Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: AI-2, autoinducer-2; CCR, carbon catabolite repression; LBD, ligand binding domain; Pi, inorganic phosphate; SBP, solute binding protein; TCS, two-component system

Keywords: Solute binding protein, Chemoreceptor, Sensor kinase, Indirect binding, Bacterial signal transduction, Sensing

Abstract

The solute binding proteins (SBPs) of prokaryotes are present in the extracytosolic space. Although their primary function is providing substrates to transporters, SBPs also stimulate different signaling proteins, including chemoreceptors, sensor kinases, diguanylate cyclases/phosphodiesterases and Ser/Thr kinases, thereby causing a wide range of responses. While relatively few such systems have been identified, several pieces of evidence suggest that SBP-mediated receptor activation is a widespread mechanism. (1) These systems have been identified in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and archaea. (2) There is a structural diversity in the receptor domains that bind SBPs. (3) SBPs belonging to thirteen different families interact with receptor ligand binding domains (LBDs). (4) For the two most abundant receptor LBD families, dCache and four-helix-bundle, there are different modes of interaction with SBPs. (5) SBP-stimulated receptors carry out many different functions. The advantage of SBP-mediated receptor stimulation is attributed to a strict control of SBP levels, which allows a precise adjustment of the systeḿs sensitivity. We have compiled information on the effect of ligands on the transcript/protein levels of their cognate SBPs. In 87 % of the cases analysed, ligands altered SBP expression levels. The nature of the regulatory effect depended on the ligand family. Whereas inorganic ligands typically downregulate SBP expression, an upregulation was observed in response to most sugars and organic acids. A major unknown is the role that SBPs play in signaling and in receptor stimulation. This review attempts to summarize what is known and to present new information to narrow this gap in knowledge.

1. Introduction

Bacteria need to take up compounds from the extracytosolic space in order to survive. To this end, bacteria have evolved a variety of transmembrane transporters that permit the specific transport of a variety of compounds. Several transporter families, like ATP-binding cassette (ABC), tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP), and tripartite tricarboxylate transporters (TTTs) employ solute binding proteins (SBPs) to capture the transport substrate in the extracytosolic space and to present it to the transmembrane receptor permeases [1]. These proteins thus play a central role in defining the substrate specificity of the transporter.

SBPs are found in all kingdoms of life [1] and form a superfamily composed of many families, as defined by different domain profiles in the Pfam [2] and InterPro [3] databases. Whereas SBPs in Gram-negative bacteria are present as diffusible proteins in the periplasm, in Gram-positive bacteria and archaea they are tethered to the external face of the cytoplasmic membrane [4]. Although SBPs vary largely in size, from 20 to 65 kDa, they share the same overall topology that consists of two lobes linked by a hinge region [5]. The transport substrate binds to the interface of both lobes, a process that frequently induces significant structural rearrangements [6], [7].

Other major constituents of prokaryotic membranes are signal transduction receptors [8]. The function of these proteins is to sense extracytoplasmic signals and to initiate a cellular response leading to a more optimal adaptation to a given environmental condition. The most abundant signal transduction receptors are sensor kinases, chemoreceptors, diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases, adenylate cyclases, extracytosolic function sigma factors as well as Ser/Thr kinases and phosphatases [8]. Typically, these receptors are transmembrane proteins that contain an extracytoplasmic sensor or ligand binding domain (LBD) that is flanked by two transmembrane regions. Signal binding to the LBD creates a conformational change that is transmitted to the cytosolic part of the receptor to induce signaling cascades that lead to the final cellular response. Transmembrane signal transduction receptors mediate a variety of different responses. For example: (i) Sensor kinases form two component systems (TCSs) with response regulators that primarily regulate transcription [9]; (ii) Chemoreceptors form part of chemosensory pathways that primarily mediate chemotaxis but were also found to control second messenger levels or type IV pili-based motility [10]; (iii) Diguanylate cyclases/phosphodiesterases and adenylate cyclases, respectively, control the levels of c-di-GMP and cAMP, second messengers that in turn regulate a variety of different cellular processes [11], [12].

Transmembrane receptors employ many different LBD types for signal sensing [13], [14] as exemplified by the 80 different LBD types identified in chemoreceptors [13]. Frequently, a given LBD type is shared by different receptor families [14], [15], which is consistent with the notion that LBDs are modules that can be recombined with different signaling proteins. Although the function of many transmembrane signal transduction receptors has been identified by phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses of the corresponding bacterial mutants, the signals recognized by many of these receptors remain unknown [16], [17]. The scarcity of information about the signals recognized by these receptors represents a major research need in the field because this knowledge is indispensable to fully understand the corresponding regulatory circuit [18]. Over the last years, significant progress in this area has been made by high-throughput ligand screening using individual LBDs [18], [19]. However, in a number of cases screening did not identify any ligand, which is consistent with the notion that some LBDs may not bind signals directly. A possible explanation is that some LBDs interact with signal-loaded SBPs. There are a number of examples, reviewed in this article, in which signal transduction receptors are stimulated by an interaction with an SBP. Some of these SBPs thus carry out a double function, as they may be involved in transport and signal transduction. Since cellular SBP levels are frequently subject to tight control, it has been proposed that this mechanism offers the possibility of coordinating different, but physiologically related, processes such as transport and chemotaxis [20]. The study of SBP-activated chemoreceptors has shown that the overall responses are highly sensitive to SBP levels, thus permitting a better control of the sensitivity to specific ligands in response to their nutrient environment and to coordinate chemotaxis with ligand transport [21]. However, the cost for this capacity is the much narrower dynamic response range of SBP-stimulated receptors as compared to those that recognize signal molecules directly [21].

Here, we review the data available on SBP-stimulated signal transduction receptors and compile information on the effect of signal molecules on the expression of their cognate SBPs. SBP-stimulated receptors showed a wide phylogenetic spread, and these systems reveal a significant diversity in the structure of receptor LBDs as well as SBPs, suggesting that indirect sensing is a rather widespread mechanism. We propose that the relatively low number of characterized SBP-stimulated systems is the consequence of the technical complexity of identifying such systems rather than their low abundance.

2. Universality and diversity of SBP interactions with bacterial sensor proteins

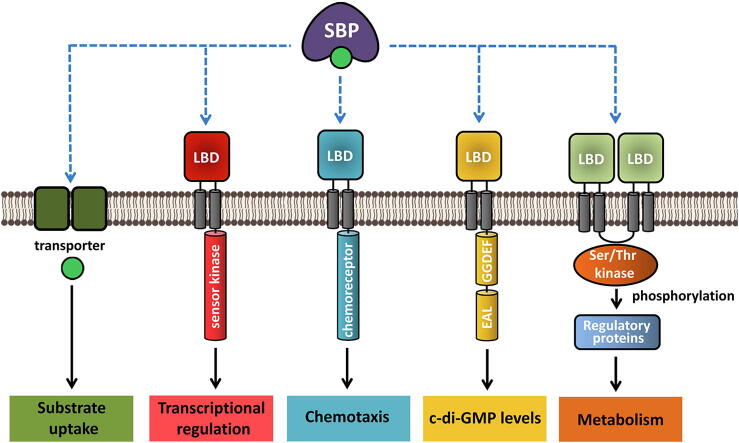

We have compiled the information on bacterial receptors that are stimulated by the binding of SBPs in Table 1. There was a significant phylogenetic spread of the corresponding organisms including α-, β-, γ- and ε-Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes as well as Archaea (Table 1). The genes encoding SBPs are often found in the vicinity of genes encoding the cognate transporters or signal transduction receptors (Table 1, Table 2). Remarkably, genes encoding SBPs that interact with chemoreceptors are primarily found in the vicinity of genes encoding transporters, whereas those for SBPs that stimulate sensor kinases are associated with signaling genes (Table 1). Receptors belong to four families, namely chemoreceptors, sensor kinases, GGDEF-EAL domain-containing diguanylate cyclases/phosphodiesterases, and Ser/Thr kinases (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Direct or indirect evidence for the stimulation of different signal transduction receptors by SBPs.

| Signal transduction receptor | Solute binding protein | PDB | Ref. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | UniProt | Species | Phylogenetic category | LBD family (Pfam/InterPro) | Name/Gene associated witha | UniProt (size in kDa)b | Family Pfam/InterPro | Ligands (KD in µM) | ||

| Chemoreceptors | ||||||||||

| Tar | P76301 | E. coli | γ-Proteobacteria | TarH (PF02203) | MBP maltose binding protein/Ta | P0AEX9 (43) | SBP_bac_8 (PF13416) | D-maltose (1.5) | 2LIG | [26], [40], [126] |

| Tap | P76300 | E. coli | γ-Proteobacteria | TarH (PF 02203) | DppA dipeptide binding protein/Ta | P23847 (60) | SBP_bac_5 (PF00496) | Various dipeptides, (lower nM for Ala-Phe) | 1DPE | [41], [127] |

| Trg | P77448 | E. coli | γ-Proteobacteria | TarH (PF 02203) | GBP galactose binding protein/Ta | P0AEE5 (35) | Peripla_BP_4 (PF13407) | D-galactose (0.13) | 2GBP | [37], [38], [39], [42], [128], [129], [130] |

| RBP Ribose-binding protein/Ta | P02925 (31) | Peripla_BP_4 (PF13407) | D-ribose (0.13) | 2DRI | ||||||

| PotD spermidine binding protein/Ta | P0AFK9 (39) | SBP_bac_8 (PF13416) | Spermidine (3.2) | 1POY | [43], [131] | |||||

| Tsr | P02942 | E. coli | γ-Proteobacteria | TarH (PF 02203) | LsrB/Ta | P76142 (37) | Peripla_BP_4 (PF13407) | Autoinducer-2 | [45], [46] | |

| TlpB | B5Z9N4 | Helicobacter pylori | ε-Proteobacteria | sCache_2 (PF 17200) | AibA/Ta AibB/Ta | B5ZA64 (62) B5Z6J6 (28) | SBP_bac_5 (PF00496) ModA (IPR005950) | Autoinducer-2 Autoinducer-2 | [56] | |

| CtpL | G3XDA8 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | γ-Proteobacteria | HBM (PF 16591) | PstS/Ta | G3XDA8 (34) | PBP_like_2 (PF12849) | Inorganic phosphate (0.009) | 4OMB | [48] |

| PctA | PA4309 | P. aeruginosa | γ-Proteobacteria | dCache (PF 02743) | GltB/Ta & SPa | PA3190 (45) | SBP_bac_1 (PF01547) | Glucose (1.4) | [71] | |

