Abstract

Background

Prostate adenocarcinoma rarely metastasize to the brain. The aim of this study was to understand the risk association and survival outcomes comparing prostate cancer with brain metastasis (group 1) with prostate cancer without brain metastasis (group 2) at the time of initial diagnosis.

Material/Methods

We searched the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) statewide cancer registries for all cases of stage IV prostate cancer adenocarcinoma diagnosed between 2010 and 2015. We used the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression to analyze survival outcomes and logistic regression to study the association between the presence of brain metastasis and potential risk variables. Exclusion criteria were the presence of neuroendocrine and small cell histology.

Results

The study included 14 753 patients. Of these, 187 patients were in group 1 (with brain metastasis) and 14 566 were in group 2 (without brain metastasis). When comparing the metastases distribution at the time of initial presentation between group 1 and group 2, the occurrence of bone metastasis was similar in the 2 groups (87% vs 90%); however, liver metastasis (13% vs 4%) and lung metastasis (29% vs 7%) were significantly higher in group 1. We found a strong association between brain metastasis and visceral metastasis. There was no association between age, race, and grade and having brain metastasis.

Conclusions

Our analysis shows that visceral metastasis is associated with a higher risk of brain metastasis. Presence of a visceral metastasis can be a useful parameter to consider early magnetic resonance imaging of the brain to facilitate diagnosis of asymptomatic brain metastasis.

Keywords: Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal; Blood-Brain Barrier; Diagnostic Imaging

Background

Prostate cancer with brain metastasis is rare and usually occurs late in the course of the disease. Prostate cancer metastasis disseminates predominantly to the bones (87%), followed by distant lymph nodes (10.6%); however, it can eventually spread to other organs such as the liver (10.2%), lungs (9.1%), and brain [1]. The most common site for brain metastasis is in the leptomeninges, followed by the cerebrum and cerebellum [2,3]. In 1940, Dr. Oscar Vivan Batson first discovered the importance of the venous plexus (which was then named the Batson’s venous plexus) in the human body [4], which is a network of veins connecting the paravertebral veins to the pelvic veins and the thoracic veins to the intraspinal (basivertebral) veins [5]. These plexuses are important in understanding how prostate cancer spreads. Metastasis to the brain can be explained by the hematogenous spread, Batson’s venous plexus network, or direct extension from the sphenoid bone or adjacent sinuses [6].

Patients with brain metastasis are asymptomatic in the early stage but, later, they can present with headache, confusion, memory loss, seizures, hemiparesis, or aphasia [7]. The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain only for symptomatic patients. Hatzoglou et al conducted an 11-year analysis of MRI characteristics in prostate brain metastasis. A total of 21 patients were included in the study; one-third of those patients presented with a hemorrhagic pattern similar to that of other cancers, such as renal cell cancer and melanoma. The rest of the patients presented with varied patterns (from purely solid to mixed cystic and solid or ring-like patterns) [8].

Small cell histology originating from the prostate behaves like small cell cancers from any other primary site and has a high tendency to spread to the brain, compared with adenocarcinoma histology [9–11]. Prostate adenocarcinoma brain metastases have not been well described in the literature. Thus, we used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data to determine and compare the incidence, correlation, and survival outcomes of cohorts of patients with prostate adenocarcinoma with brain metastasis and without brain metastasis.

Material and Methods

Data Source

Data were extracted from the SEER database for all stage IV prostate cancer adenocarcinoma diagnosed between 2010 and 2015. We searched for prostate cancer patients using the International Classification of Disease for Oncology (3rd edition) histological subtype code “adenocarcinoma, NOS” 8140/3. We excluded cases that were not primary or first prostate cancer or were without active follow-up information (only autopsy or death certificate records), and histological subtype codes “small cell carcinoma, NOS” 8041/3, 8043/3, “large cell carcinoma, NOS” 8012/3, and “large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma” 8013/3. Data, when abstracted, were deidentified, and therefore, this study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Definition of Variables

The demographic variables of interest for these patients included age at diagnosis, sex, race, histology grade, sites of distant metastases (liver, lung, bone, and brain), and 5-year survival outcomes. Race was categorized as White, Black, and other (other and unknown). Histology grades were based on the 2014 SEER Gleason conversion table. For this analysis, we combined grades 1 and 2 and grades 3 and 4. Grades 1 and 2 are groups of patients with Gleason scores from 2 to 7 and histology ranging from well differentiated to moderately differentiated. Grades 3 and 4 are groups of patients with Gleason scores from 8 to 10 and poorly differentiated histology.

