SUMMARY

OBJECTIVE :

To estimate the number and cost of hospitalizations with a diagnosis of active tuberculosis (TB) disease in the United States.

METHODS:

We analyzed the 2014 National In-Patient Sample using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes to identify hospitalizations with a principal (TB-PD) or any secondary discharge (TB-SD) TB diagnosis. We used a generalized linear model with log link and gamma distribution to estimate the cost per TB-PD and TB-SD episode adjusted for patient demographics, insurer, clinical elements, and hospital characteristics.

RESULTS:

We estimated 4985 TB-PD and 6080 TB-SD hospitalizations nationwide. TB-PD adjusted averaged $16695 per episode (95%CI $16168–$17221). The average for miliary/disseminated TB ($22498, 95%CI $21067–$23929) or TB of the central nervous system ($28338, 95%CI $25836–$30840) was significantly greater than for pulmonary TB ($14819, 95%CI $14284–$15354). The most common principal diagnoses for TB-SD were septicemia (n=965 hospitalizations), human immunodeficiency virus infection (n = 610), pneumonia (n=565), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis (COPD-B, n = 150). The adjusted average cost per TB-SD episode was $15909 (95%CI $15337–$16481), varying between $8687 (95%CI $8337–$9036) for COPD-B and $23335 (95%CI $21979–$24690) for septicemia. TB-PD cost the US health care system $123.4 million (95%CI $106.3–$140.5) and TB-SD cost $141.9 million ($128.4–$155.5), of which Medicaid/Medicare covered respectively 67.2% and 69.7%.

CONCLUSIONS:

TB hospitalizations result in substantial costs within the US health care system.

Keywords: active tuberculosis, in-patient care, health care cost, expected payer, insurance

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF :

Estimer le nombre et le coût des hospitalisations liées à un diagnostic de tuberculose (TB) aux Etats-Unis.

MÉTHODE :

Analyser l’échantillon national des patients hospitalisés de 2014 et les codes de l’International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) afin d’identifier les hospitalisations avec une TB comme diagnostic de sortie principal (TB-PD) ou secondaire (TB-SD). Nous avons utilisé un modèle linéaire généralisé avec lien de connexion et distribution gamma pour estimer le coût par épisode de TB-PD et TB-SD, ajusté aux caractéristiques des patients en termes de démographie, d’assurance, d’éléments cliniques et d’hôpital.

RÉSULTATS :

Nous avons estimé 4985 hospitalisations pour TB-PD et 6080 pour TB-SD dans tout le pays. Le coût ajusté de la TB-PD a été en moyenne de $16695 par épisode (IC95% 16168–17221). Le coût moyen d’une TB miliaire/disséminée ($22 498, IC95% 21067–23929) ou d’une TB du systéme nerveux central ($28 338, IC95% 25 836–30 840) a été significativement plus élevé que celui de la TB pulmonaire ($ 14819, IC95% 14284–15354). Les diagnostics principaux les plus fréquents de la TB-SD ont été une septicémie (n = 965 hospitalisations), une infection au virus de l’immunodéficience humaine (n = 610), une pneumonie (n = 565), et une broncho-pneumopathie chronique obstructive et une bronchectasie (BPCO-B; n = 150 hospitalisations). Le coût ajusté moyen par épisode de TB-SD a été de $15909 (IC95% 15337–16481), variant de $8687 (IC95% 8337–9036) pour les BPCO-B à $23335 (IC95% 21 979–24690) pour une septicémie. Le coût de la TB-PD dans le système de santé des Etats-Unis atteint 123,4 millions (IC95% 106,3–140,5) de dollars et celui de la TB-SD, 141,9 millions (IC95% 128,4–155,5) de dollars, dont Medicaid et Medicare a couvert 67,2% et 69,7%, respectivement.

CONCLUSION :

Les hospitalisations pour TB ont un coût substantiel en termes de services de santé au sein du système de soins de santé américain.

RESUMEN

OBJETIVO:

Estimar el número de hospitalizaciones con un diagnóstico de tuberculosis (TB) activa y su costo en los Estados Unidos.

MÉTODOS:

Se analizó una muestra nacional de pacientes hospitalizados en el 2014, utilizando los códigos de la International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) con el fin de reconocer las hospitalizaciones donde el diagnóstico principal de alta fue TB activa (TB-PD) y aquellas con TB activa como alguno de los diagnósticos secundarios de alta (TB-SD). Se aplicó un modelo lineal generalizado con función de enlace logarítmica y distribución con el objeto de estimar el costo por episodio de TB-PD y de TB-SD ajustado con respecto a las características demográficas, la aseguradora y las características clínicas del paciente y las características del hospital.

RESULTADOS:

Se calcularon 4985 hospitalizaciones con TB-PD y 6080 con TB-SD en todo el país. El promedio ajustado por episodio de TB-PD fue 16695 dólares (IC95% 16168–17221). El costo promedio por episodio de TB miliar o diseminada (22498 dólares; IC95% 21067–23929) o por TB del sistema nervioso central (28338 dólares; IC95% 25836–30840) fue significativamente mayor que por episodio de TB pulmonar (14819 dólares; IC95% 14284–15354). Los diagnósticos principales más frecuentes en los casos de TB-SD fueron septicemia (n = 965 hospitalizaciones), infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (n = 610), neumonía (n = 565), enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica y bronquiectasias (EPOC-B; n = 150 hospitalizaciones). El costo promedio ajustado por episodio de TB-SD fue 15909 dólares (IC95% 15337–16481) y osciló entre 8687 dólares (IC95% 8337–9036) en caso de EPOC-B y 23335 dólares (IC95% 21979–24690) en caso de septicemia. En el 2014, los casos de TB-PD costaron al sistema de salud de los Estados Unidos 123,4 millones de dólares (IC95% 106,3–140,5 millones) y los de TB-SD costaron 141,9 millones de dólares (IC95% 128,4–155,5 millones), de los cuales Medicaid cubrió el 67,2% y Medicare el 69,7%.

CONCLUSIÓN:

Las hospitalizaciones por TB originan costos considerables al sistema de salud de los Estados Unidos.

