Abstract

Neonectria faginata and Neonectria coccinea are the causal agents of the insect-fungus disease complex known as beech bark disease (BBD), known to cause mortality in beech forest stands in North America and Europe. These fungal species have been the focus of extensive ecological and disease management studies, yet less progress has been made toward generating genomic resources for both micro- and macro-evolutionary studies. Here, we report a 42.1 and 42.7 mb highly contiguous genome assemblies of N. faginata and N. coccinea, respectively, obtained using Illumina technology. These species share similar gene number counts (12,941 and 12,991) and percentages of predicted genes with assigned functional categories (64 and 65%). Approximately 32% of the predicted proteomes of both species are homologous to proteins involved in pathogenicity, yet N. coccinea shows a higher number of predicted mitogen-activated protein kinase genes, virulence determinants possibly contributing to differences in disease severity between N. faginata and N. coccinea. A wide range of genes encoding for carbohydrate-active enzymes capable of degradation of complex plant polysaccharides and a small number of predicted secretory effector proteins, secondary metabolite biosynthesis clusters and cytochrome oxidase P450 genes were also found. This arsenal of enzymes and effectors correlates with, and reflects, the hemibiotrophic lifestyle of these two fungal pathogens. Phylogenomic analysis and timetree estimations indicated that the N. faginata and N. coccinea species divergence may have occurred at ∼4.1 million years ago. Differences were also observed in the annotated mitochondrial genomes as they were found to be 81.7 kb (N. faginata) and 43.2 kb (N. coccinea) in size. The mitochondrial DNA expansion observed in N. faginata is attributed to the invasion of introns into diverse intra- and intergenic locations. These first draft genomes of N. faginata and N. coccinea serve as valuable tools to increase our understanding of basic genetics, evolutionary mechanisms and molecular physiology of these two nectriaceous plant pathogenic species.

Keywords: canker, Nectriaceae, Fagus grandifolia, Fagus sylvatica, forest pathology

Introduction

The American beech tree (Fagus grandifolia Herh.) is one of the centerpiece species in Eastern North American deciduous forests from Nova Scotia west to the Great Lakes and south to the Gulf Coast, ranging from higher elevations in the Appalachian Mountains to sea level in coastal regions (Kitamura and Kawano 2001; Cogbill 2005). European or common beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) is one of the most competitive tree species in Western, Central, and Southern Europe due to its growth capacity and adaptability (Jung 2009). Beech trees in Europe and North America are traditionally considered as low risk in terms of susceptibility to pathogens and pests. However, in the past 140 years, beech bark disease (BBD) has caused extensive above-ground mortality and decline, impacting not only the overall survival of these tree species but also the general forest ecosystem integrity (Cale et al. 2017).

BBD is an insect-fungus complex that involves the beech scale insect (Cryptococcus fagisuga Lind.) and the fungi Neonectria faginata and Neonectria coccinea (Houston 1994; Castlebury et al. 2006). The species Neonectria ditissima is often found in scale-infested beech trees; however, its interaction in the BBD complex depends on many factors, including infection timing (Cale et al. 2017). Ultimate mortality of the beech trees is generally attributed to N. faginata or N. coccinea (Houston 1994; Castlebury et al. 2006; Cale et al. 2017). The BBD complex has been known in European beech since the mid-1800s and it is now widely distributed across Western and Central Europe including Great Britain, France, Germany, Romania and Hungary (Houston et al. 1979; Houston 1994; Cale et al. 2017). In North America, it is believed that in the late 1800s plant material that included ornamental European beech infested with the beech scale insect made its way into public gardens of the port city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Canada (Houston 1994). However, it was not until approximately 1911 that the presence of the scale insect was detected and by late 1920s scale infestations were discovered in the United States near Boston (Houston 1994). From there, the scale insect and the disease spread further toward beech stands in the Northeast and Central US (Houston 1994). Currently in the United States, BBD has been reported in roughly one-third of the geographical range of the American beech (Morin et al. 2007). It is predicted that BBD will spread across the entire range of American beech in the United States in the next 40–50 years (Morin et al. 2007; Cale et al. 2017).

The most important fungal species associated with BBD are N. faginata and N. coccinea, all belonging to the family Nectriaceae (Hypocreales, Ascomycota). N. coccinea (=Cylindrocarpon candidum) was originally described as Sphaeria coccinea occurring on bark of Fagus sp. in Germany (Persoon 1800; Rossman et al. 1999). Although first described as widely distributed, recent studies found N. coccinea sensu stricto is currently restricted to Europe (France, Germany, Romania, Scotland, and Slovakia) associated with Fagus species such as F. crenata and F. sylvatica (Castlebury et al. 2006; Hirooka et al. 2013). N. faginata (=Cylindrocarpon faginatum) was first described as a variety of N. coccinea (N. coccinea var. faginata) but was later elevated to the species rank (Castlebury et al. 2006). N. faginata is known to occur only in North America on F. grandifolia and F. sylvatica (Castlebury et al. 2006; Farr and Rossman 2020). N. ditissima (=N. galligena) has also been found associated with the disease complex in both Europe and North America but is mostly known as pathogen of other hardwood tree species in the genera Acer, Betula, and Quercus and fruit trees in the genera Malus and Pyrus (Castlebury et al. 2006; Hirooka et al. 2013; Farr and Rossman 2020). It was initially believed that N. faginata (as N. coccinea var. faginata) was accidentally introduced to North America, most likely at the same time than the beech scale (Houston 1994). Initial studies on the genetic diversity of N. faginata and N. coccinea supported this hypothesis as the genetic variability was lower in N. faginata compared to that of N. coccinea, indicating a possible founder effect (Mahoney et al. 1999; Plante et al. 2002). Recent phylogenetic analyses have demonstrated that N. faginata and N. coccinea are closely related but distinct species, native to their respective geographic ranges. Additionally, these species are heterothallic based on the characterization of their mating type (MAT) locus (Stauder et al. 2020). This could indicate that other as yet unknown genetic factors might explain the low levels of intraspecific diversity within these species (Castlebury et al. 2006; Hirooka et al. 2013).

Despite extensive ecological and pest management research on the BBD complex, reference genomes for the fungal species involved in this tree disease are still lacking. In this study, we generated, assembled de novo draft genomes of the major BBD fungal pathogens N. faginata and N. coccinea, and performed comparative genomic analyses between these species and among other genomes of plant pathogens in the Nectriaceae. Taken together and given the lack of genomic resources for these important plant pathogens, the genomes reported here, and the insights gained by the genomic analyses of CAZyme composition, virulence determinants, and mitogenomes provide valuable basic information aimed at understanding the biology of BBD pathogens and their emergence, host preference, and geographic distribution.

Materials and methods

Fungal material, DNA extraction, and genome sequencing

Details about the fungal isolates used in this study are included in Table 1. N. faginata isolate CBS 134246, N. coccinea isolate CBS 119158, N. ditissima isolate CBS 226.31, and Corinectria fuckeliana isolate CBS 125109 were grown as described by Skaltsas and Salgado-Salazar (2020). Genomic DNA was extracted from harvested mycelial mats of each fungal isolate using the OmniPrep DNA kit (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO, USA). Genomic DNA libraries were constructed using the TruSeq® DNA Nano kit and quantified using the KAPA Biosystems Illumina Library Quantification Kit (KAPABIOSYSTEMS, Wilmington, MA, USA). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq as 2 × 300 paired-end reads using a MiSeq version 3.0, 600 cycle reagent kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Table 1.

