Abstract

Recent computational methods have enabled the inference of the cell-type-specificity of eQTLs based on bulk transcriptomes from highly heterogeneous tissues. However, these methods are limited in their scalability to highly heterogeneous tissues and limited in their broad applicability to any cell-type specificity of eQTLs. Here we present and demonstrate Cell Lineage Genetics (CeL-Gen), a novel computational approach that allows inference of eQTLs together with the subsets of cell types in which they have an effect, from bulk transcriptome data. To obtain improved scalability and broader applicability, CeL-Gen takes as input the known cell lineage tree and relies on the observation that dynamic changes in genetic effects occur relatively infrequently during cell differentiation. CeL-Gen can therefore be used not only to tease apart genetic effects derived from different cell types but also to infer the particular differentiation steps in which genetic effects are altered.

Keywords: eQTL, cell type, cell lineage

Introduction

As complex diseases are heterogeneous and multifactorial, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revealed numerous genetic loci associated with disease states. One of the fundamental goals of functional genomics studies is to identify the cell-type specificity of genetic effects—that is, to determine the particular cell types in which each genomic locus affects phenotypic diversity. Currently, one successful approach to address this is “eQTL analysis”, in which researchers characterize genomic loci (termed expression quantitative trait loci, in short “eQTLs”) that have an effect on gene expression diversity. As the effect of eQTLs on genes is presumed to reflect a more general functionality of these loci, similarities and differences in eQTL effects between cell types provide important information for the understanding of disease mechanisms.

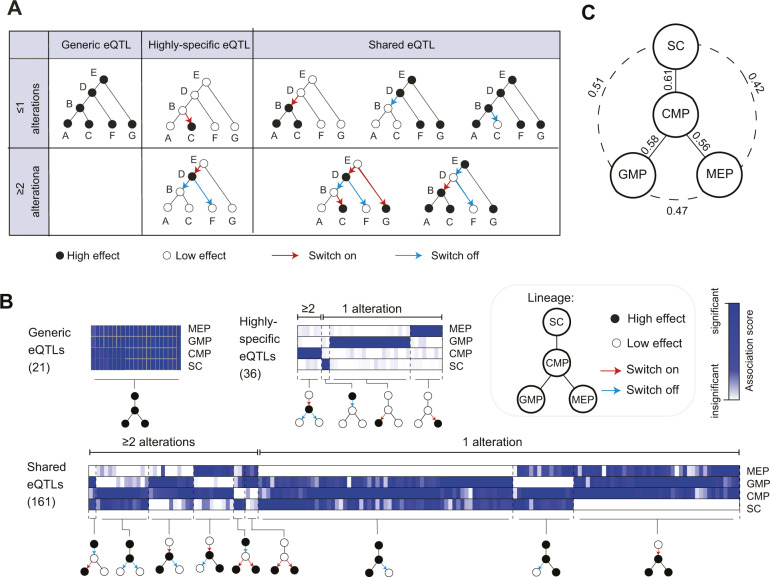

It is well established that cell-type specificity varies substantially between eQTLs (Gerrits et al. 2009; Lonsdale et al. 2013; Westra et al. 2015; Peters et al. 2016; Zhernakova et al. 2017; Aguirre-Gamboa et al. 2020). For example, in eQTL mapping using B cells, monocytes, neutrophils, CD4 and CD8 T cells isolated from peripheral blood of healthy volunteers, eQTLs fall in three categories of cell-type specificity: 45.1% of eQTLs affect all cell types (“generic eQTLs”), 9.9% are highly specific to one cell-type (“highly-specific eQTLs”), and the remaining eQTLs (45%) have an effect in varying subsets of these cell types (“shared eQTLs”) (Peters et al. 2016; Figure 1A). Despite the importance of these characteristics, the cell-type specificity of most genomic loci is yet unknown.

Figure 1.

The cell lineage is informative for eQTL studies. (A) Illustrated are three possible cell-type specificities of eQTLs: either “generic”, “highly specific”, or “shared”. Cell-type specificity can be achieved by either a single alteration (upper row) or two or more alterations (lower row). (B) Cell-type specificity of genes in BXD mice. Analysis of genotyped BXD mice using transcription profiles of four isolated cell types: stem cells (SC), common myeloid progenitors (CMP), megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor (MEP) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP) along a known lineage tree (top right) (data from Gerrits et al. 2009). Heatmaps: association scores of eQTLs (columns) in each cell-type (rows). For each gene, the association scores in this matrix refer to the locus with maximal association score across the cell types. Shown are all eQTLs with p-value < 10−8 in at least one cell type, categorized as either “generic”, “highly-specific”, or “shared”. A relative color scheme was used for highly specific and shared. Cartoons of cell-type specificity of eQTLs are below. The analysis supports the parsimony assumption: one alteration is more prevalent than two or more alterations. (C) Correlation of association scores between each pair of cell types. The correlations are marked next to the edge connecting each pair of cell types.

Cell-type specificity of eQTLs can be obtained from transcriptomes of isolated cell types from each genotyped individual, or alternatively, through single-cell genomics across a population of genotyped individuals (Wijst et al. 2018). However, due to limitations of costs and efforts, such a direct experimental approach is impractical for discovering the cell-type specificity of eQTLs at large scale. As an alternative approach, recent studies proposed to predict the cellular context of eQTLs from bulk genomics data. However, these computational methods were either limited to highly-specific eQTLs (Westra et al. 2015; Zhernakova et al. 2017) or had limited scalability to a large number of cell types (Aguirre-Gamboa et al. 2020) – mainly due to the challenge to cover a large number of possible solutions.

Here we tackle this challenge by integrating genetics and transcriptome data in bulk tissue samples with prior knowledge about the cell lineage tree. It is widely appreciated that the regulatory state of cells persists through multiple differentiation steps. An increasing number of studies have integrated the cell lineage with gene regulatory information to map the particular points of alterations in regulatory programs during differentiation (e.g. hematopoiesis, Bella et al. 2020; Novershtern et al. 2011; Paul et al. 2015). These studies showed that activation of transcriptional programs is not switched off immediately during differentiation, but instead persists in descendant cell types. In accordance with this evidence, we modeled differences in eQTL effects between cell types as a dynamic process in which a single alteration of eQTL effect over the lineage tree is frequent (Figure 1A, top) but multiple alterations of genetic effects along the cell lineage are relatively infrequent (Figure 1A, bottom). As shown in Figure 1A, genetic effects can be either switched on or off during cell differentiation. Using this modeling assumption, we were able to improve the prediction of cell-type specificity of eQTLs from bulk data. We refer to this method as “Cell Lineage Genetics” (CeL-Gen). CeL-Gen is designed to detect both highly-specific and shared eQTLs in a scalable manner, and in addition, it also predicts the particular differentiation steps in which genetic effects are altered. As a proof of principle, we applied CeL-Gen to study cell-type-specificity of eQTLs along the murine hematopoietic lineage tree, focusing on the particular context of influenza virus infection.

