Abstract

Objective:

Evaluate association between marijuana use and a composite adverse pregnancy outcome using biologic sampling.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study

Setting:

Single tertiary center

Population:

Young women (13–22 years old) with singleton, non-anomalous pregnancies delivered September 2011- May 2017

Methods:

Exposure was defined as marijuana detected on universal urine toxicology testing or by self-report. Multivariable logistic regression modeling was used to estimate the effect of any marijuana use on the primary composite outcome. Effect of marijuana exposure also estimated for self-reported use, toxicology-detected use, and multiple toxicology-detected uses.

Main outcome measure:

Primary composite outcome included spontaneous preterm birth, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, stillbirth, or small for gestational age.

Results:

Of 1206 pregnant young women, 17.5% (n=211) used marijuana. Among the women who used marijuana, 8.5% (n=18) were identified by self-report alone, 63% (n=133) by urine-toxicology alone, and 28.4% (n=60) by both. Urine toxicology testing results were available for 1092 (90.5%) births.

The composite outcome occurred more frequently in pregnancies exposed to marijuana (46 vs 34%, p<0.001). This remained significant after adjusting for race/ethnicity and tobacco in the multivariable model (aOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.09–2.05). When marijuana exposure was defined by self-report only, the association with the adverse pregnancy outcome became non-significant (aOR 1.01, 95% CI 0.62–1.64).

Conclusion:

In a population of young women with nearly universal biologic sampling, marijuana exposure was associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. The observed heterogeneity of findings in existing studies evaluating the impact of marijuana on mothers and neonates may result from incomplete ascertainment of exposure.

Keywords: Cannabis, Marijuana, THC, Pregnancy, Stillbirth, Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy, Preterm Birth, Small for Gestational Age

Tweetable abstract:

Marijuana use, as detected by universal urine testing, was associated with a composite adverse pregnancy outcome among young mothers.

Introduction

Past-month marijuana use among pregnant women in the United States increased by 62% from 2002 to 2014.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against marijuana use in pregnancy.2 However, results of prior studies are mixed regarding the effect of marijuana exposure on adverse perinatal outcomes.3 Several studies have found an association between marijuana and small for gestational age or low-birthweight, preterm birth, stillbirth, and hypertensive disorders4–11 while others have not.12–16

Some of the heterogeneity of findings in prior studies may be related to poor ascertainment of exposure with reliance on self-report. In a study by Shiono et al, 69% of pregnant women with a positive serum screen for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol denied use in a structured interview.16 A recent meta-analysis found no association between marijuana use and either low-birthweight or preterm birth after adjustment for confounding factors. However, it is notable that 20 of the 31 studies included in the meta-analysis relied on self-report to determine exposure.12

Reliance on self-report may result in misclassification of women who use marijuana as non-users. This could bias studies toward the null and underestimate the effects of marijuana use on perinatal outcomes. Modern studies with biologic sampling are needed to better characterize the risks of marijuana use in pregnancy. A maternity program for young mothers at our institution routinely screens all women using urine toxicology testing and a substance use questionnaire at the first prenatal visit. We therefore aimed to evaluate the association between marijuana use and a composite adverse pregnancy outcome in this population with universal biologic sampling. We hypothesized that marijuana exposure would be associated with increased odds of a composite adverse pregnancy outcome.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all mothers in a maternity program for young women (13–22 years old) who delivered at a single tertiary center between September 2011 and May 2017. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. Patients were not involved in the development of this retrospective study. Two of the co-authors (TDM and CH) had funding for portions of their time to be protected for research during the completion of this study. However, this project was not otherwise funded directly from those grants.

All women who receive prenatal care in the maternity program for young women are included in a prospectively collected database.17 For this study, included mothers were identified by matching women in the clinic database with a list of all women who delivered at University of Colorado Hospital over the same time period. Only women who received prenatal care in the maternity program for young women and ultimately delivered at University of Colorado Hospital were included in order to ensure that data for the primary composite outcome would be available for all women in the cohort.

Women with multiple gestations or major fetal congenital or chromosomal abnormalities were excluded given an established increased risk of the composite primary outcome in these populations. If a woman had more than one pregnancy during the study period, only the first pregnancy was included.