Fungal isolates used for the de novo genome sequencing in this study

| Species | Isolate | Herbarium number | Substrate/host | Country | Collection year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonectria coccinea | G.J.S. 98-114/CBS 119158a | BPI 748295 | Fagus sylvatica | Germany | 1998 |

| Neonectria faginata | A.R. 4307/CBS 134246b | BPI 878329 | Fagus grandifolia | USA: Maine | 2002 |

| Neonectria ditissima | CBS 226.31c/IMI 113922 | — | Fagus sylvatica | Germany | 1925 |

| Corinectria fuckeliana | G.J.S. 02-67/CBS 125109 | BPI 842434 | Pinus radiata | New Zealand | 2002 |

Ex-epitype culture of N. coccinea.

Ex-epitype culture of N. faginata.

Authentic strain of Cylindrocarpon heteronema (=Neonectria ditissima asexual state).

Assembly, annotation, and bioinformatic analyses

The obtained sequencing reads were trimmed for quality and adapter removal and assembled with kmer = 50 and bubble = 36 using the CLC Genomics Workbench version 12 (CLC Bio, Boston, MA, USA). Ab initio gene predictions for the draft genome assemblies of N. faginata and N. coccinea and related species were performed using the AUGUSTUS web server (http://bioinf.uni-greifswald.de/webaugustus/; Hoff and Stanke 2013) using Fusarium graminearum gene models as training sets. The quantitative assessment of the genome assembly completeness was evaluated using BUSCO v.3.0 (Simão et al. 2015) run in the Cyverse Discovery environment (Goff et al. 2011), using eukaryotes (eukariota_odb9) and fungi (fungi_odb9) lineages. The predicted proteome of each fungus was functionally annotated by assigning Gene Ontology (GO) terms using BLAST2GO v.1.12.13 (Conesa et al. 2005).

Phylogenomic analyses and evolutionary divergence time estimation

To reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among N. coccinea and N. faginata, orthologous gene families were identified from predicted proteome sequences using OrthoFinder v2.2.6 (Emms and Kelly, 2015) under default settings (BLASTP e-value cut-off = 1e−5; MCL inflation I = 1.5). Seventeen additional predicted proteomes of sordariomycete species were included in the analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Orthologous single copy gene alignments found in each predicted proteome dataset were retrieved from OrthoFinder v2.2.6 results and concatenated using CLC Genomics Workbench version 12 (CLC Bio, Boston, MA, USA). After concatenation, poorly aligned positions were removed with Gblocks v0.91 using relaxed selection parameters (Talavera and Castresana 2007). Maximum likelihood (ML, proteins) phylogenetic analyses were performed in RAxML (Stamatakis 2014), using the RAxML GUI v.2.0.0-beta1 (Silvestro and Michalak 2012). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the best fitting model obtained using MEGAX [general matrix (LG)+G + I+F; Kumar et al. 2018] and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum was used as outgroup to root the phylogenetic trees. Approximate information on the divergence event for N. faginata and N. coccinea was obtained using the RelTime method (Tamura et al. 2012, 2018) as implemented in MEGAX (Kumar et al. 2018). RelTime estimated the relative divergence times for each node of the ML tree using the same outgroup taxa. We used three confidence intervals obtained from the TimeTree database (http://timetree.org; Hedges et al. 2015) as minimum and maximum times to convert the relative times into absolute times as follows: divergence F. graminearum and M. oryzae = 314–414 million years ago (Mya), divergence F. graminearum and T. reesei = 179–294 Mya, and divergence F. graminearum and V. dahliae = 192–294 Mya. Time estimates were performed using maximum-likelihood branch length, local clocks, amino acid substitution model as for ML analyses, and a discrete Gamma distribution among sites (five categories), as implemented in MEGAX (Kumar et al. 2018).

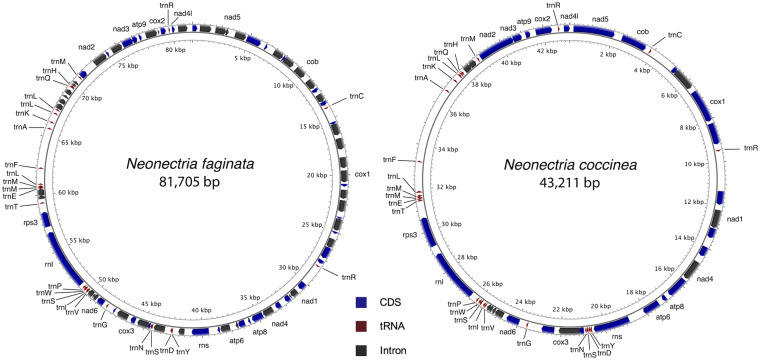

Mitochondrial genome

The mitochondrial genomes of N. faginata, N. coccinea, N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi (Skaltsas and Salgado-Salazar 2020) were identified by performing BLAST searches on each complete genome assembly using the 34.4 kb complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of Fusarium oxysporum as a BLAST query (Pantou et al. 2008). The resulting mitochondrial sequences were then annotated using MITOS Web Server (http://mitos2.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/, Bernt et al. 2013) with the genetic code set to four (mold). Mitochondrial genome sequence visualization, using the annotation provided by MITOS, was performed using the CGView server (http://stothard.afns.ualberta.ca/cgview_server/, Grant and Stothard 2008).

Orthologous gene clusters, cytochrome P450 proteins, and virulence associated genes

Genome-wide identification and visualization of orthologous gene clusters present among the predicted proteomes of N. faginata, N. coccinea, as well as these species with N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi were performed using OrthoVenn2 (https://orthovenn2.bioinfotoolkits.net/home, Li et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2019). Default OrthoVenn2 settings were used for e-value (1e−5) and inflation (1.5) values (Wang et al. 2015). Candidate virulence, pathogenicity and effector-associated genes were identified by performing BLASTP searches (e-value threshold 1.0e−10) of the predicted proteomes of each species against the pathogen-host interaction database (PHI-base v 4.8, http://phi-blast.phi-base.org). Potential cytochrome P450 (CYPs) genes were identified first through BLASTP searches and annotated using GO ontology terms with BLAST2GO v.1.12.13. The subset of genes with GO categories related to P450 enzyme activities or gene expression were subsequently blasted (BLASTP, e-value cut-off 1e−10, matrix BLOSUM62) against the Fungal Cytochrome P450 Database (FCPD, http://p450.riceblast.snu.ac.kr/blast.php) (Moktali et al. 2012). CYPs family and subfamily assignment was based on Nelson’s nomenclature (Nelson 2009).

Secreted proteins and secondary metabolite clusters

To identify secreted proteins from the predicted proteome of each fungi, the web analysis tool SECRETOOL (http://genomics.cicbiogune.es/SECRETOOL/Secretool.php, Cortázar et al. 2014) was used. The classical secretion analysis pipeline includes processing the data with TargetP, SignalP, and PredGPI and lastly WoLFPSORT (Cortázar et al. 2014). Putative secreted effector proteins were identified from the secreted proteins pool using EffectorP v. 2.0 (http://effectorp.csiro.au; Sperschneider et al. 2018). Identification of putative enzymes associated with the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites was performed using the online tool antiSMASH v. 5.0 fungal version (https://fungismash.secondarymetabolites.org/, Blin et al. 2019) with detection strictness relaxed.

CAZyme annotation

Predicted proteins with the family-specific HMM profile of CAZymes were annotated by searching the predicted proteome against the database for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme Annotation (dbCAN, http://bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/blast.php; Yin et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2018). Three tools were used in the search using default settings, including HMMER scan against the dbCAN HMM database, Diamond (Buchfink et al. 2015) search against the carbohydrate-active enZYmes (CAZy) (Lombard et al. 2014), and Hotpep against the Peptide Pattern Recognition library (Busk et al. 2017). For comparative purposes, previously published genome data of other closely related fungi in the Nectriaceae were also included for comparative purposes (Supplementary Table S1). These fungi are representatives of four plant-associated lifestyles (facultative parasitic, hemibiotrophic, necrotrophic and saprophytic). Independent samples t tests and X2 test of independence (Martinez et al. 2004) were run to detect statistical differences between CAZymes repertoires and were performed in SPSS statistics v. 26 (https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software).

