Abstract

Recent advances in peroxidase‐mediated biotin tyramide (BT) signal amplification technology have resulted in high‐resolution and subcellular compartment‐specific mapping of protein and RNA localization. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in the presence of H2O2 is known to activate phenolic compounds for phenoxy radical reaction with nucleic acids, where biotinylation by BT is a practical example. BT reactivity with RNA and DNA is not understood in detail. We report that BT phenoxy radicals react in a sequence‐independent manner with guanosine bases in RNA. In contrast, DNA reactivity with BT cannot be detected by our methods under the same conditions. Remarkably, we show that fluorescein conjugates DNA rapidly and selectively reacts with BT phenoxy radicals, allowing convenient and practical biotinylation of DNA on fluorescein with retention of fluorescence.

Keywords: conjugation, nucleic acids, peroxides, radicals, reaction mechanisms

Enzyme‐catalyzed phenoxy radical biotinylation, an increasingly important tool in biotechnology and molecular biology applications, is here shown to label guanosine bases in RNA, but not in DNA, under defined conditions. Remarkably, common fluorescein conjugates of synthetic DNA oligonucleotides are found to undergo facile biotinylation on fluorescein with retention of fluorescence. This convenient observation points to a variety of practical applications of peroxidase‐catalyzed chemistry for analysis of DNA conjugates in vitro and in cells.

It has been shown that aryl radicals react at the C8 position of guanine and deoxyguanosine under certain conditions. [1] Such reactions are of interest as examples of mutagenic DNA damage relevant to carcinogenesis. Aryl radical reactivity of RNA has not been studied in detail. The advent and rapid improvement of proximity‐based labeling technologies such as biotin tyramide (BT) signal amplification and RNA localization mapping by the engineered ascorbate peroxidase APEX2 have highlighted the practical importance of RNA reactivity with phenoxy radicals. [2] In another example, APEX2 polymerizes diaminobenzene in the presence of H2O2 and deposits it locally, providing focal osmium tetroxide binding for electron microscopy. [3] However, the sequence specificity and relative reactivity of RNA and DNA with BT radicals have not been explored. We therefore studied BT phenoxy radical labelling of nucleic acids in vitro catalysed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in order to characterize these practical reactions in more detail.

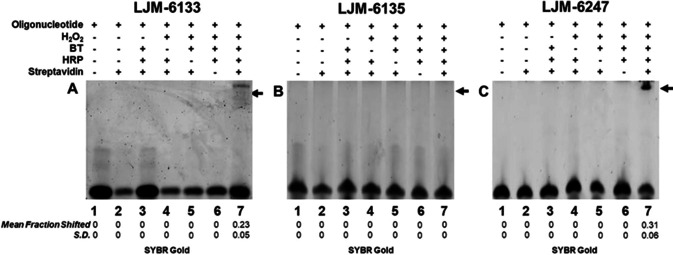

We first aimed to confirm a previous report that RNA biotinylation by BT phenoxy radicals occurs at G3 motifs. [2f] LJM‐6133 is an oligoribonucleotide 27‐mer containing three separate G3 motifs distributed within a mixed sequence (Table 1). We devised a streptavidin‐dependent electrophoretic mobility shift assay for detection of biotinylation in vitro. A gel shift of RNA LJM‐6133 was observed only when H2O2, BT, and HRP were incubated with the oligonucleotide for 90 min at 45 °C, followed by proteinase K digestion (Figure 1A, lane 7; Figures S1–S3 in the Supporting Information). HRP contains heme, which is known to biotinylate certain G‐quadruplex nucleic acids in the presence of H2O2 and BT. [4] In order to demonstrate that observed biotinylation was HRP‐dependent and would not occur with free heme, HRP was replaced by heme in an otherwise identical biotinylation reaction. Free heme was not capable of activating BT and biotinylating a target, demonstrating that 1) observed biotinylation is HRP‐dependent and 2) the targets likely do not form stable G‐quadruplexes that bind heme (Figure S4). Mfold predictions [5] did not identify significant secondary structures for these oligonucleotides (Figure S5).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides studied in this work.

