Summary

Cutaneous mast cells mediate numerous skin inflammatory processes and have anatomical and functional associations with sensory afferent neurons. We reveal that epidermal nerve endings from a subset of sensory nonpeptidergic neurons expressing MrgprD are reduced by the absence of Langerhans cells. Loss of epidermal innervation or ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons increased expression of a mast cell gene module including the activating receptor, Mrgprb2, resulting in increased mast cell degranulation and cutaneous inflammation in multiple disease models. Agonism of MrgprD-expressing neurons reduced expression of module genes and suppressed mast cell responses. MrgprD-expressing neurons released glutamate which was increased by MrgprD agonism. Inhibiting glutamate release or glutamate receptor binding yielded hyperresponsive mast cells with a genomic state similar to that in mice lacking MrgprD-expressing neurons. These data demonstrate that MrgprD-expressing neurons suppress mast cell hyperresponsiveness and skin inflammation via glutamate release thereby revealing an unexpected neuro-immune mechanism maintaining cutaneous immune homeostasis.

Keywords: skin, Langerhans cell, mast cell, neuroimmunology, Mas-related G protein receptors, MrgprB2, nonpeptidergic neurons, MrgprD, S. aureus, Beta-alanine, glutamate

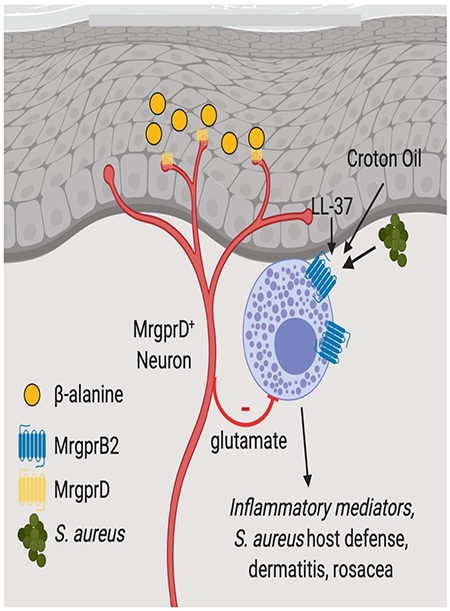

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Skin is an immunologically active barrier tissue that is exposed to a wide variety of microbial pathogens and environmental insults. In response to microbial-derived products or other exogenous triggers, skin-resident cells of the innate and adaptive immune system respond through the secreted factors to recruit immune effector cells and promote local inflammatory responses (Kashem et al., 2017). The skin is also densely innervated by sensory afferent neurons (Owens and Lumpkin, 2014). Recently, it has become appreciated that unmyelinated C-fibers expressing TRPV1 sense noxious stimuli resulting in painful sensation and play a key role in modulating cutaneous immunity through release of neuropeptides (Baral et al., 2019). In the skin, this neuron subset can be directly activated by products derived from pathogens such as S. aureus, C. albicans and S. pyogenes and is both necessary and sufficient to provide host defense against C. albicans infection (Chiu et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2019; Kashem et al., 2015; Pinho-Ribeiro et al., 2018). Similarly, house dust mite antigens activate TRPV1-expressing neurons resulting in release of the neuropeptide Substance P (SP) and subsequent mast cell (MC) degranulation (Serhan et al., 2019). Thus, TRPV1-expressing neurons appear to play an obligate role in the development of multiple cutaneous inflammatory responses.

The skin is also innervated by other types of sensory neurons including a nonpeptidergic subset identified based on expression of MrgprD (MAS-related G-protein-coupled receptor D). In mouse, MrgprD-expressing neurons are distinct from TRPV1-expressing neurons and along with other sensory neuron subsets express the ion channels TRPA1 which is a broad “chemosensor” and P2rxR3, an ATP receptor. (Beaudry et al., 2017; Cavanaugh et al., 2009; Usoskin et al., 2015; Vulchanova et al., 1998; Zylka et al., 2005). MrgprD-expressing neurons innervate the epidermis and are thought to be polymodal sensing itch, pain and mechanical stimuli (Cavanaugh et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012; Rau et al., 2009; Zylka et al., 2005). While these neurons play a well-known role in inflammatory pain (Qu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2019), their functions in modulating immune responses remain to be explored.

Connective tissue mast cells (MC) are skin-resident immune cells that quickly respond to allergens via cross-linking of the FcεRI resulting in release of granules containing many pre-formed inflammatory meditators (Galli and Tsai, 2012). Recently, MC were shown to express MAS-related G-protein-coupled receptor B2 (MrgprB2), a receptor required for MC activation and granule release in response to pseudo-allergens, house dust mite and bacterial quorum-sensing molecules (McNeil et al., 2015; Pundir et al., 2019; Serhan et al., 2019). MrgprB2 agonism was sufficient to augment host defense against dermo-necrotic S. aureus infection (Arifuzzaman et al., 2019). In addition to sensing exogenous ligands, MrgprB2 is also a receptor for endogenous ligands. MrgprX2, the human ortholog of MrgprB2 is a receptor for the antimicrobial peptide LL-37, a proteolytic cleavage product of cathelicidin (Subramanian et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2017). Mast cell activation by LL37 likely via MrgprX2 ligation is a key component of rosacea pathogenesis (Choi et al., 2019; Muto et al., 2014). MrgprB2 is also a receptor for SP, a neuropeptide released by many TRPV1-expressing neurons that is required for neurogenic inflammation and pain as well as the recruitment of innate immune cells to sites of injury (Azimi et al., 2016; Green et al., 2019; Serhan et al., 2019). It is not known if MC responses can be modulated by sensory afferent neurons other than those expressing TRPV1.

Langerhans cells (LC) are epidermal-resident antigen presenting cells that share many functions with dendritic cells but are ontogenetically closely related to macrophages (Ginhoux et al., 2006; Hoeffel et al., 2012). The two models used to functionally test in vivo LC requirement involve mice with genetic LC-specific expression of either the Diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR), which allow for inducible LC ablation following Diphtheria toxin (DT) administration, or the active Diphtheria toxin subunit A (DTA) which results in constitutive LC ablation (Bobr et al., 2010; Kaplan, 2017; Kaplan et al., 2005). Contact hypersensitivity (CHS) to epicutaneous applied hapten, a mouse model of human allergic contact dermatitis, is commonly employed to probe LC function (Kaplan et al., 2012). LC have been found to be both required for CHS responses and required to suppress CHS response depending in large part on the method of LC depletion and CHS methodology (Kaplan et al., 2008). LC are also suggested to suppress irritant dermatitis responses in humans and mice with reduced number of LC due to dietary zinc deficiency (Kawamura et al., 2012).

In this study, we examined functional interactions between immune cells and nonpeptidergic nerve fibers in skin of the mouse. We began by exploring the requirement of LC in suppression of rapid irritant dermatitis responses to epicutaneous application of croton oil. Such responses to the irritant were exaggerated by the long-term ablation of LC which in turn reduced epidermal innervation by MrgprD-expressing neurons. Notably, croton oil responses were dependent on mast cell degranulation, SP and MrgprB2. Ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons or LC resulted in MC hyperresponsiveness across multiple in vivo disease models. We reveal the likely molecular underpinnings of the hyperresponsive MC state by discovering an Mrgprb2 containing MC gene module whose expression is enhanced by ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons or LC and counter-regulated by the activation of MrgprD-expressing neurons. Finally, we show that glutamate released from MrgprD-expressing neurons and its sensing by MC reduces expression of many genes contained within the MC module and induces a state of redcued MC responsiveness. These data demonstrate that MrgprD-expressing neurons can modulate cutaneous immune responses and maintain MC homeostasis during the steady-state thereby revealing an unexpected neuro-immune pathway linking LC, nonpeptidergic neurons and MC.

Results

Long-term LC ablation increases irritant dermatitis

To determine whether epidermal Langerhans cell (LC) are required to suppress irritant dermatitis, we tested the effects of epicutaneous application of 1% croton oil on the ears of LCDTA mice that have a constitutive absence of LC and litter-mate (WT) controls (Bobr et al., 2010; Kaplan et al., 2005; Moon et al., 2001). We observed a brisk response as measured by increased ear thickness that peaked at 6 hours and largely resolved by 24 hours (Figure 1A). LCDTA mice showed markedly increased ear thickness at 6 hours compared with WT mice that decayed with kinetics similar to WT mice (Figures 1A and 1B). We also examined croton oil responses in Itgb6−/− Itgb8ΔKC mice (Itgb6−/− K14Cre Itgb8fl/fl) that constitutively lack LC through a Diphtheria toxin (DT)-independent mechanism (Mohammed et al., 2016). Itgb6−/− Itgb8ΔKC mice developed exaggerated croton oil responses similar to those seen in LCDTA mice (Figure 1C). We next examined croton oil responses in LCDTR mice that allow for inducible DT-mediated ablation of LC. Unexpectedly, short-term ablation of LC by administration of DT 3 days prior to croton oil challenge had no effect (Figure 1D). In contrast, long-term ablation of LC through weekly DT injections starting 30 days prior to croton application resulted in increased ear thickness. Thus, the absence of LC for at least 30 days prior to application of croton oil resulted in exaggerated irritant dermatitis.

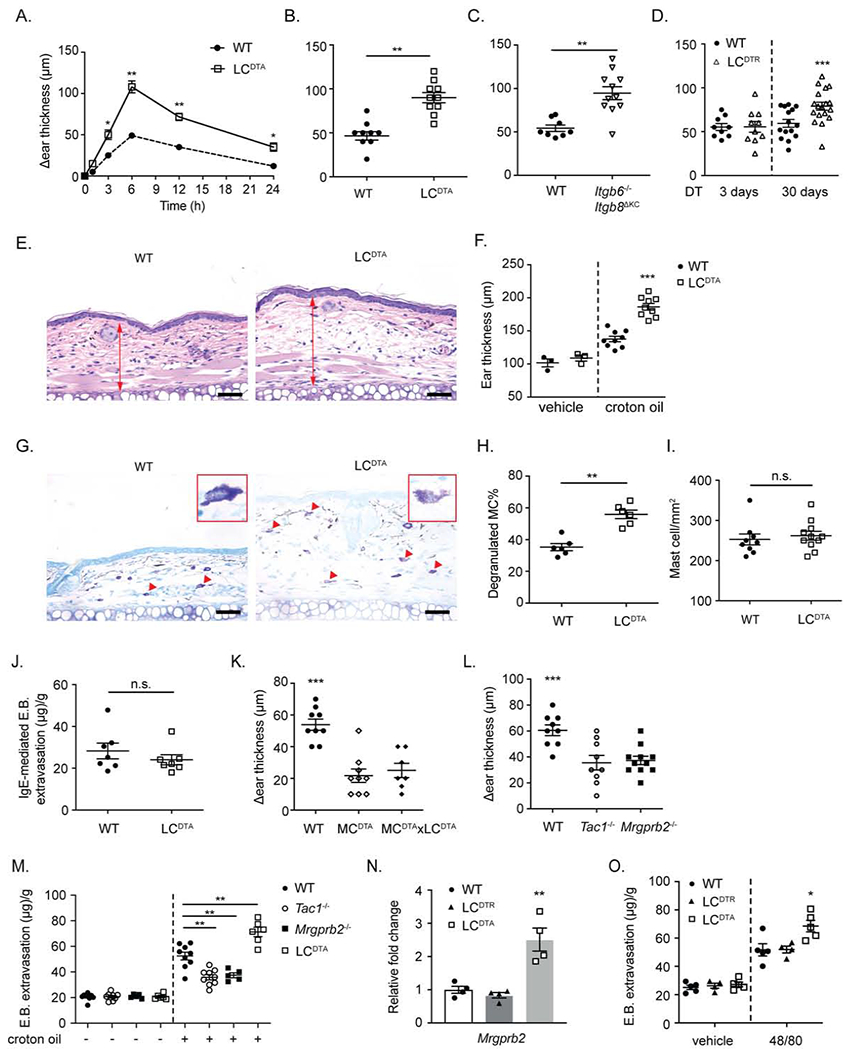

Figure 1. Long-term LC ablation increases mast cell Mrgprb2-mediated irritant dermatitis.

