Abstract

Sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score is used as a predictor of outcome of sepsis in the pediatric intensive care unit. The aim of the study is to determine the application of SOFA scores as a predictor of outcome in children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit with a diagnosis of sepsis. The design involved is prospective observational study. The study took place at the multidisciplinary pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), tertiary care hospital, South India. The patients included are children, aged 1 month to 18 years admitted with a diagnosis of sepsis (suspected/proven) to a single center PICU in India from November 2017 to November 2019. Data collected included the demographic, clinical, laboratory, and outcome-related variables. Severity of illness scores was calculated to include SOFA score day 1 (SF1) and day 3 (SF3) using a pediatric version (pediatric SOFA score or pSOFA) with age-adjusted cutoff variables for organ dysfunction, pediatric risk of mortality III (PRISM III; within 24 hours of admission), and pediatric logistic organ dysfunction-2 or PELOD-2 (days 1, 3, and 5). A total of 240 patients were admitted to the PICU with septic shock during the study period. The overall mortality rate was 42 of 240 patients (17.5%). The majority (59%) required mechanical ventilation, while only 19% required renal replacement therapy. The PRISM III, PELOD-2, and pSOFA scores correlated well with mortality. All three severity of illness scores were higher among nonsurvivors as compared with survivors ( p < 0.001). pSOFA scores on both day 1 (area under the curve or AUC 0.84) and day 3 (AUC 0.87) demonstrated significantly higher discriminative power for in-hospital mortality as compared with PRISM III (AUC, 0.7), and PELOD-2 (day 1, [AUC, 0.73]), and PELOD-2 (day 3, [AUC, 0.81]). Utilizing a cutoff SOFA score of >8, the relative risk of prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation, requirement for vasoactive infusions (vasoactive infusion score), and PICU length of stay were all significantly increased ( p < 0.05), on both days 1 and 3. On multiple logistic regression, adjusted odds ratio of mortality was elevated at 8.65 (95% CI: 3.48–21.52) on day 1 and 16.77 (95% confidence interval or CI: 4.7–59.89) on day 3 ( p < 0.001) utilizing the same SOFA score cutoff of 8. A positive association was found between the delta SOFA ([Δ] SOFA) from day 1 to day 3 (SF1–SF3) and in-hospital mortality (chi-square for linear trend, p < 0.001). Subjects with a ΔSOFA of ≥2 points had an exponential mortality rate to 50%. Similar association was—observed between ΔSOFA of ≥2 and—longer duration of inotropic support ( p = 0.0006) with correlation co-efficient 0.2 (95% CI: 0.15–0.35; p = 0.01). Among children admitted to the PICU with septic shock, SOFA scores on both days 1 and 3, have a greater discriminative power for predicting in-hospital mortality than either PRISM III score (within 24 hours of admission) or PELOD-2 score (days 1 and 3). An increase in ΔSOFA of >2 adds additional prognostic accuracy in determining not only mortality risk but also duration of inotropic support as well.

Keywords: SOFA score, PELOD-2, PRISM III, outcome prediction, septic shock

Introduction

Although sepsis is a complex, heterogeneous syndrome with high mortality, the early recognition of sepsis and septic shock is a key initial element that ultimately drives the clinical decision-making process. 1 2 3 Septic shock, the most severe form of sepsis, is associated with an increased risk of mortality, requiring specific therapeutic strategies to alter outcomes. The outcomes of septic shock are greatly influenced by the site of infection, causative organisms, acute organ dysfunctions, and preadmission co-morbidities. The mortality rate of sepsis in children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of developing countries is observed to be greater than 50%. 4

There are several outcome prediction models currently available, that are used in clinical practice. These include severity of illness prediction scores-pediatric risk of mortality III (PRISM III), the pediatric index of mortality-2, and pediatric logistic organ dysfunction-2 (PELOD-2) scores each of which have been validated and are being used in predicting prognosis of patients admitted to the PICU. 5

The PRISM III score is the most commonly used scoring system to discriminate the prediction and outcome of patients admitted to the PICU. However, it is a one-time scoring system calculated at admission of which some authors have provided evidence indicating that the PRISM III score overestimates mortality. 6 7 8 9 Outcome of children with sepsis admitted to PICU, depends not only on the initial presence of, but subsequent development of sequential organ dysfunction. Since evolving organ dysfunction, in sepsis, can change the outcome, a scoring system that can be sequentially measured could enable outcome prediction in pediatric sepsis. The PELOD-2 score is one such tool that is utilized to determine the severity of organ dysfunction and subsequent severity of illness in the critically ill child. 6 Unfortunately, calculation of the PELOD-2 score is cumbersome.

The sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score has been developed to prioritize patient admission, direct appropriate management, and improve outcome in critically ill adults. 7 The score increases concurrently with severity of organ system failure. This scoring system has been extensively used in the adult population owing to its simplicity. The measured variables are readily available and are routinely measured in intensive care units (ICUs). Trends in SOFA score obtained over the first 48 hours have been found to be a sensitive indicator of ICU outcome, with decreasing scores associated with a reduction in mortality from 50 to 27%. 8 This simple, objective, organ-focused morbidity assessment score has also been studied in varied subsets of PICU patients to predict outcome. 9 10 However, a knowledge gap exists in that a prospective study to provide clinical data evaluating the utility of SOFA score in children with septic shock is currently unavailable. Hence the present study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of SOFA to discriminate clinically important outcomes in children with sepsis. We also aimed to study the efficacy of delta SOFA (∆SOFA) defined as the change in SOFA score over a predefined time (over 72 hours), to predict mortality in septic children admitted to the PICU.

Methodology

This prospective observational study was conducted in a 12 bed PICU of a tertiary care hospital in South India over a 2-year period. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics and Research Board Committees. An informed written consent was obtained from the parent (s)/guardian(s) of each patient prior to enrollment. Inclusion criteria included: (1) all children with sepsis between the ages of 1 month to 18 years; (2) suspected or confirmed infection; (3) two or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria: tachycardia (heart rate > 2 standard deviation or SD for age), tachypnea (respiratory rate >2 SD for age), temperature > 38°C or < 36°C, total leucocyte count >12,000 or < 4,000 cells/mm 3 or > 10% bands. 11 Exclusion criteria were chronic kidney disease (CKD), cyanotic congenital heart disease, chronic liver disease, inborn error of metabolism, and hematological disorders. Demographic data including age, gender, weight, vital signs, and diagnosis, at the time of PICU admission were recorded. Physiological and laboratory parameters reflecting cardiorespiratory, neurologic, hepatic, renal, and hematological organ dysfunction, including the highest and lowest value recorded during the first 24 hours of PICU admission were prospectively collected. Data elements required for calculation of the SOFA score at the time of admission (SF1) and 72 hours after ICU admission (SF3), as well as treatment and hospital-based outcomes, were captured on standardized forms and subsequently entered into a database for later analysis. The first day of PICU admission, including a minimum of 8 to 12 hours from the time of PICU admission, was considered as Day 1. Day 3 was defined as the time period from PICU admission until 72 and 96 hours following PICU admission. All children were treated as per surviving sepsis campaign guideline recommendations. 12 Each patient was followed until either discharge from the PICU or in-hospital death. Secondary outcomes, including PICU length of stay (LOS), need and duration of mechanical ventilation (DMV), need and duration of vasoactive infusions, and survival to hospital discharge, were also recorded.

Severity of illness scores (PRISM III and PELOD-2) was calculated using a web-based calculator. PRISM III score variables (systolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, mental status, pupillary response, acidosis, pH, PCO 2 , total CO 2 , PaO 2 , glucose, potassium, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, white blood cell count, platelet count, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time) were recorded within 24 hours of admission. 13

The PELOD-2 score evaluates five organ system functions using ten specific and readily available variables: cardiovascular (lactatemia, mean arterial pressure), neurologic (Glasgow coma score and pupillary reaction), respiratory (PaO 2 /FiO 2 ratio, PaCO 2 , invasive ventilation), renal (creatinine), and hematologic variables (white blood cell count and platelets). All variables required for calculation were captured on days 1, 3, and 5. 14

We employed a pediatric SOFA score (pSOFA) developed by Matics and Sanchez-Pinto based on age-adjusted cutoffs for organ dysfunction. 9 The age adjusted mean arterial pressure and serum creatinine level cutoffs for PELOD-2 scoring system were used to determine cardiovascular and renal subscores, respectively. The pediatric version of the Glasgow coma scale was utilized to determine the neurologic component of the pSOFA score. The hepatic, coagulation and respiratory subscores were identical to those outlined in the original SOFA score. The pSOFA scores were calculated on day 1 (SF1) and day 3 (SF3). Δ SOFA score was calculated based on the difference in SOFA score over 72 hours (SF1–SF3) following admission to the PICU.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the predictive ability of the pSOFA to predict mortality utilizing the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC). The secondary outcome measures consisted of the PICU-LOS, necessity, and the duration of both inotropic support by vasoactive infusion score (VIS) and invasive mechanical ventilation in addition to the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Sample Size

Based on the review of the literature, we assumed that the AUC-ROC for pSOFA to predict mortality lies between 80 and 95%. 15 Considering 5% precision and 95% confidence interval (CI), the minimum required sample size would lie between 70 and 245 patients. As a result, we designated an appropriate sample size to be 240 patients.

