Abstract

OBJECTIVE

While diabetes has been previously noted to be a stronger risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in women compared with men, whether this is still the case is not clear. Coronary artery calcium (CAC) predicts coronary heart disease (CHD) and CVD in people with diabetes; however, its sex-specific impact is less defined. We compared the relation of CAC in women versus men with diabetes for total, CVD, and CHD mortality.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We studied adults with diabetes from a large registry of patients with CAC scanning with mortality follow-up over 11.5 years. Cox regression examined the relation of CAC with mortality end points.

RESULTS

Among 4,503 adults with diabetes (32.5% women) aged 21–93 years, 61.2% of women and 80.4% of men had CAC >0. Total, CVD, and CHD mortality rates were directly related to CAC; women had higher total and CVD death rates than men when CAC >100. Age- and risk factor–adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) per log unit CAC were higher among women versus men for total mortality (1.28 vs. 1.18) (interaction P = 0.01) and CVD mortality (1.47 vs. 1.27) (interaction P = 0.04) but were similar for CHD mortality (1.48 and 1.48). For CVD mortality, HRs with CAC scores of 101–400 and >400 were 3.67 and 6.27, respectively, for women and 1.63 and 3.48, respectively, for men (interaction P = 0.04). For total mortality, HRs were 2.56 and 4.05 for women, respectively, and 1.88 and 2.66 for men, respectively (interaction P = 0.01).

CONCLUSIONS

CAC predicts CHD, CVD, and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes; however, greater CAC predicts CVD and total mortality more strongly in women.

Introduction

More than 30 million (>9%) U.S. adults have diabetes (1), which is associated with a greater risk for mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and all causes (2). People with diabetes are more likely to have coronary artery calcium (CAC) on computed tomography (CT) scanning, a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis, as well as greater levels of CAC (3–5). CAC, as measured by the Agatston CAC score (6), predicts CHD and CVD events in adults with diabetes, and a substantial proportion of adults with diabetes have CAC = 0 associated with a long-term event-free risk, identifying great heterogeneity in risk according to the level of CAC and indicating diabetes is not necessarily a CHD risk equivalent (5,7–9). Further, data from a large contemporary cohort (10) and from a large meta-analysis (11) also confirm diabetes not necessarily to be a CHD risk equivalent.

Diabetes has been reported to be a stronger risk factor for CVD events among women compared with men (12,13); however, whether this still remains the case in contemporary U.S. cohorts and what might explain such differences is uncertain. Among the general population, a recent investigation showed CAC was a stronger predictor of CVD death in women compared with men (14). Whether differences in subclinical atherosclerosis in those with diabetes might differentially identify a subset of women who are at particularly high risk is not known. Our investigation sought to examine whether there are sex differences in the relation of CAC with mortality from CHD, CVD, and all-causes in adults with diabetes.

Research Design and Methods

Study Population

We included women and men aged ≥18 years from the CAC Consortium, a prospective cohort study of 66,636 asymptomatic adults who received clinically indicated CAC scans from 2004 to 2014 at four U.S. clinical sites: Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (n = 13,972, years 1998–2010); Preva Health Wellness Diagnostic Center, Columbus, OH (n = 7,042, 1999–2003); Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA (n = 25,563, 1991–2008); and Minneapolis Heart Institute, Minneapolis, MN (n = 20,059, 1999–2005) (15).

Diabetes was reported by physician diagnosis or self-report by the participant taking hypoglycemic therapy. Information on fasting blood glucose (with ≥126 mg/dL defining diabetes) and insulin was also available at the Cedars-Sinai site. Overall, 4,503 participants were defined with diabetes for the current study.

Risk Factor, CAC Measures, and Mortality Ascertainment

Hypertension was present if there was a prior diagnosis of hypertension or treatment with antihypertensive therapy. Dyslipidemia was defined as a prior diagnosis of primary hyperlipidemia, prior diagnosis of dyslipidemia (elevated triglycerides and/or low HDL-cholesterol [C]), or treatment with any lipid-lowering drug. In patients with concomitant laboratory data, dyslipidemia was additionally considered present if LDL-C ≥160 mg/dL, HDL-C <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women, or fasting triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL. Smoking status was categorized as never, former, or current smoking. Family history of CHD was predominantly determined by the presence of a first-degree relative with a history of CHD; however, the Columbus, OH, site used age <55 years in old in a male relative and <65 years old in a female relative to define a positive family history (15). The 10-year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score was calculated in available patients with lipid levels and blood pressure measurements using the Pooled Cohort Risk Score (16).

Noncontrast cardiac-gated CT for CAC scanning was performed at each site according to a common standard protocol using a multidetector CT scanner or an electron beam scanner. Further details of the scanners and procedures used at each specific participating site in the CAC Consortium have been previously documented (15). CAC score was quantified using the Agatston method in all patients (6). In addition, from the sites with available data, scans were also evaluated according to the number of calcified lesions (Harbor-UCLA, Minneapolis Heart Institute) (n = 2,826), number of calcified vessels (left main, left anterior descending, left circumflex, right coronary artery) (Cedars, Harbor-UCLA, Minneapolis Heart Institute) (n = 4,046), CAC volume score (Cedars-Sinai, Minneapolis Heart Institute) (n = 2,047), and lesion size (Minneapolis Heart Institute) (n = 624) calculated by total volume score divided by number of lesions.

Causes of mortality were ascertained by National Death Index linkage over a mean follow-up of 11.5 years using a matching algorithm as has been previously described (15). The primary outcome of the CAC Consortium was cause-specific mortality, with first-order categorization into CVD mortality (inclusive of CHD, stroke, heart failure, and other cardiovascular mortality) and non-CVD mortality (cancer, pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal disease, nervous system disorders, endocrine/metabolic disease, injury and poisoning, or other) (15).

