Abstract

Acankoreagenin (ACK) is a lupane triterpene found in several Acanthopanax and Schefflera plant species. ACK, also known as acankoreanogenin or HLEDA, bears a major structural analogy with other lupane triterpenoids such as impressic acid (IA) and the largely used phytochemical betulinic acid (BA). These compounds display marked anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetes, and anti-cancer properties. BA can form stable complexes with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). The tridimensional structure of the BA-PPARγ complex was used to perform a molecular docking analysis of the binding of ACK and IA to the protein. The 3-hydroxyl epimers (R/S) of each natural product were also modeled to examine the role of the C3-OH stereochemistry that distinguishes BA [3(S)] from ACK and AI [3(R)]. Calculations indicate that ACK can form more stable complexes with PPARγ than BA, upon insertion of the drug into the same binding pocket. The inversion of the C3-OH stereochemistry is not an obstacle for binding and the additional carboxy group of ACK at C23 position seems to reinforce the protein interaction. The 3-hydroxyl group does not play a major role in the geometry of the protein-drug complex, which is preserved between BA and ACK. Additional structure-binding relationships are provided, through the evaluation of the PPARγ binding capacity of ACK derivatives. Binding of ACK to PPARγ would account for its marked antidiabetic effect, at least partially. ACK can be used as a platform to design new antidiabetic compounds.

Keywords: Acankoreagenin, Betulinic acid, PPARγ, Drug-protein binding, Molecular modelling

Introduction

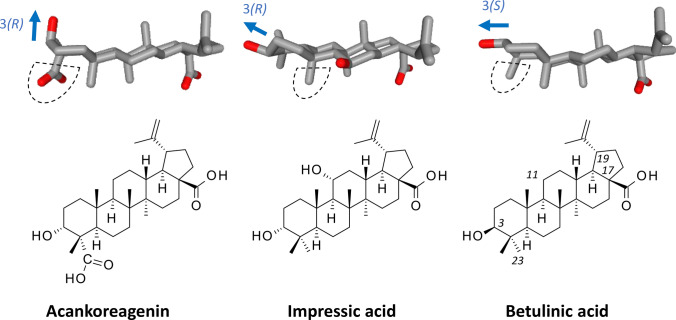

Acankoreagenin (ACK) is a little-known natural product initially isolated from the leaves of the plant Scheflera octophylla (Araliaceae) used in folk medicine (Adam et al. 1982; Sung et al. 1991). It is a lupane-type triterpenoid structurally close to the well-known product betulinic acid (BA), usually extracted from the bark of the common white birch Betula alba (Fig. 1). The two compounds bear the same pentacyclic core, substituted with a carboxyl group and an isopropenyl group at positions C-17 and C-19, respectively. They differ by the presence of a carboxyl group (ACK) or a methyl group (BA) at C-23, and by the orientation of the 3-hydroxyl substituent. BA presents the same (S) stereochemistry at both the C-3–OH and the C-17–COOH, whereas the stereochemistry is 3(R)-17(S) for ACK, as represented in Fig. 1. ACK can be isolated from various Schefflera species, such as S. octophylla, S. actinophylla, and S. heptaphylla (Li et al. 2007; Wanas et al. 2010; Cao et al. 2015), but also from diverse plants of the Acanthopanax family, such as A. gracilistylus, A. koreanum and A. trifoliatus (Liu et al. 2011; Dai et al. 2014; Sithisarn et al. 2011). The product can be found in the leaves or root of these plants. It has been named also acankoreanogenin or HLEDA (for 3-Hydroxy-Lup-20(29) En-23-28-Dioic Acid) in different studies (Zhang 1990; Zhang et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2019).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of acankoreagenin (3α-hydroxy-lup-20(29)-ene-23,28-dioic acid), impressic acid and betulinic acid. In each case, a drug model is shown to highlight the nature of the C-23 substituent and the orientation of the C-3 hydroxyl group: 3(R) or 3β for ACK and impressic acid, 3(S) or 3α for BA

