Summary

Nitrogen‐fixing rhizobia and legumes have developed complex mutualistic mechanism that allows to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Signalling by mitogen‐activated protein kinases (MAPKs) seems to be involved in this symbiotic interaction. Previously, we reported that stress‐induced MAPK (SIMK) shows predominantly nuclear localization in alfalfa root epidermal cells. Nevertheless, SIMK is activated and relocalized to the tips of growing root hairs during their development. SIMK kinase (SIMKK) is a well‐known upstream activator of SIMK. Here, we characterized production parameters of transgenic alfalfa plants with genetically manipulated SIMK after infection with Sinorhizobium meliloti. SIMKK RNAi lines, causing strong downregulation of both SIMKK and SIMK, showed reduced root hair growth and lower capacity to form infection threads and nodules. In contrast, constitutive overexpression of GFP‐tagged SIMK promoted root hair growth as well as infection thread and nodule clustering. Moreover, SIMKK and SIMK downregulation led to decrease, while overexpression of GFP‐tagged SIMK led to increase of biomass in above‐ground part of plants. These data suggest that genetic manipulations causing downregulation or overexpression of SIMK affect root hair, nodule and shoot formation patterns in alfalfa, and point to the new biotechnological potential of this MAPK.

Keywords: Medicago sativa , SIMK, SIMKK, root hair, infection thread, nodule

Introduction

Medicago sativa L., commonly known as alfalfa or ‘lucerne’, is the world’s leading forage legume and a low‐input bioenergy crop (Aung et al., 2015). The genus Medicago includes both perennial and annual species. Perennial legumes have important roles in providing cheap and widespread forages of high nutritive value, in soil protection, or improvement of nitrogen‐limited soils (Radović et al., 2009). Due to variable genetic origin, alfalfa can adapt to different environmental conditions (Radović et al., 2003).

Mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways represent universal signalling modules in eukaryotes, including yeasts, animals and plants (Ichimura et al., 2000; Šamajová et al., 2013a). A typical MAPK cascade is organized into three‐tiered module composed of MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK), MAPK kinase (MAPKK) and MAPK (Cristina et al., 2010). MAPKs are phosphorylated and thereby activated by MAPKKs via dual phosphorylation of conserved threonine and tyrosine residues at a TXY motif. MAPKKs themselves are activated by MAPKKKs through phosphorylation of two serine/threonine residues in the S/T‐X3‐5‐S/T motif (Chen et al., 2017; Jonak et al., 2002). Signalling through MAPK cascades can regulate various cellular and developmental processes (Komis et al., 2018; Šamajová et al., 2013a). MAPKs phosphorylate and regulate broad range of substrates such as other protein kinases, nuclear transcription factors, cytoskeletal components and proteins involved in metabolism and vesicular trafficking (Šamajová et al., 2013b; Smékalová et al., 2014). Plant MAPKs can be activated by several abiotic stimuli such as cold, drought or salinity (Ovečka et al., 2014; Šamajová et al., 2013a; Sinha et al., 2011) and biotic stimuli such as pathogens, pathogen‐derived toxins or generally by microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs; Pitzschke et al., 2009; Rasmussen et al., 2012).

In alfalfa, stress‐induced MAPK (SIMK) was identified as a salt stress‐ and elicitor‐induced MAPK (Cardinale et al., 2000, 2002; Munnik et al., 1999). Yeast two‐hybrid screen and activation studies identified SIMK kinase (SIMKK) as an upstream activator of SIMK (Cardinale et al., 2002; Kiegerl et al., 2000). Interaction between SIMK and SIMKK upon salt stress is quite specific, because no interaction was observed with three other MAPKs, such as MMK2 (Jonak et al., 1995), MMK3 (Bögre et al., 1999) and SAMK (Jonak et al., 1996). SIMKK is a functional dual‐specificity protein kinase that phosphorylates SIMK on both threonine and tyrosine residues of the activation loop (Cardinale et al., 2002; Kiegerl et al., 2000). Previously, we have shown that SIMK predominantly localizes in nuclei while it is activated and redistributed from nucleus into growing root hair tips (Šamaj et al., 2002). In latrunculin B‐treated root hairs, SIMK relocated back to the nucleus while after jasplakinolide treatment, SIMK colocalized with thick F‐actin cables in the cytoplasm. Thus, these drugs affecting actin cytoskeleton (Baluška et al., 2000b; Bubb et al., 2000) have a direct impact on the intracellular localization of SIMK (Šamaj et al., 2002).

Legumes are able to perform symbiotic interactions with nitrogen‐fixing soil bacteria collectively called rhizobia (e.g. Bradyrhizobium or Sinorhizobium) which can reduce atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) into ammonium (NH3) in specialized organs, the so‐called root nodules (Carro et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). This type of symbiosis plays an essential role in both agronomical and natural systems (Geurts et al., 2016; Oldroyd et al., 2011; Ryu et al., 2017). It begins with a signal exchange between rhizobia and its host plant (Oldroyd et al., 2013). Flavonoid compounds released by legumes represent the signal for bacteria to produce nodulation (Nod) factors. Nod factors are lipochitooligosaccharides (LCOs) that, together with rhizobia, induce specific responses required for nodulation process in legume host plants. Nod factors are responsible for the establishment of pre‐infection thread structures, while Nod factors together with rhizobia are directly involved in the formation of infection threads (ITs), thin tubular structures filled with rhizobia and penetrating several root cell layers towards target cells in newly developing nodules (van Brussel et al., 1992; Jones et al., 2007; Perret et al., 2000; Remigi et al., 2016). Rhizobia released from ITs, enfolded by a membrane of plant origin, are transformed into bacteroids that are able to fix nitrogen (Jones et al., 2007; Oldroyd et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018). Negative and positive regulatory pathways control the number of nodules on the legume root system (Caetano‐Anollés and Bauer, 1988). Plant hormones linked to stress and defence responses, such as salicylic acid (SA), abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonate (JA) and ethylene, are negative regulators of Nod factor signalling (Roy et al., 2020; Ryu et al., 2012). Moreover, these hormones are also common activators of MAPK cascades in various plants (Cristina et al., 2010; Ryu et al., 2017). Upon infection, rhizobia activate MAPK cascade and stress‐related responses early during infection (Lopez‐Gomez et al., 2012).

In this study, we generated stable transgenic alfalfa plants overexpressing GFP‐tagged SIMK. These plant lines with overexpressed and activated GFP‐SIMK showed longer root hairs, more ITs, clustered nodules and increase in above‐ground biomass production. In addition, we employed SIMKK RNAi lines showing downregulation of both SIMKK and SIMK accompanied by shorter root hairs, less ITs and nodules, and lower biomass of above‐ground plant parts. These data suggest that genetic manipulation of SIMK affects root hair, IT, nodule and biomass production in alfalfa.

Results

SIMK‐dependent root hair phenotypes

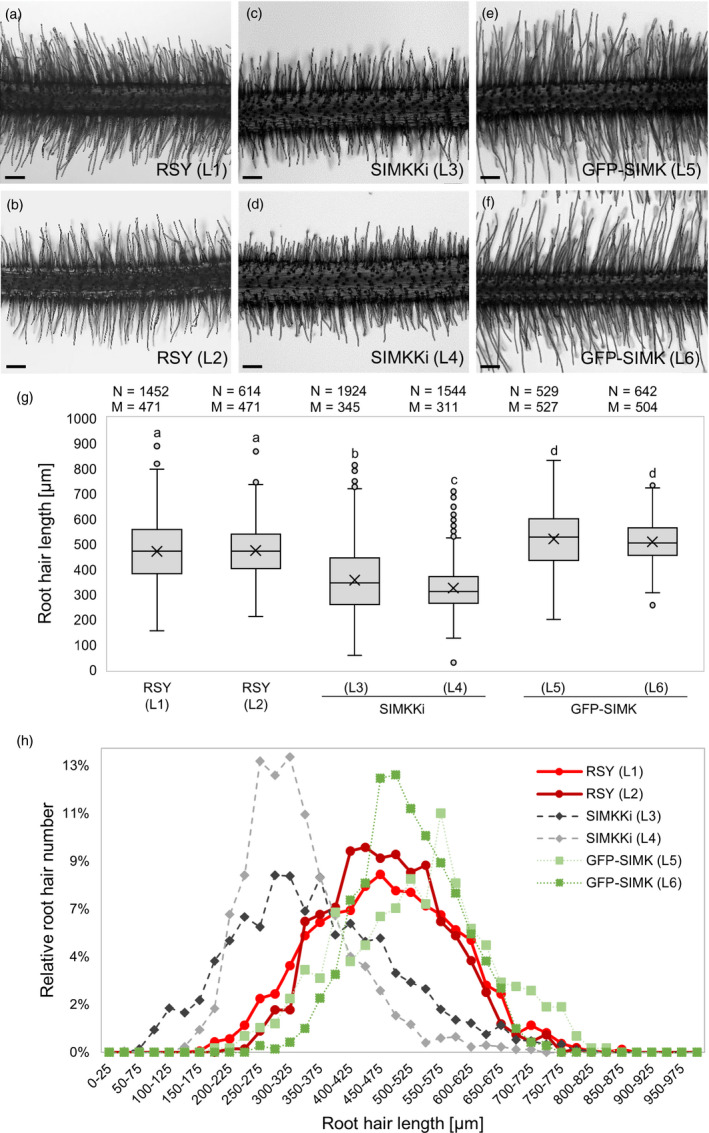

Root hair phenotypes were examined in stable transformed alfalfa lines with downregulated or upregulated SIMK, using SIMKK RNAi or overexpression (both under constitutive 35S promoter) approaches, respectively. For evaluation of root hair growth efficiency, the appropriate parameter of root hair length in mature parts of the root was measured in these lines. In control wild‐type plants, root hair length median value in both analyzed lines (RSY, lines L1 and L2) was 471 µm (Figure 1a,b,g). In transgenic lines carrying SIMKK RNAi construct (annotated as SIMKKi, lines L3 and L4), showing strong downregulation of SIMKK and SIMK transcripts (Figure 2a) and SIMK protein (Figure 2b,d), root hair length median decreased to 345 µm and 311 µm, respectively (Figure 1c,d,g). In contrast, transgenic lines overexpressing 35S::GFP:SIMK in wild‐type RSY background (annotated as GFP‐SIMK, lines L5 and L6) showed an increase of root hair length median to 527 µm and 504 µm, respectively (Figure 1e,f,g). Root hair phenotypes of alfalfa lines presented in the form of contingency graph with 25 µm intervals (Figure 1h) showed a relative root hair number (%) found within each root hair length interval. In SIMKKi lines (L3, L4), the root hair distribution pattern was shifted to the left (Figure 1h) in comparison with RSY (L1, L2), which means an earlier cessation of root hair tip growth. In contrast, the distribution of root hairs in GFP‐SIMK lines (L5, L6) was shifted to the right while distribution curves showed higher values in the range of longer root hairs (Figure 1h), which means later cessation of the tip growth and higher proportion of longer root hairs.

