Abstract

Intestinal transplantation (ITx) can be life-saving for patients with advanced intestinal failure experiencing complications of parenteral nutrition. New surgical techniques and conventional immunosuppression have enabled some success, but outcomes post-ITx remain disappointing. Refractory cellular immune responses, immunosuppression-linked infections, and post-transplant malignancies have precluded widespread ITx application. To shed light on the dynamics of ITx allograft rejection and treatment resistance, peripheral blood samples and intestinal allograft biopsies from 51 ITx patients with severe rejection, alongside 37 stable controls, were analyzed using immunohistochemistry, polychromatic flow cytometry, and reverse transcription-PCR. Our findings inform both immunomonitoring and treatment. In terms of immunomonitoring, we found that while ITx rejection is associated with proinflammatory and activated effector memory T cells in the blood, evidence of treatment efficacy can only be found in the allograft itself, meaning that blood-based monitoring may be insufficient. In terms of treatment, we found that the prominence of intra-graft memory TNF-α and IL-17 double-positive T helper type 17 (Th17) cells is a leading feature of refractory rejection. Anti-TNF-α therapies appear to provide novel and safer treatment strategies for refractory ITx rejection; with responses in 14 of 14 patients. Clinical protocols targeting TNF-α, IL-17, and Th17 warrant further testing.

1. Introduction

Tens of thousands of people in the US suffering from intestinal failure are managed with total parenteral nutrition (TPN), which is cumbersome, expensive, prohibitive to participation in day-to-day life (1) and associated with deadly complications, including parenteral nutrition associated liver disease, deep venous thrombosis, catheter-related sepsis, dehydration, and electrolyte disorders (2). As these complications progress or become recurrent (3, 4), patients require intestinal transplantation (ITx).

Unfortunately, even though ITx represents a life-saving and -enhancing option (5), it is presently only available to 10–15% of those on TPN (6). Consider that in 2019, of the approximately 25,000 Americans dependent on TPN, only 81 received ITx (7), while that same year more than 23,000 Americans got relief from dialysis via a kidney transplant (7). Moreover, the trend is moving in the wrong direction as ten years ago, nearly 200 ITx were performed per year. This begs two questions – why are transplant centers hesitant to perform ITx and what can be done about it?

The underutilization of ITx stems from high rates of rejection and treatment-related secondary complications (5). Since rejection is more common than with other solid organ transplants, higher levels of immunosuppression (IS) are utilized in general, while more than a third of ITx recipients require additional pulse steroids or T cell-depleting agents to treat rejection. This aggressive use of IS can lead to life-threatening secondary complications, such as infections, malignancies, and renal failure. As a result, the one- and five-year survival rates for ITx are low (77.2% and 50.5%, respectively) and lag behind those for liver (89.6% and 72.8%) and kidney (94.7% and 78.5%) transplants (5). These complications and sub-optimal survival rates lead to ITx being utilized only as salvage therapy for TPN failure or life-threatening complications, meaning that the vast majority of patients on TPN are not considered for ITx, and those who are face a limited probability of long-term success.

As conventional approaches to studying and treating intestinal rejection have fallen short, and the role of the resident microbiome renders the intestine as very different from other solid organs, a new approach is needed to reinvigorate ITx from the current plateau in success rates. We hypothesized that viewing ITx rejection through the lens of other intestinal inflammatory diseases could be a key to unlocking new insights into its mechanisms and treatment options.

We have recently demonstrated that ITx rejection has key features of severe intestinal inflammation not unlike severe inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) at both pathological and immunological levels (5). Pathologically, ITx rejection exhibits characteristics such as skip lesions, creeping fat, strictures, muscular fibrosis, and pseudopolyp formation. Immunologically, polymorphisms of nucleotide oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2), an intracellular sensor for muramyl dipeptide (MDP; also known as IBD protein 1), are associated with increased rates of immunological graft loss due to severe rejection in ITx (5, 8, 9). Moreover, NOD2 can mediate intestinal differentiation of T helper 17 cells (Th17) (5), which have an important role in autoimmune disorders (10) and in intestinal inflammation (11–13). These findings led us to hypothesize that Th17 cells may play an important role in ITx rejection.

Our results show that intra-graft Th17 cells are indeed a factor of treatment refractory rejection, and that targeting them via a tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) blocking approach might inform promising new treatment avenues for severe ITx rejection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study populations

This study received IRB approval (IRB studies #2004-008 and #2017-0365). Written informed consent was obtained prior to inclusion into the study. Ethical utilization of transplant organs and tissue abided by principles in the Declaration of Helsinki.

All patients studied received transplants between 2004 and 2019 at MedStar Georgetown Transplant Institute. Our study cohort was comprised of 88 transplant recipients (Table 2), 51 of whom were diagnosed with moderate to severe rejection based on clinical and pathological signs, and who are defined as “rejectors” for the purpose of this study. Specifically, we included rejection patients who experienced moderate to severe rejection between 2015 and 2019 from whom biospecimens for cellular and/or histological and immunological studies were available for analysis. Patients who experienced moderate to severe rejection between 2004 and 2014 were included if preserved tissue bank samples and/or immunological and other required data were available for analysis. Rejection patients with mild rejection or who did not receive treatment with thymoglobulin for moderate to severe rejection were excluded. Moreover, 18 rejectors who responded to thymoglobulin with clinical and pathological resolution were included in the “responder” cohort, 33 rejectors who failed thymoglobulin treatment were included in the “non-responder” cohort. Non-responsiveness was defined as persistent refractory rejection, or early recurrence within 90 days, or death or rejection-related explantation.

Table 2: Patient characteristics of total study cohort comprised of non-rejector controls and rejectors, and within the rejector cohort, responders and non-responders to thymoglobulin.

Table displaying patient characteristics of study cohorts of control and severe rejection groups, and among the severe rejection group the responder and non-responder groups as defined by: refractory rejection to standard therapy; recurrence within 90 days; and death or rejection-related explantation. P-values calculated as in Table 1.

| Total Study Cohort | Rejection Cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | Control (N=37) | Rejection (N=51) | P-value (vs. Control) | Responder (N=18) | P-value (vs. Control) | Non Responder (N=33) | |

| Age at Transplantation (N) | |||||||

| Adult | .31 | 20 | 33 | .62 | 11 | .28 | 22 |

| Pediatric | 17 | 18 | 7 | 11 | |||

| Sex (M / F) | .10 | 24 / 13 | 24 / 27 | .15 | 8 / 10 | .17 | 16 / 17 |

| Race / Ethnicity (N) | |||||||

| White | .33 | 22 | 25 | .78 | 10 | .24 | 15 |

| Black / African American | .64 | 11 | 18 | .31 | 8 | .98 | 10 |

| Other | .51 | 4 | 8 | .15 | 0 | .14 | 8 |

| Transplant Type (N) | |||||||

| Isolated Intestine | .66 | 23 | 34 | .39 | 9 | .22 | 25 |

| Combined Liver or Multi Visceral | 14 | 17 | 9 | 8 | |||

| Etiology (N) | |||||||

| Short Gut Syndrome | .41 | 29 | 36 | .35 | 12 | .58 | 24 |

| Motility / Malabsorption | .48 | 8 | 8 | .96 | 4 | .29 | 4 |

| Tumor | .08 | 0 | 4 | .15 | 1 | .06 | 3 |

| Other | .13 | 0 | 3 | .15 | 1 | .13 | 2 |

| Transplant Year (range) | 2005 – 2018 | 2004 – 2019 | 2004 – 2016 | 2004 – 2019 | |||

| Rejection after transplant (days) | |||||||

| Mean / Median | 622 / 243 | 709 / 484 | 575 / 231 | ||||

| NOD2 (N) | .55 | .18 | 1 | ||||

| WT / Mutant | 25 / 6 | 42 / 7 | 17 / 1 | 25 / 6 | |||

| Missing status | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| DSA (Y / N / not available) | |||||||

| Preformed | .34 | 0 / 30 / 7 | 1 / 32 / 18 | - | 0 / 11 / 7 | .24 | 1 / 21 / 11 |

| de novo | .008 | 12 / 24 / 1 | 25 / 14 / 12 | .01 | 10 / 4 / 4 | .04 | 15 / 10 / 8 |

| 1 -year / 3-year graft survival (%) | .13 / .03 | 95% / 87% | 84% / 65% | .32 / .52 | 100% / 94% | .02 / .0008 | 75% / 46% |

| 1 -year / 3-year patient survival (%) | .42 / .12 | 95% / 92% | 90% / 73% | .32 / .14 | 100% / 100% | .15 / .006 | 81% / 56% |

In terms of controls (“non-rejectors”), we included 37 demographically comparable control patients who survived at least two months post-transplant, who lacked clinical or pathological signs of rejection, and from whom biospecimens were available for analysis with freedom from systemic infection at the study timepoints.

