Abstract

Vaccines are critical tools for maintaining global health. Traditional vaccine technologies have been used across a wide range of bacterial and viral pathogens, yet there are a number of examples where they have not been successful, such as for persistent infections, rapidly evolving pathogens with high sequence variability, complex viral antigens, and emerging pathogens. Novel technologies such as nucleic acid and viral vector vaccines offer the potential to revolutionize vaccine development as they are well suited to address existing technology limitations. In this review, we discuss the current state of RNA vaccines, recombinant adenovirus vector-based vaccines, and advances from biomaterials and engineering that address these important public health challenges.

INTRODUCTION

Vaccines play a critical role in global health by preventing infection and transmission of multiple diseases worldwide (Orenstein and Ahmed, 2017). The World Health Organization estimates that vaccines prevent the death of 2–3 million people every year (WHO, 2019). Moreover, immunizations have enabled the eradication of smallpox and are now close to eradicating polio (Africa Regional Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis, 2020; Fenner et al., 1988). In addition, vaccines have a significant economic impact by reducing costs of illnesses and hospitalizations of over $500 billion (Orenstein and Ahmed, 2017; Ozawa et al., 2016).

Although traditional vaccines have been tremendously successful, there are many infectious diseases for which no efficacious vaccines have been developed. The development of vaccines for human pathogens such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has thus far been unsuccessful. HIV has caused 39 million deaths globally and over 36 million people still live with virus today (Pandey and Galvani, 2019). Even with the availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART), approximately to 2 million people become infected every year. Similarly, TB causes 1.6 million deaths annually (Singh et al., 2020b). RSV is a major cause of lower respiratory tract infections and hospital visits during infancy and childhood, with 59,600 in-hospital deaths occurring in 2015 globally (Shi et al., 2017). In the United States alone, each year, more than 40,000 infants are born with congenital CMV infection, with nearly a 20% of these children developing permanent hearing loss, brain damage, or neurodevelopmental delays (Johnson et al., 2012). In addition, emerging and re-emerging pathogens such as Ebola virus, Zika virus, and most recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have become major global health threats. Combatting outbreaks requires the rapid development of vaccines that has not typically been possible with traditional vaccine platforms.

These challenges have sparked intense interest in the development of novel vaccine technologies. In this review, we will review three such platforms: mRNA vaccines, vector-based vaccines, and materials science approaches to vaccination. We will discuss the development of these platforms, including applications to the COVID-19 pandemic.

BACKGROUND

The human immune system has several lines of defense that protect against infection. The first ones are physical and chemical barriers such as skin, mucous membranes and gastric acid. If a pathogen bypasses these obstacles and causes infection, a series of sensors are present to detect foreign agents or antigens and to activate the innate immune system. These sensors have evolved to discriminate between self and non-self and to recognize conserved features of pathogens. For example, nucleic acid sequences and secondary structures of viruses are recognized by sensors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Bartok and Hartmann, 2020). Innate sensors trigger downstream signaling pathways, activating a non-specific, albeit rapid, innate immune response characterized by inflammation, cytokine production, recruitment of immune cells, and activation of phagocytic cells that neutralize pathogens and infected cells. Further, inflammation draws antigen presenting cells (APCs) to the site of infection, where they take up antigens and traffic to secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and spleen, to guide the activation of T and B cells, which constitute the adaptive immune response.

Although reliant on innate immune activation, the adaptive immune system is the classic pathogen-specific response. Within the secondary lymphoid tissues, APCs drive the expansion of different subsets of T cell populations. Notably, they trigger CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, which have the ability to recognize and kill cells infected by specific pathogens. APCs also expand CD4+ helper T cells, which aid in the differentiation of B cells that ultimately generate antigen or pathogen specific antibodies. These antibodies are critical in clearing infections by either binding to microbes to prevent cellular entry or by tagging pathogens for destruction by complement or innate immune cells (Dimitrov and Lacroix-Desmazes, 2020; Lu et al., 2018). Eventually, these T and B cells adopt memory phenotypes, which leaves cells poised to expand and re-activate in response to a future pathogen encounter. Importantly, the next time the body is exposed the same pathogen, this memory or recall can respond more rapidly and effectively.

Vaccines work by exposing a subject to a part or whole pathogen, thus activating the immune system. Traditional types of vaccines include live-attenuated, inactivated, and replication-defective pathogens as well as subunit and conjugate vaccines. Live-attenuated vaccines consist of weakened form of a pathogen. Attenuating pathogens usually involves passaging them through a series of cultures or animal embryos until they lose the ability to replicate efficiently in human cells. Some examples of clinically approved live-attenuated vaccines include those against smallpox, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), and yellow fever. Though live-attenuated vaccines elicit strong immune responses, the administration of a live pathogen could pose a risk for people with weakened immune systems or other health complications. An alternative approach is to administer a whole inactivated pathogen to mitigate this safety risk. Inactivated vaccines include hepatitis A virus, inactivated poliovirus, and rabies virus vaccines. Of note, the development of both live-attenuated and inactivated vaccines requires large-scale growth of the pathogen posing a bio-safety risk. Finally, subunit vaccines are composed of a piece of a pathogen. Sub-unit vaccines have favorable safety profiles and eliminate the need to culture or grow live pathogen, but often require booster immunizations as well as adjuvants. Advances in adjuvant technology as well as genomics have led to the introduction of a series of new vaccine approvals in the recent years, such as Heplisav (CpG adjuvanted hepatitis B vaccine) (Champion, 2020), Shingrix (Recombinant zoster vaccine adjuvanted with AS01B) (Singh et al., 2020a), and Bexero (meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine incorporating recombinant protein and outer membrane vesicle adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide adjuvant) (Rodrigues et al., 2020).

Limitations of traditional vaccine platforms have sparked the discovery and development of novel vaccine technologies. These approaches include viral vector vaccines (Barouch and Picker, 2014; Ertl, 2016) as well as nucleic acid vaccines (Bahl et al., 2017; John et al., 2018; Lindgren et al., 2017). These new technologies can address unmet medical needs, such as for vaccines that involve antigens that are difficult to manufacture or for novel pathogens for which rapid development is critical. In the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the four most advanced programs in Phase 3 trials in the United States are based on these technologies, including two mRNA vaccines and two adenovirus vectored vaccines (Folegatti et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Mulligan et al., 2020; Sadoff J. et al., 2020). This review will focus on the current status of mRNA vaccines and recombinant adenovirus vector-based vaccines as well as applications of engineering and materials science to vaccine delivery platforms.

mRNA VACCINES

mRNA vaccines have gained considerable attention in the recent years as they have the potential to expedite vaccine development, to have improved safety and efficacy, and to tackle diseases that have not been possible to prevent with other approaches. mRNA is non-infectious, non-integrating and is degraded by normal cellular processes shortly after injection, decreasing the risk of toxicity and long-term side effects. Intracellular expression of the antigen by mRNA may lead to strong T-cell responses typically seen with viral vector-based or replication defective virus-based vaccines. However, mRNA vaccines have the advantage that they do not induce vector specific immunity and do not contend with either pre-existing or newly raised vector immunity that could interfere with subsequent vaccinations. More than 10 mRNA vaccines were already at different stages of clinical testing before the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. These studies have demonstrated the safety and immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines in thousands of vaccinated subjects including children and elderly subjects.

mRNA vaccines enable precise antigen design and the generation of proteins with a “native-like” presentation (e.g, membrane bound with human glycosylation patterns); expression of proteins stabilized in a more immunogenic conformation or exposing key antigenic sites (e.g. prefusion stabilized) (Espeseth et al., 2020); and delivery of multiple mRNA to the same cell allowing the generation of multi-protein complexes (John et al., 2018) or protein antigens from different pathogens thus creating a single vaccine against several targets.

mRNA vaccines are manufactured using a chemically defined, consistent processes, regardless of the antigen encoded by the mRNA, and this has the potential to simplify vaccine production, scale up, quality control and the overall vaccine development timelines. These factors allow for multiple iterative cycles of antigen improvements and human evaluation thus shortening the overall development time to safe and efficacious vaccines (Figure 1). Finally, as this is such a rapidly developing field there are many opportunities for innovation, improvements, and new developments.

