−6 | 1.11 × 10−5 | 3.46 × 10−3 |

Acknowledgments

Giacomo Aletti is a member of the Italian Group “Gruppo Nazionale per il Calcolo Scientifico” of the Italian Institute “Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica” and Irene Crimaldi is a member of the Italian Group “Gruppo Nazionale per l’Analisi Matematica, la Probabilità e le loro Applicazioni” of the Italian Institute “Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica”. The authors acknowledge Fabio Del Vigna, Marinella Petrocchi and Manuel Pratelli for the bot detection on the above mentioned data sets.

Data Availability

Data can be downloaded from the website of the TOFFEe project at https://toffee.imtlucca.it/datasets.

Funding Statement

Irene Crimaldi and Fabio Saracco are supported by the Italian “Programma di Attività Integrata” (PAI), project “TOol for Fighting FakEs” (TOFFE) funded by IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca. Fabio Saracco acknowledges also support from the European Project SoBigData++ GA. 871042.

References

- 1.Publication Office of the European Union. Media use in the European Union; 2018.

- 2. Mitchell A, Page D. The evolving role of news of Twitter and Facebook. Pew Research Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zollo F, Novak PK, Del Vicario M, Bessi A, Mozetič I, Scala A, et al. Emotional dynamics in the age of misinformation. PLoS One. 2015;10(9). 10.1371/journal.pone.0138740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Del Vicario M, Vivaldo G, Bessi A, Zollo F, Scala A, Caldarelli G, et al. Echo Chambers: Emotional Contagion and Group Polarization on Facebook. Sci Rep. 2016c;. 10.1038/srep37825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Del Vicario M, Vivaldo G, Bessi A, Zollo F, Scala A, Caldarelli G, et al. Echo Chambers: Emotional Contagion and Group Polarization on Facebook. Sci Rep. 2016d;. 10.1038/srep37825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zollo F, Sluban B, Mozetič I, Quattrociocchi W. Toward a better understanding of emotional dynamics on Facebook. In: Stud. Comput. Intell.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradshaw S, Howard P. The Global Organization of Social Media Disinformation Campaigns. Journal of International Affairs. 2017;71(1.5). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradshaw S, Howard P. The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda; 2019.

- 9.National Endowment for Democracy. Issue brief: Distinguishing Disinformation from Propaganda, Misinformation, and “Fake News”; 2019. Available from: https://www.ned.org/issue-brief-distinguishing-disinformation-from-propaganda-misinformation-and-fake-news/.

- 10. Cresci S, Di Pietro R, Petrocchi M, Spognardi A, Tesconi M. Fame for sale: Efficient detection of fake Twitter followers. Decis Support Syst. 2015;. 10.1016/j.dss.2015.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrara E, Varol O, Davis C, Menczer F, Flammini A. The Rise of Social Bots. Commun ACM. 2016;59(7):96–104. 10.1145/2818717 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shao C, Ciampaglia GL, Varol O, Yang KC, Flammini A, Menczer F. The spread of low-credibility content by social bots. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4787. 10.1038/s41467-018-06930-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stella M, Ferrara E, Domenico MD. Bots sustain and inflate striking opposition in online social systems. PNAS. 2018;115(49):12535–12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang KC, Varol O, Davis CA, Ferrara E, Flammini A, Menczer F. Arming the public with artificial intelligence to counter social bots. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2019;. 10.1002/hbe2.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cresci S, Spognardi A, Petrocchi M, Tesconi M, Pietro RD. The paradigm-shift of social spambots: Evidence, theories, and tools for the arms race. In: 26th Int. World Wide Web Conf. 2017, WWW 2017 Companion; 2019.

- 16. Caldarelli G, De Nicola R, Del Vigna F, Petrocchi M, Saracco F. The role of bot squads in the political propaganda on Twitter. Commun Phys. 2020;3(1):1–15. 10.1038/s42005-020-0340-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Flaxman S, Goel S, Rao JM. Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2016;80(S1):298–320. 10.1093/poq/nfw006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Becatti C, Caldarelli G, Lambiotte R, Saracco F. Extracting significant signal of news consumption from social networks: the case of Twitter in Italian political elections. Palgrave Commun. 2019;. 10.1057/s41599-019-0300-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pacheco D, Hui PM, Torres-Lugo C, Truong BT, Flammini A, Menczer F. Uncovering Coordinated Networks on Social Media; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caldarelli G, de Nicola R, Petrocchi M, Pratelli M, Saracco F. Analysis of online misinformation during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemics in Italy; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qiu X, Oliveira DFM, Sahami Shirazi A, Flammini A, Menczer F. Limited individual attention and online virality of low-quality information. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1(7). 10.1038/s41562-017-0132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jansen BJ, Zhang M, Sobel K, Chowdury A. Twitter Power: Tweets as Electronic Word of Mouth. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2009;60(11):2169–2188. 10.1002/asi.21149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AGCOM. Report on the consumption of information. Autorità per le Garanzie delle Comunicazioni; 2018. February.