Statistical Analysis

The qualitative data are summarized by counts and percentages, and quantitative data are summarized by mean and SD/median (IQR or interquartile range). The outcome was compared across different demographics, along with co-morbidities. The qualitative demographic parameters were compared between survivors and nonsurvivors by chi-square test ( p -value < 0.05 considered significant), and quantitative parameters were compared by independent t -test, ignoring mild to moderate evidence of skewedness owing to a sufficiently large sample size. The pSOFA score was further evaluated through use of logistic regression odds ratio (OR) to determine association with mortality, need for RRT and through Poisson regression relative risk (RR) model for the binary outcome measures to include VIS, pediatric intensive care unit- length of stay (PICU-LOS), and DMV.

The estimated probability of mortality was plotted against the pSOFA score by relaxing linearity restriction of a predictor using the generalized additive model technique. The OR with 95% CI was reported for the pSOFA score after adjusting for significant preadmission co-morbidities. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness of fit was applied to the multivariate logistic regression analysis related to mortality and pSOFA score, where a p -value> 0.05 indicates acceptable calibration. The AUC-ROC analysis was done to assess the predictability of different scores (pSOFA, PRISM III, PELOD-2) for mortality. It is usually considered that AUC-ROCs of 1, 0.90 to 0.99, 0.80 to 0.89, 0.70 to 0.79, 0.60 to 0.69, and < 0.60 are considered to be perfect, excellent, very good, good, moderate, and poor predictors of mortality, respectively. The AUC-ROCs of different scoring systems were compared by DeLong test. All tests were two-tailed and a p -value < 0.05 was taken as significant. The statistical software R version 3.5.1 (R Core Team, 2019) was used.

Results

Study Population

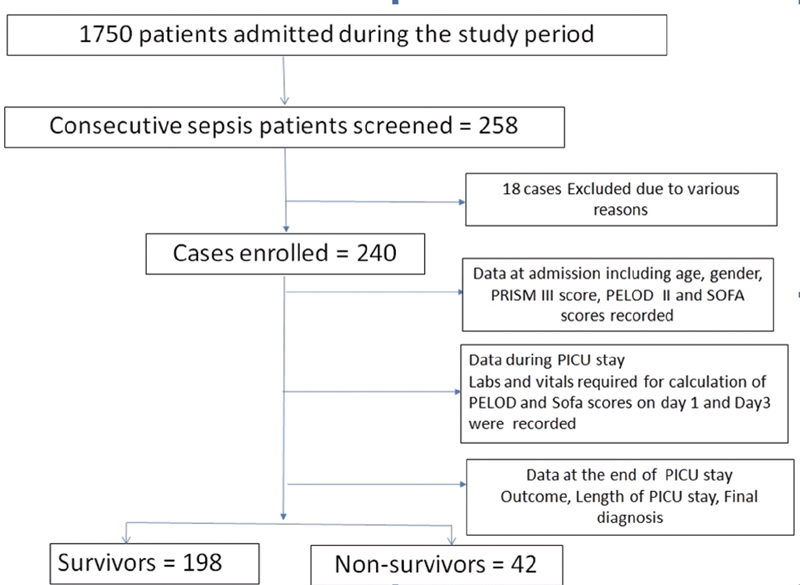

A total of 258 patients presented with sepsis and were screened during the study period of which 240 subjects met the inclusion criteria as shown in Fig. 1 . Eighteen children were excluded for various reasons: seven did not consent, five did not have all the required baseline data necessary for SOFA calculation, and six were children with CKD. Median age of the study population was 36 months (IQR 12–192) and 57.9% were males. A majority (60%) of the study participants were below the age of 5 years. The most common admission diagnosis was related to pulmonary (58%) followed by central nervous system (18%), and gastrointestinal/-genitourinary (15%) organ system issues. Out of 240 patients in the study population, 58% required positive pressure ventilation (including noninvasive ventilation) and 18% children developed acute kidney injury. The mortality rate in the study group was 17.5%. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the enrolled children.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart.

