Abstract

Introduction:

As most adults with spina bifida are either sexually active or interested in becoming sexually active, providers should understand how spina bifida impacts sexual function and options for treatment.

Objectives:

To summarize the current literature describing how features of spina bifida impact sexual function in men and women, effective available treatment options for sexual dysfunction, and to identify research gaps.

Methods:

Searches were conducted in PubMed, CINAHL Complete, PsychInfo, Cochrane Central, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection Databases using keywords related to spina bifida and sexual function. Thirty-four primary research studies were included.

Results:

Most men (56-96%) can achieve an erection, although it may be insufficient for penetration. While 50-88% ejaculate, it is often dripping, retrograde, or insensate. Twenty to 67% achieve orgasm. Generally, men with lower lesions and intact sacral reflexes have better outcomes, although some men with all levels of lesion report good function. Sildenafil is efficacious at treating erectile dysfunction for most men. The TOMAX procedure may improve sexual function in select men with low level lesions. Female sexual function and treatment is less well understood. Women may experience decreased arousal, difficulties with orgasm, and pain. No treatment has been studied in women. Bowel and bladder incontinence during intercourse appears to be bothersome to men and women. While both men and women have diminished sexual satisfaction, their sexual desire appears to be least impacted. Current studies are limited by studies’ small, heterogeneous populations, the misuse of validated questionnaires in the sexually inactive, and the lack of a validated questionnaire specific to people with spina bifida.

Conclusions:

Spina bifida impacts the sexual function of both men and women. Future studies should seek a better understanding female sexual function and treatment, utilize validated questionnaires appropriately, and ultimately, create a validated sexual function questionnaire specific to this population.

Keywords: Spina bifida, sexual function, orgasm, ejaculation, lubrication, erectile dysfunction

Introduction

Spina bifida is the most common permanently disabling birth defect caused by abnormal development or closure of the spinal cord.1 While survival for infants born with spina bifida was once poor, with improvements in medical and surgical care, the life expectancy for people living with spina bifida (SB) has improved such that there are now more adults living with SB than children.2 As a result, there has been an increasing interest in understanding their adult concerns. Studies have shown that over half of adult men and women with SB are sexually active,3 and that most who are not sexually active are nonetheless interested.4 This has led to a recent focus on better understanding the sexual function of people with SB.

There are several features of SB that have the potential to impact sexual function. First, the hallmark of SB is a neural tube lesion. To understand how the lesion can impact function, it is important to consider both the level of the defect, referred to as the level of lesion, and the type of lesion. Importantly, the level of lesion does not always correspond with the level of function, with people with SB of the same level of lesion having variable motor and sensory function. Additionally, there are several types of lesions, with those with less severe forms often, but not always, experiencing less disability. Myelomeningocele is the most severe form, occurring when the spinal cord is exposed outside of the skin through an opening in the spine. Meningocele describes a lesion where spinal fluid and meninges, but no neural elements, are exposed. Closed neural tube defects are malformations of the fat, bone, or meninges of the spinal cord. SB occulta is the mildest form in which there are only vertebral abnormalities. SB, in particular myelomeningocele, can be associated with Arnold-Chiari type II malformations which cause hydrocephalus, with some requiring a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) or other shunt.1 People with SB have variable physical disability, ranging from the ability to ambulate without assistance to requiring a wheelchair. There is also a wide range of bladder involvement. Many require intermittent catheterization and occasionally bladder reconstructive surgeries to achieve continence or prevent deterioration of the kidneys, but some are able to volitionally void and remain continent. Some people with SB also have pelvic instability, severe scoliosis, contractures, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse, which also have the potential to impact sexual function.

The neurologic involvement of spina bifida may impact the typical sexual response in several ways. The ability to achieve and maintain an adequate erection and experience forceful ejaculation for men, achieve vaginal lubrication for women, and attain an orgasm for both men and women requires complex integration of the central and peripheral nervous system. A typical erection is pre-empted by the central nervous system processing visual, auditory, and physical sensory inputs. Peripheral nervous system involvement includes parasympathetic input to stimulate an erection, somatic input for penile sensation and the rigid-erection phase and the ejection phase of ejaculation, and sympathetic input for ejaculation and penile detumescence. The somatic and parasympathetic nerve roots arise from the second, third, and fourth sacral spinal cord segments, whereas the sympathetic nerve roots are located at the 11th thoracic to the 2nd lumbar spinal cord segments.5 Men with lesions above the 11th thoracic spinal cord segment should maintain reflexogenic erections in response to touch, but not psychogenic erections in response to visual, auditory, or other non-genital tactile sensations.6,7 Men with lesions between the 11th thoracic spinal cord segment and above the sacral erectile pathway should maintain both reflexogenic and psychogenic erections.6,7 Patients with lesions at the conus terminalis should have psychogenic erections, but not reflexogenic erections.6 Men with lesions below this, in theory, should not experience psychogenic or reflexogenic erections,6 although some studies have nonetheless demonstrated preserved psychogenic erections in these men.7-10 Reflexogenic erections are typically short in duration and require continuous stimulation to maintain, whereas psychogenic erections may not be rigid enough for intercourse. For women, sexual excitement activates the hypothalamic centers and limbic-hippocampal system, resulting in impulses through the pelvic nerves that lead to vaginal lubrication, labial enlargement, and erection of the clitoral glans.11 Tactile genital stimulation is delivered through the pudendal nerve to the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves, which can lead to bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus spasms and the sensation of orgasm. Female orgasm is thought to occur rarely in patients with lesions above L2.12 The impact of hydrocephalus on the central nervous system input for male and female sexual function is less well understood.

Since Diamond’s landmark study on male erectile function in 1986,13 there have been an increasing number of studies that have sought to examine sexual function, satisfaction, and treatment of men with SB, as well as factors, such as level of lesion or hydrocephalus status, that influence function. While studies of female sexual function and treatment have lagged behind, there has also been a recent increase in research in this area. In this context, we sought to perform a scoping review to describe the sexual function and treatment of males and females with SB, as well as to identify gaps in the current research that can inform and direct future studies.

Materials and Methods

A scoping review methodology was chosen for this review because of this methodology’s focus on understanding the “extent, range, and nature of research activity” on a topic.14 The main focus was to identify and understand the sexual function and treatment of males and females living with SB. The broader psychosocial domains of sexuality, such as experiences receiving sex education or the experiences in relationships sexual partners (e.g., whether the diagnosis of SB was disclosed or experiences with abuse), were not included.

With the assistance of a medical librarian (JS), searches were conducted in six databases: PubMed; CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost; EBSCO, Ipswich, MA); PsycInfo (EBSCOhost; EBSCO, Ipswich, MA); Cochrane Central (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ); Scopus (Elsevier, New York, NY); Web of Science Core Collection Databases (Clarivate Analytics; Philadelphia, PA). The initial search, run on 28 July 2019, focused on general sexual function in people with SB and issues specifically related to women. Searches were rerun on 1 May 2020 to look for any recent updates and to also add male sexual function terminology. Reproductive health terminology was included to ensure no studies on both sexual and reproductive health were missed. Search dates included 1994 to date of search, and no language filters were applied. The year 1994 was chosen as a starting to be inclusive of the most recent studies in the last 25 years. However, one landmark manuscript was included due to its relevance in informing more recent studies.13 The primary search was conducted in PubMed, and combined controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) with keywords in the title, abstract, and author supplied keywords. Sample keywords included: sexual*, coitus*, reproduction, combined with “SB.” Examples of MeSH terms included “Spinal dysraphism;” “Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological,” and “Sexual Dysfunctions, Psychological.” Searches in the additional databases were translations of the primary PubMed Search. Complete search strategies are available in Appendix A.

Qualitative studies, quantitative studies, primary research studies, meta-analyses, and research letters written in English were included. Manuscripts were excluded if they were a systematic review, book chapter or excerpt, case reports of fewer than 4 people, not written in the English language, or if they were an abstract or meeting presentation with no associated manuscript. Manuscripts that addressed sexual health of a broader population (e.g., people with physical disabilities) without specifying the results of the SB subpopulation were also excluded.

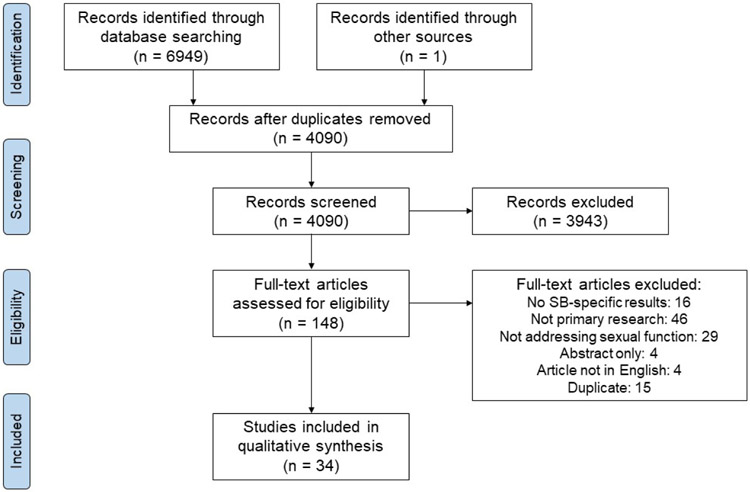

The search resulted in 6949 titles. Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all 4,090 de-duplicated search results (CS and ML). After consensus was met, 148 manuscripts were reviewed, and 34 met criteria for inclusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram of literature review.