The primary exposure was marijuana use. Marijuana use was identified by either self-report on a clinic questionnaire or urine toxicology testing positive for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. All pregnant women in this clinic complete a uniformly administered questionnaire regarding tobacco, alcohol, and substance use at the first prenatal visit. In response to the question about marijuana use, a woman was considered positive for self-reported use if she responded “Yes, but I’ve cut down since I got pregnant”; “Yes, I’ve tried to cut down but I can’t”; or “Yes and I haven’t tried to quit”. She was considered negative for self-reported marijuana use if she responded “No”; “Yes, but I quit before I found out I was pregnant”; or “Yes, but I quit when I found out I was pregnant”. Self-reported tobacco, alcohol, and substance use were collected from the clinic database which stores all questionnaire data.

Young women in this clinic also undergo universal urine toxicology testing at the first prenatal visit. Women are made aware of this testing and are able to decline. Repeat urine toxicology testing is not mandated throughout the remainder of pregnancy or at delivery and is left to the discretion of health care providers. If urine toxicology testing was positive for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol at any of the prenatal visits or at the time of the delivery admission, then the participant was considered marijuana-exposed. Urine toxicology data were abstracted from the electronic medical record of each participant. The date and result of all positive urine toxicology tests was recorded.

The primary composite outcome included presence of any of the following: spontaneous preterm birth (<37 weeks gestation) with or without intact membranes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, stillbirth, or small for gestational age. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were defined as a clinical diagnosis made prior to or during the delivery hospitalization of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia with or without severe features, eclampsia, or HELLP syndrome. Stillbirth was defined as Apgar scores of 0 at 1 and 5 minutes. Small for gestational age was defined as birthweight less than the 10th percentile for gestational age and sex.18 A composite outcome was selected to capture many common adverse pregnancy outcomes which have been associated with marijuana use in the published literature, as well as account for competing outcomes such as stillbirth.3 Core outcome sets were not used in the design of the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes included abruption, mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery, infant birthweight, length, head circumference, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, and Apgar scores of <7 at 5 minutes.

Prevalence of marijuana use in our cohort was estimated at 18% from prior studies utilizing the clinic database. Institutional data for all deliveries at University of Colorado Hospital were used to estimate the anticipated prevalence of our composite outcome in the two groups. Based on these data, the prevalence of the composite outcome was expected to be 16% in women without marijuana use and 24% in women with marijuana use. A sample size of 1200 was calculated to have 80% power to detect an absolute difference in the prevalence of the composite outcome of 8%.

A trained obstetrician reviewed all maternal and neonatal charts to verify marijuana exposure and all components of the primary outcome. Charts were also reviewed and hand-abstracted for pregnancy history, maternal medical history, current pregnancy complications, infant length, and head circumference. Data for race/ethnicity, insurance status, maternal body mass index (BMI) at delivery, gestational age at delivery, infant birthweight, Apgar scores at 5 minutes, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, and infant discharge date were extracted from the electronic medical record.

Maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcomes were compared between young women exposed to marijuana versus women who were not exposed to marijuana using Student’s t or an exact chi-square test as appropriate.

A backwards stepwise multivariable logistic regression model was used to estimate the effect of marijuana exposure on the primary composite outcome. All clinical and demographic characteristics that were different (p<0.05) in bivariate comparisons were considered for inclusion in modeling. It was deemed of clinical importance to retain tobacco use in final modeling regardless of significance. Two separate models were performed to evaluate the impact of ascertainment of exposure by (1) either self-report or urine toxicology testing, or (2) self-report alone. A planned sensitivity analysis was performed which only included women with urine toxicology testing available. An exploratory analysis was also performed to evaluate if women with more than one positive urine toxicology test had higher odds of the composite adverse outcome.

A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). Figures were created using GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA.