| McpN | PA2788 | PilJ (PF13675) | ||||||||

| BasT | B0R6I4 | Halobacterium salinarum | Archaea | Not annotated (dCache-like) | BasB/SPa | B0R6I5 (41) | Peripla_BP_6 (PF13458) | Val, Ile, Met, Cys | [52], [53] | |

| CosT | B0R6A7 | H. salinarum | Archaea | Not annotated (dCache-like) | CosB/SPa | B0R6A8 (36) | OpuAC (PF04069) | Glycine betaine, choline, carnitine | [53] | |

| Sensor kinases | ||||||||||

| LuxQ | P54302 | Vibrio harveyi | γ-Proteobacteria | LuxQ-periplasm (PF09308) dCache-like | LuxP/SPa | P54300 (41) | Peripla_BP_4 (PF13407) | AI-2 (0.27) | 2HJ9 1ZHH | [29], [132], [133] |

| LytS | A6LW08 | Clostridium beijerinckii | Firmicutes | Not annotated (TarH-like) | XylFII/SPa | A6LW07 (36) | Peripla_BP_4 (PF13407) | D-xylose (0.37) | 5XSJ | [27], [134] |

| TorS | A0A0L8U5J8 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | γ-Proteobacteria | TorS sensor (IPR037952) HBM-like | TorT/SPa | Q87ID2 (37) | Peripla_BP_1 (PF0532) | Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) (74) | 3O1H 3O1I | [28] |

| TorS | P39453 | E. coli | γ-Proteobacteria | TorS sensor (IPR037952) HBM-like | TorT/SPa | P38683 (38) | Peripla_BP_1 (PF0532) | TMAO (150) | [135] | |

| HptS | Q2G1E0 | Staphylococcus aureus | Firmicutes | Not annotated | HptA/SPa | X5DVD1 (37) | SBP_bac_11 (PF13531) | Glucose-6-phosphate (5), Galactose-6-phosphate (10) | 6LKG 6LKH | [30], [136], [137] |

| VirA | P10799 | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | α-Proteobacteria | Not annotated (dCache-like) | ChvEc/Ta | P54082 (38) | Peripla_BP_4 (PF13407) | Arabinose (0.47), Galactose (0.13), Galacturonate (130), Glucuronate (3.1), D-xylose (17.3), D-fucose (2.2) | 3URM | [105], [106], [107] |

| AioS | U6A267 | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | α-Proteobacteria | Not annotated (sCache-like) | AioX/SPa | G8XNW6 (34) | Phosphonate-bd (PF12974) | As(III) (2.4) | 6EU7 | [118], [119] |

| BctE | A0A3T0PKG6 | Bordetella pertussis | β-Proteobacteria | 2CSK_N (PF08521) | BctC/Ta & SPa | A9HVV0 (35) | TctC (PF03401) | Citrate | [89], [104] | |

| ChiS | Q9KUA1 | Vibrio cholerae | γ-Proteobacteria | Not annotated (dCache-like) | CBP/Ta & SPa | Q9KUA3 (63) | SBP_bac_5 (PF00496) | (GlcNAc)2 (1) | 1ZTY | [58], [59] |

| Vibrio harveyi | γ-Proteobacteria | Not annotated (dCache-like) | CBP/Ta & SPa | D0XC84 (63) | SBP_bac_5 (PF00496) | (GlcNAc)2 (0.03) (GlcNAc)3 (0.05) (GlcNAc)4 (0.07) | 5YQW | [138] | ||

| GtrS | PA3191 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | γ-Proteobacteria | Not annotated | GltB/ Ta & SPa | PA3190 (45) | SBP_bac_1 (PF01547) | Glucose (1.4) | [71] | |

| Diguanylate cyclase/c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases (GGDEF/EAL) | ||||||||||

| MbaA | Q9KU26 | Vibrio cholerae | γ-Proteobacteria | Not annotated (dCache-like) | NspS/SPa | Q9KU25 (41) | SBP_bac_8 (PF13416) | Spermidine Norspermidine | [60], [125] | |

| ScrC | Q9AF11 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | γ-Proteobacteria | Not annotated (dCache-like) | ScrB/SPa | Q9AF12 (36) | SBP_bac_3 (PF00497) | S-signal | [139], [140] | |

| Serine/threonine kinase | ||||||||||

| GlnX PknGd | P96258 P9WI73 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Actinobacteria | 4HB_MCP_1 (PF12729) | GlnH/SPa | P96257 (35) | SBP_bac_3 (PF00497) | Asp (5), Glu (15) | 6H1U 6H20 6H2T | [22], [23], [24] |

Genes associated with: T: transporter genes; SP: Signaling protein genes.

Size including signal peptide

ChvE is also involved in chemotaxis; chvE mutants showed strongly reduced chemotaxis to D-galactose, D-glucose, L-arabinose, D-fucose, and D-xylose [141].

The GlnH SBP binds to the transmembrane protein GlnX that interacts on the cytosolic side with the Ser/Thr kinase PknG.

Table 2.

Regulation of the expression of SBPs at the transcriptional and protein levels by different ligand families and environmental cues.

| SBP | Gene/ Gene associated witha | SBP family/Pfam | Species | SBP ligands | Experimental conditions | Fold change | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids and peptides | |||||||

| AatJ | PA1342/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | L-Glu | 5 mM L-Glu vs 5 mM L-Arg | 2.6b | [142] |

| 5 mM D-Glu vs 5 mM L-Arg | 2.2b | ||||||

| AliB | spd_1357/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Oligopeptides | 10 mM Arg vs 0.05 mM Arg | −2.9b | [143] |

| ApbA | spd_0109/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | S. pneumoniae | Arg | 10 mM Arg vs 0.05 mM Arg | −10.1b | [143] |

| ArtI | artI/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | Escherichia coli | Arg, ornithine | 0.6 mM Arg vs no Arg | −3.4b | [121] |

| 5.7 mM Arg vs no Arg | No changec | [144] | |||||

| 5.0 mM ornithine vs no ornithine | No changec | ||||||

| ArtJ | artJ/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | E. coli | Arg | 5.7 mM Arg vs no Arg | Reduced ArtJ levels in the presence of Argc | [144] |

| 0.6 mM Arg vs no Arg | −11.4b/-14.3d | [121] | |||||

| LB medium vs human urine (low Arg) | −16.6e | [145] | |||||

| −4.7b | [146] | ||||||

| Atu2422 | atu2422/Ta | Peripla_BP_6/PF13458 | Agrobacterium fabrum | GABA, L-Pro, L-Ala, L-Val | 1 mM GABA vs no GABA | No changeb | [147] |

| Atu4243 | atu4243/Ta | SBP_bac_8/PF13416 | A. fabrum | GABA | 1 mM GABA vs no GABA | No changeb | [147] |

| DppA | dppA/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | E. coli | Dipeptides | 2% (w/v) casamino acids vs no casamino acids | Reduced DppA levels in the presence of casamino acidsc | [148] |

| Reduced dppA transcript levels in the presence of casamino acidsf | |||||||

| LB medium vs human urine | −4.1b | [146] | |||||

| GltI | gltI/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | E. coli | Glu, Asp | LB medium vs human urine (low Arg) | −3.4b | [146] |

| HisJ | hisJ/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | E. coli | His, Arg | 0.6 mM Arg vs no Arg | −2.5b | [121] |

| 0.6 mM Arg vs no Arg | -2.8d | [121] | |||||

| 0.6 mM His vs no His | No changee | [91] | |||||

| LB medium vs human urine (low Arg) | −2.4b | [146] | |||||

| LAO | argT/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | E. coli | Lys, Arg, ornithine | 0.6 mM Arg vs no Arg | No changed | [121] |

| 4 g/l glucose vs 10 mg/l glucoseq | −2.5g | [108] | |||||

| 1 g/l glucose vs 0.1 g/l glucoseq | −8.3b | [109] | |||||

| LivJ | CJJ81176_1038/Ta | Peripla_BP_6/PF13458 | Campylobacter jejuni | Leu, Ile, Val | CDM medium (0.7 mM L-Leu, 0.2 mM L-Ile, 0.9 mM L-Val) vs CDM-LIV medium (no L-Leu, L-Ile, L-Val) | No changed | [149] |

| LivJ | livJ/Ta | Peripla_BP_6/PF13458 | E. coli | Leu, Ile, Val | 0.1 mg/ml Leu vs no Leu | −25e | [150] |

| LB medium vs human urine | −2.4b | [146] | |||||

| LivK | livk/Ta | Peripla_BP_6/PF13458 | E. coli | Leu | 0.1 mg/ml Leu vs no Leu | −11.4e | [150] |

| MetQ | metQ/Ta | Lipoprotein_9/PF03180 | E. coli | D- and L-Met | 20 µg/ml L-Met vs no L-Met | −2.6e | [151] |

| 20 µg/ml D-Met vs no D-Met | −1.4e | ||||||

| MppA | mppA/- | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | E. coli | Murein peptide L-alanyl-gamma-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelate | 4 g/l glucose vs <10 mg/l glucose, fed-batch conditionsq | −3.0g | [108] |

| OppA | oppA/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | E. coli | Two and five amino acids long peptides | 4 g/l glucose vs <10 mg/l glucose, fed-batch conditionsq | −2.2g | [108] |

| PEB1a | Cj0921c/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | C. jejuni | Asp, Glu | 7.5% (v/v) O2vs 1.9% (v/v) O2q | 5.6h/13.3i | [152] |

| Inorganic nutrients and metal ions (complexed and uncomplexed) | |||||||

| AioX | aioX/SPa | Phosphonate-bd/PF12974 | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | As(III) | 100 µM As(III) vs no As(III) | 3.3j | [98] |

| CeuE | ceuE/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | C. jejuni | Fe(III)-siderophore complexes | Iron replete (40 μM FeSO4) vs iron-chelated | −3.0b | [153] |

| Iron replete (40 μM Fe2(SO4)3) vs iron-chelated | −16.6b | [154] | |||||

| CeuE | HP_1561/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | Helicobacter pylori | Ni-(L-His)2 | 0.5 mM Ni(II) vs no Ni(II) | −6.5j | [96] |

| Non-chelated iron (high iron) vs iron-chelated (low iron)q | −3.5b | [155] | |||||

| FatB | VV2_0842/- | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | Vibrio vulnificus | Ferric vulnibactin | Non-chelated iron (high iron) vs iron-chelated (low iron) | −12.9h | [156] |

| FbpA | NGO0217/Ta | SBP_bac_1/PF01547 | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Fe(III), Ga(III) | Iron replete (100 μM Fe(NO3)3) vs iron-chelated | −6.1j | [95] |