Results

Researchers used several different validated questionnaires (Table 1), as well as their own questionnaires, to assess sexual function. In the summary tables, possible score ranges, or Theoretic Rank (TR), and Normative Values (NV) based on validation trials,15-18 when available, are listed. The results are organized as an overview of male sexual function, treatment of male sexual dysfunction, female sexual function, treatment of female sexual dysfunction, and an overview of male and female sexual satisfaction. The overview of male and female sexual function is organized by the domains of the most commonly used validated surveys, the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) for men and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) for women.

Table 1.

Overview of validated Questionnaires commonly used for evaluating sexual function in men and women with spina bifida.

| Questionnaire | Intended Use | Domains |

|---|---|---|

| International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)19 | Sexually active men without an uncontrolled major medical illness or psychologic disorder, penile anatomic defect, or drug or alcohol dependence | Erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, overall satisfaction |

| Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM)18 | Men in a stable relationship with a female partner without penile anatomic defects, major medical illnesses, major psychiatric disorders, or a history of drug or alcohol abuse | Erectile function and intercourse satisfaction |

| Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)20 | Sexually active women, pre- and post-menopausal, heterosexual | Desire and subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain/discomfort |

| Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISF-W)17 | Sexually active healthy women and those with medical and psychological conditions, heterosexual and homosexual | Sexual interest/desire, sexual activity, satisfaction |

| Watts Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (WSFQ)21 | Sexually active men and women with a chronic disease, heterosexual and homosexual | Sexual desire, orgasm, arousal, satisfaction |

Male Sexual Function

We identified nineteen studies, including one older study included for historic reference,13 that reported on the sexual function of men with SB (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of studies on male sexual function.

| Study | Population | Sexual activity |

How sexual function was assessed |

Desire/Arousal | Erectile Function | Ejaculatory/Orgas mic Function |

Satisfaction | Overall Satisfaction / Composite Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bomalaski22 | SB aperta: 16 males >18 yrs | 3/16 (13%) sexually active | Own questionnaire | 9/16 (56%) reported “normal” erections | ||||

| Cardenas3 |

SB*: 52 males ≥15 yrs HC status: 25/52 (48%) HC+ 27/52 (52%) HC− |

30/52 (57.7%) sexually active; 13/27 (48%) HC+ and 17/25 (68%) HC− | Perceived Quality of Life Scale (PQOL) | “Satisfaction with level of sexual activity”: HC−: 5.77 (±3.24), HC+: 4.28 (±3.34) | ||||

| Choi23 |

MMC or LMC: 47 males (mean age 25.2 yrs, range 20-39) SB type: 13/47 (28%) MMC, 34/47 (72%) LMC LOL: 22/47 (47%) lumbar, 11/47 (23%) sacral, 14/47 (30%) unknown |

24/47 (51%) sexually active in last month | IIEF in SA and SI |

SA: mean 6.33 (± 1.54) (TR 2-10) SI: mean 5.30 (±1.77) (p=0.05) Dysfunction in SA: 1/24 (4%)- none 10/24 (41%)- mild 9/24 (38%)- mild to moderate 4/24 (17%)- moderate 0/24 (0%)- severe |

SA: mean 23.58 (±6.91) (TR 1-30, NV >25) SI: mean 6.78 (±3.57) (p<0.001) Dysfunction in SA: 16/24 (67%)- none 4/24 (17%)- mild 1/24 (4%)- mild to moderate 2/24 (8%)- moderate 1/24 (4%)- severe |

ORGASMIC FUNCTION SA: mean 7.83 (±2.18) (TR 0-10) SI: mean 4.30 (±3.20) (p=0.001) Dysfunction in SA: 12/24 (50%)- none 7/24 (30%)- mild 2/24 (8%)- mild to moderate 2/24 (8%)- moderate 1/24 (4%)- severe |

INTERCOURSE SATISFACTION SA: mean 8.36 (±2.26) (TR 0-15) SI: mean 0.26 (±1.25) (p<0.001) Dysfunction in SA: 0/24 (0%)- none 8/24 (33%)- mild 12/24 (50%)- mild to moderate 3/24 (13%)- moderate 1/24 (4%)- severe |

OVERALL SATISFACTION SA: mean 6.21 (±2.00) (TR 2-10) SI: mean 4.35 (±1.30) (p=0.001) Dysfunction in SA: 3/24 (13%)- none 8/24 (33%)- mild 7/24 (29%)- mild to moderate 5/24 (21%)- moderate 1/24 (4%)- severe |

| Decter24 |

SB*: 57 males >18 yrs (median 28.6, range 18-55) LOL: 12/57 thoracic, 3/57 (5%) L1-L2, 13/57 (23%) L3, 11/57 (19%) L4, 8/57 (14%) L5, 10/57 (17.5%) sacral VP shunt status: 33/57 (57%) shunted 24/57 (42%) unshunted |

22/57 (39%) masturbated or attempted sexual intercourse | Own questionnaire | 41/57 (72%) achieved erections, more consistently with lower LOL and absence of a VP shunt Achieved erections by LOL: 6/12 (50%) thoracic, 3/3 (100%) L1-2, 7/11 (64%) L4, 6/8 (75%) L5, 10/10 (100%) sacral Achieved erections by shunt status: 20/33 (61%) shunted, 21/24 (87.5%) not shunted |

30/57 (53%) ejaculated, including 3/57 (5%) without an erection; 24/30 (85%) found ejaculation pleasurable Ability to ejaculate by LOL: 1/12 (17%) thoracic, 2/3 (67%) L1-L2, 5/13 (38%) L3, 6/11 (55%) L4, 6/8 (75%) L5, 10/10 (100%) sacral Ability to ejaculate by shunt status: 10/33 (30%) shunted, 21/24 (88%) not shunted |

|||

| Diamond13 |

MMC: 52 males ages 12-28 yrs (mean 16.8) LOL: 20/52 (38%) at or above T10 (level of sympathetic outflow) 32/52 (62%) below T10 Anocutaneous reflex status: 27/52 (52%) present 25/52 (48%) absent |

Unknown | Men and parents questioned | 36/52 (70%) had erections Achieved erections by LOL and reflexes: 21/21 (100%) of men with an intact anocutaneous reflex and LOL above T10 had erections; 7/11 (64%) with a negative anocutaneous reflex and LOL at or below T10, 2/14 (14%) with a negative anocutaneous reflex and LOL above T10 |

||||

| Gamé25 | MMC: 40 men >18 yrs (mean 29) | 16/40 (40%) had sexual intercourse in the last month, those sexually active tended to be older (mean 32 yrs vs 28) | IIEF in SA | 6.94 (±2.4) (TR2-10) | Mean: 11.61 (±9.44) (TR 1-30, NV >25) Erectile Dysfunction: 4/16 (25%)- none 3/16 (19%)- mild 4/16 (25%)- mild to moderate 5/16 (31%)- severe ED significantly more likely if sacral nerve root impairment present −10/12 (83%) with sacral nerve root involvement vs 0/4 (0%) without (p=0.017) |

ORGASMIC FUNCTION: Mean 3.52 (±3.86) (TR 0-10) | INTERCOURSE SATISFACTION: 3.7 (±4.81) (TR 0-15) | OVERALL SATISFACTION: Mean 4.7 (±3.34) (TR 2-10) |

| Gatti26 |

SB aperta and occulta: 125 males ≥18 yrs LOL: 23/125 (19%) L2 or above, 47/125 (39%) L3-L5, 50/125 (42%) sacral |

Sexual Contact: 3/23 (14%) L2 or above, 7/47 (14%) L3-L5, 15/50 (30%) sacral (p<0.05) | Own questionnaire | -3 men used sildenafil with subjective improvement -10 used vacuum constriction devices or intracavernous injection of vasoactive agents |

||||

| Lassmann17 | SB*: 42 men ≥18 yrs | 9/42 (21%) sexually active | WSFQ in SA |

DESIRE: Mean: 22 (±3) (max score 30) AROUSAL: Mean: 13.8 (±3.5) (max score 20) |

ORGASM: Mean: 14.8 (±3.5) | INTERCOURSE SATISFACTION: Mean: 13.3 (±1.3) (max score 15) | OVERALL SATISFACTION: Mean: 63.9 (±8.9) (TR 18-85) | |

| Lee27 | SB*: 17 males ≥18 yrs | Unknown | SHIM and IIEF in SA and SI combined | Median 5.0 (IQR 2.0-8.0) |

SHIM: Median 5 (IQR 1.0-12.0) (TR 1-25, NV >21) -Better function in lower LOL (p=0.02) but no association with ambulatory status (p=0.15) Erectile Dysfunction: 1/17 (6%)- none 1/17 (6%)- mild ED 3/17 (18%)- mild to moderate 2/17 (12%)- moderate 10/17 (59%)- severe |

