Introduction

Roughly 10 million individuals in the United States receive long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) for chronic pain.[9; 37] In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic pain, encouraging non-opioid management, avoiding high dosages, and tapering when risks exceed therapeutic benefits.[15] Multiple states have since introduced policies limiting opioid prescription dosage and duration.[25] While these guidelines and policies reduced prescribing volume,[8] they have had unintended consequences, such as forced tapering.[12; 13; 17] Prior work found primary care physicians (PCPs), who write the majority of opioid prescriptions,[19] are reluctant to care for patients on LTOT.[24] Experts hypothesize that increased prescribing scrutiny and sanctions,[2; 22; 32] fear of harming patients, and inadequate training[10] may affect provider willingness to care for this population. Stigma towards patients on LTOT for chronic pain may also play an important role.[16; 36] Measuring the extent to which clinic decisions depend upon hesitation to care for any patients on LTOT versus patient-specific considerations is a critical missing step in improving access and care for individuals with chronic pain.

Clinics may have policies limiting the number of new patients on LTOT. In these situations, clinic decisions may depend on non-patient-specific factors like panel quotas, and would not be expected to vary systematically with patient opioid use history. However, there is concern that some clinics may limit access for patients with histories suggestive of aberrant use. This gatekeeping practice involving negative attitudes or beliefs about the “outgroup” of individuals on LTOT provides an opportunity to measure potential stigma[11], which social desirability biases make difficult to assess directly. Provider reluctance to discuss potential prescribing with new patients could lead to harmful consequences, including seeking non-prescribed opioids for pain. Similarly, hesitancy to care for patients with potential aberrant use could limit opportunities to engage a high-risk population in care. Understanding the potential role of stigma is crucial to determining whether addressing administrative burden or policies alone will increase primary care access for individuals with chronic pain.

We therefore designed an audit survey, commonly called a “secret shopper” study, to ascertain how the reason for needing a new provider may impact primary care access. Audit studies use simulated patients to minimize social desirability biases, which can complicate traditional surveys.[6; 31] We called clinics accepting new patients twice, and attempted to schedule new patient visits using two scenarios, varying why they needed a new PCP. By calling twice, we aimed to discern whether access was generally limited by clinic-level policies, or differentially depending on the patient’s reason for needing a new PCP. We also assessed whether clinics were restricting access to all primary care, including for non-pain-related conditions. This study builds on a prior single-state study evaluating whether primary care appointment scheduling for individuals on LTOT varied with insurance status. Here, using a larger nine-state sample, we compare discordant responses in both patient acceptance and willingness to continue prescribing based upon patient history, with a secondary aim of examining associations with clinic characteristics such as geographic location.

Methods

We used “secret shopper” audit methodology to investigate access to primary care for chronic pain patients on LTOT in two different call scenarios. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

Clinic Sample

We used IQVIA OneKey, a frequently updated healthcare database listing over 9.6 million practitioners, to obtain records of primary care clinics in 9 different states. We selected three states each from the low (California, Mississippi, Texas), middle (Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania), and high (Massachusetts, Maryland, Ohio) state opioid overdose death rate strata, as reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation.[3] Selecting a sample of states that have been differentially impacted by the opioid epidemic enabled later comparisons across state groups to examine the relationship between overdose death rates and response patterns.

Clinics were excluded from the initial sample provided by IQVIA for the following reasons: not being a primary care clinic, not serving a general population of adults, having an incomplete phone number, having an incomplete count of providers at the clinic, or being duplicate entries based on phone numbers or addresses. To ensure a comparable number of clinics were called from each state, we randomly subsampled each state’s clinic list such that the list of clinics in the eligible sampling frame consisted of an equal number from each state. This amount was equal to the maximum number of clinics available in the state with the lowest representation (n=420). This yielded 3780 clinics, from which our final sample was drawn. A power analysis for our primary analysis using McNemar’s test suggested that at the .05 alpha level and with 80% power, data for both scenarios was needed from 389 clinics to detect a 10% difference in acceptance, assuming that 50% of clinics may be unwilling to accept the patient. The final sample required was increased to 440 clinics to account for potential attrition between call rounds, and all clinic calls that were in-progress when the sample number was reached were completed.

