Summary

Reactivation of human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) from latently infected T cells is a critical barrier to cure patients. It remains unknown whether reactivation of individual latent cells occurs stochastically in response to latency reversal agents (LRAs) or is a deterministic outcome of an underlying cell state. To characterize these single-cell responses, we leverage the classical Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test where single cells are isolated from a clonal population and exposed to LRAs after colony expansion. Data show considerable colony-to-colony fluctuations with the fraction of reactivating cells following a skewed distribution. Modeling systematic measurements of fluctuations over time uncovers a transient heritable memory that regulates HIV-1 reactivation, where single cells are in an LRA-responsive state for a few weeks before switching back to an irresponsive state. These results have enormous implications for designing therapies to purge the latent reservoir and further utilize fluctuation-based assays to uncover hidden transient cellular states underlying phenotypic heterogeneity.

Subject areas: Computational Molecular Modeling, Virology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Jurkat HIV latency model (JLat) shows inheritable responsiveness to TNF-α stimulation

-

•

JLat cells may switch between responsive state and irresponsive state spontaneously

-

•

Mathematical modeling indicates a memory timescale on the order of months

Computational Molecular Modeling; Virology

Introduction

With over 37 million infected individuals, human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) remains a global epidemic of unprecedented proportions. Upon infection with HIV-1, CD4+ T cells may progress into a quiescent state called latency where they do not express viral genes and are capable of evading drug treatment. Latently infected cells can reactivate later and reinitiate active replication, causing a resurgence in viral levels if the patient goes off antiretroviral treatment (Figure 1A). The actively replicating virus hijacks the host-cell resources and machinery to create hundreds of viral progeny, lyse the cell, and spread to uninfected bystander cells (Weinberger et al., 2005, 2008). Thus HIV-1 latency remains the major barrier to a cure (Dahabieh et al., 2015; Richman et al., 2009; Ruelas and Greene, 2013; Siliciano and Greene, 2011; Sengupta and Siliciano, 2018). Several strategies exist to control and clear the latent reservoir of HIV-1 infected cells (Dahabieh et al., 2015; Richman et al., 2009; Ruelas and Greene, 2013). Much attention and research has focused on targeting the latent pool of cells with a small molecule treatment called the “shock and kill” strategy (Archin et al., 2012; Deeks, 2012; Rasmussen and Lewin, 2016). In this treatment, cells are reactivated from latency into an active state where they can then undergo killing by cytotoxic T cells and subsequently were cleared from the patient (Figure 1A) (Dahabieh et al., 2015). Unfortunately, “shock and kill” falls short owing to incomplete reactivation and killing of the latent reservoir (Cillo et al., 2014; Zerbato et al., 2019). Furthermore, latency reversal agents (LRAs) have been shown to impair cytotoxic T cell function (Shan et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2014, 2016), and clinical trials with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) and disulfiram, two classes of candidate LRAs, produced no major reduction in the size of the latent HIV-1 reservoir in patients on antiretroviral therapy (Rasmussen and Lewin, 2016). Alternatively, latency promoting agents have also been discovered that silence transcription of latent HIV-1 (Kessing et al., 2017, Dar et al., 2014, Lu et al., 2021), which points to the alternative “block and lock” strategy aiming to stabilize and prolong HIV-1 latency indefinitely.

Figure 1.

Heritable versus random reactivation response of HIV-1 latency to an external stimulus

(A) HIV-1 infection results in two phenotypes: active replication (red) where the infected cells produce new virions and latent infection (gray) where infected cells do not produce virions. Latently infected cells can reactivate and initiate virion production through cellular and environmental fluctuations.

(B) The cell line used in our investigation, the Jurkat latency model (JLat), is latently infected with a full-length HIV-1 gene circuit, with a deletion of env reading frame and a replacement of nef reading frame with a GFP element.

(C) Histogram of single-cell GFP fluorescence (measured with flow cytometry) from a JLat 9.2 bulk culture, after a 24-h tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) treatment. TNF-α is a potent activator of the HIV-1 LTR promoter and was administered at 10 ng/mL concentration. The histogram shows that there is a distinct bimodal distribution of response to TNF-α perturbation within a clonal population of JLat.

(D) We propose the following Luria-Delbrück experimental design to investigate if single-cell JLat response to TNF-α perturbation is random or heritable. A clonal population of JLat 9.2 was sorted into single cells using FACS and cultured individually into colonies. The colonies were subject to 10 ng/mL of TNF-α and the percentage of reactivated cells was measured using flow cytometry after 24 h of treatment. If JLat responds to TNF-α randomly, their responsiveness to TNF-α is determined at the time of TNF-α addition and thus would show low colony-to-colony variation. In contrast, if the response is heritable, then colony behaviors would be influenced by the parent cell resulting in large variations between colonies.

