Abstract

Metabolite profile provides an overview and avenue for the detection of a vast number of metabolites in food sample at a particular time. Gas chromatography high resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-HRTOF-MS) is one of such techniques that can be utilized for profiling known and unknown compounds in a food sample. In this study, the metabolite profiles of Bambara groundnut and dawadawa (unhulled and dehulled) were investigated using GC-HRTOF-MS. The presence of varying groups of metabolites, including aldehydes, sterols, ketones, alcohols, nitrogen-containing compounds, furans, pyridines, acids, vitamins, fatty acids, sulphur-related compounds, esters, terpenes and terpenoids were reported. Bambara groundnut fermented into derived dawadawa products induced either an increase or decrease as well as the formation of some metabolites. The major compounds (with their peak area percentages) identified in Bambara groundnut were furfuryl ether (9.31%), bis (2-(dimethylamino)ethyl) ether (7.95%), 2-monopalmitin (7.88%), hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester (6.98%), 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z) and 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester (5.82%). For dehulled dawadawa, the significant compounds were palmitic acid, ethyl ester (17.7%), lauric acid, ethyl ester (10.2%), carbonic acid, 2-dimethylaminoethyl 2-methoxyethyl ester (7.3%), 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester (5.13%) and maltol (4%), while for undehulled dawadawa, it was indoline, 2-(hydroxydiphenylmethyl) (26.1%), benzoic acid, 4-amino-4-hydroximino-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyl ester (8.2%), 2-undecen-4-ol (4.7%), 2-methylbutyl propanoate (4.7%) and ë-tocopherol (4.3%). These observed metabolites reported herein provides an overview of the metabolites in these investigated foods, some of which could be related to nutrition, bioactivity as well as sensory properties. It is important to emphasize that based on some of the metabolites detected, it could be suggested that Bambara groundnut and derived dawadawa might serve as functional foods that are beneficial to health.

Keywords: Fermented condiment, GC-HRTOF-MS, Legume, Metabolites, Profiling

Fermented condiment; GC-HRTOF-MS; Legume; Metabolites; Profiling.

1. Introduction

Fermentation is a biochemical process that results in modifications (increase/decrease) as well as formation (synthesis) of metabolites. These metabolites contribute to the nutritional qualities, taste, shelf life, safety, aroma, health promoting properties and overall composition of fermented foods. Traditionally, these fermented foods are produced from legumes or cereals and undergo various forms of fermentation, such as alkali fermentation, lactic acid fermentation, acetic acid fermentation and alcoholic fermentation (Oliveira et al., 2014). The fermentation process whereby the pH of a legume increases to alkaline levels and possibly pH values of 9 and above is known as alkaline fermentation (Omafuvbe et al., 2002) and such is due to breakdown of proteins to ammonia, peptides and amino acids (Wang and Fung, 1996; Kiers et al., 2000).

In African and Asian countries, several alkaline fermented food condiments, such as dawadawa, thua-nao, iru, natto and soumbala, are mostly produced from legumes and from Bambara groundnut (Fadahunsi and Olubunmi, 2009; Parkouda et al., 2009; Ademiluyi and Oboh, 2011; Akanni et al., 2018a; Muhammad et al., 2018). These fermented condiments are processed mostly through natural fermentation; however, this is not always the case, as some undergo controlled fermentation. During the production of dawadawa, raw legume seeds are soaked, manually dehulled and boiled to soften the seeds. The boiled softened raw seeds are wrapped with leaves (such as banana leaves), kept in sacks or bags and incubated in a plastic bowl/calabash/earthen pot for three to five days (the fermentation period is usually based on human discretion) (Onawola et al., 2012). The most important and major processing step for this product is fermentation and has been proven to enhance the organoleptic and beneficial health properties of fermented legumes (Oboh et al., 2009; Ademiluyi and Oboh, 2011; Chinma et al., 2020).

Monitoring of these metabolic, biochemical, physicochemical and structural changes occurring during the fermentation process may be somewhat difficult, necessitating the utilization of techniques and robust equipment, which can provide a better overview of these metabolites. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry is a non-biased, comprehensive and sensitive technological system used for the detection of diverse volatile and semi-volatile metabolites (Adebo et al., 2021). It has advantages of better resolution, high sensitivity, good reproducibility and, with the necessary databases, makes identification of compounds relatively easier (Hu et al., 2018). Particularly for gas chromatography coupled with high-resolution time of flight mass spectrometry, it is a powerful and highly effective analytical tool with excellent capabilities including a better chromatographic separating capability over a wide mass range with an accurate mass measurement (Brits et al., 2018; Kewuyemi et al., 2020). The exact mass information and mass resolution provided by high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HR-TOFMS) can enhance target identification of compound and also assist in the identification of unknown compounds (Ubukata et al., 2015).

While few authors have studied the composition of dawadawa (Akanni et al., 2018a; Onyenekwe et al., 2012; Adebiyi et al., 2019), there is still no study providing a comparison of the metabolite profile of two types of dawadawa (dehulled and unhulled) from Bambara groundnut (BGN) obtained through natural fermentation. Thus, this study was aimed to profile metabolites in BGN and dawadawa (dehulled and unhulled) using GC-HRTOF-MS, envisaging that the metabolites would be beneficial to consumers of these products.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Raw materials and sample preparation

Bambara groundnuts (mixed varieties) (i.e. brown, cream and red) used in this study were procured from a local farmer in Limpopo Province, South Africa. These were subsequently sorted to remove extraneous material or debris and cleaned with water.

2.2. Fermentation of Bambara groundnut into dawadawa

The production of both dehulled and unhulled dawadawa has been previously described in our earlier study Adebiyi et al. (2019). Briefly, the BGN was soaked for 24 h in water and dehulled manually, the dehulled raw seeds were rinsed with water and boiled for 1 h. Later, the boiled and cooled BGN seeds were spread and covered with a sterile banana leaves, wrapped in jute bags and incubated at 35 °C for 84 h. For the unhulled dawadawa (UHD), the hulls or seed coats were not removed after soaking and were incubated at 35 °C for 120 h. The fermentation time and temperature conditions (35 °C for 84 h and 35 °C for 120 h, for DD and UHD, respectively) that were used for producing the dawadawa samples was guided by the optimized results earlier achieved and reported in Adebiyi et al. (2020). The samples were freeze-dried at −55 °C for 24 h (LyoQuest Telstar Technologies, Spain) and stored at 4 °C prior to analysis.

2.3. Sample preparation for metabolite profiling

At the initial stage of sample preparation, different extraction solvents (all analytical grade) [100% acetonitrile (ACN), 100% methanol (MeOH), 100% water (H2O), 80% ACN in H2O, 80% MeOH in H2O, 50% ACN:MeOH (v/v), 1% HCl in MeOH, ACN:MeOH:H2O (4,4,2, v/v/v) and isopropanol:ACN:H2O (4,4,2, v/v/v)] were used to investigate for a possible range of available metabolites in the samples.

An informed compromise was reached and extraction using 80% MeOH in H2O was finally adopted based on a wider range of relevant metabolites detected on the GC-HRTOF-MS system. Briefly, 10 mL of 80% MeOH was added to 1 g of freeze-dried sample, agitated and the mixture sonicated in an ultrasonic bath (Integral Systems Ultrasonic Bath UMC 5, Labotec, South Africa) at 4 °C for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged at 3 500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C (Eppendorf 5702R, Merck South Africa), transferred into a 250 mL round bottom flask and concentrated at 30 °C, under pressure using a rotary evaporator (Buchi, Switzerland). The extract was reconstituted with 1 mL chromatographic grade MeOH (Sigma Aldrich, Germany) and filtered into a dark amber vial for analysis. The extraction was done in triplicates for each sample.