Figure 1.

Root hair phenotypes in alfalfa RSY, SIMKK RNAi (SIMKKi) lines and lines overexpressing GFP‐SIMK. (a,b) Representative images of root hair phenotypes of plants from two independent lines (L1, L2) of control wild‐type RSY, (c,d) two independent transgenic lines with SIMKK RNAi construct (SIMKKi L3, L4) and (e,f) two independent transgenic lines expressing 35S::GFP:SIMK in wild‐type RSY background (GFP‐SIMK L5, L6). (g) Box plot graph depicting comparison in root hair length in indicated lines, number of observations N and median value M. Statistics was calculated in SigmaPlot11.0 using Kruskal–Wallis one‐way analysis of variance on ranks (Dunn's method) and is based on N = 529–1924. The numbers of root hairs observed were 1452 (RSY L1), 614 (RSY L2), 1924 (SIMKKi L3), 1544 (SIMKKi L4), 529 (GFP‐SIMK L5) and 642 (GFP‐SIMK L6). Different lower case letters indicate statistical significance between treatments (P < 0.05). (h) Relative distribution of root hair lengths in indicated alfalfa lines. Normalized root hair number was evaluated using 25 µm intervals distribution. Transgenic lines show different distribution pattern of root hair lengths as compared to RSY wild‐type lines. Scale bar: (a–f) 200 µm.

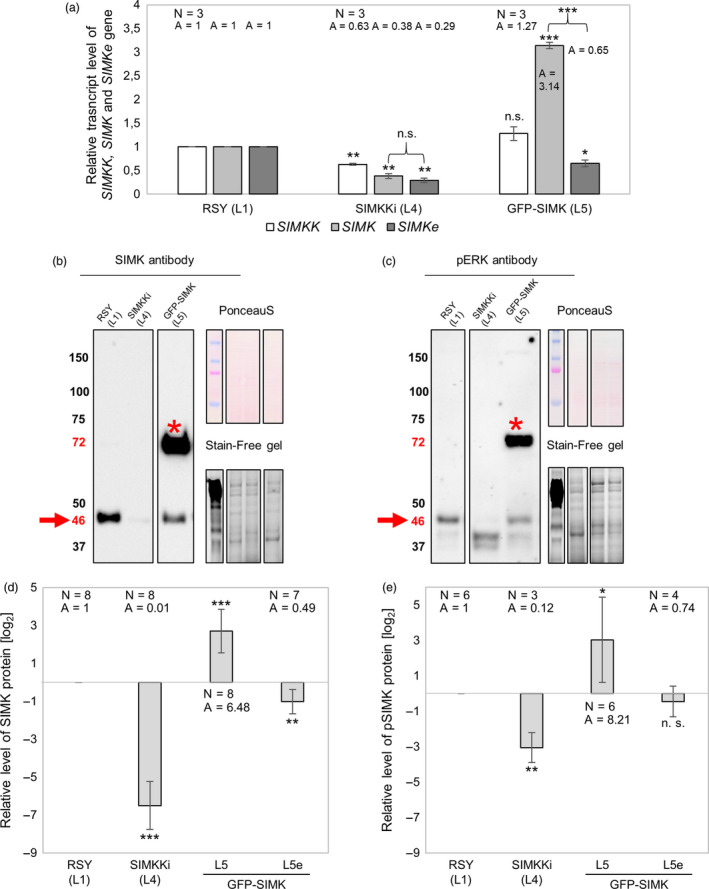

Figure 2.

Expression analysis of SIMKK and SIMK genes by quantitative real‐time (qRT‐PCR) and immunoblotting analysis of total endogenous SIMK, active endogenous SIMK and both total and active GFP‐SIMK. (a) Deregulated transcript levels of SIMKK, total (endogenous native SIMKe + GFP‐tagged) SIMK and endogenous native SIMKe gene in SIMKKi L4 and GFP‐SIMK L5 transgenic lines of alfalfa. (b) Western blot detection of SIMK and GFP‐SIMK bands using SIMK antibody and (c) detection of active amount of respective proteins pSIMK and GFP‐pSIMK bands using pERK antibody in root tissue of control and transgenic alfalfa plants of SIMKKi (L4) and expressing 35S::GFP:SIMK (L5). Arrows point to the 46 kDa which corresponds to (b) endogenous SIMK and (c) endogenous pSIMK, while asterisks show bands around 72 kDa which corresponds to (b) GFP‐SIMK and (c) GFP‐pSIMK. (d,e) Log2 graphs depicting comparison of protein levels in respective lines (SIMKKi L4, GFP‐SIMK L5) relative to RSY L1, number of observations N and average value A (presented as inversed log2 values). GFP‐SIMK L5e refer to endogenous level of protein, while GFP‐SIMK L5 refers to GFP‐SIMK level. (d) Relative SIMK protein level in roots of control and transgenic plants (RSY L1, SIMKKi L4, GFP‐SIMK L5). (e) Relative pSIMK protein level in roots of control and transgenic plants (RSY L1, SIMKKi L4, GFP‐SIMK L5). (a,d,e) Statistics was calculated in Microsoft Excel using t‐test and is based on N = 3–8. Error bars show ± SD. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between treatments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n. s. indicates no statistical significance.

Quantitative RT‐PCR of native SIMKK, native SIMK (SIMKe) and total SIMK (meaning the sum of GFP‐SIMK and SIMKe levels) transcripts was performed in order to gain insight into transcriptional regulation of selected genes in transgenic lines as compared to RSY. This analysis revealed downregulation of SIMKK gene in SIMKKi line L4 to approximately 63% compared to SIMKK transcript level in RSY L1. Simultaneously, SIMKKi line L4 showed downregulation of native SIMKe transcript level to approximately 30‐40% (screened by two different sets of primers) compared to SIMK transcript level in RSY L1 (Figure 2a). In GFP‐SIMK line L5, total SIMK transcript level was upregulated approximately 3.14 times due to overexpression of GFP‐SIMK, while native SIMKe transcript level was downregulated to approximately 65% compared to SIMK transcript level in RSY L1 (Figure 2a). Western blot analysis for quantification of SIMK protein level (Figure 2b,d) and phosphorylated SIMK (pSIMK) protein level (Figure 2c,e) was performed in order to explain previously obtained phenotypical results at the level of protein abundance and activity. Endogenous SIMK protein with molecular mass around 46 kDa and recombinant GFP‐SIMK protein with molecular mass around 72 kDa (Figure 2b) were quantified (Figure 2d). Relative SIMK abundance was strongly decreased in SIMKKi line L4 to approximately 1 % (Figure 2b,d). Relative GFP‐SIMK abundance was strongly increased in 35S::GFP:SIMK line L5 to approximately 6.48 times (Figure 2b,d) showing upregulation similarly to relative transcript level (Figure 2a), while relative abundance of endogenous SIMK showed a decrease to approximately 49 % (Figure 2b,d) similarly to reduced relative transcript level (Figure 2a). These results are consistent with the root hair length phenotypes and indicate that relative SIMK abundance in above‐mentioned lines correlates with effectiveness of the root hair tip growth.

Phospho‐specific antibody was used to check out activity status of respective proteins. Endogenous phosphorylated pSIMK protein with molecular mass around 46 kDa and also phosphorylated GFP‐pSIMK with molecular mass around 72 kDa (Figure 2c) were quantified (Figure 2e). Relative level of pSIMK was considerably decreased in SIMKKi line L4 to approximately 12 % (Figure 2c,e) while relative level of GFP‐pSIMK was strongly increased in 35S::GFP:SIMK line L5 to approximately 8.21 times and relative level of endogenous pSIMK level showed non‐significant change compared to RSY line L1 (Figure 2c,e). These results are also consistent with root hair length phenotypic results. Moreover, they fit with previously published results showing that root hair growth requires activated SIMK (Šamaj et al., 2002).