Data availability

This Whole Genome Shotgun project, including sequencing reads, has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under BioProject PRJNA593731, accession numbers WPDD00000000 (N. faginata CBS 134246), WPDF00000000 (N. coccinea CBS 119158), WPDG00000000 (N. ditissima CBS 226.31), WPDH00000000 (C. fuckeliana CBS 125109). Supplementary material is available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25387/g3.14050034.

Results and discussion

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Summary statistics of the draft genome assemblies are included in Table 2. The genome sizes of N. faginata and N. coccinea (42.1–42.7 Mb) are within the size range observed for other plant pathogens in the Nectriaceae (25–65 Mb), including the additional species sequenced in this study (Table 2). Additionally, the de novo genome sequence assembly of N. ditissima, reported in this study, is in agreement with draft genome sequences previously published (Deng et al. 2015; Gómez-Cortecero et al. 2015); however, this is the first draft genome of a N. ditissima isolate collected on beech (F. sylvatica). N. ditissima is also an important canker pathogen of apples and pears (European canker) worldwide, and previously the genetic variability of this pathogen has only been studied on N. ditissima isolates associated with apple canker (Ghasemkhani et al. 2016; Gómez-Cortecero et al. 2016).

Table 2.

Genome assembly statistics Neonectria coccinea, Neonectria faginata, and related species used in this study

| Species | Neonectria faginata | Neonectria coccinea | Neonectria ditissima | Corinectria fuckeliana |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length (Mb) | 42.1 | 42.7 | 43.5 | 42.2 |

| No. paired-end sequence reads (Mb) | 9.9 | 40.4 | 16.7 | 31.5 |

| No. scaffolds | 522 | 571 | 1,274 | 737 |

| Max. scaffold length (kb)a | 709.7 | 532.9 | 515.4 | 822.7 |

| Avg. scaffold size (kb) | 80.6 | 74.7 | 34.1 | 57.2 |

| Average coverage | 58.4 | 127.3 | 89.2 | 185.6 |

| N50 (kb)b | 237.1 | 178.8 | 113.9 | 255.6 |

| GC content (%) | 52.6 | 51.6 | 52.2 | 50 |

| Eukaryote orthologsc | 96.8% | 96% | 95.4% | 96.5 |

| Fungal orthologsd | 94.1% | 99% | 98.4% | 99.3% |

| Predicted gene models | 12,991 | 12,941 | 13,669 | 11,446 |

Minimum scaffold length 500 bp.

N50 = scaffold/contig length at which 50% of the total assembly length is covered.

Percentage of complete BUSCOs found, 429 total BUSCO groups searched.

Percentage of complete BUSCOs found, 1,438 total BUSCO groups searched.

In total, 12,991 and 12,491 protein-coding genes were predicted from the genome assemblies of N. faginata and N. coccinea, respectively (Table 2). Approximately 45.7 and 45.1% of the genomes of N. faginata and N. coccinea, respectively, are estimated to be coding sequences. Gene predictions for N. ditissima and C. fuckeliana identified 13,669 and 11,446 protein-coding genes, respectively. The coding sequences of N. ditissima genome accounted for 47.3% of its total length, the highest percentage when compared with N. faginata, N. coccinea, and C. fuckeliana, whose predicted proteome accounts for only 41% to the total genome length. It has been found that some specialized fungal pathogens in the Nectriaceae have reduced proteomes (losing redundant and only maintaining essential genes) (De Man et al. 2016; Rivera et al. 2018). Even though N. faginata and N. coccinea have a very narrow host range, being found only in association with two beech species, F. grandifolia and F. sylvatica (Farr and Rossman 2020), they do not follow this pattern and display a predicted proteome size equivalent to that of pathogens with broader host ranges. This predicted proteome expansion may play a role in adaptation of these pathogens to the BBD complex environment, where other fungi (i.e., N. ditissima) and insects (beech scale) also contribute to the pathogen–host relationships. The currently unknown stages of the lifecycle in the absence of suitable host (probably saprophytic) of the BBD pathogens, may also contribute to the maintenance of proteome size and profile. Functional annotation of the predicted proteome of N. faginata and N. coccinea revealed that only 3% of the predicted proteome had no homology to known proteins in the GenBank Protein dataset.

N. faginata predicted proteins showed an average length of 496 aa, 12,589 (97%) had BLASTP hits, with GO ontology terms assigned to 8335 (64%) of the total predicted proteome. N. coccinea predicted proteins showed an average length of 502 aa. Of the total predicted proteins, 12,144 got BLASTP hits (97%), with GO ontology terms assigned to 8284 (65%) of the total predicted proteome. N. ditissima predicted proteins showed an average of 503 aa. Of the total predicted proteins, 13,322 got BLASTP hits (97%) and GO ontology terms could be assigned to 8980 proteins (66%). The predicted proteins of C. fuckeliana and T. rubi showed an average length of 505 and 511 aa, respectively. Sequences with BLASTP hits constituted 95–97% of total predicted proteome in these species as well. GO ontology terms were assigned to only 56% of the T. rubi predicted proteome, compared to 65% of the predicted proteome for C. fuckeliana. The assigned GO domains for the predicted proteome of N. faginata and N. coccinea were almost identical (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S2). Among the GO domains assigned both species’ predicted proteomes, the major biological process groups included metabolic (37%), cellular processes (28%), and localization (11%). Molecular function main GO domains were assigned to catalytic activity (46%) and binding (37%), and cellular component GO domains were centered in cellular anatomical entities (60%) and intracellular (27%) (Supplementary Table S2). The assigned GO domains for N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi followed the same general trend as N. faginata and N. coccinea (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Blast2GO gene ontology categories from the predicted proteins of BBD fungal pathogens and other species used as comparison in this study.

Phylogenetic analyses and divergence estimates

Analyses using the program OrthoFinder v2.2.6 showed that there are 14,862 orthogroups among the 21 predicted proteomes of the fungal species used. A total of 852 single copy orthologous shared across all species were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships. After removal of ambiguously aligned regions and gaps using GBlocks, a total of 259,058 bp (36% of total) remained, with 111,490, 147,568, and 93,834 sites determined as conserved, variable and phylogenetically informative, respectively. The inferred phylogeny and time calibrated tree are displayed in Figure 2. N. faginata and N. coccinea appear as closely related sister species whose time of divergence was estimated at ∼4.11 Mya. Within the Neonectria species used in this analysis, N. ditissima is observed as having the earliest diversification split, estimated at ∼ 20.62 Mya. Corinectria fuckeliana (split ∼ 37.91 Mya) might be hypothesized as the diversification point for the genus Neonectria as well. Thelonectria rubi (split 85.55 Mya) was identified as basal lineage to N. faginata, N. coccinea, N. ditissima, and C. fuckeliana (Figure 2). All branches in the phylogenetic tree were supported by ML bootstrap values of 99–100% and the tree topology obtained using orthologous genes is in concordance with previous phylogenetic studies (Castlebury et al. 2006; Chaverri et al. 2011; Salgado-Salazar et al. 2015), also supporting findings about the probable native origin of N. faginata in North America (Castlebury et al. 2006; Hirooka et al. 2013).

Figure 2.

Phylogenomic relationships between the BBD fungal pathogens N. faginata and N. coccinea and 19 other fungi in the Sordariomycetes and reconstruction of divergence times of N. faginata and N. coccinea relative to other fungal species. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree and divergence time estimations were based on the analysis of 852 concatenated single copy orthologous genes present in all the species. Values on the nodes indicate the approximate relative times of divergence (Mya) between two lineages. Bootstrap values are listed above branches. The Leotiomycete fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum was used as outgroup.

