Abstract

For many, college is a period of transition, marked with acute stress, threats to success, and decreases in self-efficacy. For certain groups of students, the risk of these poor outcomes is elevated. In this study, 348 students from a large residential university in the western United States were surveyed to understand the role of psychological flexibility and inflexibility on self-efficacy and the potential moderating impact of year in college and underrepresented racial minority (URM) status. Results indicated that students who are psychologically flexible reported greater college self-efficacy, whereas students who are psychologically inflexible reported lower college self-efficacy. The impact of psychological inflexibility on self-efficacy was moderated by URM status and year in school; psychological inflexibility had a stronger impact on URM students’ self-efficacy than non-minority students, and psychological inflexibility had a greater effect on college students starting college as opposed to students who had been enrolled for multiple years.

Keywords: values affirmation, stereotype threat, social belonging, participant engagement

Completing a postsecondary education has long been a mechanism for social mobility (Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, Johnson, & Covarrubias, 2012), has essentially replaced a high school diploma as a vital tool for becoming economically self-sufficient (Kuh, Cruce, Shoup, Kinzie, & Gonyea, 2008), and is one of the strongest predictors of higher socioeconomic status (Bowen, Kurzwell, Tobin, & Pichler, 2006). A college degree is associated with multiple cognitive, social, and economic long-term benefits for individuals and these benefits are often passed down to future generations, and ultimately benefit the community and society at large (Kuh et al., 2008).

Threats to student success

The experience of college is often a stressful time (Bayram & Bilgel, 2008). For most students, the transition to college coincides with the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. This developmental period is marked with students finishing secondary school, moving from their parents’ home, and becoming legal adults (Arnett, 2000). Navigating these life transitions, expectations, and changes in responsibility is often fraught with stress and can have a negative impact on students’ wellbeing (Arnett, 2000; Conley, Kirsch, Dickson, & Bryant, 2014; Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004). Empirical research supports this transition as a vulnerable period - compared to students in their later years of college, students in their first or second year of college experience poorer psychological health, such as higher stress, anxiety and depression (Bayram & Bilgel, 2008; Sher, Wood, & Gotham, 1996; Towbes & Cohen, 1996). Additionally, emerging research suggests that student wellbeing is particularly susceptible during the beginning of college, as students’ reported levels of psychological and social wellbeing (e.g. feelings of connection and belonging) decline significantly over their first semester of college and do not recover during the second semester (Conley et al., 2014). This trend may, in part, serve as an explanatory mechanism for why many students do not return for their second year of college. In 2013, only 80% of first-time, full-time students enrolled in a four-year institution returned to the same school the next fall and the graduation rate (within six years) for first-time, full-time students enrolled in a four-year institution in 2013 was 59% (National Center for Education Statistics, 2015).

Groups at risk.

While evidence suggests that the majority of college students experience decreases in wellbeing as they make the transition to college, certain groups of students including: underrepresented racial minorities (URM; Bali & Alvarez, 2003; Brown & Lee, 2005; Oates, 2009; Steele-Johnson & Leas, 2013), first-generation students (Pascarella, Pierson, Wolniak, & Terenzini, 2004; Stephens, Hamedani, & Destin, 2014), and sexual minorities (Rankin, 2005) experience increased stress and risks for compromised academic performance and persistence to graduation. The experience of stigma is one explanation for the increase in stress. Stigma involves stereotyping, labeling, and status loss (Link & Phelan, 2001) and specific groups are especially affected by stigma, such as URM (Williams & Mohammed, 2009), sexual minorities (Meyer, 2003), people of unhealthy weight (Puhl & Heuer, 2009), and individuals who struggle with poor mental health (Rüsch, Angermeyer, & Corrigan, 2005). The literature further suggests that lower academic performance among certain minority groups results from encountering stigma and the fear of conforming to a negative social stereotype about an individual’s group (Steele, 1997; Steele & Aronson, 1995; Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002).

In a study of college student test performance, researchers found women performed significantly lower than men on an assessment when participants were informed that their scored would be indicative of their math ability (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999; Steele et al., 2002); however, when the test was not given any description, there was no gender difference in performance. This suggests women’s academic performance may be compromised in environments where there is an expectation, either implicit or explicit, for gender differences to emerge (i.e. STEM fields). Similarly, URM students appear to be at risk for lower academic performance due to stereotypes and stigma, as evidenced by Brown and Lee’s (2005) work that found URM students with high levels of stigma consciousness have significantly lower GPAs than URM students with low levels of stigma consciousness. Additionally, there is a wealth of evidence that suggests that URM students do not perform as well academically when encountering negative stereotypes due to the added pressure to not confirm these negative views (stereotype threat; Aronson & Inzlicht, 2004; Steele & Aronson, 1995; Steele et al., 2002). For a college student, the combined effect of belonging to both a marginalized group and a group for whom there is a threat of judgment and treatment emerging from a widely held group stereotype may amplify risk for poor academic performance, and ultimately, a lower likelihood of persisting to degree in college (Steele et al., 2002).