Figure 1:

Process for mRNA vaccine development, from target identification to vaccination. (1) It starts with the identification and design of a target antigen, (2) Digital sequence design based on propriety algorithm, (3) Manufacturing of plasmid, mRNA, and lipid nanoparticle (LNP), (4) Fill, finish, and QC, (5) intramuscular injection, cellular uptake, protein expression, and immune activation

A unique feature of mRNA vaccines is that they can be produced and scaled up in a predictable and consistent fashion and with well-established processes and reagents within weeks regardless of the antigen. This feature is advantageous during outbreaks caused by new viruses or pandemic situations where a rapid response is needed. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated investment in manufacturing and scale-up of mRNA vaccines leading to commercial scale production. Two mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (Moderna Inc. mRNA-1273, Pfitzer/BioNTech BNT162b2) have been tested in large Phase 3 clinical trials and were demonstrated to be safe and highly efficacious in both adults and elderly subjects. Importantly, both manufacturers expect to produce hundreds of millions of doses of vaccine for deployment in 2021. These are the first licensed mRNA vaccines, and their wide acceptance and use would open the way to several other novel mRNA vaccines against infectious disease targets.

From DNA to mRNA vaccines

The earliest nucleic acid vaccine platform (late 1990s and early 2000s) used plasmid DNA generated after propagation in bacteria, extraction, and purification. The initial report by Ulmer et al. showed that naked DNA could generate potent immune responses against influenza virus after injection in mouse muscle with no need for additional formulation (Ulmer et al., 1993). In subsequent years, this technique did not translate to larger species (Jiao et al., 1992; Wolff and Budker, 2005). When tested in humans, immune responses were weak and not durable (Liu and Ulmer, 2005) and required doses >1 milligram. Delivery was found to be a key limiting factor for plasmid DNA as it needs to enter the cell then pass through the nuclear membrane – an inefficient process in nondividing cells. Device-mediated plasmid DNA delivery such as electroporation and jet injectors has recently shown some promise (Al-Dosari and Gao, 2009). These devices enhance delivery through physical deformation of the cell membrane facilitating nucleic acid cell entry. Nevertheless, the need for a device as well as high (e.g. milligram) dose levels are likely to limit broad use of plasmid DNA vaccines.

The use of mRNA as a vaccine platform has gained significant attention more recently. Like plasmid DNA, mRNA was first shown to be expressed in animals after naked injection in muscle (Wolff et al., 1990). However, until recently there were many perceived limitations of mRNA such as vulnerability to nucleases, inherent instability, challenging manufacturing processes, and unwanted innate immune system stimulation that kept researchers and vaccine manufacturers away. Initial failure of DNA vaccines also raised concerns about the potency of nucleic acid vaccine approaches in humans. Progress over the past 10 years in mRNA science, delivery and immunology has advanced the field to the point where multiple mRNA vaccines are now in advanced clinical trials.

mRNA structure and design

Synthesis of mRNA is performed in vitro using a plasmid DNA as template, an RNA polymerase, nucleoside triphosphates and buffers (in vitro transcription, IVT) (Sahin et al., 2014). To be biologically active mRNA requires addition of an inverted triphosphate cap (e.g. N7-methylated guanosine) to the 5’ end of the mRNA molecule. The cap can be added co-transcriptionally as with anti-reverse cap analog (ARCA) or enzymatically with an enzyme such as vaccinia capping enzyme (Shuman, 1990). Once produced, mRNA is then purified to remove impurities generated during IVT using chromatography techniques such as HPLC or affinity purification.

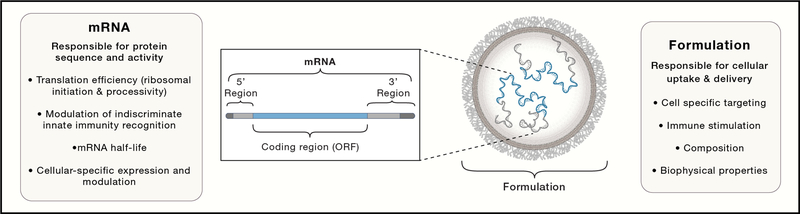

The final “active” mRNA consists of a cap at the 5’ end, a 5’ untranslated region (UTR), open reading frame (ORF), 3’ UTR, and poly-adenylation tail (Poly-A) resembling fully processed, mature, endogenous mRNA molecules present in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells (Figure 2). Each of these elements are critical for mRNA activity and provide targets for modifications to improve stability, translation efficiency and ultimately protein expression levels and duration. Untranslated regions (UTRs) are important regulators of mRNA decay and translational efficiency via cellular RNA-binding proteins. The 3’ UTR sequence has been shown to modulate mRNA half-life (Guhaniyogi and Brewer, 2001; Orlandini von Niessen et al., 2019), while the 5’ UTR plays a role in stability and translation initiation efficiency (Leppek et al., 2018). Codon optimization of the ORF results in changes of secondary structure content and translation elongation rate both of which impact protein expression levels and potentially protein folding (Mauger et al., 2019). Finally, a long poly-A tail (i.e. > 120 units) has been reported to increase protein expression (Holtkamp et al., 2006).

Figure 2:

mRNA vaccines are composed of proprietary lipid nanoparticle delivery systems and mRNA optimized for stability and translation.

mRNA mechanism and immunogenicity

Once administered intramuscularly, mRNA formulated in LNPs are taken up by antigen presenting cells (APCs), including dendritic cells, through endocytic pathways (Akinc et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2017). Next, the mRNA activates innate sensors present in the endosome and the cytosol and is also translated into protein antigen in the cytoplasm. The mRNA itself can be recognized by a variety of endosomal and cytosolic innate immune receptors (Chen et al., 2017), thus modulating the overall immune response to the vaccine. The newly synthesized antigen can engage both B cells and T cells, driven by the concomitant expression of antigen and innate activation of the immune system.

Innate immune stimulation is driven by mechanisms that immune cells have developed to enable responses against pathogens and are primarily driven by activation of cellular sensors against viral mRNA and DNA, bacterial lipids and sugars. Different elements of mRNA vaccines can engage pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) such as TLR3 and TLR7/8 in endosomes, cytosolic sensors like MDA5 and RIG-I, and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) (Chen et al., 2017). These sensors respond to pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMPs) like double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and/or single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) present in the vaccine, resulting in robust type 1 interferon signaling (Zhang et al., 2016). Activation of the type 1 interferon pathway can be beneficial as it can drive the activation and maturation of APCs, key to eliciting robust B cell and T cell immune responses, but it can also be detrimental as it can negatively impact protein translation and therefore immunogenicity as well as tolerability.

Some mRNA vaccine candidates use canonical bases without modifications (Rauch S. et al., 2020), an approach that has been shown to be immunogenic in in vivo studies but also demonstrated strong immune activation. Kariko et al. observed that base modifications lessened the degree of innate stimulation driven by mRNA (Kariko et al., 2011). Recent reports have demonstrated that use of N1-methyl-pseudouridine modified mRNA results in robust protein translation (Corbett et al., 2020a; Corbett et al., 2020b; Jackson et al., 2020; John et al., 2018). mRNA with this nucleoside-modification was found to circumvent TLR7/8 activation, thus decreasing innate immune activation (Espeseth et al., 2020; Kariko et al., 2005), while still eliciting strong immune responses both preclinically and clinically (Corbett et al., 2020a; Corbett et al., 2020b; Espeseth et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; John et al., 2018). In summary, mRNA process changes and purification, codon optimization and bases replacement can be used to modulate innate immune activation and therefore immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines (Linares-Fernandez et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2020).

The kinetics of antigen expression by mRNA vaccines also plays a role in the induction of immune response and durable immune memory. Studies have demonstrated that high antibody titers and germinal center (GC) B-cell and T follicular helper (TFH) cell responses are induced by sustained antigen availability resulting from mRNA vaccination (Liang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Lindgren et al., 2017). TFH cells are critical to the development of potent and durable neutralizing antibody responses, and have been measured in response to vaccination by mRNA vaccines, most recently mRNA-1273 (Corbett et al., 2020b).

Lipid nanoparticle mRNA delivery

In contrast to naked mRNA, formulated mRNA has been shown to result in higher protein expression in vitro and more potent immune responses in vivo (Pollard et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 1990). Formulations for mRNA vaccines perform many functions including stabilizing mRNA before injection and also facilitating mRNA entry into the cell to allow endosomal escape and delivery of the mRNA into the cytoplasm, and subsequently degrade into metabolic intermediates. Although there are several approaches to introduce nucleic acids into cells, the field has converged recently on ionizable lipid-based systems or lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) as the delivery system of choice.