Table 1. Demographic, physiological illness, severity, diagnostic and outcome data in critically ill sepsis children admitted in PICU.

| Variable | Overall | Survivors ( n = 198) | Nonsurvivors ( n = 42) | p -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mo) (median, IQR) | 36 (12, 192) | 36 (12, 96) | 48 (11.8, 96) | 0.9 |

| Gender (% males) | 57.92 | 56.8 | 64.3 | 0.47 |

| Severity illness scores | ||||

| PRISM III (mean, SD) | 8.9 (6.78) | 7.81 (6.01) | 13 (7.25) | < 0.001 a |

| PELOD-D1 (mean, SD) | 16.51 (11.99) | 7.79 (6.24) | 25.6 (12.75) | < 0.001 a |

| PELOD-D3 (mean, SD) | 14.53 (12.62) | 14.4 (10.37) | 29 (12.8) | < 0.001 a |

| SOFA D1 ( mean, SD ) | 6.71 (3.57) | 6 (4) | 10 (3.5) | < 0.001 a |

| SOFA D3 ( mean, SD ) | 6.93 (4.35) | 6 (5) | 13 (3.5) | < 0.001 a |

| AKI ( n , %) | 45 (18) | 31 (12.9) | 14 | <0.01 a |

| Mechanical ventilation ( n , %) | 141 (59) | 99 (50) | 42 (100) | < 0.01 a |

| Length of PICU stay (d) (mean, SD) | 8.01 (6.68) | 7.81 (6.0) | 8.62 (9.21) | 0.59 |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; IQR, interquartile range; PELOD, pediatric logistic organ dysfunction; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PRISM, the pediatric risk of mortality score; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SD, standard deviation; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment score.

p -Value <0.05 is significant.

Key baseline parameters to include age, gender distribution, and admitting diagnosis did not differ between survivors and nonsurvivors. Likewise, the PICU-LOS (7.8 vs. 8.6 days, p = 0.59) and hospital stay were similar. However, nonsurvivors had a higher need for RRT and mechanical ventilation ( p ≤ 0.001).We observed all the severity of illness scores were significantly higher among nonsurvivors versus survivors (PRISM III 13 vs. 7.8, p ≤ 0.001), (PELOD-D1 25.6 vs. 7.8, p ≤ 0.001), (PELOD-D3 29 vs. 14.4, p ≤ 0.001), (SOFA D1 10 vs. 6, p ≤ 0.001), (SOFA D3 13 vs. 6, p ≤ 0.001).

