Abstract

This study investigated the impact of humidity and temperature on the spread of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) by statistically comparing modelled pandemic dynamics (daily infection and recovery cases) with daily temperature and humidity of three climate zones (Mainland China, South America and Africa) from January to August 2020. We modelled the pandemic growth using a simple logistic function to derive information of the viral infection and describe the growth of infected and recovered cases. The results indicate that the infected and recovered cases of the first wave were controlled in China and managed in both South America and Africa. There is a negative correlation between both humidity (r = − 0.21; p = 0.27) and temperature (r = −0.22; p = 0.24) with spread of the virus. Though this study did not fully encompass socio-cultural factors, we recognise that local government responses, general health policies, population density and transportation could also affect the spread of the virus. The pandemic can be managed better in the second wave if stricter safety protocols are implemented. We urge various units to collaborate strongly and call on countries to adhere to stronger safety protocols in the second wave.

Keywords: COVID-19, Humidity, Pandemic growth, SARS-CoV-2, Socio-cultural factors, Temperature

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease scientifically reclassified COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Globally, as of 3:40pm CEST, 9 October 2020, there have been 36,754,395 confirmed cases, including 1,064,838 deaths, reported by WHO since the virus started from Wuhan in December 2019. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020). As spread of the virus intensified, many virologists likened its characteristics to influenza whose behaviour invoked an epidemiological hypothesis, asserting that, cold and dry (low humidity) environments favour the survival and spread of droplet-mediated viral diseases (Liu et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Azuma et al., 2020; Casanova et al., 2010; Sarkodie and Owusu, 2020; Sizun et al., 2000; Redding et al., 2020). Several studies investigated the relationship between temperature and humidity on the spread of the virus. However, these studies have not been able to confirm with strong scientific evidence that temperature and humidity have significant effect on the spread of the virus. Commonly, previous studies have not tested sufficiently wide sample geographic locations to make this assertion.

SARS-CoV-2 virus is transmitted from person to person through respiratory (aerosol and droplet) and contact media (Rothan and Byrareddy, 2020; Rahimi et al., 2021; Wang et al. 2020a, 2020c). Transmission can either be direct through droplet and person-to-person or indirectly through contaminated objects/airborne to infect the respiratory system. If droplets and bioaerosols containing the virus enter the body, they may cause infection while an unprotected contact with a contaminated object is a potential risk of infection. The risk of transmission is highest when people are in close proximity (within 2 m). Van Doremalen et al. (2020), studied aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1 in China and concluded that SARS-CoV-2 could suspend in the air much longer. Airborne transmissions intensify in poorly ventilated indoor spaces where people are in close proximity (Rosario et al., 2020; Coccia, 2020a, b; Travaglio et al., 2020). Airborne transmissions can also occur in health settings that generate aerosols to support SARS-CoV-2 treatments.

Meteorological weather conditions including humidity, temperature, air pollution (particulate matter (PM) and gas-based pollutants) and wind speed intensify the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (Coccia, 2020a, 2020b, Rahimi et al., 2021, Han et al., 2021). For example, Wei et al. (2020) discovered that in the presence of accumulated PM 2.5, PM10 and other pollutants, microorganism attach themselves for anchorage and nutrients to enhance their toxicity. Groulx et al. (2018) and Zhang et al. (2019) discovered that microorganisms mix with particulate matter (PM) and air pollutants and strive better under such conditions. Wu et al. (2020) found positive association between COVID-19 Infection cases and particulate matter concentration in 3000 states in the United States. Wang et al. (2020a), Travaglio et al. (2020) and Yongjian et al. (2020) found a positive relationship between air pollution and COVID-19 mortality rate. Coccia (2020b) discovered that cities with atmospheric turbulence (higher wind speed) and lower levels of air pollution had lower COVID-19 infection rates. Studies conducted in Italy and California suggest that colder weather and air pollutants are associated with increased COVID-19 incidence (Bashir et al., 2020; Fattorini and Regoli, 2020), while studies conducted in Iran and Spain suggest that there is a correlation between temperature and COVID-19 (Briz-Redon and Serrano-Aroca, 2020; Ahmadi et al., 2020). Yang et al. (2020), observed that decreased relative humidity and maximum temperature and increased air pollution incidences interacted during the summer to cause increased incidence rates in arid inland cities. Wang et al. (2020f), Roy and Kar (2020), and Nazari Harmooshi et al. (2020) argued that decreased transmissibility ensues when outdoor temperatures and humidity are higher. Other studies by Ma et al. (2020); Bypass (2020); Xie and Zhu (2020) and Al-Rousan and Al-Najjar (2020) confirmed that temperature affects the transmission of the virus.

Comparing the current SARS-CoV-2 to the previous SARS-CoV-1, Fagbo et al. (2017), Lowen et al. (2007) and other studies drew a parallel analysis and concluded that since there exist an inverse relationship between warm temperatures and viral infections (including influenza, MERS-CoV and other coronaviruses), the activity of SARS-CoV-2 would subside when the climate becomes warmer. However, their comparison lacked mathematical and statistical connectedness as well as an in-depth expository of socio-cultural dynamics on viral growth rules. Therefore, contrary to their assertion, cases of SARS-CoV-2 continued to increase in warm climate countries including Egypt, India, Iran, and Brazil, controverting the hypothesis (Zhao et al., 2020). Cultural hegemony, religious dogma, government responses and geo-political ambiences could interrupt the scientific hypothetical argument but previous studies have not examined sufficiently wide sample locations. In temperate countries like England, increased temperature could result in increased outings due to warm weather, resulting in increased person-to-person contact and a possibility of increased atmospheric viral concentrations. On the other hand, in some tropical zones (especially developing countries with warmer temperatures), increased temperature will result in the opposite as people will rather limit movement to seek shelter from the sun. Increased rainy days in most tropical African countries will withdraw people to their homes and decrease person-to-person contact.