Self-Efficacy

Another possible way to account for differing levels of performance among college students is to examine differences in efficacious beliefs. Self-efficacy refers to an individuals’ beliefs about his or her abilities and capacities to accomplish tasks and goals (Burnette, Pollack, & Hoyt, 2010). Research demonstrates a positive relationship between college student self-efficacy and both academic performance and adjustment to college (Brady-Amoon & Fuertes, 2011); furthermore, self-efficacy is linked to both intention to return to college the next year (Torres & Solberg, 2001) and actual persistence to graduation (Wright, Jenkins-Guarnieri, & Murdock, 2013). Students who report higher levels of optimism at the start of the first semester of college reported less stress and depression during the first semester (Brissette, Scheier, & Carver, 2002). It seems that students who begin college with a more favorable outlook have a buffer of resources to protect against threats to success. Given the important associations among academic performance, persistence, and self-efficacy, it is critical to understand how other factors influence this relationship.

Psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, and self-efficacy.

Psychological flexibility and inflexibility are useful processes to consider in the context of self-efficacy. Psychological flexibility refers to people’s capacity to alter their behavior to align with their values to persist in the face of challenges (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). Students who are psychologically flexible are more likely to persevere and accomplish college-related tasks in spite of obstacles that they encounter. Psychological inflexibility, conversely, relates to experiential avoidance, which is a resistance to undesirable or stigmatizing thoughts that often prevents individuals from persisting in behaviors that support their values (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). It is important to recognize that, while similar, psychological flexibility and inflexibility are not merely different ends of the same continuum, and are indeed unique constructs both theoretically and empirically (Levin, Lillis, Luoma, Hayes, & Vilardaga, 2014). It can be helpful to think of psychological inflexibility as a risk factor and psychological flexibility as a protective factor. Risk factors increase the likelihood of a negative outcome and protective factors moderate or negate an already present risk (Stone, Becker, Huber, & Catalano, 2012). Individuals who are psychologically inflexible and withdraw from situations, as opposed to persisting in a direction that is important to them, are at a greater risk for psychological distress (Kashdan, Barrios, Forsyth, & Steger, 2006). On the other hand, individuals who are psychologically flexible are able to make adjustments and overcome barriers and risks they encounter to direct their behaviors towards a valued goal (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). In terms of academic performance, students with greater psychological inflexibility are likely to be less adaptive to challenges, more focused on avoiding the difficult feelings of potential failure that accompany those challenges, and have fewer resources available to dedicate to their wellbeing. For example, in order to avoid the accompanying anxiety, psychologically inflexible students may avoid studying, even if they value hard work and academic success, which would negatively impact their academic success. Students who are psychologically flexible are more likely to persevere when a challenge arises. A relevant example here would be a student who does not perform well on their first exam. As opposed to starting to avoid the class in the interest of not experiencing negative feelings, they strengthen their resolve and become more dedicated to the course in the interest of improving their grades. Psychological flexibility is thus particularly important for students who are at higher risk for academic failure.

Though scholars suggest emerging adulthood is a positive experience for most people, for some, working through identity challenges and greater independence culminate in a “quarter-life crisis” (Arnett, 2007), where behaving in alignment with values may be more difficult and psychological inflexibility more likely. Marginalized groups in particular appear to be at an increased risk for psychological inflexibility as past research demonstrates that higher levels of psychological inflexibility result from encountering stereotypes and stigma (Gold, Dickstein, Marx, & Lexington, 2009; Lillis, Luoma, Levin, & Hayes, 2010; Masuda & Latzman, 2011). It is therefore important to investigate the role of psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, and college self-efficacy among a racially and ethnically diverse sample of college students.

The Present Study

Research questions.

The purpose of this study is to investigate associations among psychological flexibility/inflexibility and college self-efficacy. Furthermore, we wish to investigate 1) if the association between psychological flexibility/inflexibility and college self-efficacy is moderated by URM status and 2) if the association between psychological flexibility/inflexibility and self-efficacy is moderated by year in college.

Aim 1.

The first aim of this study will investigate the association between psychological flexibility and inflexibility and self-efficacy among college students by testing the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Psychological flexibility and inflexibility are directly associated with self-efficacy; psychological flexibility will be positively associated with college self-efficacy and psychological inflexibility will be negatively associated with college self-efficacy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Hypothesis 1

Aim 2.

The second aim of this study will investigate the moderating impacts of 1) year in college and 2) minority status on self-efficacy by testing the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 2.

The magnitude of the association of psychological inflexibility with self-efficacy will be moderated by URM status and year in school. Psychological inflexibility will be more strongly related to college self-efficacy for URM students and college students early in their college careers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Hypothesis 2

Hypothesis 3.

The magnitude of the association of psychological flexibility with self-efficacy will be moderated by URM status and year in school. Psychological flexibility will be more strongly related to college self-efficacy for URM students and college students early in their college careers (see Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Hypothesis 3

Method

Procedure

We recruited participants from a large residential university in the western United States through the university’s student information portal, which is accessible to the entire student body. Four-thousand randomly selected undergraduate students received emails with a link to an online survey. The online survey was anonymous, collecting no self-identifying information. Upon completion of the survey, students had the choice to be entered in a gift card lottery, which included one $75 gift card, one $60 gift card, five $45 gift cards, ten $30 gift cards and twenty $15 gift cards to a book and clothing store. If students wished to be entered into the lottery, they could click on a link at the end of the survey with the first author’s email address and provide their names and contact information. The university IRB approved the study and the procedure was consistent with IRB guidelines.