Materials and methods

Testing the maximum parsimony assumption

The parsimony assumption was tested on a dataset of expression profiles of four cell types that were isolated from the bone marrow of 25 recombinant inbred mouse lines, called the BXD mouse strains (Gerrits et al. 2009). The samples were log-transformed and quantile normalized. For genes with multiple probes, the probe with the highest standard deviation was used. For each cell type, a gene-locus “association score” was calculated using standard analysis (Shabalin 2012), using genotyping data from the WebQTL dataset (Wang et al. 2003). For each gene, only cis-associated loci were considered (using a permissive distance threshold of 25 M bp), out of which only the best score loci for each gene were used for the remaining analysis.

We focused on gene-locus pairs that attained associations scores (–log p-values) below the significance threshold (, Bonferroni corrected) in at least one cell type. Grouping of pairs based on shared pattern of association over the cell types was performed as follows. First, the “generic effect” group includes all gene-locus pairs that passed one of two criteria: (i) significant associations in all cell types, and (ii) the ratio between worst and best association scores was higher than the mean ratio over all the pairs (0.63). Next, the “highly-specific effect” groups consist of gene-locus pairs in which the ratio between the second-best score and the best score was in the lower 25th (cutoff = 0.3) percentile of ratios (four groups for each of the best-scored cell types). Finally, the remaining gene-locus pairs were clustered into nine groups, referred to as “shared-effect” groups.

The CeL-Gen procedure

A brief overview and the rationale of CeL-Gen appears in the Results section. The CeL-Gen method aims to map the cell-type specificity of eQTL from bulk gene expression data of heterogeneous tissues. For a given genomic locus and a gene expressed in particular heterogeneous tissue, CeL-Gen takes as input the following data: (1) A gene expression vector y, where is the expression of the gene within the tissue from individual . (2) A genotyping vector g, where is the genotype of the locus in individual . (3) A set S={1…C} of all cell types in the tissue, and the known “cell lineage tree” that includes all cell types in S. (4) A cell-type composition matrix PCXN, where is the proportion of cell-type in the tissue of individual . Here we obtain the cell-type composition through deconvolution of the gene expression data (Newman et al. 2015).

The algorithm assumes that the overall genetic variation in gene expression within the heterogeneous tissue reflects a mixture of two distinct genetic effect sizes, each effect size exists in a subset of the cell types. More formally, effect exists in subset whose proportion is , and effect exists in subset S\S1 whose proportion is ( is a constant term):

| (1) |

Thus, the model distinguishes two subpopulations of cells with distinct effect sizes. We refer to this model as the “two-effects model”. An equivalent representation of this two-effects model is a standard locus-gene association with an additional interaction term between the genotype and the proportion of the cell types in subset :

| (2) |

where the coefficient of the interaction term is . This standard representation, which is also referred to as a two-effects model, is practically used throughout this study to calculate the likelihood of each candidate partition of cell types ( and S\S1).

The two-effects model is optimized for each candidate partition of cell types into subsets and S\S1. Among all candidate partitions, the algorithm chooses the partition with the maximal likelihood. As the number of partitions grows exponentially with the number of cell types, CeL-Gen limits the analysis to a set of partitions that are highly likely to appear in biological data. Given the observed parsimonious sequences of alterations in genetic effects through the cell lineage (see Results section), CeL-Gen tests only partitions that are explained by an alteration in effect size in a particular differentiation step (referred to as a “branch”) – that is, one cell-type subset includes the descendants of the branch, and the other subset includes the remaining cell types. Of note, the equivalence between the two representations of the two-effects model (Equation 2) shows that testing a certain cell-type subset is largely interchangeable to testing a subset of the remaining cell types S\S1. Based on this “symmetric” property of the two-effects model, each branch is therefore tested only once, using the descendent of a branch as the subset. Overall, the two-effects model is optimized once for each differentiation branch, and therefore the entire analysis scales linearly with the number of cell types. The output (most-likely) two-effects model provides the particular branch in which alteration in genetic effect occurs, and in addition, the inferred effect sizes for the descendants of that branch () and for the remaining cell types (). The two-effect model generally reflects either highly-specific effect (||=1 and ) or shared effects (||>1 or ).

We further apply likelihood ratio (LR) tests to confirm that the inferred two-effect model indeed improves over a null model of constant effect. For the null model, called “one-effect model”, we added an additional dummy branch connected to the root; such branch reflects a scenario in which all cell types share the same effect size () – either without association () or with a generic effect (). The LR test, therefore, provides the significance of alteration in effect in a specific branch (either shared or highly specific effect) when the null assumption is that the effect is not altered (either generic effect or no effect). Statistical significance is evaluated through theoretical distribution (-2ln(LR)∼ with 1 degree of freedom, based on Wilks theorem) or using permutation tests.

In summary, the CeL-Gen procedure consists of three steps. First, the branch with the maximal likelihood is identified based on a two-effects model. The most-likely branch indicates a certain cell-type specificity, with one effect size in the descendants of the branch and another effect size in all remaining cell types. Second, calculate the maximum likelihood of a one-effect model. Third, an LR test for the statistical significance of the most-likely two-effect model against the most-likely one-effect null model.