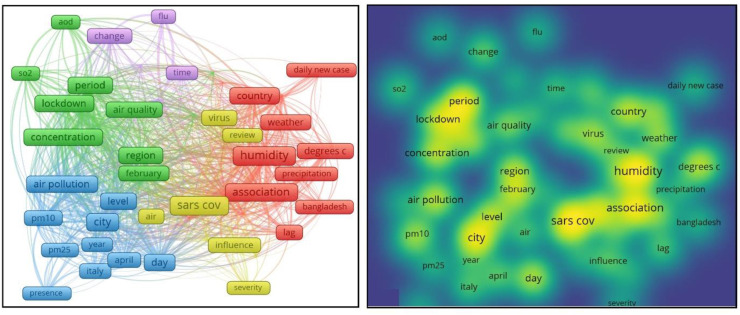

To attain a comprehensive summary of the findings of previous studies, we conducted a brief bibliometric review. The review was done to categorise the scope of studies into two groupings: (i) studies which correlate COVID-19 positively with temperature or humidity and, (ii) studies which correlate negatively with temperature or humidity. As a result, we did a brief keyword concurrence search to analyse the general status of the research field and identify current studies as well as hotspot areas. The studies are summarised in Table 1 and a keyword concurrence shown in Fig. 1 . Note that the term ‘climatic variables’ is sometimes used as a larger domain for temperature and humidity for the purposes of literature review which requires the mention of a larger set to which temperature and humidity belong. From Table 1, eight of the studies used data from China while the rest examined various parts of the world. Only one of the studies from China showed a negative correlation between temperature and COVID-19 (i.e. every unit increase in temperature was associated with decreasing COVID-19 cases). Ten (10) studies were done outside China; six (6) of that reported a strong correlation between temperature and humidity, and spread of the virus; three (3) showed no/weak correlation, while one (1) was uncertain. Note the stars bullet pointing the articles: the red star bulleted articles indicate studies that drew no or weak correlation with temperature. The green star indicates studies that drew a strong correlation with temperature, while the yellow star indicates studies with uncertain outcomes. Some studies reported a positive relationship between the spread of the virus with temperature (Wu et al., 2020; Bashir et al., 2020; Tosepu et al., 2020; Sobral et al., 2020; Prata et al., 2020, Xie and Zhu, 2020). Others reported a negative relationship (Haque and Rahman, 2020; Rosario et al., 2020). Some reported no, or weak correlation between temperature and spread of the virus (Ma et al., 2020; Demongeot et al., 2020; Iqbal et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; To et al., 2021). While others suggested an optimum temperature from 5 °C to 15 °C, as ideal for the transmission of the virus (Gunthe et al., 2020; Sajadi et al., 2020). The presence of mixed and contrasting evidence among observational studies warrant the need for further investigation into this scientific issue.

Table 1.

Summary of previous studies and their rule on COVID-19 association with climatic weather conditions.

| Title of Article | Authors | Journal | City/Location | Summary of findings | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Impact of climate and ambient air pollution on the epidemic growth During COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Impact of climate and ambient air pollution on the epidemic growth During COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. |

Kenichi et al. | Environ Research | Japan | Growth of COVID-19 is significantly associated with increase in daily temperature, and or sunshine hours. | Environ Research: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110042. |

Impact of meteorological factors on COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Top 20 countries with confirmed cases. Impact of meteorological factors on COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Top 20 countries with confirmed cases. |

Sarkodie and Owusu | Environ Research | 20 countries | There is strong correlation between temperature relative humidity on COVID-19 cases. | Environ Research: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110101 |

Correlation of ambient temperature COVID-19 incidence in Canada Correlation of ambient temperature COVID-19 incidence in Canada |

ToT et al. | Sci. Total Env. | Canada | There is no correlation between temperature and COVID-19. | TBA |

Investigation of effective climatology, Parameters on COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. Investigation of effective climatology, Parameters on COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. |

Ahmadi M et al. | Sci. Total Env. | Iran | There is no correlation between air temperature and COVID-19 cases. | Sci. Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138811 |

A spatio-temporal analysis for exploring the effect of temperature on COVID-19 early evolution in Spain. A spatio-temporal analysis for exploring the effect of temperature on COVID-19 early evolution in Spain. |

Briz-Redon & Serrano-Aroca A | Sci. Total Env. | Spain | No significant evidence of relationship | Sci. Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138811 |

Effects of Temperature Variation and humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China Effects of Temperature Variation and humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China |

Ma Y et al. | Sci. Total Env. | China | 1 unit increase in temperature and humidity resulted in COVID-19 death in lag 3 and 5 with significant decreases in lag 3 and 5. | Sci. Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138201. |

Eco-epidemiological Assessment of the COVID-19 epidemic January–February 2020 Eco-epidemiological Assessment of the COVID-19 epidemic January–February 2020 |

Bypass P | Global Health Action | China | Adjusted incidence rate ratios suggested brighter, warmer and drier conditions were associated with lower incidence | Glob Health Act. 10.1080/16549716.2020.1760490 |

Association between ambient Temperature and COVID-19 Infection in 122 cities from China Association between ambient Temperature and COVID-19 Infection in 122 cities from China |

Xie J et al. | Sci. Total Env. | China | Below 3 °C mean temperature each 1 °C rise was associated with a 4.861% increase in daily COVID-19 cases | Sci. Total. Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020138201. |

The correlation between the Spread of COVID-19 infections And weather variables in 30 Chinese provinces and the impact Of Chinese government mitigation Plans The correlation between the Spread of COVID-19 infections And weather variables in 30 Chinese provinces and the impact Of Chinese government mitigation Plans |

Al-Rousan N et al. | Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci | China | Weather conditions (temperature) and short-wave radiation increases the number of confirmed fatal and recovered cases | Eur 10.26355/eurrev_202004_ 212042 |

The nexus between COVID-19, Temperature and exchange rate in Wuhan City: New findings from partial And multiple wavelet coherence The nexus between COVID-19, Temperature and exchange rate in Wuhan City: New findings from partial And multiple wavelet coherence |

Iqbal N et al. | Sci. Total Environ | China | Increase in temperature does not significantly contain or slow down new COVID-19 infections | Sci. Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138916 |

Effect of ambient air pollutants and Meteorological variables on COVID-19 Incidence Effect of ambient air pollutants and Meteorological variables on COVID-19 Incidence |