(A) The change in ear thickness over baseline between WT and LCDTA (constitutive LC ablation) at the indicated timepoint and (B) 6 hours after 1% croton oil application is shown. (C) As in B, except Itgb6−/− Itgb8μKC mice and littermate controls (WT) are shown. (D) Altered ear thickness over baseline for LCDTR or littermate controls (WT) treated with DT for 3 days (short-term LC ablation) or 30 days (long-term ablation) at 6 hours following 1% croton oil application is shown. (E) Representative H&E staining histological sections of ear skin from (B). (F) The distance from cartilage to epidermis as measured on H&E staining histological sections obtained from WT and LCDTA mice at 6 hours after 1% croton oil painting. (G) Representative toluidine blue staining of transverse ear sections from WT and LCDTA mice 6 hours after 1% croton oil application. Arrow indicated degranulated MC. One representative degranulated MC was highlighted in the inset. (H) The percentage of degranulated MC observed in (G) normalized to total MC number is shown. (I) Quantification of MC numbers in naive dorsal ear skins between WT and LCDTA mice based of avidin staining of transverse sections. (J) For passive cutaneous anaphylaxis, mouse ear skin was sensitized with anti-DNP IgE one day before the intravenous (i.v.) injection of DNP-HSA and Evans blue. Evans blue extravasation was measured 30 minutes after i.v. injection of DNP. (K, L) MCDTA mice (mast cell deficient), MCDTA x LCDTA mice, Tac1−/− mice (Substance P deficient), Mrgprb2−/− mice and littermate controls were challenged with 1% croton oil. Ear swelling was measured at 6 hours. (M) Quantification of Evans blue dye in flank skin of WT, Tac1−/−, Mrgprb2−/− or LCDTA mice after 30 mins epicutaneous application of croton oil. (N) Mrgprb2 mRNA expression as analyzed by RTqPCR from FACSorted dermal ear MC isolated from naive WT, LCDTA (long-term LC ablation) and LCDTR (short-term LC ablation) mice. (O) Quantification of Evans blue dye extravasation after i.d. administration of compound 48/80 to naive WT, LCDTA or LCDTR (short-term ablation) mice. Results are represented as mean ± SEM from 2-3 independent experiments. Each symbol in (A) represents mean in a group size of 4-5 animals. Each symbol in (B, C, D, F, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O) represents data from an individual animal. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (A, B, C, H, I, J, M) and one-way ANOVA (D, F, K, L, N, O). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Scale bars in E and G represent 50 μm.

Long-term LC ablation increases mast cell expression of Mrgprb2

To identify the mechanism driving exaggerated croton oil responses in long-term LC-deficient mice, we compared the transcriptomes of whole ear tissue from untreated LCDTA mice (long-term LC ablation) or LCDTR mice 3 days after DT administration (short-term LC ablation). LC were efficiently ablated in both mice (Figures S1A and S1B). Differentially expressed transcripts from unstimulated LCDTA and LCDTR skin showed GSEA enrichment for a dermal MC signature in LCDTA mice (Dwyer et al., 2016), but not other immune cell types (Figure S1C and Table S1). These data suggest that MC numbers and/or their susceptibility to activation are altered by the long-term absence of LC.

To distinguish between the aforementioned possibilities, we compared histologic sections of ears 6 hours after croton oil application. LCDTA ears showed increased edema compared to WT mice (Figures 1E and 1F) and a minimal inflammatory infiltrate that was confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure S1D). We found that the number of degranulated MC following croton oil treatment was increased in LCDTA compared to WT mice (Figures 1G–H) but the number of dermal MC and the response to FcεRI-mediated activation in a passive cutaneous anaphylaxis assay were equivalent in both groups (Figure 1I–J). Mcpt5-Cre x Rosa.26.DTA (MCDTA) mice (Scholten et al., 2008) which lack MC (Figure S1E) showed greatly attenuated croton oil mediated ear swelling and the exaggerated croton oil response in LC-deficient mice was absent in mice lacking both LC and MC (MCDTAxLCDTA mice) (Figure 1K). From these data we conclude that the long-term absence of LC does not alter dermal MC numbers but results in their enhanced degranulation in response to croton oil via a FcεRI-independent mechanism.

Recently, Mas-Related G Protein Coupled Receptor B2 (MrgprB2) which is expressed exclusively by MC was shown to mediate FcεR-independent MC degranulation in response to a variety of exogenous (e.g. antibiotics, house dust mite) and endogenous (e.g. Substance P, LL37, β-defensins) ligands (Azimi et al., 2016; McNeil et al., 2015; Serhan et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2017; Zhang and McNeil, 2019; Zhang et al., 2017). House dust mite (HDM) has been shown to induce MC degranulation in skin through a mechanism in which HDM-activated TRPV1-expressing neurons release SP that activates MrgprB2 expressed on MC (Serhan et al., 2019). Since the croton oil response requires MC, we hypothesized that croton oil-mediated inflammation could also involve SP and MrgprB2. We observed that the croton oil response as measured by ear thickness 6 hours after application was reduced in SP-deficient (Tac1−/−) and Mrgprb2−/−-deficient mice (Figure 1L). To more directly assay MC responses, we measured extravasation of Evans blue dye 20 minutes after application of croton oil. Dye extravasation was reduced in Tac1−/− and Mrgprb2−/− mice but increased in LCDTA mice (Figure 1M). Importantly, RNA-seq analysis of LCDTA ear tissue revealed Mrgprb2 transcripts to be significantly increased (Table S1). We confirmed increased Mrgprb2 transcript expression in FACSorted dermal MC isolated from LCDTA but not from WT or 3-day DT-treated LCDTR mice (Figure 1N). Finally, we compared mast cell degranulation in response to compound 48/80, a MrgprB2 ligand (McNeil et al., 2015). We observed increased Evans blue dye extravasation and reduced Avidin staining of MC granules in LCDTA compared with WT or LCDTR mice, consistent with increased expression and activity of Mrgprb2 in the long-term absence of LC (Figures 1O and S1F). From these data we conclude that croton oil-mediated irritant dermatitis involves SP-and MrgprB2-mediated mast cell activation. Furthermore, long-term absence of LC results in increased expression of Mrgprb2 by dermal mast cells and their enhanced activation to MrgprB2 ligands.

Epidermal non-peptidergic nerve endings are reduced by long-term LC ablation

Both LC and MC have well-known anatomic associations with sensory afferent neurons (Hosoi et al., 1993; Serhan et al., 2019). We hypothesized that the heightened mast cell responses observed upon the long-term ablation of LC could involve dysregulation of MC-neuronal communication. A reduction in the number of epidermal free nerve endings has been reported following long-term ablation of LC (Doss and Smith, 2014). We confirmed this finding by comparing the density of Pgp9.5 immunolabeled nerve fibers in epidermal whole mounts from control and LCDTA mice (Figure 2A). As expected, LCDTA showed a notable reduction in epidermal nerve fiber density. Quantification of intra-epidermal nerve fibers (IENF) by immunofluorescent microscopy of transverse sections showed reduced numbers only with long-term LC depletion (LCDTA 30-day DT-treated LCDTR), but not short-term LC ablation (3-day DT-treated LCDTR) (Figures 2B–C and S2A). Most epidermal nerve fibers expressed the GDNF family receptor α2 (GFRα2) which is primarily expressed by nonpeptidergic cutaneous neurons (Lindfors et al., 2006) while few were positive for GFRα3, a receptor expressed by peptidergic neurons (Figures 2D–E and S2B). LCDTA skin also showed reduced epidermal GFRα2-positive fibers in epidermal and transverse sections (Figures 2D and S2C). In addition, the relative number of CGRP-positive nerve fibers was unaffected in LCDTA mice (Figure S2D). Based on these data, we conclude that long-term LC ablation results in reduced epidermal GFRα2-positive, nonpeptidergic nerve endings.

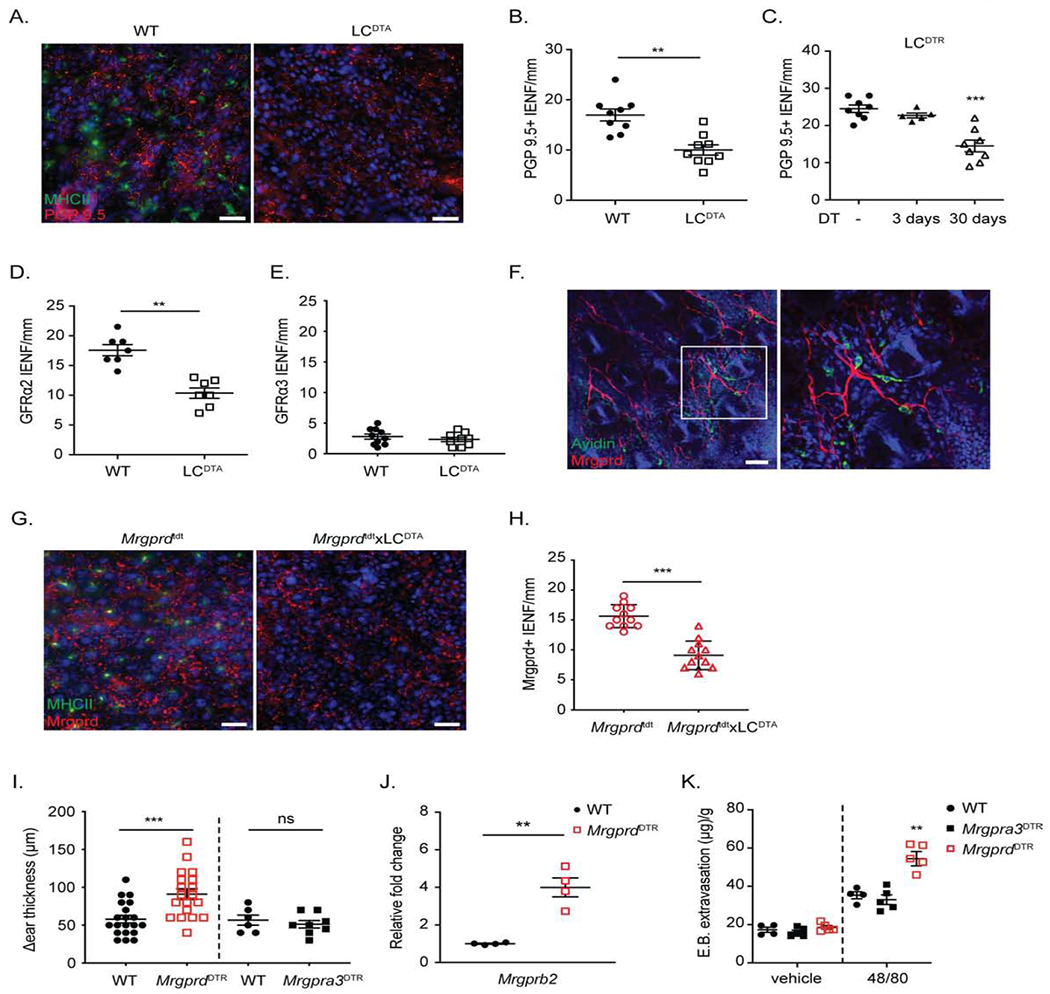

Figure 2. Epidermal MrgprD-expressing nerve endings are reduced by long-term LC ablation.

(A) Representative immunofluorescent microscopic image of an epidermal whole-mount from WT and LCDTA mice ears stained for MHC-II to identify LC (green) and PGP 9.5 to identify neuron (red). (B) Quantification of intra-epidermal nerve fiber number (IENF) from transverse skin sections stained with PGP 9.5 from LCDTA and littermate (WT) controls. (C) As in B except IENF were quantified from LCDTR mice treated with PBS (−) or with DT for 3 days or 30 days. (D, E) Quantitative analysis of IENF from transverse section stained with GFRα2 (D) or GFRα3 (E) from WT and LCDTA mice. (F) Representative confocal image of MrgprdTdT skin whole mount to identify MC (green) and MrgprD-expressing neurons (red). (G) Representative epidermal whole-mounts from the ears of MrgprdTdT and MrgprdTdTxLCDTA mice stained for MHC-II to identify LC (green) are shown. (H) Quantification of IENF of MrgprD+ nerve from transverse skin sections from MrgprdTdT and MrgprdTdT x LCDTA mice. (I) Ear thickness at 6 hours following application of 1% croton oil in MrgprdDTR or Mrgpra3DTR mice treated with control PBS or DT is shown. (J) Mrgprb2 mRNA expression in FACSorted dermal mast cells isolated from naive PBS or DT treated MrgprdDTR mice is shown. (K) Quantification of Evans blue dye 20 mins after challenged with vehicle or compound 48/80 in WT mice or DT treated Mrgpra3DTR, MrgprdDTR mice. Each symbol represents data from an individual animal. Results are represented as mean ± SEM from 2-3 individual experiments with cohorts of n=3-4. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (B, D, E, H, I, J) and one-way ANOVA (C, K). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; n.s, no significant difference. Scale bars represent 20 μm in A, G; and 50 μm in F.

Ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons phenocopies long-term LC deletion

Cutaneous MrgprD-expressing neurons are a distinct subset of C-fibers that express GFRα2 and innervate the epidermis (Zylka et al., 2005). To determine whether MrgprD-expressing neurons are reduced in the absence of LC, we generated Mrgprd-Cre x Rosa.26. TdTomato (MrgprdTdT) mice and bred them with LCDTA mice. We observed numerous TdT-positive nerve fibers in the epidermis. TdT-positive fibers were also closely associated with dermal MC, consistent with published reports (Serhan et al., 2019)(Figure 2F). Importantly, long term deletion of LC resulted in reduction of the TdT-positive nerve fibers (Figure 2G–H).

To determine whether ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons could alter MC function thereby linking LC ablation with increased MC activation, we bred Mrgprd-Cre mice with Rosa.26.DTR mice to generate MrgprdDTR mice. These mice allow for the inducible ablation of MgprD-expressing neurons following administration of DT for 3-4 weeks (Pogorzala et al., 2013). We found that DT treated MrgprdDTR mice developed increased ear thickness at 6 hours compared to control mice following croton oil application (Figure 2I). Ablation of a different subset of epidermal nonpeptdergic neurons in DT treated Mrgpra3DTR mice (Han et al., 2013) did not affect croton oil responses thereby demonstrating specificity for MrgprD-expressing neurons. FACSorted MC isolated from the skin of DT treated MrgprdDTR mice showed increased expression of Mrgprb2 mRNA (Figure 2J). Finally, we observed that vascular extravasation of Evans blue dye following administration of compound 48/80 was exaggerated in DT treated MrgprdDTR but not Mrgpra3DTR mice while dermal MC number and FcεR-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis were unaffected (Figures 2K, S2E–F). Based on these results, we conclude that ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons phenocopies the heightened MC responses observed in long-term LC-deficient mice.

Ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons or LC augments S. aureus host defense and CHS

Dermal MC activation is required for efficient host defense against intradermal injection (i.d.) S. aureus infection and can be augmented with exogenous MrgprB2 ligands (Arifuzzaman et al., 2019). To determine the effects of deleting MrgprD-expressing neurons or LC on S. aureus infection, we initiated a localized dermo-necrotic infection by i.d. injection of 107 S. aureus USA300 into dorsocaudal skin of in MrgprdDTR and LCDTA mice, respectively. WT mice develop large necrotic ulcers that slowly resolved during the observation period. MrgprdDTR mice developed much smaller skin lesions that contained 10-fold fewer S. aureus CFU on day 10 post infection (Figures 3A–B and 3D). We observed that long-term LC ablated (LCDTA) but not short-term LC ablated (3-day DT-treated LCDTR) mice also showed increased host defense to S. aureus that manifested as smaller S. aureus lesions and reduced S. aureus CFU in skin on day 10 post infection (Figures 3C–D and S3A). Control MCDTA mice were less able to control the S. aureus infection and developed larger necrotic lesions with increased CFU. These data demonstrate that MrgprdDTR and LCDTA mice, which similarly manifest increased expression of Mrgprb2 in dermal MC are more resistant to dermo-necrotic S. aureus infection.

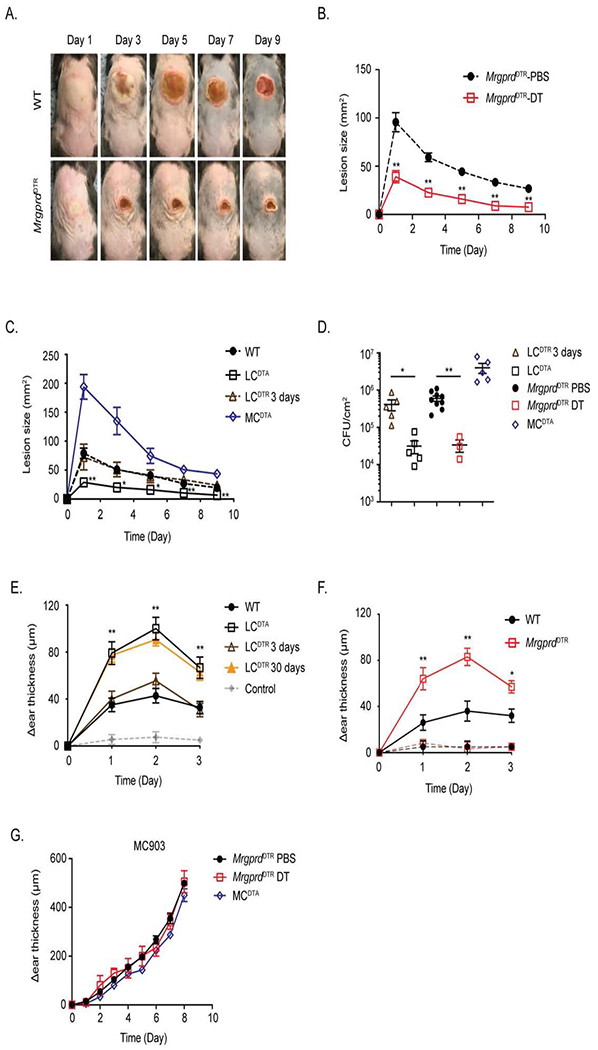

Figure 3. Ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons or LC augments S. aureus host defense and CHS.

(A) Representative images of skin lesions from PBS (WT) or DT treated MrgprdDTR mice on indicated day after i.d. inoculation with 107 S. aureus. (B) Skin lesion area calculated using ImageJ from PBS or DT-treated MrgprdDTR mice at the indicated time is shown. (C) As in B, skin lesion area is shown at the indicated time for WT, LCDTA, 3-day DT-treated LCDTR and MCDTA mice. (D) Quantification of CFU isolated from infected skin tissue at Day 10 after infection from mice in B and C. (E) WT, LCDTA, 3-day or 30-day DT-treated LCDTR and MCDTA mice were sensitized with 0.25% DNFB on shaved abdomens on day 0, followed 5 days later with a 0.2% DNFB challenge on the ear. The data shown represent the change in ear thickness at the indicated time with the thickness prior to challenge. The change in ear thickness of all mice sensitized with vehicle was merged into grey line. (F) As in E, comparing DNFB CHS responses sensitized with 0.25% DNFB (thick lines) or vehicle alone (thin lines) in PBS or DT-treated MrgprdDTR mice. (G) The ears of PBS or DT treated MrgprdDTR and MCDTA mice were daily challenged with MC903 and monitored for ear swelling. Results are represented as mean ± SEM from two independent experiments using cohorts of 4-7 mice each for B, C, E, F and G. Each symbol in D represents data from an individual animal. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test to compare with WT group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Contact hypersensitivity (CHS) to small molecule haptens is a classic mouse model of allergic contact dermatitis. In this model, MC are required for dendritic cell activation following hapten exposure and CHS is reduced in the absence of MC (Dudeck et al., 2011; Reber et al., 2017). We employed the CHS model in which mice are sensitized with the hapten 1-fluoro-2,4-dinotro-benzene (DNFB) on the abdomen and challenged with the same hapten 5 days later on the ear to measure of the effector response. MrgprdDTR and long-term LC deficient LCDTA mice but not short-term LC deficient 3-day DT treated LCDTR or WT mice developed greatly exaggerated CHS that peaked and resolved with similar kinetics (Figure 3E–F). Finally, using a mouse model of atopic dermatitis involving repeated application of MC903 that results in TSLP-mediated activation of ILC2 which is independent of MC (Kim et al., 2013; Li et al., 2006), we observed that inflammation was unaffected by the absence of MrgprD-expressing neurons (Figure 3G). Thus, MrgprdDTR mice phenocopy mice with long-term absence of LC in four distinct inflammatory or protective immune responses that are known to require MCs: intradermal 48/80, irritant dermatitis to croton oil, allergic contact dermatitis to DNFB, and host defense against dermo-necrotic S. aureus infection.

MrgprD agonism suppresses MC activation

Beta-alanine (β-ala) is a MrgprD agonist that activates and enhances the excitability of MrgprD-expressing neurons (Liu et al., 2012; Rau et al., 2009; Shinohara et al., 2004). Based on our observation that MrgprD-expressing neurons are required to suppress MC activation, we hypothesized that augmenting their activation through exogenous administration of β-ala would suppress MC activation and be accompanied by reduced expression of Mrgprb2 in MC. To test this hypothesis, WT and DT treated MrgprdDTR mice were injected at distinct skin sites with β-ala for two days followed by i.v. administration of Evans blue dye. Mice were then challenged with i.d. saline or compound 48/80. Compound 48/80 induced dye extravasation in WT mice at the PBS pretreated site, but the response was diminished at the β-ala pretreated site (Figure 4A–B). As expected, compound 48/80 induced increased MC degranulation in DT treated MrgprdDTR mice and pretreatment with β-ala had no effect. Thus, pretreatment with β-ala attenuated MC activation in WT mice and its action required the presence of MrgprD-expressing neurons. β-ala pretreatment did not induce scratching behavior, showed no effect on FcεR-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis and did not alter the number of dermal MC (Figure S4A–C). Interestingly, suppression of MC function required administration of β-ala for at least 2 days and was not effective when coadministered with compound 48/80 challenge (data not shown).

Figure 4. MrgprD agonism suppresses MC activation.

(A) Representative images and (B) quantification of Evans blue extravasation 20 minutes after i.d. administration with vehicle or compound 48/80 to PBS or DT-treated MrgprdDTR mice. Mice were locally pre-treated for 2 days with either i.d. PBS or β-ala. (C) Mrgprb2 mRNA expression in flank skin of indicated mice treated with i.d. PBS or β-ala for 2 days as assessed by RTqPCR. (D) Skin lesion area following i.d. inoculation of 107 S. aureus in WT mice. Mice were pretreated at the site of inoculation with i.d. PBS or β-ala for 2 days prior to and daily injected after S. aureus infection. (E) CFU isolated from skin tissue in D on day 10 post infection. (F) WT and MrgprdDTR mice were i.d. injected on abdominal for 2 days with either PBS or β-ala. Mice were then sensitized at the same location with 0.25% DNFB followed 5 days later with a 0.2% DNFB challenge on the ear. The data shown represent the change in ear thickness at the indicated time with the thickness prior to challenge. Representative images (G) and erythema area of back skin (H) after i.d. injected of LL-37 mixed with PBS or β-ala for two days. White dashed circle represents the area of LL-37 injection. (B, C, E, H) Each symbol represents data from an individual animal. (D, F) Results are represented as mean ± SEM from 2-3 individual experiments with cohrts of n=4-7. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; n.s, no significant difference.

To analyze the effect of β-ala on the relative expression of Mrgprb2 transcripts in MC, we administered 50 mM β-ala or PBS by i.d. injection in WT mice once daily for 2 days. Consistent with our hypothesis, expression of Mrgprb2 was reduced approximately 3-fold (Figure 4C). In addition, expression of Mrgprb2 was elevated in DT treated MrgprdDTR mice and administration of β-ala did not modify the elevated transcript levels. Thus, the stimulation of MrgprD-expressing neurons with β-ala appears to reduce MrgprB2 mediated activation of MC in part by downregulation of Mrgprb2 expression.

We next tested the capacity of β-ala to suppress MC function in several mouse models of human disease. Using the dermo-necrotic S. aureus model, we observed that β-ala administration to WT mice inhibited host defense resulting in enlarged skin lesions and increased CFU on day 10 post infection (Figures 4D–E, S4D). In addition, β-ala pretreatment prior to DNFB sensitization significantly blunted the development of CHS in WT mice but had no effect in MrgprdDTR mice (Figure 4F). Finally, we tested whether β-ala could suppress inflammation in a mouse model of Rosacea based on i.d. injection of LL-37, a cleavage product of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin that activates mast cells likely via the MrgprB2 receptor (Choi et al., 2019; Muto et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2017). We found that pretreatment of WT mice with β-ala inhibited LL-37-mediated skin erythema and suppressed expression of the Rosacea linked biomarkers, Cma1, Klk5 and Mmp9 (Figures 4G–H and S4E). Thus, β-ala agonism of MrgprD-expressing neurons in WT mice is sufficient to functionally reduce steady-state MC expression of Mrgprb2 and reduce inflammation in multiple skin disease models in which MC are known to play a key role. These phenotypes are opposite of those observed with deletion of MrgprD-expressing neurons and LC in MrgprdDTR and LCDTA mice, respectively, strongly suggesting a molecular pathway that reciprocally programs the pre-activation state of dermal mast cells through their cross-talk with MrgprD-expressing neurons.

A coherent MC gene expression program that is reciprocally modulated by perturbation of MrgprD-expressing neurons

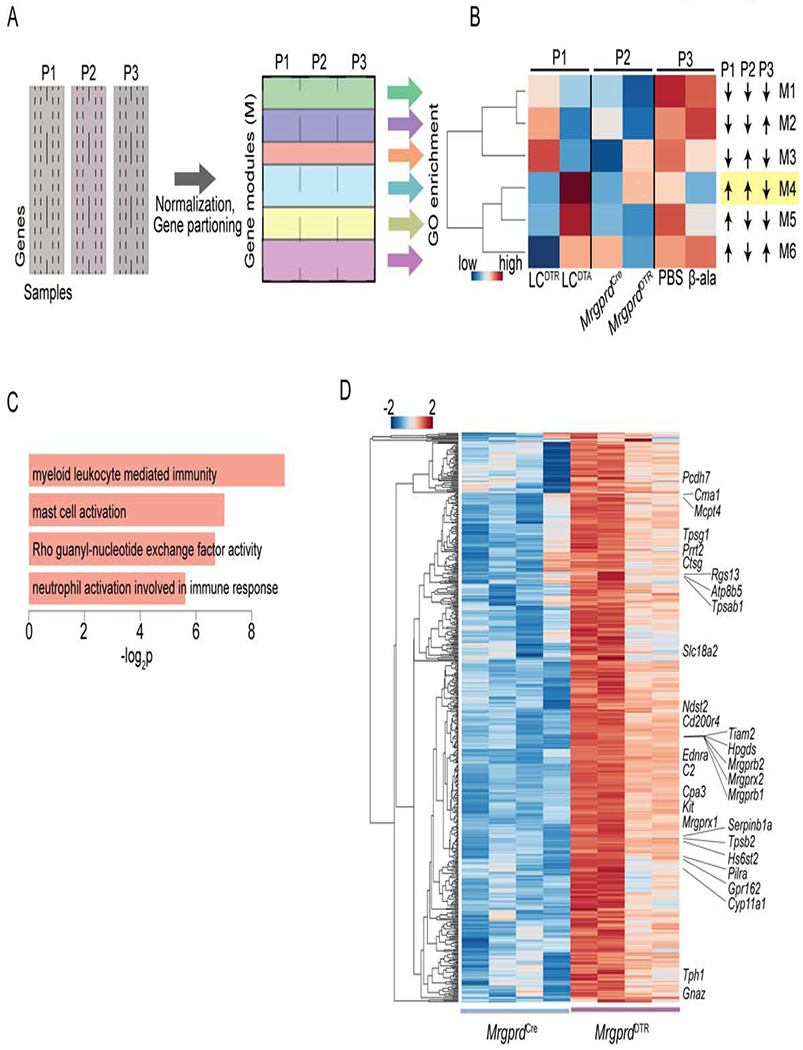

We next sought to determine whether the enhanced MC activity observed in LCDTA and MrgprdDTR mice as well as its attenuation in β-ala treated WT mice could have shared molecular underpinnings. To do so, we sought to uncover a coherent pattern of transcriptional alterations in skin of LCDTA and MrgprdDTR mice that were reciprocally impacted by β-ala treatment in WT mice. We performed RNAseq using mRNA isolated from whole ear tissue of DT treated MrgprdDTR mice, DT treated control MrgprdCre mice and WT mice treated once daily for 2 days with 50 mM β-ala or vehicle. RNAseq datasets from LCDTA mice (long-term LC ablation) or LCDTR mice 3 days after DT administration (short-term LC ablation) were included in the analytic pipeline (Table S1). We utilized a generalizable computational approach that enables simultaneous analysis of RNAseq datasets generated by multiple and diverse perturbations of an experimental system to uncover coherent and where possible reciprocally regulated patterns of gene expression (Figure 5A). This approach is dependent on normalization of gene transcript values using z-scores within a sample and then across the various samples constituting a given perturbation (P). The transformed data involving the various perturbations (P1 – Pn) is then combined and analyzed by one-dimensional hierarchical clustering to partition clusters of genes (gene modules) that manifest similar or reciprocal dynamic patterns with respect to the various perturbations of the system. Finally, GO enrichment analysis reveals gene modules and associated molecular pathways that may account for the shared or reciprocal phenotypic changes associated with the diverse perturbations. Application of the computational pipeline to the RNAseq datasets from the three perturbations generated 6 coherent gene modules (Figure 5B). The M4 module displayed a dynamic that fit expectations generated by the phenotypic analyses in that it represented a group of genes whose expression was induced by long-term loss of LC and deletion of MrgprD-expressing neurons. In contrast, M4 module genes were downregulated by β-ala administration (Figures 5B, S5A and Table S2). GO pathway enrichment analysis of M4 genes showed significant enrichment of those involved in mast cell activation (Figure 5C). We note that pairwise comparison of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the three distinct perturbations revealed a set of MC genes that were contained within the M4 module (Figure S5B). To determine whether a subset of M4 module genes reflected their perturbation-induced dynamics specifically in MC, RNAseq analysis was performed on purified MC isolated from DT treated MrgprdDTR and control MrgprdCre mice (Table S1). Genes that were differentially expressed in MC upon deletion of MrgprD-expressing neurons were intersected with M4 genes. A heatmap comprising these genes and their expression in MC upon ablation of MrgprD-expressing neurons is shown in Figure 5D. Biologically important genes are annotated and include Mrgprb2, other Mrgprs as well as proteases such as Cpa3, Ctsg and Tpsg1 that are components of MC secretory granules. Thus, long-term deletion of LC or elimination of MrgprD-expressing neurons programs MCs into a hyper-responsive state that involves upregulation of a gene module that encompasses Mrgprb2 as well as several proteases that function as inflammatory mediators upon MC activation and degranulation.

Figure 5. A MC gene module that is coherently modulated by LC ablation and perturbations of MrgprD-expressing neurons.

(A) Schematic depicting generalizable computational approach that enables simultaneous querying of RNAseq datasets generated by multiple and diverse perturbations of an experimental system to uncover coherent and where possible reciprocally regulated patterns of gene expression. The approach is dependent on normalization of gene transcript values using z-scores within sample and across the samples constituting a given perturbation (P). The transformed data involving the various perturbations (P1 – Pn) is then combined and analyzed to partition clusters of genes (gene modules). GO enrichment analysis reveals gene modules and associated molecular pathways. (B) Application of the computational pipeline to the RNAseq datasets from mouse earskin samples obtained from the three indicated perturbations and their relevant controls. The approach delineated 6 coherent gene modules (M1-M6). The M4 module is highlighted as its expression dynamic fits various phenotypic expectations. (C) GO pathway enrichment analysis of M4 genes (n=3,172) displaying significant categories and their enrichment −log P values. (D) Heatmap comprising genes that are significantly upregulated (n=501, p = < 0.05) in purified MC upon deletion of MrgprD-expressing neurons. The entire set of genes is listed in Table S3. These genes are also contained within the M4 module. Fisher’s exact test was used to establish significance of overlap of these genes in module 4 when comparing with those up-regulated in skin mast cells of MrgprdDTR mice (odds ratio of 1.27, p-value of 9.4E-6).

MrgprD-expressing neurons suppress mast cells via glutamate release.

To determine how MrgprD-expressing neurons alter MC transcription and function, we first explored whether release of SP or CGRP from TRPV1-expressing neurons could be increased in LCDTA or MrgprdDTR mice. QPCR of whole dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) from MrgprdDTR mice revealed the expected decrease of the genes Mrgprd, Trpa1 and P2xr3, known to be enriched in MrgprD-expressing neurons (Reynders et al., 2015; Usoskin et al., 2015) (Figure S6A). The genes encoding for the neuropeptides CGRP (Calca) and SP (Tac1), however, were unaffected in either LCDTA or MrgprdDTR mice. We also observed equivalent release of CGRP and SP from capsaicin stimulated cultured DRG cells isolated from WT and MrgprdDTR mice (Figure S6B). Thus, increased MC activation by TRPV1-expressing neurons appears unlikely to explain altered MC phenotype in LCDTA or MrgprdDTR mice.

Glutamate is a well-described neurotransmitter that is known to be released by all cutaneous sensory afferents (Jahr and Jessell, 1985; Schneider and Perl, 1985). The vesicular glutamate transporter vGlut2 (Slc17a6) is required for loading glutamate into synaptic vesicles and is widely expressed by neurons in the DRG (Liu et al., 2010; Scherrer et al., 2010). Slc17a6 (vGlut2) expression was modestly but significantly reduced in whole DRGs isolated from LCDTA mice (Figure 6A). Similarly, DRG cells from WT mice cultured in vitro in the presence of β-ala showed increased expression of Slc17a6 (vGlut2) which was not observed in DRG isolated from MrgprdDTR mice (Figure 6B). We next examined glutamate release from cultured DRG cells. The TRPA1 agonist, AITC, efficiently triggered glutamate release in cultured DRGs isolated from WT mice (Figure 6C). Notably, WT DRGs cultured in β-ala for 48 hours released higher levels of glutamate in response to AITC (Figure 6D). In contrast, DRGs isolated from LCDTA mice released lower amounts of glutamate (Figure 6E). Thus, glutamate release is increased by β-ala exposure and reduced in LCDTA mice.

Figure 6. MrgprD-expressing neurons suppress mast cells responsiveness via glutamate release.

(A) Slc17a6 (vGlut2) mRNA expression in L1-5 dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells of WT, LCDTA, or DT treated MrgprdDTR mice analyzed by RTqPCR. (B) Slc17a6 (vGlut2) mRNA expression in cultured DRGs isolated from naïve PBS or DT treated MrgprdDTR mice incubated with vehicle or 2 mM β-ala for 24 h. (C) Glutamate release from WT cultured DRGs stimulated with 100 μM Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) for 10 mins, or (D) pre-incubated with vehicle or 2 mM β-ala for 24 hours prior to AITC stimulation. (E) Glutamate release from AITC stimulated cultured DRGs from naive WT and LCDTA mice. (F) Mrgprb2 mRNA expression in unmanipulated flank skin of WT and MrgprdΔvGlut2/+ mice as assessed by RTqPCR. (G) Quantification of Evans blue dye 20 mins after challenged with vehicle or compound 48/80 in WT and MrgprdΔvGlut2/+ mice. (H) Gene expression patterns of ionotropic NMDA-, AMPA-, kainate-receptors and metabotropic receptors on the indicated mast cell subsets. Raw data were obtained from Table S1, database of GSE37448 (dermal MC) and GSE109125 (peritoneal-derived MC) (Dwyer et al., 2016; Yoshida et al., 2019). (I) As in F, comparing Mrgprb2 mRNA expression in flank skin of indicated mice pretreated with daily i.d. 50 μM NS102, 50 mM β-ala or vehicle administration for 2 days. (J) As in G, quantification of Evans blue dye is shown for PBS or DT-treated MrgprdDTR mice pretreated with daily i.d. 50 μM NS102, 50 mM β-ala or vehicle administration for 2 days. Each symbol represents data from an individual animal. Results are represented as mean ± SEM from 2-3 independent experiments with cohorts of n=3-4. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (C, D, E, F, G, I, J) and one-way ANOVA (A, B). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; n.s, no significant difference.

Finally, to determine whether glutamate release from MrgprD-expressing neurons regulate MC function, we bred MrgprdCre with Slc17a6f/f mice to generate MrgprdΔvGlut2/+ mice (Tong et al., 2007). These mice have the loss of a single allele of Slc17a6 in MrgprD-expressing neurons and reduced glutamate release without generating potential developmental defects or compensatory effects resulting from the complete absence of Slc17a6 (Schallier et al., 2009; Tupal et al., 2014). Notably, expression of Mrgprb2 was increased approximately 4-fold in unmanipulated MrgprdΔGlut2/+ skin and i.d. challenge with compound 48/80 resulted in increased Evans blue dye extravasation consistent with increased mast cell activation (Figure 6F–G). Thus, glutamate released from MrgprD-expressing neurons reduced expression of Mrgprb2 in MC and attenuated their responsiveness during homeostasis.

Glutamate directly alters mast cell transcriptional programming and function

The glutamate family of receptors is comprised by several categories of receptors including ionotropic NMDA-, AMPA-, and kainate-type receptors as well metabotropic receptors (Reiner and Levitz, 2018). We compared expression of glutamate receptors in our RNAseq dataset of sorted dermal MC isolated from control and MrgprdDTR mice (Table S1). We observed highest transcripts for Grik2 (GluR6) and Grik5 (KA2) which are both members of the kainate glutamate receptor family (Figure 6H). A similar expression pattern was observed in previously reported data sets of dermal and PCMC-derived MC (Dwyer et al., 2016; Yoshida et al., 2019). KA2 is an obligate heterodimer which functions only in combination with GluR5-7 (Kumar et al., 2011), thus the most likely glutamate receptor in mast cells is a heterodimer of KA2 and GluR6. NS102 is a selective antagonist for GluR6 containing glutamate receptor complexes (Verdoorn et al., 1994). To determine whether KA2/GluR6 is operative in MC and whether it affects MC programming and function in vivo, we administered 50 μM NS102 i.d. into flank skin of WT and MrgprdDTR mice twice daily for 2 days and assayed Mrgprb2 expression and compound 48/80 responses. Pretreatment with NS102 increased expression of Mrgprb2 and extravasation of Evans blue dye following compound 48/80 challenge to levels similar to those observed in MrgprdDTR mice (Figure 6I–J). Notably, NS102 had no effect in MrgprdDTR mice or in WT mice pretreated with β-alanine indicating that NS102 acts downstream of glutamate release.

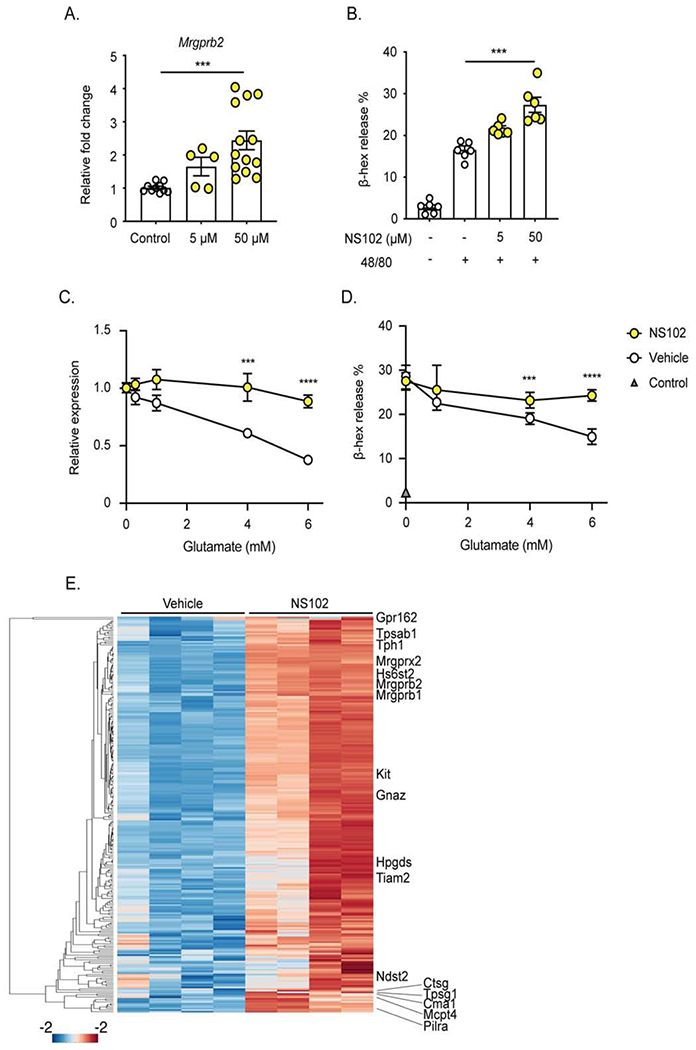

To determine if glutamate can act directly on MC, we utilized in vitro cultures of peritoneal-derived mast cells (PCMC). High purity PCMC were obtained after a 3-4-week culture of peritoneal cells from WT mice in IL-3 and stem cell factor (Figure S7A). PCMC cultured for 48 hours in the presence of NS102 showed a dose-dependent increase in expression of Mrgprb2 and increased β-hexosaminidase release 40 minutes after stimulation with compound 48/80 (Figure 7A–B). In contrast, PCMC transferred into glutamate-free Tyrode’s buffer for 6 hours showed a dose-dependent decrease in Mrgprb2 expression and compound 48/80-induced β-hexosaminidase release with varying concentrations of glutamate supplementation (Figure 7C–D). We did not observe cell death or MC degranulation in the presence of glutamate at 6 hours but PCMC could not maintain viability in Tyrode’s buffer beyond 6 hrs (Figure S7B–C). To comprehensively analyze alterations in MC transcriptional programming in response to modulation of glutamate signaling we performed RNAseq with mRNA isolated from PCMC cultured for 48 hours with vehicle or NS102 and PCMC cultured for 6 hours in glutamate-free Tyrode’s buffer supplemented with vehicle or 4 mM glutamate. A large set of genes showed a reciprocal expression pattern with the opposing modulations of glutamate signaling, increasing with NS102 inhibition and diminishing with glutamate supplementation (Figure S7D). Importantly, when we overlapped the DEGs induced by inhibition of glutamate signaling in PCMC with the upregulated genes in sorted dermal MC from MrgprdDTR mice (Figure 5D), we observed a very strong positive enrichment (p=1.89x10−17) (Figure 7E). Thus, inhibition of glutamate signaling, likely through the KA2/GluR6 receptor complex, programs a hyper-active mast cell gene expression state in vitro that strongly resembles the hyperreactive mast cell state caused by loss of MrgprD-expressing neurons in vivo.

Figure 7. Glutamate directly alters mast cell transcription and function.

(A) Mrgprb2 mRNA expression of peritoneal-derived mast cells (PCMC) incubated with indicated concentration (μM) of the GluR6 inhibitor NS102 for 48 hours. (B) β-hexosaminidase (β-hex) release of PCMC cultured for 48 hours in the indicated concentration of NS102 then stimulated by compound 48/80. (C, D) PCMC were transferred into glutamate-free Tyrode buffer and supplemented with the indicated concentration of glutamate and vehicle or 50 μM NS102. After 6 hours of culture, (C) Mrgprb2 mRNA expression and (D) β-hexosaminidase (β-hex) in response to compound 48/80 are shown. (E) Heatmap comprising genes that are significantly upregulated (n=245, p = < 0.05) in cultured PCMC upon inhibition of Glutamate receptor signaling with NS102. These genes are also contained within the group of 501 MC genes delineated in Figure. 5D. Fisher’s exact test was used to establish significance of the overlap of these genes when comparing with those up-regulated in Figure. 5D (odds ratio of 2.22, p-value of 1.89E-17). The entire set of genes is listed in Table S3. Each symbol represents data from an individual sample. Results are represented as mean ± SEM from 2-3 individual experiments. Each symbol in (C, D) represents mean in a group size of 4-7 samples. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test. ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Herein, we document the existence of a neuro-immune regulatory pathway in which MrgprD-expressing afferent neurons in the skin suppress MC hyperresponsiveness via glutamate-induced transcriptional reprogramming of MC thereby maintaining cutaneous immune homeostasis. Importantly, the survival of the MrgprD-expressing neurons is in turn dependent on their association with LC. Long-term ablation of LC resulted in loss of MrgprD-expressing free nerve endings in the epidermis, reduced neuronal release of glutamate and hyperresponsive dermal MC. Thus, MrgprD-expressing neurons link LC in the epidermis with the state of dermal MC responsiveness. This three-way cellular cross-talk has important implications for neuronal control of mast cell driven inflammation in the context of protective as well as pathogenic immune responses. Furthermore, it reveals a hitherto unappreciated mechanism by which Langerhans cells maintain cutaneous homeostasis via MrgprD-expressing neuron suppression of MC.

It is likely that MrgprD-expressing neurons require a LC-derived growth factor and retract their nerve endings in its absence. We speculate that the loss of epidermal free nerve endings could potentially deprive MrgprD-expressing neurons of a key epidermal-derived factor(s), possibly β-ala or other potential MrgprD ligands, required to maintain optimal glutamate release in the dermis. Using a related LC-depletion method (LangerinDTR mice), Doss et al. reported reduced epidermal nerve density of CGRP-expressing neurons in conjunction with reduced expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF, a GRFα2 ligand) and nerve growth factor (NGF, a GFRα3 ligand)(Doss and Smith, 2014). Since MrgprD-expressing neurons are dependent on GFRα2 ligands, we favor a model in which LC ablation either directly or indirectly reduces levels of epidermal GDNF required to maintain MrgprD-expressing epidermal nerve endings. We did not observe any reduction in CGRP-expressing neurons possibly due to the analysis of different skin sites (i.e. flank vs. footpad) or minor differences between LangerinDTR and LCDTA mice (Kaplan et al., 2008). MrgprD-expressing free nerve endings in the epidermis were reduced by the long-term but not short-term ablation of LC. Neurite retraction may be a gradual process thereby explaining why only long-term but not short-term ablation of LC results in MC hyperresponsiveness.

We have identified glutamate as a key neurotransmitter that is secreted by MrgprD-expressing neurons to directly modulate the transcriptional programming and functional responsiveness of MC in a variety of inflammatory contexts. Importantly, we consistently observed dermal MC hyperreactivity using a diverse set of perturbations in which glutamate released from MrgprD-expressing neurons was either eliminated, reduced or blocked in vivo: mice lacking MrgprD-expressing neurons (MrgprdDTR), long-term LC-deficient mice (LCDTA) with reduced MrgprD-expressing epidermal free nerve endings, MrgprdΔvGlut2/+ mice with loss of a single allele of the vesicular glutamate transporter 2, and i.d. administration of KA2/GluR6 glutamate receptor inhibitor (NS102) in WT mice. In contrast, activation of MrgprD-expressing neurons with β-ala resulted in increased glutamate release and MC hyporesponsiveness. Notably, inhibition of glutamate sensing by cultured MC or its restoration resulted in reciprocal programming of a module of MC genes that regulated mast cell activation and their inflammatory functions.

The module of MC genes regulated across all in vivo and in vitro perturbations includes Mrgprb2, a member of a Mas-related family of G-protein-coupled receptors expressed primarily by MC. MrgprB2 functions as an activating receptor for non-IgE mediated mast cell degranulation in response to multiple exogenous and endogenous ligands including the neuropeptide SP (Galli and Tsai, 2012; Green et al., 2019; McNeil et al., 2015; Serhan et al., 2019; Subramanian et al., 2011). This is consistent with our findings that FcεRI activation in the passive cutaneous anaphylaxis model was unaffected when MC MrgprB2 expression was altered. In contrast, in multiple in vivo models that involve MrgprB2 (e.g. irritant dermatitis, compound 48/80 administration, CHS, host defense to dermonecrotic S. aureus infection, LL-37 induced rosacea), the extent of the inflammatory response correlated with expression of Mrgprb2. Thus, it is likely that MrgpB2 expression levels determine, at least in part, the extent of MC degranulation in these models. In addition to Mrgprb2, we noted altered expression of several other Mrgpr-family members, as well as genes that encode MC granule proteases and other MC effector proteins. Thus, glutamate signaling modulates a MC transcriptional program encompassing a set of MC receptors and effector proteins that may be functionally specialized for IgE-independent MC activation. We propose that it represents a distinctive MC-extrinsic mechanism that “tunes” MC responsiveness to select stimuli (Galli et al., 2008).

The mechanisms by which LC promote immunostimulatory or immunosuppressive responses have been controversial for many years (Kaplan, 2017). Much experimental effort has focused on the capacity of LC to function as antigen-presenting cells and prime effector or regulatory T cell responses. That LC are required to maintain epidermal innervation which in turn modulates MC responsiveness provides a new function for LC and a new perspective on this question. The observation that exaggerated CHS in LCDTA mice is phenocopied in MrgprdDTR mice and that β-ala can suppress CHS argues that heightened MC activation in the absence of LC can account for many of the immunosuppressive functions attributed to LC. The same mechanism of heightened MC degranulation and concomitant local inflammation in the absence of LC may explain why male skin from LCDTA but not WT mice transplanted onto female WT mice is rejected (Obhrai et al., 2008). Notably, maintaining tissue architecture and homeostasis is a function more closely associated with tissue macrophages than with DC. Thus, in this context, LC appear to be functioning akin to tissue macrophages with which they share a common ontogeny (Ginhoux et al., 2006; Hoeffel et al., 2012).

A growing body of literature argues that the MrgprB2 human ortholog, MrgprX2, likely participates in the pathogenesis of multiple human skin diseases (Subramanian et al., 2016). Thus, our observation that β-ala agonism of MrgprD-expressing neurons suppressed MC expression of Mrgprb2 and multiple effector molecules suggests this as a potential novel therapeutic approach for human skin diseases. Although a comprehensive analysis of human peripheral sensory afferent subsets has not been reported, it is likely that MrgprD-expressing neurons project to human skin since it has been reported that oral ingestion of β-ala as a dietary supplement can promote cutaneous tingling sensations (Liu et al., 2012). Alternatively, agonism of the KA2/GluR6 glutamate receptor on MC could potentially also provide a similar beneficial therapeutic effect.

In summary, we have described a pathway in which epidermal nonpeptidergic MrgprD-expressing neurons actively inhibit MC hyperresponsiveness via glutamate-induced transcriptional reprogramming. Thus, MrgprD-expressing sensory neurons have an important immuno-regulatory function and maintain cutaneous immune homeostasis. We have focused exclusively on MrgprD-expressing neurons in the skin at steady-state. Release of glutamate from MrgprD-expressing neurons could be modulated by physical epidermal disruption, composition of the cutaneous microbiome or infection thereby providing a mechanism for integration of epidermal and dermal inflammatory responses by afferent neurons. Notably, MrgprD-expressing neurons are also found in other tissues and may function similarly to those in the skin (Bautzova et al., 2018). These questions as well as potential translational application of these findings represent exciting directions for future research.

Limitations of Study

This study describes a pathway in which epidermal nonpeptidergic MrgprD-expressing neurons actively inhibit MC hyperresponsiveness via glutamate-induced transcriptional reprogramming under steady-state conditions. Additional work will be required to determine whether this system can alter MC reactivity during perturbations such as infection, inflammation, or wound healing. We also do not know how the absence of LC results in reduced glutamine release from MrgprD-expressing neurons. We have speculated this may result from reduced access to epidermal-derived β-ala in LC-deficient mice, but there are several other possibilities that could potentially explain this phenomenon. In addition, we have identified KA2 and GluR6 as likely glutamate receptors on MC by expression of mRNA transcripts. Expression of these proteins by MC and whether they signal as homo-or heterodimers have not been determined. Finally, agonism of MrgprD or KA2/GluR6 represents an attractive therapeutic approach to suppress MC responses in disease states. Testing these approaches in preclinical disease models and in patients remains unexplored.

STAR ★ Methods

Resource availability

Lead contact

For information and requests for resources and reagents, please contact Daniel H. Kaplan (dankaplan@pitt.edu)

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

The GEO accession numbers for the RNA-seq datasets reported in this paper are 143569 and 165295.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Research animals

C57BL/6, Tac1−/− vGlut2flox, ROSA26-tdTomato and ROSA26-iDTR mice were obtained from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mcpt5-Cre+ Rosa26 DTA (referred to MCDTA) mice were generously provided by Axel Roers (University of Technology Dresden, Dresden). Mrgprb2−/− mice were kindly provided by Benjamin McNeil (Northwestern University, Chicago). Mrgpra3cre mice were generously provided by Xinzhong Dong (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore). Human Langerin-DTA (referred to LCDTA), Human Langerin-DTR (referred to LCDTR), Itgb6−/−/Itgb8ΔKC and Mrgprdcre ROSA26-tdTomato (referred to MrgprdTdT) mice have been previously described (Bobr et al., 2010; Kaplan et al., 2005; Mohammed et al., 2016; Rau et al., 2009). Mrgprdcre and Mrgpracre mice were crossed with ROSA26iDTR mice to obtain MrgprdDTR and Mrgpra3DTR mice, respectively. We crossed LCDTA mice with MCDTA mice to obtain LCDTAxMCDTA mice. We generated MrgprdTdT mice with LCDTA mice to obtain MrgprdTdTxLCDTA mice. Mrgprdcre mice were bred with vGlut2flox mice to obtain MrgprdΔvGlut2/+ mice. Experiments were performed on independent cohorts of male and female mice between the ages of 6-10 weeks. All mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions and all animal experiments were approved by University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

METHODS DETAILS

Administration of diphtheria toxin (DT)

To deplete Langerhans cells (LC), LCDTR mice were given 1 μg DT (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) in 100 μl PBS by intraperitoneal injection for short-term depletion of LC. For long-term depletion, LCDTR mice were given 100 ng DT after initial injection every 10 days. For denervation of MrgprD or MrgprA3 neurons, DT treatment was modified as previously described (Han et al., 2013; Pogorzala et al., 2013). Four-week old MrgprdDTR or Mrgpra3DTR mice were given 300 ng DT twice a week for 3-4 weeks. Littermate control mice were treated on the same schedule with intraperitoneal injections of 100 μl PBS.

Contact dermatitis model

For irritant dermatitis model, mice were directly challenged with 20 μl to both sides of one ear with 1% croton oil in acetone: olive oil (4:1). Ears were measured with a micrometer (Mitutoyo) at the respective time points before and after challenge and data are expressed as the ear size at the respective time points minus the baseline thickness. The whole ear was fixed in 4% PFA and processed for H&E and toluidine blue staining as described (Cohen et al., 2019; Dudeck et al., 2015). For the contact hypersensitivity model, mice were sensitized on day 0 by epicutaneous application of 25 μl of 0.25% DNFB (1-Fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene, Sigma) in acetone: olive oil (4:1) or vehicle alone onto dry shaven abdominal skin. On day 5, baseline ear thickness was measured with a micrometer followed by challenge with 10 μl of 0.2% DNFB to both sides of one ear. Ear thickness was measured at the respective time points.

Immunofluorescent microscopy

For epidermal sheets, dorsal and ventral halves of the ear were separated and pressed epidermis side down onto double sided adhesive (3M, St. Paul MN). Slides were incubated in 10 mM EDTA in PBS for 45 min, allowing physical removal of the dermis, before being washed twice in PBS and fixed 60 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) before immunolabeling (Kaplan et al., 2005). For sectioned tissue, ear or flank skin was embedded in O.C.T compound at −80°C. The frozen tissue was cut at 8 μM and mounted onto Superfrost plus slides. Slides were fixed in 4% PFA before immunolabeling. Tissues were mounted with Vecta shield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Primary antibodies used included: goat anti-CGRP (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), goat anti-GFRα2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MI), goat anti-GFRα3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MI), rabbit anti-PGP9.5 (Ultraclone Ltd., Yarmouth, Isle of Wight). Secondary antibodies used were: Alexa555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Alexa568-conjugated donkey anti-goat (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Antibodies were diluted in antibody diluting buffer (1% BSA, 0.1% Tween20, 0.1% NaN3 in PBS). For whole mount tissue, ears were cut into small pieces and fixed in 4% PFA for 2-3 hours then washed in 0.2% PBST for 5-7 hours. Tissue was labeled with FITC conjugated Avidin (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride (DAPI) (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) in a solution containing 20% DMSO, and 5% goat serum for 3-5 days at room temperature. After washing, tissues were mounted with Vecta shield without DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were captured using an Olympus fluorescent microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Olympus FluoView confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

RNAseq

Total mRNA from whole ears, sorted dermal mast cells or cultured peritoneal-derived mast cells were prepared using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit (Hilden, Germany). The mRNA libraries were generated using Illumina Truseq Stranded mRNA Library Prep kit, followed by 75bp single indexed sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq500 to obtain 40-50 million reads per sample. Reads were mapped to the mm9 mouse genome with STAR aligner (Dobin et al., 2013). Gene expression values (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads; FPKM) were calculated using Cufflinks (Dobin et al., 2013; Trapnell et al., 2010). Differentially expressed genes were determined using cuffdiff function. FPKM matrix of log2 transformed values were imported in R (R version 3.5.2)(R Development Core Team, 2018) to enable the analysis of gene modules that manifested coherent dynamics across the three perturbations. For this analysis, all genes with a non-zero value in at least one replicate in a given experiment were selected, and then each sample was z-scored for all such expression values. In a second step, the gene values were z-scored across all samples representing a given perturbation. The resulting expression matrices spanning the 3 perturbations were then merged. Next genes were hierarchically clustered using the Ward’s method, and the hierarchical tree was cut to generate 6 clusters. The mean expression value for all genes within a cluster was used to generate a mean cluster profile. These mean cluster values were used to partition genes in the original matrix into modules based on their maximum correlation values. The resulting six modules (M1-M6) were tested for conditional gene ontology enrichment using the GOstats package (Falcon and Gentleman, 2007) as described previously(Chaudhri et al., 2020). Only GO terms with odds ratio >4 and a p-value < 1.0E-5 were considered for further analysis. Heatmaps were generated using package made4(Culhane et al., 2005). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using The Broad Institute pipeline (www.broad.mit.edu/gsea).

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were obtained as previously described (Kashem et al., 2015). The skin was minced finely with scissors and resuspended in RPMI1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) with 2.5 mg/mL collagenase XI (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.25 mg/mL hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 mg/mL DNase (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.01 M HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10% FBS followed by incubation in a shaking incubator for 1 h at 37°C at 250 rpm. The resulting cells were filtered through a 40 mm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). After doublet and live/dead (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) exclusion, mast cells (MC) were gated as follows: CD45+ CD11b− CD11c− CD19− F4/80− CD4− CD8− FcεRI+ CD117+. Samples were analyzed on LSRFortessa flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used include CD117 (ACK2), CD107a (1D4B) and CD19 (1D3) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and FcεRIα (Mar-1), CD45.2 (104), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), CD4(RM4-5), CD8a (53-6.7), I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), CD3ε (17A2) and F4/80 (BM8) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). For extracellular staining, antibodies were diluted in staining media (3% Calf Serum, 5mM EDTA, 0.04% Azide).

Culture and activation of peritoneal-derived mast cells

Peritoneal cells from C57BL/6 female mice were cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 20 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM Sodium pyruvate (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 1x Non-essential amino acids (Corning), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 ¼g/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 4 mM L-glutamine (Corning), and 25 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-3 and 15 ng/ml stem cell factor (Peprotech). The cells were maintained at a concentration of 0.5-1×106 cells/ml with weekly changes of the medium. After 3-week culturing, the cell population purity was analyzed by flow cytometry and further used for experiment. The cells were then cultured in regular RPMI1640 medium with or without NS102, or washed and cultured in glutamate-free Tyrode’s buffer (Sigma) adding different concentration of glutamate. The cells were then harvested and stimulated with 10 ¼g/ml compound 48/80 for 40 min at 37°C and β-hexosaminidase (β-hex) released into the supernatant was detected as previously described (Malbec et al., 2007). The OD was read at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer. The percentage of β-hex release was calculated by the following formula: (supernatant β-hex) × 100/(lysate β-hex + supernatant β-hex). To detect PCMC degranulation by flow cytometry, after doublet and live/dead exclusion, degranulated PCMC were gated as follows: CD45+ FcεRI+ CD117+ CD107a+ Avidin+.

Neuron cultures

Lumbar and thoracic DRGs were pooled, dissociated and cultured for qPCR, glutamate, substance P and CGRP release assays. Dissection and culture were performed as previously described (Malin et al., 2007). In brief, following euthanasia and perfusion with ice cold Ca2+/Mg2+-free HBSS, isolated ganglia were placed into cold HBSS. DRGs were transferred to 3mL of filter-sterilized 60U papain/ 1mg L-cys/HBSS buffered with NaHCO3 at 37°C for 10 minutes, then to filter sterilized collagenase II (4 mg/mL)/dispase II (4.67 mg/mL) in HBSS for 20 minutes at 37°C. Enzymes were neutralized in Advanced DMEM/F12 media (Thermo Fisher, Pittsburgh PA) with 10% FBS (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Neurons were dissociated in media with trituration through a series of fire-polished glass pipettes. Cells were plated in Advanced DMEM/F12 (as above) supplemented with 10 ng/mL NGF 2.5S (ThermoFisher, Pittsburgh, PA) in 24 well plates for all assays. Cells for neurotransmitter release assays were plated at the following concentrations: CGRP: 20,000 cells/well, Substance P: 60,000 cells/well, glutamate: 40,000 cells/well. For RNA extractions, dissociated neurons from a single mouse were split 1:1 (approximately 60k neurons/well) and plated in media with or without 2mM β-alanine. Media was refreshed the next morning and cells harvested after 24 hours in culture. Cultured cells were plated 1-2x overnight prior to stimulation for neurotransmitter release assays.

Neurotransmitter release assay

Neuropeptide release assays were performed as previously described with slight modifications (Kashem et al., 2015). After about 40 hours in culture, neurons were washed with 1×HBSS (with Ca2+/Mg2+ - Gibco, Grand Island, NY) for 5 minutes and then incubated in 1×HBSS for 10 minutes to measure basal release. Cells were stimulated with 100nM Capsaicin in 1×HBSS for 10 minutes and the supernatant collected prior to lysing the cells in lysis buffer (20mM Tris, 100mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.5% Tx). CGRP and Substance P in the supernatant was measured using the CGRP EIA kit and Substance P Elisa Kit respectively (both: Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) as per the manufacturer’s instructions using Gen5 1.10 software and a BioTek Epoch microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

For glutamate release neurons were plated in media (as above) with or without 2 mM β-alanine. Media was refreshed daily. Two hours prior to stimulation fresh media was supplemented with 100 μM DL-threo-β-Benzyloxyaspartic acid (TBOA, Tocris, Minneapolis, MN), a blocker of excitatory amino acid transporters. To remove glutamate-containing culture media, neuron cultures were washed 3× with 1×HBSS (with Ca2+/Mg2+) for 5 minutes. Cultures were incubated in 1×HBSS (controls) or stimulated with 100 ¼M Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 1×HBSS for 10 minutes, and the supernatant collected prior to lysing the cells. The concentration of glutamate released by stimulation and the total lysed content of glutamate in neuron cultures was determined using the glutamate glo assay (Promega, Madison WI) and measured with SOFTmax Pro for Lmax 1.1 software and a Lmax Microplate Luminometer or SpectraMax iD5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA).

Q-PCR

To extract whole tissue RNA, ears or flank skins were homogenized using a homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and processed using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To extract mRNA from sorted skin mast cells (MC) or dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cultures, MC were directly sorted into lysis buffer and DRG cultures were collected and processed using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Micro Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole L1-L5 DRGs were dissociated using Rino Pink Lysis tubes and Bullet Blender (Next Advance, Troy, NY) then processed using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA to cDNA conversion was performed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was analyzed using TaqMan Gene Expression assays. CT values are normalized to either Gapdh/Hprt expression and are shown as relative fold change (2−ΔΔCt).

Evans blue extravasation

Evans blue extravasations were carried out as previously described (Klemm et al., 2006; McNeil et al., 2015). Mice were shaved on the flank and chemically depilated with Nair hair remover (Church & Dwight, Princeton, NJ). The shaved mice were allowed to rest for two days and then anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (100/20 mg/kg body weight). Fifteen minutes after induction of anesthesia, mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with 50 μl of 12.5 mg/ml Evans blue (Sigma) in sterile saline. Five minutes later, 10 μg/ml compound 48/80 or vehicle was i.d. injected into flank (20 μl). Twenty minutes later, the photos were taken and tissues were collected. For croton oil mediated Evans blue extravasation, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and i.v. injected with Evans blue, followed by painting 20 μl 10% croton oil on the shaved flank skin, tissues were harvest after thirty minutes. For IgE mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis, mice ear skin was sensitized with i.d. injection of anti-dinitrophenyl (anti-DNP) IgE (20 ng/20 μl) for 24 h. A mixture of 100 μg DNP-HSA and Evans blue was i.v. injected and thirty minutes later, the ears were collected to measure pigmentation. Tissues were weighed and Evans blue was extracted by incubation in formamide overnight at 37 °C, and the OD was read at 650 nm using a spectrophotometer. For studies using beta-alanine (β-ala) or NS102, mice were i.d. injected with 50 mM β-ala (once daily), 50 μM NS102 (twice daily) or vehicle on the flank for two consecutive days and then challenged with the indicated reagents on the same area.

S. aureus infection model

Mice were anesthetized and shaved on the flank as above. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus strain USA300 was grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) media and thoroughly washed in sterile PBS. In a volume of 20 μl, 107 S. aureus was i.d. injected into the flank. To evaluate bacterial burden, skin was harvested 10 days post-infection, homogenized and diluted onto TSB plates supplemented with ampicillin, and incubated at 37°C for 24-48 hours for quantification of colony forming units. For studies using β-ala, 50 mM β-ala was i.d. injected in shaved flank daily for two days before infection and injected daily for 9 consecutive days post infection.

MC903 model

MC903 treatment was performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2013). Briefly, mice were treated once daily with topical application of 2 nmol of MC903 (calcipotriol, Tocris Bioscience) in 20 μl of ethanol (vehicle) on both ears. Ears were measured with a micrometer (Mitutoyo) at the respective time points before and after challenge and data are expressed as the ear size at the respective time points minus the baseline thickness.

Rosacea model

The skin rosacea model was performed as previously described (Choi et al., 2019). Briefly, shaved skin was intradermally injected with 50 μl 320 mM cathelicidin LL-37 (AnaSpec Inc, Fremont, CA) twice a day for 2 days. PBS or β-ala (50 mM) was injected with LL-37 once daily. The area of cutaneous erythema was calculated. Skin biopsies were taken after 72 h of observation, and tissues were immersed immediately into RNAlater stabilization reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and stored at −80 °C.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Intra-epidermal nerve fibers quantification

Quantification of Intra-epidermal nerve fibers (IEFN) with antibodies against Pgp9.5, GFRα2, GFRα3 and CGRP were determined from cross sections of two distinct areas of single tissue sections and pooled from 4-5 mice. Scoring was performed blind. Data is represented as the counted number of nerve fibers which cross the basement membrane.

Mast cells quantification

Quantification of mast cells (MC) with avidin or toluidine blue staining was determined from cross sections of 2-3 distinct areas from a single tissue section and areas pooled from 3-4 mice. ImageJ imaging software was used to quantify MC number. Data is represented as the counted MC number or percentage of degranulated MC.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Data is represented as mean ± standard error (SEM). Studen’s t test and one-way ANOVA was used to compare corresponding groups as indicated.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Long-term LC ablation increases mast cell Mrgprb2-mediated irritant dermatitis, related to Figure 1.

(A) Flow cytometry of epidermal single cell suspensions isolated from LCDTR mice treated with DT for 3 or 30 days compared with a DT treated WT control. Representative flow plots gated on CD45 are shown. LC are gated as MHC-IIhi, CD3lo. (B) FPKM for CD207 (Langerin) from the indicated RNAseq samples is shown. (C) Normalized gene expression values of top differentially expressed genes (DEGs, p<0.05) between LCDTA vs LCDTR (see also Table 1) with indicated immune cell types from ImmGen database. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of DEGs with a p<0.05 in LCDTA vs LCDTR was performed on the sorted skin MC specific gene set (Dwyer et al., 2016). Normalized enrichment scores (NES) and P values are indicated. (D) Percentage of dermal CD45+ cells in the ears of WT and LCDTA mice detected by flow cytometry after challenged with vehicle or croton oil at 6 hours. (E) Representative flow cytometry plots on ear epidermal LC (CD45+MHCII+CD3−) and dermal MC (CD45+CD11b-CD11c-CD4-CD8-CD19-F4/80-CD117+FcεRIα+) between WT, MCDTA and MCDTA x LCDTA naive mice. (F) Representative images of dorsal skin transverse sections stained with avidin to label granules MC and identify undegranulated MC (red) collected at 30 min after i.d. injection of compound 48/80 or vehicle. (A-C) Results are from a single RNAseq experiment with cohort size of n=3-4. (D, E, F) Results are represented as mean ± SEM from 2-3 independent experiments with cohorts of n=3-4. Each symbol represents data from an individual animal. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (D). n.s, no significant difference. Scale bars in F represent 20 μm.

Figure S2. Epidermal MrgprD-expressing nerve endings are reduced by long-term LC ablation, related to Figure 2.

(A) Representative immunofluorescent image from transverse skin sections stained with PGP 9.5 from LCDTA and littermate (WT) controls, LCDTR mice treated with DT for 3 days or 30 days. (B) Representative image of epidermal whole-mount from WT and LCDTA mice ears stained with GFRα2 (top) or GFRα3 (bottom). (C) Representative transverse skin sections stained with GFRα2 from WT and LCDTA mice. (D) Quantitative analysis of IENF from transverse section stained with anti-CGRP from WT and LCDTA mice. (E) Flow cytometric quantification of MC numbers in ear skin of DT treated WT or MrgprdDTR mice. (F) Effects on IgE-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis on MrgprdDTR mice. Ears collected 30 minutes after FcεRI cross-linking to quantify dye extravasation. Arrows heads indicated intra-epidermal nerve fiber (IENF). Scale bars represent 20μm in A, B; 10 μm in C. Results are represented from 2-3 individual experiments with cohorts of n=3-4.

Figure S3. Long-term LC ablation augments S. aureus host defense, related to Figure 3.

(A) Representative images of skin lesions from WT, LCDTA, 3-day DT-treated LCDTR and MCDTA mice on indicated days after i.d. inoculation with 107 S. aureus. Results are represented from two independent experiments.

Figure S4. MrgprD agonism suppresses MC activation, related to Figure 4.

(A) Quantification of Evans blue dye extravasation following passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in WT mice following pretreatment with vehicle or 50mM i.d. β-ala for 2 days. (B) Quantification of MC numbers in ear skin of WT mice by flow cytometry following pretreatment with vehicle or 50mM i.d. β-ala for 2 days. (C) Scratching bouts monitored over 30 minutes following 20 μl i.d. injection of vehicle, 50 mM β-ala and 1 μg compound 48/80 into the nape of WT mice. (D) Representative images of skin lesions following i.d. inoculation of 107 S. aureus in WT mice. Mice were pretreated at the site of inoculation with i.d. PBS or 50mM β-ala for 2 days prior infection with S. aureus that continued over the course of the experiment. (E) mRNA expression of rosacea biomarkers (Klk5, Cma1, Mmp9) as assessed by RTqPCR of whole skin from LL-37 treated skin pretreated with vehicle or 50 mM i.d. β-ala for 2 days. (A, B, C, E) Each symbol represents data from an individual animal. Results are represented as mean ± SEM from two individual experiments with cohorts of n=4-5. Significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test, **p < 0.01.

Figure S5. A coherent MC gene expression program that is reciprocally modulated by perturbations of MrgprD-expressing neurons, related to Figure 5.

(A) Heatmap displaying log2 (FPKM+1) values of all M4 module genes (n=3,172) across replicates and the indicated in vivo perturbations. One-way hierarchical clustering of gene transcript values across the various samples was used to generate heatmap. Biologically important mast cell genes are annotated. (B) Heatmap displaying differentially expressed mast cells genes (DEGs) revealed by pairwise comparison of RNAseq datasets from the three indicated perturbations. All genes are contained within the M4 gene module.

Figure S6. TRPV1-expressing neurons are not affected in LCDTA or MrgprdDTR mice, related to Figure 6.

(A) mRNA expression of indicated genes in L1-5 dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells of WT, LCDTA or DT treated MrgprdDTR mice analyzed by RTqPCR. (B) Release of CGRP and Substance P from capsaicin stimulated cultured DRG cells isolated from PBS or DT treated MrgprdDTR mice. Each symbol represents data from an individual animal. Results are represented as mean ± SEM from two individual experiments. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA (A) and unpaired Student’s t test (B). ***p < 0.001; n.s, no significant difference.

Figure S7. MrgprD-expressing neurons suppress mast cells via glutamate release, related to Figure 7.