Abstract

Burnout is prevalent in medicine and has been further amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Strategies must be developed to reduce burnout by addressing a culture of wellness, efficiency of practice, and resiliency. The entire health-care community has a role in addressing burnout and promoting well-being.

Subject terms: Health care, Cardiology

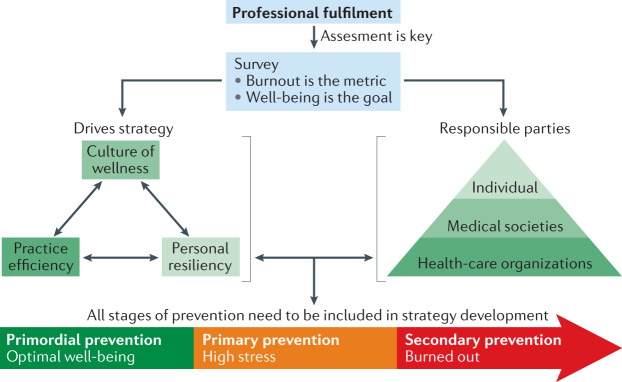

Burnout is an occupational hazard in medicine and affects more than one-quarter of US cardiologists and fellows in training1. The absence of burnout does not indicate well-being; however, along the continuum of clinician well-being, burnout is one of the more severe negative components. Clinician well-being is an imperative component of health care and can be broadly defined as experiencing wellness (optimized physical and mental health), resiliency and professional fulfilment. Burnout is not the result of an individual’s weakness but is due to workplace-related stresses, including excessive workload, moral injury and cognitive dissonance. Strategies must be developed both to address burnout and to improve and sustain clinician well-being. Similar to the concept of cardiovascular disease prevention, secondary prevention is accomplished with tactics directed to prevent recurrent burnout; however, targeted investment in primordial and primary prevention is also crucial to mitigate burnout and to cultivate esprit de corps2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Professional fulfilment strategy.

Survey assessment is key and drives the strategy for the development of a culture of wellness, practice efficiency and personal resiliency. Health-care organizations, medical societies and individuals each have a role in addressing well-being. All stages of prevention need to be included in the strategy development, from primordial prevention for those individuals with optimal levels of well-being, to primary prevention among those with high levels of stress, to secondary prevention among those who have experienced burnout.

Strategies must be developed both to address burnout and to improve and sustain clinician well-being

Ramifications of burnout

Tragic personal and professional consequences are associated with burnout, including broken relationships, substance abuse, depression and suicide2–5. Professional ramifications of burnout include lower quality of care, higher rates of medical errors, decreased patient satisfaction, decreased productivity and increased clinician turnover2,6–9.

Drivers of burnout

The advancements in technology, advent of electronic health records and rising legislative regulations place a tremendous burden on health-care workers, negatively affect well-being and work–life integration and contribute to high burnout rates in medicine. Workload and job demand, practice efficiency and resources, control over work, work–life integration, alignment of individual and organizational values, social support and community at work, and meaning in work are seven main drivers that can improve engagement or produce burnout among physicians10. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has placed additional unexpected demands on the health-care workforce, in terms of increased workload, increased mortality of patients and personal safety concerns.

Strategies to prevent burnout

Developing both organizational and personal strategies is necessary to transform the workplace to one that brings joy in work and professional fulfilment. However, understanding the current state of the workforce with the use of baseline assessment tools (for example, surveys and focus groups) is imperative. These assessments need to include questions on burnout and the organizational correlates of burnout and fulfilment. Also, regular and periodic survey assessments of burnout are necessary to document the effectiveness of implemented pilot projects. These results can provide guidance on directing the strategy and necessary tactics to improve well-being. Therefore, burnout is the metric to be measured and clinician well-being is the goal. The entire health-care community (health-care organization, individual clinicians and medical specialty society) has a role in addressing burnout and promoting well-being; however, the tactics will differ based on those roles.