ACK displays potent anti-inflammatory activities. It reduced dose-dependently the serum levels of inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-1β and attenuated the release of the alarmin protein HMGB1 (high mobility group box 1) in a mice model of fulminant hepatitis (Zhang et al. 2011). The anti-inflammatory action has been well characterized in various models in vitro and in vivo (Liu et al. 2017). Notably, a recent study reported the capacity of ACK to inhibit the release of several inflammatory mediators, such as iNOS, COX-2, TNFα, and IL-6, from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine macrophages (Chen et al. 2019). The anti-inflammatory action would derive from the ACK-induced suppression of the transcription factor NFκB activation and inhibition of HMGB1 release. Inhibition of the NFĸB pathway can reduce the production of cytokines-stimulated inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Lu et al. 2018). This property is also useful to control the proliferation of cancer cells. ACK has been found to synergize with anticancer drugs, such as (i) the tubulin polymerization inhibitor docetaxel, reducing the growth and migration of prostate cancer cells, and promoting their apoptotic cell death (Jiang et al. 2015), and (ii) the nucleoside antimetabolite gemcitabine in Panc-1 pancreatic cancer cells, potently inhibiting NFκB and p-STAT3 expression (Jiang et al. 2020). NFκB is a central effector of ACK activity, but apparently not a direct molecular target.

Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that ACK presents potent anti-diabetic effects, associated with the inhibition of different enzymes implicated in type 2 diabetes mellitus, such as α-glucosidase, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) and α-amylase (IC50 = 13, 16 and 31 μM, respectively) (Lu et al. 2018). The compound increased insulin release in pancreatic islet RIN-m5F cells, and this effect was associated with an inactivation of NFκB signaling (Lu et al. 2018). In Chinese traditional medicine, different types of Schefflera or Acanthopanax extracts are used to treat diabetes, hypertension and other conditions and betulinic acid is viewed as an interesting natural remedy for treating metabolic syndrome (Ríos and Máñez 2018). The anti-diabetic effect of ACK, BA and related products, such as impressic acid (IA, Fig. 1), may result from an inhibition of the NFκB pathway and/or inhibition of an upstream target.

One of the targets could well be the protein peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) which is a master regulator of adipocyte differentiation. PPARγ acts as a multi-functional transcription factor to contribute importantly to the regulation of inflammation and type 2 diabetes type, but also to the control of metastasis, tumor growth and angiogenesis (Shafi et al. 2019; Mal et al. 2020). The anti-inflammatory compound IA, structurally close to BA and ACK, has been found to modulate expression of NFκB and PPARγ target genes and to specifically up-regulate the transcriptional activity of PPARγ (Kim et al. 2011). The two compounds IA and ACK display almost identical anti-inflammatory effects (Jiang et al. 2015, 2020). But most importantly, it has been demonstrated that BA can bind directly to PPARγ, to act as an antagonist promoting osteogenesis and inhibiting adipogenesis (Brusotti et al. 2017). The crystallographic structure of BA bound to PPARγ has been solved, revealing a unique binding mode via the formation of a H-bond network with key amino acid residues (Y327 and S289) of the receptor (Brusotti et al. 2017). By analogy, we reasoned that ACK (and IA) might also be able to interact with the PPARγ receptor. This hypothesis was investigated using molecular modeling, comparing the binding capacity of ACK and BA, as well as their 3-epi isomers to shed light on the potential role of the C-3 hydroxyl group in the interaction with the target protein.

Methods

In silico molecular docking procedure

The tridimensional structure of the PPARγ protein bound to BA was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) under the PDB code 5LSG (PPARgamma complex with the betulinic acid) (Brusotti et al. 2017). Docking experiments were performed with the GOLD software (GOLD 5.3 release, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK). Before starting the docking procedure, the structure of the ligands has been optimized using a classical Monte Carlo conformational searching procedure as described in the BOSS software (Jorgensen and Tirado-Rives 2005).

With the 5LSG structure, based on shape complementarity criteria, the binding site for ACK (and IA) has been defined around amino acid residues Y327 and S289. Shape complementarity and geometry considerations are in favor of a docking grid centered in the volume defined by these amino acids. In each case, within the binding site, side chains of specific amino acids have been considered as fully flexible. The flexible amino acids are F282, R288, H323, Y327, L353, F363, K367, F368, Y473, H449. The ligand is always defined as flexible during the docking procedure. Up to 100 poses that are energetically reasonable were kept while searching for the correct binding mode of the ligand. The decision to keep a trial pose is based on ranked poses, using the PLP fitness scoring function [which is the default in GOLD version 5.3 used here (Jones et al. 1997)]. In addition, an empirical potential energy of interaction ΔE for the ranked complexes is evaluated using the simple expression ΔE(interaction) = E(complex)—(E(protein) + E(ligand)). For that purpose, the Spectroscopic Empirical Potential Energy function SPASIBA and the corresponding parameters were used (Vergoten et al. 2003; Lagant et al. 2004). Free energies of hydration (ΔG) were estimated using the MM/GBSA model in Monte Carlo simulations within the BOSS software (Jorgensen et al. 2004). The stability of the receptor-ligand complex is evaluated through the empirical potential energy of interaction (Lagant et al. 2004; Vergoten et al. 2003). The Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) procedure was used to evaluate free energies of hydration (Jorgensen et al. 2004) (within the Boss program (Jorgensen and Tirado-Rives, 2005)), in relation with aqueous solubility (Zafar and Reynisson, 2016). Molecular graphics and analysis were performed using Discovery Studio Visualizer, Biovia 2020 (Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2020, San Diego, Dassault Systèmes, 2020).