Mitochondrial genomes

Local BLAST searches indicated the entire mitochondrial genome sequence was contained within a single contig for all the genomes studied (N. faginata Contig 10, N. coccinea Contig 1, N. ditissima Contig 33, C. fuckeliana Contig 86, and T. rubi Contig 17). The mitochondrial genome sizes of N. faginata and N. coccinea were 81.7 and 43.2 kb (Figure 3). The N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi mitochondrial genomes measured 53.1, 47.8, and 37.4 kb, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). The difference in the sizes of the mtDNA genomes of N. faginata and N. coccinea is somewhat unexpected as these species are closely related sister taxa; however, this diversity in the mtDNA genomes sizes seems to be a common phenomenon in many species in the Nectriaceae (Al-Reedy et al. 2012). The overall A + T content ranged from 69.3 to 70.90%. The mitochondrial genomes of all the species studied included genes for the 14 proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation and production of ATP (NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1–6, 4L, ATP synthase subunits 6, 8, 9, cytochrome oxidase subunits 1–3, apocytochrome b), two ribosomal RNA subunits (rns, rnl) and the intron coding ribosomal protein Rps3. A total of 26 transfer RNAs (tRNA) were found on N. faginata, C. fuckeliana and T. rubi, and 25 tRNA were found in N. coccinea and N. ditissima. Based on additional tBLASTx searches, all species contained similar copies of the largest unidentified open-reading frame (ORF) found encoded by the mitochondrial genomes of other nectriaceous fungi such as F. graminearum (ORF1930), F. oxysporum (ORF2013), and F. verticilloides (ORF2572) (Al-Reedy et al. 2012), in Glomus species (Beaudet et al. 2013) and Aspergillus and Penicillium species (Joardar et al. 2012), among others. This ORF is located downstream of the rnl and nad2 region (Figure 3). The order of the coding gene regions and tRNAs in all species was identical, except in the position of the tRNAs trnA and trnF (order: F–A for N. faginata, N. coccinea, and N. ditissima and A–F for C. fuckeliana and T. rubi). The size differences observed between the mitochondrial genomes of N. faginata and N. coccinea are largely due to the presence of a higher number of group I introns in N. faginata when compared with N. coccinea (4:1 ratio) (Figure 3). The number of group I introns detected varied widely and showed no general pattern of conservation among all the species studied, with the highest number present in N. faginata, followed by N. coccinea, N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and lastly T. rubi (Figure 3 or Supplementary Figure S1). All group I introns belong to the LAGLIDADG and GIY-YIG family classes of homing endonuclease genes. To a lesser extent, mtDNA genome size differences can also be attributed to variations in the size of the unidentified ORF. This suggests that, while some introns might have been inherited by vertical transmission from a common ancestor (e.g., intron located within nad1 gene, present in common ancestor to C. fuckeliana, N. ditissima, N. coccinea, and N. faginata, but not present in T. rubi), the vast majority of the remaining introns may have been gained or lost following species divergence (Al-Reedy et al. 2012). While the origin of unidentified ORFs is still unclear, the most likely mechanism involved in their introduction in the mtDNA is horizontal gene transfer, either between closely related species or between species that share the same ecological niche (Beaudet et al. 2013; Torriani et al. 2014). Further studies are necessary to understand the evolution of mtDNAs in these fungi and the role short-read sequencing errors might have in the presence of an increased number of introns in N. faginata.

Figure 3.

Genetic organization of Neonectria faginata and N. coccinea mitochondrial DNA.

Orthologous gene clusters

Predicted proteins of N. faginata and N. coccinea formed 11,068 clusters of which 10,944 were shared among these two species (Figure 4A). When comparing N. faginata and N. coccinea, 48 orthologous clusters were found exclusively in N. faginata (Figure 4A), with protein copy numbers that varied from 2 to 14. Of these unique clusters, 22 were assigned to biological processes based on GO terms related to metabolic processes (19), DNA repair and integration (2) and cellular protein modification processes (1). N. coccinea showed 26 exclusive orthologous clusters (Figure 4A), with protein counts going from 2 to 3. Of these unique clusters, 13 were assigned to biological (6), metabolic processes (5). One GO biological process category related to pathogenesis (GO: 0009405) was found enriched in N. coccinea unique clusters (hypergeometric test, P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Orthologous gene clusters shared between (A) Neonectria faginata and N. coccinea; (B) N. faginata, N. coccinea, and N. ditissima; and (C) all the species included in this study.

N. faginata, N. coccinea, and N. ditissima predicted proteins formed 11,983 orthologous clusters, of which 9819 are clusters shared among the three species (Figure 4B). When the orthologous comparison among these three species is made, N. faginata, N. coccinea, and N. ditissima showed 29, 13, and 70 unique clusters, respectively. Among the N. ditissima unique clusters, two biological process clusters related to DNA-mediated transportation (GO: 0006313) were found enriched (hypergeometric test, P < 0.0001). One cluster shared between N. coccinea and N. ditissima related to gibberellin biosynthetic process (GO: 0009686, P < 0.0001) was found enriched. Proteins from the five fungal species included in this study formed a total of 12,908 orthologous clusters (Figure 4C). Thelonectria rubi has the highest number of unique clusters (81) with the majority related to biological (GO: 0008150), metabolic (GO: 0008152), and cellular metabolic (GO: 0044237) processes, and N. coccinea has the lowest number of unique clusters (6), with three related to biological (GO: 0008150), cellular (GO: 0009987), and developmental (GO: 0032502) processes.

When orthologous gene clusters were analyzed using 21 different species of Sordariomycetes, only N. faginata displayed species specific orthologous gene clusters when compared to N. coccinea (Supplementary Table S3). These species-specific clusters could be used to generate PCR or qPCR assays aimed to the detection and discrimination of all species that can participate in the BBD complex (N. faginata, N. coccinea, and N. ditissima) (Feau et al. 2018). Due to the morphological similarity among N. faginata, N. coccinea, and N. ditissima, these markers could also be used for the identification of species present at infection points, for the detection of these pathogens in the early stages of the disease when there are no obvious signs of the fungi in the tissues to potentially uncover early latent stages in their life cycles, or detection in environmental samples.

Cytochrome P450 proteins

The genomes of N. faginata and N. coccinea contained a total of 115 and 114 CYPs, respectively. A total of 145 CYPs were found in the genome of N. ditissima, the highest number among the genomes studied. A total of 122 CYPs were found for T. rubi and C. fuckeliana had 98 CYPs, the lowest number in comparison. Subsequent BLASTP analyses at the FCPD indicated that the majority of CYP genes in N. faginata and N. coccinea, as well as N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi are similar to those of other known hypocrealean fungi such as F. graminearum, F. oxysporum, Neocosmospora solani (syn. Fusarium solani), Verticillium albo-atrum, Trichoderma reesei and T. virens, Sordariomycetes such as Cryphonectria parasitica, Magnaporthe oryzae, and others in the Pezizomycotina including Aspergillus niger and Pseudocercospora fijiensis (Supplementary Table S4). Following Nelson’s nomenclature (Nelson 2009), the CYP proteins of N. faginata and N. coccinea were classified into 50 and 51 families, and 54 and 58 subfamilies, respectively. N. ditissima CYPs were classified into 65 families and 79 subfamilies, and both C. fuckeliana and T. rubi CYPs were classified into 50 families and 56 subfamilies (Supplementary Table S4). Additionally, BLASTP results at the FCPD database and Nelson’s best hits also revealed the presence of a small number of CYPs in all species studied having homology to CYPs in Basidiomycete species such as Phanerochaete chrysosporium (e.g., CYP63, CYP5139, CYP5150, and CYP512) and Ustilago maydis (e.g., CYP 5032, CYP5027), and Oomycete species such as Phytophthora ramorum and P. sojae (CYP5014, CYP5015) (Supplementary Table S4). To date, similarity of ascomycete CYPs to those of basidiomycetes has only been reported in the chestnut blight pathogen C. parasitica (Crouch et al. 2020); however, based on the results reported here, this phenomenon may not be uncommon among fungal forest tree pathogens. The oomycete CYPs 5014 and 5015 were the most commonly matched to the fungal CYPs found in this study. This CYP sequence similarity could be resulting from convergent evolution and a reflection of the comparable ecological niche these organism share, where lifestyles involve the biotransformation of the different components of lignocellulosic biomasses for fungal colonization and pathogenesis-related host invasion (Martinez et al. 2004; Syed et al. 2014; Qhanya et al. 2015). Approximately 13–24% of CYPs from all species could not be assigned to an appropriate family and subfamily based on lack of matches to the FCPD database.

