Abstract

Few studies examined comorbid anxiety and depression’s independent association with dementia. We assessed internalizing disorders as risk factors for dementia to avoid pitfalls inherent in separating anxiety and depression. Retrospectively designed prospective comparative cohort study using New Zealand’s (NZ) National Minimum Dataset of hospital discharges. Hazards ratios (HRs), estimated from parametric survival models, compared the time to incident dementia after a minimal latency interval of 10 years between those with and without prior diagnosis of an internalizing disorder. A total of 47,932 patients aged 50–54 years were discharged from a publicly funded hospital events in NZ between 1988 and 1992. Of these, 37,631 (79%) met eligibility criteria, and incident dementia was diagnosed in 1594. Rates of incident dementia were higher among patients with an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders (572 vs 303 per 100,000 person years at risk (PYAR)). After adjustment for age, sex, ethnicity, and region, those with internalizing disorders were estimated to have a higher risk of developing dementia than those without (adjusted HR = 1.57, 95% CI 1.17–2.10). Females with an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders were estimated to have almost twice the risk of developing dementia (adjusted HR 1.80, 95% CI 1.25–2.59). Internalizing disorders affect one in five adults globally. Our findings suggest a significant increase in risk of dementia more than 10 years after the diagnosis of internalizing disorder.

Keywords: Internalizing disorders, Dementia, Risk

Introduction

Depression has been systematically studied in relation to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. In a recent large longitudinal cohort study, researchers followed the trajectory of depressive symptoms and dementia in 10,189 people for 28 years [1]. Unlike previous studies [2], depressive symptoms in midlife were not predictive of an increased risk of dementia [1]. In contrast, another 2017 longitudinal study involving 4992 older men found that those who had a history of depression earlier in life had a higher risk of dementia [3]. There are fewer studies examining whether anxiety is independently associated with dementia [4]. A recent meta-analysis of 7 prospective cohort studies reported a marginally positive association between anxiety and Alzheimer’s disease risk [5]. The issue is further complicated by studying concepts closely related to anxiety such as stress, distress, neuroticism, and personality style [6]. Neuroticism can be conceptualized as an abiding tendency towards depression or anxiety in stressful circumstances. Such distress proneness is associated with expression of dementia in those with Alzheimer’s disease pathology [7].

The complexity of the findings and the frequently conflicting reports calls for a different approach to try and solve the anxiety-depression-dementia conundrum. We suggest that capturing dimensional level of diagnoses from general hospital discharge database will compensate for several major obstacles for this research topic. First, large electronic databases representing general hospital discharges offer an opportunity to enlarge analyzed samples [8]. Hospital discharge data have been used successfully to capture psychiatric morbidity and its relevant epidemiological parameters [9]. Second, there is now sufficient evidence to consider replacing the present groupings of disorders with an empirical structure that reflects the actual similarities among disorders grouping depression and anxiety disorders as internalizing disorders [10, 11].

Furthermore, comorbidity is the norm among common mental disorders, as more than 50% of people with a mental disorder in a given year have multiple disorders [12]. Research using factor analysis documented associations among hierarchy-free anxiety and mood disorders accounted for by correlated latent predispositions to internalizing anxiety and mood disorders [13]. Capturing internalizing disorders as a spectrum has two advantages; non-psychiatric physicians’ ability to diagnose specific disorders within spectrums has been shown to be imperfect [14]. Thus, the complex comorbidity of anxiety and depression may be better represented in general hospital discharge database if we rely on higher level dimensional categorization. The second more significant advantage of analyzing internalizing disorders rather than anxiety, depression, or both lies in the robust evidence that this artificial dichotomy is not clinically valid [15]. Multivariate research has indicated that a latent general liability—internalizing liabilities, not the individual disorders—accounts for higher-than-chance levels of mood and anxiety disorder comorbidity and better predicts future internalizing pathology, suicide attempts, angina, and ulcer [10, 16]. Internalizing liability appears to reflect a coherent heritable risk structure for many putatively distinct disorders, highlighting its potential etiological informativeness [15].