ORGASM: Median 1.0 (IQR 0.0-5.0) (TR 0-10) | INTERCOURSE SATISFACTION: Median 3.0 (IQR 2.0-4.0) (TR 0-15) | OVERALL SATISFACTION: Median 3.0 (IQR 2.0-4.0) TR 2-10) |

| Lindehall28 | SB*: 7 males on CIC | Unknown | Qualitative Interviews | 6/7 (86%) able to achieve an erection and/or ejaculate | 6/7 (86%) able to achieve an erection and/or ejaculate | |||

| McCloskey29 | MMC: 24 males (also included other males with other GU anomalies) from a single institution | Unknown | SHIM | SHIM completed for 8 men with SB. Median SHIM was 16.5 (range 10-23) | ||||

| Roth30 | SB*: 122 males ages 18 yrs and older, median age 33 (Interquartile Range 27-41 yrs) | Unknown | Own questionnaire | In last 4 weeks, erections described as: 22/122 (18%)- none 27/122 (22%) not firm enough for sexual activity 23/122 (19%) firm enough for masturbation or foreplay only 50/122 (41%) firm enough for intercourse Ambulators (household, community, or normal) significantly more likely to have no ED than non-ambulators. Age, VP shunt, and history of bladder neck surgery not predictive of ED. |

||||

| Sandler31 |

SB*: 15 males, mean age 20 yrs (range 16-29) from 2 academic centers LOL: 3/15 (20%) thoracic, 3/15 (20%) mid-high lumbar, 7/15 (47%) low lumbar, 2/15 (13%) sacral |

4/15 (26.7%) | Rigi-Scan recordings, physical exam, structured interviews, own questionnaire | All interested in sex |

STIMULATED ERECTIONS: 11/15 (73.3%) able to stimulate erections -more common in those with lower LOL (p<0.01) and glans sensation (p<0.05) RIGI-SCAN OUTCOMES: 2/15 (13%)- normal 7/15 (46.7%)- intermediate 6/15 (40%)- flat/no nocturnal erections -related to sensory LOL (p<0.05), not ability to stimulate an erection |

11/15 (73.3%) able to ejaculate: −2/15 (13%) ejaculated without erections −3/15 (20%) had “good sexual feelings” with ejaculation -most described ejaculation as “dribbling,” -4/15 (27%) had ejaculate in their urine (retrograde ejaculation) |

||

| Sawyer and Roberts4 | MC and MMC: 24 adolescents and young adults from a single institution | -13/24 (54%) kissed someone in a sexual way -5/24 (21%) had “further sexual activity” -3/24 (13%) had intercourse |

Own questionnaire | 19/24 (79%) “has had sexual fantasies” | 21/24 (88%) able to achieve erection | 16/24 (67%) able to ejaculate 14/24 (58%) orgasm | ||

| Shiomi32 |

SB*: 26 males Sharrard Classification: 3/26 (11.5%) Sharrard 1, 5/26 (19%) Sharrard 2, 3/26 (11.5%) Sharrard 3, 2/26 (8%) Sharrard 4, 7/26 (27%) Sharrard 5, 6/26 (23%) Sharrard 6 Genital sensation: 19/26 (73%) with 7/26 (27%) without |

11/26 (42%) had intercourse | Own questionnaire and IIEF | 22/26 (88%) had psychogenic erections by audio-visual stimulation -significant difference based on Sharrard classification [1/3 (33%) Sharrard 1 vs. 21/23 (91%) above Sharrard 2, p<0.05], but not touch sensation [17/19 (89%) with touch sensation vs 5/7 (71%) without] 14/26 (54%) had erections by tactile stimulation -significant difference based on touch sensation [13/19 (68%) with touch sensation vs. 1/7 (14%) without, p<0.05] but not Sharrard classification [10/20 (50%) under Sharrard 5 vs. 5/6 (83%) Sharrard 6] IIEF in SA: ED did not correlate with Sharrard classification or touch sensation -ED in 5/9 (55.5%) with touch sensation vs. 1/2 (50%) without -ED in 3/8 (37.5%) who achieved erections by tactile stimulation, 3/3 (100%) who did not |

23/24 (95.8%) ejaculated, with a significant difference based on Sharrard classification (1/3 (33%) Sharrard 1 vs. 22/23 (96%) above Sharrard 2, p<0.05) but not touch sensation (positive versus negative, 18/19 (94%) vs 5/7 (71%)) 17/24 (65%) orgasmed, with a significant difference based on touch sensation (positive vs. negative, 16/19 (84%) vs. 1/7 (14%), p<0.05) but not Sharrard classification (5/6 (83%) Sharrard 6 versus 12/20 (60%) under Sharrard 5) | |||

| Verhoef33 | SB aperta or occulta: 74 males 16-25 yrs | Sexual activity defined as French kissing or more; 71/119 (60%) of SB aperta HC+, 21/23 (93%) of SB aperta HC−, and 37/37 (100%) of SB occulta sexually active; 36/78 (46%) of men with high LOL, 54/63 (86%) with mid LOL, and 36/38 (94%) with low LOL sexually active | Structured interview and physical exam |

SB Type: ED reported in 8/28 (28.5%) with SB aperta HC+, 1/13 (7.7%) of SB aperta HC−, and 0/12 (0%) of SB occulta -difference not significant LOL: ED reported in 5/13 (48%) with high LOL, 4/25 (16%) with mid LOL, 0/15 (0%) with low LOL -significant difference (p<0.05) |

EJACULATION: SB Type: Problems with ejaculation in 11/28 (39%) with SB aperta HC+, 2/13 (15%) with SB aperta HC−, 0/12 (0%) with SB occulta -significant difference (p<0.05) LOL: Problems with erection in 7/13 (54%) with high LOL, 6/25 (24%) with mid LOL, and 0/15 (0%) with low LOL -significant difference (p<0.01) ORGASM: SB type: 12/28 (43%) with SB aperta HC+, 1/13 (7.7%) SB aperta HC−, 0/12 (0%) with SB occulta -significant difference (p<0.01) LOL: Problems with orgasm in 7/13 (54%) with high LOL, 5/25 (20%) with mid LOL, 1/15 (6.7%) with low LOL -significant difference (p<0.05) |

|||

| Verhoef34 | SB aperta or occulta: 64 males 16-25 yrs | Sexual intercourse: 13/22 (59%) HC− and 3/42 (7%) HC+ | Structured interview and physical exam | “Desire for sexual contact”: 21/22 (96%) HC− and 25/42 (60%) HC+ (p<0.05) | “Experiencing only sometimes or never, during masturbation or sexual contact”: Erection 1/22 (5%) HC− and 7/25 (28%) HC+ -difference not significant | “Experiencing only sometimes or never, during masturbation or sexual contact”: EJACULATION: 2/22 (9%) HC− and 10/25 (40%) HC+ (p<0.05) -difference not significant ORGASM: 1/22 (5%) HC− and 11/25 (44%) HC+ (p<0.05) -difference not significant |

“Satisfied with present sex life”: 14/22 (68%) HC− and 18/42 (43%) HC+ (p<0.05) | |

| Von Linstow35 | MMC: 26 males, mean age 27.1 yrs (SD 5.2) | Own questionnaire | 8/26 (31%) no erections 18/26 (69%) have erections: -5/18 (28%) have “hard” erections -6/18 (33%) “soft” -7/18 (39%) unknown |

2/26 (8%) had not tried to ejaculate 8/26 (31%) do not ejaculate 16/26 (62%) ejaculate |

||||

| Vroege36 | MMC: 8 men ≥19 yrs | Sexual contact: 6/8 (75%) Sexual intercourse: 5/8 (63%) |

Own questionnaire | Sexual fantasies in 6/8 (75%) Desire for sexual contact in 7/8 (88%) |

“About their present sexual life”: 2/8 (25%) dissatisfied, 2/8 (25%) neutral, 4/8 (50%) satisfied |

Abbreviations: SB (spina bifida); yrs (years); HC (hydrocephalus); HC+ (with hydrocephalus); HC− (without hydrocephalus); N/A (not applicable or available); MMC (myelomeningocele); LMC (lipomyelomeningocele); LOL (level of lesion); IIEF (International index of erectile function); SA (sexually active); SI (sexually inactive); TR (Theoretic Rank); VP (ventriculoperitoneal); CIC (clean intermittent catheterization); ED (erectile dysfunction); SHIM (sexual health inventory for men); WSFQ (Watts Sexual Function Questionnaire); VP (ventriculoperitoneal); MC (meningocele)

no further population description available

Spina bifida severity index derived from details regarding ambulation, continence management, decubitus ulcers, and presence or absence of ventriculoperitoneal shunt

Sexual Desire

Sexual desire appears to be least impacted by SB, although it may be somewhat lower in men who are not sexually active.23,37 Sawyer and Roberts reported that 19/24 men (79%) had sexual fantasies.4 Using validated questionnaires in sexually active men, Gamé, Choi, and Lassmannn found that their mean scores were considered “normal”, defined as either similar to normal controls from the validation trials of the IIEF19,23,25 or established norms of the Watts Sexual Function Questionnaire (WSFQ).37 However, Choi and Lee reported somewhat lower scores in non-sexually active men and a mixed group of sexually active and inactive men.23,27 Verhoef was the only study reporting lower sexual desire in men with hydrocephalus,34 whereas other studies demonstrated no significant difference in sexual desire based on hydrocephalus or VP shunt, as well as mobility, incontinence, use of intermittent catheterization for bladder management, mobility status, level of lesion, sacral nerve root involvement, urologic surgery during childhood, rectal/anal problems, impaired urethral relaxation, presence of a urinary diversion, or living arrangement.23,25,27

Erectile Function

Most men with SB can achieve an erection, with reported ranges between 56-95.5%.4,13,22,24,28,30-33,35 However, the quality of erections is often reported as poor. Overall, studies reported that 13-71% of men experience moderate to severe erectile dysfunction or “soft erections”,23,25,27,35 , while 8-83% of men report no erectile dysfunction or “hard erections” (Table 3).22,23,25,27,30,33,35 When limiting the results to only studies that evaluated sexually active men, 12-31% reported moderate to severe erectile dysfunction and 25-83% reported normal erectile function.23,25,32,33

Table 3.