Participants

Five-hundred fifty-two students started the survey with 348 completing the survey (response rate of 8.7%). Of the participants who at least started the survey, 114 self-identified as male, 232 as female, and one as transgender (205 did not report gender; see Table 1 for demographic information). The mean age of participants was 20.7 and ranged from 18 to 50. One participant reported their age as 92, but this was presumed to be an error, and subsequently the participant was not included in calculating the mean age. Participants’ year in college ranged from starting their first year to starting their fourth year (1st year N = 87, 2nd year N = 97, 3rd year N = 79, 4th year N = 81). Participants primarily identified as White/Caucasian (61.7%), Latinx Chicano/a, Hispanic (12.8%), and Asian (8.6%). The remaining 16.9% identified as multiracial/biracial, Black/African American, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian. Race and ethnicity of participants was fairly consistent with the demographics of the university at large (66.3% White; 10.6% Latinx, Chicano, Hispanic; 5.3% Asian). Students identified their race/ethnicity either through selecting a single option in the survey or indicating their race through the qualitative comments option given to them in the survey.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Overall | White/Caucasian | Minority | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age | ||||||

| Overall | 342 | 100.0 | 228 | 100.0 | 106 | 100.0 |

| 18.0 | 38 | 11.1 | 22 | 9.7 | 12 | 11.3 |

| 19.0 | 93 | 27.2 | 64 | 28.3 | 26 | 24.5 |

| 20.0 | 81 | 23.7 | 51 | 22.6 | 29 | 27.4 |

| 21.0 | 71 | 20.8 | 45 | 20.0 | 24 | 22.6 |

| 22.0 | 35 | 10.2 | 27 | 12.0 | 8 | 7.6 |

| 23–50 | 24 | 7.0 | 17 | 7.4 | 7 | 6.6 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Overall | 347 | 100.0 | 228 | 100.0 | 109 | 100.0 |

| Female | 232 | 66.9 | 146 | 64.0 | 80 | 73.4 |

| Male | 114 | 32.9 | 81 | 35.5 | 29 | 26.6 |

| Transgender | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | ||

| Year of Study | ||||||

| Overall | 344 | 100.0 | 228 | 100.0 | 106 | 100.0 |

| 1.0 | 87 | 25.3 | 54 | 23.7 | 29 | 27.4 |

| 2.0 | 97 | 28.2 | 69 | 30.3 | 27 | 25.5 |

| 3.0 | 79 | 23.0 | 51 | 22.4 | 24 | 22.6 |

| 4.0 | 81 | 23.5 | 54 | 23.7 | 26 | 24.5 |

| URM Status | ||||||

| Overall | White/Caucasian | URM | ||||

| Overall | 337 | 100.0 | 228 | 67.7 | 109 | 32.3 |

Variable Ns across demographic variables resulted from missing data (e.g. some participants reported their gender but not race).

Measures

College self-efficacy.

Our outcome variable was college self-efficacy as measured by the College Self Efficacy Instrument (CSE; Solberg, O’Brien, Villareal, Kennel, & Davis, 1993). This scale is used to measure the degree to which students believe they are able to successfully complete various college-related tasks. Students indicated the degree to which they were confident they could complete various tasks on an 11-point, Likert scale, from “1” (not confident at all) to “11” (extremely confident). The eighteen-item instrument asks questions related to course efficacy (7 items; e.g., doing well on exams), social efficacy (8 items; e.g., making new friends), and roommate efficacy (3 items; e.g., getting along with roommates). Two course efficacy items were added to the original scale (“Get an A in a difficult course,” and “Read and understand difficult course material”), with the intent of capturing students’ confidence in performing under challenging academic circumstances, resulting in 20 total items and nine items for course efficacy. For all items, higher scores reflect greater confidence in succeeding in the various domains. The CSE has been shown in previous studies to have good reliability as well as adequate convergent and discriminant validity (Solberg et al., 1993). In this sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the entire scale was .92, with subscale alphas of .92 for course, .88 for roommate, and .91 for social.

Psychological flexibility/inflexibility with stigmatizing thoughts.

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire Stigma (AAQ-S; Levin et al., 2014) was developed to capture key components of psychological flexibility (e.g. defusion and acceptance) as well psychological inflexibility (e.g. cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance) in the presence of holding stigmatizing thoughts about others. This particular scale was chosen over other versions of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ) because the AAQ-S captures the construct of stigma as it relates to people’s tendency to use group membership to discriminate or evaluate others (Akrami, Ekehammar, & Bergh, 2011; Levin et al., 2014). While the AAQ-S psychological flexibility (PF-S) and inflexibility (PI-S) are often conceptualized as two ends of the same construct, the correlation between subscales is modest (r = .24; Levin et al., 2014) and factor analysis suggests the dimensions are unique (Levin et al., 2014). Additionally, the psychological inflexibility subscale of the AAQ-S has been shown to impact generalized prejudice beyond other relevant variables, whereas the psychological flexibility subscale has not (Levin et al., 2015). This suggests that the two subscales may differentially impact outcomes. PI-S is measured with 11 items and includes statements such as “I stop doing things that are important to me when it involves someone I don’t like” and “The bad things I think about others must be true.” PF-S is measured with 10 items and includes statements such as “I feel that I am aware of my own biases” and “It’s OK to have friends that I have negative thoughts about from time to time” (Levin et al., 2014). Participants completed the twenty-one-item measure and indicated their level of agreement to statements on a 7-point Likert scale, from “1” (never true) to “7” (always true). The AAQ-S has been shown to have adequate construct validity and good reliability (Levin et al., 2014). In this sample the Cronbach’s alphas for the inflexibility and flexibility subscale were both .90.

URM status.