Impact of overexpressed GFP‐SIMK on infection thread and nodule formation

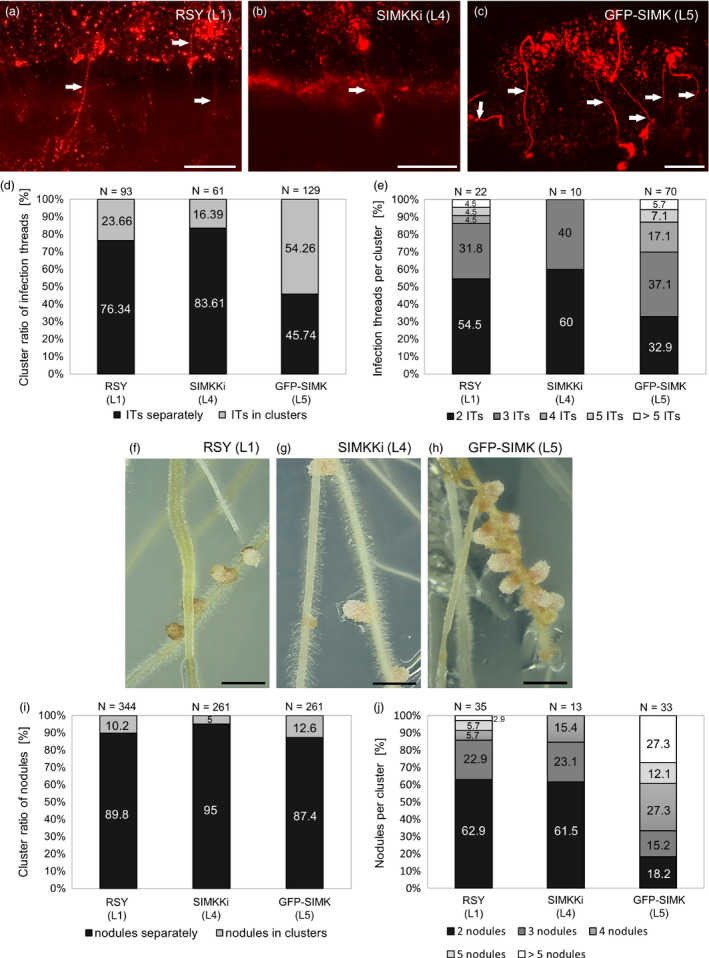

To get further insight into the possible involvement of SIMK in alfalfa symbiosis with beneficial microbes, we examined infection thread (IT) and nodule formation (Figure 3) after inoculation with S. meliloti (Sm2011 strain) labelled with monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP). Evaluation of ITs was performed 10‐day post‐inoculation (10 dpi) per whole root system in alfalfa RSY plants L1 (Figure 3a), transgenic SIMKKi plants L4 (Figure 3b) and GFP‐SIMK plants L5 (Figure 3c). Transgenic lines were compared to RSY and between each other. GFP‐SIMK line L5 showed increased IT clustering (Figure 3c‐e) and these ITs seem to be longer, consistently with previously observed long root hair phenotype. Quantitative analysis showed that most of ITs in RSY L1 (76.34 %) and SIMKKi L4 (83.61 %) developed individually, while only 45.74 % of ITs was spatially separated in GFP‐SIMK L5 (Figure 3d). The rest, 54.26 % of ITs in GFP‐SIMK L5 line was present in clusters. Portion of ITs in clusters was only 23.66 % in RSY L1 and 16.39 % in SIMKKi L4 (Figure 3d). In RSY L1 and SIMKKi L4, most of the clusters contained two or three ITs, while in GFP‐SIMK L5 there was a significant amount of clusters possessing also four or five ITs. In 5.7 % of clusters in GFP‐SIMK L5, we found more than five ITs; it occurred in only 4.5 % of clusters in RSY L1, while it was absent completely in SIMKKi L4 (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Infection thread and nodule formation in alfalfa roots inoculated with Sinorhizobium meliloti‐mRFP. (a–c) Overview of the infection threads containing S. meliloti with mRFP (white arrows) in roots of (a) wild‐type RSY line L1, (b) in transgenic SIMKKi line L4 and (c) in transgenic GFP‐SIMK line L5 at 10 dpi. (d) Ratio of individual/clustered infection threads (in %) at 10 dpi. (e) Number of infection threads per cluster (in %) at 10 dpi. (f–h) Representative images of root nodules formed in respective alfalfa lines, (f) control RSY line L1, (g) SIMKKi line L4 and (h) GFP‐SIMK line L5 inoculated with S. meliloti‐mRFP 15 dpi on Fåhreus medium. (i) Ratio of individual/clustered nodules (in %) at 15 dpi. (j) Number of nodules per cluster (in %) at 15 dpi. N = number of observations. Scale bar: (a–c) 100 µm, (f–h) 1 cm. Dpi = day post‐inoculation.

Together with previously published data that activated SIMK is required for root hair growth (Šamaj et al., 2002), SIMK can be involved also in the symbiosis with S. meliloti. Thus, more efficient formation of ITs in clusters may be directly induced by SIMK overexpression. To this point, we characterized association of SIMK with IT formation by localization of GFP‐SIMK in transgenic line L5 using live cell imaging. Alternatively, we detected SIMK also in RSY line L1 using immunolocalization. Both methods revealed association of SIMK with S. meliloti internalization sites in root hairs, such as specific accumulation of GFP‐SIMK in infection pockets (Figure S1a‐d) and in growing ITs (Figure S1e‐i). Immunostaining of phosphorylated MAPKs using phospho‐specific pERK 44/42 antibody showed colocalization with SIMK‐specific signal in ITs (Figure S1i‐l), indicating IT‐specific presence of SIMK in activated form.

When infection threads reach the nodule primordium, rhizobia are released into host cells by an endocytosis, which allows to form functional nitrogen‐fixing bacteroids within infected plant cells of the root nodule. Evaluation of nodule formation was performed 15 dpi per whole root system in alfalfa RSY plants of L1 (Figure 3f, S2a,d), transgenic SIMKKi plants of L4 (Figure 3g, S2b,e) and GFP‐SIMK plants of L5 (Figure 3h, S2c,f). SIMKKi line L4 formed significantly less nodules than RSY L1, while GFP‐SIMK line L5 produced similar number of nodules as RSY line L1 (Figure S2g). Interestingly, GFP‐SIMK line L5 often produced nodules in clusters (Figure 3h, S2c,f), which was less frequent in RSY line L1 and in SIMKKi line L4 (Figure S2a,b,d,e). Analysis of nodule clustering showed that 89.8 % of nodules in RSY L1, 95 % in SIMKKi L4 and 87.4 % in GFP‐SIMK L5 developed individually (Figure 3i). However, clusters in transgenic GFP‐SIMK L5 line contained much higher number of nodules in comparison with RSY L1 and SIMKKi L4 (Figure 3j). Detailed analysis revealed that 27.3 % of clusters in GFP‐SIMK line L5 possessed more than five/ six and more nodules while in RSY L1 it was only in 2.9 % of clusters (Figure 3j) and SIMKKi line L4 did not form clusters with more than five nodules (Figure 3j). On the contrary, RSY line L1 and SIMKKi line L4 had 62.9 % and 61.5 % of clusters formed from two nodules only, respectively, as compared to 18.2 % of such clusters in GFP‐SIMK line L5 (Figure 3j). It is resembling IT clustering where the ratio of clusters with two ITs represented 54.5 % and 60 % in RSY line L1 and SIMKKi line L4, respectively, but it was only 32.9 % in GFP‐SIMK line L5 (Figure 3e). These data suggest that GFP‐SIMK line L5 is very effectively able to produce ITs and nodules spatially organized in bigger clusters (Figure 3c,h). To confirm the nodule phenotype of characterized lines also in vivo, the root systems of alfalfa plants were documented after extraction from soil (Figure S3). Thorough surface examination revealed that RSY line L1 (Figure S3a), SIMKKi line L4 (Figure S3b) and GFP‐SIMK line L5 (Figure S3c) formed nodules in soil. In GFP‐SIMK line L5, formation of nodules in clusters has been confirmed (Figure S3c, inset image). Interestingly, development of the root system did not show considerable differences among lines (Figure S3). Analyzed plants were 9 months after transfer to soil, and the same plants were used also for above‐ground biomass analysis.

Impact of overexpressed GFP‐SIMK on shoot biomass and leaf formation

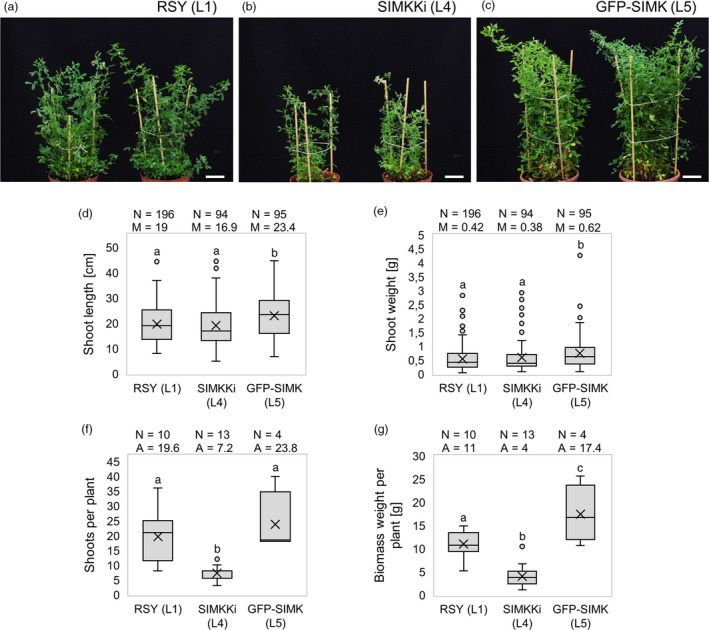

Besides the documentation of root hair phenotypes and subsequent alfalfa‐Sinorhizobium symbiotic interaction, we analyzed also impact of SIMK abundance and activity on alfalfa above‐ground biomass production (Figure 4) and on leaf development (Figure S4). Formation and regrowth of new individual shoots in alfalfa can be induced and synchronized by cutting off the green part. Documentation of plants growing in pots in the soil 60 days after cutting revealed smaller and thinner habitus of above‐ground parts in SIMKKi line L4 (Figure 4b) in comparison with RSY line L1 (Figure 4a). However, above‐ground parts in GFP‐SIMK line L5 showed more robust and bushy habitus (Figure 4c). In quantitative terms, GFP‐SIMK line L5 produced significantly longer shoots (Figure 4d) with significantly higher weight (Figure 4e) in comparison with both RSY line L1 and SIMKKi L4 plants. Consistently with the qualitative analysis (Figure 4a‐c), SIMKKi line L4 developed significantly lower number of shoots per plant in comparison with both RSY L1 and GFP‐SIMK L5 (Figure 4f). Taking together, the weight of above‐ground biomass was significantly decreased in SIMKKi L4 plants, but significantly increased in GFP‐SIMK L5 plants in comparison to control RSY L1 (Figure 4g). This results indicate that, in addition to the process of alfalfa‐Sinorhizobium symbiotic interactions, SIMK likely plays also an important role in the regulation of shoot development and green biomass production.

Figure 4.

Shoot biomass production in transgenic alfalfa plants grown in vivo. (a–c) Representative images of above‐ground parts of mature plants grown in pots in control RSY L1 (a), SIMKKi L4 (b) and GFP‐SIMK L5 (c). Regrown plants were documented 60 days after cutting the shoots. (d) Box plot graph depicting comparison in shoot length of indicated lines, number of observations N and median value M. (e) Box plot graph depicting comparison in shoot weight of indicated lines, number of observations N and median value M. (f) Box blot graph depicting comparison in number of shoots per plant of indicated lines, number of observations N and average value A. (g) Box plot graph depicting comparison in biomass weight per plant of indicated lines, number of observations N and average value A. Statistics was calculated in SigmaPlot11.0 using Kruskal–Wallis one‐way analysis of variance on ranks (Dunn's method) (d, e), or using one‐way analysis of variance (Holm–Sidak method) (f, g) and is based on (d, e) N = 94–196 and (f, g) N = 4–13. Different lower case letters indicate statistical significance between treatments (P < 0.05). Scale bar: (a–c) 4 cm.

Individual shoots of RSY line L1 regrown on plants 15 days after cutting off the green part contained shoot apical meristem with leaf primordia and already formed trifoliate compound leaves. They developed from nodes, interconnected by elongated internodes (Figure S4a). The size and shape of leaves of SIMKKi line L4, however, were considerably affected (Figure S4b). Leaves were smaller, narrower and slightly curled in SIMKKi line L4 in comparison with RSY line L1 (Figure S4b). SIMK overexpression in GFP‐SIMK line L5 led to enhanced development of shoots (Figure 4c‐e), represented mainly by formation of large leaves with long petioles (Figure S4c). Size and shape of leaves were analyzed in more details. Five representative individual shoots from analyzed plants (from 5 plants per line) were selected, and first three fully developed leaves beneath the shoot apex were dissected, photographed and measured. Among leaves of the individual shoot, regardless of alfalfa line being analyzed there were no visible morphological differences, only the smallest size of the first leaf in comparison with second and third leaf according to the leaf developmental sequence within the shoot (Figure S4d‐f). Regarding the shape, SIMKKi line L4 showed much narrow leaves and less notched at the apex, while GFP‐SIMK line L5 showed longer and broader leaves in comparison with more oval leaves of RSY line L1 (Figure S4d‐f). Comparing size of analyzed leaves, SIMKKi line L4 contained always the smallest leaves, which was demonstrated in all types (first, second and third leaf, Figure S4g). Interestingly, the third leaves of GFP‐SIMK line L5 showed the largest leaf area (Figure S4g). These phenotypical differences were corroborated by length of leaf petioles that were significantly shorter in all leaves of SIMKKi line L4, but significantly longer in third leaves of GFP‐SIMK line L5 (Figure S4h). These data indicate that SIMK plays pleiotropic roles in developmental programmes not only in alfalfa roots, but also in above‐ground organs. This is documented by reduced shoot and leaf development when SIMK is downregulated in SIMKKi L4 line. However, SIMK overproduction in GFP‐SIMK line L5 leads to enhanced shoot biomass production, leaf and petiole development, which may represent potentially valuable biotechnological trait of alfalfa as an important forage crop.