Results

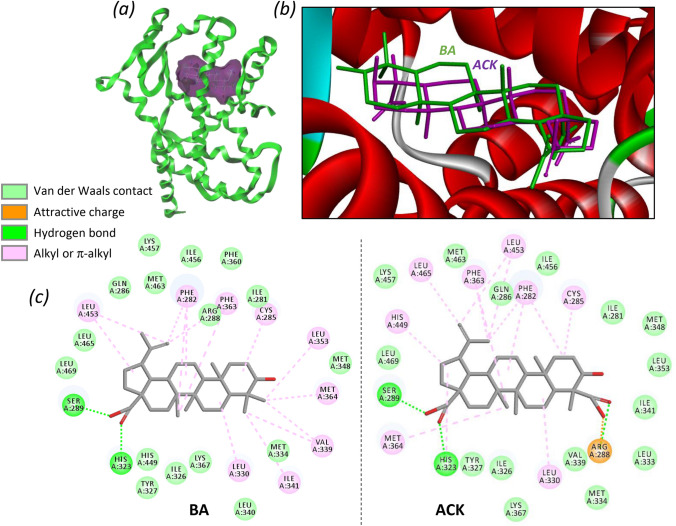

We used the crystal structure of BA bound to PPARγ to model the interaction of ACK with the protein. The drug binding site is located inside the protein, where there is a cavity well adapted to the shape of the molecules, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The T-shaped ligand-binding pocket is known to accommodate various BA derivatives (Chrobak et al. 2019). Different models were constructed with ACK, BA, IA and their 3-OH epimers. In each case, we calculated the empirical energy of interaction (ΔE) and free energy of hydration (ΔG). The values are collated in Table 1. There is no doubt that ACK can fit into the drug cavity, to place itself exactly as BA does. The two compounds can be almost perfectly superimposed (Fig. 2b), the same with IA (not shown). The calculated ΔE values are not markedly different for BA and IA, but interestingly the calculated energy proved to be significantly better with ACK compared to BA. The gain of energy, about 40%, reflects the potentially much better fit of ACK into the PPARγ binding site compared to BA. Not only the isomeric inversion of the 3-hydroxyl group does not seem to be an obstacle for drug binding, but the presence of an additional carboxyl group at the C-23 position significantly reinforces the interaction with the protein (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

a Molecular model of ACK bound to PPARγ (PDB code: 5LSG). ACK (purple volume) fits into the active site cavity of the protein (green). b A close-up view of ACK (purple) and BA (green) superimposed within the active site of the protein receptor with its α-helices in red. The two compounds occupy exactly the same space. c Binding map contacts for acankoreagenin (ACK) and betulinic acid (BA) bound to PPARγ

Table 1.

Calculated potential energy of interaction (ΔE, kcal/mol) and free energy of hydration (ΔG, kcal/mol) for the interaction of the different compounds with PPARγ

| Natural isomers | 3-OH epimers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | ∆E | ∆G | Compound | ∆E | ∆G |

| BA [3(S)] | – 82.6 | – 35.1 | epi– BA [3(R)] | – 83.7 | – 35.4 |

| IA [3(R)] | – 85.7 | – 37.0 | epi– IA [3(S)] | – 81.5 | – 34.9 |

| ACK [3(R)] | – 117.5 | – 33.2 | epi– ACK [3(S)] | – 125.9 | – 34.8 |

BA betulinic acid, IA impressic acid, ACK acankoreagenin

The modeling analysis was performed with the carboxyl groups in the anionic form (COO−). This is the most likely form in biological media, because the acid dissociation constant (pKa) value is about 4.8 for BA and thus the ionized specie must largely predominate over the neutral form under physiological conditions (Khan et al. 2018). Nevertheless, calculations performed with the neutral COOH forms gave similar results, showing a better binding to PPARγ of ACK (ΔG = − 70.4 kcal/mol) compared to BA (ΔG = − 64.9 kcal/mol). CKA can be viewed as a bona fide PPARγ binder, at least in silico.