Results

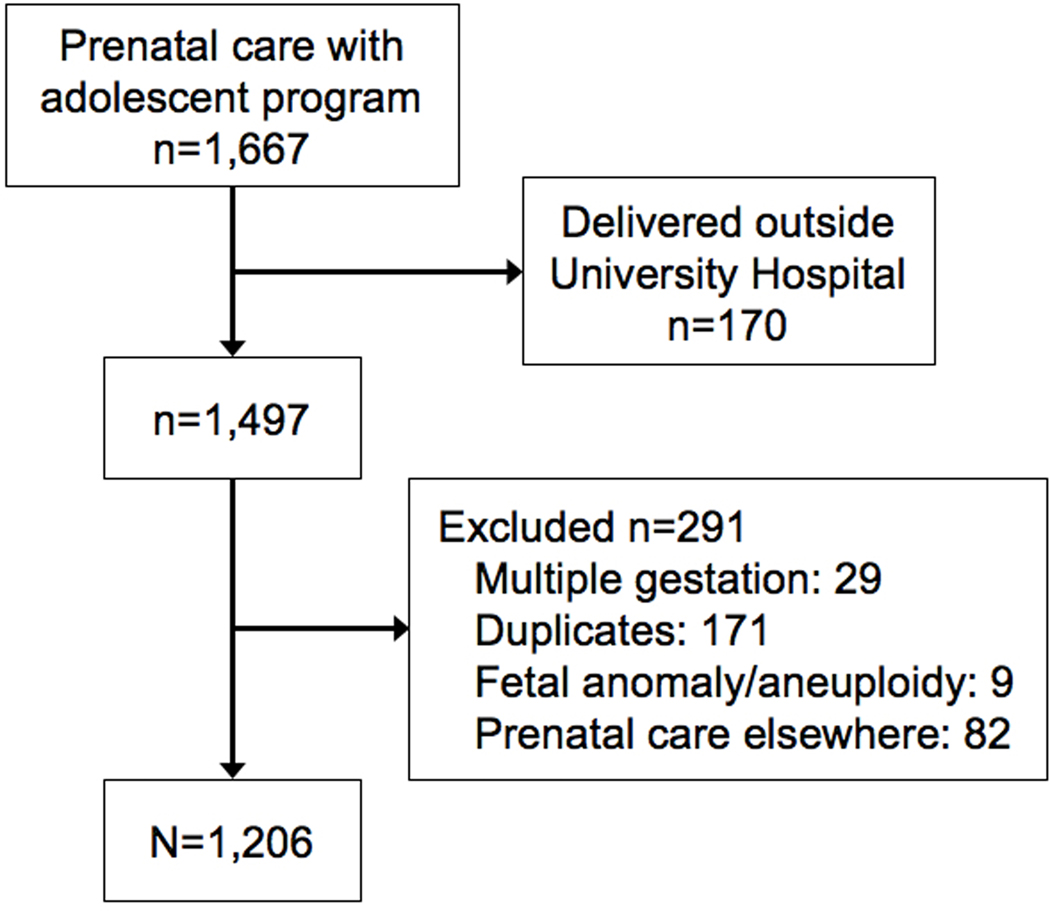

During the study period, 1,497 young women were identified who received prenatal care with the maternity program for young women and delivered at University of Colorado Hospital. Upon review of these records the following women were excluded: 29 multiple gestations, 171 duplicates, 9 major fetal anomalies or chromosomal abnormalities, and 82 who received prenatal care elsewhere for the pregnancy that occurred during the study time period (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Study Population