Jiang Y et al. Epidemiol | Infect Control Hosp | China | The relative risk of temperature and COVID-19 cases was 0.738–0.969 but may not be independent of PM10 | Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 10.1017/ice.2020.222 |

Temperature significantly changes COVID-19 transmission in (sub) tropical Cities of Brazil Temperature significantly changes COVID-19 transmission in (sub) tropical Cities of Brazil |

Prata DN et al. | Sci Total Env. | Brazil | A 1 °C rise in temperature was associated with a −4.895% (t = −2.29, p = 0.0226) decrease in number of daily cumulative confirmed cases of COVID-19. The curve flattened at 25.8 °C. However, there is no evidence that suggest that the curve declined at temperatures above 25.8 0 C. | Sci. Total Env. 10.1026/j.scitotenv.2020.138862. |

Temperature Decreases Spread Administrative Parameters of the COVID-19 case dynamics Temperature Decreases Spread Administrative Parameters of the COVID-19 case dynamics |

Demongeot J et al. | Biology | 21 French regions | High temperatures diminish initial contagion rates but seasonal temperature effects at later stages of epidemic cannot be proven | Biology (Basel). 10.3390/biology90500094. |

Effects of temperature variation and Humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Effects of temperature variation and Humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. |

Ma Y et al. | Sci. Total Env. | China | A unit increase in temperature and humidity resulted in decrease COVID-19 deaths in the 3rd and 5th lag. | Sci Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138226. |

Association between climate variables And global transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Association between climate variables And global transmission of SARS-CoV-2 |

Sobral MFF et al. | Sci. Total Env. | Global | A 1° increase in daily temperature reduced the number of cases by 6.4 per day. | Sci Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138997 |

Correlation between weather and Covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta Indonesia. Correlation between weather and Covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta Indonesia. |

Tosepu R et al. | Sci. Total Env. | Indonesia with Covid-19 | Temperature significantly correlates | Sci. Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138436. |

Correlation between climate Indicators and COVID-19 pandemic In New York USA. Correlation between climate Indicators and COVID-19 pandemic In New York USA. |

Bashir MF et al. | Sci Total Environ | New York City | Minimum temperature, average temperature and air quality were significantly associated with COVID-19. | Sci. Total Environ. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020 |

Effects of temperature and humidity On the daily new cases and deaths of China COVID-19 in 166 countries Effects of temperature and humidity On the daily new cases and deaths of China COVID-19 in 166 countries |

Wu Y et al. | Sci. Total Env | 166 countries | A 1 °C increase in temperature resulted in 3.08% (95% Cl: 1.53%, 4.63%) reduction in daily new cases and a 1.19% (95% Cl: 0.44%, 1.95%) reduction in daily deaths. | Sci. Total Env. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020 |

Note:  Green star articles concluded that there is strong correlation between climatic variables and COVID-19.

Green star articles concluded that there is strong correlation between climatic variables and COVID-19.  Red star variables means there is no, or a weak correlation between climatic variables and COVID-19.

Red star variables means there is no, or a weak correlation between climatic variables and COVID-19.  Yellow star articles were uncertain about the correlation between climatic variables and COVID-19.

Yellow star articles were uncertain about the correlation between climatic variables and COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Keyword concurrence results of COVI-19 impact on climatic weather conditions.

Majority of previous studies have not sampled wider zones with varying cultural hegemony, different religious dogma, government responses and varied geo-political ambiences. Furthermore, previous studies included less than four months of data in their analyses, and largely not including the main effects in Africa and South America. Additionally, several manuscripts of previous studies were not peer reviewed (Araujo and Naimi, 2020; Al-Rousan and Al-Najjar, 2020; Bannister-Tyrrell et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Oliveiros et al., 2020; Poirier et al., 2020; Sajadi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a; Bhattacharjee 2020, Gupta, 2020; Khattabi et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020), due to the urgency of publication on the topic. This study covers a wider period encompassing all the seasons of the calendar year (summer, winter, autumn and spring). The objective of the study is to confirm or debunk the hypothesised rule whether temperature and humidity have an impact on COVID-19 spread. We also seek to do a brief literature summary on findings of previous studies to be able to juxtapose our findings in the context of other studies and present a conclusive recommendation. Understanding the true relationship between climatic conditions and COVID-19 after almost a year of its existence is necessary to inform management about their true relation.

2. Methods

We used a simple logistic model to describe the growth rules of infected and recovered cases of COVID-19 and draw their association with temperature and humidity by doing a parametric statistical test (t-test) and comparing growth rates with temperature and humidity using Pearson's correlation.

2.1. Brief bibliometric review

To provide a comprehensive overview of the stage of knowledge in the area, we conducted a brief bibliometric analysis. The analysis was also to identify the milestones chalked in the field by analysing the most cited studies and categorising them into groups based on findings on the subject matter. We explored Web of Science Core Collection Database in advanced search page, using Boolean Logic to search TS = (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Impact of COVID-19 on climatic weather variables OR impact of SARS-CoV-2 on climatic weather variables) in which the subject contains “SARS-CoV-2 Impact on temperature and humidity “and “COVID-19 Impact on climatic weather variables”. We searched for articles from 2019 to 2020. The initial screening identified 517 articles. After examining the full texts, 19 studies were shortlisted manually. We observed great homogeneity in the findings regarding the effect of climatic weather variables on the transmissibility of COVID-19. Cold and dry conditions were potential factors affecting the spread of the virus.

2.2. Research settings, sample and data

To ensure that our sample settings cover a wider scope geo-political ambience, we compared cases from three continents including selected countries in Africa, South America and China (Appendix 1 shows list of countries selected for the study) with varying meteorological weather conditions and different government responses to the pandemic. Previous studies largely excluded Africa and South America, which display major variations in meteorological weather conditions. The success of China in keeping initial growth rates down sets it as an ideal control to compare other countries. Another reason for selecting these countries was the great variation in intranational and intracontinental meteorological weather conditions. The cumulative confirmed and recovered cases of COVID-19 in China as well as African and South American countries from January to August 2020 was obtained from the John Hopkins COVID-19 real-time data (Lauren, 2020). Data for humidity and temperature from January to August 2020 was obtained from NASA's datasets at www.disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/GLDAS_CLSM025_DA1_D_EP_2.2/summary. We modelled confirmed and recovered cases of COVID-19 and correlated epidemic cases with climatic variables collected from January to August 2020.