(E) The distribution of reactivation percentage would be centered on the unsorted average if the response is random, whereas the heritable model will result in a wide, skewed distribution for reactivation percentage across colonies.

(F) Histogram of reactivation percentage of 14 different JLat 9.2 colonies after a 24-h TNF-α treatment. Colonies were cultured for 5 weeks after FACS and were grown from single cells sorted from a bulk JLat 9.2 clonal population. The resulting distribution coincides with the heritable response prediction and confirms that JLat cells possess heritable memory of responsiveness to TNF-α perturbation. Inset: The noise in percent reactivation (quantified using the coefficient of variation CV) is significantly higher than the control noise floor as measured by fluctuations in percent reactivation across unsorted JLat populations (p < 0.005). Error bars in the inset represent the standard error of CV.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Full control of the latent cell reservoir with small molecules, either by reactivation or silencing, requires a precise understanding of whether latent cells undergoing clonal expansion (Murray et al., 2016) have memory of their parent cell's responsiveness to treatments. In this context one can envision two different mechanisms of HIV-1 reactivation: (1) a random model where individual cells reactivate purely stochastically owing to noise in post-exposure signaling and viral gene expression (Singh et al., 2010; Singh and Weinberger, 2009; Dar et al., 2012; Burnett et al., 2009; Chavali et al., 2015); (2) an alternative heritable model where reactivation is a deterministic function of an underlying cell state (for example, HIV-1 promoter's epigenetic signature) just prior to LRA exposure. Despite its importance for understanding reactivation dynamics of the latent cell population, it is currently unknown which of the two cases, random response versus nonrandom heritable response, occurs in T cells latently infected with HIV-1.

To discriminate between the random versus heritable model we apply the Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test on a cell line model of HIV-1 latency (Figures 1B and 1C). More specifically, single cells are isolated from a clonal cell population having a single copy of the latent provirus at a unique integration site. Each single cell is expanded into a colony, and colony-to-colony fluctuations in the fraction of reactivating cells are quantified after LRA exposure (Figure 1D). In the random model, each individual cell has the same probability of reactivation, in which case the number of reactivating cells follows a binomial distribution. A straightforward calculation shows that, for the random model, the colony-to-colony fluctuations in the fraction of reactivating cells (as quantified using the coefficient of variation) is , where N is the number of cells in the colony. Thus, for a sufficiently large N, the variations across colonies will be minimal, with each colony reactivating to the same frequency as the original clonal population. In the heritable model, the state of the single cell is propagated across generations, i.e., a more LRA-responsive single cell leads to a more responsive colony. This memory of the starting cell state in the expanded population drives considerable colony-to-colony fluctuations in the heritable model (Figure 1E). We develop a mathematical modeling framework to predict colony-to-colony differences for a transiently heritable cell state and systematically couple them to experimentally measured fluctuations to elucidate mechanisms regulating HIV-1 reactivation.

Results

Responsiveness of HIV latency reversal to external stimulus displays heritability

To test which of the two types of response memory occurs in a latent cell population we utilized and cultured a known Jurkat latency model of HIV-1 (JLat, Figure 1B) (Jordan et al., 2003). This model consists of a Jurkat T cell population latently infected with a full-length HIV-1 construct. The construct contains a deletion of env and a replacement of nef reading frame with GFP. JLat 9.2, a clonal cell population with a single HIV-1 integration site, was selected for our experiments (Jordan et al., 2003). Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) potently activates transcription of the HIV-1 LTR promoter through its nuclear factor κB binding sites (Malinin et al., 1997) and has been used for latency reversal assays on JLat cell lines in the previous literature at 10 ng/mL (Jordan et al., 2003; Bohn-Wippert et al., 2017; Dar et al., 2014). A typical response to TNF-α addition after 24h treatment is shown in Figure 1C. Here the bimodal distribution of identical cells shows a lower GFP peak of a cell subpopulation irresponsive to TNF-α and a higher GFP peak of cells that reactivate in response to TNF-α treatment (Figure 1C) (Weinberger et al., 2005, 2008). The percentage of reactivated cells measured using flow cytometry is quantified by the number of cells that turn on past a gating threshold divided by the total number of cells (Figures S2 and S3) and is ≈20% for JLat 9.2 at 10 ng/mL TNF-α induction.