We hypothesized that analyzing internalizing disorders may be more relevant than disorder-specific research in order to investigate the role of anxiety and depression in the risk of developing late life dementia. This research addressed the question as to whether those diagnosed with an internalizing disorder in midlife are more or less likely to be diagnosed with dementia in later life.

Methods

Design

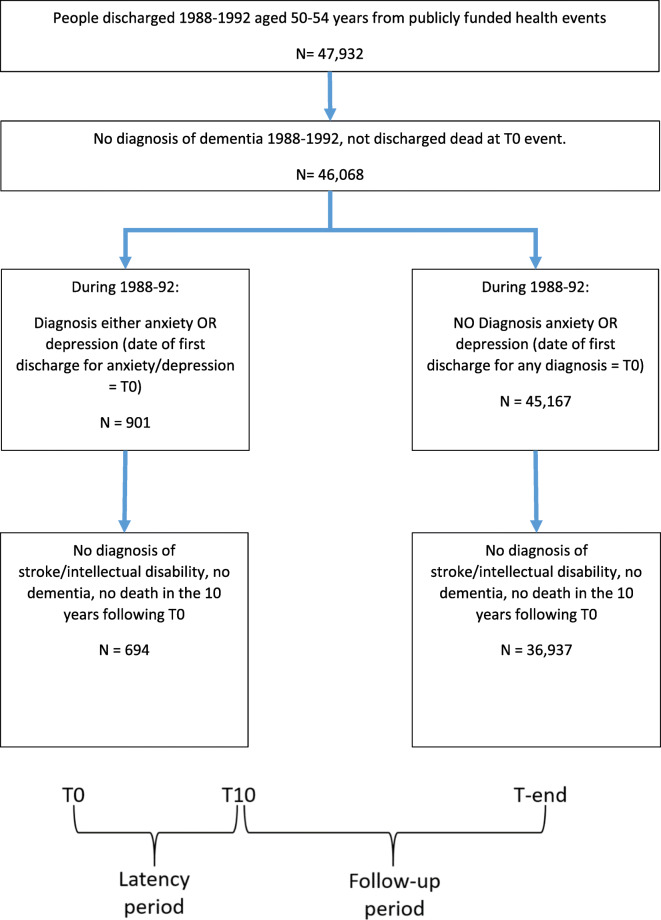

This was a retrospectively designed prospective comparative cohort study. A number of steps were undertaken to obtain the analytical dataset from routinely collected data in New Zealand’s National Minimum Dataset of hospital discharges [17]. Figure 1 outlines the process, described in more detail below, of selecting the cohort, identifying those with an internalizing disorder and those with diagnosed dementia.

Fig. 1.

Cohort identification

Data

Records related to all publicly funded hospital events for patients discharged between 1 January 1988 and 31 December 1992 and aged 50–54 years at the time of discharge were extracted by the Ministry of Health. Patients within this dataset formed the basis of the cohort. It is important to note that the dataset was for all-cause admissions and not only for patients admitted due to an internalizing disorder. Those discharged within this period with a (primary or additional) diagnosis of anxiety states, phobic disorders including social phobia and obsessive compulsive disorders (International Classification of Diseases Chapter 9 Australian version of the Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CMA) code of 300.00, 300.01, 300.02, 300.09, 300.20–300.23, 300.29, or 300.3) or any (primary or additional) diagnosis of depression (ICD-9-CMA code of 296.2, 296.3, 296.90–296.99, 300.4, and 311) were classified as having an internalizing disorder.

Definition

Internalizing liability appears to reflect a coherent heritable risk structure for many putatively distinct disorders, highlighting its potential etiological informativeness [15]. We based our capture of internalizing disorders on the organizational “metastructure” grouping internalizing disorders together as described by Eaton and colleagues [16]. The date of the first discharge within 1988–1992 for an internalizing disorder was considered “time 0” (T0). For patients without an internalizing disorder discharge diagnosis, T0 was taken as the date of their first discharge within 1988–1992. For both groups, patients discharged dead at T0 were excluded from the study.