2.4. GC-HRTOF-MS analysis

A mass calibration of the instrument was performed prior to analysis on the LECO Pegasus GC-HRTOF-MS system (LECO Corporation, St Joseph, MI, USA) and subsequent sample analyses done using the method of Adebo et al. (2019). The samples were then analyzed on the GC-HRTOF-MS system equipped with an Agilent 7890A (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) gas chromatograph running in a high-resolution. This was coupled to a Gerstel MPS multipurpose autosampler (Gerstel Inc. Germany) and analytical column was a Rxi®-5ms (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm) (Restek, Bellefonte, USA). One microlitre (μL) of each sample was injected (in a splitless mode) with helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate (1 mL/min). The transfer line and inlet temperatures were 225 °C and 250 °C respectively. The oven temperature was initially set at 70 °C, held for 0.5 min, ramped at 10 °C/min to 150 °C and held for 2 min. The oven temperature was later ramped at 10 °C/min to 330 °C and held for 3 min Triplicate extraction for each sample were respectively injected once into the GC-HR-TOF-MS equipment as well as solvent blanks to observe impurities and possible contamination.

2.5. Data analysis

From the data obtained, peak picking, retention time alignment, peak matching and detection were done on the ChromaTOF-HRT® software (LECO Corporation, St Joseph, MI, USA). Other data processing parameters adopted included a signal to noise ratio of 100 and a minimum match similarity of >70% prior to when compound name is assigned, using the Mainlib, Feihn and NIST metabolomics database by comparing the molecular formula, retention time and mass spectra data. Percentage peak areas were subsequently calculated, and the respective observed m/z fragments obtained from the ChromaTOF-HRT® data station were recorded after which the metabolite class was annotated with corresponding m/z fragments and molecular formula.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Metabolites of Bambara groundnut and dawadawa profiled using GC-HRTOF-MS

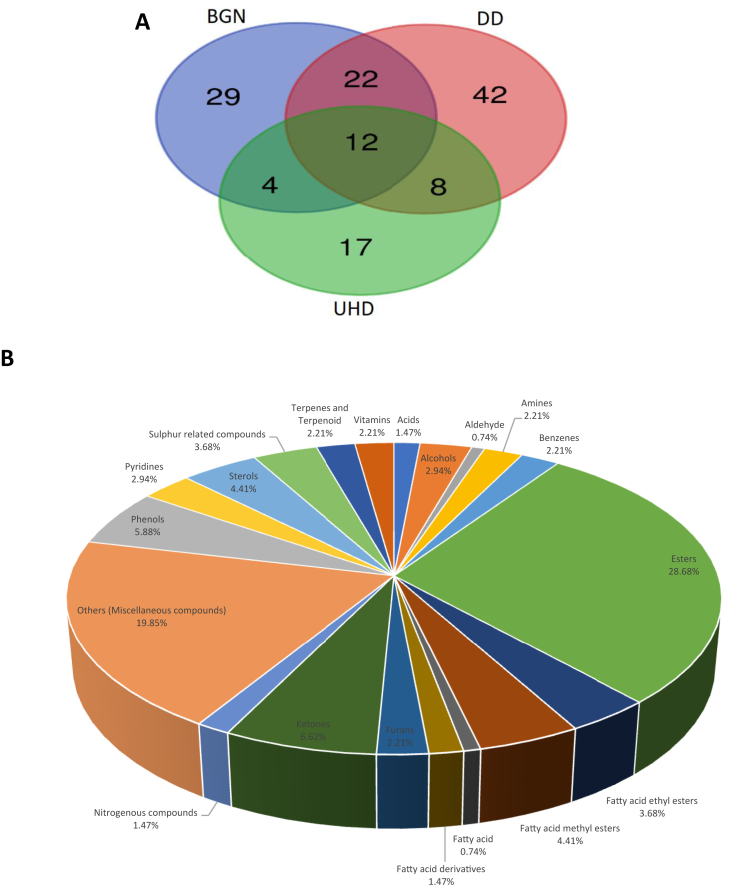

The metabolic compounds of BGN and the two dawadawa produced (unhulled and dehulled) were analyzed using GC-HRTOF-MS. This is the first report to the best of our knowledge to profile and investigate the metabolites of BGN, unhulled (UHD) and dehulled (DD) dawadawa using GC-HRTOF-MS. In total, 134 metabolites were identified, and their identities presented in Table 1. Figure 1 represents the GC-HRTOF-MS chromatogram of BGN, DD and UHD samples. The group of compounds detected were terpenes and terpenoids (2%), amines (2%), sulphur related compounds (4%), ketones (7%), pyridines (3%), vitamins (2%), esters including fatty acid methyl and ethyl esters (37%), alcohols including sterols (7%), phenols (6%) and other miscellaneous compounds (20%). Eight compounds were identified in both dawadawa products, 29 in BGN, 42 in only DD, 17 in only UHD and 12 in all the samples analyzed (Figure 2A). Generally, more metabolites were detected in DD samples as compared to UHD, which might be attributed to increased microbial activity enhancing metabolic activities and better breakdown and/or formation of compounds. This was also the observation in an earlier study (Adebiyi et al., 2019; Adebiyi, 2020) and can be related to higher antioxidant activities and antinutritional factors (ANFs) in UHD as compared to DD samples, which might influence microbial activities. Some of the compounds identified in Table 1, were not detected in the raw BGN, but observed in DD and UHD samples. It can thus be speculated that these compounds were presumably produced during fermentation. The major metabolites that were only found in the fermented condiments include 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester (5.13%), carbonic acid, 2-dimethylaminoethyl 2-methoxyethyl ester (7.3%), lauric acid, ethyl ester (10.2%), maltol (4%) and palmitic acid, ethyl ester (17.7%) for dehulled dawadawa and 2-methylbutyl propanoate (4.7%), 2-undecen-4-ol (4.7%), benzoic acid,4-amino-4-hydroximino-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyl ester (8.2%), ë-tocopherol (4.3%) and indoline, 2-(hydroxydiphenylmethyl)- (26.1%) for unhulled dawadawa samples (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolites identified in Bambara groundnut and dawadawa (dehulled and unhulled) samples.