GUIDELINES1 FOR THE CLINICAL management of Mycobacterium tuberculosis disease that is not resistant to both rifampin and isoniazid (98.7–99.1% of reported tuberculosis [TB] cases2) typically recommend a 6-month regimen of chemotherapy administered predominantly in ambulatory settings.2,3 However, TB is often treated for longer. For example, the recommended minimum length of treatment for multidrug-resistant TB is 18–24 months, for TB resistant to rifampin it is 12–18 months, and it varies between 9 and 12 months for TB with a slow response to treatment or for certain extra-pulmonary TB sites.1

For all forms of TB, most of the direct costs of treating the disease result from hospitalization,4,5 as nearly half (49%)5 of TB patients are hospitalized at least once to initiate/change their treatment, manage adverse reactions to medication, or manage severe worsening of TB disease.6 Furthermore, an average hospitalization for different types of TB can last from nearly 2 weeks (11–17 days)5–7 to as much as 12 months (for extensively drug-resistant TB).6,8

During the last decade, several studies have estimated the cost of TB hospitalization episodes in the United States.7,9,10 However, these included active TB, along with non-TB disease (e.g., personal history of TB or primary tuberculous infection),7 focused on a limited number of TB disease sites,10 or only presented estimates for populations covered by private insurance (a minority of TB patients).9 Our study used nationally representative data and a comprehensive categorization scheme to identify all hospitalization episodes with a recorded principal or any secondary diagnosis of active TB in 2014 and estimated per episode and total hospitalization costs.

The nationally representative estimates of per episode and total hospitalization costs add important information for determining the overall economic burden of TB in the United States. Furthermore, estimates of in-patient TB care will inform the efforts of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and TB control programs to advance TB elimination in the United States. Elimination of the disease has been a national TB policy goal since 1989.11 Slower declines in TB in recent years call for revised strategies to accelerate progress toward disease elimination.11,12 Estimates of the cost of current TB treatment activities are critical for evaluating the cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit of alternative TB elimination strategies, such as scaled-up uptake of latent tuberculous infection (LTBI) testing and treatment in high-risk populations or increased adoption of short-course LTBI treatment regimens.12,13 A clearer understanding of the cost of TB control and prevention will allow TB programs to best allocate their limited resources.

METHODS

Data

The 2014 data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National In-Patient Sample (NIS) were analyzed for this study.14 In 2014, the NIS sampled 20% of discharges from all US hospitals, excluding federal, rehabilitation, and long-term acute care hospitals (defined in Table 1),15 and contained 7.1 million unweighted or 35.4 million weighted observations.14 For each hospitalization, the NIS included the ‘principal’ (or first-listed) diagnosis occasioning hospital admission and up to 29 secondary diagnoses. The database also included total hospital charges (without hospital-based physician fees),15 hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios (CCRs), primary insurer, patient demographics, clinical elements, and hospital characteristics.

Table 1.

Definition of the variables (Source:14)

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cost of a hospitalization episode | Reported total charges15 in 2014 US dollars multiplied by the 2014 hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios,16 obtained from hospital accounting reports collected by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

| Patient characteristics | |

| Sex | Male/female identifier15 |

| Race/ethnicity | Race/ethnicity identifier; categorized as White (non-Hispanic), Black (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, other, missing/invalid15 |

| Age | Patient’s age in years;15 categorized as <15, 15–44, ⩾45 years |

| Insurance | Primary expected payer identifier; categorized as private insurance (Blue Cross/Blue Shield, other commercial carriers, private health maintenance and preferred provider organizations), Medicaid, Medicare, other government (Worker’s Compensation, Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services, Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, etc.), and uninsured patients (‘self-pay’ and ‘no charge’)15. |

| Median household income | Median household income in the patient’s zip code in 2014 US dollars; categorized by year-specific income quartiles (2014 Q1, $1–39 999; 2014 Q2 $40 000–50 999; 2014 Q3 $51 000–65 999; 2014 Q4 ⩾ $66 000; missing/invalid)15 |

| Urban-rural identifier | Urbanicity identifiers developed by the National Center for Health Statistics, categorized as metro areas of >1 million population, fringe counties in metro areas of >1 million population, counties in metro areas of 250 000–999 999 population, counties in metro areas of 50 000–249 999 population, micropolitan counties, not metropolitan or micropolitan counties, missing/invalid15 |

| Clinical elements | |

| Discharge status | Patient’s discharge disposition identifier (dead/alive)15 |

| Number of chronic conditions | Count of unique chronic diagnoses reported on discharge. A chronic condition was defined as a condition that lasted ⩾12 months and met one or both of the following tests: 1) it placed limitations on self-care, independent living, and social interactions; 2) it resulted in the need for ongoing intervention with medical products, services, and special equipment15 |

| Number of procedures | Total number of ICD-9-CM procedures coded on the discharge record15 |

| Length of stay | Length of stay in days, calculated by subtracting the admission date from the discharge date (same-day stays were coded as zero)15 |

| Major operating room procedure | Indicator of a major operating room procedure reported on the discharge record15 |

| Hospital characteristics | |

| Ownership | Hospital’s ownership identifier as obtained from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals.15 Categorized as non-profit15 (i.e., hospitals aimed to provide community benefits and exempt from federal income tax or state/local property taxes17), private invest-own15 (i.e., for-profit institutions owned by corporations, individuals, or partnerships17), and government non-federal15 (i.e., entities owned by the state and local governments17) |

| Note: The National In-patient Sample excluded15 federal hospitals (i.e., serving federal beneficiaries such as military personnel, veterans, or Native Americans17), rehabilitation hospitals (i.e., providing minimum 3 h of intense rehabilitation services per day18), and long-term acute care hospitals (i.e., having an average in-patient length of stay >25 days19) | |

| Census region | Hospital’s census region as obtained from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals; categorized as Northeast (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont); Midwest (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin), South (Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia); or West (Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming)15 |

| Size | Hospital’s size identifier; categorized as small, medium, or large based on the number of short-term acute care beds set up and staffed in a hospital.15 Hospital size is specific to census region, urbanicity, and teaching status.* Hospitals in the Northeast have the largest number of beds per category: small (rural) 1–49 beds, small (urban, non-teaching) 1–124, small (urban, teaching) 1–249; medium (rural) 50–99, medium (urban, non-teaching) 125–199, medium (urban, teaching) 250–424; large (rural) >100, large (urban, non-teaching) >200, and large (urban, teaching) >425. Hospitals in the West have the smallest number of beds per category: small (rural) 1–24 beds, small (urban, non-teaching) 1–99, small (urban, teaching) 1–199; medium (rural) 25–44, medium (urban, non-teaching) 100–174, medium (urban, teaching) 200–324; large (rural) 45+, large (urban, non-teaching) >175, and large (urban, teaching): >32515 |

A teaching hospital has a residency program approved by the American Medical Association, is a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals, or has a ratio of full-time equivalent interns and residents to beds of ⩾0.25.15