Analyzed records

For the resulting patients, a separate data extract of publicly funded hospital discharges from 1 January 1988 to 31 December 2016 was obtained to identify cases of dementia and cases that met the study’s further inclusion/exclusion criteria. A latency period of 10 years after each patient’s T0, symbolized by T10, was used to ensure that the internalizing disorder was not a “prodromal” manifestation of dementia [18]. Patients with any (primary or additional) discharge diagnoses of dementia (ICD-9-CMA 290.00 to 294.43 and 294.10 to 294.21; ICD Chapter 10 (ICD-10) F00, F01, F02.0, F02.1 and F03, F05.1, F06.8, F06.9, G30, G31.1, G31.9) following T10 were identified. The earliest admission date for which the associated discharge had dementia recorded was taken as the date of “incident dementia.” Those diagnosed with an incident dementia date on or before T10 (either within 1988–1992 or within the T0–T10 latency period) were excluded, as were those that died during the latency period (T0–T10). In addition, patients discharged with cerebrovascular diseases (ICD-9-CMA 433, 434, and 435; ICD-10 I60–I69, G45) and intellectual disability (ICD-9-CMA 317, 318.0, 318.1, 318.2, and 319; ICD-10 F70–F79) during the latency period were excluded. These exclusion criteria were employed as the risk of developing dementia among individuals with an intellectual disability is highlighted by epidemiological surveys [19], but comprehensive information about reliability and validity of a diagnosis of dementia in individuals with intellectual disability is deficient in non-specialist services [20]. The association between incident ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause dementia, and depression has been reviewed in a recent meta-analysis. Pooled analyses showed that stroke is strongly associated with incident, all-cause dementia, and depression, and thus can be considered a confounder in studies seeking to untangle the association between depression and dementia [21].

Using date of death supplied by the Ministry of Health, the cohort was restricted to cases alive at T10. Those that died during the follow-up period (Table 1) were included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Population demographics

| Earlier diagnosis of an internalizing disorder: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p value* | |||

| (N = 694) | (N = 36,937) | ||||

| No. | Col % | No. | Col % | ||

| Age | |||||

| 50 | 111 | 16.0 | 7252 | 19.6 | 0.2 |

| 51 | 147 | 21.2 | 7121 | 19.3 | |

| 52 | 130 | 18.7 | 7081 | 19.2 | |

| 53 | 141 | 20.3 | 7172 | 19.4 | |

| 54 | 165 | 23.8 | 8311 | 22.5 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 427 | 61.5 | 19,634 | 53.2 | < 0.0005 |

| Male | 267 | 38.5 | 17,303 | 46.8 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Maori | 36 | 5.2 | 3351 | 9.1 | < 0.0005 |

| NZ European | 337 | 48.6 | 31,447 | 85.1 | |

| Other | 321 | 46.3 | 2139 | 5.8 | |

| Died after T10 | |||||

| Yes | 287 | 41.4 | 11,921 | 32.3 | < 0.0005 |

| No | 407 | 58.6 | 25,016 | 67.7 | |

| Years from T10 | |||||

| 13 or less | 234 | 33.8 | 9256 | 25.1 | < 0.0005 |

| 14–15 | 167 | 24.1 | 11,527 | 31.2 | |

| 16–17 | 191 | 27.6 | 10,097 | 27.3 | |

| 18–19 | 101 | 14.6 | 6057 | 16.4 | |

*From chi-squared test

Comparison of participants with and without midlife internalizing disorders

Date of birth, date of discharge, sex, and ethnicity were obtained from hospital discharge data. Using the date variables, age in years at T0 was calculated. Routinely collected self-identified ethnicity from each patient’s T0 hospital discharge event was used to classify ethnicity into three categories as follows: “Māori” (NZ’s indigenous population), “NZ European,” and “Other.”