| tR (min) | Compound name and metabolite class | Observed m/z | m/z fragments | MF | Percentage peak areas |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGN | DD | UHD | |||||

|

Acids |

|||||||

| 04:47 | 6-Methylbicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-ene-5-carboxylic acid | 122.4808 | 65.9583, 105.1135 | C9H12O2 | ND | ND | 4.69 |

| 06:27 |

1-Hydroxycyclohexanecarboxylic acid |

131.6358 |

68.0502, 98.9424 |

C7H12O3 |

ND |

ND |

3.46 |

|

Alcohols |

|||||||

| 05:03 | 2-undecen-4-ol | 192.9805 | 71.0490, 131.0703 | C11H22O | ND | 1.98 | 4.70 |

| 06:02 | Maltol | 126.0312 | 55.0180, 71.0128 | C6H6O3 | 4.85 | 4.00 | ND |

| 06:03 | Phenylethyl alcohol | 122.0728 | 91.0544, 122.0728 | C8H10O | ND | 1.36 | ND |

| 17:00 |

1-Hexadecanol |

196.2187 |

55.0544, 83.0856 |

C16H34O |

0.10 |

ND |

ND |

|

Aldehyde |

|||||||

| 08:11 |

à-Ethylidenebenzeneacetaldehyde |

146.0728 |

115.0544, 138.0913 |

C10H10O |

ND |

0.06 |

ND |

|

Amines |

|||||||

| 14:13 | 1-Naphthalenamine, N-ethyl- | 171.1045 | 129.0702, 156.0810 | C12H13N | ND | 0.12 | ND |

| 12:12 | N-acetylphenethylamine | 163.0994 | 30.0342, 104.0623 | C10H13NO | ND | 0.62 | ND |

| 13:20 |

p-Aminobiphenyl |

169.0888 |

141.0700, 167.0733 |

C12H11N |

ND |

0.12 |

ND |

|

Benzenes |

|||||||

| 07:53 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 190.1711 | 124.0756, 175.1482 | C14H22 | ND | 0.04 | ND |

| 10:13 | Benzeneethanol, à-(phenylmethyl)- | 208.2062 | 92.0622, 103.0544 | C15H16O | ND | 0.49 | ND |

| 24:55 |

Benzeneethanamine, 2-fluoro-á,3,4-trihydroxy-N-isopropyl- |

226.2167 |

59.0367, 72.0445 |

C11H16FNO3 |

0.66 |

0.21 |

ND |

|

Esters |

|||||||

| 03:55 | Benzoic acid, 4-amino-, 4-hydroximino-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyl ester | 120.4566 | 80.4620, 83.5630 | C16H23N3O3 | ND | ND | 8.23 |

| 06:56 | Benzofenac methyl ester | 174.1069 | 61.0106, 91.0211 | C16H15ClO3 | 0.05 | ND | ND |

| 07:08 | Benzoic acid, 4-amino-, 4-acetoxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyl ester | 153.0501 | 107.1252, 120.4566 | C18H26N2O4 | 0.17 | ND | 1.23 |

| 08:27 | Cyclobutanecarboxylic acid, 2-dimethylaminoethyl ester | 151.1098 | 58.0653, 71.0730 | C9H17NO2 | ND | 0.38 | ND |

| 09:18 | Propanoic acid, 2-methyl-, 2,2-dimethyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-1,3-propanediyl ester | 329.0325 | 43.0543, 71.0492 | C16H30O4 | 0.34 | 0.25 | ND |

| 09:37 | Propanoic acid, 2-methyl-, 3-hydroxy-2,2,4-trimethylpentyl ester | 174.1206 | 71.0492, 89.0598 | C12H24O3 | 0.33 | ND | ND |

| 10:19 | Fumaric acid, ethyl 2,3,5-trichlorophenyl ester | 167.1065 | 99.0442, 127.0390 | C12H9Cl3O4 | 0.07 | ND | 0.57 |

| 10:34 | Fumaric acid, monoamide, N,N-dimethyl-, 3-chlorophenyl ester | 185.0676 | 98.0602, 126.0552 | C12H12ClNO3 | ND | 0.16 | ND |

| 11:04 | Phthalic acid, 3,4-dichlorophenyl methyl ester | 194.0571 | 77.0386, 163.0392 | C15H10Cl2O4 | 0.22 | ND | ND |

| 11:04 | Phthalic acid, methyl 4-(2-phenylprop-2-yl)phenyl ester | 283.0486 | 103.0139, 163.0307 | C24H22O4 | ND | 0.10 | 0.33 |

| 11:08 | 4-Butylbenzoic acid, 2-dimethylaminoethyl ester | 161.1200 | 58.0653, 71.0731 | C15H23NO2 | ND | 0.19 | ND |

| 12:02 | 3,4-Dimethyl-2-(3-methyl-butyryl)-benzoic acid, methyl ester | 208.5497 | 54.5083, 191.4042 | C15H20O3 | ND | ND | 3.42 |

| 12:33 | Ethyl 2-cyano-3-methylbutanoate | 153.9684 | 68.0387, 82.5285 | C8H13NO2 | 0.10 | ND | 0.61 |

| 12:57 | 6-Methoxythymyl 2-methylbutyrate | 180.2455 | 121.4904, 165.0691 | C16H24O3 | ND | ND | 0.42 |

| 13:23 | Phthalic acid, monoamide, N-ethyl-N-(3-methylphenyl)-, ethyl ester | 194.0570 | 149.0235, 177.0545 | C19H21NO3 | 0.04 | ND | ND |

| 13:25 | Butyric acid, thio-, S-hexyl ester | 194.1546 | 73.0543, 71.0492 | C10H20OS | ND | 0.23 | ND |

| 15:42 | Fumaric acid, butyl 2-phenylethyl ester | 267.9997 | 104.0623, 203.0943 | C16H20O4 | ND | 0.33 | ND |

| 16:43 | Ethyl 13-methyl-tetradecanoate | 270.2554 | 88.0520, 101.0599 | C17H34O2 | ND | 0.17 | ND |

| 16:56 | Phthalic acid, heptyl tridec-2-yn-1-yl ester | 460.9532 | 57.0701, 149.0236 | C28H42O4 | 0.42 | ND | ND |

| 17:45 | Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxy-, methyl ester | 292.2035 | 147.0808, 277.1799 | C18H28O3 | 0.02 | ND | ND |

| 17:55 | DL-Alanine, N-methyl-N-(byt-3-yn-1-yloxycarbonyl)-, tridecyl ester | 224.1825 | 86.0966, 154.0738 | C22H39NO4 | ND | 1.67 | ND |

| 17:57 | Phthalic acid, 8-chlorooctyl nonyl ester | 236.2140 | 148.8379, 205.4445 | C25H39ClO4 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 0.30 |

| 17:57 | Phthalic acid, 2-chloropropyl heptyl ester | 224.0991 | 149.0235, 205.0860 | C18H25ClO4 | 0.53 | ND | 0.28 |

| 17:58 | Phthalic acid, 8-chlorooctyl decyl ester | 224.1005 | 103.0392, 149.0235 | C26H41ClO4 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.60 |

| 18:20 | Fumaric acid, 2,6-dimethoxyphenyl dodec-2-en-1-yl ester | 213.1026 | 68.0386, 153.9559 | C24H34O6 | ND | 1.10 | 2.60 |

| 18:30 | L-Proline, N-valeryl-, decyl ester | 219.0079 | 55.1733, 84.0285 | C20H37NO3 | ND | 0.86 | ND |

| 20:10 | 2-Methylbutyl propanoate | 142.8595 | 56.5643, 70.0906 | C8H16O2 | ND | ND | 4.68 |

| 21:00 | Octanoic acid, 2-dimethylaminoethyl ester | 218.0598 | 58.0652, 72.0808 | C12H25NO2 | 2.48 | 1.98 | ND |

| 22:28 | Carbonic acid, 2-dimethylaminoethyl 2-methoxyethyl ester | 194.1912 | 58.0652, 71.0729 | C8H17NO4 | 4.65 | 7.33 | ND |

| 23:11 | Phthalic acid, dicyclohexyl ester | 300.2082 | 149.0236, 167.0342 | C20H26O4 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.82 |

| 24:06 | Isophthalic acid, phenylethyl undecyl ester | 267.0185 | 104.0825, 131.6355 | C27H36O4 | ND | 0.02 | 0.46 |

| 24:19 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester | 348.0901 | 67.0543, 262.2299 | C21H38O4 | 5.82 | 5.14 | ND |