Q = quarter; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

As the 2014 NIS eliminated all patient and state identifiers,14 institutional review board approval of the study was not required.20

Tuberculosis-related hospitalizations and their cost

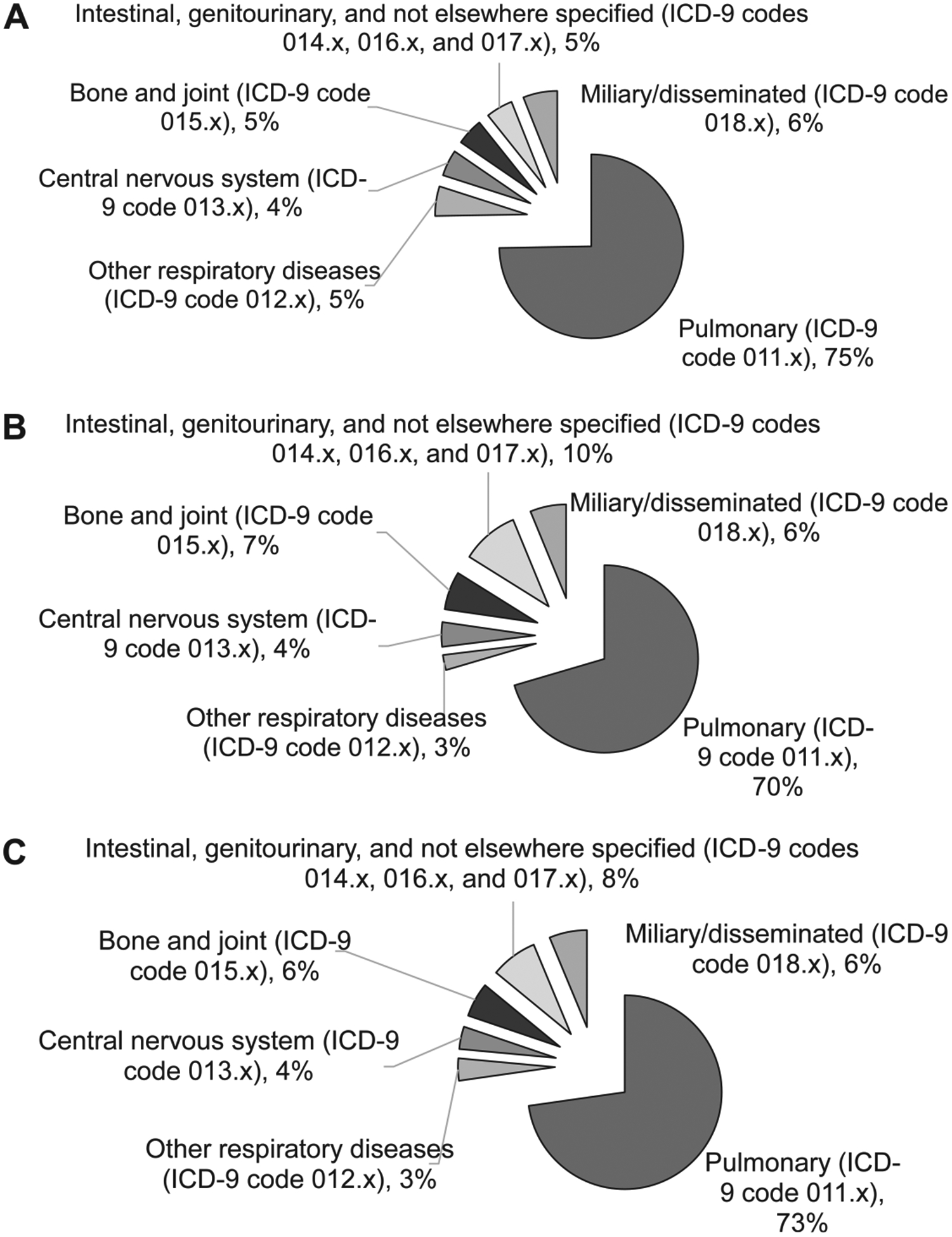

TB-related hospitalizations were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9)21 codes 011.x–018.x (Figure 1). The presence of principal diagnosis with these codes indicated hospitalizations principally for TB (TB-PD).4,9 Similarly, hospitalizations with TB noted as any secondary diagnosis (TB-SD) indicated hospitalizations with such ICD-9 codes on any of 29 secondary diagnoses.7 To avoid double counting of hospitalizations with TB noted as both principal and any secondary diagnosis, we classified such episodes only as TB-PD. For TB-SD hospitalizations, we identified principal non-TB diagnoses using HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, USA) for the ICD-9 Categorization Scheme.22 For each hospitalization, we computed the actual costs of hospital services (in 2014 US dollars) by multiplying the reported total charges by 2014 hospital-specific CCRs,16 obtained from hospital accounting reports collected by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Baltimore, MD, USA).

Figure 1.

Hospitalization episodes with TB noted as a principal or secondary diagnosis, United States, 2014 (n = 11 065).* (Source:14). A) TB noted as a principal diagnosis (n = 4985); B) TB noted as any secondary diagnosis (n=6515); C) TB noted as a principal or any secondary diagnosis (n = 11 065). *Principal or any secondary diagnoses include 4985 TB-PD hospitalizations, 6080 exclusively TB-SD hospitalizations, and 435 observations with TB noted as both principal and any secondary diagnoses (classified as TB-PD in this study). ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision;21 TB=tuberculosis; TB-PD=TB principal diagnosis; TB-SD=TB secondary diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

To account for the sampling design of NIS data, we used Stata v 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) prefix command ‘svy’ to estimate weighted frequencies, unadjusted averages and total costs. Total costs were calculated by adding up the costs of TB-PD or TB-SD hospitalizations for the weighted sample. The adjusted average costs per episode were estimated using a generalized linear model with log link and gamma distribution, which accounted for positive, highly skewed and right-tailed cost data. The covariates included primary expected payer, patient’s sociodemographic characteristics, patient’s clinical elements, and hospital characteristics.15,17–19 All covariates are listed and defined in Table 1. To reduce potential multicollinearity that can affect the magnitude and statistical significance of coefficients,23 we computed correlations of estimated coefficients and variance inflation factor (VIF) and included only covariates with VIF <10.23,24 Given the log-link specification, we reported exponentiated coefficients eβ, where (eβ −1)*100 represented the percentage change in costs per unit change in covariates when compared to the reference group.9 All results were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

