Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) and exacerbates disease by promoting inflammation. The present study investigated the safety and mechanisms of action of Staphylococcus hominis A9 (ShA9), a bacterium isolated from healthy human skin, as a topical therapy for AD. ShA9 killed S. aureus on the skin of mice and inhibited expression of a toxin from S. aureus (psmα) that promotes inflammation. A first-in-human, phase 1, double-blinded, randomized 1-week trial of topical ShA9 or vehicle on the forearm skin of 54 adults with S. aureus-positive AD (NCT03151148) met its primary endpoint of safety, and participants receiving ShA9 had fewer adverse events associated with AD. Eczema severity was not significantly different when evaluated in all participants treated with ShA9 but a significant decrease in S. aureus and increased ShA9 DNA were seen and met secondary endpoints. Some S. aureus strains on participants were not directly killed by ShA9, but expression of mRNA for psmα was inhibited in all strains. Improvement in local eczema severity was suggested by post-hoc analysis of participants with S. aureus directly killed by ShA9. These observations demonstrate the safety and potential benefits of bacteriotherapy for AD.

AD is a common disorder with worldwide prevalence rates of 15–20% in children and 1–3% in adults1–3. AD is commonly associated with asthma and allergic conditions and causes significant morbidity due to increased infections as well as a decrease in psychosocial and physical quality of life4. No single cause has been identified for AD. Rather, the pathophysiology of AD appears to involve a variety of factors including host genetics, altered skin barrier function and immunological abnormalities5–8.

AD is frequently characterized by overgrowth of S. aureus9–11, which then triggers proteolytic breakdown of the epidermal barrier and immune dysregulation12. Skin colonization by S. aureus triggers the production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by keratinocytes, exacerbation of T-helper 2 (TH2) cell skewing, and mast cell degranulation13–15. Increases in TH2 cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 suppress the appropriate expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) such as cathelicidin and β-defensins in the skin16. The inability to express an appropriate abundance of AMPs results in further dysregulation of the microbial community on the skin and perpetuation of the disease cycle16–20.

Due to the capacity of S. aureus to exacerbate AD, it has been considered a rational target for therapy. Strain-level identification of S. aureus has suggested that some S. aureus strains isolated from patients with severe AD are capable of eliciting higher levels of epidermal thickening and AD-like skin inflammation in mice21. Strains isolated from patients with severe AD produce higher extracellular proteolytic activity than isolates from patients with less severe disease or healthy participants22. Unfortunately, attempts to use systemic and topical antibiotics, as well as bleach baths, to treat AD have often failed to show either direct killing activity of surface bacteria or improvement in skin inflammation23–25. These failures suggest that classic broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is not a useful approach to improve the skin microbial ecosystems.

In addition to intrinsic AMPs produced by the host, the composition of the microbial community on human skin is strongly influenced by intraspecies competition within the commensal community26. Production of various types of bacteriocins by some strains of skin commensal, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) can selectively inhibit nonresident pathogenic bacteria such as S. aureus, group A streptococci and Escherichia coli on the skin surface26–30. In addition to producing bacteriocins, some CoNS compete with S. aureus by producing small cyclic peptides known as autoinducing peptides (AIPs), which inhibit the S. aureus quorum-sensing system31,32. Most CoNS strains on the skin of healthy adults express both bacteriocins and AIPs, but most patients with AD lack these protective strains of CoNS26,31. Thus, AD skin exhibits deficiencies in both induction of human AMPs and colonization by bacteria that can protect against S. aureus.

Based on the relationship between S. aureus and AD, and the observed deficiency of protective CoNS on the skin of AD patients, we hypothesized that reintroducing a protective strain of CoNS could be an alternative therapeutic strategy for patients with AD. The present study applied preclinical experimental models to evaluate potential therapeutic mechanisms of action and performed a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, phase 1 clinical trial to assess safety and further assess its effect on human skin.

Results

Selection and preclinical testing of beneficial human skin commensal bacteria.

A screen of over 8,000 individual isolates of CoNS bacteria from the skin of healthy subjects identified several strains with the capacity to inhibit the growth of S. aureus in vitro26. These were further evaluated for additional characteristics such as decreased capacity for epidermal barrier damage, sensitivity to common antibiotics, lack of capacity to form a biofilm, selectivity for S. aureus inhibition over other members of the skin microbiome and production of an AIP that can broadly inhibit expression of quorum-sensing gene products by S. aureus. Based on these criteria, a strain of S. hominis (ShA9) was selected for preclinical evaluation in a mouse model of AD11. This bacterial strain has been detected among the skin CoNS community in 21% of healthy subjects and in only 1% of AD patients26.

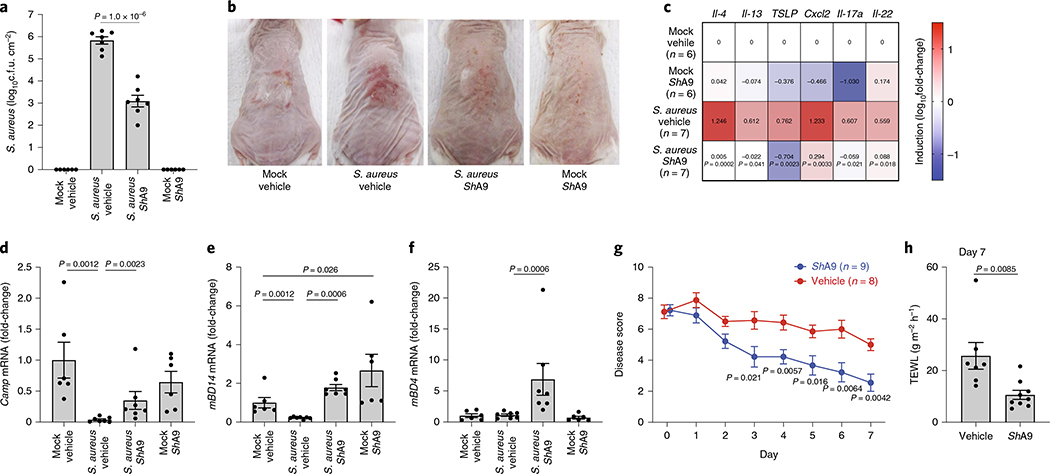

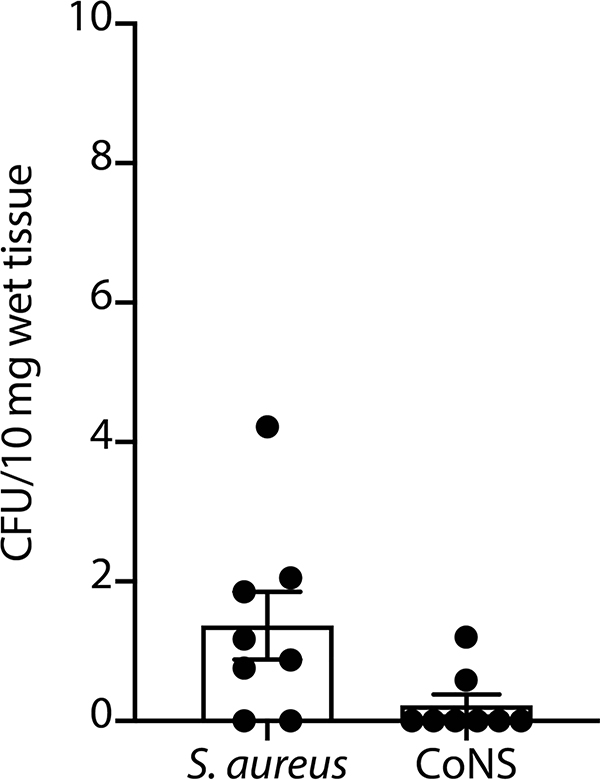

To test the efficacy of ShA9 application against S. aureus in vivo, live ShA9 suspended in Cetaphil lotion and glycerol was applied twice daily for 3 d to the back skin of Flgft/ft Balb/c mice that were sensitized by ovalbumin (OVA) solution and colonized with S. aureus for 4 d ref. 11). ShA9 inhibited S. aureus survival by 99.6% in comparison to vehicle application alone at 3 d (mean difference, 2.74 (log10(c.f.u.), P < 0.0001, where c.f.u. is colony-forming units (Fig. 1a)). ShA9 lotion also improved local erythema (Fig. 1b) and suppressed several genes associated with inflammation in AD, including Il-4, Il-13, Tslp, Cxcl2, Il-17a and Il-22 (Fig. 1c). CoNS were not detected in the spleen after topical application or detected at <1 c.f.u. per 10 mg of tissue, and these levels were below the levels of S. aureus found in the spleen (Extended Data Fig. 1). This suggests a low risk of bacteremia by topical application of ShA9.

Fig. 1 |. Preclinical validation of the activity of ShA9 on mice.

a–f, Analysis of mouse skin after twice-daily topical applications of ShA9 or vehicle for 3 d on OVA-sensitized FLGft/ft Balb/c mice that were colonized by S. aureus for 4 d. Live S. aureus recovered from lesional back skin by swab (a), skin inflammation (b), and relative abundance of mRNA of indicated cytokines (c), Camp (d), mDB14 (e) and mBD4 (f) in skin. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. of biological replicates from independent mice (mock/vehicle: n = 6; S. aureus/vehicle: n = 7; S. aureus/ShA9: n = 7; mock/ShA9: n = 6) (a–f). Mouse images represent similar results from indicated biological replicates (b). g, Time course change in severity of local skin inflammation during extended topical application of ShA9 or vehicle for 1 week on FLGft/ft Balb/c mice treated as in a–f. All data represent mean ± s.e.m. of biological replicates from independent mice (ShA9: n = 9; vehicle: n = 8). h, TEWL of targeted site at day 7. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. of biological replicates from independent mice (ShA9: n = 9; vehicle: n = 7). The P value was calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired, parametric Student’s t-test (a, g and h) or a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test (c and d–f).

AD patients have lower relative expression levels of some host defense peptides due to the suppressive action of TH2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 (ref. 16). The application of ShA9 increased expression of cathelicidin (Camp), murine β-defensin 4 (mBD4) and murine β-defensin 14 (mBD14) (Fig. 1d–f). This observation was consistent with the observed decrease in Il-4 and Il-13 after application of ShA9. This suggested that, in addition to the direct antimicrobial action of lantibiotics, ShA9 can also enhance the host antimicrobial defense system.

Extended application of ShA9 improved the disease score33 in mice in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1g). The 1-week treatment with ShA9 also decreased transepidermal water loss (TEWL) in the AD mouse model (Fig. 1h).

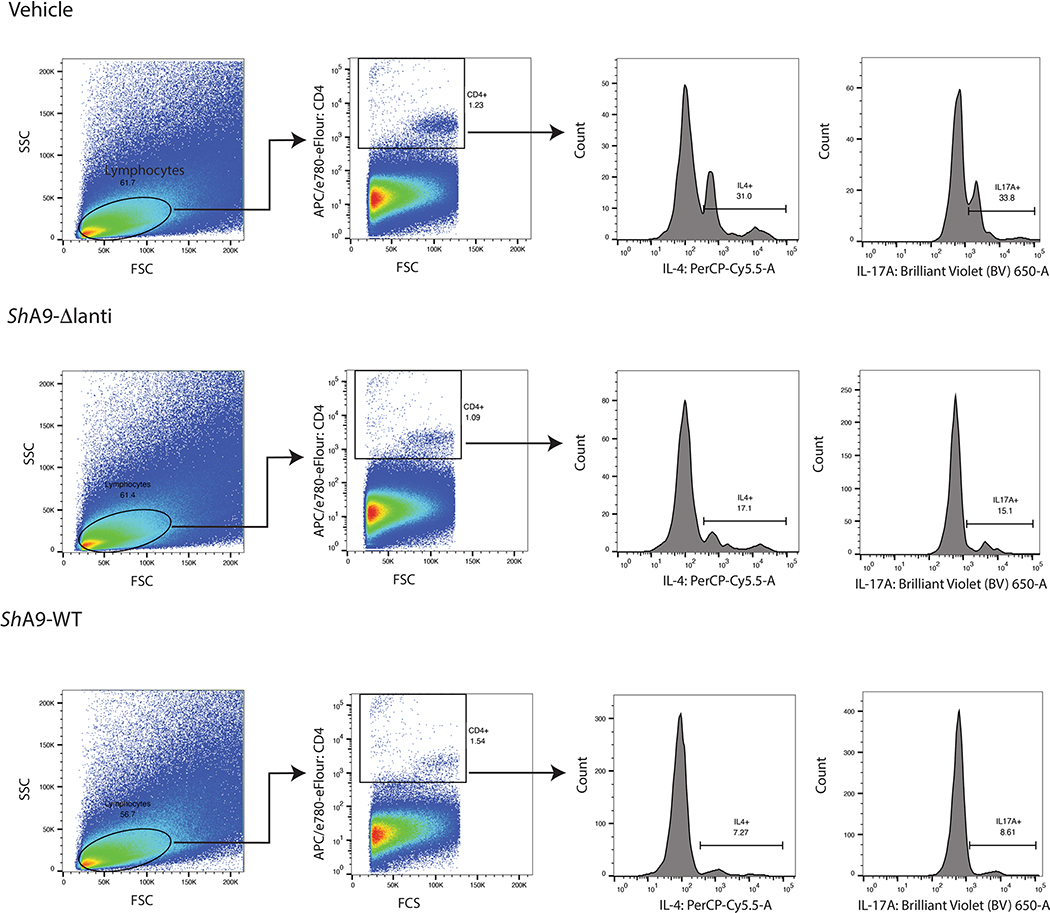

ShA9 can inhibit skin inflammation independent of killing S. aureus.