| FecB | fecB/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | E. coli | Fe(III)-citrate | High iron citrate (1 mM citrate, 100 µM Fe2SO4) vs low iron citrate (1 mM citrate, chelated iron) | −3.5e | [157] |

| LB vs bovine milk (most iron is chelated or bound to proteins) | −10.6d | [158] | |||||

| FepB | fepB/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | E. coli | Ferric-enterobactin complexes | High iron (20 μM FeSO4) vs iron-chelated (low iron) | −8.3e | [159] |

| VcFhuD | VC0395_A2582/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | Vibrio cholerae | Hydroxamate and catecholate type xenosiderophores | LB (high iron) vs LB + iron chelator (iron-depleted) | −12e | [160] |

| HbpA | hbpA/- | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | Haemophilus influenzae | Reduced and oxidized glutathione, heme, hemin | 10 μg/ml heme vs heme-deficient medium | 6.2d | [161] |

| hHbp | HD1816/Ta | ZnuA/PF01297 | Haemophilus ducreyi | Heme | 100 µg/ml heme vs 15 µg/ml heme | −3.9h | [162] |

| CpHmuT | hmuT/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis | Heme | Non-chelated (high iron) vs iron-chelated (low iron) | −1.9j | [163] |

| CgHmuT | hmuT/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Heme | 36 μM FeSO4vs 1 μM FeSO4 | −8.8b | [164] |

| YpHmuT | hmuT/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | Yersinia pestis | Heme | 40 μM FeCl3vs iron-chelated (low iron) | −6.8b | [165] |

| HtxB | htxB/Ta | No data | Pseudomonas stutzeri | Hypophosphite, phosphite | 2 mM Pi vs 0.1 mM Pi | −10.6e | [166] |

| 2 mM Pi vs 0.1 mM phosphite | −13.2e | ||||||

| 2 mM Pi vs 0.1 mM hypophosphite | −17.5e | ||||||

| IdiA | Tery_3377/- | No data | Trichodesmium erythraeum | Fe(III) | Non-chelated (high iron) vs iron-chelated (low iron) | −50d | [167] |

| MntC | mntC/Ta | ZnuA/PF01297 | N. gonorrhoeae | Mn(II), Zn(II) | Mn(II) excess vs Mn(II)-chelated | Increased MntC levels in the presence of ion chelatorc | [90] |

| ModA | modA/Ta | No data | E. coli | Molybdate, chromate, perrhenate | 100 µM Mo(II) vs no Mo(II) | −36.7e | [168] |

| NikA | nikA/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | E. coli | Ni(II) | 250 µM Ni(II) vs no Ni(II) | −5.33e | [169] |

| 1 µM Ni(II) vs no Ni(II) | −4.5e | [170] | |||||

| 10 mM nitrate vs no nitrateq | −3.6e | ||||||

| NikZ | cj1584c/Ta | SBP_bac_5/(PF00496 | C. jejuni | Ni(II) | 500 µM Ni(II) vs no Ni(II) | NikZ was not detected in the presence of nickelk | [171] |

| PhnD | phnD/Ta | No data | E. coli | Phosphonate, 2-aminoethylphosphonate | 2 mM Pi vs 0.2 mM Pi | −3466e | [87] |

| PstS | pstS/Ta | PBP_like_2/PF12849 | P. aeruginosa | Pi | 1 mM Pi vs 0.2 mM Pi | −223b | [51] |

| PstS1 | Rv0934/Ta | PBP_like_2/PF12849 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Pi | 3.6 mM Pi vs Pi starvation | -2.2d | [172] |

| PstS3 | Rv0928/Ta | PBP_like_2/PF12849 | M. tuberculosis | Pi | 3.6 mM Pi vs Pi starvation | −6.5d | [172] |

| PtxB | ptxB/Ta | No data | P. stutzeri | Pi, hypophosphite, phosphite, methylphosphonate | 2 mM Pi vs 0.1 mM Pi | −15e | [166] |

| 2 mM Pi vs 0.1 mM phosphite | −20e | ||||||

| 2 mM Pi vs 0.1 mM hypophosphite | −17e | ||||||

| Sbp | XAC1017/Ta | No data | Xanthomonas citri | Sulfate | 2 mM sulfate vs 1 mM sulfate | −1.9k | [173] |

| VatD | VV2_1012/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | V. vulnificus | Ferric aerobactin, ferric vulnibactin | Non-chelated iron (high iron) vs iron-chelated (low iron) | −9.0h | [156] |

| ViuP | viuP/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | V. cholerae | Ferric vibriobactin | 40 µM FeSO4vs no iron | −6.1b | [174] |

| ZnuA | znuA/Ta | ZnuA/PF01297 | E. coli | Zn(II), Co(II), Cu(II), Cu(I), Cd(II) | 5 µM ZnSO4vs ZnSO4-depleted | −20e | [175] |

| 0.2 mM ZnSO4vs no ZnSO4 | No changeb | [176] | |||||

| Organic acids | |||||||

| AdpC | adpC (RPA4515)/SPa | TctC/PF03401 | Rhodopseudomonas palustris | Adipate, 2-oxoadipate, trans-trans-muconate, pimelate, suberate, azelate | 1 µM adipate vs no adipate | 5.8d | [103] |

| 10 mM adipate vs no adipate | −2.6d | ||||||

| 10 mM pimelate vs no pimelate | −2.8d | ||||||

| 10 mM suberate vs no suberate | −10.0d | ||||||

| 10 mM azelate vs no azelate | −10.0d | ||||||

| BctC | bp3867/Ta & SPa | TctC/PF03401 | Bordetella pertussis | Citrate | 10 mM citrate vs no citrate | 16.9e | [89] |

| CouP | RPA1789/Ta | Peripla_BP_6/PF13458 | R. palustris | p-coumarate, ferulate, caffeate, cinnamate | 3 mM p-coumarate vs 3 mM benzoate | 5.7b/4.3g | [177] |

| MatC | RPA3494/Ta | TctC/PF03401 | R. palustris | L- and D-malate, succinate, fumarate, L- and D-Met | 10 mM succinate vs 3 mM p-coumarate | No changeb | [177] |

| 10 mM succinate vs 3 mM benzoate | No changeb | ||||||

| SiaP | siaP/Ta | DctP/PF03480 | H. influenzae | Sialic acid, N-acetylneuraminic acid, N-glycolylneuraminic acid | 0.1 mM sialic acid vs no sialic acid | 3.3d,l | [178] |

| TarP | RPA1782/Ta | DctP/PF03480 | R. palustris | p-coumarate, ferulate, caffeate, cinnamate | 3 mM p-coumarate vs 10 mM succinate | 2.3b/3.2g | [177] |

| TauA | tauA/Ta | OpuAC/PF04069 | E. coli | Taurine, N-(2-acetamido)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonate | 250 µM taurine vs 250 µM sulfate | 143e | [88] |

| Polyamines and quaternary ammonium compounds | |||||||

| BetS | betS | BCCT/PF02028 | Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) meliloti | Glycine betaine, proline betaine | 1 mM glycine betaine vs no glycine betaine | No changee | [179] |

| 0.3 M NaCl vs no NaClq | No changee | ||||||

| ChoX | choX/Ta | OpuAC/PF04069 | S. meliloti | Choline, acetylcholine | 7 mM choline vs no choline | Increased ChoX levels in the presence of cholinec | [180] |

| NspS | VC0704/SPa | SBP_bac_8/Pf13416 | V. cholerae | Spermidine, norspermidine, spermine | Increased vs low c-di-GMP levelsq | 2.9b | [181] |

| OpuAC | opuAC/Ta | OpuAC/PF04069 | Bacillus subtilis | Glycine betaine, proline betaine, arsenobetaine, dimethylglycine | 1 mM glycine betaine vs no glycine betaine | −2.2b | [124] |

| 1.2 M NaCl vs no NaClq | 2.1b | ||||||

| 0.5 M NaCl vs no NaClq | Increased transcription under osmotic stressm | [182] | |||||

| PotD | potD/Ta | SBP_bac_8/Pf13416 | E. coli | Spermidine, putrescine | 0.1 mg/ml putrescine vs no putrescine | −2m | [183] |

| ProX | proX/Ta | OpuAC/PF04069 | E. coli | Glycine betaine, proline betaine | 0.7 M sorbitol vs no sorbitolq | 10.0h | [184] |

| 0.4 M NaCl vs no NaClq | 9.3h | ||||||

| 1 mM glycine betaine vs no glycine betaine | −5.7e | [123] | |||||

| SpuD | spuD/Ta | SBP_bac_8/PF13416 | P. aeruginosa | Putrescine | 20 mM putrescine vs no putrescine | 8.4e | [185] |

| SpuE | spuE/Ta | SBP_bac_8/PF13416 | P. aeruginosa | Spermidine | 20 mM spermidine vs no spermidine | 14e | [185] |

| Mono-, oligo- and polysaccharides | |||||||

| AguE | TM_0432/Ta | SBP_bac_1/PF01547 | Thermotoga maritima | α-1,4-digalacturonate | 10 mM pectin vs 10 mM D-ribose | 24b | [186] |

| AlgQ2 | algQ2/Ta | SBP_bac_1/PF01547 | Sphingomonas sp. A1 | Alginate oligosaccharides | 0.5% (w/v) alginate vs 0.5% (w/v) glucose | AlgQ2 was only detected in cells growing in alginatec | [187] |

| AraF | araF/Ta | Peripla_BP_1/PF00532 | E. coli | L-Arabinose, D-arabinose, D-fucose | 0.2% (w/v) arabinose vs no arabinose | 27.8b | [94] |

| BglE | TM_0031/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | T. maritima | Cellobiose and laminaribiose | 10 mM cellobiose vs 10 mM D-ribose | 5b | [186] |

| CBP | VC_0620/Ta & SPa | SBP_bac_5/Pf00496 | V. cholerae | Chitin oligosacharides ((GlcNAc)x) | 0.6 mM GlcNAc vs no GlcNAc | No changeb,d | [102] |

| 0.6 mM (GlcNAc)2vs no (GlcNAc)2 | 67.9b/129d | ||||||

| 0.6 mM (GlcNAc)3vs no (GlcNAc)3 | 48.8b | ||||||

| 0.6 mM (GlcNAc)4vs no (GlcNAc)4 | 108.2b | ||||||

| 0.6 mM (GlcNAc)5vs no (GlcNAc)5 | 51.0b | ||||||

| 0.6 mM (GlcNAc)6vs no (GlcNAc)6 | 54.1b | ||||||

| 0.6 mM GlcN2vs no GlcN2 | No changeb,d | ||||||

| ChvE | chvE/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | A. tumefaciens | Galactose, glucuronic acid, galacturonic acid, arabinose and glucose | L-arabinose (3g or 5c mM) vs no L-arabinose | 8e/increased ChvE levelsc | [188], [189] |