|

Oligonucleotide |

Sequence (5’‐3’) |

|---|---|

|

LJM‐6131 |

AGGGCTAAGGTCTGACTGGGAATGGGA |

|

LJM‐6132 |

FAM‐AGGGCTAAGGTCTGACTGGGAATGGGA |

|

LJM‐6133 |

AGGGCUAAGGUCUGACUGGGAAUGGGA |

|

LJM‐6135 |

AGCGCUAAGGUCUGACUGAGAAUGUGA |

|

LJM‐6247 |

AGAGCUGAGGUCUGACGGUGAGUGAGA |

|

LJM‐6223 |

TAMRA‐AGGGCTAAGGTCTGACTGGGAATGGGA |

|

LJM‐6346 |

AGUGAUGAGGAACGUUGGAGCGCGUGC |

|

LJM‐6347 |

UGCGUCGUGGACCGUCGGAGCGUGCGU |

|

LJM‐6348 |

CGCGUAGUGGUUAGAAGGCGAGCGUGA |

|

LJM‐6349 |

TCCCATTCCCAGTCAGACCTTAGCCCT |

Figure 1.

Oligoribonucleotide radical biotinylation is catalyzed by HRP in the presence of H2O2 and biotin tyramide. Biotinylation is detected by a streptavidin‐dependent gel shift under denaturing conditions, followed by staining with SYBR Gold. A) Biotinylation of LJM‐6133 containing G3 motifs. B) Biotinylation of LJM‐6135 lacking G3 motifs. C) Biotinylation of LJM‐6247 containing the same number of G residues as LJM‐6133, without G3 motifs. Statistics were calculated from independent experiments performed in triplicate; S.D.: standard deviation.

G3 motifs were then disrupted by substitution of a random nucleotide in the second position of each G3 motif in RNA LJM‐6135. This RNA was not detectably biotinylated under identical conditions (Figure 1B, lane 7). To determine whether it is the number of guanosine residues, or their distribution, that confers BT reactivity, RNA LJM‐6247 was synthesized containing the same number of guanosine residues as LJM‐6133 but lacking G3 motifs (Table 1). Strikingly, RNA LJM‐6247 was biotinylated (Figure 1C, lane 7; Figure S6). These results demonstrate that RNA biotinylation does not depend solely on the presence of G3 motifs, but instead on the total guanosine content of an RNA. We further demonstrated G‐specificity of RNA biotinylation by adding NTP competitor to biotinylation reactions, finding that only the addition of excess GTP reduced biotinylation of a target oligonucleotide (Figure S7). In order to confirm that biotinylation of LJM‐6247 was not influenced by the position of G relative to other RNA residues, we generated three oligoribonucleotides with G residues in identical positions but with all other bases randomly mutated. These randomly substituted targets were all similarly biotinylated (Figure S8).

Finally, we confirmed by mass spectrometric analysis that a BT‐guanosine adduct is formed at the C8 position of guanosine by BT phenoxy radical addition to LJM‐6247 (Figure S9). This structure is consistent with the literature for guanine and deoxyguanosine C8 reactivity with other phenoxy radical‐containing compounds, [1] but to our knowledge is the first direct evidence of such biotinylation of guanosine. Importantly, BT adducts with other bases were not identified (Figure S10). Given the context‐independent reactivity of guanosine in LJM‐6247, it is therefore likely that previous results identifying consecutive guanosine residues as preferred sequences for RNA phenoxy radical reactivity simply reflect the high number of guanosines at these sites.