RESULTS

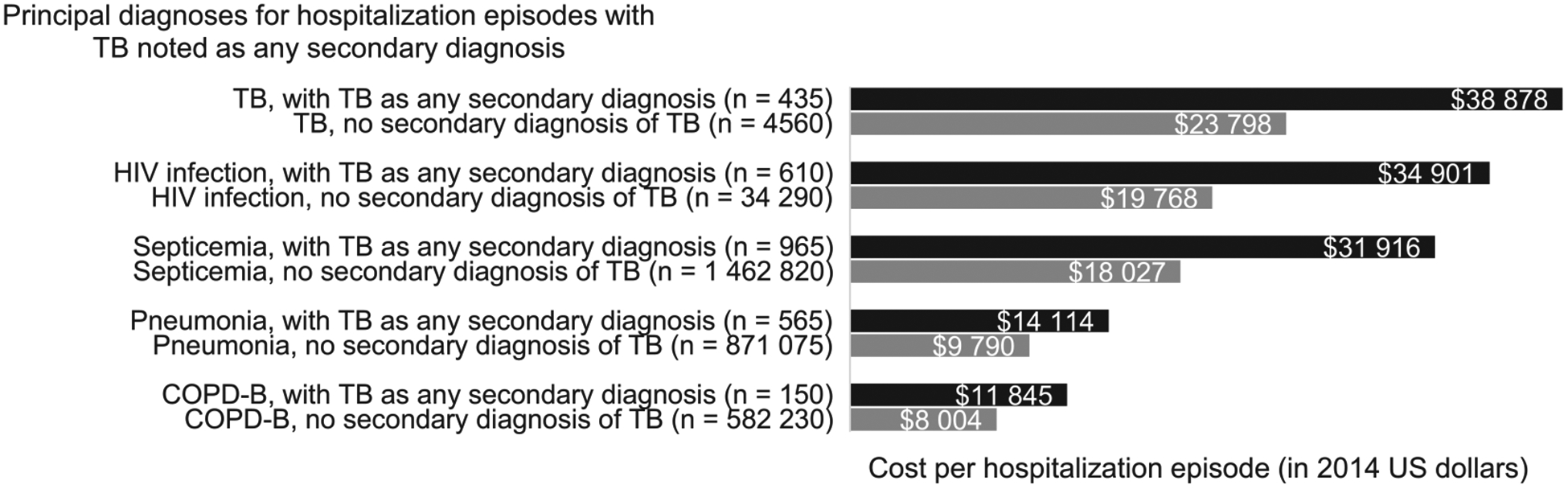

In 2014, we estimated 11065 hospitalizations nationwide with TB noted as principal or any secondary diagnosis, including 4985 TB-PD hospitalizations, 6515 TB-SD hospitalizations, and 435 hospitalizations with TB noted as both TB-PD and TB-SD (Figure 1). Nearly three quarters of both TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalizations (74.7% and 70.5%, respectively) were for pulmonary TB (PTB), whereas other TB forms each accounted for 4–9% of TB-PD hospitalizations. If TB was noted as any secondary diagnosis, then the most common principal diagnoses were septicemia (14.8%, number of hospitalizations 965), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (9.4%, n = 610), pneumonia (8.7%; n = 565), TB (6.7%; n = 435), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis (COPD-B; 2.3%; n=150). Overall, these five conditions accounted for 41.9% of all TB-SD hospitalizations. Of all hospitalizations with these five conditions noted as principal diagnosis, episodes with secondary diagnoses of TB had a 50–80% higher unadjusted cost of hospitalization than episodes without secondary diagnoses of TB (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hospitalization episodes with and without tuberculosis noted as any secondary diagnosis: unadjusted average cost per hospitalization episode, United States, 2014 (Source:14). TB (ICD-9 codes 0.11.x-0.18.x),21 HIV infection (CCS code 5), septicemia (CCS code 2), pneumonia (CCS code 122), and COPD-B (CCS code 127) account for nearly 42% of all hospitalization episodes with TB noted as any secondary diagnosis.22 Hospitalizations with TB noted as any secondary diagnosis include 6080 exclusively TB-SD hospitalizations and 435 observations with TB noted as both principal and any secondary diagnoses (classified as TB-PD in this study). TB=tuberculosis; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; COPD-B=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis; ICD-9=International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; CCS=Clinical Classifications Software; TB-PD=TB principal diagnosis; TB-SD=TB secondary diagnosis.

For all 11065 TB-related hospitalizations, the majority of patient, visit, and hospital characteristics were similar (Table 2). TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalizations occurred predominantly among males (65.9% and 61.6%, respectively), persons aged ⩾45 years (57.0% and 73.2%), and Medicaid (33.6% and 31.8%) or Medicare (22.6% and 35.0%) recipients. TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalizations had an average of 3.5–5.6 chronic conditions, 1.7–2.3 procedures, and a length of stay of 11–15 days. Both TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalizations were recorded predominantly in private non-profit (58.2% and 65.3%, respectively), large (56.8% and 56.3%) hospitals, located in the South (39.5% and 40.0%) or West (29.7% and 28.6%, respectively). The majority of TB-PD hospitalizations occurred amongHispanics (27.0%), whereas most TB-SD hospitalizations occurred among Whites (30.9%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of hospitalization episodes with a diagnosis of TB, United States, 2014 (Source:14)

| Episodes principally for TB % | Episodes with TB as secondary diagnoses % | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of hospitalization episodes | 4 920* | 5 890† |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Female sex | 34.1 | 38.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 18.2 | 30.9 |

| Black | 20.4 | 23.9 |

| Hispanic | 27.0 | 20.8 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 19.5 | 14.7 |

| Native American | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| Other | 8.8 | 5.9 |

| Missing/invalid | 4.5 | 3.1 |

| Age, years | ||

| <15 | 4.6 | 1.8 |

| 15–44 | 38.4 | 25.0 |

| ⩾45 | 57.0 | 73.2 |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 20.9 | 16.7 |

| Medicare | 22.6 | 35.0 |

| Medicaid | 33.6 | 31.8 |

| Other government | 5.3 | 3.3 |

| Uninsured | 17.7 | 13.2 |

| Median household income, US$ | ||

| 1–39 999 | 34.7 | 36.3 |

| 40 000–50 999 | 26.8 | 23.9 |

| 51 000–65 999 | 18.4 | 19.3 |

| ⩾66 000 | 16.4 | 15.7 |

| Missing/invalid | 3.7 | 4.8 |

| Urban-rural identifier | ||

| Central counties in metro areas of >1 million population | 53.6 | 47.3 |

| Fringe counties in metro areas of >1 million population | 17.5 | 18.6 |

| Counties in metro areas of 250 000–999 999 population | 16.3 | 17.4 |

| Counties in metro areas of 50 000–249 999 population | 4.8 | 6.5 |

| Micropolitan counties | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| Not metropolitan or micropolitan counties | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Missing/invalid | 1.1 | 2.6 |