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including chi-squared tests were used to compare the two groups of interest, i.e., those with an earlier diagnosis of an internalizing disorder and those without. For incidence calculations, all individuals were followed-up until the earliest of 31 December 2016, date of death, or date of incident dementia. To understand patterns in dementia risk over time, Kaplan-Meier functions of time to incident dementia were produced by sex for those with and without an earlier diagnosis of an internalizing disorder. Parametric survival models that used exponential distribution were used to estimate hazards ratios (HRs) for dementia for those with internalizing disorders relative to those without. Crude and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were estimated overall and stratified by sex. Age and years from T10 were included as continuous variables.

Data management was conducted using the SAS software, version 9.4, and the Stata SE version 15.1 was used for the analysis [22–24].

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Results

There were 47,932 patients discharged from a publicly funded hospital event in New Zealand between 1988 and 1992 that were aged 50–54 years at the time of discharge. Figure 1 details the cohort identification. Briefly, of the 46,068 patients discharged alive who had no diagnosis of dementia between 1988 and 1992, 901 (2%) had a diagnosis of an internalizing disorder. By the end of 10 years following T0 (discharge in the period 1988–1992), the latency period, 694 patients with internalizing disorder and 36,937 patients free of internalizing disorders had been free of intellectual disability, had not suffered from stroke or dementia, and had not died. Thus, 37,631 patients’ records were eligible to be analyzed during the follow-up period extending beyond the latency 10 years period. Person years at risk (PYAR) ranged from 3 days to 19 years with a quarter of the cohort having 13 years or less follow-up and 16% of the cohort having 18–19 years follow-up. Table 1 details the demographics of the two groups herein followed. An earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorder (N = 694) compared with “no” internalizing disorder (n = 36,937) was significantly more common in women (61.5% vs 53.2%; p < 0.0005), in non-European, Māori, and other ethnicities (51.5% vs 14.9%; p < 0.0005) and associated with higher mortality rate after the completion of the latency (10 years) period (41.4% vs 32.3%; p < 0.0005).

Risk of developing dementia

Incident dementia was diagnosed in 1594 of 37,631 patients who entered the follow-up period. Figure 2 presents the Kaplan-Meier failure time graphs of incident dementia by sex for those with and without an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders. These graphs illustrate that those with an internalizing disorder are more likely to “fail,” that is have a diagnosis of dementia recorded in their hospital discharge record compared to those without an internalizing disorder. For males, this is apparent from the start of the follow-up period, whereas for females, there appears to be a lag with no separation between the Kaplan-Meier curves for the first five to seven years.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots showing the effect of sex and internalizing disorder on probability of dementia. ID, internalizing disorders

The rate of incident dementia was higher among all patients with an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders (572 per 100,000 PYAR vs 303 per 100,000 PYAR) (Table 2). The crude hazards ratio was calculated to be 1.89 (95% CI 1.43–2.49). After adjustment for age, sex, and ethnicity, the risk estimate reduced, but those with internalizing disorders were still estimated to have a higher risk of developing dementia than those without (adjusted HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.17–2.21).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted hazard ratios

| Incident dementia | Crude hazards | Adj. hazard ratio* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Earlier diagnosis of an internalizing disorder | Sample | No. | Percent | Rate per 100,000 person years at risk | Est. (95% CI) | Est. (95% CI) |

| All | No | 36,937 | 1543 | 4.2 | 303 (288, 319) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 694 | 51 | 7.3 | 572 (435, 753) | 1.89 (1.43, 2.49) | 1.57 (1.17, 2.10) | |

| Males | No | 17,303 | 761 | 4.4 | 329 (307, 353) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 267 | 17 | 6.4 | 505 (314, 813) | 1.54 (0.95, 2.48) | 1.24 (0.75, 2.05) | |

| Females | No | 19,634 | 782 | 4.0 | 282 (263, 303) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 427 | 34 | 8.0 | 613 (438, 857) | 2.17 (1.54, 3.07) | 1.80 (1.25, 2.59) | |

*Adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity; in analyses stratified by sex, estimates were adjusted for age and ethnicity

For males, the rate of incident dementia was 505 per 100,000 PYAR among patients with an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders compared to 329 per 100,000 PYAR for those without. Although the adjusted HR suggested higher risk for males with internalizing disorders, there was considerable uncertainty around this estimate as indicated by the CI width (adjusted HR 1.24, 95% CI 0.75–2.05). For females, the rate of incident dementia was 613 per 100,000 PYAR among patients with an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders compared to 282 per 100,000 PYAR for those without. Females with an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders, compared to those without, were estimated to have almost twice the risk of developing dementia (adjusted HR 1.80, 95% CI 1.25–2.59).