| 24:29 | Octadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester | 359.3167 | 74.0362, 98.0728 | C21H42O4 | 2.32 | ND | ND |

| 25:30 | Butylphosphonic acid, decyl 4-(2-phenylprop-2-yl)phenyl ester | 472.3099 | 221.1319, 457.2876 | C29H45O3P | 0.06 | ND | ND |

| 25:30 | Succinic acid, 2-chloro-6-fluorophenyl phenethyl ester | 400.9841 | 105.0699, 279.2308 | C18H16ClFO4 | ND | 0.32 | ND |

| 25:37 | Succinic acid, 3,4-dimethylphenyl 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl ester | 312.3026 | 58.0135, 71.7611 | C16H23NO4 | 0.37 | 0.16 | ND |

| 25:37 | Carbonic acid, 2-dimethylaminoethyl isobutyl ester | 186.1471 | 58.0652, 71.0729 | C9H19NO3 | 0.21 | 0.27 | ND |

| 29:25 | Urs-12-en-24-oic acid, 3-oxo-, methyl ester, (+)- | 427.3893 | 189.1643, 218.2032 | C31H48O3 | 0.14 | ND | ND |

| 30:39 |

Olean-12-en-28-oic acid, 3-oxo-, methyl ester |

452.3664 |

203.1796, 262.1931 |

C31H48O3 |

0.74 |

ND |

ND |

|

Fatty acid ethyl esters |

|||||||

| 17:08 | Pentadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | 270.2552 | 88.0520, 101.0599 | C17H34O2 | ND | 0.25 | ND |

| 18:00 | 9-hexadecenoic acid, ethyl ester | 282.2556 | 69.0699, 88.0521 | C18H34O2 | ND | 0.26 | ND |

| 18:14 | Lauric acid, ethyl ester | 228.2055 | 88.0521, 101.0600 | C14H28O2 | ND | 10.15 | ND |

| 18:19 | Palmitic acid, ethyl ester | 285.2786 | 88.0522, 101.0601 | C18H36O2 | ND | 17.74 | ND |

| 23:29 |

Stearic acid, ethyl ester |

312.2990 |

88.0520, 101.0599 |

C20H40O2 |

ND |

1.41 |

ND |

|

Fatty acid methyl esters |

|||||||

| 15:59 | Myristic acid, methyl ester | 256.2399 | 88.0521, 101.0600 | C16H32O2 | ND | 0.75 | ND |

| 17:30 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 270.2556 | 74.0363, 87.0442 | C17H34O2 | 6.98 | ND | ND |

| 19:15 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester | 294.2561 | 81.0699, 95.0858 | C19H34O2 | 2.55 | ND | ND |

| 19:19 | trans-13-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | 296.2714 | 55.0543, 74.0363 | C19H36O2 | 0.73 | ND | ND |

| 19:31 | Octadecanoic acid methyl ester | 298.2871 | 74.0363, 143.1070 | C19H38O2 | 1.61 | ND | ND |

| 23:00 |

Cerotic acid, methyl ester |

356.3559 |

74.0363, 87.0442 |

C27H54O2 |

ND |

1.41 |

ND |

|

Fatty acid |

|||||||

| 18:05 |

Palmitic acid |

256.2404 |

60.0207, 73.0284 |

C16H32O2 |

4.03 |

ND |

ND |

|

Fatty acid derivatives |

|||||||

| 20:29 | Myristic acid amide | 227.2204 | 59.0367, 72.0445 | C14H29NO | ND | 1.04 | ND |

| 22:55 |

2-monopalmitin |

331.2852 |

104.0738, 128.5062 |

C19H38O4 |

7.88 |

3.65 |

ND |

|

Furans |

|||||||

| 03:35 | Furanoeudesma-1,4-diene | 108.0683 | 47.0327, 64.0181 | C15H18O | ND | 1.50 | ND |

| 07:46 | 3-Butene-1,2-diol, 1-(2-furanyl)- | 128.0357 | 49.0073, 97.0286 | C8H10O3 | 2.39 | 1.90 | 0.32 |

| 19:45 |

Furfuryl ether |

176.0922 |

81.0335, 143.0342 |

C10H10O3 |

9.31 |

ND |

ND |

|

Ketones |

|||||||

| 04:09 | Hex-4-yn-3-one | 95.8902 | 67.0060, 68.0471 | C6H8O | ND | ND | 1.02 |

| 06:02 | 3-Acetoxy-2-methyl-pyran-4-one | 129.0913 | 71.0128, 126.0312 | C8H8O4 | 3.57 | 3.67 | ND |

| 07:41 | 2-Coumaranone | 134.0364 | 78.0464, 106.0414 | C8H6O2 | ND | 0.12 | ND |

| 08:44 | Ethanone, 1-(2-hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)- | 150.0677 | 107.0493, 135.0442 | C9H10O2 | 0.44 | 0.30 | ND |

| 09:47 | 7-Chloro-1,3,4,10-tetrahydro-10-hydroxy-1-[[2-[1-pyrrolidinyl]ethyl]imino]-3-[3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-9(2H)-acridinone | 268.9973 | 84.0809, 132.0548 | C26H25ClF3N3O2 | 0.91 | 0.15 | 3.75 |

| 11:04 | 2-(6-Chloro-3-nitro-4-phenyl-quinolin-2-ylsulfanyl)-1-(2,3-dihydro-benzo[1,4]dioxin-6-yl)- ethanone | 194.0574 | 132.5996, 163.0307 | C25H17ClN2O5S | ND | 0.12 | 0.36 |

| 17:32 | 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione | 276.1718 | 175.119, 205.0861 | C17H24O3 | 0.11 | ND | ND |

| 23:20 | 2-methoxy-,2-octen-4-one, | 152.0474 | 99.0443, 114.0677 | C9H16O2 | 0.19 | 0.08 | ND |

| 28:04 |

3,6,13,16-tetraoxatricyclo[16.2.2.2(8,11)]tetracosa-8,10,18,20,21,23-hexaene-2,7,12,17-tetrone |

380.0489 |

208.0519, 341.0657 |

C20H16O8 |

0.08 |

ND |

ND |

|

Nitrogenous compounds |

|||||||

| 04:48 | Indoline, 2-(hydroxydiphenylmethyl)- | 314.5135 | 103.0505, 118.4013 | C21H19NO | ND | ND | 26.11 |

| 07:34 |

Indole, 3-(2-(diethylamino)ethyl)- |

130.6049 |

85.5811, 129.5840 |

C14H20N2 |

ND |

ND |

0.16 |

|

Others (Miscellaneous compounds) |

|||||||

| 03:45 | N-[3,3′-dimethoxy-4'-(2-piperidin-1-yl-acetylamino)-biphenyl-4-yl]-2-piperidin-1- yl-acetamide | 128.0471 | 93.0701, 98.0364 | C28H38N4O4 | 0.55 | 5.14 | ND |

| 05:50 | Succinic anhydride | 102.0283 | 36.5607, 55.5498 | C4H4O3 | ND | ND | 6.71 |

| 06:22 | Decamethylcyclopentasiloxane | 358.0680 | 73.0469, 266.9992 | C10H30O5Si5 | 0.12 | 0.05 | ND |

| 06:27 | N,N-Dimethylglycine | 103.0631 | 42.0338, 58.0653 | C4H9NO2 | ND | 0.62 | ND |

| 06:39 | 1H-Imidazole-4-methanol | 98.0364 | 69.0335, 97.0286 | C4H6N2O | ND | 2.31 | ND |