Statistical Analysis

Among subjects with diabetes in the CAC Consortium, we grouped subjects according to CAC score (0, 1–100, 101–400, >400) and compared age, ethnicity, risk factors (hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidemia, family history of CHD), and ASCVD risk score between women and men and separately in women and men according to CHD, CVD, and total mortality status using the Student t test or χ2 test of proportions for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. CHD, CVD, non-CVD, and total mortality rates (per 1,000 person-years) were calculated for each CAC group by sex and overall. Cox regression with calculated hazard ratios (HRs) examined the relation of CAC categories (0, 1–100, 101–400, and >400) and natural log of CAC+1 with CHD, CVD, all-causes, as well as non-CVD mortality in women and men separately, both for those with and without diabetes. Interaction terms of sex and CAC were also tested and done separately in those with and without diabetes as well as three-way interaction terms done between diabetes status, sex, and CAC. Cox regressions were also performed examining the strength of diabetes as a risk factor for each CHD, CVD, and total mortality within men and women separately, first without and then with the inclusion of coronary calcium (log-transformed) as a covariate, to explain whether possible sex differences in diabetes as a risk factor might be explained by CAC. Overall sample analyses were adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, family history, and smoking; sex-specific analyses were adjusted for the same factors except for sex. CAC volume (mm3), number of lesions, and lesion size (HU/mm3) all measured continuously were also related to mortality end points by similar analysis and comparing women versus men among those at or above and below median levels of these CAC measures. Statistical significance was set at α < 0.05; however, a corresponding Bonferroni P value of <0.017 is noted given the three primary outcomes (CHD, CVD, and total mortality). SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Our study included 4,503 individuals with diabetes, of which 74.2% were positive for CAC (score >0). Table 1 shows women (n = 1,461) compared with men (n = 3,042) were slightly older, with a lower BMI and less likely to be currently smoking but more likely to have a family history of CHD and hypertension. Our cohort was largely White (75%). Men compared with women with diabetes had higher mean 10-year ASCVD risk scores. Women had a much higher absence of CAC (38.8%) than did men (19.6%). While 29.2% of men with diabetes had CAC scores >400, only 16% of women were in this category (P < 0.0001 comparing CAC category distribution between men and women). Moreover, women with diabetes had on average fewer CAC lesions than men, fewer calcified vessels, and a lower volume score (all P < 0.0001) but similar lesion size. Overall, 2.3%, 3.9%, 10.9%, and 7.0% of subjects died of CHD, CVD, all-causes, and non-CVD causes, respectively, with no significant differences between men and women.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population of adults with diabetes (N = 4,503)

| Overall | Men | Women | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 4,503 | n = 3,042 (67.6%) | n = 1,461 (32.4%) | ||

| Age, years | 58.7 ± 10.7 | 58.1 ± 10.6 | 60.0 ± 10.9 | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (n = 2,234) | 29.8 ± 6.3 | 30.0 ± 5.8 | 29.5 ± 7.3 | 0.05 |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 2,748) | 0.07 | |||

| White | 2,073 (75.4) | 1,417 (77.0) | 656 (72.3) | |

| Asian | 190 (6.9) | 121 (6.6) | 69 (7.6) | |

| Black | 169 (6.2) | 106 (5.8) | 63 (6.9) | |

| Hispanic | 316 (11.5) | 197 (10.7) | 119 (13.1) | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Current smoker | 480 (10.7) | 345 (11.3) | 135 (9.2) | 0.03 |

| Any family history of CHD | 1,982 (44.0) | 1,248 (41.0) | 734 (50.2) | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2,811 (62.4) | 1,878 (61.7) | 933 (63.9) | 0.17 |

| Hypertension | 2,497 (55.5) | 1,616 (53.1) | 881 (60.3) | <0.0001 |

| ASCVD risk score | 0.20 ± 0.16 | 0.22 ± 0.16 | 0.15 ± 0.16 | <0.0001 |

| Total CAC Agatston score | <0.0001 | |||

| 0 | 1,163 (25.8) | 596 (19.6) | 567 (38.8) | |

| 1–100 | 1,349 (30.0) | 920 (30.2) | 429 (29.4) | |

| 101–400 | 870 (19.3) | 639 (21.0) | 231 (15.8) | |

| ≥401 | 1,121 (24.9) | 887 (29.2) | 234 (16.0) | |

| Total CAC lesions (n = 2,846) | 7.0 ± 10.6 | 8.0 ± 11.3 | 4.6 ± 8.4 | <0.0001 |

| Number of CAC vessels (n = 3,580) | <0.0001 | |||

| 0 | 1,059 (29.6) | 555 (23.3) | 504 (42.1) | |

| 1 | 538 (15.0) | 343 (14.4) | 195 (16.3) | |

| 2 | 579 (16.2) | 397 (16.7) | 182 (15.2) | |

| 3 | 864 (24.1) | 658 (27.6) | 206 (17.2) | |

| 4 | 540 (15.1) | 429 (18.0) | 111 (9.3) | |

| Total CAC volume (mm3) (n = 2,047) | 341.9 ± 731.4 | 402.0 ± 796.7 | 222.8 ± 562.5 | <0.0001 |

| Lesions size (HU/mm3) (total volume score/total lesions) (n = 624) | 29.0 ± 30.5 | 28.6 ± 29.8 | 30.1 ± 32.8 | 0.63 |

| CHD deaths | 107 (2.4) | 81 (2.7) | 26 (1.8) | 0.07 |

| CVD deaths | 175 (3.9) | 118 (3.9) | 57 (3.9) | 0.97 |

| Total deaths | 490 (10.9) | 334 (11.0) | 156 (10.7) | 0.76 |

| Non-CVD deaths | 315 (7.0) | 216 (7.1) | 99 (6.8) | 0.69 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or as n (%). BMI was available in 1,498 men and 736 women, race in 1,841 men and 907 women, total CAC lesions in 1,954 men and 892 women, number of CAC vessels in 2,382 men and 1,198 women, total volume score (mm3) in 1,361 men and 686 women, and lesions size (HU/mm3) information in 471 men and 153 women.