Performance analysis

Generation of synthetic data

Synthetic datasets were produced based on the ImmGen gene expression profiles of 16 isolated murine immune cell types, and the known hematopoietic lineage tree of these cell types (Heng et al. 2008; Supplementary Figure S1A). Specifically, each dataset was generated for N individuals in several steps. (1) Generation of cell-type proportions. For each individual, we randomly sampled its cell-type proportions (only for cell types that are included in the cell lineage tree). (2) Genotyping of 1000 genomic loci. Each genomic locus was generated by randomly assigning a minor or major allele to each of the N individuals, assuming that the minor allele frequency (MAF) is . (3) Generation of bulk gene expression profiles of complex tissue samples. Without loss of generality (see “symmetric property” related to Eqs. 1,2), we focused on switch-on scenarios (Supplementary Figure S1A). To this end, we first sampled 1000 genes from the ImmGen data. For each of these genes, the bulk expression in each of the N individuals was generated in four steps. In step 3.1, we randomly selected a genomic locus that would have an effect on the gene, and further selected the particular branch in which the alteration in effect size occurs. In step 3.2, for each individual, we introduced the required genetic effect to the expression profiles of all 16 isolated cell types. Effect b1 was added to descendent cell types of the selected branch from step 3.1, and an effect b2 was added to the remaining cell types, in accordance with the alleles of the underlying locus in each individual. The effect sizes (b1 and b2) were defined as the mean gene expression difference between two genotype groups. Effect sizes were selected based on two-effect ratio parameter (in short, the “effect ratio” parameter). refers to a “switch on” and refers to a “switch off” of genetic effects during differentiation. In step 3.3, we generated the bulk gene expression profile of each individual. For a given individual, this was calculated as a mixture of its profiles of isolated cell types (from step 3.2), weighted by the cell-type proportions in this individual (from step 1). As the last step (3.4), we added noise sampled from a normal distribution with a mean of zero and variance of to the gene expression matrix. Taken together, multiple datasets were analyzed, each was generated using a different combination of six parameters: cohort size (N = 30, 50, 100, 500, 1000), MAF (), type of branch of alteration (either “highly-specific” or “shared” effect), effect sizes in descendants (b1 = 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 10), effect ratio ( and [corresponds to b2 = 0]; switch off with is used in specific cases), and noise level (). Unless stated otherwise, we use a certain default set of parameters (N = 500, , b1 = 4, (switch on), , either using highly-specific or shared effects), and change only one specific parameter.

Based on the selection of the alteration branch, two collections of datasets were generated and analyzed separately (Supplementary Figure S1A): (1) highly specific effects; (2) shared effects. In addition, we used another collection, in which datasets were generated for every possible selection of an alteration branch in the lineage tree. We repeated each simulation setting ten times (altogether, 940 datasets). Furthermore, a collection of datasets with switch-off effects was generated using the same default set of parameters.

Compared methods

We used four different methods, in addition to CeL-Gen. First, the Westra method (Westra et al. 2015), which uses the same regression as in Equation 1, but is a single cell type. Thus, the Westra method calculates a p-value for all possible single cell types. The subset of cell types with significant p-value is used as an inferred cell subset that shares the same effect size. We implemented Westra using python's statsmodels module (Seabold and Perktold 2010), where instead of using the proxy vector described in the original paper, we used the known (synthetically generated) or inferred cell-type proportions (. We used an implementation of the method that best suited the way the synthetic data was generated: with a constant and without a cell-composition term. This setting outperformed alternative implementations (data not shown). Second, Decon-eQTL (Aguirre-Gamboa et al. 2020), which relies on a regression with two terms for each cell-type to model the genetic and non-genetic contribution of the cell-type to the measured expression. We used the published source code of this method (Aguirre-Gamboa et al. 2020). Third, the “Random” method, which uses the same regression as in Equation 1, but is a random subset of the cell types in Fourth, the “generic” method, which also uses the same regression as in Equation 1, but and S\. To evaluate the performance of the methods when cell-type proportions are not available, we performed a preprocessing step of inferring the cell-type proportions for every sample in each dataset. To that end, we used the CIBERSORT algorithm (Newman et al. 2015), which predicts cell-type proportions in a bulk tissue based on reference gene expression of isolated cell types (here, the ImmGen (Heng et al. 2008) profiles of all 16 cell types in Supplementary Figure S2A). We then used the predictions of CIBERSORT as inputs for CeL-Gen, Westra, Decon-eQTL, and Random.

Evaluation of performance

Four evaluation metrics were applied. First, we assessed the ability to discern between non-generic and generic effects. This was calculated using the standard average precision score (AP), which summarizes the precision-recall curve, relying on synthetic datasets in which half of the eQTLs have generic effects, and half of the eQTLs have non-generic effects. We note that Decon-eQTL does not contain a genetic effect term, and therefore only the CeL-Gen and Westra methods were evaluated using this metric.

Second, we assessed the ability to identify the correct branch of alteration in effect size. This was done by comparing the inferred cell-type subset and the correct cell-type subset in which the effect is stronger. Precision and recall for this comparison were calculated while accounting for the structure of the cell lineage tree, as previously suggested (Sokolova and Lapalme 2009). In particular, hierarchical precision is defined as and hierarchical recall is defined as , where is the predicted subtree of cell types downstream the alteration branch for gene-SNP pair i, and is the correct subtree of cell types for gene-SNP pair i. We use the same formulation, originally designed for trees, for and that refer to any subset of cell types (for the compared methods). In accordance, we refer to the resulting AUPR score as “hierarchical AUPR” (hAUPR).

Third, we compared the prediction error of effect sizes. For each locus-gene pair, the effect size of each cell-type was calculated based on the maximum likelihood model. If the model’s p-value was above the significance threshold, all the cell types were assigned a generic effect (the genotype coefficient in the generic model). Otherwise, descendant and non-descendant cell types (relatively to the maximum likelihood branch) were assigned effect size and , respectively. The effect sizes were calculated for multiple significance thresholds, and for each threshold, the mean squared error (MSE) between the true and the predicted effects was calculated. As a final step, for each dataset, we calculated the area under the MSE curve over all the significance thresholds and reported this value for every synthetic dataset. For simplicity, this score is referred to as “MSE”. Of note, because this definition of MSE is not comparable across different effect sizes, MSE was not assessed for the comparisons of synthetic datasets across data parameters of “effect ratio” and “effect in descendants”.

Lastly, we tested the ability of CeL-Gen to correctly identify the direction of alteration (either a switch-on or switch-off). For each dataset, we focused on pairs for which the correct branch of alteration was identified, regardless of the score attained, and calculated the proportion of correctly identified directions out of these pairs (“correct-direction ratio” score).

Analysis of biological data

We analyzed RNA-Seq of whole lung tissue samples obtained from 29 influenza virus-infected Collaborative Cross (CC) recombinant inbred mouse strains (data from Frishberg et al. 2019). The samples were FPKM-normalized (Trapnell et al. 2010) and then log-transformed. We obtained genotyping data from the UNC systems genetics repository (http://csbio.unc.edu/CCstatus). The genotyping was performed using the MegaMUGA array, which includes 77k single nucleotide polymorphic (SNP) markers and is based on the Illumina Infinium platform. The RNA-Seq data were used to infer the cell-type composition in each sample using the CIBERSORT algorithm (Newman et al. 2015). CIBERTSORT takes as input bulk gene expression profiles and a reference collection of transcription profiles from isolated cell types. Here we used profiles of nine isolated cell types that were previously generated using single-cell RNA-Sequencing (scRNA-seq) from the lungs of influenza-infected C57BL/6J mice (Steuerman et al. 2018).