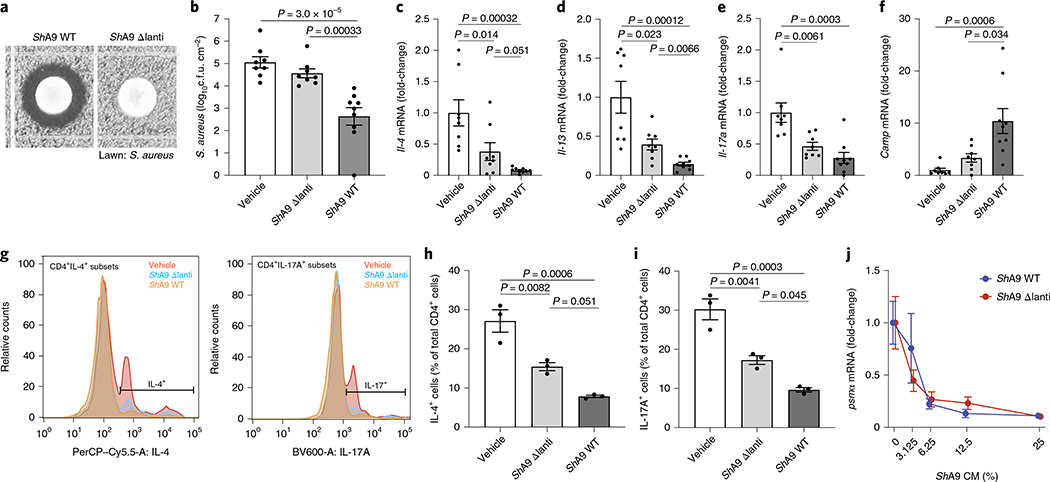

ShA9 produces two lantibiotics with antimicrobial activity against S. aureus26. To investigate whether the anti-inflammatory activity observed after ShA9 application was dependent on killing S. aureus, both lantibiotic genes in ShA9 were deleted by allelic exchange. The mutant ShA9 strain (ShA9-Δlanti) grew equally well on agar compared with wild-type (WT) ShA9, but lost any detectable killing activity against S. aureus growth (Fig. 2a). A comparison of the effect of ShA9-Δlanti with the WT parental strain of ShA9 showed a greatly diminished capacity of ShA9-Δlanti to inhibit the survival of S. aureus on mouse skin (Fig. 2b). However, the ShA9-Δlanti mutant retained a substantial capacity to reduce expression of Il-4, Il-13 and Il-17a, restored the expression of Camp (Fig. 2c–f) and suppressed infiltration of TH2 and TH17 T cells (Fig. 2g–i and Extended Data Fig. 2a–c). ShA9-Δlanti was as efficient as the parental WT in inhibiting expression of messenger RNA for phenol-soluble modulin α (PSMα) (Fig. 2j), a S. aureus toxin that is controlled by quorum sensing and promotes skin inflammation31,33,34. This activity demonstrated that ShA9-Δlanti retained the ability to inhibit quorum sensing despite not inhibiting growth of S. aureus. ShA9 was therefore considered to be a prime candidate for human therapy due to its multiple host defense functions.

Fig. 2 |. Anti-inflammatory action of ShA9 is mediated by mechanisms independent of antimicrobial activity against S. aureus.

a, Radial diffusion assay of S. aureus growth with WT ShA9 and lantibiotic knockout mutant of ShA9 (ShA9-Δlanti). b–f, Live S. aureus recovered from lesional back skin by swab (b) and relative abundance of mRNA of Il-4 (c), Il-13 (d), Il-17a (e) and cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide in skin (f) of Flgft/ft Balb/c mice treated as in Fig. 1a–c with ShA9 WT, ShA9-Δlanti or vehicle. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of biological replicates from independent mice (vehicle: n = 8; ShA9-Δlanti: n = 8; ShA9 WT: n = 9). Expression of each gene was normalized to that of Gapdh (c–f). g, FACS analysis of IL-4+ CD4+ and IL-17A+ CD4+ cells isolated from the skin of mice treated as in Fig. 1a–f after twice-daily topical application of ShA9 WT, ShA9-Δlanti or vehicle for 3 d. Gating strategy for this analysis is shown in Extended Data Fig. 2. h,i, Quantification of numbers of CD4+IL-4+ (h) and CD4+IL-17A+ (i) cells shown in g. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. of biological replicates from independent mice (n = 3). j, Inhibition of psmα mRNA expression by S. aureus (USA300Lac) in culture after exposure to indicated dilutions of conditioned medium (CM) from ShA9 WT or ShA9-Δlanti for 18 h. USA300Lac was resistant to antimicrobial activity from ShA9. Data were normalized against the gyrB gene. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. of technical replicates from individual bacterial cultures (n = 3). The P value was calculated using one-way ANOVA (b–f, h and i). No significant difference was found using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test (P > 0.05) (j).

Assessment of safety of ShA9 on the skin of participants with AD.

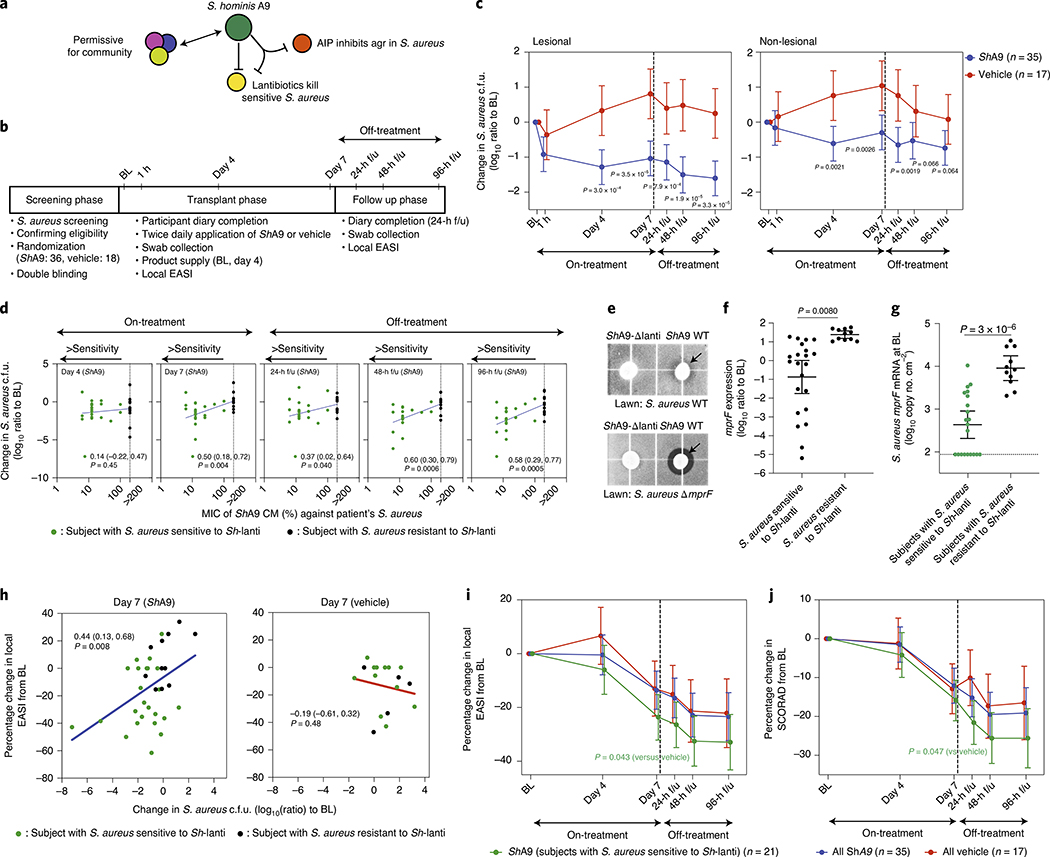

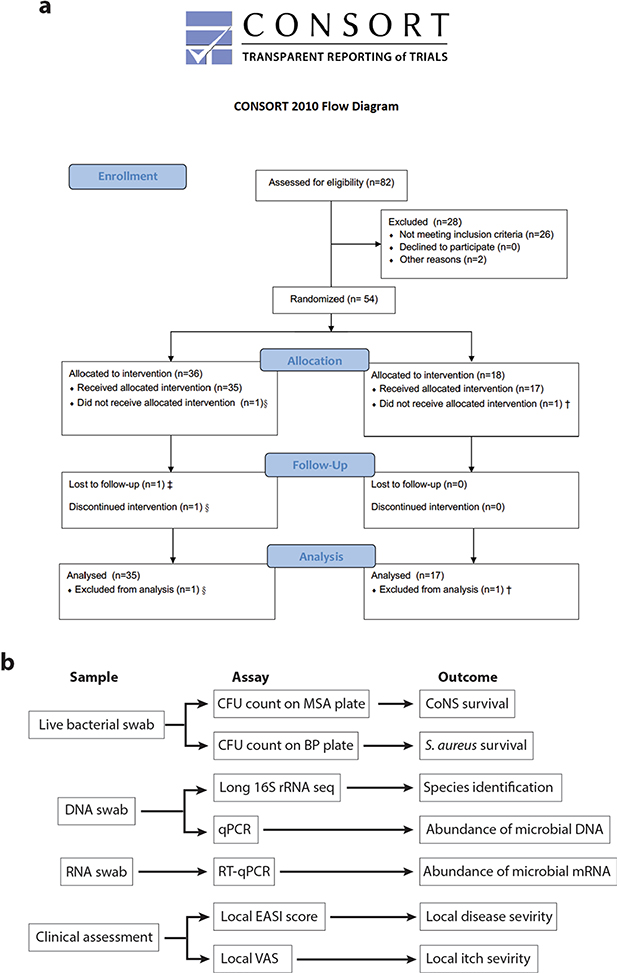

The actions of lantibiotics and the AIP produced by ShA9 are selective against S. aureus compared with other bacteria that coexist within the same community26,31. This selectivity permits survival of other members of the skin microbiome with similar activities, thus further benefiting the community interaction against S. aureus. Combined, these observations suggest the ShA9 can act via three mechanisms: direct killing of S. aureus, inhibition of quorum sensing and promotion of the protective functions of other commensals (Fig. 3a). To test this hypothesis and assess safety in humans as a primary endpoint, we designed a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multisite, phase 1 human clinical trial. Secondary and mechanistic endpoints were designed to better understand the mechanism of action and explore the potential therapeutic efficacy of ShA9 on human skin. Adults (n = 54) with moderate-to-severe AD of the ventral arms, who were culture positive for S. aureus, participated in this trial. Participants with clinically apparent skin infections, open skin wounds, or indwelling foreign or prosthetic devices that could increase the risk of infection were excluded from the present study. Participants were randomized 2:1, with 36 individuals receiving ShA9 and 18 individuals vehicle alone (Fig. 3b). Participant demographic and study completion information are shown in Supplementary Table 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 3a.