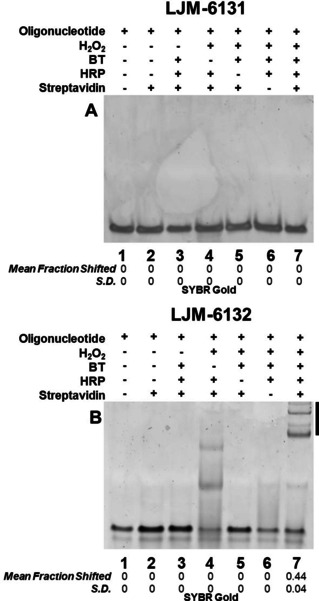

Having established that RNA biotinylation occurs on guanosine independent of sequence context, we next investigated radical biotinylation of DNA oligonucleotides under identical conditions. Oligodeoxyribonucleotide LJM‐6131 has the same sequence as RNA LJM‐6133. Remarkably, LJM‐6131 was not detectably biotinylated by HRP under identical conditions (Figures 2A, S11, and S12). Previous reports suggest that deoxyguanosine can react with phenoxy radicals under some conditions, but this reaction is much more efficient with catalysts other than peroxidases. For example, FeIII‐ or CuII‐catalyzed reactions between deoxyguanosine and ochratoxin A, a mycotoxin with a single phenoxy group, occur up to 5‐fold faster than with HRP/H2O2 at 24 h. [1b] Several reports describe heme‐dependent self‐biotinylation of G‐quadruplex DNAs by BT. [4]

Figure 2.

Oligodeoxyribonucleotide 5’‐FAM modification is necessary and sufficient for efficient radical biotinylation catalyzed by HRP in the presence of H2O2 and biotin tyramide. Biotinylation of the indicated DNA oligonucleotides is detected by a streptavidin‐dependent gel mobility shift under native conditions. Statistics are calculated from independent experiments performed in triplicate; S.D. is standard deviation.

Similar reactions show that heme is capable of oxidizing a library of phenolic substrates seven to 68 times more efficiently than HRP. [6] There is a report of double‐stranded DNA biotinylation by HRP under conditions different from those presented here, complicating comparison of results. [7] In order to assess double‐stranded DNA biotinylation under the present conditions, oligodeoxyribonucleotide LJM‐6349 was hybridized with LJM‐6133 to form a duplex. No biotinylation of the duplex was observed (Figure S13). We therefore conclude that DNA is intrinsically much less reactive with phenoxy radicals than RNA, limiting practical HRP‐catalyzed BT conjugation. To eliminate the possibility that DNA biotinylation was undetectable because biotinylated DNA, but not RNA, suffers rapid depurination, we exposed reacted DNA oligonucleotides to hot piperidine treatment to cleave apurinic sites. No evidence of detectable DNA depurination was observed under these conditions (Figure S14).

Serendipitously, we also studied DNA LJM‐6132, a version of LJM‐6131 differing only by 5’ conjugation of fluorescein (FAM). Remarkably, whereas LJM‐6131 resisted biotinylation, LJM‐6132 was efficiently biotinylated in vitro by HRP in the presence of BT and H2O2 (Figure 2B, lane 7; Figure S9). This surprising result was confirmed in both native and denaturing polyacrylamide gels under conditions where biotin‐streptavidin complexes remain stable (Figure S11). Thus, fluorescein conjugation is necessary and sufficient for DNA phenoxy radical biotinylation. The multiple streptavidin‐dependent bands observed in lane 7 of Figure 2B presumably result from different numbers of biotinylated oligonucleotides binding to streptavidin tetramers.

Inspection of gel images also revealed unexpected shifted products in the absence of BT (Figure 2B, lane 4). These products are of lower molecular weights than those observed for streptavidin complexes (Figure 2B, lane 7). We hypothesized that these biotinylation‐independent products resulted from phenoxy radical reactions between LJM‐6132 molecules and between LJM‐6132 and tyrosine residues of HRP. We therefore quenched reactions with proteinase K digestion for 1 h at 56 °C, to remove proteins. Indeed, most biotinylation‐independent products were eliminated by proteinase K digestion, confirming that they reflect direct reaction of LJM‐6132 with HRP (Figure S2). Interestingly, several reaction products formed in the absence of BT resisted proteinase K digestion for 24 h (Figure S3). We hypothesize that these proteinase K‐resistant species are DNA‐DNA crosslinked products. The presence of both DNA‐protein and DNA‐DNA products in radical reactions lacking BT suggests that fluorescein itself is activated by H2O2 similarly to BT, at phenolic functional groups present in both compounds. Given that DNA–DNA and DNA‐HRP products are suppressed in the presence of excess BT, we conclude that radical activation of BT by HRP is efficient.