SOFA and Study Outcomes

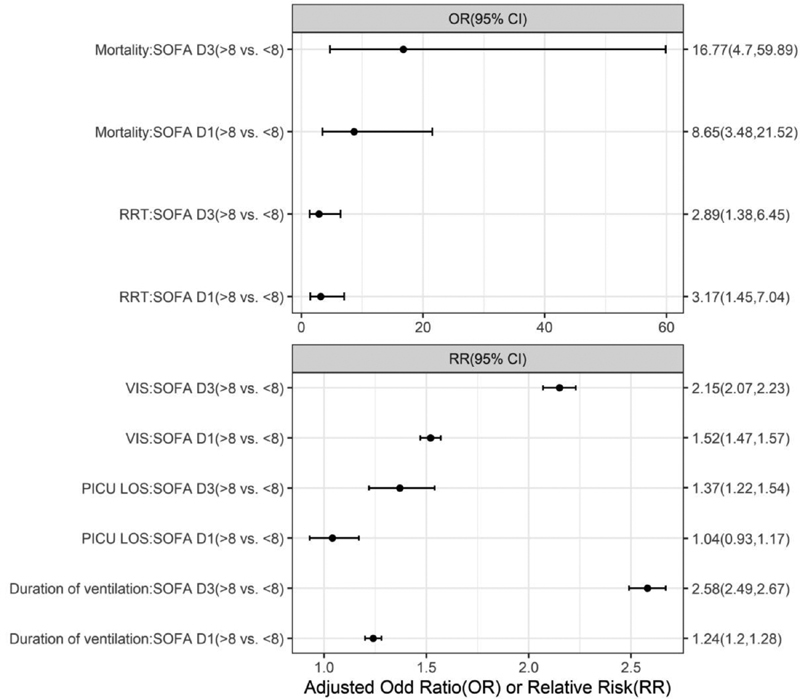

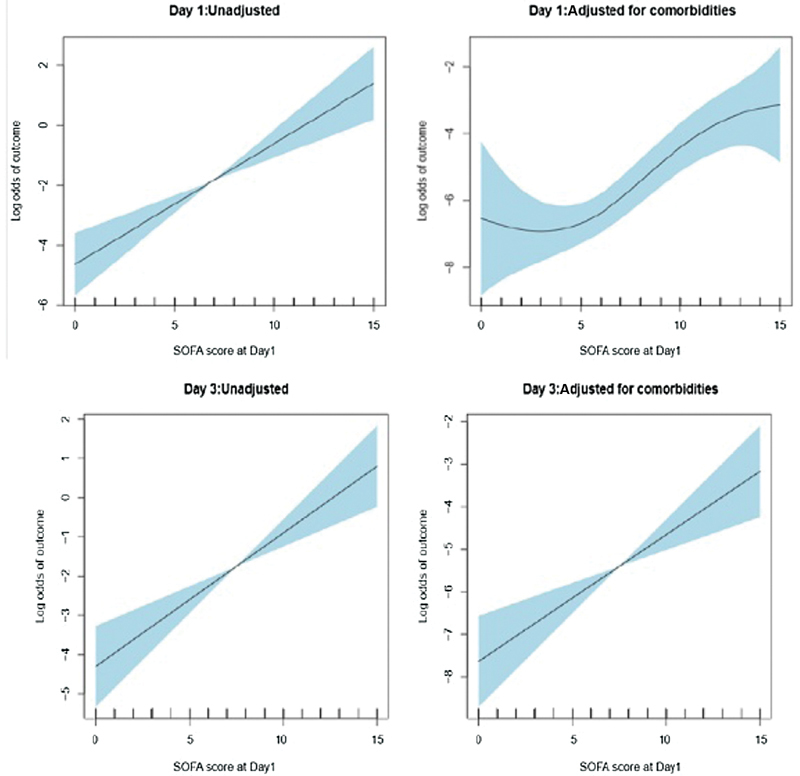

The average pSOFA score SF1 was 6.71+ 3.5 points and SF3 was 6.93 +4.35 points in the study population. We observed proportionate increase in mortality with increase in pSOFA scores. Fig. 2 depicts the association of log odds of mortality and pSOFA score—SF1 and SF3. Nonsurvivors had significantly higher mean SF1 (10 points) and SF3 (13 points) scores as compared with survivors mean SF1 (6 points) and SF3 (6 points) scores, each-with significant p -values (< 0.001). Based on the optimal sensitivity (0.74, 95% CI: 0.6–0.89) and specificity (0.76, CI: 0.68–0.83), a pSOFA score cutoff of 8 points was found to discriminate nonsurvival from survival. The relative risk of prolonged DMV, VIS, and PICU-LOS was significantly higher with pSOFA > 8, on both SF1 and SF3 ( p < 0.05). The multivariate logistic regression, adjusted for preadmission comorbidities, revealed an OR for mortality of 8.65 (95% CI: 3.48–21.52) on SF1 and 16.77 (95% CI: 4.7–59.89) on SF3 utilizing SOFA score above 8 versus those below 8 ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 2.

SOFA vs. outcome. Adjusted effect estimation of SOFA dichotomized by the cutoff 8 on different PICU outcomes by Poisson (relative risk). adj or, adjusted odds ratio; LOS, length of stay; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; RR, relative risk; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment. * p -Value < 0.05 is significant.

Fig. 3.

SOFA score as a Predictor of mortality. The figure depicts association of log odds of outcome with SOFA at different day. The shaded part indicates the 95% confidence band over estimate curves. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

The Hosmer–Lemeshow test for goodness of fit was applied to the multivariate logistic regression related to mortality and pSOFA and indicated good calibration with p -value estimated as 0.85 for SF1 and 0.92 for SF3.

