Abstract

Aim:

To assess providers’ knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and experiences related to pharmacogenomic (PGx) testing in pediatric patients.

Materials & methods:

An electronic survey was sent to multidisciplinary healthcare providers at a pediatric hospital.

Results:

Of 261 respondents, 71.3% were slightly or not at all familiar with PGx, despite 50.2% reporting prior PGx education or training. Most providers, apart from psychiatry, perceived PGx to be at least moderately useful to inform clinical decisions. However, only 26.4% of providers had recent PGx testing experience. Unfamiliarity with PGx and uncertainty about the clinical value of testing were common perceived challenges.

Conclusion:

Low PGx familiarity among pediatric providers suggests additional education and electronic resources are needed for PGx examples in which data support testing in children.

Keywords: : children, pediatric, perspective, pharmacogenetic, pharmacogenomic, provider, testing

Precision medicine holds the promise of improving patient outcomes by taking into account a patient’s genes, environment, and lifestyle [1]. Pharmacogenomics (PGx) is often the initial focus of precision medicine implementation efforts, as it studies the impact of genetic variation on drug response, with the goal of optimizing therapeutic benefit and minimizing adverse effects [2]. Clinical implementation of PGx has primarily been conducted in adult populations [3]. However, there is interest in extending its application to pediatric settings [4–6]. Along these lines, some institutions have implemented PGx testing for pediatric patients in areas such as psychiatry, pain management, infectious disease, oncology, among others [7–17].

Several unique factors must be considered when evaluating the potential utility of PGx testing in children [16,18,19]. Perhaps the most notable challenge is the impact of pediatric ontogeny, the age-dependent maturation and development of the expression of genes related to drug disposition [20,21]. For example, CYP2D6 is fully expressed by two weeks of age, while CYP2C19 is not fully expressed until 10 years of age [22–24]. Thus, the effects of genetic variants on drug metabolism may not become apparent until the gene product is mature. Another challenge is the lack of robust PGx studies in pediatric patients. Approximately 80% of PGx clinical trials are conducted in adults compared with children, and US FDA drug labeling primarily includes PGx data obtained from adult studies [16,19,25]. In addition, usage of actionable PGx medications differs between age groups [26]. For example, clopidogrel, an antiplatelet agent affected by PGx, is not widely prescribed in pediatric settings [5]. However, some PGx medications that are used more commonly in children (e.g., atomoxetine) have pediatric-specific recommendations published in Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines [27]. Ethical issues, such as confusion about genetic versus PGx testing and consent/assent issues, also pose barriers to PGx testing in children [19].

In adult populations, studies have shown that physicians generally support PGx testing, but often report lack of education and training, lack of confidence in applying the results, and concerns about cost and insurance coverage [28–33]. Similar knowledge and attitudes were recently reported among pediatricians in the US and Japan [4]. However, additional research regarding PGx perspectives is needed in multidisciplinary groups of healthcare providers caring for children. To this end, the primary aim of our study was to assess healthcare providers’ knowledge of, attitudes toward, perceptions of, and experiences with PGx testing in pediatric patients, across a wide range of specialties. Second, the study aimed to assess the extent of pharmacist involvement with PGx testing in the pediatric setting.

Materials & methods

Study population & setting

In this cross-sectional study, an electronic survey was sent to practicing physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists (hereafter referred to collectively as ‘providers’) at Children’s Hospital Colorado (CHCO). These providers were selected for inclusion as they had clinical responsibilities related to ordering, interpreting, and/or applying information from PGx testing. A postcard consent was used and participation in the survey indicated informed consent. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Multigene panel-based PGx testing via an external commercial laboratory had been made available at the institution in July 2018. At the time of the survey, there were no formal institution-wide PGx implementation initiatives, research projects or electronic health record clinical decision support (CDS) tools in place. There was also no structured pharmacy integration with respect to PGx, and pharmacist roles varied based on the patient population and clinical practice setting.

Survey development

A 26-item survey was developed to assess providers’ knowledge (domain 1), attitudes (domain 2), perceptions (domain 3), and experiences (domain 4) related to PGx testing (Appendix A). A definition of PGx and pediatrics was presented to participants at the beginning of the survey. To avoid asking irrelevant questions, survey items were adapted to user responses. For example, if a provider never used PGx testing, they would not receive subsequent questions asking about PGx testing experiences. All providers were asked 16 common questions, eight of which were demographic questions. Providers with PGx testing experience were asked ten additional questions, three of which were specific to pharmacists.

Five members of the study team created the survey (CL Aquilante, AB Blackmer, YM Lee, I Liko and DL Stutzman) based on available literature and clinical expertise [34,35]. The survey was pretested by five providers to identify and reduce measurement error, response burden and question ambiguity. The survey was then pilot tested by 18 providers prior to widespread distribution. The final survey was electronically distributed to providers between May and June 2019. Two reminder emails were sent to survey non-responders. Qualtrics (UT, USA) was used to disseminate the survey and collect response data.

Data analysis

Survey responses were tabulated, stored, and anonymized within Qualtrics. A survey was deemed complete if the participant answered at least 85% of the questions presented to them (i.e., at least 14 of the common questions for all providers, at least 20 questions for non-pharmacists with PGx testing experience, and at least 22 questions for pharmacists with PGx testing experience). Questions were evaluated for missing responses, response variability, and ceiling or floor effects. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25 (NY, USA). For statistical analysis, select variables were collapsed into categories: physicians versus nurse practitioners/physician assistants/other versus pharmacists; no PGx education or training versus any PGx education or training; PGx use versus no PGx use; not at all useful versus slightly useful/moderately useful versus very/extremely useful; not at all familiar/slightly familiar versus moderately familiar versus very/extremely familiar.