| D-fucose (3g or 5c mM) vs no D-fucose | 6e/increased ChvE levelsc | ||||||

| D-galactose (3g or 5c mM) vs no D-galactose | 5e/increased ChvE levelsc | ||||||

| D-glucose (3g or 5c mM) vs no D-glucose | No changese/increased ChvE levelsc | ||||||

| 5 mM glucoronic acid vs no glucuronic acid | No changese | ||||||

| GltB | PA3190/Ta & SPa | SBP_bac_1/PF01547 | P. aeruginosa | Glucose | 10 mM glucose vs no glucose | 64.5e | [71] |

| MalE | malE/Ta | SBP_bac_1/PF01547 | E. coli | Maltose, maltotriose, maltetrose, maltotetraose | 1 g/l glucose vs 0.1 g/l glucoseq | −67.4b | [109] |

| 58 mM maltose vs no maltose | ~12.0/24.0e,n | [190] | |||||

| 0.2% (w/v) arabinose vs no arabinose | −12.1b | [94] | |||||

| MalE | lmo2125/Ta | SBP_bac_8/PF13416 | Listeria monocytogenes | Maltose | 25 mM maltose vs no maltose | 25d | [191] |

| 12.5 mM maltotriose vs no maltotriose | 57d | ||||||

| MalE1 | TM_1204/Ta | SBP_bac_8/PF13416 | T. maritima | Maltose, maltotriose, β-(1-4)-mannotetraose | 5 g/l trehalose vs 5 g/l glucoseq | Increased expression in trehalosef | [192] |

| 5 g/l lactose vs 5 g/l glucoseq | Increased expression in lactosef | ||||||

| MalE2 | TM_1839/Ta | SBP_bac_8/PF13416 | T. maritima | Maltose, maltotriose, trehalose | 5 g/l trehalose vs 5 g/l glucose | Increased expression in trehalosef,h | [192] |

| 5 g/l maltose vs 5 g/l glucose | Increased expression in maltoseh | ||||||

| 5 g/l maltose vs 5 g/l glucose | 3.3b/26.1d | [193] | |||||

| MglB (or GBP) | mglB/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | E. coli | D-Galactose, D-glucose | 0.01-10 mM galactose vs no galactose | Strong induction of mglB transcriptiono | [92] |

| 4 g/l glucose vs <10 mg/l glucose | −3.5g | [108] | |||||

| 1 g/l glucose vs 0.1 g/l glucose | −28.0b | [109] | |||||

| MglB (or GBP) | mglB/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | Salmonella typhimurium | D-Galactose, D-glucose | 2 g/l glucose vs no glucose | −5.8e | [194] |

| MnBP3 | TM_1223/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | T. maritima | Mannose, mannobiose, cellobiose, laminaribiose, xylobiose, mannopentaose, cellopentaose, xylopentaose, laminaripentaose, mannohexaose | 0.25% (w/v) mannose vs 0.25% (w/v) arabinose | Up-regulatedb | [195] |

| MnBP6 | TM_1226/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | T. maritima | Mannose, Mannobiose, cellobiose, laminaribiose, xylobiose, mannopentaose, cellopentaose, xylopentaose, laminaripentaose, mannohexaose | 0.25% (w/v) mannose vs 0.25% (w/v) arabinose | Up-regulatedb | [195] |

| RBP | TM_0958/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | T. maritima | D-ribose | 10 mM D-ribose vs 10 mM L-arabinose | 22b | [186] |

| 10 mM D-ribose vs 10 mM L-trehalose | 42b | ||||||

| RbsB | rbsB/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | E. coli | D-ribose | 10 mM D-ribose vs no D-ribose | 43.8p | [93] |

| 4 g/l glucose vs <10 mg/l glucose | −4.4g | [108] | |||||

| ThuE | thuE/Ta | SBP_bac_1/PF01547 | S. meliloti | Trehalose, maltose | 0.4% (w/v) trehalose vs 0.4% (w/v) sucrose | 6.5e | [196] |

| 0.4% (w/v) maltose vs 0.4% (w/v) sucrose | No changee | ||||||

| XloE | TM_0071/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | T. maritima | Xylobiose, xylotriose | 10 mM D-xylose vs 10 mM D-ribose | 26b | [186] |

| YtfQ | ytfQ/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | E. coli | Galactofuranose, arabinose, galactose, talose, allose, ribose | 1 g/l glucose excess vs 0.1 g/l glucoseq | −11.4b | [109] |

| 4 g/l glucose vs <10 mg/l glucoseq | −7.8g | [108] | |||||

| Cofactors and terminal electron acceptors | |||||||

| BtuF | synpcc7002_a0635/Ta | Peripla_BP_2/PF01497 | Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 | Cyano-cobalamin (vitamin B12) | 4 µg/L cobalamin vs no cobalamin | -18.1j | [197] |

| TorT | torT/SPa | Peripla_BP_1/PF00532 | E. coli | Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) | Anaerobic vs aerobic growthq | 2.5e | [97] |

| Opines and quorum sensing molecules | |||||||

| AccA | accA/Ta | SBP_bac_5/PF00496 | A. fabrum | Agrocinopine D, agrocinopine-3'-O-benzoate, agrocin 84, agrocinopine A, D-glucose-2-phosphate, L-arabinose-2-isopropylphosphate, L-arabinose-2-phosphate | 20 µM agrocinopines vs no agrocinopines (under phosphate limiting conditions; 0.1 mM Pi) | 4.5e | [198] |

| 20 µM agrocinopines vs no agrocinopines (under phosphate rich conditions; 25 mM Pi) | No changee | ||||||

| LuxP | luxP/SPa | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | Vibrio harveyi | AI-2 | 1 µM AI-2 vs no AI-2 | No changee | [199] |

| LsrB | lsrB/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | E. coli | AI-2 | 100 µM AI-2 vs no AI-2 | 10.5b | [200] |

| LsrB | SM_b21016/Ta | Peripla_BP_4/PF13407 | S. meliloti | AI-2 | 80 µM AI-2 vs no AI-2 | 13.0d | [201] |

| NocT | atu6027/Ta | SBP_bac_3/PF00497 | A. tumefaciens | Nopaline, pyronopaline, octopine | Nopaline/pyronopaline mix (1 mM) vs no nopaline/pyronopaline | 54.5b/68.1d | [202] |

Genes associated with: T: transporter genes; SP: Signaling protein genes.

Microarray data.

Western blot.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Reporter gene expression.

Northern hybridizations.

Mass spectrometry proteome analysis.

Protein expression profiling (2D protein gels followed by mass spectrometry/peptide mass fingerprinting).

Exponentially modified protein abundance index [emPAI].

RNA-sequencing.

SDS-PAGE gel analysis.

Induction was only observed in a nanAsiaB double mutant that can neither catabolize nor activate sialic acid.

Primer extension analyses.

Lowest and highest fold-change values measured at the different pH values ranging from 4.75 to 5.75.

In vitro transcription assays.

Genomic SELEX screenings.

Regulation mediated by non-cognate ligands or by environmental cues associated with SBP function.

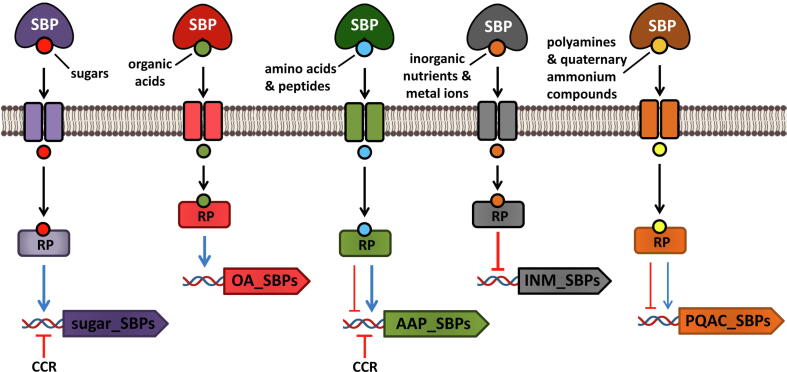

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the different membrane proteins that bind solute binding proteins (SBPs) and their corresponding primary functions. LBD: Ligand binding domain, GGDEF: diguanylate cyclase; EAL: phosphodiesterase. In some cases binding of ligand-free SBP to receptor protein has been observed.

For the former three families, the SBP binds to the LBD of the corresponding receptor protein. So far, there is only one characterized example of a SBP-stimulated Ser/Thr kinase, namely the tripartite GlnH/GlnX/PknG system [22]. GlnX is a transmembrane protein that has two 4HB LBDs at its periplasmic face. The binding of the GlnH SBP to GlnX generates a molecular stimulus that is transduced across the membrane to modulate the activity of the bound Ser/Thr kinase PknG [22]. The available data indicate that PknG phosphorylates primarily GarA, a regulatory protein that redirects metabolic fluxes towards the synthesis or degradation of glutamate by interacting with different enzymes involved in TCA cycle and glutamate metabolism [22], [23], [24]. More recent studies, however, have identified a significant number of physiological alternative PknG phosphorylation targets that connect PknG with the regulation of protein translation and folding [25].