Discussion

Whether depression or anxiety is prodromal symptoms or independent risk factors for dementia has been debated hotly over the last decade. The Lancet Commissions on dementia prevention, intervention, and care emphasize that it is only in the 10 years before dementia incidence that depressive symptoms are high, suggesting that midlife depression is not a risk factor for dementia. However, the Commissions’ authors allowed that it is biologically plausible that depression increases dementia risk because it affects stress hormones and anxiety comorbidity [25]. The present study adopted the cautionary criteria suggested by the Lancet Commissions and by the prospective Three-City Study [26] and analyzed risk of dementia only after a 10-year latency period from diagnosis of an internalizing disorder. Our findings suggest that there is a significant increase in incident dementia for patients suffering from midlife internalizing disorders even after adjusting for several demographic variables, particularly in women.

Many risk factors for dementia have been identified in the literature. One such risk factor is premorbid depression. However, contradictory evidence exists on whether the relationship between depression and later dementia is an association or causal. Less is known about the role of premorbid anxiety despite evidence of close comorbidity with depression and evidence that anxiety may be a predisposing factor for depression [27]. A 2013 study aimed to examine relative associations of a prior anxiety diagnosis, or a prior depression diagnosis, with future diagnosis of dementia in primary care.

The authors found that a past anxiety diagnosis was associated with a future dementia diagnosis; the association of depression with dementia was attenuated by the high prevalence of comorbid anxiety among depressed patients [28]. In a second large study aimed to examine the association between trait anxiety and the 10-year risk of incident dementia to determine to which extent depressive symptoms influence this relationship, 5234 community-dwelling participants aged 65 years at baseline demonstrated that high trait anxiety increased the risk of dementia. However, the associations were substantially attenuated after further adjustment for depressive symptoms. Indirectly, these two informative studies support our contention that internalizing disorders are a risk for incident dementia and attempts to split these into anxiety or depression are impaired by the attenuating effects of comorbidity [26]. Stress can have a damaging effect on brain health.

A recent study using a random-effects model demonstrated that risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia was still significant when excluding studies with critical risk of bias, thus concluding anxiety is a risk factor for both types of dementia. However, the authors concluded that the temporal and functional relation between anxiety and dementia needs investigation in future studies [29].

Whether depression is a prodrome or a risk factor for dementia, its independent association with dementia has been verified [1, 18, 30] with the notable exception of a recent large Mendelian randomization analysis [31]. The literature examining associations between anxiety and incident dementia is less precise. In patients with mild cognitive impairment anxiety increases rate of converting to dementia [32–36]. A meta-analysis identifying longitudinal studies on the relationship between anxiety and cognition suggested that anxiety may be a prodrome of dementia [37]. On the other hand, the prestigious Rotterdam Study followed 2708 non-demented participants who endorsed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and 3069 non-demented participants who underwent screening for anxiety disorders. The authors did not find an association between dementia risk and anxiety symptoms or anxiety disorders [38]. An additional prospective study adjusting for age, vascular risk factors, and premorbid cognitive function reported higher anxiety at baseline to be associated with increased dementia risk. The extent to which the association was independent of depression was not answered [39].

The present study has several limitations. The use of hospital discharge data reduces the generalizability of our findings. We relied on routinely collected and clinically based diagnoses by a variety of specialists and thus we are not able to correct for the high symptom threshold required to result in a hospital discharge diagnosis of an internalizing disorder and of dementia. The majority of people suffering from internalizing disorders will be managed in primary care. In the same vein, the majority of people struggling with dementia will not necessarily be hospitalized. Potential risk factors and/or confounders such as medication use, comorbid physical conditions, level of education, and other established risk or protective factors were not included in this study due to data unavailability, data quality, and complexity of inclusion. The non-significant risk in males compared with females with internalizing disorders could be due to differences in population size, and that a larger male cohort may have reached statistical significance. The adjusted HR is likely to be an underestimate as a small percentage of the comparison group; those with no internalizing disorder discharge diagnoses will presumably have been diagnosed with an internalizing disorder during the follow-up period. The present study has two main strengths—the use of a large national study and the use of high quality data.