We created a dummy URM status variable in order to analyze whether scores differed as a function of participants’ identified racial/ethnic status. Participants were coded as URM if they indicated any race/ethnicity other than White/Caucasian, if they indicated being multiracial (including White/Caucasian), or if they indicated in the qualitative comments that their racial/ethnic background was multiracial or one other than White/Caucasian. While Asian and Asian-American college students tend to perform at a higher level academically when compared to other racial minority groups (Ying et al., 2001) the common perception of Asian and Asian-American as a “model minority” is laden with cultural assumptions and misinformation (Museus & Kiang, 2009; Suzuki, 2002). Additionally, self-efficacy research suggests Asian and Asian-American students may report less self-efficacy than others in spite of academic performance (Yan & Gaier, 1994). As we were primarily interested in college self-efficacy as an outcome variable, we chose to include Asian/Asian-American students in the URM group.

Results

Preliminary Results

Table 2 provides means and standard deviations for psychological inflexibility, psychological flexibility, and college self-efficacy separated by student minority status. Additionally, we conducted t-tests to test for significant mean differences between racial minority and non-minority students on our variables of interest and calculated Cohen’s d values to provide context to the magnitude of the difference (small effect 0.20 – 0.49; medium 0.50 – 0.79; large 0.80 and above; Cohen, 1988). The only significant difference in means was for reported PF-S: minority students reported significantly less psychological flexibility with stigmatizing thoughts than non-minority students (Table 2). Similarly, Table 3 provides means and standard deviations for PI-S, PF-S, and college self-efficacy by year in school (first, second, third, and fourth). While the mean of college self-efficacy did increase across the four different years in school, a one-way ANOVA revealed that the differences in means across years were not significant; similarly, there were no significant differences in PI-S or PF-s across years. An initial concern was that this may be a result of a lack of power resulting from splitting the sample into four groups, but when years one and two were combined, they did not differ significantly from years three and four.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and t-tests for variables of interest for minority and non-minority students

| Variable | URM students M (SD) |

Non-URM students M (SD) |

t | d | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological inflexibility – stigma | 2.76 (1.08) | 2.59 (.92) | 1.52 | .17 | 336 |

| Psychological flexibility – stigma | 4.68 (1.10) | 5.10 (.96) | 3.62*** | .40 | 336 |

| College self-efficacy | 7.54 (1.84) | 7.79 (1.54) | 1.27 | .15 | 333 |

p<.001

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations for variables of interest separated by year in school

| Variable | First year students M (SD) |

Second year students M (SD) |

Third year students M (SD) |

Fourth year students M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological inflexibility – stigma | 2.65 (.99) | 2.62 (1.04) | 2.64 (.92) | 2.60 (.89) |

| Psychological flexibility – stigma | 5.07 (1.02) | 4.96 (1.01) | 4.82 (1.10) | 5.05 (.97) |

| College self-efficacy | 7.52 (1.74) | 7.69 (1.70) | 7.73 (1.54) | 7.96 (1.59) |

no significant differences between years in school

We next conducted bivariate correlations to ensure that PF-S and PI-S were indeed separate factors and not collinear, as well as to look for significant correlations among our variables of interest (Table 4). PF-S and PI-S were significantly correlated, but the correlation was relatively small (r = −.21), supporting the notion they are unique factors. Similar to the results from the t-tests, minority status was significantly related to PF-S (identifying as a URM student coincided with lower reported psychological flexibility), and year in school was not significantly correlated with other variables. College self-efficacy was significantly related to both PF-S and PI-S in the expected direction; flexibility was positively correlated with self-efficacy and inflexibility was negatively correlated with self-efficacy.

Table 4.

Correlations for Variables of Interest

| URM Status | Year in School | Psych. Flexibility – Stigma | Psych. Inflexibility – Stigma | College Self-Efficacy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| URM Status | -- | ||||

| Year in School | −.00 | -- | |||

| Psych. Flexibility – Stigma | −.18** | −.03 | -- | ||

| Psych. Inflexibility – Stigma | .07 | −.01 | −.21** | -- | |

| College Self-Efficacy | −.06 | .10 | .26** | −.21** | -- |

p <.05

p <.01

Predicting College Self-efficacy

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a hierarchical regression with all direct effects entered in block one and interaction terms in block two (Table 5). The model with only direct effects explained 11% (p <.001) of the variance in college self-efficacy and the interaction terms explained an additional 4% (Δ R2 p < .01).

Table 5.

Summary of regression analysis for variables predicting college self-efficacy

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Psychological inflexibility – stigma | −.31 | .09 | −.18** | −.28 | .09 | −.17** |

| Psychological flexibility – stigma | .39 | .10 | .22*** | .36 | .10 | .21*** |

| Minority status | −.02 | .09 | −.01 | −.02 | .09 | −.01 |

| Year in school | .17 | .09 | .11* | .16 | .09 | .10 |

| Psych. inflexibility – stigma × URM status | −.19 | .09 | −.12* | |||

| Psych. flexibility – stigma × URM status | .10 | .09 | .06 | |||

| Psych. inflexibility – stigma × year in school | .25 | .09 | .15** | |||

| Psych. flexibility – stigma × year in school | .16 | .10 | .09 | |||

| R2 | .11 | .15 | ||||

| F for R2 change | 9.96*** | 3.29* | ||||

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

Direct effects.