| Clinical elements | ||

| Proportion who died during hospitalization | 2.1 | 7.1 |

| Average number of chronic conditions on a record | 3.5 | 5.6 |

| Average number of procedures on a record | 1.7 | 2.3 |

| Mean length of stay, days | 15.6 | 10.9 |

| Proportion with major operating room procedure on a record | 20.1 | 22.2 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||

| Ownership | ||

| Government, non-federal | 27.2 | 20.8 |

| Private, not-profit | 58.2 | 65.3 |

| Private, invest-own | 14.6 | 13.9 |

| Size | ||

| Small | 16.0 | 16.4 |

| Medium | 27.2 | 27.3 |

| Large | 56.8 | 56.3 |

| Census region | ||

| Northeast | 19.1 | 17.8 |

| Midwest | 11.7 | 13.6 |

| South | 39.5 | 40.0 |

| West | 29.7 | 28.6 |

Excludes 65 observations with the cost of hospitalization missing.

Excludes 190 observations with the cost of hospitalization missing and 435 observations with TB noted as both principal and any secondary diagnoses (classified as TB-PD in this study).

TB = tuberculosis; TB-PD = TB principal diagnosis.

Cost of tuberculosis-related hospitalizations

For both TB-PD and TB-SD episodes (Table 3), the adjusted average cost of hospitalization increased with the length of stay (by 3.2% and 4.2% per day, respectively; P < 0.001) and the number of chronic conditions (3.7% and 3.6% per condition; P < 0.001) or procedures (9.9% and 11.0% per procedure; P < 0.001). Having a major operating room procedure increased hospitalization cost by 43.6% for TB-PD and 40.2% for TB-SD (P < 0.001). In TB-PD hospitalizations, the cost of treating patients from the wealthiest communities (income $66000+ annually) was higher (12.7%, P = 0.02) than for patients from the poorest areas (income ⩽$40000). However, among all TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalizations adjusted for length of stay and patient chronic conditions, there was no statistically significant difference in hospitalization costs by race/ethnicity, age, or primary insurer.

Table 3.

Summary results of the multivariable regression analyses used to determine the adjusted cost for hospitalization episodes with a diagnosis of TB, United States, 2014 (Source:14)

| Episodes principally for TB (n = 4 920)* exp(β) (95%CI) | Episodes with TB as secondary diagnoses (n = 5 890)† exp(β) (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Males | Referent | Referent |

| Females | 0.926 (0.866–0.990)‡ | 0.943 (0.881–1.009) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 1.033 (0.924–1.154) | 0.976 (0.891–1.068) |

| Hispanic | 1.025 (0.922–1.139) | 0.990 (0.893–1.097) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.107 (0.993–1.233) | 1.003 (0.896–1.124) |

| Native American | 0.838 (0.700–1.005) | 1.119 (0.822–1.523) |

| Other | 1.062 (0.922–1.222) | 1.002 (0.879–1.141) |

| Missing/invalid | 1.140 (0.953–1.364) | 1.066 (0.875–1.299) |

| Age, years | ||

| <15 | Referent | Referent |

| 15–44 | 0.978 (0.757–1.264) | 0.941 (0.693–1.278) |

| ⩾45 | 0.917 (0.708–1.186) | 0.940 (0.700–1.261) |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | Referent | Referent |

| Medicare | 1.051 (0.957–1.154) | 0.968 (0.877–1.068) |

| Medicaid | 1.040 (0.949–1.140) | 1.010 (0.913–1.117) |

| Other government | 0.839 (0.702–1.003) | 0.936 (0.777–1.129) |

| Uninsured | 1.019 (0.932–1.114) | 1.052 (0.927–1.193) |

| Median household income | ||

| 1–39 999 | Referent | Referent |

| 40 000–50 999 | 0.961 (0.891–1.037) | 1.062 (0.967–1.165) |

| 51 000–65 999 | 0.976 (0.895–1.064) | 0.954 (0.872–1.043) |

| ⩾66 000 | 1.127 (1.023–1.241)‡ | 1.105 (0.999–1.222) |

| Missing/invalid | 0.909 (0.749–1.104) | 0.939 (0.763–1.156) |

| Urban-rural identifier | ||

| Central counties in metro areas of >1 million population | Referent | Referent |

| Fringe counties in metro areas of >1 million population | 0.958 (0.878–1.045) | 0.961 (0.882–1.048) |

| Counties in metro areas of 250 000–999 999 population | 0.923 (0.841–1.013) | 0.896 (0.806–0.996)‡ |

| Counties in metro areas of 50 000–249 999 population | 0.906 (0.753–1.089) | 0.857 (0.746–0.985)‡ |

| Micropolitan counties | 0.869 (0.776–0.972)‡ | 0.979 (0.854–1.121) |

| Not metropolitan or micropolitan counties | 1.047 (0.864–1.270) | 0.995 (0.813–1.216) |

| Missing/invalid | 0.846 (0.538–1.332) | 1.261 (0.950–1.675) |

| Clinical elements | ||

| Discharge status | ||

| Alive | Referent | Referent |

| Died | 1.221 (0.974–1.531) | 1.247 (1.092–1.425)§ |

| Number of chronic conditions | 1.037 (1.023–1.052)§ | 1.036 (1.024–1.048)§ |

| Number of procedures | 1.099 (1.066–1.133)§ | 1.110 (1.089–1.131)§ |

| Length of stay, days | 1.032 (1.027–1.038)§ | 1.042 (1.035–1.049)§ |

| Major operating room procedure | ||

| No | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 1.436 (1.282–1.608)§ | 1.402 (1.285–1.530)§ |