We may tentatively conclude that through analyzing internalizing disorders, several of the pitfalls in studying the relationship between depression and or anxiety and incident dementia are overcame. Our findings are suggestive of a significant increase in risk of dementia more than 10 years after the diagnosis of internalizing disorder. Further prospective studies following the trajectory of internalizing disorders into old age are needed to support our findings.

Authors’ contributions

YB: conception and design of the study and drafting a significant portion of the manuscript and figures. DB: design of the study, acquisition, and analysis of data drafting a significant portion of the figures. GD: design of the study, acquisition, and analysis of data and drafting a significant portion of the figures PG: conception and design of the study and drafting a significant portion of the manuscript and figures.

DP: conception and design of the study and drafting a significant portion of the manuscript and figures.

Funding

University of Otago, New Researcher Start-Up Award.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

University of Otago Ethics Committee reference number HD18/002.

Consent to participate

NA.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved this manuscript for possible publication.

Code availability

NA.

Footnotes

The relationship between internalizing disorders and incident dementia after a minimal latency interval of 10 years was evaluated. Of patients aged 50-54y discharged from general hospitals between 1988 and 1992, after 10 years, 694 with internalizing disorder and 36,937 patients without served as our cohort. Incident dementia was more common amongst patients with an earlier diagnosis of internalizing disorders (7.3% vs 4.2%). Internalizing disorders were independently predictive of a 57% higher risk of developing dementia. Gender differences were significant with females with an earlier diagnosis of an internalizing disorders estimated to have almost twice the risk of developing dementia (adjusted HR 1.80, 95%CI 1.25-2.59).

Highlights

1) What is the primary question addressed by this study? Are internalizing disorders a risk factor for dementia?

2) What is the main finding of this study? Internalizing disorders were independently predictive of a higher risk of developing dementia, adjusted Hazard Ratio = 1.57 (CI: 1.17–2.10).

3) What is the meaning of the finding? Through analyzing internalizing disorders several of the pitfalls in studying the relationship between depression and or anxiety and incident dementia are overcome.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Fournier A, Abell J, Ebmeier K, Kivimäki M, Sabia S. Trajectories of depressive symptoms before diagnosis of dementia: a 28-year follow-up study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):712–718. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liew TM. Depression, subjective cognitive decline, and the risk of neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L. Depression as a modifiable factor to decrease the risk of dementia. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1117. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krasucki CG. Anxiety as the reason why previous psychiatric illness is a risk factor for dementia. Age Ageing. 1999;28(2):238–239. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santabárbara J, Lipnicki DM, Bueno-Notivol J, Olaya-Guzmán B, Villagrasa B, López-Antón R. Updating the evidence for an association between anxiety and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Affect Disord. 2020;262:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson L, Guo X, Duberstein PR, Hallstrom T, Waern M, Ostling S, Skoog I. Midlife personality and risk of Alzheimer disease and distress: a 38-year follow-up. Neurology. 2014;83(17):1538–1544. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitner JC, Costa PT. “At my wits’ end”: neuroticism and dementia. Neurology. 2003;61(11):1468–1469. doi: 10.1212/WNL.61.11.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rakovac I, Maharjan B, Stein C, Loyola E. Program for validation of aggregated hospital discharge data. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harber P, Ha J, Roach M. Arizona hospital discharge and emergency department database: implications for occupational Health surveillance. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(4):417–423. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews G. Internalizing disorders: the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):302–303. doi: 10.1002/wps.20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews G, Anderson TM, Slade T, Sunderland M. Classification of anxiety and depressive disorders: problems and solutions. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(4):274–281. doi: 10.1002/da.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Zaslavsky AM. The role of latent internalizing and externalizing predispositions in accounting for the development of comorbidity among common mental disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(4):307–312. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283477b22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Scott EM, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Naismith SL, Koschera A. Unmet need for recognition of common mental disorders in Australian general practice. Med J Aust. 2001;175(Suppl):S18–S24. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Knudsen GP, Røysamb E, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal and subsyndromal common DSM-IV axis I and all axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(1):29–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Wall M, Hasin DS, Grant BF. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(1):86–92. doi: 10.1037/a0029598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Health, B. (2014). National Minimum Dataset (hospital events) data dictionary. Wellington: Ministry of Health.. Wellington, New Zealand, Ministry of Health.