Virulence associated genes

The frequency of virulence associated genes relative to the total number of predicted proteins was the same for all the species (32.0–32.8%), except for T. rubi, which showed a relatively lower frequency (30.9%) (Table 3). For N. faginata and N. coccinea, the pathogenicity genes found within the predicted proteins matched 1892 and 1889 PHI-base accessions, respectively. Similarly, N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi pathogenicity genes matched 1885, 1827, and 1869 PHI-base accessions, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). The majority of the genes with PHI-base accessions hits belonged to the categories where the mutagenesis has no effect on pathogenicity (unaffected pathogenicity, 1539–1947) and mutagenesis was associated with reduced virulence (1431–1891) (Table 3). N. ditissima had the highest number of effectors (27), followed by N. faginata (26), T. rubi (22), and N. coccinea, C. fuckeliana had the lowest (19). Relatively similar numbers of genes associated to chemistry target, enhanced antagonism, hypervirulence, lethal, loss of pathogenicity and mixed outcome was showed by all the genomes analyzed (Table 3). Mutations related to enhanced antagonism showed the smallest amount of PHI-base hits (1–2) in all the species. Among the predicted genes with PHI-base accession hits, some were unique to each one of the species studied. N. faginata and N. coccinea had 27 and 35 unique PHI-base accession hits, respectively, and 18 additional that were shared between them. N. ditissima had 35 unique hits, T. rubi had the largest amount of unique PHI-base accession hits (62) and C. fuckeliana the lowest with 27 unique hits. Among the 35 unique PHI-base accessions for N. coccinea, 13 matched known mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) (e.g., PHI: 113, 246, 263, 266, 1032, 1042, 2367, 2559, and 4639) in other species of Sordariomycetes. No MAP kinases were found among the unique PHI-base hits shown by N. faginata. The N. coccinea MAPK genes could be pathogenicity determinants as they have similarities to those of known fungal plant pathogens such as F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Ding et al. 2015) and M. oryzae (Xu et al. 1998). These proteins have been proven to affect appressorium function, host invasive growth and colonization, sporulation (conidiation and ascospore formation), fertility and virulence. Since MAPK are essential virulence determinants, the additional genes observed in N. coccinea may be related to the functional divergence that could exist between these two species, and although needing experimental validation, possibly contributing to differences in disease severity. Zinc-containing class III transcription factors were also found among the unique PHI-base hits of all the species analyzed (PHI: 5595, 5601, 5623, 5641, and 5657). With the exception of N. faginata, all remaining species had gene models with unique PHI-base accession hits that matched known F. graminearum transcription factors (e.g., PHI: 1307, 1394, and 1686) (Son et al. 2011) (Supplementary Table S5).

Table 3.

Summary of predicted genes associated with virulence after screening against the phi-base

| Neonectria faginata | Neonectria coccinea | Neonectria ditissima | Corinectria fuckeliana | Thelonectria rubi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistry target | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Effector | 26 | 19 | 27 | 19 | 22 |

| Enhanced antagonism | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Hypervirulence | 91 | 91 | 92 | 90 | 85 |

| Lethal | 162 | 172 | 179 | 163 | 158 |

| Loss of pathogenicity | 215 | 248 | 265 | 235 | 225 |

| Reduced virulence | 1,600 | 1,867 | 1,891 | 1,610 | 1,461 |

| Unaffected pathogenicity | 1,719 | 1,833 | 1,947 | 1,539 | 1,629 |

| Mixed outcomea | 405 | 113 | 14 | 9 | 431 |

| Total | 4,226 | 4,252 | 4,423 | 3,672 | 4,017 |

| Relative frequency (genome) (%) | 32.5 | 32.8 | 32.3 | 32 | 30.9 |

Phenotyping term used to identify genes where a range of interaction outcomes have been identified depending on the host species and/or tissue type evaluated (Urban et al. 2015).

Secreted proteins and secondary metabolite clusters

A total of 463 and 478 genes were predicted to encode secreted proteins in N. faginata and N. coccinea, respectively. N. ditissima showed 517 secreted proteins, C. fuckeliana 387 and T. rubi 439 (Supplementary Table S6). The total number of predicted secreted proteins found account for 3.38–3.78% of the total number of protein models of all genomes evaluated. This similarity in the number of predicted secreted proteins may be due to the close phylogenetic relationship these species share and not to their similar lifestyle (pathogens of ornamental and forest hardwood trees) (Krijger et al. 2014). Nonetheless, as the order Hypocreales harbor a variety of species with distinct parasitic lifestyles that include animals, plants and other fungi (Sung et al. 2008), variations in the specific composition of the secreted protein arsenals have indeed been observed (Druzhinina et al. 2012; Girard et al. 2013; Staats et al. 2014; de Man et al. 2016; Rivera et al. 2018). Among the proteins classified as secreted in N. faginata and N. coccinea, a total of 40 and 45 were classified as peptidases, respectively, based on functional annotations performed at the Pfam v. 32.0 database website (https://pfam.xfam.org; El-Gebali et al. 2019). A total of 49, 42, and 43 peptidases were also found among the secreted proteins of N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi, respectively. Contrary to what is seen in the differences in fungal secretomes, which seem to be more dependent on phylogenetic distances than in lifestyles, peptidases content in fungi depends on their adaptation to different ecological niches (St Leger et al. 1997). As typical hemibiotrophs, the beech bark pathogens contain a smaller set of peptidases when compared with other species in the Hypocreales with different lifestyles such as mycotrophic species of Trichoderma (383–489 peptidases; Druzhinina et al. 2012) and necrotrophic species of Fusarium (278–284 peptidases, Ohm et al. 2012). The most common peptidases found in all species are subtilases, prolyl oligopeptidases, metallopeptidases, serine carboxypeptidases and zinc carboxypeptidases. Aspartyl proteases were found on all secreted proteins except on those by N. faginata (Supplementary Table S6). These peptidases have been found linked to the different lifestyle transitions that characterize the different families and species in the Hypocreales (Varshney et al., 2016), also playing a role in the protection of fungal cells against host defense peptidases, for example plant chitinases (Karimi Jashni et al. 2015). Detailed analyses of the different kinds and families of peptidases produced by the BBD pathogens and their counterpart peptidases in plants might help increase our understanding of host defense responses that can be further exploited during traditional breeding or transgenic engineered resistance. Using EffectorP v2.0 it was found that the percentage of secreted proteins determined as putative effector proteins from all species in this study ranged from 9.8 to 15.5%. A total of 58 and 63 secreted proteins in N. faginata and N. coccinea, respectively were classified as putative effector proteins while N. ditissima and T. rubi showed 71 and 68 putative effectors, respectively. Corinectria fuckeliana showed the smallest number of putative effectors (38) (Supplementary Table S6).