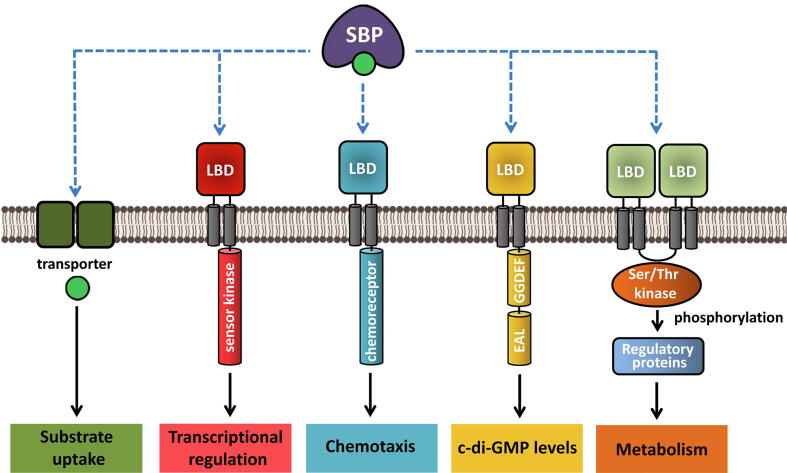

In general, bacterial receptors employ a large variety of different LBDs, but, from the structural point of view, most LBDs can be classified into four major classes: mono-modular (i.e. TarH, PilJ) and bi-modular (i.e. HBM, TorS sensor) 4HB domains as well as mono- (i.e., sCache, GAF or PAS) and bi-modular (i.e. dCache, LuxQ-periplasm) α/β folds [13], [14]. Inspection of the LBDs of SBP-stimulated sensor proteins reveals that they include members of all four categories (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Structural information available on the interaction of SBPs with the ligand binding domains (LBDs) of signal transduction receptors. A) Proposed model for the interaction of the LBD of the Tar chemoreceptor with the maltose binding protein (MBP). Model reconstructed according to [26]. B) Sensor kinase LytS with XylFII [27] (Protein Data Bank [PDB] 5XSJ). C) Sensor kinase TorS with TorT [28] (PDB 3O1H). D) Sensor kinase LuxQ with LuxP [29] (PDB 2HJ9). E,F) Sensor kinase HptS in complex with apo and ligand-loaded HptA [30] (PDB 6LKG, 6LKH). For clarity, only a single monomer of the sensor kinase LBD is shown. G) Homology model of the AioS sensor kinase generated by Phyre2 [31]. This domain has a sCache domain-like fold. H) Structure of an HBM domain [32] (PDB 2YFA), the domain type predicted for the CtpL chemoreceptor. Structures are coloured according to secondary structure and protein type: cyan: LBD α-helix; pink: LBD β-strand; red: SBP α-helix; yellow: SBP β-strand. Ligands bound to SBPs are shown as blue spheres.

As shown in Fig. 2, the Tar chemoreceptor and the LytS sensor kinase possess mono-modular 4HB LBDs, whereas the chemoreceptor CtpL and the TorS sensor kinase possess bi-modular 4HB LBDs. The LuxQ and HptS sensor kinases employ dCache-like bimodular α/β-folds (Fig. 2D-F), whereas the TlpB chemoreceptor of Helicobacter pylori has the sCache_2 LBD monomodular α/β-fold (Table 1). In addition, homology modelling revealed that AioS has also a sCache-like LBD (Fig. 2G). SBP-stimulated receptors are thus found in phylogenetically different species, and a variety of different LBD types have evolved to recognize SBPs.

The diversity in the LBDs of receptor proteins is also reflected in the diversity of their SBP counterparts (Table 1). In total, SBPs of 13 different sequence-based protein families interact with receptors, the most abundant being members of the Peripla_BP_4 (PF13407), SBP_bac_5 (PF00496) and SBP_bac_8 (PF13416) families. Although SBPs share the same bi-modular lobe structure, they differ largely in size. The SBPs that bind to bacterial receptors span literally the entire size range that ranges from 31 kDa of AibB to the 63 kDa of the chitooligosaccharide-binding protein (CBP) (Table 1). There is no obvious correlation between the SBP family and the type of receptor protein or LBD. For example, the 6 SBPs that stimulate the 4 E. coli chemoreceptors, all possessing a TarH LBD, belong to three different families, namely SBP_bac_8, SBP_bac_5 and Peripla_BP_4 (Table 1).

The limited number of SBP-LBD co-crystal structures suggests that another layer of diversity resides in the mode by which SBPs interact with LBDs of similar structure. Based on extensive site-directed mutagenesis studies [33], [34], [35], the “mushroom” shaped model for the interaction of the maltose binding protein (MBP) with the Tar-LBD was established (Fig. 2A) [26]. Alternatively, the XylFII SBP binds sideways to the 4HB structure of LytS-LBD (Fig. 2B). Analogously, the LuxP SBP binds sideways to the LuxQ LBD of the “LuxQ-periplasm” family that belongs to the dCache domain superfamily (Fig. 2D) [14]. In contrast, the binding mode of HptA to the dCache-like LBD of HptS is different since the SBP bridges two HptS-LBD monomers (Fig. 2E-F).

3. Chemoreceptors

By far the most thoroughly investigated chemotaxis system is that of Escherichia coli, and most fundamental aspects of chemotaxis have been discovered using this species [36]. It has four transmembrane chemoreceptors with a TarH type LBD in the periplasmic space as well as an aerotaxis receptor. There is direct evidence that three of these chemoreceptors, Tar, Trg and Tap, are activated by the binding of SBPs loaded with different sugars or dipeptides, mediating chemoattraction to these compounds (Table 1) [26], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. More recent data also indicate that Trg is activated by the spermidine SBP PotD [43]. Interestingly, the Tar chemoreceptor is stimulated by the direct binding of aspartate as well as of the maltose binding protein, and both stimuli were found to be additive and independent [44]. In addition, there is also indirect evidence that the fourth E. coli chemoreceptor, Tsr, is also activated by direct binding of serine and interaction with an SBP [45], [46]. E. coli showed strong attraction to the autoinducer-2 (AI-2) quorum sensing signal. As this response depends on Tsr as well as on the AI-2 binding SBP LsrB, it is very likely that these two proteins interact in the periplasm [45], [46]. The notion that all four chemoreceptors of the model organism most-studied for chemotaxis are activated by SBP binding gives further support to the notion that this type of sensing is widespread.

Apart from the E. coli, there are relatively few characterized chemoreceptor – SBP interactions. A well-characterized example is Pseudomonas aeruginosa chemotaxis to inorganic phosphate (Pi) [47], [48], which is a central signal molecule that controls bacterial virulence [49]. Pi chemotaxis is due to the action of two chemoreceptors, CtpH and CtpL, that respond to high and low Pi concentrations, respectively [47], [48]. The concerted action of both receptors thus provides an expansion of the response range. The two receptors employ different sensing mechanisms: whereas CtpH recognizes Pi directly via its TarH type LBD, CtpL contains an HBM type LBD and is activated by the binding of the Pi-loaded PstS SBP [48]. PstS is part of the Pst uptake system for phosphate [50] and binds Pi ultra-tightly (KD= 9 nM) [48]. The transcript levels of pstS are very tightly regulated by Pi; a reduction from 1 to 0.2 mM Pi in the medium increased pstS transcript levels 223-fold (Table 2) [51].

The genes encoding SBPs that interact with E. coli and P. aeruginosa chemoreceptors are associated with transporter but not with chemoreceptor genes (Table 1). Interestingly, in the archaeum Halobacterium salinarum the SBP genes basB and cosB were identified just upstream the genes encoding the BasT and CosT chemoreceptors, respectively [52], [53]. BasB and CosB are homologous to SBPs that bind short chain aliphatic amino acids and quaternary amines, respectively. Notably, deletion of either basT and cosT gene abolished chemotaxis to these compounds, suggesting that these proteins cooperate to mediate these responses. In addition, the chemotaxis phenotype of basB and basT mutants was similar [52], [53].

The data that are currently available indicate that direct binding of a signal molecule to a chemoreceptor LBD causes chemoattraction [54], whereas repellent chemotaxis appears to be caused by alternative mechanisms [55]. The evidence that repellent taxis can occur through activation of a chemoreceptor by an SBP is thus far indirect [43], [56]. H. pylori is repelled by AI-2, a response that depends on the TlpB chemoreceptor [57]. However, deletion of the genes encoding the AibA and AibB SBPs prevented this chemorepellent response. Both SBPs were shown to bind AI-2 in vitro and the authors suggested that both SBPs interact with the TlpB chemoreceptor [56]. In another study, it was demonstrated that E. coli shows strong repellent responses to spermidine. In contrast to the wild type strain, the potD mutant showed chemoattraction to spermidine, indicating that: (1) the SBP PotD is responsible for the observed repellent chemotaxis response; and (2) that there is another mechanism responsible for chemoattraction to spermidine [43].

4. Sensor kinases, diguanylate cyclases/phosphodiesterases and Ser/Thr kinases

The functions and regulons of sensor kinases, diguanylate cyclases/phosphodiesterases and Ser/Thr kinases that are stimulated by SBP binding are listed in Table 3. The SBP-stimulated systems carry out a number of different functions, including transport, respiration, compound catabolism or virulence, suggesting that there is no apparent restriction to the function of SBP-stimulated systems. These data also support the idea that these regulons are associated with specific and well-defined functions. As indicated above, the only characterized SBP-stimulated Ser/Thr kinase is PknG, which phosphorylates several target proteins that are involved in very different cellular processes [25]. Several studies of SBP-activated sensor kinases have provided insight into the sensing and transmembrane signaling mechanism that is summarized below.

Table 3.

The functions of SBP-stimulated signal transduction receptors.

| Receptor | SBP | Function of system | Regulon/Comment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemoreceptors | ||||

| Tar | MBP | Chemoattraction to maltose | [26 | |

| Tap | DppA | Chemoattraction to dipeptides | [41] | |

| Trg | GBP RBP PotD |

Chemoattraction to galactose Chemoattraction to ribose Chemorepellence from spermidine |

[38], [42], [43] | |

| Tsr | LsrB/Ta | Chemoattraction to AI-2 | [45], [46] | |

| TlpB | AibA AibB |

Chemorepellence from AI-2 | [56] | |

| CtpL | PstS | Chemoattraction to low Pi concentrations | [48] | |

| BasT | BasB | Chemoattraction to amino acids | [53] | |

| CosT | CosB | Chemoattraction to quaternary amines | [53] | |

| Sensor kinases | ||||

| LuxQ | LuxP | Quorum sensing | Five small regulatory RNAs (Qrr1-5) that target the master quorum sensing regulator LuxR | [203] |

| LytS | XylFII | D-xylose transport | xylFGH operon encoding an D-xylose ABC transporter | [134] |

| TorS | TorT | Respiration on TMAO | torCAD operon encoding the trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) reductase system | [204] |

| HptS | HptA | Glucose-6-phosphate transport | uhpT encoding the hexose phosphate transporter | [137] |

| VirA | ChvE | Virulence | vir genes and the repABC operon whose expression leads to the insertion of A. tumefaciens T-DNA from Ti plasmid into host cells, causing tumor formation | [205] |

| AioS | AioX | Control of As(III) oxidation | aioBA genes encoding an As(III) oxidase | [206] |

| BctE | BctC | Citrate transport | bctCBA operon encoding a tripartite tricarboxylate transporter | [89] |

| ChiS | CBP | Degradation of chitin | 50 genes, most of which encode proteins involved in chitin catabolism | [59] |

| GtrS | GltB | Glucose transport | gltBFGK-oprB operon encoding glucose transporter | [71] |

| Diguanylate cyclase/c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases (GGDEF/EAL) | ||||

| MbaA | NspS | Control of biofilm formation | Changes in c-di-GMP levels that alter expression of vps genes (among others), encoding proteins for biofilm polysaccharide synthesis | [207] |

| ScrC | ScrB | Motility and capsular polysaccharide production | Changes in c-di-GMP levels that alter expression of laf (lateral flagellum) and cps (capsular polysaccharide) genes, resulting in altered swarming motility and colony morphology | [208] |

| Serine/threonine kinase | ||||

| GlnX/PknGa | GlnH | Control of glutamate levels by regulating the activities of enzymes involved in TCA cycle and glutamate metabolism; evidence for additional PknG phosphorylation targets | PknG phosphorylates the regulatory protein GarA. Recent mass spectrometry approaches identified novel candidate PknG substrates that have roles in metabolism, cell wall synthesis and protein processing, translation and folding | [22], [24], [25], [209] |

The transmembrane protein GlnX interacts with the periplasmic SBP GlnH and with the Ser/Thr kinase PknG in the cytosol.