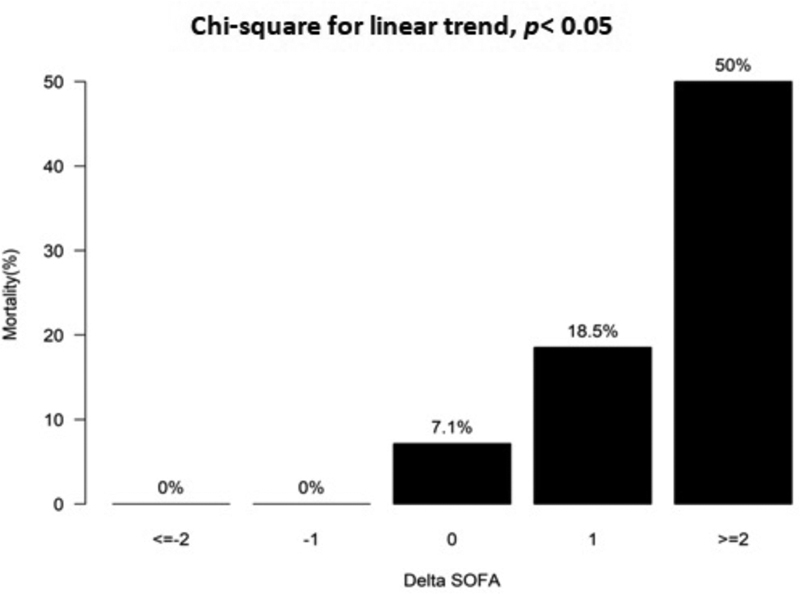

Delta SOFA and Outcome

A positive relationship was found between ΔSOFA (SF1–SF3), and in-hospital mortality ( p < 0.05). Death occurred in 7.1 and 18.5% with ΔSOFA of 0 and 1 point, respectively. The risk of mortality increased exponentially to 50% with ΔSOFA of ≥2 points. However, no mortality was observed with a decline in the ∆SOFA score from SF1 to SF3. Fig. 4 shows the relationship between in-hospital mortality and ΔSOFA.

Fig. 4.

The relationship between Delta (∆)SOFA (SF3-SF1) score and in-hospital mortality. Delta (∆)SOFA calculated by subtracting SOFA score on day 3 and day 1. * p -Value <0.05 is significant. SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Likewise, children with ΔSOFA ≥2 had higher median duration of inotropes (101 hours, [IQR 80–129]) as compared with ΔSOFA < 2 (58.5 hours, [IQR 1.5–111.3]) which was highly statistically significant ( p -value of 0.006) with a correlation co-efficient of 0.21 (95% CI: 0.15–0.35, p -value of 0.01).

Comparison of pSOFA with PELOD-2 and PRISM III

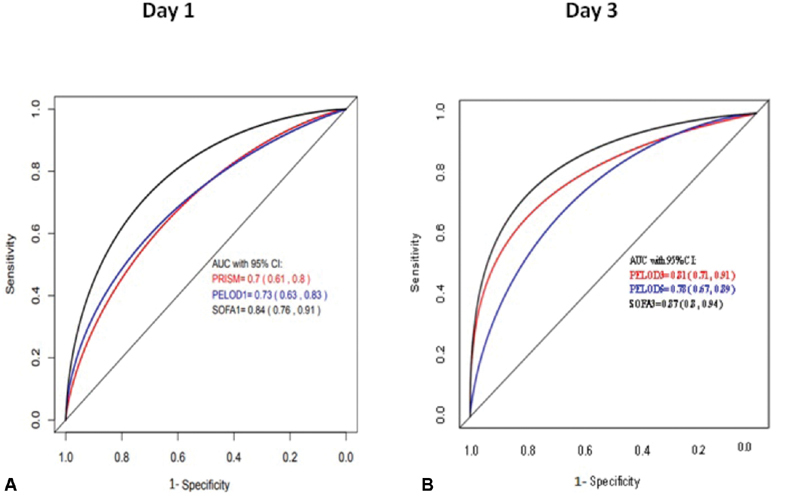

Using Pearson's correlation coefficient, we found a fair association of pSOFA score with PELOD-2 score 0.49, (95% CI: 0.36–0.6). However, there was a weak association of pSOFA with PRISM III score 0.29 (95% CI: 0.14–0.42). AUC-ROC curve was constructed for assessing ability of pSOFA, PRISM III, and PELOD-2 to predict mortality. The performance of pSOFA score on SF1 for predicting in-hospital mortality (AUC, 0.84; 95% CI: 0.76–0.91) was better than the performance of PRISM III (AUC, 0.70; 95% CI: 0.61–0.8) and PELOD-2 (AUC, 0.73; 95% CI: 0.63–0.83; Fig. 5A ). Similar findings were noticed on subsequent comparisons with SF3 (AUC, 0.87; 95% CI: 0.8–0.94) with superior discrimination for predicting mortality compared with PELOD-2 day 3 (AUC −0.81) and PELOD-2 day 5 (AUC −0.78; Fig. 5B ).

Fig. 5.