Lipid nanoparticles are approximately 100 nanometer diameter delivery vehicles that approximate the size and composition of natural apolipoproteins such as VLDL. When injected into animals or humans LNPs are rapidly opsonized by serum or interstitial proteins and trafficked similar to endogenous apolipoproteins to cells expressing lipid or scavenger receptors (e.g., LDLR, SR-B1). LNPs are typically composed of four components: an ionizable lipid, cholesterol, PEGylated lipid, and a helper lipid such as distearoylphosphatidylcholine (DSPC) (Adams et al., 2018; Jayaraman et al., 2012; Lutz et al., 2017) (Figure 2). The formulations are prepared through rapid precipitation and a self-assembly process at low pH (Hassett et al., 2019a). LNPs can deliver RNAs very efficiently even when compared to a viral vector. When a viral replicon genome is delivered with an LNP and compared with a viral particle containing the same genome both generated similar immune responses in rodents (Geall et al., 2012).

Among the components of the LNP the amino lipid is key to their function. Early work relied on amino lipids used in other nucleic acid delivery systems, such as siRNA. These LNPs had some tolerability challenges related to biodegradability and composition. Subsequent efforts have led to the identification of biodegradable ionizable lipids that, when incorporated into the LNP improved the potency of the vaccine (Hassett et al., 2019a). In preclinical studies the inclusion of a biodegradable lipid within an LNP also resulted in reduction in injection site inflammation resulting in vaccines with improved tolerability as the lipid is cleared quickly from the site of injection and other tissues have minimal exposure to the lipid due to metabolic breakdown and clearance. Importantly for vaccines, the increased innate immune stimulation driven by LNPs does not equate to increased immunogenicity, illustrating that mRNA vaccine tolerability can be improved without affecting potency.

The first mRNA LNP vaccines to be evaluated in clinical studies were for H10 and H7 influenza hemagglutinin in 2015 and 2016 respectively. Phase I clinical data showed 100% seroconversion with 25 and 100-μg dose of modified uridine mRNA, respectively, with an adverse event profile similar to other approved vaccines (Feldman et al., 2019). From those first experiments until the COVID-19 pandemic, 8 other mRNA vaccines have advanced into the clinic of which 5 rely on LNPs. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to 8 additional programs just in 2020.

saRNA vs mRNA

In addition to conventional mRNA constructs, self-amplifying mRNA (saRNA) based on linear, nonsegmented, single-stranded, positive-sense viral genomes are being evaluated as vaccines. In this approach the viral genome encoding the nonstructural replication-specific proteins are retained and the structural open reading frames (ORFs) are replaced with ORFs coding for the antigen of interest. The goal is to mimic a viral infection, but without the ability to create an infectious particle due to the lack of structural viral proteins. However, compared to an mRNA encoding for the same vaccine antigen the size of saRNA is greatly increased due to the addition of the viral non-structural replication machinery.

A number of reports have compared conventional, unmodified mRNA and saRNA for vaccination (Bernstein et al., 2009; Maruggi et al., 2017; Probst et al., 2007). Dose sparing was observed with the saRNA however, none of these reports include the extensive mRNA sequence modification approaches that can be used to optimize protein expression, minimize nuclease degradation or modulate stimulation of innate immunity. The only clinical data published to date are for the modified mRNA vaccines that are currently in Phase 3 studies. A recent Phase I trial for COVID-19 vaccines sponsored by Pfizer/BioNTech could provide the first clinical comparison of unomdified mRNA, saRNA and modified mRNA (NCT04380701). It is important to note that saRNA is more difficult to scale up due to construct length, purification challenges, enzymatic reaction inefficiencies and is intrinsically far less stable than mRNA as 1 strand breakage every 10,000 bases inactivates saRNA vs 1 per every ~2500 bases for mRNA.

mRNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-2

mRNA vaccines are well suited to respond to new emerging pathogens and infectious disease outbreaks with pandemic potential. Indeed, the use of methods and processes that are antigen independent make this approach intrinsically faster and more reliable than other technologies. A striking example of the flexibility, speed, and scalability of the mRNA/LNP technology is exemplified by the development of the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 and Moderna Inc. mRNA-1273 vaccine candidates, both encoding the SARS-CoV-2 pre-fusion stabilized S2P protein, which showed very high efficacy in Phase 3 trials (Baden et al., 2020a; Jackson et al., 2020; Mulligan et al., 2020; Polack et al., 2020). The mRNA-1273 antigen design was facilitated by previous pre-clinical work on a mRNA vaccine against MERS CoV (Corbett et al., 2020a). mRNA-1273 was produced, vialed and ready for clinical testing within 42 days from the time of virus RNA sequence was made available. Sixty-four days from sequence availability, an NIH sponsored Phase 1 study initiated dosing and was followed by a Phase 2 study and then a 30,000 subject placebo-controlled Phase 3 efficacy study two months later. The Phase 1 study demonstrated that the vaccine is safe and well tolerated and to elicit comparable immune responses across different age groups (18–55, 55–71, 71+ old) (Anderson et al., 2020). A large-scale effort was made to scale up mRNA/LNP production, purification, analytical methods, development and testing of the vaccines to stand to the task of producing hundreds of millions of doses per year. In addition to these 2 late stage candidates, there are other mRNA/LNP vaccines in preclinical or early clinical evaluation from Curevac (CVnCoV, unmodified mRNA, currently in phase II), Arcturus (ARCT-021, SAM in LNP, currently in phase I), Translate Bio / Sanofi (MRT5500, unmodified mRNA, currently being evaluated preclinically). It is therefore conceivable that in the future, a pandemic response with mRNA vaccines may be even faster as a suitable infrastructure, safety and regulatory framework have been established.

ADENOVIRUS VECTOR-BASED VACCINES

One strategy to drive in vivo vaccine antigen expression is to harness natural carriers of genetic instructions such as viruses. During infection, viruses multiply by hijacking the host cellular machinery to self-replicate. Thus, viruses are intrinsically equipped to enter target cells, deliver genetic instructions to key intra-cellular compartments, and drive efficient protein expression. An idea that has been pursued in many fields – spanning gene therapy, immunotherapy, vaccine design, and more – is to harness these intrinsic features of viruses to direct in vivo gene expression. Briefly, cassettes encoding these genes of interest are inserted into the viral genome, often by replacing key viral genes. This replacement serves dual purpose: i) rendering the virus replication-incompetent or less virulent for safety purposes and ii) freeing space to insert genes without significantly changing the inherent genome size (Lee et al., 2017). Over the past several decades different viruses have been developed into vectors including adenoviruses (Ads) (Barouch and Picker, 2014; Ertl, 2016), cytomegaloviruses (Barouch and Picker, 2014), adeno‐associated viruses (AAV) (Andari and Grimm, 2020), poxviruses (Conrad and Liu, 2019), herpesviruses (Artusi et al., 2018), and retroviruses (Chen et al., 2018b; Luis, 2020; Stephenson et al., 2016). For the purposes of this review, we will focus on the current state of adenovirus vector development.

Ad vectors

Adenoviruses (Ads) often cause mild or asymptomatic respiratory infections, although infections can be more severe, or even life-threatening, in immunocompromised individuals. Adenoviruses constitute a double-stranded DNA genome encased in a protein capsid (Usman and Suarez, 2020). The capsid structure includes fibrous projections that extend from the core and bind to receptors expressed on host cells mediating cellular entry (Baker et al., 2019).

Ads initially emerged as a promising platform for gene therapy to deliver and induce persistent expression of absent or mutated genes in patients suffering from genetic diseases. The unique ability of Ads to infect a wide range of cell types, including hepatocytes, myoblasts as well as epithelial and endothelial cells, was especially beneficial for broadly inducing gene expression. An Ad vector was used for the first time in 1992 to treat two genetic disorders; alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (Lemarchand et al., 1992) and cystic fibrosis (Rosenfeld et al., 1992). In these studies, Ad vectors were demonstrated to deliver therapeutic genetic material to host cells efficiently. However, Ad vectors triggered inflammatory host innate immune pathways that aim to recognize foreign patterns of viral structures (Shirley et al., 2020). This innate immune trigger limited Ad vector transduction and transgene expression. Consequently, it also induced an adaptive immune response against the vector which limited the efficiency of subsequent vector administrations needed for persistent therapeutic gene expression. Thus, the use of Ad vectors in gene therapy revealed potent immunogenicity (Zaiss et al., 2009).