2.3. Measures of variables of the study

Temperature and humidity were measured and compared with the epidemic growth rules in the selected countries. A parametric statistical test (t-test) was done to compare the difference between model parameters in China and selected African and South American countries while a Pearson correlation was used to compare the relationship between temperature and humidity with model parameters.

2.4. Data analysis procedure and epidemic curve modelling

We adopted the ‘logistic function’ as used in previous epidemic studies including COVID-19 (Han et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2003; Wang and Liu 2005). Based on the logistic function, we modelled the epidemic information of the viral infection cases in a typical logistic form equation (Eq. (1)):

| (1) |

Where indicates the general form of the cumulative number of infected or recovered patients at time; denotes the maximum number of infections or recoveries; k is the logistic growth rate, and is the semi-saturation period (SSP), which is the inflection point of the sigmoid curve. Before we applied this model in this study, we tested it on SARS data for China for 2003 and also confirmed with simulation results of China done by Han et al., (2020). We then further confirmed it with the Infected, death, and recovered cases of COVID-19 in this study. With the infected cases, there are three parameters in the model, while in dealing with the recovered cases, we fixed to the difference between the maximum number of cumulative infections and deaths, based on biological fact. In our model, , is the mathematically defined inflection point. In this study, we assume that is the time of inflection of the epidemic dynamics in a region. We processed the data and modelled them with custom scripts on MATLAB (the Math Works). The nonlinear least square (NLS) algorithm was adopted for data fitting and parameter estimation. We used the MATLAB function “nlinfit” to minimize the sum of squared differences between the data points and the fitted values.

2.5. Statistical comparison of covid-19 infection growth rules with temperature and humidity

A parametric statistical test (t-test) was done to test the difference between model parameters in China and selected African and South American countries while a Pearson correlation was used to compare the relationship between environmental indexes and model parameters.

3. Results

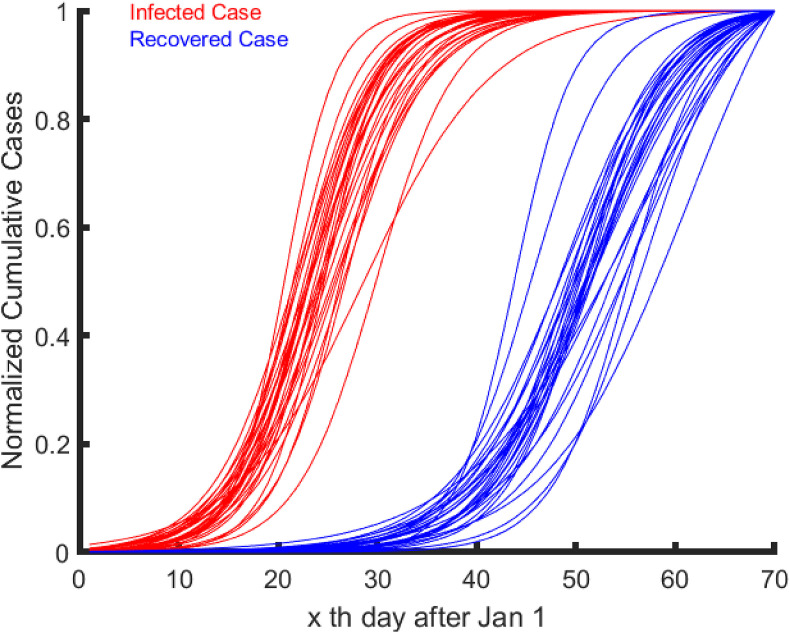

The first phase of the epidemic situation was controlled in China (Fig. 2 ) with a recovery rate of 94.5% (CCDC 2020). The time series of infected and recovered cases and their fitted curves for mainland China are shown in Fig. 2. Since China was the first country to control the pandemic successfully, this study first modelled cases in China separatetly, and also compared with other countries. In Fig. 2, each red line represents the time series of infected cases of a province while each blue line represents the time series of recovered cases of a province in China's mainland.

Fig. 2.

Fitted time series of first phase of COVID-19 infected and recovered cases in China's mainland.

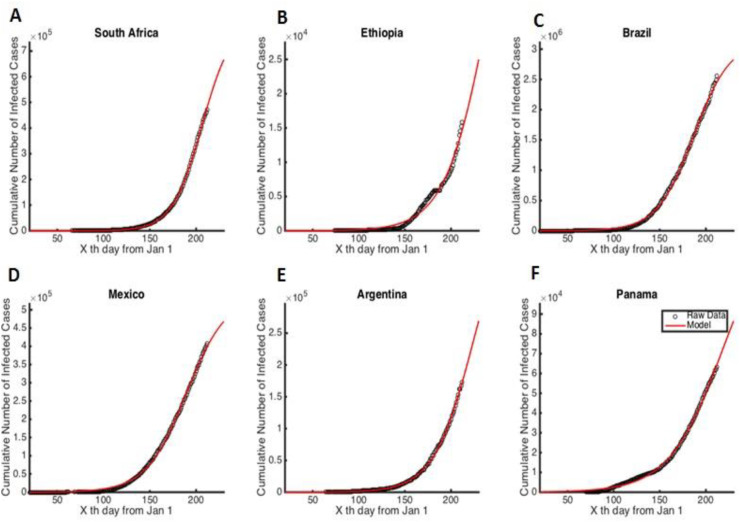

Based on this simulation, we applied the descriptive model to fit the data for the cumulative number of infected cases in some selected African and South American countries (Fig. 3 ). See the full list of countries in appendix 2.

Fig. 3.

Intrinsic growth rules of patients infected with COVID-19 in African and South American countries.