Summary of reported erectile quality.

| Study | Population | Sexual Activity | No ED or “hard erections” |

Moderate to severe ED, “soft erections”, or “erections not firm enough for any sexual activity” |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi23 | 47 men with MMC or LMC | Only sexually active | 16/24 (67%) | 3/24 (13%) |

| Gamé25 | 40 men with MMC | Only sexually active | 4/16 (25%) | 5/16 (31%) |

| Lee27 | 17 men with SB | Unknown | 1/17 (6%) | 12/17 (71%) |

| Roth30 | 122 men with SB | Unknown | 50/122 (41%) | 49/122 (40%) |

| Shiomi32 | 11 men with SB | Only sexually active | 5/11 (45%) | |

| Verhoef33 | 28 men with AHC+, 13 with AHC−, 12 with SB occulta | Only sexually active (defined as French kissing or more) | 44/53 (83%) | |

| von Linstow35 | 26 men with MMC | Unknown | 5/18 (28%) | 6/18 (33%) |

Studies have looked for predictors of erectile outcomes, such as level of lesion, ambulatory status, presence of a VP shunt, tactile sensation of the genitalia, and the sacral reflex arc. Most studies found that the lower the level of lesion, the more likely to achieve an erection (Table 4).13,24,27,31,33 Sandler and colleagues also found an increase in normal nocturnal erections (four or more erections lasting 15 minutes or longer) in men with lower sensory level of lesion.31 However, level of lesion is not necessarily associated with the improved quality of an erection. Two studies, one including only sexually active men and one a mix of sexually active and inactive men, demonstrated no difference in the quality of erections based on level of lesion,23,32 while another study with a mix of sexually active and inactive men found lower levels of lesion were associated with improved quality of erections.27 The impact of ambulatory status is less clear. Most studies demonstrated no difference in the ability to achieve erections based on the Sharrard classification of lower extremity paralysis32 or the quality of erections based on ambulatory status.23,25,27 However, an online international survey of 122 men reported that ambulatory status was most predictive of erectile function, with those who were wheelchair-bound or able to ambulate only during therapy having the worst function.30 Studies are also mixed as to whether the presence of a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt impacts erectile function. Two studies reported that a VP shunt was associated with worse erectile function,24,34 while four studies report no difference.23,25,30,33 Not surprisingly, tactile sensation of the genitalia improves the ability to get an erection by facilitating reflexogenic erections,31,32 but has not been shown to improve the quality of erections based on IIEF scores.32 Two studies have demonstrated that the presence of an intact sacral reflex arc appears to be the most consistent independent predict the ability to achieve erections. Combining Diamond and Gamé et al’s studies, 37/39 (95%) men with an intact sacral reflex and 9/29 (31%) without achieved erections.13,25

Table 4.

Ability to achieve erections based on level of lesion.

Several studies investigated other potential causes of ED in men with SB. Dik and colleagues studied 13 men who could achieve erections before performing a bladder neck sling to improve urinary continence using rectus abdominis fascia, and found that 12 had unchanged erections after surgery and 1 had impaired erections that improved, but new antegrade ejaculation.38 Decter and colleagues 40/44 (90%) of men in their study had normal testosterone, suggesting hypogonadism may not be a major contributor to ED in men with SB.24 Gamé looked at several other factors that could influence erectile function, such as urologic surgery, rectal/anal problems, urinary diversion, impaired urethral relaxation, incontinence, and living arrangements, and found that living independently was associated with significantly improved erectile function, likely related to lower disability overall.25

Ejaculatory Function

While less studied, ejaculatory function may be more impacted than erectile function, with 50-88% of men with SB reporting the ability to ejaculate,4,23,24,32,35 and 52% experiencing nocturnal emissions.4 Interestingly, 5-13% of men may ejaculate without an erection.24,31 Overall, the quality of ejaculations is often reported as poor,23 described as ”dribbling”,31 insensate,24 or only present in the urine, consistent with retrograde ejaculation.31

While Choi found no difference in ejaculatory function based on level of lesion, most studies found ejaculatory function was significantly better in men with lower levels of lesion.23,24,32,33 Choi also found no difference based on the presence of a VP shunt or hydrocephalus, while Decter and Verhoef’s study reported those with a VP shunt had more ejaculatory dysfunction than those without.23,24,33 No study found ambulatory status correlated with erectile function.23

Orgasmic Function

Orgasm occurs less frequently than ejaculation, with 20-67% of men reporting the ability to orgasm and studies varying on what predicts better function.4,23-25,32 Verhoef found the absence of hydrocephalus and a lower level of lesion (below L2) predicted better function.33 However, Shiomi et al did not find any difference based on Sharrard classification and Lee did not find any difference based on ambulatory status.27,32 Shiomi and colleagues found that tactile sensation did predict orgasmic function: 16/19 (84%) men with tactile sensation compared to 1/7 (14%) men without could orgasm.32

Treatment for Male Sexual Dysfunction

Research on the treatment of sexual dysfunction for males with SB has focused on the phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE5i) sildenafil and the “TO-MAXimize sensation, sexuality, and quality of life” (TOMAX) procedure, a microsurgical nerve transfer surgery to establish glans sensation.

Palmer and colleagues conducted a prospective, blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose escalation, crossover study evaluating the efficacy of sildenafil in 15 men with SB with a wide range of level of lesion (5 thoracic, 3 lumbar, 4 sacral).39,40 The efficacy of treatment was evaluated by 4 parameters pre- and post: 1) rating the quality of erections, 2) duration of erections, 3) frequency of erections, and 4) confidence to obtain an erection. Twelve of 15 men (80%) reported improvement in erectile function based on all 4 parameters with both 25 and 50mg sildenafil, with greater effect found with the higher dose. A third of men experienced minor adverse events, such as dyspepsia or nausea, and two men experienced hematologic changes that reverted to baseline.39,40

Overgood and colleagues performed the first large trial of the TOMAX procedure, which involves microsurgical anastomosis of the ilioinguinal nerve with the dorsal penile nerve unilaterally with the goal of creating glans sensation.7,41,42 Their initial study included 18 with SB ages 13-40 (median age 18.5) with level of lesion between L2-S1 with no penile sensation but intact sensation along the ilioinguinal nerve distribution.41 In order to preserve an intact S2-4 reflex arc, if present, and therefore the ability to achieve reflexogenic erections, patients were both questioned about their ability to achieve reflexogenic erections and the presence of a reflex arc was evaluated using EMG-BCR. If there was an intact reflex arc on one side, the surgery was performed on the contralateral side. Post-operatively, 17/18 men with SB (94%) developed unilateral glans sensation, 9 experiencing the sensation in their inguinal area and 8 in the glans itself. All men with the ability to achieve erections and ejaculate pre-operatively were also able to do so post-operatively, but for 5 men in the larger study, and especially those who developed sensation at the glans, this changed from psychogenic-only erections to combined psychogenic and reflexogenic erections. While there was no significant change seen in psychosexual functioning, patients reported other positive outcomes, such as becoming more strongly aroused. One man reported decreased satisfaction.41 The authors have subsequently performed the procedure bilaterally on 3 men with absent sacral reflex arcs bilaterally. Two of the 3 developed bilateral sensation, while the third had undergone the procedure too recently to report results.42

The authors shared several relevant learning points since expanding their experience.7 First, despite having a sacral level lesion, some men nonetheless have an intact sacral reflex arc based on EMG-BCR or report reflexogenic erections. For these patients, the surgery should be performed unilaterally on the contralateral side (if the arc is present unilaterally) in order to preserve reflexogenic erections.7 Second, all men who had prior inguinal or other surgery with a scar over the course of the ilioinguinal nerve (e.g., after inguinal hernia repair) had unusable nerves on that side. Additionally, the authors discovered that the ilioinguinal nerve was congenitally absent in 3 patients bilaterally and 2 patients unilaterally. Their attempt to use the iliohypogastric in one patient with a long enough nerve was not successful. Therefore, they caution patients that there is a 7-12% risk of not being able to perform the surgery due to an absent nerve.7