Distant metastases to the bone, liver, lung, and brain were examined. Brain metastasis only was identified as “code 1” and represented “mets at diagnosis”. Brain involvement could have been single or multiple sites and could have included clinical or pathological information. No brain metastasis was identified as “code 0”, which has no clinical or pathological or imaging evidence for brain metastasis.

We further inquired for liver, lung, and bone metastases in the patients with brain metastasis at diagnosis and patients without brain metastasis at diagnosis. Surgery at metastasis site, and chemotherapy were categorized into “yes” and “no/unknown” statuses. The SEER data provided only “surgery at metastasis” but there was no information provided on the location of the surgery at metastasis site; for example, brain surgery vs visceral surgery. However, we selected patients who presented with brain metastasis at the time of diagnosis. We assumed that “surgery at metastasis” site would refer to brain surgery, since visceral surgery would rarely be performed in patients having both brain and visceral metastases.

Survival was defined as the time from diagnosis until death due to all causes. We tracked survival outcomes for 5 years. Patients with missing or unknown information and TNM/AJCC staging were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

SEER *Stat software (version 8.3.5) was used to extract data. Patients were divided into 2 cohorts: brain metastasis and no brain metastasis. Descriptive analysis was conducted to evaluate the distribution of demographic variables, presence of visceral metastasis, grading, and treatment. Differences of categorical variables between the 2 groups were assessed using the chi-squared test. Overall survival distribution was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used for comparison of survival distributions across different subgroups. Univariate and multivariable analyses were conducted using the Cox regression model. All tests were 2-sided, and a P value of <0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Demographics

We identified a total of 14 753 patients with stage IV prostate adenocarcinoma between 2010 and 2015 using SEER data. We divided the population into 2 main groups: patients with brain metastasis (group 1) and patients without brain metastasis (group 2). Of these, 187 patients were in group 1 and 14 566 were in group 2. The incidence of brain metastasis among the 2 groups was 1.26%. The clinicopathological characteristics of all patients are listed in Table 1. In group 1, the median age was 67 years (range, 42–92 years), with race of 75% White and 19% Black. The majority of patients (89%) had grade 3–4 and 11% had grade 1–2 metastases. Most patients in group 1 had metastases to bone (87%), followed by lung (29%) and liver (13%). Therapy received in group 1 was divided into chemotherapy and brain surgery. Only 19% of these patients underwent brain metastasis resection and 13% received chemotherapy. In group 2, the median age was 71 years (range, 34–99 years), with race of 75% White and 18% Black. The majority of patients (91%) had grade 1–2; only 9% of patients had grade 3–4 metastases. Most of these patients had metastases to bone (90%), followed by lung (7%) and liver (4%).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Variables | Brain met at diagnosis (n=187) | No brain met at diagnosis (n=14566) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 0.003* | ||

| Median (range) | 67 (42–92) | 71 (34–99) | |

| Age group | 0.048 | ||

| 75 and younger | 132 (71%) | 9260 (64%) | |

| >75 | 55 (29%) | 5306 (36%) | |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 141 (75%) | 10845 (75%) | 0.65 |

| African American | 35 (19%) | 2669 (18%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 11 (6%) | 1052 (7%) | |

| Grade** | 0.46 | ||

| 1 and 2 | 9 (11%) | 8323 (91%) | |

| 3 and 4 | 71 (89%) | 819 (9%) | |

| Insurance | 0.089 | ||

| Yes | 170 (93%) | 13547 (96%) | |

| No | 12 (7%) | 575 (4%) | |

| Liver metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 22 (13%) | 570 (4%) | |

| No | 150 (87%) | 13928 (96%) | |

| Lung metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 49 (29%) | 1074 (7%) | |

| No | 119 (71%) | 13292 (93%) | |

| Bone metastasis | 0.16 | ||

| Yes | 161 (87%) | 13083 (90%) | |

| No | 24 (13%) | 1436 (10%) | |

| Surgery at metastasis site | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 35 (19%) | 366 (3%) | |

| No | 152 (81%) | 13881 (97%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.20 | ||

| Yes | 25 (13%) | 1528 (10%) | |

| No | 162 (87%) | 13038 (90%) | |

| Patient status | <0.001 | ||

| Alive | 3 (2%) | 463 (3%) | |

| Dead | 132 (71%) | 7044 (48%) | |

| Untraced | 52 (28%) | 7059 (49%) |

Calculated by Mann-Whitney U Test;

Gleason conversion table 2014.

