Abstract

Introduction:

For patients with recurrent SCLC, topotecan remains the only approved second-line treatment, and the outcomes are poor. CheckMate 032 is a phase 1/2, multicenter, open-label study of nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab in SCLC or other advanced/metastatic solid tumors previously treated with one or more platinum-based chemotherapies. We report results of third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy treatment in SCLC.

Methods:

In this analysis, patients with limited-stage or extensive-stage SCLC and disease progression after two or more chemotherapy regimens received nivolumab monotherapy, 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks, until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary end point was objective response rate. Secondary end points included duration of response, progression-free survival, overall survival, and safety.

Results:

Between December 4, 2013, and November 30, 2016, 109 patients began receiving third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy. At a median follow-up of 28.3 months (from first dose to database lock), the objective response rate was 11.9% (95% confidence interval: 6.5–19.5) with a median duration of response of 17.9 months (range 3.0–42.1). At 6 months, 17.2% of patients were progression-free. The 12-month and 18-month overall survival rates were 28.3% and 20.0%, respectively. Grade 3 to 4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 11.9% of patients. Three patients (2.8%) discontinued because of treatment-related adverse events.

Conclusions:

Nivolumab monotherapy provided durable responses and was well tolerated as a third- or later-line treatment for recurrent SCLC. These results suggest that nivolumab monotherapy is an effective third- or later-line treatment for this patient population.

Keywords: SCLC, Third-line, Nivolumab, PD-1 inhibitor, Immunotherapy

Introduction

SCLC is an aggressive disease with no treatment options that produce durable responses.1–3 Current first-line treatments include platinum-based chemotherapy, which has good initial response rates (60%–80% for extensive-stage disease); however, nearly all patients relapse shortly after treatment and median survival time is only 1 to 2 years from the time of diagnosis.2,4 The only second-line therapy for SCLC is topotecan, which was initially approved as an intravenous formulation in 1998 and as an oral formulation in 2007. The median duration of response (DOR) with intravenous topotecan is 3.3 months,5 and treatment is characterized by high rates of grade 4 neutropenia (rates of 70% when administered intravenously and 32% when administered orally), grade 4 thrombocytopenia (29% when administered intravenously and 6% when administered orally), and grade 3 to 4 anemia (42% when administered intravenously and 25% when administered orally).6,7

Nivolumab is a fully human immunoglobulin G4 programmed death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitor antibody approved for the treatment of various cancer types, including previously treated NSCLC.8 Overall survival (OS) time was significantly prolonged with nivolumab versus with docetaxel in a pooled analysis of patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC from the phase 3 CheckMate 017 and 057 trials (pooled hazard ratio = 0.70, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.61–0.81).9 In a long-term analysis of patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC from the phase 1 CA209–003 study, the estimated 5-year OS rate was 16% with nivolumab monotherapy.10 On August 16, 2018, on the basis of the results presented in this article, nivolumab monotherapy received approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of patients with metastatic SCLC with progression after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy.

CheckMate 032 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01928394) is a multicenter, open-label, phase 1/2 trial evaluating nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab in patients with previously treated advanced or metastatic solid tumors. In an interim analysis of this study, a manageable safety profile and durable responses were observed with nivolumab monotherapy in a nonrandomized cohort of patients with SCLC and one or more prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimens.11 Here we report the efficacy and safety of third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy from pooled nonrandomized and randomized cohorts of patients with recurrent SCLC from CheckMate 032.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Treatment

Patients enrolled in CheckMate 032 were assigned to separate cohorts according to tumor type. Eligibility criteria for the SCLC cohort of CheckMate 032 included age 18 years or older, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1, histologically or cytologically confirmed limited-stage or extensive-stage SCLC, and previous treatment with one or more platinum-based chemotherapy regimens. The current analysis includes patients with disease progression after two or more prior chemotherapy regimens. Patients were eligible regardless of platinum sensitivity or tumor programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. Further eligibility criteria and trial details have been previously reported.11

Patients with SCLC were initially enrolled as part of a nonrandomized cohort (Supplementary Fig. 1), the design of which has been previously described.11 A subsequent randomized cohort was added to confirm clinical activity observed in the initial phase. The analysis in this article reports pooled results from the monotherapy arms of the nonrandomized and randomized cohorts. In both cohorts, nivolumab monotherapy, 3 mg/kg, was administered every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Nivolumab, 1 mg/kg, plus ipilimumab, 3 mg/kg, was also evaluated in both cohorts, the results of which will be reported separately. As previously reported, nivolumab (1 mg/kg) plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg) and nivolumab (3 mg/kg) plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg) were also assessed in the nonrandomized dose escalation cohort.11

