Abstract

We present the first mathematical model of flow-mediated primary hemostasis in an extravascular injury which can track the process from initial deposition to occlusion. The model consists of a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe platelet aggregation (adhesion and cohesion), soluble-agonist-dependent platelet activation, and the flow of blood through the injury. The formation of platelet aggregates increases resistance to flow through the injury, which is modeled using the Stokes–Brinkman equations. Data from analogous experimental (microfluidic flow) and partial differential equation models informed parameter values used in the ODE model description of platelet adhesion, cohesion, and activation. This model predicts injury occlusion under a range of flow and platelet activation conditions. Simulations testing the effects of shear and activation rates resulted in delayed occlusion and aggregate heterogeneity. These results validate our hypothesis that flow-mediated dilution of activating chemical adenosine diphosphate hinders aggregate development. This novel modeling framework can be extended to include more mechanisms of platelet activation as well as the addition of the biochemical reactions of coagulation, resulting in a computationally efficient high throughput screening tool of primary and secondary hemostasis.

Keywords: mathematical modeling, flows in porous media, mathematical biology, blood clotting, hemostasis

AMS subject classifications: 92B05, 76S99, 93A30

1. Introduction.

Hemostasis is the first line of defense upon vascular injury (either a disruption in the subendothelial lining or a breach in the vessel wall) whereby a blood clot (thrombus) forms to prevent the loss of blood [46, 47]. The hemostatic response consists of two intertwined processes: platelet aggregate formation and coagulation [14, 33]. These processes are triggered when reactive proteins either in the extravascular matrix or on the subendothelium are exposed to the blood plasma. Platelets are blood cells that circulate in the human vasculature in their unactivated state and mediate the biophysical and biochemical aspects of thrombus formation. These cells become activated when in contact with collagen in the subendothelium or with chemical agonists in the plasma. Activated platelet surfaces support coagulation reactions that produce the enzyme thrombin. Thrombin in turn cleaves the soluble blood protein fibrinogen into fibrin monomers, which polymerize to form a gel. This gel provides structure and stability to the aggregate. The size and structure of an aggregate as well as the time it takes the aggregate to form, depend not only on platelet function and coagulation, but on the local hydrodynamic environment. Blood flowing in a vessel is subject to a pressure difference across the vascular wall and any disruption of the wall can lead to loss of blood, which greatly affects the delivery and removal of platelets, chemical agonists, and coagulation proteins.

Upon extravascular injury, two important reactive proteins are exposed: collagen and tissue factor (TF). Blood cells and plasma containing coagulation proteins leak from the vessel into the extravascular space. Platelets flow into the injury and begin to deposit; they adhere to the collagen, and bind other insoluble agonists, which in turn triggers the activation of key integrins on platelet surfaces [2, 4, 5, 47]. The soluble agonist adenosine diphosphate (ADP), which is released from platelet granules into the fluid by activated platelets themselves, interacts with platelet receptors P2Y1 and P2Y12 to additionally trigger exposure of surface integrins [3, 18, 32]. This effect of soluble agonist ADP is an example of activation without contact with the subendothelial matrix [1, 26]. Activated platelets provide surfaces to which more platelets can cohere, enhancing the growth of the platelet aggregate to prevent further blood leakage. Platelet aggregate formation depends strongly on both the hydrodynamic environment and the formation and dissociation of bonds that enable platelet adhesion and cohesion. Failure of any of the processes that mediate platelet aggregation, under a variety of flow conditions, can result in significant blood loss.

In recent years there has been an increased focus on understanding the molecular basis of bleeding disorders and associated variability in levels of key coagulation factors, platelet count, and insoluble proteins. Most clinical assays used to assess bleeding risk are performed under static conditions. However, data have shown that hydrodynamic forces affect platelet aggregation and fibrin formation, both key components of a thrombus [30]. This has motivated the development of mathematical models of hemostasis that integrate platelet function, coagulation, and hemodynamics to predict bleeding risk based on measurable biochemical and biophysical factors.

Our group has developed mathematical models of flow-mediated coagulation in an intravascular injury setting to predict regulatory mechanisms of hemostasis and thrombosis [11, 13, 15, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28]. These models use a continuum approach and express dynamics using differential equations. Our ordinary differential equation (ODE) models of thrombosis employ a well-mixed compartment assumption that accounts for transport by flow and diffusion using simplified mass-transfer coefficients. Other models fully account for spatial variations and transport which simulate small vascular injuries under flow [23, 25] through the use of partial differential equations (PDEs). Despite the numerous mathematical models of flow-mediated intravascular blood clotting, there are relatively few models of extravascular thrombus formation. To our knowledge, the model we present here is the first mathematical model to incorporate key biophysical and biochemical mechanisms of primary hemostasis in the framework of an extravascular injury. Our model is based on ODEs and is validated and calibrated using analogous experimental (Appendix A.2) and PDE (Appendix A.4) models, respectively [8, 39].

One of the many contributions of this model is its computational efficiency, which allows for systematic exploration of large sets of parameters that would be impossible to resolve using the spatial PDE model or an experimental model. Parameters that contribute to bleeding include, but are not limited to, injury size, hemodynamics, vessel wall composition, and the anatomy of the adjacent perivascular and extravascular spaces. An experimental platform for studying hemostasis with a focus on collagen-TF induced thrombus formation within a model vascular wall was previously presented in [39]. This experimental model is an in vitro microfluidic flow assay (MFA) we refer to as the “bleeding chip.” Our mathematical model design is inspired by the specific “H”-geometry that is characteristic of the bleeding chip and will be used in the future to quantify variability of MFAs and identify components of the clotting system that underscore the known phenotypic variability in certain bleeding disorders [31]. The overall goal of this work is to create an efficient, mechanistic modeling framework that can be used for high-throughput screening of the blood clotting process and that enables mathematically driven, but testable, hypotheses.

The paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we present a system of ODEs that describe platelet accumulation, soluble-agonist-dependent platelet activation, and blood flow through the injury. Flow and transport calculations are calibrated using flow rates and concentrations of soluble agonist ADP from the PDE model shown in section 3. Section 3 additionally contains results of platelet aggregation model validation with MFA occlusions times and calibration results with PDE occlusion outputs. Also in section 3 are simulations of the ODE model testing the effects of flow and platelet activation rates on aggregation metrics. The results therein suggest that reducing the rate of platelet activation significantly modifies primary hemostasis. Last, flow-mediated dilution of ADP is shown to hinder or even stop aggregate development. Section 4 provides details of the limitations and proposed extensions of this novel mathematical modeling framework, underscoring the model’s versatility and future use.

2. Mathematical model.

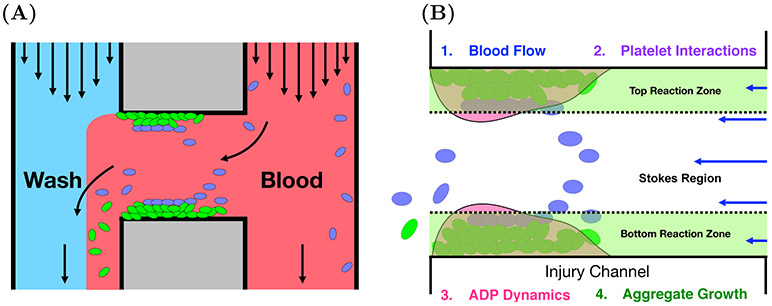

We model the situation where blood flows through a hole in the vessel wall into the extravascular space. In this scenario, a disruption in the endothelial layer occurs and exposes collagen to the blood. Platelets are transported to the injury by flow and adhere to collagen. This in turn activates them, leading to the release of platelet agonist ADP and the recruitment of additional platelets that cohere and form an aggregate. The model incorporates the flow of blood through an H-geometry to mimic the bleeding chip, as described above and as depicted in Figure 1(A), and it explicitly models aggregate formation under local fluid dynamic conditions. Components of the model include descriptions of the blood flow through the bleeding chip geometry and the injury channel as well as the platelet interactions, soluble agonist ADP dynamics, and aggregate growth (see Figure 1(B)).

FIG. 1.

(A) Bleeding chip. Blood and wash buffer are introduced into the two vertical channels of the bleeding chip. A horizontal injury channel connects the two vertical channels, where platelet deposition occurs [39]. Green and blue ovals represent activated and unactivated platelets, respectively. (B) Mathematical model components of platelet aggregation in the horizontal injury channel of the bleeding chip. 1. Pressure driven flow with a Stokes–Brinkman layered velocity calculation. 2. Platelets’ states (mobile/bound and unactivated/activated), mediated by activating chemical concentration [ADP], determines adhesion to injury and cohesion to other platelets. (3) ADP is released from, bound platelets and is subject to transport by both advection and diffusion. (4) Aggregate growth is influenced by changes in thickness and porosity and feedbacks on blood flow due to increased frictional resistance.

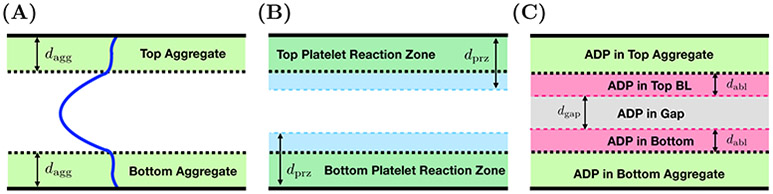

Each component of the model involves a number of compartments which correspond to different spatial portions of the injury channel. Two compartments are defined by the platelet aggregates on the bottom and top walls of the channel as shown in Figure 2(A). Others are defined in terms of diffusive boundary layers for platelets (Figure 2(B)) and the activating chemical ADP (Figure 2(C)). There are diffusive boundary layers associated with each of the aggregates. Last, there is a compartment representing the “gap” between the boundary layers associated with the bottom and top aggregates shown in Figure 2(C). The two compartments of the platelet model and the five compartments describing the ADP model are defined precisely below. The model unknowns are number densities for three populations of platelets and the concentration of ADP in the various compartments; the volume fraction of bound platelets in and the thickness of each of the aggregate compartments, and the fluid velocity profile across the channel. The velocity profile is the only fully spatially dependent variable in the model; it is used in defining the diffusive boundary layers and in defining advective fluxes of fluid, platelets, and ADP into and out of the various compartments.

FIG. 2.