Table 2 shows the comparison of clinical and CAC data among women and men with diabetes. Women with versus without death from all causes, CVD, and CHD were more likely to be older, nonWhite (for CVD mortality only), and have dyslipidemia (for total and CVD mortality), with current smoking associated with total mortality and hypertension associated with CVD and total mortality. The 10-year ASCVD risk was also significantly higher in those who subsequently experienced versus did not experience death from all causes, CVD, or CHD. All three mortality end points were associated with higher CAC scores, greater number of lesions, calcified vessels, and volume score. Among men, greater age and non-White ethnicity were associated with each mortality end point; hyperlipidemia was only associated with CHD mortality. Total CAC score, 10-year ASCVD risk, number of calcified vessels, and volume score were all higher in those with versus without death from all causes, CVD, or CHD.

Table 2.

Comparison of risk factors and CAC measures by CHD, CVD, and total mortality status in women and men with diabetes

| CHD death | CVD death | Total death | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P value | Yes | No | P value | Yes | No | P value | |

| Women | |||||||||

| Diabetes (n = 1,461) | 26 (20.6) | 1,435 (6.6) | <0.0001 | 57 (19.5) | 1,404 (6.5) | <0.0001 | 156 (15.0) | 1,305 (6.2) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years (n = 1,461) | 72.8 ± 11.2 | 59.8 ± 10.8 | <0.0001 | 70.6 ± 11.3 | 59.6 ± 10.7 | <0.0001 | 69.7 ± 10.9 | 58.9 ± 10.4 | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (n = 736) | 28.3 ± 5.3 | 29.5 ± 7.3 | 0.58 | 28.7 ± 7.2 | 29.5 ± 7.3 | 0.54 | 28.7 ± 7.0 | 29.5 ± 7.3 | 0.38 |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 907) | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.10 | ||||||

| White | 8 (57.1) | 648 (72.6) | 19 (52.8) | 637 (73.1) | 57 (64.8) | 599 (73.1) | |||

| Asian | 1 (7.1) | 68 (7.6) | 3 (8.3) | 66 (7.6) | 6 (6.8) | 63 (7.7) | |||

| Black | 1 (7.1) | 62 (6.9) | 6 (16.7) | 57 (6.5) | 11 (12.5) | 52 (6.4) | |||

| Hispanic | 4 (28.6) | 91 (10.2) | 8 (22.2) | 87 (10.0) | 13 (14.8) | 82 (10.0) | |||

| Other | 0 (0.00) | 24 (2.7) | 0 (0.00) | 24 (2.8) | 1 (1.1) | 23 (2.8) | |||

| Current smoker (n = 1,461) | 3 (11.5) | 132 (9.2) | 0.68 | 9 (15.8) | 126 (9.0) | 0.08 | 25 (16.0) | 110 (8.4) | 0.002 |

| Hyperlipidemia (n = 1,461) | 21 (80.8) | 912 (63.6) | 0.07 | 45 (79.0) | 888 (63.3) | 0.02 | 112 (71.8) | 821 (62.9) | 0.03 |

| Hypertension (n = 1,461) | 20 (76.9) | 861 (60.0) | 0.08 | 45 (79.0) | 836 (59.5) | 0.003 | 112 (71.8) | 769 (58.9) | 0.002 |

| Any family history of CHD (n = 1,461) | 15 (57.7) | 719 (50.1) | 0.44 | 30 (52.6) | 704 (50.1) | 0.71 | 81 (51.9) | 653 (50.0) | 0.66 |

| Total CAC Agatston score (n = 1,461) | 960.1 ± 1,176.4 | 255.2 ± 693.1 | 0.005 | 1,116.7 ± 1,578.5 | 233.3 ± 628.3 | <0.0001 | 869.9 ± 1,434.5 | 195.8 ± 520.9 | <0.0001 |

| ASCVD risk score (n = 1,461) | 0.39 ± 0.24 | 0.15 ± 0.16 | <0.0001 | 0.36 ± 0.23 | 0.14 ± 0.15 | <0.0001 | 0.32 ± 0.22 | 0.13 ± 0.14 | <0.0001 |

| Total CAC Agatston score (n = 1,461) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 0 | 1 (3.9) | 566 (39.4) | 5 (8.8) | 562 (40.0) | 19 (12.2) | 548 (42.0) | |||

| 1–100 | 4 (15.4) | 425 (29.6) | 6 (10.5) | 423 (30.1) | 32 (20.5) | 397 (30.4) | |||

| 101–400 | 8 (30.8) | 223 (15.5) | 15 (26.3) | 216 (15.4) | 37 (23.7) | 194 (14.9) | |||

| ≥401 | 13 (50.0) | 221 (15.4) | 31 (54.4) | 203 (14.5) | 68 (43.6) | 166 (12.7) | |||

| Total CAC lesions (n = 892) | 10.7 ± 14.7 | 4.5 ± 8.3 | 0.16 | 11.2 ± 14.2 | 4.4 ± 8.1 | <0.0001 | 8.1 ± 10.9 | 4.2 ± 8.0 | 0.001 |

| Number of CAC vessels (n = 1,198) | 0.0006 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 0 | 1 (4.8) | 503 (42.7) | 5 (10.6) | 499 (43.4) | 17 (14.2) | 487 (45.2) | |||