The gene expression, cell composition and the genotyping matrices were then used as inputs for the CeL-Gen and Westra methods. Cel-Gen also utilized the known cell lineage tree. We considered only genes whose variation was greater than zero that had a low Pearson correlation with the proportions of all the cell types (). An association test that relies on the flanking genomic region of each SNP (Mott et al. 2000) was applied, and only genes that attained association p-value under a permissive threshold () were considered. Focusing on cis-associations, we tested associations with a cutoff of 5Mbp; this strict genomic interval was chosen due to the high density of genotyping in the CC strains and the usage a flanking genomic information as part of the association test. We calculated a permutation-based FDR < 0.05 threshold by mixing the identifiers of individuals in the cell-type composition matrix and repeating this process 100 times. Of note, as the number of parameters used by Decon-eQTL is linear with the number of cell types (20 parameters) and the number of genetic backgrounds is relatively small (29 strains), Decon-eQTL could not been applied on this data.

Because diseases with clear immune characteristics are more likely to be related to genes that have an effect in immune cell types, we reasoned that disease-associations can open opportunity to assess the accuracy of predicted cell-type specificity. We conducted the analysis in three steps. (1) For each gene with permutation FDR < 0.05, its set of inferred cell types was classified as either immune or non-immune set. For Cel-Gen, this classification relies on the alteration branch of the relevant cis-eQTL (column 4 in Supplementary Table S1). For the Westra method, we focused only on genes in which all inferred cell types are within the same lineage (either the immune or the non-immune lineage, columns 3 and 4 in Supplementary Table S2). (2) We compiled independent data about gene-disease associations—either based on disease-variant associations (the DisGeNet platform, Piñero et al. 2020), or based on a strong experimental evidence on the role of genes in specific diseases (using the Ingenuity knowledge base). For each gene, its associated diseases either include or do not include immune diseases (columns 5, 6 in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). (3) For each algorithm and each gene-disease repository, a hyper-geometric test was applied to evaluate the over-representation of predicted immune genes (classification from step 1) within known immune-related genes (classification from step 2). The background for each hyper-geometric test is the total number of genes that were classified (either as immune or non-immune) in steps 1 and 2.

Data availability

The data of the BXD mice and the bulk-expression of the influenza virus-infected CC mice datasets are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, accession numbers GSE18067 and GSE117975). SNP genotyping data for the CC mice were obtained from the UNC systems genetics repository (http://csbio.unc.edu/CCstatus). Single-cell RNA-Seq data for influenza virus-infected mice were obtained from GEO (accession number GSE107947). The code for CeL-Gen is available at GitHub repository https://github.com/galynz/CelGen.

Supplementary material is available at figshare : https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13634777.

Results

The cell lineage is informative for eQTL studies

Although the persistence of transcriptional cell states through differentiation trajectories has been shown in various biological contexts (Novershtern et al. 2011; Paul et al. 2015; Tritschler et al. 2019), considerably less attention has been given to the persistence of genetic effects through these dynamic trajectories. In an exploration of the relations between genetic effects and the cell lineage, we analyzed eQTLs that were mapped simultaneously in four isolated murine cell types from the bone marrow (stem cells, common myeloid progenitors (CMP), megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors (MEP) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP) (Gerrits et al. 2009, see the known cell lineage tree in Figure 1B, top right). To roughly determine the cell-type-specificity of genomic regions and to visualize global patterns of cell-type specificity, eQTL analysis was applied on each cell-type separately to construct a matrix of “association scores” for each gene in each cell-type (Figure 1B, Methods). In particular, for each gene, the association scores in this matrix refer to the top-associated genomic locus—namely, the locus with maximal association score across the cell types (Figure 1B).

We found a general sharing of genetic effects between cell types: only 16.5% of the eQTLs are highly-specific, and the remaining are shared between two or more cell types (Figure 1B). In the vast majority of these shared cases (88%), eQTLs are not generic, highlighting the high prevalence of cell-type-specific shared eQTLs. In addition, we found that the correlation of association scores between cell-types coincides with the known cell lineage (Figure 1C), supporting tight relations between genetic effects and the cell lineage tree. To further show the relevance of the cell lineage, we next characterized the branch of alteration in genetic effect for each of the identified shared eQTLs. For simplicity, we first split the eQTLs into 14 groups—each group corresponds to a certain pattern of association scores over the cell types—and then determined the particular branch and direction of alterations (on/off) for each group (Figure 1B, bottom, Methods). For instance, in the group of strong genetic effects in CMP, GMP, and MEP, there is a single “switch-on” of genetic effects in differentiation toward CMP. We observed a general persistence of genetic effects through differentiation trajectories: out of 218 associated genomic loci, the cell-type specificity of 149 loci could be explained by a single branch of alteration. Using comparison to the expected size of each group based on a background independence model, we found that this over-representation of single-switch loci is highly significant (p < 10−16, binomial test). Qualitatively similar results were obtained in additional cutoffs of association scores (e.g. Supplementary Figure S2). Whereas these results are limited to murine cells, human hematopoiesis shows a similar organization (Peters et al. 2016), emphasizing the generality of these findings.

In light of these observations, we reasoned that the observed variation in genetic effects between cell types likely reflects dynamic processes in which frequent alterations are rare. In accordance, our subsequent reconstruction of cell-type specificity assumes a parsimonious sequence of alterations in the genetic effects of genomic loci.

Cell lineage genetics (CeL-Gen) overview

To identify gene-locus associations in each particular cell-type from bulk genomics data, we developed the CeL-Gen method. The method takes as input a large cohort of individuals, where the input for each individual includes: (1) genotyping; (2) bulk expression of genes in a certain tissue; (3) the relative abundance (proportions) of the various cell types in the tissue (it is possible to use computational deconvolution methods to predict cell-type proportions from bulk genomics data (Newman et al. 2015)). In addition, the method also relies on the known cell lineage tree that includes the cell types in the heterogeneous tissue under study. The output is the cell-type specificity of eQTLs: an inferred eQTL for each gene together with its effect size in each cell type, assuming that each eQTL has only two levels of genetic effect sizes, each of which exists in a subset of the cell types (Figure 2A). In searching for the cell-type specificity, CeL-Gen limits the analysis based on the known architecture of the cell lineage. Particularly, rather than testing all cell-type subsets, CeL-Gen tests all differentiation steps (called “branches”) in the lineage tree—each branch partitions the cell types into two subsets (descendants/non-descendants) of distinct effect size. This strategy relies on the understanding that variation in effects typically coincides with the cell lineage and follows the fundamental principle of a parsimonious sequence of alterations (Figure 1BC).