To perform the Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test, we used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to sort single cells into 96-well plates and grow out JLat single-cell colonies (transparent methods, Figure S1). Of the cells that survived and expanded, 14 JLat 9.2 single-cell colonies were grown out over 5 weeks and subsequently treated with TNF-α for 24 h to determine the fraction of reactivating cells (% reactivation) (transparent methods, Figure S2). It is intriguing that the data reveal a skewed distribution for the % reactivation across colonies (Figure 1F) with a high coefficient of variation (CV) of ≈0.75. The parent JLat 9.2 population shows a 20% reactivation, whereas 4 of 14 single-cell colonies reactivate less than 10% and 2 colonies reactivate greater than 40%. The skewed distribution observed at week 5 closely resembles one expected from a nonrandom heritable response model (Figures 1E and 1F). Next, we quantified the biological lower limit of noise in this assay, by measuring the % reactivation in unsorted JLat 9.2 populations over an 8-week period (Figure 2A, black dots). The CV of week-to-week fluctuations in these unsorted populations was determined to be ≈ 0.35 and represents the control noise floor of the fluctuation test. The significantly higher fluctuations in the % reactivation across single-cell colonies (CV ≈ 0.75) as compared with the control noise floor (Figure 1F; inset, p < 0.005) rules out the random response model but is consistent with a heritable cell state regulating cellular responsiveness to TNF-α.

Figure 2.

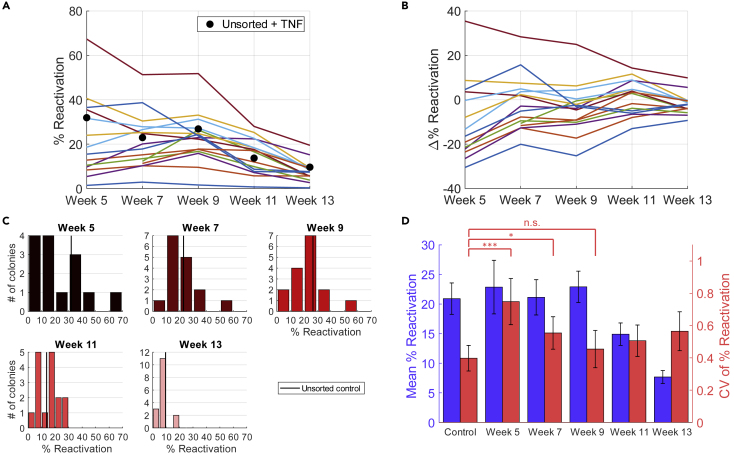

Experimental results from long-term culturing of single-cell JLat colonies reveal a transient heritable response to TNF-α perturbation

(A and B) (A) Reactivation percentage of each colony across weeks 5–13 after TNF-α exposure of 24 h, tested biweekly. Two colonies did not reach experimentally feasible concentrations at week 5 and were included starting from week 7. Black dots represent the control values, measured by exposing the unsorted culture to the same TNF-α treatment for 24 h. The colonies gradually moved closer toward the unsorted control as culturing time progressed. This trend is more clearly represented in (B) where the difference in reactivation percentage between each colony and the control, Δ% Reactivation, is visualized. The approach toward unsorted control is demonstrated by the bundling of colony-wise response around 0 at later time points.

(C) Histogram of reactivation percentage of single-cell colonies from each week's measurement. Week 5 has a total of 14 colonies, whereas the remaining weeks have 16. Unsorted control average is shown as black vertical lines. Bin size for weeks 5, 7, and 9 was set to 10, whereas for weeks 11 and 13 it was set to 5 for better resolution. The histograms also show the convergence of colony-wise behavior toward the unsorted control.

(D) Bar plot of the colony-wise mean reactivation percentage (blue) and colony-wise mean CV (coefficient of variation squared) of reactivation percentage (red). Mean % reactivation values showed an overall decreasing trend as culture time went on, whereas mean CV of % reactivation decreased for the first 5 weeks before reaching a plateau in weeks 11 and 13. The control value is a pooled average of all unsorted + TNF-α treatment values across the 5 time points. Bar heights and error bars represent bootstrapped mean and standard error. Levels of significance are indicated as n.s. (p ≥ 0.1), one star (∗, 0.1 > p ≥ 0.05) or three stars (∗∗∗, p < 0.01). p Values were calculated using bootstrapping. See transparent methods for details on statistics.

See also Figures S5–S7 for alternative gating strategies.