Pre-operative, surgical, and post-operative care for all patients followed standard procedures as previously described (5, 8, 9, 14, 15). In terms of donor specific antibody (DSA) monitoring, preformed DSA were determined before transplantation at time of crossmatch testing and de novo DSA were monitored post-transplant weekly for 8 weeks, followed by monthly monitoring for 10 months.

IS and medical management were standardized and protocolized (8, 9, 15). Standard IS consisted of induction with IL‐2 receptor-α blockade (basiliximab) followed by maintenance IS of tacrolimus, sirolimus, and prednisone, as described in more detail in Supporting Materials and Methods. ITx recipients who were sensitized or underwent re‐transplantation or had a NOD2 mutant genotype received i.v. rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin®, Sanofi Genzyme, FDA ref#103869) for induction (1.5 mg/kg per day for 5 days) followed by standard maintenance IS.

Patients with moderate to severe allograft rejection received treatment with i.v. thymoglobulin (1.5mg/kg/day) for 10–14 doses or as clinically indicated. T cell depletion levels in peripheral blood were determined by daily CD3 counts via flow cytometry by the clinical laboratory. Prior to thymoglobulin treatment, i.v. steroid boluses (methylprednisolone, 20 mg/kg, maximum 1g) were given empirically in cases where biopsy results were still pending or other differential diagnoses were still being considered. Methylpredisolone i.v. (2 mg/kg, maximum 150 mg) was also administered as premedication before thymoglobulin infusion to prevent infusion-associated adverse reactions.

Infliximab (Remicade®, Janssen Biotech, Inc, FDA ref#4172269) was utilized following failure of thymoglobulin therapy as specified below, based on standard of care therapy for CD (5mg/kg/dose given immediately and again after 2 and 6 weeks; and as needed every 8 weeks until resolution of inflammation) (16).

Non-responders received infliximab if they met specific criteria, including no endoscopically visible improvement in rejection (or worsening/relapsing rejection) upon thymoglobulin treatment corroborated by histologic data, and/or for additional symptoms such as bleeding from the graft and severe enteric protein loss. Exclusion criteria included active or strongly suspected bacterial and fungal infection or viremia by PCR, or viral enteric or respiratory infection. Low grade fever after exclusion of above pathogens and in the absence of viral symptoms was not an exclusion criterium.

2.2. Blood and tissue sample collection

Blood samples were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes and processed same day for flow cytometric analysis. Mucosal biopsy samples from allografts were obtained from routine and for cause endoscopic biopsies (15) and processed same day for flow cytometry or saved as previously described for paraffin fixation (8, 9). Rejection samples from rejectors were obtained at the time of diagnosis of rejection or upon treatment with thymoglobulin. Control samples from non-rejectors with stable allografts without any evidence of rejection or infection were obtained during the first year of transplant or later follow up visits.

2.3. Isolation of lamina propria (LP) leukocytes and flow cytometry

Isolation of LP leukocytes and flow cytometric analysis was performed as described in Supporting Materials and Methods.

2.4. Peripheral blood flow cytometry analysis

Peripheral blood was collected and analyzed using flow cytometry as described in Supporting Materials and Methods. Blood leukocytes were profiled using the DuraClone® panel for T cell subsets (Beckman-Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer’s protocol (17).

2.5. RNA isolation and real-time PCR arrays

RNA isolation and real-time PCR arrays were performed as described in Supporting Materials and Methods.

2.6. H&E-histology and immunohistochemistry

Histology and immunohistochemistry were performed as described in Supporting Materials and Methods.

2.7. Statistics

Flow cytometry data were generated in counts or percentages. For each set, a violin plot showed kernel density, along with a box plot for interquartile ranges, and a jittered dot plot for data distribution. Demographic features were compared using Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test where appropriate. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was performed to compare counts in groups of interest, with Dunn’s multiple comparisons as needed. For percent data, Wilcoxon rank test was performed to compare groups of interest. All analyses were done in R software (https://www.r-project.org) or Prism 8 (Graphpad); the p-value of 0.05 was used as a threshold for significance of variance.

3. Results

Clinical outcomes

Table 1 shows that of 264 ITx recipients – who our center transplanted between 2004 and 2019 – nearly half (N=130) experienced at least one rejection episode. Rejection rates were less frequent for patients who received a combined liver or multi-visceral transplant. One- and 3-year allograft survival was 85% and 65% in the rejection group compared to 88% and 75% in the control group. One- and 3-year patient survival was 87% and 69%, respectively, as compared to 89% and 76% for non-rejectors; indicating that rejection is associated with inferior long-term outcomes.

Table 1: Patient characteristics of all ITx patients and among rejection patients.

Table displaying total ITx patient characteristics, including details for the mild rejection and moderate-severe rejection group compared against the control group. P-values calculated using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate.

| Total Population | Rejection Population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | Control (n=134) | Rejection (n=130) | P-value (vs control) | Mild Rejection (n=44) | P-value (vs control) | Moderate-Severe Rejection (n=86) | |

| Age at Transplantation (N) | .0002 | .003 | .002 | ||||

| Adult | 54 | 82 | 29 | 53 | |||

| Pediatric | 80 | 48 | 15 | 33 | |||

| Sex (Male / Female) (N) | .028 | 83 / 51 | 63 / 67 | .029 | 19 / 25 | .11 | 44 / 42 |

| Race/Ethnicity (N) | |||||||

| White | .26 | 68 | 75 | .08 | 29 | .69 | 46 |

| Black/African American | .28 | 42 | 33 | .09 | 8 | .72 | 25 |

| Other | .83 | 24 | 22 | .76 | 7 | .93 | 15 |

| Transplant Type (N) | .055 | .22 | .075 | ||||

| Isolated Intestinal Transplant | 71 | 84 | 28 | 56 | |||

| Combined Liver or Multi Visceral Transplant | 63 | 46 | 16 | 30 | |||

| Etiology (N) | |||||||

| Short Gut Syndrome | .51 | 93 | 95 | .19 | 35 | .95 | 60 |

| Motility / Malabsorption | .15 | 31 | 21 | .31 | 7 | .22 | 14 |

| Tumor | .36 | 5 | 8 | .64 | 1 | .16 | 7 |

| Other | .72 | 5 | 6 | .64 | 1 | .47 | 5 |

| 1-year / 3-year graft survival (%) | .42 / .079 | 88% / 75% | 85% / 65% | .76 / .56 | 86% / 71% | .36 / .056 | 84% / 63% |

| 1 -year / 3-year patient survival (%) | .61 / .24 | 89% / 76% | 87% / 69% | .65 / .68 | 86% / 73% | .69 / .18 | 87% / 68% |

A closer look at the 130 rejectors revealed further nuance depending on the severity of rejection (Table 1). The 44 ITx recipients who experienced only mild rejection saw similar graft and patient outcomes as non-rejectors. But the 86 ITx recipients who experienced at least one episode of moderate to severe rejection, necessitating aggressive T-cell depleting therapy, saw the lowest graft and patient outcomes of the whole cohort. Our data thus confirm that severe ITx rejection is associated with increased graft loss and patient death, due to poor responsiveness to aggressive immunosuppressive therapy or associated complications (5, 15).

To further analyze rejection and treatment response of severe ITx rejection, we studied alloreactive T cell responses in a representative study population of 51 ITx recipients with moderate to severe rejection (“rejectors”) in comparison to 37 control patients (“non-rejectors”), based on exclusion and inclusion criteria detailed in Materials and Methods (Table 2). Supplemental Figures 1A and 1B show representative clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of severe ITx rejection.