Call Scenarios

Prior stigma-related studies suggest that patients on opioid therapy for chronic pain are subject to three major overlapping types of stigma. First, stigma may manifest as disbelief in the physiological etiology of their pain.[14] Second, there may be underlying skepticism around the efficacy of opioid therapy, irrespective of whether there is perceived addiction. Third, physicians may assume individuals who use opioids for chronic pain have underlying substance use problems. Prior studies also demonstrate patients view this addiction-related stigma as being associated with physicians’ distrust of patients with pain.[21] In some instances, physicians may also describe the need for opioid therapy as “drug seeking,” implying patients may not derive any legitimate medical benefit from opioid therapy and instead have symptoms of a substance use disorder.[5] Using this prior evidence as a t..heoretical construct for the components of stigma relevant to this clinical context, we developed two different scenarios designed to activate different levels of potential stigma from clinic representatives (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which outlines the two call scripts). Potential stigma among clinic representatives at the point of clinic contact was examined in order to represent a patient’s initial scheduling experience and to assess clinic gatekeeping practices. All clinic contact was conducted via telephone to both preserve the anonymity of data collectors and to best simulate first appointment scheduling conditions. Four experts, including an opioid public health researcher, two primary care physicians, and an addiction medicine physician developed the call scenarios. In both scenarios, the simulated patient stated she had been on opioid medication for pain “for years.” In scenario one (retired prompt), the patient stated that her previous PCP retired. In scenario two (stopped prescribing prompt) the patient stated upfront that her previous PCP stopped prescribing her opioid medication without providing an explicit reason for the discontinuation. The expert group felt this would be most consistent with what a patient may say if she were discontinued from opioid therapy from a prior PCP for aberrant use, as opposed to explicitly stating that they had been “cut off” by their provider.

When a clinic representative indicated that the clinic would be unwilling to potentially prescribe opioids for the patient, we also assessed willingness to accept the patient for non-pain-related reasons, asking “I understand they won’t prescribe, but will they still accept me as a new patient?” Thus, willingness to potentially prescribe opioids and willingness to accept a patient on long-term opioid therapy for treatment of other health problems were measured distinctly from one another, and these two variables constituted the focal outcomes of interest. Willingness to prescribe was dichotomized into ‘prescribe,’ which included indications that all or some PCPs would be willing to potentially prescribe and ‘not prescribe,’ which was an explicit declaration that no PCP at the clinic would prescribe opioid medication to the simulated patient. Willingness to accept the patient was defined as any time the clinic said they would see the patient or helped in securing an appointment date. Research assistants (RAs) did not finalize the scheduling of any appointments and ensured no actual appointments were made.

Clinics were first ordered by state to ensure equal sampling across all states over time. Each clinic was then randomly assigned the order in which they would receive the two patient scenarios. Random assignment was done in order to ensure any potential temporal confounds, including caller familiarity with call procedures, time of year, and changes in local policy, affected both scenarios equally. Clinics were called in two separate rounds. In round one, we called enough clinics to ensure an adequate sample size to call each clinic back successfully in round two.

Iterative pilot versions of call scenarios were tested on clinics located in states outside the sample and informed the development of call scripts, protocols, and standardized answers to common questions from clinic staff. Five RAs used the two standardized scripts to make audit calls between May and July 2019. RAs received extensive training in standardized delivery of the scripts as well as how to respond to common questions from clinic staff. All RAs were females of similar age to reduce potential variation elicited by patient gender and were trained to follow the scripts exactly as written to minimize caller variability. If clinic staff asked for the patient’s insurance information, RAs were instructed to first provide the most common PPO for each state as determined from data aggregated from state-specific and national-level sources.[1] If this was unsuccessful, RAs used a standardized method of assessing which plans were accepted by the clinic and selecting an alternative insurer from those in order to proceed with the call. Commonly accepted commercial insurers were used intentionally to streamline the call procedure given that prior work using comparable methodologies suggested insurance type (e.g., Medicaid versus commercial insurance) does not affect patient acceptance.[22] RAs were also trained to capture any “other” responses and qualitative data by noting exact language from the calls. All call information was logged in a REDCap online database. On a weekly basis, the study team convened to review call-related questions and issues as they emerged and arrive at consensus. The conclusions from these discussions were added to the study protocol to ensure consistency in future calls.