It is interesting to analyze the drug-protein contact maps, to identify the amino acids implicated in the interaction and the nature of the molecular contacts with the ligands (Fig. 2c). Two key points emerge from the analysis. First, the 3-hydroxyl group of BA or ACK does not appear to be significantly implicated in the protein interaction. It is apparently a neutral element for the interaction, neither reinforcing nor destabilizing the drug-protein complex. We modeled all 3-hydroxyl R/S epimers of BA, IA and ACK and found relatively little or no difference for each couple of compounds. For example, BA and epi-BA bind equally well to PPARγ, and this is consistent with the experimental observation that the 3(R) isomer of BA (3-epibetulinic acid, also a natural product found in some plant species) is a bioactive compound. In the ACK and IA series, both the natural 3(R) isomers and the corresponding 3(S) epimers can form stable complexes with PPARγ (Table 1). Second, the additional carboxyl function of ACK at position C-23 offers a key ionic interaction with R288 residue within the drug binding site of PPARγ, strongly reinforcing the drug-protein interaction. ACK binds to the same site as BA, and the key contacts with amino acids Y327 and S289, which were found to be important for drug binding (Brusotti et al. 2017), are identical in the cases of BA and ACK.

Our model of ACK bound to PPARy offers opportunities to guide the design of analogues targeting this receptor and to help identifying novel antidiabetic drugs for patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. We introduced various substituents at positions C11, C17, C19 or C23 (Fig. 3). These substituents were chosen based on known glycoside derivatives of ACK. The addition of a hydroxyl group at C-11 (as found in several acankoreosides, such as Ack-B, -C, -D, -I and others) does not significantly affect the binding interaction of the compound with PPARy. The modification of the C23 acid function negatively impacts PPARy binding. Replacement of the -COOH with a -CH2OH, CHO or COOCH3 group markedly reduces the PPARy binding capacity. The incorporation of an α-d-glucose residue at C-17 appears extremely detrimental to the receptor interaction. This is consistent with the key stabilizing interactions between the C17-COOH group ACK and amino acids S289 and Y327 of PPARy (Fig. 2). In contrast, we found that the PPARy binding capacity of the ligand can be improved upon modification of the C19 position. The addition of a hydroxyl group on the isopropenyl side chain at C19 provided a compound with an enhanced capacity to bind to PPARy. A gain of energy of about 10% was observed (Fig. 3). Such a hydroxy-isopropenyl side chain can be found on several acankoreosides, such as Ack-F, -G, -I, -M and -N. The incorporation of an acid function on the isopropyl chain (as found in Ack-H) further reinforces the protein interaction, with a gain of energy of about + 20%. On the opposite, a dihydroxy-isopropyl chain (as in Ack-K) appears as a detrimental element for PPARy binding. Based on this information, we can prioritize the design of C19-modified ACK derivatives. The ACK-PPARy model will be useful to guide to the conception of analogues and to evaluate the PPARy interaction properties of acankoreosides.

Fig. 3.

ACK structure-PPARγ binding relationships. Different ACK derivatives, bearing modified substituents at positions C11, C17, C19 or C23, as indicated, have been modeled to determine their PPARγ binding capacity. The calculated potential energy of interaction (ΔE) value is indicated for each compound. Compared to ACK, the C11, C17 and C23 modifications all diminish the calculated ΔE value (less negative), whereas a gain of energy can be obtained upon appropriate modification of the C19 position, as indicated. A molecular model of an ACK derivative bearing a hydroxy-isopropenyl group at C19, bound to PPARγ is shown on the left