Figure 2.

The CeL-Gen algorithm. (A) An overview of CeL-Gen. CeL-Gen outputs the predicted alteration branch and the effect levels for each cell type. (B) CeL-Gen’s hypothesis testing. The null hypothesis assumes a consistent effect size across all cell types (one effect model), whereas the alternative hypothesis is that there are two distinct levels of effect with a single branch of alteration in effect size (two effects model). Branches of alteration are highlighted in dashed lines.

For each gene-locus pair, the method proceeds in three steps. First, for each branch in the lineage tree, CeL-Gen calculates the likelihood of the data given a model in which the observed inter-individual variation in bulk gene expression is explained by the contribution of two effects—the effects in descendants and non-descendants of the branch (taking into consideration the overall abundance of cells in each of these subsets). As all branches are tested, the analysis covers highly-specific and shared eQTLs that fit a single alteration of effect along the cell lineage tree. Using the likelihoods of these models, we find the most likely branch of alteration along the cell lineage tree. Second, we calculate the likelihood under the null hypothesis that all cell types have the same genetic effect. This is obtained using an auxiliary branch that is added to the root of the tree, such that all cell types are included in one subset. There are two possible interpretations of the inferred null model: either representing the absence of an eQTL (if the inferred effect size is similar to zero) or a generic eQTL (if the inferred effect size is different from zero). In the third step, the statistical significance of the predicted two-effects model (from step 1) is assessed through comparison to the one-effect model (from step 2) using anLR test (Figure 2B). Because the number of tests grows linearly with the number of cell types, genomic loci and genes, CeL-Gen is scalable to large datasets. The Methods section provides full details about the CeL-Gen algorithm.

Benchmarking using synthetic data

To evaluate the performance of CeL-Gen, we compared it with four alternative methods – “Westra”, “Decon-eQTL”, “Random,” and “Generic”. All methods use a similar regression model but differ in the way they choose the best partition of cell-types into two subsets of distinct genetic effects. The “Westra” method (Westra et al. 2015) is focused on the analysis of highly-specific eQTLs—i.e. the method assumes that a high level of genetic effect exists in only one cell type. The Decon-eQTL method (Aguirre-Gamboa et al. 2020) assumes independence between cell-types and infers simultaneously the effect of each of the cell-types using one unified model. By “Random” we refer to a random partitioning of cell-types into two subsets of distinct effect size. Lastly, using the “generic” strategy, the null (generic) model is always selected (Methods). Of note, whereas the compared methods take as input genetics, bulk genomics, and cell-type composition, CeL-Gen is the only method that utilizes the cell lineage tree.

The performance was evaluated using a collection of synthetic datasets that were generated based on real RNA-seq profiles of isolated cell types (data from Heng et al. 2008) with known lineage relations among the cell-types (Figure 3A). Unless stated otherwise, synthetic datasets were constructed under the parsimony assumption of a single switch-on alteration of genetic effects in a certain differentiation step along the known lineage tree (referred to as a “branch of alteration”, or “alteration branch”). Each synthetic dataset was generated using a particular combination of six data parameters—cohort size, MAF, level of noise in gene expression data, the effect size in descendants of the alteration branch, the ratio between the effect sizes in descendant and non-descendants of the alteration branch (termed the “effect ratio”), and the type of alteration that is either “shared” or “highly-specific” (for each eQTL, its branch of alteration is selected based on this parameter, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1A). The benchmarking represents the regular use of Westra, Decon-eQTL, and CeL-Gen on real data: genetics and bulk genomics data are available, whereas the composition of cell-types is computationally inferred from bulk genomics in a preprocessing step (here, deconvolution with CIBERTSORT (Newman et al. 2015); Methods). Running time evaluation is reported in Supplementary Table S3.

Figure 3.

Benchmarking using synthetic data. (A) An overview of synthetic data analysis. (B) Analysis of the ability to discriminate between generic and non-generic eQTLs. The precision and recall curve for the performance of CeL-Gen and Westra (color coding) were calculated for low and high noise level (, and , top and bottom, respectively). The methods were applied when the cell-type composition is either given as input (dashed line) or inferred with deconvolution (solid line). Average precision (AP) scores are reported. (C) Analysis of the ability to identify the correct branch of alteration. Shown is the area under the hierarchical precision and recall curve (hAUPR, y-axis), for different prediction methods (color coded) and across data parameter values (x-axis). Error bars: 95% confidence intervals of hAUPR values. In all cases, cell-type composition was inferred (through deconvolution method). Results are shown for synthetic datasets of shared (top) and highly-specific (bottom) eQTLs. As an example, the significance of improved hAUPR values of CeL-Gen compared to the Westra method are indicated (*p < 10−10, **p < 10−20, T-test). (D) Analysis of the ability to identify the correct effect size. Shown is the mean squared error between the simulated and predicted effect size (MSE, y-axis, with 95% confidence intervals) for different methods (color coding) across data parameter values (x-axis). In all cases, cell-type composition was inferred through deconvolution method. Results are shown for synthetic datasets of shared (top) and highly-specific (bottom) eQTLs. (E) Performance of CeL-Gen positively correlated with the abundance of eQTL-affected cells. Left: the mean hierarchical AUPR of CeL-Gen for each branch of alteration. The performance for each branch appears as color coding of its child (descendant) cell type. Right: the mean hierarchical AUPR (y-axis) for the mean percentage of eQTL-affected cells (x-axis).