The predicted proteomes of N. faginata and N. coccinea, and those of N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi contained relatively similar numbers of secondary metabolism biosynthetic clusters (Table 4). N. faginata and N. coccinea contained a total of 33 and 37 clusters, respectively. In a similar fashion, the predicted proteomes of N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi contained 39, 40, and 27 secondary metabolism biosynthetic clusters respectively. Gene clusters associated with nonribosomal peptide synthesis (NPRS) and clusters associated with polyketide biosynthesis (PKS) are predominant in the predicted proteomes of all species (Table 4). N. faginata and N. coccinea contained one cluster of indole-derived metabolites each; however only N. faginata contained one additional beta-lactone containing protease inhibitor cluster. Only one type III PKS cluster was detected on each of the five genomes studied. A small number of the secondary metabolite biosynthetic clusters found shared more than 70% sequence similarity to known and studied biosynthetic gene clusters in the MIBiG database (Kautsar et al. 2020). These are associated with metabolites with inhibitory and antibiotic activity that could be involved in pathogenicity and virulence (Supplementary Table S7).

Table 4.

Secondary metabolite clusters identified from the predicted proteomes of the species included in this study

| Type I PKS | Type III PKS | NRPS | Terpene clusters | Othersa | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonectria faginata | 10 | 1 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 33 |

| Neonectria coccinea | 12 | 1 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 37 |

| Neonectria ditissima | 16 | 1 | 23 | 6 | 0 | 39 |

| Corinectria fuckeliana | 17 | 1 | 22 | 5 | 0 | 40 |

| Thelonectria rubi | 8 | 1 | 14 | 6 | 0 | 27 |

Complete list included in Supplementary Table 7.

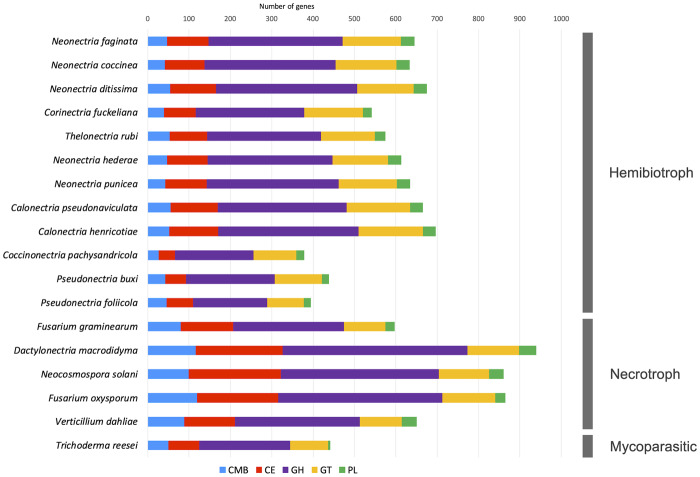

Carbohydrate-active enzymes

The total number of CAZyme modules identified in the predicted proteomes of N. faginata, N. coccinea, N. ditissima, and C. fuckeliana ranged from 627 (C. fuckeliana) to 757 (N. faginata) (Table 5). Among the total number of CAZymes modules, 33–35% were predicted to harbor a signal peptide and were classified as potential secreted proteins (Table 5). The relative frequency of CAZyme modules over the predicted proteome was similar for all species, ranging from 5.18 to 5.82%. Independent samples t tests and X2 test of independence found no significant differences in the total number of CAZyme modules between N. faginata and N. coccinea and among all the species used in this study. No significant differences were also detected among the numbers of distinct CAZYme module families identified in these species (Table 5, Supplementary Table S8). Glycoside hydrolase (GHs) families account for 40–43% of the CAZyme modules found on these species (Supplementary Table S8). Among the CAZyme modules found in higher numbers in the BBD pathogens are auxiliary activity (AA) enzymes (e.g., 3, 7) that may play a role in plant infection and invasion, lesion formation and expansion within the plant cells (Sützl et al. 2018); polysaccharide lyases (PL) families (e.g., 1, 3) with pectate lyase activities that can cause plant tissue maceration, cell lysis and modification of the cell wall structure (Zhao et al. 2013; Atanasova et al. 2018); and carbohydrate binding modules (CBM) families 1, 48, 50, and 67 known to have roles in degradation of insoluble polysaccharides and plant cellulose, (Zhao et al. 2013), in the processing of starchy substrates and in the processing of peptidoglycans and chitin and contribute to antifungal activities (Akcapinar et al. 2015). GH 3, 16, 18, and 43 were among the most abundant families of GH found. GH18 family groups are important fungal chitinases that together with CBM50, have activities in fungal–fungal interaction but also in physiological processes such as sporulation and reducing the action of plant chitinases, thereby preventing the recognition of fungi by the plant immune system (Tzelepis et al. 2015).

Table 5.

Sizes of CAZyme module classes identified from the predicted proteomes of nectriaceous fungi

| Species | CBM | CE | GH | GT | PL | AA | Total | Secreteda | RF (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonectria faginata | 47 | 100 | 324 | 141 | 33 | 112 | 757 | 251 | 5.82 |

| Neonectria coccinea | 42 | 95 | 317 | 147 | 32 | 122 | 755 | 251 | 5.83 |

| Neonectria ditissima | 54 | 111 | 342 | 136 | 32 | 121 | 796 | 257 | 5.82 |

| Corinectria fuckeliana | 39 | 77 | 263 | 141 | 22 | 85 | 627 | 207 | 5.47 |

| Thelonectria rubi | 53 | 91 | 275 | 130 | 26 | 98 | 673 | 238 | 5.18 |

Number of CAZyme modules with positive signal peptide prediction.

Relative frequency of CAZyme modules over the total number of predicted proteins.

CMB, carbohydrate-binding modules; CE, carbohydrate esterases; GH, glycoside hydrolases; GT, glycosyl transferases; PL, polysaccharide lyases; AA, auxiliary enzymes.

A comparison of the total CAZyme modules found in N. faginata, N. coccinea, N. ditissima, C. fuckeliana, and T. rubi with other hypocrealean fungi with distinct trophic lifestyles was also performed. Even though independent samples t tests and X2 test of independence found no significant differences in the total number of CAZyme modules between the main fungal species focus of this study and other nectriaceous species having hemibiotrophic or mycoparasitic lifestyles (Figure 5), the CAZyme profile of N. faginata and N. coccinea is more consistent with the CAZyme complement observed in other hemibiotropic hypocrealean fungi (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S8). On the other hand, significant differences (P < 0.001) were found when compared with CAZyme modules present in nectriaceous species with a necrotrophic lifestyle (Figure 5). Enzyme modules CBM, CE and GT account for the majority of the significant differences observed, with the species in this study showing CMB and CE enzymes numbers lower (P < 0.001), and GT enzyme numbers higher (P < 0.001) than those of the necrotrophic species D. macrodidyma, F. graminearum, F. oxysporum, Neocosmospora solani, and V. dahliae, respectively (Figure 5). Information about CAZyme composition is essential for the determination of fungal trophic phenotypes in fungi, which in turn can increase the assessment and effectiveness of management strategies adopted for disease control (Hane et al. 2019).

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of CAZyme modules predicted in the species included in this study and other Hypocrealean fungi.

Conclusions

BBD emerged as an important disease of American beech more than a century ago and continues to be a serious threat to beech trees and their forest ecosystems. The genome analyses included in this study show that due to the relatively recent species divergence and close phylogenetic relatedness, N. faginata and N. coccinea display many similarities at the genome level, including size, gene content, predicted secreted proteins and effectors, secondary metabolite clusters and carbohydrate active enzymes. Detailed analysis of genomic features revealed interesting differences between these two pathogens, including size and intron composition of mitochondrial DNA in N. faginata and potential expansion of MAPKs genes in N. coccinea, known to play key roles in pathogen-host interaction that could be affecting the virulence level observed between these species. The overall observation of many genome level similarities between N. faginata and N. coccinea highlights the need of continued vigilance to prevent the introduction of N. coccinea to North America or of N. faginata to Europe to avoid the potential detrimental effects interspecific hybridization could have on the evolution of this disease and the pathogens involved. This study provides quality reference genome sequences for these important pathogens of beech trees and facilitates new functional and evolutionary studies aimed at understanding the biological processes that make N. faginata and N. coccinea successful hemibiotrophic pathogens. This knowledge will result in a better understanding and management of BBD.