Conclusion

Our in silico analysis suggests that the lupane triterpene acankoreagenin (ACK), endowed with marked anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic properties, could form stable complexes with the PPARγ receptor, as reported with its structural analogue betulinic acid. The docking measurements reveal that ACK could fit into the same drug cavity as BA and IA within PPARγ. Our analysis also indicates that the isomeric orientation of the 3-hydroxy group of BA, ACK and IA is not a key element of the protein interaction. This observation may explain, at least in part, why other 3-epi analogues of BA, such as 3-epibetulinic acid, 3-epibetulin and 3-epilupeol are bioactive compounds. Our in silico analysis offers now a rational to investigate further the bioactivities of ACK, IA and derivatives, notably their many glycosides derivatives (acankoreosides). Our work also calls for further studies to clarify the effect of BA and analogues of the PPARγ receptor. The binding study has qualified BA as a PPARγ antagonist that improves glucose uptake and inhibits adipogenesis (Brusotti et al. 2017), while other studies reported that BA and derivatives can activate PPARγ (Chintharlapalli et al. 2007; Jingbo et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2018) or acts as a co-regulator of PPARγ (Mohsen et al. 2019). Similarly, IA was shown to behave as a PPARγ agonist, which upregulates the transcriptional activity PPAR, notably by elevating the expression of PPARγ-1, PPARγ-2 (Kim et al. 2011). ACK likely exhibits comparable PPARγ-modulating effects, because the two compounds present very similar anti-inflammatory effects. Both IA and ACK down-regulate the activation of NFκB and decrease the release of the same inflammatory mediators (Chen et al. 2019). ACK can be a useful natural product to clarify the nature of these effects on PPARγ and to design novel types of antidiabetic compounds.

Abbreviations

- ACK

Acankoreagenin

- BA

Betulinic acid

- IA

Impressic aci

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

Author contributions

GV: Investigation; Visualization; Software. CB: Conceptualization; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adam G, Lischewski M, Phiet HV, Preiss A, Schmidt J, Sung TV. 3αHydroxy-Lup-20(29)-ene-23,28-dioic acid from Schefflera octophylla. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:1385–1387. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(82)80147-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brusotti G, Montanari R, Capelli D, Cattaneo G, Laghezza A, Tortorella P, Loiodice F, Peiretti F, Bonardo B, Paiardini A, Calleri E, Pochetti G. Betulinic acid is a PPARγ antagonist that improves glucose uptake, promotes osteogenesis and inhibits adipogenesis. Scientific Rep. 2017;7:5777. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao KY, Qiao CF, Zhao J, Xie J, Li SP. Quantitative analysis of acankoreoside A and acankoreagenin in the leaves of Schefflera octophylla and Schefflera actinophylla using pressurized liquid extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with evaporative light scattering detection. J Sep Sci. 2015;38:2201–2207. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Qin Y, Ma H, Zheng X, Zhou R, Sun S, Huang Y, Duan Q, Liu W, Wu P, Xu X, Sheng Z, Zhang K, Li D. Downregulating NF-κB signaling pathway with triterpenoids for attenuating inflammation: in vitro and in vivo studies. Food Funct. 2019;10:5080–5090. doi: 10.1039/C9FO00561G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Liu S, Jutooru I, Chadalapaka G, Cho SD, Murthy RS, You Y, Safe S. 2-cyano-lup-1-en-3-oxo-20-oic acid, a cyano derivative of betulinic acid, activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in colon and pancreatic cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2337–2346. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrobak E, Kadela-Tomanek M, Bębenek E, Marciniec K, Wietrzyk J, Trynda J, Pawełczak B, Kusz J, Kasperczyk J, Chodurek E, Paduszyński P, Boryczka S. New phosphate derivatives of betulin as anticancer agents: Synthesis, crystal structure, and molecular docking study. Bioorg Chem. 2019;87:613–628. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L, Liu XQ, Xie X, Liu HY. Characterization of stereostructure by X-ray and technology of extracting in combination hydrolysis in situ of acankoreanogenin from leaves of Acanthopanax gracilistylus W. W Smith J Cent South Univ. 2014;21:3063–3070. doi: 10.1007/s11771-014-2277-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Zhang K, He Y, Xu X, Li D, Cheng S, Zheng X. Synergistic effects and mechanisms of impressic acid or acankoreanogein in combination with docetaxel on prostate cancer. RSC Adv. 2015;8:2768–2776. doi: 10.1039/C7RA11647K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Li DL, Chen J, Zheng X, Wu PP, Li C, Xu XT, Zhang K. Synergistic anticancer effect of gemcitabine combined with impressic acid or Acankoreanogein in panc-1 cells by inhibiting NF-κB and Stat 3 activation. Nat Prod Commun. 2020;15:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jingbo W, Aimin C, Qi W, Xin L, Huaining L. Betulinic acid inhibits IL-1beta-induced inflammation by activating PPAR-gamma in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;29:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen WL, Tirado-Rives J. Molecular modeling of organic and biomolecular systems using BOSS and MCPRO. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1689–1700. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen WL, Ulmschneider JP, Tirado-Rives J. Free energies of hydration from a generalized Born model and an ALL-atom force field. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:16264–16270. doi: 10.1021/jp0484579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MF, Nahar N, Rashid RB, Chowdhury A, Rashid MA. Computational investigations of physicochemical, pharmacokinetic, toxicological properties and molecular docking of betulinic acid, a constituent of Corypha taliera (Roxb.) with Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18:48. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Yang SY, Song SB, Kim YH. Effects of impressic acid from Acanthopanax koreanum on NF-κB and PPARγ activities. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34:1347–1351. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagant P, Nolde D, Stote R, Vergoten G, Karplus M. Increasing normal modes analysis accuracy: the SPASIBA Spectroscopic Force Field Introduced into the CHARMM Program. J Phys Chem A. 2004;108:4019–4029. doi: 10.1021/jp031178l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Jiang R, Ooi LS, But PP, Ooi VE. Antiviral triterpenoids from the medicinal plant Schefflera heptaphylla. Phytother Res. 2007;21:466–470. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XQ, Zheng LS, Weng LN, Li LL. smashing tissue extraction of active triterpenoids of anti-HMGB1 from leaves of Acanthopanax Gracilistylus W.W.Smith. J Cent South Univ (Science and Technology) 2011;42:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Liu XQ, Zou QP, Huang JJ, Yook CS, Whang WK, Lee HK, Kwon OK. Inhibitory effects of 3alpha-hydroxy-lup-20(29)-en-23, 28-dioic acid on lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, and the high mobility group box 1 release in macrophages. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2017;81:1305–1313. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2017.1301803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MX, Yang Y, Zou QP, Luo J, Zhang BB, Liu XQ, Hwang EH. Anti-diabetic effects of Acankoreagenin from the leaves of Acanthopanax Gracilistylus herb in RIN-m5F Cells via suppression of NF-kappaB activation. Molecules. 2018;23:958. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mal S, Dwivedi AR, Kumar V, Kumar N, Kumar B, Kumar V. Role of peroxisome proliferated activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) in different disease states: recent updates. Curr Med Chem. 2020 doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200716113136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsen GAM, Abu-Taweel GM, Rajagopal R, Sun-Ju K, Kim HJ, Kim YO, Mothana RA, Kadaikunnan S, Khaled JM, Siddiqui NA, Al-Rehaily AJ. Betulinic acid lowers lipid accumulation in adipocytes through enhanced NCoA1-PPARgamma interaction. J Infect Public Health. 2019;12:726–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos JL, Máñez S. New pharmacological opportunities for betulinic acid. Planta Med. 2018;84:8–19. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi S, Gupta P, Khatik GL, Gupta J. PPARgamma: potential therapeutic target for ailments beyond diabetes and its natural agonism. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20:1281–1294. doi: 10.2174/1389450120666190527115538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sithisarn P, Jarikasem S, Thisayakor K (2011) Acanthopanax trifoliatus, a potential adaptogenic thai vegetable for health supplement. In: Rasooli I (ed) Phytochemicals. “Bioactivities and Impact on Health’’. 10.5772/27762 (ISBN: 978-953-307-424-5)