4.1. The sensing mechanism

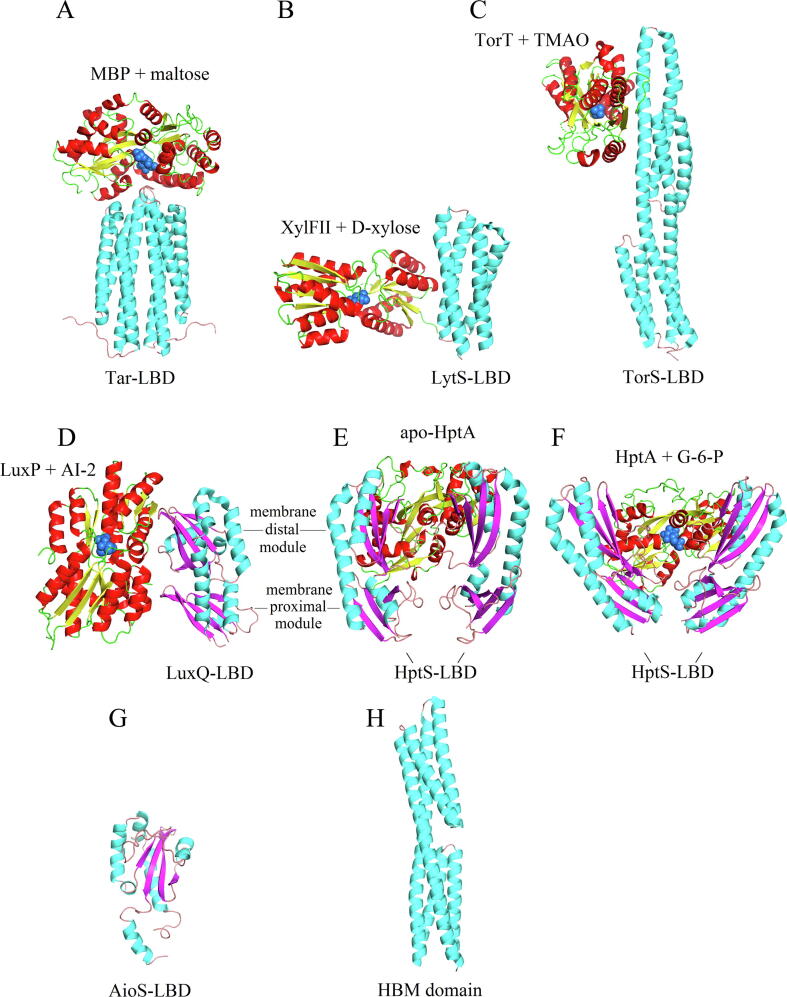

SBP-stimulated systems are composed of three molecules that mutually interact. The thermodynamics of this interaction have been established for the TorS-LBD/TorT/TMAO system [28] that is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The mechanism of TorT and TMAO recognition by the ligand-binding domain of TorS. Because sensor kinases form stable dimers in the membrane, experiments were conducted using a dimeric TorS-LBD in which both monomers are covalently linked by a 25 amino acid flexible linker. The thermodynamic parameters derived from analytical ultracentrifugation and isothermal titration calorimetry experiments are indicated. Data were taken from [28].

Two apoTorT molecules were found to bind to the TorS-LBD dimer with high affinity (Kd=1.79 µM). ApoTorT bound its signal molecule TMAO (trimethylamine N-oxide) with a relatively modest affinity of 74 µM. However, TMAO recognition by the TorS-LBD/TorT complex occurred with negative cooperativity, with the two respective Kd values being 1.36 and 121 µM. This result indicates that TMAO binds preferentially to the SBP when it is associated to the sensor kinase as compared to the free form. Analytical ultracentrifugation studies also showed that TMAO binding to apoTorT increases its affinity for TorS-LBD, a finding that was also reflected in decreased atomic mobility at the TorS-LBD/TorT interface. In a similar way, the CBP SBP interacts with the non-canonical DNA binding sensor kinase ChiS to repress its activity, and the binding of chitin oligosaccharides by the CBP/ChiS complex activates ChiS without triggering the dissociation of the complex [58]. Of note is that these findings do not agree with a previous publication that suggested a ligand-induced dissociation of CBP from ChiS [59]. However, the sensing mechanisms established for these systems may not be generally applicable to all SBPs. For example, the working model of the MbaA-NspS system proposes that the binding of spermidine to the SBP NspS induces its dissociation from the MbaA sensor domain [60].

4.2. The mechanism of signal transduction: multiple events leading to a lateral displacement of transmembrane helices

The currently available data suggest that there may be multiple mechanisms by which signal-loaded SBPs control sensor autokinase activity. Such mechanisms involve signal-induced changes in the symmetry of the LBD dimer, structural rearrangements and/or induction of the formation of larger hetero-complexes [61]. However, it appears that all of these alterations ultimately result in a lateral displacement of the transmembrane regions of the sensor kinase that may be the molecular stimulus that alters autokinase activity.

In the absence of the AI-2 signal, LuxP and LuxQ-LBD form hetero-dimers [29]. Upon signal binding, two LuxP/LuxQ-LBD pairs interact to form an asymmetric hetero-tetramer. In this asymmetric tetramer, both LuxQ-LuxP pairs are related by a rotation of 140 degrees, which represents a significant asymmetry. As a consequence of this asymmetry, the transmembrane helices are displaced laterally, which may be the molecular stimulus triggering changes in autokinase activity [29]. The mechanism of the LuxQ-LuxP system thus involves the signal-induced introduction of protein asymmetry and the formation of the hetero-tetramer complex. Analogously, the XylFII SBP forms hetero-dimers with the LBD of the LytS sensor kinase [27]. In the presence of the D-xylose signal, two dimers interact to form the hetero-tetramer. In the working model of the XylFII-LytS system, the authors propose that the formation of this signal-induced complex formation also causes a lateral displacement of the sensor kinase transmembrane regions [27].

In the crystallographic study of the TorS-TorT system [28], the authors used a covalently linked TorS-LBD dimer that makes it impossible to observe individual SBP-LBD complexes as observed in the two systems just discussed. The authors reported the structures of the apoTorT/TorS-LBD complex as well as of complex structures that contained the TMAO signal or isopropanol (present in the crystallization buffer) in the TorT ligand-binding site [28]. The structures of the two complexes were almost identical, indicating that isopropanol binding had the same effect as TMAO binding. In these structures, the TorS-LBD dimer formed a complex with two TorT monomers. In the signal-free structure, this hetero-complex was asymmetric and characterized by two distinct TMAO-binding sites. The thermodynamic studies mentioned above show that TMAO binds both sites with negative cooperativity (Fig. 3). The symmetry of the hetero-complex is achieved when TMAO binds to both sites, and the authors suggest that asymmetry must be reinforced by TMAO binding to the first, high-affinity site. Therefore, signal binding in this system causes an asymmetry-to-symmetry transition that is the opposite of the symmetry-to asymmetry transition observed in the LuxQ-LuxP system [28].

A crystallographic study of the HptA/HptS-LBD complex has been reported recently [30]. The HptS-LBD belongs to the family of dCache domains that are composed of two α/β modules, generally referred to as membrane distal and membrane proximal module. In the apo form, a hetero-tetramer was observed in which apo HptA SBP interacted with the membrane distal modules of both HptS-LBD monomers (Fig. 2E). However, binding of the signal molecule glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) caused large structural rearrangements. The result of these rearrangements was that HptA linked the membrane-distal module of one HptS-LBD monomer with the membrane-proximal module of the other (Fig. 2F). These large structural rearrangements caused a tilting of HptS-LBD, leading to a lateral displacement of both transmembrane regions in a manner reminiscent of the other systems studied [30].

Cache domains are the most abundant extracytosolic bacterial sensor domains [13], [14], [62] and the majority of Cache domains are present in their dCache configuration. A large number of dCache domains have been studied, and, in almost all cases, ligands bind to the membrane-distal module [63], [64], [65], [66]. That circumstance raised the question as to the function of the membrane-proximal module. The X-ray study of HptS-LBD in a complex with HptA described above may provide an answer to this question. It was shown that signal-bound HptA links two HptS-LBDs by establishing contacts with the membrane-distal and membrane-proximal modules [30]. Other than the finding that lactate binds to the membrane-proximal module of the TlpC chemoreceptor of H. pylori [67], this is the first demonstration of a role for the membrane-proximal module of dCache domains in the signaling process. Future studies will show to what degree other dCache domains operate by the same mechanism.

The signal transduction mechanism for systems that sense signals directly is still subject to debate [61]. Ligand binding at LBDs has been shown to induce a number of different reorientations, such as helical rotation, piston shifts or helix scissoring movements. Frequently, these changes occur concomitantly, and several reorientations of the receptor LBD, like scissoring movements, are compatible with lateral displacements of the transmembrane regions [68], [69], [70]. Further research will be required to determine to what degree lateral displacements of transmembrane regions cause the activation, whether direct or indirect, of ligand-triggered signal-transduction receptors.