The cell outgrowth assay followed by activator treatment reveals that JLat 9.2 cells exhibit nonrandom heritable memory with respect to TNF-α activation. If the cell state dictating HIV-1 reactivation is transient, then the fluctuations in the % reactivation should decay over time and reach the noise floor. To determine the timescale of this noise relaxation, we measured TNF-α response across 16 single-cell colonies (14 colonies at week 5 plus 2 additional colonies that grew at week 7) every 2 weeks starting from week 5 (Figure 2A). The low number of colonies is due to the limited survivability after single-cell FACS of Jurkat cells; of 384 sorted single cells, only 16 were able to proliferate into colonies. The reactivation level of the parental unsorted JLat 9.2 cell population was acquired to compare colony reactivation with unsorted reactivation. In brief, the unsorted JLat 9.2 population was cultured in duplicate and cells were measured by flow cytometry every 2 weeks after 24-h TNF-α treatments. For each time point, the mean of two JLat 9.2 unsorted populations was acquired. Unsorted % reactivation drifted from about 32% in week 5 to about 12% in week 13 (black dots, Figure 2A). The difference between each colony-wise % reactivation and the unsorted (Δ% Reactivation) decreased as culture time went on (Figures 2B and 2C). As expected for a transiently heritable cell state, the colony-to-colony fluctuations in the % reactivation attenuate over time, starting from a wide, skewed distribution at week 5, to a narrow distribution at week 13 (Figure 2C). The CV of the % reactivation at weeks 5 and 7 is significantly higher than the control noise floor but drops to the noise floor starting from week 9. As also observed in the unsorted populations, the mean % reactivation from week 11 and week 13 are significantly lower than the control mean (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 respectively), whereas weeks 5–9 do not show significant changes compared with the control (Figure 2D). Careful analysis shows that the results of Figure 2 are insensitive to the gating strategy used (transparent methods, Figures S5–S7).

Mathematical modeling of the transient heritable memory

To systematically characterize the hidden memory regulating HIV reactivation from the fluctuation test data, we developed a mathematical model of clonal expansion where single cells switch between an irresponsive and responsive state (Figure 3A). The states are transiently heritable, i.e., the state is inherited for some generations before it is lost (Figure 2A and transparent methods, Figure S3). Let p(t) denote the reactivation probability of an individual cell at time t, and is assumed to switch between two values: p(t) = 0 (irresponsive state) and p(t) = 1 (fully responsive state). Cells in the irresponsive state become responsive with rate k, and responsive cells become irresponsive with rate γ. In the stochastic formulation of the model, the time spent in responsive and irresponsive states is exponentially distributed with means 1/γ and 1/k, respectively. These switching rates yield the following steady-state mean and noise levels of p(t) (see transparent methods for details on model description and analysis):

| (Equation 1) |

where the angular brackets p denote the expected value and is the fraction of responsive cells in the original unsorted population.

Figure 3.

A transient cell state governs HIV-1 exit from latency

(A) Schematic of the stochastic model where prior to TNF-α exposure, individual cells reversibly switch between a TNF-α irresponsive and a responsive state. Self arrows represent proliferation of cells with the mother cell state being inherited by daughters. A sample realization of cells switching states over time is shown below.

(B) The predicted colony-to-colony fluctuations in the fraction of reactivating cells (as measured by the coefficient of variation CV) increases for longer periods in the responsive state assuming a fixed 25% reactivation averaged across colonies. Plots are shown for different times of TNF-α exposure.

(C) Predicted distribution of the fraction of reactivating cells across colonies after 5 weeks of growth for different average times in the responsive state. Distributions are obtained by using a beta distribution with an average 25% reactivation and noise as given by Equation (2).

(D) Measured colony-to-colony fluctuations (with error bars showing standard error) starting from 5 to 13 weeks (black circles corresponding to data from Figure 2D). The fluctuations are considerably high at the initial 5-week time point (CV = 75%) and then gradually decrease to the noise floor. Note that the 11- and 13-week timepoints have been corrected for the mean as discussed in the main text. Model predicted CV as per Equation Equation (4) are shown assuming a noise floor CVNF= 0.35 for different average times in the responsive state.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