The primary end point of this study was objective response rate (ORR) by blinded independent central review (BICR) assessment per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1.12 DOR by BICR, progression-free survival by BICR, OS, and safety were also evaluated as secondary end points. Tumor assessments were conducted at baseline, every 6 weeks for the first 24 weeks, and every 12 weeks thereafter until disease progression or treatment discontinuation. Survival was monitored every 3 months after treatment discontinuation. Safety was evaluated throughout the study, and adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

Tumor PD-L1 expression was assessed retrospectively in pretreatment (archival or fresh) tumor biopsy specimens with the use of a validated, automated immunohistochemical assay (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA) using a rabbit anti-human PD-L1 antibody (clone 28–8 [Epitomics Inc, Burlingame, CA]).13 Tumor PD-L1 expression was categorized as positive when staining of tumor cell membranes (at any intensity) was observed at prespecified expression levels (≥1% of tumor cells in a section that included ≥100 evaluable tumor cells).

The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each participating center. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization. Written informed consent was collected from all patients before enrollment. BMS policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/independent-research/data-sharing-request-process.html.

Statistical Analysis

Data included in this analysis were pooled from the nonrandomized and randomized cohorts. Analyses for efficacy were conducted as described previously.11 The safety profile of nivolumab was assessed in all treated patients through summaries and by-subject listings of deaths, serious AEs, AEs leading to discontinuation, overall AEs, and select AEs. The database lock date for this analysis was November 6, 2017.

Results

Patients and Treatment

In the pooled SCLC cohort of CheckMate 032, 109 patients (59 in the nonrandomized cohort and 50 in the randomized cohort) began receiving third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy between December 4, 2013, and November 30, 2016. Baseline patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Briefly, the median patient age was 64 years, 92.7% of patients were current or former smokers, and 56.0% were male. Approximately 17% of patients with quantifiable PD-L1 had 1% or higher tumor PD-L1 expression. Most of the patients (71.6%) were treated with two prior systemic treatment regimens; 22.9% were treated with three, and 5.5% with four or more. Prior platinum-based therapies included carboplatin in 67.0% of patients and cisplatin in 56.9% of patients. Nearly two-thirds of patients (65.1%) had platinum-sensitive SCLC (defined as a progression-free survival time of 90 days or more after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy), and one-third (33.9%) had platinum-resistant disease.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Treated with Third-or Later-Line Nivolumab Monotherapy

| Characteristic | Third- or Later-Line Nivolumab (n = 109) |

|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 64.0 (45–81) |

| ≥75 y, n (%) | 7 (6.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 61 (56.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 102 (93.6) |

| Black/African American | 4 (3.7) |

| Other | 3 (2.8) |

| Prior systemic treatment regimens, n (%) | |

| 2 | 78 (71.6) |

| 3 | 25 (22.9) |

| >3 | 6 (5.5) |

| First-line platinum-treated patients, n (%) | |

| Platinum-sensitivea | 71 (65.1) |

| Platinum-resistantb | 37 (33.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Current/former smoker | 101 (92.7) |

| Never smoker | 8 (7.3) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 32 (29.4) |

| 1 | 76 (69.7) |

| 2c | 1 (0.9) |

| Tumor PD-L1 expression, n (%) | |

| <1% | 65 (59.6) |

| ≥1% | 13 (11.9) |

| Not quantifiabled | 31 (28.4) |

Progression-free 90 or more days after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy.

Progression-free less than 90 days after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy.

Patients with an ECOG PS score of 2 or higher were not eligible for inclusion in this study. The patient who had an ECOG PS of 2 at baseline had a PS of 1 at screening and a PS of 2 at the first dosing date 15 days later.

Not evaluable, indeterminate, or missing.

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1.

At a minimum follow-up time of 11.9 months (median time from first dose to database lock 28.3 months), eight patients (7.3%) continued to receive third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy. Among patients who did not continue receiving nivolumab monotherapy, the most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression (74.3% [Supplementary Table 1]). The median duration of nivolumab monotherapy was 1.2 months (range 0.0 to 44.2+ [+ symbol indicates a censored value]).