Acknowledgments

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA. The USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from USDA-ARS project 8042-22000-298-00-D and by the appointment of D.N. Skaltsas to the USDA ARS Research Participation Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy (DOE) and the USDA. ORISE is managed by Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) under DOE contract number DE-AC05-06OR23100.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Literature cited

- Al-Reedy RM, Malireddy R, Dillman CB, Kennell JC.. 2012. Comparative analysis of Fusarium mitochondrial genomes reveals a highly variable region that encodes an exceptionally large open reading frame. Fungal Genet Biol. 49:2–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akcapinar GB, Kappel L, Sezerman OU, Seidl-Seiboth V.. 2015. Molecular diversity of LysM carbohydrate-binding motifs in fungi. Curr Genet. 61:103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasova L, Dubey M, Grujić M, Gudmundsson M, Lorenz C, et al. 2018. Evolution and functional characterization of pectate lyase PEL12, a member of a highly expanded Clonostachys rosea polysaccharide lyase 1 family. BMC Microbiol. 18:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet D, Nadimi M, Iffis B, Hijri M.. 2013. Rapid mitochondrial genome evolution through invasion of mobile elements in two closely related species of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. PLoS One. 8:e60768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernt M, Donath A, Jühling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, et al. 2013. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 69:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blin K, Shaw S, Steinke K, Villebro R, Ziemert N, et al. 2019. antiSMASH 5.0: updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:W81–W87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH.. 2015. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 12:59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busk PK, Pilgaard B, Lezyk MJ, Meyer AS, Lange L.. 2017. Homology to peptide pattern for annotation of carbohydrate-active enzymes and prediction of function. BMC Bioinformatics. 18:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cale JA, Garrison-Johnston MT, Teale SA, Castello JD.. 2017. Beech bark disease in North America: over a century of research revisited. For Ecol Manag. 394:86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Hyten AS.. 2006. Phylogenetic relationships of Neonectria/Cylindrocarpon on Fagus in North America. Can J Bot. 84:1417–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Chaverri P, Salgado C, Hirooka Y, Rossman AY, Samuels GJ.. 2011. Delimitation of Neonectria and Cylindrocarpon (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales, Ascomycota) and related genera with Cylindrocarpon-like anamorphs. Stud Mycol. 68:57–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogbill CV. 2005. Historical biogeography of American beech. In: Beech Bark Disease: Proceedings of the Beech Bark Disease Symposium. Pennsylvania: USDA Forest Service, p. 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, et al. 2005. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 21:3674–3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortázar AR, Aransay AM, Alfaro M, Oguiza JA, Lavín JL.. 2014. SECRETOOL: integrated secretome analysis tool for fungi. Amino Acids. 46:471–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JA, Dawe A, Aerts A, Barry K, Churchill ACL, et al. 2020. Genome sequence of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica EP155: a fundamental resource for and archetypal invasive plant pathogen. Phytopathology. 110:1080–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Man TJB, Stajich JE, Kubicek CP, Teiling C, Chenthamara K, et al. 2016. Small genome of the fungus Escovopsis weberi a specialized disease agent of ant agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113:3567–3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng CH, Scheper RWA, Thrimawithana AH, Bowen JK.. 2015. Draft genome sequences of two isolates of the plant-pathogenic fungus Neonectria ditissima that differ in virulence. Genome Announc. 3:e01348–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Li M, Sun F, Xi P, Sun L, et al. 2015. Mitogen activated protein kinases are associated with the regulation PF physiological traits and virulence in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense. PLoS One. 10:e0122634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druzhinina IS, Shelest E, Kubicek CP.. 2012. Novel traits of Trichoderma predicted through the analysis of its secretome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 337:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gebali S, Mistry J, Bateman A, Eddy SR, Luciani A, et al. 2019. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:D427–D432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms DM, , Kelly S. 2015. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 10: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr DF, Rossman AY.. 2020. Fungal Databases, U.S. National Fungus Collections, ARS, USDA. (Accessed: 2020 June 1). https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/

- Feau N, Beauseigle S, Bergeron MJ, Bilodeau GJ, Birol I, et al. 2018. Genome-enhanced detection and identification (GEDI) of plant pathogens. PeerJ. 6:e4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemkhani M, Garkava-Gustavsson L, Liljeroth E, Nybom H.. 2016. Assessment of diversity and genetic relationships of Neonectria ditissima: the causal agent of fruit tree canker. Hereditas. 153:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard V, Dieryckx C, Job C, Job D.. 2013. Secretomes: the fungal strike force. Proteomics. 13:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff S, Vaughn M, McKay S, Lyons E, Stapleton A, et al. 2011. The iPlant Collaborative: cyberinfrastructure for plant biology. Front Plant Sci. 2:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Cortecero A, Harrison RJ, Armitage AD.. 2015. Draft genome sequence of a European isolate of the apple canker pathogen Neonectria ditissima. Genome Announc. 3:e01243–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Cortecero A, Saville RJ, Scheper RWA, Bowen JK, Agripino De Medeiros H, et al. 2016. Variation in host and pathogen in the Neonectria/Malus interaction; toward an understanding of the genetic basis of resistance to European Canker. Front Plant Sci. 7:1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JR, Stothard P.. 2008. The CGView server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W181–W184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane JK, Paxman J, Jones DAB, Oliver RP, de Wit P.. 2019. “CATAStrophy,” a genome-informed trophic classification of filamentous plant pathogens – how many different types of filamentous plant pathogens are there? Front Microbiol. 10:3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges SB, Marin J, Suleski M, Paymer M, Kumar S.. 2015. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol Biol Evol. 32:835–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Rossman AY, Zhuan W-Y, Salgado-Salazar C, Chaverri P.. 2013. Species delimitation for Neonectria coccinea group including the causal agents of beech bark disease in Asia, Europe and North America. Mycosystema. 32:485–517. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff KJ, Stanke M.. 2013. WebAUGUSTUS – a web service for training AUGUSTUS and predicting genes in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:W123–W128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston DR. 1994. Major new tree disease epidemics: beech bark disease. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 32:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Houston DR, Parker EJ, Perrin R, Lang KJ.. 1979. Beech bark disease: a comparison of the disease in North America, Great Britain, France, and Germany. Forest Pathol. 9:199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Joardar V, Abrams NF, Hostetler J, Paukstelis PJ, Pakala S, et al. 2012. Sequencing of mitochondrial genomes of nine Aspergillus and Penicillium species identifies mobile introns and accessory genes as main sources of genome size variability. BMC Genomics. 13:698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T. 2009. Beech decline in Central Europe driven by the interaction between Phytophthora infections and climatic extremes. For. Pathol. 39:73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jashni MK, Mehrabi R, Collemare J, Mesarich CH, de Wit PJGM.. 2015. The battle in the apoplast: further insights into the roles of proteases and their inhibitors in plant-pathogen interactions. Front Plant Sci. 6:584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautsar SA, Blin K, Shaw S, Navarro-Muñoz JC, Terlouw BR, et al. 2020. MIBiG 2.0: a repository for biosynthetic gene clusters of known function. Nucleic Acids Res. 48:D454–D458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura K, Kawano S.. 2001. Regional differentiation in genetic components for the American beech, Fagus grandifolia Ehrh., in relation to geological history and mode of reproduction. J Plant Res. 114:353–368. [Google Scholar]