Subcellular localization of GFP‐SIMK

In order to observe subcellular localization of SIMK in alfalfa plants, we tagged it with GFP marker and overexpressed such fusion protein under the control of CaMV 35S promoter. Subcellular localization of GFP‐SIMK was performed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and Airyscan CLSM. First, transient transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves was performed to test expression of 35S::GFP:SIMK construct. GFP‐SIMK was preferentially localized to the nuclei (except nucleoli), and it was also dispersed in cytoplasmic structures (Figure S5). In stably transformed alfalfa plants, GFP‐SIMK preferentially accumulated in the nucleus and less in the cytoplasmic structures of epidermal cells and stomata in leaf (Figure S6a) and hypocotyl (Figure S6b). Maximum intensity projection provided overview of root tip and revealed nuclear and cytoplasmic GFP‐SIMK localization (Figure S6c) with depleted signal in nucleoli. Similar subcellular localization was found also in root hairs (Figure S6d) and epidermal cells of lateral roots (Figure S6e). In growing root hairs, GFP‐SIMK was mostly localized in nuclei and in the cytoplasm at the root hair tips (Figure S6d). This pattern of subcellular localization in root cells was confirmed in GFP‐SIMK line L5 by using whole mount immunofluorescence co‐labelling (Tichá et al., 2020) with GFP‐specific (see Materials and Methods) and phospho‐specific (anti‐phospho‐p44/42) antibodies (Figure S7). Imaging of co‐immunolabelled samples using Airyscan CLSM revealed that GFP‐SIMK is localized in distinct spot‐like structures in the nucleoplasm and in cytoplasmic structures, preferentially in activated form (Figure S7). Live cell imaging of GFP‐tagged SIMK, as well as SIMK immunolocalization in root hairs of alfalfa plants inoculated with S. meliloti revealed presence of SIMK along ITs and its accumulation in infection pockets (Figure S1).

Subcellular localization of SIMK in root nodules

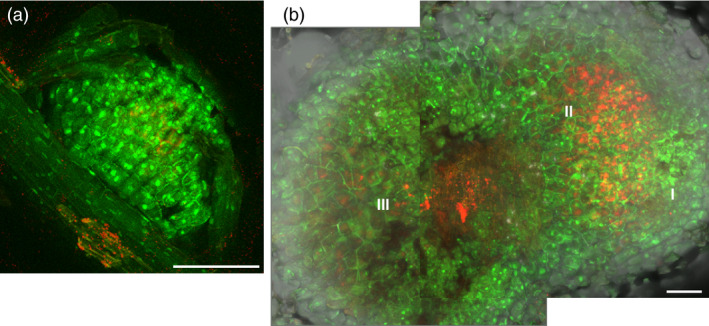

To analyse the expression level and localization of GFP‐SIMK in root nodules of L5 line (Figure 5) inoculated with mRFP‐marked S. meliloti, nodules were harvested 10 dpi (Figure 5a) and 20 dpi (Figure 5b) and analyzed by CLSM live cell imaging with the appropriate settings of lasers for GFP and mRFP channels. GFP‐SIMK was expressed in young nodules (Figure 5a) and also in mature nodules, including meristematic (I), infection (II) and symbiotic (III) zones (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Localization of GFP‐SIMK in alfalfa root nodules. Examples of nodule (a) at the early stage of development and (b) at the late stage of development observed by CLSM. Localization of fused GFP‐SIMK protein (green) in root nodules induced after inoculation with S. meliloti‐mRFP (red) on plants of GFP‐SIMK line L5 at 10 dpi (a) and 20 dpi (b). A composite image of two consequential frames is shown in (b). Tissue organization of the late nodule: I, meristematic zone; II, infection and differentiation zone; III, symbiotic zone. Scale bar: (a) 100 µm; (b) 200 µm.

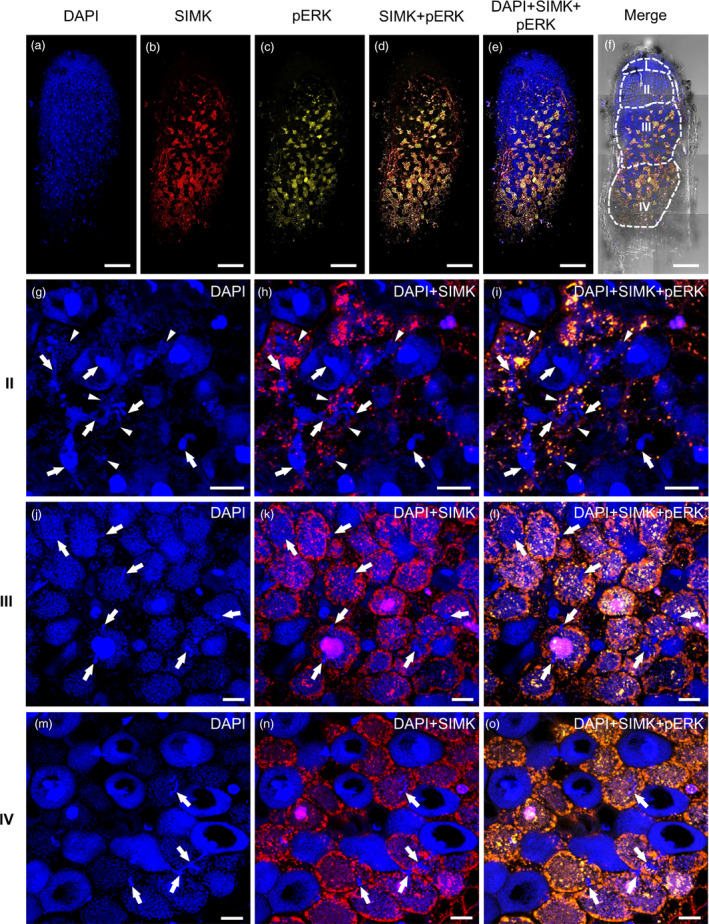

Next, root nodules developed on alfalfa root system 15 dpi with S. meliloti were characterized using immunofluorescence localization microscopy. Hand‐made median nodule sections were used for visualization of cell nuclei (Figure 6a), for immunolocalization of SIMK using anti‐SIMK‐specific antibody (Figure 6b,d,e) and for immunolocalization of activated pool of MAPKs using anti‐phospho‐p44/42 antibody (Figure 6c‐e). The pattern of SIMK and activated MAPK localization was documented in infection (II), symbiotic (III) and senescent (IV) nodule zones (Figure 6f). Importantly, DAPI staining of the DNA nuclear content in alfalfa root nodule cells stained also S. meliloti (Figure 6g,j,m). In the infection zone (II), there were clearly visible ITs among the nodule cells, forming terminal branches inside of the cells, from which bacteria were released (Figure 6g). SIMK was localized mainly around ITs in the form of prominent spots (Figure 6h). Labelling with anti‐phospho‐p44/42 antibody showed colocalization with SIMK‐specific signal, suggesting that MAPKs present in these spots were phosphorylated (Figures 6i). Waste majority of cells in the symbiotic zone (III) contained bacteroids already differentiated in the cytoplasm, although several ITs were still present in this zone (Figure 6j). SIMK was localized mainly in cortical layer of symbiotic cells and in some prominent spots in the cytoplasm (Figure 6k). Labelling pattern with anti‐phospho‐p44/42 antibody showed high colocalization with SIMK signal (Figure 6l). In the senescent zone of nodules (IV), symbiotic cells contained bacteroids and showed positive reaction to immunolabelling, while nodule cells entering the senescence stage were massively enriched with bacteroids (overstained with DAPI) and vacuolated, while their immunoreactivity to MAPK‐specific antibodies was abolished (Figure 6m‐o). Remnants of ITs were still present; however, SIMK, unlike the situation in cells of the infection zone (Figure 6h), was not associated with them (Figure 6n). Rather, SIMK was massively localized to cell cortex and to some spots in the cytoplasm (Figure 6n). Colocalization with anti‐phospho‐p44/42 antibody (Figure 6o) indicated that SIMK in these locations was activated.

Figure 6.

Overview of SIMK localization and distribution in root nodules induced after Sinorhizobium meliloti inoculation of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants using immunofluorescence localization microscopy. (a–f) Overview of the representative root nodule. This overview was mounted as a composite image out of eight consequential frames. (a) Hand‐sectioned root nodules were stained for DNA using DAPI, and (b) immunostained for SIMK using anti‐AtMPK6 antibody and (c) for phosphorylated MAPKs using phospho‐specific pERK 44/42 antibody. (d) Overlay of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs, and (e) distribution of cell nuclei in SIMK‐phosphorylated MAPKs overlay. (f) Bright‐field image of the same nodule with overlaid fluorescence channels schematically depicts distribution of individual developmental zones, namely meristematic (I), infection (II), symbiotic (III) and senescent (IV) zones. (g‐o) Representative images of cells from different nodule developmental zones: (II, g–i) the infection zone, (III, j–l) the symbiotic zone and (IV, m–o) the senescent zone. (g,j,m) Blue channels represent DAPI staining, (h,k,n) red channels (overlaid with DAPI channel) represent SIMK immunolocalization, and (i,l,o) yellow channels (overlaid with DAPI channel) represent colocalization (in yellow colour) of SIMK with phosphorylated MAPKs. Note specific staining of bacteria with DAPI. Infection threads are pointed by arrows, and releases of bacteria from branched infection threads in the form of infection droplets are pointed by arrowheads. Scale bars: (a–f) 10 mm, (g–o) 20 µm.