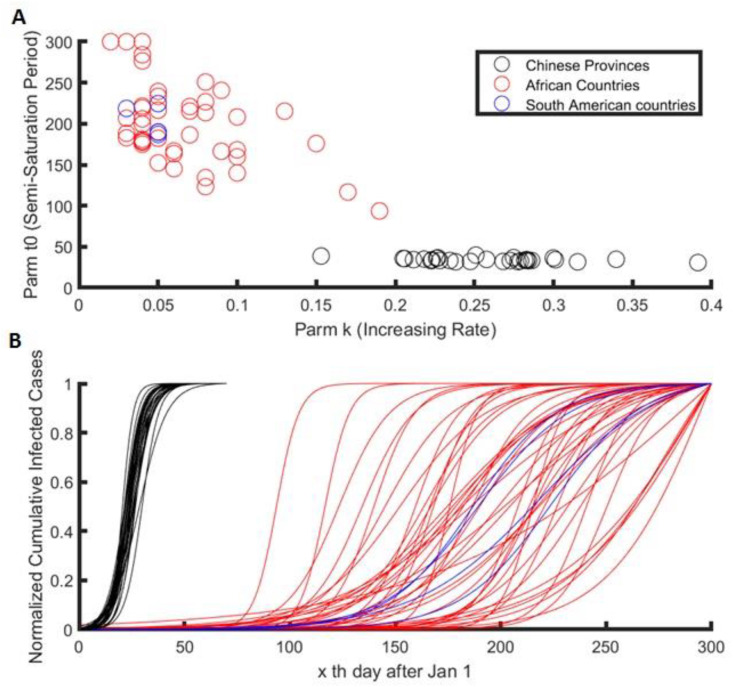

In Fig. 3 and appendix 2, all data series for infected growth cases are explained in the diagrams. Finally, we plotted all the fitted curves for China, Africa and South America to compare the intrinsic growth rules of these zones (Fig. 4 ). The black dots represent Chinese provinces, the blue dots represent selected African countries and the red dots represent selected South American countries. We noticed that, apart from China (Fig. 4A), the logistic growth rate of all African and South American countries does not show a significant difference between saturation point and infection rate.

Fig. 4.

Fitted curves for china, Africa and South America compared.

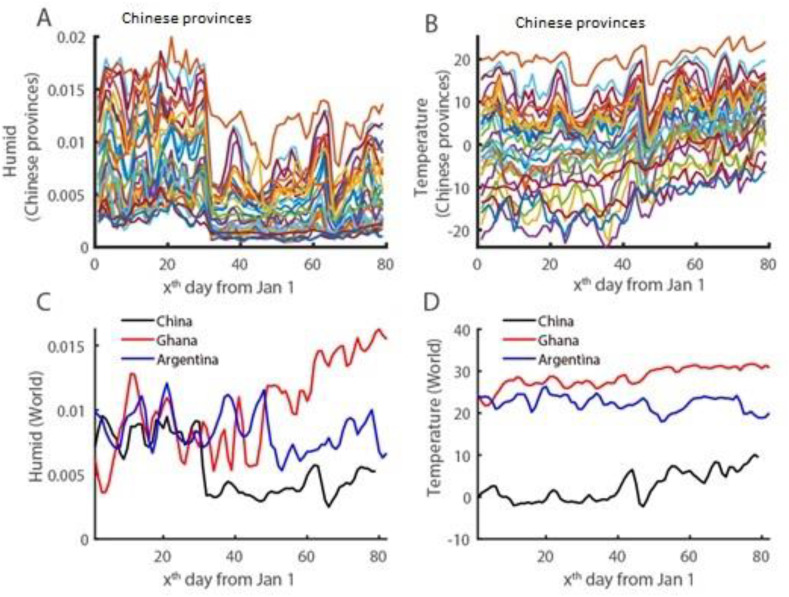

We compared temperature and humidity with growth rates and saturation points of the pandemic. Fig. 5 presents time series of humidity and temperature for provinces in China and some selected African countries. In Fig. 5A and B, each line indicates a province.

Fig. 5.

Time series dynamics of environment indexes (humid and temperature) compared in Chinese provinces and within China, Ghana and Argentina.

Table 2 summarises results of the association between temperature, humidity, and the pandemic growth. There is a negative correlation between mean humidity (r = −0.21; p = 0.27) and temperature (r = −0.22; p = 0.24) with spread of the virus. There is also a negative correlation between humidity (r = −0.18; p = 0.36) and temperature (r = −0.13; p = 0.51) with saturation of the virus. This means that, the virus strives faster in colder humid regions. A scatter plot explains this association in Appendix 2.

Table 2.

Summary of correlation results between temperature, humidity and spread of COVID-19.

| Humidity (Chinese Provinces) | Temperature (Chinese provinces) | |

|---|---|---|

| K | r = 0.21, p = 0.27 | r = 0.22, p = 0.24 |

| t0 | r = o.18, p = 0.36 | r = 0.13, p = 0.51 |

The relationship between temperature, humidity, and the epidemic growth rate were further compared for China, Ghana and Argentina in Table 3 and shown in Appendix 4.

Table 3.

Summary of relationship between dynamics of epidemic and environment indices for China, Ghana and Argentina.

| Humid (Ch) | Humid (Gh) | Humid (Arg) | Temp. (Ch) | Temp. (Gh) | Temp. (Arg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.0056 | 0.0137 | 0.007 | 2.47 | 28.57 | 16.11 |

| Std | 0.0022 | 0.0037 | 0.002 | 3.52 | 2.07 | 6.32 |

| k (Ch provinces) | k (Gh) | k (Arg) | t0 (Ch provinces) | t0 (Gh) | t0 (Arg) | |

| 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 34.18 | 205.91 | 224.51 | |

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the survival and spread of SARS-CoV-2 is influenced by temperature and humidity. Colder, less humid regions support the growth of the virus. This results supports findings of several studies mentioned earlier and confirms the hypothesis that cold and dry (low humidity) environments favour the survival and spread of droplet-mediated viral diseases including SARS-CoV-2 (Chan et al., 2011). SARS-CoV-2 is not temperature resistant and starts to break down at higher temperatures. Wang et al. (2020f), Roy and Kar (2020) and Nazari Har-mooshi et al. (2020) presented a broader perspective that confirms that there is decreased transmissibility of COVID-19 in higher outdoor temperatures and humidity. In the same regard, Biktasheva (2020) affirmed that there is a higher infection rate and respiratory sensitivity for some viruses in extreme low temperature and humidity conditions. Xu et al. (2020) found that in specific situations, meteorological parameters might affect the reproduction of SARS-CoV-2. Otter et al. (2016) confirmed that SARS-CoV-1 is affected by relative humidity and ambient temperature. Studies done in 122 Chinese cities confirm cases to decline by 4.9% when temperature increases by 1°С (Xie and Zhu, 2020). Qi et al. (2020), suggest that when average temperature is in the range 5.04⁰C-8.2 °C COVID-19 cases dropped 11%–22%. Casanova et al. (2010) reported that coronaviruses last longer on non-living objects in low temperatures compared to higher temperatures. Though a few studies (Ma et al., 2020; Demongeot et al., 2020; Iqbal et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; To et al., 2021) reported ‘uncertain’ or ‘no relationship’ between COVID-19 spread with temperature and humidity, overall, great homogeneity was observed among statistical results, hence, we maintain our position that lower temperature favours the growth and spread of the virus while increasing temperatures inhibit the growth and spread of the virus.