Grade 1 and 2 – groups of patients with Gleason score from 2 to 7 and histology ranging from well differentiated to moderately differentiated. Grade 3 and 4 – groups of patients with Gleason score 8 to 10 and poorly differentiated histology. Met – metastasis; PSA – prostate-specific antigen.

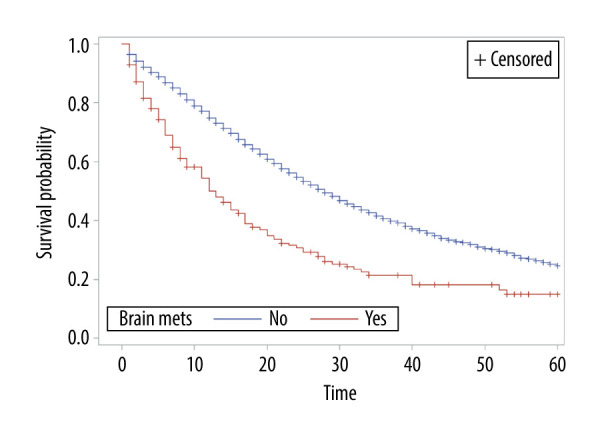

Survival Analyses

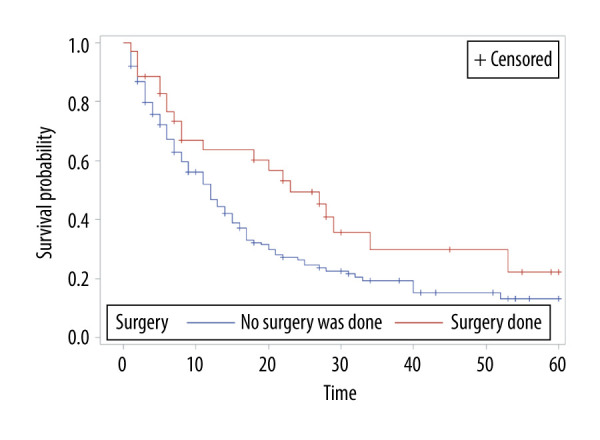

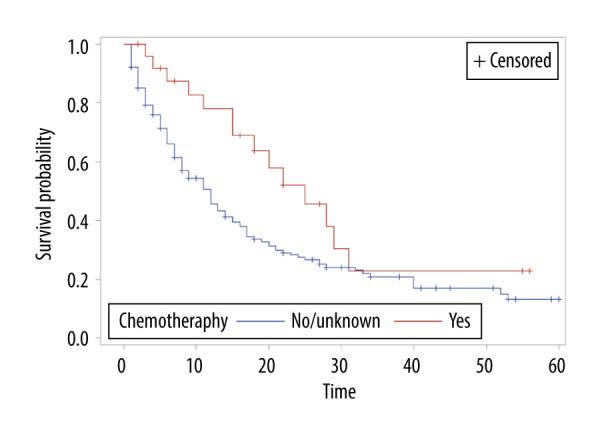

The overall survival of group 1 was 50% after 1 year, 30.75% after 2 years, 21.4% after 3 years, and 15% after 5 years, while the overall survival of group 2 at the same time periods was 75%, 54.6%, 40.7%, and 24.7%, respectively. Median survival was 12 months in group 1 and 28 months in group 2 (P<0.001) (Figure 1). In group 1, a significant survival benefit was seen in patients who underwent resection at metastasis sites (hazard ratio 1.62, P=0.04) (Figure 2) and who received chemotherapy (hazard ratio 1.8, P=0.04) (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Overall survival of patients by presence or absence of brain metastasis.

Figure 2.

Overall survival of patients with brain metastasis by surgery status.

Figure 3.

Overall survival of patients with brain metastasis by chemotherapy status.

Logistic regression was used to study the association between brain metastasis (yes/no) and other risk factors (Table 2). Brain metastasis was statistically significantly associated with liver metastasis (P<0.001), lung metastasis (P<0.001) and age group (≤75 vs >75) (P=0.048), but not with race (P=0.77), bone metastasis (P=0.17), or chemotherapy (P=0.20) by univariate analysis (Table 2). Liver metastasis and lung metastasis were also significant by multivariable analyses (Table 2). There was a strong association between brain metastasis and visceral metastasis; these patients had a 2-fold to 4-fold higher risk of having brain metastasis (P<0.001) (Table 3). The odds ratio for liver metastasis was 2.85 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.89–4.2) and for lung metastasis was 4.6 (95% CI 3.3–6.4) (Table 3). There was no association between age, race, grade, or bone metastasis and risk of having brain metastasis (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of variables associated with prostate brain metastasis.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Liver metastasis | 5.38 (3.7–7.8) | <0.001 | 2.85 (1.9–4.3) | <0.001 |

| Lung metastasis | 5.96 (4.4–8.0) | <0.001 | 4.62 (3.3–6.4) | <0.001 |

| Age ≤75 | 1.38 (1–1.9) | 0.05 | ||

| Race | 0.95 (0.7–1.3) | 0.8 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.76 (0.5–1.2) | 0.2 | ||

| Bone metastasis | 1.36 (0.9–2.1) | 0.2 | ||

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis of association between prostate brain metastasis and other variables.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (≤75 vs >75 years) | 0.72 (0.50–1.03) | 0.07 | 0.77 (0.53–1.1) | 0.16 |

| Surgery (yes vs no) | 0.62 (0.39–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.68 (0.42–1.09) | 0.11 |

| Chemotherapy (yes vs no) | 0.56 (0.32–0.98) | 0.04 | 0.60 (0.34–1.05) | 0.07 |

| Race (white vs other) | 1.06 (0.71–1.58) | 0.8 | ||

| Lung metastasis (yes vs no) | 0.71 (0.47–1.07) | 0.1 | ||

| Bone metastasis (yes vs no) | 1.23 (0.74–2.05) | 0.43 | ||

| Liver metastasis (yes vs no) | 0.91 (0.54–1.55) | 0.7 | ||

| Grade group (I/II vs III/IV) | 0.59 (0.23–1.49) | 0.26 | ||

Discussion

This study provides a large population-based analysis to explore the incidence, correlation, and outcomes of patients with prostate adenocarcinoma, with and without brain metastasis. The incidence of prostate adenocarcinoma brain metastasis among the 2 groups was 1.26%. Our results showed that the risk of brain metastasis was 2-fold to 4-fold higher in patients who had visceral (liver or lung) metastasis, independent of age, race, histological grade, Gleason score, and bone metastasis. This is an interesting finding, but better understanding of the mechanism and molecular biology of brain metastasis in prostate cancer is needed. The gene sequencing in patients with prostate brain metastases was studied retrospectively at a single center. The germline mutations (ATM, BRCA1, BRIP2, MUTYH) on primary prostate specimens and PTEN loss in metastatic specimens were found, but further study is warranted to confirm the association [12].

In our study, the majority (89%) of patients with brain metastasis had Gleason scores from 8 to 10 and poorly differentiated histology, whereas patients without brain metastasis (91%) had Gleason scores from 2 to 7 and histology ranging from well differentiated to moderately differentiated. Gleason score is one of the strongest known prognostic factors in metastatic prostate cancer [13]. Of patients with prostate brain metastasis at the time of diagnosis in the present study, the majority (87%) also had coexisting bone metastasis, 29% had coexisting lung metastasis, and 13% had coexisting liver metastasis. Liver metastasis has been shown to be associated with worse survival [14]. Our finding is consistent with other previous findings [14].

The management of solitary brain metastasis is similar to that of any other cancer type. Surgical resection followed by stereotactic radiotherapy to the surgical bed is still considered the standard of care approach. Some of the systemic therapies are limited in treating brain metastasis owing to their inability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). For example, enzalutamide, an androgen receptor blocker, has the ability to cross the BBB and can be considered for use in brain metastasis; however, caution is warranted because enzalutamide increases the risk of seizures in patients with brain metastasis [15]. One animal model demonstrated that darolutamide has a 10-fold lower BBB penetration than enzalutamide [16]. The selective inhibition of CYP17 C17,20-lyase of abiraterone acetate does penetrate the BBB in animal studies; however, human studies are lacking. Docetaxel, a microtubule inhibitor, shows only limited activity against brain metastasis [17]. Preclinical data supports that cabazitaxel has better BBB penetration than docetaxel owing to its poor affinity to the p-glycoprotein efflux pump [18,19].