| 1 | 3 (14.3) | 192 (16.3) | 3 (6.4) | 192 (16.7) | 19 (15.8) | 176 (16.3) | |||

| 2 | 4 (19.1) | 178 (15.1) | 9 (19.2) | 173 (15.0) | 22 (18.3) | 160 (14.8) | |||

| 3 | 10 (47.6) | 196 (16.7) | 16 (34.0) | 190 (16.5) | 32 (26.7) | 174 (16.1) | |||

| 4 | 3 (14.3) | 108 (9.2) | 14 (29.8) | 97 (8.4) | 30 (25.0) | 81 (7.5) | |||

| Total CAC Volume (mm3) (n = 686) | 631.1 ± 696.9 | 214.3 ± 556.9 | 0.006 | 777.5 ± 938.1 | 193.0 ± 519.6 | 0.0008 | 693.0 ± 1,000.3 | 162.5 ± 443.0 | <0.0001 |

| Lesion size (HU/mm3) (total volume score/total lesions) (n = 153) | 69.0 ± 40.8 | 29.6 ± 32.5 | 0.09 | 52.4 ± 26.0 | 28.5 ± 32.7 | 0.03 | 39.8 | 28.4 ± 33.7 | 0.13 |

| Men | |||||||||

| Diabetes (n = 3,042) | 81 (20.4) | 2,961 (6.7) | <0.0001 | 118 (17.4) | 2,924 (6.7) | <0.0001 | 334 (15.8) | 2,708 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years (n = 3,042) | 67.4 ± 10.7 | 57.9 ± 10.5 | <0.0001 | 67.3 ± 11.2 | 57.73 ± 10.4 | <0.0001 | 65.88 ± 11.3 | 57.14 ± 10.1 | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (n = 1,498) | 28.4 ± 6.3 | 30.1 ± 5.8 | 0.11 | 29.8 ± 7.4 | 30.03 ± 5.7 | 0.83 | 29.25 ± 6.4 | 30.10 ± 5.7 | 0.12 |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 1,841) | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| White | 42 (70.0) | 1,375 (77.2) | 67 (76.1) | 1,350 (77.0) | 161 (71.9) | 1,256 (77.7) | |||

| Asian | 2 (3.3) | 119 (6.7) | 3 (3.4) | 118 (6.7) | 13 (5.8) | 108 (6.7) | |||

| Black | 10 (16.7) | 96 (5.4) | 11 (12.5) | 95 (5.4) | 27 (12.1) | 79 (4.9) | |||

| Hispanic | 6 (10.0) | 144 (8.1) | 7 (8.0) | 143 (8.2) | 21 (9.4) | 129 (8.0) | |||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 47 (2.6) | 0 (0.00) | 47 (2.7) | 2 (0.9) | 45 (2.8) | |||

| Current smoker (n = 3,042) | 8 (9.9) | 337 (11.4) | 0.67 | 14 (11.9) | 331 (11.3) | 0.85 | 42 (12.6) | 303 (11.2) | 0.45 |

| Hyperlipidemia (n = 3,042) | 60 (74.1) | 1,818 (61.4) | 0.02 | 82 (69.5) | 1,796 (61.4) | 0.08 | 206 (61.7) | 1,672 (61.7) | 0.98 |

| Hypertension (n = 3,042) | 45 (55.6) | 1,571 (53.1) | 0.67 | 62 (52.5) | 1,554 (53.2) | 0.90 | 193 (57.8) | 1,423 (52.6) | 0.07 |

| Any family history of CHD (n = 3,042) | 39 (48.2) | 1,209 (40.8) | 0.19 | 55 (46.6) | 1,193 (40.8) | 0.21 | 135 (40.4) | 1,113 (41.1) | 0.81 |

| Total CAC Agatston score (n = 3,042) | 1,482.8 ± 1,710.7 | 453.4 ± 922.5 | <0.0001 | 1,262.8 ± 1,557.3 | 449.3 ± 920.7 | <0.0001 | 961.7 ± 1,285.0 | 421.5 ± 901.5 | <0.0001 |

| ASCVD risk score (n = 3,042) | 0.35 ± 0.17 | 0.22 ± 0.16 | <0.0001 | 0.36 ± 0.18 | 0.21 ± 0.16 | <0.0001 | 0.34 ± 0.19 | 0.21 ± 0.15 | <0.0001 |

| Total CAC Agatston score (n = 3,042) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 0 | 2 (2.47) | 594 (20.1) | 6 (5.1) | 590 (20.2) | 21 (6.3) | 575 (21.3) | |||

| 1–100 | 10 (12.4) | 910 (30.7) | 18 (15.3) | 902 (30.9) | 61 (18.3) | 859 (31.7) | |||

| 101–400 | 11 (13.7) | 628 (21.2) | 20 (17.0) | 619 (21.2) | 76 (22.8) | 563 (20.8) | |||

| ≥401 | 58 (71.6) | 829 (28.0) | 74 (62.7) | 813 (27.8) | 176 (52.7) | 711 (26.3) | |||

| Total CAC Lesions (n = 1,954) | 16.0 ± 12.8 | 7.8 ± 11.2 | <0.0001 | 14.5 ± 13.0 | 7.7 ± 11.1 | <0.0001 | 12.4 ± 13.7 | 7.4 ± 10.8 | <0.0001 |

| Number of CAC vessels (n = 2,382) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 0 | 1 (1.5) | 554 (23.9) | 4 (4.1) | 551 (24.1) | 19 (7.4) | 536 (25.2) | |||

| 1 | 2 (3.0) | 341 (14.7) | 5 (5.2) | 338 (14.8) | 17 (6.6) | 326 (15.3) | |||

| 2 | 6 (9.1) | 391 (16.9) | 14 (14.4) | 383 (16.8) | 32 (12.5) | 365 (17.2) | |||