Jacobs and colleagues also performed this surgery on 2 patients with low-level SB and found that both achieved erogenous sensation by 6 months post-operatively.43 By 24 months post-operatively, both also reported enhanced sexual activity and no difficulties with erections.43

Female Sexual Function

Female sexual function among people with SB has been less studied than male sexual function, with 14 studies meeting criteria for inclusion (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of studies on female sexual function.

| Study | Population | Sexual Activity |

How sexual function was assessed |

Sexual Function |

Desire/Arousal | Lubrication | Orgasm | Satisfaction | Pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardenas3 |

SB*: 69 females ≥15 yrs HC Status: 33 HC− and 36 HC+ |

HC Status: 21/33 (64%) HC− and 16/36 (44%) HC+ -no significant difference |

Perceived Quality of Life Scale (PQOL) | Mean score for “satisfaction with level of sexual activity”: HC− 7.17 (±3.61), HC+ 7.53 (±2.86) | |||||

| Choi EK44 |

MMC or LMC: 44 females (mean age 28.8 yrs, range 20-47) from a single institution SB type: 18/44 (41%) MMC, 26/44 (59%) LMC LOL: 13/44 (30%) lumbar, 7/44 (16%) lumbosacral, 24/44 (52%) unknown |

20/44 (45.5%) had sexual intercourse in the last month -No difference by: age, marital status, CIC, LOL, urinary incontinence -SA more likely to not need mobility aids (18/22 no aids vs 2/11 with aids SA) | FSFI in SA and SI (reported separately) |

SA: Mean 24.68 (±4.20) (TR 2.0-36.0, NV >26) -sexual dysfunction in 11/20 (55%) -No difference by: SB type, HC, mobility, CIC SI: Mean: 3.64 (±1.22) -p<0.001 for difference between SA and SI |

DESIRE: SA: Mean: 3.33 (±0.96) (TR 1.2-6.0) SI: Mean: 2.20 (±0.93) -p<0.001 for difference between SA and SI AROUSAL: SA: Mean: 3.64 (±0.98) (TR 0-6.0) SI: Mean: 0.11 (±0.30) -p<0.001 for difference between SA and SI |

SA: Mean: 5.10 (±0.91) (TR 0-6.0) SI: Mean: 0.11 (±0.55) -p<0.001 for difference between SA and SI |

SA: Mean: 3.60 (±1.15) (TR 0-6.0) SI: Mean: 0.00 (±0.00) -p<0.001 for difference between SA and SI |

SA: Mean: 1.52 (±0.94) (TR 0-6.0) SI: Mean: 1.22 (±0.43) -p<0.001 for difference between SA and SI |

SA: Mean: 4.48 (±1.29) (TR 0-6.0) SI: Mean: 0.00 (±0.00) -p<0.001 for difference between SA and SI |

| Gamé45 |

MMC: 25 females >18 yrs (mean age 27.61 ±6.13) HC: 21/25 (84%) HC+, 4/25 (16%) HC− LOL: 1/25 (4%) T12, 4/25 (16%) L2, 2/25 (8%) L3, 3/25 (12%) L4, 10/25 (40%) L5, 4/25 (16%) S1, 1/25 (4%) S2 |

10/25 (40%) sexually active within the last 4 weeks -SA more likely to have left their parents’ home (8/10 SA versus 8/25 SI, p=0.041) |

BISF-W in SA/SI combined |

SA/SI: Composite score: 29.21 (±12.48) (TR-16 to +75, NV 33.60) -no difference by: living or employment status, driver’s license, HC, isolated lumbar lesion, or impaired sphincter relaxation |

DESIRE: SA/SI: Mean: 1.86 (±2.33) (TR 0-12, NV 5.26) -Lower scores: urinary incontinence and using incontinence pads AROUSAL: SA/SI: Mean: 3.94 (±2.97) (Normative Value 6.21, TR 0-12) |

SA/SI: Mean: 3.75 (±2.17) (TR 0-12, NV 4.91) |

RELATIONSHIP SATISFACTION: SA/SI: Mean: 5.76 (±3.78) (TR 0-12, NV 8.90) |

||

| Gatti26 |

SB aperta and occulta: 170 females ≥18 yrs LOL: 20/170 (12%) L2 and above, 87/170 (51%) L3-L5, 63/170 (37%) sacral |

Sexual contact: 4/20 (22%) L2 and above, 13/87 (15%) L3-L5, 11/63 (18%) sacral (p<0.05) | Own questionnaire | ||||||

| Lassmann37 |

SB*: 34 females ≥18 yrs |

9/34 (27%) had intercourse in the last 2 months | WSFQ in SA only | Mean: 61.6 (±8.4) (TR 18-85) |

DESIRE: Mean: 20.2 (±3.1) (max score 30) AROUSAL: Mean: 16.4 (±2.6) (max score 20) |

Mean: 12.4 (±2.6) (max score 20) | Mean: 12.4 (±2.8) (max score 15) | ||

| Lee27 |

SB*: 28 females ≥18 yrs |

Unknown | FSFI in SA/SI combined | Median: 5.0 (IQR 2.7-17.2) |

DESIRE: Median: 4.0 (IQR 2.0-2.6) AROUSAL: Median: 0.0 (IQR 0.0-6.3) |

Median: 0.0 (IQR 0.0-7.0) | Median: 0.0 (IQR 0.0-3.5) | Median: 4.0 (IQR 1.5-9.5) | Median: 0.0 (IQR 0.0-12.3) |

| Lindehall28 |

SB*: 15 females on CIC |

8/15 (53%) in a relationship (sexual activity unknown) | Qualitative Interview | 15/15 unsure if they had adequate lubrication | 15/15 unsure if they could orgasm | ||||

| Sawyer and Roberts4 |

MC or MMC: 27 adolescents and young adults |

19/27 (70.4%) had kissed someone in a sexual way, 13/27 (48.1%) had further sexual activity, 10/27 (37.0%) had intercourse | Own questionnaire | 20/27 (74.1%) had sexual fantasies | 10/27 (37.0%) had experienced an orgasm -10/10 (100%) of those who had experienced intercourse |

||||

| Streur46 |

SB aperta or occulta: 25 women mean age 27 yrs (range 16-52) |

17/25 (68%) experienced sexual intercourse | Qualitative interviews | Reports of pain due to pelvic organ prolapse and in hips/back with sexual positioning | |||||

| Valtonen47 |

MMC: 18 females |

Own questionnaire | Median satisfaction with sex life was 8 (IQR 5-9.25) (Likert scale 1-10) | ||||||

| Verhoef33 |

SB aperta or occulta: 105 females ages 16-25 yrs from 11 clinics |

62/105 (60%) sexually active (including French kissing and masturbating) SB type: 32/70 (46%) SB aperta HC+ 8/9 (89%) SB aperta HC− 22/25 (88%) SB occulta -significant difference (p<0.001) LOL: 19/43 (44%) L2 and above 25/38 (66%) L3-L5 18/22 (82%) sacral -significant difference (p<0.01) |

Interview and physical exam | “Problems with lubrication” in SA SB type: 2/32 (6%) with SB aperta HC+ 0/8 (0%) SB aperta HC 3/22 (14%) SB occulta -no significant difference By LOL: 1/19 (5%) L2 and above 3/25 (12%) L3-L5 1/18 (6%) sacral -no significant difference |

“Problems with orgasm” in sexually active By SB type: 15/32 (47%) SB aperta HC+ 3/8 (38%) SB aperta HC− 5/22 (23%) SB occulta -no significant difference By LOL: 9/19 (47%) L2 and above 9/25 (36%) L3-L5 5/18 (28%) S1 and below -no significant difference |

||||

| Verhoef34 |

SB aperta or occulta: 93 females ages 16-25 from 11 clinics |

“Sexual intercourse in the last yer” 12/32 (38%) HC− 9/69 (13%) HC+ | Interview and physical exam HC− includes SB aperta HC− and SB occulta |

“Desire sexual contact”: 31/32 (96%) HC 41/69 (59%) HC+ -Significant difference (p<0.05) “Sexual fantasies”: 23/32 (71%) HC− 32/69 (46%) HC+ -Significant difference (p<0.05) “Experiencing only sometimes or never, during masturbation or sexual contact” “feelings of sexual excitement”: 2/21 (10%) HC-12/32 (38%) HC+ -Significant difference (p<0.05) |

“Experiencing only sometimes or never, during masturbation or sexual contact”: 2/21 (10%) HC− 2/32 (6%) HC+ -No significant difference |

“Experiencing only sometimes or never, during masturbation or sexual contact”: 6/21 (29%) HC− 15/32 (47%) HC+ -No significant difference |

“Satisfied with present sex life”: 20/32 (63%) HC− 34/69 (49%) HC+ -No significant difference |