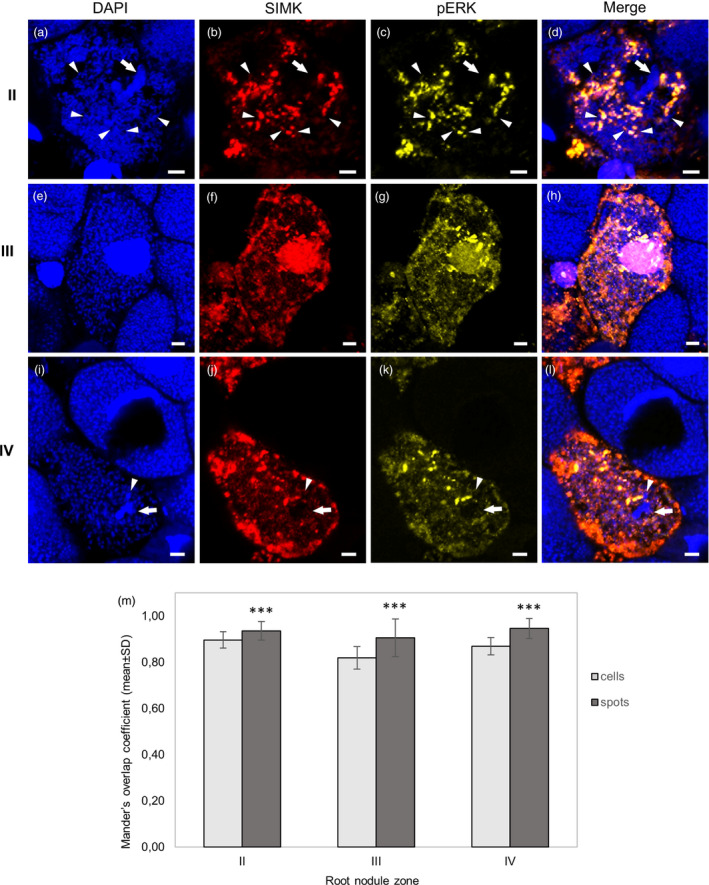

Detailed analyses revealed that ITs invade cells in the infection zone (II) and terminate by branched finger‐like extensions from which bacteria were released in the form of infection droplets (Figure 7a). SIMK was accumulated in these subcellular domains (faint red signal in Figure 7b,d), but particularly finger‐like extensions and released bacteria in the cytoplasm were decorated by prominent spot‐like structures, highly positive for both SIMK (Figure 7b,d) and phosphorylated MAPKs (Figure 7c,d). In the symbiotic zone (III), bacteria were already internalized in differentiated bacteroids (Figure 7e), which changed dramatically also SIMK localization pattern. Both SIMK (Figure 7f) and phosphorylated MAPKs (Figure 7g) were located in nuclei, in cytoplasm among differentiated bacteroids, and in bright spot‐like structures around the nuclei or in the nuclei. In all these places, signal of both SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs colocalized (Figure 7h). In the senescent zone (IV), both DAPI signal intensity (Figure 7i) and immunofluorescence detection (Figure 7j‐l) clearly discriminated between still active and senescing cells. In active cells, SIMK (Figure 7j) and phosphorylated MAPKs (Figure 7k) were located in cytoplasm among bacteroids and in spot‐like structures, and both colocalized (Figure 7l). SIMK was located in small spots close to differentiated bacteroids (Figure 7j,l) and topologically similar localization signal was achieved using anti‐phospho‐p44/42 antibody (Figure 7k,l), leading to high degree of colocalization with SIMK (Figure 7l). To determine quantitatively degree of colocalization of SIMK signal with phospho‐p44/42 antibody, we performed colocalization analysis in certain regions of interests (ROIs) in cells of infection zone (II, Figure S8, mean Mander’s coefficient 0.90), symbiotic zone (III, Figure S10, mean Mander’s coefficient 0.82) and senescent zone (IV, Figure S12, mean Mander’s coefficient 0.87). These data indicated that overall colocalization rate of SIMK with phosphorylated pool of MAPKs is rather high in cells of all developmental zones of root nodules. Next, we analyzed degree of colocalization of SIMK with phosphorylated pool of MAPKs in subcellular spot‐like structures, closely associated with bacteroids. In cells of infection zone (II), mean Mander’s coefficient reached 0.94 (Figure S9); in cells of symbiotic zone (III), it was 0.91 (Figure S11); and in cells of senescent zone (IV), it was 0.95 (Figure S13). The comparison of mean Mander’s coefficients between large areas (ROIs) of the cells and individual spots clearly showed significantly higher degree of colocalization between SIMK and phosphorylated pool of MAPKs in spot‐like structures (Figure 7m). This analysis revealed that within the infection zone, SIMK is located mainly in spots close to released bacteria and is activated. In cells of symbiotic and senescent zones, it is located also in other places in nucleus and cytoplasm, nevertheless, SIMK presence in spots close to bacteroids is still high, and it is always activated. Collectively, SIMK was located in all places related to internalization of symbiotic bacteria into host cells of functional root nodules, and in later stages of symbiotic process, SIMK was closely associated with bacteroids. Simultaneous immunolocalization of phosphorylated MAPK motives clearly indicated that SIMK was activated in all these locations.

Figure 7.

Detailed SIMK localization in root nodule cells induced by Sinorhizobium meliloti on alfalfa control RSY L1 plants using immunofluorescence localization microscopy. (a–d) Cell of the infection zone (II) with branched infection thread (arrow) during the release of bacteria in the form of infection droplets (arrowheads). (e–h) Cells of the symbiotic zone (III) with developed bacteroids. (i–l) Cells of the senescent zone (IV) with developed bacteroids. (a,e,i) Nuclei and bacteria are stained with DAPI, (b,f,j) SIMK (in red) is immunostained with anti‐AtMPK6 antibody and (c,g,k) phosphorylated MAPKs (in yellow) are immunostained with phospho‐specific pERK 44/42 antibody. (d,h,l) Overlay of DAPI, SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs. Note specific staining of bacteria with DAPI. Infection threads are pointed by arrows, and releases of bacteria from branched infection threads in the form of infection droplets are pointed by arrowheads. (m) Averaged Mander’s overlap coefficients from quantitative colocalization of SIMK with phosphorylated MAPKs evaluated in defined ROIs in each zone (cells), and in particular subcellular structures (spots) of the infection zone (II, N = 23 ROIs in cells and N = 84 in spots), the symbiotic zone (III, N = 23 ROIs in cells and N = 83 in spots) and the senescent zone (IV, N = 15 ROIs in cells and N = 32 in spots). Quantitative colocalization analysis is presented in Figures S8–S13. Statistics was calculated in Microsoft Excel using t‐test. Error bars show ± SD. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between treatments (***P < 0.001). Scale bar: (a–l) 5 µm.

Discussion

Leguminous plant species are important members of the agricultural ecosystems and are widely utilized also in nutritional production industry. They are able to grow in soils deficient for nitrogen by performing symbiotic interaction with rhizobia in root nodules, specialized organs for atmospheric nitrogen fixation. Alfalfa is an important legume crop in agronomy, especially for forage or silage production. Both initial and later interactions between legumes and rhizobia require exchange of different signals and activation of signal transduction pathways. Protein phosphorylation in general is one of the major signalling mechanisms controlling cellular responses to external stimuli. In particular, MAPK‐dependent signal transduction cascades regulate many developmental and cellular processes in plants (Komis et al., 2018). Systemic approaches indicated that legume–rhizobia interactions and subsequent root nodule development involve activity of various protein kinases (Grimsrud et al., 2010; Roy et al., 2020). Main effort in research of symbiotic nitrogen fixation is conducted in legumes important for food production such as bean (Ge et al., 2016), soybean (Hyoungseok et al., 2008), pea (Stracke et al., 2002) or non‐crop model Medicago truncatula (Ryu et al., 2017). However, the regulation of symbiotic interactions, nodule development and nitrogen fixation, including possible involvement of MAPK signalling, is much less clear in alfalfa. Here, we studied effects of both SIMK downregulation and overexpression in alfalfa using genetically modified transgenic lines. We characterized parameters such as length of root hairs, phenotype of above‐ground plant parts and size of leaves, but also addressed possible involvement of SIMK in the efficiency of root nodulation, through determination of clustering of ITs and nodules. To achieve this goal, we analyzed transgenic alfalfa plants. In order to decrease SIMK functions, we prepared two independent RNAi transgenic lines downregulating SIMKK, an upstream activator of SIMK (SIMKKi lines). We confirmed that SIMK expression was strongly downregulated in these lines. In order to enhance SIMK functions, we cloned N‐terminal fusion construct of enhanced GFP (eGFP) with SIMK driven under constitutive 35S promoter (35S::GFP:SIMK) and stably transformed this construct into alfalfa plants. Using these transgenic lines, we were able to describe subcellular localization of GFP‐SIMK fusion protein. Our observations from live cell microscopy revealed GFP‐SIMK localization predominantly to the nucleus and cytoplasm in cells of diverse organs, which is consistent with previously published data on SIMK immunolocalization in alfalfa roots (Baluška et al., 2000a; Ovečka et al., 2014). The GFP‐SIMK was also localized in tips of growing root hairs in agreement with previously published SIMK localization pattern using immunofluorescence microscopy (Šamaj et al., 2002). It is known that during root hair formation, SIMK is activated and redistributed from nucleus into growing root hair tips. Moreover, the positive role of SIMK in root hair tip growth was confirmed by overexpression of gain‐of‐function SIMK in transgenic plants of tobacco showing longer root hairs (Šamaj et al., 2002). The question remained whether genetically based downregulation or overexpression of SIMK might have an effect on the root hair growth in homologous alfalfa species. We addressed this question and report here about earlier cessation of root hair tip growth leading to short root hairs in SIMKKi lines with strongly downregulated SIMK, while GFP‐SIMK overexpressing lines showed an opposite phenotype manifested by later cessation of the tip growth and longer root hairs. Effectivity in the root hair tip growth is an important aspect affecting early stages of plant–rhizobia interaction.

Major task of this study was to find out whether SIMK is involved in the regulation of root nodulation. Publications reporting involvement of MAPK signalling cascades in nodule development are rather scarce. A comparative study confirmed that MAPK signalling cascade and stress‐related responses are activated early upon plant infection with symbiotic rhizobia (Lopez‐Gomez et al., 2012). It has been shown that SIP2 is a MAPKK in Lotus japonicus, which interacts with symbiosis receptor‐like kinase SymRK (Chen et al., 2012). Recent study demonstrated that phosphorylation target of SIP2 is LjMPK6 (Yin et al., 2019). Thus, signalling module SymRK‐SIP2‐MPK6 is required for nodulation, playing a positive role in nodule formation and organogenesis in L. japonicus. The orthologue of SIP2 has been identified in M. truncatula as MtMAPKK4 (Chen et al., 2017). It is involved in the regulation of different plant developmental processes and also mediates root nodule formation. Downstream interacting partners of MtMKK4 are MtMPK3 and MtMPK6 (Chen et al., 2017). Moreover, another M. truncatula MAPKK, namely MtMKK5, also interacts with MtMPK3 and MtMPK6 in alternative signalling pathway, having a negative role in the symbiotic nodule formation (Ryu et al., 2017). In alfalfa, SIMKK is specific upstream activator of SIMK under salt stress (Kiegerl et al., 2000). Interestingly, SIMKK shares 88% amino acid similarity with LjSIP2 (Chen et al., 2012) and by its amino acid sequence is highly similar also to MtMKK4 (Chen et al., 2017). Previously, Bekešová et al. (2015) showed decreased accumulation of phosphorylated SIMK in SIMKKi lines which is confirmed also in this study. SIMKKi transgenic line exhibited strong downregulation of SIMKK and SIMK transcripts and SIMK protein and showed shorter root hairs and less nodules. Such decreases in root hair growth and formation of ITs and nodules in the SIMKKi line but enhanced clustering of ITs and nodules in overexpression GFP‐SIMK line support a positive role of SIMK in the alfalfa nodulation.