| 3 | 24 (36.4) | 634 (27.4) | 33 (34.0) | 625 (27.4) | 93 (36.2) | 565 (26.6) | |||

| 4 | 33 (50.0) | 396 (17.1) | 41 (42.3) | 388 (17.0) | 96 (37.4) | 333 (15.7) | |||

| Total CAC volume (mm3) (n = 1,361) | 1,549.5 ± 1,627.1 | 376.1 ± 749.0 | 0.0005 | 1,202 ± 1,456 | 372.70 ± 746.8 | 0.0003 | 939.6 ± 1,182.2 | 343.8 ± 720.0 | <0.0001 |

| Lesion size (HU/mm3) (total volume score/total lesions) (n = 471) | 45.9 ± 28.3 | 28.4 ± 29.8 | 0.12 | 39.2 ± 36.6 | 28.2 ± 29.5 | 0.14 | 43.2 ± 31.8 | 26.5 ± 28.9 | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD or as n (%). P < 0.05 is statistically significant.

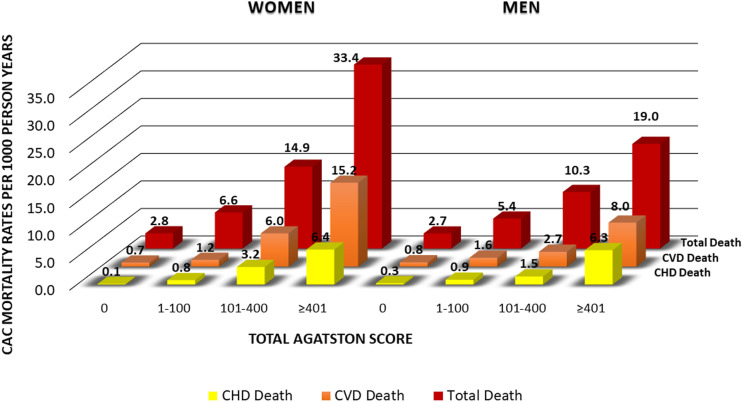

Figure 1 shows total, CVD, and CHD mortality rates per 1,000 person-years according to CAC category among our women and men with diabetes. CAC was absent (score = 0) in 39% of women and in 20% of men; these individuals had mortality rates from CHD and CVD of <1 and total mortality <3 per 1,000 person-years in women and men. However, while scores of >400 were associated with similar rates of CHD mortality in women (6.4) and men (6.3), these levels of CAC were associated with CVD and total mortality rates that were substantially greater in women (15.2 and 33.4, respectively) than in men (8.0 and 19.0, respectively). In addition, intermediate levels of CAC (101–400) were also associated with greater CVD and total mortality rates in women compared with men. Corresponding Kaplan-Meier curves are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Mortality rates (per 1,000 person-years) from CHD, CVD, and all causes by CAC score categories in women and men with diabetes: the CAC Consortium.

Table 3 shows results from Cox proportional hazards regression for the prediction of all-cause, CVD, and CHD mortality after adjustment for clinical variables in men and women separately among those with and without diabetes. In those with diabetes, the nonlinearity assumption was violated for total and CVD mortality but not for CHD mortality; however, the proportionality assumption was not violated for any of the end points. Per log unit of total CAC in the overall sample and in women and men separately, significantly greater risks for total, CVD, and CHD mortality were observed. Among those with diabetes, HRs were lower in men compared with women for total mortality (1.18 and 1.28, respectively; sex interaction P = 0.01) and for CVD death (1.27 and 1.47, respectively; sex interaction P = 0.04), but similar for CHD death (1.48 and 1.48, respectively; sex interaction P = 0.54). A similar pattern held for those without diabetes, although with generally lower HRs, especially for men. In those with diabetes, compared with CAC = 0, the HRs (adjusted for age, sex, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and family history of CHD) associated with CAC 1–100, 101–400, and >400 ranged from 2.4 to 9.0 for CHD death, 1.4 to 3.5 for CVD death, and 1.4 to 2.6 for total death in men and from 2.7 to 9.7 for CHD death, 1.0 to 6.3 for CVD death, and 1.4 to 4.1 for total death in women. An interaction term with sex and CAC categories was again significant for CVD death (P = 0.04) and total death (P = 0.01). A similar pattern held for those without diabetes, with HRs greater for women compared with men with higher levels of CAC (100–399 and ≥400) for total and CVD, but not CHD mortality. The magnitude of the differences between women and men, however, was notably lower than in those with diabetes. Higher levels of CAC also predicted non-CVD mortality, with HRs generally higher in those with diabetes than in those without diabetes, although there were no significant interactions by sex. Three-way tests of interaction (examining whether the difference in HRs between men and women were significantly different between those with and without diabetes) were not significant for any of the end points.

Table 3.

Adjusted Cox regression for CAC score with CHD, CVD, non-CVD, and total mortality in women and men with and without diabetes

| No diabetes | Diabetes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 41,591) | Women (n = 20,542) | Men (n = 3,042) | Women (n = 1,461) | |||||

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Total mortality | ||||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score | 1.12 (1.10–1.15) | <0.0001 | 1.15 (1.12–1.18) | <0.0001 | 1.18 (1.12–1.25) | <0.0001 | 1.28 (1.19–1.38) | <0.0001 |