Efficacy

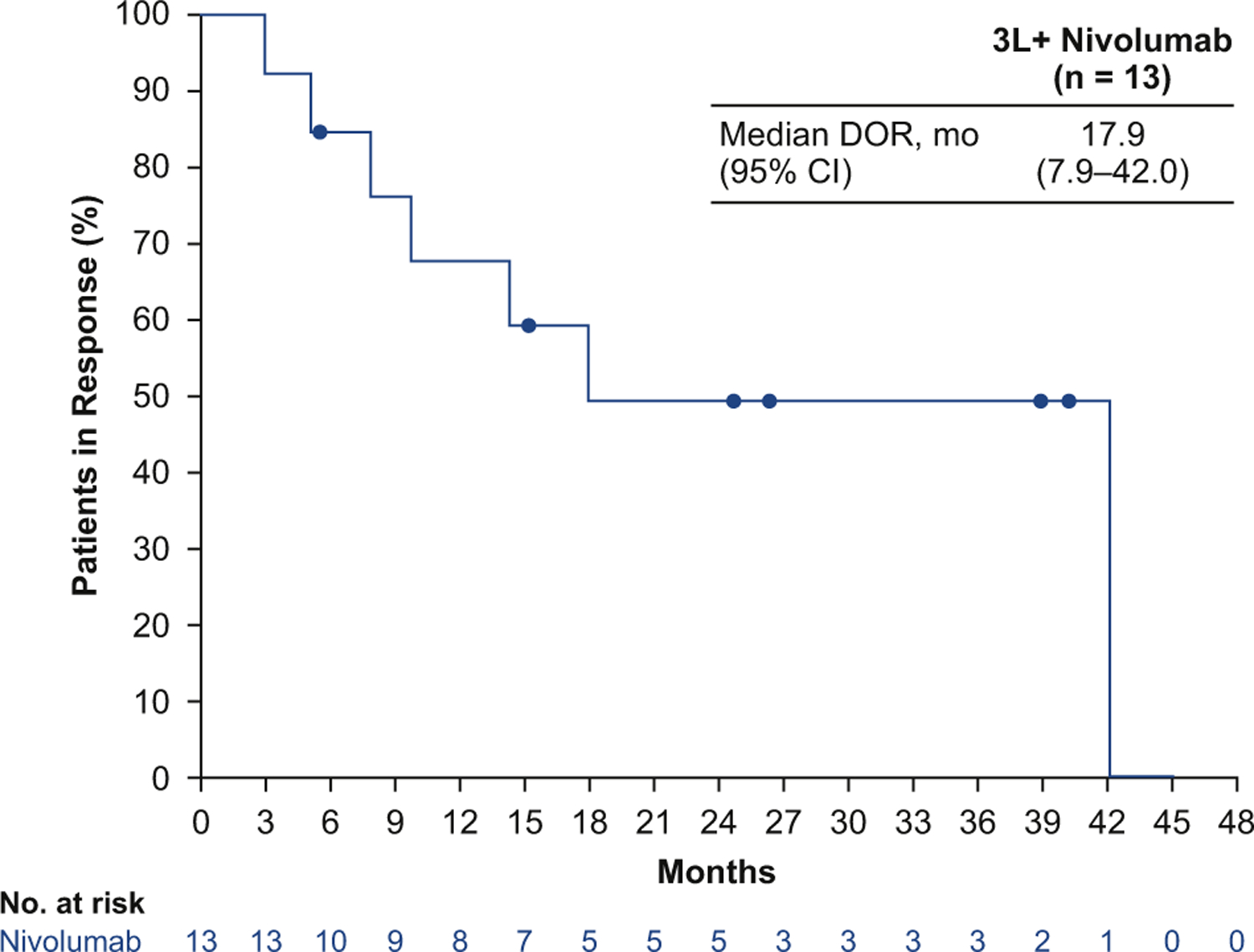

In 109 patients treated with third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy, the confirmed ORR was 11.9% (95% CI: 6.5–19.5) (Table 2). The median DOR was 17.9 months (95% CI: 7.9–42.0, range 3.0–42.1) (Fig. 1); the DOR was at least 12 months in 61.5% of patients with an objective response (Table 2). The response rates were similar across most patient subgroups, including among patients with tumor PD-L1 expression less than 1% and those with tumor PD-L1 expression of 1% or more; the only exception was observed for subgroups based on ECOG PS, in which ORR was higher in patients with an ECOG PS of 0 versus 1 (21.9% versus 6.6% [Supplementary Table 2]).

Table 2.