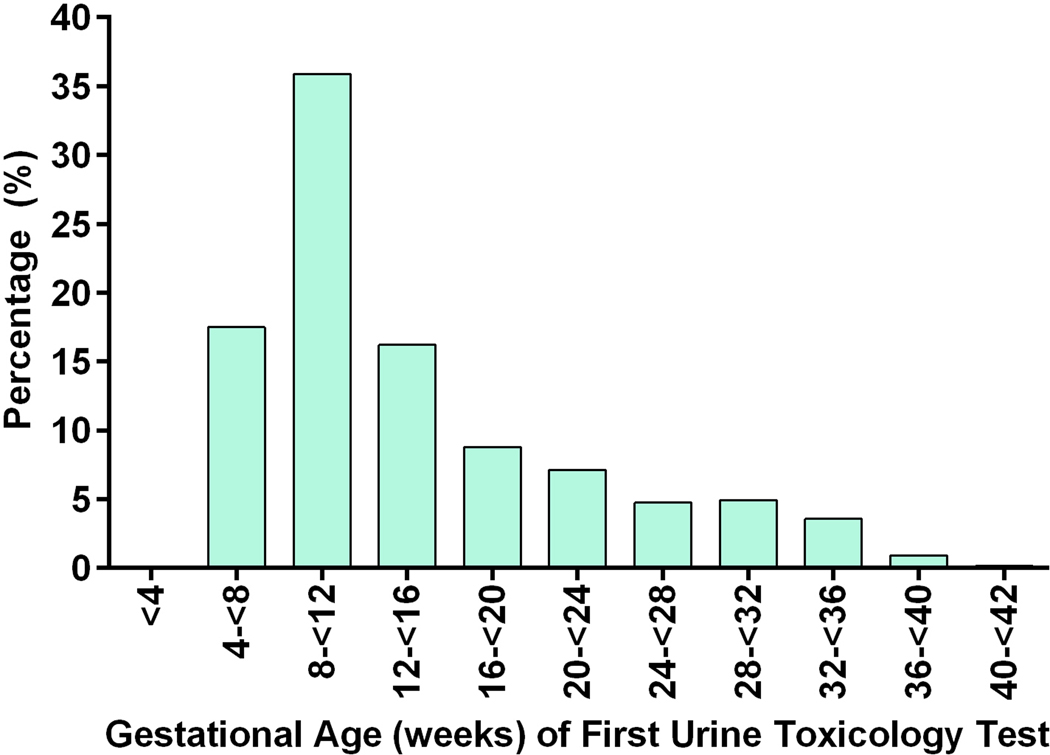

Of the remaining 1,206 included pregnancies, 17.5% (n=211) were exposed to marijuana. Among the women who used marijuana, 8.5% (n=18) were identified by self-report alone, 63% (n=133) by urine-toxicology alone, and 28.4% (n=60) by both. Urine toxicology testing results were available for 1,092 (90.5%) pregnancies. In the remaining cases, urine toxicology testing was ordered but not completed. Of the pregnancies with urine toxicology testing, 953 women (79.0%) had one test, 117 women (9.7%) had two tests, and 22 women (1.8%) had three or more tests during pregnancy. The earliest urine toxicology test was performed at a median gestational age of 11.4 weeks (IQR 8.6–18.2) and the second test at a median of 33.3 weeks (IQR 25.3–37.0). Figure 2 shows the distribution of gestational ages when the first urine toxicology test was performed.

Figure 2.

Gestational Age Distribution at Time of First Urine Toxicology Testing

Demographics differed between marijuana exposed and unexposed (Table 1). Women who used marijuana were slightly older, more frequently of Black or White race, and more likely to use tobacco and have a history of psychiatric disorder. Self-reported use of other illicit substances was rare and similar between groups; 1.9% of marijuana-exposed and 1.7% of marijuana-unexposed women reported some other substance use in the last 30 days (p>0.9) on the uniformly administered questionnaire. There was also a similar frequency of other substance use detected by urine toxicology: 2% in marijuana-exposed pregnancies compared with 1% in marijuana-unexposed pregnancies (p=0.28).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics in Marijuana Exposed and Unexposed Pregnancies

| Characteristic | Marijuana Exposed (n=211) | Marijuana Unexposed (n=995) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age (y) | 18.8 ± 1.5 | 18.5 ± 1.8 | 0.01 |

| BMI at delivery | 28.9 (28.2, 29.6) | 29.6 (29.3, 29.9) | 0.09 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| Hispanic | 54 (25.6) | 506 (50.9) | |

| Black | 77 (36.5) | 243 (24.4) | |

| White | 65 (30.8) | 160 (16.1) | |

| Other | 15 (7.1) | 86 (8.6) | |

| History of psychiatric disorder | 56 (26.5) | 167 (16.8) | 0.001 |

| Tobacco use* | 45 (21.3) | 47 (4.7) | <.001 |

| Alcohol use† | 0 (0) | 4 (0.4) | 0.63 |

| Other illicit drug use† | 23 (11.3) | 69 (7.8) | 0.12 |

| Cocaine† | 3 (1.4) | 16 (1.6) | >0.99 |

| Stimulants/Methamphetamine† | 0 (0) | 16 (1.6) | 0.59 |

| Hallucinogens* | 3 (1.4) | 9 (0.9) | 0.70 |

Data are mean ± SD or geometric mean and 95% confidence interval with p-value from two-sample t-test, or n (%) with p value from exact chi-square

Determined by self-report

Determined by self-report and urine toxicology testing

The primary composite outcome occurred more frequently in births exposed to marijuana as defined by positive self-report or urine toxicology positive for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (46 versus 34%, OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.23–2.24) (Table 2). This difference was driven by a higher prevalence of small for gestational age infants born to marijuana users (26 vs 17%, p= 0.005). The odds of the primary outcome remained higher for women who used marijuana compared with non-users after adjusting for race/ethnicity and tobacco in multivariable modeling (aOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.09–2.05) (Figure S1). Covariates eliminated during model selection were age, other illicit substance use, and history of psychiatric disorder.