“During masturbation or sexual contact regularly or often experiencing” genital pain: 0/21 (0%) HC− 2/32 (6%) HC+ -No significant difference |

|

| Von Linstow35 |

MMC: 27 females ages 18-35 |

Own questionnaire | 15/27 (56%) reported normal vaginal lubrication, 1/27 (4%) sparse, 10/27 (37%) unsure | ||||||

| Vroege36 |

MMC: 3 women ≥19 yrs |

Sexual contact: 0/3 (0%) Sexual intercourse: 0/3 (0%) |

Own questionnaire | About their present sexual life: 1/3 (33%) Dissatisfied 1/3 (33%) Neutral 1/3 (33%) satisfied |

Sexual fantasies: 2/3 (67%) Desire for sexual contact: 3/3 (100%) |

Abbreviations: SB (spina bifida); yrs (years); HC (hydrocephalus); HC+ (with hydrocephalus); HC− (without hydrocephalus); N/A (not applicable or available); MMC (myelomeningocele); LMC (lipomyelomeningocele); LOL (level of lesion); CIC (clean intermittent catheterization); SA (sexually active); FSFI (Female Sexual Function Index); SI (sexually inactive); TR (Theoretic Rank); NV (Normative Value); BISF-Q (Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women) WSFQ (Watts Sexual Function Questionnaire); MC (meningocele)

no further population description available

Desire

Of all sexual function domains, a woman’s reported sexual desire appears to be the least affected by SB. While most studies demonstrate fairly normal sexual desire in all women with SB,4,27,37 one study found that those who are not sexually active had lower FSFI scores for desire,37 and another study found low sexual desire overall.45 One study found desire did not significantly different based on a woman’s level of lesion or ambulatory status.27 Lower desire was associated with urinary incontinence in one study45 and with the presence of hydrocephalus in another.34

Arousal

Sexual arousal appears to be impacted by SB to some degree, although this is likely exaggerated in those studies that used validated questionnaires in sexually inactive women. Lassmann and Choi’ studies, which both included only sexually active women, showed minimal to mild impairment.37,44 Studies who included both sexually active and inactive women reported worse outcomes, which may be more reflective of sexual inactivity than true arousal function.27,45 One study found that urinary incontinence was associated with lower arousal,37 while another found hydrocephalus was associated with problems with sexual excitement.34

Lubrication

Interestingly, although lubrication should, in theory, be profoundly impacted in females with SB, most studies of sexually active women reported that women either had adequate lubrication or they were unsure, with 0-14% experiencing problems with lubrication.28,33-35,44 Verhoef reported no difference based on type of SB or level of lesion.33,34 Not surprisingly, those studies that used validated instruments in sexually inactive women found low scores, likely reflecting sexual inactivity and not the ability to produce lubrication.27,44 Lindehall and von Linstow both asked if women were aware of their ability to emit lubrication, and found that 15/15 (100%) and 10/27 (37%), respectively, were unsure.28,35

Orgasm

The ability to achieve orgasm does appear to be impacted by SB, although reports vary widely about the degree of the impact. Of those studies that only included only sexually active women, 0-47% reported “problems with orgasm”.4,33,34 Choi’s study of sexually active women reported a mean FSFI score for orgasm of 3.60 (±1.15) (TR 0-6.0)35 and Lassmann, a mean WSFQ score of 12.4 (±2.6) (maximum score of 20). Not surprisingly, those studies that included women who were not sexually active reported lower scores.27,45 No study found a significant difference based on level of lesion/functional status,27,33,44 hydrocephalus status,33,34 or type of SB.33,44 Additionally, no difference was reported by factors such as living and employment status,45 urinary sphincter activity,45 or bladder management type.44

Pain

Women with SB have many risk factors for pain during intercourse. Two studies reported that pelvic organ prolapse appears to be common even in young nulliparous women with SB, and for some, this caused dyspareunia.48,49 Qualitative interviews in one study also corroborated pelvic organ prolapse causing dyspareunia and described hip and back pain as another source of pain during partnered sexual intercourse.46 However, two studies of sexually active women reported low pain overall. In Verhoef’s study, only 2/53 (4%) of women reported pain during masturbation or sexual contact, with no difference based on hydrocephalus status.34 Using the FSFI, Choi’s study reported a mean score reflective of pain occurring only half the time or better, although there was a wide range in their population. They found women who were continent of urine experience less pain than those who were incontinent, possibly reflecting disability status.44

Overall sexual function

Composite sexual function scores demonstrate that overall, women with SB experience sexual dysfunction.27,37,44,45 The range in reported scores is wide, likely reflective of both the heterogeneity of women included in the studies and the inclusion of non-sexually active women in some studies. Choi’s study, which included only sexually active women, and Gamé’s study, which included both sexually active and inactive women, reported composite sexual function scores just below the accepted normative values.27,44 Lee’s study reported the most profound overall sexual function, although this score was likely mostly reflective of sexual activity.27 No SB-related factor was found to predict sexual dysfunction, including hydrocephalus status,44,45 type of SB,44 level of lesion,44 living or employment status,45 isolated lumbar lesion,25 or impaired sphincter relaxation.45

Treatment

Unlike for men, there have been no studies focused on treatment of sexual dysfunction for females with SB. In a qualitative study, Streur and colleagues reported that women felt that having a supportive and affirming partner who would work to find comfortable positions and who did not care about incontinence increased their enjoyment of sex.37

Sexual Satisfaction in Men and Women

All studies demonstrated diminished sexual satisfaction in both men and women with SB, although the extent of dissatisfaction was highly variable.23,25,27,34,37,44,45,47 This variability is likely due, at least in part, to the heterogeneity of the people included as well as the inclusion of non-sexually active men and women in some studies. Among men, reported predictors of better satisfaction included lower level of lesion, living independently, impaired urethral relaxation on urodynamics.25,27 Ambulatory status, hydrocephalus, and continence does not appear to influence intercourse satisfaction for men.23,25,27 Among women, younger age and being sexually active was associated with increased satisfaction,44,47 while hydrocephalus status did not appear to influence satisfaction outcomes.34

Overall satisfaction with one’s sex life of both males and females together or comparing males and females was evaluated in eight studies (Table 6). While comparing outcomes is difficult due to the use of differing questionnaires, most studies found no difference in overall satisfaction between genders, with those finding a difference reporting that females were more satisfied. Cardenas, Lassmann, Verhoef, and von Linstow demonstrated that in a combined total of 184 males and 214 females, there was no significant difference in satisfaction between males and females.3,34,35,37 Conversely, Barf and Valtonen found that among 97 men and 123 women, the women were significantly more satisfied.47,50

Table 6.

Summaries of studies comparing male and female sexual function.

| Study | Population | Sexual Activity | How sexual function was assessed |

Sexual Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barf50 |

SB aperta or occulta 179 people ages 16-25 yrs (74 males, 105 females) from 11 clinics Comparison group: 132 people without SB ages 18-25 yrs SB type 37/179 (21%) SB occulta, 23/179 (13%) SB aperta HC− 119/179 (66%) SB aperta HC+ |

Unknown | Life Satisfaction Questionnaire |

Overall: 81/179 (45%) satisfied with sex life vs 73/132 (55%) of control group SB Type: 17/32 (54%) SB occulta 14/23 (59%) SB aperta HC−, 46/119 (39%) SB aperta HC+ satisfied LOL: Those with a higher LOL less satisfied than those with lower LOL (OR 2.84, CI 1.31-6.15, p<0.01) Gender: Males less satisfied than females (OR 3.05, CI 1.04-2.73, p<0.05) |

| Bomalaski22 |

SB aperta: 38 people (18 males and 20 females) median age 24 yrs (range 18-47) from a single institution |

3/16 (13%) males and 8/15 (53%) of women had intercourse -significantly different (p<0.005) |

||

| Cardenas3 |

SB* 121 people ages 15-35 yrs (52 males, 69 females) HC: HC+ 25/52 (48%) males and 36/69 (52%) females HC− 27/52 (52%) males and 33/69 (48%) females |

13/27 (48%) HC− males, 17/25 (68%) HC+ males, 21 HC− females, 16/36 HC+ females -no significant difference |

Perceived Quality of Life Scale (PQOL) |

PQOL satisfaction with level of sexual activity: Male HC− 5.77 (±3.24), Male HC+ 4.28 (±3.34); Female HC− 7.17 (±3.61); Female HC− 7.53 (±2.86) -No significant difference by gender or HC |

| Gatti26 |

SB aperta or occulta 295 people ≥18 yrs (125 male, 170 female) |

More likely to be sexually active: men (OR 2.1), older (OR 1.1), lower LOL (OR 3.4) | ||

| Lassmann37 |

SB*: 76 people (42 males, 24 females) mean age 24 yrs (range 18-37) |

Intercourse in last 2 months: 9/42 (21%) males, 9/24 (27%) females LOL: 4/28 (14%) Thoracic, 0/2 (0%) L1, 7/21 33%) L3, 3/19 (16%) L4-5, 4/6 (67%) sacral -significantly different (p<0.05) Shunt Status: 11/63 (17%) with a shunt, 7/13 (54%) without -significantly different (p<0.05) |