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) P = 0.03 | 0.89 (0.82–0.97) P = 0.01 | ||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) P = 0.59 | |||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score | ||||||||

| 0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | ||||

| 1–100 | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 0.34 | 1.31 (1.10–1.57) | 0.003 | 1.36 (0.83–2.24) | 0.23 | 1.43 (0.81–2.56) | 0.22 |

| 101–400 | 1.39 (1.18–1.63) | <0.0001 | 1.73 (1.41–2.13) | <0.0001 | 1.88 (1.15–3.09) | 0.01 | 2.56 (1.45–4.53) | 0.001 |

| ≥401 | 2.03 (1.74–2.38) | <0.0001 | 2.84 (2.29–3.52) | <0.0001 | 2.61 (1.61–4.24) | <0.0001 | 4.05 (2.33–7.04) | <0.0001 |

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) P = 0.0004 | 0.79 (0.65–0.95) P = 0.01 | ||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 0.95 (0.89–1.03) P = 0.20 | |||||||

| CVD mortality | ||||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score | 1.23 (1.18–1.29) | <0.0001 | 1.25 (1.18–1.33) | <0.0001 | 1.27 (1.14–1.41) | <0.0001 | 1.47 (1.27–1.71) | <0.0001 |

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 0.92 (0.87–0.98) P = 0.006 | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) P = 0.04 | ||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) P = 0.16 | |||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score | ||||||||

| 0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | ||||

| 1–100 | 1.22 (0.89–1.66) | 0.22 | 1.51 (1.02–2.25) | 0.04 | 1.36 (0.54–3.45) | 0.52 | 0.96 (0.29–3.21) | 0.95 |

| 101–400 | 1.85 (1.35–2.54) | 0.0001 | 2.54 (1.67–3.85) | <0.0001 | 1.63 (0.64–4.14) | 0.30 | 3.67 (1.30–10.38) | 0.01 |

| ≥401 | 3.25 (2.40–4.40) | <0.0001 | 4.57 (3.03–6.91) | <0.0001 | 3.48 (1.44–8.37) | 0.005 | 6.27 (2.27–17.28) | 0.0004 |

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 0.79 (0.70–0.90) P = 0.0003 | 0.71 (0.51–0.99) P = 0.04 | ||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 0.90 (0.80–1.01) P = 0.08 | |||||||

| CHD mortality | ||||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score | 1.32 (1.25–1.41) | <0.0001 | 1.29 (1.17–1.41) | <0.0001 | 1.48 (1.28–1.71) | <0.0001 | 1.48 (1.18–1.85) | 0.0007 |

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 0.96 (0.87–1.05) P = 0.32 | 0.92 (0.72–1.19) P = 0.54 | ||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) P = 0.93 | |||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score | ||||||||

| 0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | ||||

| 1–100 | 1.42 (0.90–2.23) | 0.13 | 1.03 (0.54–1.98) | 0.93 | 2.38 (0.52–10.91) | 0.27 | 2.66 (0.29–24.30) | 0.39 |

| 101–400 | 2.52 (1.60–3.95) | <0.0001 | 2.27 (1.20–4.31) | 0.01 | 2.91 (0.63–13.35) | 0.17 | 7.79 (0.95–63.82) | 0.06 |

| ≥401 | 4.51 (2.91–7.00) | <0.0001 | 4.99 (2.72–9.16) | <0.0001 | 8.99 (2.11–38.34) | 0.003 | 9.65 (1.18–79.20) | 0.04 |

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) P = 0.04 | 0.92 (0.56–1.52) P = 0.74 | ||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 0.98 (0.84–1.16) P = 0.84 | |||||||

| Non-CVD Mortality | ||||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) | <0.0001 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 0.0004 | 1.15 (1.07–1.23) | <0.0001 | 1.17 (1.07–1.28) | 0.0008 |

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) P = 0.84 | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) P = 0.37 | ||||||

| Log total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) P = 0.14 | |||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score | ||||||||

| 0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | Reference = 1.0 | ||||

| 1–100 | 1.11 (0.94–1.33) | 0.23 | 1.25 (1.02–1.53) | 0.03 | 1.64 (0.90–2.98) | 0.10 | 1.85 (0.96–3.60) | 0.07 |

| 101–400 | 1.22 (1.01–1.47) | 0.04 | 1.39 (1.09–1.78) | 0.009 | 2.46 (1.36–4.44) | 0.003 | 1.57 (0.78–3.19) | 0.21 |

| ≥401 | 1.56 (1.29–1.88) | <0.0001 | 1.49 (1.13–1.97) | 0.004 | 2.54 (1.43–4.53) | 0.002 | 2.96 (1.50–5.84) | 0.002 |

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex interaction term | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) P = 0.91 | 0.92 (0.72–1.61) P = 0.47 | ||||||

| Total CAC Agatston score by sex by diabetes interaction term | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) P = 0.27 | |||||||

P < 0.05 is statistically significant. Estimates adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, family history, and smoking. Bonferroni corrected P < 0.017. Uncensored (deaths) of CHD total 524, CHD with diabetes total 107, CVD total 971, CVD with diabetes total 175, total deaths total 3,158, total death with diabetes total 490, non-CVD total 2,187, non-CVD with diabetes total 315.

Further analysis examined whether diabetes was a stronger predictor of our mortality end points in women compared with men and whether CAC might explain this. The strength of diabetes as a risk factor for total, CVD, and CHD mortality was only slightly higher in women compared with men. Adjusted HRs and 95% CIs were 1.81 (1.53–2.16), 2.14 (1.59–2.89), and 2.29 (1.48–3.56), respectively, in women and 1.73 (1.53–1.94), 1.82 (1.49–2.23), and 2.20 (1.72–2.82), respectively, in men. Further adjustment for log(CAC+1) attenuated these HRs to 1.62 (1.36–1.93), 1.78 (1.33–2.39), and 1.68 (1.21–2.93), respectively, in women and to 1.60 (1.42–1.81), 1.60 (1.31–1.97), and 1.86 (1.45–2.39), respectively, in men. Interaction terms of diabetes and sex were not significant for either end point.