Table 2.

Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes in Marijuana Exposed and Unexposed Pregnancies

| Outcome | Marijuana Exposed(n=211) | Marijuana Unexposed (n=995) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||

| Composite adverse outcome | 97 (46.0) | 337 (33.9) | <0.001 |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 37 (17.5) | 138 (13.9) | 0.20 |

| Spontaneous preterm delivery | 14 (6.6) | 60 (6.0) | 0.75 |

| Small for gestational age | 54 (25.7) | 170 (17.1) | 0.005 |

| Stillbirth | 4 (1.9) | 6 (0.6) | 0.08 |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||

| Abruption | 6 (2.8) | 7 (0.7) | 0.016 |

| Mode of delivery | 0.862 | ||

| NSVD | 163 (77.3) | 786 (79.0) | |

| FAVD | 9 (4.3) | 33 (3.3) | |

| VAVD | 7 (3.3) | 37 (3.7) | |

| Cesarean delivery | 32 (15.2) | 139 (14.0) | |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks, mean (SE) | 38.7 (0.23) | 39.1 (0.07) | 0.079 |

| Infant birthweight, g, mean (SE) | 2966 (43.2) | 3108 (16.4) | 0.002 |

| Infant length | 48.5 (0.27) | 48.8 (0.13) | 0.23 |

| Infant head circumference | 33.2 (0.15) | 33.6 (0.06) | 0.01 |

| NICU admission | 25 (11.8) | 106 (10.7) | 0.63 |

| Apgar score< 7 at 5 minutes | 5 (2.4) | 26 (2.6) | >0.99 |

Data reported as n (%) with p value from an exact chi-square.

NSVD is normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. FAVD is forceps-assisted vaginal delivery. VAVD is vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. NICU is neonatal intensive care unit.

A separate model was estimated to evaluate the impact of ascertainment of marijuana exposure by self-report alone on our primary outcome. When marijuana exposure was defined by self-report alone, there was no association between marijuana use and the composite adverse pregnancy outcome (aOR 1.01, 95% CI 0.62–1.64) (Figure S1).

Excluding young women without biologic sampling (n=114), odds of the composite adverse outcome were greater in magnitude when maternal marijuana use was defined by positive urine toxicology only (aOR 1.69, 95% CI 1.22–2.34) (Figure S1).

Again excluding those without biologic sampling, we compared prevalence of the primary outcome in young women with negative urine toxicology testing for marijuana with those who had one or more than one positive urine toxicology test. Those with more than one positive urine toxicology test had the primary outcome 68% of the time, compared with 46% for only one positive urine toxicology test, and 34% in those with no positive urine toxicology testing. Adjusted for race/ethnicity and tobacco use, the odds of the adverse outcome were significantly higher for women with only one positive urine toxicology test compared to women with negative testing (aOR 1.53, 95% CI 1.08–2.15). The odds increased when women with more than one positive urine toxicology test were compared to those with negative testing (aOR 3.58, 95% CI 1.50–8.54) (Figure S1).

For the secondary outcomes, marijuana exposed pregnancies had a higher incidence of abruption. None of the women with an abruption were also exposed to amphetamines or cocaine. Neonates born to marijuana-exposed pregnancies had significantly lower birthweight and smaller head circumferences (Table 2). These differences remained significant when evaluated in multivariable modeling. There were no differences between groups for other evaluated secondary outcomes.

Discussion

Main Findings

In a population with almost universal biologic sampling, marijuana exposure was associated with a composite adverse pregnancy outcome of spontaneous preterm birth, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, stillbirth, or small for gestational age. The difference in prevalence of the composite outcome was largely driven by a significantly higher number of small for gestational age infants born to marijuana users. Young women with a higher number of positive urine toxicology tests in pregnancy had increased odds of the composite adverse outcome. In addition, our study demonstrates that young women commonly use marijuana during pregnancy with a prevalence of 18%. The use of other illicit drugs and alcohol was rare.