WSFQ in SA only | WSFQ score for satisfaction in SA: M 13.3 (±1.3), F 12.4 (±2.8) (maximum score 15) -not significantly different -no significant difference for all WSFQ domains (desire, arousal, orgasm, satisfaction) |

| Valtonen47 |

MMC: 41 people (23 male, 18 female) mean age 31.1 yrs (range 19.6-50.5) |

Questionnaire made for study | Satisfaction with sex life: Gender: M median score 5, F median score 8 (p<0.05) (score range 0-10, 10 is best) Sex Counseling: those who reported sufficient sex counseling more satisfied (p=0.012) Living with a partner: increased satisfaction for males (p=0.041) not females (p=0.963) |

|

| Verhoef34 | SB aperta or occulta: 157 people (64 males, 94 females) mean age 20.8 yrs (range 16-25) |

35/157 (22%) had experienced sexual intercourse; 74/157 (47) had experienced sexual contact (French kissing or other exciting contact); females (OR 2.4) and HC− (OR 9) more likely to have sexual contact | Questionnaire made for study | 82/157 (52%) satisfied with current sex life Gender: no significant difference HC: HC− twice as likely to be satisfied than HC+ |

| von Linstow35 |

SB*: 53 people (26 male, 27 female) mean age 27.1 yrs (range 18-25) LOL: 7/53 (13%) cervical, 16/53 (30%) thoracic, 30/53 (57%) lumbosacral Completeness of lesion: 5/53 (9%) complete, 48/53 (91%) incomplete HC Status: 38 HC+, 15 HC− |

Unknown | Questionnaire made for study | Sex life in last year described as: Total failure- 17/53 (32%) Dysfunctional- 10/53 (19%) Fairly functional- 13/53 (25%) Well-functioning- 13/53 (25%) Satisfaction with sex life: 25/53 (45%) satisfied 16/53 (30%) wish it was different but accept sex life 9/53 (17%) unhappy and wish it was different 4/53 (8%) unhappy and it affects whole life negatively -No difference: gender, HC, urinary continence -Significant difference: -Higher LOL associated with more dissatisfaction with sex life (57% C, 38% T, 10% LS dissatisfied) -Those in a relationship more satisfied (p=0.07) -Those with fecal continence more satisfied (p=0.022) |

Abbreviations: SB (spina bifida); yrs (years); HC (hydrocephalus); HC+ (with hydrocephalus); HC− (without hydrocephalus); LOL (level of lesion); MMC (myelomeningocele); SA (sexually active); WSFQ (Watts Sexual Function Questionnaire)

no further population description available

Many different factors were evaluated for predictors of satisfaction for men and women together. Cardenas and von Linstow showed no difference in satisfaction based on hydrocephalus status.3,35 While Verhoef found no difference in sexual satisfaction based on hydrocephalus status among men and women individually on bivariate analysis, on multivariate logistic regression testing for “satisfaction with current sex life” among women and women together, they reported that those without hydrocephalus were significantly more satisfied.34 von Linstow and Barf found that men and women with lower level of lesion reported better satisfaction.35,50 von Linstow also demonstrated being in a relationship was associated with greater satisfaction for both men and women,35 while Valtonen found that living with a partner increased satisfaction for males, but not females.47 Valtonen also found that males and females who reported sufficient sex counseling were more satisfied.47

Incontinence Impacting Sexual Satisfaction in Men and Women

Four articles discussed incontinence during sex. In a qualitative study of 6 women and 5 men with SB, some admitted to avoiding sex due to fear of incontinence. One mentioned that their partner ignored the incontinence when it occurred.51 Another qualitative study of women with SB also found that women are anxious about potential urinary and bowel incontinence during sex and frustrated that having to empty their bladder and bowels before sex decreases spontaneity. One woman reported that having a supportive partner who did not mind the incontinence is helpful.46 von Linstow reported that fecal but not urinary incontinence impacts satisfaction with sex life for people with SB, with all 9 people reporting fecal incontinence daily or weekly also describing their sex life as a “total failure/dysfunctional”.35 Among men, Gamé found that erectile function and sexual desire was not different between men who were and were not continent of urine.25

Discussion

Research on sexual function in people with SB is currently limited. However, it appears that for both men and women, sexual desire is the least impacted by SB, indicating the importance of providers counseling their patients about sexual health and asking about any concerns about their sexual function, regardless of the mobility, level of lesion, or hydrocephalus status of that patient. For men, overall sexual function appears to be improved with lower levels of lesion. However, this is variable, with some men of all levels of lesion reporting good sexual function. While most men can have erections, the quality is often poor. It appears fewer men can ejaculate or experience orgasm, with ejaculation often occurring as dripping, retrograde, or insensate. PDE5 inhibitors are beneficial for the treatment of erectile dysfunction for most men with SB, while treatment of ejaculatory and orgasmic dysfunction is lacking. The TOMAX procedure is promising for those with low level lesions. Less is understood about female sexual function. Arousal, orgasm, and pain appear to also be impacted by SB, although reports vary as to the extent and it is unclear how SB features, such as level of lesion, impact sexual function. No studies focused on the treatment of female sexual dysfunction in this population. Incontinence during intercourse appears to be very bothersome to many men and women with SB, but has been incompletely explored in current studies. Overall satisfaction is reported as universally diminished in all studies.

Interestingly, the studies on men appear to demonstrate that overall, men with lower levels of lesion have better sexual function outcomes. This is initially counterintuitive, as men with sacral lesions should, in theory, have the worst outcomes because the S2-4 nerve roots are classically described as responsible for erectile function. There are a variety of possible explanations for this. From a physiologic standpoint, the bony level of SB lesions often do not match the functional level of the neurologic deficit. Some men may have incomplete lesions and variable spinal cord involvement.7 Indeed, SB is known as the “snowflake condition” as people with even the same level of lesion often have different clinical outcomes.1 Additionally, as Overgoor has suggested,7 studies have demonstrated that there are variations in the location of the erection centers52,53 as well as possible inter-segmental nerve connections that could allow for persistent neurotransmission despite a lesion at the level of an erection center.54-56 From a methodological standpoint, this could be due to the inclusion of men with more minor lesions such as SB occulta or lipomeningocele in some studies, as they would be expected to have less neuropathy and better overall sexual function. It could also be due to how the comparison groups in the individual studies were created, with some studies lumping those with lumbar and sacral lesions together despite the fact that they are expected to have different outcomes. Finally, it is likely that the level of lesion was found as the most consistent predictor because it was most consistently tested. While level of lesion information can be easily and non-invasively obtained for the purpose of a study, other predictors that may be superior require more involved physical exams, increasing the complexity and commitment to the study for both the man and the researcher. For example, Diamond and Gamé demonstrated in their small cohorts that the presence of an intact sacral reflex arc, not the level of lesion, was the best predictor of male sexual function.13,25

There are several limitations to interpreting the current research. First, direct comparison between studies is difficult. Researchers have used a wide variety of sexual function survey instruments with varying outcomes, several different systems to classify participants (e.g., Sharrard classification57 versus level of lesion), and have included participants with less severe lesions, such as SB occulta or meningocele, without reporting outcomes by subtype. Second, meaningful comparisons of outcomes by different SB features within the same study is also limited, as most studies are small with highly diverse populations. Third, it is difficult to determine the impact of hydrocephalus on sexual function. Hydrocephalus is typically associated with higher levels of lesion and more severe forms of SB (myelomeningocele), making it difficult to determine if sexual function is due to the type and level of lesion or hydrocephalus status. Fourth, many studies administered surveys intended only for sexually active men and women in those who were not sexually active, leading to low scores reflective of sexual inactivity and not sexual function.19,20 Fifth, there are no validated sexual function questionnaires for people with SB. It is possible that people with SB, a congenital spinal defect, may have different perceptions of what constitutes good sexual function than those without SB, or who experience a change in sexual function due to age, injury, or disease. Other factors, such as urinary and fecal continence or pain for men with SB, may influence sexual function and sexual satisfaction for people with SB and may need to be included in these questionnaires. Sixth, what was not asked, such as whether men experience pain during intercourse, cannot be reported. Specific to women, older versions of the FSFI used in the studies were intended for heterosexual women, and were not applicable to those with other sexual orientations.27,44 An international online survey of 119 women with SB demonstrated that 10.4% identified as “bisexual”, while 2.5% identified as “gay/lesbian”.58 While studies vary, this appears to be a higher proportion of women who are bisexual than is reported in the general population.58 Additionally, unlike for men, few studies of women examined predictors of sexual function such as level of lesion. Nonetheless, the growing research in this area does provide sufficient insight to allow providers to counsel patients on expectations.

This collection of research highlights the need for a large multi-center study to better evaluate sexual function and predictors of sexual function in men and women with SB. Ideally, a study would utilize well-accepted validated questionnaires for sexually active men and women as well as interviews, questionnaires, and physical exams for both the sexually active and inactive in order to better understand the sexual function of all people with SB. This study should be inclusive of individuals with different sexual orientations and report outcomes based on age, gender, history of sexual activity, type of SB, level of lesion, ambulatory status, hydrocephalus, and the presence of sacral reflexes and tactile sensation. Ultimately, a validated questionnaire specific to people with SB would be most helpful for advancing the understanding of sexual function and satisfaction in people with SB.