As expected there were significant direct associations for both PI-S and PF-S, in that participants who reported greater psychological flexibility reported higher college self-efficacy, and participants who reported greater psychological inflexibility reported lower college self-efficacy (hypothesis 1; table 5). Year in school was also directly associated with college self-efficacy, with self-efficacy increasing with year in school. This result runs counter to the non-significant one-way ANOVA and bivariate correlation, suggesting that while there may not be significant mean differences in college self-efficacy across different years in school, year in school and college self-efficacy are related when PF-S, PI-S, and minority status are held constant. URM status and college self-efficacy were not directly associated; which was consistent with the non-significant bivariate correlation and t-test that compared means of minority and non-minority students’ college self-efficacy.

Psychological inflexibility-stigma.

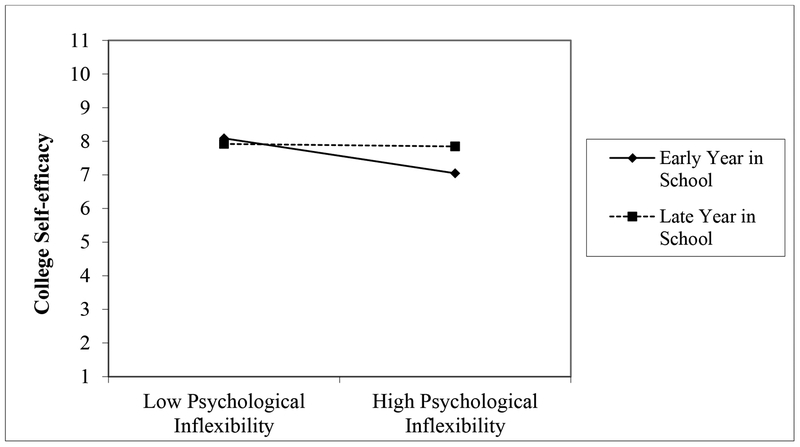

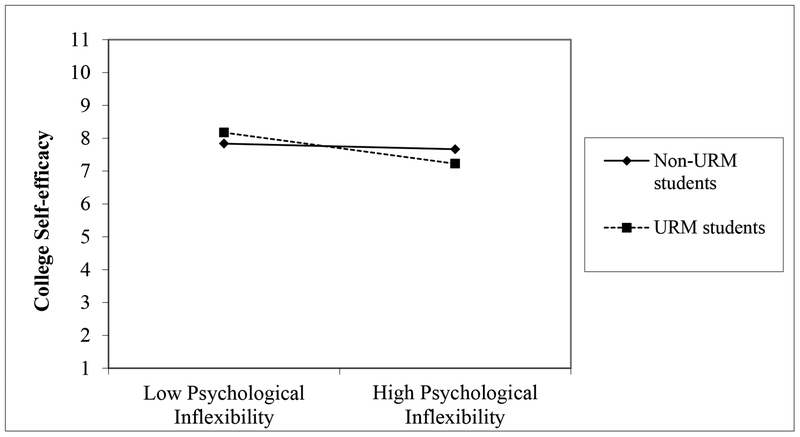

Our second hypothesis was confirmed in that there were significant interactions between year in school and PI-S and URM status and PI-S predicting self-efficacy. Students who had attended school for a shorter time and reported greater PI-S felt significantly less efficacious than psychologically inflexible students who had attended school for longer (see Figure 4). Additionally, URM students who reported greater PI-S felt significantly less efficacious than non-minority, psychologically inflexible students (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Psychological flexibility-stigma.

Contrary to what we predicted in Hypothesis 3, the interactions between PF-S and year in school and PF-S and minority status were not significant in predicting college self-efficacy. This suggests that while PI-S has a differential impact on college self-efficacy depending on the student’s year in school and minority status, PF-S does not.

Discussion

Psychological flexibility and inflexibility are thought to be important constructs for individual performance and wellbeing and stresses the importance of being able to persist in behaviors despite experiencing negative thoughts (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). Consistent with this viewpoint, we found direct effects on college self-efficacy for both psychological flexibility and inflexibility; students who reported greater psychological flexibility with their stigmatizing thoughts felt more efficacious in their ability to complete college-related tasks and students who reported being likely to avoid or withdraw from situations in the face of possessing negative thoughts (psychological inflexibility) reported feeling less efficacious.

It is interesting that the relationship between year in school and college self-efficacy was conditional on only psychological inflexibility and not psychological flexibility. High levels of psychological inflexibility appear to be particularly detrimental for students in their first years of college, but the same is not true for low levels of psychological flexibility. While it is not possible for us to ascertain conclusively why psychological inflexibility seems to affect those early on in their careers differently than more advanced students, there are several possible explanations. Psychologically inflexible students may have difficulty adapting to the college environment. College is often characterized as a time of new challenges particularly for those beginning this transition (Arnett, 2000; Schulenberg et al., 2004). New college students who do not possess the ability to persist toward goals when having negative thoughts, may feel less efficacious in their handling of these new challenges. Students who have been at school longer are likely to have fewer concerns around their efficacy in spite of their psychological inflexibility, simply because they have been able to perform and remain enrolled in college.

It is important to note that the items from the psychological inflexibility subscale ask questions about possessing stigmatizing thoughts and how students respond to the presence of these thoughts. For some students, it is likely that college may be a more diverse environment than they are accustomed to (i.e., interacting with people dissimilar from themselves). If these students hold stigmatizing views of diversity and are unable to manage them, college life could be particularly challenging, but the diverse environment is something they are likely to grow accustomed to the longer they are enrolled which would lead to an increased ability to manage any stigmatizing thoughts.