Clustering of ITs after inoculation with S. meliloti in overexpressor GFP‐SIMK line is an interesting finding. Moreover, clustered development of ITs correlated well with clustered formation of fully developed and equally growing root nodules. This may represent important aspect of root nodule formation, since appropriate number of nodules developed in whole root system is tightly regulated by the plant and depends on overall physiological conditions. It has been observed that legumes tend to maintain development of the minimal number of nodules that are required for optimal growth at given growth conditions (Mortier et al., 2012). Control of the nodule number is a feedback mechanism that, at the level of the whole root system, may originate in early nodules that hinder further nodule development, a phenomenon called ‘autoregulation of nodulation’ (Delves et al., 1986), or may involve long‐distance communication and control from the shoots (Sasaki et al., 2014). This mechanism is regulated by local and systemic endogenous signals. Locally, the number of developing nodules is controlled through ethylene signalling pathway, restricting the initiation of nodule primordia to cortical cells close to xylem poles (Heidstra et al., 1997), and through nitrate‐induced signalling peptides of the CLAVATA (CLV)/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION (ESR)‐RELATED PROTEIN (CLE) (Mortier et al., 2010; Saur et al., 2011). A particular class of these small signalling CLE peptides, induced by rhizobia infection, controls also systemic regulation of nodulation (Concha and Doerner, 2020; Djordjevic et al., 2015; Mortier et al., 2010). CLE peptides move as a long‐distance signals from roots to shoots where specifically interact with shoot receptors, such as leucine‐rich‐repeat receptor SUPER NUMERIC NODULES (SUNN) in M. truncatula (Schnabel et al., 2005), and negatively autoregulate the nodule number. On the other hand, root competence for nodulation is controlled also by the microRNAs such as miR2111, which is produced upon activity of the receptor Compact Root Architecture 2 (CRA2) in shoots, and affecting positively root nodulation as systemic regulation signal (Gautrat et al., 2020). This feedback mechanism is controlled by the number, the activity and the age of early‐developed nodules (Pierce and Bauer, 1983; Caetano‐Anollés et al., 1991). Formation of IT and nodule clusters in GFP‐SIMK lines may indicate a new SIMK role in spatial control of nodule formation on the root system. Possible explanation of increased nodule numbers developing close to each other and forming clusters might require SIMK involvement in IT formation and viability, as less infection events might abort in early stages of development. This unique aspect of nodulation process and mode of its regulation within the whole root system certainly deserves further detailed study.

Possible scenario how SIMK may be involved in alfalfa nodulation, and symbiosis with S. meliloti can be anticipated from its subcellular localization pattern. Originally, we observed during root hair tip growth that SIMK relocates from nucleus to the tip of growing root hairs (Šamaj et al., 2002). Upon salt stress, both SIMKK and SIMK became activated and relocated from nucleus to cytoplasm, where they accumulated in spot‐like structures (Ovečka et al., 2014). Importantly, subcellular localization of SIMK in root nodules using immunofluorescence detection revealed close association of SIMK with terminal branching of ITs that were invading cells within the infection zone of root nodules. These branched finger‐like extensions represented the intracellular places of rhizobia release from ITs in the form of infection droplets. We found SIMK prominently accumulated in such subcellular domains, in the form of spot‐like structures decorating finger‐like extensions of the ITs and released bacteria. Activated state of SIMK in such locations was confirmed by colocalization using anti‐SIMK and anti‐phospho‐p44/42‐specific antibodies. In the symbiotic zone of root nodules, activated SIMK was located in nuclei and in cytoplasm. The specific pattern of SIMK localization in the cytoplasm, in the form of small spots, was closely related to distribution of differentiated bacteroids, particularly in cells of the symbiotic and senescent zones of root nodules. Colocalization with anti‐phospho‐p44/42‐specific antibody again revealed that SIMK was activated in all these locations within different nodule zones. Thus, local release of rhizobia from ITs and their accommodation in nodule cells up to differentiation of functional bacteroids involve active form of SIMK.

Another aspect interesting from the biotechnological point of view is the development and production of above‐ground plant parts. Particularly in alfalfa, an important forage crop, total leaf surface area and shoot biomass are agronomical parameters of interest. In this respect, genetic manipulation of SIMK brought interesting and potentially promising results. Downregulation of SIMKK and SIMK genes in SIMKKi lines influenced negatively the development of above‐ground plant parts, leading to formation of smaller leaves and production of less shoot biomass per plant. SIMK overexpression in GFP‐SIMK lines, on the other hand, resulted in higher shoot biomass per plant, production of bigger size of analyzed leaves and their better distribution in shoots due to the longer petioles. This result may support a general effort of alfalfa biotechnological improvement as a forage crop. Nowadays, genetic, genomic and recombinant DNA technology approaches are widely utilized in alfalfa improvements, including leaf production parameters and biomass yield (Biazzi et al., 2017; Lei et al., 2017). Some physiological shoot and leaf characteristics of alfalfa were improved by transgenic approach. For example, genetic modification of the SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN‐LIKE 8 (MsSPL8) gene in alfalfa significantly altered shoot architecture. Knock‐down of MsSPL8 significantly increased shoot branching and biomass yield; however, shoot branching was suppressed, and biomass yield was reduced by MsSPL8 overexpression (Gou et al., 2018). Overexpression of WXP1, a gene encoding AP2 domain‐containing putative transcription factor from M. truncatula under the control of the 35S promoter in alfalfa resulted in excessive formation of cuticular wax layer on leaves. Such leaves were more resistant to water loss making these plants more resistant against drought stress (Zhang et al., 2005). Alfalfa develops typical compound leaves (Efroni et al., 2010) and increase of total leaf surface area, together with shoot biomass increase that we observed in SIMK overexpressing lines, may eventually influence also other production parameters including light acquisition efficiency.

Conclusively, we show that SIMK plays a positive role in alfalfa nodulation process and has a positive impact also on some other important agronomical factors, such as shoot biomass production, petiole and leaf development. SIMK is connected with internalization of symbiotic bacteria into host cells in root nodules and later on, closely associates with bacteroids. SIMKK‐SIMK signalling module thus represents potentially new regulatory pathway required for the establishment of symbiotic interaction between rhizobia and alfalfa. This study opens a new door for alfalfa biotechnological improvement by genetic manipulation of MAPK signalling.

Experimental procedures

Plant and bacterial material

Somatic embryos of M. sativa cv. Regen‐SY carrying 35S::GFP:SIMK construct or SIMKK RNAi carrying pHellsgate12 plasmid driven under 35S promoter (obtained from CSIRO Plant Industry, Australia) with well‐developed root poles were separated, individually transferred and inserted into root and plant development medium (MMS) or Fåhreus medium without nitrogen (FAH‐N2; Fåhreus, 1957). Plants were inoculated with S. meliloti SM2011 (Casse et al., 1979).

Cloning of 35S::GFP:SIMK and stable transformation of alfalfa

To obtain stable transformed line of alfalfa with N‐terminal fusion construct of enhanced GFP (eGFP) with SIMK driven under 35S promoter (35S::GFP:SIMK), leaves of mature plants were transformed with Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying 35S::GFP:SIMK in pB7m34GW,0 expression plasmid (Karimi et al., 2005). Construction of 35S::GFP:SIMK in pB7m34GW,0 was performed by MultiSite Gateway® Three‐fragment vector construction kit, using pEN‐L4‐2‐R1TM carrying p35S sequence (Karimi et al., 2007), pEN‐L1‐F‐L2TM carrying eGFP sequence (Karimi et al., 2007) and pDONRTMP2R‐P3 carrying SIMK cDNA sequence (https://www.thermofisher.com). In the first step, 1188 bp SIMK PCR fragment was amplified using specific primers listed in Table S1 and total cDNA of alfalfa as a template. Donor and destination vectors were transformed in Escherichia coli strain TOP10 during construct preparation. Final destination vector was used for A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 transformation.

Kanamycin (50 µg/ml) resistance was used for selection of donor vectors, and spectinomycin (100 µg/ml) was used for selection of destination vector, and phosphinothricin (50 µg/ml) as the selection marker in planta together with ticarcillin (500 µg/ml) to inhibit Agrobacterium growth after transformation. Stable alfalfa transformation was performed by co‐cultivation method with Agrobacterium described by Samac and Austin‐Phillips, 2006. Leaves from well‐developed plant nodes were surface sterilized, cut in half cross‐wise with sterile scalpel blade, incubated with overnight Agrobacterium culture showing cell density between 0.6 and 0.8 at A600 nm for 30 minutes. Induction of callogenesis from leaf explants, production of somatic embryos from calli, development of shoots and somatic embryo rooting were performed on the appropriate media in the culture chamber at 22°C, 70% humidity, light intensity 100 µmol.m‐2s‐1 and 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod. Regenerated plants were maintained on media with phosphinothricin selection and tested for the presence of GFP‐SIMK protein using molecular genotyping or fluorescent microscope. Transgenic alfalfa plants were further propagated in sterile culture via somatic embryogenesis.

Phenotypic analysis and plant inoculation with S. meliloti

Wild‐type plants of alfalfa RSY (two independent lines L1 and L2), transgenic plants with SIMKK RNAi (SIMKKi, two independent transgenic lines L3 and L4) and transgenic plants carrying 35S::GFP:SIMK construct (GFP‐SIMK, two independent transgenic lines L5 and L6) were used for phenotype analysis of root hairs. Plants 18‐day‐old originating from somatic embryos were transferred to Petri dishes with FAH‐N2 medium containing 13 g/L micro agar. These plants were used for root hair imaging with Axio Zoom.V16 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) in light conditions. Statistics was calculated in SigmaPlot11.0 using Kruskal–Wallis one‐way analysis of variance on ranks (Dunn's method) and is based on N = 529‐1924. Different lower case letters indicate statistical significance between treatments (p < 0.05). Plants were then inoculated with bacteria S. meliloti strain Sm2011 labelled with mRFP with OD600 = 0.5 (Boivin et al., 1990). After 10‐day post‐inoculation (10 dpi), the infection threads were counted using Axio Zoom.V16 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) with excitation laser lines at 590 nm for mRFP and plants were scanned 5, 10, 15 and 20 dpi for counting of nodules.

