Abstract

Background

The complexity of disease- and treatment-related symptoms causes profound distress and deterioration of health-related quality of life among patients with brain tumors. Currently, there is no Danish validated disease-specific instrument that focuses solely on measures of both neurologic and cancer-related symptoms of patients with brain tumors. The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module (MDASI-BT) is a validated patient self-report questionnaire that measures symptom prevalence, intensity, and interference with daily life. The aim of the present study was to determine the psychometric validity of the Danish translation of the MDASI-BT, and to test its utility in 3 cohorts of Danish patients across the spectrum of the brain cancer disease and treatment trajectory.

Methods

A linguistic validation process was conducted. Danish patients with malignant primary brain tumors were included to establish the psychometric validity and reliability of the Danish MDASI-BT. Cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted to support the psychometric properties.

Results

A total of 120 patients participated in this study. Coefficient αs for the symptom and interference subscales indicate a high level of reliability across all items. Corresponding symptom and interference or functional items and subscales in the MDASI-BT and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor Module BN20 were significantly correlated. Cognitive debriefing provided evidence for content validity and questionnaire utility as participants were comfortable answering the questions and had no problem with the understandability or number of questions asked.

Conclusion

The MDASI-BT is a simple, concise symptom assessment tool useful for assessing the symptom severity and interference of Danish-speaking patients with brain cancer.

Keywords: brain tumor, cognitive debriefing, concurrent validity, psychometric validity, The MD Anderson Symptom inventory

There are more than 100 different types of primary brain and other CNS tumors registered worldwide.1 In Denmark, 1500 newly diagnosed patients with neoplasms in the brain, meninges, and cranial nerves were registered in the Danish Neuro-oncology Registry in 2014.2 These tumors are heterogeneous in their histological typing and molecular alterations and thereby classified accordingly.3 The most commonly occurring brain tumor types are meningioma (37%), gliomas (25%), pituitary tumors (16%), and nerve sheath tumors (8%).4 It is common for all types of brain tumors to cause a range of symptoms depending on the specific location in the brain and increased intracranial pressure caused by tumor burden. The cerebral symptoms that may occur include global cerebral symptoms (fatigue, nausea, headache, confusion); focal complications (hemiparesis, seizures, speech difficulties); neurocognitive deficits (aphasia, impaired attention, concentration difficulties, reduced short-term memory, personality changes); and emotional symptoms such as depression and anxiety.5,6 Furthermore, comorbidities emerge from surgery and side effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Steroids, which are commonly prescribed, cause significant side effects with prolonged use and may lead to hyperglycemia, increased blood pressure, depression, Cushing syndrome, insomnia, gastric disturbances, osteoporosis, and loss of muscle strength.7,8 Immobility and release of vasoactive molecules from glioma cells can result in thromboembolic events. This complexity of symptoms and complications causes profound distress and deterioration of health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Antineoplastic treatment aims to achieve progression-free survival with delayed neurological and cognitive deterioration and to maintain or improve HRQOL. It is imperative to identify and understand the elements that contribute to the improvement of HRQOL. Known contributory factors that effect HRQOL in patients with high-grade glioma are sex, tumor localization, histological classification, neurocognitive function, and symptom burden.6,9,10

Valid and reliable disease-specific symptom assessment tools are important to ensure effective management of symptoms. Several brain tumor symptom assessment tools exist internationally11; however, Denmark does not currently have a validated disease-specific instrument that focuses on the symptom status of patients with brain tumors. Although the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire and brain tumor module (EORTC QLQ-BN20)12 is translated for use in Danish-speaking populations, it is a measure of quality of life (QOL), not of symptom burden, and may not be optimal for capturing symptom-related data for use in routine clinical care. The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) is a brief patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure of symptom burden common to all cancer types.13–23 As a measure of symptom burden, a domain of QOL, items on the MDASI measure the severity and functional interference of those symptoms most relevant to cancer patients. The core MDASI has been validated for use in multiple cancer diagnoses; and additional symptoms unique to a particular cancer site, cancer type, or cancer therapy can be added to the core symptoms to produce disease- and treatment-specific modules.21–30 The MDASI Brain Tumor module (MDASI-BT) is a validated patient self-report questionnaire that measures symptom prevalence, severity, and interference with daily life in patients with brain tumors.15,24 The MDASI-BT consists of 13 core MDASI symptom severity items, 9 brain tumor-specific symptom severity items, and 6 symptom interference items. The MDASI is comprehensive but brief enough to avoid being a burden to the user,25 and differs from other instruments in it was designed to assess the symptom experience,16 whereas other instruments have been developed to measure HRQOL. Several other advantages of MDASI include that the level of symptom interference with daily functioning also is measured, it has a user-friendly format, it is easy to translate into other languages, and is adaptable for a variety of digital devices.25 Other instruments have a recall period of 1 week in the rating; however, MDASI-BT measures the last 24 hours because there is concern regarding the reliability of a longer recall of symptoms.15,24 Hence, PRO using the MDASI-BT instrument allows timely intervention in response to current symptom experience, supporting better health outcomes. Patient responses to individual symptom severity and symptom interference items are easily interpreted in the clinical setting. The validation of a Danish version of MDASI-BT will not only assist future research but will also facilitate dialogue between patients and clinicians to ensure optimal symptom assessment and management. The aim of the present study was to determine the psychometric validity of the Danish translation of the MDASI-BT and to test its utility in 3 cohorts of Danish patients across the spectrum of brain cancer disease and the treatment trajectory.

Methods

Study Participants

Eligibility criteria included age 18 years or older, the ability to speak and understand Danish, and a pathological verified diagnosis of brain tumor. Patients diagnosed with meningioma and pituitary tumors, patients who were undergoing a current treatment for another cancer disease, and patients with cognitive impairment that would prohibit ability to respond to the questionnaire as judged by their clinician were excluded. A total of 120 Danish patients with intra-axial primary brain tumor were included. All of these patients were referred to, receiving, or in follow-up after the Stupp regimen: concomitant chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant maintenance chemotherapy.26

To better describe the symptom burden of brain cancer patients, we sampled patients who were receiving different treatments and in various stages of disease. Three patient cohorts were included in the psychometric evaluation of the Danish MDASI-BT module. Cohort A comprised brain tumor patients (n = 64) enrolled 1 to 2 weeks following the initial neurosurgical intervention. Cohort A were divided into patients with a KPS of greater than or equal to 80 (n = 52) and patients with a KPS of less than 80 (n = 12). Cohort B consisted of brain tumor patients (n = 41) undergoing oncological treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy divided into those with a KPS greater than or equal to 80 (n = 29) or a KPS of less than 80 (n = 12). Cohort B members were recruited after having received 4 to 5 weeks of treatment with 4 patients recruited 4 months after treatment start. Cohort C (n = 15) consisted of patients who had been diagnosed for 6 months to 4 years who had completed standard therapy.

Study Procedures

Project nurses at the neurosurgical department (cohort A) or at the neuro-oncological outpatient clinic (cohorts B and C) approached potential participants for recruitment. All participants provided written consent to participate prior to the start of data collection. This study is registered by the Danish Data Protection Agency (No 2007-58-0015, 30–1018). Participants completed the Danish version of MDASI-BT and the EORTC QLQ-BN2012 at baseline. An investigator clinician checklist for demographics, the Charlson Comorbidity Index,27 and clinical information was completed at baseline based on the medical journal and electronic patient system OPUS.

Measures

The MDASI-BT assesses 13 core cancer-related symptoms: pain, fatigue, nausea, disturbed sleep, distress, shortness of breath, difficulty remembering, lack of appetite, drowsiness, dry mouth, sadness, vomiting, and numbness or tingling, and 9 brain tumor–specific symptoms: difficulty concentrating, irritability, difficulty speaking, change in appearance, weakness, difficulty understanding, change in vision, change in bowel patterns, and seizures. Symptom severity at its worst in the last 24 hours is rated on a 0 to 10 scale (0 “not present” and 10 “as bad as you can imagine”). The symptom items are further categorized into 6 symptom factors: Affective (distress, fatigue, sleep, sad, and irritable), Cognitive (difficulty understanding, difficulty remembering, difficulty speaking, and difficulty concentrating), Neurologic (seizures, numbness, pain, and weakness), Treatment-related (dry mouth, drowsiness, and lack of appetite), General Disease (change in appearance, change in vision, change in bowel patterns, and shortness of breath), and Gastrointestinal (nausea and vomiting), with a score provided for overall symptoms, factors, and interference and its subscales. Six interference items assessing symptom-related interference with general activity, mood, work (including work around the house), relations with other people, walking, and enjoyment of life are scored on a 0 to 10 scale (0 “did not interfere” and 10 “interfered completely”) over the past 24 hours. The interference items are further categorized into 2 subscales: Mood-Related (REM) (relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood) and Activity-Related (WAW): walking, general activity, and work. The MDASI-BT was derived originally using factor analysis with a cohort of brain tumor patients, the majority of whom had received surgery alone as treatment.13 The MDASI-BT has established criterion, content, and discriminant validity, and reliability, as well as sensitivity for patients with recurrent tumor vs stable disease.15

In 2012, the MDASI-BT was translated to Danish using the “forward-backward” translation process. The MDASI-BT was translated into Danish from the original English language using a multistep forward-backward translation method, which required collaboration between 10 health care professionals (physicians, psychologists, nurses, and physiotherapists) and 3 native Danish translators (A.L., B.K., K.B.) who were fluent in English. To avoid dialectical differences, items from the English version of the MDASI were translated using simple terms, and nonidiomatic expressions. Another bilingual professional (M.J.) translated the resulting Danish version back into English. Comparison between the original and the back translation then followed. This process was repeated until agreement on each of the 19 items was reached.

The EORTC QLQ-BN20 is one of the most frequently used self-rating questionnaires to assess QOL in patients with brain cancer. It consists of 30 items and 5 multi-item function subscales plus global health status/QOL subscales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social function), 4 multiitem symptom subscales (fatigue, pain, nausea, and vomiting), and 6 separate items to assess symptoms (dyspnea, sleep disturbance, appetite loss, diarrhea, and constipation) and financial impact. The EORTC QLQ-BN20 has established reliability and validity for assessing symptoms and QOL in patients with primary brain tumors.12

Cognitive Debriefing Interviews

Cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted with a subset of participants (n = 20) from cohort A to establish the understandability and usability of the Danish MDASI-BT. After participants completed the MDASI-BT at baseline, a project nurse asked questions related to the use and relevance of the instrument items, the ease of responding to the items, and the comprehensibility and clarity of the items in individual interviews. Participants were given a blank version of the MDASI-BT as a reference while the questions were asked. Participant responses were noted on a cognitive debriefing questionnaire developed specifically for the MDASI.28

Participants answered whether they were comfortable answering the questions, whether they had suggestions for making the items more comfortable to answer, whether any of the symptom items seemed repetitive, and which, if any, redundant items might be deleted. In addition, participants were asked whether the scoring system (0-10 numeric scale) was easy to use and understand, to verify the relevance of the brain tumor-specific items, and whether any other important symptoms had not been included in the questionnaire.

Analysis

Sample size was primarily based on the ability of the MDASI-BT to distinguish between patients with good (KPS ≥ 80) and poor (KPS < 80) performance status as a measure of known-group validity. Our sample size allowed for detection of a half SD difference in symptom severity between these 2 groups of patients.16 The half SD criterion has been shown to be a reasonable and meaningful difference.31 With 120 patients and assuming equal size group, we should be able to detect an effect size difference of 0.5 or about a 0.75 point difference (SD of 1.5 based on prior study) on a 0 to 10 scale on the average symptom subscale (all symptom items) scores between the groups using a 2-tailed with a significance level of .05 and 80% power.

Sociodemographic and disease characteristics were analyzed descriptively across cohorts. The prevalence and mean severity of symptoms were analyzed descriptively.

Reliability was evaluated by calculating the Cronbach α coefficient, which is a measure of the internal consistency of responses to a group of items. The Cronbach α ranges from 0 to 1.0, with higher values indicating greater consistency.

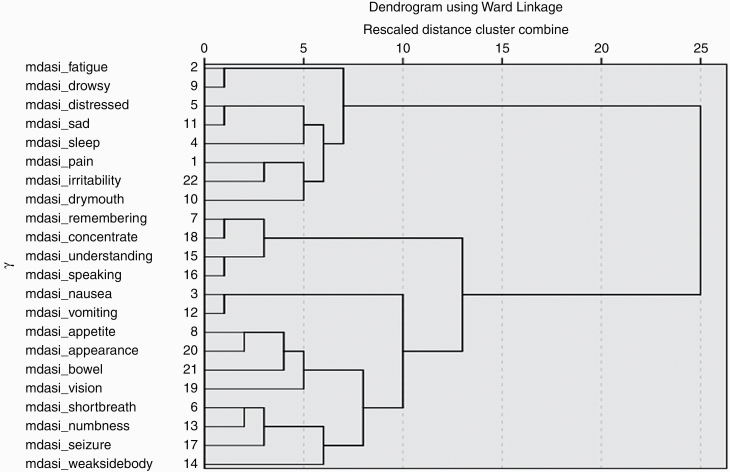

To better understand how the symptom items are interrelated, we performed hierarchical clustering analysis. This type of clustering algorithm groups symptoms that are perceived by patients to be similar in a progressive manner until all symptoms form a single hierarchy. Clusters were formed using the Ward method, whereas distances between symptoms were calculated using squared Euclidian distances. The results of this analysis are presented as a dendrogram.

Known-group validity was examined by comparing Danish MDASI-BT scores among participants with differing performance status ratings. Patient groups with poor KPS were expected to have the highest symptom scores.

Concurrent validity was evaluated by calculating Pearson correlations between the overall Danish MDASI-BT and the EORTC QLQ-BN20 scores. We hypothesized that the following pairs of questions would significantly correspond (Danish MDASI-BT score EORTC score): all items-global health status/QOL, WAW-physical functioning (WAW: walking, general activity, and work), REM-role functioning (REM: relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood), affective-emotional functioning, cognitive-cognitive functioning, fatigue-fatigue, gastrointestinal-nausea and vomiting, pain-pain, shortness of breath-dyspnea, sleep disturbance-insomnia, lack of appetite-appetite loss, bowel-constipation, bowel-diarrhea, change in vision-visual disorder, difficulty speaking-communication deficit, pain-headaches, seizures-seizures, drowsiness-drowsiness, change in appearance-hair loss, and weakness-weakness of legs. We categorized symptoms as moderate (ratings of 5 or greater) and severe (ratings of 7 or greater) based on previous work with pain and fatigue.

All P values reported are 2-tailed with an α level of .05. All statistical procedures were performed using the IBM SPSS statistical software program for Windows (version 24, IBM SPSS Inc).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Sociodemographic and disease characteristics for the 3 cohorts are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Cohorts (n = 120)

| Cohort 1 (n = 64) | Cohort 2 (n = 41) | Cohort 3 (n = 15) | Total (n = 120) | P, overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort description | A | B | C | ||

| Patient characteristics, No. (%) | |||||

| Sex | .049 | ||||

| Men | 47 (73.4%) | 21 (51.2%) | 8 (53.3%) | 76 (64.4%) | |

| Women | 17 (26.6%) | 20 (48.8%) | 7 (46.7%) | 44 (36.7%) | |

| Marital status | .715 | ||||

| Married/Living with partner | 51 (79.7%) | 30 (73.2%) | 12 (80.0%) | 93 (77.5%) | |

| Single/Divorced/Living alone | 13 (20.3%) | 11 (26.8%) | 3 (20.0%) | 27 (22.5%) | |

| KPS score | |||||

| KPS < 80 | 12 (18.8%) | 12 (29.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 29 (24.4%) | |

| KPS ≥ 80 | 52 (81.3%) | 29 (70.7%) | 10 (66.7%) | 90 (75.6%) | |

| Diagnosis | .516 | ||||

| Astrocytoma | 1 (1.6%) | 4 (9.8%) | 2 (13.3%) | 13 (10.8%) | |

| GBM | 50 (78.1%) | 31 (75.6%) | 10 (66.7%) | 91 (75.8%) | |

| Oligodendroglia | 6 (9.4%) | 3 (7.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 12 (10.0%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.6%) | 3 (7.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.3%) | |

| Operation type | .900 | ||||

| Biopsy | 2 (3.1%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.5%) | |

| Craniotomy | 49 (76.6%) | 29 (70.7%) | 13 (86.7%) | 91 (75.8%) | |

| Craniotomy + stereo biopsy | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Stereo biopsy | 10 (15.6%) | 10 (24.4%) | 2 (13.3%) | 22 (18.3%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3.1%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.5%) | |

| Localization | .332 | ||||

| Bilateral | 2 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (2.5%) | |

| Left hemisphere | 29 (45.3%) | 16 (39.0%) | 6 40.0%) | 51 (42.5%) | |

| Right hemisphere | 31 (48.4%) | 19 (46.4%) | 7 (46.7%) | 57 (47.5%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3.1%) | 6 (14.6%) | 1 (6.7%) | 9 (7.5%) | |

| Lobe | .801 | ||||

| Frontal | 24 (37.5%) | 16 (39.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 45 (37.5%) | |

| Occipital | 7 (10.9%) | 6 (14.6%) | 3 (20.0%) | 16 (13.3%) | |

| Parietal | 12 (18.8%) | 3 (7.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 17 (14.2%) | |

| Temporal | 14 (21.9%) | 9 (22.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 27 (22.5%) | |

| Unknown | 7 (10.9%) | 7 (17.1%) | 1 (6.7%) | 15 (12.5%) | |

| Current treatment | .000 | ||||

| XRT + chemotherapy | 7 (10.9%) | 29 (70.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 41 (34.2%) | |

| Chemotherapy only | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (4.2%) | |

| XRT only | 2 (3.1%) | 6 (14.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (6.7%) | |

| Surgery only | 43 (67.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 47 (39.2%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (17.2%) | 6 (14.6%) | 2 (13.3%) | 19 (15.8%) |

Abbreviations: GBM, glioblastoma; XRT, external radiation therapy.

Severity and Prevalence of Multiple Cancer-Related Symptoms

Table 2 presents the 22 MDASI-BT Danish symptom items and 6 MDASI-BT Danish interference items rank-ordered from highest to lowest in terms of mean severity. The mean severity ratings are similar to those achieved in studies in patients with other cancers and in the original validation of the MDASI-BT. The percentages of participants reporting symptoms as moderate and severe, based on this categorization, are also presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for the MDASI-BT Module Test

| MDASI-BT module | Mean | SD | Range | LCL | UCL | % = 0a | % 1-4b | % ≥5c | % ≥7d | % Missinge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core symptoms (rank order) | ||||||||||

| Fatigue | 4.92 | 2.90 | 10 | 4.56 | 5.28 | 8.6 | 30.5 | 60.9 | 39.0 | 0.0 |

| Distress | 4.21 | 2.98 | 10 | 3.84 | 4.58 | 14.3 | 35.2 | 49.6 | 26.9 | 0.01 |

| Drowsiness | 4.01 | 3.18 | 10 | 3.62 | 4.41 | 14.3 | 43.8 | 41.9 | 25.7 | 0.0 |

| Sadness | 3.55 | 3.17 | 10 | 3.16 | 3.94 | 23.8 | 35.2 | 39.0 | 27.6 | 0.02 |

| Sleep disturbance | 3.48 | 3.64 | 10 | 3.05 | 3.91 | 33.3 | 30.5 | 35.3 | 26.7 | 0.01 |

| Problem with remembering things | 3.40 | 2.80 | 9 | 3.05 | 3.75 | 21.9 | 44.8 | 33.4 | 21.0 | 0.0 |

| Dry mouth | 3.03 | 3.11 | 10 | 2.65 | 3.42 | 36.2 | 29.5 | 32.3 | 17.1 | 0.02 |

| Pain | 2.98 | 3.09 | 10 | 2.59 | 3.36 | 32.4 | 34.3 | 33.3 | 19.0 | 0.0 |

| Lack of appetite | 1.90 | 2.87 | 10 | 1.54 | 2.25 | 54.3 | 25.7 | 20.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 |

| Numbness or tingling | 1.70 | 2.52 | 10 | 1.39 | 2.01 | 54.3 | 29.5 | 16.2 | 7.6 | 0.0 |

| Nausea | 1.66 | 3.10 | 10 | 1.27 | 2.04 | 62.9 | 19.0 | 18.1 | 12.4 | 0.0 |

| Shortness of breath | 1.30 | 2.22 | 10 | 1.02 | 1.57 | 62.9 | 27.6 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 0.0 |

| Vomiting | 1.09 | 2.70 | 10 | 0.76 | 1.43 | 78.1 | 6.7 | 14.3 | 9.5 | 0.01 |

| Module items (rank order) | ||||||||||

| Difficulty concentrating | 3.10 | 2.81 | 10 | 2.75 | 3.45 | 24.8 | 47.6 | 25.7 | 13.3 | 0.02 |

| Irritability | 2.91 | 2.71 | 10 | 2.57 | 3.24 | 26.7 | 47.6 | 23.8 | 14.3 | 0.02 |

| Difficulty speaking | 2.59 | 2.94 | 10 | 2.22 | 2.95 | 40.0 | 38.1 | 21.0 | 16.3 | 0.01 |

| Appearance | 2.38 | 2.91 | 10 | 2.02 | 2.74 | 36.2 | 38.1 | 22.8 | 13.3 | 0.03 |

| Weakness | 2.29 | 3.24 | 10 | 1.89 | 2.69 | 52.4 | 20.0 | 27.6 | 19.0 | 0.0 |

| Difficulty understanding | 2.15 | 2.54 | 10 | 1.83 | 2.46 | 41.0 | 41.9 | 15.3 | 8.6 | 0.02 |

| Vision | 2.18 | 2.94 | 10 | 1.82 | 2.55 | 48.6 | 27.6 | 21.0 | 12.4 | 0.03 |

| Change in bowel pattern | 2.09 | 2.70 | 9 | 1.76 | 2.43 | 48.6 | 27.6 | 22.8 | 13.3 | 0.01 |

| Seizures | 0.40 | 1.57 | 8 | 0.21 | 0.60 | 89.5 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 0.03 |

| Interference items (rank order) | ||||||||||

| Work, including housework | 4.77 | 3.76 | 10 | 4.30 | 5.24 | 21.0 | 25.7 | 53.3 | 43.8 | 0.0 |

| General activity | 4.75 | 3.25 | 10 | 4.34 | 5.15 | 14.3 | 32.4 | 52.3 | 37.1 | 0.01 |

| Mood | 3.53 | 2.66 | 10 | 3.20 | 3.86 | 13.3 | 46.7 | 37.1 | 18.1 | 0.03 |

| Relations with other people | 2.71 | 2.95 | 10 | 2.35 | 3.08 | 33.3 | 36.2 | 28.5 | 19.0 | 0.02 |

| Walking | 2.66 | 3.32 | 10 | 2.24 | 3.07 | 43.3 | 28.8 | 27.6 | 19.0 | 0.01 |

| Enjoyment of life | 2.36 | 2.69 | 10 | 2.02 | 2.69 | 33.3 | 41.9 | 22.9 | 12.4 | 0.02 |

| Subscale scores | ||||||||||

| Affective | 3.89 | 2.33 | 9 | 3.47 | 4.31 | |||||

| Cognitive | 2.75 | 2.34 | 10 | 2.32 | 3.17 | |||||

| Focal neurologic deficit | 1.99 | 1.47 | 5.75 | 1.72 | 2.26 | |||||

| Treatment-related | 3.10 | 2.42 | 10 | 2.66 | 3.54 | |||||

| Generalized/disease status | 2.00 | 1.67 | 7 | 1.70 | 2.31 | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | 1.47 | 2.79 | 10 | 0.97 | 1.98 | |||||

| Core items | 2.95 | 1.84 | 7.77 | 2.61 | 3.28 | |||||

| Module items | 2.24 | 1.56 | 7 | 1.96 | 2.52 | |||||

| All symptom items | 2.68 | 1.57 | 7.29 | 2.39 | 2.96 | |||||

| Mean interference (6 items) | 3.64 | 2.47 | 10 | 3.37 | 3.92 | |||||

| Mean WAW (walk-activity-work) | 4.24 | 3.12 | 10 | 3.89 | 4.59 | |||||

| Mean REM (relate-enjoy-mood) | 3.04 | 2.47 | 10 | 2.76 | 3.31 |

Abbreviations: LCL, lower 95% CL; MDASI-BT, The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module; REM-role functioning, relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood; UCL, upper 95% CL; WAW, walking, general activity, and work.

MDASI-BT Constructs/Subscales: Affective (distress, fatigue, disturbed sleep, sadness, irritability); Cognitive (difficulty understanding, problem with remembering things, difficulty speaking, difficulty concentrating); Focal neurologic deficit (seizures, numbness or tingling, pain, weakness). Treatment-related (dry mouth, drowsiness, lack of appetite); generalized/disease status (change in appearance, change in vision, change in bowel patterns, shortness of breath); gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting).

aPercentage of patients scoring at the floor (score = 0 on the 0-10 scale).

bPercentage mild.

cPercentage moderate to severe.

dPercentage severe.

ePercentage of missing data.

Cognitive Debriefing of The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module Danish

Twenty patients who participated in the cognitive debriefing completed the MDASI-BT in an average of 12 minutes. All participants were comfortable answering the questions and had no problem with the understandability or number of questions asked. Three participants preferred that the questionnaire was read aloud by the project nurse because of visual disturbances or headache. Two participants (10% of the cognitive debriefing cohort) suggested that 2 additional items could be added “problems on healing process of the cicatrice” (wound healing) and “being dependent upon another person” (dependency on caregivers). All participants found the number of items and the 0 to 10 numeric scale easy to use and understand and were comfortable using it. One participant wished to be able to elaborate on the symptom experiences with narratives and suggested that the questionnaire be followed by conversation. Three participants found the question “Your fatigue (tiredness) at its worst” and “Your disturbed sleep at its worst” to be repetitive, and 2 participants identified “Your fatigue (tiredness) at its worst” and “Your feeling drowsy (sleepy) at its worst” to be repetitive.

Internal Consistency Reliability of The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module Danish

The αs for the core items (0.834), module items (0.756), all symptom items (0.884), and interference items (0.845) indicate a high level of reliability across all items.

Cluster Analysis

Figure 1 presents the dendrogram from the hierarchical clustering analysis of the MDASI-BT symptoms. At the right side of the figure, all symptoms are grouped together into a single hierarchy. Looking at Figure 1 from left to right, the items are progressively joined together: The items that join with others sooner (more to the left in Figure 1) were rated by patients more similarly than those at the later clusters. For example, Figure 1 shows that the items “difficulty concentrating” and “remembering” joined together early as a cluster as well as the items “difficulty speaking” and “understanding” forming a separate early cluster. These 2 clusters joined together, indicating they are similarly perceived by patients compared to the other symptom clusters.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis With Dendrogram Using Ward’s Method of Clustering and Squared Euclidian Distance as Distance Measure for Core Plus Module Items.

Known-Group Validity of The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module Danish

To test the known-group validity of the MDASI-BT Danish, we used independent samples t tests to compare the MDASI-BT Danish subscale scores (module, all symptom items, mean interference, WAW, and REM) to performance status, as measured by the KPS. Participants were divided into 2 groups based on KPS. Ninety patients (76%) had a good performance status, and 29 patients had a poor performance status. As predicted, there were significant differences in mean symptom severity for the module items, all symptom items, interference items, and interference subscale scores (WAW and REM) (Table 3) between the groups of patients with good and poor performance status.

Table 3.

Known-Group Validity

| MDASI–New module subscale | KPS | No. | Mean | SD | LCL 95% | UCL 95% | P | Cohen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module | Good (KPS ≥ 80) | 90 | 2.04 | 1.48 | 1.73 | 2.35 | .019 | 0.50 |

| Poor (KPS < 80) | 29 | 2.83 | 1.69 | 2.18 | 3.47 | |||

| All symptom items | Good (KPS ≥ 80) | 90 | 2.45 | 1.49 | 2.14 | 2.76 | .005 | 0.59 |

| Poor (KPS < 80) | 29 | 3.38 | 1.65 | 2.76 | 4.01 | |||

| Mean interference | Good (KPS ≥ 80) | 90 | 3.07 | 2.21 | 2.61 | 3.53 | .000 | 1.16 |

| Poor (KPS < 80) | 29 | 5.60 | 2.16 | 4.77 | 6.41 | |||

| WAW | Good (KPS ≥ 80) | 90 | 3.41 | 2.59 | 2.87 | 3.96 | .000 | 1.34 |

| Poor (KPS < 80) | 29 | 7.01 | 2.79 | 5.96 | 8.08 | |||

| REM | Good (KPS ≥ 80) | 90 | 2.71 | 2.29 | 2.24 | 3.19 | .005 | 0.59 |

| Poor (KPS < 80) | 29 | 4.17 | 2.68 | 3.15 | 5.19 |

Abbreviations: LCL, lower 95% CL; MDASI, The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; REM-role functioning, relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood; WAW, walking, general activity, and work; UCL, upper 95% CL.

Independent sample t test or its nonparametric counterpart based on the following grouping variables. Comparison of MDASI–new module symptom and interference subscale scores and KPS scores (n = 119).

Concurrent Validity of The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module Danish

Corresponding symptom and interference items and subscales in the MDASI-BT and the EORTC QLQ-BN20 were significantly correlated. Table 4 presents the correlations between MDASI-BT Danish subscales and items compared with the EORTC QLQ-BN20 subscales scores.

Table 4.

Concurrent Validity of The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Subscales and Items Compared With European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC) 30 and EORTC-Brain Tumor Module N20 Subscale Scores

| MDASI-BT | EORTC-QLQ30 and BN20 | Pearson correlation |

|---|---|---|

| All items | Global Health Status/QOL | –.412 |

| WAW | Physical functioning | –.624 |

| REM | Role functioning | –.318 |

| Affective | Emotional functioning | –.413 |

| Cognitive | Cognitive functioning | –.532 |

| Fatigue item | Fatigue | .576 |

| GI | Nausea and vomiting | .635 |

| Pain | Pain | .462 |

| Shortness of breath | Dyspnea | .396 |

| Sleep disturbance | Insomnia | .427 |

| Lack of appetite | Appetite loss | .508 |

| Change in bowel pattern | Constipation | .431 |

| Change in bowel pattern | Diarrhea | .254 |

| Change in vision | Visual disorder | .488 |

| Difficulty speaking | Communication deficit | .576 |

| Pain | Headaches | .586 |

| Seizures | Seizures | .486 |

| Drowsiness | Drowsiness | .471 |

| Change in Appearance | Hair loss | .283 |

| Weakness | Weakness of legs | .267 |

Abbreviations: EORTC-BN20, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; GI, gastrointestinal; MDASI-BT, The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module; REM–role functioning, relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood; QOL, quality of life; WAW, walking, general activity, and work.

Higher scores in the functioning subscale of the EORTC-BN20 denote better outcome. Hence, the negative correlations. All correlations are significant at P less than .005.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the satisfactory psychometric properties including reliability, known-group validity, and concurrent validity of the MDASI-BT as a patient-reported symptom assessment instrument for use with Danish-speaking patients with brain cancer. It consists of a comprehensive list of symptoms commonly experienced by patients with brain cancer or benign tumor, regardless of disease site or stage. Patients have confirmed that it is acceptable and easy to understand and complete. The MDASI-BT is a valuable tool both for clinical practice and clinical trials to evaluate patient symptom burden, even with frequent assessments.

Similar to the original English-version validation study, the severity of the neurologic symptoms in our sample varied, with ranges up to 10 for most items and with mean symptom severity scores less than 5.13 Results of the cluster analysis confirm the expected relationships among symptom items. We were unable to reproduce the factor structure described in the validation of the original English version of the MDASI-BT,13 but we demonstrate validity for the Danish translation using other methods. The current validation sample is more diverse in terms of disease stage and treatment when compared to the original validation sample, which may explain our inability to reproduce the original factor structure. The validation of the original English version of the MDASI-BT yielded internal consistency values for the subscales found in the factor analysis.13 As such, we cannot make comparisons between the reliability coefficients we report and the originally reported reliability coefficients. The values reported in the present study meet the minimum requirements for acceptable reliability. These reliability coefficients refer to symptom severity and symptom interference that are generally the underlying symptom burden constructs being measured by the MDASI regardless of disease or treatment modules. The initial validation study of the English version of the MDASI-BT reported sensitivity to known variables, including performance status, similar to what we report here.13

This validation study demonstrates concurrent validity presenting correlations between MDASI-BT Danish subscales and items compared with the EORTC QLQ-BN20 subscales scores. The EORTC QLQ-BN20 is a measure of QOL, a construct that is distal from the symptom experience. Although the EORTC QLQ-BN20 does include some symptom items, it is not a measure specific to symptom burden, which is a domain of QOL. Demonstration of correlations between items and subscales on the EORTC QLQ-BN20, a well-established measure of QOL, and the MDASI-BT Danish version strengthens the validity of the MDASI-BT Danish version as a measure of the symptom burden domain.

MDASI-BT is a clinical outcome assessment (COA) tool. According to the US FDA, 4 types of COA measures exists: PRO, clinician-reported outcome, observer-reported, and performance outcome.29 MDASI-BT can be completed directly by the patients and used as a PRO instrument. The MDASI-BT is a brief measure of the symptom burden of brain cancer that is easily interpreted and useful in research and clinical care. It can be transferred to web-based patient portals and gives professionals and patients the flexibility to communicate efficiently in describing symptom severity and daily interference. The reliable identification of prevalent and severe symptoms can result in a timely and coordinated response from health care services and providers.11 The MDASI-BT provides clinicians with clinically actionable PRO data that are relevant in the context of routine clinical care and frequent assessment.

Inclusion of PROs in neuro-oncology clinical care and clinical trials may be useful for characterizing the net clinical benefit of treatment given the substantial symptom burden and impaired functioning in this patient population. There is a core set of priority constructs for high-grade gliomas that the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology–Patient-Reported Outcome (RANO-PRO)30 working group recommends that is instrument agnostic but are covered by the MDASI-BT.32 To secure a broad and holistic approach, it may be relevant to add a patient concerns inventory tool,33 a cognitive functioning assessment scale,34,35 and a daily living questionnaire36 and a QOL questionnaire37,38 to MDASI-BT. Use of multiple measures should be balanced with clinical relevance and patient burden, with appropriate rationale for each measurement interval. For example, the MDASI-BT may be used more frequently to assess and manage symptoms, whereas additional questionnaires could be used periodically to give a broader picture of the patient experience. Although routine PRO symptom assessment and response may improve survival rates in advanced cancer patients receiving systemic therapy,39 evidence is needed to determine whether routine PRO symptom assessment may improve survival in brain tumor patients specifically. Considerations around patient burden and associated distress should be considered in implementing routine monitoring of patients using PRO measures. Patients may consider frequent assessment of symptoms that are not prevalent to be unnecessary.40 In addition, there is the potential for increased awareness of problems patients may not have identified previously and concern with becoming familiar with the risk of having future symptomatology.40 Evidence of the potential benefits and challenges associated with routine PRO monitoring, including the potential for missing data and response shift, is needed.

Although congruence between patients and proxies has been identified,41 it is of central interest to capture the perspective of caregivers and to provide evidence of the potential for caregiver proxy when patients are unable to provide PRO data. This is of particular importance in brain cancer, during which patients may experience cognitive impairment that may limit the ability to complete frequent and accurate assessment.

Study Limitations

This study has limitations. First, our study participants were recruited from a single university hospital; however, the 3 cohorts were identified at 2 different departments reflecting a representation of brain tumor patients across the brain cancer trajectory. Second, only participants from cohort A (initial trajectory) were recruited for providing cognitive debriefing. Late-stage patients (up to 4 years) may experience symptoms that hinder their use of a PRO questionnaire, although patients with a KPS of less than 80 were recruited across the spectrum of the brain cancer disease and treatment trajectory.

Conclusion

The Danish MDASI-BT is a simple, concise symptom burden assessment tool that is validated to be useful for assessing the symptom status of Danish-speaking patients with brain cancer. Our study demonstrates that the MDASI-BT is a useful instrument for tracking commonly experienced symptoms in Danish-speaking patients undergoing surgical and oncological treatment regimens.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the project nurses who enrolled study participants; Pernille Vinding, Louise Nygreen Christiansen, Pernille Rasmussen, Charlotte Frehr, Carina Kjeldsgård, Sanne Diget, Mie Juul Madsen, and Karolina Kofoed. Finally, we thank Bente Kronborg, Anders Larsen, and Kira Bloomquist, University Hospitals Center for Health Research at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark, for back-translation of the Danish version of MDASI-BT.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from The Center for Integrated Rehabilitation of Cancer Patients [CIRE], established by The Danish Cancer Society and The Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF10SA1016530); from The Neuro Centre at the University Hospital of Copenhagen; The Novo Nordisk Foundation for Clinical Nursing Research; The Capital Regional Research Foundation in Denmark; the Torben and Alice Frimodts Foundation; the Vera and Flemming Westerbergs Foundation; Hetland Olsen’s Foundation; and The Research Foundation at the University Hospital of Copenhagen.

Conflict of interest statement. The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory and its derivative versions are copyrighted and licensed by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and C.C., who has a financial interest in the MDASI and its derivative versions. All other authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

References

- 1. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(suppl_4):iv1–iv86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hansen S, Nielsen J, Laursen RJ, et al. The Danish Neuro-Oncology Registry: establishment, completeness and validity. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kruchko C, Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, et al. The CBTRUS story: providing accurate population-based statistics on brain and other central nervous system tumors for everyone. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(3):295–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rooney AG, Brown PD, Reijneveld JC, et al. Depression in glioma: a primer for clinicians and researchers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Piil K, Jakobsen J, Christensen KB, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade gliomas: a quantitative longitudinal study. J Neurooncol. 2015;124(2):185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hempen C, Weiss E, Hess CF. Dexamethasone treatment in patients with brain metastases and primary brain tumors: do the benefits outweigh the side-effects? Support Care Cancer. 2002;10(4):322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Horber FF, Hoopeler H, Scheidegger JR, et al. Impact of physical training on the ultrastructure of midthigh muscle in normal subjects and in patients treated with glucocorticoids. J Clin Invest. 1987;79(4):1181–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piil K, Jakobsen J, Christensen KB, et al. Needs and preferences among patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers—a longitudinal mixed methods study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(2):e12806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng JX, Zhang X, Liu BL. Health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(1):41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piil K, Rosenlund L. Holistic need assessment and care planning. In: Oberg I, ed. Management of Adult Glioma in Nursing Practice. Switzerland: Springer; 2019: 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taphoorn MJ, Claassens L, Aaronson NK, et al. An international validation study of the EORTC brain cancer module (EORTC QLQ-BN20) for assessing health-related quality of life and symptoms in brain cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2010;46(6):1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cleeland CS. Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient-reported outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2007;(37):16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Armstrong TS, Gning I, Mendoza TR, et al. Reliability and validity of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory-Spine Tumor Module. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(4):421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Armstrong TS, Mendoza T, Gning I, et al. Validation of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module (MDASI-BT). J Neurooncol. 2006;80(1):27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Lu C, et al. Measuring the symptom burden of lung cancer: the validity and utility of the lung cancer module of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Oncologist. 2011;16(2):217–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sailors MH, Bodurka DC, Gning I, et al. Validating the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) for use in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(2):323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gning I, Trask PC, Mendoza TR, et al. Development and initial validation of the thyroid cancer module of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Oncology. 2009;76(1):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones D, Zhao F, Fisch MJ, et al. The validity and utility of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory in patients with prostate cancer: evidence from the Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns (SOAPP) data from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12(1):41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mendoza TR, Zhao F, Cleeland CS, et al. The validity and utility of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory in patients with breast cancer: evidence from the symptom outcomes and practice patterns data from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13(5):325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Chambers MS, et al. Measuring head and neck cancer symptom burden: the development and validation of the M.D. Anderson symptom inventory, head and neck module. Head Neck. 2007;29(10):923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang XS, Williams LA, Eng C, et al. Validation and application of a module of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory for measuring multiple symptoms in patients with gastrointestinal cancer (the MDASI-GI). Cancer. 2010;116(8):2053–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams LA, Whisenant MS, Mendoza TR, et al. Modification of existing patient-reported outcome measures: qualitative development of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory for malignant pleural mesothelioma (MDASI-MPM). Qual Life Res. 2018;27(12):3229–3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kirkova J, Davis MP, Walsh D, et al. Cancer symptom assessment instruments: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1459–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cleeland C. The M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory User Guide. version 1. 2009. https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/MDASI_userguide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arpinelli F, Bamfi F. The FDA guidance for industry on PROs: the point of view of a pharmaceutical company. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dirven L, Armstrong TS, Blakeley JO, et al. Working plan for the use of patient-reported outcome measures in adults with brain tumours: a Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(3):e173–e180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sloan JA, Vargas-Chanes D, Kamath CC, et al. Detecting worms, ducks and elephants: A simple approach for defining clinically relevant effects in quality-of-life measures. J Cancer Integr Med. 2003;1(1):41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Armstrong TS, Dirven L, Arons D, et al. Glioma patient-reported outcome assessment in clinical care and research: a Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology collaborative report. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):e97–e103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rooney AG, Netten A, McNamara S, et al. Assessment of a brain-tumour-specific patient concerns inventory in the neuro-oncology clinic. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1059–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, et al. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1450–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kørner EA LL, Wang A, Lolk A, Christensen P, Nilsson FM. Mini Mental State Examination: validering af en ny dansk udgave. Ugeskrift for læger/Weekly Letter for Physicians. 2008;170(9):745–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37(3):323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weitzner MA, Meyers CA, Gelke CK, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scale. Development of a brain subscale and revalidation of the general version (FACT-G) in patients with primary brain tumors. Cancer. 1995;75(5):1151–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boele FW, van Uden-Kraan CF, Hilverda K, et al. Attitudes and preferences toward monitoring symptoms, distress, and quality of life in glioma patients and their informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):3011–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Gning I, et al. Congruence of primary brain tumor patient and caregiver symptom report. Cancer. 2012;118(20):5026–5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]