Spatial compartments of model. Each panel shows spatial compartments associated with the horizontal injury channel of the bleeding chip. (A) Two aggregate (Brinkman) compartments with thickness dagg with a volume of Vagg and the Stokes region. (B) Two aggregate compartments and the platelet boundary layers (PBLs), together defining platelet reaction zones (PRZs) with thicknesses of dprz and volumes Vprz describe a two compartment platelet model. (C) Two aggregate compartments and the boundary layers associated with ADP (ABL) with thicknesses dabl. The remaining compartment in the bulk of the Stokes region is denoted as the gap and has thickness dgap. These layers define a five compartment ADP model.

2.1. Fluid dynamics.

The mathematical representation of flow in this geometry is nonstandard. Below, we describe how we model pressure-driven flow in the injury channel and incorporate hindrance by the porous, growing aggregate. The flow of blood through the bleeding chip is described in subsection 2.1.1. Output from this calculation determines the inputs used in the Stokes–Brinkman calculation of the flow inside of the injury channel where aggregates form. The resulting velocity profile is used to calculate the increased resistance in the injury channel and therefore alters the pressure drop P1 – P2. Details of this calculation are found in subsection 2.1.2.

2.1.1. Fluid through extravascular injury domain.

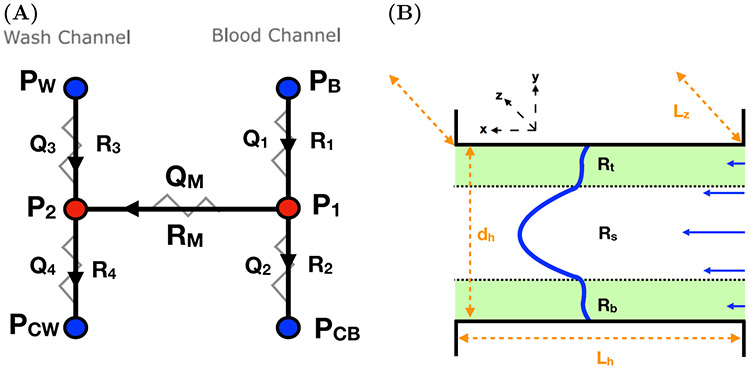

The bleeding chip contains two vertical channels (L × w × Lz) = (10 mm × 100 μm × 60 μm), consisting of a “blood” channel and a “wash” channel, connected by a horizontal “injury” channel (Lh × dh × Lz) = (150 μm × 20 μm × 60 μm), which forms an H-shaped geometry (Figure 1(A)). The flow rates and/or pressures at the inlets and outlets are prescribed and blood flows into the device through the blood channel. A fraction of the blood exits through the outlet of the blood channel. The remaining blood makes its way through the injury channel (from right to left) and exits through the outlet of the injury channel into the wash channel. Two hydraulic resistors in series describe the flow in each of the blood and wash channels and a connecting resistor in parallel describes the flow in the injury channel (Figure 3(A)). The resistances R1, R2, R3, R4 are input parameters; the resistance RM is obtained from our calculation of the flow in the injury channel as explained in the next section. By solving the linear system of equations for this HC as shown in Appendix A.1, we determine the pressure gradient Gh = (P1 – P2)/Lh across the injury channel. The resulting pressure gradient Gh is used to determine the flow velocity through the injury channel.

FIG. 3.

(A) Hydraulic circuit (HC) system describing flow through the bleeding chip. Quantities in blue are inputs while quantities in red are the desired output determined by solving the system of equations in Appendix A.1. (B) A schematic of the domain filled with Brinkman regions green representing the bottom Rb and top aggregates Rt and a Stokes region Rs with a depth of Lz, width of dh, and a length of Lz denoted in orange. Flow moves from right to left and the resulting velocity profile is depicted in blue.

2.1.2. Fluid through injury.

The calculation of the fluid velocity profile at each time proceeds as follows. We assume that we know the current thicknesses db and dt of the aggregate compartments (see Figure 2(A)), and the volume fractions of bound platelets and of the aggregates. Define the intervals Rb = {0 ≤ y ≤ db}, Rs = {db ≤ y ≤ dh – dt}, and Rt = {dh – dt ≤ y ≤ dh}. Given that the Reynolds number in the injury channel of the bleeding chip is Re ≈ 0.0283 << 1 as calculated in Table 4, the unidirectional flow in the x-direction for y ∈ Rs is modeled by the Stokes equations, and the flows for y ∈ Rb and y ∈ Rt are modeled by the Brinkman equations, as we have done in previous studies [22, 23]. These are the Stokes equations modified by the inclusion of a Brinkman drag term among the forces acting on the fluid. The fluid dynamics equations are

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

where we assume the density of the fluid is ρ = 1 g/cm3 and the Brinkman coefficients αb and αt are functions of and , respectively. These differential equations are supplemented with no-slip boundary conditions ub(0) = 0 and ut(dh) = 0 as well as matching conditions at the edge of each aggregate compartment. The matching conditions are that the velocity u and the shear stress are continuous for all y.

Table 4.

Parameters that characterize the geometry and flow, mass transfer, and reaction regimes in the injury channel. The average blood velocity U, ν kinematic viscosity, D diffusivity of platelets, γ wall shear rate. **Dh, hydraulic diameter [2dhLz/(dh + Lz)].

| Parameters | Expression | Value | Constants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect ratio | dh/Lz | 0.333 | dh = 20 μm, Lz = 60 μm |

| Relative injury size | Lh/dh | 7.5 | Lh = 150 μm |

| Reynolds number (Re) | Udh/ν | 0.0283 | ν =1.5 × 10−5m2/s, U = 2.13 × 10−2m/s |

| Entrance length (Le) | 0.05 ReDh | 0.0425 μm | Dh = 30 μm |

| Peclet number (Pe) | 6.4 × 103 | γ = 2400 s−1, Dp = 2.5 × 10−5 m2/s | |

| Mass transfer coeff. (km) | (D2ρ/8Lh)1/3 | 8.2 × 10−6 m/s | ρ = 1060 kg/m3 |

The pressure gradient in the injury channel is assumed to be independent of y, so it is a constant Gh determined from the circuit calculation found in Appendix A.1.

To relate the volume fraction of bound platelets , to the permeability (1/αb, 1/αt) of the Brinkman layers, the functions αb and αt are defined with the widely used Kozeny–Carman relation [29],

and CK is a fitted parameter whose estimation is discussed in Appendix C.1.1. Because of the linearity of the differential equations (2.1)-(2.3) above, the velocity in each compartment is a linear combination of exponential functions of y, with a total of six unknown coefficients. We determine these coefficients by solving the linear system of equations corresponding to the two boundary conditions and the four matching conditions (Appendix B). For later convenience, we define the velocity as u(y) = (ub(y) for y ∈ Rb, us(y) for y ∈ Rs, ut(y) for y ∈ Rt).

In practice, we first determine a preliminary velocity field by taking Gh = 1. This allows us to calculate for use in the circuit analysis described in Appendix A.1. Once the actual Gh is known from the circuit analysis, the velocity is obtained by multiplying the preliminary velocity by Gh. The velocity profile and the upstream concentration of platelets dictate the transport of mobile platelets and ADP to and from the site of injury. Platelets and ADP both move by advection and diffusion. For ADP, diffusion is Brownian. For platelets, diffusion is used as a model for the effects on platelet motion of local flow disturbances generated by the complex motions of the deformable red blood cells that make up approximately 40% of the bloods volume [41]. The diffusion of platelets and ADP to and from the walls/growing aggregates define the regions in which platelet activation, adhesion, and cohesion can occur. For clarity and brevity, all descriptions of the dynamics of platelets, soluble agonist ADP, and aggregate growth will be associated with the bottom wall of the injury, although there are similar equations for dynamics near the top wall. We therefore will temporarily drop the subscript b that denotes “bottom.”

2.2. Platelets.

We consider a three species model of platelet aggregation involving the number densities (plt/μL) of unactivated and activated mobile platelets Pm,u, Pm,a in the PRZ and bound platelets Pb,a in the growing aggregate region. The PRZ is the union of the aggregate region and the adjacent PBL (Figure 2(B)). Note the superscripts m and b are associated with a platelet’s state of mobility (mobile or bound) and the superscripts u and a indicate its state of activation (unactivated or activated). The first two platelet populations are mobile and are subject to the effects of flow within and (sufficiently) near the growing aggregate: Pm,u enter upstream and leave downstream whereas Pm,a only leave downstream because we have assumed that no mobile, activated platelets come into the injury channel from upstream. Pm,u can adhere to the wall and therefore become bound and activated. Activated, mobile platelets can either adhere to the wall or cohere to Pb,a. In addition to adhesion, Pm,u are activated by exposure to the soluble agonist ADP. Platelet adhesion and cohesion increase the volume of bound platelets in the aggregate and consequently increase the thickness and volume fraction of bound platelets of each aggregate. They thus indirectly affect the delivery/removal of mobile platelets by flow.

2.2.1. Coupling flow to platelet transport.

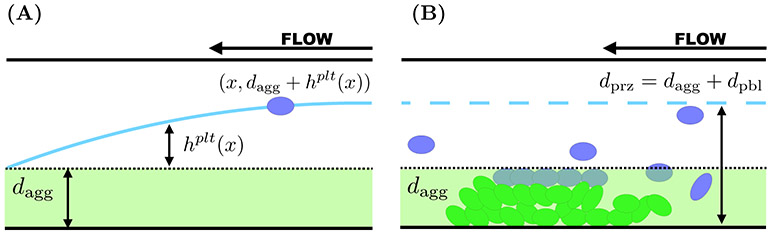

Similarly to what we did in [15, 21], we approximate the effects of diffusive motion in conjunction with advective transport by defining appropriate boundary layers, the regions from inside of which platelets can reach the growing aggregate before being carried away downstream. We estimate the thickness of the boundary layer as follows (our estimates agree very well with those in [7]). We denote the thickness of the bottom aggregate as dagg and we define a PBL as follows. For each x ∈ (0, Lh), let hplt(x) be defined by equating the typical time it would take a platelet at location (x, dagg + hplt(x)) to diffuse to the edge of the aggregate with the time it takes that platelet to be carried to the outlet of the injury by the flow:

Solving for hplt(x) defines a PBL for platelets as shown in Figure 4(A). Because the platelet has a nonvanishing size, we modify our definition of the top edge of the PBL to dpbl(x) = min(hplt(x), dplt), where dplt is the diameter (≈ 2μm) of a platelet. We are interested in the advective flux of platelets into and out of this compartment, shown in Figure 4(B). Transport into this compartment at the inlet of the injury channel depends on the inlet platelet concentration and the fluid velocity u(y) for dagg < y < dagg + dpbl(0). While the boundary layer narrows between the inlet and the outlet of the injury channel, platelets can leave the boundary layer by advection for this same range of y values. Hence, letting dpbl = dpbl(0), we define the PBL compartment associated with the bottom aggregate to be those points in the injury channel with dagg < y < dagg + dpbl. For the bottom aggregate, the PRZ is defined by 0 ≤ y ≤ dprz = dagg + dpbl. A similar construction is used to define the PBL compartment adjacent to the aggregate on the top injury channel wall.