Statistical Analysis

Study data were analyzed using R, version 3.5.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The primary analysis for this study was McNemar’s test of correlated proportions, which was performed on a dichotomized version of the acceptance and prescription variables. The anonymity necessary for audit studies as well as the many random clinic level factors could affect respondent decision-making (e.g. different clinic representative, etc.). To address this, the primary analysis assumed random discordance of both types would be present and tested whether they were found in equal proportion in order to assess if one scenario was favored for acceptance or prescription continuance[4; 28]. Because the McNemar’s test evaluates discordance, this analysis was limited to only clinics that had data for both scenarios (n=452). Descriptive analyses examining factors related to clinic characteristics, however, were performed on the entire sample (n=484). For our secondary analyses, we used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEEs) logistic regression to model associations between each scenario and the two outcomes, while including ancillary clinic characteristics such as state as covariates. GEE models take into account the clustered (i.e., paired) nature of the data. Clinic was chosen as the GEE cluster variable to account for intra-clinic similarities. Covariates that were accounted for included state, number of providers, and Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) status, and urbanicity based on the 2010 census.[30]

Results

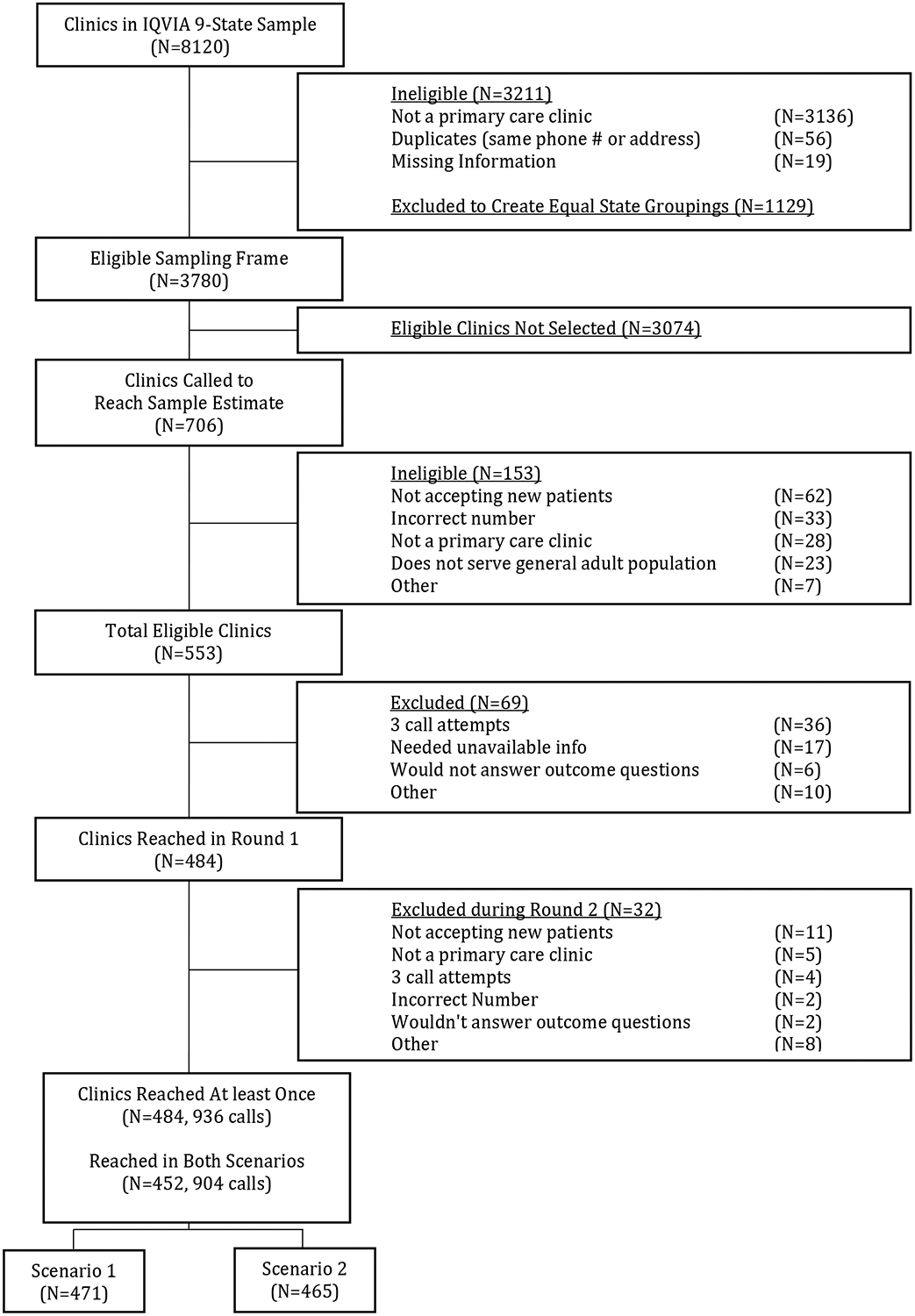

Of the 553 eligible clinics, 484 clinics successfully completed at least one scenario (88% response rate) for a total number of 936 calls. 452 clinics (904 calls) responded to both scenarios (Figure 1).

