Abstract

We report COVID-19 multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in an adult patient with an atypical presentation (mild abdominal pain) and a negative (repeated) reverse transcriptase-PCR, in the absence of lung involvement on lung ultrasound. In this case, focused cardiac ultrasound revealed signs of myopericarditis and enabled us to focus on the problem that was putting our patient in a perilous situation, with a quick, non-time-consuming and easy-to-access technique. Serology test was performed and SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed more than a week after admission to the coronary unit. As the patient had a general good appearance, the potential implications of missing this diagnosis could have been fatal.

Keywords: infectious diseases, ultrasonography, TB and other respiratory infections, cardiovascular medicine

Background

Eight months after the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic, the scientific community continues to detail its varied clinical presentations. Clinical features have predominantly been respiratory tract symptoms including cough, fever, fatigue and pneumonia. Worst case scenarios could evolve into acute respiratory distress syndrome.1 However, COVID-19 has proven to be most diverse, with a wide scope of extrapulmonary sets of symptoms.2

As we start to elucidate the different symptomatic patterns which COVID-19 can produce, recent reports describe the concurrence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, dermatological and neurological symptoms without respiratory illness, compatible with a multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A),3–5 resembling the multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children that has been described since the beginning of the pandemic.6 7

Case presentation

The present report describes a probable case of MIS-A in a patient suspected to be affected by COVID-19.

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old white man without medical history and no prescribed medications presented to the emergency department (ED) with diffuse abdominal pain and nausea for the past 24 hours. He described fever (up to 38°C), fatigue, orthopnoea, anosmia and sore throat the week before, which he had treated with over-the-counter acetaminophen and oral hydration. He denied vomiting, chest pain or any other symptoms.

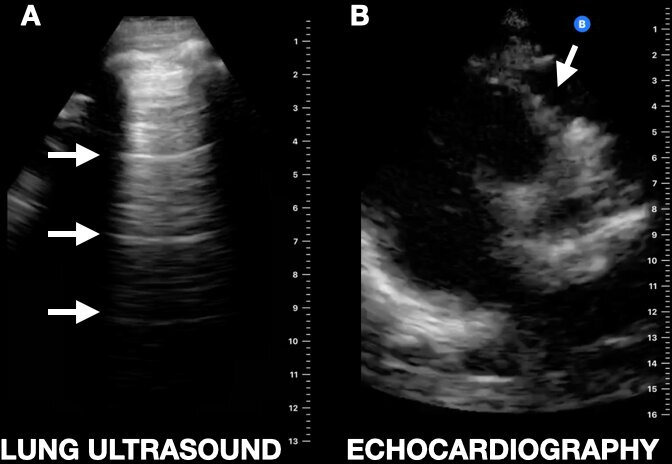

On arrival, physical examination revealed blood pressure of 109/66 mm Hg, heart rate of 86 beats per minute, oxygen saturation of 98% while breathing ambient air and body temperature of 36.9°C. Physical examination was completed with a focused cardiac and lung ultrasound assessment, which showed normal left and right ventricular dimensions, severe global hypokinesis and moderate-severe left ventricle (LV) dysfunction. There was a small pericardial effusion without signs of cardiac tamponade. Lung ultrasound showed a physiological A-line pattern (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lung ultrasound performed with a hand-held ultrasound device revealing normal lung A-lines reverberation artefact (white arrows) (A). Parasternal long axis of the heart showing a pericardial effusion (white arrow) (B).

Based on clinical history and due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we performed chest CT, which showed no abnormalities.

Blood test was remarkable for lymphopaenia (0.43×10e9/L, normal value (NV): 1.00–4.80) and elevated fibrinogen (>1200 mg/dL, NV: 150–450). In view of these results and the sonography findings, high-sensitivity troponin T (hs-TnI) and N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) were ordered, displaying increased levels of myocyte necrosis markers (hs-TnI 6182.1 ng/mL, NV: 0.0–53.5; NT-proBNP 1340 pg/mL, NV: 0–125) and C reactive protein of 337.1 mg/L (NV: 0.0–5.0). A 12-lead ECG showed sinus tachycardia with no other abnormalities. QTc was normal. Chest X-ray was unremarkable.

Based on clinical history and due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a nasopharyngeal swab on real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR assay (RT-PCR) was performed showing a negative result for SARS-CoV-2.

Treatment

Despite all negative imaging and blood test results for COVID-19, we maintained a high level of suspicion as a result of the extremely high local transmission of COVID-19 in the area (Madrid, Spain), so he was provisionally classified as a high-risk patient for COVID-19.

He was treated with empirical antibiotics (amoxicillin clavulanate 2 g/8 hours), acetaminophen (1 g/8 hours), glucose and saline solution. Beta blockers and ACE inhibitors were contraindicated due to the low systolic arterial pressure.