Pictures of above‐ground parts of alfalfa plants of RSY line L1, SIMKKi line L4 and GFP‐SIMK line L5 regrown in pots 60 days after shoot cutting (Gou et al., 2018) were acquired by digital camera (Nikon D5000, Japan). Individual shoots were detached from the plants and shoot length (in cm), shoot weight (in g), number of shoots per plant and biomass weight per plant (in g) were recorded. Quantitative analysis was performed in SigmaPlot11.0 using Kruskal–Wallis one‐way analysis of variance on ranks (Dunn's method) or using one‐way analysis of variance (Holm–Sidak method) and was based on N = 94‐196 shoots (for shoot length and weight) and N = 4‐13 plants (for number of shoots per plant and biomass weight). Pictures of fresh shoots from alfalfa plants RSY line L1, SIMKKi line L4 and GFP‐SIMK line L5 and images of first three developed leaves beneath the shoot apex from mature plants of RSY line L1, SIMKKi line L4 and GFP‐SIMK line L5 grown in pots 15 days after cutting of the above‐ground part were taken by digital camera (Nikon D5000, Japan). Quantitative analysis of total leaf area (area of left, right and apical leaflet together) and full length of the petioles were performed on 1st, 2nd and 3rd leaf of one shoot. In total, leaves of 5 independent shoots from 5 independent plants (maximal N = 25 for each 1st, 2nd and 3rd trifoliate leaf) of each line were analyzed. Total leaf area and length of the petioles were measured using measurement functions of ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) and statistically evaluated in SigmaPlot11.0 using two‐way analysis of variance (Holm–Sidak method) based on N = 11‐25 (leaf area) and N = 25 (petiole length). Different lower case letters indicate statistical significance between treatments (p < 0.05).

Quantitative analysis of transcript levels by RT‐qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from the roots of wild‐type plants of alfalfa RSY line L1, transgenic plants with SIMKK RNAi (SIMKKi L4) and transgenic plants carrying 35S::GFP:SIMK construct (GFP‐SIMK L5), powdered in liquid nitrogen, using phenol–chlorophorm extraction (Sigma‐Aldrich, USA). RNA concentration and purity were determined before DNaseI digestion with a NanoDrop Lite (Thermo Scientific, USA). The template‐primer mix for reverse transcription was composed of 1 µl oligo(dT) primers, 1 µl RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor (Promega, USA), 1 µg RNA and PCR H2O in a total volume of 14 µl. The mixture was denaturated at 70°C for 10 min. The following components were added: 4 µl M‐MLV reverse transcriptase 5x reaction buffer (Promega, USA), 1 µl deoxynucleotide mix (10 mM each) and 1 µl M‐MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA) in a total volume of 6 µl. Reverse transcriptions were performed under the following conditions: 42°C for 50 min and 65°C for 15 min for inactivation of the reverse transcriptase. qRT‐PCR was performed in a 96‐well plate with the StepOnePlus Real‐Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) using SYBR Green to monitor dsDNA synthesis. The reaction contained 5 µl Power SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Life Technologies, USA), 2.5 µl cDNA and 2.5 µl gene‐specific primers (0.5 µM). The following standard thermal profile was used for all PCRs: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Experiments were run in three biological replicates. The transcription data were normalized to the transcription of ACT2 as a reference gene, and relative gene transcription was calculated by the 2˄(−ΔΔCt) method. Relative transcript levels were calculated as a ratio to control RSY L1, and thus, RSY level was always one without dispersion of variation. Statistics was calculated in Microsoft Excel using t‐test and was based on N = 3. Error bars represent ± SD. Asterisks indicated statistical significance between treatments (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n. s. did not indicate statistical significance). The primers are listed in Table S1. Primers for detection of total (endogenous native SIMKe + GFP‐tagged) SIMK transcript were specific for third exon of SIMK gene. Primers for endogenous native SIMKe transcript were specific for 5’ UTR sequence and first exon of SIMK gene.

Immunoblotting analysis

Immunoblotting analysis was performed as described in Takáč et al. (2017). Plants of 20‐day‐old alfalfa RSY L1, transgenic plants with SIMKK RNAi construct (SIMKKi L4) and transgenic plants carrying 35S::GFP:SIMK construct (GFP‐SIMK L5) were used for immunoblotting analysis. Roots from 20‐day‐old plants of alfalfa were homogenized using liquid nitrogen to fine powder, and the proteins were extracted in E‐buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 75 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaF, 10% (v/v) glycerol, Complete™ EDTA‐free protease inhibitor and PhosSTOP™ phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (both from Roche, Basel, Switzerland)]. After centrifugation, supernatants were mixed with Laemmli buffer [final concentration 62.5 mM Tris‐HCl (pH 6.8), 2% (w/v) SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 300 mM 2‐mercaptoethanol]. After protein concentration measurement using Bradford assay, equal protein amounts (10 ng) were separated on 12% TGX Stain‐Free™ (Bio‐Rad) gels (Bio‐Rad). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes in a wet tank unit (Bio‐Rad) overnight at 24 V and 4°C using the Tris‐glycine‐methanol transfer buffer. Membranes were blocked in 4% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in Tris‐buffered‐saline (TBS, 100 mM Tris‐HCl; 150 mM NaCl; pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight. Following washing step with TBS‐T (TBS, 0.1% Tween‐20) and incubation with polyclonal anti‐AtMPK6 antibody (Sigma, Life Science, USA), highly specific for SIMK detection (Bekešová et al., 2015), diluted 1:15000 in TBST‐T containing 1% (w/v) BSA and anti‐Phospho‐p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2, Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (Cell Signaling, Netherlands) diluted 1:1000 in TBS‐T containing 1% (w/v) BSA at 4°C overnight. Following five washing steps in TBS‐T and incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti‐rabbit IgG secondary antibody (diluted 1:5000) in the both cases of anti‐AtMPK6 and anti‐phospho‐p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2, Thr202/Tyr204) primary antibody. The signals were developed using Clarity Western ECL substrate (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA) and detected on Chemidoc MP documentation system (Bio‐Rad). In total, eight immunoblots were performed from three biological samples representing different lines. Arbitrary units measured from immunoblotting using software Image Lab (Bio‐Rad, USA) were normalized according to Stain‐Free gels for corrections of imbalanced loading. Relative protein levels were after that calculated as a ratio to control RSY L1; thus, RSY level is one (zero in log2 graphs) without dispersion of variation. Statistics was calculated in Microsoft Excel using t‐test and was based on N = 3‐8. Error bars represent ± SD. Asterisks indicated statistical significance between treatments, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n. s. did not indicate statistical significance.

Live cell subcellular localization of GFP‐SIMK

Agrobacteria carrying 35S::GFP:SIMK construct were used for transient transformation of N. benthamiana leaves and for further stable transformation into alfalfa RSY L1 plants. Transgenic plants were regenerated through somatic embryogenesis and cultivated in the culture chamber at above‐described conditions. Fluorescence signals were observed in N. benthamiana epidermal leaf cells and in alfalfa plant organs using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope LSM710 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with Plan‐Apochromat 20×/0.8 (Carl Zeiss, Germany), and Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope LSM880 with Airyscan (Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with Plan‐Apochromat 20×/0.8 (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Samples were imaged with 488 nm excitation laser line and appropriate detection range for GFP emission. Image post‐processing was done using ZEN 2010 software.

Fixation and immunolabelling of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs in fixed alfalfa roots and nodule sections

Immunolocalization of GFP‐tagged SIMK and pERK in root whole mounts of transgenic plants carrying 35S::GFP:SIMK construct (GFP‐SIMK L5) was done as described previously (Tichá et al., 2020). For root tip samples, a double‐immunolabelling with mouse anti‐GFP (Abcam) and rabbit anti‐phospho‐p44/42 (Cell Signaling, Netherlands) primary antibodies at 1:100 and 1:400 dilution, respectively, in 2.5% (w/v) BSA in PBS was performed. To improve antibody penetration, vacuum pump was used (3 × 5 min), followed by incubation at 4°C overnight. Samples were then sequentially incubated with secondary antibody solutions. Firstly, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti‐mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, USA) diluted 1:500 in 2.5% (w/v) BSA in PBS was used for incubation for 2h at 37°C. After extensively washing with PBS and subsequent blocking [5% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 20 min], samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti‐rabbit secondary antibody (Abcam, UK) diluted 1:500 in 2.5% (w/v) BSA in PBS. Nuclei were counterstained with 1 µg/ml DAPI.

For immunolabelling of nodule sections, mature nodules were excised from alfalfa RSY L1 roots, transferred sequentially to small glass Petri dish with fixative solution (composition described previously by Kitaeva et al., 2016) and cut into several thin longitudinal sections with sharp razor blade. Hand‐cut nodules were transferred to plastic baskets with mesh in well plate containing fresh fixative solution and fixed using vacuum pump (6 × 15 min). Nodule sections were subsequently incubated in fixative solution for 1h at RT, followed by incubation at 4°C overnight. Nodule sections were washed (3 × 20 min) in microtubule stabilizing buffer [MTSB; 50 mM PIPES, 5 mM MgSO4 × 7H2O and 5 mM EGTA, pH 6.9] and 2 × 10 min in phosphate‐buffered saline [PBS; 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 6.5 mM Na2HPO4 × 2H2O, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.3]. Sections were incubated (3 × 5 min) in reduction solution [0.05 % (w/v) sodium borohydride (NaBH4) in PBS] and washed in PBS (3 × 5 min). To minimize unspecific antibody binding, sections were incubated for 1h at RT in blocking solution [5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS]. Sections were simultaneously incubated in 2.5% (w/v) BSA in PBS with rabbit anti‐AtMPK6 (Sigma, Life Science, USA) primary antibody at 1:750 dilution for SIMK localization and mouse anti‐phospho‐p44/42 (Cell Signaling, Netherlands) primary antibody at 1:400 dilution. To improve primary antibodies penetration, air was pumped out (3 × 5 min) using vacuum pump, followed by incubation at 4°C overnight. Next day, sections were put for 1h at 37°C. The excess of primary antibodies was rinsed out with PBS (5 × 10 min), followed by sections blocking (5% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 20 min at RT). Sections were then sequentially incubated in 2.5% (w/v) BSA in PBS with appropriate Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibody. Firstly, sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 647 rabbit anti‐mouse secondary antibody (Abcam) at 1:500 dilution for 2h at 37°C. Sections were washed in PBS (5 × 10 min) and blocked [5% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 20 min at RT]. Sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti‐rabbit (Abcam) secondary antibody at 1:500 dilution for 2h at 37°C. Sections were washed in PBS (5 × 10 min) and stained with 1 µg/ml DAPI in PBS for nuclei and bacteria visualization.

Immunolabelled samples of roots and nodules were mounted in antifade mounting medium [0.1% (w/v) paraphenylenediamine in 90% (v/v) glycerol buffered with 10% (v/v) PBS at pH 8.2 ‐ 8.6] and used for microscopy. Microscopic analysis was performed with a Zeiss LSM710 platform (Carl Zeiss, Germany) or Zeiss LSM880 Airyscan equipped with a 32 GaAsP detector (Carl Zeiss, Germany), using excitation laser lines at 405 nm for DAPI, 488 nm for Alexa Fluor 488, 561 nm for Alexa Fluor 555 and 631 nm for Alexa Fluor 647. The image post‐processing was done using ZEN 2014 software, and final figure plates were obtained using Photoshop 6.0/CS and Microsoft PowerPoint software.