The 51 rejectors were further categorized as thymoglobulin treatment “responders” (N=18) and “non-responders” (N=33). Of note, only three patients in the control group and three non-responders in the rejection group had a history of IBD. Moreover, there was no difference in NOD2 genotype status between rejectors and non-rejectors (Table 2). However, rejectors were more likely to develop de novo DSAs than non-rejectors (Table 2). Notably, only the 33 non-responders had worse 1- and 3-year graft and patient survival rates versus non-rejectors, highlighting the importance of treatment responsiveness for the prognosis of severe ITx rejection. Of note, there was a trend towards better patient and allograft survival in our study cohort (Table 2) when compared to our total patient cohort (Table 1), which is likely due to overall improved outcomes in the current era (15), as more study patients were transplanted in the last decade.

Blood sample analyses

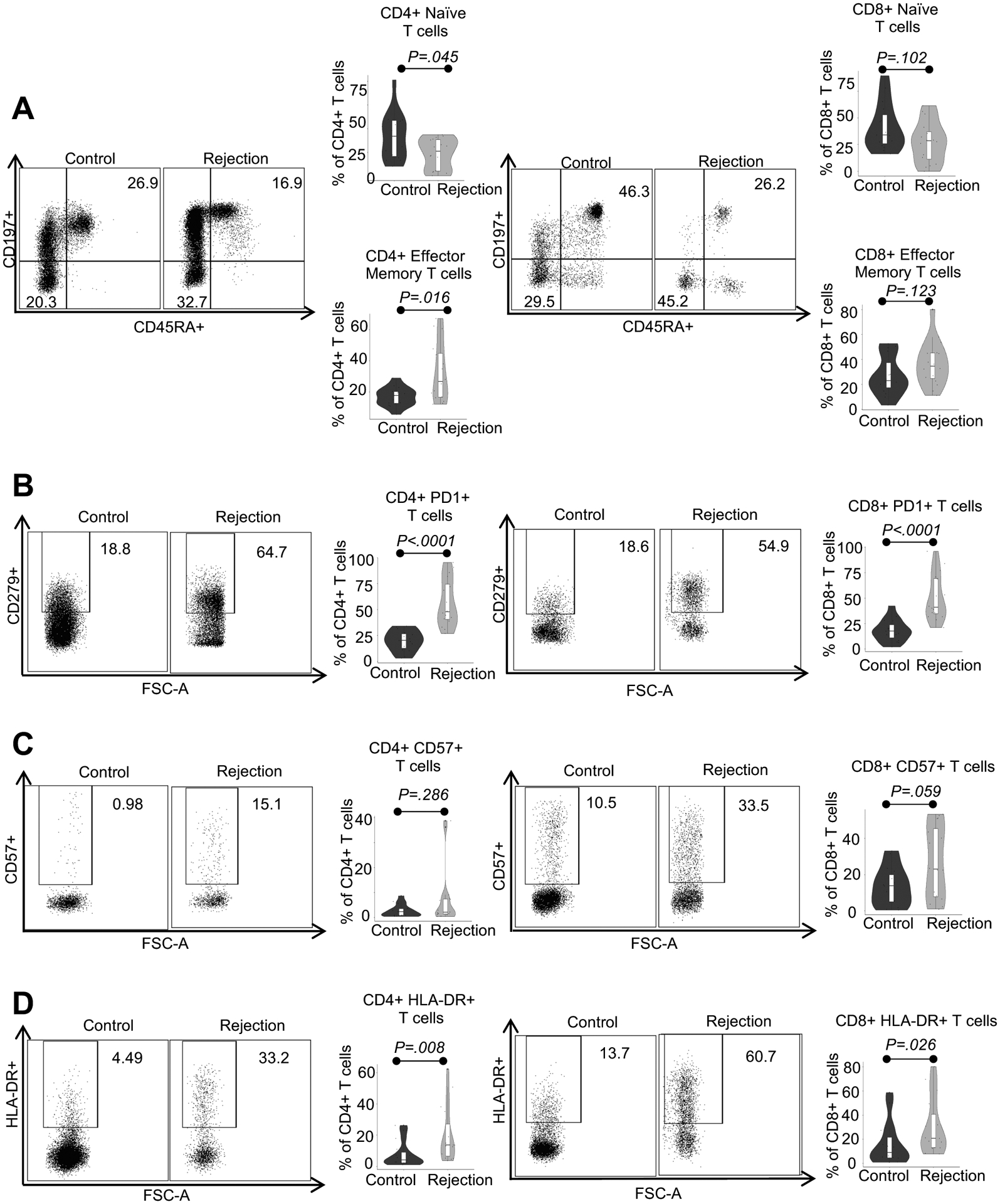

As acute rejection in solid organ transplantation is primarily driven by alloreactive T cell responses (18), we first used polychromatic flow cytometry to study the immunophenotype of T cells in peripheral blood of rejectors at the time of rejection diagnosis. As shown in Supplemental Figures 2A and 2B, we found comparable frequencies of total CD3+ T cells as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the blood of rejectors versus non-rejectors. Importantly as shown in Figure 1A, we found higher frequencies of effector memory CD4+ T cells and less naïve CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of rejectors at the time of rejection diagnosis when compared to non-rejectors.

Figure 1:

Characterization of peripheral blood T cells from ITx patients with severe rejection (rejector) at the time of rejection diagnosis versus stable controls (non-rejector) via polychromatic flow cytometry. A, B, C, and D) Representative flow plots of alterations in CD4+ (left column) and CD8+ (right column) T cell subpopulations in peripheral blood of non-rejector control versus rejector patients. Violin plots for naive (CD197+CD45RA+), effector memory (CD197-CD45RA), and PD-1, CD57, and HLA-DR expressing subpopulations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Statistics by Wilcoxon rank sum testing. Sample size for all four panel groups is control n=15, rejection n=16.

Further subset analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells revealed greater expression of markers of activation, antigen experience, and terminal differentiation including programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and HLA-DR (Figures 1B–D) in rejectors at the time of rejection diagnosis when compared to non-rejectors.

In terms of chemokine receptor (CCR) expression and T cell polarization, we found comparable frequencies of CCR6-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as IL-17 producing CCR6+CD4+ Th17 cells and CCR6+CD8+ cytotoxic T (Tc17) cells in peripheral blood of rejectors at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-rejector controls (Supplemental Figure 3A).

In sum, our blood immunomonitoring results show that ITx rejection patients possess an immunophenotype that is predominated by proinflammatory and activated T cells with effector memory phenotype.

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that activated memory T cells in blood resist depletion with thymoglobulin treatment, thereby contributing to treatment-refractory severe rejection in non-responders. To our surprise, however, as shown in Figure 2A, flow cytometry revealed almost no viable CD3+ T cells in peripheral blood of rejectors with active rejection on thymoglobulin when compared to pre-treatment rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis and non-rejector control samples.

Figure 2:

Uniform depletion of circulating CD3+ T cells from the peripheral blood of ITx patients with severe rejection during treatment with thymoglobulin. A) Representative flow plots and violin plots of peripheral blood CD3+ T cells in non-rejector control, rejector at the time of rejection diagnosis, and thymoglobulin-treated rejector patients. Statistics by Kruskal-Wallis rank testing with individual group comparisons by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size is Control n=15, Rejection n=16, Rejection on thymo n=9. B) Violin plot of histologic scoring done by a pathologist for biopsies at the time of rejection and 40–90 days post treatment with thymoglobulin in both responders and non-responders. Scoring system defined as 0=no rejection, 1=borderline rejection, 2=grade 1 rejection, 3=grade 2 rejection, 4=grade 3 rejection as per pathology consensus guidelines (41). Statistics by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for responder graph is n=18 for both time points, for non-responder graph n=26 at both time points. C) Violin plot of lowest measured percent peripheral blood CD3+ T cell frequencies demonstrating near complete depletion in both responder and non-responder rejection patients on thymoglobulin. Statistics by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size is responder n=17, non-responder n=24.

Specifically, we found CD3+ T cell populations uniformly depleted in peripheral blood of both responders and non-responders (Figure 2B) with active rejection on thymoglobulin treatment (Figure 2C), indicating that monitoring CD3+ T cell populations in peripheral blood, which is currently the clinical gold standard in patients on thymoglobulin, is unreliable for ITx patients and fails to correlate with treatment responsiveness.