Fig 1.

Flow chart depicting sample inclusion and exclusion

Of the 484 total clinics, 148 (30.6%) were from states with high overdose rates, 158 (32.7%) from medium-rate states, and 178 (36.8%) from low-rate states (Table 1). Ninety-one (18.8%) of the clinics were single provider clinics, 83 (17.1%) had two providers, and 310 (64.1%) had three or more providers. Two hundred and twelve (43.8%) were located in rural regions and 44 (9.1%) were defined as FQHCs.

Table 1.

Sample Clinic Descriptive Characteristics (N=484)

| States [3-State Mean of Age-Adjusted Opioid Overdose Death Rate per 100,000 people] | N | % [95%CI] |

|---|---|---|

| High Rates of Overdose Death [33.2] | 148 | 30.6% CI[25.8–35.6%] |

| Massachusetts | 40 | 8.3% CI[4.5–12.3%] |

| Maryland | 52 | 10.7% CI[7.0–14.8%] |

| Ohio | 56 | 11.6% CI[7.9–15.6%] |

| Medium Rates of Overdose Death [21.5] | 158 | 32.7% CI[27.9–37.7%] |

| Michigan | 59 | 12.2% CI[8.5–16.2%] |

| New Jersey | 56 | 11.6% CI[7.9–15.6%] |

| Pennsylvania | 43 | 8.9% CI[5.2–12.9%] |

| Low Rates of Overdose Death [5.6] | 178 | 36.8% CI[32.0–41.8%] |

| California | 56 | 11.6% CI[7.9–15.6%] |

| Mississippi | 65 | 13.4% CI[9.7–17.5%] |

| Texas | 57 | 11.8% CI[8.1–15.8%] |

| Number of Providers (IQVIA) | μ=4.6 | CI[4.37–4.76] |

| 1 | 91 | 18.8% CI[14.5–23.4%] |

| 2 | 83 | 17.1% CI[12.8–21.7%] |

| 3–10 | 275 | 56.8% CI[52.5–61.4%] |

| More than 10 | 35 | 7.2% CI[2.9–11.8%] |

| Urban (population density +/− 1000) | ||

| Urban | 272 | 56.2% CI[51.7–60.8%] |

| Rural | 212 | 43.8% CI[39.3–48.4%] |

| FQHC Site (IQVIA) | ||

| Yes | 44 | 9.1% CI[6.8–11.7%] |

FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center.

Of the 452 clinics with paired call data, 146 (32.3%) responded that their PCPs would potentially prescribe opioids in both scenarios, 193 (42.7%) indicated they would not prescribe opioids in either scenario, and 113 (25.0%) gave different responses to each scenario (Figure 2). In these 113 clinics, respondents were almost twice as likely (73 clinics [64.6%] versus 40 clinics [35.4%]) to indicate that their PCPs might prescribe in scenario 1 (retired) but not prescribe in scenario 2 (stopped prescribing) than to give the opposite set of responses (OR=1.83 CI[1.23,2.76]) (Table 2).

Fig 2.

Opioid prescribing responses among primary care clinics reached for both scenarios (n=452). In scenario 1, the simulated patient said her previous doctor had retired. In scenario 2, she said her previous doctor had stopped prescribing her opioid medication.

Table 2.

Willingness to Prescribe and Accept Among Primary Care Clinics Responding to Both Scenarios (N=452)

| Prescribe Opioids | |||

| Scenario 2 (Stopped Prescribing) | |||

| Scenario 1 (Retired) | Yes | No | P value |

| Yes | 146 (32.3%) | 73 (16.2%) | |

| No | 40 (8.9%) | 193 (42.7%) | .002 |

| Accept for General Primary Care | |||

| Scenario 2 (Stopped Prescribing) | |||

| Scenario 1 (Retired) | Yes | No | P value |

| Yes | 393 (87.0%) | 21 (4.7%) | |

| No | 20 (4.4%) | 18 (4.0%) | .876 |

Of the 452 clinics with paired call data, 393 (87.0%) were willing to accept and schedule the patient for a general primary care visit in both scenarios, irrespective of their willingness to prescribe or not prescribe opioids. However, 18 (4.0%) said they were unwilling to schedule a primary care visit in both scenarios and 41 (9.1%) reported different responses to each scenario (Table 2). In 91.0% of all completed calls (n=936), clinics were willing to accept a patient for non-pain care once the RA stated they were on LTOT; however, the remaining 9.0% of clinics were unwilling to provide non-pain care despite having initially stated that they were accepting new patients.