Spearman’s correlation tests were used to evaluate relationships between PGx education or training and PGx use, and PGx education or training and familiarity with PGx. Chi-square tests were performed to assess relationships between years in practice since graduation from health professional school and provider type; and PGx education or training and provider type. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was measured for questions pertaining to providers’ confidence in ordering PGx testing; interpreting the results; applying the results to inform patient care decisions; and discussing the results with patients and caregivers. An overall provider confidence score (range 0 to 16; 0 = not at all confident, 16 = very confident) was calculated by adding the scores from each of the four confidence questions. Using a Kruskal–Wallis test, overall confidence scores were compared between the percentage of cases providers reported making medication changes based on PGx results (i.e., 0 vs 1–24 vs 25–75%).

Results were further descriptively analyzed among certain specialties, with a focus on general pediatrics, hematology/oncology, anesthesiology/pain and surgery, and psychiatry. Statistical comparisons were not made between these groups due to the small sample sizes within each specialty.

Results

Participant demographics

Of the 1358 providers invited to participate in the survey, 261 (19.2%) responded (characteristics shown in Table 1). The majority of participants were women (65.1%), Caucasians (87.0%), and physicians (66.3%). Providers spanned 37 different specialty areas, with general pediatrics being the largest specialty (15.0%), and 53.5% of providers had direct patient care responsibilities for greater than 30 h per week. Physicians (54.3%) were more likely to have been practicing for greater than 10 years when compared with nurse practitioners/physician assistants/other (34.8%) and pharmacists (26.2%); p = 0.001.

Table 1. . Participants’ characteristics.

| Characteristic | Overall cohort, n (%) | PGx test users, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of healthcare provider | n = 261 | n = 69 |

| Physician | 173 (66.3%) | 52 (75.4%) |

| Pharmacist | 42 (16.1%) | 8 (11.6%) |

| Nurse practitioner | 31 (11.9%) | 8 (11.6%) |

| Physician assistant | 13 (5.0%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Other provider† | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Sex | n = 261 | n = 69 |

| Female | 170 (65.1%) | 45 (65.2%) |

| Male | 87 (33.3%) | 22 (31.9%) |

| Prefer not to respond | 4 (1.5%) | 2 (2.9%) |

| Race‡ | n = 261 | n = 69 |

| White or Caucasian | 227 (87.0%) | 54 (78.3%) |

| Asian | 17 (6.5%) | 8 (11.6%) |

| African–American | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Multiple races | 7 (2.7%) | 4 (5.8%) |

| Other | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Prefer not to respond | 8 (3.1%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Years in practice post-graduation | n = 261 | n = 69 |

| 0–10 years | 140 (53.6%) | 36 (52.2%) |

| 11–20 years | 75 (28.7%) | 16 (23.2%) |

| 21–30 years | 28 (10.7%) | 13 (18.8%) |

| >30 years | 18 (6.9%) | 4 (5.8%) |

| Hours of direct patient care per week | n = 258 | n = 68 |

| 0–10 h | 58 (22.5%) | 19 (27.9%) |

| 11–20 h | 26 (10.1%) | 9 (13.2%) |

| 21–30 h | 36 (14.0%) | 8 (11.8%) |

| >30 h | 138 (53.5%) | 32 (47.1%) |

| Specialty‡ | n = 260 | n = 69 |

| General pediatrics | 39 (15.0%) | 6 (8.7%) |

| Emergency medicine | 26 (10.0%) | 2 (2.9%) |

| Hematology/oncology | 21 (8.1%) | 11 (15.9%) |

| Critical care | 18 (6.9%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Psychiatry | 15 (5.8%) | 15 (21.7%) |

| Neurology | 15 (5.8%) | 2 (2.9%) |

| Anesthesiology/pain and surgery | 18 (6.9%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Hospitalist | 13 (5.0%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Pulmonology | 10 (3.9%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Infectious disease | 9 (3.5%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Neonatology | 9 (3.5%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Cardiology | 8 (3.1%) | 2 (2.9%) |

| Gastroenterology | 7 (2.7%) | 5 (7.3%) |

| Endocrinology | 6 (2.3%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Orthopedics | 5 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Transplant | 5 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Rheumatology | 4 (1.5%) | 4 (5.8%) |

| Developmental pediatrics | 6 (2.3%) | 4 (5.8%) |

| Other§ | 38 (14.6%) | 3 (4.4%) |

Other provider: Unspecified advanced practice provider and optometrist.

Percentages may not add up to 100% as participants could choose more than one answer.

Other specialties: adolescent medicine; allergy/immunology; child abuse; dentistry; dermatology; genetics; informatics; investigational medications; maternal fetal medicine; nephrology; nuclear pharmacy; nutrition; optometry; otolaryngology; pathology; pharmacy operations; rehabilitation; toxicology; urology.

PGx: Pharmacogenomic.