| 06:52 | Thiourea, N-(3-methyl-2-pyridinyl)-N'-[(tetrahydro-2-furanyl)methyl]- | 332.0663 | 44.0733, 150.0677 | C12H17N3OS | ND | 0.12 | ND |

| 07:32 | Catecholborane | 120.0570 | 100.0759, 148.0994 | C6H5BO2 | ND | 0.71 | ND |

| 07:42 | 2-Benzoxazolamine, N-(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 153.9813 | 105.0764, 133.6238 | C11H14N2O | ND | ND | 0.32 |

| 08:43 | Dodecamethylcyclohexasiloxane | 434.0840 | 73.0468, 341.0179 | C12H36O6Si6 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 1.69 |

| 08:44 | Phenyl-1,2-diamine, N,4,5-trimethyl- | 149.8967 | 106.1084, 134.6487 | C9H14N2 | ND | ND | 0.36 |

| 09:53 | Benzaldehyde, 3-methoxy-4-[(2-methylphenyl)methoxy]- | 195.1248 | 105.0701, 132.0810 | C16H16O3 | ND | 1.00 | ND |

| 11:15 | 4,4′-Dichlorodibutyl ether | 158.0202 | 91.0312, 93.0280 | C8H16Cl2O | 0.03 | ND | ND |

| 11:40 | Tetradecamethylcycloheptasiloxane | 508.1064 | 73.0467, 281.0513 | C14H42O7Si7 | 2.04 | 1.72 | ND |

| 11:50 | Tetradonium Bromide | 165.0703 | 58.0653 | C17H38BrN | 0.13 | ND | ND |

| 12:58 | 2,3,5,6-Tetrafluoroanisole | 180.0782 | 137.0569, 165.0548 | C7H4F4O | ND | 0.23 | ND |

| 13:14 | 3-Methyl-4-phenyl-1H-pyrrole | 157.0886 | 127.5468, 155.9884 | C11H11N | ND | 1.19 | 1.12 |

| 13:24 | 2-propynenitrile, 3-fluoro- | 69.0591 | 53.4495, 81.5012 | C3FN | ND | ND | 1.05 |

| 14:20 | Hexadecamethyl-cyclooctasiloxane | 580.1260 | 73.0468, 355.0702 | C16H48O8Si8 | 1.71 | 1.41 | 1.53 |

| 17:09 | 2,7-Dimethylcarbazole | 195.1039 | 140.0702, 167.0726 | C14H13N | ND | 0.03 | ND |

| 17:50 | 1-Methyl-2,5-dipropyldecahydroquinoline | 195.4010 | 86.6185, 166.1360 | C16H31N | ND | ND | 0.15 |

| 19:41 | 2-(1-Pyrrolidinyl)ethyl 4-propoxysalicylate | 238.7279 | 83.5285, 96.8999 | C16H23NO4 | ND | ND | 0.43 |

| 19:42 | Monoethanolamine stearic acid amide | 282.2785 | 85.0523, 98.0602 | C20H41NO2 | 3.21 | ND | ND |

| 20:47 | 3-Cyclopentylpropionamide, N,N-dimethyl- | 170.1547 | 45.0574, 87.0680 | C10H19NO | 0.72 | 0.12 | ND |

| 22:07 | Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(phenylmethyl)- | 244.1207 | 125.0709, 153.0660 | C14H16N2O2 | ND | 0.22 | ND |

| 22:25 | Bis(2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl) ether | 156.1014 | 58.0652, 71.0729 | C8H20N2O | 7.95 | 0.25 | ND |

| 24:55 | Acetaldehyde, diethylhydrazone | 114.0678 | 71.0492, 99.0443 | C6H14N2 | ND | 0.09 | ND |

| 26:59 |

S-[2-[N,N-Dimethylamino]ethyl]N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl thiocarbohydroximate |

218.0808 |

58.0652, 71.0729 |

C8H17N3O2S |

0.20 |

ND |

ND |

|

Phenols |

|||||||

| 09:14 | 2-methyl-6-tert-butylphenol | 164.1196 | 121.0649, 149.0963 | C11H16O | 0.02 | ND | ND |

| 12:02 | 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol | 206.1665 | 57.0700, 191.1431 | C14H22O | 2.00 | ND | ND |

| 12:04 | Phenol, 2,4,6-tris(1-methylethyl)- | 220.1824 | 177.1274, 205.1588 | C15H24O | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.56 |

| 12:05 | Butylated Hydroxytoluene | 220.1824 | 43.0179, 205.1589 | C15H24O | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.65 |

| 12:57 | 2-tert-Butyl-4-methoxyphenol | 180.0781 | 137.0596, 165.0548 | C11H16O2 | 0.35 | ND | ND |

| 16:48 | Resorcinol/3-Hydroxyphenol | 110.0602 | 82.0289, 201.1147 | C6H6O2 | ND | 0.15 | ND |

| 16:52 | Taxicatigenin | 153.9559 | 68.0387, 124.5019 | C8H10O3 | ND | ND | 0.58 |

| 22:14 |

Phenol, 2,2′-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl- |

340.2401 |

161.0964, 177.1277 |

C23H32O2 |

3.52 |

0.76 |

5.21 |

|

Pyridines |

|||||||

| 11:18 | o-phenylpyridine | 154.9679 | 126.5207, 155.9841 | C11H9N | ND | ND | 0.29 |

| 11:19 | m-Phenylpyridine | 155.0730 | 127.0544, 156.0764 | C11H9N | ND | 0.46 | 0.23 |

| 15:05 | 4-pyridinamine, N-[(4-methoxyphenyl)methylene]- | 212.1306 | 91.0544, 197.1073 | C13H12N2O | ND | 0.14 | ND |

| 20:56 |

2,6-diphenyl-pyridine, |

231.1044 |

58.0653, 202.0777 |

C17H13N |

ND |

0.16 |

ND |

|

Sterols |

|||||||

| 28:08 | Ergosta-5,24-dien-3-ol, (3á)- | 384.3342 | 281.2269, 314.2608 | C28H46O | 0.04 | ND | ND |

| 28:11 | Campesterol | 400.3701 | 145.1014, 213.1642 | C28H48O | 0.49 | 0.12 | ND |

| 28:24 | Stigmasterol | 412.3710 | 83.0856, 159.1172 | C29H48O | 1.39 | 0.41 | ND |

| 28:53 | Stigmasta-5,24(28)-dien-3-ol, (3á,24Z)- | 412.3703 | 314.2609, 281.2269 | C29H48O | 0.51 | 0.15 | ND |

| 29:02 | Cycloeucalenol | 412.3684 | 95.0857, 107.0858 | C30H50O | 0.17 | ND | ND |

| 29:06 |

Olean-12-en-3-ol |

426.3862 |

203.1797, 218.2032 |

C30H50O |

0.29 |

ND |

ND |

|

Sulphur related compounds |

|||||||

| 04:13 | Dimethyl trisulfide | 125.9627 | 78.9671, 127.9585 | C2H6S3 | ND | 1.88 | ND |

| 07:16 | 2,5-dihydrothiopene | 86.0364 | 45.0336, 57.0336 | C4H6S | ND | 1.52 | ND |

| 08:18 | Hemineurine | 143.0401 | 85.0108, 112.0217 | C6H9NOS | ND | 0.10 | ND |

| 20:45 | O-Ethyl S-2-diethylaminoethyl ethylphosphonothiolate | 257.7809 | 85.6057, 98.9677 | C10H24NO2PS | ND | ND | 1.21 |