After adjustment for other covariates related to clinic setting and individual characteristics, there were increased odds of potentially being prescribed opioids if the patient’s prior PCP retired (scenario 1) rather than if the prior PCP stopped prescribing opioids for the patient (scenario 2) (AOR=1.38 CI[1.13–1.69]) (Table 3). Differences in the odds of prescribing were also observed by state. As compared to clinics in Michigan, the reference state, California clinics had twice the odds of indicating potential willingness to prescribe opioids (AOR=2.01 CI[1.00–4.07]) while Mississippi clinics were less than half as likely (AOR=.41 CI[0.20–0.85]). Clinic-level attributes were also associated with prescribing, with larger clinics (AOR=1.08 per additional provider, CI[1.03–1.13]) and FQHCs (AOR=2.29 CI[1.28–4.10]) both more likely to be willing to prescribe opioids. There were also increased odds of a patient being accepted in larger (AOR=1.11 CI[1.00–1.23]) and urban clinics (AOR=2.61 CI[1.46–4.68]).

Table 3.

Adjusted Opioid Prescribing and Primary Care Acceptance Results for Clinics Responding to Both Scenarios (N=452)

| Criteria | Opioid Prescription (N=452) | General Primary Care Acceptance (N=452) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | OR | CI | |

| Scenario (ref cat = 2, stopped prescribing prompt) | ||||

| Scenario 1 (retired prompt) | 1.38 | 1.13–1.69 | 1.03 | 0.71–1.49 |

| State (ref cat = ‘MI’) | ||||

| High Rates of Overdose Death [33.2] | ||||

| MA | 1.08 | 0.52–2.24 | 0.90 | 0.29–2.81 |

| MD | 1.22 | 0.61–2.46 | 2.83 | 0.81–9.86 |

| OH | 0.84 | 0.42–1.65 | 1.76 | 0.59–5.27 |

| Medium Rates of Overdose Death [21.5] | ||||

| NJ | 1.37 | 0.71–2.63 | 1.33 | 0.46–3.88 |

| PA | 1.27 | 0.61–2.65 | 3.00 | 0.75–11.94 |

| Low Rates of Overdose Death [5.6] | ||||

| CA | 2.01 | 1.00–4.07 | 1.69 | 0.51–5.65 |

| MS | 0.41 | 0.20–0.85 | 1.68 | 0.63–4.48 |

| TX | 0.80 | 0.40–1.58 | 1.83 | 0.61–5.52 |

| Provider Count | 1.08 | 1.03–1.13 | 1.11 | 1.00–1.23 |

| Urbanicity (ref cat = ‘Rural’) | ||||

| Urban | 1.39 | 0.95–2.03 | 2.61 | 1.46–4.68 |

| FQHC Status (ref cat = ‘Not FQHC/ Unknown’) | ||||

| FQHC | 2.29 | 1.28–4.10 | 4.26 | 0.54–33.41 |

FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center.

Discussion

We conducted an audit study measuring primary care clinic willingness to accept and prescribe opioids for a patient on LTOT for pain in 9 states. We found over 40% of primary care clinics were unwilling to continue prescribing opioids to the simulated patients. A quarter of clinics provided different responses to the question of prescribing opioids when asked at different times and with different scenarios. For these clinics, willingness to potentially prescribe varied significantly by the reason the patient gave for seeking a new doctor. Specifically, a greater percentage of clinics were willing to prescribe if a patient said her prior PCP retired than if she said her prior PCP stopped prescribing opioids to her, with the latter scenario more open to the interpretation that the patient’s PCP discontinued prescribing due to aberrant opioid use.

Approximately 40% of clinics indicated an unwillingness to prescribe opioids at the initial point of contact. The inconsistency between clinics’ responses, as well as the unwillingness to prescribe overall, may suggest a need for a more unified approach to address the needs of patients who have long been taking opioids for chronic pain, especially amidst changing regulations and attitudes about opioids. It is understandable that PCPs might be reluctant to continue a prescribing regimen initiated by another PCP, particularly as new data suggest such treatment may be unlikely to produce clinical benefit and instead increases risk.[23] However, patients in this situation may experience withdrawal and other adverse outcomes when opioids are suddenly stopped.[29] This is also illustrated in the percentage of acceptance, where 9% of clinics clinic calls ended in an overall denial of care. These results are encouraging in some ways, as their complements suggest that over 60% of clinics indicated a willingness to prescribe opioids and over 90% of individuals on LTOT would be given a new patient appointment. Nonetheless, given that primary care is often where patients receive much of their care and serves as a gateway to specialty care, gatekeeping by clinic representatives may result in patients not receiving care at all.[33] These results suggest that some patients on long-term opioid therapy may experience barriers to care and that many primary care offices may benefit from further training in interactions with patients exhibiting potential problems related to substance use.