We also performed Cox regression examining HRs for total, CVD, and CHD mortality comparing women and men (Supplementary Table). Those with CAC scores of 0 and 1–100 show no difference comparing women and men, but increased HRs were seen for women versus men in those with CAC scores of 101–400 and >400 for both CVD and total mortality (P < 0.05, except P = 0.08 for total mortality for those with scores of 101–400). Also, HRs for CVD mortality were significantly greater for women versus men in those who were above the median for calcium volume and lesion size and were borderline significant (P = 0.05) for those with three or more calcified vessels.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates, in the largest cohort of subjects with diabetes investigating CAC and long-term mortality outcomes, a strong relation of CAC score as well as number of calcified lesions and vessels with CHD, CVD, and total mortality. We importantly show CAC to be a stronger predictor of CVD and total mortality in women compared with men when analyzed both continuously (natural log-transformed CAC score) and categorically with scores of 101–400 and >400. In addition, we confirm the findings of prior studies that diabetes is not necessarily a CHD risk equivalent (5,7–9). Thirty-nine percent of women and 20% of men had CAC scores of 0, with associated CHD and CVD mortality rates of <1 per 1,000 person-years.

In those with CAC scores >100, higher greater absolute and relative risks for total and CVD mortality are seen in women than in men, emphasizing the greater association of moderate and extensive levels of CAC in women compared with men with CVD and total mortality. While for men scores of 101–400 and >400 were associated with CVD death rates of 2.7 and 8.0 per 1,000 person-years, the corresponding values for women were 6.0 and 15.2. Moreover, for total deaths, rates for CAC scores of 101–400 and >400 were 10.3 and 19.0, respectively, for men, but 14.9 and 33.4, respectively, for women. This indicates women with diabetes who have more advanced subclinical atherosclerosis (e.g., CAC scores of ≥100) are at both higher relative as well as absolute risks for mortality from CVD and all-causes compared with men.

Our results suggest CAC screening in those with diabetes may be able to discriminate risk better in women compared with men, given the greater differences in absolute risk identified across CAC categories; however, it should be noted that moderate-significant levels of CAC (scores of >100) were also less common in women compared with men with diabetes (32% vs. 50%, respectively, in our sample). Nevertheless, this still represents a high proportion of women with diabetes at increased risk for CVD or all-cause mortality. Conversely, nearly 40% of women but only 20% of men had a CAC score of 0, representing very low annual mortality rates of <1%, a significant survival “warranty.”

Shaw et al. (14) showed in the overall CAC consortium cohort that CAC scores of 101–399 and ≥400 also predicted CVD mortality more strongly in women compared with men. They also showed higher HRs for CVD mortality in women compared with men with multiple-vessel CAC and in those with greater CAC volume. Women with larger CAC lesions also had greater CVD mortality rates. Our findings in those with diabetes are consistent, where the HRs for CVD mortality were greater in women versus men among those who had three to four calcified vessels (P = 0.06) and greater (above the median) CAC volume and lesion sizes (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001).

Our greater risks for CVD and total mortality conferred by CAC in women compared with men with diabetes provide support for prior studies showing diabetes to be a stronger risk factor for CVD and total mortality in women compared with men (12,13). Moreover, global statistics show diabetes to be related to more deaths globally in women (813,025 or 3.1% of all deaths in women compared with 684,346 or 2.3% of all deaths in men) (17). Some have noted greater differences in risk factor prevalence in those with versus without diabetes in women compared with men, such as poorer risk factor control in women, as well as differences in sex hormones that may help explain the greater CVD risks in women conferred by diabetes (18). Our study, however, is the first to show sex differences in diabetes patients in the magnitude of risk of CVD or total mortality by the level of CAC. Women with CAC scores of >100 have greater CVD and total mortality risks than do men with the same CAC scores.

The initial (19) and more recent 10-year follow-up (9) of the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort both show the importance of CAC as a predictor of ASCVD events beyond risk factors in middle-aged adults as well as long-term warranty associated with a 0 calcium score. We show in the current study that CHD and CVD mortality rates are both <1% per year in those subjects with diabetes with a 0 score, which was found in 20% of men and nearly 40% of women in our diabetes cohort. We show more than a 10-fold variation in CHD and CVD mortality rates by CAC score in our cohort of diabetes subjects, indicating great heterogeneity of risk in those with diabetes. This closely parallels results previously observed for CHD and CVD events among subjects with diabetes across CAC score categories in the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (5), with a more recent report indicating poorer glycemic control and long diabetes duration associated with worse outcomes at each level of CAC (8). Analysis of the Diabetes Heart Study (20) has shown that CAC in people with diabetes provides further improvement in the C statistic and net reclassification improvement over the Framingham risk score for the prediction of cardiovascular mortality over 7.4 years. Our study is the first to evaluate sex differences in these relationships with mortality end points in patients with diabetes.

The recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Multisociety Cholesterol Guidelines (21) had noted the use of CAC as a risk stratifier after consideration of other “risk-enhancing” factors, with CAC scores ≥100 an impetus for use of a high-intensity statin. These scores are consistent with our earlier observations for CHD and CVD event risk being increased in people with diabetes in MESA (5). With women being less likely than men to fill statin prescriptions (22), our current observation of their even higher event rates than men when diabetes is accompanied by higher CAC scores may help identify those needing more intensive risk factor intervention, with the hopes of diminishing this gap in care.