This also demonstrates the critical need for research on the treatment of sexual dysfunction in people with SB, and in particular women. With the growing field of female sexual dysfunction treatment, women with SB should be intentionally recruited for trials, and new treatments that emerge should be tested on this population. A sexual function questionnaire specific to SB may also direct additional research studies. For example, it may elucidate if pelvic organ prolapse significantly impacts women’s sexual function, and if a trial is warranted to evaluate if treatment of the prolapse improves sexual function. For men with SB, other established treatments for erectile dysfunction, such as vacuum erection devices and intracavernosal injections, should also be evaluated. Potential treatments for ejaculatory and orgasmic dysfunction are also needed given the high prevalence of these conditions.

This review is limited by the limitations inherent to the studies included, as described above. Additionally, it does not address the psychosocial aspects of a sexual relationship, which greatly impacts sexual satisfaction, but is even less well understood in this population. Despite these limitations, this provides a comprehensive review of what is currently known about the sexual function of men and women with SB.

Conclusion

Sexual function is impacted by the diagnosis of SB. For men, level of lesion appears to be the greatest predictor of sexual function, while it is less clear what predicts sexual function for females. Future multi-institutional studies that use validated questionnaires appropriately are needed to better understand the sexual function and predictors of sexual function in this population. Established treatments for sexual dysfunction, particularly for women, need to be tested in people with SB. Validated questionnaires specific to men and women with SB would increase the understanding of sexual function and satisfaction in this population, evaluate treatments, and inform additional research needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

This research was funded by a K-12 training grant from the National Institute of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant number 5K12DK111011-04).

Abbreviations

- SB

Spina bifida

- IIEF

International Index of Erectile Function

- FSFI

Female Sexual Function Index

- EMG-BCR

Needle electromyography-bulbocavernous measurements

- TR

Theoretical rank

- SHIM

Sexual Health Inventory for Men

- IQR

Interquartile range

- VP

Ventriculoperitoneal

- WSFQ

Watts Sexual Functioning Questionnaire

- PDE5i

Phosphodiesterase Type 5 inhibitor

- TOMAX

“TO-MAXimize sensation, sexuality, and quality of life” procedure

- BISF-W

Brief Index for Sexual Functioning for Women

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Sources

- 1.What is spina bifida? https://www.spinabifidaassociation.org/what-is-spina-bifida-2/. Accessed 8/16/2020.

- 2.Shin M, Kucik JE, Siffel C, et al. Improved survival among children with spina bifida in the United States. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012;161(6):1132–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardenas DD, Topolski TD, White CJ, McLaughlin JF, Walker WO. Sexual functioning in adolescents and young adults with spina bifida. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2008;89(1):31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawyer SM, Roberts KV. Sexual and reproductive health in young people with spina bifida. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 1999;41(10):671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nehra A, Moreland RB. Neurologic erectile dysfunction. Urologic Clinics of North America. 2001;28(2):289-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afferi L, Pannek J, Louis Burnett A, et al. Performance and safety of treatment options for erectile dysfunction in patients with spinal cord injury: A review of the literature. Andrology. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overgoor ML, Braakhekke JP, Kon M, De Jong TP. Restoring penis sensation in patients with low spinal cord lesions: the role of the remaining function of the dorsal nerve in a unilateral or bilateral TOMAX procedure. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(4):343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapelle PA, Durand J, Lacert P. Penile erection following complete spinal cord injury in man. British journal of urology. 1980;52(3):216–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courtois FJ, Charvier KF, Leriche A, Raymond DP. Sexual function in spinal cord injury men. I. Assessing sexual capability. Paraplegia. 1993;31(12):771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid DM, Curt A, Hauri D, Schurch B. Clinical value of combined electrophysiological and urodynamic recordings to assess sexual disorders in spinal cord injured men. Neurourol Urodyn. 2003;22(4):314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tajkarimi K, Burnett AL. The role of genital nerve afferents in the physiology of the sexual response and pelvic floor function. The journal of sexual medicine. 2011;8(5):1299–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visconti D, Noia G, Triarico S, et al. Sexuality, pre-conception counseling and urological management of pregnancy for young women with spina bifida. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2012;163(2):129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamond DA, Rickwood AM, Thomas DG. Penile erections in myelomeningocele patients. British journal of urology. 1986;58(4):434–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arksey HOM L Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Mishra A, Osterloh IH. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 1999;54(2):346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2005;31(1):1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women. Archives of sexual behavior. 1994;23(6):627–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Peña BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. International journal of impotence research. 1999;11(6):319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2000;26(2):191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watts RJ. Sexual functioning, health beliefs, and compliance with high blood pressure medications. Nursing research. 1982;31(5):278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bomalaski MD, Teague JL, Brooks B. The long-term impact of urological management on the quality of life of children with spina bifida. The Journal of urology. 1995;154(2 Pt 2):778–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi EK, Ji Y, Han SW. Sexual Function and Quality of Life in Young Men With Spina Bifida: Could It Be Neglected Aspects in Clinical Practice? Urology. 2017;108:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decter RM, Furness PD 3rd, Nguyen TA, McGowan M, Laudermilch C, Telenko A. Reproductive understanding, sexual functioning and testosterone levels in men with spina bifida. The Journal of urology. 1997;157(4):1466–1468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Game X, Moscovici J, Game L, Sarramon JP, Rischmann P, Malavaud B. Evaluation of sexual function in young men with spina bifida and myelomeningocele using the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 2006;67(3):566–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gatti C, Del Rossi C, Ferrari A, Casolari E, Casadio G, Scire G. Predictors of successful sexual partnering of adults with spina bifida. The Journal of urology. 2009;182(4 Suppl):1911–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee NG, Andrews E, Rosoklija I, et al. The effect of spinal cord level on sexual function in the spina bifida population. Journal of pediatric urology. 2015;11(3):142.e141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindehall B, Moller A, Hjalmas K, Jodal U, Abrahamsson K. Psychosocial factors in teenagers and young adults with myelomeningocele and clean intermittent catheterization. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. 2008;42(6):539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCloskey H, Kaviani A, Pande R, Boone T, Khavari R. A cross-sectional study of sexual function and fertility status in adults with congenital genitourinary abnormalities in a US tertiary care centre. Cuaj-Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2019;13(3):E31–E65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth JD, Misseri R, Cain MP, Szymanski KM. Mobility, hydrocephalus and quality of erections in men with spina bifida. Journal of pediatric urology. 2017;13(3):264.e261–264.e266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandler AD, Worley G, Leroy EC, Stanley SD, Kalman S. Sexual function and erection capability among young men with spina bifida. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 1996;38(9):823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiomi T, Hirayama A, Fujimoto K, Hirao Y. Sexuality and seeking medical help for erectile dysfunction in young adults with spina bifida. International journal of urology: official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2006;13(10):1323–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhoef M, Barf HA, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, Gooskens RH, Prevo AJ. Secondary impairments in young adults with spina bifida. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2004;46(6):420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verhoef M, Barf HA, Vroege JA, et al. Sex education, relationships, and sexuality in young adults with spina bifida. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2005;86(5):979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Linstow ME, Biering-Sorensen I, Liebach A, et al. Spina bifida and sexuality. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2014;46(9):891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vroege JA, Zeijlemaker BY, Scheers MM. Sexual functioning of adult patients born with meningomyelocele. A pilot study. European urology. 1998;34(1):25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassmann J, Garibay Gonzalez F, Melchionni JB, Pasquariello PS Jr., Snyder HM 3rd. Sexual function in adult patients with spina bifida and its impact on quality of life. The Journal of urology. 2007;178(4 Pt 2):1611–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dik P, Van Gool JD, De Jong TP. Urinary continence and erectile function after bladder neck sling suspension in male patients with spinal dysraphism. BJU international. 1999;83(9):971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer JS, Kaplan WE, Firlit CF. Erectile dysfunction in patients with spina bifida is a treatable condition. The Journal of urology. 2000;164(3 Pt 2):958–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer JS, Kaplan WE, Firlit CF. Erectile dysfunction in spina bifida is treatable. Lancet (London, England). 1999;354(9173):125–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Overgoor ML, de Jong TP, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Edens MA, Kon M. Increased sexual health after restored genital sensation in male patients with spina bifida or a spinal cord injury: the TOMAX procedure. The Journal of urology. 2013;189(2):626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Overgoor ML, de Jong TP, Kon M. Restoring tactile and erogenous penile sensation in low-spinal-lesion patients: procedural and technical aspects following 43 TOMAX nerve transfer procedures. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014;134(2):294e–301e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs MA, Avellino AM, Shurtleff D, Lendvay TS. Reinnervating the penis in spina bifida patients in the United States: ilioinguinal-to-dorsal-penile neurorrhaphy in two cases. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(10):2593–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi EK, Kim SW, Ji Y, Lim SW, Han SW. Sexual function and qualify of life in women with spina bifida: Are the women with spina bifida satisfied with their sexual activity? Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37(5):1785–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Game X, Moscovici J, Guillotreau J, Roumiguie M, Rischmann P, Malavaud B. Sexual function of young women with myelomeningocele. Journal of pediatric urology. 2014;10(3):418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]