URM students reported similar levels of self-efficacy and psychological inflexibility compared to non-minority students, but PI-S may manifest differently for minority and non-minority students. URM students who report greater psychological inflexibility reported feeling less efficacious in their ability to accomplish typical college tasks compared to non-minority students. This finding can be potentially explained by evidence that students are likely to face unique challenges as a result of being a member of a minority group. Minority students may feel less comfortable being around others whom they hold stigmatizing thoughts towards and make decisions based on this discomfort (e.g. withdrawing from situations due to concerns for their safety). Consistent with previous studies that have found that individuals encountering stigma report greater psychological inflexibility (Gold et al., 2009; Lillis et al., 2010; Masuda & Latzman, 2011); this finding may be a reflection of internalized stigma among minority students, leading to psychological inflexibility and less self-efficacy.

It is again notable that only the interactions with psychological inflexibility were significant in predicting college self-efficacy. Psychological flexibility and inflexibility are often discussed as different ends of the same construct, but theory and psychometric properties indicate they are unique constructs (Levin et al., 2014). Our results further confirm that these two factors operate differently and suggest separate interpretations for psychological flexibility and inflexibility in the presence of stigmatizing thoughts. In this sample it appears that psychological flexibility served as a promotive factor, or a precursor that decreases the chance of a negative outcome (Stone et al., 2012), for college self-efficacy in that higher reports of psychological flexibility coincided with higher rates of college self-efficacy, regardless of URM status and year in school. Psychological inflexibility served as a risk factor for low levels of self-efficacy and this was particularly true for URM students and those early in their college careers. While there wasn’t a significant difference in college self-efficacy for URM and non-URM students, a wealth of evidence exists to demonstrate that URM students face very different challenges than non-minority students including a difference in resources and encountering stigma and stereotypes (Walton & Spencer, 2009). Our results suggest that the combination of these stressors with high psychologically inflexibility leads to lower levels of college self-efficacy. Similarly, although mean levels of college self-efficacy did not differ significantly by year, prior research has found students starting college feel less efficacious than those who have been in school for at least two years (Zajacova, Lynch, & Espenshade, 2005). Our findings indicate that self-efficacy is particularly volatile for students who are not only beginning college but also have high levels of psychological inflexibility.

In an additional attempt to better understand the discrepancies in results for these subscales, we thought it important to look at the individual subscale items. The PF-S of the AAQ-S contains items that focus on beliefs in an awareness of negative thoughts (e.g. “I feel I am aware of my own biases” and “I am aware when judgments about others are passing through my mind”) and the concept of defusion from Acceptance and Commitment Training (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2011). Defusion is the ability to recognize thoughts as ideas rather than truths (Hayes et al., 2011). An example item from the psychological flexibility subscale focusing on defusion would be “When I evaluate someone negatively, I am able to recognize that this is just a reaction, not an objective fact” (Levin et al., 2014). The PI-S subscale, on the other hand, contains multiple items that are behavior oriented and appear to capture experiential avoidance, which is similar to withdrawing from a behavior in the presence of negative thoughts (Hayes et al., 2011). Examples of these items are “When I am having negative thoughts about others, I withdraw from people” and “I stop doing things that are important to me when it involves someone I don’t like” (Levin et al., 2014). The CSE also contains multiple behavior-oriented items. It may be that behavior items from the PI-S are driving the significant interactions with minority students and year in college. As a way to explore this, we combined all items from the PI-S and PF-S that focused on awareness of thoughts or defusion. We then combined the six behavior and experiential avoidance items from PI-S (Table 6). Subsequent regressions revealed a significant interaction with year in school (β = .12) and minority status (β = −.17) for the behavior/experiential avoidance items of the AAQ-S when predicting self-efficacy, but not for the awareness of thought/defusion items. If these behavior/experiential avoidance items are driving the psychological inflexibility interaction, then this relationship may indicate that the self-efficacy of minority students and those early in their college career are impacted by their ability to persist in their actions when holding negative thoughts and being merely aware of negative thoughts is less relevant to self-efficacy. While this post hoc analysis is speculative, there are important accompanying implications, as these findings would suggest that withdrawing from situations is particularly detrimental for individuals just starting college and URM students. Additionally, the idea that confidence in carrying out behaviors is different for self-efficacy than awareness of negative thoughts has face validity, particularly when you consider that the measure of college self-efficacy contains items relevant to college behaviors. The CSE consists of items about belief in ability to perform specific college-related tasks, many of which may be viewed as challenging, particularly at the beginning of college and for those likely to encounter stereotype threat (e.g. URM students). It follows that if students feel competent in carrying out important behaviors when challenged with uncomfortable or negative thoughts, they are likely to feel competent when faced with other challenges as well, including the challenges associated with college attendance. These subsequent analyses ultimately indicate that behavioral indicators of psychological inflexibility differentially impact URM students and students early in their college careers, but the impact of beliefs on self-efficacy is consistent throughout years in college and for both URM and non-URM students.

Table 6.