Having defined stochastic transitions between the two cell states, we next model the clonal expansion in the Luria-Delbrück experiment. A single cell is chosen from the original population at time t = 0, and this initial cell is either in the responsive state with probability or in the irresponsive state with probability . Starting from a single cell, colony size increases exponentially over time with cell-doubling times assumed to be the same irrespective of the underlying state (transparent methods, Figure S4). As the lineage expands, single cells reversibly switch between states and the mother cell state is inherited by both daughters upon mitosis. Considering exposure to TNF-α at time t, our analysis predicts the CV of the colony-to-colony fluctuations in % reactivation

| (Equation 2) |

to decay exponentially with rate k+γ (see transparent methods for details). Note that, if reactivation is done at t = 0, then

| (Equation 3) |

is consistent with the Bernoulli reactivation outcome for the initial cell. Considering ≈ 20% responsive cells in the original population, this would correspond to CV(0) ≈ 2. As expected, colony-to-colony fluctuations are high when the reactivation is done early in the lineage expansion as the memory of the initial cell is retained. Over time, these fluctuations decay to zero with each colony equilibrating to the same steady-state % reactivation . For a fixed time of TNF-α exposure, colony-to-colony fluctuations are enhanced by slower switching between states (Figures 3B and 3C).

For fitting the predicted CV to data, we modify (2)

| (Equation 4) |

to include a noise floor as quantified using fluctuations in % reactivation across unsorted populations. Given an a priori knowledge of, fitting (4) to experimentally measured colony-to-colony fluctuations at different times of exposure infers the decay rate k+γ. Note from (1) that itself is determined by the ratio of k and γ. Thus, combining knowledge of both with the inferred decay rate allows both switching rates to be uniquely estimated. Before fitting (4) to the measured colony-to-colony fluctuations, recall that the average % reactivation of single-cell colonies was significantly reduced at week 11 and week 13 (Figure 2D). For this reason, the measured CV in % reactivation at these time points is likely higher than if the mean % reactivation had remained constant at 20%. Assuming CV2 to be inversely proportional to the mean % reactivation (as in a binomial distribution), we readjust the CV values at weeks 11 and 13 assuming a 20% mean reactivation. An alternative approach is to simply exclude data points at weeks 11 and 13, and both approaches yield statistically similar parameter estimates. Fitting model-predicted CV to measured fluctuations reveals the noise decay rate k+γ to be 0.24 ± 0.1 per week (Figure 3D) where the ± denotes the 95% confidence interval as estimated using bootstrapping. Based on a ≈ 20%, this corresponds to single cells being in the response state for 6.3 ± 2.6 weeks. A key assumption in this calculation is that sorted single cells can instantly start proliferating. However, the stress of single-cell sorting can create a lag phase before sorted cells can execute normal cellular proliferation. A quick analysis based on cell densities at different times of the colony expansion points to a lag phase of around 2–3 weeks (see details in the supplementary information), and accounting for this delay, reduces the average time cells stay in the response state to be 2.9 ± 1.2 weeks. Given that only 20% of cells are TNF-α responsive yields the average time a cell is in the irresponsive state to be 12 ± 4.5 weeks.

Discussion

The Luria-Delbrück experiment, also called the "Fluctuation Test," introduced over 75 years ago, demonstrated that genetic mutations arise randomly in the absence of selection—rather than in response to selection—and led to a Nobel Prize (Luria and Delbruck, 1943). Combining this classical fluctuation test with mathematical modeling we have developed a novel methodology to infer timescales of reversible switching between cellular states that exist within the same clonal population. In essence, slower switching rates lead to higher colony-to-colony fluctuations in the assayed phenotype (for example, the % HIV-1 reactivation across colonies) (Figures 3B and 3C). The key advantage of this method is that it is general enough to be applied to any proliferating cell type and only involves making a single endpoint measurement. This is especially important for scenarios where a measurement involves killing the cell, and hence the state of the same cell cannot be measured at different time points. Along these lines, the fluctuation test has had tremendous recent success in deciphering stochastic transitions between drug-tolerant states underlying cancer drug resistance, where drug exposure leads to heterogeneous single-cell responses between cell death and survival (Shaffer et al., 2017, 2019).