This study conducted an analysis across 9 states with variable overdose rates to examine whether states disproportionately affected by the opioid epidemic, with varying policies, would have different levels of primary care access for patients on LTOT. Prior researchers have hypothesized that physicians are less willing to prescribe opioids due to external policies, such as increased regulatory burden with Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) checks,[39] prior authorization forms, and clinic resources, which may vary between states.[20; 26] The increased regulatory burden of prescribing may provide a practical explanation for some PCPs’ unwillingness to consider prescribing for a patient already on LTOT. By calling each clinic twice, we aimed to hold state policies, clinic resources, and administrative burdens constant between the two scenarios. For 75% of clinics, willingness to prescribe opioids did not change between the two different calls. The remaining 25% of clinics provided different responses to each scenario, highlighting that opioid-related decision making is not solely dictated at the network or state policy level, but could be affected by stigma toward aberrant opioid use at the individual clinic level, as well as some degree of inconsistent clinic policies. These findings were not significantly different across states with high and low overdose rates, suggesting this stigma may be present regardless of the extent to which a given state has been impacted by opioid-related harms. We did find that states that had not expanded Medicaid (Mississippi and Texas) after the Affordable Care Act was passed were less willing to prescribe opioids. This might be a reflection of improved reimbursement with Medicaid expansion reducing provider reluctance to address the complex needs of patients on LTOT or other state-level socio-political factors, as a prior study in Michigan showed no difference in willingness to prescribe based upon whether a patient had private insurance versus Medicaid.[24] In addition to the underlying socio-political factors determining whether expansion took place, the ACA Medicaid expansion has itself been shown to have had substantial effects on a state’s healthcare industry.[18] It is conceivable that Medicaid associated factors, such as provider capacity, state economic changes, and care utilization, among others, could indirectly affect clinic decision-making around new patients.

This is one of the first studies to examine the extent to which the scenario (here, prior PCP retired versus stopped prescribing) that a patient provides when attempting to secure a new primary care appointment affects primary care clinics’ willingness to provide new patient appointments and potentially continue prescribing opioids. More clinics reported willingness to prescribe opioids in the scenario where the previous PCP retired than when the previous PCP stopped prescribing, demonstrating that clinics may be more willing to care for populations that portray themselves as having a non-addiction-related reason for needing a new PCP. The reasons behind this are likely multi-factorial. A clinic may hesitate to continue ongoing opioid prescribing if another physician denied it or the clinic staff may have an unconscious or conscious bias against those who they perceive as showing signs of aberrant use. However, when clinics attempt to distinguish between patients who use medication “as prescribed” and those who do not, it may further stigmatize those who have signs of aberrant use or addiction.[5; 7] Additionally, if a patient does have a more stigmatized reason for needing a new PCP (e.g. was discontinued by their prior PCP for aberrant use), it is potentially even more important for PCPs to intervene and link that patient to the appropriate treatment for both their chronic pain and addiction-related issues.

There are limitations to this study. We only assessed responses from clinic staff who are answering patient phone calls. Their responses may not be reflective of the responses we would receive from clinicians directly, especially if front-desk staff bear a larger proportion of the administrative burden of refill requests, prior authorization forms, and other details. However, the secret shopper method mirrors the patient experience of scheduling a new patient appointment and reduces social desirability biases commonly present when clinicians are surveyed directly.[6; 31] In addition, while our intent was to measure responses to a potentially stigmatizing situation, we cannot ascertain how this scenario was actually perceived by clinic staff. Other factors could be influencing clinic willingness to continue prescribing opioids for patients in some scenarios. There is a degree of randomness inherent to the specific responses captured in an audit study, and thus we were limited in our ability to ascertain the rationales or processes behind particular clinic decisions. Future qualitative work should further explore the clinic policies and staff decision-making processes that give rise to these decisions. The results were intended to reflect a patient’s initial point of clinical contact, which typically occurs over the telephone, and, as such, do not necessarily reflect the type or quality of care the patient may receive during an in-person clinic visit. In addition, our study only explored two patient scenarios on the phone, which may not be generalizable to all patients on opioids for chronic pain or to patients of all races, ages, or genders. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to states not included in the sample.