Immunogenicity of Ad vector vaccines

Although the intrinsic immunogenicity of Ad vectors presented limitations for applications in gene therapy, these properties supported the development of Ad vectors as a promising platform for vaccines. In the context of vaccination, simultaneous innate immune activation and antigen expression are key in promoting downstream expansion of antigen-specific T cells and B cells required for vaccine efficacy. Underscoring this feature of vector-based vaccines is the fact that other platforms, such as subunit or protein-based vaccines, typically require additional adjuvants or components to elicit potent, effective immune responses. In contrast, Ads are self-adjuvanting, simplifying the vaccine composition and formulation process. Ads intrinsically induce host innate immune response by activating cellular sensors that detect viral components (Coughlan, 2020; Rathinam and Fitzgerald, 2011). The primary innate immune trigger of Ad vectors is the viral genome, which contains foreign patterns and sequences that are not common in host genetic material. Ad capsids lacking DNA have been shown to induce reduced innate responses (Iacobelli-Martinez and Nemerow, 2007). Thus, foreign DNA sensors such as TLR9 and cyclic guanosine monophosphate-AMP synthase (cGAS) play a critical role in Ad vector innate immunity. This innate sensor activation leads to inflammation, production of cytokines such as interferons, and tissue infiltration by immune cells at the site of vaccination (Coughlan, 2020). Concurrent expression of antigen in this inflammatory environment can upregulate co-stimulatory markers on antigen presenting cells (APCs). Consequently, antigen-presenting cells drive the expansion of adaptive T and B cells which are critical for vaccine immunity and immune memory.

In addition to their self-adjuvanting capability, another property that makes Ads suitable vaccine vectors is their tropism. They have an intrinsic cell transduction capability and can efficiently express transgene antigens both in dividing and nondividing cells (Vorburger and Hunt, 2002). This flexibility increases the probability of successful, high level transgene expression across multiple cell types, leading to efficient production of vaccine antigen in situ required for a robust antigen specific vaccine immunity.

Ad pre-existing immunity

Although Ad vectors efficiently mediate broad and efficient transduction of vaccine transgenes in cells, this capability hinges on the absence of substantial preexisting adenovirus immunity in the host. At the population level, successful Ad vector immunization could be thwarted by preexisting immunity if people have already been infected with the type of adenovirus used as a vaccine vector. Most human adenoviruses are ubiquitous around the world and have infected the majority of the population by adulthood (Barouch et al., 2011; Mennechet et al., 2019). This induces neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against Ad vaccine vectors and interfere with cellular entry. Various strategies have been developed to address this concern. These include the use of rare human or non-human Ads as well as vector capsid engineering to evade neutralization.

Human adenoviruses can be classified into seven groups A-G and contain 67 serotypes that are phylogenetically distinct (Crenshaw et al., 2019). Although most of these serotypes are common, rare human adenoviruses such as Ad26 and Ad35 have been reported to have lower seroprevalence in humans than Ad5 (Barouch et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2010). Both serotypes have been demonstrated to evade the prevalent Ad5 immunity and induce robust and protective antigen specific cellular and humoral immune responses (Geisbert et al., 2011).

The initial cloning and vectorization of Ad26 and several other Ad serotypes allowed a comparison of seroprevalence and immunogenicity of various candidate Ad vector platforms (Abbink et al., 2007). In addition to low titers of baseline vector-specific antibodies and high immunogenicity, Ad26 vectors can grow to high titers allowing for large scale production (Abbink et al., 2007). Ad26 vaccines for HIV have successfully advanced from preclinical studies to clinical trials for HIV and other pathogens (Baden et al., 2020b; Barouch et al., 2018a; Stephenson et al., 2020), which set the stage for the utilization of the Ad26 vector in the vaccine development for SARS-CoV-2 as well as other pathogens (Mercado et al., 2020b; Sadoff et al., 2021).

Similarly, non-human Ads have also been utilized as vaccine vectors to address anti-vector immunity. Non-human serotypes are genetically and structurally similar to human adenoviruses, making them easily adaptable as vaccine vectors. Commonly used non-human Ads include chimpanzee (ChAd), gorilla (GAd), and rhesus macaque (RhAd) serotypes. Safety and efficacy of ChAd vaccine vectors has been demonstrated in preclinical and clinical studies against SARS-COV-2 (Folegatti et al., 2020), HIV (Hayton et al., 2014) and rabies (Zhou et al., 2006). Nevertheless, the seroprevalence of certain ChAds has been shown to be up to 20% in developing countries (Xiang et al., 2006). This has sparked interest in the discovery of alternative carriers such as RhAds, which have greater phylogenetic distance from human Ads (Abbink et al., 2018; Panto et al., 2015). RhAds have shown promise in preclinical studies for HIV (Iampietro et al., 2018) and Zika (Larocca et al., 2019).

Strategies to re-engineer vectors to circumvent pre-existing immunity have emerged. These strategies seek to identify and replace specific regions, sequences, or epitopes targeted by pre-existing immunity. Anti-vector antibodies and T cells primarily target surface antigens of Ad vectors to dampen vaccine efficacy. Of the surface antigens, the hexon protein is a primary target of NAbs. Thus, pre-existing immunity can be evaded by replacing the hexon sequence of the exposed epitopes. This method has been applied to human adenovirus 5 (Ad5) and has allowed for enhanced transgene expression (Roberts et al., 2006; Sumida et al., 2005).

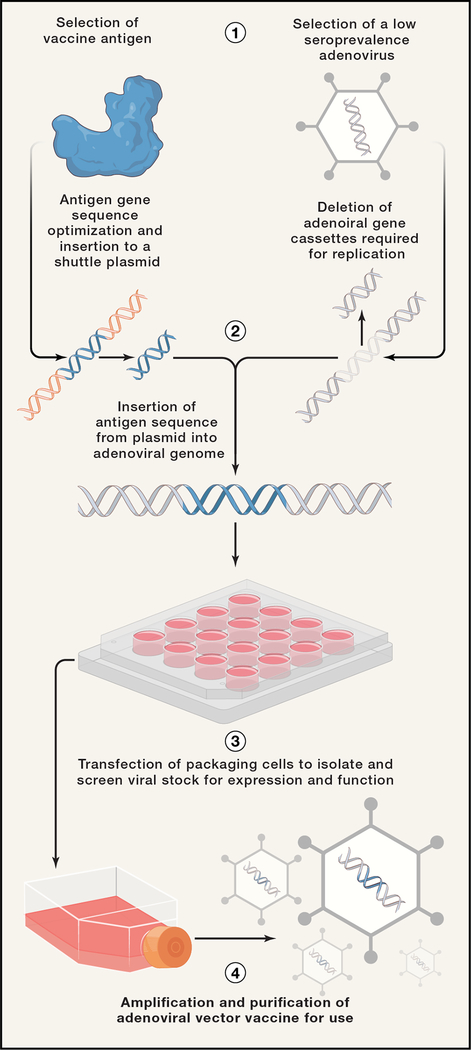

Ad vector design, production and application

Adenoviruses contain a 34–43 kilobase (kb) pair double stranded DNA, a relatively small viral genome size which enables facile manipulation (Figure 3). The construction of adenoviral vectors typically involves the deletion of a key viral gene, E1, to render the virus replication-deficient (McGrory et al., 1988). As noted above, this modification enhances the safety profile and allows the insertion of a vaccine antigen transgene of interest. Further design refinement has identified the E3 region as an additional target for deletion freeing up space to accommodate large transgenes. As the E3 protein has been demonstrated to dampen ideal cellular innate immune responses, deletion of the gene also offers optimal vector innate immunogenicity (Windheim et al., 2004). Once an adenovirus vaccine vector is constructed, it is used to transfect packaging cells such as HEK293’s to prepare a primary viral stock that is screened for antigen expression and function. Packaging cells are transfected or supplemented with the E1 gene to allow the virus vector to replicate. Lastly, the primary stock goes through large-scale production and purification for clinical use.

Figure 3:

Process of adenovirus vector vaccine development. (1) First a vaccine antigen as well as an adenovirus vector with low seroprevalence are identified. (2) The gene sequence of the viral antigen is optimized and cloned into a shuttle plasmid. This plasmid is used to insert the antigen sequence into an adenoviral backbone in place of viral gene cassettes. (3) Then a primary viral stock is made in virus packaging cells and screened for antigen expression and function. (4) Lastly, the viral stock is amplified and purified for immunizations.

Critically, this approach to incorporate genetic instructions into the Ad genome enables flexible and rapid vaccine development. For example, Ad vectors offer the potential to incorporate and screen different sequence variants of the same antigen to identify optimal vaccine candidates quickly. In addition to ease and speed of vaccine development, Ad vector production is also scalable and does not require high level biosafety containment and infrastructure, particularly compared to vaccine approaches that would require large-scale production of highly contagious and virulent pathogens prior to inactivation (Kamen and Henry, 2004). For example, Janssen’s AdVac and PER.C6 high density cell production technology has allowed for the accelerated and large-scale production of millions of doses of an Ad26-Ebola vaccine that has been used extensively in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Rwanda (Goldstein et al., 2020; Kitonsa et al., 2020) and that has recently received regulatory approval in Europe.