Fig. 3 |. Efficacy of ShA9 correlates with sensitivity to lantibiotics.

a, Actions of ShA9 include anti-quorum sensing and selective antimicrobial action against S. aureus. b, Study design for topical application of ShA9 on adults with AD colonized by S. aureus. c, Live S. aureus colony-forming units recovered by swab at baseline (BL), 1 h after initial application, during treatment or after the last dose (off-treatment). Data represent mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI) (ShA9: n = 35; vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects). d, Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ShA9 CM against S. aureus isolated from each participant compared with change in S. aureus colony-forming units from the BL on lesional skin treated with ShA9. CM was precipitated by ammonium sulfate and the percentage calculated from the original volume of medium. The dotted line represents the detection limit of the assay. The change in S. aureus survival at each time point correlated to the MIC of S. aureus isolated from BL swabs, to show how S. aureus that originally colonized participants at BL responds to ShA9 (ShA9: n = 32; vehicle: n = 16 independent subjects). e, Radial diffusion assay for activity of ShA9 WT and the ShA9-Δlanti mutant against S. aureus WT and ΔmprF mutant. The arrow shows the zone of inhibition of S. aureus. f, The expression of mprF in S. aureus that was sensitive or resistant to ShA9. Data represent mean ± 95% CI of data from independent S. aureus strains from distinct subjects (sensitive to ShA9: n = 21; resistant to ShA9: n = 11). g, Abundance of S. aureus mprF mRNA on the surface of lesional skin of participants with S. aureus sensitive or resistant to ShA9. Data represent mean ± 95% CI (sensitive to ShA9: n = 21; resistant to ShA9: n = 11 independent subjects). h, Pearson’s correlation between relative change in live S. aureus abundance and change in local EASI from BL at day 7, for participants treated with ShA9 (blue) or vehicle (red) (ShA9: n = 35, vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects). Participants with S. aureus killed by ShA9 are shown in green and those with high MIC in black. Data at all time points are shown in Extended Data Fig. 5b. i,j, Change in local EASI (i) and SCORAD score (j) in all participants, and in those participants with S. aureus that was sensitive to direct killing by ShA9 compared with participants treated with vehicle. Data represent mean ± 95% CI (all ShA9: n = 35; ShA9 with S. aureus sensitive to ShA9 lantibiotic: n = 21; vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects). A linear mixed-model approach was used to take into account the repeated aspect of the trial (c). Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by two-tailed, Student’s t-test distribution. The P value was calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired, parametric Student’s t-test (f, and g) or a random-effects linear model (i and j).

ShA9 or vehicle was applied topically to the ventral forearms twice daily for 7 d. Clinical assessments and skin swabs were obtained during the treatment phase before and at 1 h after the first application on day 1. On days 4 and 7 of treatment, swabs were collected within 4 h of the first application of ShA9 or vehicle on that day. Blinded physician assessments and skin swabs were also obtained at 24, 48 and 96 h after the final dose on day 7 (Fig. 3b). Phone follow-up assessments were conducted approximately 30 d after the last dose.

The primary endpoint of this trial was to assess safety through day 8 in comparison to vehicle. The per-participant, treatment-emergent, adverse event (AE) rate was 0.19 for ShA9 and 0.34 for vehicle (mean ratio, P = 0.075). There were no serious AEs (SAEs) reported and no AE led to discontinuation of study treatment. Participants were required to fill out a daily diary, recording on a numerical scale of 1–10 their eczema, swelling and pain. This AE-reporting system captured the normal fluctuation of eczema and resulted in any subjective report of fluctuation over baseline to be considered an AE. For this reason, 83.3% of the participants on vehicle were recorded as an AE and 55.6% who received ShA9 were recorded as an AE. Based on this reporting system, there were significantly fewer AEs in participants treated with ShA9 compared with vehicle (P = 0.044) (Table 1); 95% and 93% of the AEs in the active and vehicle group, respectively, were mild, consisting primarily of solicited categories associated with the normal course of AD such as eczema (38.9% active, 55.6% vehicle, P = 0.245), pain (33.3% active, 38.9% vehicle, P = 0.687) and swelling (22.2% active, 22.2% vehicle, P > 0.999) (Table 2). One 44-year-old male participant in the treatment group developed a furuncle on day 6, which was reported as a moderate AE and resolved without fever or chills with warm compresses, and required no antibiotics. The frequency of these AEs was consistent with prior reports of these symptoms during the typical course of AD35.

Table 1 |.

Assessments of AEs and clinical outcomes in subjects treated with ShA9 or vehicle: treatment-emergent AEs—summary through 8 d

| ShA9 (n = 3) n (%) (count) | Vehicle (n = 18) n (%) (count) | Total (n = 54) n (%) (count) | Risk difference (95% Ci)a | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 20 (55.6) (63) | 15 (83.3) (55) | 35 (64.8) (118) | −0.28 (−0.514, −0.041) | 0.044 |

| Any SAE | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | ||

| Any AE leading to study treatment discontinuation | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | ||

| Any AE leading to death | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | ||

| Any AE related/possibly related to study treatment | 18 (50.0) (60) | 14 (77.8) (53) | 32 (59.3) (113) | −0.28 (−0.530, −0.026) | 0.050 |

| Any SAE | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 0 (0.0) (0) | ||

| Any moderate AE | 1 (2.8) (2) | 1 (5.6) (1) | 2 (3.7) (3) | −0.03 (−0.245, 0.112) | >0.999 |

| Any mild AE | 19 (52.8) (61) | 14 (77.8) (54) | 33 (61.1) (115) | −0.25 (−0.502, 0.002) | 0.076 |

n, number of subjects reporting at least one AE in the applicable category. %, percentage of subjects among treatment group; count, count of AEs within the applicable category. Note: at each level of summarization, subjects reporting more than one AE are only counted once.

95% exact unconditional CIs (based on the Santner and Snell method); P values are based on the chi-squared test (if expected cell counts are all >5) or the two-sided Fisher’s exact test.

Table 2 |.

Treatment-emergent AEs though system organ class/preferred term through 8 d

| ShA9 (n = 3) n (%) (count) | Vehicle (n = 18) n (%) (count) | Total (n = 54) n (%) (count) | Risk difference (95% Cl)a | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 20 (55.6) (63) | 15 (83.3) (55) | 35 (64.8) (118) | −0.28 (−0.514, −0.041) | 0.044 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 14 (38.9) (24) | 11 (61.1) (24) | 25 (46.3) (48) | −0.22 (−0.498, 0.054) | 0.123 |

| Eczemab | 14 (38.9) (24) | 10 (55.6) (22) | 24 (44.4) (46) | −0.17 (−0.446, 0.113) | 0.245 |

| Pruritus | 0 (0.0) (0) | 1 (5.6) (2) | 1 (1.9) (2) | −0.06 (−0.274, 0.054) | 0.333 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 12 (33.3) (21) | 7 (38.9) (18) | 19 (35.2) (39) | −0.06 (−0.328, 0.217) | 0.687 |

| Pain in extremityb | 12 (33.3) (21) | 7 (38.9) (18) | 19 (35.2) (39) | −0.06 (−0.328, 0.217) | 0.687 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 9 (25.0) (15) | 4 (22.2) (11) | 13 (24.1) (26) | 0.03 (−0.245, 0.255) | >0.999 |

| Peripheral swellingb | 8 (22.2) (14) | 4 (22.2) (11) | 12 (22.2) (25) | 0.00 (−0.274, 0.224) | >0.999 |

| Chillsb | 1 (2.8) (1) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 1 (1.9) (1) | 0.03 (−0.162, 0.150) | >0.999 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 2 (5.6) (2) | 1 (5.6) (1) | 3 (5.6) (3) | 0.00 (−0.220, 0.149) | >0.999 |

| Abdominal pain upper | 1 (2.8) (1) | 1 (5.6) (1) | 2 (3.7) (2) | −0.03 (−0.245, 0.112) | >0.999 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 1 (2.8) (1) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 1 (1.9) (1) | 0.03 (−0.162, 0.150) | >0.999 |

| Infections and infestations | 1 (2.8) (1) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 1 (1.9) (1) | 0.03 (−0.162, 0.150) | >0.999 |

| Furuncle | 1 (2.8) (1) | 0 (0.0) (0) | 1 (1.9) (1) | 0.03 (−0.162, 0.150) | >0.999 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 (0.0) (0) | 1 (5.6) (1) | 1 (1.9) (1) | −0.06 (−0.274, 0.054) | 0.333 |

| Dysmenorrhea | 0 (0.0) (0) | 1 (5.6) (1) | 1 (1.9) (1) | −0.06 (−0.274, 0.054) | 0.333 |

Note: at each level of summarization, subjects reporting more than one AE are only counted once. Note: incidences are displayed in descending order of frequency of system organ class and by descending order of frequency of preferred term within system organ class. Note: system organ class/preferred term is based on v.20.0 of the MedDRA coding dictionary.

95% exact unconditional CIs (based on the Santner and Snell method); P values are based on the chi-squared test (if expected cell counts are all >5) or the two-sided Fisher's exact test. n, number of subjects reporting at least one AE with system organ class/preferred term. %, percentage of subjects among treatment group; count, count of AEs within system prgan class/preferred term.

Symptom based on subjective daily diary reporting by participants.

S. aureus colonization is reduced by topical application of ShA9.

Secondary and mechanistic endpoints were included in the present study to assess bacterial survival, bacterial DNA and bacterial mRNA expression as a measure of the function of the bacteria present on participants with AD (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Despite the short trial period, the local clinical response at the site of application was also assessed. Clinical response to ShA9 or vehicle was evaluated at the site of application by blinded physician assessment using both local EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index) methodology for the assessment of inflammatory eczema and SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) for the assessment of global extent, severity and subjective symptoms. ShA9 reduced the colony-forming units of S. aureus detectable on lesional and nonlesional skin during treatment (at days 4 and 7) and after treatment in the 96-h follow-up (96-h f/u) phase (Fig. 3c). As the antimicrobial activity of ShA9 is selective against some strains of S. aureus, including against clinical isolates from AD26, we also measured individual isolates of S. aureus recovered from each participant’s baseline swab for their sensitivity to ShA9 in vitro. Most individuals were colonized with strains of S. aureus that were sensitive to growth inhibition by ShA9. Sensitivity to killing in vitro correlated with a change in S. aureus abundance on the participant’s skin at day 7 and during the follow-up phase (Fig. 3d).

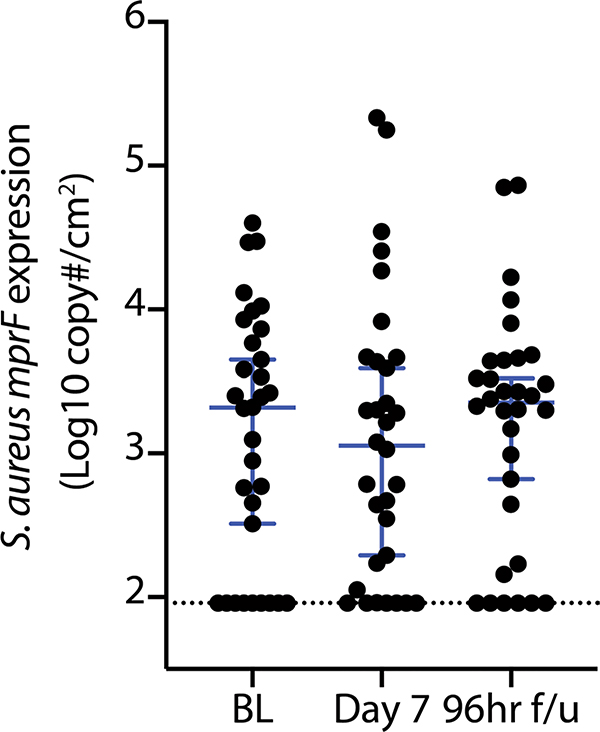

We next evaluated individual isolates of S. aureus recovered from participants that were not directly killed by ShA9 lantibiotic action. Multiple peptide resistance factor (mprF) is a gene expressed by S. aureus that has been previously reported to confer resistance to AMPs. We observed that S. aureus lacking expression of mprF (ΔmprF) was more sensitive to killing by ShA9 in vitro than the WT parental strain (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, S. aureus isolated from participants with AD that expressed higher amounts of mprF were more resistant to the antimicrobial activity of ShA9 (Fig. 3f). Participants colonized by S. aureus that was not directly killed by ShA9 also had greater amounts of mprF mRNA isolated from lesional skin than participants colonized by S. aureus sensitive to ShA9 lantibiotics (Fig. 3g). These data suggested that mprF expression by S. aureus influences the capacity of ShA9 to directly inhibit S. aureus survival. No increase in the abundance of S. aureus mprF mRNA compared with baseline was detected on lesional skin of participants treated by ShA9 at day 7 or at 96 h after the end of therapy (Extended Data Fig. 4).