| 21:12 |

1H-Indole-3-carbonitrile, 2-(4-chlorobenzenesulfonylmethyl)-1-methyl- |

225.1118 |

169.1224, 201.1485 |

C17H13ClN2O2S |

ND |

0.08 |

ND |

|

Terpenes and Terpenoid |

|||||||

| 04:56 | Eucalyptol | 154.1354 | 81.0700, 93.0701 | C10H18O | 0.26 | ND | ND |

| 07:02 | Naphthalene | 128.0622 | 76.0307, 99.0442 | C10H8 | 0.34 | 0.27 | ND |

| 28:47 |

Clionasterol |

414.3864 |

145.1015, 213.1643 |

C29H50O |

0.61 |

0.15 |

ND |

|

Vitamins |

|||||||

| 26:08 | ë-Tocopherol | 402.3499 | 137.0599, 177.0914 | C27H46O2 | 3.43 | 1.05 | 4.30 |

| 26:51 | ç-Tocopherol | 416.3654 | 151.0755, 191.1069 | C28H48O2 | 1.77 | 0.41 | 3.28 |

| 23:58 | dl-7-azatryptophan | 204.0760 | 88.0336, 131.0524 | C10H11N3O2 | ND | 0.28 | 1.22 |

tR – Retention time; m/z – mass-to-charge ratio; MF – Molecular formula; ND- Not detected; BGN – Bambara groundnut, DD – Dehulled dawadawa; UHD – Unhulled dawadawa

Figure 1.

GC-HRTOF-MS chromatogram of the BGN (Bambara groundnut), DD (Dehulled dawadawa) and UHD (Unhulled dawadawa) samples.

Figure 2.

(A) Venn diagram showing the relationship between the metabolites in BGN (Bambara groundnut), DD (Dehulled dawadawa) and UHD (Unhulled dawadawa) samples, (B) Pie chart showing percentage distribution of the compounds.

Esters were the principal compounds reported in this study. Other similar studies on fermented condiments contradict this observation, with pyrazines being the major constituent in sonru, afitin, iru (Azokpota et al., 2008), acids the dominant group in castor oil bean fermented condiment (Ojinnaka and Ojimelukwe, 2013), aldehydes in locust bean daddawa, soybean and melon seed ogiri (Onyenekwe et al., 2012), while aldehydes, acids and ketones were reported to dominate dawadawa from BGN using Bacillus species (Akanni et al., 2018a). Nevertheless, esters are major metabolite groups common to several fermented condiments in Africa and are mostly formed during fermentation by esterification of alcohols with fatty acids (Fan and Qian, 2005). Chemical reactions between alcoholic metabolites as well as microbial acidic metabolites could also lead to the formation of esters during fermentation. Their contributions to food aroma/odour are important, combined with the fact that esters at ambient temperatures are highly volatile and their perception thresholds are much lower compared to their alcohol precursors (Nogueira et al., 2005). Compounds belonging to the esters group constitutes 29% (Figure 2B) of the total metabolites recorded and were more prominent in the DD as compared to UHD. Phthalic acid 8-chlorooctyl decyl ester, phthalic acid dicyclohexyl ester and phthalic acid 8-chlorooctyl nonyl ester were the major esters detected in BGN, DD and UHD (Table 1).

The identified compounds in this study could be as a result of the breakdown and constituents in BGN such as proteins, lipids and other bioavailable compounds through the activities of the microbial enzymes. As reflected in the GC-HRTOF-MS data presented in Table 1, fermentation of BGN into derived dawadawa led to the formation, increase, as well as decrease of some compounds. Formation of these constituents could be attributed to the presence of microorganisms involved in the fermentation process and other processing factors as well as operations involved during dawadawa preparation (Azokpota et al., 2010). Compounds belonging to an acid group were only present in UHD samples, which can be attributed to the relatively longer fermentation period for the UHD samples. Acids are sometimes considered as undesirable compounds that confer unpleasant characteristics such as rancid, sweaty and pungent flavors (Frauendorfer and Schieberle, 2008), although they have been reported to confer some acidic, fruity and sour notes in fermented foods (Park et al., 2013).

Compounds belonging to the sulphur related group were mostly present in the DD with none detected in the BGN, in agreement with the study of Akanni et al. (2018b), in which sulphur-related compounds were equally not detected in the raw BGN. Dimethyl trisulfide (sulphur related compound) is known to confer meaty, sulfureous, eggy, alliaceous, cooked, savory, and onion note (Liu et al., 2012). It can also be identified as a possible product of amino acid metabolism (Tamman et al., 2000). Speculated possible amino acid degradation and significantly (p ≤ 0.05) different values in the amino acid of BGN and derived dawadawa (Adebiyi et al., 2019) could also explain the detected amine-related and nitrogenous compounds (Table 1).

Both ketones and aldehydes are formed by fatty acids beta-oxidation as well as oxidation catalyzed by lipoxygenase and hyper-oxidase enzymes, yielding important flavor compounds (Nzigamasabo, 2012). Aldehydes are not only flavor components, but also known as vital reactants associated with heterocyclic compounds formation (Ziegleder, 2009). Ketones are generally derived from amino acid and lipid degradation with the presence of these compounds having an impact on food flavor (Adebo et al., 2018). Nine ketones were detected, i.e. six from DD and three from UHD. The ketones in UHD decreased, as compared to the raw BGN, whereas there was a slight increase of the ketone group in DD (relative to the percentage peak areas). Dehulling of the seedcoats exposed fats related components to more oxygen coupled with removal of available antioxidants in the hull. This thus suggests that fat oxidation would likely be higher in the dehulled samples as compared to the unhulled samples (Akkad et al., 2019). Therefore, an increased level of ketones in the dehulled samples might be due to partial oxidation of the alcohols as well as synthesis through several metabolic pathways, particularly reduction of methyl-ketone (Curioni et al., 2002; Akkad et al., 2019). This may be associated with the disappearance and/or reduction of some ketones in BGN and dawadawa.

Alcohols constituted 3% of metabolites in Figure 2B and are generated by reduction reaction of corresponding aldehydes and oxidation of acids (Pham et al., 2008). According to Estrella et al. (2004), aldehydes and ketones are relatively unstable intermediate compounds and can easily be reduced to alcohols. In total, four alcohols were detected in this study, i.e. 2-undecen-4-ol at high levels in two fermented samples, maltol in BGN and DD, phenylethyl alcohol in DD, with 1-hexadecanol in BGN. The phenylethyl alcohol compound has a rose-like odor and is known as one of the major Korean fermented soy sauce odor-active compounds (Lee et al., 2006), suggesting that these alcohol-related compounds might contribute to the flavor of these dawadawa samples. A decrease in the number of alcohols in the fermented samples might be due to the heat treatment (i.e. cooking) applied during processing (Cho et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019).

The pyridines group was not detected in the BGN except in the dawadawa samples, indicative of a formation of these compounds. Pyridines are usually formed during cooking of food (Gupta et al., 2019) or meat, probably due to the reaction of amino acids with alkanals (Hui, 2012). They are classified as the flavor component of beer and as important organoleptic compounds of foods from cocoa, peanuts, cheeses, beans and barley (Maga, 1981). Due to the physical properties of BGN (hard to cook phenomenon), the seeds are usually cooked briefly then dehulled (depending on the product) prior to fermentation, which might explain the occurrence of pyridines in this study.