We leveraged the fluctuation test to address a fundamental question in HIV-1 latency: is the reactivation of the latent provirus upon LRA exposure purely stochastic or a deterministic function of an underlying cell state (Figure 1D). Using the Jurkat T cell line model of HIV-1 latency (JLat 9.2), containing a modified full-length provirus that expresses GFP upon reactivation (Figures 1B and 1C) (Jordan et al., 2003), the fluctuation data strongly point to the heritable model—cells switch between responsive and irresponsive states, and the cell state at the time of TNF-α exposure determines the all-or-none reactivation decision. Remarkably, these states are transiently inherited across generations with a timescale of months (Figure 3D). This point is exemplified by the fact that even after 5 weeks of clonal expansion there are significant colony-to-colony differences in TNF-α responsiveness (Figure 1F) and these differences attenuate over time to baseline levels at ≈10 weeks (Figure 2D). Although we were able to distinguish between random and heritable response for the Jurkat latency model of HIV-1, systems following the heritable model but with switching rates exceeding the sampling rate of our experimental design will impose difficulties in this task and would require more advanced techniques to tease out the details. Despite focusing on JLat 9.2, a single JLat clonal integration site, we predict that the heritable model is conserved across integrations but with different timescales (Pearson et al., 2008). The long timescales of switching involved here imply epigenetic mechanisms at play, and indeed, prior work has shown that DNA methylation patterns at the HIV promoter critically regulate provirus reactivation (Kauder et al., 2009; Blazkova et al., 2009; Bednarik et al., 1990). Moreover, RNA-induced epigenetic silencing using promoter-targeted shRNAs has been shown to suppress HIV-1 reactivation from latency in JLat 9.2 cells (Mendez et al., 2018). Of interest, recently constructed high-resolution maps of histone marks in human cells reveal stochastic switching between fully methylated and unmethylated states of DNA at several gene loci (Onuchic et al., 2018). Taken together, these results suggest that dynamic, but slow, turnovers of epigenetic signatures at the HIV-1 promoter may provide a mechanism for switching between LRA-responsive and irresponsive states.

The measured colony-to-colony fluctuations in the fraction of reactivating cells over time reveals that cells can remain irresponsive to TNF-α for several months before switching to a responsive state. Cells in the responsive state return to become irresponsive after a few weeks. This result has important implications for designing therapies to purge the latent reservoir (Deeks, 2012; Spina et al., 2013; Shirakawa et al., 2013) and suggests that a strategy with multiple LRA treatments spaced over several months may be more effective than single-round, single-LRA treatments (Ho et al., 2013; Dar et al., 2014; Xing and Siliciano, 2013). Consistent with the idea, previous work has shown that periodic treatments can reactivate more latent virus (Ho et al., 2013). While this contribution has focused on HIV-1 reactivation in Jurkat T-cells using TNF-α induction, it raises intriguing questions on the generality of transient memory states in the context of other LRAs and cell types. For example, fluctuation-based assays can be done at different proviral integration sites in Jurkat T-cells, at different TNF-α dosage, in other cell types (for example, myeloid models of HIV-1 latency), and, most importantly, using a variety of other LRAs, such as HDAC inhibitors (Archin et al., 2012; Shirakawa et al., 2013; Manson Mcmanamy et al., 2014), synergistic combinations of PKC agonists (Williams et al., 2004), DNA cytosine methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2′deoxycytidine (Blazkova et al., 2009; Kauder et al., 2009), and many others reported in the literature. Such studies will be essential to decipher cell-state signatures in the latent reservoir that will guide efforts for HIV-1 treatment. Alternatively, the finding that cells can remain irresponsive to TNF-α for several months before switching to a responsive state may also have implications for additional treatment strategies. The “block and lock” strategy involves silencing HIV-1 expression into a prolonged latent state (Vansant et al., 2020; Kessing et al., 2017). If the responsiveness of HIV-1 to silencing drugs is governed by the same principle, the responsiveness timescale quantified here may guide the treatment design needed for latency promoting agent administration, in both composition and timing.

Limitations of the study

This study includes two limitations related to HIV virology. First, the downside of throughput limitations in the growth and handling of clonal populations limited this study to a single integration site. Further research covering a broad spectrum of HIV viral integration sites will provide a range of transient memory timescales that are closer to the in vivo setting. Second, the fluctuation test required the isolation and growth of individual cells isolated from a clonal Jurkat latency model of HIV. Ideally, this experiment would be performed on a primary cell model of latency but resting CD4+ T cells expansion is limited to very slow homeostatic proliferation, which may prove challenging for setting up such an experiment.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Roy Dar (roydar@illinois.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze datasets/code.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

A.S. acknowledges support from NIH grants 5R01GM124446 and 5R01GM126557. Y.L. and R.D.D. acknowledge support from NIH K22 AI120746 and NSF CAREER 1943740. H.S. acknowledges support provided by the Cancer Scholars Program at UIUC.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., A.S., and R.D.D.; Methodology, Y.L., A.S., and R.D.D.; Formal Analysis, Y.L. and A.S.; Investigation, Y.L.; Writing, Y.L., A.S., and R.D.D.; Funding Acquisition, A.S. and R.D.D.; Resources, A.S. and R.D.D.; Supervision, A.S. and R.D.D.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 23, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102291.

Contributor Information

Abhyudai Singh, Email: absingh@udel.edu.

Roy D. Dar, Email: roydar@illinois.edu.

Supplemental information

References

- Archin N.M., Liberty A.L., Kashuba A.D., Choudhary S.K., Kuruc J.D., Crooks A.M., Parker D.C., Anderson E.M., Kearney M.F., Strain M.C. Administration of vorinostat disrupts HIV-1 latency in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Nature. 2012;487:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarik D.P., Cook J.A., Pitha P.M. Inactivation of the HIV LTR by DNA CpG methylation: evidence for a role in latency. EMBO J. 1990;9:1157–1164. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazkova J., Trejbalova K., Gondois-Rey F., Halfon P., Philibert P., Guiguen A., Verdin E., Olive D., Van Lint C., Hejnar J., Hirsch I. CpG methylation controls reactivation of HIV from latency. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000554. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn-Wippert K., Tevonian E.N., Megaridis M.R., Dar R.D. Similarity in viral and host promoters couples viral reactivation with host cell migration. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett J.C., Miller-Jensen K., Shah P.S., Arkin A.P., Schaffer D.V. Control of stochastic gene expression by host factors at the HIV promoter. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000260. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavali A.K., Wong V.C., Miller-Jensen K. Distinct promoter activation mechanisms modulate noise-driven HIV gene expression. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17661. doi: 10.1038/srep17661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillo A.R., Sobolewski M.D., Bosch R.J., Fyne E., Piatak M., Jr., Coffin J.M., Mellors J.W. Quantification of HIV-1 latency reversal in resting CD4+ T cells from patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2014;111:7078–7083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402873111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahabieh M.S., Battivelli E., Verdin E. Understanding HIV latency: the road to an HIV cure. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015;66:407–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-092112-152941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar R.D., Hosmane N.N., Arkin M.R., Siliciano R.F., Weinberger L.S. Screening for noise in gene expression identifies drug synergies. Science. 2014;344:1392–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.1250220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar R.D., Razooky B.S., Singh A., Trimeloni T.V., Mccollum J.M., Cox C.D., Simpson M.L., Weinberger L.S. Transcriptional burst frequency and burst size are equally modulated across the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;109:17454–17459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213530109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks S.G. HIV: shock and kill. Nature. 2012;487:439–440. doi: 10.1038/487439a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y.C., Shan L., Hosmane N.N., Wang J., Laskey S.B., Rosenbloom D.I., Lai J., Blankson J.N., Siliciano J.D., Siliciano R.F. Replication-competent noninduced proviruses in the latent reservoir increase barrier to HIV-1 cure. Cell. 2013;155:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.B., Mueller S., O'connor R., Rimpel K., Sloan D.D., Karel D., Wong H.C., Jeng E.K., Thomas A.S., Whitney J.B. A subset of latency-reversing agents expose HIV-infected resting CD4+ T-cells to recognition by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005545. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.B., O'connor R., Mueller S., Foley M., Szeto G.L., Karel D., Lichterfeld M., Kovacs C., Ostrowski M.A., Trocha A. Histone deacetylase inhibitors impair the elimination of HIV-infected cells by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A., Bisgrove D., Verdin E. HIV reproducibly establishes a latent infection after acute infection of T cells in vitro. EMBO J. 2003;22:1868–1877. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauder S.E., Bosque A., Lindqvist A., Planelles V., Verdin E. Epigenetic regulation of HIV-1 latency by cytosine methylation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000495. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing C.F., Nixon C.C., Li C., Tsai P., Takata H., Mousseau G., Ho P.T., Honeycutt J.B., Fallahi M., Trautmann L. In vivo suppression of HIV rebound by didehydro-cortistatin A, a "Block-and-Lock" strategy for HIV-1 treatment. Cell Rep. 2017;21:600–611. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Bohn-Wippert K., Pazerunas P.J., Moy J.M., Singh H., Dar R.D. Screening for gene expression fluctuations reveals latency promoting agents of HIV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021;118(11) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012191118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luria S.E., Delbruck M. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics. 1943;28:491–511. doi: 10.1093/genetics/28.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinin N.L., Boldin M.P., Andrei K.V., Wallach D. MAP3K-related kinase involved in NF-KB induction by TNF, CD95 and IL-1. Nature. 1997;385:540–544. doi: 10.1038/385540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson Mcmanamy M.E., Hakre S., Verdin E.M., Margolis D.M. Therapy for latent HIV-1 infection: the role of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2014;23:145–149. doi: 10.3851/IMP2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez C., Ledger S., Petoumenos K., Ahlenstiel C., Kelleher A.D. RNA-induced epigenetic silencing inhibits HIV-1 reactivation from latency. Retrovirology. 2018;15:67. doi: 10.1186/s12977-018-0451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A.J., Kwon K.J., Farber D.L., Siliciano R.F. The latent reservoir for HIV-1: how immunologic memory and clonal expansion contribute to HIV-1 persistence. J. Immunol. 2016;197:407–417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuchic V., Lurie E., Carrero I., Pawliczek P., Patel R.Y., Rozowsky J., Galeev T., Huang Z., Altshuler R.C., Zhang Z. Allele-specific epigenome maps reveal sequence-dependent stochastic switching at regulatory loci. Science. 2018;361:eaar3146. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R., Kim Y.K., Hokello J., Lassen K., Friedman J., Tyagi M., Karn J. Epigenetic silencing of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transcription by formation of restrictive chromatin structures at the viral long terminal repeat drives the progressive entry of HIV into latency. J. Virol. 2008;82:12291–12303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01383-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen T.A., Lewin S.R. Shocking HIV out of hiding: where are we with clinical trials of latency reversing agents? Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2016;11:394–401. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman D.D., Margolis D.M., Delaney M., Greene W.C., Hazuda D., Pomerantz R.J. The challenge of finding a cure for HIV infection. Science. 2009;323:1304–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1165706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruelas D.S., Greene W.C. An integrated overview of HIV-1 latency. Cell. 2013;155:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., Siliciano R.F. Targeting the latent reservoir for HIV-1. Immunity. 2018;48:872–895. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer S.M., Dunagin M.C., Torborg S.R., Torre E.A., Emert B., Krepler C., Beqiri M., Sproesser K., Brafford P.A., Xiao M. Rare cell variability and drug-induced reprogramming as a mode of cancer drug resistance. Nature. 2017;546:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature22794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer S.M., Emert B.L., Reyes-Hueros R., Cot C., Harmange G., Sizemore A.E., Gupte R., Torre E., Singh A., Bassett D.S., Raj A. Memory sequencing reveals heritable single cell gene expression programs associated with distinct cellular behaviors. bioRxiv. 2019:379016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan L., Deng K., Shroff N.S., Durand C.M., Rabi S.A., Yang H.C., Zhang H., Margolick J.B., Blankson J.N., Siliciano R.F. Stimulation of HIV-1-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes facilitates elimination of latent viral reservoir after virus reactivation. Immunity. 2012;36:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakawa K., Chavez L., Hakre S., Calvanese V., Verdin E. Reactivation of latent HIV by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siliciano R.F., Greene W.C. HIV latency. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011;1:a007096. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Razooky B., Cox C.D., Simpson M.L., Weinberger L.S. Transcriptional bursting from the HIV-1 promoter is a significant source of stochastic noise in HIV-1 gene expression. Biophysical J. 2010;98:L32–L34. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Weinberger L.S. Stochastic gene expression as a molecular switch for viral latency. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009;12:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina C.A., Anderson J., Archin N.M., Bosque A., Chan J., Famiglietti M., Greene W.C., Kashuba A., Lewin S.R., Margolis D.M. An in-depth comparison of latent HIV-1 reactivation in multiple cell model systems and resting CD4+ T cells from aviremic patients. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003834. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansant G., Bruggemans A., Janssens J., Debyser Z. Block-and-lock strategies to cure HIV infection. Viruses. 2020;12:84. doi: 10.3390/v12010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger L.S., Burnett J.C., Toettcher J.E., Arkin A.P., Schaffer D.V. Stochastic gene expression in a lentiviral positive-feedback loop: HIV-1 Tat fluctuations drive phenotypic diversity. Cell. 2005;122:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger L.S., Dar R.D., Simpson M.L. Transient-mediated fate determination in a transcriptional circuit of HIV. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:466–470. doi: 10.1038/ng.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.A., Chen L.F., Kwon H., Fenard D., Bisgrove D., Verdin E., Greene W.C. Prostratin antagonizes HIV latency by activating NF-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42008–42017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing S., Siliciano R.F. Targeting HIV latency: pharmacologic strategies toward eradication. Drug Discov. Today. 2013;18:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbato J.M., Purves H.V., Lewin S.R., Rasmussen T.A. Between a shock and a hard place: challenges and developments in HIV latency reversal. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019;38:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze datasets/code.