- 18.Bennett S, Thomas AJ. Depression and dementia: cause, consequence or coincidence? Maturitas. 2014;79(2):184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinai A, Bohnen I, Strydom A. Older adults with intellectual disability. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(5):359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328355ab26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenzie K, Metcalfe D, Murray G. A review of measures used in the screening, assessment and diagnosis of dementia in people with an intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;31(5):725–742. doi: 10.1111/jar.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rensma SP, van Sloten TT, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CDA. Cerebral small vessel disease and risk of incident stroke, dementia and depression, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;90:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson DB. A simple approach for fitting linear relative rate models in SAS. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(11):1333–1338. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS, I. (2002-2012). The SAS system for Windows. Release 9.4.. Cary, NC., SAS 9.4.

- 24.StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15.. Texas, StataCorp LLC 15.

- 25.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbaek G, Teri L, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortamais M, Abdennour M, Bergua V, Tzourio C, Berr C, Gabelle A, Akbaraly TN. Anxiety and 10-year risk of incident dementia-an association shaped by depressive symptoms: results of the prospective Three-City Study. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:248. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiller JW. Depression and anxiety. Med J Aust. 2013;199(S6):S28–S31. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burton C, Campbell P, Jordan K, Strauss V, Mallen C. The association of anxiety and depression with future dementia diagnosis: a case-control study in primary care. Fam Pract. 2013;30(1):25–30. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker E, Orellana Rios CL, Lahmann C, Rucker G, Bauer J, Boeker M. Anxiety as a risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213(5):654–660. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin, R. (2018). Exploring the relationship between depression and dementia. Jama,. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Huang J, Zuber V, Matthews PM, Elliott P, Tzoulaki J, Dehghan A. Sleep, major depressive disorder and Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomisation study. Neurology. 2020;95:e1963–e1970. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devier DJ, Pelton GH, Tabert MH, Liu X, Cuasay K, Eisenstadt R, Marder K, Stern Y, Devanand DP. The impact of anxiety on conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1335–1342. doi: 10.1002/gps.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer K, Berger AK, Monastero R, Winblad B, Backman L, Fratiglioni L. Predictors of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68(19):1596–1602. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260968.92345.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramakers IH, Verhey FR, Scheltens P, Hampel H, Soininen H, Aalten P, Rikkert MO, Verbeek MM, Spiru L, Blennow K, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Visser PJ. Anxiety is related to Alzheimer cerebrospinal fluid markers in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Psychol Med. 2013;43(5):911–920. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Appleby BS, Oh ES, Geda YE, Lyketsos CG. The association of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI with incident dementia and Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(7):685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teng E, Lu PH, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(4):253–259. doi: 10.1159/000107100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulpers B, Ramakers I, Hamel R, Kohler S, Oude Voshaar R, Verhey F. Anxiety as a predictor for cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(10):823–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Bruijn RF, Direk N, Mirza SS, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Tiemeier H, Ikram MA. Anxiety is not associated with the risk of dementia or cognitive decline: the Rotterdam study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(12):1382–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallacher J, Bayer A, Fish M, Pickering J, Pedro S, Dunstan F, Ebrahim S, Ben-Shlomo Y. Does anxiety affect risk of dementia? Findings from the Caerphilly prospective study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(6):659–666. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a6177c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.