We first evaluated the ability to discern between generic and non-generic effects (an “Average Precision” [AP] score) and the ability to pinpoint the correct branch of alteration (a “hierarchical AUPR” [hAUPR] score) (Methods). The analysis shows that CeL-Gen outperforms the compared method in all data parameters, both in its ability to discern between generic and non-generic effects (Figure 3B) and in its ability to identify the correct branch of alteration (Figure 3C). CeL-Gen outperforms the alternative methods not only when applied to highly-specific effects but also in shared effects (Figure 3BC). Moreover, the analysis indicates that CeL-Gen obtains improved performance with a more informative data—in particular, better CeL-Gen performance were obtained with lower noise and with a larger cohort, MAF, effect size in descendants and effect ratio. CeL-Gen outperforms the alternative methods not only when using the inferred (through deconvolution) cell-type composition but also when using the true (simulated) composition of cell types (Supplementary Figure S1BC). As additional support for the validity of CeL-Gen, we evaluated the ability to infer the correct effect size using a mean square error score that integrates multiple significance thresholds (an “MSE” score; Methods). As expected, the MSE of CeL-Gen improves with increasing cohort size, increasing MAF, and decreasing noise (Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure S1D). Whereas this synthetic data analysis is focused on switch-on alterations, a simulation that is focused on switch-off events shows similar findings (Supplementary Figure S3). Together, these results show the advantage of CeL-Gen in cases in which the parsimony assumption holds and further indicate that CeL-Gen could be reliably used even when a prior step of deconvolution is required.

Interestingly, the performance on datasets with shared effects was better than those obtained on datasets with highly-specific effects (Supplementary Figures 3BCD and S1BCD). Given that the analysis is focused on switch-on alterations (i.e. the eQTL-affected cells are downstream to the alteration branch), a plausible explanation for this observation is that it is easier to identify eQTLs whose branch of alteration is upstream to a larger subset of cells. To test this hypothesis, the quality of branch identification was assessed for a switch-on in each branch separately. Consistent with our hypothesis, performance positively correlated with the abundance of eQTL-affected cells (Figure 3E, right). As additional support, earlier alteration branches, which have a larger number of affected cell types, obtained improved performance (Figure 3E, left; Supplementary Figure S1E). As expected, such improved performance has also been found when using the Westra and Decon-eQTL methods (Supplementary Figure S1F).

Lastly, we assessed the ability of CeL-Gen to determine the correct direction of alteration (either switch on or off; a “correct-direction ratio” score, Methods). As expected, both in shared effects and in highly-specific effects, the ability to correctly identify the direction of alteration improved in larger effect sizes, cohort sizes and MAFs, and decreased with higher noise levels (Supplementary Figure S4). Of note, the analysis indicated that when the alteration branch leads to a leaf, switch-on events are more accurately identified than switch-off events. Surprisingly, the opposite trend was observed in the shared-effect datasets.

Analysis of eQTLs in influenza-infected mice

We applied CeL-Gen to data from a cohort of influenza virus-infected mice. All mouse strains were from the collaborative cross and were previously genotyped (http://csbio.unc.edu/CCstatus). Gene expression was derived from the lung tissue at 48 hours post infection (data from Frishberg et al. 2019). The cell lineage tree is detailed in Figure 4A. We focused on 1471 genes whose “generic” association with at least one cis SNP was above a permissive threshold and did not have strong associations with cell-type fractions. The CIBERSORT algorithm (Newman et al. 2015) was used to predict cell-type fractions. Overall, 162 genes with cell-type specific cis eQTLs were identified by CeL-Gen (permutation FDR < 0.05). Out of these genes, 108 genes were specific to a single cell type, whereas the remaining had shared-effect in a combination of cells (Supplementary Table S1). Interestingly, CeL-Gen predicted switch-on events for all these genes, even though no such bias was observed in the synthetic data (Supplementary Figure S4). One possible explanation for this over-representation of switch-on events is that it stems from infection-mediated stimulation, and therefore represents a real biological bias.

Figure 4.

Cell-type-specific eQTLs in influenza-infected mice. (A) The cell lineage tree. Indicated (arrows) are early alteration branches, used in our focused analysis. (B) Quality assessment. Shown is the overlap between predicted (red) and known (blue) immune-cell-type specificity. Top and bottom panels for the CeL-Gen and Westra methods, respectively. Known immune cell-type specificity is based on variant-disease associations. Hypergeometric test P-values are indicated below. (C) Number of genes identified by Cel-Gen, Westra, and both. Significant overlap between CeL-Gen and Westra are indicated as asterisks (Fisher exact test). Only cell-type combinations that are consistent with the cell lineage tree are shown. Abbreviations: CMP -common myeloid progenitors; CLP—common lymphoid progenitors; END—endothelial cells; EP—epithelial cells; MPS—mononuclear phagocyte system; GN—granulocytes; LEC—lymphatic endothelial cells; BEC—blood endothelial cells; NK—natural killer cells; T—T cells; B—B cells.

We have shown improved performance in earlier alterations, which have a larger number of affected cell types (Figure 3E). In accordance, we focused on three alteration branches that are at the top of the lineage tree: the incoming edge to the non-immune and immune (myeloid and lymphoid) lineages (arrows, Figure 4A). Switch-on events in these branches were inferred by Cel-Gen in 41 genes, particularly 27 and 14 genes in the immune and non-immune lineages, respectively. Thus, based on the inferred specificity of eQTL effects, 27 genes have an immune-specific role and 14 genes have a specific role in non-immune cell types.

To assess the inferred classification of genes as either immune or non-immune factors we used independent data of gene-disease associations. We hypothesized that if the immune/non-immune classification of CeL-Gen is correct, then genes with an inferred immune role would be enriched with a known role in immune-related diseases. To test this, we used the ontology of variant-disease associations based on genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and further grouped diseases into two types – (i) diseases with clear immunological characteristics, including autoimmune (e.g. SLE) and inflammatory (e.g.sepsis)diseases, referred to as “immune disease”; and (ii) any other type of disease, referred to as “non-immune disease” (Methods). Overall, 18 of the 41 cis-associated variants had known disease associations (Supplementary Table S1). We found a significant overlap between genes known to be associated with immune diseases and genes inferred by CeL-Gen as genes functioning in immune branches (p < 0.007, hyper-geometric test; Figure 4B [top]). In particular, out of the genes known to be associated with immune diseases, the majority (9/10; 90%) were inferred by CeL-Gen as genes functioning in immune branches; while for the genes known to be associated with non-immune diseases, only 50 (4/8) were inferred to function in immune branches. Similar results, albeit non-significant, were obtained when using expert knowledge about gene-disease associations (the Ingenuity knowledge base; Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S5A).