Three vitamin-related compounds (Table 1) were detected in dawadawa samples except for dl-7-azatryptophan, which was completely absent in BGN. Other notable vitamins observed were ç-Tocopherol and ë-Tocopherol, which are forms of vitamin E. Not only is vitamin E of nutritional and dietary importance, but it also functions as an antioxidant by preventing the propagation of lipid peroxidation (Frei, 2004). It was observed that in dl-7-azatryptophan, the peak area of UHD (1.22%) was higher than that of DD (0.28%), while UHD has the highest percentage peak area in all the vitamins reported. Furans are heterocyclic compounds, known to possess sweet, roasted, burnt, caramel and sugar notes as previously reported in dawadawa (Akanni et al., 2018a; Azokpota et al., 2008).

Phenols are a major group of antioxidants and of great significance due to their biological and free radical scavenging activities (Koleva et al., 2018). Compounds belonging to the phenol group were also identified in this study. There was formation of taxicatigenin, which is also known as 3,5-dimethoxyphenol in UHD sample. 3,5-dimethoxyphenol belongs to methoxyphenols (a class of compounds comprising of a methoxy group) and connected to the benzene ring of a phenol moiety. The occurrence of this compound and its presence in only UHD could further explain its higher antioxidant activity in a previous study (Adebiyi, 2020), as taxicatigenin is a bioactive compound with potential antioxidant activity (Nithya et al., 2018). Bioactive compounds are also known to inhibit microbial growth that might have contributed to lesser microbial activity in UHD samples, resulting in reduced pH values (Adebiyi et al., 2020). Compounds belonging to the sterols group were common in raw BGN but none of these sterols were detected in UHD. There are claims that naturally occurring plant cholesterols may promote the health of animals and humans once consumed regularly either as food supplements or naturally in foods for a reasonable amount of time (Ogbe et al., 2015).

Fatty acid methyl esters were common in raw BGN, with the formation of methyl esters (myristic acid and cerotic acid methyl esters) in DD, while none of the fatty acid methyl esters were detected in UHD. This difference might have been due to the cooking process adopted (i.e., boiling), as heat treatment is known to affect fatty acid constituents of foods (Ouazib et al., 2015). Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester and octadecanoic acid methyl ester were detected only in raw BGN and are both known as the most abundant saturated fatty acids in nature, reported in plants, animals, lower organisms and functions in cells as specific proteolipids (i.e. connected to internal cysteine residues through thioester bonds) (Anonymous, 2013).

4. Conclusion

A total of 134 metabolites were detected in Bambara groundnuts and derived dawadawa samples using GC-HRTOF-MS. From the two fermented samples, dehulled samples had the highest number of metabolites as compared to their unhulled counterparts. Compounds identified included esters, ketones, phenols, flavor related compounds and constituents that could confer organoleptic properties, nutritional and functional benefits of BGN and derived dawadawa. The BGN seeds and dehulled dawadawa possess beneficial components that can potentially be incorporated into human diets for health benefits. Further investigations into the quantification of the metabolites in this study are still needed, particularly for those significant metabolites obtained in all three samples. These would not only provide a better understanding of legume fermentation, but also assist in providing an insight into these significant metabolites that could potentially be biomarkers of dawadawa.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Janet Adeyinka Adebiyi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Patrick Berka Njobeh, Eugenie Kayitesi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Oluwafemi Ayodeji Adebo: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa (120751) and the NRF of South Africa National Equipment Programme (99047).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Janet Adeyinka Adebiyi, Email: janetaadex@gmail.com.

Eugenie Kayitesi, Email: eugenie.kayitesi@up.ac.za.

References

- Adebiyi J.A., Njobeh P.B., Kayitesi E. Assessment of nutritional and phytochemical quality of dawadawa (an African fermented condiment) produced from Bambara groundnut. Microchem. J. 2019;149:104034. [Google Scholar]

- Adebiyi J.A., Kayitesi E., Njobeh P.B. Mycotoxins reduction in dawadawa (an African fermented condiment) produced from Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) Food Contr. 2020;112:107141. [Google Scholar]

- Adebiyi J.A. University of Johannesburg; South Africa: 2020. Metabolic Profile, Health Promoting Properties and Safety of Dawadawa (A Fermented Condiment) from Bambara Groundnut (Vigna Subterranea) A DTech Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Adebo O.A., Njobeh P.B., Desobgo S.C.Z., Pieterse M., Kayitesi E., Ndinteh D.T. Profiling of volatile flavor compounds in nkui (a Cameroonian food) by solid phase extraction and 2D gas chromatography time of flight mass spectrometry (SPME-GC×GC-TOF-MS) Food Sci. Nutr. 2018;6:2028–2035. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebo O.A., Kayitesi E., Njobeh P.B. Differential metabolic signatures in naturally and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermented ting (a Southern African food) with different tannin content, as revealed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS)-based metabolomics. Food Res. Int. 2019;121:326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebo O.A., Oyeyinka S.A., Adebiyi J.A., Feng X., Wilkin J.D., Kewuyemi Y.O., Abrahams A.M., Tugizimana F. Application of gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS)-based metabolomics for the study of fermented foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;56:1514–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Ademiluyi A.O., Oboh G. Antioxidant properties of condiment produced from fermented Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc) J. Food Biochem. 2011;35:1145–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Akanni G.B., De Kock H.L., Naude Y., Buys E.M. Volatile compounds produced by Bacillus species alkaline fermentation of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranean (L.) Verdc.) into a dawadawa-type African food condiment using headspace solid-phase microextraction and GC × GC–TOFMS. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018;21:929–941. [Google Scholar]

- Akanni G.B., Naude Y., De Kock H.L., Buys E.M. Diversity and functionality of Bacillus species associated with alkaline fermentation of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranean (L.) Verdc.) into dawadawa-type African condiment. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018;244:1147–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Akkad R., Kharraz F., Han J., House J.D., Curtis J.M. Characterisation of the volatile flavour compounds in low and high tannin faba beans (Vicia faba var. minor) grown in Alberta, Canada. Food Res. Int. 2019;120:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Fatty acid: straight-chains saturated, structures occurrence and biosynthesis lipid. 2013. https://www.lipidhome.co.uk/lipids/fa-eic/fa-sat/index.htm

- Azokpota P., Hounhouigan J.D., Annan N.T., Nago M.C., Jakobsen M.S. Diversity of volatile compounds in afitin, iru and sonru, three fermented food condiments from Benin. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;24:879–885. [Google Scholar]

- Azokpota P., Hounhouigan J.D., Annan N.T., Odjo T., Nago M.C., Jakobsen M.S. Volatile compounds, profile and sensory evaluation of Beninese condiments produced by inocula of Bacillus subtilis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010;90:438–444. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brits M., Gorst-Allman P., Rohwer E.R., De Vos J., de Boer J., Weiss J.M. Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to high resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry for screening of organohalogenated compounds in cat hair. J. Chromatogr. A. 2018;1536:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinma C.E., Azeez S.O., Sulayman H.T., Alhassan K., Alozie S.N., Gbadamosi H.D., Danbaba N., Oboh H.A., Anuonye J.C., Adebo O.A. Evaluation of fermented African yam bean flour composition and influence of substitution levels on properties of wheat bread. J. Food Sci. 2020;85:4281–4289. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K., Lim H.-J., Kim M.-S., Kim D.-S., Eun Hwang C., Nam H.S., Joo O.S., Lee B.W., Kim J.K., Shin E.-C. Time course effects of fermentation on fatty acid and volatile compound profiles of Cheonggukjang using new soybean cultivars. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:637–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curioni P.M.G., Bosset J.O. Key odorants in various cheese types as determined by gas chromatography-olfactometry. Int. Dairy J. 2002;12:959–984. [Google Scholar]