These advantages of Ad vectors have made them promising vaccine platforms for a wide range of pathogens (Figure 4), including persistent infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Baden et al., 2020b; Barouch et al., 2018a; Stephenson et al., 2020). In the case of HIV, Ad vaccines have allowed for the use of multivalent or mosaic sequences of HIV antigens that could be expressed together to elicit markedly enhanced immune responses (Barouch et al., 2010). Ad vector vaccines have also been developed for other persistent infections such as hepatitis C (Hartnell et al., 2018) and influenza (Matsuda et al., 2019). Most Ad vaccines have been developed for viral diseases as the vectors mimic a viral infection by triggering similar innate immune sensors and inducing potent antibodies as well as CD8 cytotoxic responses, which are critical in clearing virus and lysing virally infected cells (Fields et al., 2000). However, Ad vaccines have also been developed for bacterial and parasitic diseases such as tuberculosis (Walsh et al., 2016) and malaria (Tiono et al., 2018). The rapid and scalable development of potential of Ad vector-based vaccines have also made them well suited for outbreak scenarios when rapid vaccine development and widespread distribution are critical. Consequently, adenoviral vaccines have been developed for outbreak viruses such as Ebola (Tapia et al., 2020) and Zika (Abbink et al., 2016; Bullard et al., 2020; Larocca et al., 2019).

Figure 4:

Characteristics of an adenoviral vaccine vector. Adenoviral vaccine vectors include a viral genome containing genes of antigen/s of interest for expression as well as viral capsid and fiber for cellular delivery.

Ad vector-based vaccines for SARS-CoV-2

After the coronavirus genome sequence was made available in January 2020, multiple COVID-19 Ad vaccine candidates were developed to enter clinical trials in a matter of months.

AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford developed a chimpanzee Ad-based COVID-19 vaccine (ChAdOx1). The phase 1/2 trial involved a prime-boost immunization and demonstrated that the vaccine was safe and immunogenic with both T cell and neutralizing antibody responses (Folegatti et al., 2020; van Doremalen et al., 2020). A global Phase 3 trial for the vaccine enrolled 23,848 participants and demonstrated robust efficacy (Voysey et al., 2021).

CanSino Biologics developed an Ad5-based COVID-19 vaccine, which has also been shown to be safe, tolerable and immunogenic (Zhu et al., 2020b). By July 2020, a phase 2 clinical trial for this vaccine demonstrated immunogenicity in the majority of 508 eligible participants (Zhu et al., 2020a). In August 2020, CanSino begun phase 3 trials in 40,000 participants in multiple countries.

Johnson & Johnson developed an Ad26-based COVID-19 vaccine in collaboration with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. A single immunization of this vaccine induced neutralizing antibody responses that correlated with protection against SARS-CoV-2 challenge in rhesus macaques (Mercado et al., 2020a). This vaccine entered Phase 1/2 trials in July of 2020 and demonstrated satisfactory safety and immunogenicity profile (Sadoff et al., 2021). Furthermore, it elicited a strong and protective humoral response post prime in over 90% of the participants (Sadoff et al., 2021). The Phase 3 clinical trial in 44,000 participants, which began in September of 2020, demonstrated 85% efficacy in preventing severe COVID-19 disease 28 days after a single immunization, including in Latin America and in South Africa against the B.1.351 variant. Additional features of this vaccine are that it is protective with a single shot and does not require subzero freezing, which should facilitate vaccine campaigns.

The Gamaleya Research Institute developed a COVID-19 vaccine that combined two Ads, Ad5 and Ad26. The vaccine was shown to be safe and to generate both humoral and cell-mediated responses in a phase 1 clinical trial (Logunov et al., 2020). The Phase 2/3 trial was launched mid-October 2020 and has reported high efficacy.

BIOMATERIALS-BASED VACCINES

Engineering strategies have been employed to optimize carrier efficacy for vaccines, for example by tuning lipid composition and physiochemical properties to design LNPs for mRNA vaccines (Hassett et al., 2019b). More generally, approaches that combine immunogen design with materials science and engineering techniques have emerged as a promising strategy for multiple vaccine platforms (Chung et al., 2020; Fries et al., 2020). Bioengineering-based platforms, therefore, offer potential to tune the magnitude and nature of responses elicited, ideally skewing towards cell phenotypes, functions, and frequencies known to protect from infection or disease. Several reviews have described the application of various materials platforms in applications for not only infectious diseases (Fries et al., 2020; Yenkoidiok-Douti and Jewell, 2020), but also for cancer immunotherapy (Karlsson et al., 2018; Wang and Mooney, 2018) or to combat autoimmune diseases (Gammon and Jewell, 2019; Northrup et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2019).

During infection, the physical structure and composition of pathogens engage both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system. Yet conventional vaccine platforms, such as heat or chemical inactivation or delivery of subunits, can alter how antigens interact with immune cells and tissues. For example, protein-based vaccines have excellent safety profiles, but are often plagued by poor immunogenicity if delivered without adjuvant (Fan and Moon, 2017; Kuai et al., 2018). One strategy to augment immune responses is to incorporate molecular adjuvants to trigger key innate inflammatory pathways (e.g., TLRs) that are typically activated by pathogens, but not by proteins alone (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2004). These strategies often rely on co-delivery of signals to the same tissues or even to the same cell. Yet the cargos of interest – protein antigen, nucleic acid-based adjuvants, small molecule immunomodulatory drugs, recombinant cytokines – have vastly different physiochemical properties and, therefore, exhibit disparate biodistribution and half-life following injection (Kuai et al., 2018; Lynn et al., 2015). This variance can present a significant challenge, as encounter of protein without adjuvant may limit expansion of antigen-specific pro-inflammatory or effector responses; in parallel, adjuvant in the absence of antigen may drive high levels of non-specific, systemic inflammation (Ilyinskii et al., 2014).

Biomaterials can aid to overcome this hurdle, through co-encapsulation or entrapment of cargos in polymer particles or lipid carriers (Ilyinskii et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2018), by tethering signals to the surface of spherical carriers (e.g., gold nanoparticles, polystyrene beads) (Niikura et al., 2013; Tao and Gill, 2015), or via self-assembly of cues into nano- or micro- complexes, virus-like particles, or polyelectrolyte multilayers (Lynn et al., 2015; Tostanoski and Jewell, 2017; Yenkoidiok-Douti and Jewell, 2020) (Figure 5). These approaches have been shown to enhance co-delivery of signals to the same cell, increase uptake by APCs, promote drainage of signals to lymph nodes, and minimize off-target effects. Materials-based approaches have also been engaged to administer several TLRs with antigen (Kasturi et al., 2011; Kuai et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018). A synergistic effect on expansion of IgG was observed when lipoprotein nanodiscs co-assembled antigen with both TLR4 and TLR9 agonists, compared with ad-mixed formulations or particles carrying one TLR agonist alone (Kuai et al., 2018); this effect also appears to translate across materials platforms, as similar synergistic effects of inclusion of multiple TLR agonists have also been observed in polymer nanoparticle-based approaches (Kasturi et al., 2011). This potential to incorporate multiple classes of cargo may be of particular interest for vaccine design for persistent infectious diseases, as many experimental regimens incorporate several signals – viral vector, protein, adjuvant – in different sequences and combinations (Barouch et al., 2018b).

Figure 5:

Advantages of biomaterials in vaccine design. Encapsulation: allows for enhanced cellular uptake of vaccine antigen proteins, nucleic acids or small molecules as well as improved lymphoid organ drainage; Surface presentation: allows improved and regulated presentation of multiple copies of antigens for enhanced immune stimulation; Controlled release: allows for the regulation of the kinetics and availability of immunogens at different times post injection (LNP: lipid nanoparticle; NP: nanoparticle)

Materials science, namely polymer chemistry, has also been employed to tune the kinetics of vaccine and immune cue delivery in vivo. Traditional vaccine approaches deliver a bolus injection, in which a high dose of immunogen is administered and the concentration wanes as the signal is taken up by cells and cleared. In contrast, in next generation approaches that drive in situ expression of vaccine antigen, the bioavailability of the cue or cues correspond to the expression profiles in cells. Importantly, antigen kinetics have been shown to be tightly linked to responses elicited, motivating the development of tools to regulate the timing and duration of antigen delivery in a programmable manner (Cirelli et al., 2019; Irvine et al., 2020). Towards this goal, several approaches explore the use of degradable polymers. For example, polyesters like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) have been extensively employed in the drug delivery field and, more recently, translated to encapsulate and deliver vaccine cargo (Ben-Akiva et al., 2018; Irvine et al., 2020). The degradation rate of these carriers can be controlled through manipulation of polymer composition, including molecular weight, monomer ratio, and chemical end group. The link between antigen and adjuvant release kinetics and the magnitude and speed of immune responses has also recently been demonstrated using a degradable dextran-based microparticle platform (Chen et al., 2018a). Together these examples demonstrate the potential for application of controlled release to magnify or tune immune responses or to develop tools to study the link between signal kinetics and the resultant responses to inform vaccine design.