5. GltB: A SBP that interacts with a sensor kinase and chemoreceptors

Another layer of complexity of SBP-mediated regulation is added by the observation that the glucose-sensing SBP GltB interacts with the periplasmic domain of the GtrS sensor kinase as well as with the LBD of the PctA and McpN chemoreceptors [71]. The GtrS-LBD had been previously shown to bind two glucose derivatives, 2-ketogluconate and 6-phosphogluconate, and to regulate the expression of genes involved in glucose metabolism [72]. Xu et al. show that the binding of glucose-loaded GltB is essential for the GtrS-mediated control of genes involved in glucose transport [71]. Chemoreceptors PctA and McpN were previously found to bind amino acids and nitrate, respectively, and to mediate chemoattraction to these compounds [73], [74], [75]. Although the authors of this study demonstrate the binding of GltB to the LBDs of PctA and McpN, they did not explore whether this resulted in chemotaxis. GtrS, PctA and McpN each possesses a different type of LBD. The LBD of GtrS is not recognized by any domain profile, whereas PctA and McpN possess a dCache and PilJ type LBD, respectively [64], [75]. The PctA chemoreceptor is a prime example of the complexity of bacterial signal transduction. Apart from binding amino acids [64] and GltB [71], PctA also mediates chemotaxis to AI-2 [76] and histamine [63]. It has been shown that the PctA-LBD binds AI-2 directly with high affinity [76], whereas it has been proposed that PctA mediates histamine chemotaxis through binding an unidentified SBP [63].

6. Additional studies suggesting SBP-mediated stimulation of signal transduction receptors

There are a number of other studies that provide indirect evidence for activation of signaling receptors by SBP binding. One example is the mechanism for chemotaxis of Sphingomonas sp. strain A1 to the polysaccharide pectin. The SBP SPH1118 binds pectin, and a knockout mutation in the corresponding gene abrogates pectin chemotaxis [77], suggesting an indirect activation mechanism. However, the molecular mechanism by which a polysaccharide interacts with an SBP remains to be established. Furthermore, the Tlp1 chemoreceptor of Campylobacter jejuni mediates chemotaxis to aspartate [78]. However, the 3D structure of the LBD revealed that the binding pocket is too small to accommodate this ligand and the individual Tlp1-LBD failed to bind aspartate. The authors thus suggest that Tlp1 is activated by SBP binding [78]. Another example is that of the McpC chemoreceptor of Bacillus subtilis, which supports chemotaxis to 17 amino acids. However, binding studies revealed that only 11 of them bound directly to the purified McpC-LBD [79]. To investigate a potential involvement of SBPs, the authors conducted pull-down experiments with immobilized McpC-LBD. This study detected interactions of MpcC with the amino acid-sensing SBPs ArtP, MetQ and YckB. The authors thus conclude that McpC employs two different mechanisms based on direct and indirect sensing [79]. Furthermore, chemotaxis of P. aeruginosa towards histamine is based on the concerted action of three chemoreceptors: TlpQ, PctA and PctC [63]. Whereas TlpQ-LBD bound histamine with nanomolar affinity, no direct binding was detected for the PctA and PctC chemoreceptors, which are known to bind different amino acids directly [64]. These data suggest that the histamine signal mediated by PctA and PctC signaling depends on their interaction with one or more histamine-binding SBPs. The Tlp1, McpC, PctA and PctC chemoreceptors all possess dCache-type LBDs. This observation, in combination with the available structural and functional data (Fig. 2, Table 1), suggests that SBP-mediated receptor stimulation may be a property of many dCache domains.

In Bacillus subtilis, the SBP-encoding gene ydbE is located next to genes encoding the sensor kinase-response regulator pair YdbFG. YdbE shows homology to SBPs that sense C4-dicarboxylates, and the YdbFG TCS regulates the utilization of fumarate and succinate [80]. Inactivation of either ydbFG or ydbE abolished this regulatory activity, and it was suggested that YdbE plays a sensory role by stimulating the YdbFG TCS [80]. Furthermore, the genes encoding homologs of the AI-2 SBP LsrB are typically found next to the AI-2 transporter. Interestingly, in Treponema primitia and Treponema azotonutricium lsrB genes are located next to genes encoding sensor kinase/response regulator pairs, suggesting a participation in TCS signaling rather than transport [81].

7. Regulation of SBP levels

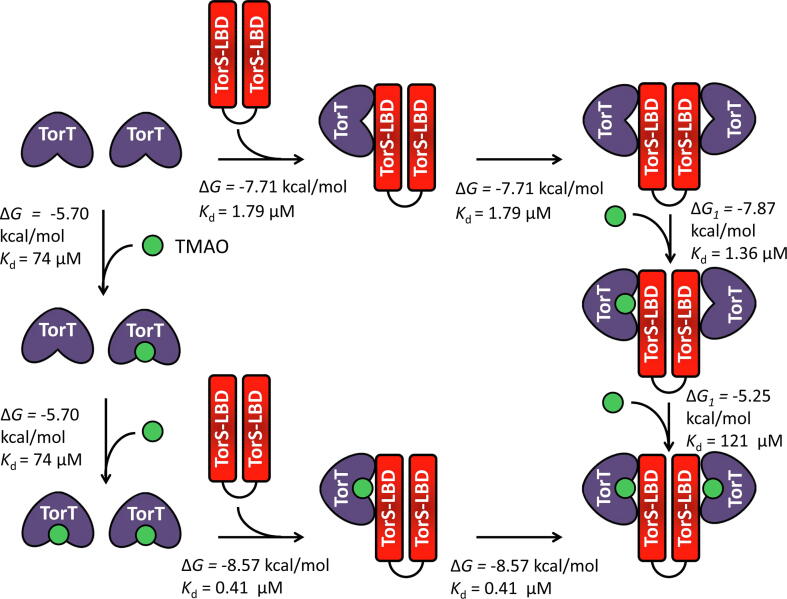

What are the advantages of SBP-mediated receptor stimulation as compared to systems that recognize signals directly? The overall responses of SBP-activated chemoreceptors have been shown to be highly sensitive to the SBP levels, permitting more-precise control of the sensitivity to specific ligands in response to their nutrient environment [21]. Although regulation of the expression of SBPs has been reviewed several times [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], the role of ligands on the expression of their cognate SBPs has not been analysed on a global scale. To assess the effect of different ligand families on SBPs levels, we have surveyed the results of studies on 88 SBPs from 27 different phylogenetically diverse bacterial species with different lifestyles, including plant, animal and human pathogens, beneficial plant-associated bacteria, as well as non-pathogenic marine and soil bacteria. These SBPs bind a wide range of compounds, including amino acids, peptides, organic acids, sugars, polyamines, quaternary amines, cofactors, opines, quorum-sensing molecules or inorganic nutrients. The effects of these ligands on the expression of their cognate SBPs are compiled in Table 2, and the resulting patterns are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Overview of the effect of different ligand families on the expression of solute binding proteins. Activation and repression are represented by triangular and flat arrowheads, respectively. The thickness of the lines represents a stronger upregulation or downregulation of the expression of target SBPs. SBP, solute-binding protein; RP, regulatory protein; CCR, carbon catabolite repression; OA, organic acids; INM, inorganic nutrients and metal ions; AAP, amino acids and peptides; PQAC, polyamines and quaternary ammonium compounds.

A major conclusion of this study is that 87 % of the ligands modulated the expression of their cognate SBPs (Table 2). The magnitude of regulation stretches from a 3466-fold downregulation of phnD expression in the presence of 2 mM as compared to 0.2 mM Pi [87] to a 143-fold upregulation in the expression of tauA in the presence of taurine[88]. Although the regulatory proteins that control the expression of several of the SBPs have been identified [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], the corresponding molecular mechanisms of the regulation are not the focus of this review.

7.1. Sugars and organic acids generally upregulate the expression of cognate SBPs

Sugars and organic acids are often preferred carbon sources for bacteria [99], [100], [101], and SBPs have been identified for mono-, oligo- and polysaccharides, tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates, sugar acids and aromatic acids (Table 2). The analysis of the expression of 27 sugar and organic acid SBPs from 11 different bacterial genera revealed a preferential upregulation in the presence of their cognate ligands (Table 2). Notable examples were the genes encoding CBP and TauA. whose expression was upregulated more than 100-fold in the presence of chitin oligosaccharides [102] and taurine [88], respectively. In some cases, different regulatory effects were observed at different ligand concentrations. For example, the transcript levels of adpC encoding an aliphatic dicarboxylate SBP were increased in the presence of micromolar concentrations of its dicarboxylate ligands but reduced in the presence of millimolar concentrations of these dicarboxylates [103]. As shown in Table 1, the SBPs BctC, ChvE and CBP stimulate the sensor kinases BctE [89], [104], VirA [105], [106], [107] and ChiS [59], [102], respectively, and their cognate ligands upregulate the expression of BctC, ChvE and CBP at the levels of both transcription and protein synthesis (Table 2).

In contrast to the general tendency that sugars enhance SBP expression, the presence of an excess of glucose reduced the expression of the sugar-binding, amino acid-binding and peptide-binding SBPs LAO/ArgT, MalE, MppA, MglB, OppA, RbsB and YtfQ either at the transcript or protein level (Table 2). This effect was mainly due to a global regulatory mechanism, termed carbon catabolite repression (CCR), that modulates up to 10% of all genes in a given bacterium [99], [100], [101]. The mechanism implies that in the presence of preferred carbon sources, such as glucose in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, the expression of genes involved in the catabolism and transport of non-preferred carbon sources is repressed. As shown in Table 2, CCR plays an important role in the regulation of multiple SBPs in E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium. A mechanistic reason for the CCR-mediated SBP repression may be related to the fact that E. coli preferentially uses the phosphoenolpyruvate–carbohydrate phosphotransferase system for glucose transport (independent of SBPs) when growing on millimolar concentrations of sugars and switches to high affinity transport systems dependent on SBPs under glucose-limiting conditions [82], [108], [109]. Thus, the synthesis of a number of ABC transporter SBPs is upregulated at low glucose concentrations (Table 2).

7.2. Downregulation of SBPs by inorganic ligands

Phosphorous and metal ions like iron, nickel, manganese and zinc are essential elements for many biological processes They also play important roles in bacterial signaling by modulating gene expression [110], [111], [112], [113], [114] and chemotactic processes [48], [115], [116]. The analysis of the expression of 28 phosphorous and metal ion SBPs from 16 different bacterial species revealed that these elements strongly repress the expression of their cognate SBPs (Table 2). Phosphorous and metal ions have a limited bioavailability due to their low abundance or insolubility. SBPs for these compounds are generally characterized by a very high affinity for their cognate ligands, permitting responses at very low concentrations. Representative examples are the binding of molybdate and Pi to their cognate SBPs ModA and PstS, respectively, that occurs with a much higher affinity (KD~10 nM) than in other compound families [48], [117]. In addition, the intracellular concentration of these elements needs to be finely balanced to avoid cellular toxicity. The repression of SBPs in response to elevated concentrations of metal ions and inorganic nutrients is a mechanism to maintain homeostatic intracellular levels [85], [86], [111], [113], [114]. As shown in Table 1, the SBP AioX binds arsenite and subsequently stimulates the TCS AioSR [118], [119]. In contrast to the effect of most inorganic compounds on SBP expression, arsenite induced aioX expression (Table 2), which may be due to the fact that AioSR induces the expression of the genes involved in arsenite oxidation (Table 3), a process that reduces the toxicity of the ligand.