Results for all providers

PGx knowledge & education

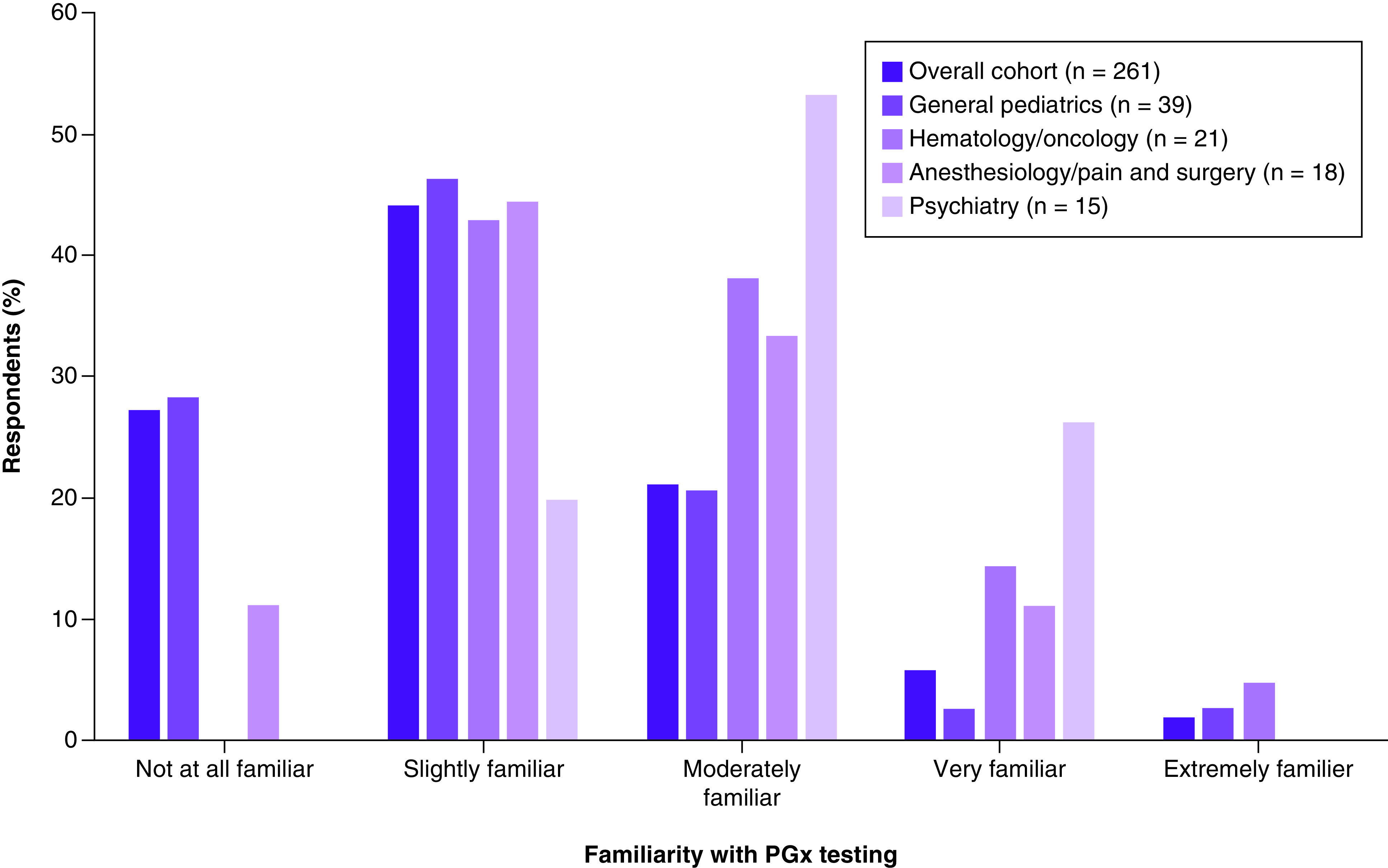

In the overall cohort, 71.3% of participants reported being either slightly familiar or not at all familiar with PGx testing in the pediatric population (Figure 1). Among the selected specialties, psychiatry had the highest proportion of providers being moderately, very, or extremely familiar with PGx testing, followed by hematology/oncology, anesthesiology/pain and surgery, and general pediatrics (80%, 57.2%, 44.4% and 25.6%, respectively).

Figure 1. . Providers’ familiarity with pharmacogenomic testing in the pediatric population.

Just over half (50.2%) of the providers in the overall cohort received PGx education or training. Of those with PGx education or training, 51.9% reported receiving it during health professional school, 31.3% through continuing medical education programs, 22.1% in fellowship training, 19.1% during residency training, 7.6% in certificate programs, and 4.6% through seminars by genetics companies, conferences, or noncontinuing medical education courses. Among selected specialties, the reported frequency of PGx education or training was highest in psychiatry (80%), followed by hematology/oncology (66.7%), anesthesiology/pain and surgery (50%), and general pediatrics (48.7%).

Pharmacists were more likely to have received PGx education or training than nurse practitioners/physician assistants/other or physicians (71.4% vs 54.4% vs 43.9%, respectively; p = 0.005). Providers who received PGx education or training were more likely to use PGx in clinical practice (correlation coefficient: 0.23; p = 0.0002) and were more familiar with PGx (correlation coefficient: 0.32; p < 0.0001) compared with providers who had not received PGx education or training.

Attitudes & perceived challenges of adopting PGx

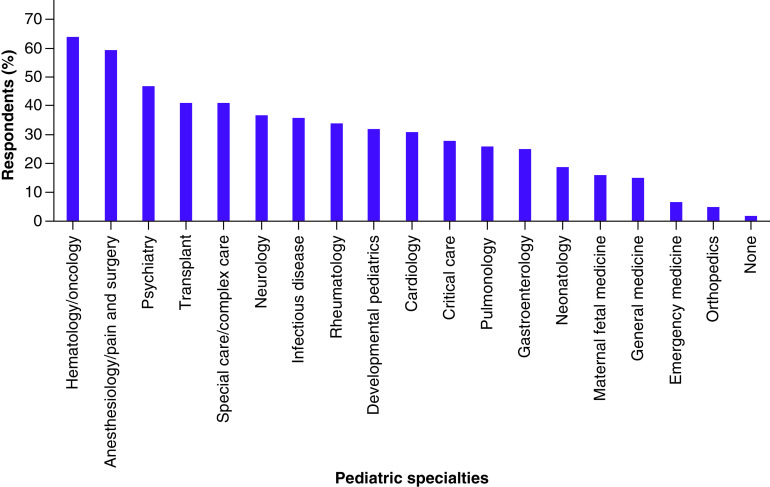

In the overall cohort, 70.7% of participants perceived PGx testing to inform clinical decisions in pediatric patients to be either moderately, very, or extremely useful (Table 2). Among selected specialties, this number was highest in anesthesiology/pain and surgery (100%) and hematology/oncology (90.5%), and lowest in psychiatry (26.7%). The top three pediatric specialties where providers perceived PGx testing to have the most clinical use were hematology/oncology (63.8%), anesthesiology/pain and surgery (59.5%), and psychiatry (46.7%) (Figure 2).

Table 2. . Perceived clinical usefulness of pharmacogenomic testing, among the overall cohort and by selected specialties.

| Degree of clinical usefulness | Overall cohort (n = 256), n (%) | General pediatrics (n = 39), n (%) | Hematology/oncology (n = 21), n (%) | Anesthesiology/pain and surgery (n = 18), n (%) | Psychiatry (n = 15), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all useful | 4 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Slightly useful | 71 (27.7%) | 17 (43.6%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (73.3%) |

| Moderately useful | 105 (41.0%) | 10 (25.6%) | 10 (47.6%) | 10 (55.6%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Very useful | 64 (25.0%) | 9 (23.1%) | 6 (28.6%) | 6 (33.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Extremely useful | 12 (4.7%) | 3 (7.7%) | 3 (14.3%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Figure 2. . Providers’ (n = 257) perception of pediatric specialties where pharmacogenomics has the most clinical use.

The most common perceived challenges of PGx testing in the overall cohort included unfamiliarity with PGx (78.2%), cost/insurance coverage (62.8%), applying PGx test results to clinical practice (62.5%), and uncertainty about the clinical value of PGx testing (60.2%) (Table 3). Unfamiliarity with PGx and/or cost/insurance coverage were the top perceived challenges in each of the selected specialties, except for psychiatry, which included the challenge of uncertainty about the clinical value of PGx testing (73.3%). Of note, ethical, legal and privacy concerns was reported by 40% of those in the psychiatry specialty but was less common in other groups.

Table 3. . Perceived challenges of using pharmacogenomic testing, among the overall cohort and by selected specialties.

| Perceived PGx challenges | Overall cohort (n = 261), n (%)† | General pediatrics (n = 39), n (%)† | Hematology/oncology (n = 21), n (%)† | Anesthesiology/pain and surgery (n = 18), n (%)† | Psychiatry (n = 15), n (%)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfamiliarity with PGx | 204 (78.2%) | 30 (76.9%) | 13 (61.9%) | 13 (72.2%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Cost/insurance coverage | 164 (62.8%) | 28 (71.8%) | 13 (61.9%) | 14 (77.8%) | 11 (73.3%) |

| Applying PGx test results to clinical practice | 163 (62.5%) | 29 (74.4%) | 12 (57.1%) | 10 (55.6%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| Uncertainty about the clinical value of PGx testing | 157 (60.2%) | 29 (74.4%) | 8 (38.1%) | 13 (72.2%) | 11 (73.3%) |

| Interpreting PGx test results | 130 (49.8%) | 25 (64.1%) | 5 (23.8%) | 7 (38.9%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| Difficulty in ordering PGx testing | 96 (36.8%) | 20 (51.3%) | 4 (19.1%) | 7 (38.9%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Discussing PGx test results with patients and caregivers | 58 (22.2%) | 14 (35.9%) | 1 (4.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | 5 (33.3%) |

| Ethical, legal and privacy concerns | 42 (16.1%) | 7 (18.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (16.7%) | 6 (40.0%) |

| Patient/caregivers declined the test | 18 (6.9%) | 3 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| No challenges encountered | 3 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other‡ | 6 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (13.3%) |

Percentages may not add up to 100% as participants could choose more than one answer.

Other includes: pressure from family members to change medication based on PGx test results; slow turn-around time with PGx testing; and no consistent institutional practice for handling PGx test results.

PGx: Pharmacogenomic.

Perspectives about PGx resources

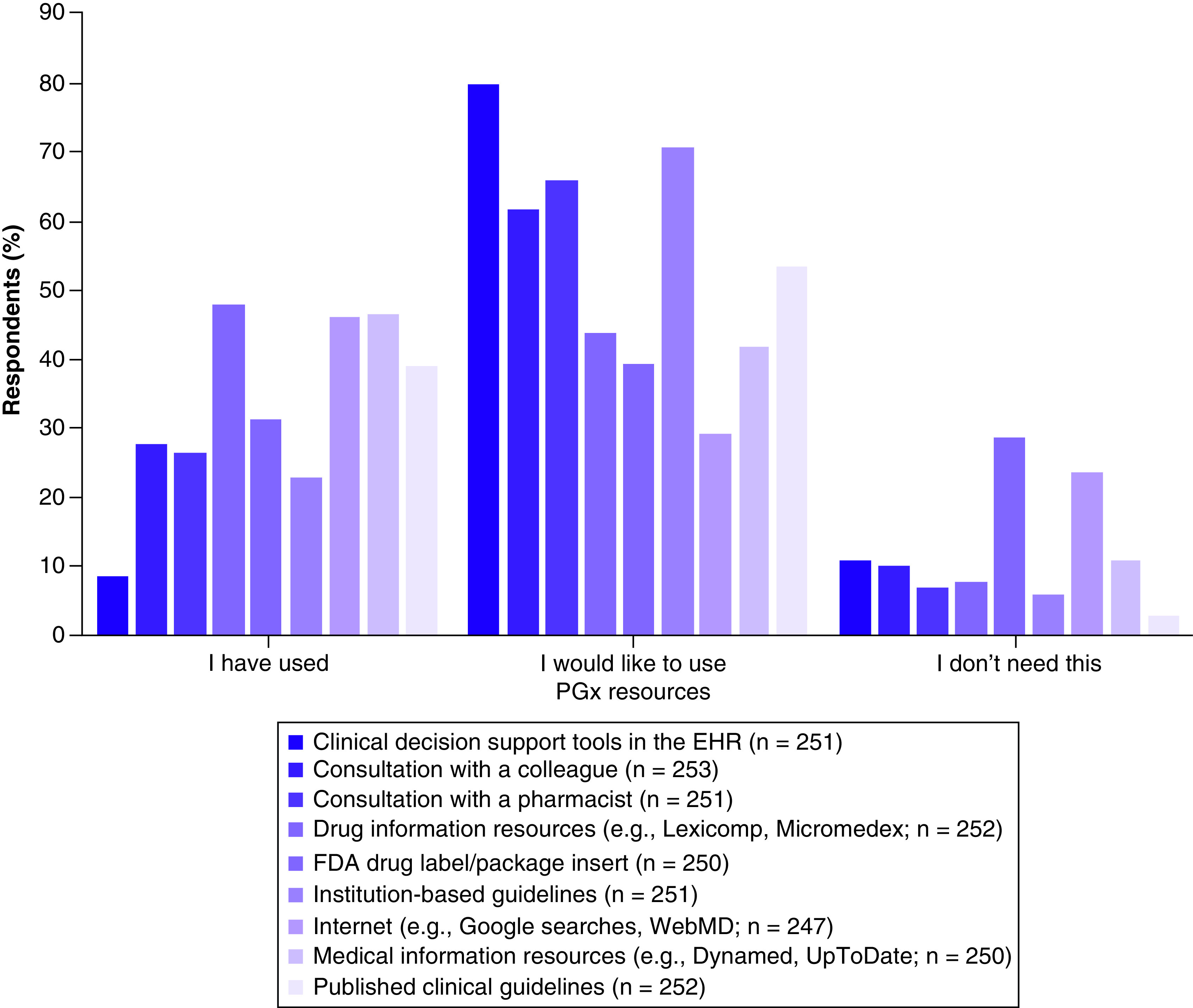

Resources that were reported to be used by greater than 40% of providers to obtain PGx information included: drug information databases (e.g., Lexicomp, Micromedex; 48%), medical information databases (e.g., Dynamed, UpToDate; 46.8%), and internet searches (e.g., Google, WebMD; 46.6%) (Figure 3). Resources that greater than 60% of providers reported wanting to use included: CDS tools in the electronic health record (80.1%), institution-based guidelines (70.9%), consultation with a pharmacist (66.1%), and consultation with a colleague (62.1%).

Figure 3. . Pharmacogenomic resources providers (n = 253) have used, would like to use, and do not perceive they need.

Results for providers with PGx testing experience in the pediatric population

Experience with PGx testing in the pediatric population & types of tests used

Of the providers who participated in the survey, 69 (26.4%) had used PGx testing in the past 12 months (participant characteristics, Table 1). The majority were physicians (75.4%), and the top three specialties were psychiatry (21.7%), hematology/oncology (15.9%), and general pediatrics (8.7%). More than 50% of providers had used PGx testing for 1–5 years (53.6%). The rest of providers had used PGx testing for less than 1 year (21.7%), 6–10 years (10.1%) or greater than 10 years (14.5%). Of 68 providers who responded about type of PGx testing, 41.2%, 32.4% and 26.5% reported using individual gene testing, panel-based (multigene) testing, or both, respectively. The most used individual gene PGx tests included: TPMT (52.2%), MTHFR (43.5%), CYP450 (28.3%) and CFTR (19.6%). The most common multigene panel-based PGx tests were: OneOme® (47.5%), Genesight® (45%) and Genomind® (2.5%).

Confidence in using PGx tests

Providers who had used PGx testing in the past 12 months (n = 69) reported being either confident or very confident with respect to applying PGx test results to inform patient care decisions (55.1%), interpreting the results (52.2%), discussing the results with patients and their caregivers (50.7%), and ordering PGx tests (46.4%). The internal consistency of these confidence questions was high, with Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.94. The median overall PGx confidence score was 10 (range: 0–16).

Reported clinical outcomes with PGx testing in the pediatric population

The top two areas in which providers with PGx testing experience reported using PGx test results were psychiatry (antidepressants/anxiolytics [50.7%], antipsychotics [37.7%], attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications [34.8%]) and hematology/oncology (23.2%) (Table 4). Providers with PGx testing experience reported making medication changes based on PGx test results for: 1–24% of cases (62.3%), 0% of cases (21.7%), 25–49% of cases (10.1%), and 50–75% of cases (5.8%). Providers who made medication changes 1–24% or 25–75% of the time had significantly higher overall confidence scores (medians = 12 and 9, respectively) compared with those who did not make medication changes (median = 2; p = 0.0002). In psychiatry, the selected specialty with the greatest number of providers with PGx testing experience (n = 15), 86.7% of providers made medication changes in less than 25% of cases.

Table 4. . Medications for which providers (n = 69) reported using pharmacogenomics results.

| Type of medication | n (%)† |

|---|---|

| Antidepressants/anxiolytics | 35 (50.7%) |

| Antipsychotics | 26 (37.7%) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 24 (34.8%) |

| Hematology/oncology | 16 (23.2%) |

| Neurology | 10 (14.5%) |

| Pulmonary | 9 (13.0%) |

| Rheumatology | 9 (13.0%) |

| Analgesics | 8 (11.6%) |

| Gastroenterology | 7 (10.1%) |

| Anti-infectives | 6 (8.7%) |

| Antiplatelet/anticoagulants | 4 (5.8%) |

| Transplant | 2 (2.9%) |

| Other | 1 (1.5%) |

Percentages may not add up to 100% as participants could choose more than one answer.

Sixty-six providers reported the following clinical outcomes when using PGx testing: avoided adverse outcomes (57.6%), improved patient/family satisfaction (37.9%), improved drug response (28.8%), continued current therapy with no difference in clinical outcome (24.2%), changed drug therapy with no difference in clinical outcomes (22.7%) and adverse outcomes despite using PGx results (16.7%). In psychiatry, the most reported clinical outcomes were improved patient/family satisfaction (60.0%) and continued current drug therapy with no difference in clinical outcomes (46.7%).

Results for pharmacists

Out of 42 pharmacists who completed the survey, eight (19.0%) had PGx testing experience and practiced in oncology (37.5%), general pediatrics (37.5%), critical care (12.5%) and pharmacy operations (12.5%). They reported spending 0–5 h per week on PGx-related activities, with the most time spent on interpreting PGx test results (52.0%), educating patients or caregivers (29.5%) and educating other healthcare providers (18.5%). Most pharmacists with PGx testing experience (75%) reported ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ to: recommending PGx testing; being the drivers of medication changes based on PGx test results; and disagreeing with a provider on how to use PGx test results to guide therapy.

Discussion

We evaluated a multidisciplinary group of healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and experiences related to PGx testing in pediatric patients. Our findings indicate that overall familiarity with PGx was low, but most providers, apart from psychiatry specialists, perceived PGx to be at least moderately useful to inform clinical decision-making in children. Experience with PGx testing was modest, particularly among pharmacists, and testing was used most often in relation to psychiatry medications. However, of those who used PGx tests, the results prompted medication changes in less than a quarter of cases. Findings from this study indicate that unfamiliarity with PGx testing, cost/insurance coverage, and uncertainty about the clinical value of PGx testing are common perceived challenges among pediatric healthcare providers, and thus potential targets for future educational endeavors.

Our finding that providers had low familiarity with PGx testing in children is consistent with results from a study of pediatricians which showed that less than 10% of respondents were very familiar with PGx, yet many perceived it to be a valuable tool to improve drug efficacy and safety [4]. Similar findings have also been reported in various non-pediatric populations [28–30]. At the same time, PGx education has been increasing in health profession graduate curricula and other settings [36–38]. In our study, more than 50% of providers reported some prior PGx education or training; however, the most common perceived challenge was unfamiliarity with PGx. This disconnect between education and familiarity is likely due to factors such as years in practice since graduation, type and extent of PGx education or training, and/or lack of routine application of PGx testing in the pediatric clinical setting. We also observed differences among selected specialties – psychiatry was most likely, and general pediatrics was least likely, to report prior PGx education and familiarity with PGx. Taken together, these data suggest that future efforts should delve deeper into the type and amount of PGx education or training received among pediatric providers, with an emphasis on generalists, application-oriented content, and evidence-based clinical examples.

Attitudes toward PGx testing were generally positive, with approximately 70% of the cohort perceiving it to have clinical utility in children, particularly in the areas of hematology/oncology, anesthesiology/pain and surgery, and psychiatry. However, attitudes varied when analyzed in selected specialties – perceived clinical usefulness was highest among anesthesiology/pain/surgery and hematology/oncology providers and lowest among psychiatry providers. With respect to anesthesiology/pain and surgery, there are well-established pharmacogenetic associations for codeine and CYP2D6 and FDA-issued contraindications to the use of codeine and tramadol in children younger than 12 years of age (regardless of genotype) [39,40]. Along the same lines, pediatric hematology/oncology has several examples of clinical evidence supporting the use of genotype-guided therapy, for example, TPMT/NUDT15 and thiopurines for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia [9,41,42]. In contrast, we found that 73% of psychiatry specialists perceived PGx testing to be only slightly useful to inform clinical decisions. This finding is likely driven by uncertainty about the clinical value of testing in children. To this end, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recently issued a policy statement recommending that “clinicians avoid using pharmacogenetic testing to select psychotropic medications in children and adolescents” in part due to limitations of current studies [43]. However, a recent counterpoint article recommended considering the use of PGx testing for genes with high levels of evidence, in conjunction with clinical characteristics, in child and adolescent psychiatry [44]. Together, these data highlight the need to evaluate different specialties when assessing attitudes toward PGx testing in the pediatric population.

In terms of testing experience, about one-quarter of our population reported using PGx testing in the past year. These data are consistent with other studies which reported PGx test utilization rates of 13–20% in US physicians in primary care and non-oncology specialties, and approximately 20% in pediatricians in the US and Japan [4,28]. Despite uncertainty about the clinical value of testing, psychiatry providers were the highest percentage of PGx test users in our cohort, although most reported making medication changes in less than 25% of cases. Patient/family satisfaction was the top reported clinical outcome among this group, which we speculate was a potential driver of testing. In the overall PGx test user cohort, about half of respondents reported being confident with the practical applications of testing (e.g., interpreting and applying results, ordering tests). In therapeutic areas where pediatric PGx evidence is strong, provider confidence can likely be increased with additional resources, such as the ones ranked highly in our survey. For example, the use of CDS tools that incorporate test results, PGx evidence, and CPIC guidelines has been a successful approach in various clinical settings [7,45–47]. Institution-based PGx guidelines may also be useful, as they incorporate stakeholders’ views, workflows, and preferences. Multi-disciplinary PGx teams and consult services are another means to increase provider confidence and have been successfully established at other pediatric institutions [9,11,48]. Consultation with a pharmacist was ranked highly in our cohort, which is likely due to pharmacists being active members of the healthcare team at CHCO. Of all the provider types, pharmacists were most likely to report prior PGx education or training, which is consistent with current Doctor of Pharmacy curricula and a recent position statement on the role of pediatric pharmacists in clinical PGx [48]. While these tactics can foster confidence locally, broad strategies to advance evidence-based PGx testing in the pediatric population include greater education about CPIC guidelines and data supporting genotype-directed therapy in children, dissemination of PGx information by professional societies, and shared electronic resources.

Our study has a few limitations which merit discussion. First, there is the possibility of selection and response bias; individuals who are interested in or have experience with PGx testing may have been more likely to respond to the survey. However, we minimized this potential confounder by sending the survey to all CHCO providers rather than selected specialties. There is also a potential for response bias with respect to the use of specific multigene panels, as examples were provided in the survey questions. Second, we conducted the study at a single children’s hospital and had a small number of respondents who reported using PGx testing, which may limit the generalizability of our results. Third, recall bias is possible as providers’ answers may not be reflective of actual PGx test utilization, length of time PGx testing was used in clinical practice, and usage of specific tests. Fourth, providers did not have to answer all of the survey questions, which could lead to unequal responses between questions and potentially influence study conclusions. Lastly, our survey questions did not address providers who may have used PGx test results to complement, rather than solely inform, clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

In summary, healthcare providers caring for pediatric patients had low familiarity with PGx testing, but generally perceived it be clinically useful. However, attitudes toward testing varied among selected specialties. The rate of PGx test use was modest and confidence in application was moderate in this cohort. Together, these findings point to the need for additional education and electronic resources for PGx examples in which data support testing in children.

Summary points.

Of 1358 providers surveyed, 19.2% responded (66.3% physicians, 16.1% pharmacists, 11.9% nurse practitioners and 5.0% physician assistants) and spanned various specialties.

The majority (71.3%) of the cohort was either slightly or not all familiar with pharmacogenomics (PGx) testing, despite over half of providers reporting prior PGx education or training.

The majority (70.7%) of participants perceived PGx testing to inform clinical decisions in pediatric patients to be either moderately, very, or extremely useful. However, this attitude varied among selected specialties, being highest in anesthesiology/pain and surgery (100%) and lowest in psychiatry (26.7%).

The most common perceived challenges of PGx testing in the pediatric population included unfamiliarity with PGx (78.2%), cost/insurance coverage (62.8%), applying PGx test results to clinical practice (62.5%) and uncertainty about the clinical value of PGx testing (60.2%).

Only 26.4% of the cohort reported having PGx testing experience in the pediatric population in the last 12 months, with PGx test results used primarily for psychiatry and hematology/oncology medications.

Among selected specialties, psychiatry was most familiar with PGx and had the greatest number of providers with PGx testing experience. However, uncertainty about the clinical value of PGx testing was one of the top perceived challenges reported by this specialty group.

The majority (84%) of PGx test users reported making medication changes based on PGx test results in less than 25% of cases.

Pharmacists were more likely to have received PGx education or training than other provider groups; however, less than 20% of pharmacists reported having PGx testing experience in the past 12 months.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This publication is supported in part by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002535. The contents of this article are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No funded writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval. In addition, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Disclosure

The results of this study were presented, in part, as an abstract in Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 107 (S1), S16 (2020).

References

- 1.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(9), 793–795 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roden DM, McLeod HL, Relling MV et al. Pharmacogenomics. Lancet 394(10197), 521–532 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunnenberger HM, Crews KR, Hoffman JM et al. Preemptive clinical pharmacogenetics implementation: current programs in five US medical centers. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 55, 89–106 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahawi S, Naik H, Blake KV et al. Knowledge and attitudes on pharmacogenetics among pediatricians. J. Hum. Genet. 65(5), 437–444 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsey LB, Ong HH, Schildcrout JS et al. Prescribing prevalence of medications with potential genotype-guided dosing in pediatric patients. JAMA Netw. Open 3(12), e2029411 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JT, Ramsey LB, Van Driest SL, Aka I, Colace SI. Characterizing pharmacogenetic testing among Children's Hospitals. Clin. Transl. Sci. 14(2), 692–701 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman JM, Haidar CE, Wilkinson MR et al. PG4KDS: a model for the clinical implementation of pre-emptive pharmacogenetics. Am.J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 166C(1), 45–55 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gammal RS, Crews KR, Haidar CE et al. Pharmacogenetics for safe codeine use in sickle cell disease. Pediatrics 138(1), e20153479 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haidar CE, Relling MV, Hoffman JM. Preemptively precise: returning and updating pharmacogenetic test results to realize the benefits of preemptive testing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 106(5), 942–944 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manzi SF, Fusaro VA, Chadwick L et al. Creating a scalable clinical pharmacogenomics service with automated interpretation and medical record result integration – experience from a pediatric tertiary care facility. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 24(1), 74–80 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey LB, Prows CA, Zhang K et al. Implementation of pharmacogenetics at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center: lessons learned over 14 years of personalizing medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 105(1), 49–52 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weitzel KW, Smith DM, Elsey AR et al. Implementation of standardized clinical processes for TPMT testing in a diverse multidisciplinary population: challenges and lessons learned. Clin. Transl. Sci. 11(2), 175–181 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cicali EJ, Blake K, Gong Y et al. Novel implementation of genotype-guided proton pump inhibitor medication therapy in children: a pilot, randomized, multisite pragmatic trial. Clin. Transl. Sci. 12(2), 172–179 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claudio-Campos K, Padron A, Jerkins G et al. Acceptability, feasibility, and utility of integrating pharmacogenetic testing into a child psychiatry clinic. Clin. Transl. Sci. 14(2), 589–598 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huddleston KL, Klein E, Fuller A, Jo G, Lawrence G, Haga SB. Introducing personalized health for the family: the experience of a single hospital system. Pharmacogenomics 18(17), 1589–1594 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregornik D, Salyakina D, Brown M, Roiko S, Ramos K. Pediatric pharmacogenomics: challenges and opportunities: on behalf of the Sanford Children's Genomic Medicine Consortium. Pharmacogenomics J. 21, 8–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts TA, Wagner JA, Sandritter T, Black BT, Gaedigk A, Stancil SL. Retrospective review of pharmacogenetic testing at an Academic Children's Hospital. Clin. Transl. Sci. 14(1), 412–421 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Driest SL, McGregor TL. Pharmacogenetics in clinical pediatrics: challenges and strategies. Per. Med. 10(7), 661–671 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haga SB. Pharmacogenomic testing in pediatrics: navigating the ethical, social, and legal challenges. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 12, 273–285 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hines RN. Ontogeny of human hepatic cytochromes P450. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 21(4), 169–175 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allegaert K, Van Den Anker J. Ontogeny of Phase I metabolism of drugs. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 59(Suppl. 1), S33–S41 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens JC, Marsh SA, Zaya MJ et al. Developmental changes in human liver CYP2D6 expression. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36(8), 1587–1593 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blake MJ, Gaedigk A, Pearce RE et al. Ontogeny of dextromethorphan O- and N-demethylation in the first year of life. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 81(4), 510–516 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koukouritaki SB, Manro JR, Marsh SA et al. Developmental expression of human hepatic CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 308(3), 965–974 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green DJ, Mummaneni P, Kim IW, Oh JM, Pacanowski M, Burckart GJ. Pharmacogenomic information in FDA-approved drug labels: application to pediatric patients. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 99(6), 622–632 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aka I, Bernal CJ, Carroll R, Maxwell-Horn A, Oshikoya KA, Van Driest SL. Clinical pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450-associated drugs in children. J. Pers. Med. 7(4), 14 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown JT, Bishop JR, Sangkuhl K et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for cytochrome P450 (CYP)2D6 genotype and atomoxetine therapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 106(1), 94–102 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanek EJ, Sanders CL, Taber KA et al. Adoption of pharmacogenomic testing by US physicians: results of a nationwide survey. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 91(3), 450–458 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haga SB, Burke W, Ginsburg GS, Mills R, Agans R. Primary care physicians' knowledge of and experience with pharmacogenetic testing. Clin. Genet. 82(4), 388–394 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansen Taber KA, Dickinson BD. Pharmacogenomic knowledge gaps and educational resource needs among physicians in selected specialties. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 7, 145–162 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vorderstrasse A, Katsanis SH, Minear MA et al. Perceptions of personalized medicine in an Academic Health System: educational findings. J. Contemp. Med. Educ. 3(1), 14–19 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deininger KM, Tsunoda SM, Hirsch JD et al. National survey of physicians' perspectives on pharmacogenetic testing in solid organ transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 34(10), e14037 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith DM, Namvar T, Brown RP et al. Assessment of primary care practitioners' attitudes and interest in pharmacogenomic testing. Pharmacogenomics 21(15), 1085–1094 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemke AA, Hutten Selkirk CG, Glaser NS et al. Primary care physician experiences with integrated pharmacogenomic testing in a community health system. Per. Med. 14(5), 389–400 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zakinova A, Long-Boyle JR, French D et al. A practical first step using needs assessment and a survey approach to implementing a clinical pharmacogenomics consult service. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2(3), 214–221 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weitzel KW, Aquilante CL, Johnson S, Kisor DF, Empey PE. Educational strategies to enable expansion of pharmacogenomics-based care. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 73(23), 1986–1998 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karas Kuzelicki N, Prodan Zitnik I, Gurwitz D et al. Pharmacogenomics education in medical and pharmacy schools: conclusions of a global survey. Pharmacogenomics 20(9), 643–657 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Just KS, Turner RM, Dolzan V et al. Educating the next generation of pharmacogenomics experts: global educational needs and concepts. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 106(2), 313–316 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gammal RS, Caudle KE, Quinn CT et al. The case for pharmacogenetics-guided prescribing of codeine in children. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 105(6), 1300–1302 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US FDA. FDA Drug safety communication: FDA restricts use of prescription codeine pain and cough medicines and tramadol pain medicines in children; recommends against use in breastfeeding women (2017). (2020). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-restricts-use-prescription-codeine-pain-and-cough-medicines-and#:~:text=used%20for%20pain%3A-,Codeine%20should%20not%20be%20used%20to%20treat%20pain%20or%20cough,or%20difficult%20breathing%20and%20death

- 41.Evans WE, Pui CH, Yang JJ. The promise and the reality of genomics to guide precision medicine in pediatric oncology: the decade ahead. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 107(1), 176–180 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Relling MV, Schwab M, Whirl-Carrillo M et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for thiopurine dosing based on TPMT and NUDT15 genotypes: 2018 update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 105(5), 1095–1105 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Clinical use of pharmacogenetic tests in prescribing psychotropic medications for children and adolescents (March 2020). (2020). https://www.aacap.org/aacap/Policy_Statements/2020/Clinical-Use-Pharmacogenetic-Tests-Prescribing-Psychotropic-Medications-for-Children-Adolescents.aspx

- 44.Ramsey LB, Namerow LB, Bishop JR et al. Thoughtful clinical use of pharmacogenetics in child and adolescent psychopharmacology. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry (2020) (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caraballo PJ, Hodge LS, Bielinski SJ et al. Multidisciplinary model to implement pharmacogenomics at the point of care. Genet. Med. 19(4), 421–429 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aquilante CL, Kao DP, Trinkley KE et al. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics via a health system-wide research biobank: the University of Colorado experience. Pharmacogenomics 21(6), 375–386 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu M, Vnencak-Jones CL, Roland BP et al. A tutorial for pharmacogenomics implementation through end-to-end clinical decision support based on ten years of experience from PREDICT. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109(1), 101–115 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown JT, Gregornik D, Kennedy MJ. Advocacy, Research C. The role of the pediatric pharmacist in precision medicine and clinical pharmacogenomics for children. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 23(6), 499–501 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]