In addition to exploring biomaterials platforms to encapsulate signals, several groups have demonstrated applications to decorate the surface of a particulate carrier or to engineer a multivalent scaffold to present multiple copies of an antigen (Irvine and Read, 2020; Karch and Burkhard, 2016). This approach may more closely mimic the typical presentation of surface antigens on viruses or bacteria, recapturing a feature of pathogens typically lost in vaccine production. Further, tunable approaches have demonstrated the potential to control the valency and spacing these signals. For example, Kato and colleagues recently demonstrated that high valency presentation of HIV-1 immunogens on nanoparticles dramatically enhanced both the magnitude and breadth of antibody responses compared with low valency presentation of the same immunogen (Kato et al., 2020). The King Lab has also developed a library of self-assembling protein nanoparticles of different architectures (Brouwer et al., 2019; Marcandalli et al., 2019) demonstrated to drive a substantial increase in neutralizing antibody titer compared with soluble immunogen for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). More generally, these approaches demonstrate how nano-assemblies of different structures can be used to capture features of pathogens – for example, the relatively sparse density of envelope spikes on the HIV virion, compared with the tightly packed expression of hemagglutinin in the surface of influenza. This variable can be tuned to study and identify the physical arrangement of cues that is most immunogenic, independent of the typical pathogen architecture.

This concept of harnessing materials to probe fundamental questions about the immune system also extends beyond exploring the role of antigen valency and spacing. As noted above, screening different combinations of signals – antigen, TLR ligand or ligands, STING agonists, etc. – can facilitate the study of how engaging different inflammatory pathways skews resultant T and B cell function. Similarly, carrier size, shape, and stability can impact the persistence and localization of these cues following injection (Chen et al., 2018a; Niikura et al., 2013). Furthermore, several recent papers demonstrate intrinsic immunogenic properties of many materials employed in nano- and micro-scale assemblies, including PLGA, polystyrene, chitosan, alginate, and more (Andorko and Jewell, 2017; Demento et al., 2009; Park and Babensee, 2012; Sharp et al., 2009). These findings underscore the opportunity to study and select a carrier that not only enhances control over in vivo delivery, but also contributes to skew immune responses down a particular path of cell differentiation and expansion. Finally, many of these questions and ideas could be difficult to access without the inclusion of a biomaterial component, suggesting the power and exciting potential of combining engineering and immunology to develop new delivery platforms, inform novel vaccine design, and expand our understanding of the immune system.

Conclusions

Incredible progress has been made in the field of mRNA vaccines in the last decade. Optimization in mRNA design, LNP composition as well as in manufacturing processes have led to mRNA vaccines that are well tolerated and immunogenic in humans, stable, and can be scaled up to hundreds of millions of doses. The use of standardized processes and reagents, the ability to combine multiple mRNA antigens in the same LNP therefore targeting multi-pathogens simultaneously, the lack of vector immunity, and the robust immune responses confirmed in several clinical studies make mRNA vaccines a disruptive technology that may change vaccine development in the incoming years. In addition, due to the relative recent application of mRNA for large scale vaccine applications, there is much room for improvements and new developments.

Adenovirus vector vaccines have also evolved to become promising vaccine platforms. Optimal adenovirus vaccine vector design involves the selection of non-prevalent vector serotypes, and the structural components of Ad vectors can be harnessed and modified for enhanced tropism, efficient transduction and optimal antigen expression. Ad vectors can be developed rapidly and manufactured at commercial scale, and vector potency and stability characteristics support single-shot vaccines that do not require a frozen cold chain. The development of Ad vectors against multiple pathogens illustrates their flexibility and their promise for current and future vaccine applications.

Finally, the application of biomaterials and engineering to enhance control of vaccine delivery has shown promise to enhance vaccine efficacy and to tune the nature of responses elicited. Taken together, these innovations in vaccine science have the potential to address many shortcomings of conventional vaccine technologies and will likely play a major role in the development of future vaccines for both existing and novel pathogens.