Denial of care or services is well-documented for commonly stigmatized disease states, such as HIV and substance use disorders.[27; 34; 35; 38] External factors related to administrative burdens, statewide policies, and treatment guidelines likely play a role in clinic decision-making and reduced primary care access for patients with chronic pain on opioid therapy. Additionally, internal clinic factors, including potential bias and stigma, likely further reduce access to care for patients with indications of possible aberrant use, as evinced by the variability in responses to patients with histories that were more or less suggestive of aberrancy. In almost a quarter of the clinics called, willingness to provide care varied based on the scenario presented, and was lower for patients with indications of possible aberrancy. To improve patient access to care and subsequent health outcomes, the underlying reasons for why clinic staff may be hesitant to provide care for individuals on opioid therapy will need to be addressed.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Figure that outlines the two scripts used to call clinics. pdf.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Giuliana Bresnahan, Danielle Helminski, and Avani Yaganti for their assistance with data collection. This research was funded by the Michigan Health Endowment Fund (grant # R-1808-143371) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant #1K23DA047475-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Market Share and Enrollment of Largest Three Insurers. Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation 2018(March 21, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- [2].What new opioid laws mean for pain relief. Harvard Health Letter. Boston, MA: Harvard Health Publishing, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Opioid Overdose Death Rates and All Drug Overdose Death Rates per 100,000 Population (Age-Adjusted). Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Agresti A. Categorial data analysis. New York: Wiley, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Antoniou T, Ala-Leppilampi K, Shearer D, Parsons JA, Tadrous M, Gomes T. “Like being put on an ice floe and shoved away”: A qualitative study of the impacts of opioid-related policy changes on people who take opioids. Int J Drug Policy 2019;66:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Asplin BR, Rhodes KV, Levy H, Lurie N, Crain AL, Carlin BP, Kellermann AL. Insurance status and access to urgent ambulatory care follow-up appointments. JAMA 2005;294(10):1248–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bell K, Salmon A. Pain, physical dependence and pseudoaddiction: redefining addiction for ‘nice’ people? Int J Drug Policy 2009;20(2):170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bohnert ASB, Guy GP Jr., Losby JL. Opioid Prescribing in the United States Before and After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 Opioid Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(6):367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, Saunders K, Ray GT, Sullivan MD, Campbell CI, Merrill JO, Silverberg MJ, Banta-Green C, Weisner C. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18(12):1166–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Comerci G Jr., Katzman J, Duhigg D. Controlling the Swing of the Opioid Pendulum. N Engl J Med 2018;378(8):691–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review 1989;96(4):608–630. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Darnall BD, Juurlink D, Kerns RD, Mackey S, Van Dorsten B, Humphreys K, Gonzalez-Sotomayor JA, Furlan A, Gordon AJ, Gordon DB, Hoffman DE, Katz J, Kertesz SG, Satel S, Lawhern RA, Nicholson KM, Polomano RC, Williamson OD, McAnally H, Kao MC, Schug S, Twillman R, Lewis TA, Stieg RL, Lorig K, Mallick-Searle T, West RW, Gray S, Ariens SR, Sharpe Potter J, Cowan P, Kollas CD, Laird D, Ingle B, Julian Grove J, Wilson M, Lockman K, Hodson F, Palackdharry CS, Fillingim RB, Fudin J, Barnhouse J, Manhapra A, Henson SR, Singer B, Ljosenvoor M, Griffith M, Doctor JN, Hardin K, London C, Mankowski J, Anderson A, Ellsworth L, Davis Budzinski L, Brandt B, Harkootley G, Nickels Heck D, Zobrosky MJ, Cheek C, Wilson M, Laux CE, Datz G, Dunaway J, Schonfeld E, Cady M, LeDantec-Boswell T, Craigie M, Sturgeon J, Flood P, Giummarra M, Whelan J, Thorn BE, Martin RL, Schatman ME, Gregory MD, Kirz J, Robinson P, Marx JG, Stewart JR, Keck PS, Hadland SE, Murphy JL, Lumley MA, Brown KS, Leong MS, Fillman M, Broatch JW, Perez A, Watford K, Kruska K, Sophia You D, Ogbeide S, Kukucka A, Lawson S, Ray JB, Wade Martin T, Lakehomer JB, Burke A, Cohen RI, Grinspoon P, Rubenstein MS, Sutherland S, Walters KR, Lovejoy T. International Stakeholder Community of Pain Experts and Leaders Call for an Urgent Action on Forced Opioid Tapering. Pain Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Davis CS, Lieberman AJ, Hernandez-Delgado H, Suba C. Laws limiting the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain in the United States: A national systematic legal review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;194:166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].De Ruddere L, Craig KD. Understanding stigma and chronic pain: a-state-of-the-art review. Pain 2016;157(8):1607–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dowell D, Tamara M.Chou, Roger. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 2016;315(15):1624–1645 1622p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Driscoll MA, Knobf MT, Higgins DM, Heapy A, Lee A, Haskell S. Patient experiences navigating chronic pain management in an integrated health care system: A qualitative investigation of women and men. Pain Med 2018;19(1):S19–S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fenton JJ, Agnoli AL, Xing G, Hang L, Altan AE, Tancredi DJ, Jerant A, Magnan E. Trends and Rapidity of Dose Tapering Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioid Therapy, 2008–2017. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(11):e1916271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Guth M, Garfield R, Rudowitz R. The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020.