With a parallel comparison with SARS-CoV-1 and MERS, as well as considering existential limitations to fully encompass the influence of socio-cultural factors such as containment measures, local health policies, government responses, population density, cultural aspects which have not been fully included to maximum unit of influence, this study however cannot wholly associate the spread of the virus to climatic weather variables alone. Based on comparative statistical analysis of infections rates done on the three climate zones of study (Africa, China and South America), and comparing their government responses vis-a-vis viral infection rates, we agree with Oliveiros et al. (2020) that though temperature and humidity contribute significantly to the spread of the virus, other atmospheric conditions and socio-cultural factors including government responses, general health policies, population density and transportation also contribute to the spread of the virus. Studies done in China by Al-Rousan and Al-Najjar (2020), Bhattacharjee (2020), Bypass (2020), Han et al. (2020), Ma et al. (2020), Chen et al. (2019) suggests that a major part of China's success story is attributed to effective response mechanisms popular with actual lockdown and the wearing of mask. We recommend the international community to return to effective social distancing, isolation of infected persons and the effective wearing of mask.

To further put our arguments in a proper demonstrably context, we can say, for example, that though South Africa (a cooler climate country comparative to Ghana) is recording higher cases than Ghana (a hotter climate country), the higher cases in South Africa are not necessarily resulted from the cooler climate there but could result from other factors. Higher number of tourists received across South Africa, Egypt, Brazil and India could contribute to increased incidence rates in these countries (Babuna et al., 2020). Similarly, the present second wave of recorded cases in Europe cannot solely be blamed on the approaching winter without considering increased person to person contact during the past summer holidays. Consequently, this study asserts that socio-cultural variables are also significant factors as meteorological variables. We hence encourage various countries to augment their public health interventions to contain viral spread at manageable levels while the world awaits the discovery of a vaccine. It is only with proper planning and adherence to safety protocols that unnecessary damage could be averted.

Other studies discussed another hypothesis to explain the recorded lower infection cases in some tropical countries, especially, in Africa and parts of South America (Bukhari and Jameel, 2020). Bukhari and Jameel (2020) argued that less mass testing in underdeveloped countries as a result of weaker health care systems could be the reason for lower recorded cases. Though this argument seems rational, lower number of death cases recorded in these underdeveloped countries does not support this hypothesis. Tropical zones especially sub-Saharan African countries recorded some of the lowest death rates and higher recovery rates. As a result, we recommend immunology studies on covid-19 survivors in the near future.

The findings of this study have policy implications for preventing the spread of the virus. The present ongoing second wave should be taken seriously. Having gone through the first wave, humanity is in a better position to reduce infections if proper safety protocols are adhered. The practice of social distancing; staying home; applying 70% alcohol-based sanitizer; avoiding handshakes; using face masks; handwashing with soap and running water, will help reduce the spread of the virus.

4.1. Limitations of the study

This study could not include other meteorological variables such as air pressure, ultraviolet, wind speed, atmospheric particles, and only discussed social factors such as government response and migration from observational knowledge. The inclusion of such factors would have provided a higher level of accuracy. Data especially on meteorological factors was hard to get for some African countries.

5. Conclusion

To determine the correct position on the current debate on impact of temperature and humidity on the viral spread of COVID-19, we tested three climate zones including Africa, South America and Mainland China using daily data from January to August 2020. Based on sufficient evidence, we found that temperature and humidity correlate negatively with spread of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 dies under very high temperatures but that alone is not a sufficient factor to explain the slow spread of the virus in some lower temperature climates. With greater influence from socio-cultural factors including public health interventions, local culture and transport, countries must attach more seriousness to implementing safety protocols. Countries could take a cue from China and other countries who implemented strict lockdown of cities and provinces, limiting the movement of people and closing down borders until such a time an efficient vaccine is discovered for entire global vaccination.

It takes the strong collaboration of various units, and discipline from people to manage COVID-19 below pandemic. Future research should investigate immunological aspects, age of population, herd immunity, migration patterns, population density and socio-cultural dynamics. Furthermore, the impact of humidity and temperature on the rate of quantitative and qualitative progression of the pandemic should be estimated, especially in the advent of the arrival of the second wave particularly in Europe and the northern hemisphere.

Author contribution

Pius Babuna and Chuanliang Han: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation; Visualization, Writing - review & editing. Meijia Li, Doris Awudi, Roberto Xavier Supe Tulcan, Amatus Gyilbag, Bian Dehui. Writing - review & editing, Data curation. Xiaohua Yang. Conceptualisation, Review and Funding. Saini Yang. Conceptualisation Review and Funding. Declaration of competing interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding sources supporting the work

This research was funded by the National Key Research Program of China (grant numbers. 2017YFC0506603, 2016YFC0401305), the State Key Program of National Natural Science of China (grant number. 41530635) and the Project of National Natural Foundation of China (grant number. 51679007) and also supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1508903), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41621061), and the International Centre for Collaborative Research on Disaster Risk Reduction (ICCR-DRR).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111106.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Appendix 1: List of selected countries for the study. Appendix 2: Intrinsic growth cases of African countries. Appendix 3: Relationship between dynamics of epidemic and environment indexes for mainland China. Appendix 4: Relationship between dynamics of epidemic and environment indices for China, Ghana and Argentina.