Items from the AAQ-S – items related to behaviors/experiential avoidance are highlighted

| Psychological Inflexibility | Psychological Flexibility |

|---|---|

| My biases and prejudices affect how I interact with people from different backgrounds. | I feel that I am aware of my own biases. |

| I need to reduce my negative thoughts about others in order to have good social interactions. | My negative thoughts about others are never a problem in my life. |

| I stop doing things that are important to me when it involves someone I don’t like. | I rarely worry about getting my evaluations towards others under control. |

| I have trouble letting go of my judgments of others. | I’m good at noticing when I have a judgment of another person. |

| I feel that my prejudicial thoughts are a significant barrier to me being culturally sensitive. | When I evaluate someone negatively, I am able to recognize that this is just a reaction, not an objective fact. |

| I have trouble not acting on my negative thoughts about others. | I am aware when judgments about others are passing through my mind. |

| When I am having negative thoughts about others, I withdraw from people. | It’s OK to have friends that I have negative thoughts about from time to time. |

| When I have judgments about others, they are very intense. | I don’t struggle with controlling my evaluations about others. |

| When talking with someone I believe I should act according to how I feel about him/her, even if it’s negative. | When I’m talking with someone I don’t like, I’m aware of my evaluations of them. |

| I often get caught up in my evaluations of what others are doing wrong. | I accept that I will sometimes have unpleasant thoughts about other people. |

| The bad things I think about others must be true. |

Implications

Findings from this study can be used to inform future college student programming efforts. Incoming students may benefit from programs that encourage cultural awareness and acceptance and celebrate diversity, as those who reported greater psychological inflexibility reported feeling less efficacious in carrying out college-related tasks. Additionally, specific ACT-based training to help students manage psychological inflexibility and encourage persistence in behavior is likely to positively impact college students’ levels of self-efficacy, and ultimately their academic performance.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study is not without limitations. The data are cross-sectional, which limits the conclusions we can draw on the possible causal impact of psychological inflexibility/flexibility with stigmatizing thoughts on college self-efficacy and college performance. Assessing changes and stability in these constructs over time may shed more light on the ways in which psychological inflexibility can impact college students. This is particularly true during the college years, as emerging adulthood is often a time of shifting and crystallizing values and identities (Arnett, 2000). All racial-ethnic minority groups were collapsed into a single URM status variable, which prevented any analysis of effects between different groups. Any assumptions or generalizations based on moderation by URM status should be made with caution as further research is needed.

Because the survey used in this study was anonymous, we were unable to link participant responses to direct measures of academic performance (e.g. student GPAs and retention). While college self-efficacy is closely related to academic performance (Brady-Amoon & Fuertes, 2011; Chemers, Hu, & Garcia, 2001), measuring student grades and retention would help clarify the extent to which psychologically inflexible college students are able to persist in their college years or, alternatively, experience academic failure and/or drop out of school. This would strengthen the argument that psychological flexibility and inflexibility are important constructs for college students and is an important next step for future studies. The 9% response rate is neither atypical for an online college survey (Shih & Fan, 2008) nor ideal, as it introduces the possibility of selection effects. For example, students who completed the survey may have been more motivated, more efficacious, and more psychologically flexible than the students who did not. Despite this potential limitation, there was still substantial variability in our variables of interest. Additionally, the sample was diverse in terms of race and ethnicity and participants had varying years of college experience. If our sample was indeed higher on self-efficacy and motivation than would be expected in the general college population, it does not necessarily mean that the connection between self-efficacy and psychological flexibility/inflexibility would no longer hold with a more representative group. In fact, it may be the case that the results reported here are conservative and would be more robust with greater variability in college self-efficacy.

In addition to evaluating psychological flexibility/inflexibility with stigmatizing thoughts over time and assessing how these variables impact different academic variables as well as different minority groups, future research is needed to fully parse out the differences in the AAQ-S subscale. Levin and colleagues (2014) did find psychometric evidence that these are indeed separate constructs, and our interaction findings further reinforce this; however, future studies should examine if these two constructs differentially impact other outcomes. Similarly, the separation of awareness of thoughts/fusion items from behavior/experiential avoidance items is not something that has been investigated to our knowledge. Future investigation into what domains of psychological flexibility/inflexibility exist and their implications could benefit psychological flexibility, and have potential implications for college program designed to help students with negative thoughts.

Conclusion

The work presented here highlights how psychological flexibility and inflexibility with stigmatizing thoughts can impact individual college self-efficacy; a meaningful construct that predicts college success. We believe our results shed light on possible ways for universities to improve college students’ self-efficacy and ultimately academic performance through programming that focuses on persistence in the face of challenges and encourages cultural awareness and acceptance. Specifically our findings further emphasize the utility of brief social-psychological interventions as mechanisms to improve academic performance. These interventions (e.g. growth mindset, values affirmation) have been shown to lead to better academic performance not by providing students with additional educational skills, but rather through targeting students’ individual thoughts and feelings around belonging in a college environment and buffering against stereotypes and stigma that students experience (see Yeager & Walton, 2011 for review). Finally, our work suggests that psychological flexibility and inflexibility are indeed different constructs and have different implications for college students.