We note that even though genes with highly-specific eQTLs were not the focus of this biological interpretation, they can obviously be of interest (Supplementary Table S1). For example, CeL-Gen predicted that Klra7, which participates in the activation of Natural Killer (NK) cells (Schenkel, et al. 2013), have an NK-specific eQTL (chr6:126770472bp). Another interesting example is the Naip3 gene. CeL-Gen predicted an NK-specific eQTL that have an effect on the expression of Naip3 (chr13:101158080bp). Naip3 is a member of the NAIP (NLR family, apoptosis inhibitory protein) family in mice, which are known to be upstream sensors of NLRC4 inflammasome (Man and Kanneganti 2015). Although the NLRC4 inflammasome is mostly characterized in the context of bacterial infection, recent studies have shown that the inflammasome can react to other stimuli (Liu & Chan, 2014; Sellin et al. 2015). In light of the fact that the function of Naip3 is yet undetermined and the fact that the NLRC4 inflammasome is known to have important cell type-specific functions (Man and Kanneganti 2015), it would be interesting to further investigate the NK-specific role of Naip3 in the context of influenza infection.

Comparison of Cel-Gen to the Westra method highlights the utility of Cel-Gen in identifying cell-type specificity of eQTLs. Application of Westra on the influenza-infection data provided 166 genes (permutation FDR < 0.05), 90 of which were affected in multiple cell types and the remaining were affected only in a single cell-type (Supplementary Table S4). The highly specific effects predicted by the Westra method were largely consistent with Cel-Gen’s predictions (Figure 4C), providing indication for the robustness of cell-type-specificity predictions. Interestingly, despite the high prevalence of a single genetic switch in biological data (Figure 1 and Peters et al. 2016), only 3 (3.3%) of the shared effects predicted by Westra were consistent with a single switch (Supplementary Table S4) – highlighting the advantage of CeL-Gen for eQTLs with a single switch. Finally, only CeL-Gen’s prediction (but not Westra’s predictions) were corroborated with independent data; for instance,a non-significant overlap(p > 0.25) for Westra and a significant overlap (p < 0.007) for CeL-Gen when using comparisons to the GWAS annotation (hyper-geometric test, Figure 4B [bottom]; see also Supplementary Figure S5B).

Discussion

In this report, we show that the regulatory effects of eQTLs largely persist during differentiation steps and that alterations in effect sizes are considerably less frequent (Figure 1), in agreement with previous observations (Peters et al. 2016). Cells gradually become fully differentiated along the cell lineage tree, and it is therefore expected that the effect of eQTLs would persist along differentiation trajectories, depending on changes in specific functionalities (Bella et al. 2020; Novershtern et al. 2011; Paul et al. 2015). Thus, biological data indicates that the cell-type specificity of eQTLs is largely explained by a parsimonious sequence of alterations in eQTL effects along the cell lineage tree. This is the basis for our new computational method—CeL-Gen—described here.

Despite the importance of cellular context, methods to identify the cell-type-specificity of eQTLs in a scalable manner were largely missing. Experimental methods that are based on transcription profiling of sorted cells (Heng et al. 2008; Steuerman et al. 2018), across multiple genetic backgrounds, are limited due to the fact that the binding efficiency of antibodies depends on genetics (e.g.CD45, CD43, Sca-1, IA-IE, and Ly6c, Dubovik et al. 2018). As an alternative, current computational methods can predict the cell-type-specificity of eQTLs from data in bulk tissues (Westra et al. 2015; Aguirre-Gamboa et al. 2020). A main challenge of these methods is the large number of possible solutions, which increases exponentially with the number of cell types. To address this, here we developed the CeL-Gen method, which relies on the observation that a parsimonious sequence of eQTL alterations is a reasonable assumption (Figure 2). This way, CeL-Gen addresses the need for an accurate and scalable prediction of shared and highly specific eQTLs. In addition, CeL-Gen goes beyond the standard prediction of cell-type specificity by highlighting the particular differentiation steps in which genetic effects have likely been changed. Encouraged by the high performance of CeL-Gen (Figure 3), we used the method to identify cell-type-specificity of genetic effects during lung infection (Figure 4), thereby providing a starting point for future experimental studies.

The analysis of biological data provides potentially important insights into host-pathogen interactions. Although Cel-Gen is not biased to switch-on events (Supplementary Figure S4), the prevalence of switch-on and switch-off events in biological data might differ. Indeed, only switch-on events were found during influenza infection. This is in contrast to the presence of switch-off events in steady state (unstimulated, Figure 1). This analysis suggests that the differentiation process during influenza virus infection gives rise to an “ultra-variable” transcriptional state. This agrees with previous observations that have shown a higher variation in the quantity of immune cells during the course of infection compared to steady state (e.g. for monocytes and macrophages; Frishberg et al. 2019). Taken together, these findings suggest parallels between cellular diversity (in quantities of cells) and cell-intrinsic diversity (in the molecular state of cells) during infection, with a higher diversity during infection compared to steady state. Such a multi-layered diversity could be advantageous in host-pathogen interactions, because specific genetic backgrounds are likely better suited to defend against specific pathogens.

Our methodology offers several future directions in the field of genetic genomics. First, the simplifying assumption of a single alteration of genetic effects leads to erroneous predictions in other scenarios, including scenarios of multiple alterations of genetic effects, multiple genetic effect sizes, and gradual changes in effect sizes. Thus, future methods are needed to provide a framework to cover a wider range of eQTLs. Second, given that CeL-Gen’s computational time depends linearly on the number of cell types, its time complexity is scalable to a higher resolution of the cell lineage tree. As scRNA-seq datasets provide a high-resolution map of cell differentiation (Tritschler et al. 2019), and recent deconvolution methods can effectively decompose bulk tissues at high resolution (Frishberg et al. 2019), we anticipate that methods like CeL-Gen will be utilized to explore the underlying temporal dynamics of genetic effects during cell-differentiation processes.

Finally, another application of interest is to predict the particular cell types in which gene expression translates between genetic variation and complex traits. Causality testing methods (Schadt et al. 2005) identify the relations between genetics, gene expression, and complex traits. However, as most previous attempts have used bulk transcriptomes (Schadt et al. 2005, 2008; Pickrell et al. 2010; Bahcall 2015), such methods could not determine the particular cell types in which genetic variation propagates into phenotypic diversity. The alternative strategy to infer eQTLs (and causality) from scRNA-seq data is not yet mature (e.g.Wijst et al. 2020) and the application of these methods to isolated cell types is typically limited to one or a few cell types (Gat-Viks et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2014). Although CeL-Gen was not designed for causality testing, many of its components can be used to explore whether eQTLs have an impact on clinical outcomes through their effect in specific cell types.