- Sung TV, Steglich W, Adam G. Triterpene glycosides from Schefflera octophylla. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:2349–2356. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(91)83647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergoten G, Mazur I, Lagant P, Michalski JC, Zanetta JP. The SPASIBA force field as an essential tool for studying the structure and dynamics of saccharides. Biochimie. 2003;85:65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(03)00052-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanas AS, Matsunami K, Otsuka H, Desoukey SY, Fouad MA, Kamel MS. Triterpene glycosides and glucosyl esters, and a triterpene from the leaves of Schefflera actinophylla. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2010;58:1596–1601. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu GM, Zan T, Li HY, Han JF, Liu ZM, Huang J, Dong LH, Zhang HN. Betulin inhibits lipopolysaccharide/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury in mice through activating PPAR-gamma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:941–945. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar A, Reynisson J. Hydration free energy as a molecular descriptor in drug design: a feasibility study. Mol Inform. 2016;35:207–214. doi: 10.1002/minf.201501035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SR. Effect of 3-hydroxy-lup-20(29)en-23-28-dioic acid on rat experimental gastric ulcers. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 1990;12:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BX, Li N, Zhang ZP, Liu HB, Zhou RR, Zhong BY, Zou MX, Dai XH, Xiao MF, Liu XQ, Fan XG. Protective effect of Acanthopanax gracilistylus-extracted Acankoreanogenin A on mice with fulminant hepatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:1018–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]