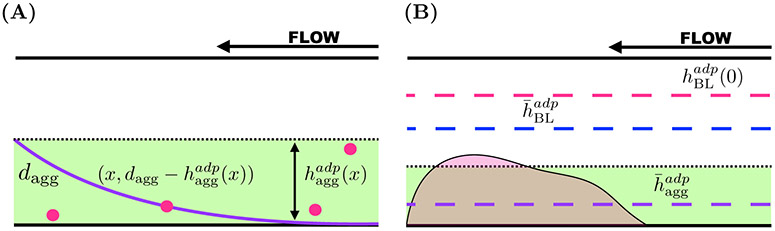

FIG. 4.

Boundary layers associated with the transport of platelets. Blood flows from right to left, entering the injury channel at x = 0 and exiting downstream at x = Lh. (A) Consider a platelet at the position (x, dagg + hplt(x)). The distance it must travel to reach the edge of the growing aggregate is hplt(x) (cyan) and the thickness of the aggregate is denoted as dagg. (B) The PBL thickness at the entrance of the injury channel hplt(0) (cyan, dashed) defines the reaction zone for platelet interactions in that dprz = dagg+dpbl, where dphl = min(hplt(0), dse) and dse = dplt = 2 μm.

Figure 4(B) is drz = dagg + min(hplt(0), dse), where dagg denotes the thickness of the aggregate. The fluxes of platelets and blood into and out of the injury channel are prescribed using the reaction zone thickness.

The advective transport of platelets into and out of each of the platelet compartments is hindered to a degree that depends on the fraction of each compartment’s volume that is occupied by platelets. Let θM = vplt(Pm,u + Pm,a) and θB = vpltPb,a, where vplt is the volume of an individual platelet. The quantities θM and θB are the volume fractions occupied by mobile and bound platelets, respectively. Note that bound platelets are found only in the aggregate compartments while mobile platelets can be found throughout the injury channel, but we track separately the number densities of mobile platelets in the two PRZs. To describe the transport of mobile, unactivated platelets into the injury channel, we define the quantity

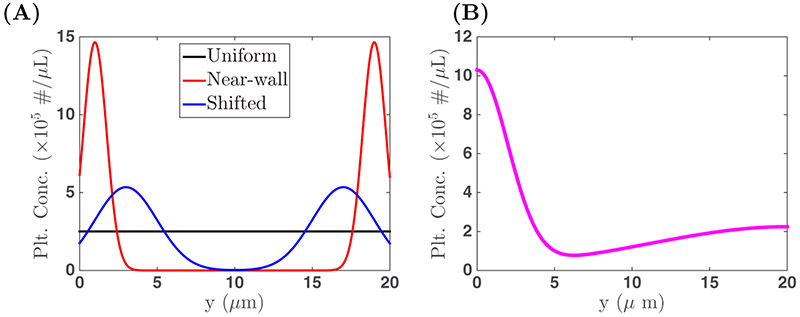

where Pup(y) is the number density of mobile, unactivated platelets at the inlet to the injury channel. In this work, we assume a uniform and constant upstream distribution Pup(y) = Pup,*, but using nonuniform distributions is straightforward (Appendix D). Note that the use of Pup,* in the model yields symmetric top and bottom aggregates. The model framework allows for asymmetric aggregate formation if Pup(y) is not symmetric and simulations found in Appendix D explore the resulting aggregates. The function W is intended to limit platelet entry and movement through the region in which the volume fraction of platelets is already high. We used the specific function

which monotonically decreases from W(0) = 1 to W(1) = 0 [23]. Therefore, there is no hindrance when the volume fraction is 0 and total hindrance as the volume fraction approaches 1. In choosing this function, we assume that the ability for mobile platelets to move into a region is only gradually impaired until θ nears θmax = 0.6 and then drops quickly. The rate (number/time) at which mobile, unactivated platelets enter the PRZ is .

We define the following quantities to describe the transport of unactivated and activated mobile platelets out of the injury channel. The rates at which these platelets leave the PRZ are and , respectively, where

The flow of blood in the injury channel is coupled to the transport of platelets into and out of the injury channel as we describe below.

2.2.2. Cohesion, adhesion, and dilution.

Platelets contribute to aggregate formation through two binding processes: adhesion and cohesion. Both unactivated and activated mobile platelets can adhere directly to the bottom or top wall of the injury channel. Mobile, activated platelets can cohere to already bound, activated platelets. Platelets are activated through direct contact with the wall or by exposure to the soluble agonist ADP. The activation state of the platelet as well as the available space both on the wall and in the developing aggregate determine which binding processes can occur.

Since adhesion requires that a platelet directly contacts the wall, we limit adhesion to those platelets within a specified distance dse from the walls. In the model, a platelet’s location relative to the walls is only known with respect to whether the platelet is inside one of the PRZs, and so we enforce this limit approximately in the adhesion rate function

where is a first order rate constant, the second term represents the accessibility of the wall, and the third term represents the porosity of the aggregate. With this function, adhesion is further limited as the volume fraction of platelets in the aggregate approaches its maximum value θmax, because platelets already bound to the wall occupy a portion of the wall space available for adhesion. Both unactivated and activated mobile platelets can adhere to the wall and hence the rate of adhesion is proportional to the adhesion rate function and the total number density of mobile platelets.

For mobile platelets to cohere to the aggregate, they must be activated and sufficiently close to activated bound platelets. As previously mentioned, activated platelets have activated integrin receptors on their surfaces that allow for αIIbβ3-fibrinogen-αIIbβ3 and αIIbβ3-vWF-αIIbβ3 bond formation. These bonds are strong, and long-lived with very small off rates. Therefore, we assume that bond breakage is negligible and do not allow for platelet detachment in this model. The rate of platelet-platelet cohesion, kcohPb,a Pm,a, depends on the second order rate constant kcoh and the number densities of bound activated platelets, Pb,a, and mobile, activated platelets Pm,a, respectively.

In addition to changing the number of bound platelets in the aggregate and the flow through the injury channel, the processes of adhesion and cohesion change the total volume of the aggregate and of the adjacent boundary layers (and therefore of the PRZs) by increasing their thicknesses. For a given number of platelets in the PRZ, an increase in that compartment’s volume results in a decrease in the number density of platelets in it—an effect we refer to as dilution. For example, the term describing this effect on mobile unactivated platelets has the form

and appears naturally in calculating the rate at which the number of these platelets in the PRZ changes.

2.2.3. Evolution equations of platelets.

Here we account for the processes described in subsections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 to derive evolution equations for the platelet number densities. Let Vprz = LhLzdprz denote the volume of the PRZ. Then the rate of change of the number of mobile, activated platelets in that reaction zone is

Applying the product rule on the left-hand side and rearranging terms, we determine that

| (2.4) |

The first and third terms describe transport and adhesion. The second term describes activation of mobile unactivated platelets by exposure to ADP. Based on similar considerations, we find evolution equations for the number densities of the other platelet species Pm,a and Pb,a:

| (2.5) |

| (2.6) |

2.3. Soluble agonist ADP.

An unactivated platelet stores quantities of ADP in its dense granules and releases this ADP into the surrounding fluid when the platelet is activated. Similarly to the treatment in [23], we assume this release occurs during the time interval 1–5 s after activation. Once released, that ADP moves by advection and diffusion within and out of the aggregate where it can activate mobile platelets. Describing these processes requires defining two boundary layers: one within the aggregate and one in the Stokes region . These boundary layers are used to define the ADP compartments shown in Figure 2(C) and the ADP concentrations tracked are those inside the aggregate [ADP]agg, in the Stokes region boundary layer [ADP]BL, and in the remaining Stokes region which we denote as [ADP]gap.

2.3.1. Boundary layer calculations.

The first boundary layer is related to ADP movement in the Stokes region after it has left the aggregate where it is released. The calculation is like that for platelets in the Stokes region as described above in subsection 2.2.1. This boundary layer is thinnest at the upstream end and widest at the downstream end. Its thickness is greater than that, hplt(x), of the PBL. This is because (i) ADP has a larger diffusivity than platelets and (ii) the choice of velocity used in the boundary layer calculation. For the platele ts, it is a velocity in the Stokes region u(dagg + hplt(x)) and for the ADP it is the (lower) velocity on the edge of the Stokes region u(dagg). Therefore, . As shown in Figure 5(B), the maximum thickness of this ABL in the Stokes region is denoted as and the average boundary layer thickness as .

FIG. 5.

Boundary layers associated with the transport of soluble agonist ADP. (A) Consider an ADP molecule at the position (x, ). The distance it must travel to reach the edge of the growing aggregate is . (B) The boundary layer thickness at the entrance of the injury channel in the Stokes region is (magenta, dashed) and defines the reaction zone for ADP interactions in that region. Both the average thickness in the Stokes region (blue, dashed) and in the growing aggregate (purple, dashed) are used to define diffusive transport from the aggregate into the Stokes region.

The second boundary layer describes ADP movement within the aggregate towards the Stokes region and requires the new calculation given in this section. We do not have a separate ADP concentration in this boundary layer; its thickness is used only in calculating the ADP concentration gradient. Consider the starting point (x, ) inside the aggregate and equate the time it takes an ADP molecule there to diffuse into the Stokes region with the time it would take it to be washed past the injured region by the flow:

We solve for the thickness and define to be the average aggregate layer thickness shown in Figure 5(B). The ABL thickness and the thickness of the growing aggregate contribute to the total thickness of the regions in which we track the ADP concentrations: [ADP]agg, [ADP]BL, and [ADP]gap.

2.3.2. ADP release and advection.

The source of ADP in this model corresponds to the release of ADP from activated, bound platelets. The rate of release is

where (Appendix C) is the total quantity of ADP released by an activated platelet, is the rate of release at an elapsed time since activation τ, and . The function R(τ) is defined as having value zero up to one second after activation, a positive bell-shaped function for the time interval 1 < τ < 5 seconds, and a peak at three seconds. The term is the number of platelets newly activated and bound in the time interval [t – τ, t – τ + dτ]. We account only for ADP release from bound activated platelets because activated platelet that do not become bound are carried downstream before they begin to release their ADP.