- Estrella F.G., Carboell M., Gaya P., Nunze M. Evolution of the volatile components of ewes raw milk Zamorano cheese: seasonal variation. Int. Dairy J. 2004;14:701–711. [Google Scholar]

- Fadahunsi I.F., Olubunmi P.D. Microbiological and enzymatic studies during the development of an ‘Iru’ (a local Nigerian indigenous fermented condiment) like condiment from Bambara nut (Voandzeia subterranean (L) Thours) Mal. J. Micro. 2009;6:123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fan W.L., Qian M.C. Headspace solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography-olfactometry dilution analysis of young and aged Chinese ‘Yanghe Daqu’ liquors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:7931–7938. doi: 10.1021/jf051011k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauendorfer F., Schieberle P. Changes in key aroma compounds of Criollo cocoa beans during roasting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:10244–10251. doi: 10.1021/jf802098f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei B. Efficacy of dietary antioxidants to prevent oxidative damage and inhibit chronic disease. J. Nutr. 2004;134:3196–3198. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.3196S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., O’Loughlin E.J., Sims G.K. Microbial degradation of pyridine and pyridine derivatives. In: Arora P.K., editor. Microbial Metabolism of Xenobiotic Compounds. Springer; Singapore: 2019. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Yang C., Iqbal N., Deng J., Zhang J., Yang W., Liu J. Development and validation of a GC–MS method for soybean organ-specific metabolomics. Plant Prod. Sci. 2018;21:215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hui Y.H. Meat industries: characteristics and manufacturing processes (2. In: Hui Y.H., editor. Handbook of Meat and Meat Processing. CRC press; New York: 2012. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kewuyemi Y.O., Njobeh P.B., Kayitesi E., Adebiyi J.A., Oyedeji A.B., Adefisoye M.A., Adebo O.A. Metabolite profile of whole grain ting (a Southern African fermented product) obtained using two strains of Lactobacillus fermentum. J. Cereal. Sci. 2020;95:103042. [Google Scholar]

- Kiers J.L., VanLaeken A.E.A., Rombouts F.M., Nout M.J.R. In vitro digestibility of Bacillus fermented soya bean. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000;60:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleva L., Angelova S., Dettori M.A., Fabbri D., Delogu G., Kancheva V.D. Antioxidant activity of 3-hydroxyphenol, 2,2'-biphenol, 4,4'-biphenol and 2,2',6,6'-biphenyltetrol: theoretical and experimental studies. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2018;50:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.M., Seo B.C., Kim Y.S. Volatile compounds in fermented and acid-hydrolyzed soy sauces. J. Food Sci. 2006;71:C146–C156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Miao Z., Guan W., Sun B. Analysis of organic volatile flavor compounds in fermented stinky tofu using SPME with different fiber coatings. Molecules. 2012;17:3708–3722. doi: 10.3390/molecules17043708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga J.A. Pyridines in foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1981;29:895–898. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad A., Shahidah A.A., Sambo S., Salau I.A. Effect of starter culture on volatile organic compounds of Bambara groundnut condiment. Afr. J. Env. Nat. Sci. Res. 2018;1:42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Nithya K., Muthukumar C., Biswas B., Alharbi N.S., Kadaikunnan S., Khaled J.M., Dhanasekaran D. Desert actinobacteria as a source of bioactive compounds production with a special emphasis on Pyridine-2,5-diacetamide a new pyridine alkaloid produced by Streptomyces sp. DA3-7. Micro. Res. 2018;207:116–133. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira M.C.L., Lubachevsky G., Rankin S.A. A study of the volatile composition of Minas cheese. Leben.Wissen und Technol. 2005;38:555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Nzigamasabo A. Volatile compounds in Ikivunde and Inyange, two Burundian cassava products. Global Adv. Res. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2012;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Oboh G., Ademiluyi A.O., Akindahunsi A.A. Changes in polyphenols distribution and antioxidant activity during fermentation of some underutilized legumes. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2009;15:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbe R.J., Ochalefu D.O., Mafulul S.G., Olaniru O.B. A review on dietary phytosterols: their occurrence, metabolism and health benefits. Asian J. Plant Sci. Res. 2015;5(4):10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ojinnaka M.T.C., Ojimelukwe P.C. Study of the volatile compounds and amino acid profile in Bacillus fermented castor oil bean condiment. J. Food Res. 2013;2:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira P.M., Zannini E., Arendt E.K. Cereal fungal infection, mycotoxins, and lactic acid bacteria mediated bio protection: from crop farming to cereal products. Food Micro. 2014;37:78–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omafuvbe B.O., Abiose S.H., Shonukan O.O. Fermentation of soybean (Glycine max) for soy–daddawa production by starter cultures of Bacillus. Food Micro. 2002;19:561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Onawola O., Asagbra A., Faderin M. Comparative soluble nutrient value of Ogiri obtained from dehulled and undehulled boiled melon seeds (Cucumeropsis mannii) Food Sci. Qual. Mang. 2012;4:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Onyenekwe P.C., Odeh C., Nweze C.C. Volatile constituents of ogiri, soybean daddawa and locust bean daddawa three fermented Nigerian food flavour enhancers. Electron. J. Environ. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;11:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ouazib M., Nadia M., Oomah B.D., Zaidia F., Wanasundarae J.P.D. Effect of heat processing and germination on nutritional parameters and functional properties of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) from Algeria. J. Food Leg. 2015;28:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Park H.J., Lee S.M., Song S.H., Kim Y.S. Characterization of volatile components in makgeolli, a traditional Korean rice wine, with or without pasteurization, during storage. Molecules. 2013;18:5317–5325. doi: 10.3390/molecules18055317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkouda C., Nielsen D.S., Azokpota P., Ouoba L.I.I., Amoa-Awua W.K., Thorsen L., Hounhouigan J.D., Jensen J.S., Tano-Debrah K., Diawara B. The microbiology of alkaline fermentation of indigenous seeds used as food condiments in Africa and Asia. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;35:139–156. doi: 10.1080/10408410902793056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham A.J., Schilling M.W., Mikel W.B., Williams J.B., Martin J.M., Coggins P.C. Relationships between sensory descriptors, consumer acceptability and volatile flavour compounds of American dry-cured ham. Meat Sci. 2008;80:728–737. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamman J.D., Williams A.G., Noble J., Lloyd D. Amino acid fermentation in non-starter Lactobacillus spp. isolated from cheddar cheese. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;30:370–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2000.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubukata M., Jobst K.J., Reiner E.J., Reichenbach S.E., Tao Q., Hang J., Wue Z., Dane A.J., Cody R.B. Non-targeted analysis of electronics waste by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry: using accurate mass information and mass defect analysis to explore the data. J. Chromatogr. A. 2015;1395:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Fung D.Y. Alkaline-fermented foods: a review with emphasis on pidan fermentation. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1996;22:101–138. doi: 10.3109/10408419609106457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Tamura T., Kyouno N., Liu X., Zhang H., Akiyama Y., Chen J.Y. Effect of volatile compounds on the quality of Japanese fermented soy sauce. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2019;111:594–601. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegleder G. Flavour development in cocoa and chocolate. In: Beckett S.T., editor. Industrial Chocolate Manufacture and Use. 4. ed. Wiley; New Jersey: 2009. pp. 169–191. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.