- 24. Ren F, Wu Y. Predicting User-Topic Opinions in Twitter with Social and Topical Context. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing. 2013;4(4):412–424. 10.1109/T-AFFC.2013.22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chakraborty K, Bhattacharyya S, Bag R. A Survey of Sentiment Analysis from Social Media Data. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems. 2020;7(2):450–464. 10.1109/TCSS.2019.2956957 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil HP, Atique M. Sentiment Analysis for Social Media: A Survey. In: 2015 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Security (ICISS); 2015. p. 1–4.

- 27. Yue L, Chen W, Li X, Zuo W, Yin M. A survey of sentiment analysis in social media. Knowl Inf Syst. 2019;60:617–663. 10.1007/s10115-018-1236-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bing L, Chan KCC, Ou C. Public Sentiment Analysis in Twitter Data for Prediction of a Company’s Stock Price Movements. In: 2014 IEEE 11th International Conference on e-Business Engineering; 2014. p. 232–239.

- 29. Bollen J, Mao H, Zeng X. Twitter mood predicts the stock market. Journal of Computational Science. 2011;2(1):1—8. 10.1016/j.jocs.2010.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Golder SA, Macy MW. Diurnal and Seasonal Mood Vary with Work, Sleep, and Daylength Across Diverse Cultures. Science. 2011;333(6051):1878–1881. 10.1126/science.1202775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lei X, Qian X, Zhao G. Rating Prediction Based on Social Sentiment From Textual Reviews. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia. 2016;18:1910–1921. 10.1109/TMM.2016.2575738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor B, Balasubramanyan R, Routledge B, Smith N. From Tweets to Polls: Linking Text Sentiment to Public Opinion Time Series. In: International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. vol. 11; 2010.

- 33. Tumasjan A, Sprenger T, Sandner P, Welpe I. Predicting Elections with Twitter: What 140 Characters Reveal about Political Sentiment. In: Word. Journal Of The International Linguistic Association. vol. 10; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu X, Liu Y, Huang X, An A. Mining Online Reviews for Predicting Sales Performance: A Case Study in the Movie Domain. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 2012;24(4):720–734. 10.1109/TKDE.2010.269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhu J, Wang H, Zhu M, Tsou B, Ma M. Aspect-Based Opinion Polling from Customer Reviews. Affective Computing, IEEE Transactions on. 2011;2(1):37—49. 10.1109/T-AFFC.2011.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chmiel A, Sienkiewicz J, Thelwall M, Paltoglou G, Buckley K, Kappas A, et al. Collective Emotions Online and Their Influence on Community Life. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(7):1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bollen J, Pepe A, Mao H. Modeling public mood and emotion: Twitter sentiment and socio-economic phenomena. Computing Research Repository—CORR. 2009;. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tan S, Li Y, Sun H, Guan Z, Yan X, Bu J, et al. Interpreting the Public Sentiment Variations on Twitter. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 2014;26(5):1158–1170. 10.1109/TKDE.2013.116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kursuncu U, Gaur M, Lokala U, Thirunarayan K, Sheth A, Arpinar IB. Predictive Analysis on Twitter: Techniques and Applications. ArXiv. 2018;abs/1806.02377. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chadwick A. The hybrid media system: Politics and power, second edition. New York: [etc.]: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zaman T, Fox EB, Bradlow ET. A bayesian approach for predicting the popularity of tweets. Ann Appl Stat. 2014;. 10.1214/14-AOAS741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dow PA, Adamic LA, Friggeri A. The anatomy of large facebook cascades. In: Proc. 7th Int. Conf. Weblogs Soc. Media, ICWSM 2013; 2013.

- 43.Kumar R, Mahdian M, McGlohon M. Dynamics of conversations. In: Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min.; 2010.