Graft biopsy analyses

Based on this insight, we speculated that thymoglobulin-resistant allograft rejection is driven by compartmentalization with thymoglobulin-depletion-resistant T cells within the allograft itself, rather than in the blood. To test this, we performed serial immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies in our rejector cohort at the time of rejection diagnosis and upon thymoglobulin treatment to characterize the CD3+ T cell compartment kinetics in LP of rejecting allografts. As shown in Figure 3A, we found significantly higher numbers of CD3+ T cells in grafts from rejectors at the time of rejection diagnosis compared to non-rejector controls.

Figure 3:

Acute allograft rejection characterized by CD3+ T cell infiltration and poor clinical outcome and associated with a failure to deplete the allograft during thymoglobulin treatment. A) Representative IHC staining for CD3+ T cells in LP of graft biopsies from non-rejector control and rejector patients at the time of rejection diagnosis. Violin plot of CD3+ T cells counted per 5 high-power fields (20x magnification) demonstrating difference in frequencies in non-rejector control and rejector patients at the time of rejection diagnosis. Statistics performed by Wilcoxon rank test. Sample size is control n=34, rejection n=42. B) Representative IHC for CD3+ T cells in LP of graft biopsies from responders versus non-responders treated with thymoglobulin. Violin plot of CD3+ T cell counts in ITx biopsy samples from non-rejector control as well as responder and non-responder rejection ITx samples before (at the time of rejection diagnosis) and after thymoglobulin treatment, respectively. Statistics performed using Kruskal-Wallis rank test with individual group comparisons with Wilcoxon rank tests. Sample size is control n=34, responders pre and post thymo n=18, non-responders pre and post thymo n=24. C) Violin plot of percent CD3+ T cell depletion levels (left) and total thymoglobulin dose (defined as daily thymoglobulin dose divided by weight multiplied by number of days of treatment mg*days/kg) in responders versus non-responders. Statistics with Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for CD3+ T cell depletion levels is responder n=18, non-responder n=24. Thymo dose sample size is n=17 for responders, n=24 for non-responders.

Moreover, we detected significantly lower numbers of CD3+ T cells in rejecting grafts from both responders and non-responders upon thymoglobulin treatment (Figure 3B). Further analysis revealed that the degree of CD3+ T cell depletion in the allograft more closely correlated with responsiveness to thymoglobulin, as CD3+ T cell depletion levels in thymoglobulin-treated grafts were significantly higher in responders than in non-responders (left side of Figure 3C). Importantly, the observed difference in T cell depletion levels between responders and non-responders was independent of cumulative weight-adjusted thymoglobulin doses (right side of Figure 3C).

Based on these findings, we next used flow cytometry to characterize the precise immunophenotype of T cells in allografts of non-responder rejectors both at the time of rejection diagnosis and on thymoglobulin treatment. In line with our IHC data (Figure 3B), we found higher frequencies of total CD3+ T cells in allografts of non-responder patients at the time of rejection diagnosis versus on thymoglobulin treatment (Supplemental Figure 2C). Moreover, we found comparable frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in allografts of non-rejectors versus non-responder patients with active rejection both at the time of rejection diagnosis and on thymoglobulin (Supplemental Figure 2D).

In terms of memory phenotype, as expected, we detected predominantly CD4+ and CD8 + T cells with CD45RO+ effector memory phenotype in allografts of non-rejectors (Figure 4A), consistent with previous studies (19). Non-responder rejector allografts harbored higher frequencies of CD45RO- terminally differentiated effector memory CD4+ and CD8 + T cells and fewer CD45RO+ effector memory CD4+ and CD8 + T cells at the time of rejection diagnosis and upon treatment with thymoglobulin when compared to non-rejectors (Figure 4A). This was again re-demonstrated upon mean fluorescence index analysis for CD45RO in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Figure 3B).

Figure 4:

Predominance of terminally differentiated effector memory T cells and CCR6+CD4+ T cells in severe refractory rejection despite thymoglobulin treatment. A) Representative flow plots of alterations in CD4+ (upper row) and CD8+ (lower row) T cell subpopulations including effector memory (CD45RO+CD62L-) and terminally differentiated effector memory (CD45RO-CD62L-) cells in intestinal graft biopsies from non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin; followed by violin plots of individual values of CD4+ (upper row) and CD8+ (lower row) subgroups as previously described. Sample size for both CD4+ and CD8+ effector memory and terminally differentiated effector memory is control n=20, rejection n=9, rejection on thymo n=12. B) Representative flow showing enhanced number of CCR6+CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in intestinal biopsies from non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin; followed by violin plots of individual values representing comparative analysis of CCR6+CD4+ and CCR6+CD8+ T cell subgroups in non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin, respectively. Statistics performed using Kruskal-Wallis rank testing with individual group comparisons by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for CCR6+ CD4+ and CD8+ is control n=20, rejection n=9, rejection on thymo n=14.

In terms of chemokine expression, we further found that in comparison to non-rejectors, there were higher frequencies of CCR6-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in rejecting non-responder allografts both at the time of rejection diagnosis and upon treatment with thymoglobulin (Figure 4B).

In sum, we found a phenotypic shift from effector memory to terminally differentiated effector memory CCR6+ T cells in non-responder rejectors versus non-rejectors, which was particularly strong in CD4+ T cells in rejecting allografts of non-responders during thymoglobulin treatment (Figure 4B), indicating that CCR6-expressing CD4+ T cells with predominantly terminally differentiated effector memory phenotype persist during depletion treatment with thymoglobulin.

Thus, based on our hypothesis on the role of Th17 cells in rejection, we asked whether the CCR6+ T cell population that persists in allografts of non-responder rejectors before and during thymoglobulin treatment are proinflammatory TNF-α and IL-17 producing Th17 cells, which is the phenotype seen in other intestinal inflammatory diseases (11). To test this hypothesis, we used intracellular cytokine staining upon re-stimulation with PMA/ionomycin ex vivo to determine the cytokine expression profile of intra-graft T cells from non-responder ITx patients with active rejection and thymoglobulin treatment.

We found a strong increase in frequencies of total IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells and, more specifically, CCR6+CD4+ Th17 cells in non-responder rejectors versus non-rejectors (Figure 5A upper row). We also found that only a small fraction of CD8+ T cells produced IL-17 in non-responder rejection samples with minor differences in frequencies of IL-17 producing CD8+ T cells or CCR6+CD8+ T cells between non-responder rejectors and non-rejectors (Supplemental Figure 4A). This indicates that CCR6+CD4+ Th17 and not CCR6+CD8+ Tc17 cells are the major IL-17-producing effector population in ITx allograft rejection. Importantly, we also detected higher frequencies of TNF-α producing CD4+ T cells and CCR6+CD4+ T cells in actively rejecting allografts from non-responders when compared to non-rejectors (Figure 5A). Further subset analysis demonstrated that the clear majority (mean 85%) of IL-17 producing CCR6+CD4+ Th17 cells in actively rejecting allografts from non-responders co-express pro-inflammatory TNF-α (Supplemental Figure 4B).

Figure 5:

Cytokine production by CCR6+CD4+ Th17 cells highlighting their pro-inflammatory phenotype in severe refractory allograft rejection. Transcriptome activation of cytokine, chemokine, and transcription factor Th17 related genes in rejection patients at the time of rejection diagnosis as defined by RT-PCR. A) LP CD4+ T cells isolated from non-rejector control and non-responder rejection graft biopsy samples during active rejection on treatment, stimulated with PMA/ionomycin and subsequently analyzed for intracellular IL-17, TNF-α, and CCR6 expression. Representative flow plots showing CD4+CD3+ gated populations exhibited intracellular cytokines IL-17 and TNF-α predominantly in the CCR6+ T cell populations; followed by violin plots of individual values representing comparative analysis of cytokine-expressing CCR6+CD4+ T cell subpopulations versus total cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells in non-rejector control versus non-responder rejection patients. Statistics performed using Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for IL-17 producing CCR6+CD4+ group is control n=10, rejection n=11; for IL-17 CD4+ group control n=10, rejection n=11; for TNF-α CCR6+CD4+ control n=7, rejection n=11; TNF-α CD4+ control n=7, rejection n=11. B and C) Gene expression analysis on intestinal graft biopsies from non-rejector controls versus pre-rejection controls versus rejection patients at rejection diagnosis. Heat map visualization of pathway-focused panel for Human Th17 Response depicting normalized fold change 2−ΔΔCt of genes exhibiting significant difference in expression on a magnitude of log2 scale. All cycle threshold values normalized to GAPDH values and log transformed. Sample size for heatmap is control n=13, pre-rejection control n=13, rejection n=13.