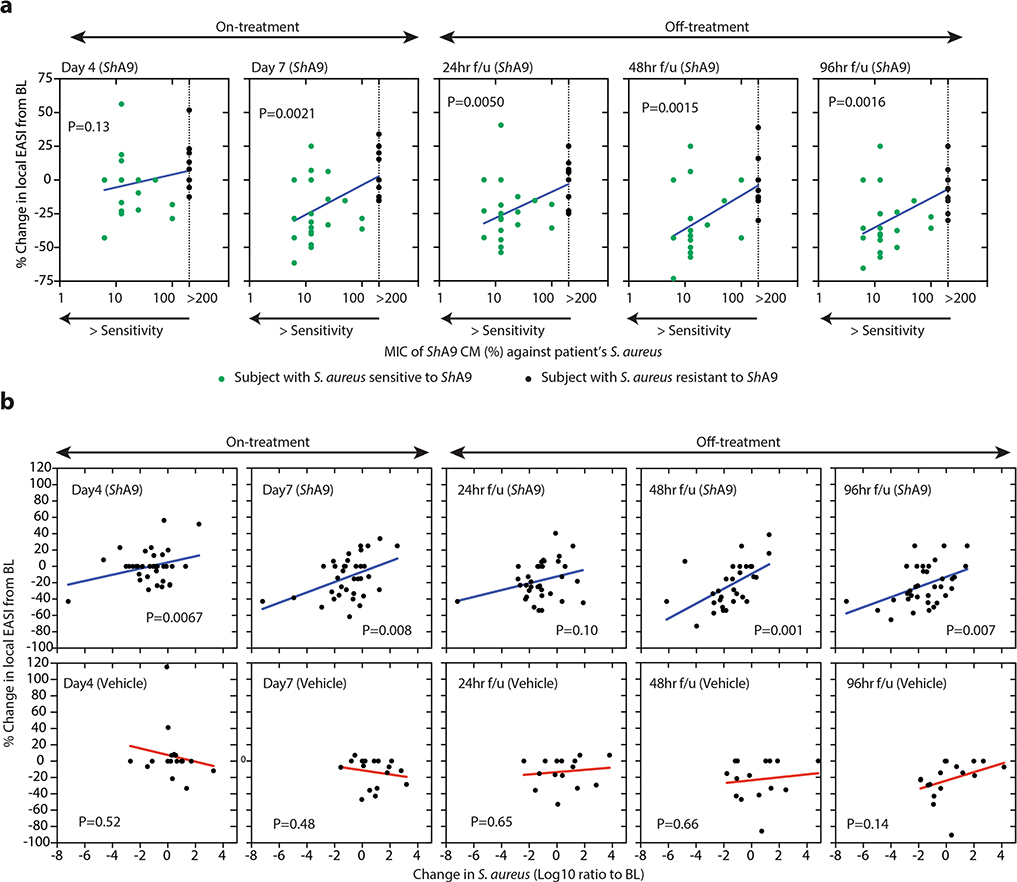

Improvement in local inflammation correlates with killing of S. aureus by ShA9.

A correlation was observed between the capacity of ShA9 to kill S. aureus strains isolated from each participant, the survival of S. aureus on lesional skin and an improvement in the local EASI of all participants treated with ShA9, but not in participants treated with vehicle (Fig. 3h and Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Among all participants treated with ShA9, no significant difference was seen in clinical outcomes as assessed by local EASI or SCORAD score (Fig. 3i,j and Supplementary Table 2). However, a post-hoc analysis of the 21 participants with S. aureus that was sensitive to direct killing by ShA9 showed improvement in both local EASI and SCORAD score after 7 d of treatment, and this improvement persisted up to 96 h after treatment was discontinued (Fig. 3i,j and Supplementary Table 2). No significant change in visual analog scale (VAS) score was observed in either group. These observations support a role for S. aureus in the pathogenesis of AD and suggest that topical application of a rationally selected human commensal can benefit some patients with AD.

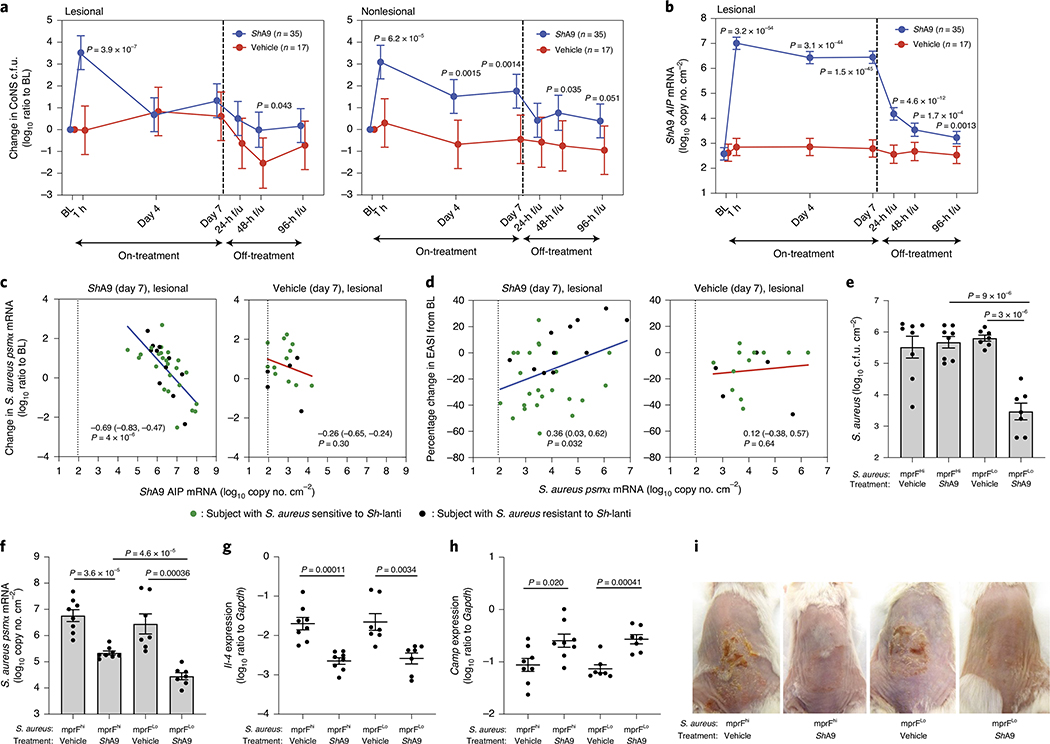

Survival and transcriptional activity by ShA9 on atopic skin.

PCR measurements of DNA can sensitively and specifically detect the presence of an individual strain, but this may not correlate with the survival of the microbe or its ability to express relevant metabolites26. Therefore, to assess the capacity of ShA9 to persist on the skin, we measured bacterial abundance by multiple approaches including colony counting of total CoNS as a surrogate measurement of ShA9. Both lesional and nonlesional skin showed a 3- to 4-log(increase) in live CoNS on the skin 1 h after the first application of ShA9, but no change after application of the vehicle alone (Fig. 4a). However, at days 4 and 7, skin swabs were collected approximately 4 h after the morning application, and swabs taken from lesional skin on these days showed that live CoNS had decreased to a level similar to the baseline. This suggested that the 4-h period between the morning application of ShA9 and the skin sampling resulted in a decrease in the live ShA9 recoverable by swab. In contrast, CoNS recovered – from nonlesional skin were greater in number on both days 4 and 7 for participants treated with ShA9 compared with vehicle (Fig. 4a). It is interesting that a higher level of CoNS was still detected on nonlesional skin even 96 h after the last application.

Fig. 4 |. Survival of ShA9 on AD skin and correlations to autoinducing peptide expression.

a, Change in live CoNS recovered by skin swab from patient’s skin compared with baseline at indicated time points after application of ShA9 or vehicle. b, Abundance of ShA9 AIP mRNA recovered by skin swabs from lesional skin at indicated time points for participants treated with ShA9 or vehicle. Data represent mean ± 95% CI (ShA9: n = 35; vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects) (a and b). c, Correlation between absolute ShA9 AIP mRNA copy number and change in psmα mRNA on lesional skin of participants treated with ShA9 or vehicle at the indicated time points. d, Correlation between change in the local EASI and absolute abundance of psmα mRNA copy number on lesional skin of participants treated with ShA9 or vehicle at day 7 (ShA9: n = 35; vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects). Data from participants with S. aureus both sensitive to ShA9 (green dots) and resistant (black dots) are shown (c and d). The dotted line represents the detection limit of the assay (c and d). e–i, Representative S. aureus strains from participants with high expression of mprF (mprFhi) or low expression (mprFlo) were applied to Flgft/ft Balb/c mice treated with OVA. Survival of S. aureus recovered from lesional back skin by swab is measured by colony-forming units (e). Abundance of psmα mRNA recovered from lesional back skin by swab (f), expression of Il-4 mRNA (g) and Camp mRNA (h) extracted from whole skin, and skin inflammation observed in each group (i) are shown. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. with individual results shown for each mouse (mprFhi, vehicle: n = 9; mprFhi, ShA9: n = 8; mprFLo, vehicle: n = 7; mprFLo, ShA9: n = 7). Mouse images represent similar results from indicated biological replicates (i). A linear mixed-model approach was used to take into account the repeated aspect of the trial (a and b). Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out using a two-tailed, Student’s t-test distribution (c and d). The P value was calculated using two-tailed, unpaired, parametric Student’s t-test (e–h).

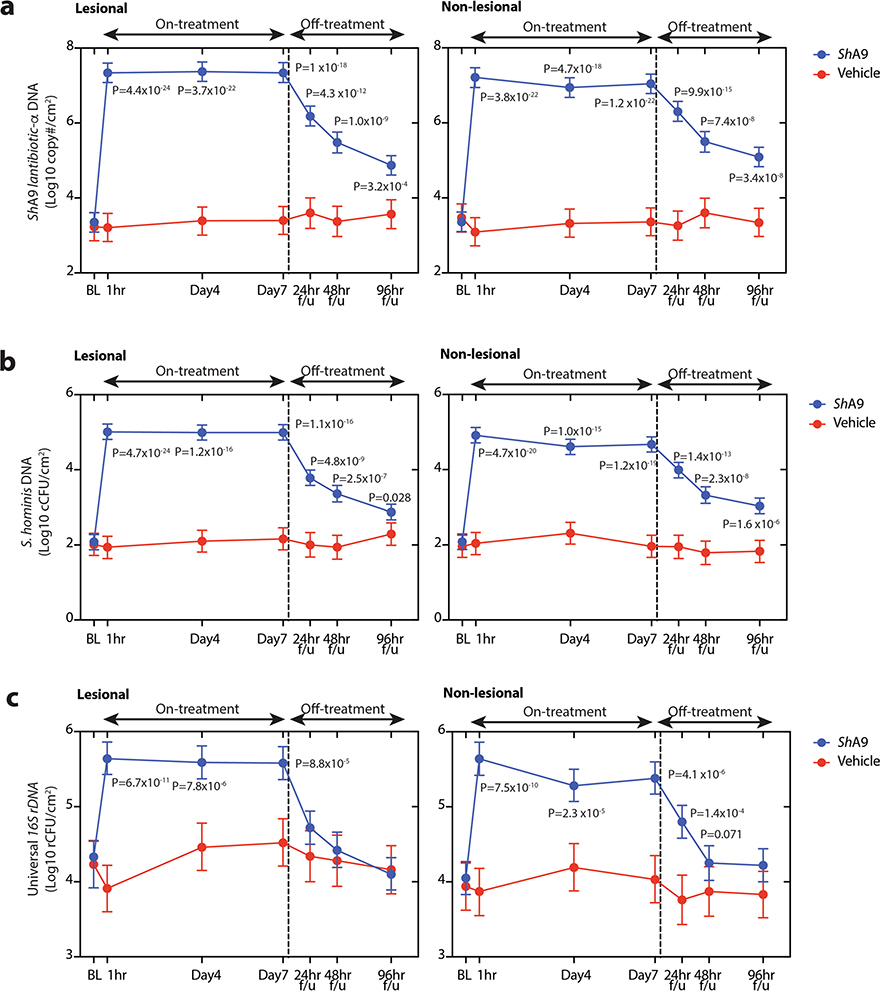

ShA9 DNA abundance was also measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using gene-specific primers for lantibiotic-α of ShA9, or species-specific primers for S. hominis, or for all bacteria using universal 16S primers (Supplementary Table 3). DNA for the S. hominis lantibiotic-α, S. hominis and 16S rDNA was increased at all time points on both lesional and nonlesional skin treated with ShA9 (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). Compared with live colony-forming unit measurements, these results suggest that ShA9 was effectively delivered to both lesional and nonlesional sites.