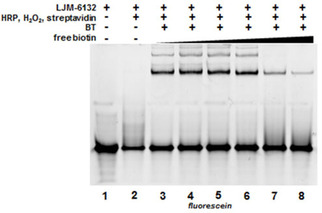

To confirm that electrophoretic mobility shifts detected for BT‐dependent products indeed reflect noncovalent biotin–streptavidin complexes, we demonstrated that such products are sensitive to competition by addition of free biotin. Streptavidin was incubated for 30 min with 0–200 μM free biotin before the addition of LJM‐6132 reaction products. Competition was observed as expected (Figure 3, lanes 3–8). Maximum competition was observed at free biotin concentrations near equivalence with total biotin binding sites on streptavidin (Figure 3, lanes 7 and 8). This result confirms that fluorescein‐modified LJM‐6132 undergoes phenoxy radical biotinylation in a manner dependent on the simultaneous presence of FAM, HRP, BT, and H2O2. It is striking that FAM reaction products remain fluorescent (Figure 3, lane 3) while proteinase‐K resistant FAM–FAM crosslinked products do not (Figure S3A and B).

Figure 3.

Biotinylation confirmed by free biotin competition for streptavidin binding to LJM‐6132. Biotin excess of 0–200 μM (lanes 3–8) in a 30‐min pre‐incubation inhibits LJM‐6132 binding by streptavidin under native gel conditions.

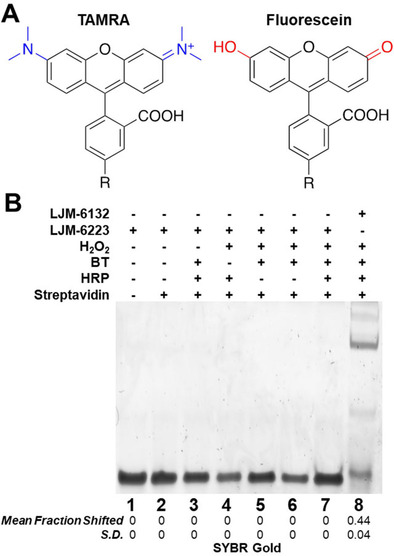

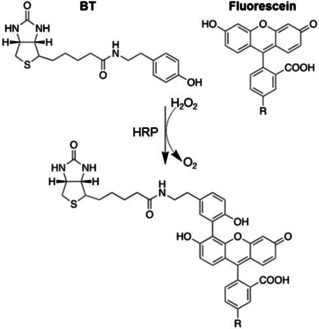

These results show that the resistance of unmodified DNA oligonucleotides to radical biotinylation can be practically overcome by FAM conjugation, a particularly convenient and accessible modification. We hypothesized that the fluorescein‐BT reaction involves the phenolic functional groups of fluorescein, analogous to BT. To test this, we exploited the structural similarity of rhodamine (TAMRA) and fluorescein, where TAMRA lacks phenolic functional groups (Figure 4A). DNA oligonucleotide conjugates to FAM (LJM‐6132) and TAMRA (LJM‐6223; Table 1) were subjected to radical biotinylation reactions. Whereas LJM‐6132 was detectably biotinylated, TAMRA‐conjugated LJM‐6223 was not (Figure 4B). Lower molecular weight BT‐independent DNA‐HRP products are also not observed with TAMRA‐conjugated DNA. We deduce that phenoxy radical biotinylation of FAM‐conjugated DNA involves the phenolic functional group of FAM. While results of preliminary mass spectrometric analyses to confirm the FAM biotinylation product were indeterminate, we propose the reaction mechanism shown in Scheme 1. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of peroxide‐mediated activation of BT allowing biotinylation of fluorescein by phenoxy radical chemistry.

Figure 4.

Radical biotinylation of FAM but not TAMRA. A) Structures of FAM and TAMRA highlighting phenolic group of FAM (red) vs. amino groups of TAMRA (blue). R: oligonucleotide. B) Absence of detectable radical biotinylation under native gel conditions of 5’‐TAMRA‐modified LJM‐6223 relative to 5’‐FAM‐modified LJM‐6132. Statistics are calculated from independent experiments performed in triplicate; S.D.: standard deviation.

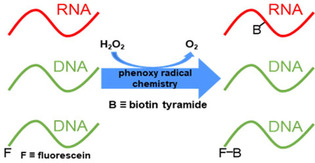

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism of HRP‐catalyzed phenoxy radical biotinylation of FAM by biotin tyramide in the presence of H2O2. R: oligonucleotide.