References

- Akrami N, Ekehammar B, & Bergh R (2011). Generalized prejudice: Common and specific components. Psychological Science, 22(1), 57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, & Inzlicht M (2004). The ups and downs of attributional ambiguity: Stereotype vulnerability and the academic self-knowledge of African American college students. Psychological Science, 15(12), 829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali VA, & Alvarez RM (2003). Schools and educational outcomes: What causes the “race gap” in student test scores?. Social Science Quarterly, 84(3), 485–507. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, & Bilgel N (2008). The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(8), 667–672. 10.1007/s00127-008-0345-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WG, Kurzweil MA, Tobin EM, & Pichler SC (2006). Equity and excellence in American higher education. Univ of Virginia Pr. [Google Scholar]

- Brady-Amoon P, & Fuertes JN (2011). Self-Efficacy, Self-Rated Abilities, Adjustment, and Academic Performance. Journal of Counseling and Development, 89(4), 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Brissette I, Scheier MF, & Carver CS (2002). The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP, & Lee MN (2005). Stigma consciousness and the race gap in college academic achievement. Self and Identity, 4(2), 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Burnette JL, Pollack JM, & Hoyt CL (2010). Individual differences in implicit theories of leadership ability and self-efficacy: Predicting responses to stereotype threat. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(4), 46–56. 10.1002/jls.20138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemers MM, Hu L, & Garcia BF (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hilsdale. NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Kirsch AC, Dickson DA, & Bryant FB (2014). Negotiating the Transition to College: Developmental Trajectories and Gender Differences in Psychological Functioning, Cognitive-Affective Strategies, and Social Wellbeing. Emerging Adulthood, 2(3), 195–210. 10.1177/2167696814521808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SD, Dickstein BD, Marx BP, & Lexington JM (2009). Psychological Outcomes Among Lesbian Sexual Assault Survivors: An Examination of the Roles of Internalized Homophobia and Experiential Avoidance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(1), 54–66. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01474.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, & Lillis J (2006). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, & Wilson KG (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Barrios V, Forsyth JP, & Steger MF (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1301–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, & Rottenberg J (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh GD, Cruce TM, Shoup R, Kinzie J, & Gonyea RM (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. The journal of higher education, 79(5), 540–563. [Google Scholar]

- Levin ME, Lillis J, Luoma JB, Hayes SC, & Vilardaga R (2014). The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire- Stigma: Developing a measure of psychological flexibility with stigmatized thoughts. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ME, Luoma JB, Vilardaga R, Lillis J, Nobles R, & Hayes SC (2015). Examining the role of psychological inflexibility, perspective taking, and empathic concern in generalized prejudice. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillis J, Luoma JB, Levin ME, & Hayes SC (2010). Measuring Weight Self-stigma: The Weight Self-stigma Questionnaire. Obesity, 18(5), 971–976. 10.1038/oby.2009.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, & Latzman RD (2011). Examining associations among factor-analytically derived components of mental health stigma, distress, and psychological flexibility. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(4), 435–438. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Museus SD, & Kiang PN (2009). Deconstructing the model minority myth and how it contributes to the invisible minority reality in higher education research. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2009(142), 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2015, May). The Condition of Education - Postsecondary Education Indicator May (2015). Retrieved October 20, 2015, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cva.asp [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella ET, Pierson CT, Wolniak GC, & Terenzini PT (2004). First-generation college students: Additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. Journal of Higher Education, 249–284. [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, & Heuer CA (2009). The Stigma of Obesity: A Review and Update. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rankin SR (2005). Campus climates for sexual minorities. New Directions for Student Services, 2005(111), 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, & Corrigan PW (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Sameroff AJ, & Cicchetti D (2004). The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sher KJ, Wood PK, & Gotham HJ (1996). The course of psychological distress in college: A prospective high-risk study. Journal of College Student Development. [Google Scholar]

- Shih TH, & Fan X (2008). Comparing response rates from web and mail surveys: A meta-analysis. Field Methods, 20(3), 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg VS, O’Brien K, Villareal P, Kennel R, & Davis B (1993). Self-efficacy and Hispanic college students: Validation of the college self-efficacy instrument. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Steele CM, & Quinn DM (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, & Aronson J (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Spencer SJ, & Aronson J (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In Zanna Mark P. (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379–440). New York: Academic Press. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065260102800090 [Google Scholar]

- Steele‐Johnson D, & Leas K (2013). Importance of race, gender, and personality in predicting academic performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,43(8), 1736–1744. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens NM, Fryberg SA, Markus HR, Johnson CS, & Covarrubias R (2012). Unseen disadvantage: how American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens NM, Hamedani MG, & Destin M (2014). Closing the social-class achievement gap: A difference-education intervention improves first-generation students’ academic performance and all students’ college transition. Psychological Science, 25(4), 943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, & Catalano RF (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7), 747–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki BH (2002). Revisiting the model minority stereotype: Implications for student affairs practice and higher education. New Directions for Student Services, 2002(97), 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Torres J, & Solberg V (2001). Role of self-efficacy, stress, social integration, and family support in Latino college student persistence and health. Journal Of Vocational Behavior, 59(1), 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Towbes L, & Cohen L (1996). Chronic stress in the lives of college students: Scale development and prospective prediction of distress. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(2), 199–217. 10.1007/BF01537344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, & Spencer SJ (2009). Latent ability: Grades and test scores systematically underestimate the intellectual ability of negatively stereotyped students. Psychological Science, 20(9), 1132–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, & Mohammed S (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 20–47. 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SL, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, & Murdock JL (2013). Career Development Among First-Year College Students College Self-Efficacy, Student Persistence, and Academic Success. Journal of Career Development, 40(4), 292–310. 10.1177/0894845312455509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, & Gaier EL (1994). Causal attributions for college success and failure: An Asian-American comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 25(1), 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, & Walton GM (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 267–301. [Google Scholar]

- Ying YW, Lee PA, Tsai JL, Hung Y, Lin M, & Wan CT (2001). Asian American college students as model minorities: An examination of their overall competence. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7(1), 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajacova A, Lynch SM, & Espenshade TJ (2005). Self-efficacy, stress, and academic success in college. Research in Higher Education, 46(6), 677–706. [Google Scholar]