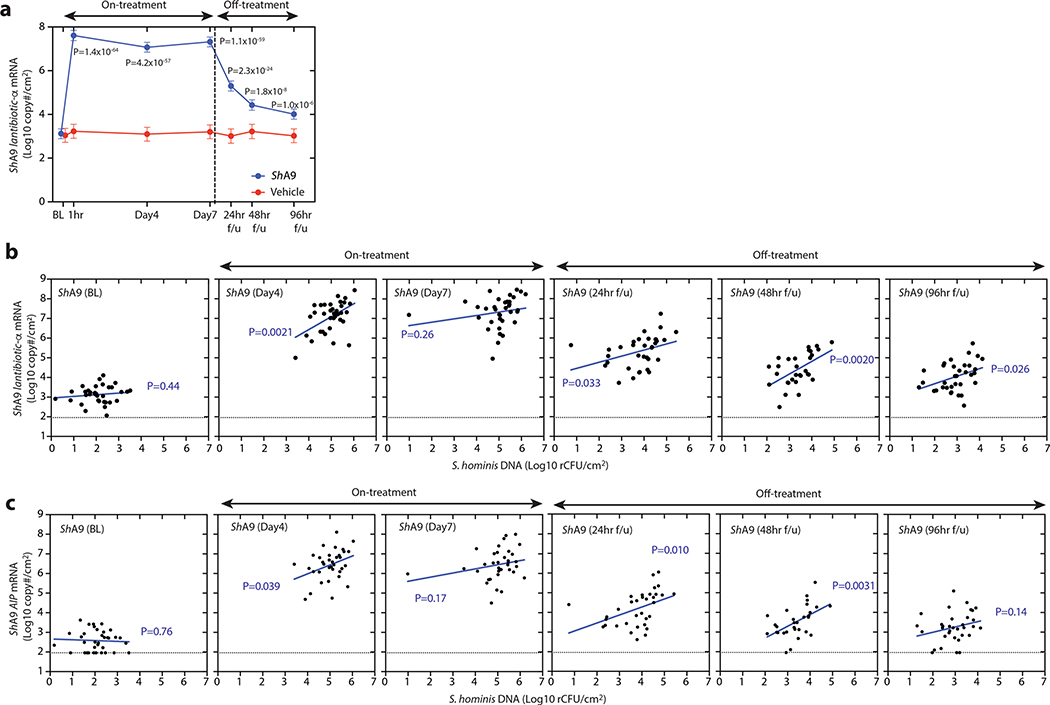

To assess the transcriptional activity from bacteria on study participants, we also measured lesional skin for the abundance of mRNA for ShA9 lantibiotic-α and its AIP31 (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 7a). The mRNA for both genes was increased on lesional skin during treatment (days 4 and 7) and in the follow-up period (24, 48 and 96 h) in the ShA9-treated group compared with baseline, whereas it did not increase in the vehicle-treated group. The abundance of mRNA for ShA9 lantibiotic-α or AIP correlated with abundance of DNA for total S. hominis (Extended Data Fig. 7b,c). These data suggest that, despite a decrease in survival of total CoNS, metabolic products of ShA9 remain and/or some ShA9 applied to skin may have remained transcriptionally active for several days after the end of treatment.

AIP expression correlates with reduced psmα and improved EASI.

Results reported in Fig. 2 suggested that production of AIP by ShA9, and the subsequent capacity to inhibit quorum sensing by S. aureus, may also benefit AD by a mechanism independent of the capacity to kill S. aureus. Increased AIP transcripts were detectable on lesional skin for up to 96 h after ShA9 application and correlated with the abundance of S. hominis DNA (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 7c). The expression of psmα, an important virulence factor of S. aureus31,33,34, inversely correlated with the expression of ShA9 AIP at day 7 of treatment in the ShA9-treated group, but not in the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, improvement in local EASI correlated with decreased psmα mRNA expression at day 7 in the ShA9-treated group, but not in the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 4d). The inhibition of psmα expression by ShA9 AIP was due not only to killing of S. aureus because the drop of psmα expression did not correlate with the capacity of ShA9 to inhibit either S. aureus growth in vitro or survival of S. aureus on AD lesional skin (Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9). ShA9 was capable of inhibiting psmα expression in culture in all S. aureus isolates, independent of lantibiotic resistance (Extended Data Fig. 10).

A murine AD model was next deployed to further confirm the clinical observation that the inhibitory action of ShA9 AIP against psmα toxin expression can be independent of the capacity of ShA9 lantibiotics to kill S. aureus. Mice were colonized with clinical isolates of S. aureus with high mprF expression (mprFHi) and compared with mice colonized with S. aureus with low mprF expression (mprFLo). Treatment with ShA9 did not reduce survival of mprFHi S. aureus but did greatly decrease colonization by the mprFLo S. aureus strain (Fig. 4e). In contrast, ShA9 application suppressed expression of psmα mRNA on all mice colonized by either the mprFHi or the mprFLo S. aureus strains (Fig. 4f). ShA9 also suppressed expression of Il-4, enhanced expression of Camp, and improved inflammation in mice colonized by either the mprFHi S. aureus strains or the mprFLo strains (Fig. 4g,h,i). These data demonstrate that application of ShA9 exerts a potential beneficial function against all S. aureus strains by suppression of the agr quorum-sensing system, and this can occur independent of the sensitivity to killing by ShA9 lantibiotics.

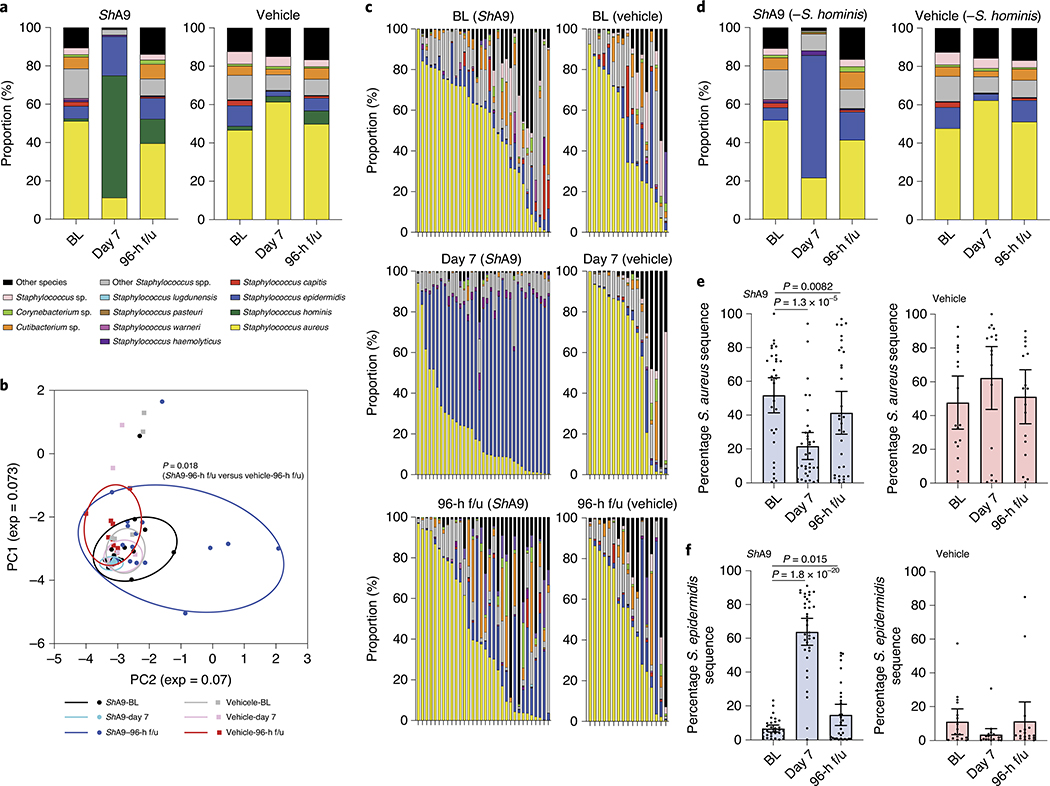

Selective activity of ShA9 on the AD skin microbiome.

To investigate the influence of ShA9 on the overall bacterial community on AD lesional skin, we conducted full-length sequencing of V1–V9 of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. Consistent with data in Figs. 3c and 4a, application of ShA9 decreased the frequency of sequence reads for S. aureus and expanded the relative proportion of S. hominis (Fig. 5a). Principal component analysis (PCA) suggested that application of ShA9 altered the composition of the AD microbiome at 96 h after completion of treatment, compared with that on the skin treated by vehicle (Fig. 5b). Taxa analysis after subtraction of sequence reads attributable to the application of S. hominis revealed an expansion of S. epidermidis at day 7 and 96-h f/u in the active treatment cohort that was not seen in the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 5c–f). The expansion of S. epidermidis was not proportionate to the decrease in S. aureus. These data suggest that application of ShA9 may facilitate recolonization of other CoNS species on AD lesional skin.

Fig. 5 |. Bacterial species on the skin of participants treated with ShA9.

a, Full-length 16S sequencing analysis of the relative abundance of bacterial species on lesional skin of AD participants at baseline (BL), after 1-week treatment with ShA9 or vehicle (day 7) and 96 h after the end of treatment (96-h f/u). b, PCA plot displaying composition of bacterial community at BL, day 7 and 96-h f/u. Statistical analyses were conducted by paired, parametric Student’s t-test on the relative distance of each dot. c, Relative proportion of bacterial species on individuals treated by ShA9 or vehicle is shown after subtraction of S. hominis. d, Individual subject data from c are averaged showing bacterial species on lesional skin at BL, day 7 and 96-h f/u. e,f, Relative abundance of S. aureus 16S rRNA gene (e) and S. epidermidis 16S rRNA gene (f) determined from c. Data represent average (a and d) or mean ± 95% CI (e and f) (ShA9, BL: n = 33; ShA9, day 7: n = 33; ShA9, 96-h f/u: n = 33; vehicle, BL: n = 16; vehicle, day 7: n = 17; vehicle, 96-h f/u: n = 17 independent subjects) (a–f). Only data from >1,000 contigs were shown and data with <1,000 contigs were excluded (a–f). The P value was calculated using the two-tailed, paired, parametric Student’s t-test (b, e and f).

Discussion

Current evidence suggests that a cycle is established whereby a bidirectional causal relationship exists on the skin: the host affects the microbiome and the microbiome affects the host36. We hypothesized that by correcting the skin microbial ecosystem with targeted bacteriotherapy by a bacterium selected from healthy human skin, we could break the vicious cycle of S. aureus colonization and thereby improve skin immune and barrier dysfunction characteristic of AD. Our observations in mice supported the rationale for this intervention. Furthermore, data from this phase 1 trial showed the safety of this approach in humans with AD and a potent capacity to influence S. aureus survival in most participants. In the short term, in a 1-week application period no significant improvement in clinical assessments was observed in the overall population. However, a post-hoc analysis of a major subgroup of AD participants who were colonized by S. aureus sensitive to killing by ShA9 showed significant clinical improvement compared with vehicle. Improved clinical outcomes also correlated with decreased expression of mprF by S. aureus and the susceptibility of S. aureus with killing by ShA9 in all participants. Furthermore, analysis of psmα mRNA expression suggested that those participants with S. aureus not killed by ShA9 were still sensitive to inhibition of toxin production, a mechanistic outcome that predicted clinical improvement in mice and may require longer therapy to observe clinical improvement in humans.

ShA9 was selected for use in bacteriotherapy based on its capacity to selectively kill and inhibit toxin production by S. aureus. These functions of ShA9 were shown to be independent of each other through experiments in mice using a mutant ShA9 strain lacking lantibiotic expression. Analysis of swabs and bacterial isolates from the skin of participants in the clinical trial also supported this conclusion. The multiple modes of activity of ShA9 are a particularly attractive characteristic of this form of therapy because evolutionary pressure to develop lantibiotic resistance is not present against the AIP. Although we have observed several strains of S. aureus that were resistant to killing by ShA9, we have not yet detected a S. aureus strain that is resistant to inhibition of quorum sensing by the ShA9 AIP. Furthermore, recent observations suggest that certain strains of S. epidermidis can also contribute to exacerbation of skin inflammation in AD and ShA9 also inhibits quorum sensing by S. epidermidis37. These observations suggest that ShA9 could potentially also act on patients who are S. aureus culture negative.

Most participants were colonized by S. aureus strains sensitive to direct killing by ShA9. AD patients have been reported with both monoclonal21 and variable S. aureus strains within each subject38,39. Thus, a targeted therapy in AD that seeks to specifically work against S. aureus, but not act broadly against CoNS, is a difficult challenge. Despite these challenges, participants with S. aureus strains sensitive to ShA9 showed improvement in local EASI and SCORAD score compared with vehicle. ShA9 or vehicle was applied only to participant forearms, but the improvement in the SCORAD score is an assessment of systemic AD severity and may reflect improved perception of general symptoms resulting from the local effect of ShA9. Importantly, these observed effects also persisted after the end of treatment. This extended therapeutic effect suggests persistence of the beneficial products of this strain, both lantibiotics and the AIP, on the skin.

The activity of lantibiotics can be highly selective for individual bacterial species and strains26–30. This selectivity is important to establish a normal microbial ecosystem because it enables other microbes to coexist within the same ecosystem. This principle was an important additional aspect considered in selection of ShA9 as bacteriotherapy for AD. The intent was to select an organism that could both selectively kill detrimental microbes such as S. aureus and enable expansion of a healthy bacterial community. An expansion of a diverse CoNS community may enhance both innate and adaptive immune systems in human skin, and exert anti-inflammatory action through a toll-like receptor–cross-talk mechanism40–44. Indeed, the host can benefit from active microbial competition, which enhances microbial diversity, rather than an environment that promotes the selective growth of specific microbes45. Ideally, targeted bacteriotherapy will enable the expansion of multiple other beneficial CoNS species that will act together with the applied bacterial strain. The 16S analysis from the current trial suggests that this may have occurred, and a similar phenomenon has been seen after fecal microbial transplants for Clostridium difficile infection46. Furthermore, as ShA9 lantibiotics synergize with host AMPs26, improved skin defense function may occur with increased expression of β-defensins and LL-37 that can be expected with decreased TH2 T-cell inflammation. This phenomenon was supported by observations in a recent study of a decrease in S. aureus after inhibition of IL-4Rα signaling47. Further investigation is needed to understand the interactions of these variables over a longer course of therapy.

We consider the results with ShA9 for bacteriotherapy of AD to be highly encouraging, but recognize that this trial was of short duration, with a small cohort and limited to only adult participants with moderate-to-severe AD who were selected based on positive S. aureus colonization. An alternative clinical trial design with a longer duration of treatment and optimized vehicle is needed to better assess the therapeutic potential of ShA9 in both culture-positive and culture-negative S. aureus patients.

In the current 1-week phase 1 trial, no evidence of emergence of new lantibiotic-resistant S. aureus was seen after ShA9 application. For future longer-term clinical trials, development of lantibiotic resistance in S. aureus strains must continue to be assessed. The expression of mprF also confers resistance to daptomycin by S. aureus48, and other mechanisms for resisting killing to naturally occurring antimicrobial proteins and peptides exist. However, no known resistance to inhibition of quorum sensing by AIPs has been identified and this mechanism of action would not place selective pressure for development of resistance. Thus, multifunctional bacteriotherapy has important theoretical advantages as a therapeutic approach over a single-agent drug.

Overall, our results support the conclusion that an optimal treatment approach for AD would be one that restores epidermal barrier defects while also suppressing causes of inflammation. The data from the current study show that this new therapeutic approach utilizing commensal microbes to protect the skin is safe over a 7-d period. The encouraging clinical and mechanistic results suggest that further investigation is warranted to evaluate efficacy and the long-term risks and benefits of this method for bacteriotherapy of patients with AD.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591–021-01256–2.

Methods

Bacteriotherapy in a mouse AD model.

All experiments involving live animals were done with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Guidelines of the University of California, San Diego (protocol no. S09074). To evaluate the therapeutic effect of topical application of ShA9, we employed a murine AD model using Flgft/ft Balb/c mice previously described11. Briefly, a sterile patch treated with OVA solution (100 μg per 100 μl) or phosphate-buffered saline was placed on tape-stripped dorsal skin of FLGft/ft Balb/c mice (age 6–8 weeks, mixed sex) for 8 d (the patch was replaced every 2 d). Mice were housed under a specific pathogen-free condition with a 12-h light:12-h dark cycle at 20–22 °C and 30–70% humidity. The treatment was randomly conducted in a unblinded manner. Experiments in a blinded manner were not possible because of a risk of cross-bacterial contamination between mice. Each mouse received three 8-d exposures in 2-week intervals. Then 24 h after the end of the third exposure, dorsal skin was tape-stripped with D-Squame adhesive disks (CuDerm), and disinfected with alcohol swabs twice. A 6-mm tryptic soya broth (TSB) agar disk containing 1 × 106 c.f.u. of S. aureus (catalog no. ATCC35556) or S. aureus isolated from lesional skin of AD patients was applied to the skin for quantitative bacterial application. An agar disk without bacteria was used as a negative control. The entire dorsal skin was then covered with wound-dressing film for 24 h. ShA9 or ShA9-Δlanti in 50% Cetaphil lotion and 50% glycerol (1 × 109 c.f.u. g−1, 50 mg) or equal volume of vehicle was topically applied to the dorsal skin twice a day for 3 or 7 d. Then 18 h after the last application, live bacteria were collected from the dorsal skin (4 cm2) by swab in the same manner as from human skin (described below). Punch biopsy was obtained from the center of the target site and total RNA was extracted.

Assessment of skin inflammation in mice.

To determine expression of mRNA for Il-4, Il-13, Cxcl2, Tslp, Il-17a, Il-22, mouse defensins and cathelicidin, total RNA was extracted using an RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN) and reverse-transcribed with iScript (Bio-Rad). Pre-developed Taqman assay probes (Applied Biosystems) were used to analyze the expression of these genes. The mRNA expression of each gene was evaluated by qPCR and normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) expression (Supplementary Table 3).

To measure TH2 and TH17 T-cell subsets in the skin, full-thickness dorsal skin (1 cm2) was minced and digested with dispase. Suspended cells were separated by a Percoll gradient, and cells including leukocytes in the intermediate layer were collected. Collected cells were washed with RPMI-1640, and incubated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin for 2 h, followed by addition of Brefeldin A for an additional 2 h. Cell suspensions (1 × 106 cells per 100 μl) were blocked by anti-mouse CD16/CD36 IgG (BioLegend, catalog no. 1011302, lot no. B288201; 0.5 mg ml−1), followed by staining with Fitable Viability Dye eFlour506 and anti-mouse CD4-IgG-APC/e780 (Invitrogen, catalog no. 47–0042-82, lot no. 2011192; 0.125 μg per 100 μl). After the surface staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized, then stained with anti-mouse IL-4 IgG–PerCP–Cy5.5 (BioLegend, catalog no. 504123, lot no. B278586; 0.25 μg per 100 μl) and anti-mouse IL-17A-Brilliant Violet650 (BioLegend, catalog no. 506929, lot no. B249696; 0.25 μg per 100 μl). CD4+IL-4+ or CD4+IL-17A+ cell subsets were analyzed by ZE5 Cell analyzer (Bio-Rad), using FlowJo software, v.10.

The severity of local inflammation on mouse back skin was quantitatively assessed by blinded observers as previously described33. Briefly, total disease represents the sum of individual grades for erythema, edema, erosion and scaling as 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate or 3 = severe. As edema was not observed in this mouse model, the disease score range is 0–9.

Skin barrier function was estimated by measuring TEWL using Tewameter TM300 (CK electronic). TEWL was determined from three replicated measurements from each mouse.

Generation of lantibiotic knockout mutant of ShA9.

Lantibiotic-α and lantibiotic-β are immediately adjacent to each other in the genome of ShA9 (ref. 26). To delete both lantibiotic genes by allelic replacement using the pKOR1 vector49, a 1-kb upstream sequence of lantibiotic-α and a 1-kb downstream sequence of lantibiotic-β were amplified using the following primers: attB1-lantiA-up-F/lantiA-up-R-sacII for the upstream fragment and sacII-lantiB-down-F/lantiB-down-R-attB2 for the downstream one (Supplementary Table 3). The PCR products were digested with SacII and ligated by T4 DNA ligase. The ligated 2-kb fragment was incorporated into the pKOR1 vector using BP Clonase II enzyme mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To facilitate transformation into ShA9, the resulting plasmid was amplified in DC10B E. coli strain, and then ShA9 was transformed with the plasmid by electroporation (2,500 V, 5 ms) using an Eporator (Eppendorf). Transformed ShA9 was screened on TSB agar containing 6% yeast extract and chloramphenicol (5 μg ml−1) at 30 °C. The allelic recombination procedure was performed by a temperature shift from 30 °C to 42 °C. The fidelity of gene deletion was determined by PCR using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 3) and radial diffusion assay for antimicrobial activity26.

In vitro quorum-sensing assay.

As expression of psmα is under the regulation of agr quorum sensing in S. aureus31, we evaluated anti-quorum-sensing activity of ShA9 AIP on psmα mRNA expression in S. aureus USA300Lac strain, which is resistant to the antimicrobial activity of ShA9. To measure anti-quorum-sensing activity of AIP from ShA9 WT or ShA9-Δlanti mutant, each strain was cultured in TSB overnight. Bacteria were removed by centrifugation followed by sterile filtration with a 0.22-μm membrane. The sterile conditioned medium (CM) was further filtrated with 3,000 Da cut-off membrane to remove lantibiotics. S. aureus USA300Lac strain (1 × 105 c.f.u. ml−1) was incubated with 0, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5 and 25% of CM at 30 °C for 18 h. Total RNA was extracted from bacterial cells with RNA Fungal/Bacterial kit (Zymo Research). Complementary DNA was synthesized with random hexamer primers; mRNA for psmα, mprF and gyrB was quantified by qPCR using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 3).

Clinical trial design.

For evaluation of the safety of bacteriotherapy using skin commensal bacterium on adult participants with AD, the primary endpoint was defined in collaboration with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) to measure incidence of serious and nonserious treatment-emergent AEs per participant during the time period of days 0–8. For evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy and mechanism, the secondary endpoints were defined to analyze clinical outcomes, bacterial survival, abundance of bacterial DNA and mRNA, and microbial community during treatment and follow-up time points up to 96 h. The detailed endpoints are described in the full protocol (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ProvidedDocs/48/NCT03151148/Prot_000.pdf.)

The strain selected for the study (ShA9) was originally isolated from the forearm skin of a healthy human donor26. Adult patients (n = 54) with moderate-to-severe AD who were S. aureus culture positive at screening were enrolled in the study. The proposed sample size was determined based on hypothetical observed means of serious or nonserious AEs per participant, using Poisson’s distribution. The sample size proposed allowed the study to determine the safety profile of this clinical trial, as well as estimate parameters of secondary analyses to power future efficacy studies.

At days 0 (before and 1 h after application), 4, 7 (4 h after last application), 8, 9 and 11, live bacteria, microbial DNA and RNA were collected with skin swabs from a 5-cm2 area of lesional and nonlesional skin on the ventral arm. Survival of S. aureus and CoNS was measured on Baird–Parker agar and mannitol salt agar with egg yolk, selectively using an easySpiral automatic plater and colony counter (Interscience Inc.). Microbial DNA was quantified by qPCR with species-specific primers (Supplementary Table 3). The cDNA was synthesized from RNA with random hexamer primers to quantify gene expression by reverse transcription-qPCR with gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 3). The composition of the microbial community was assessed by shotgun sequencing of the amplified V1–V9 region of the 16S rRNA gene.