In summary, we present evidence that RNA is significantly more reactive to phenoxy radical biotinylation than DNA, and that RNA biotinylation occurs at guanosine residues. Radical biotinylation is at the C8 position of guanosine independent of sequence context, and is therefore more likely for G‐rich RNA sequences. In contrast, DNA biotinylation of the same sequence under identical conditions is so low as to be undetectable by our streptavidin binding assay. Importantly, phenoxy radical biotinylation of DNA oligonucleotides is conveniently facilitated by fluorescein conjugation. Fluorescein is directly activated by HRP and H2O2, allowing radical biotinylation by BT. This insight might be helpful for future chemical biology applications as it enables proximity biotinylation of FAM‐conjugated DNA by peroxides in cases where biotinylation of unmodified DNA is undetectable. Further study will be required to understand the relative susceptibility of DNA versus RNA to phenoxy radical chemistry.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant GM128579 (L.J.M.), the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, and an NSF graduate fellowship (B.W.). B.G. was supported by NIH Post‐baccalaureate Research Education Program grant GM75148. SB and PD are supported by NIH grants AG063341 and ES031529 to PCD.

B. Wilbanks, B. Garcia, S. Byrne, P. Dedon, L. J. Maher, ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 1400.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Manderville R. A., Can. J. Chem. 2005, 8, 1261–1267; [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Dai J., Wright M. W., Manderville R. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 3716–3717; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Sproviero M., Verwey A., Whitham A., Manderville R. A., Sharma P., Wetmore S., Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015, 28, 1647–1658; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Sproviero M., Verwey A. M., Rankin K. M., Witham A. A., Soldatov D. V., Manderville R. A., Fekry M. I., Sturla S. J., Shama P., Wetmore S., Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 13405–13421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Martell J. D., Deerinck T. J., Sancak Y., Poulos T. L., Mootha V. K., Sosinsky G. E., Ellisman M. H., Ting A. Y., Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 1143–1148; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Lam S. S., Martell J. D., Kamer K. J., Deerinck T. J., Ellisman M. H., Mootha V. K., Ting A. Y., Nat. Methods 2014, 12, 51–54; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Rhee H. W., Zou P., Udeshi N. D., Martell J. D., Mootha V. K, Carr S. A., Ting A. Y., Science. 2013, 339, 1328–1331; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Han S., Udeshi N. D., Deerinck T. J, Svinkina T., Ellisman M. H., Carr S., Ting A. Y., Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 404–414; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2e. Lee S. Y., Kang M. G., Park J. S., Lee G., Ting A. Y., Rhee H. W., Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 1837–1847; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2f. Fazal F. M., Han S., Parker K. R., Kaewsapsak P., Xu J., Boettiger A. N., Chang H. Y., Ting A. Y., Cell. 2019, 178, 473–490; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2g. Silahtaroglu A. N., Nolting D., Dyrskjøt L., Berezikov E., Møller M., Tommerup N., Kauppinen S., Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2520–2528; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2h. Von Wasielewski R., Mengel M., Gignac S., Wilkens L., Werner M., Georgii A., J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1997, 45, 1455–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Martell J. D., Deernick T. J., Lam S. S., Ellisman M. H., Ting A. Y., Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1792–1816; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Mihelc E. M., Angel S., Stahelin R. V., Mattoo S., J. Visualization 2020, 156, e60677. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Lat P. K., Liu K., Kumar D. N., Wong K. K. L., Verheyen E. M., Sen D., Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 5254–5267; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Einarson O. J., Sen D., Nuc. Acid Res. 2017, 45, 9813–9822; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Li W., Zeng W., Chen Y., Wang F., Wu F., Weng X., Zhou X., Analyst. 2019, 144, 4472–4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zuker M., Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 13, 3406–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rojas A. M., Gonzalez P. A., Antipov E., Klibanov A. M., Biotechnol. Lett, 2007, 29, 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Y., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Zhang L., Brinkman E. K., Adam S. A., Goldman R., van Steensel B., Ma J., Belmont A. S., J. Cell Biol. 2018, 11, 4025–4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary