Abstract

Purpose

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) required clinicians to use knowledge of therapeutic mechanisms of established drugs to piece together treatment regimens. The purpose of this study is to examine the trends in medication use among patients with COVID-19 across the United States using a national dataset.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of the COVID-19 cohort in the Cerner Real-World Data warehouse, which includes deidentified patient information for encounters associated with COVID-19 from December 1, 2019, through June 30, 2020. The primary variables of interest were medications given to patients during their inpatient COVID-19 treatment. We also identified demographic characteristics, calculated the proportion of patients with each medication, and stratified data by demographic variables.

Findings

Our sample included 51,169 inpatients from every region of the United States. Males and females were equally represented, and most patients were white and non-Hispanic. The largest proportion of patients were older than 45 years. Corticosteroids were used the most among all patients (56.5%), followed by hydroxychloroquine (17.4%), tocilizumab (3.1%), and lopinavir/ritonavir (1.1%). We found substantial variation in medication use by region, race, ethnicity, sex, age, and insurance status.

Implications

Variations in medication use are likely attributable to multiple factors, including the timing of the pandemic by region in the United States and processes by which medications are introduced and disseminated. This study is the first of its kind to assess trends in medication use in a national dataset and is the first large, descriptive study of pharmacotherapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. It provides an important glimpse into prescribing patterns during a pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, drug prescriptions, pharmacotherapy, practice patterns, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

The first major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. As the pandemic was intensifying across the globe, clinicians were caring for patients without proven effective treatments. Because the virus was new, no randomized controlled trials had examined potential treatment options.1, 2, 3 Thus, clinicians were required to use established knowledge of therapeutic mechanisms (Table I ) of existing drugs to piece together treatment regimens.4 Two main strategies emerged as investigators and clinicians shared knowledge on the clinical presentation of the disease: inhibition of viral replication and treatment of the host immune response.5, 6, 7, 8

Table I.

Therapeutic mechanisms of medications hypothesized to treat COVID-19 in the early phase of the pandemic.

| Medication Class | Medication Name | Primary Use | Mechanism of Action | Hypothesized Benefit With COVID-19 and Indications of Use for Benefit | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoquinoline | Chloroquine | To counter the inflammatory response associated with intracellular microbes or autoimmune disease | Direct antiviral activity: the analogs increase intracellular pH to disrupt endosomal trafficking (ie, endosome-mediated cell entry), promote dysfunction of cellular enzymes, and impair protein synthesis. Immune modification: modulates the immune response by reducing cytokine production, including IL-6, and inhibits TLR signaling. |

Disruption of intracellular operations, particularly in lysosome and endosomes, can prevent propagation of the virus and reduce the inflammatory response. Hypothesized to disrupt ACE2 receptor glycosylation to prevent viral binding to epithelial cells. The FDA recommends against use of chloroquine for COVID-19 outside a clinical trial. |

46 |

| Aminoquinoline | Hydroxychloroquine | Similar use as chloroquine with less toxicity | Similar mechanism of action to chloroquine but active metabolite concentration may differ. | Similar benefit as chloroquine with less toxicity; may have more value in combination with azithromycin. No evidence of clinical benefit in hospitalized patients, but retrospective studies have found potential benefit that hints that there may be specific populations that this drug may help. The FDA has revoked its Emergency Use Authorization for hydroxychloroquine for hospitalized patients, and because of the risk of arrhythmias, the FDA recommends against hydroxychloroquine use for COVID-19 outside a clinical trial. |

46 |

| Protease inhibitor | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Reduces viral load in HIV | Protease inhibitor that cleaves polyproteins, resulting in formation of immature, noninfectious viral particles. Ritonavir is a CYP3A4 inhibitor that increases serum concentration of lopinavir, increasing its antiviral activity. |

Had promise against SARS-CoV-2 and MERS, although recommended for use earlier in the infection to reduce viral load and prevent viral replication; suggested in combination with ribavirin and interferon beta. Lopinavir potentially inhibits chymotripsin-like protease in SARS-CoV-2, resulting in decrease viral load. Early triple therapy with lopinavir/ritonavir, interferon beta, and ribavirin was associated with significantly shorter time to alleviation of symptom and shorter hospitals stays. However, no beneficial effects in 28-day mortality, risk of progression to mechanical ventilatory support, or length of hospital stay were noted according to the RECOVERY trial. The NIH recommends against use of lopinavir/ritonavir for treatment of COVID-19 except in a clinical trial. |

12,19 |

| Nucleoside analog | Remdesivir | Antiviral activity against RNA viruses; originally developed against Ebola virus | Inhibits the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and forces early termination of RNA transcription | Success in animal models against SARS-CoV-1 and MERS. Significantly reduces time to clinical recovery, with benefit most apparent in baseline low-flow oxygen–requiring patients, moderate benefit in patients with moderate severity, and minimal or no benefit in patients with severe conditions and data not supportive of 10-day symptom cut-off. The FDA updated Emergency Use Authorization to include remdesivir as a treatment option for all hospitalized patients. The NIH recommends use in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen but who are not receiving high-flow oxygen, noninvasive ventilatory support, mechanical ventilatory support, or ECMO. The NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines recommend use of remdesivir and dexamethasone in patients who require high-flow oxygen, noninvasive ventilatory support, mechanical ventilatory support, or ECMO. |

5, 6,19,47, 48, 49 |

| IL-6 antagonist | Tocilizumab | Inhibitor of IL-6 for treatment of arthritic diseases | Competitively inhibits IL-6 signaling by binding to IL-6 receptor | A single-center study in China found that repeated administration of tocilizumab decreased acute-phase reactants and either treated or prevented the cytokine storm. Although blockage of cytokine receptors reduces inflammation, it also contributes to an increased risk of secondary bacterial and fungal infections. The NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines recommend against use of tocilizumab except in a clinical trial. |

13,15,19 |

| Glucocorticoid | Hydrocortisone | Inhibition of adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells via binding to corticosteroid receptor results in increased encoding of anti-inflammatory proteins and decreased expression of inflammation genes | Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects | Open-label REMAP-CAP study randomized patients to receive hydrocortisone 50–100 mg every 6 hours for 7 days if shock was clinically evident and analysis suggested hydrocortisone was probably superior to no hydrocortisone concerning organ support–free days at 21 days but study was stopped early. |

16, 17 |

| Glucocorticoid | Dexamethasone | Same mechanism of action as hydrocortisone | Anti-inflammatory effects are more potent than antiviral effects | Low-dose dexamethasone (6 mg/d for 10 days) was found in the RECOVERY trial to significantly reduce mortality in patients with COVID-19 requiring respiratory support. The NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines recommend use of 6 mg/d dexamethasone up to 10 days or until hospital discharge in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving mechanical ventilatory support or those who require supplemental oxygen. The NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines recommend against use of dexamethasone in patients who do not require supplemental oxygen. |

16,17 |

| Glucocorticoid | Prednisone | Same mechanism of action as hydrocortisone | The IDSA suggests 40 mg/d prednisone if dexamethasone is not available. | 18 | |

| Glucocorticoid | Methylprednisolone | Same mechanism of action as hydrocortisone | The IDSA suggests 32 mg methylprednisolone if dexamethasone is not available. | 18 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; COVID-19 = coronarvirus disease 2019; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FDA = US Food and Drug Administration; IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America; IL-6 = interleukin 6; MERS = Middle East Respiratory Syndrome; NIH = National Institutes of Health; RECOVERY = Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy; REMAP-CAP = Randomised, Embedded, Multi-factorial, Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TLR = Toll-like receptor.

*We describe the primary mechanisms of action relevant to COVID-19. Many drugs have multiple mechanisms of action. However, it is beyond the scope of this article to include them all.

Inhibition of viral replication in the early stage of infection may prevent disease progression and minimize the cytotoxic immune response (ie, cytokine storm). Medications such as remdesivir (Gilead, Foster City, California) and lopinavir/ritonavir (AbbVie Inc, North Chicago, Illinois) were tapped for off-label use early in the outbreak.1 , 2 , 7 , 9, 10, 11, 12 Both medications interfere with viral transcription, thus stalling replication.

The secondary surge of inflammatory cytokines in SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with extensive lung injury and multiple organ dysfunction.6 Medications such as tocilizumab (Genetech USA Inc, San Francisco, California), designed to block T-cell activation or prevent cytokine release, have proven efficacy in other forms of cytokine-mediated disease.13, 14, 15 Tocilizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to interleukin 6, approved to treat refractory rheumatoid arthritis.13, 14, 15 Corticosteroids and glucocorticoids also prevent or reduce inflammation by inhibiting adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells.16 , 17 By binding corticosteroid receptors, they increase the production of anti-inflammatory proteins and decrease the expression of proinflammatory genes. Hydrocortisone and dexamethasone are glucocorticoids that are structurally and pharmacologically similar to endogenous cortisol and similarly suppress the immune response.3 , 16

Investigators and medical experts have released studies and guidelines for the treatment of COVID-19.18, 19, 20 However, the extent of medication use across the United States to treat COVID-19 is widely unknown. It is likely that regional and institutional preferences have played a large role in treatment plans with little consensus on what works best. The purpose of this study was to examine the trends in medication use among patients with COVID-19 across the United States using a national dataset. We hypothesize that medication use will vary across demographic characteristics of the sample. Some of the variation may mimic the epidemiology of disease severity and the pattern of distribution in the United States over time. Given the challenge of treating a new pathogen, it is important to look back at the trends in use to characterize how clinicians responded to the crisis for future outbreaks of new diseases.

Participants and Methods

Study Design

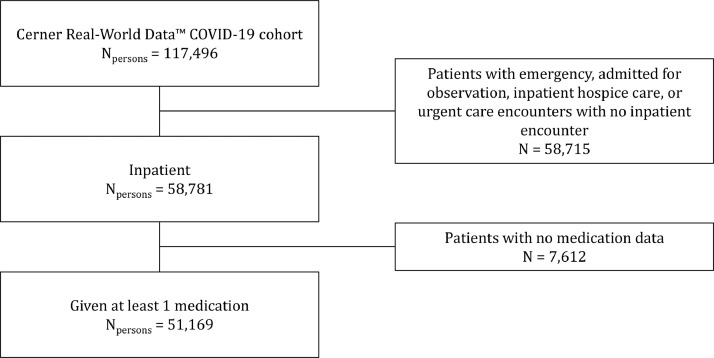

We conducted a cross-sectional study of the COVID-19 cohort in the Cerner Real-World Data warehouse, similar to Cerner's retired Health Facts platform.21 The warehouse includes clinical data extracted from the electronic medical records (EMRs) of 62 health systems in the United States with which Cerner has a data use agreement. The dataset includes deidentified patient-level information for encounters associated with COVID-19 from December 1, 2019, through June 30, 2020 (Figure 1 ). Cerner deidentified the records using a complex algorithm and used Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant operating policies to ensure patient privacy. We used only deidentified information in the secure HealtheDataLab to conduct our study, and it was exempt from institutional review board oversight.22

Figure 1.

Inclusion criteria for the Cerner Real-World Data coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cohort. ED = emergency department.

Participants

We included all pediatric and adult patients in the Cerner COVID-19 dataset who met our inclusion criteria. We included patients in our sample if they (1) had an inpatient encounter type and (2) were prescribed at least 1 medication. We excluded patients who were seen only in the emergency department or as an outpatient. We also excluded patients who did not receive any medication during their inpatient stay. Cerner included records according to unique encounters rather than persons. To sample at the individual patient level, we combined all inpatient encounter data using the unique person identifier variable. Therefore, the unit of analysis for the study is the individual patient.

Variables

The primary variables of interest were medications given to patients during their inpatient COVID-19 treatment, including chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, tocilizumab, hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, and prednisone. We selected these medications for investigation a priori according to previously cited evidence and hypotheses. In this dataset, we found that medications were associated with a generic name and/or a brand name(s), and some names included a dosage. Thus, we truncated the medication name to remove dosage and queried the dataset according to the Cerner Multum list of medication names.23 We included all routes of administration, although these medications are overwhelmingly administered intravenously or orally.

We collected medication use data as a dichotomous variable, with 1 indicating the patient ever received the medication during his or her inpatient encounter(s) for COVID-19. Importantly, Cerner populated the medications in the dataset from reconciliation events, ordering events, and/or administering events. We only counted the medication once per unique person identifier.

We also collected demographic variables, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, payer status, and region of the United States. We included sex as a categorical variable with male, female, and other. We included race and ethnicity as categorical variables as well, with race categorized as white, black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Alaskan Native/American Indian, other, unknown, and mixed and ethnicity as non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and unknown. The COVID-19 cohort included age as a continuous variable except for individuals younger than 18 years (listed at 17 years of age for everyone) and those older than 90 years (listed as 90 years of age for everyone). We chose to categorize the remaining ages by approximately 10-year increments (ie, 18-25, 26-35, and so on). We included payer status to reflect the most common categories found in the COVID-19 dataset, including Medicare, Medicaid, private (health maintenance organization or preferred provider organization), self-pay (point of service), other government (Veterans Affairs or Tricare), other nongovernment, charity, foreign national, workers compensation, and no insurance. Lastly, we included the region of the United States for each patient according to the first digit in his or her zip code (Figure 2 ).24

Figure 2.

Regions of the United States given the first numeral in the postal zip code used to examine regional variation in Cerner Real-World Data coronavirus disease dataset. Region 1 is New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware; region 2, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina; region 3, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and Florida; region 4, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky; region 5, Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin; region 6, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, and Illinois; region 7, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana; region 8, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada; and region 9, Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, and Hawaii.

Statistical Analysis

We performed all statistical analyses with Python in a Jupyter Notebook.25 , 26 We used the Matplotlib, version 3.3.1 library to visualize our results and pandas, version 1.1.3 for data manipulation and analysis.27 , 28 We calculated the proportion of patients with each medication and stratified by demographic variables. We qualitatively compared the distribution of each medication to the overall distribution of the sample.

Results

Participants

The Cerner COVID-19 cohort included 117,496 unique persons who had a diagnosis code that could be associated with COVID-19 exposure or infection or a positive COVID-19 laboratory test result (Figure 3 ). After exclusions, our final sample size was 51,169.

Figure 3.

Sampling strategy for inclusion in study of medication use among inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

There was approximately the same proportion of male and female patients (Table II ) in the dataset, and most were white (55.8%) and non-Hispanic (64.9%). In addition, the largest proportion of patients were older than 45 years. This is consistent with the age groups most at risk for severe disease described early in the pandemic.29, 30, 31 More than one quarter of patients received Medicare benefits, whereas the other most prevalent payer status was private (25.0%) and noninsured (22.1%). Lastly, the regions with the highest contribution to the dataset included region 0 (16.3%), region 2 (14.4%), region 3 (15.9%), and region 9 (16.6%).

Table II.

Sample characteristics and volume of medication use among inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the Cerner Real-World Dat COVID dataset.*

| Characteristic | Total (N = 51,169) | Hydroxychloroquine (n = 8906) | Corticosteroids (n = 28,966)† | Tocilizumab (n = 1611) | Lopinavir/Ritonavir (n = 576) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 24,860 (48.6) | 4788 (53.8) | 13,691 (47.3) | 1081 (67.1) | 347 (60.2) |

| Female | 26,218 (51.2) | 4100 (46) | 15217 (52.5) | 527 (32.7) | 229 (39.8) |

| Other | 91 (0.2) | 18 (0.2) | 58 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 28,544 (55.8) | 4009 (45) | 17,266 (59.6) | 616 (38.2) | 284 (49.3) |

| Black/African American | 10,429 (20.4) | 2209 (24.8) | 5577 (19.3) | 359 (22.3) | 88 (15.3) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1532 (3.0) | 361 (4.1) | 804 (2.8) | 79 (4.9) | 25 (4.3) |

| Alaskan Native/American Indian | 1114 (2.2) | 211 (2.4) | 540 (1.9) | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 6949 (13.6) | 1575 (17.7) | 3523 (12.2) | 384 (23.8) | 53 (9.2) |

| Unknown | 2563 (5.0) | 539 (6.1) | 1231 (4.2) | 166 (10.3) | 126 (21.9) |

| Mixed | 38 (0.1) | 2 (0.0) | 25 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 33,228 (64.9) | 5727 (64.3) | 18,969 (65.5) | 871 (54.1) | 374 (64.9) |

| Hispanic | 12,770 (25.0) | 1849 (20.8) | 7478 (25.8) | 433 (26.9) | 172 (29.9) |

| Unknown | 5171 (10.1) | 1330 (14.9) | 2519 (8.7) | 307 (19.1) | 30 (5.2) |

| Age, y | |||||

| <18 | 4670 (9.1) | 55 (0.6) | 2170 (7.5) | 20 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| 18–25 | 2438 (4.8) | 150 (1.7) | 1146 (4.0) | 23 (1.4) | 9 (1.6) |

| 26–35 | 4451 (8.7) | 480 (5.4) | 2384 (8.2) | 79 (4.9) | 28 (4.9) |

| 36–45 | 4378 (8.6) | 844 (9.5) | 2523 (8.7) | 157 (9.7) | 56 (9.7) |

| 46–55 | 6649 (13.0) | 1488 (16.7) | 3920 (13.5) | 315 (19.6) | 90 (15.6) |

| 56–65 | 9039 (17.7) | 2024 (22.7) | 5451 (18.8) | 445 (27.6) | 127 (22.0) |

| 66–75 | 8551 (16.7) | 1859 (20.9) | 5232 (18.1) | 376 (23.3) | 112 (19.4) |

| 76–85 | 6968 (13.6) | 1335 (15.0) | 4042 (14.0) | 158 (9.8) | 89 (15.5) |

| ≥86 | 4025 (7.9) | 671 (7.5) | 2098 (7.2) | 38 (2.4) | 64 (11.1) |

| Payer status | |||||

| Medicare | 14,528 (28.4) | 2964 (33.3) | 8179 (28.2) | 394 (24.5) | 203 (35.2) |

| Medicaid | 8681 (17.0) | 1253 (14.1) | 4233 (14.6) | 242 (15.0) | 86 (14.9) |

| Private (HMO, PPO) | 12,785 (25.0) | 2926 (32.9) | 7469 (25.8) | 581 (36.1) | 156 (27.1) |

| Self-pay (POS) | 2126 (4.2) | 268 (3.0) | 1153 (4.0) | 46 (2.9) | 20 (3.5) |

| Other government (VA, Tricare) | 912 (1.8) | 101 (1.1) | 471 (1.6) | 14 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) |

| Other nongovernment | 439 (0.9) | 157 (1.8) | 160 (0.6) | 32 (2.0) | 89 (15.5) |

| Charity | 218 (0.4) | 31 (0.3) | 86 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Foreign national | 38 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 29 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Workers compensation | 127 (0.2) | 30 (0.3) | 57 (0.2) | 11 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) |

| No insurance | 11,315 (22.1) | 1175 (13.2) | 7129 (24.6) | 284 (17.6) | 19 (3.3) |

| US region‡ | |||||

| 0 (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey) | 8332 (16.3) | 2259 (25.4) | 4264 (14.7) | 374 (23.2) | 378 (65.6) |

| 1 (New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware) | 4242 (8.3) | 1524 (17.1) | 2206 (7.6) | 308 (19.1) | 56 (9.7) |

| 2 (Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina) | 7380 (14.4) | 1128 (12.7) | 3636 (12.6) | 264 (16.4) | 15 (2.6) |

| 3 (Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and Florida) | 8117 (15.9) | 1063 (11.9) | 5209 (18.0) | 222 (13.8) | 24 (4.2) |

| 4 (Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky) | 3400 (6.6) | 523 (5.9) | 1834 (6.3) | 47 (2.9) | 5 (0.9) |

| 5 (Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin) | 354 (0.7) | 60 (0.7) | 238 (0.8) | 11 (0.7) | 15 (2.6) |

| 6 (Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, and Illinois) | 2530 (4.9) | 192 (2.2) | 1658 (5.7) | 30 (1.9) | 4 (0.7) |

| 7 (Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana) | 3350 (6.5) | 470 (5.3) | 2138 (7.4) | 63 (3.9) | 38 (6.6) |

| 8 (Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada) | 4745 (9.3) | 779 (8.7) | 2771 (9.6) | 66 (4.1) | 12 (2.1) |

| 9 (Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, and Hawaii) | 8488 (16.6) | 908 (10.2) | 5012 (17.3) | 226 (14) | 29 (5) |

| Not reported | 231 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

HMO = health maintenance organization; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider organization; VA = Veterans Affairs.

Data are the number (percentage) of medication users that were in each demographic category (ie, the proportion of patients who used corticosteroids who were non-Hispanic).

Corticosteroids included dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisone, and hydrocortisone.

Regions determined according to the first number of patient's zip code.

Medication Use

Overall Trends

We present the distributions of each medication used in the sample in Tables II and III . Supplemental Figures 1 through 6 display the proportion of medication use within demographic subgroups. As a class, corticosteroids were used the most among all patients (56.5%), followed by hydroxychloroquine (17.4%), tocilizumab (3.1%), and lopinavir/ritonavir (1.1%). The type of corticosteroid prescribed was similar across dexamethasone (28.3%), methylprednisolone (31.2%), and prednisone (24.7%), whereas prednisolone and hydrocortisone were used much less frequently (3.3% and 12.2%, respectively).

Table III.

Sample characteristics and volume of specific corticosteroid use among inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the Cerner Real-World Data coronavirus disease dataset.*

| Characteristic | Total patients (N = 51,169) | Dexamethasone (n = 14,456) | Methylprednisolone (n = 15,964) | Prednisolone (n = 1704) | Prednisone (n = 12,650) | Hydrocortisone (n = 6239) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 24,860 (48.6) | 6566 (45.4) | 7607 (47.7) | 876 (51.4) | 5608 (44.3) | 2770 (44.4) |

| Female | 26,218 (51.2) | 7861 (54.4) | 8328 (52.2) | 820 (48.1) | 7021 (55.5) | 3456 (55.4) |

| Other | 91 (0.2) | 29 (0.2) | 29 (0.2) | 8 (0.5) | 21 (0.2) | 13 (0.2) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 28,544 (55.8) | 8752 (60.5) | 9769 (61.2) | 934 (54.8) | 7908 (62.5) | 3643 (58.4) |

| Black/African American | 10,429 (20.4) | 2731 (18.9) | 2975 (18.7) | 379 (22.2) | 2546 (20.1) | 1197 (19.2) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1532 (3.0) | 374 (2.6) | 437 (2.8) | 43 (2.6) | 314 (2.5) | 178 (2.9) |

| Alaskan Native/American Indian | 1114 (2.2) | 269 (1.9) | 266 (1.7) | 37 (2.2) | 159 (1.3) | 125 (2.0) |

| Other | 6949 (13.6) | 1762 (12.2) | 1836 (11.5) | 223 (13.1) | 1290 (10.2) | 797 (12.8) |

| Unknown | 2563 (5.0) | 562 (3.9) | 669 (4.2) | 82 (4.8) | 425 (3.4) | 291 (4.7) |

| Mixed | 38 (0.1) | 6 (0.0) | 12 (0.1) | 6 (0.4) | 8 (0.1) | 8 (0.1) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 33,228 (64.9) | 9372 (64.8) | 10,519 (65.9) | 1007 (59.1) | 9082 (71.8) | 4056 (65) |

| Hispanic | 12,770 (25.0) | 3931 (27.2) | 4063 (25.5) | 461 (27.1) | 2746 (21.7) | 1470 (23.6) |

| Other | 5171 (10.1) | 1153 (8) | 1382 (8.7) | 236 (13.8) | 822 (6.5) | 713 (11.4) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| <18 | 4670 (9.1) | 1346 (9.3) | 737 (4.6) | 778 (45.7) | 318 (2.5) | 735 (11.8) |

| 18-25 | 2438 (4.8) | 627 (4.3) | 439 (2.7) | 37 (2.2) | 450 (3.6) | 318 (5.1) |

| 26-35 | 4451 (8.7) | 1283 (8.9) | 955 (6) | 47 (2.8) | 977 (7.7) | 640 (10.3) |

| 36-45 | 4378 (8.6) | 1421 (9.8) | 1264 (7.9) | 66 (3.9) | 1108 (8.8) | 479 (7.7) |

| 46-55 | 6649 (13.0) | 2067 (14.3) | 2238 (14) | 119 (7) | 1807 (14.3) | 696 (11.2) |

| 56-65 | 9039 (17.7) | 2742 (19) | 3356 (21) | 190 (11.2) | 2678 (21.2) | 1094 (17.5) |

| 66-75 | 8551 (16.7) | 2468 (17.1) | 3223 (20.2) | 221 (13) | 2454 (19.4) | 1026 (16.4) |

| 76-85 | 6968 (13.6) | 1729 (12) | 2534 (15.9) | 182 (10.7) | 1937 (15.3) | 842 (13.5) |

| ≥86 | 4025 (7.9) | 773 (5.3) | 1218 (7.6) | 64 (3.8) | 921 (7.3) | 409 (6.6) |

| Payer status | ||||||

| Medicare | 14,528 (28.4) | 3957 (27.4) | 5296 (33.2) | 380 (22.3) | 4047 (32.0) | 1817 (29.1) |

| Medicaid | 8681 (17.0) | 2442 (16.9) | 2298 (14.4) | 388 (22.8) | 1744 (13.8) | 938 (15) |

| Private (HMO, PPO) | 12,785 (25.0) | 3998 (27.7) | 4082 (25.6) | 389 (22.8) | 2981 (23.6) | 1630 (26.1) |

| Self-pay (POS) | 2126 (4.2) | 527 (3.6) | 484 (3) | 41 (2.4) | 478 (3.8) | 105 (1.7) |

| Other government (VA, Tricare) | 912 (1.8) | 218 (1.5) | 232 (1.5) | 18 (1.1) | 187 (1.5) | 85 (1.4) |

| Other nongovernment | 439 (0.9) | 81 (0.6) | 119 (0.7) | 4 (0.2) | 78 (0.6) | 34 (0.5) |

| Charity | 218 (0.4) | 72 (0.5) | 69 (0.4) | 2 (0.1) | 37 (0.3) | 9 (0.1) |

| Foreign national | 38 (0.1) | 26 (0.2) | 15 (0.1) | 9 (0.5) | 3 (0.0) | 22 (0.4) |

| Workers compensation | 127 (0.2) | 46 (0.3) | 37 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 14 (0.1) | 13 (0.2) |

| No insurance | 11,315 (22.1) | 3089 (21.4) | 3332 (20.9) | 473 (27.8) | 3081 (24.4) | 1586 (25.4) |

| US region† | ||||||

| 0 (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey) | 8332 (16.3) | 1826 (12.6) | 2401 (15) | 292 (17.1) | 1771 (14) | 958 (15.4) |

| 1 (New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware) | 4242 (8.3) | 913 (6.3) | 1335 (8.4) | 90 (5.3) | 1053 (8.3) | 532 (8.5) |

| 2 (Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina) | 7380 (14.4) | 1810 (12.5) | 1719 (10.8) | 224 (13.1) | 1622 (12.8) | 857 (13.7) |

| 3 (Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and Florida) | 8117 (15.9) | 2478 (17.1) | 3190 (20) | 265 (15.6) | 2059 (16.3) | 1071 (17.2) |

| 4 (Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky) | 3400 (6.6) | 797 (5.5) | 991 (6.2) | 65 (3.8) | 991 (7.8) | 348 (5.6) |

| 5 (Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin) | 354 (0.7) | 130 (0.9) | 139 (0.9) | 17 (1.0) | 143 (1.1) | 51 (0.8) |

| 6 (Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, and Illinois) | 2530 (4.9) | 945 (6.5) | 863 (5.4) | 194 (11.4) | 850 (6.7) | 454 (7.3) |

| 7 (Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana) | 3350 (6.5) | 1256 (8.7) | 1168 (7.3) | 182 (10.7) | 832 (6.6) | 332 (5.3) |

| 8 (Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada) | 4745 (9.3) | 1586 (11) | 1541 (9.7) | 114 (6.7) | 1081 (8.5) | 469 (7.5) |

| 9 (Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, and Hawaii) | 8488 (16.6) | 2674 (18.5) | 2617 (16.4) | 255 (15) | 2211 (17.5) | 1146 (18.4) |

| Not reported | 231 (0.5) | 41 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.4) | 37 (0.3) | 21 (0.3) |

HMO = health maintenance organization; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider organization; VA = Veterans Affairs.

Data are the number (percentage) of medication users who were in each demographic category (ie, the proportion of non-Hispanic patients who used dexamethasone).

Regions determined according to the first number of patient's zip code.

We did not find remdesivir or choloroquine within this dataset. Chloroquine may not have been readily available because hydroxychloroquine is a newer adaptation of the drug and more commonly available in the United States. In addition, the Cerner team noted in communication to users (unpublished data) that remdesivir was not included because it was rarely recorded in the standard medication section of the EMR. The medication was experimental and required a compassionate use designation early in the pandemic. Thus, hospitals recorded it in the clinical research (or similar) section of the EMR instead.

Hydroxychloroquine

The distribution of hydroxychloroquine across demographic groups differed from the distribution of the sample in several notable ways (Table II). First, 53.8% of patients who took hydroxychloroquine were male, although males made up only 48.6% of the sample. In addition, white patients accounted for 45% of hydroxychloroquine users, although they represented 55.8% of the sample. In addition, differences across age groups were found when compared with the sample distribution, and only 13.2% of hydroxychloroquine use was among patients without insurance, although the group accounted for 22.1% of the sample. We also found a higher proportion of hydroxychloroquine use among patients in region 0 when compared with the sample distribution (25.4% and 16.3%, respectively).

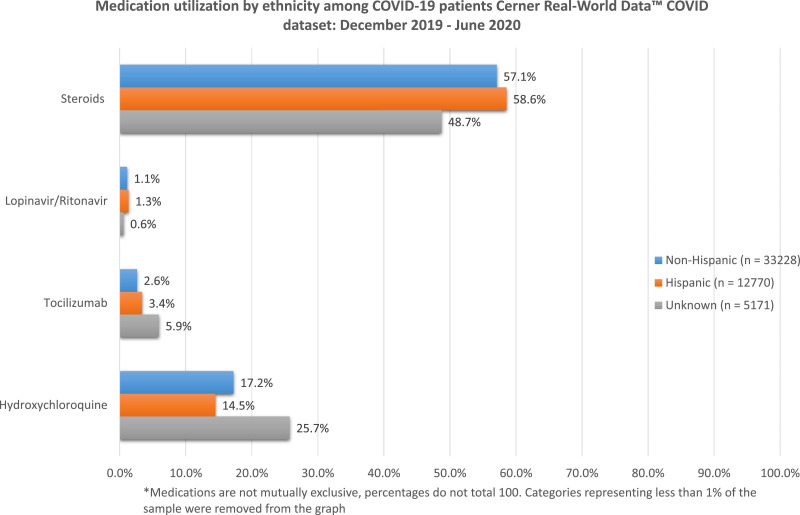

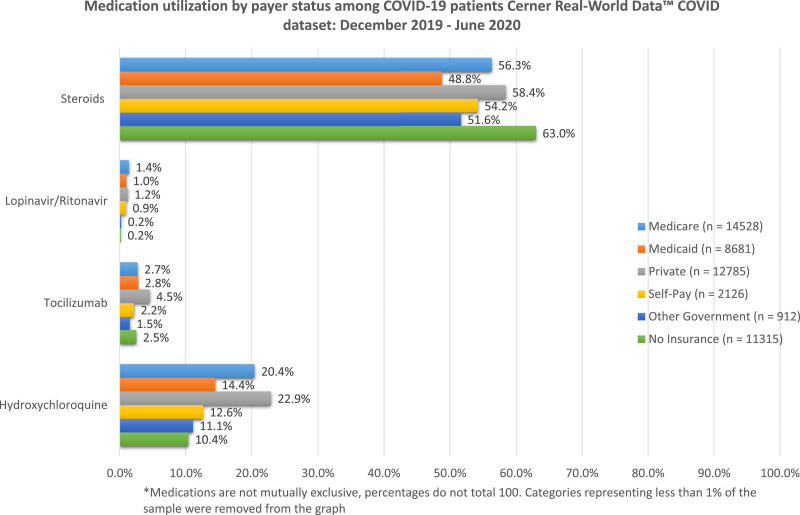

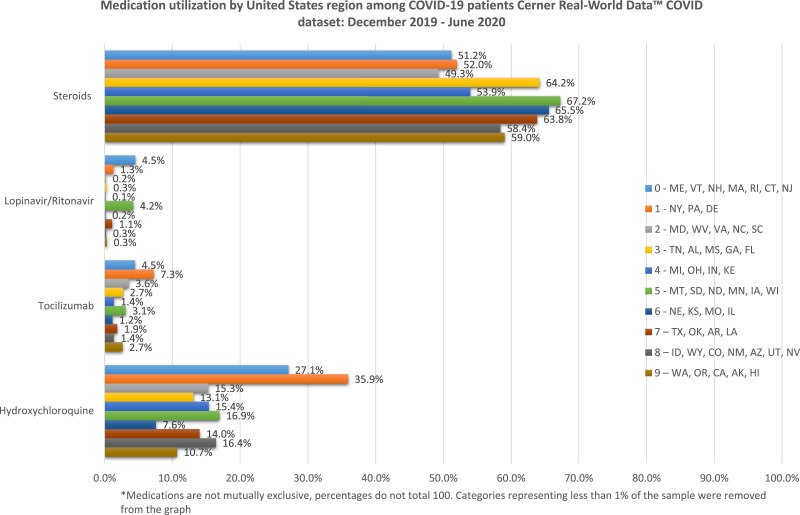

A larger proportion of males took hydroxychloroquine than females (Supplemental Figure 1), and a larger proportion of non-Hispanic patients (17.2%) took hydroxychloroquine compared with Hispanic patients (14.5%) (Supplemental Figure 3). Patients between the ages of 46 and 75 years used more hydroxychloroquine than other groups, with very little use in patients younger than 35 years (1.2%–10.8%) (Supplemental Figure 4). Patients with private health insurance and Medicare also used more hydroxychloroquine, whereas patients without insurance had the lowest hydroxychloroquine use across payer groups (Supplemental Figure 5). Lastly, patients in regions 1 and 0 used more hydroxychloroquine than those in any other region in the United States (Supplemental Figure 6).

Corticosteroids

The distribution of corticosteroid use across demographic groups was generally consistent with the overall distribution (Table III). Medicare patients accounted for 33.2% and 32.0% of methylprednisolone and prednisone use, respectively, although they represented 28.4% of the sample. White patients also accounted for a higher proportion of dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, prednisone, and hydrocortisone use than the sample distribution. Alternatively, black patients accounted for less than the distribution for each corticosteroid except for prednisolone. Lastly, patients younger than 18 years accounted for 45.7% of prednisolone use, although they represented only 9.1% of the sample.

There were also group differences in corticosteroid use. We found that a higher proportion of males took corticosteroids than females, and more white patients were prescribed corticosteroids compared with patients of other race categories. Differences in corticosteroid use were found across all age groups as well as among 46- to 75-year-olds. Corticosteroid use was also highly variable across payer status and region.

Tocilizumab

There were several marked differences in the distribution of tocilizumab when compared with the distribution of the sample. Males accounted for 67.1% of the tocilizumab prescribed, although the distribution of males in the sample is 48.6%. White patients accounted for only 38.2% of the tocilizumab users, although they represented 55.8% of the sample, whereas patients of other races accounted for 23.8% of tocilizumab users but only 13.6% of the sample. Patients with unknown ethnicity used more tocilizumab compared with non-Hispanic patients, although there was a greater proportion of non-Hispanic patients in the sample. Most of the tocilizumab consumed was among patients older than 45 years and patients with private insurance or Medicare. Patients without insurance accounted for a lower proportion of tocilizumab users than the sample distribution (17.6% and 22.1%, respectively).

We found that males used more tocilizumab than females, although the proportion of use was <5% for both sexes. In addition, a difference in tocilizumab use was found across races. Differences were also found in age groups, with the most notable differences between patients <35 or >76 years of age compared with those between 36 and 75 years of age. Patients with private insurance (4.5%) also used more tocilizumab compared with other payer groups (<2.8%). Lastly, patients in region 1 (7.3%) used more tocilizumab than patients in other regions (<4.5%).

Lopinavir/Ritonavir

The distribution of lopinavir/ritonavir mirrored the differences seen in tocilizumab when compared with the full sample. A higher proportion of males accounted for lopinavir/ritonavir use than their distribution in the sample. White patients also accounted for less lopinavir/ritonavir use than their distribution in the sample, whereas patients with unknown race accounted for more (21.9% and 5.0%, respectively). The proportion of patients without insurance who used lopinavir/ritonavir was distinctly lower than their distribution in the sample (3.3% and 22.1%, respectively), whereas patients in the other nongovernment group accounted for more (15.5% and 0.9%, respectively). Lastly, most lopinavir/ritonavir use was attributed to patients in region 0 (65.6%), although their distribution in the sample was 16.3%.

We found differences in lopinavir/ritonavir juse across all demographic groups. However, the proportion of each demographic that used the medication was <2% in almost all groups. We found the greatest differences between races and regions, with patients of unknown race using more lopinavir/ritonavir than other groups. Patients in regions 0 and 5 also used more lopinavir/ritonavir than the other regions of the United States.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the use of medication among inpatients with COVID-19 across the United States during the first wave of the pandemic. Because of the new nature of the virus, clinicians pieced together treatment strategies in the absence of a solid evidence base. We found substantial variation in medication use by region, race, ethnicity, sex, age, and insurance status. These variations are likely attributable to multiple factors, including the timing of the pandemic by region in the United States and processes by which medications are introduced and disseminated.

Timing of the Pandemic

We found that hydroxychloroquine use was greatest in the northeast (ie, regions 0 and 1), where COVID-19 peaked the earliest in the United States (March to May).32 During this time, hydroxychloroquine was prominent in the popular press, undergoing academic study for potential benefit in COVID-19 and being prescribed at record levels across the United States.33 Peaks in other regions of the United States occurred in June and later because hydroxychloroquine fell out of favor after publication and retraction of a manuscript in the Lancet 34 and the revocation of the US Food and Drug Administration's previously issued emergency use authorization.35 Similarly, lopinavir/ritonavir was primarily used in the northeastern United States because the initial surge took place in these regions before and immediately after the release of the article in the New England Journal of Medicine that reported a lack of efficacy of the medication.12

Medication Endorsement and Dissemination

The introduction of COVID-19 required early innovation and imagination among health care professionals. The processes necessary for medication acquisition, prescribing, and administration may help explain the trends we see in this study. First, and most importantly, the medications repurposed for COVID-19 needed to be safe and have benefits that outweighed the risks. Hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir are examples of medications that were used in the context of COVID-19 until the risks outweighed the perceived benefits.12 , 36

Availability is also a likely determinant of medication use for COVID-19. Several studies describe widespread disruptions in drug manufacturing, difficulties procuring inventory, and drug shortages as important barriers to patient treatment early in the pandemic.37 , 38 Burry et al39 noted the “highly volatile state of prescribing” that stressed the system and led to quick changes in supply and demand with the release of new (and often conflicting) information. In addition, we hypothesize that drug cost contributed to variability in this sample. Individuals in the private insurance group used substantially more tocilizumab and hydroxychloroquine than those in other payer groups, whereas patients in the uninsured group used more corticosteroids. This is a new finding; to date, no studies have identified a role for payer status influencing inpatient drug prescription.

Equally important in medication use is stakeholder buy-in. Key opinion leaders are experts in their respective fields that can legitimize new treatment ideas and serve as sources of authority in complex situations.39, 40, 41 Lopinavir/ritonavir use was greatest in regions 0 and 5. It is possible that the excess use in region 0 reflects the timing of the pandemic and regional enthusiasm among key opinion leaders. Lopinavir/ritonavir held promise as an antiviral medication and was used with some frequency before the May New England Journal of Medical article describing no benefit.12 This timing coincides with peak inpatient census in region 0. The higher use of tocilizumab in the northeast (regions 0 and 1) may also reflect the influence of regional enthusiasm for the use of this drug, with prominent institutions favoring early use in severe disease.

In addition, key opinion leaders likely played an important role in the use of corticosteroids among patients with COVID-19. Early global guidelines recommended against the use of corticosteroids in this population.20 However, it is clear from our data that corticosteroids were repeatedly used among patients with COVID-19 before formal evidence became available.3 Evidence suggests that key opinion leaders and support structures are stronger determinants of prescribing than clinical guidelines, particularly when working with new medications.39 We hypothesize that frontline health care workers looked to key opinion leaders in the field for clinical decision making in the absence of a solid evidence base.

Disease Severity

The severity of disease likely played a role in medication use. We found greater use of hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab in males than females, which may reflect the evidence that males were at greater risk of severe disease than females.42 In addition, patients in the unknown race and ethnicity categories used more of these medications. These patients are difficult to analyze, although we hypothesize that these individuals are in minority groups given the challenges with standard classification in a diverse country.43, 44, 45

Limitations

An important limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which provides only a snapshot of medication use at a single point. We used the data descriptively and did not assess outcomes after medication use. The study design also prevented us from drawing conclusions from the data. Rather, we generated more hypotheses on medication use that need to be tested.

We were also limited by the structure of the dataset. The Cerner Real-World Data warehouse uses a complex algorithm to deidentify patients and ensure confidentiality. One of the primary ways encounters were deidentified was through date shifting (ie, forwards or backwards in 7-day increments [±7, 14, 21, and so on]). As a result, we were unable to reliably trend medication use over time. We acknowledge that inferences related to time may be substantial and require cautious data interpretation.

In addition, we found a discrepancy in the inpatient data that led us to exclude patients. Notably, we found it unusual that more than 7000 inpatients did not receive any medications during their inpatient stay. On inquiry with the Cerner COVID-19 data team, we learned that they continue to troubleshoot the dataset to determine the reason for this occurrence. We provide descriptive statistics for the excluded patients in Supplemental Table I. There are notable differences in the distribution of the excluded patients and study sample. There are larger proportions of Hispanics and patients without insurance in the excluded sample. In addition, >30% were from the Pacific Coast. These limitations are important to keep in mind in the interpretation of the findings of this study. Nonetheless, the final sample provides important information that can be used to meet our objective.

Finally, the dataset did not include 1 of the leading medicines used to treat COVID-19. We know clinicians used remdesivir experimentally during the early surge of the pandemic. However, we were not able to assess the scope of the medication use in this study given limitations of the electronic medical record (described previously). It is also possible that electronic medical records inconsistently captured other experimental medications, and we may be underreporting them.

Conclusions

This study is the first of its kind to assess trends in medication use in a national dataset and is the first large descriptive study of pharmacotherapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. We provide an important glimpse into prescribing patterns during a pandemic and generate many hypotheses that should be tested to further understand the determinants of medication use in global emergencies.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Joann Petrini, Vice President for Innovation and Research at Nuvance Health, for her solid support and facilitation of our partnership with the Cerner Learning Health Network. We also acknowledge Mary Shah, MLS, AHIP, medical librarian and archivist at Norwalk Hospital. Lastly, we acknowledge all the health care professionals in our network and across our country who have worked tirelessly to identify treatment strategies to save the lives of patients infected with COVID-19.

Disclosures

S. Stroever takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. S. Stroever, D. Ostapenko, D. Pusztai, L. Coritt, and A. Frimpong were involved in conception and design of the research study, data acquisition, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. R. Scatena and P. Nee were involved in data interpretation, drafting of the article, and revising for critically important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version submitted.

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics of patients excluded due to incomplete medication data in the Cerner Real-World Data™ COVID dataset.

| Sample Characteristics | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Total Patients | 7612 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3706 (48.7) |

| Female | 3902 (51.3) |

| Other | 4 (0.1) |

| Race | |

| White | 5966 (78.4) |

| Black/African American | 665 (8.7) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 214 (2.8) |

| Alaskan Native/American Indian | 19 (0.2) |

| Other | 434 (5.7) |

| Unknown | 287 (3.8) |

| Mixed | 27 (0.4) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 2771 (36.4) |

| Hispanic | 2836 (37.3) |

| Unknown | 2005 (26.3) |

| Age | |

| <18 years | 634 (8.3) |

| 18-25 years | 322 (4.2) |

| 26-35 years | 541 (7.1) |

| 36-45 years | 616 (8.1) |

| 46-55 years | 928 (12.2) |

| 56-65 years | 1290 (16.9) |

| 66-75 years | 1434 (18.8) |

| 76-85 years | 1207 (15.9) |

| ≥86 years | 640 (8.4) |

| Payer Status | |

| Medicare | 1874 (24.6) |

| Medicaid | 1295 (17.0) |

| Private (HMO, PPO) | 1197 (15.7) |

| Self-Pay (POS) | 285 (3.7) |

| Other Government (VA, Tricare) | 121 (1.6) |

| Other Non-Government | 76 (1.0) |

| Charity | 7 (0.1) |

| Foreign National | 0 (0.0) |

| Workers Compensation | 14 (0.2) |

| No Insurance | 2743 (36.0) |

| United States Region‡ | |

| 0 - ME, VT, NH, MA, RI, CT, NJ | 245 (3.2) |

| 1 - NY, PA, DE | 8 (0.1) |

| 2 - MD, WV, VA, NC, SC | 194 (2.5) |

| 3 - TN, AL, MS, GA, FL | 12 (0.2) |

| 4 - MI, OH, IN, KE | 64 (0.8) |

| 5 - MT, SD, ND, MN, IA, WI | 0 (0.0) |

| 6 - NE, KS, MO, IL | 87 (1.1) |

| 7 – TX, OK, AR, LA | 5 (0.1) |

| 8 – ID, WY, CO, NM, AZ, UT, NV | 6 (0.1) |

| 9 – WA, OR, CA, AK, HI | 2516 (33.1) |

| Not reported | 4475 (58.8) |

Note: Data are n (column %)

Supplemental Figure 1.

Supplemental Figure 2.

Supplemental Figure 6.

Supplemental Figure 7.

Supplemental Figure 8.

Supplemental Figure 9.

References

- 1.Grein J., Ohmagari N., Shin D., et al. Compassionate use of Remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pundi K., Perino A.C., Harrington R.A., Krumholz H.M., Turakhia M.P. Characteristics and strength of evidence of COVID-19 studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. JAMA Intern Med. July 27, 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2904. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 — Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. July 17, 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh T.U., Parida S., Lingaraju M.C., Kesavan M., Kumar D., Singh R.K. Drug repurposing approach to fight COVID-19. Pharmacol Rep PR. 2020;72:1479–1508. doi: 10.1007/s43440-020-00155-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gil C., Ginex T., Maestro I., et al. COVID-19: Drug targets and potential treatments. J Med Chem. June 26, 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00606. Published onlineacs.jmedchem.0c00606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlow A., Landolf K.M., Barlow B., et al. Review of emerging pharmacotherapy for the treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2020;40:416–437. doi: 10.1002/phar.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijayvargiya P., Esquer Garrigos Z., Castillo Almeida N.E., Gurram P.R., Stevens R.W., Razonable R.R. Treatment considerations for COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1454–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu C.-C., Chen M.-Y., Lee W.-S., Chang Y.-L. Potential therapeutic agents against COVID-19: What we know so far. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83:534–536. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko W.-C., Rolain J.-M., Lee N.-Y., et al. Arguments in favour of remdesivir for treating SARS-CoV-2 infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendaus M.A. Remdesivir in the treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): a simplified summary. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1767691. Published online May 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y., Zhang D., Du G., et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. The Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guaraldi G., Meschiari M., Cozzi-Lepri A., et al. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e474–e484. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X., Han M., Li T., et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:10970–10975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo P., Liu Y., Qiu L., Liu X., Liu D., Li J. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: A single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020;92:814–818. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eljaaly K., Tuscon A.Z. September 15, 2020. Corticosteroids: A review of pertinent drug information for SARS-CoV-2. Presented at the Society of Infectious Disease Pharmacists.https://sidp.org/resources/Documents/COVID19/Kahlid%20Eljaaly%206.24.2020%20Handouts.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Writing Committee for the REMAP-CAP Investigators. Angus D.C., Derde L., et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19: The REMAP-CAP COVID-19 corticosteroid domain randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1317. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhimraj A., Morgan R., Hirsch Shumaker A., et al. Infectious Disease Society of America; 2020. Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19.https://www.idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/practice-guidelines/covid-19/treatment/idsa-covid-19-gl-tx-and-mgmt-v3.3.0.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institutes of Health . 2020. Therapeutic management of patients with COVID-19. COVID-19 treatment guidelines.https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapeutic-management/ Published October 9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . 27 May 2020. Clinical Management of COVID-19: Interim Guidance; p. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehwerhemuepha L., Gasperino G., Bischoff N., Taraman S., Chang A., Feaster W. HealtheDataLab – a cloud computing solution for data science and advanced analytics in healthcare with application to predicting multi-center pediatric readmissions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20:115. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerner Corporation . Cerner; 2020. HealtheDataLab: Improving population health with a secure, next-generation research tool.https://www.cerner.com/gb/en/pages/healthedatalab-improving-population-health-with-a-secure-next-generation-research-tool Published. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerner Corporation . Cerner; 2020. Drug Database.https://www.cerner.com/solutions/drug-database Published. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ZIP Code Zones . 2020. United States Zip Codes.org.https://www.unitedstateszipcodes.org/images/zip-codes/zip-codes.png Published. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossum G. van. Python Reference Manual. 2.0.1. (Fred Drake, Jr., ed.). Python Software Foundation; 2001. https://docs.python.org/2.0/ref/ref.html

- 26.Kluyver T., Ragan-Kelley B., Perez F., et al. In: Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas. Loizides F, Schmidt B, editors. International ICCC/IFIP Conference on Electronic Publishing; 2016. Jupyter Notebooks - a publishing format for reproducible computational workflows; pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunter J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput Sci Eng. 2007;9(3):90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reback J., McKinney W., Jbrockmendel, et al. Zenodo; 2020. Pandas-Dev/Pandas: Pandas 1.1.3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckner F.S., McCulloch D.J., Atluri V., et al. Clinical features and outcomes of 105 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Seattle, Washington. Clin Infect Dis. May 22, 2020:ciaa632. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa632. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zangrillo A., Beretta L., Scandroglio A.M., et al. Characteristics, treatment, outcomes and cause of death of invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19 ARDS in Milan, Italy. Crit Care Resusc J Australas Acad Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1441-2772(23)00387-3. Published online April 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer A.J., Morley E.J., Meyers K., et al. Cohort of four thousand four hundred four persons under investigation for COVID-19 in a New York hospital and predictors of ICU care and ventilation. Ann Emerg Med. May 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.05.011. Published onlineS019606442030353X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Atlantic . 2020. Our Data.https://covidtracking.com/data The COVID Tracking Project. Published. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bull-Otterson L., Gray E.B., Budnitz D.S., et al. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine prescribing patterns by provider specialty following initial reports of potential benefit for COVID-19 treatment — United States, January–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1210–1215. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehra M.R., Desai S.S., Ruschitzka F., Patel A.N. RETRACTED: Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide for treatment of COVID-19: a multinational registry analysis. The Lancet. May 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31180-6. Published onlineS0140673620311806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Hinton D. June 15, 2020. Letter revoking EUA for chloroquine phosphate and hydroxychloroquine sulfate.https://www.fda.gov/media/138945/download 6/15/2020. Published online. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercuro N.J., Yen C.F., Shim D.J., et al. Risk of QT interval prolongation associated with use of hydroxychloroquine with or without concomitant azithromycin among hospitalized patients testing positive for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1036. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burry L.D., Barletta J.F., Williamson D., et al. It takes a village…: Contending with drug shortages during disasters. Chest. 2020;158:2414–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dzierba A.L., Pedone T., Patel M.K., et al. Rethinking the Drug Distribution and Medication Management Model: How a New York City Hospital Pharmacy Department Responded to COVID-19. J Am Coll Clin Pharm JACCP. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jac5.1316. Published online August 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chauhan D., Mason A. Factors affecting the uptake of new medicines in secondary care - a literature review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33:339–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee A.L. Who are the opinion leaders? The physicians, pharmacists, patients, and direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. J Health Commun. 2010;15:629–655. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meffert J.J. Key opinion leaders: where they come from and how that affects the drugs you prescribe. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:262–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boehmer U., Kressin N.R., Berlowitz D.R., Christiansen C.L., Kazis L.E., Jones J.A. Self-reported vs administrative race/ethnicity data and study results. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1471–1472. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buescher P.A., Gizlice Z., Jones-Vessey K.A. Discrepancies between published data on racial classification and self-reported race: evidence from the 2002 North Carolina live birth records. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2005;120:393–398. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaslavsky A.M., Ayanian J.Z., Zaborski L.B. The validity of race and ethnicity in enrollment data for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1300–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kassamali Escobar Z., Society of Infectious Disease Pharmacists . 2020. Chloroquine & hydroxychloroquine: A review of pertinent drug information for SARS-CoV-2.https://sidp.org/resources/Documents/COVID19/Zahra%20K%20Escobar%208.7.2020%20Handouts.pdf Published online 8/7/Accessed 10/29/2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis M. 2020. Society of Infectious Disease Pharmacists. Remdesivir (GS-5734): A review of pertinent drug information for SARS-CoV-2.https://sidp.org/resources/Documents/COVID19/Matt%20Davis%20%2010.22%20Handouts%20.pdf Published online 10/22/. Accessed 10/29/2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Wit E., Feldmann F., Cronin J., Jordan R., Okumura A., Thomas T., Scott D., Cihlar T., Feldmann H. Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS-CoV infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:6771–6776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922083117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pardo J., Shukla A.M., Chamarthi G., Gupte A. The journey of remdesivir: from Ebola to COVID-19. Drugs in Context. 2020;9:1–9. doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]