These results suggested that CCR6+CD4+ Th17 cells participate in ITx rejection via release of IL-17 and TNF-α, both of which have been shown to induce a potent, proinflammatory cascade in other intestinal inflammatory diseases (20).

To address this, we studied the transcriptome of ITx biopsy samples from recipients with ongoing severe rejection compared to baseline pre-rejection and non-rejection controls via a real-time PCR array for Th17 responses. We found at a transcriptional level an overexpression of the Th17-related transcriptome in severe rejection patients when compared to controls (Figures 5B and 5C; Supplemental Table 1). Specifically, we found a significant overexpression of 37 out of 88 genes, including important Th17-related transcription factors (e.g., CEBPB, Runx1, ROR-α), cytokines/chemokines (e.g., CSF-3, CXCL1, CXCL2, IL-21, IL-23A, CCL20, TNF-α) and receptors (e.g., IL1R1, IL17RA, CLEC7A) in rejectors versus controls (Figures 5B and 5C; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

In sum, these results suggest that IL-17 and TNF-α producing CCR6+ Th17 cells play a critical role in ITx rejection by inducing a potent pro-inflammatory Th17 response (21). Based on these findings, we speculated that thymoglobulin non-responders might be salvaged through targeted treatment against pro-inflammatory Th17 responses. We used infliximab because it has been successfully used for treatment of steroid-refractory Crohn’s disease (CD) for more than 10 years (22), safely used in ITx patients for treatment of chronic rejection and inflammation at our and other centers including in Berlin, Germany (23), and shown to specifically target TNF-α producing cells and thus likely to deplete IL-17 and TNF-α double-producing CCR6+ Th17 cells – the major effector T cell population in the rejectors. (Figure 5A, Supplemental Figure 4B).

Table 3 shows the demographics of 14 non-responder ITx recipients who received infliximab for refractory severe rejection after failing thymoglobulin treatment in comparison to 14 non-responder ITx recipients who only received thymoglobulin. The latter group exhibited little to no endoscopic and histologic improvement either at 6 weeks after rejection diagnosis or at the time of early rejection relapse (Figures 6A and 6B). Conversely, all of the 14 infliximab patients experienced recovery from thymoglobulin refractory rejection (Figures 6A and 6B). Specifically, we found significant improvements in clinical endoscopy scores at 6 weeks after infliximab treatment compared to the time of rejection diagnosis and thymoglobulin failure (Figure 6A), confirmed by histologic resolution of rejection between 19 and 271 days (Table 3) after infliximab initiation. We also found additional improvements in histologic rejection scores 6 weeks after infliximab initiation, when compared to the time of initial rejection diagnosis and kinetics of failed thymoglobulin treatment completion (Figure 6B). Most importantly, from an outcome perspective, patients who were treated with infliximab saw higher 1- and 3-year survival rates (Table 3).

Table 3: Patient characteristics of severe rejection nonresponder patients receiving thymo + infliximab versus thymo only (no infliximab).

Table displaying patient characteristics of severe rejection non-responder patients receiving thymoglobulin and infliximab versus those receiving thymoglobulin only (and no infliximab). P-values calculated as in Table 1.

| Non-responder/Thymo+ Infliximab Patients | Non-responder/Thymo only Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | (n=14) | (n=14) | |

| Age at Transplantation (N) | .005 | ||

| Adult | 6 | 13 | |

| Pediatric | 8 | 1 | |

| Sex (Male / Female) (N) | .45 | 7 / 7 | 9 / 5 |

| Race / Ethnicity (N) | |||

| White | .06 | 4 | 9 |

| Black / African American | .09 | 6 | 2 |

| Other | .66 | 4 | 3 |

| Transplant Type (N) | .40 | ||

| Isolated Intestinal Transplant | 9 | 11 | |

| Combined Liver or Multi Visceral Transplant | 5 | 3 | |

| Etiology (N) | |||

| Short Gut Syndrome | 1 | 10 | 10 |

| Motility / Malabsorption | .07 | 3 | 0 |

| Tumor | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | .07 | 0 | 3 |

| Year of Transplant (range) | - | 2007–2018 | 2004–2017 |

| NOD2 (N) | .23 | ||

| WT | 11 | 8 | |

| Mutant | 3 | 6 | |

| Rejection time to first dose of infliximab (days) | Not applicable | ||

| Mean | 39 | ||

| Range | 7–141 | ||

| Time after infliximab until histological resolution (days) | Not applicable | ||

| Mean | 67 | ||

| Range | 19–271 | ||

| 1-year / 3-year graft survival (%) | .03 / .001 | 93% / 82% | 57% / 15% |

| 1-year / 3-year patient survival (%) | .14 / .01 | 93% / 82% | 71% / 31% |

Figure 6:

Significant histologic and endoscopic improvement in severe rejection patients recalcitrant to thymoglobulin when treated with infliximab. A) Representative endoscopic images of clinical non-responders at the time of untreated acute cellular rejection, at the time of initiation of infliximab after failure of thymoglobulin depletion therapy, and 6 weeks after first dose of infliximab. Violin plots of standardized clinical endoscopy scores from 14 non-responder ITx recipients who received infliximab for refractory severe rejection after failing thymoglobulin treatment in comparison to 14 non-responder ITx recipients who only received thymoglobulin; scores incorporate features of ulcer size, total ulcerated surface area, affected surface area, and the presence of strictures impeding endoscope passage. Scoring mechanisms described in reference (13). B) Representative images of intestinal biopsy histologic H&E stains at 10x magnification/zoom 60x performed on non-responders at the same three time points as in Figure 6A. Violin plots comparing histologic scoring of the same patient cohorts and time points described in Figure 6A done by transplant pathologist with scoring system described in Figure 2B. Statistics by Kruskal Wallis rank sum testing with Dunn’s post hoc multiple comparisons and Wilcoxon rank test for both A) and B). Sample size for non-responder ITx recipients treated with infliximab is time of rejection n=14, time of thymo failure n=14, 6 weeks after infliximab n=14. Sample size for non-responder ITx recipients who only received thymoglobulin is time of rejection n=14, 6 weeks after thymoglobulin/relapse n=14.

In short, we successfully induced endoscopic and histologic resolution in refractory ITx rejection in 14 out of 14 patients who failed initial treatment with thymoglobulin, via a TNF-α blocking approach with infliximab. These results suggest that ITx recipients with severe rejection, who fail treatment with thymoglobulin, could benefit from a targeted treatment approach against TNF-α in the context of Th17 induced inflammatory responses.

4. Discussion

The intestine is the body’s largest reservoir of immune cells, facing constant bombardment by intrinsic and extrinsic stressors such as the microbiome that complicate immune temperance. Thus, immunomonitoring and treatment algorithms derived from less lymphoid solid organs may not serve adequately as models for ITx rejection.

Regarding immunomonitoring, our data suggest the importance of measuring alloreactive T cell responses to treatment within the allograft itself, and not (just) in blood. Specifically, while we observe that in ITx rejection, there is upregulation of circulating PD-1+ and HLA-DR+ CD4+ memory T cells in blood (19, 24–26) at the time of rejection diagnosis, these cells rapidly deplete upon initiation of thymoglobulin, potentially (mis)signaling drug efficacy. While thymoglobulin has potent effects through a variety of pathways inclusive of complement-dependent lysis, apoptosis, and modulation of adhesion molecules, our results confirm that the ability to deplete T cells in grafts is drastically different from peripheral blood (27). While allografts of thymoglobulin treatment responders show better T cell depletion than those of non-responders despite comparable doses of treatment, the latter also contain a substantial population of proinflammatory terminally differentiated memory Th17 cells.

This Th17 cell population in non-responders appears to be resistant to traditional mechanisms of depletion. Since we cannot rule out that Th17 cells also play a role in rejection in eventual responders, it raises the question of whether there are Th17 clones that are differentially depletable. We hypothesize several potential causes for such depletion resistance, including a disproportionally lower level of available complement in the graft, an impairment of antibody dependent cytotoxicity in rejecting grafts, and an upregulation of survival molecules and protective factors such as BCL-2 and BCL-XL, which has been described in depletion-resistant T cells (28). Due to these inherent limitations, we propose a change from peripheral blood monitoring to immunomonitoring of T cells in the transplanted intestine itself.

Regarding treatment, our finding that intra-graft Th17 cells are indeed a critical factor of severe rejection uncover new avenues for therapeutic treatment. Importantly, the IL-17/IL-23 axis and Th17 cells have been implicated as critical causes of intestinal inflammation in autoimmunity and graft versus host disease (GVHD) (11, 29). For instance, polymorphisms in the IL-23 receptor gene were found to confer a decreased susceptibility to CD (13) as well as protective effects on GVHD if the donor has the polymorphism (30, 31). Additionally, increased levels of Th17 cells and an increased expression of IL-17 and IL-23 have been found in CD lesions and in the intestinal mucosa of patients with gastrointestinal GVHD (32).

From a mechanistic standpoint, production of IL-17 by Th17 cells induces granulopoiesis with a polymorphonuclear dominated infiltration of the allograft, which is a pathological hallmark of intestinal rejection (Supplemental Figure 1B). Validation of this hypothesis was seen in the linked mRNA data, as there was a significant increase in neutrophilic chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2, as well as granulocyte factor CSF3 in rejectors compared to non-rejectors.

If depletion resistant ITx rejection is mediated by cytokine producing effector Th17 cells, specifically targeting TNF-α and IL-17 double-producing cells through anti-TNF- α therapy would be a reasonable treatment strategy – as we were able to show in 14 out of 14 patients for whom traditional therapy failed but infliximab worked. Infliximab, which uses precisely this mechanism, remains a staple in the clinical armamentarium of physicians treating severe intestinal inflammation in autoimmunity and GVHD (33). Mechanistically, infliximab specifically targets and induces the apoptosis of T lymphocytes within the LP and peripheral blood through a variety of pathways (34–36). As we have shown, the cell subset of terminally differentiated memory Th17 cells that persists in the allograft of severely rejecting patients strongly co-expresses both IL-17 and TNF-α and is resistant to depletion through thymoglobulin. This co-expression offers a potential target for direct binding and caspase 3 mediated apoptosis of these cells, which may resist traditional complement-activated methods of depletion (34).

Utilization of anti TNF-α agents for the treatment of ITx rejection has been previously described by the Berlin group (23); however, while there have been several dozen case reports, a mechanistic explanation has been lacking.

Although we cannot rule out additive anti TNF-α effects of steroids in our study, our observed efficacy of infliximab treatment in patients with severe allograft rejection refractory to treatment could also be related to more specific mechanisms of targeting Th17 cells via TNF-α inhibition. These have been described and include blockade of RORγt, the lineage defining transcription factor for Th17 cells (37), as well as overall inhibition of IL-17 and TNF-α production in both activated CD4+ cells but specifically polarized Th17 cells (38). These mechanisms have been established in autoimmune models. While the Th17 cell is critical in intestinal (10, 12) and pulmonary immunity (39), the overactivation of these cells may be the hallmark of both allograft rejection and autoimmunity in both organ systems. Relatedly, given the regulatory role of IL-17 producing Th17 cells for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, a complete blockage of the IL-17 axis via an anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody approach – which infliximab is not – may be ineffective or even exacerbate complications as has previously been shown in CD (40).

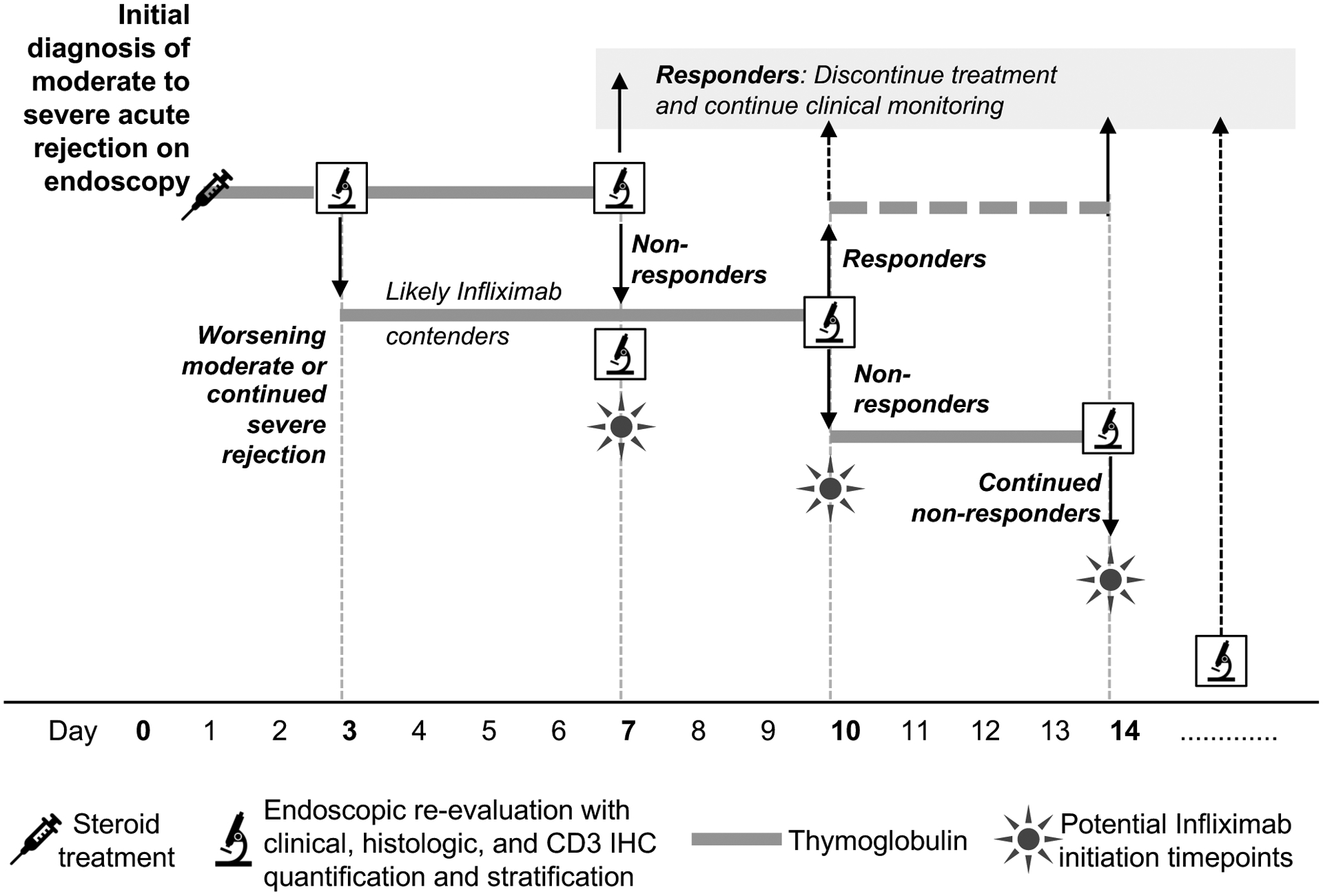

Overall, based on our findings, we propose adapting clinical management of severe ITx rejection in two key ways: first, to adopt distinctive allograft immunomonitoring rather than relying only on blood monitoring, and second to conduct trials with infliximab, based on having identified IL-17 and TNF-α producing memory Th17 cells in the graft as key culprits in rejection refractory to traditional therapy. For moderate to severe rejection anti-TNF-α therapy could be given if 1) the rejection continues to be severe, 2) an initially moderate rejection worsens, or 3) thymoglobulin is not working. As a result, we propose a new treatment algorithm for ITx recipients with moderate to severe rejection based on our own current practice (Figure 7) which adds infliximab at one of several potential key stage gates of diagnosis and treatment. The durability of such a treatment algorithm must be confirmed over time. If it is, pre-emptive transplants for people dependent on lifelong TPN might become the standard as they have for dialysis-dependent kidney failure.

Figure 7:

Proposed clinical algorithm for treatment of moderate or severe acute rejection. At the time of initial diagnosis of moderate to severe rejection, we recommend not only clinical and gross histologic examination but also CD3 IHC quantification. Once patients are treated with high-dose steroids and / or three days of thymoglobulin, we recommend a reassessment to determine progress. Those with worsening or continued severe rejection are likely contenders for infliximab. Starting at day 7, if endoscopic and histologic assessment show lack of improvement (i.e. no treatment response) infliximab could be given. A similar reassessment is performed at 10 days with responders either finishing out a 14-day course of thymoglobulin or stopping at day 10, and non-responders continuing to receive thymoglobulin up to 14 days. If infliximab was not initiated at day 7, it could be initiated at day 10 or 14. The non-responder group would undergo continuous monitoring and additional doses of infliximab could be administered as clinically indicated.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. A) Operative photographs of small bowel resection specimens from ITx patient with acute cellular rejection demonstrating mesenteric fat creeping, hyperemia with structuring, and upon sectioning the presence of cobblestoning inflammation, all reminiscent of patterns found in CD. B) Representative histologic sections at 10x magnification with zoom window at 60x with H&E stains as well as endoscopic images demonstrating the differences in uncomplicated transplant patients and those with severe acute cellular rejection and inflammatory manifestations.

Supplemental Figure 2: Proportions of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells in the peripheral blood and allograft of intestinal transplant patients in non-rejector control and active rejector patients at the time of rejection diagnosis and on treatment. A and B) Representative flow plots and violin plots of individual values of CD3+ as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations from peripheral blood samples gated on viable CD45+ lymphocytes and CD3+ T cells, respectively in non-rejector control versus rejector patients at the time of rejection diagnosis. Statistics performed with Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for both CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ is control n=15, rejection n=16. C and D) Representative flow plots showing alterations in CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in intestinal graft biopsies from non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin. Violin plots of individual values representing the percentage of CD3+ T cells of viable lymphocytes and of CD4+ and CD8+ cells of CD3+ T cells in non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin, respectively. Statistical testing performed using Kruskal-Wallis rank test with Wilcoxon rank tests for individual group comparisons. Sample size for CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ is control n=20, rejection n=10, rejection on thymo n=14.

Supplemental Figure 3: CCR6 and IL-17 expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes and CD45RO cytokine mean fluorescence in graft biopsies. A) Representative flow and violin plots of peripheral blood CCR6 and IL-17 expression in CD4 and CD8 T cells in non-rejector controls and severe rejectors at the time of rejection diagnosis. Statistics by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample sizes for CD4+ CCR6+ T and Th17 cells are control n=10, rejection n=13; for CD8+ CCR6+ T and Tc17 cells are control n=10, rejection n=13. B) Violin plots of CD45RO mean fluorescence index in CD4 and CD8 T cells in non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin, respectively. Statistics by Kruskal-Wallis rank testing with individual groups comparison by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size is control n=20, rejection n=9, rejection on thymo n=12.

Supplemental Figure 4: Cytokine expression of Tc17 cells and predominance of TNF-α production in IL-17 producing CD8+CCR6+ Tc17 cells in severe refractory allograft rejection. A) LP CD8+ T cells isolated from non-rejector control and non-responder rejection graft biopsy samples during active rejection on treatment, stimulated with PMA/ionomycin and subsequently analyzed for intracellular IL-17, TNF-α, and CCR6 expression. Representative flow plots showing CD8+CD3+ gated populations exhibited intracellular cytokines IL-17 and TNF-α predominantly in the CCR6+ T cell populations; followed by violin plots of individual values representing comparative analysis of cytokine-expressing CCR6+CD8+ T cell subpopulations versus total cytokine-expressing CD8+ T cells in non-rejector control versus non-responder rejection patients. Statistics with Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for IL-17 CCR6+CD8+ is control n=10, rejection n=11; for IL-17 CD8+ control n=10, rejection n=11; for TNF-α CCR6+CD8+ control n=7, rejection n=11; for TNF-α CD8+ control n=7, rejection n=11. B) Representative flow cytometry of co-expression of IL-17 and TNF-α in actively rejecting allografts from non-responder rejection patients demonstrating a mean 85% of CCR6+CD4+ cells expressing IL-17 also expressing TNF-α. Violin plot showing mean expression. Sample size is n=11 for both groups.

Supplemental Table 1 & 2. Tables showing comparisons of genes between pre-rejection control, healthy control, and rejection patients with reported standard deviations in fold expression as well as the raw, adjusted p values and false discovery rate. All genes displayed regardless of significance. Group A is pre-rejection control patients (Supplemental Table 1) as defined as the most recent normal tissue sample prior to a diagnosis of rejection, or healthy control (Supplemental Table 2) and Group B is rejection patients at the time of rejection diagnosis. Sample size is control n=13, pre-rejection control n=13, and rejection n=13.

Acknowledgments

AK, SCR, MZ, and TMF acknowledge funding support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI132389). The authors thank Valerie Bockstette for critical review of the manuscript. The authors thank all coordinators, research associates, and assistants who were involved in this project for their technical contributions.

Abbreviations:

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CCR

chemokine receptor

- CD

Crohn’s Disease

- DSA

Donor specific antibody

- GVHD

graft versus host disease

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IS

immunosuppression

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- ITx

intestinal transplantation

- LP

lamina propria

- MDP

muramyl-dipeptide

- NOD2

nucleotide oligomerization binding domain-2

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- Tc17

cytotoxic T cell

- Th17

T helper type 17 cells

- TPN

total parenteral nutrition

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

List of provided supporting information:

Supplemental Figures 1–4

Supplemental Tables 1&2

Supporting Materials and Methods

References

- 1.Allan P, Lal S. Intestinal failure: a review. F1000Res 2018;7:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchman AL, Scolapio J, Fryer J. AGA technical review on short bowel syndrome and intestinal transplantation. Gastroenterology 2003;124(4):1111–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beath S, Pironi L, Gabe S, Horslen S, Sudan D, Mazeriegos G et al. Collaborative strategies to reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic intestinal failure including those who are referred for small bowel transplantation. Transplantation 2008;85(10):1378–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishbein TM, Matsumoto CS. Intestinal replacement therapy: timing and indications for referral of patients to an intestinal rehabilitation and transplant program. Gastroenterology 2006;130(2 Suppl 1):S147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishbein TM. Intestinal transplantation. N Engl J Med 2009;361(10):998–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mundi MS, Pattinson A, McMahon MT, Davidson J, Hurt RT. Prevalence of Home Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition in the United States. Nutr Clin Pract 2017:884533617718472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data. [online] 2017.

- 8.Fishbein T, Novitskiy G, Mishra L, Matsumoto C, Kaufman S, Goyal S et al. NOD2-expressing bone marrow-derived cells appear to regulate epithelial innate immunity of the transplanted human small intestine. Gut 2008;57(3):323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lough D, Abdo J, Guerra-Castro JF, Matsumoto C, Kaufman S, Shetty K et al. Abnormal CX3CR1(+) lamina propria myeloid cells from intestinal transplant recipients with NOD2 mutations. Am J Transplant 2012;12(4):992–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2009;27:485–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wacleche VS, Landay A, Routy JP, Ancuta P. The Th17 Lineage: From Barrier Surfaces Homeostasis to Autoimmunity, Cancer, and HIV-1 Pathogenesis. Viruses 2017;9(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarra M, Pallone F, Macdonald TT, Monteleone G. IL-23/IL-17 axis in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16(10):1808–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science (New York, NY) 2006;314(5804):1461–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishbein TM, Kaufman SS, Florman SS, Gondolesi GE, Schiano T, Kim-Schluger L et al. Isolated intestinal transplantation: proof of clinical efficacy. Transplantation 2003;76(4):636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elsabbagh AM, Hawksworth J, Khan KM, Kaufman SS, Yazigi NA, Kroemer A et al. Long-term survival in visceral transplant recipients in the new era: A single-center experience. Am J Transplant 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrante M, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A et al. Validation of endoscopic activity scores in patients with Crohn’s disease based on a post hoc analysis of data from SONIC. Gastroenterology 2013;145(5):978–986 e975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Streitz M, Miloud T, Kapinsky M, Reed MR, Magari R, Geissler EK et al. Standardization of whole blood immune phenotype monitoring for clinical trials: panels and methods from the ONE study. Transplant Res 2013;2(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali JM, Bolton EM, Bradley JA, Pettigrew GJ. Allorecognition pathways in transplant rejection and tolerance. Transplantation 2013;96(8):681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerlach UA, Vogt K, Schlickeiser S, Meisel C, Streitz M, Kunkel D et al. Elevation of CD4+ differentiated memory T cells is associated with acute cellular and antibody-mediated rejection after liver transplantation. Transplantation 2013;95(12):1512–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14(5):329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroemer A, Cosentino C, Kaiser J, Matsumoto CS, Fishbein TM. Intestinal Transplant Inflammation: the Third Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2016;18(11):56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inokuchi T, Takahashi S, Hiraoka S, Toyokawa T, Takagi S, Takemoto K et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease who received infliximab or adalimumab as the first-line biologics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerlach UA, Koch M, Muller HP, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Neuhaus P, Pascher A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors as immunomodulatory antirejection agents after intestinal transplantation. Am J Transplant 2011;11(5):1041–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen J, Zhang M, Chen J, Zeng C, Cheng D, Liu ZH. HLA-DR overexpression in tubules of renal allografts during early and late renal allograft injuries. Experimental and clinical transplantation : official journal of the Middle East Society for Organ Transplantation 2013;11(6):499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espinosa J, Herr F, Tharp G, Bosinger S, Song M, Farris AB 3rd et al. CD57(+) CD4 T Cells Underlie Belatacept-Resistant Allograft Rejection. Am J Transplant 2016;16(4):1102–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pike R, Thomas N, Workman S, Ambrose L, Guzman D, Sivakumaran S et al. PD1-Expressing T Cell Subsets Modify the Rejection Risk in Renal Transplant Patients. Front Immunol 2016;7:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohty M Mechanisms of action of antithymocyte globulin: T-cell depletion and beyond. Leukemia 2007;21(7):1387–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroemer A, Xiao X, Vu MD, Gao W, Minamimura K, Chen M et al. OX40 controls functionally different T cell subsets and their resistance to depletion therapy. J Immunol 2007;179(8):5584–5591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malard F, Gaugler B, Lamarthee B, Mohty M. Translational opportunities for targeting the Th17 axis in acute graft-vs.-host disease. Mucosal Immunol 2016;9(2):299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gruhn B, Intek J, Pfaffendorf N, Zell R, Corbacioglu S, Zintl F et al. Polymorphism of interleukin-23 receptor gene but not of NOD2/CARD15 is associated with graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15(12):1571–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elmaagacli AH, Koldehoff M, Landt O, Beelen DW. Relation of an interleukin-23 receptor gene polymorphism to graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41(9):821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bossard C, Malard F, Arbez J, Chevallier P, Guillaume T, Delaunay J et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and Th17 immune response contribution in gastrointestinal acute graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia 2012;26(7):1471–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patriarca F, Sperotto A, Damiani D, Morreale G, Bonifazi F, Olivieri A et al. Infliximab treatment for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica 2004;89(11):1352–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van den Brande JMH, Braat H, van den Brink GR, Versteeg HH, Bauer CA, Hoedemaeker I et al. Infliximab but not etanercept induces apoptosis in lamina propria T-lymphocytes from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2003;124(7):1774–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ten Hove T, van Montfrans C, Peppelenbosch MP, van Deventer SJ. Infliximab treatment induces apoptosis of lamina propria T lymphocytes in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2002;50(2):206–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olesen CM, Coskun M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Nielsen OH. Mechanisms behind efficacy of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in inflammatory bowel diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2016;159:110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin YC, Lin YC, Wu CC, Huang MY, Tsai WC, Hung CH et al. The immunomodulatory effects of TNF-alpha inhibitors on human Th17 cells via RORgammat histone acetylation. Oncotarget 2017;8(5):7559–7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugita S, Kawazoe Y, Imai A, Yamada Y, Horie S, Mochizuki M. Inhibition of Th17 differentiation by anti-TNF-alpha therapy in uveitis patients with Behcet’s disease. Arthritis research & therapy 2012;14(3):R99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rathore JS, Wang Y. Protective role of Th17 cells in pulmonary infection. Vaccine 2016;34(13):1504–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, Vandemeulebroecke M, Reinisch W, Higgins PD et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut 2012;61(12):1693–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruiz P, Bagni A, Brown R, Cortina G, Harpaz N, Magid MS et al. Histological criteria for the identification of acute cellular rejection in human small bowel allografts: results of the pathology workshop at the VIII International Small Bowel Transplant Symposium. Transplant Proc 2004;36(2):335–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. A) Operative photographs of small bowel resection specimens from ITx patient with acute cellular rejection demonstrating mesenteric fat creeping, hyperemia with structuring, and upon sectioning the presence of cobblestoning inflammation, all reminiscent of patterns found in CD. B) Representative histologic sections at 10x magnification with zoom window at 60x with H&E stains as well as endoscopic images demonstrating the differences in uncomplicated transplant patients and those with severe acute cellular rejection and inflammatory manifestations.

Supplemental Figure 2: Proportions of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells in the peripheral blood and allograft of intestinal transplant patients in non-rejector control and active rejector patients at the time of rejection diagnosis and on treatment. A and B) Representative flow plots and violin plots of individual values of CD3+ as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations from peripheral blood samples gated on viable CD45+ lymphocytes and CD3+ T cells, respectively in non-rejector control versus rejector patients at the time of rejection diagnosis. Statistics performed with Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for both CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ is control n=15, rejection n=16. C and D) Representative flow plots showing alterations in CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in intestinal graft biopsies from non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin. Violin plots of individual values representing the percentage of CD3+ T cells of viable lymphocytes and of CD4+ and CD8+ cells of CD3+ T cells in non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin, respectively. Statistical testing performed using Kruskal-Wallis rank test with Wilcoxon rank tests for individual group comparisons. Sample size for CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ is control n=20, rejection n=10, rejection on thymo n=14.

Supplemental Figure 3: CCR6 and IL-17 expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes and CD45RO cytokine mean fluorescence in graft biopsies. A) Representative flow and violin plots of peripheral blood CCR6 and IL-17 expression in CD4 and CD8 T cells in non-rejector controls and severe rejectors at the time of rejection diagnosis. Statistics by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample sizes for CD4+ CCR6+ T and Th17 cells are control n=10, rejection n=13; for CD8+ CCR6+ T and Tc17 cells are control n=10, rejection n=13. B) Violin plots of CD45RO mean fluorescence index in CD4 and CD8 T cells in non-rejector controls versus non-responders with active rejection at the time of rejection diagnosis versus non-responders with active rejection on thymoglobulin, respectively. Statistics by Kruskal-Wallis rank testing with individual groups comparison by Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size is control n=20, rejection n=9, rejection on thymo n=12.

Supplemental Figure 4: Cytokine expression of Tc17 cells and predominance of TNF-α production in IL-17 producing CD8+CCR6+ Tc17 cells in severe refractory allograft rejection. A) LP CD8+ T cells isolated from non-rejector control and non-responder rejection graft biopsy samples during active rejection on treatment, stimulated with PMA/ionomycin and subsequently analyzed for intracellular IL-17, TNF-α, and CCR6 expression. Representative flow plots showing CD8+CD3+ gated populations exhibited intracellular cytokines IL-17 and TNF-α predominantly in the CCR6+ T cell populations; followed by violin plots of individual values representing comparative analysis of cytokine-expressing CCR6+CD8+ T cell subpopulations versus total cytokine-expressing CD8+ T cells in non-rejector control versus non-responder rejection patients. Statistics with Wilcoxon rank testing. Sample size for IL-17 CCR6+CD8+ is control n=10, rejection n=11; for IL-17 CD8+ control n=10, rejection n=11; for TNF-α CCR6+CD8+ control n=7, rejection n=11; for TNF-α CD8+ control n=7, rejection n=11. B) Representative flow cytometry of co-expression of IL-17 and TNF-α in actively rejecting allografts from non-responder rejection patients demonstrating a mean 85% of CCR6+CD4+ cells expressing IL-17 also expressing TNF-α. Violin plot showing mean expression. Sample size is n=11 for both groups.

Supplemental Table 1 & 2. Tables showing comparisons of genes between pre-rejection control, healthy control, and rejection patients with reported standard deviations in fold expression as well as the raw, adjusted p values and false discovery rate. All genes displayed regardless of significance. Group A is pre-rejection control patients (Supplemental Table 1) as defined as the most recent normal tissue sample prior to a diagnosis of rejection, or healthy control (Supplemental Table 2) and Group B is rejection patients at the time of rejection diagnosis. Sample size is control n=13, pre-rejection control n=13, and rejection n=13.