7.3. Dissimilar effects of amino acids, polyamines and quaternary ammonium compounds on cognate SBPs expression

Contrary to what was observed for sugars and organic acid SBPs, the expression of SBPs specific for amino acids and peptides in E. coli was generally downregulated at both the gene expression and protein levels in the presence of their cognate ligands (Table 2). An interesting case is that of the four E. coli SBPs ArtI, ArtJ, HisJ and LAO/ArgT that bind arginine (Table 2) [120]. These SBPs are encoded in two different clusters, argT-hisJQMP and artPIQM-artJ, which also encode the ABC-type transporters HisQMP and ArtPQM, respectively [9]. The expression of the genes encoding ArtJ, ArtI and HisJ, but not ArgT, was downregulated in the presence of arginine in a regulatory process mediated by the transcriptional repressor ArgR [91], [121]. Whereas a strong downregulation was observed for artJ, only a weak repression was noted for hisJ and artI (Table 2). Current data suggest that this differential regulation is associated with the different physiological functions of ArtJ, ArtI, HisJ and LAO/ArgT. Thus, the arginine-specific ArtJ as well as the arginine-binding and ornithine-binding SBP ArtI were suggested to be mainly involved in the uptake of amino acids for biosynthetic processes [91], [120]. In contrast, the expression of argT is activated by the nitrogen regulatory protein NtrC in response to nitrogen limitation [122], and ArgT may be primary implicated in the transport of arginine under conditions of nitrogen starvation. HisJ binds histidine with a 10-fold higher affinity than arginine [91] and its weak repression by arginine (Table 2) may ensure efficient histidine uptake when arginine is abundant. The primary role of amino acid-binding and peptide-binding SBPs is the uptake of nutrients for growth, but the dipeptide-binding SBP DppA of E. coli is involved in both chemotaxis and transport (Table 1, Table 3) and its expression was downregulated at both the transcriptional and protein synthesis levels in the presence of casamino acids (Table 2).

The expression profiles of polyamine-binding and quaternary ammonium compound-binding SBPs in the presence of their cognate ligands was dissimilar, with these SBPs showing either upregulation, downregulation or unaltered expression (Table 2). Several of these SBPs bind the osmoprotectants glycine betaine and proline betaine, and their expression was induced in E. coli and B. subtilis under conditions of osmotic stress to permit a rapid adjustment of the intracellular osmotic strength (Table 2) [123], [124]. In accordance with the regulation of the expression of SBPs by environmental cues that are associated with the SBP function, the expression of torT encoding a SBP that binds the terminal electron acceptor TMAO was upregulated under anaerobic conditions [97]. In addition, second messengers were also found to modulate the expression of SBPs. As indicated above, the SBP NspS of V. cholerae forms a signaling system with the transmembrane GGDEF-EAL protein MbaA to control biofilm formation in response to polyamines [125]. Increased c-di-GMP intracellular levels were shown to upregulate the expression of nspS (Table 2).

8. Conclusions and research needs

The studies reviewed here strongly suggest that SBP-mediated activation of transmembrane receptors is a general and widespread phenomenon. Researchers working in the field are thus encouraged to design experimental strategies, using either genetic or protein biochemistry approaches, to identify further systems. The overall final objective of these research efforts, which will lead to a larger number of characterized systems, is to get a more comprehensive understanding of which signaling systems are stimulated by direct binding and which by SBP-based mechanisms. Accumulating information will also enable us to see more clearly the physiological constraints that have led to the evolution of receptor activation by direct and indirect binding. Central questions still to be answered are:

-

(1)

SBPs and receptor LBDs form superfamilies composed of many individual families. Do members of all or only some families participate in indirect receptor activation? Is it possible to identify sequence features specific for SBP-LBD interactions?

-

(2)

Whereas signal-loaded SBPs stimulate receptors, much less information is available on the role of the SBP apo forms. What are the affinities of apo- and holo-SBPs for their respective targets? What is the effect of apo-SBP binding on receptor activity?

-

(3)

Several receptors bind signals directly as well as in complexes with SBPs. How frequent are such systems and what is the flexibility in the response afforded by these dual input mechanisms for receptor activation?

-

(4)

What is the concentration of SBPs in the periplasmic space?

-

(5)

What factors determine whether the expression of an SBP is regulated by its cognate ligand?

-

(6)

What is the evolutionary history of the receptor proteins that are activated by both direct and indirect ligand binding?

The answers to these questions will not only increase our fundamental knowledge about signal transduction mechanisms but also may offer alternative strategies to fight pathogenic bacteria by interfering with their ability to sense, respond and adapt to their environment.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Miguel A. Matilla: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Álvaro Ortega: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Tino Krell: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer who dedicated much time and effort to improving the English of this article. This work was supported by FEDER funds and the Fondo Social Europeo through grants from the CSIC to MAM (PIE-202040I003), the Spanish Ministry for Science, Innovation and Universities to MAM (PID2019-103972GA-I00), the Junta de Andalucía (P18-FR-1621) and Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (BIO2016-76779-P) to TK. AO was funded by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the State Research Agency and the European Regional Development Fund (RTI2018–094393-BC21-MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE) and the Seneca Foundation CARM (20786/PI/18).

References

- 1.Scheepers G.H., Lycklama a Nijeholt J.A., Poolman B. An updated structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2016;590(23):4393–4401. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Gebali, S., Mistry, J., Bateman, A., Eddy, S. R., Luciani, A., Potter, et al., 2019. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47. D427-D432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Mitchell, A. L., Attwood, T. K., Babbitt, P. C., Blum, M., Bork, P., Bridge, A., et al.. 2019. InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D351-D360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Chu B.C., Vogel H.J. A structural and functional analysis of type III periplasmic and substrate binding proteins: their role in bacterial siderophore and heme transport. Biol Chem. 2011;392:39–52. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dwyer M.A., Hellinga H.W. Periplasmic binding proteins: a versatile superfamily for protein engineering. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14(4):495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L.e., Ghimire-Rijal S., Lucas S.L., Stanley C.B., Wright E., Agarwal P.K. Periplasmic Binding Protein Dimer Has a Second Allosteric Event Tied to Ligand Binding. Biochemistry. 2017;56(40):5328–5337. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song L., Zhang Y., Chen W., Gu T., Zhang S.-Y., Ji Q. Mechanistic insights into staphylopine-mediated metal acquisition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(15):3942–3947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718382115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galperin M.Y. What bacteria want. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20(12):4221–4229. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galperin M.Y. Diversity of structure and function of response regulator output domains. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13(2):150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wuichet, K. & Zhulin, I. B. (2010). Origins and diversification of a complex signal transduction system in prokaryotes. Sci Signal. 3, ra50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Bassler J., Schultz J.E., Lupas A.N. Adenylate cyclases: Receivers, transducers, and generators of signals. Cell Signal. 2018;46:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romling U., Galperin M.Y., Gomelsky M. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77(1):1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega A., Zhulin I.B., Krell T. Sensory Repertoire of Bacterial Chemoreceptors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2017;81:e00033–00017. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00033-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upadhyay A.A., Fleetwood A.D., Adebali O., Finn R.D., Zhulin I.B., Schlessinger A. Cache Domains That are Homologous to, but Different from PAS Domains Comprise the Largest Superfamily of Extracellular Sensors in Prokaryotes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(4):e1004862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhulin I.B., Nikolskaya A.N., Galperin M.Y. Common extracellular sensory domains in transmembrane receptors for diverse signal transduction pathways in bacteria and archaea. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(1):285–294. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.285-294.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis, V. I., Stevenson, E. C. & Porter, S. L. (2017). Two-component systems required for virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Kundu M. The role of two-component systems in the physiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. IUBMB Life. 2018;70(8):710–717. doi: 10.1002/iub.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martín-Mora D., Fernández M., Velando F., Ortega Á., Gavira J., Matilla M. Functional Annotation of Bacterial Signal Transduction Systems: Progress and Challenges. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3755. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKellar J.L., Minnell J.J., Gerth M.L. A high-throughput screen for ligand binding reveals the specificities of three amino acid chemoreceptors from Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Mol Microbiol. 2015;96:694–707. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jani S., Seely A.L., Peabody V.G., Jayaraman A., Manson M.D. Chemotaxis to self-generated AI-2 promotes biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2017;163:1778–1790. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumann S., Hansen C.H., Wingreen N.S., Sourjik V. Differences in signalling by directly and indirectly binding ligands in bacterial chemotaxis. EMBO J. 2010;29(20):3484–3495. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharyya N., Nkumama I.N., Newland-Smith Z., Lin L.-Y., Yin W., Cullen R.E. An Aspartate-Specific Solute-Binding Protein Regulates Protein Kinase G Activity To Control Glutamate Metabolism in Mycobacteria. 2018;9(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00931-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rieck B., Degiacomi G., Zimmermann M., Cascioferro A., Boldrin F., Lazar-Adler N.R. PknG senses amino acid availability to control metabolism and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(5):e1006399. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.100639910.1371/journal.ppat.1006399.g001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner T., André-Leroux G., Hindie V., Barilone N., Lisa M.-N., Hoos S. Structural insights into the functional versatility of an FHA domain protein in mycobacterial signaling. Sci Signal. 2019;12(580):eaav9504. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aav9504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baros S.S., Blackburn J.M., Soares N.C. Phosphoproteomic Approaches to Discover Novel Substrates of Mycobacterial Ser/Thr Protein Kinases. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2020;19(2):233–244. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R119.001668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y., Gardina P.J., Kuebler A.S., Kang H.S., Christopher J.A., Manson M.D. Model of maltose-binding protein/chemoreceptor complex supports intrasubunit signaling mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(3):939–944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J., Wang C., Yang G., Sun Z., Guo H., Shao K. Molecular mechanism of environmental d-xylose perception by a XylFII-LytS complex in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(31):8235–8240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620183114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore J., Hendrickson W. An asymmetry-to-symmetry switch in signal transmission by the histidine kinase receptor for TMAO. Structure. 2012;20(4):729–741. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neiditch M.B., Federle M.J., Pompeani A.J., Kelly R.C., Swem D.L., Jeffrey P.D. Ligand-induced asymmetry in histidine sensor kinase complex regulates quorum sensing. Cell. 2006;126(6):1095–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M., Guo Q., Zhu K., Fang B.o., Yang Y., Teng M. Interface switch mediates signal transmission in a two-component system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(48):30433–30440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912080117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]