- Krijger JJ, Thon MR, Deising HB, Wirsel SGR.. 2014. Compositions of fungal secretomes indicate a greater impact of phylogenetic history than lifestyle adaptations. BMC Genomics. 15:722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K.. 2018. MEGAX: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35:1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger RJS, Joshi L, Roberts DW.. 1997. Adaptation of proteases and carbohydrases of saprophytic, phytopathogenic and entomopathogenic fungi to the requirements of their ecological niches. Microbiology. 143:1983–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS.. 2003. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13:2178–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V, Ramulu HG, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Hensissat B.. 2014. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013). Nucleic Acids Res. 42:D1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney EM, Milgroom MG, Sinclair WA, Houston DR.. 1999. Origin, genetic diversity and population structure of Nectria coccinea var. faginata in North America. Mycologia. 91:583–592. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Larrondo LF, Putnam N, Gelpke MD, Huang K, et al. 2004. Genome sequence of the lignocellulose degrading fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium strain RP78. Nat Biotechnol. 22:695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moktali V, Park J, Fedorova-Abrams ND, Park B, Choi J, et al. 2012. Systematic and searchable classification of cytochrome P450 proteins encoded by fungal and oomycete genomes. BMC Genomics. 13:525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RS, Liebhold AM, Tobin PC, Gottschalk KW, Luzader E.. 2007. Spread of beech bark disease in the eastern United States and its relationship to regional forest composition. Can J for Res. 37:726–736. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR. 2009. The cytochrome p450 homepage. Hum Genomics. 4:59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm RA, Feau N, Henrissat B, Schoch CL, Horwitz BA, et al. 2012. Diverse lifestyles and strategies of plant pathogenesis encoded in the genomes of eighteen dothideomycetes fungi. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantou MP, Kouvelis VN, Typas MA.. 2008. The complete mitochondrial genome of Fusarium oxysporum: insights into fungal mitochondrial evolution. Gene. 419:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante F, Hamelin RC, Bernier L.. 2002. A comparative study of genetic diversity of populations of Nectria galligena and N. coccinea var. faginata in North America. Mycol. Res. 106:183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Persoon CH. 1800. Sphaeria aurantia Pers., Vol. 2. Leipzig: Icon. Desc. Fung. Min. Cognit. [Google Scholar]

- Qhanya LB, Matowane G, Chen W, Sun Y, Letsimo EM, et al. 2015. Genome-wide annotation and comparative analysis of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases in Basidiomycete biotrophic plant pathogens. PLoS One. 10:e0142100.,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Y, Salgado-Salazar C, Veltri D, Malapi-Wight M, Crouch JA.. 2018. Genome analysis of the ubiquitous boxwood pathogen Pseudonectria foliicola. PeerJ. 6:e5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman AY, Samuels GJ, Rogerson CT, Lowen R.. 1999. Genera of bionectriaceae, hypocreaceae and nectriaceae (hypocreales, ascomycetes). Stud Mycol. 42:1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Salazar C, Rossman AY, Samuels GJ, Hirooka Y, Sanchez RM, et al. 2015. The genus Thelonectria (Ascomycota, Nectriaceae, Hypocreales) and closely related species with cylindrocarpon-like asexual states. Fungal Divers. 70:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestro D, Michalak I.. 2012. raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org Divers Evol. 12:335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM.. 2015. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 31:3210–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaltsas DN, Salgado-Salazar C.. 2020. Genome resources for Thelonectria rubi the causal agent of Nectria canker of caneberry. Phytopathology. 110:723–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son H, Seo Y-S, Min K, Park AE, Lee J, et al. 2011. A phenome-based functional analysis of transcription factors in the cereal head blight fungus, Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperschneider J, Dodds PN, Gardiner DM, Singh KB, Taylor JM.. 2018. Improved prediction of fungal effector proteins from secretomes with EffectorP 2.0. Mol Plant Pathol. 19:2094–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats CC, Junges A, Muniz Guedes RL, Thompson CE, Loss de Morais G, et al. 2014. Comparative genome analysis of entomopathogenic fungi reveals a complex set of secreted proteins. BMC Genomics. 15:822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 30:1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauder CM, Garnas JR, Morrison EW, Salgado-Salazar C, Kasson MT.. 2020. Characterization of mating type genes in heterothallic Neonectria species, with emphasis on N. coccinea, N. ditissima and N. faginata. Mycologia. 112:880–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung G-H, Poinar GO, Spatafora JW.. 2008. The oldest fossil evidence of animal parasitism by fungi supports a Cretaceous diversification of fungal-arthropod symbioses. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 49:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sützl L, Laurent CVFP, Abrera AT, Schütz G, Ludwig R, et al. 2018. Multiplicity of enzymatic functions in the CAZy AA3 family. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 102:2477–2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed K, , Shale K, , Pagadala N S, , Tuszynski J. 2014. Systematic Identification and Evolutionary Analysis of Catalytically Versatile Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase Families Enriched in Model Basidiomycete Fungi. PLoS ONE. 9:e86683. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G, Castresana J.. 2007. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 56:564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Tao Q, Kumar S.. 2018. Theoretical foundation of the RelTime method for estimating divergence times from variable evolutionary rates. Mol Biol Evol. 35:1770–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Battistuzzi FU, Billing-Ross P, Murillo O, Filipski A, et al. 2012. Estimating divergence times in large molecular phylogenies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109:19333–19338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torriani SFF, Penselin D, Knogge W, Felder M, Taudien S, et al. 2014. Comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes from closely related Rhynchosporium species reveals extensive intron invasion. Fungal Genet Biol. 62:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzelepis G, Dubey M, Jensen DF, Karlsson M.. 2015. Identifying glycoside hydrolase family 18 genes in the mycoparasitic fungal species Clonostachys rosea. Microbiology (Reading). 161:1407–12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban M, Pant R, Raghunath A, Irvine A G, Pedro H, . et al. 2015. The Pathogen-Host Interactions database (PHI-base): additions and future developments. Nucleic Acids Research. 43:D645–D655. 10.1093/nar/gku1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney D, , Jaiswar A, , Adholeya A, , Prasad P. 2016. Phylogenetic analyses reveal molecular signatures associated with functional divergence among Subtilisin like Serine Proteases are linked to lifestyle transitions in Hypocreales. BMC Evol. Biol. 16:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Coleman-Derr D, Chen G, Gu YQ.. 2015. OrthoVenn: a web server for genome wide comparison and annotation of orthologous clusters across multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:W78–W84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J-R, Staiger CJ, Hamer JE.. 1998. Inactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Mps1 from the rice blast fungus prevents penetration of hosts cells but allows activation of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 95:12713–12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Dong Z, Fang L, Luo Y, Wei Z, et al. 2019. OrthoVenn2: a web server for whole-genome comparison and annotation of orthologous clusters across multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:W52–W58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Mao Z, Yang J, Chen X, Mao F, et al. 2012. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate – active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:W445–W451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Yohe T, Huang L, Entwistle S, Wu P, et al. 2018. dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:W95–W101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Liu H, Wang C, Xu J-R.. 2013. Comparative analysis of fungal genomes reveals different plant cell wall degrading capacity in fungi. BMC Genomics. 14:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This Whole Genome Shotgun project, including sequencing reads, has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under BioProject PRJNA593731, accession numbers WPDD00000000 (N. faginata CBS 134246), WPDF00000000 (N. coccinea CBS 119158), WPDG00000000 (N. ditissima CBS 226.31), WPDH00000000 (C. fuckeliana CBS 125109). Supplementary material is available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25387/g3.14050034.