| Hospital characteristics | ||

| Ownership | ||

| Government, non-federal | Referent | Referent |

| Private, not-profit | 0.852 (0.784–0.926)§ | 0.881 (0.787–0.987)‡ |

| Private, invest-own | 0.753 (0.685–0.827)§ | 0.815 (0.707–0.941)§ |

| Size | ||

| Small | Referent | Referent |

| Medium | 1.011 (0.915–1.116) | 0.862 (0.781–0.951)§ |

| Large | 1.001 (0.915–1.096) | 0.881 (0.804–0.966)§ |

| Census region | ||

| Midwest | Referent | Referent |

| Northeast | 1.202 (1.064–1.357)§ | 1.088 (0.962–1.229) |

| South | 0.911 (0.820–1.012) | 1.017 (0.908–1.114) |

| West | 1.364 (1.217–1.530)§ | 1.338 (1.174–1.525)§ |

| Hospitalizations principally for TB | ||

| Pulmonary | Referent | |

| Other respiratory | 1.082 (0.959–1.221) | |

| Central nervous system | 1.303 (1.071–1.585)§ | |

| Bone and joint | 0.921 (0.785–1.081) | |

| Intestinal, genitourinary, and not elsewhere specified | 1.018 (0.870–1.192) | |

| Miliary/disseminated | 1.153 (1.029–1.292)‡ | |

| Constant | 7 597.792 (5 529.871–10 439.020)§ | 7 424.492 (5 051.094–10 913.100)§ |

Excludes 65 observations with the cost of hospitalization missing.

Excludes 190 observations with the cost of hospitalization missing and 435 observations with TB noted as both principal and any secondary diagnoses (classified as TB-PD in this study).

Statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Statistically significant at P < 0.01.

TB = tuberculosis; CI = confidence interval; TB-PD = TB principal diagnosis.

Overall, the adjusted average cost per TB-PD hospitalization (Tables 3 and 4) was $16 695 (95%CI $16168–$17221), which varied significantly by TB disease site and geography. Hospitalization cost for miliary/disseminated TB ($22498, 95%CI $21067–$23929; P=0.014) and for central nervous system TB ($28338, 95%CI $25836–$30840; P = 0.008) was significantly greater than for PTB alone ($14819, 95%CI $14284–$15354). Hospitalizations in the West ($23 302, 95%CI $21 992–$24611) or Northeast ($21036, 95%CI $19833–$22238) were nearly twice (P < 0.001 and P=0.003, respectively) as expensive as hospitalizations in the Midwest ($12879, 95%CI $11937–$13820).

Table 4.

Adjusted, unadjusted average, and total cost of hospitalization episodes with a diagnoses of TB by disease type, insurer, and census region, United States, 2014, US$ (Source:14)

| Episodes n | Length of stay days (95%CI) | Unadjusted average cost per episode US$ (95%CI) | Adjusted average cost per episode* US$ (95%CI) | Total cost million dollars US$ (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations principally for TB | |||||

| All | 4920 | 15.6 (13.9–17.4) | 25 080 (22 465–27 695) | 16 695 (16 168–17 221) | 123.4 (106.3–140.5) |

| By site of TB disease | |||||

| Pulmonary | 3680 | 15.4 (13.4–17.4) | 22 175 (19 499–24 850) | 14 819 (14 284–15 354) | 81.6 (69.3–93.9) |

| Other respiratory | 260 | 12.4 (9.8–15.1) | 22 903 (17 904–27 902) | 18 056 (17 048–19 064) | 6.0 (5.0–6.9) |

| Central nervous system | 220 | 22.3 (13.7–30.9) | 45 574 (31 467–59 681) | 28 338 (25 836–30 840) | 10.0 (8.2–11.8) |

| Bone and joint | 235 | 16.5 (10.3–22.7) | 41 762 (26 310–57 214) | 20 568 (19 474–21 663) | 9.8 (5.9–13.8) |

| Intestinal, genitourinary, and not elsewhere specified | 230 | 12.5 (9.8–15.3) | 26 458 (230 986–31 929) | 19 172 (18 353–19 991) | 6.1 (5.0–7.2) |

| Miliary/disseminated | 295 | 17.8 (12.3–23.3) | 33 597 (23 463–43 730) | 22 498 (21 067–23 929) | 9.9 (7.2–12.6) |

| By primary insurer | |||||

| Private | 1015 | 12.1 (10.2–13.9) | 20 947 (17 416–24 477) | 14 118 (13 373–14 865) | 21.3 (17.5–25.1) |

| Medicare | 1100 | 15.9 (13.7–18.0) | 28 819 (24 391–33 244) | 18 696 (17 752–19 639) | 31.7 (26.6–36.8) |

| Medicaid | 1660 | 18.8 (14.9–22.6) | 30 857 (25 252–36 462) | 20 285 (19 208–21 362) | 51.2 (38.2–64.2) |

| Other government | 265 | 17.6 (3.8–31.5) | 17 457 (7 766–27 148) | 10 654 (9 768–11 539) | 4.6 (1.5–7.8) |

| Uninsured | 880 | 12.6 (10.8–14.4) | 16 573 (13 996–19 150) | 12 140 (11 663–12 618) | 14.6 (12.0–17.1) |

| By census region | |||||

| Northeast | 935 | 17.5 (14.8–20.2) | 32 213 (26 433–37 994) | 21 036 (19 833–22 238) | 30.1 (24.0–36.3) |

| Midwest | 575 | 11.6 (8.9–14.4) | 20 888 (14 879–26 898) | 12 879 (11 937–13 820) | 12.0 (8.3–15.8) |

| South | 1945 | 13.5 (10.7–16.3) | 17 121 (14 251–19 990) | 12 023 (11 501–12 555) | 33.3 (26.4–40.3) |

| West | 1465 | 18.7 (14.8–22.7) | 32 740 (26 631–38 850) | 23 302 (21 992–24 611) | 48.0 (34.0–62.0) |

| Hospitalizations with TB as any secondary diagnosis | |||||

| Major principal diagnoses, including | 5890 | 10.9 (10.1–11.7) | 25 114 (23 231–26 997) | 15 909 (15 337–16 481) | 141.9 (128.4–155.5) |

| Septicemia | 895 | 14.7 (12.6–16.8) | 31 916 (27 601–36 231) | 23 335 (21 979–24 690) | 28.6 (24.7–32.4) |

| HIV infection | 600 | 19.8 (16.1–23.5) | 34 901 (28 341–41 460) | 21 472 (20 009–22 937) | 20.9 (17.1–24.8) |

| Pneumonia | 565 | 7.9 (6.6–9.1) | 14 114 (11 806–16 421) | 11 074 (10 404–11 744) | 8.0 (6.5–9.4) |

| COPD-B | 150 | 6.3 (5.4–7.1) | 11 845 (9 732–13 957) | 8 687 (8 337–9 036) | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) |

| By primary insurer | |||||

| Private | 980 | 10.1 (8.1–12.2) | 23 073 (18 084–28 061) | 14 325 (13 527–15 122) | 22.6 (17.9–27.3) |

| Medicare | 2,060 | 9.8 (8.8–10.8) | 22 961 (20 363–25 559) | 15 187 (14 496–15 877) | 47.3 (41.5–53.1) |

| Medicaid | 1,875 | 12.6 (11.1–14.0) | 27 529 (23 884–31 173) | 17 922 (16 766–19 078) | 51.6 (44.0–59.2) |

| Other government | 195 | 10.2 (6.1–14.3) | 24 486 (9 205–39 766) | 12 507 (11 849–13 164) | 4.8 (1.7–7.8) |

| Uninsured | 780 | 11.0 (8.9–13.1) | 20 037 (16 797–23 278) | 14 527 (13 267–15 788) | 15.6 (12.8–18.4) |

| By census region | |||||

| Northeast | 1050 | 11.0 (9.3–12.7) | 22 402 (18 823–25 981) | 15 474 (14 441–16 508) | 23.5 (18.6–28.5) |

| Midwest | 800 | 9.4 (7.9–10.9) | 22 802 (18 092–27 511) | 14 073 (13 006–15 140) | 18.2 (13.9–22.6) |

| South | 2355 | 11.5 (10.1–12.8) | 21 469 (18 680–24 259) | 14 387 (13 614–15 161) | 50.6 (43.0–58.2) |

| West | 1685 | 10.8 (9.3–12.3) | 29 441 (25 203–33 680) | 18 862 (17 496–20 228) | 49.6 (40.5–58.8) |

All results are adjusted for patient characteristics (insurance status, sex, race/ethnicity, age, median household income, and urbanicity), clinical elements (discharge status, evidence of the major operating room procedure, number of chronic conditions and procedures, and lengths of stay), and hospital characteristics (ownership, size, and census region). Furthermore, ‘Hospitalizations principally for TB, All’ are adjusted for site of TB disease (pulmonary, other respiratory, central nervous system, bone and joint, intestinal, genitourinary, and not elsewhere specified, and miliary/disseminated). All adjusted costs are estimated at the groupspecific means of covariates.

Excludes 65 observations with the cost of hospitalization missing.

Excludes 190 observations with the cost of hospitalization missing and 435 observations with TB noted as both principal and any secondary diagnoses (classified as TB-PD in this study).

CI=confidence interval; TB=tuberculosis; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; COPD-B=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis; TB-PD=TB principal diagnosis.

The adjusted average cost per TB-SD hospitalization was $15909 (95%CI $15337–$16481), which varied between $14073 (95%CI $13006–$15140) in the Midwest and $18862 (95%CI $17496–$20228) in the West. Among most common principal diagnoses, hospitalizations with septicemia ($23335, 95%CI $21979–$24690) or HIV infection ($21472, 95%CI $20009–$22937) were more expensive, whereas hospitalizations with pneumonia ($11074, 95%CI $10 404–$11 744) or COPD-B ($8687, 95%CI $8337–$9036) were less expensive than the TB-SD average.

The estimated total US cost of TB-related hospitalizations in 2014 was $123.4 million (95%CI $106.3–$140.5) for TB-PD and $141.9 million (95%CI $128.4–$155.5) for TB-SD (Table 4). The total TB-PD cost was concentrated in the West ($48.0 million, 95%CI $34.0–$62.0) and Northeast ($30.1 million, 95%CI $24.0–$36.3), although these regions represented a smaller proportion of TB-PD hospitalizations (West, 38.9% of the total cost and 29.7% of hospitalizations; Northeast, 24.3% and 19.1%, respectively; Tables 2 and 4). By contrast, the South represented the largest proportion of TB-PD hospitalizations (39.5%, Table 2); however, it had only 27.0% of TB-PD costs ($33.3 million, 95%CI $26.4–$40.3; Table 4). Among TB-SD hospitalizations, the four most common principal diagnoses (septicemia, HIV infection, pneumonia, and COPD-B) accounted for 37.5% of hospitalizations, and for a comparable 41.8% of the total cost (Table 4).

Most of the total TB-related hospitalization costs were paid by Medicaid ($51.2 million, 95%CI $38.2–$64.2, or 41.5% of total TB-PD hospitalization cost; $51.6 million, 95%CI $44.0–$59.2, or 36.4% of total TB-SD hospitalization cost), followed by Medicare ($31.7 million, 95%CI $26.6–$36.8, or 25.7%, and $47.3 million, 95%CI $41.5–$53.1, or 33.3%, respectively). Private insurance paid less than 20% of total TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalization costs ($21.3 million, 95%CI $17.5–$25.1, or 17.2% and $22.6 million, 95%CI $17.9–$27.3, or 15.9%, respectively). Approximately 11% of total hospitalization costs was for uninsured patients ($14.6 million, 95%CI $12.0–$17.1, or 11.8% and $15.6 million, 95%CI $12.8–$18.4, or 11.0%, respectively). Among all insurance types, Medicaid accounted for a greater share of total costs than Medicaid’s share of hospitalizations (TB-PD, 41.5% of the total cost and 33.7% of hospitalizations; TB-SD, 36.4% of the total cost and 31.8% of hospitalizations). For other insurance types, the distribution of the total costs reflected the distribution of hospitalizations.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides the most recent national estimates of the number and the cost of hospitalizations among US patients with active TB disease. In 2014, we estimated 4985 TB-PD and 6080 TB-SD hospitalizations nationwide. Among TB-PD, with an adjusted average cost of $16695 per hospitalization, costs were significantly higher for miliary/disseminated ($22 498) and CNS TB ($28 338) than PTB ($14819). Among TB-SD, hospitalizations with septicemia ($23335) and HIV infection ($21472) were more expensive than the TB-SD adjusted average ($15909). The total US cost of TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalizations exceeded $120 million and $140 million, respectively, with the majority of the costs covered by Medicaid/Medicare (TB-PD, 67.2%; TB-SD, 69.7%).

During the last decade, several papers have estimated the number of US TB-related hospitalizations. Mirsaeidi et al. focused on TB-PD hospitalizations for PTB (period from 2001 to 2012) and estimated an average of 5770 hospitalizations per year,10 compared with our 2014 estimate of 3725 PTB-PD hospitalizations. This decrease likely reflects a recent sharp decline in TB cases, from 15 945 in 2001 to 9406 in 2014.2

Holmquist et al. accounted for pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB diseases and analyzed TB-PD and TB-SD hospitalizations.7 Contrary to our results (11065 hospitalizations with any TB ICD-9 code in 2014: 45% TB-PD and 55% exclusively TB-SD hospitalizations), in 2006 Holmquist et al. identified nearly 58500 TB-related hospitalizations, of which 15% were TB-PD and 85% were TB-SD. This discrepancy was due to differences in defining TB, as Holmquist et al. included non-TB disease (i.e., primary tuberculous infection, personal history of TB, and late effects of TB without evidence of active disease), as well as active TB (described in our study). When we applied methodology from Holmquist et al. to 2014 NIS data (results not shown), we identified 54760 hospitalizations with any TB ICD-9 codes, including 5065 (9%) TB-PD and 49695 (91%) TB-SD hospitalizations, and estimated that non-TB disease accounted for 1.6% (80 episodes) of TB-PD and 87.4% (43433 episodes) of TB-SD hospitalizations.

Owusu-Edusei et al. estimated 2010–2014 costs of TB-PD hospitalizations among commercially insured US patients.9 When we created a data subset for only privately insured patients, our estimates of hospitalization costs were half as large as in Owusu-Edusei et al. (our study, $14118 per TB-PD hospitalization; Owusu-Edusei et al., $33085 in 2014 US dollars). This was because we 1) calculated costs rather than payments, 2) did not include physician costs, and 3) estimated per hospitalization rather than per patient cost, including multiple hospitalizations. The NIS allowed us neither to compare costs with payments nor to identify unique enrollees to estimate per person cost of in-patient care. However, the majority of hospitalizations in Owusu-Edusei et al. represented unique enrollees (892 TB hospitalizations, 825 enrollees), implying a slight difference between an average cost per person ($33085)9 and per hospitalization (approximately $30000). To include physician costs, we applied insurer-specific professional expenditure ratios for CCS code 1 (TB) and codes 2, 5, 122, and 127 (septicemia, HIV infection, pneumonia, and COPD-B, respectively).25 Compared to hospitalization costs alone, estimated hospital and professional TB-PD costs would be 20% higher for private insurers and Medicare, and 9% higher for Medicaid, whereas TB-SD costs would be respectively 13–15% and 6–8% higher (results not shown). The residual difference in estimated costs between our study and that of Owusu-Edusei et al. was likely due to differences between costs and payments.

Our study is unique in estimating the US cost of hospitalizations with a diagnosis for active TB, as the three previous studies reported on 1) hospital charges,10 which were nearly four times16 higher than the actual costs of hospitalization; 2) privately insured patients9 who, according to our results, represented only 21% of TB-PD and 17% of TB-SD hospitalizations; or 3) hospitalizations for both active TB and non-TB disease,7 which, as our study demonstrates, were dominated by non-TB disease. Our estimates of health care costs for TB-related in-patient care are therefore not directly comparable with findings from those studies updated to 2014 dollars.

There are several limitations to our study. As NIS reported hospitalization discharges rather than individual patients, we could not differentiate between patients with single and multiple hospitalizations or estimate the per person cost of in-patient care. We have also underestimated the cost of in-patient care, as the NIS reported only hospital costs and excluded physician costs. For TB-SD hospitalizations, we could not estimate the cost attributable to TB alone, as some costs were attributable to the principal or secondary non-TB diagnoses. Furthermore, NIS lacked measures of disease severity, drug resistance, and treatment practices, limiting our ability to analyze the contribution of these factors to the cost of TB-related hospitalizations. This analysis also did not include the cost of TB-related ambulatory care. Finally, it is possible that some TB diagnoses were not confirmed by a positive M. tuberculosis culture by the time of hospital discharge, and thus some hospitalizations might not have been for verified TB.

CONCLUSION

In 2014, the cost of 11065 hospitalization episodes with a principal or any secondary diagnosis of active TB exceeded $260 million. Hospitalizations that involve TB result in substantial costs within the US health care system and reinforce the need to focus on TB prevention.13

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance’s Partnership and Evaluation Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, GA, USA) for providing financial support and technical assistance with Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project data.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003; 52(RR-11): 1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/reports/2014/default.htm. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karumbi J, Garner P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (5): CD003343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown RE, Miller B, Taylor WR, et al. Health-care expenditures for tuberculosis in the United States. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 1595–1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor Z, Marks SM, Rios Burrows NM, et al. Causes and costs of hospitalization of tuberculosis patients in the United States. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000; 4: 931–939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks SM, Flood J, Seaworth B, et al. Treatment practices, outcomes, and costs of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, United States, 2005–2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20: 812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmquist L, Russo CA, Elixhauser A. Tuberculosis stays in US hospitals, 2006. Statistical brief #60. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD, USA: HCUP, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks S, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Salcedo K, et al. Characteristics and costs of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in-patient care in the United States, 2005–2007. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016; 20: 435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owusu-Edusei K, Marks SM, Miramontes R, et al. Tuberculosis hospitalization expenditures per patient from private health insurance claims data, 2010–2014. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017; 21: 398–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirsaeidi M, Allen MB, Ebrahimi G, et al. Hospital costs in the US for pulmonary mycobacterial diseases. Int J Mycobacteriol 2015; 4: 217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LoBue PA, Mermin JH. Latent tuberculosis infection: the final frontier of tuberculosis elimination in the USA. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: e327–e333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2016. Atlanta, GA, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/reports/2016/default.htm. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016; 316: 962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS), 1980–2015. Rockville, MD, USA: AHRQ, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: NIS description of data elements, 1980–2014. Rockville, MD, USA: AHRQ, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Cost-to-charge ratio (CCR) Files, 2001–2014. Rockville, MD, USA: AHRQ, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niles NJ. Basics of the US health care system. Burlington, MA, USA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In-patient rehabilitation facilities. Baltimore, MD, USA: CMS, 2012. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/InpatientRehab.html. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Hospital Association. Long-term care hospitals. Washington DC, USA: AHA, 2006–2017. http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/postacute/ltach/index.shtml. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office for Human Research Protections, US Department of Health and Human Services. Protection of human subjects. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45, Part 46. Rockville, MD, USA: OHRP, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Atlanta, GA, USA: CDC, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. Accessed September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Clinical Classifications Software: diagnoses (CCS) for ICD-9-CM, 1980–2015. Rockville, MD, USA: AHRQ, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/AppendixASingleDX.txt. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baltagi BH. A companion to theoretical econometrics. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Vol 571. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson C, Xu L, Florence C, et al. Professional fee ratios for US hospital discharge data. Med Care 2015; 53: 840–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]