Outcome and follow-up

Shortly after his arrival to the ED, the patient’s condition worsened, becoming hypotensive (systolic pressure less than 90 mm Hg) and losing consciousness.

We transferred him to the COVID-19 coronary unit with a diagnosis of acute myopericarditis. At his arrival, he remained hypotensive, requiring inotropic support (norepinephrine and milrinone) and diuretics (furosemide 40 mg/day, spironolactone 50 mg/day), together with empirical antimicrobial treatment (piperacillin tazobactam 4 g/6 hours, ganciclovir 300 mg/12 hours), fluids and analgesics. Despite the high suspicion, off-label COVID-19 treatment was not administered since there was no positive result on RT-PCR and no abnormal chest CT was observed.

During his stay in the COVID-19 coronary unit, comprehensive echocardiography revealed normal LV dimensions, severe global hypokinesis and severe LV dysfunction (29.7%).

COVID-19 antibody testing was positive for IgM and IgG. Search for other common cardiotropic infectious micro-organisms (Cytomegalovirus, HIV, Eptein-Barr virus, Coxiella burnetii, measles morbillivirus, varicella zoster virus, mumps orthorubulavirus, rubella virus, herpes simplex, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Rickettsia conorii) yielded negative results.

After 5 days, his condition stabilised and he was able to reduce and finally withdraw from inotropic support. After 8 days, focused cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS) reported significant improvement in LV function.

At the time of submission, the patient remained hospitalised in the COVID-19 coronary unit with progressive clinical and haemodynamic improvement.

Discussion

This case illustrates why myocardial events and complications should be searched for in patients with COVID-19,8 in order to identify potential cases of MIS-A, which might affect patients beyond the paediatric age.5 As previously reported in adults, this complication might occur several weeks after a symptomatic or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, which reinforces the notion that MIS-A might be a hyperinflammatory and immune-mediated systemic response that causes cardiac damage. This would explain the finding of a negative RT-PCR (but positive serology) and the lack of lung infiltrates or skin lesions.

Patients should be closely monitored for any haemodynamic changes as their condition can turn critical in a very short period of time. In our case, FoCUS was paramount. It enabled us to focus on the problem that was putting our patient in a perilous situation, with a quick, non-time-consuming and easy-to-access technique. Treatment of myopericarditis within MIS-A caused by SARS-CoV-2 did not differ from any other viral myopericarditis.9

New triage algorithms have been developed, many of which do not include a comprehensive physical examination.10

This case ratifies the crucial importance of completing such a thorough examination, including FoCUS and lung ultrasound,11 in patients as they may initially present with unrelated symptoms.

Due to these reasons and the high incidence of COVID-19 infection, further research should be conducted and clinicians should maintain a very high level of suspicion as it would not be rare to start identifying more MIS-A cases within COVID-19.

Learning points.

SARS-CoV-2 acute myopericarditis and multisystem inflammatory syndrome can occur in the absence of lung involvement in patients presenting with vague symptoms and negative reverse transcriptase-PCR.

Focused cardiac ultrasound should be considered as part of physical examination of patients with COVID-19 as it might reveal signs of myopericarditis and raise suspicion for a multisystem inflammatory syndrome and cardiac damage.

We propose an easy-to-complete, extended physical examination including cardiac, vein and lung ultrasound of these patients, which might allow early identification of this potentially fatal disease.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to this work. Conception and design: YT-C. Data collection: YT-C, AAM. Writing the article: SRR, ADdS. Critical revision of the article: YT-C, AAM, ADdS, SRR. Final approval of the article: YT-C, AAM, SRR, ADdS. Overall responsibility: YT-C, AAM.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:819. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020;26:1017–32. 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chau VQ, Giustino G, Mahmood K, et al. Cardiogenic shock and hyperinflammatory syndrome in young males with COVID-19. Circ Heart Fail 2020;13:e007485. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris SB, Schwartz NG, Patel P, et al. Case Series of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection - United Kingdom and United States, March-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1450–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hékimian G, Kerneis M, Zeitouni M, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 acute myocarditis and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adult intensive and cardiac care units. Chest 2021;159:657–62. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC . Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Available: https://www.cdc.gov/mis-c/cases/index.html [Accessed 6 Mar 2021].

- 7.Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2020;383:334–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu C-M, Wong RS-M, Wu EB, et al. Cardiovascular complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:140–4. 10.1136/pgmj.2005.037515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu PP, Mason JW. Advances in the understanding of myocarditis. Circulation 2001;104:1076–82. 10.1161/hc3401.095198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Zhou L, Yang Y, et al. Therapeutic and triage strategies for 2019 novel coronavirus disease in fever clinics. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:e11–12. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30071-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu RB, Tayal VS, Panebianco NL, et al. Ultrasound on the Frontlines of COVID-19: report from an international Webinar. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:523–6. 10.1111/acem.14004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]