To facilitate our describing the advective transport of ADP out of the aggregate, the boundary layer, and the gap, we define the expressions

respectively. Then, the rates of advective transport of ADP out of the ADP compartments in the injury channel are , , and . Early on, the magnitude of the velocity and the thicknesses of the aggregate and boundary layers lead to the ordering . As the aggregate grows, the boundary layers become larger, decreasing the thickness of the gap dgap and resulting in a new ordering . If the flow is slowed sufficiently, dgap = 0 and .

2.3.3. Diffusive transport of ADP.

Diffusive transport of ADP from the aggregate into the boundary layer and into the bulk Stokes region also changes the ADP concentrations. The diffusive transport of ADP (Figure 6(A)) between the aggregate (green) and the boundary layer region (pink) and that between boundary layer and the bulk Stokes region (gray) are determined using Fick’s law [12]. Let Vabl = LhLzdabl be the volume of the ABL and ldiff be the length that determines the gradient of ADP from the aggregate to the boundary layer. As shown in Figure 6(B), this length is the distance between the edge of the boundary layer in the aggregate (purple, dashed) and the edge of the average boundary layer in the Stokes region (dashed, blue). The diffusive flux of ADP from the aggregate into the boundary layer is

and the rate of diffusion is LhLz Jdiff, where LzLh is the area of the interface between the zones, Da is the diffusion coefficient, ([ADP]agg – [ADP]BL) is the difference in ADP concentration between the aggregate and the boundary layer, and ldiff is the length used to define the gradient. Similarly, the diffusive flux of ADP from the boundary layer into the gap is

where the rate of transport flux is , ([ADP]BL – [ADP]gap) is the difference in ADP concentration, and is half the distance between the edge of the boundary layer and the center of the gap. The calibration parameters c1 and c2 are discussed in Appendix C.1.2.

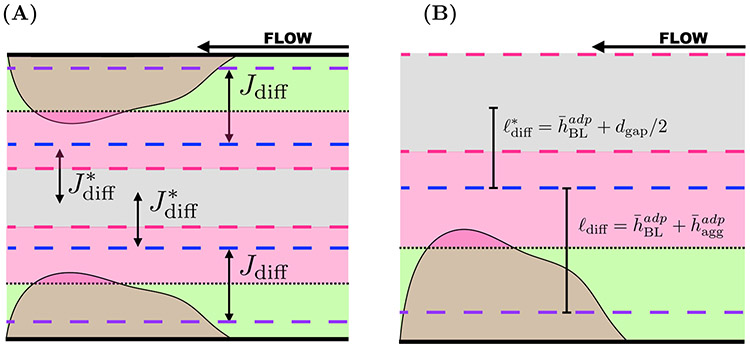

FIG. 6.

Compartment model describing diffusive transport of ADP. (A) Diffusive fluxes of ADP from the aggregates (green) to the associated boundary layers (blue) are denoted as Jdiff. ADP also diffuses from the boundary layers associated with the bottom and top aggregates to the bulk of the Stokes region (pink) with flux . The fluxes are subject to changing layer thickness that are determined by the flow velocity. (B) The dashed lines correspond to boundary layers associated with the bottom aggregate. The specified lengths ℓdiff and are used to define the gradients of ADP concentration between the aggregates and boundary layers as well as between boundary layers and bulk Stokes region, respectively.

2.3.4. Evolution equations for ADP.

Accounting for release, transport due to advection, and diffusive transport between the aggregates, boundary layer regions, and the gap in the Stokes region, the ADP concentrations in the aggregate and boundary layer region evolve according to the equations

| (2.7) |

and

| (2.8) |

The concentration of ADP in the gap changes because of diffusive transport from both the bottom and top boundary layers:

| (2.9) |

where and are the respective diffusive fluxes of ADP into the gap from the bottom and top boundary layers.

2.4. Aggregate formation.

The formation of the aggregate layer is described by its evolving thickness, dagg, and volume fraction of bound platelets, θB. To determine evolution equations for these quantities, one must consider the adhesion and cohesion events that contribute to the change in volume occupied by bound platelets. Let Vagg = LhLzdagg. The rate of change of the volume occupied by bound platelets is

Dividing by daggθB and using the product rule, and partitioning the adhesive term and cohesion term, we find the following equations:

| (2.10) |

| (2.11) |

where β, γ are assumed to have the functional forms

The partition functions β and γ are phenomenological in nature and are calibrated through PDE model (Appendix A.4) comparisons. Details are found in Appendix C.1.4. Equations (2.4)-(2.11) describe platelet dynamics, ADP dynamics, and aggregate formation associated with the bottom wall of the injury zone. There is a similar set of equations governing the concentrations of platelets species, ADP, aggregate thickness, and aggregate volume fraction associated with the top aggregate.

2.5. Platelet activation.

As noted above, once an unactivated platelet enters the PRZ it can adhere to the wall and therefore become bound and activated; it can be activated by ADP and possibly cohere to already bound platelets, or it can be carried out of the injury channel by the flow. While platelet activation is a complex process triggered by a range of stimuli and made up of an ensemble of responses [26], we focus on activation by direct adhesion to the wall and by exposure to ADP and on the resulting activation of integrin αIIbβ3 receptors and release of ADP. We discussed the activation by direct adhesion above. Activation triggered when ADP in the plasma binds to a platelet’s P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors, provides a means of activation that does not require contact with the subendothelial (SE) matrix. Because ADP stimulates this activation and additional ADP is released as a consequence, there is a positive feedback in the system involving the concentration of ADP and the transition of mobile, unactivated platelets to mobile, activated platelets. To model ADP-dependent activation, we assume that the activation trigger is a weighted average of the ADP concentrations in the aggregate and in the boundary layer. We define the rate of ADP-induced activation as

where

Here, darz = dagg + dabl is the thickness of the ADP reaction zone and [ADP]* = 1 μM. For some of our simulations, we instead considered ADP-independent platelet activation in the plasma by setting A([ADP]agg, [ADP]BL) = 1, in which case only the value of the rate constant matters. The rate constant was calibrated with the microfluidic flow assay (MFA) model (Appendix A.2) and details are found in Appendix C.1.3. Below we explore the effects of ADP-independent versus ADP-dependent activation on aggregate growth and occlusi on of the injury channel.

2.6. Numerical methods.

Simulations of the ODE model consist of solving the HC system and the Brinkman–Stokes system to determine Gh and RM, respectively. The differential equations describing the evolution of platelet species, ADP, and aggregate thickness and density are solved using the MATLAB function ode15s, which employs a variable-step, variable-order solver based on the numerical differentiation formulas of orders 1 to 5 for stiff systems [40]. During each time step of the computation, we perform the following series of updates for the unknowns.

Assume Gh = 1 and solve the linear system in Appendix B to determine u(y) and RM.

Use RM as an input parameter for the HC system in Appendix A and solve for Gh.

Scale the flow velocity using the pressure gradient update: .

Use u(y) and diffusivity constants (Dp, Da) to determine boundary layers (hplt(x), , ) for both aggregates.

Determine thicknesses of the PRZ (dprz), compartments in the Stokes region tracking ADP (dabl, dgap), and the growing aggregate (dagg) associated with the bottom and top walls.

Count the platelets activated within the previous time step and update the ADP release function σrel for each aggregate.

Update mobile platelets and ADP concentrations associated with the top and bottom aggregates and reaction zones to account for advection using the velocity profile u(y).

Update ADP concentrations to account for diffusion using ADP boundary layer thicknesses (, ) of the top and bottom ARZs and aggregates.

Update the thicknesses of the aggregates dagg, the volume fractions of bound platelets θB, and hindrance function W(θB + θM) to account for platelet adhesion and cohesion events.

Repeated until desired time.

The simulations described below were carried out for 20 minutes and all parameters values are found in Tables 1-8 with specific details in Appendices A-C. Each simulation requires ≈ 50 seconds of computational time. Information and guidance with respect to the code is available upon request from the authors.

Table 1.

Dimensions HC. See Figures 3(A)-(B) for reference.

| Length from PB to P1 (and PW to P2) | 85 μm |

| Length from P1 to PCB (and P2 to PCW) | 85 μm |

| Width of vertical channels | 100 μm |

| Length of injury channel | 150 μm |

| Width of injury channel | 20 μm |

| Depth of injury channel | 60 μm |

Table 8.

Calibrated parameters.

| Description | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Permeability constant | CK | 3.5 × 107 cm−2 |

| Platelet activation constant | 3.4 s−1 | |

| Gradient constants | c1, c2 | 1/2, 1/4 |

| Partition constant | kb | 20 |

| Partition constant | sb | 0.155 |

| Adhesion thickness | dse | 2 μm |

3. Results.

The presented mathematical model was validated and calibrated in subsection 3.1 using comparisons of ODE model output with that of analogous PDE (Appendix A.4) and MFA (Appendix A.2) models. Both validation of the flow through the injury model presented in subsection 2.1.2 and calibration of the diffusive transport of ADP (see subsection 2.3.3) were conducted as initial studies. Aggregate formation partition functions were calibrated in an iterative manner along with platelet activation rates. After completion of model validation and calibration, we investigated the variations in aggregation formation and occlusion in response to variations in flow and platelet activation as shown in subsections 3.2 and 3.3.

Since all ODE model components are dependent upon flow inputs (see subsection 2.1.1), it was important to ensure that the total flow through the injury channel in both the ODE and PDE models were the same during calibration of other model components. Preliminary calibration studies with the PDE model revealed that the pressure drop ΔP = P1 – P2 across the injury channel was not constant with respect to the y-direction. Therefore to achieve the most accurate model comparisons for each of the calibrated components, it was necessary to compute an approximation of the flow rate QPDE through the injury channel using the PDE model for the calibration simulations. This changes the second step of our numerical scheme. Specifically, we do not solve the HC system for the pressure gradient Gh. Instead, we assume

where db, dt and , are the thicknesses and densities of the bottom and top aggregates, respectively. The effective length of the channel is as described in Appendix A.1. Details regarding QPDE are found in Figures 7(A)-(B) and Appendix A.3. Note that the ODE model is not dependent on the use of the PDE flow map and the use of the ODE model beyond the scope of this work is independent of PDE model results.

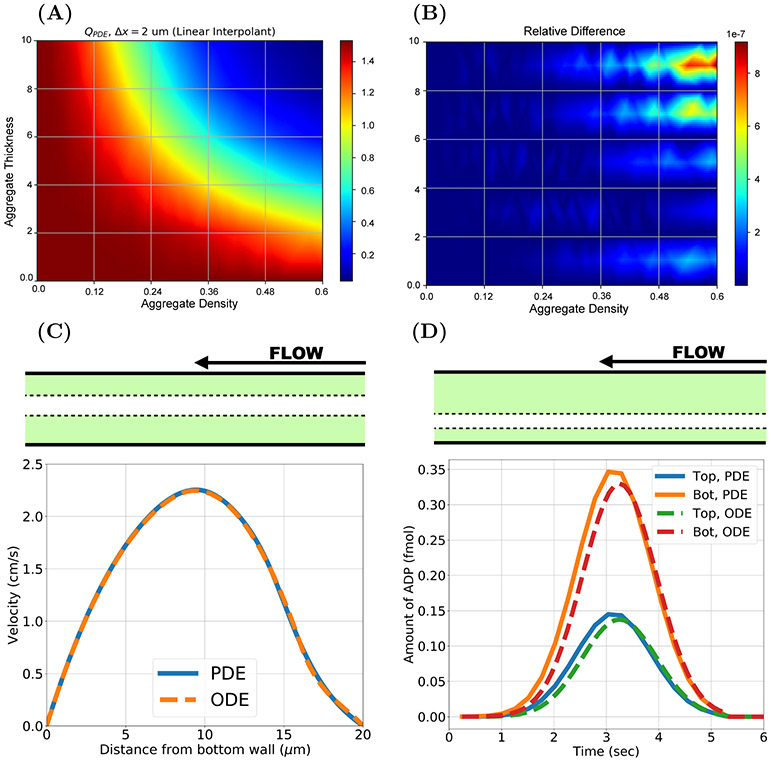

FIG. 7.

Flow inputs, profile comparison, and ADP transport model calibration. (A) 3 dimensional flow rates QPDE in prebound platelet simulations with the PDE model using spatial discretization Δx = 2 μm and (B) the relative difference between the flow rates generated with (Δx = 2 μm) and (Δx = 1 μm). (C) Velocity profiles from ODE and PDE models for an asymmetric prebound platelet configuration (dt = 6 μm, , db = 8 μm, ). (D) A similar prebound platelet configuration (dt = 12 μm, , db = 4 μm, ) experiment tracks the amount of ADP in the aggregate for the PDE and ODE models. Note θmax = 0.6.

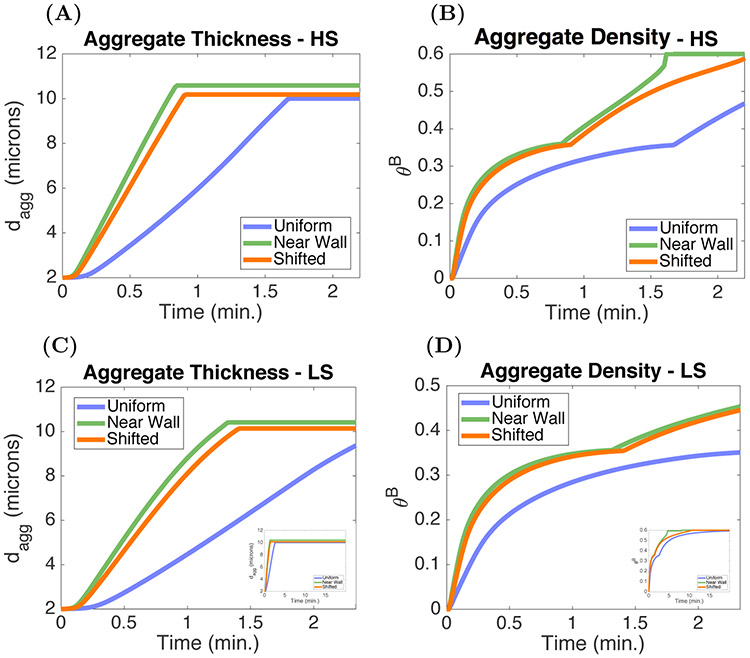

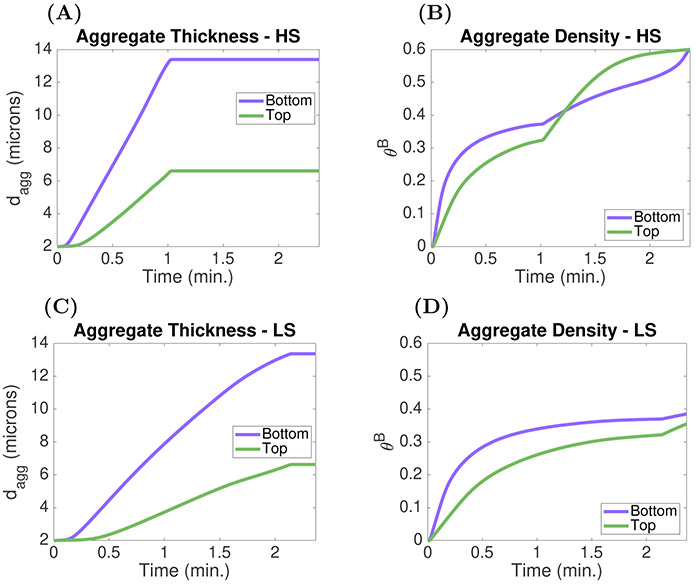

Using this new calculation for the pressure gradient, we validated the Brinkman–Stokes calculation describing the fluid through the injury with PDE velocity profile comparisons shown in Figure 7(C). Figure 7(D) highlights the calibration of the ODE model description of the diffusive transport of ADP. Assuming soluble agonist ADP-independent platelet activation, A([ADP]agg, [ADP]BL) = 1, we used MFA occlusion times to determine physiologically relevant values for the kinetic rate constant (Figures 8(A)-(B)). Fixing a value for , we compared occlusion metrics (Figures 8(C)-(D)) from the ODE and PDE models. Next, we assessed and characterized occlusion of the injury channel as a function of the flow shear rate and in Figures 9(A)-(B) and then conducted similar experiments to test the sensitivity of model output to ADP-dependent platelet activation as shown in Figures 10(A)-(D). Evidence of the effects of dilution of ADP due to advective and diffusive transport on aggregate formation is found in Figures 11(A)-(H).

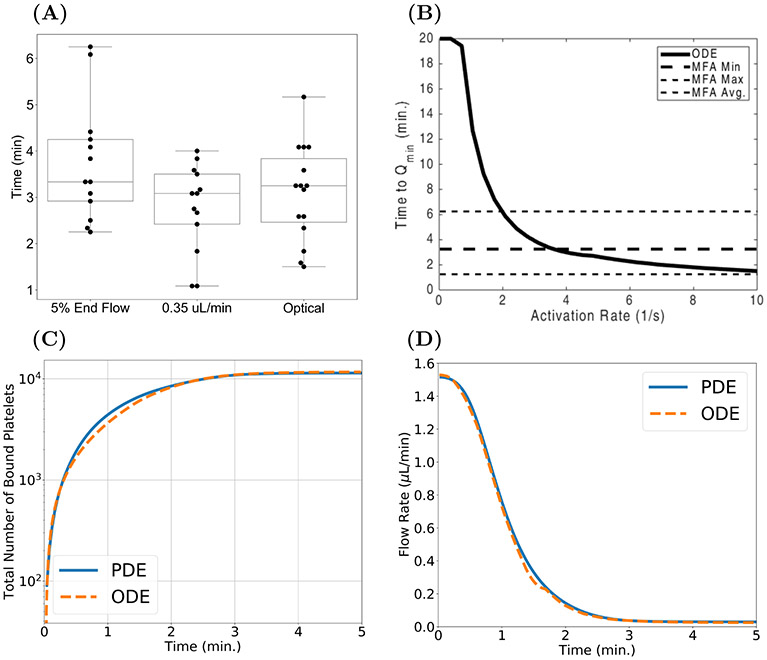

FIG. 8.

Aggregation model calibration. (A) Occlusion times generated by the MFA and (B) ODE model times to Qmin = 0.35 μL/min as a function of the ADP-independent platelet activation rate . Comparison of ODE (orange) and PDE (blue) model outputs with a fixed shear rate (≈ 2400 s−1) and ADP-independent platelet activation rate (). (C) Total number of bound platelets in the aggregate and (D) rate of blood flow through the injury channel.

FIG. 9.

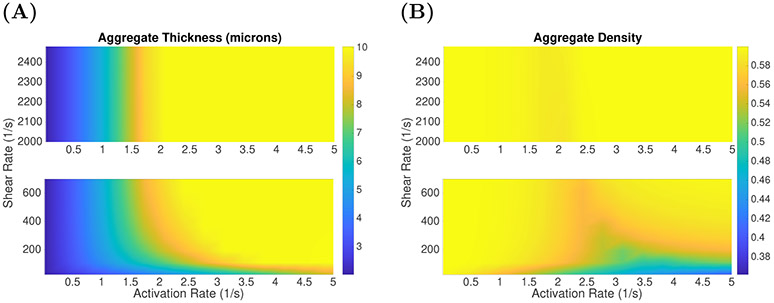

Occlusion in the injury channel with ADP-independent activation. ODE model aggregate (A) thicknesses (μm) and (B) densities due to variations in ADP-independent platelet activation rates and shear rate γ, after 10 minutes of simulation time.

FIG. 10.

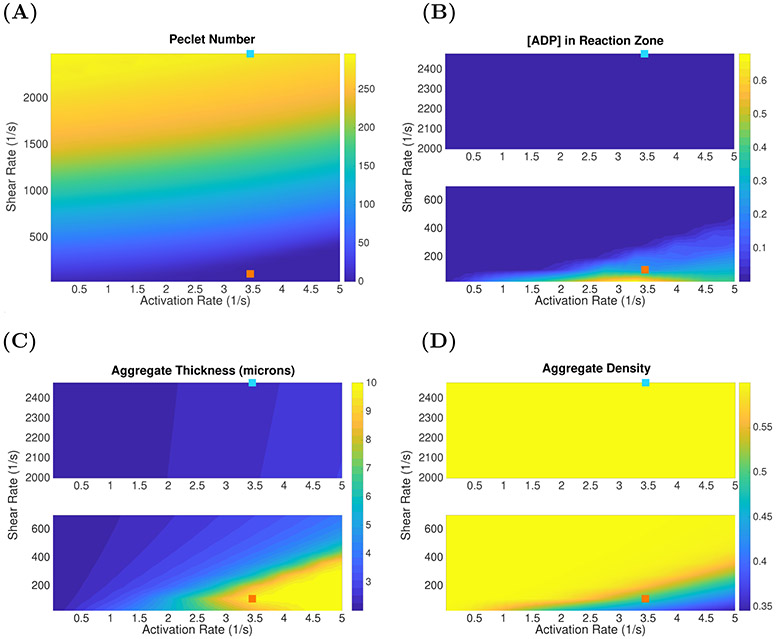

Aggregate heterogeneity under variations in flow conditions and ADP-dependent platelet activation. (A) Peclet number describing the advective versus diffusive transport of soluble agonist ADP. (B) Concentration of ADP in the aggregate and associated boundary layer. (C) Aggregate thickness and (D) aggregate density as functions of shear rate and platelet activation rate constant. These results identified two flow regimes for a fixed platelet activation rate constant ; high shear (cyan square) and low shear (orange square). The metrics are taken after 10 minutes of simulation time.

FIG. 11.

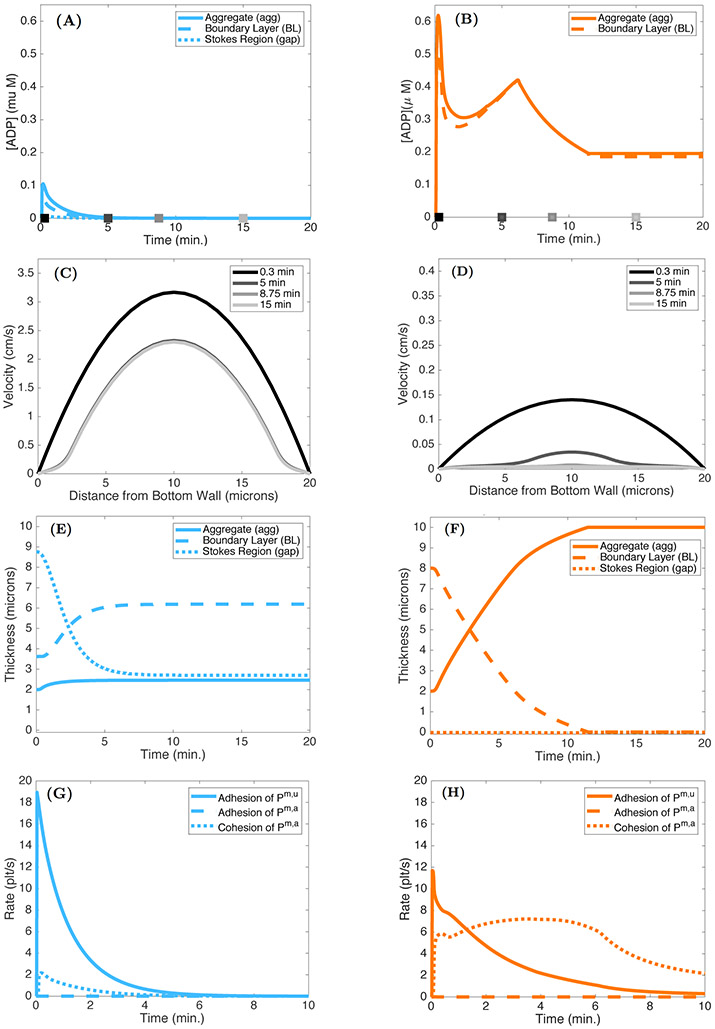

Effect of ADP dilution on aggregate formation. ADP concentrations in the aggregate, boundary layer, and gap under (A) high and (B) low shear conditions. Note there is no gap in the low shear conditions due to the thicknesses of the aggregate and boundary layer. The gray-scale squares denote the times at which the velocity profiles were determined. Velocity profiles at 0.3, 5, 8.75, and 15 minutes under (C) high and (D) low shear conditions. Thicknesses of the aggregate, boundary layer, and gap under (E) high and (F) low shear conditions. The rates of adhesion and cohesion under high (G) and low (H) shear conditions.

3.1. Model validation and calibration.

For this study, we simulated two dimensional (2D) flow through the injury channel with fixed preformed platelet aggregates. For each simulation, a different symmetric configuration of preformed aggregates was specified by choosing the thicknesses db = dt ∈ {2, 4, 6, 8, 10 μm} and bound platelet densities . The PDE model was used to calculate the steady-state velocity field and 2D volumetric flow rate QPDE for each configuration as detailed in Appendix A.3. The “flow map” QPDE(db, , dt, ) obtained when the PDE calculation used a spatial discretization with step size Δx = 2 μm is shown in Figure 7(A), and Figure 7(B) presents evidence that the flow rate calculation is insensitive to further refinement in Δx. The maximum relative difference in flow rates for the two step sizes, which occured for an aggregate density of ≈ 0.5 and with almost-occlusive thicknesses of ≈ 9.5 μm, was approximately 8(10)−7.

Figure 7(C) shows velocity profiles from the ODE and PDE models for asymmetric aggregates. The ODE profile shows excellent agreement in both Brinkman layers and the Stokes region with the PDE profile obtained halfway through the injury channel. The flow through the top aggregate, which is thin (dt = 4 μm) but dense () is slower than that in the thick (db = 8 μm) yet loose () bottom aggregate, because resistance to flow increases as aggregate density increases.

In Figure 7(D), we show results from another asymmetric preformed aggregate configuration, assuming that all of the platelets in the aggregates became activated at time t = 0. Shown are the amounts of ADP in each of the aggregates due to release of ADP by these platelets in both the ODE and PDE models. Less ADP is washed downstream from the thin and dense bottom aggregate because the flow in it is slower. Consequently, the maximum concentration of ADP in the bottom aggregate is higher than that in the thick and loose top aggregate (not shown). It is important to note that the concentration of ADP in each aggregate is subject to diffusive transport. The ODE model accounts for lateral diffusion (perpendicular to the channel walls) but not longitudinal diffusion. The differences in the models’ outputs are largely due to longitudinal diffusion of ADP out of the injury channel in the PDE model (results not shown).

One of our main objectives in this work was to develop a mathematical model that can generate aggregates that grow to fill the injury channel. This objective was motivated by experiments conducted in the MFA model. Figure 8(A) shows three metrics of occlusion times from experiments using the MFA. The median times for all three metrics of occlusion are approximately 3.25 minutes with a minimum occlusion time of 1.15 minutes and a maximum time of 6.25 minutes. The metric of occlusion best suited for comparison with the ODE model output is the “time to Qmin = 0.35 μL/min measurement.” Using an ADP-independent platelet activation regime (A([ADP]agg, [ADP]BL) ≡ 1) in the ODE model simulations yields the “time to Qmin” results obtained for a range of platelet activation rates as shown in Figure 8(B). For , the time to Qmin is within the bounds defined by the MFA results. In Figures 8(C)-(D), we compare the growth of aggregates using the ODE model (orange) with output from the PDE model (blue). Metrics are the time course of the total number of bound platelets and of the flow rate through the injury channel. For a fixed shear rate ≈ 2400 s−1 and a fixed platelet activation rate of 3.4 s−1, model results fall within the range of the experimental values. Note that in Figure 8(B), the time to Qmin with the chosen activation rate is within the range (black, dashed lines) seen with the MFA. Additionally, both computational models yielded aggregates that reduced the flow rate of the injury channel in an amount of time similar to that seen in the MFA results.

3.2. Occlusion of injury channel and flow rate reduction.

To better understand how shear rate and ADP-independent platelet activation affect aggregate formation, we performed simulations in which we varied both the shear rate and activation rate constant . Aggregate thickness dagg and aggregate density θB after 10 minutes of simulation time are shown in Figures 9(A)-(B). For shear rates 200 s−1 < γ < 2400 s−1, occlusive aggregates formed if while significantly thinner but high density aggregates form for below approximately 1.5 s−1. For shear rates less than 100 s−1, aggregate thickness increases as is increased, but in contrast to what is seen for high shear rates, the aggregate density decreased as the activation rate constant was increased from 1.0 to 5.0 s−1. Hence the model predicts that occlusive aggregates form under a wide range of shear rates provided the platelet activation rate is large enough, but the nature of the aggregates is sensitive to activation rate especially at low shear rates.

3.3. Dilution of chemical agonists.

In this section we turn to the model’s behavior when the platelet activation rate is dependent on the ADP concentration A([ADP]agg, [ADP]BL). If the ADP concentration is substantially below the transition concentration [ADP]* = 1 μM in this function, results might be very different from those just reported with a constant rate of platelet activation.

We explored how different forms of transport within the aggregates affects their growth by calculating the ADP-related Peclet number after 10 minutes of simulation time. This nondimensional number is defined as the ratio of the rate of advection by flow and the rate of diffusion of ADP. For our purposes

where u(dapz) is the velocity at the edge of the ABL in the Stokes region (dapz = dagg + dabl). Figure 10(A) shows that advective transport dominates for shear rates greater than 500 s−1 for activation rate constants ranging from 0.02 – 5.0 s−1, but that, while still large, it is much lower for shear rates less than 200 s−1. We can see that for most of the shear rate range, the concentration of ADP in the PRZ after 10 minutes is much less that the activation transition concentration [ADP]* = 1 μM and that the shear rate must be reduced to below ≈ 100 s−1 for the ADP concentration to reach 0.4 μM. As shown in Figure 10(B), increasing the value of results in higher ADP concentrations. Plots of aggregate thicknesses and densities in Figures 10(C)-(D) identify two flow regimes that for a fixed activation rate constant yield occlusive aggregates under low shear conditions and thin nonocclusive, but dense, aggregates under high shear conditions.

To better understand the differences in aggregates that form under high shear (cyan squares in Figure 10) and low shear (orange squares in Figure 10) conditions, we consider the model output in Figures 11(A)-(H). The initial rate of adhesion is greater in the high shear case (Figures 11(G)-(H)) because of the faster replenishment of platelets by the faster flow. Hence, the initial rate of ADP release is also greater in this case. Despite this, the ADP concentrations are more than 6-fold lower (Figures 11(A)-(B)) because the faster flow carries ADP away more rapidly. In the low shear case, the two ABLs are so thick (Figures 11(E)-(F)) that there is no gap region in that case. For both shear conditions, the velocity through the injury channel decreases as the aggregates form. The reduction in peak velocity is approximately 30% after 15 minutes in the high shear case (Figure 11(C)), while the relative reduction is much greater, at approximately 80%, under low shear (Figure 11(D)). This larger reduction in velocity results in a lower rate of advective transport and consequentially increases the boundary layer thickness (orange, dashed) for ADP (Figure 11(F)). As the aggregate grows, this layer becomes smaller until the injury channel occludes. Because platelet activation by ADP continues in the low shear case, ADP continues to be released and its concentration remains significant for the entire period leading up to occlusion.

4. Discussion.

We developed a novel mathematical model of flow-mediated primary hemostasis in an extravascular injury which is able to track the process from initial platelet deposition to occlusion. Model validation and calibration with PDE and MFA models yielded excellent agreement in model metrics. ODE model comparisons with the PDE model velocity profiles validate the ODE model component describing the fluid dynamics. MFA occlusion times and PDE model outputs such as amounts of (ADP), total number of bound platelets, and flow rates through the injury channel were used to calibrate ODE model components describing ADP diffusive transport, platelet activation, and aggregate formation dynamics. The model met the difficult and nuanced challenge of capturing injury occlusion in a nonspatial description. We compared MFA occlusion times to ODE model output as a function of ADP-independent platelet activation rate (A([ADP]agg, [ADP]BL) = 1). Next, we studied both ADP-independent and ADP-dependent platelet activation and how both activation and flow affect aggregate structure. Metrics of transport, ADP concentration, and aggregate height and density confirmed that ADP dilution significantly limited aggregate formation. However, we have shown experimentally that platelet aggregates can fully occlude the injury channel in our bleeding chip (data not shown) in the absence of coagulation, and thus there is a need to extend and further refine our platelet model. In particular, force-dependent bond formation and breaking in the rates of platelet adhesion and cohesion will likely be necessary to include. This will require the modeling of more mechanisms of platelet activation but it will also allow for platelet detachment from a growing aggregate.

4.1. Limitations and extensions.

Most of the model parameters have been either previously estimated from the literature or fit to the model output generated by the PDE and MFA models. The previously estimated parameters are found in Appendix C (Tables 5 and 6). The parameter values we are less certain of are numbers corresponding to the functions describing adhesion and cohesion (dse, kb, and sb) and the permeability constant CK, which prescribes the gr owing resistance to flow within the aggregate. In reference to dse, kb, and sb, the values were determined through tuning ODE model output with flow rates and the nu mber of bound platelets in the aggregate associated with the PDE model. Details are found in Appendix C.1 (Table 8). We determine a value for CK using the protocol described in Appendix C.1.1. In addition to these constant parameters, the number density of mobile unactivated platelets at the inlet to the injury channel, Pup(y), is prescribed. We assume that the shape of the distribution does not evolve as the top and bottom aggregates grow. However, the model framework allows for the change in flow to affect the evolution of Pup(y), the upstream platelet distribution.

Table 5.

Diffusion coefficients, ADP granule release, and upstream platelet number density.

Table 6.

Platelet transitions.

In this paper, we consider only one pathway of platelet activation and do not consider coagulation. In reality, ADP, thrombin (resulting from coagulation), and subendothelial collagen elicit different types of platelet activation responses. For example, thrombin cleaves protease-activated receptors on the platelet surface, PAR-1 and PAR-4, and is a stronger activator of platelets than ADP [1, 26]. There is increasing indication that partially activated and even unactivated platelets may be able to bind, if only transiently, to a growing aggregate. Such binding would increase a platelet’s time of exposure to other chemical agonists and possibly lead to more activation and faster aggregate growth. This motivates the extension of the model to include alternative mechanisms of platelet activation and binding/unbinding.

The processes of platelet binding and unbinding are dictated by the types of bonds that form between platelets and the vessel wall as well as amongst platelets. Along with the transport of platelets to the site of injury, the flow conditions in the local environment determine the likelihood that bonds form and break. At low shear rates (< 200 (1/s)), unactivated platelets near the wall adhere to the collagen embedded in the subendothelial matrix [20, 38]. Specifically, bonds between GPVI receptors and collagen form and trigger activation of integrin receptors (α2β1 and αIIbγ3). The platelet-collagen bonds bring the platelet to rest and allow for firm adhesion to the subendothelial surface. Adhesion of platelets is a multistep process at high shear rates (> 500 (1/s)). More specifically, unactivated and mobile platelets transiently bind to immobilized vWF molecules associated with a thrombus via their GPIb receptors [19, 34]. This process slows the platelets and allows time for activation of integrins that mediate the formation of strong, long-lived αIIbβ3-fibrinogen bonds [19, 35, 37]. Future work will include model extensions of this framework that differentiate platelets by the types of bonds that form on their surfaces and by drag on the aggregate that effects individual bonds amongst the aggregated platelets.

In addition to extending our occlusive model of platelet aggregation to include more mechanisms of activation and bond formation and breaking, we can include the biochemical reactions of coagulation, maximizing the versatility and reduced computational cost of the model. The coagulation cascade occurs on the surfaces of platelets producing a key end product thrombin. Thrombin converts fibrinogen to fibrin, which polymerizes forming a stabilizing mesh that supports the platelet aggregate. Our previous mathematical model of thrombosis [21, 27, 28] can be linked to the above model, contributing minimal additional computational cost. Both model extensions will utilize the above framework to develop the first flow-mediated mathematical model of hemostasis in an extravascular injury that incorporates both platelet function and coagulation, resulting in a high throughput screening tool that can identify modifiers of occlusion and embolization.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The work of the authors was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01HL120728, R61HL141794 and the National Science Foundation grant CBET-1351672.

Appendix

Appendix A. Flow through bleeding chip.

A.1. Circuit analog system.

We use hydrodynamic analogs of Kirchoff’s and Ohm’s laws to formulate a linear system of equations that describes the flow through the HC shown in Figure 3(A):

| (A.1) |

| (A.2) |

| (A.3) |

| (A.4) |

| (A.5) |

| (A.6) |

| (A.7) |

The inlet and outlet pressures PB, PW, PCB, and PCW are known and we assume the resistance through the injury channel RM is an input parameter determined by the Brinkman–Stokes calculation. Additional input parameters include R1, R2, R3, and R4, which correspond to the resistances associated with the blood and wash channels. Equations (A.1)-(A.7) yields a system of seven equations with seven unknowns. We can write them as the following matrix system:

| (A.8) |

Values of pressures and resistances used in the HC system are summarized in Tables 1 to 3. There are variable viscosities corresponding to the blood, wash and injury channels. Furthermore, the downstream end of the wash channel will be a mix of the blood and the wash when blood can flow freely from the blood channel through the injury channel. We account for these viscosities through the resistance terms found in Table 2. Assume that the viscosity of the downstream end of the wash channel is an average of the blood and wash viscosities. In the fluid simulations, we use a volume-averaged viscosity through the entire domain μ = 0.0267 dynes·s/cm2. We also assume there is an effective length of the injury channel that spans outside its 150 μm length, corresponding to the laminar flow that enters and exits the injury channel. The effective length of the channel, , is used in the calculation of the pressure gradient through the injury channel when using the PDE flow map output.

Table 3.

Pressures used in the HC. See Figure 3(A) for reference.

| Pressure inlet (Blood, PB) | 6.24364 × 102 Pa |

| Pressure inlet (Wash, PW) | 1.7418 × 102 Pa |

| Pressure outlet (Blood, PCB) | 2.8422 × 102 Pa |

| Pressure outlet (Wash, PCW) | 0 Pa |

| Pressure drop across injury P1 — P2 (no aggregate) | 2.80851 × 102 Pa |

Table 2.

HC viscosities and computed resistances. See Figure 3(A) for reference.

| Blood channel viscosity | 3.6 × 10 −2 Poise |

| Upstream wash channel viscosity | 1 × 10−2 Poise |

| Injury channel viscosity | 2.67 × 10−2 Poise |

| Downstream wash channel viscosity | 2.3 × 10−2 Poise |

| R1, R2 | 5.3672 × 106 Pa s/m2 |

| RM (no aggregate) | 6.60825 × 108 Pa s/m2 |

| R3 | 1.02 × 106 Pa s/m2 |

| R4 | 2.346 – 106 Pa s/m2 |

A.2. Experimental methods and materials.

A.2.1. Materials.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) (A9418), 3,3’-dihexylox acarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) (D273) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). 3.2% sodium citrate vacutainers (369714) and 21-gauge Vacutainer® 21 Safety-Lok blood collection sets (367281) were from Becton Dickson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyltrichlorosilane (FOTS) (SIT8174.0) was from Gelest (Morrisville, PA). Polydimethylsiloxane and crosslinker were obtained from Krayden (Denver, CO). Collagen related peptides (CRP-XL) [GCO (GPO)10GCOGamide], 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein, and VWF-III [GPCGPP)5GPRGQ OGVMGFO (GPP)5GPC-amide] were obtained from Cambcol Laboratories (Cambridgeshire, UK). Glass slides (1” × 3”) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Lenexa, KS). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was prepared to 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, and pH 7.4. Phe-Pro-Arg-chloromethylke tone (PPACK) vacutainers were obtained from Haematologic Technologies, Inc (Essex, VT).

A.2.2. Blood collection and preparation.

Blood was collected from healthy donors by venipuncture into 4.5 mL PPACK vacutainers (final concentration of 75 μM) using a 21 gauge needle. Prior to collecting blood into the PPACK vacutainers, one vacutainer of blood was collected into a 3.2% sodium citrate vacutainer and discarded. DiOC6 was added to blood to a concentration of 1 μM and was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min prior to the microfluidic device assay. The study and consent process was approved from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A.2.3. Device fabrication, preparation, and operation.

A polydimethylsiloxane microfluidic device was created using stand photolithography and soft lithography techniques. The device was made with an “H-shaped” geometry, with a “blood” channel (w = 110 μm, h = 50 μm) on the right, a “wash” channel on the left (w = 110 μm, h = 50 μm), and an “injury” channel (l = 150 μm, w = 20 μm, h = 50 μm) connecting the two vertical channels (Figure 1(A)). The device was plasma bonded to a polydimethylsiloxane coated glass slide, and a solution of the collagen related peptides CRP, GFOGER, and VWF-BP were patterned in the injury channel and wash channel at a concentration of 250 μg/mL for each peptide for 4 hours. Following patterning, the entire device was rinsed and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 45 min.

A.2.4. Whole blood MFAs.

Pressure controllers (Fluigent MFCS-EZ) coupled to flow meters (Fluigent FRP) were used to perfuse blood and wash buffer at a flowrate of 5.5 μL/min and 10 μL/min, respectively, through the device. Images of thrombus in the injury channel were obtained using brightfield and epifluorescent microscopy on an inverted microscope (Olympus IX81, 20X Objective, NA 0.4, Hammamatsu Orca R2 Camera). Assays were run until the injury channel was fully occluded. The time to occlusion in the device was determined through a variety of ways. Optically, we defined the time to occlusion as the time point in which no red cells could be seen passing through the injury channel. Additionally, we used the flow meter measurements on the inlet and outlet of the device to compute the flow rate through the injury channel. This flow measurement was used to calculate two other occlusion metrics: the time to reach 10% of the endpoint flow rate and the time needed to reach 0.35 μL/min flow.

A.3. Creation of flow map.

For calibration with the PDE model, the ODE model utilizes a flow rate through the injury channel to prescribe the appropriate corresponding pressure drop and this is needed for all possible combinations of aggregate heights and densities. To acquire these approximations, we used a 2D PDE model of flow through an extravascular injury channel that was initialized to be filled with various heights and densities of porous material to represent possible aggregate formations. For each of the various aggregates, the model was simulated until the flow came to an equilibrium state and resulting flow rates were recorded; the results were assimilated into what we call the flow map. Details of these calculations are as follows.

The geometric configuration for the 2D model is the H domain as depicted in Figure 1(A) and as described in detail in our previous work [8]. Briefly, there are two vertical channels through which blood and wash (buffer) flow. These channels are bifurcated by a horizontal injury channel and, with specified flow rates through the vertical channels, blood flows through the injury channel and out into the wash channel. Within the injury channel, porous aggregates can be placed and fixed to study pressure drops and flows, or the aggregates can grow dynamically according to platelet and ADP equations. Fluid at the fixed flow rate enters the domain at the top of the vertical channels and conditions on pressure at the bottom of the vertical channels are prescribed. For studies with fixed, initial distributions of porous aggregate, the aggregate is considered only on the interior of the horizontal injury channel and is placed in such a way that the nonzero porosity is centered along a length Lh – 2Δx, where Δx is the size of one computational grid cell. For these simulations, Δx ≈ 2μm.

Fluid throughout the computational domain is modeled with the Navier–Stokes–Brinkman equations to account for unimpeded flow in the vertical channels and impeded flow through the porous aggregate within the injury channel. The equations take the form

| (A.9) |

| (A.10) |

where and p represent fluid velocity and pressure, respectively, μ is the dynamic viscosity, and ρ is the fluid density. The term represents a frictional resistance to the fluid motion due to the presence of the platelet aggregate with volume fraction of bound platelets, θB. Equations (A.9)-(A.10) are solved numerically using the rotational projection method, as described previously [8, 44]. We assume a functional form of the friction term, α(θB), that follows the Carman–Kozeny relation and the particular value of CK is specified in Appendix C.1.1.

Flow rates that correspond to experimental setups at the top of the blood channel Qb and wash channel Qw are used to set the velocity boundary conditions at their respective inlets by using a parabolic velocity profile of the form

where uy is the y-component (parallel to the vertical channels) of the velocity field , W is the width of the blood channel, wi the center point of the inlet channel corresponding to index i, and Qi is the given flow rate corresponding to index i with i = b, w. Outlet pressure conditions are set using an open boundary condition of the form

where un and ut are the normal and tangential components of the fluid velocity, respectively, μ is the fluid viscosity, p is the fluid pressure, and s is the prescribed (constant) pressure given from the circuit calculation, as described above.

To construct the flow map in terms of height and density of the initial aggregate distribution, the flow simulations above were carried out for db, dt ∈ {2, 4, 6, 8, 10 μm}, where db, dt are the height of the bottom and top aggregate, respectively, and for , , where , are the density of the bottom and top aggregate, respectively. The resulting flow map acts as a “look-up” table; given ODE model values of db, dt, , we do quadrilinear interpolation from table values to determine QPDE(db, dt, , ).

A.4. PDE model of platelet aggregation.

In this section, we detail all the components of the PDE model of platelet aggregation developed in tandem with the ODE model described in this paper. The evolution equations for the three species of platelets are given by

| (A.11) |

| (A.12) |

| (A.13) |

where , and Dp, kadh(x), kcoh, and W(θT) are the platelet diffusion coefficient, spatially dependent adhesion rate, cohesion rate coefficient, and hindered platelet flux coefficient, all used as previously described [8, 23]. The parameter η(x) is a local approximation to the bound platelet fraction that indicates both the location and density of bound platelets to mobile platelets as part of the cohesion rate; the cohesion rate is enhanced where th e local bound platelet fraction is increased. We approximate this parameter on a triangular but structured mesh, taking advantage of the interpolated values of θB, which we will denote as , defined using the finite element method. Since θB is defined on the finite element mesh with piecewise linear interpolants, we can approximate θΒ anywhere in the domain by simply evaluating these interpolants. We allow η(x) at nodes to depend on values of θB that are up to hp = 2 μm away. Given a nodal point (xj, yi) on the triangular mesh, we use a weighted average that depends most strongly on θB (xj, yi):

Tracking ADP concentration and its effects on platelet activation in the PDE model is similar to that in the ODE model. Activation occurs through

| (A.14) |

where is the activation rate and [ADP]* is the critical concentration of ADP for which there is significant activation of platelets by ADP. ADP molecules are released by bound, activated platelets and are transported in the fluid by advection and diffusion. Hence, we track the ADP concentration with an advection-diffusion-reaction equation

| (A.15) |

where Da is the diffusion coefficient for ADP, and σrelease is the release rate, and they are defined exactly the same way as is done in the ODE model, described above. The coupled flow equations are the Navier–Stokes–Brinkman equations described above with the volume fraction due to bound platelets defined as .

Appendix B. Stokes–Brinkman velocity system.

To determine the velocity profile through the injury channel described in subsection 2.1.2, we solve a linear system of six equations and six unknowns. Let yt = dh – dt.

| (B.1) |

| (B.2) |

| (B.3) |

| (B.4) |

| (B.5) |

| (B.6) |

The pressure gradient Gh, and αb, αt, μ, db, dt, and the width of the injury channel, dh, are prescribed. The unknowns are A, B, Ab, Bb, At, Bt. This system (B.1)-(B.6) can be written in the following form:

| (55) |

where the matrix is defined as

Note that the right-hand side of the system is linearly dependent on the pressure gradient Gh. Therefore, we assume Gh = 1 and solve the linear system of six equations for the six constants that prescribe the flow velocity profile. The velocity profile is used to calculate the resistance RM through the injury channel as described below:

The effects of the growing aggregate on the flow velocity through the injury channel are captured in the quantity RM, which is an input parameter in the HC system describing the flow of blood through the bleeding chip. The true Gh is determined by solving the HC system and is used to scale the velocity profile that was obtained with Gh = 1.

Appendix C. Model parameters.

C.1. Calibrated parameters.

The permeability constant CK used to define the Korzeny–Carman relation [29] was both calibrated through PDE model comparisons and previously validated through PDE and MFA model comparisons [39, 48]. Constants c1 and c2 used in the definitions of the diffusive fluxes of ADP described in subsection 2.3.3 were determined through calibration with the PDE model. Assigning values for parameters , kb, sb, and dse was an iterative process, involving both the MFA and PDE models. Values for platelet activation rate constant were calibrated using the MFA data shown in subsection 3.1, assuming fixed kb, sb, and dse values. Additionally, we fixed a value and tuned aggregate formation partition functions detailed in subsection 2.4 with the PDE model. This process was repeated to yield excellent agreement with the MFA and PDE results as shown in Figure 8. All calibrated parameter values are summarized in Table 8.

C.1.1. Aggregate permeability.

When considering aggregate permeability, the significant differences between “white” and “red” clots must be considered. A white clot is usually formed under high shear and is predominantly made up of platelets whereas a fibrin-rich red clot forms under low shear or static conditions. Table 7 lists the computed permeability comparison results from the literature. It is shown that white clots are significantly more permeable than red clots. In addition to the type of clot, the flow conditions and experimental setup generate significant variability. For example results in [48] were generated by measuring the permeability of platelet-rich aggregates at various volume fractions. Permeability values of 1.5 × 10−5 ± 3.3 × 10−6 – 6.1 × 10−3 ± 1.1 × 10−3 μm2 were calculated from platelet-rich clots with platelet volume fractions of 0.31–0.61. In conclusion, both flow conditions and experimental setup yield a wide range of permeabilities. We tuned the constant CK using input from both PDE and MFA models. More specifically, we assume a functional form of the Brinkman coefficient that follows the Carman–Kozeny relation [29]

Table 7.

Permeability comparison.

| Clot type | Permeability [μm2] | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Red | 5.45 × 10−6 | Colace, Muthard and Diamond (2012) [6] |

| Red | 1.5 × 10−5 | Wufsus, Macera, and Neeves (2013) Platelet 61% [48] |

| Red | 6.1 × 10−3 | Wufsus, Macera, and Neeves (2013) Platelet 31% [48] |

| White | 0.2 | Kobayashi and Ku (2016) [36] |

| White | 2.8571 | calibrated with PDE/MFA models |

This particular value of CK was determined by performing flow simulations with the PDE model in which the injury channel was completely filled with aggregate at a minimum porosity until it matched the experimentally observed flow rate of 0.12 μL/min.

C.1.2. ADP diffuse flux parameters.

As mentioned in subsection 2.3.3, diffusive fluxes of ADP are modeled using Fick’s law and require the calibration of constants c1, c2 with the PDE model. Comparison of results of prebound platelet experiments and the transport of ADP determined values for c1 = 1/2, c2 = 1/4 used in full ODE model simulations (see Figure 7(D)).

C.1.3. Platelet activation rate constant.

Values for the rate of platelet activation were determined by comparing ODE model output with MFA occlusion times described in subsection 3.1. Specifically, upper and lower bounds for the parameter were estimated as well as a mean rate of platelet activation (see Figures 8(A)-(B)). In the context of the ODE model output, the average occlusion time of 3.2 minutes coincides with a platelet activation rate .

C.1.4. Aggregation partition functions.

The partition functions β, γ are assumed to have the forms