(A) AUC-ROC for mortality prediction (day 1). SOFA has a larger area under curve and was found to be superior than PRISM III (AUC, 0.7), PELOD-1 (AUC, 0.73) to predict mortality. (B) AUC-ROC for mortality prediction (day 3) on subsequent comparisons on day 3, we found similar AUC for SOFA and superior discrimination for predicting mortality. AUC, area under curve; PELOD-1, Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction 1; PRISM, pediatric risk of mortality; ROC, receiver operating curve; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

The Delong test for comparison was applied to test the AUC of pSOFA to predict the mortality compared with both PRISM III and PELOD-2 scores. Though the magnitude of AUC for pSOFA was greater than the other two scoring system, it was only significantly higher compared with PRISM III ( p -value < 0.001) but not significantly different compared with PELOD-2 ( p -value = 0.101).

Discussion

Sepsis is a common problem for all intensive care units of health care and, in particular—a major cause of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide. 1 16 17 18 Undoubtedly, understanding a patient's risk of mortality is critical, but perhaps more salient to a clinician is the ability to accurately predict individual patient trajectory within the days following admission to the PICU. It is important to recognize those patients who are imminently likely to worsen through vigilance that facilitates earlier and effective interventions leading to improved outcomes. Different scores have been utilized to provide a valuable framework to characterize a patients' severity of illness that enables evaluation of ICU performance for benchmarking purposes and quality improvement initiatives. 18 As a result, review of valuable updates will be required to facilitate regional adaptations to improve patient outcomes in the presence of pediatric sepsis. This prospective study evaluated the age adapted pediatric SOFA score (pSOFA) for predicting in-hospital mortality, including comparisons to other validated pediatric severity of illness commonly used in pediatric patients admitted with a diagnosis of sepsis.

Overall, we observed a mortality rate of 17.5%, which is somewhat less than mortality rate (of over 20%) reported from other studies of the developing countries throughout the world. 19 20

Though all the mortality prediction scores had a statistically significant higher values in nonsurvivors, p < 0.001 ( Table 1 ), our study clearly showed that pSOFA scores (on day 1 and day 3) had a strong ability for predicting in-hospital mortality among septic patients admitted to the PICU involved in this study. We observed a proportionate increase in percentage of mortality in critically ill children with sepsis as the pSOFA score increased from day 1 to 3 ( Fig. 2 ). Our results are in consonance with other studies done in critically ill adult patients where similar findings were observed. 8 21 22 In our study, the pSOFA cutoff to predict mortality was estimated to be greater than 8 points based on optimal sensitivity and specificity identical to the studies performed by Ferreira et al in a prospective observational study in critically ill patients (adults), and a retrospective study done by Travis et al in critically ill children. 9 10 The relative risks of mechanical ventilation, RRT, and PICU-LOS were significantly ( p < 0.05) higher for pSOFA > 8 on both SF1 and SF3. The adjusted OR of mortality was substantially higher (OR 8.65) with SOFA > 8 as compared with SOFA scores of < 8 on day 1 and increased twofold (OR 16) on day 3. Our results regarding change in SOFA score (∆SOFA) are consistent with a study by Jones et al, as they also found a positive correlation with in-hospital mortality rate ( p < 0.05). 22

In our study, we moved a step further in comparing the commonly used severity of illness scores (PRISM III, PELOD-2) in the PICU with pSOFA score as a predictor of outcome. The pSOFA score was able to predict mortality with good discriminative power with AUC = 0.84 which was superior to both PRISM III (AUC, 0.7) and PELOD-2 (AUC, 0.73). Retrospective cohort analysis by Raith et al was performed to externally assess and validate the discriminatory capacities of an increase in SOFA score for outcome in critically ill patients. Their findings were consistent with ours by revealing similar results of the SOFA score (AUC, 0.753) for prediction of in-hospital mortality. 23 In addition, another study by Rivera-Fernández et al, also have demonstrated that 28-day mortality was related to mean and maximum daily SOFA scores in a critically ill patient with an AUC-ROC of 0.95. 24

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of our study is the large sample size. Moreover, due to prospective, quality data collection process, these results were unlikely to be biased. Our study considered in-hospital mortality as a primary end point, but also measured composite secondary outcomes of PICU-LOS and need of RRT and mechanical ventilation, thus assessing the prediction of these outcomes using the pediatric SOFA score. We acknowledge certain limitations in our study as well. We selected a subset of critically ill patients with sepsis; hence generalization of findings cannot be made to children without sepsis. Furthermore, this was a single center study, thereby requiring need for further study to evaluate the general applicability of the pSOFA score through the use of multicentric PICU trials to facilitate greater confidence in our findings through utilization of greater number of patients and serial measurement of variables at regular intervals.