All samples were blinded for analysis, and data were independently analyzed by Rho, Inc. Randomization was performed centrally at the Statistical and Clinical Coordinating Center (SACCC) using a stratified block randomization design. Authorized users at the clinical site accessed the RhoRAND application developed for the present study by the SACCC, to randomize eligible participants. The application generated each participant’s treatment assignment and emailed a notification to the site pharmacist. Randomization was stratified by four strata based on S. aureus abundance (low or high) and the enrolling clinical site. Blocks varied in sizes of either three or six within each stratum to mitigate risks of imbalance. S. aureus abundance was assessed by quadrant growth on a blood agar plate, with a score of 1 representing ‘low’ growth and scores of 2–4 representing ‘high’ growth.

An interim analysis was conducted after ten participants given active ShA9 and five participants given placebo completed their day 38 visit, administered 75% of their assigned doses and provided skin swabs with analyzable results at the study visits on days 0, 7 and 11. The interim analysis was conducted to provide critical information for the design of future studies regarding the potency of the intervention to decease S. aureus colony-forming units and detect the tendency of ShA9 to accumulate on the skin after repeated applications. No decisions regarding the conduct of the trail were made based on the results of the analysis. Enrollment was not impacted or paused while the interim analysis was performed. The number of experimental replications is provided in the figure legends.

Human subjects.

This trial was reviewed and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an investigational new drug application (IND no. 17286). This trial has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03151148). All experiments involving human subjects were carried out according to a protocol approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (protocol no. WIRB 20170196) and carried out at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) (local protocol no. 171060) and National Jewish Health (NJH). Informed consent of the current trial was approved by the WIRB on 17 July 2017, and the first patients were screened and enrolled at the end of September 2017. A written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Adult patients (aged 18–80 years), with an Investigator Global Assessment of at least moderate-to-severe severity of their ventral forearms50, were screened for enrollment at UCSD and NJH. The 54 participants were enrolled from 28 September 2017 to 7 June 2019 based on study inclusion and exclusion criteria, including positive screening for culturable S. aureus. Participants were randomized 2:1 to active treatment versus vehicle. Both participants and investigators were blinded to therapy. All participants avoided systemic immunosuppressives, oral steroids and phototherapy for 4 weeks, topical and oral antibiotics, topical steroids or antimicrobial baths for 1 week, before starting application of the active agent or vehicle, and for the duration of the trial. The collection of surface bacteria was performed from a pre-measured area (5 cm2) of lesional skin and nonlesional skin of the ventral arms.

Preparation of investigational product.

The investigational product (IP) used for this trial was manufactured under good manufacturing practice conditions at UCSD with procedures reviewed and approved by the NIAID.

A master cell bank of ShA9 was prepared and validated for purity. A single colony from a master cell bank was then cultured in animal-free TSB (Corning, catalog no. 61–411-RO) at 37 °C for 18 h with shaking at 200 r.p.m. Bacterial cells were washed with saline three times and re-suspended in saline. Bacterial density was estimated by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). ShA9 IP was formulated at 1 × 109 c.f.u. g−1 in 50% Cetaphil lotion (Galderma) and 50% of a cosmetic-grade vegetable glycerin (SR Natural). The control vehicle lotion was formulated in the same manner, with equal amounts of saline in place of the volume of bacteria. IP, 2 g, was packed into sterile heat-sealing pouches as a single-use aliquot. The aliquots were labeled with blinded information and stored at −80 °C until usage. Quality and sterility of IP were evaluated by counting of colony-forming units, radial diffusion assay, PCR using specific primers for ShA9 lantibiotic-a and USP61/62 testing every 6 months after manufacture according to US Food and Drug Administration guidelines. The present study was periodically reviewed for participant safety by an NIAID Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Bacteriotherapy in humans.

At screening, Investigator Global Assessment of the ventral arms and AD assessments (local EASI of the ventral arms51 and SCORAD index52) were performed, and bacterial swabs were obtained from a lesional site on the ventral forearm for S. aureus screening. AD severity of the bilateral ventral arms was assessed by calculating the local EASI based on the sum of the erythema, induration, lichenification and excoriation (rated on a scale of 0–3) of the bilateral ventral upper arms, multiplied by the extent of the regional involvement of the bilateral ventral arms (scale of 0–6) and the body surface area of the bilateral ventral arms (0.1)51. Local VAS for pruritus was reported by participants in response to questions about their average and worst itch intensities experienced in the past 24 h (ref. 53). The SCORAD index was calculated for the total body using the standard SCORAD index formula of A/((5 + 7B)/(2 + C)) (ref. 52), where A is defined as the extent of involvement of the total body (0–100), B as the sum of erythema, edema/papulation, oozing/crusting, excoriation, lichenification and dryness (rated on a scale of 0–3, maximum score 18) and C as the subjective symptoms of pruritus and sleep loss (0–20). The maximum SCORAD score is 103.

Only participants with moderate-to-severe AD by Investigator Global Assessment of the ventral arms, who were S. aureus culture positive, were included in the clinical trial.

At the day 0 visit, AD assessments were obtained as described above and baseline swabs for live bacteria, microbial DNA and RNA were also obtained pre-treatment from 5-cm2 areas of lesional skin and nonlesional skin. After obtaining baseline swabs, a single aliquot of ShA9 lotion or vehicle (2 g) was applied to the entire ventral surface of each arm to deliver 1 × 106 c.f.u. cm−2. Then 1 h post-application, repeat swabs were obtained from the same area. Participants were then provided with a 4-d supply (22 single-use, 2-g aliquot packets) to enable twice-daily application until day 4, then 22 freshly thawed aliquots were provided for additional treatment between days 4 and 7. Participants were instructed to store packets at 4 °C. At the day 4 and day 7 visits, swabs and AD assessments were obtained, within 4 h of the last morning application. Off-treatment, swabs and AD assessments were also obtained on days 8 (24-h f/u), 9 (48-h f/u) and 11 (96-h f/u) after the last dose of ShA9 had been applied. To reduce participant burden, the 48-h f/u time point was removed from the protocol in the middle of the trial and officially changed, with permission from Rho Inc. and the NIAID. This change affected only the last five participants of the study.

Sensitivity of patient’s S. aureus to ShA9.

To measure the capacity of S. aureus strains from each participant to be inhibited by ShA9, S. aureus was isolated from a baseline swab sample taken from each participant and plated on a Baird–Parker agar plate. ShA9 was cultured in TSB overnight, and bacteria were removed by centrifugation, followed by sterile filtration by a 96-well filter plate with a 0.22-μm poly(vinylidene) membrane. Antimicrobial activity was precipitated by adding ammonium sulfate at 70% saturation and dissolved in 1:10 volume of RPMI-1640 medium. A single colony of S. aureus was isolated from each participant, grown in TSB overnight and then diluted to 1 × 105 c.f.u. ml−1 in RPMI-1640. S. aureus from each participant was then incubated at 30 °C for 24 h with the precipitated antimicrobial fraction from ShA9. Growth of S. aureus was evaluated by measuring OD600 and the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ShA9-conditioned medium to completely suppress growth of S. hominis was determined, as calculated by the percentage of original conditioned medium from ShA9. S. aureus that was sensitive to ShA9 was defined as having an MIC < 100% and resistant strains of S. aureus as having an MIC > 200%.

Quantification of live staphylococci.

Collection of surface bacteria was done from a pre-measured area (5 cm2) of lesional skin, on the antecubital fossa, and a pre-measured area (5 cm2) of nonlesional skin on the upper arm. The entire target area of the skin was rubbed 50 times with consistent firm pressure with sterile nylon swabs (Puritan) pre-moistened with TSB. Samples were then suspended in 1.0 ml of TSB containing 15% (v:v) glycerol. The samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis. The colony-forming units of S. aureus and total staphylococci were counted on Baird–Parker agar and mannitol salt agar with egg yolk for selective growth, respectively54,55, using easySpiral automatic plater and colony counter (Interscience Inc.). CoNS colony-forming units were determined by subtracting S. aureus colony-forming units from total colony-forming units of the staphylococci.

Quantification of bacterial mRNA.

Bacterial RNA was collected using a similar method to the collection of live bacteria, but the skin was rubbed with a swab pre-moistened with Tris–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.05% Tween-20 (w:v). The swab tip was stored in 100 μl of 10% TRIzol solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 90% ethanol to avoid RNA degradation at −80 °C until analysis. DNA contamination in the sample was digested with DNase I and microbial RNA was purified from the swab with a ZymoBIOMICS RNA preparation kit (Zymo Research Inc.). The cDNA was synthesized with random hexamer primers using a Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gene expression of ShA9 lantibiotic-α, ShA9-AIP, S. aureus psmα or mprF was quantified by qPCR using strain-specific primers or primer probes (Supplementary Table 3). The absolute copy number of each mRNA was accomplished by including a standard curve from an authentic amount of pGEM-T plasmid which contains target amplicon.

Quantification of bacterial DNA.

Bacterial DNA was collected by a similar method to the collection of microbial RNA, and swab tips were stored at −80 °C until analysis. Microbial DNA was purified with PureLink Microbiome DNA purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and eluted in 50 μl of elution buffer. The abundance of bacterial DNA in the elution was determined by quantitative qPCR with species- or strain-specific primers/probe (Supplementary Table 3). To determine the relative colony-forming units of S. hominis DNA, a standard curve was generated with genomic DNA extracted from a known colony-forming unit of S. hominis (ATCC27844). The absolute copy number of ShA9 AIP or lantibiotic-α was determined, including a standard curve from an authentic amount of pGEM-T plasmid, which contains target amplicon.

Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequence and microbiome analysis.

Loop Genomics’ synthetic long-read, next-generation sequencing approach enabled full-length 16S sequencing with an ultra-low error rate. The ultra-high fidelity long reads enable high-resolution phylogenetic classification at the species level and an unbiased quantification of complex microbial communities. Extracted genomic DNA samples were generated into Illumina sequencing libraries of 16S rRNA gene targets with LoopSeq 16S Long Read kits from Loop Genomics (protocols available at loopgenomics.com). The process involved attaching two DNA tags: one unique molecular identifier (UMI) to each unique ‘parent’ molecule and one sample-specific tag (that is, loop sample index) equally to all molecules in the same sample. Using specialized processing enzymes, each UMI was distributed to a random position within each parent molecule, but not to adjacent molecules. After this, samples were multiplexed into a single reaction tube. The resulting samples were fragmented into smaller units at the position of UMI insertion, creating a library of UMI-tagged fragments compatible with an Illumina sequencing platform run in 150-bp paired-end mode. For each LoopSeq kit, which processed up to 24 samples simultaneously and captured ~12,000 molecules per sample (~300,000 molecules from a complete kit run), 100 × 106 to 150 × 106 paired-end reads (50 × 106 to 75 × 106 clusters passing the filter) were dedicated for each sequencing run, yielding ~20 Gb of data. Loop Genomics maintains a cloud-based platform for processing raw short reads prepared with a LoopSeq kit into assembled synthetic long contigs. Within this pipeline, sequence reads were trimmed to remove adapter sequences before they were de-multiplexed, based on their loop sample index, which groups reads by the sample from which they originated. Next, sample-specific reads were binned by UMI, such that reads with the same UMI were processed collectively through SPADES, which reassembles reads back into a synthetic long contig that represents the sequence of the original molecule. A collection of short reads that shared the same UMI was derived from the same parent molecule, with each read covering a different sequence region of the parent. With enough short reads to cover the full length of a 16S molecule, it was possible to reassemble the original long sequence by linking reads. Short reads with sequences that partially overlap were linked through shared sequences and then arranged in the correct order to build the original 16S molecule sequence. Assembly attempts with fewer reads resulted in shorter sequences, with lower mapping accuracy or no assembled sequences. Each collection of short reads that shared the same UMI resulted in either zero or one assembled long read.

Statistical analysis.

PROC GLIMMIX SAS Software 9.4 (SAS/STAT 14.3), GraphPad Prism v.8.4.2 (GraphPad) and Excel v.16.37 (Microsoft) were used for biostatistical analysis.