The entire health-care community … has a role in addressing burnout and promoting well-being

Role of health-care organizations

Efforts by health-care organizations have largely focused on self-resiliency and stress management training to improve well-being, thereby focusing predominately on ‘fixing the employee’, with less emphasis on the systemic issues that influence the work environment. The Stanford Well MD model provides a holistic approach to addressing clinician well-being with the incorporation of three key components to achieve professional fulfilment: culture of wellness, practice efficiency and personal resiliency2.

A culture of wellness involves leadership support and alignment of values that promote self-care, infrastructure and resources for peer support and community development, and a culture of fairness and inclusivity.

Practice efficiency refers to workplace systems that promote teamwork models of practice, redesign inefficient workflows, improve the user experience with electronic health records, and engage efficient methods to improve work–life balance.

Resiliency includes an individual’s actions that contribute to emotional, physical and professional well-being, including promotion of self-care, self-compassion, social support, and safety net programmes for crisis intervention.

health-care organizations need to destigmatize clinicians’ access to mental health resources

These refinements in the work environment create highly functioning teams that are collaborative and efficient and provide value to the patients, the health-care organization and the cardiovascular workforce. Engaged leadership is imperative to identify burnout, develop tactics to improve the work environment and sustain esprit de corps. In addition, health-care organizations need to destigmatize clinicians’ access to mental health resources and refine hospital credentialing committee questions about mental health conditions because these can perpetuate underreporting and undertreatment of mental health conditions owing to the fear of professional ramifications.

Role of the individual

We all have a role in our personal well-being and need to reflect on the meaning of professional fulfilment. By understanding what brings us joy in medicine, we can work with our employers to find solutions. For example, adjusting schedules to spend at least 20% of the working week on what is most meaningful to individual physicians has been shown to be associated with lower rates of burnout2. Identification of practice inefficiencies and participation in process improvement enhance well-being for clinicians. Most importantly, development of individual self-compassion is essential. We need to treat ourselves in difficult situations with a similar compassionate response to that which we would give a colleague, friend or family member in comparable situations. And finally, individuals must participate in routine self-care, including accessing mental health services, when appropriate.

Role of medical specialty societies

Medical specialty societies have a duty to promote clinician well-being for the benefit of their members. Health-care workforce well-being should be incorporated into their strategic plans, and all actions taken should also be examined through the lens of well-being. Given the stigma associated with mental health conditions, medical societies must lead efforts to reduce stigma, including promoting legislation to reduce the stigma and increasing confidential access to mental health resources. Medical specialty societies need to advocate for licensing bodies and hospital credentialing to reform mental health reporting and its implications. Furthermore, a multipronged well-being approach would also include advocating for national and state legislative and health policy changes that mitigate drivers of burnout, developing specialty-specific tools that improve practice efficiency, lifelong learning in a timely and convenient manner, and facilitating a sense of community, diversity, inclusion and belonging for its members.

Call to action

The time has come for meaningful changes to be made. Here are several overarching recommendations for action.

We must acknowledge that burnout is an occupational adverse effect and not the fault of the individual.

Organizational strategies to address clinician well-being must extend beyond addressing self-resiliency. Efforts should shift to improving organizational culture and practice efficiencies.

Mental health conditions must be addressed in a safe, confidential and judgement-free manner.

More research is needed to provide guidelines and best practices for improving the culture of wellness, practice efficiency and resiliency in health care.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mehta LS, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among U.S. cardiologists. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;73:3345–3348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swenson, S. & Shanafelt, T. Mayo Clinic strategies to reduce burnout: 12 actions to create the ideal workplace (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- 3.Shanafelt TD, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch. Surg. 2011;146:54–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyrbye LN, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;149:334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oreskovich MR, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch. Surg. 2012;147:168–174. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017;177:1826–1832. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams ES, et al. Understanding physicians’ intentions to withdraw from practice: the role of job satisfaction, job stress, mental and physical health. 2001. Health Care Manage. Rev. 2010;35:105–115. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304509.58297.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, et al. Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:1127–1135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017;92:129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]