- 44.Kobayashi R, Lambiotte R. TiDeH: Time-dependent Hawkes process for predicting retweet dynamics. In: Proc. 10th Int. Conf. Web Soc. Media, ICWSM 2016; 2016.

- 45.Gao S, Ma J, Chen Z. Modeling and predicting retweeting dynamics on microblogging platforms. In: WSDM 2015—Proc. 8th ACM Int. Conf. Web Search Data Min.; 2015.

- 46. Golosovsky M, Solomon S. Stochastic dynamical model of a growing citation network based on a self-exciting point process. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.098701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Q, Erdogdu MA, He HY, Rajaraman A, Leskovec J. SEISMIC: A self-exciting point process model for predicting tweet popularity. In: Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min.; 2015.

- 48.Aletti G, Crimaldi I. The Rescaled Pólya Urn: local reinforcement and chi-squared goodness of fit test. arXiv:190610951. 2019;.

- 49. Eggenberger F, Pólya G. Über die Statistik verketteter Vorgänge. ZAMM—Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics / Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik. 1923;3(4):279–289. 10.1002/zamm.19230030407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mahmoud HM. Pólya urn models. Texts in Statistical Science Series. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pemantle R. A survey of random processes with reinforcement. Probab Surveys. 2007;4:1–79. 10.1214/07-PS094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tang J, Zhang Y, Sun J, Rao J, Yu W, Chen Y, et al. Quantitative Study of Individual Emotional States in Social Networks. Affective Computing, IEEE Transactions on. 2012;3. 10.1109/T-AFFC.2011.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aletti G, Crimaldi I. Generalized Rescaled Pólya urn and its statistical applications. arXiv:201006373. 2020;.

- 54. Aletti G, Crimaldi I, Ghiglietti A. Synchronization of reinforced stochastic processes with a network-based interaction. Ann Appl Probab. 2017;27(6):3787–3844. 10.1214/17-AAP1296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Aletti G, Crimaldi I, Ghiglietti A. Interacting Reinforced Stochastic Processes: Statistical Inference based on the Weighted Empirical Means. Bernoulli. 2020;26(2):1098–1138. 10.3150/19-BEJ1143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aletti G, Ghiglietti A, Rosenberger WF. Nonparametric covariate-adjusted response-adaptive design based on a functional urn model. Ann Statist. 2018;46(6B):3838–3866. 10.1214/17-AOS1677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Aletti G, Ghiglietti A, Vidyashankar AN. Dynamics of an adaptive randomly reinforced urn. Bernoulli. 2018;24(3):2204–2255. 10.3150/17-BEJ926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Berti P, Crimaldi I, Pratelli L, Rigo P. Asymptotics for randomly reinforced urns with random barriers. J Appl Probab. 2016;53(4):1206–1220. 10.1017/jpr.2016.75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Caldarelli G, Chessa A, Crimaldi I, Pammolli F. Weighted networks as randomly reinforced urn processes. Phys Rev E. 2013;87:020106. 10.1103/PhysRevE.87.020106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chen MR, Kuba M. On generalized Pólya urn models. J Appl Probab. 2013;50(4):1169–1186. 10.1239/jap/1389370106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Collevecchio A, Cotar C, LiCalzi M. On a preferential attachment and generalized Pólya’s urn model. Ann Appl Probab. 2013;23(3):1219–1253. 10.1214/12-AAP869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Crimaldi I. Central limit theorems for a hypergeometric randomly reinforced urn. J Appl Probab. 2016;53(3):899–913. 10.1017/jpr.2016.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ghiglietti A, Vidyashankar AN, Rosenberger WF. Central limit theorem for an adaptive randomly reinforced urn model. Ann Appl Probab. 2017;27(5):2956–3003. 10.1214/16-AAP1274 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Laruelle S, Pagés G. Randomized urn models revisited using stochastic approximation. Ann Appl Proba. 2013;23(4):1409–1436. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lasmar N, Mailler C, Selmi O. Multiple drawing multi-colour urns by stochastic approximation. J Appl Probab. 2018;55(1):254–281. 10.1017/jpr.2018.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Y, Skiena S. Building sentiment lexicons for all major languages. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Short Papers); 2014. p. 383–389.

- 67. Wood SN. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, Second Ed. Chapman and Hall, CRC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be downloaded from the website of the TOFFEe project at https://toffee.imtlucca.it/datasets.