References

- Ahmadi M., Sharifi A., Dorosti S., Ghoushchi S.J., Ghanbari N. Investigation of Effective climatology parameters on COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138705. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rousan N., Al-Najjar H. Nowcasting and forecasting the spreading of novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV and its association with weather variables in 30 Chinese provinces: a case study. 2020. SSRN. [DOI]

- Araujo M.B., Naimi B. 2020. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus Likely to Be Constrained by Climate.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.12.20034728v1.full.pdf MedRxiv: 20034728v1 [Preprint]. 2020 [cited 2020 October 24] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K., Kagi N., Kim H., Hayashi M. Impact of climate and ambient air pollution on the epidemic growth during COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Environ. Res. 2020;190:110042. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babuna P., Xiaohua Y., Gyilbag A., Awudi A.D., Ngmenbelle D., Dehui B. Impact of COVID-19 on the insurance industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:5766. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister-Tyrrell M., Meyer A., Faverjon C., Cameron A. 2020. Preliminary Evidence that Higher Temperatures Are Associated with Lower Incidence of COVID-19, for Cases Reported Globally up to 29th February 2020.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.18.20036731v1 MedRxiv: 20036731v1 [Preprint]. 2020 [cited 2020 October 24]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Ma B.J., Bilal, et al. Correlation between environmental pollution indicators and COVID-19 pandemic: a brief study in Californian context. Environ. Res. 2020;187 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S. arXiv: 2003.11277v1 [Preprint]; 2020. Statistical Investigation of Relationship between Spread of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and Environmental Factors Based on Study of Four Mostly Affected Places of China and Five Mostly Affected Places of Italy.https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.11277 [cited 2020 March 24]-2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biktasheva I.V. Science of the Total Environment; Forthcoming: 2020. Role of a Habitat's Air Humidity in COVID-19 Mortality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briz-Redon A., Serrano-Aroca A. A spatio-temporal analysis for exploring the effect of temperature on COVID-19 early evolution in Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138811. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari Q., Jameel Y. Will coronavirus pandemic diminish by summer? SRRN. [Preprint] 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3558757 [cited 2020 March 24]. Available from:

- Bypass P. Eco-epidemiological assessment of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, January-February 2020. Glob. Health Action. 2020;13(1):1760490. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1760490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova L.M., Jeon S., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Effects of air temperature and relative humidity on coronavirus survival on surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:2712–2717. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02291-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCDC (Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention) CCDC; Beijing: 2020. The Latest Situation of COVID-19.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202003/9d462194284840ad96ce75e b8e4c8039.shtml (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.H., Peiris J.S.M., Lam S.Y., Poon L.L.M., Yuen K.Y., Seto W.H. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011;2011:734690. doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Fu B., Xia J., Wu D., Wu S., Zhang Y., Sun H., Liu Y., Fang X., Qin B., Li X., Zhang T., Liu B., Dong Z., Hou S., Tian L., Xu B., Dong G., Zheng J., Yang W., Wang X., Li Z. Major advances in studies of the physical geography and living environment of China during the past 70 years and future prospects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019;62(11):1665–1701. doi: 10.1007/s11430-019-9522-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138474. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. How high wind speed can reduce negative effects of confirmed cases and total deaths of COVID-19 infection in society. Working Paper CocciaLab. 2020;52:1–20. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3603380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demongeot J., Flet-Berliac Y., Seligmann H. Temperature decreases spread parameters of the new Covid-19 case dynamics. Biology. 2020;9:5. doi: 10.3390/biology9050094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagbo S.F., Garbati M.A., Hasan R. Acute viral respiratory infections among children in MERS-endemic Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2012–2013. J. Med. Virol. 2017;89(2):195–201. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattorini D., Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020;264 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groulx N., Urch B., Duchaine C., Mubareka S., Scott J.A. The Pollution Particulate Concentrator (PoPCon): a platform to investigate the effects of particulate air pollutants on viral infectivity. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;628–629:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthe S.S., Swain B., Patra S.S., Amte A. On the global trends and spread of the COVID-19 outbreak: preliminary assessment of the potential relation between location-specific temperature and UV index. J. Public Health: Theor. Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01279y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D. 2020. Effect of Ambient Temperature on COVID-19 Infection Rate.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3558470 SRRN. [Preprint]. [cited 2020 Oct 24] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Liu Y., Tang J., Yuyao Zhu Y., Jaeger C., Yang S. Lessons from the mainland of China's epidemic experience in the first phase about the growth rules of infected and recovered cases of COVID-19 worldwide. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020;11(2020):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s13753-020-00294-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Li M., Haihambo N., Babuna P., Liu Q., Zhao X., Jaeger C., Li Y., Yang S. Mechanisms of recurrent outbreak of COVID-19: a model-based study. Nonlinear Dynam. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11071-021-06371-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque S.E., Rahman M. Association between temperature, humidity, and COVID-19 outbreaks in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2020;114:253–255. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Guan P., Zhou B. Fitness of morbidity and discussion of epidemic characteristics of SARS based on logistic models. Chin. J. Public Health. 2003;19(6):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N., Fareed Z., Shahzad F., He X., Shahzad U., Lina M. The nexus between COVID-19, temperature and exchange rate in Wuhan city: new findings from partial and multiple wavelet coherence. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138916. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Wu X.J., Guan Y.J. Effect of ambient air pollutants and meteorological variables on COVID-19 incidence. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattabi E., Zouini M., Jamil M. SRRN; 2020. The Thermal Constituting of the Air Provoking the Spread of (COVID-19) [Preprint]. 2020 [cited 2020 March 24] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lauren G. John Hopkins University; 2020. Centre for Systems Science and Engineering at.https://buff.ly/2O69IR8 blog Post. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhou J., Yao J., Zhang X., Li L., Xu X., He X., Wang B., Fu S., Niu T., Yan J., Shi Y., Ren X., Niu J., Zhu W., Li S., Luo B., Zhang K. Impact of meteorological factors on the COVID-19 transmission: a multi-city study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;726:138513. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowen A.C., Mubareka S., Steel J., Palese P. Influenza virus transmission is dependent on relative humidity and temperature. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(10):1470–1476. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W., Majumder M.S., Liu D. 2020. The Role of Absolute Humidity on Transmission Rates of the COVID-19 Outbreak.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.12.20022467v1 MedRxiv: 20022467v1. [Cited 2020 Oct 24] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Zhao Y., Liu J. Effects of temperature variation and humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;724:138226. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari Harmooshi N., Shirbandi K., Rahim F. Environmental concern regarding the effect of humidity and temperature on SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) survival: fact or fiction. SSRN. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09733-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveiros B., Caramelo L., Ferreira N.C., Caramelo F. MedRxiv: 20031872v1 [Preprint]; 2020. Role of Temperature and Humidity in the Modulation of the Doubling Time of COVID-19 Cases.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.05.20031872v1 [Cited 2020 Oct 24] [Google Scholar]