Conclusion

The pSOFA score is a reliable predictor of mortality in pediatric sepsis. An increase in pSOFA score of more than two points from baseline has a significant association with mortality.

Our observations indicate that the pSOFA score may have a strong ability for predicting in-hospital mortality among patients in the PICU, with a prognostic performance statistically superior or similar to other validated pediatric severity of illness scores.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Fisher J D, Nelson D G, Beyersdorf H, Satkowiak L J. Clinical spectrum of shock in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(09):622–625. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181ef04b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanley T P, Hallstrom C, Wong H R.Pediatric Critical Care—4th EditionAccessed November 3, 2019 at:https://www.elsevier.com/books/pediatric-critical-care/Fuhrman/978-0-323-07307-3

- 3.American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force Committee Members . Carcillo J A, Fields A I. Clinical practice parameters for hemodynamic support of pediatric and neonatal patients in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(06):1365–1378. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200206000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarthi M, Lodha R, Vivekanandhan S, Arora N K. Adrenal status in children with septic shock using low-dose stimulation test. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(01):23–28. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000256622.63135.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beal A L, Cerra F B. Multiple organ failure syndrome in the 1990s. Systemic inflammatory response and organ dysfunction. JAMA. 1994;271(03):226–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent J L, Bihari D. Sepsis, severe sepsis or sepsis syndrome: need for clarification. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18(05):255–257. doi: 10.1007/BF01706468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Grandbastien B. Daily estimation of the severity of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in critically ill children. CMAJ. 2010;182(11):1181–1187. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goddard J M. Pediatric risk of mortality scoring overestimates severity of illness in infants. Crit Care Med. 1992;20(12):1662–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira F L, Bota D P, Bross A, Mélot C, Vincent J L. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1754–1758. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matics T J, Sanchez-Pinto L N. Adaptation and validation of a pediatric sequential organ failure assessment score and evaluation of the sepsis-3 definitions in critically ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10):e172352–e172352. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha E J, Kim S, Jin H S. Early changes in SOFA score as a prognostic factor in pediatric oncology patients requiring mechanical ventilatory support. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32(08):e308–e313. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e51338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A; International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis.International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics Pediatr Crit Care Med 20056012–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes A, Evans L E, Alhazzani W. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(03):304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollack M M, Patel K M, Ruttimann U E. PRISM III: an updated pediatric risk of mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(05):743–752. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et Urgences Pédiatriques . Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Deken V, Lacroix J, Leclerc F. Daily estimation of the severity of organ dysfunctions in critically ill children by using the PELOD-2 score. Crit Care. 2015;19(01):324. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlapbach L J, Straney L, Bellomo R, MacLaren G, Pilcher D. Prognostic accuracy of age-adapted SOFA, SIRS, PELOD-2, and qSOFA for in-hospital mortality among children with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(02):179–188. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-5021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arikan A A, Citak A.Pediatric shock—Signa VitaeAccessed October 23, 2019 at:http://www.signavitae.com/2008/04/pediatric-shock/

- 18.Sinniah D.Shock in childrenAccessed October 23, 2019 at:webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:Jw9pJugqsKkJ:https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8485/636ffb90f8816b31f2061538a1481484770e.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=in

- 19.Singh D.(PDF) Mortality rates in pediatric septic shockAccessed October 23, 2019 at:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312632469_Mortality_rates_in_pediatric_septic_shock

- 20.Taori R N, Lahiri K R, Tullu M S. Performance of PRISM (Pediatric Risk of Mortality) score and PIM (pediatric index of mortality) score in a tertiary care pediatric ICU. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77(03):267–271. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khajeh A, Noori N M, Reisi M, Fayyazi A, Mohammadi M, Miri-Aliabad G. Mortality risk prediction by application of pediatric risk of mortality scoring system in pediatric intensive care unit. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23(05):546–550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno R, Vincent J L, Matos R. The use of maximum SOFA score to quantify organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care. Results of a prospective, multicentre study. Working Group on Sepsis related Problems of the ESICM. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(07):686–696. doi: 10.1007/s001340050931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones A E, Trzeciak S, Kline J A. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for predicting outcome in patients with severe sepsis and evidence of hypoperfusion at the time of emergency department presentation. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(05):1649–1654. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819def97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) Centre for Outcomes and Resource Evaluation (CORE) . Raith E P, Udy A A, Bailey M. Prognostic accuracy of the SOFA score, SIRS criteria, and qSOFA score for in-hospital mortality among adults with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2017;317(03):290–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]