ORRs with Third-or Later-Line Nivolumab Monotherapy

| Endpoint | Third-or Later-Line Nivolumab (n = 109) |

|---|---|

| ORR by BICRa | |

| No. of patients | 13 |

| % of patients (95% CI) | 11.9 (6.5–19.5) |

| Best overall response, n (%) | |

| Complete response | 1 (0.9) |

| Partial response | 12 (11.0) |

| Stable disease | 25 (22.9) |

| Progressive disease | 56 (51.4) |

| Unable to determine | 14 (12.8) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.9) |

| Median time to response, mo | 1.6 |

| Duration of response | |

| ≥6 mo, n (%) | 10 (76.9) |

| ≥12 mo, n (%) | 8 (61.5) |

| Median (95% CI), mob | 17.9 (7.9–42.0) |

| Range, mo | 3.0–42.1 |

Per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1.

Computed by using the Kaplan-Meier method.

BICR, blinded independent central review; CI, confidence interval; ORR, objective response rate.

Figure 1.

Duration of response (DOR) by blinded independent central review with third- or later-line (3L+) nivolumab monotherapy. CI, confidence interval.

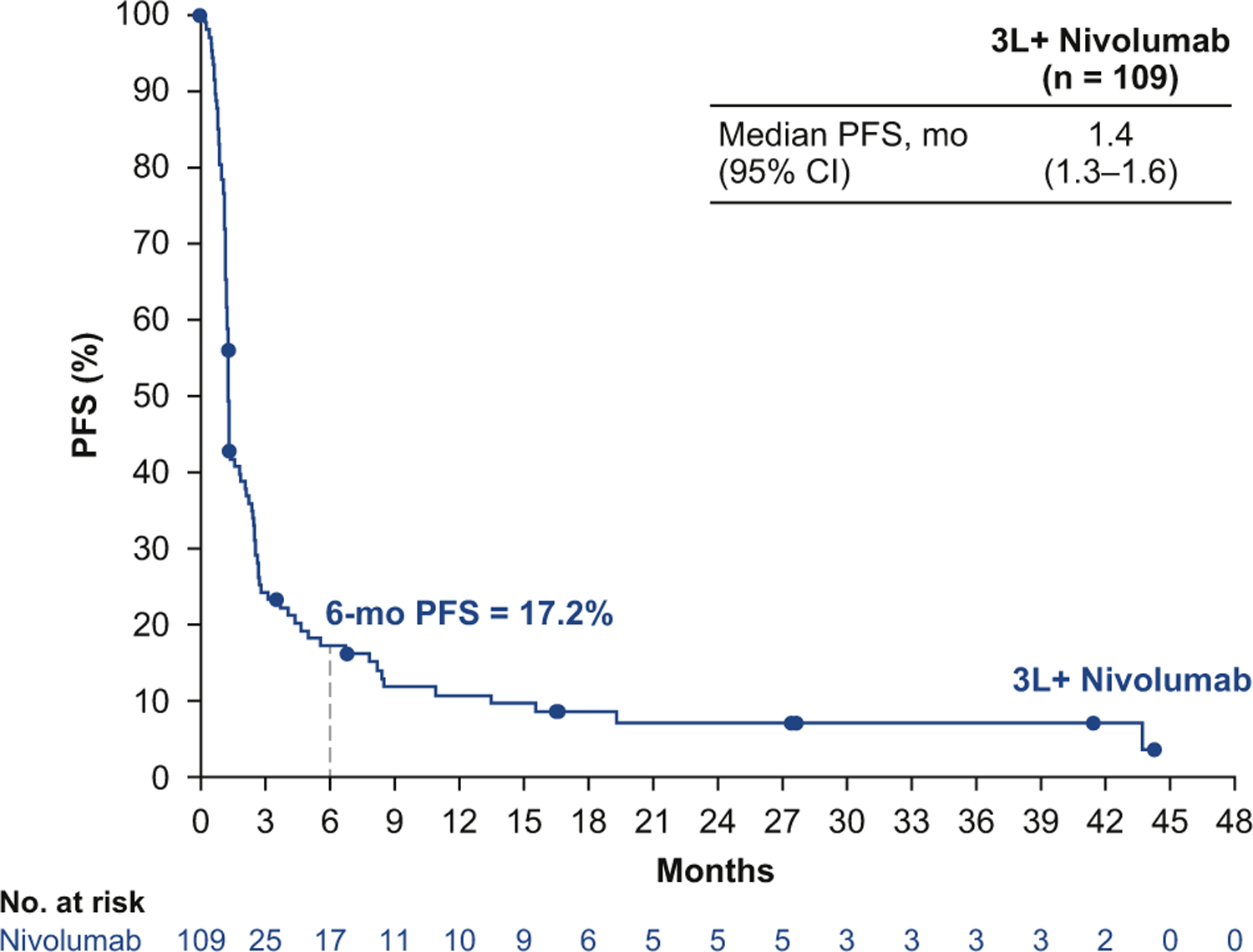

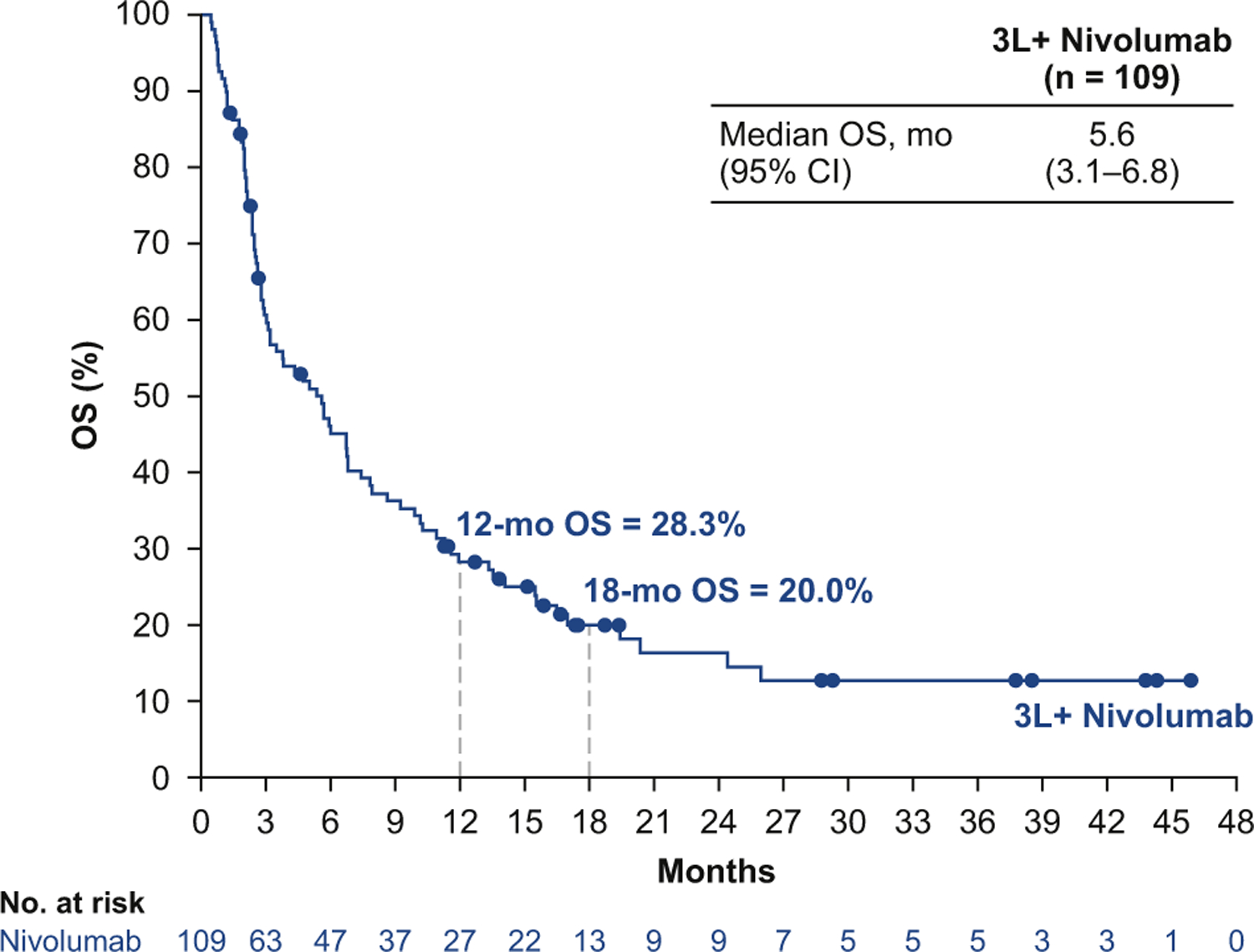

The median progression-free survival time in patients treated with third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy was 1.4 months (95% CI: 1.3–1.6), and 17.2% (95% CI: 10.7–25.1) of patients were progression-free at 6 months according to Kaplan-Meier estimates (Fig. 2). The median OS time was 5.6 months (95% CI: 3.1–6.8), with a 12-month OS rate of 28.3% (95% CI: 20.0–37.2) and an 18-month OS rate of 20.0% (95% CI: 12.7–28.6; Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival (PFS) by blinded independent central review with third- or later-line (3L+) nivolumab monotherapy. CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) with third- or later-line (3L+) nivolumab monotherapy. CI, confidence interval.

Safety

Any grade and grade 3 to 4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) with third- or later-line nivolumab monotherapy were reported in 55.0% and 11.9% of patients, respectively (Table 3). Three percent of patients discontinued treatment on account of TRAEs, all of which were grade 3 to 4. Most select TRAEs (defined as AEs with potential immunologic causes) were grade 1 to 2 (Supplementary Table 3). The most common select TRAEs of any grade were skin reactions (21.1%); the most frequent grade 3 to 4 select TRAEs were pulmonary events (1.8% [n = 2, both pneumonitis]). One treatment-related neurologic AE (grade 3–4 encephalitis) was reported. One treatment-related death due to pneumonitis was noted.

Table 3.

Treatment-Related Adverse Events

| Event, n (%) | Third-or Later-Line Nivolumab (n = 109) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Any Grade | Grade 3–4 | |

| Any event | 60 (55.0) | 13 (11.9) |

| Any serious event | 9 (8.3) | 8 (7.3) |

| Any event leading to discontinuation | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.8) |

| Most frequent events (≥5%) | ||

| Pruritus | 14 (12.8) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 11 (10.1) | 1 (0.9) |

| Nausea | 8 (7.3) | 0 |

| Rash | 7 (6.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| Diarrhea | 7 (6.4) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (5.5) | 1 (0.9) |

Data are based on a database lock date of November 6, 2017. Safety analysis included all patients who received at least one dose of the study drug. Includes events reported from the time of the first dose of study drug to 30 days after the last dose.

Discussion

In this analysis from CheckMate 032, nivolumab monotherapy resulted in an ORR by BICR in 11.9% of patients with recurrent limited-stage or extensive-stage SCLC who were previously treated with two or more chemotherapy regimens. Patients whose tumors were platinum refractory to first-line therapy were included, and there was no selection by biomarker such as tumor PD-L1 expression. Among patients who responded to nivolumab, 61.5% experienced durable DORs lasting at least 1 year (median DOR 17.9 months). Response rates were similar across most patient subgroups, except in subgroups based on ECOG PS, with ORR being higher in patients with an ECOG PS of 0 (21.9%) than in those with an ECOG PS of 1 (6.6%). Overall, nivolumab monotherapy was well tolerated, with a low (2.8%) rate of discontinuation due to TRAEs. These results supported the recent FDA approval of nivolumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic SCLC that progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy.

Patients who have received two or more previous lines of therapy for SCLC are often symptomatic from progression of cancer, side effects of previous therapy, and comorbidities. The choices for such patients in the past have included best supportive care with hospice, additional cytotoxic chemotherapy, and clinical trials. The current analysis addresses the need for data on patients with SCLC who have progressed after multiple lines of therapy. Reports have indicated that approximately 10% to 20% of patients who receive first-line chemotherapy will subsequently receive therapy in the third-line setting.14–16 The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines do not provide a specific recommendation for third- or later-line treatment; instead, they recommend enrollment in clinical trials as the preferred option.3 An area of unmet medical need in the third- or later-line treatment of SCLC is effective therapy that does not add to the side effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Nivolumab is listed among several other systemic therapy options in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, consistent with the recent FDA approval of nivolumab for the third- or later-line treatment of metastatic SCLC.

Data supporting third- or later-line therapies in patients with SCLC are limited to reports of real-world evidence. An international real-world, retrospective analysis evaluating third-line chemotherapy treatment in patients with SCLC (N = 120) reported a median OS time of 4.7 months and response rate of 18%; of note, DOR was not reported in this study.17 However in the study, responses were investigator determined, and the population included mostly patients with platinum-sensitive disease who received two different platinum-based chemotherapy combination regimens. Therefore, these data cannot be directly compared with the data in our analysis. In a recent analysis of a United States–based, real-world patient cohort that was matched to the CheckMate 032 population and received third-line therapy for SCLC (n = 92), the 1-year OS rate was 11% (poster to be presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer on September 23–26, 2018, in Toronto, Canada [abstract 13791]). Patients in this cohort did not receive third-line immunotherapy treatment, highlighting the benefit of nivolumab monotherapy reported in the present CheckMate 032 analysis (1-year OS rate 28.3%). The patients evaluated in this study of nivolumab were largely representative of the previously treated SCLC population, and to our knowledge, they represent the largest cohort of patients with recurrent SCLC treated with a third- or later-line immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Although results from several studies in patients with recurrent SCLC have recently been presented, few have reported data specifically in third-line populations. A subgroup analysis of the phase 2 TRINITY study in the third- or later-line population reported an independent review committee–assessed ORR of 16% (28 of 177) in biomarker-selected patients treated with third-line rovalpituzumab tesirine, which is an antibody-drug conjugate that targets delta like canonical notch ligand 3.18 The independent review committee–assessed DOR in this study was 4.1 months (95% CI: 3.0–4.2). Recently reported phase 1/2 studies of immuno-oncology agents included biomarker-unselected patients treated with at least one prior line of therapy, with ORRs ranging from 9.5% to 18.7% and landmark 1-year OS rates of 28% to 43%.11,19–21

Ideally, identifying subsets of patients more likely to benefit from treatment with nivolumab monotherapy remains an important research goal. Tumor PD-L1 expression is a biomarker for response to PD-1 inhibitors in patients with NSCLC22; however, as measured by using the validated Dako PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx assay, it did not appear to predict response to nivolumab in the present third- or later-line therapy analysis of CheckMate 032 or in an interim analysis of the second- or later-line nonrandomized cohort of this study.11 Emerging exploratory data from the KEYNOTE-158 study, which uses the combined positive score assay (includes tumor cells and intercalating immune cells that stain positive for PD-L1) suggest a potential role for PD-L1 expression in selecting patients with SCLC who may respond to PD-1 inhibitors.20

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) is also emerging as an independent biomarker of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in various cancer types, including SCLC, NSCLC, bladder cancer, and melanoma.23–33 In a separate analysis of the pooled nivolumab monotherapy cohort in CheckMate 032, the ORR was 21.3% in patients with a high TMB (≥248 mutations by whole exome sequencing) versus 4.8% in those with a low TMB (0 to <143 mutations).25 Future prospective evaluations of nivolumab monotherapy in a TMB-selected population with SCLC may help identify patients who are more likely to respond.

Patients with SCLC who have progressed despite multiple lines of treatment have few therapeutic options in the third line and beyond. Best supportive care, often including hospice, is the best choice for some patients in this setting. Clinical trials remain an important option in previously treated SCLC. Here, we have shown that clinically meaningful results are achievable with nivolumab monotherapy in a population with biomarker-unselected SCLC and an ECOG PS of 1 or lower, including patients with platinum-refractory disease. Responses to nivolumab are durable in the minority of patients who respond, with a tolerable safety profile. For patients who have received multiple lines of therapy for metastatic SCLC, nivolumab may provide an additional treatment option. Furthermore, these data warrant further investigation of immuno-oncology approaches in SCLC. Additional analyses of the randomized SCLC cohort of CheckMate 032, including patients treated with the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab, are underway and will be published separately. Phase 3 studies evaluating nivolumab alone and in combination with ipilimumab for SCLC as maintenance treatment after induction therapy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02538666) and nivolumab monotherapy for SCLC in the second-line setting (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02481830) are ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb. The authors thank the patients and their families, the participating clinical study teams (see the Supplementary Material for a full list of investigators), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Princeton, NJ), and ONO Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) for making this study possible; Ana Moreno for her contribution as protocol manager of this study; Stephanie Meadows Shropshire for contributions to the statistical analysis plan; and the staff of Dako for collaborative development of the PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx assay. All authors have contributed to and approved this article; writing and editorial assistance was provided by Stefanie Puglielli, PhD, of Evidence Scientific Solutions, Inc., with funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Ready has received personal fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, MedImmune, Merck, and Novartis. Dr. Farago has received grants from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Ignyta, Loxo Oncology, Merck, and PharmaMar; personal fees from AbbVie, Foundation Medicine, Loxo Oncology, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, PharmaMar, and Takeda; and research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb to her institution. Dr. Atmaca has received personal fees and grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Hellmann has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Janssen, Merck, Mirati, Novartis, and Shattuck Labs; he has received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb; and he has a pending patent (PCT/US2015/062208) filed by Memorial Sloan Kettering and related to the use of tumor mutational burden to predict response to immunotherapy. Dr. Schneider has received personal fees from and has stock ownership in Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Chau has received personal fees from Amgen, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Five Prime Therapeutics, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Oncology, and Taiho and research funding from Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Serono, and Sanofi Oncology. Dr. Hann has received personal fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Genentech and clinical research support from AbbVie and Bristol-Myers to her institution. Dr. Steele received personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Ms. Pieters and Mr. Fairchild are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Antonia has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck and has stock ownership in Cellular Biomedicine Group. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Data

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology at www.jto.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.10.003.

References

- 1.Byers LA, Rudin CM. Small cell lung cancer: where do we go from here? Cancer 2015;121:664–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarado-Luna G, Morales-Espinosa D. Treatment for small cell lung cancer, where are we now?—a review. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2016;5:26–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines) for small cell lung cancer. v.2 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sclc.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2018.

- 4.Demedts IK, Vermaelen KY, van Meerbeeck JP. Treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung carcinoma: current status and future prospects. Eur Respir J 2010;35: 202–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Pawel J, Schiller JH, Shepherd FA, et al. Topotecan versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine for the treatment of recurrent small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.[package insert]. Hycamtin (topotecan) for injection East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.[package insert]. Hycamtin (topotecan) capsules East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.[package insert]. Opdivo (nivolumab) Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vokes EE, Ready N, Felip E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057): 3-year update and outcomes in patients with liver metastases. Ann Oncol 2018;29:959–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gettinger S, Horn L, Jackman D, et al. Five-year follow-up of nivolumab in previously treated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: results from the CA209–003 study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1675–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonia SJ, Lopez-Martin JA, Bendell J, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17: 883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45: 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips T, Simmons P, Inzunza HD, et al. Development of an automated PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay for non–small cell lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2015;23:541–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Jong WK, ten Hacken NH, Groen HJ. Third-line chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2006;52:339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minami S, Ogata Y, Ihara S, Yamamoto S, Komuta. Retrospective analysis of outcomes and prognostic factors of chemotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2016;7:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartzberg L, Korytowsky B, Penrod J, et al. Developing a real-world 3L comparator to CheckMate 032: overall survival (OS) in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Abstract presented at: 19th World Conference on Lung Cancer (WCLC 2018) of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC). September 23–26, 2018; Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simos D, Sajjady G, Sergi M, et al. Third-line chemotherapy in small-cell lung cancer: an international analysis. Clin Lung Cancer 2014;15:110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carbone DP, Morgensztern D, Le Moulec S, et al. Efficacy and safety of rovalpituzumab tesirine in patients with DLL3-expressing, ≥ 3rd line small cell lung cancer: results from the phase 2 TRINITY study. Abstract presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology 54th Annual Meeting. June 1–5, 2018; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho D, Mahipal A, Dowlati A, et al. Safety and clinical activity of durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab in extensive disease small-cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC). Abstract presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology 54th Annual Meeting. June 1–5, 2018; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung HC, Lopez-Martin J, Kao S, et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab in advanced small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): KEYNOTE-158. Abstract presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 54th Annual Meeting June 1–5, 2018; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldman JW, Dowlati A, Antonia SJ, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of durvalumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated extensive disease small-cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC). Astract presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology 54th Annual Meeting. June 1–5, 2018; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shien K, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Wistuba II. Predictive biomarkers of response to PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors in non–small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2016;99:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2415–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, et al. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16:2598–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellmann MD, Callahan MK, Awad MM, et al. Tumor mutational burden and efficacy of nivolumab monotherapy and in combination with ipilimumab in small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;33: 853–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kowanetz M, Zou W, Shames D, et al. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) is associated with improved efficacy of atezolizumab in 1L and 2L+ NSCLC patients [abstract]. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12(suppl 1):S321–S322. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rizvi H, Sanchez-Vega F, La K, et al. Molecular determinants of response to anti–programmed cell death (PD)-1 and anti–programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer profiled with targeted next-generation sequencing. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:633–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2500–2501. 10.1056/NEJMc1713444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2093–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science 2015;350:207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2189–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016;387:1909–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powles T, Loriot Y, Ravaud A, et al. Atezolizumab vs chemotherapy in platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: immune biomarkers, tumor mutational burden and clinical outcomes from the phase III IMvigor211 study. Paper presented at: Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. February 8–10, 2018; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.