- [19].Guy GP Jr., Zhang K. Opioid Prescribing by Specialty and Volume in the U.S. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 2018;55(5):153–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Haffajee RL, Mello MM, Zhang F, Zaslavsky AM, Larochelle MR, Wharam JF. Four States With Robust Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs Reduced Opioid Dosages. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(6):964–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hurstak EE, Kushel M, Chang J, Ceasar R, Zamora K, Miaskowski C, Knight K. The risks of opioid treatment: Perspectives of primary care practictioners and patients from safety-net clinics. Substance Abuse 2017;38(2):213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kertesz SG, Gordon AJ. A crisis of opioids and the limits of prescription control: United States. Addiction 2019;114(1):169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, Jensen AC, DeRonne B, Goldsmith ES, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Noorbaloochi S. Effect of Opioid vs Nonopioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain: The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018;319(9):872–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lagisetty PA, Healy N, Garpestad C, Jannausch M, Tipirneni R, Bohnert ASB. Access to Primary Care Clinics for Patients With Chronic Pain Receiving Opioids. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(7):e196928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Legislatures NCoS. Prescribing Policies: States Confront Opioid Overdose Epidemic. 2019.

- [26].Mauri AI, Townsend TN, Haffajee RL. The Association of State Opioid Misuse Prevention Policies With Patient- and Provider-Related Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Milbank Q 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McCradden MD, Vasileva D, Orchanian-Cheff A, Buchman DZ. Ambiguous identities of drugs and people: A scoping review of opioid-related stigma. Int J Drug Policy 2019;74:205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 1947;12:153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Oliva EM, Bowe T, Manhapra A, Kertesz SG, Hah JM, Henderson P, Robinson A, Paik M, Sandbrink F, Gordon AJ, Trafton JA. Associations between stopping prescriptions for opioids, length of opioid treatment, and overdose or suicide deaths in US veterans: observational evaluation. BMJ 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, Fields A. Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau: American Community Survey and Geography Brief. US Census Bureau 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rhodes K. Taking the mystery out of “mystery shopper” studies. N Engl J Med 2011;365(6):484–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rothstein MA. The Opioid Crisis and the Need for Compassion in Pain Management. Am J Public Health 2017;107(8):1253–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schottenfield JR, Waldman SA, Gluck AR, Tobin DG. Pain and Addiction in Specialty and Primary Care: The Bookends of a Crisis. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 2018;46:220–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sears B. HIV Discrimination in Health Care Services in Los Angeles County: The Results of Three Testing Studies. Wash Lee J Civ Rts Soc Just 2008;15(1):85–107. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sohler N, Li X, Cunningham C. Perceived discrimination among severely disadvantaged people with HIV infection. Public Health Rep 2007;122(3):347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vallerand A, Nowak L. Chronic opioid therapy for nonmalignant pain: The patient’s perspective. Part II-barriers to chronic opioid therapy. Pain Manag Nurse 2010;11(2):126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain--Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies. N Engl J Med 2016;374(13):1253–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wakeman SE, Rich JD. Barriers to Post-Acute Care for Patients on Opioid Agonist Therapy; An Example of Systematic Stigmatization of Addiction. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32(1):17–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Winstanley EL, Zhang Y, Mashni R, Schnee S, Penm J, Boone J, McNamee C, MacKinnon NJ. Mandatory review of a prescription drug monitoring program and impact on opioid and benzodiazepine dispensing. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;188:169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Figure that outlines the two scripts used to call clinics. pdf.