References

- Abbink P, Kirilova M, Boyd M, Mercado N, Li Z, Nityanandam R, Nanayakkara O, Peterson R, Larocca RA, Aid M, et al. (2018). Rapid Cloning of Novel Rhesus Adenoviral Vaccine Vectors. J Virol 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbink P, Larocca RA, De La Barrera RA, Bricault CA, Moseley ET, Boyd M, Kirilova M, Li Z, Ng’ang’a D, Nanayakkara O, et al. (2016). Protective efficacy of multiple vaccine platforms against Zika virus challenge in rhesus monkeys. Science 353, 1129–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbink P, Lemckert AA, Ewald BA, Lynch DM, Denholtz M, Smits S, Holterman L, Damen I, Vogels R, Thorner AR, et al. (2007). Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J Virol 81, 4654–4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, Tournev I, Schmidt HH, Coelho T, Berk JL, et al. (2018). Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 379, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Africa Regional Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis, E. (2020). Certifying the interruption of wild poliovirus transmission in the WHO African region on the turbulent journey to a polio-free world. Lancet Glob Health 8, e1345–e1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinc A, Querbes W, De S, Qin J, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Jayaprakash KN, Jayaraman M, Rajeev KG, Cantley WL, Dorkin JR, et al. (2010). Targeted delivery of RNAi therapeutics with endogenous and exogenous ligand-based mechanisms. Mol Ther 18, 1357–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dosari MS, and Gao X (2009). Nonviral gene delivery: principle, limitations, and recent progress. AAPS J 11, 671–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andari JE, and Grimm D (2020). Production, Processing and Characterization of synthetic AAV Gene Therapy Vectors. Biotechnol J, e2000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, Jackson LA, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Chappell JD, Denison MR, Stevens LJ, Pruijssers AJ, et al. (2020). Safety and Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andorko JI, and Jewell CM (2017). Designing biomaterials with immunomodulatory properties for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Bioeng Transl Med 2, 139–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artusi S, Miyagawa Y, Goins WF, Cohen JB, and Glorioso JC (2018). Herpes Simplex Virus Vectors for Gene Transfer to the Central Nervous System. Diseases 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, et al. (2020a). Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden LR, Stieh DJ, Sarnecki M, Walsh SR, Tomaras GD, Kublin JG, McElrath MJ, Alter G, Ferrari G, Montefiori D, et al. (2020b). Safety and immunogenicity of two heterologous HIV vaccine regimens in healthy, HIV-uninfected adults (TRAVERSE): a randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 1/2a study. Lancet HIV 7, e688–e698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahl K, Senn JJ, Yuzhakov O, Bulychev A, Brito LA, Hassett KJ, Laska ME, Smith M, Almarsson O, Thompson J, et al. (2017). Preclinical and Clinical Demonstration of Immunogenicity by mRNA Vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 Influenza Viruses. Mol Ther 25, 1316–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AT, Greenshields-Watson A, Coughlan L, Davies JA, Uusi-Kerttula H, Cole DK, Rizkallah PJ, and Parker AL (2019). Diversity within the adenovirus fiber knob hypervariable loops influences primary receptor interactions. Nat Commun 10, 741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, Kik SV, Weverling GJ, Dilan R, King SL, Maxfield LF, Clark S, Ng’ang’a D, Brandariz KL, Abbink P, et al. (2011). International seroepidemiology of adenovirus serotypes 5, 26, 35, and 48 in pediatric and adult populations. Vaccine 29, 5203–5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, O’Brien KL, Simmons NL, King SL, Abbink P, Maxfield LF, Sun YH, La Porte A, Riggs AM, Lynch DM, et al. (2010). Mosaic HIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nat Med 16, 319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, and Picker LJ (2014). Novel vaccine vectors for HIV-1. Nat Rev Microbiol 12, 765–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, Tomaka FL, Wegmann F, Stieh DJ, Alter G, Robb ML, Michael NL, Peter L, Nkolola JP, Borducchi EN, et al. (2018a). Evaluation of a mosaic HIV-1 vaccine in a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2a clinical trial (APPROACH) and in rhesus monkeys (NHP 13–19). Lancet 392, 232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, Tomaka FL, Wegmann F, Stieh DJ, Alter G, Robb ML, Michael NL, Peter L, Nkolola JP, Borducchi EN, et al. (2018b). Evaluation of a mosaic HIV-1 vaccine in a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2a clinical trial (APPROACH) and in rhesus monkeys (NHP 13–19). The Lancet 392, 232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartok E, and Hartmann G (2020). Immune Sensing Mechanisms that Discriminate Self from Altered Self and Foreign Nucleic Acids. Immunity 53, 54–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Akiva E, Est Witte S, Meyer RA, Rhodes KR, and Green JJ (2018). Polymeric micro- and nanoparticles for immune modulation. Biomater Sci 7, 14–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DI, Reap EA, Katen K, Watson A, Smith K, Norberg P, Olmsted RA, Hoeper A, Morris J, Negri S, et al. (2009). Randomized, double-blind, Phase 1 trial of an alphavirus replicon vaccine for cytomegalovirus in CMV seronegative adult volunteers. Vaccine 28, 484–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer PJM, Antanasijevic A, Berndsen Z, Yasmeen A, Fiala B, Bijl TPL, Bontjer I, Bale JB, Sheffler W, Allen JD, et al. (2019). Enhancing and shaping the immunogenicity of native-like HIV-1 envelope trimers with a two-component protein nanoparticle. Nat Commun 10, 4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard BL, Corder BN, Gordon DN, Pierson TC, and Weaver EA (2020). Characterization of a Species E Adenovirus Vector as a Zika virus vaccine. Sci Rep 10, 3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion CR (2020). Heplisav-B: A Hepatitis B Vaccine With a Novel Adjuvant. Ann Pharmacother, 1060028020962050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Xiang ZQ, Li Y, Kurupati RK, Jia B, Bian A, Zhou DM, Hutnick N, Yuan S, Gray C, et al. (2010). Adenovirus-based vaccines: comparison of vectors from three species of adenoviridae. J Virol 84, 10522–10532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Johnson MM, Collier MA, Gallovic MD, Bachelder EM, and Ainslie KM (2018a). Tunable degradation of acetalated dextran microparticles enables controlled vaccine adjuvant and antigen delivery to modulate adaptive immune responses. J Control Release 273, 147–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Xia P, Li S, Zhang T, Wang TT, and Zhu J (2017). RNA sensors of the innate immune system and their detection of pathogens. IUBMB Life 69, 297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Keiser MS, and Davidson BL (2018b). Viral Vectors for Gene Transfer. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 8, e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YH, Beiss V, Fiering SN, and Steinmetz NF (2020). COVID-19 Vaccine Frontrunners and Their Nanotechnology Design. ACS Nano 14, 12522–12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli KM, Carnathan DG, Nogal B, Martin JT, Rodriguez OL, Upadhyay AA, Enemuo CA, Gebru EH, Choe Y, Viviano F, et al. (2019). Slow Delivery Immunization Enhances HIV Neutralizing Antibody and Germinal Center Responses via Modulation of Immunodominance. Cell 177, 1153–1171.e1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad SJ, and Liu J (2019). Poxviruses as Gene Therapy Vectors: Generating Poxviral Vectors Expressing Therapeutic Transgenes. Methods Mol Biol 1937, 189–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett KS, Edwards DK, Leist SR, Abiona OM, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Gillespie RA, Himansu S, Schafer A, Ziwawo CT, DiPiazza AT, et al. (2020a). SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett KS, Flynn B, Foulds KE, Francica JR, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Werner AP, Flach B, O’Connell S, Bock KW, Minai M, et al. (2020b). Evaluation of the mRNA-1273 Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in Nonhuman Primates. N Engl J Med 383, 1544–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan L (2020). Factors Which Contribute to the Immunogenicity of Non-replicating Adenoviral Vectored Vaccines. Front Immunol 11, 909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw BJ, Jones LB, Bell CR, Kumar S, and Matthews QL (2019). Perspective on Adenoviruses: Epidemiology, Pathogenicity, and Gene Therapy. Biomedicines 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demento SL, Eisenbarth SC, Foellmer HG, Platt C, Caplan MJ, Mark Saltzman W, Mellman I, Ledizet M, Fikrig E, Flavell RA, et al. (2009). Inflammasome-activating nanoparticles as modular systems for optimizing vaccine efficacy. Vaccine 27, 3013–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov JD, and Lacroix-Desmazes S (2020). Noncanonical Functions of Antibodies. Trends Immunol 41, 379–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl HC (2016). Viral vectors as vaccine carriers. Curr Opin Virol 21, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeseth AS, Cejas PJ, Citron MP, Wang D, DiStefano DJ, Callahan C, Donnell GO, Galli JD, Swoyer R, Touch S, et al. (2020). Modified mRNA/lipid nanoparticle-based vaccines expressing respiratory syncytial virus F protein variants are immunogenic and protective in rodent models of RSV infection. NPJ Vaccines 5, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, and Moon JJ (2017). Particulate delivery systems for vaccination against bioterrorism agents and emerging infectious pathogens. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman RA, Fuhr R, Smolenov I, Mick Ribeiro A, Panther L, Watson M, Senn JJ, Smith M, Almarsson, Pujar HS, et al. (2019). mRNA vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 influenza viruses of pandemic potential are immunogenic and well tolerated in healthy adults in phase 1 randomized clinical trials. Vaccine 37, 3326–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jezek Z, and Ladnyi ID (1988). Smallpox and its eradication, Vol 6 (World Health Organization; Geneva: ). [Google Scholar]