Our study has important strengths and limitations. The large sample size across several geographic regions and standardized and largely complete ascertainment of mortality follow-up are important strengths. The diabetes diagnosis was based on treatment with oral hypoglycemic drugs or insulin; thus, those who may have had undiagnosed diabetes would not have been included in our study. Limitations include the reliance of self-reported risk factor information for most analyses, with actual risk factor measurements available in only a subset of participants. Importantly, we did not have information on glycated hemoglobin, duration of diabetes, and other diabetes-specific measures of severity that could potentially offer further insight into our findings. Moreover, information on the number of CAC lesions, volume score, and lesion size were only available in a subset of subjects, limiting statistical power for examining relationships of some of these measures with outcomes in our diabetes cohort. Our cohort being predominantly White (75%), with few events in non-White individuals, precluded us from doing ethnic-specific analyses. Moreover, with coronary calcium scans being physician referred and clinically indicated for cardiovascular risk stratification, as opposed to self-referrals, while more real-world, can also result in our cohort not being fully representative of the general population of people with diabetes. Our sample of subjects with diabetes, compared with a recently published representative sample of U.S. subjects with diabetes without prior CVD, shows age to be comparable (58.7 vs. 58.1 years), but male sex to be more common (67.6% vs. 50.6%) and White ethnicity to be more common (75.4% vs. 60.5%) (23). However, compared with subjects with diabetes in the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, the prevalence of dyslipidemia (62% vs. 61%), hypertension (56% vs. 66%), and smoking (11% vs. 13%) was similar, but our cohort had a greater prevalence of higher CAC scores (44% vs. 20% with scores >100) (5).

In conclusion, we show that while CAC predicts CHD, CVD, and total mortality in adults with diabetes overall, it is a stronger predictor of CVD and total mortality in women compared with men, with CAC scores of >100 having greater absolute and relative risks for CVD and total mortality rates in women. This may help alert the clinician about the greater seriousness of diabetes in a woman if accompanied by a high CAC score. Given that awareness about extent of CVD in women remains underappreciated, our study contributes to increasing the importance of the clinician-patient risk discussion regarding risk factor modification efforts aimed to optimize the prevention of CVD events in women with diabetes.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the participants of the Coronary Calcium Consortium.

Funding. M.J.Bl. was supported by research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.

Duality of Interest. N.D.W. discloses research funding not related to the current manuscript from Amarin, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Novartis and serves on the speakers bureau for Amarin and Sanofi. M.J.Bu. discloses research grant support not related to the current manuscript from General Electric. M.J.Bl. discloses research funding from Aetna and Amgen and honoraria from Amgen, Sanofi, Regeneron, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Akcea, 89Bio, Zogenix, Tricida, and Gilead. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. N.D.W., A.R.C.H., and D.S.B. wrote the manuscript and provided critical revision and feedback. A.R.C.H. also conducted the analysis. A.R., L.J.S., S.P.W., M.J.Bu., K.N., M.D.M., J.R., and M.J.Bl. provided critical review and editorial suggestions. D.S.B. takes full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, access to the data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript. D.S.B. is the guarantor of the study and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Anaheim, CA, 11–15 November 2017.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.12691940.

N.D.W. and A.R.C.H. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2018. Accessed 11 November 2018. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html

- 2.Malik S, Wong ND, Franklin SS, et al. Impact of the metabolic syndrome on mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in United States adults. Circulation 2004;110:1245–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong ND, Sciammarella MG, Polk D, et al. The metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and subclinical atherosclerosis assessed by coronary calcium. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1547–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoff JA, Quinn L, Sevrukov A, et al. The prevalence of coronary artery calcium among diabetic individuals without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1008–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik S, Budoff MJ, Katz R, et al. Impact of subclinical atherosclerosis on cardiovascular disease events in individuals with metabolic syndrome and diabetes: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2285–2290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M Jr., Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;15:827–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkeles RS, Godsland IF, Feher MD, et al.; PREDICT Study Group . Coronary calcium measurement improves prediction of cardiovascular events in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes: the PREDICT study. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2244–2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raggi P, Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Callister TQ. Prognostic value of coronary artery calcium screening in subjects with and without diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1663–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik S, Zhao Y, Budoff M, et al. Coronary artery calcium score for long-term risk classification in individuals with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:1332–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rana JS, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Jaffe M, Karter AJ. Diabetes and prior coronary heart disease are not necessarily risk equivalent for future coronary heart disease events. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:387–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulugahapitiya U, Siyambalapitiya S, Sithole J, Idris I. Is diabetes a coronary risk equivalent? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2009;26:142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. JAMA 1979;241:2035–2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roche MM, Wang PP. Sex differences in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, hospitalization for individuals with and without diabetes, and patients with diabetes diagnosed early and late. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2582–2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw LJ, Min JK, Nasir K, et al. Sex differences in calcified plaque and long-term cardiovascular mortality: observations from the CAC Consortium. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3727–3735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaha MJ, Whelton SP, Al Rifai M, et al. Rationale and design of the coronary artery calcium consortium: a multicenter cohort study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017;11:54–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd-Jones DM, Braun LT, Ndumele CE, et al. Use of risk assessment tools to guide decision-making in the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a special report from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation 2019;139:e1162–e1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . WHO estimates for 2000–2012. Accessed 13 January 2020. Available from https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html

- 18.Recarti C, Sep SJ, Stehouwer CD, Unger T. Excess cardiovascular risk in diabetic women: a case for intensive treatment. Curr Hypertens Rep 2015;17:554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1336–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal S, Cox AJ, Herrington DM, et al. Coronary calcium score predicts cardiovascular mortality in diabetes: Diabetes Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:972–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation 2019;139:e1182–e1186]. Circulation 2019;139:e1082–e114330586774 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volgman AS, Dembowski E, Braun LT. Should sex matter when it comes to high-intensity statins? J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1738–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andary R, Fan W, Wong ND. Control of cardiovascular risk factors among US adults with type 2 diabetes with and without cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2019;124:522–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]