- Otter J., Donskey C., Yezli S., Douthwaite S., Goldenberg S., Weber D. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;92:235–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier C., Luo W., Majumder M. SRRN. [Preprint]; 2020. The Role of Environmental Factors on Transmission Rates of the COVID-19 Outbreak: an Initial Assessment in Two Spatial Scales. [Cited 2020 Oct 24] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prata D.N., Rodrigues W., Bermejo P.H. Temperature significantly changes COVID-19 transmission in (sub) tropical cities of Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138862. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Xiao S., Shi R., Ward M.P., Chen Y., Tu W., Su Q., Wang W., Wang X., Zhang Z. COVID-19 transmission in Mainland China is associated with temperature and humidity: a time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138778. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi N.R., Fouladi-Fard R., Aali R., Shahryari A., Rezaali M., Ghafouri Y., Ghalhari M.R., Asad-Ghalhari M., Farzinnia B., Gea O.C., Fiore M. Environ. Res. 2021;194:110692. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding W., Atkinson M., Cunningham A., Lacono G., Moses L., Wood J., Jones K. Impacts of environmental and socio-economic factors on emergence and epidemic potential of Ebola in Africa. Nat. Commun. 2020;10:4531. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12499-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario D.K.A., Mutz Y.S., Bernardes P.C., Conte-Junior C.A. Relationship between COVID-19 and weather: case study in the tropical country. IJHEH. 2020;229 doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., Kar S. medRxiv; 2020. Nature of Transmission of Covid19 in India. [Google Scholar]

- Sajadi M., Habibzadeh P., Vintzileos A., Shokouhi S., Miralles-Wilhelm F., Amoroso A. SRRN. [Preprint]; 2020. Temperature, Humidity and Latitude Analysis to Predict Potential Spread and Seasonality for COVID-19. [Cited 2020 March 24] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkodie A.S., Owusu A.P. Impact of meteorological factors on COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from top 20 countries with confirmed cases. Environ. Res. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P., Dong Y., Yan H. MedRxiv: 20025791v1 [Preprint]; 2020. The Impact of Temperature and Absolute Humidity on the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak—Evidence from China.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.22.20038919v1 [cited 2020 March 24] [Google Scholar]

- Sizun J., Yu M.W.N., Talbot P.J. Survival of human coronaviruses 229E and OC43 in suspension and after drying on surfaces: a possible source of hospital acquired infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 2000;46:55–60. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobral M.F.F., Duarte G.B., da Penha Sobral A.I.G., Marinho M.L.M., de Souza Melo A. Association between climate variables and global transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138997. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To T., Zhang k., Maguire B., Terebessy E., Fong I., Parikhc S., Zhu J. Correlation of ambient temperature and COVID-19 incidence in Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;750:141484. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosepu R., Gunawan J., Effendy D.S., et al. Correlation between weather and covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;725:138436. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travaglio M., Popovic R., Yu Y., Leal N., Martins L.M. medRxiv; 2020. Links between Air Pollution and COVID-19 in England. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., de Wit E., Munster V.J. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu X. The compound Logistic model used to describe epidemic situation dynamics of SARS in Beijing. J. China Jiliang Univ. 2005;16(2):159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Liu J., Fu S., Xu X., Li L., Ma Y., Zhou J., Yao J., Liu X., Zhang X. medRxiv; 2020. An Effect Assessment of Airborne Particulate Matter Pollution on COVID-19: A Multi-City Study in China. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Tang K., Feng K., Lv W. 2020. High Temperature and High Humidity Reduce the Transmission of COVID-19. Available at: SSRN 3551767. [Google Scholar]

- Wei M., Liu H., Chen J., Xu C., Li J., Xu P., Sun Z. Effects of aerosol pollution on PM2.5-associated bacteria in typical inland and coastal cities of northern China during the winter heating season. Environ. Pollut. 2020;262:114188. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Implications for Infection Prevention Precautions. Scientific Brief on 9 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Jing W., Liu J. Effects of temperature and humidity on the daily new cases and new deaths of COVID-19 in 166 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:139051. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Zhu Y. Association between ambient temperature and COVID-19 infection in 122 cities from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;724:138201. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R., Rahmandad H., Gupta M., Digennaro C., Ghaffarzadegan N., Amini H., Jalali M. 2020. Weather conditions and COVID-19 transmission: estimates and projections. Available at: SSRN 3593879. [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Li H., Cao Y. Influnce of meteorological factors on the COVID-19 transmission with the season and geographic location. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;18(2):484. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020484. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yongjian Z., Jingu X., Fengming H., Liqing C. Association between short-term exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 infection: evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138704. 138704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Li X., Wang M., Chen H., Yao M. Microbial aerosol chemistry characteristics in highly polluted air. Sci. China Chem. 2019;62:1051–1063. doi: 10.1007/s11426-019-9488-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Li X., Liu F., Zhu Gaofeng, Ma C., Wang L. Prediction of COVID-19 spread in African countries and the implications for prevention and control: a case study in South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, Senegal and Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Xie J., Huang F., Cao L. Association between short-term exposure to air Pollution and COVID-19 infection: evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;727:138704. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: List of selected countries for the study. Appendix 2: Intrinsic growth cases of African countries. Appendix 3: Relationship between dynamics of epidemic and environment indexes for mainland China. Appendix 4: Relationship between dynamics of epidemic and environment indices for China, Ghana and Argentina.