In our study, the median age in patients with brain metastasis was slightly younger than in patients without brain metastasis (67 vs 71 years); however, interestingly, only 19% were reported to undergo surgery at the metastasis site, and 13% received systemic chemotherapy. Only a few of the patients with brain metastasis underwent an intensive treatment approach, which could be owing to their poor performance status or poor organ function. In our study, overall survival was prolonged in patients who underwent surgery at metastasis sites and received chemotherapy. The name of the chemotherapy administered was not available in the SEER database. The median 5-year survival of patients with prostate cancer presenting with brain metastasis is poor; in our study it was only 12 months.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, the risk of selection bias is high as it is a retrospective study. Second, the SEER database does not provide details of treatment, for example, name of chemotherapy, name of hormonal therapy, exact location of surgery at metastasis site, brain resection information, and pathology information from brain resection; also, the molecular information was limited. We did not include radiation information in our study because these data were difficult to interpret with regard to which site was treated (prostate, bone metastasis, or brain metastasis site).

Conclusions

Prostate cancer with brain metastasis has a poor prognosis. Our study shows that visceral metastases are associated with a higher risk of brain metastasis and, thus, early MRI of the brain should be considered to diagnose asymptomatic brain metastasis, as early intervention would improve overall survival outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Donna Gilbreath in the Markey Cancer Center’s Research Communications Office for her assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of support: This research was supported by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30CA177558).

References

- 1.Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: A population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210–16. doi: 10.1002/pros.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutton R, Maguire J, Amer T, et al. Intracranial metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate presenting with symptoms of spinal cord compression. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:75–76. doi: 10.1007/s12262-014-1143-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taddei G, Marzi S, Coletti G, et al. Brain metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma: Case report and review of literature. World J Oncol. 2012;3:83–86. doi: 10.4021/wjon442w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batson OV. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann Surg. 1940;112:138–49. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194007000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiltse LL, Amster J, Dimartino P, Ravessoud FA. Relationship of the dura, Hofmann’s ligaments, Batson’s plexus, and a fibrovascular membrane lying on the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies and attaching to the deep layer of the posterior longitudinal ligament. An anatomical, radiologic, and clincial study. Spine. 1993;18:1030–43. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199306150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capito PRWH, Brem H, Ahn HS, Bryan RN. Magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of an intracranial metastasis of adenocarcioma of the prostate: case report. Md Med J (Baltimore, MD 1985) 1991;40:113–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tremont-Lukats IW, Bobustuc G, Lagos GK, et al. Brain metastasis from prostate carcinoma: The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2003;98:363–68. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatzoglou V, Patel GV, Morris MJ, et al. Brain metastases from prostate cancer: An 11-year analysis in the MRI era with emphasis on imaging characteristics, incidence, and prognosis. J Neuroimaging. 2014;24:161–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2012.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleichner JC, Chun B, Klappenbach RS. Pure small-cell carcinoma of the prostate with fatal liver metastasis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:1041–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oesterling JE, Hauzeur CG, Farrow GM. Small cell anaplastic carcinoma of the prostate: A clinical, pathological and immunohistological study of 27 patients. J Urol. 1992;147:804–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tetu B, Ro JY, Ayala AG, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Part I. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Cancer. 1987;59:1803–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870515)59:10<1803::aid-cncr2820591019>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mota JM, Teo M, Knezevic A, et al. Clinicopathologic and genomic characterization of parenchymal brain metastases (BM) in prostate cancer (PCa) J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:227–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rusthoven CG, Carlson JA, Waxweiler TV, et al. The prognostic significance of Gleason scores in metastatic prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:707–13. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao F, Wang J, Chen M, et al. Sites of synchronous distant metastases and prognosis in prostate cancer patients with bone metastases at initial diagnosis: A population-based study of 16,643 patients. Clin Transl Med. 2019;8:30. doi: 10.1186/s40169-019-0247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zurth C, Sandmann S, Trummel D, et al. Blood-brain barrier penetration of [14C]darolutamide compared with [14C]enzalutamide in rats using whole body autoradiography. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:345. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ten Tije AJ, Loos WJ, Zhao M, et al. Limited cerebrospinal fluid penetration of docetaxel. Anti-Cancer Drug. 2004;15:715–18. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000136882.19552.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cisternino S, Bourasset F, Archimbaud Y, et al. Nonlinear accumulation in the brain of the new taxoid TXD258 following saturation of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier in mice and rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1367–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mita AC, Denis LJ, Rowinsky EK, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of XRP6258 (RPR 116258A), a novel taxane, administered as a 1-hour infusion every 3 weeks in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:723–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]