Funding

This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) Grant 288/16, and by European Research Council grant 63788. G.Y and Y.S were supported by the Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics at Tel-Aviv University. IGV is a Faculty Fellow of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics at Tel Aviv University.

References

- Aguirre-Gamboa R, de Klein N, di Tommaso J, Claringbould A, van der Wijst MG, BIOS Consortium, et al. 2020. Deconvolution of bulk blood eQTL effects into immune cell subpopulations. BMC Bioinformatics. 21:243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahcall OG. 2015. GTEx pilot quantifies eQTL variation across tissues and individuals. Nat Rev Genet. 16:375–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella DJD, Habibi E, Yang S, Stickels RR, Brown J, et al. 2020. Molecular logic of cellular diversification in the mammalian cerebral cortex.bioRxiv.doi: 10.1101/185439 (Preprint posted July 02, [Google Scholar]

- Dubovik T, Starosvetsky E, LeRoy B, Normand R, Admon Y, et al. 2018. Architecture of a multi-cellular polygenic network governing immune homeostasis.bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/256073 (Preprint posted September 23, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Frishberg A, Peshes-Yaloz N, Cohn O, Rosentul D, Steuerman Y, et al. 2019. Cell composition analysis of bulk genomics using single-cell data.Nat Methods. 16:327–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gat-Viks I, Chevrier N, Wilentzik R, Eisenhaure T, Raychowdhury R, et al. 2013. Deciphering molecular circuits from genetic variation underlying transcriptional responsiveness to stimuli.Nat Biotechnol. 31:342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrits A, Li Y, Tesson BM, Bystrykh LV, Weersing E, et al. 2009. Expression quantitative trait loci are highly sensitive to cellular differentiation state, (G. Gibson, Ed. PLoSGenet. 5:e1000692.). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng TSP, Painter MW, Elpek K, Lukacs-Kornek V, Mauermann N, The Immunological Genome Project Consortium, et al. 2008. The immunological genome project: Networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 9:1091–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MN, Ye C, Villani AC, Raj T, Li W, et al. 2014. Common genetic variants modulate pathogen-sensing responses in human dendritic cells. Science (80. 343:1246980–1246980.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Chan C.. 2014. IPAF inflammasome is involved in interleukin-1β production from astrocytes, induced by palmitate; implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol.Aging. 35:309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, Phillips R, Lo E, et al. 2013. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project.Nat Genet. 45:580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man SM, Kanneganti TD.. 2015. Regulation of inflammasome activation. Immunol Rev. 265:6–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott R, Talbot CJ, Turri MG, Collins AC, Flint J.. 2000. A method for fine mapping quantitative trait loci in outbred animal stocks.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97:12649–12654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, et al. 2015. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 12:453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novershtern N, Subramanian A, Lawton LN, Mak RH, Haining WN, et al. 2011. Densely interconnected transcriptional circuits control cell states in human hematopoiesis. Cell. 144:296–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul F, Arkin Y, Giladi A, Jaitin DA, Kenigsberg E, et al. 2015. Transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment in myeloid progenitors.Cell. 163:1663–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JE, Lyons PA, Lee JC, Richard AC, Fortune MD, et al. 2016. Insight into genotype-phenotype associations through eQTLmapping in multiple cell types in health and immune-mediated disease. PLoSGenet. e1005908.12: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell JK, Marioni JC, Pai AA, Degner JF, Engelhardt BE, et al. 2010. Understanding mechanisms underlying human gene expression variation with RNA sequencing.Nature. 464:768–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñero J, Ramírez-Anguita JM, Saüch-Pitarch J, Ronzano F, Centeno E, et al. 2020. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 48:D845–D855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadt EE, Lamb J, Yang X, Zhu J, Edwards S, et al. 2005. An integrative genomics approach to infer causal associations between gene expression and disease.Nat Genet. 37:710–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadt EE, Molony C, Chudin E, Hao K, Yang X, et al. 2008. mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver (G. Abecassis, Ed). PLoSBiol. 6:e107.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel AR, Kingry LC, Slayden RA.. 2013. The Ly49 gene family. A brief guide to the nomenclature, genetics, and role in intracellular infection.Front Immunol. 4: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabold S, Perktold J.. 2010. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference. 2010.

- Sellin ME, Maslowski KM, Maloy KJ, Hardt WD.. 2015. Inflammasomes of the intestinal epithelium.Trends Immunol. 36:442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalin AA. 2012. Matrix eQTL: ultra fasteQTL analysis via large matrix operations. Bioinformatics. 28:1353–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova M, Lapalme G.. 2009. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 45:427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Steuerman Y, Cohen M, Peshes-Yaloz N, Valadarsky L, Cohn O, et al. 2018. Dissection of influenza infection in vivo by single-cell RNA sequencing.Cell Syst. 6:679–691. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, et al. 2010. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 28:511–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritschler S, Büttner M, Fischer DS, Lange M, Bergen V, et al. 2019. Concepts and limitations for learning developmental trajectories from single cell genomics.Dev. 146:dev170506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Williams RW, Manly KF.. 2003. WebQTL: Web-based complex trait analysis. NI. 1:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HJ, Arends D, Esko T, Peters MJ, Schurmann C, et al. 2015. Cell specific eQTLanalysis without sorting cells.PLoSGenet. 11:e1005223. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijst MGP, van der DH, de Vries HE, Groot G, Trynka CCHon, et al. 2020. The single-cell eQTLGen consortium.Elife. 9: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijst MGP, Van Der H, Brugge DH, De Vries P, Deelen MASwertzLifeLines Cohort Study, et al. 2018. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies celltype-specific cis-eQTLs and co-expression QTLs. Nat Genet. 50:493–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhernakova DV, Deelen P, Vermaat M, Van Iterson M, Van Galen M, et al. 2017. Identification of context-dependent expression quantitative trait loci in whole blood.Nat Genet. 49:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the BXD mice and the bulk-expression of the influenza virus-infected CC mice datasets are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, accession numbers GSE18067 and GSE117975). SNP genotyping data for the CC mice were obtained from the UNC systems genetics repository (http://csbio.unc.edu/CCstatus). Single-cell RNA-Seq data for influenza virus-infected mice were obtained from GEO (accession number GSE107947). The code for CeL-Gen is available at GitHub repository https://github.com/galynz/CelGen.

Supplementary material is available at figshare : https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.13634777.