Quantitative colocalization analysis

Quantitative colocalization analysis of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs was performed on immunolabelled hand‐cut nodules of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants induced by inoculation with S. meliloti. Images used for colocalization analysis were acquired at the same imaging conditions by confocal laser scanning microscope LSM710 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) with Plan‐Apochromat 40×/1.4 Oil DIC M27 objective, operated by Zeiss ZEN 2011 software (Black version). Images were acquired with the same laser attenuation values for both laser lines, and the thickness of individual optical sections was optimized according to Nyquist criteria in ZEN software. The pinhole sizes for both pseudocolored red (555/565 nm for excitation/emission) and pseudocolored yellow (652/668 nm for excitation/emission) channels were matched, and range of detection was appropriately adjusted to ensure separation of both emission wavelengths. Colocalization of SIMK with phosphorylated MAPKs in cells of infection, symbiotic and senescent nodule zones was strictly analyzed from single confocal optical sections, and in total, three independent optical sections per zone were analyzed using the colocalization tool of Zen 2011 software (Black version). Background threshold was adjusted by crosshairs setting according to Costes et al. (2004). Colocalization data were calculated from specific regions of interests (ROIs) selected manually by the drawing rectangle in cells of infection, symbiotic and senescent nodule zones, and from particular spots in the same cells outlined manually using the closed Bezier tool of the ZEN 2011 software (Black version). Data were displayed in intensity‐corrected scatter plot diagrams. Intensity correlation of colocalizing pixels was expressed by Mander’s overlap coefficient according to Manders et al. (1993).

Statistical analysis

All statistical parameters of the performed experiments are included in the figures or figure legends, number of samples (N), type of statistical tests and methods used, statistical significance denoted by lowercase letters or stars. Statistics was calculated in SigmaPlot11.0 using Kruskal–Wallis one‐way analysis of variance on ranks (Dunn’s method) if normality and/or equal variance failed or using one‐way analysis of variance (Duncan's method) or two‐way analysis of variance (Holm–Sidak method) if normality and equal variance passed. Different lowercase letters indicate statistical significance between treatments (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis using t‐test was done in Microsoft Excel, and statistical significance between treatments is indicated by asterisks (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Data (and software) accessibility

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.Š. (jozef.samaj@upol.cz).

Author contributions

M.H., I.L., K.H., P.D., O.Š., M.T. and M.O. performed experiments. M.H., I.L., K.H., P.D., D.N., H.B. and K.N. evaluated data, and I.L. performed statistical analyses. J.Š. provided infrastructure and coordinated the whole project. J.Š. and M.O. helped to plan experiments and contributed to data interpretation. M.H. and I.L. drafted the manuscript which was finally edited by J.Š. and M.O.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Localization of SIMK during infection thread formation.

Figure S2 Nodule formation in alfalfa plants after inoculation with Sinorhizobium meliloti‐mRFP.

Figure S3 Root system development and nodulation in plants of alfalfa lines grown in soil.

Figure S4 Shoot and leaf phenotypes in plants of alfalfa lines grown in soil.

Figure S5 Expression pattern of35S::GFP:SIMK construct after transient transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells.

Figure S6 Subcellular localization of GFP‐SIMK in stable transformed alfalfa plants using confocal and Airyscan CLSM.

Figure S7 Whole mount immunofluorescence localization of GFP‐SIMK in stable transformed root tip of alfalfa by Airyscan CLSM.

Figure S8 Quantitative colocalization analysis of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs in cells of the infection zone in immunolabeled hand‐sectioned nodule, induced after Sinorhizobium meliloti inoculation of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants.

Figure S9 Quantitative colocalization analysis of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs in cells of the infection zone in immunolabeled hand‐sectioned nodule, induced after Sinorhizobium meliloti inoculation of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants.

Figure S10 Quantitative colocalization analysis of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs in cells of the symbiotic zone in immunolabeled hand‐sectioned nodule, induced after Sinorhizobium meliloti inoculation of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants.

Figure S11 Quantitative colocalization analysis of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs in cells of the symbiotic zone in immunolabeled hand‐sectioned nodule, induced after Sinorhizobium meliloti inoculation of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants.

Figure S12 Quantitative colocalization analysis of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs in cells of the senescent zone in immunolabeled hand‐sectioned nodule, induced after Sinorhizobium meliloti inoculation of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants.

Figure S13 Quantitative colocalization analysis of SIMK and phosphorylated MAPKs in cells of the senescent zone in immunolabeled hand‐sectioned nodule, induced after Sinorhizobium meliloti inoculation of alfalfa control RSY L1 plants.

Table S1 Primers used for MultiSite GateWay® cloning and quantitative real‐time qPCR.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by ERDF project ‘Plants as a tool for sustainable global development’ No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000827. The Alexander von Humboldt Foundation supported the visit of HB and KN.

Hrbáčková, M. , Luptovčiak, I. , Hlaváčková, K. , Dvořák, P. , Tichá, M. , Šamajová, O. , Novák, D. , Bednarz, H. , Niehaus, K. , Ovečka, M. and Šamaj, J. (2021) Overexpression of alfalfa SIMK promotes root hair growth, nodule clustering and shoot biomass production. Plant Biotechnol. J., 10.1111/pbi.13503

References

- Aung, B. , Gruber, M.Y. , Amyot, L. , Omari, K. , Bertrand, A. and Hannoufa, A. (2015) Micro RNA 156 as a promising tool for alfalfa improvement. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F. , Ovečka, M. and Hirt, H. (2000a) Salt stress induces changes in amounts and localization of the mitogen‐activated protein kinase SIMK in alfalfa roots. Protoplasma, 212, 262–267. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F. , Salaj, J. , Mathur, J. , Braun, M. , Jasper, F. , Šamaj, J. , Chua, N. H. et al. (2000b) Root hair formation: F‐actin‐dependent tip growth is initiated by local assembly of profilin‐supported F‐actin meshworks accumulated within expansin‐enriched bulges. Dev. Biol. 227, 618–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekešová, S. , Komis, G. , Křenek, P. , Vyplelová, P. , Ovečka, M. , Luptovčiak, I. and Šamaj, J. (2015) Monitoring protein phosphorylation by acrylamide pendant Phos‐Tag™ in various plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biazzi, E. , Nazzicari, N. , Pecetti, L. , Brummer, E.C. , Palmonari, A. , Tava, A. and Annicchiarico, P. (2017) Genome‐wide association mapping and genomic selection for alfalfa (Medicago sativa) forage quality traits. PLoS One, 12, e0169234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögre, L. , Calderini, O. , Binarova, P. , Mattauch, M. , Till, S. , Kiegerl, S. , Jonak, C. et al. (1999) A MAP kinase is activated late in plant mitosis and becomes localized to the plane of cell division. Plant Cell, 11, 101–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, C. , Camut, S. , Malpica, C.A. , Truchet, G. and Rosenberg, C. (1990) Rhizobium meliloti genes encoding catabolism of trigonelline are induced under symbiotic conditions. Plant Cell, 2, 1157–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brussel, A.A. , Bakhuizen, R. , van Spronsen, P.C. , Spaink, H.P. , Tak, T. , Lugtenberg, B.J. and Kijne, J.W. (1992) Induction of pre‐infection thread structures in the leguminous host plant by mitogenic lipo‐oligosaccharides of Rhizobium . Science, 257, 70–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubb, M.R. , Spector, I. , Beyer, B.B. and Fosen, K.M. (2000) Effects of jasplakinolide on the kinetics of actin polymerization an explanation for certain in vivo observations. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5163–5170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano‐Anollés, G. and Bauer, W.D. (1988) Feedback regulation of nodule formation in alfalfa. Planta 175, 546–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano‐Anollés, G. , Paparozzi, E.T. and Gresshoff, P.M. (1991) Mature nodules and root tips control nodulation in soybean. J. Plant Physiol. 137, 389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale, F. , Jonak, C. , Ligterink, W. , Niehaus, K. , Boller, T. and Hirt, H. (2000) Differential activation of four specific MAPK pathways by distinct elicitors. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36734–36740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale, F. , Meskiene, I. , Ouaked, F. and Hirt, H. (2002) Convergence and divergence of stress‐induced mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathways at the level of two distinct mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinases. Plant Cell, 14, 703–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carro, L. , Veyisoglu, A. , Riesco, R. , Spröer, C. , Klenk, H.P. , Sahin, N. and Trujillo, M.E. (2018) Micromonospora phytophila sp. nov. and Micromonospora luteiviridis sp. nov., isolated as natural inhabitants of plant nodules. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68, 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casse, F. , Boucher, C. , Julliot, J.S. , Michel, M. and Denarie, J. (1979) Identification and characterization of large plasmids in Rhizobium meliloti using agarose gel electrophoresis. Microbiology 113, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. , Zhou, B. , Duan, L. , Zhu, H. and Zhang, Z. (2017) MtMAPKK4 is an essential gene for growth and reproduction of Medicago truncatula . Physiol. Plant. 159, 492–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. , Zhu, H. , Ke, D. , Cai, K. , Wang, C. , Gou, H. , Hong, Z. et al. (2012) A MAP kinase kinase interacts with SymRK and regulates nodule organogenesis in Lotus japonicus . Plant Cell, 24, 823–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha, C. and Doerner, P. (2020) The impact of the rhizobia–legume symbiosis on host root system architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 3902–3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costes, S.V. , Daelemans, D. , Cho, E.H. , Dobbin, Z. , Pavlakis, G. and Lockett, S. (2004) Automatic and quantitative measurement of protein‐protein colocalization in live cells. Biophys. J . 86, 3993–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristina, M.S. , Petersen, M. and Mundy, J. (2010) Mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 621–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delves, A.C. , Mathews, A. , Day, D.A. , Carter, A.S. , Carroll, B.J. and Gresshoff, P.M. (1986) Regulation of the soybean‐Rhizobium nodule symbiosis by shoot and root factors. Plant Physiol. 82, 588–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic, M.A. , Mohd‐Radzman, N.A. and Imin, N. (2015) Small‐peptide signals that control root nodule number, development, and symbiosis. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 5171–5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efroni, I. , Eshed, Y. and Lifschitz, E. (2010) Morphogenesis of simple and compound leaves: A critical review. Plant Cell, 22, 1019–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fåhreus, G. (1957) The infection of clover root hairs by nodule bacteria studied by a simple glass slide technique. Microbiology, 16, 374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautrat, P. , Laffont, C. and Frugier, F. (2020) Compact Root Architecture 2 promotes root competence for nodulation through the miR2111 systemic effector. Curr. Biol. 30, 1339–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.Y. , Xiang, Q.W. , Wagner, C. , Zhang, D. , Xie, Z.P. and Staehelin, C. (2016) The type 3 effector NopL ofSinorhizobium sp. strain NGR234 is a mitogen‐activated protein kinase substrate. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 2483–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, R. , Xiao, T.T. and Reinhold‐Hurek, B. (2016) What does it take to evolve a nitrogen‐fixing endosymbiosis? Trends Plant Sci. 21, 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]