Variance of the distribution of the data from mouse experiments was examined first. When the data had a normal distribution, an unpaired, parametric Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. When the data had an abnormal distribution, a Mann–Whitney U-test was used or a parametric Student’s t-test was conducted after log(transformation).

The minimal effect size for the safety outcomes by risk difference or risk ratios was assessed before the trial for 36 ShA9 and 18 vehicle participants. Assuming a percentage range of AEs between 50% and 95% in the vehicle group, there was 80% power to detect, at least, a significant minimal risk difference between 25% and 35% among groups. Similarly, with a vehicle per-participant daily event rate of AEs between 0.25 and 0.50, the significant minimal risk ratio is at least between 0.50 and 0.65.

The per-participant count of serious and nonserious AEs was analyzed using a negative-binomial model to account for overdispersion, with a log(link) function, and including the natural log of the number of days active in the study during days 0–8 with adjustments for site and screening high (2–4) or low (1) S. aureus quadrant growth on blood agar plates.

For endpoints of bacterial abundance (CoNS, S. hominis A9, S. aureus, combined S. hominis, combined staphylococci and combined bacteria), the log10(transformed abundance) values were analyzed using a random-effects linear model with a log10(transformed numeric response) variable. The model was adjusted for the corresponding log10(transformed abundance) at day 0 before dosing. For models comparing lesional with nonlesional abundance, a random effect of participant ID was included in the model to account for correlation between corresponding measures within the same subject. Time in days was included as a repeated effect in the model.

To compare differences in baseline characteristics and demographics between the two groups, χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables, and Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon’s tests were used for normally distributed and non-normally distributed, continuous variables, respectively. The normality of baseline characteristics and demographics was determined by assessing the skewedness of variables.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data were independently validated by Rho Federal Systems Division, Inc. in a blinded manner. The detailed data analysis plan is available in DAIT/Rho Statistical analysis plan v.2.0, dated 15 May 2019, uploaded to Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ProvidedDocs/48/NCT03151148/Prot_000.pdf). The 16S rRNA gene sequence data for the present study have been published in open-source web application server, MG-RAST (www.mg-rast.org) with project ID mgp92321. Any materials that can be shared will be released via a material transfer agreement. Source data are provided with this paper.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |.

Low levels of bacteria are detected after topical application of bacteria on mice with inflamed skin. Colony forming units (CFU) of S. aureus and CoNS were measured from the spleen of OVA-sensitized FLGft/ft Balb/c mice that were colonized by S. aureus for 4 days and treated by ShA9 for 3 days. Spleens (50–100 mg) were surgically excised and homogenized in 1 mL PBS. Live S. aureus and CoNS CFU were counted on mannitol salt agar with egg yolk and CFU counts adjusted based on wet weight of the excised spleens. Data represent mean ± SEM of biological replicates in individual mouse (n = 8). No statistical difference was detected by two-tailed unpaired parametric t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |.

Gating strategy for flow cytometry to identify CD4 +, IL4 + or CD4 +, IL17A + cells associated with experiments in Fig. 2g–i.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |.

a-b, Flow diagram of participants (a) and illustration of measurements conducted for the clinical trial (b). § One individual withdrew due to inability to keep the time commitments of the study and was excluded from data analysis according to our study protocol. † This individual reported <75% of treatment being applied and was excluded from data analysis according to our study protocol. ‡ This individual was lost to follow up due to personal reasons but completed the study. He/she was included to data analysis according to our study protocol.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Change in abundance of S. aureus mprF mRNA on the lesional skin of subjects treated by ShA9.

Each dot represent data from individual subject. Data are shown as mean±95% confidence interval (n = 32 independent subjects). Data at each time point was compared by two-tailed paired parametric t-test and no change was detected.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |.

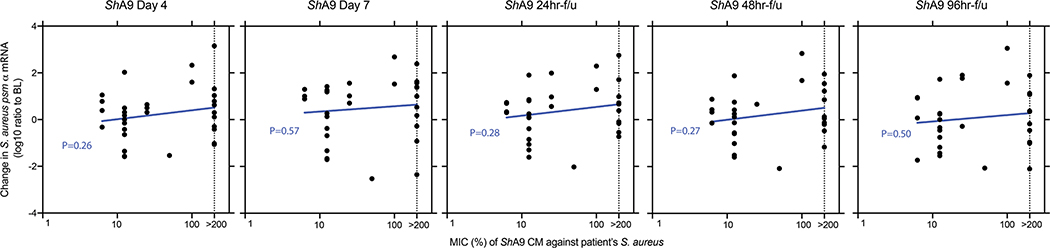

a, Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ShA9 supernatant to inhibit growth of S. aureus isolated from each subject is correlated with change in local EASI at the indicated time points after treatment with ShA9. S. aureus resistant to ShA9 was defined as its MIC > 100% of conditioned media. Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by two-tailed t distribution (n = 32 independent subjects). Dotted line represents detection limit of the assay. b, Correlation between relative change in live S. aureus abundance and change in local EASI scores from baseline at indicated time points for subjects treated with ShA9 (top row, blue) or vehicle (bottom row, red). Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by two-tailed t distribution (ShA9: n = 35; Vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects).

Extended Data Fig. 6 |.

a-c, Abundance of DNA for ShA9 lantibiotic-a (a), S. hominis-specific gap gene (b) and universal 16 S rRNA (c) on the lesional and nonlesional skin of patients treated by ShA9 or vehicle at indicated time points. Data represent Mean ± 95% confidence interval (ShA9: n = 35; Vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects) (a-c). A linear mixed-model approach was used to take into account the repeated aspect of the trial (a-c).

Extended Data Fig. 7 |.

a, Abundance of ShA9 lantibiotic-α mRNA recovered by skin swabs from lesional skin at indicated time points for subjects treated with ShA9 or vehicle. Data represent Mean ± 95% confidence interval (ShA9: n = 35; Vehicle: n = 17 independent subjects). A linear mixed-model approach was used to take into account the repeated aspect of the trial (a). b-c, Correlation between abundance of ShA9 lantibiotic-α mRNA (b) or ShA9 AIP mRNA (c) and S. hominis DNA on the lesional skin of subjects with ShA9 at indicated time points. Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by t distribution. Dotted line represents detection limit of the assay. Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by two-tailed t distribution (n = 35 independent subjects) (b,c).

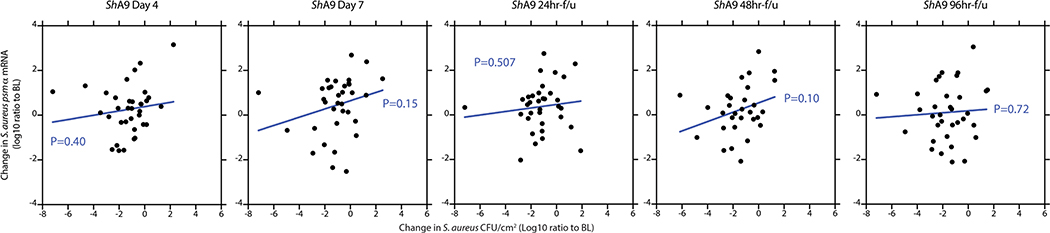

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. AIP activity from ShA9 against S. aureus psmα expression is independent from antimicrobial activity of ShA9.

MIC of ShA9 conditioned media (CM) against each patient’s S. aureus was correlated with relative change in S. aureus psmα expression from base line (BL) at indicated time point. CM was precipitated from ShA9 culture supernatant by 70% ammonium sulfate and % calculated from the original volume of medium. Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by t distribution. Dotted line represents detection limit of the assay. Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by two-tailed t distribution (n = 35 independent subjects).

Extended Data Fig. 9 |.

Change in S. aureus psmα expression after ShA9 treatment does not correlate with a decrease in S. aureus survival on AD lesional skin. Statistical analysis for correlation was carried out by two-tailed t distribution (n = 35 independent subjects).

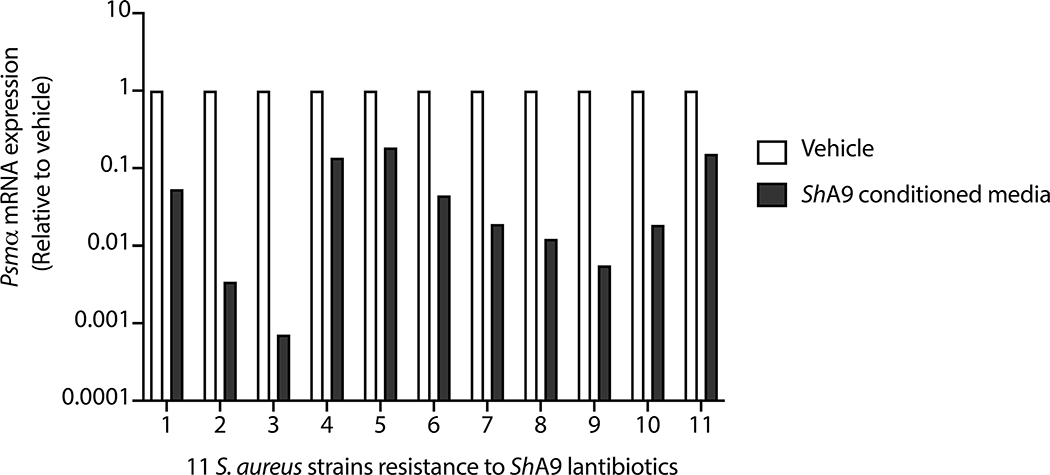

Extended Data Fig. 10 |. AIP activity of ShA9 on S. aureus isolates that resistant to ShA9 lantibiotics.

All 11 isolates of S. aureus identified by analyses in Fig. 3d,f,g were cultured in TSB with ShA9 conditioned media (25%) or TSB (Vehicle) at 30 °C for 18 hrs. Abundance in mRNA for Psmα was measured as described in Fig. 2j. Data represent mean of 2 technical replicates in independent bacterial culture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by the Atopic Dermatitis Research Network (ADRN) (grant nos. U19AI117673 and 1UM1AI151958 to R.L.G. and D.Y.M.L., and UM2AI117870 to Rho Federal Systems Division), and National Institutes of Health grants (nos. R01AR076082, R01AR064781 and R01AI116576 to R.L.G. and T.N., R37AI052453 and R01AI153185 to R.L.G.) and NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA grant no. UL1 TR002535 to D.Y.M.L.

Footnotes

Competing interests

T.N. and R.L.G. are co-inventors of UCSD technology related to the bacterial antimicrobial peptides discussed herein. R.L.G. is co-founder and has equity interest in MatriSys Bioscience and Sente Inc. A.K.R.S.’s co-authorship of this publication does not necessarily constitute endorsement by the NIAID, the NIH or any other agency of the US government. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591–021-01256–2.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591–021-01256–2.

Peer review information Nature Medicine thanks Alice Prince, Katrina Abuabara and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Alison Farrell was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Kapoor R et al. The prevalence of atopic triad in children with physician-confirmed atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 58, 68–73 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bieber T Atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med 358, 1483–1494 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nutten S Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann. Nutr. Metab 66, 8–16 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed B & Blaiss MS The burden of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Proc 39, 406–410 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bin L & Leung DY Genetic and epigenetic studies of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol 12, 52 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K & Irvine AD Atopic dermatitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim 4, 1 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langan SM, Irvine AD & Weidinger S Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 396, 345–360 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakatsuji T & Gallo RL The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol 122, 263–269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leyden JJ, Marples RR & Kligman AM Staphylococcus aureus in the lesions of atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol 90, 525–530 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong HH et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 22, 850–859 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakatsuji T et al. Staphylococcus aureus exploits epidermal barrier defects in atopic dermatitis to trigger cytokine expression. J. Invest. Dermatol 136, 2192–2200 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung DY Infection in atopic dermatitis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr 15, 399–404 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekeredjian-Ding I et al. Staphylococcus aureus protein A triggers T cell-independent B cell proliferation by sensitizing B cells for TLR2 ligands. J. Immunol 178, 2803–2812 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vu AT et al. Staphylococcus aureus membrane and diacylated lipopeptide induce thymic stromal lymphopoietin in keratinocytes through the Toll-like receptor 2-Toll-like receptor 6 pathway. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 126, 985–993 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura Y et al. Staphylococcus delta-toxin induces allergic skin disease by activating mast cells. Nature 503, 397–401 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell MD et al. Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis skin subverts the innate immune response to vaccinia virus. Immunity 24, 341–348 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]