Strengths and Limitations

The biggest strength of the study was urine testing for more than 90% of the study population, which allowed us to identify marijuana exposure that may otherwise be missed using self-report alone. Misclassification of women who use marijuana into the non-user group may bias results toward the null. Indeed, when our analysis was repeated using only self-report to classify marijuana exposure, marijuana was not associated with the composite primary outcome.

Other strengths include adjustment for many important confounding factors when estimating the impact of marijuana on adverse pregnancy outcomes. In addition, all components of the primary outcome were manually abstracted through primary chart review by a trained obstetrician.

Our study has limitations. There is a possibility of residual confounding with the retrospective cohort design. Given that the data were limited to those ascertained by retrospective chart review we were unable to make comparisons between groups for baseline characteristics such as differences in the home environment, lifestyle and general nutrition.

Urine toxicology testing is an imperfect means of identifying marijuana use as it can only detect metabolites for days to weeks after use, and it may identify a higher risk group of women with heavier use or more prolonged exposure. Additionally, urine tests may not be sensitive enough to detect marijuana exposure through passive or second-hand smoke. Our retrospective study was also unable to determine quantity or timing of marijuana use during the pregnancy.

Additionally, the composite outcome only included short-term pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. We studied an at-risk population of teenage and young adult women in which there were high rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The high rate of SGA in our cohort is similar to other cohorts of adolescent mothers.19 However, our findings may not be generalizable to lower risk populations. In addition, tobacco use was determined by self-report rather than biologic sampling of cotinine, which may have resulted in an underestimation of the effect of tobacco. However, others have demonstrated good agreement between self-reported tobacco use and biologic testing for cotinine.20

Interpretation

Other authors have similarly found an association between marijuana exposure and adverse pregnancy outcomes. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 articles by Gunn et al in 2016, marijuana use was associated with low birth weight as well as NICU admission.8 However, our results differ from the findings of a recent meta-analysis by Conner et al which concluded that marijuana use was not associated with preterm birth or low birth weight after adjustment for tobacco and other confounding variables.12 Importantly, 20 of the 31 studies included in this meta-analysis used self-report as the only means of determining exposure to marijuana. In addition, marijuana use was associated with both preterm birth and low birthweight among heavy (more than once per week) users in this meta-analysis.

We found an association between marijuana use and placental abruption. In the Conner et al meta-analysis there was also an observed association between abruption and marijuana exposure in unadjusted analysis, but this was no longer significant when adjusting for confounding factors.12 It is plausible that abruption could result from marijuana exposure, as the components of the composite outcome that were more common in exposed pregnancies all share underpinnings of placental insufficiency, and it is known that the endocannabinoid system is critical in implantation and placental formation.21

Most studies report a 2–5% prevalence of prenatal marijuana use.2 We found that in a state with legalized marijuana, use during pregnancy is very common among a group of high-risk young women. Other investigators similarly found a higher prevalence of use in young women. In a report of 280,000 pregnant women in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system, 22% of young females aged 12–17 and 19% of women aged 18–24 used marijuana as detected by self-report or urine testing.22 A cross-sectional cohort of women in Colorado with umbilical cord homogenate sampling for marijuana found a 22% prevalence of use, with proportionately more detected use among women less than 25 years of age.23 Future research endeavors should aim to understand factors linked to motivations for use during pregnancy (perceptions of medicinal use versus harm, addictive processes) that could guide interventions to address substance use among young pregnant women.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that marijuana use in pregnancy as determined by urine toxicology testing and self-report is associated with a composite adverse pregnancy outcome including spontaneous preterm birth, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, stillbirth, or small for gestational age. This association was not present when exposure was determined by self-report alone, indicating the importance of using biologic sampling for ascertainment of marijuana exposure.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Adjusted* Odds Ratios for the Effect of Marijuana Exposure on the Primary Composite Adverse Pregnancy Outcome

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Metz- NICHD 5K12HD001271-18. Dr. Hopfer- NIH DA032555 and DA035804.