- Fields PA, Kowalczyk DW, Arruda VR, Armstrong E, McCleland ML, Hagstrom JN, Pasi KJ, Ertl HC, Herzog RW, and High KA (2000). Role of vector in activation of T cell subsets in immune responses against the secreted transgene product factor IX. Mol Ther 1, 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folegatti PM, Ewer KJ, Aley PK, Angus B, Becker S, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, Bellamy D, Bibi S, Bittaye M, Clutterbuck EA, et al. (2020). Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 396, 467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries CN, Curvino EJ, Chen J-L, Permar SR, Fouda GG, and Collier JH (2020). Advances in nanomaterial vaccine strategies to address infectious diseases impacting global health. Nature Nanotechnology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammon JM, and Jewell CM (2019). Engineering Immune Tolerance with Biomaterials. Adv Healthc Mater 8, e1801419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geall AJ, Verma A, Otten GR, Shaw CA, Hekele A, Banerjee K, Cu Y, Beard CW, Brito LA, Krucker T, et al. (2012). Nonviral delivery of self-amplifying RNA vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 14604–14609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisbert TW, Bailey M, Hensley L, Asiedu C, Geisbert J, Stanley D, Honko A, Johnson J, Mulangu S, Pau MG, et al. (2011). Recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) and Ad35 vaccine vectors bypass immunity to Ad5 and protect nonhuman primates against ebolavirus challenge. J Virol 85, 4222–4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein N, Bockstal V, Bart S, Luhn K, Robinson C, Gaddah A, Callendret B, and Douoguih M (2020). Safety and Immunogenicity of Heterologous and Homologous Two Dose Regimens of Ad26- and MVA-Vectored Ebola Vaccines: A Randomized, Controlled Phase 1 Study. J Infect Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhaniyogi J, and Brewer G (2001). Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Gene 265, 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnell F, Brown A, Capone S, Kopycinski J, Bliss C, Makvandi-Nejad S, Swadling L, Ghaffari E, Cicconi P, Del Sorbo M, et al. (2018). A Novel Vaccine Strategy Employing Serologically Different Chimpanzee Adenoviral Vectors for the Prevention of HIV-1 and HCV Coinfection. Front Immunol 9, 3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett KJ, Benenato KE, Jacquinet E, Lee A, Woods A, Yuzhakov O, Himansu S, Deterling J, Geilich BM, Ketova T, et al. (2019a). Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticles for Intramuscular Administration of mRNA Vaccines. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 15, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett KJ, Benenato KE, Jacquinet E, Lee A, Woods A, Yuzhakov O, Himansu S, Deterling J, Geilich BM, Ketova T, et al. (2019b). Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticles for Intramuscular Administration of mRNA Vaccines. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids 15, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayton EJ, Rose A, Ibrahimsa U, Del Sorbo M, Capone S, Crook A, Black AP, Dorrell L, and Hanke T (2014). Safety and tolerability of conserved region vaccines vectored by plasmid DNA, simian adenovirus and modified vaccinia virus ankara administered to human immunodeficiency virus type 1-uninfected adults in a randomized, single-blind phase I trial. PLoS One 9, e101591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp S, Kreiter S, Selmi A, Simon P, Koslowski M, Huber C, Tureci O, and Sahin U (2006). Modification of antigen-encoding RNA increases stability, translational efficacy, and T-cell stimulatory capacity of dendritic cells. Blood 108, 4009–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobelli-Martinez M, and Nemerow GR (2007). Preferential activation of Toll-like receptor nine by CD46-utilizing adenoviruses. J Virol 81, 1305–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iampietro MJ, Larocca RA, Provine NM, Abbink P, Kang ZH, Bricault CA, and Barouch DH (2018). Immunogenicity and Cross-Reactivity of Rhesus Adenoviral Vectors. J Virol 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyinskii PO, Roy CJ, O’Neil CP, Browning EA, Pittet LA, Altreuter DH, Alexis F, Tonti E, Shi J, Basto PA, et al. (2014). Adjuvant-carrying synthetic vaccine particles augment the immune response to encapsulated antigen and exhibit strong local immune activation without inducing systemic cytokine release. Vaccine 32, 2882–2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine DJ, Aung A, and Silva M (2020). Controlling timing and location in vaccines. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine DJ, and Read BJ (2020). Shaping humoral immunity to vaccines through antigen-displaying nanoparticles. Current Opinion in Immunology 65, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A, and Medzhitov R (2004). Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 5, 987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Coler RN, McCullough MP, Chappell JD, Denison MR, Stevens LJ, et al. (2020). An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman M, Ansell SM, Mui BL, Tam YK, Chen J, Du X, Butler D, Eltepu L, Matsuda S, Narayanannair JK, et al. (2012). Maximizing the potency of siRNA lipid nanoparticles for hepatic gene silencing in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 51, 8529–8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao S, Williams P, Berg RK, Hodgeman BA, Liu L, Repetto G, and Wolff JA (1992). Direct gene transfer into nonhuman primate myofibers in vivo. Hum Gene Ther 3, 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S, Yuzhakov O, Woods A, Deterling J, Hassett K, Shaw CA, and Ciaramella G (2018). Multi-antigenic human cytomegalovirus mRNA vaccines that elicit potent humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Vaccine 36, 1689–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Anderson B, and Pass RF (2012). Prevention of maternal and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol 55, 521–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamen A, and Henry O (2004). Development and optimization of an adenovirus production process. J Gene Med 6 Suppl 1, S184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch CP, and Burkhard P (2016). Vaccine technologies: From whole organisms to rationally designed protein assemblies. Biochem Pharmacol 120, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, and Weissman D (2005). Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 23, 165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariko K, Muramatsu H, Ludwig J, and Weissman D (2011). Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 39, e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, Vaughan HJ, and Green JJ (2018). Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles for Therapeutic Cancer Treatments. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng 9, 105–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasturi SP, Skountzou I, Albrecht RA, Koutsonanos D, Hua T, Nakaya HI, Ravindran R, Stewart S, Alam M, Kwissa M, et al. (2011). Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity. Nature 470, 543–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Abbott RK, Freeman BL, Haupt S, Groschel B, Silva M, Menis S, Irvine DJ, Schief WR, and Crotty S (2020). Multifaceted Effects of Antigen Valency on B Cell Response Composition and Differentiation In Vivo. Immunity 53, 548–563.e548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitonsa J, Ggayi AB, Anywaine Z, Kisaakye E, Nsangi L, Basajja V, Nyantaro M, Watson-Jones D, Shukarev G, Ilsbroux I, et al. (2020). Implementation of accelerated research: strategies for implementation as applied in a phase 1 Ad26.ZEBOV, MVA-BN-Filo two-dose Ebola vaccine clinical trial in Uganda. Glob Health Action 13, 1829829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuai R, Sun X, Yuan W, Ochyl LJ, Xu Y, Hassani Najafabadi A, Scheetz L, Yu MZ, Balwani I, Schwendeman A, et al. (2018). Dual TLR agonist nanodiscs as a strong adjuvant system for vaccines and immunotherapy. J Control Release 282, 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larocca RA, Mendes EA, Abbink P, Peterson RL, Martinot AJ, Iampietro MJ, Kang ZH, Aid M, Kirilova M, Jacob-Dolan C, et al. (2019). Adenovirus Vector-Based Vaccines Confer Maternal-Fetal Protection against Zika Virus Challenge in Pregnant IFN-alphabetaR(−/−) Mice. Cell Host Microbe 26, 591–600 e594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Bishop ES, Zhang R, Yu X, Farina EM, Yan S, Zhao C, Zheng Z, Shu Y, Wu X, et al. (2017). Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Delivery: Potential Applications for Gene and Cell-Based Therapies in the New Era of Personalized Medicine. Genes Dis 4, 43–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemarchand P, Jaffe HA, Danel C, Cid MC, Kleinman HK, Stratford-Perricaudet LD, Perricaudet M, Pavirani A, Lecocq JP, and Crystal RG (1992). Adenovirus-mediated transfer of a recombinant human alpha 1-antitrypsin cDNA to human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89, 6482–6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppek K, Das R, and Barna M (2018). Functional 5’ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 158–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F, Lindgren G, Lin A, Thompson EA, Ols S, Rohss J, John S, Hassett K, Yuzhakov O, Bahl K, et al. (2017). Efficient Targeting and Activation of Antigen-Presenting Cells In Vivo after Modified mRNA Vaccine Administration in Rhesus Macaques. Mol Ther 25, 2635–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Liang F, Thompson EA, Vono M, Ols S, Lindgren G, Hassett K, Salter H, Ciaramella G, and Lore K (2018). Rhesus Macaque Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Demonstrate T Cell Inhibitory Functions and Are Transiently Increased after Vaccination. J Immunol 200, 286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares-Fernandez S, Lacroix C, Exposito JY, and Verrier B (2020). Tailoring mRNA Vaccine to Balance Innate/Adaptive Immune Response. Trends Mol Med 26, 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren G, Ols S, Liang F, Thompson EA, Lin A, Hellgren F, Bahl K, John S, Yuzhakov O, Hassett KJ, et al. (2017). Induction of Robust B Cell Responses after Influenza mRNA Vaccination Is Accompanied by Circulating Hemagglutinin-Specific ICOS+ PD-1+ CXCR3+ T Follicular Helper Cells. Front Immunol 8, 1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MA, and Ulmer JB (2005). Human clinical trials of plasmid DNA vaccines. Adv Genet 55, 25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Zubkova OV, Tukhvatullin AI, Shcheblyakov DV, Dzharullaeva AS, Grousova DM, Erokhova AS, Kovyrshina AV, Botikov AG, et al. (2020). Safety and immunogenicity of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine in two formulations: two open, non-randomised phase 1/2 studies from Russia. Lancet 396, 887–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LL, Suscovich TJ, Fortune SM, and Alter G (2018). Beyond binding: antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 18, 46–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis A (2020). The Old and the New: Prospects for Non-Integrating Lentiviral Vector Technology. Viruses 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz J, Lazzaro S, Habbeddine M, Schmidt KE, Baumhof P, Mui BL, Tam YK, Madden TD, Hope MJ, Heidenreich R, et al. (2017). Unmodified mRNA in LNPs constitutes a competitive technology for prophylactic vaccines. NPJ Vaccines 2, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn GM, Laga R, Darrah PA, Ishizuka AS, Balaci AJ, Dulcey AE, Pechar M, Pola R, Gerner MY, Yamamoto A, et al. (2015). In vivo characterization of the physicochemical properties of polymer-linked TLR agonists that enhance vaccine immunogenicity. Nat Biotechnol 33, 1201–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcandalli J, Fiala B, Ols S, Perotti M, de van der Schueren W, Snijder J, Hodge E, Benhaim M, Ravichandran R, Carter L, et al. (2019). Induction of Potent Neutralizing Antibody Responses by a Designed Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine for Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Cell 176, 1420–1431.e1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruggi G, Chiarot E, Giovani C, Buccato S, Bonacci S, Frigimelica E, Margarit I, Geall A, Bensi G, and Maione D (2017). Immunogenicity and protective efficacy induced by self-amplifying mRNA vaccines encoding bacterial antigens. Vaccine 35, 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda K, Huang J, Zhou T, Sheng Z, Kang BH, Ishida E, Griesman T, Stuccio S, Bolkhovitinov L, Wohlbold TJ, et al. (2019). Prolonged evolution of the memory B cell response induced by a replicating adenovirus-influenza H5 vaccine. Sci Immunol 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]