Funding: Dr. Metz was supported by the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development under award number 5K12HD001271-18 during study completion. Dr. Hopfer receives support from DA032555 and DA035804. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interests:

The authors report no conflict of interest. Completed disclosure of interest forms are available to view online as supporting information.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board: 16-1976 On August 24, 2017.

References

- 1.Brown QL, Sarvet AL, Shmulewitz D, Martins SS, Wall MM, Hasin DS. Trends in Marijuana Use Among Pregnant and Nonpregnant Reproductive-Aged Women, 2002–2014. JAMA. 2017;317(2):207–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Obstetric P. Committee Opinion No. 722: Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;130(4):e205–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana Use in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Review of the Evidence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Burns L, Mattick RP, Cooke M. The use of record linkage to examine illicit drug use in pregnancy. Addiction. 2006;101(6):873–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dekker GA, Lee SY, North RA, McCowan LM, Simpson NA, Roberts CT. Risk factors for preterm birth in an international prospective cohort of nulliparous women. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e39154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Marroun H, Tiemeier H, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, et al. Intrauterine cannabis exposure affects fetal growth trajectories: the Generation R Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(12):1173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Northstone K, Team AS. Maternal use of cannabis and pregnancy outcome. Bjog-Int J Obstet Gy. 2002;109(1):21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunn JK, Rosales CB, Center KE, Nunez A, Gibson SJ, Christ C, et al. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2016;6(4):e009986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, Kingsbury AM, Hurrion E, Mamun AA, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(2):215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varner MW, Silver RM, Rowland Hogue CJ, Willinger M, Parker CB, Thorsten VR, et al. Association between stillbirth and illicit drug use and smoking during pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;123(1):113–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warshak CR, Regan J, Moore B, Magner K, Kritzer S, Van Hook J. Association between marijuana use and adverse obstetrical and neonatal outcomes. J Perinatol. 2015;35(12):991–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conner SN, Bedell V, Lipsey K, Macones GA, Cahill AG, Tuuli MG. Maternal Marijuana Use and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;128(4):713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.English DR, Hulse GK, Milne E, Holman CDJ, Bower CI. Maternal cannabis use and birth weight: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 1997;92(11):1553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linn S, Schoenbaum SC, Monson RR, Rosner R, Stubblefield PC, Ryan KJ. The Association of Marijuana Use with Outcome of Pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1983;73(10):1161–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Prunet C, Blondel B. Cannabis use during pregnancy in France in 2010. BJOG. 2014;121(8):971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiono PH, Klebanoff MA, Nugent RP, Cotch MF, Wilkins DG, Rollins DE, et al. The Impact of Cocaine and Marijuana Use on Low-Birth-Weight and Preterm Birth - a Multicenter Study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;172(1):19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheeder J, Scott S, Stevens-Simon C. The Electronic Report on Adolescent Pregnancy (ERAP). J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17(5):341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talge NM, Mudd LM, Sikorskii A, Basso O. United States birth weight reference corrected for implausible gestational age estimates. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):844–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones RL, Cederberg HM, Wheeler SJ, Poston L, Hutchinson CJ, Seed PT, et al. Relationship between maternal growth, infant birthweight and nutrient partitioning in teenage pregnancies. BJOG. 2010;117(2):200–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamy S, Hennart B, Houivet E, Dulaurent S, Delavenne H, Benichou J, et al. Assessment of tobacco, alcohol and cannabinoid metabolites in 645 meconium samples of newborns compared to maternal self-reports. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;90:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Correa F, Wolfson ML, Valchi P, Aisemberg J, Franchi AM. Endocannabinoid system and pregnancy. Reproduction. 2016;152(6):R191–R200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young-Wolff KC, Tucker LY, Alexeeff S, Armstrong MA, Conway A, Weisner C, et al. Trends in Self-reported and Biochemically Tested Marijuana Use Among Pregnant Females in California From 2009–2016. JAMA. 2017;318(24):2490–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metz TD, Silver RM, McMillin GA, Allshouse AA, Jensen TL, Mansfield C, et al. Prenatal Marijuana Use by Self-Report and Umbilical Cord Sampling in a State With Marijuana Legalization. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019;133(1):98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Adjusted* Odds Ratios for the Effect of Marijuana Exposure on the Primary Composite Adverse Pregnancy Outcome