Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an established risk factor for lung cancer, remains largely undiagnosed and untreated before lung cancer surgery. We evaluated the effect of perioperative bronchodilator therapy on lung function changes in COPD patients who underwent surgery for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). From a database including NSCLC patients undergoing lung resection, COPD patients were identified and divided into two groups based on the use of bronchodilator during the pre- and post-operative period. Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and postoperative complications were compared between patients treated with and without bronchodilators. Among 268 COPD patients, 112 (41.8%) received perioperative bronchodilator, and 75% (84/112) were newly diagnosed with COPD before surgery. Declines in FEV1 after surgery were alleviated by perioperative bronchodilator even after adjustments for related confounding factors including surgical extent, surgical approach and preoperative FEV1 (adjusted mean difference in FEV1 decline [95% CI] between perioperative bronchodilator group and no perioperative bronchodilator group; − 161.1 mL [− 240.2, − 82.0], − 179.2 mL [− 252.1, − 106.3], − 128.8 mL [− 193.2, − 64.4] at 1, 4, and 12 months after surgery, respectively). Prevalence of postoperative complications was similar between two groups. Perioperative bronchodilator therapy was effective to preserve lung function, after surgery for NSCLC in COPD patients. An active diagnosis and treatment of COPD are required for surgical candidates of NSCLC.

Subject terms: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Non-small-cell lung cancer, Surgical oncology

Introduction

Lung cancer is by far the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide1. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an independent risk factor for lung cancer development and the most frequent concomitant disease in patients with early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)2,3. Although surgical resection remains as the cornerstone of curative treatment in early stage NSCLC4, patients with COPD are often precluded from lung cancer surgery due to inevitable deteriorations in pulmonary function and the increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications (PPC) and poor outcome following lung resection5–7.

COPD frequently remains under-recognized in both the general population and patients diagnosed with NSCLC8–10. In one earlier study, 50.2% of all patients with NSCLC had COPD, while only 7.2% were aware of the disease before their diagnosis of lung cancer10. Failure to detect COPD in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer indicates that these patients have not been treated for COPD and can result in inadequate management as these patients will not benefit from bronchodilator treatments.

Bronchodilators, which significantly improve respiratory symptoms and lung function, are the mainstay of the management of stable COPD11,12. A couple of studies have shown that preoperative treatment with bronchodilators significantly increased predicted postoperative pulmonary functions in untreated COPD patients with lung cancer, and some of the patients were eventually able to undergo surgical resection13–15. Another study in 20 patients with COPD showed that bronchodilator therapy with tiotropium and salmeterol improved lung function and quality of life at 1 year after surgical resection, compared to a control group16. However, these previous studies evaluated fewer than 50 patients. In addition, the recently introduced once-daily dual long-acting bronchodilators, which show greater efficacy to improve lung function17, were not adequately evaluated in those studies.

We thus studied the effect of perioperative bronchodilator therapy on postoperative lung function during short-term and long-term periods in patients with COPD who underwent surgical resection for NSCLC. We further compared the development of PPCs between patients who were not treated with bronchodilator and those who were treated with bronchodilator.

Results

The mean (SD) age of study participants was 66.7 (7.3) years, and the prevalence of perioperative bronchodilator therapy was 41.8% (N = 112); 75% of patients (84/112) were newly diagnosed with COPD and had begun bronchodilator therapy ahead of their lung cancer surgery. Compared to participants who were treated without a bronchodilator perioperatively, those treated with perioperative bronchodilators were more likely to be older (65.8 vs. 68.1, P = 0.01), to have squamous cell carcinomas (33.3% vs. 46.4%, P < 0.01), and to have lower forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (2,077 mL vs. 1,851 mL, P < 0.01) and % pred FEV1 (68.0% vs. 63.2%, P < 0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of all study participants according to perioperative bronchodilator use.

| Overall | Perioperative Bronchodilator | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 268) | No (N = 156) | Yes (N = 112)* | P value | |

| Age (years) | 66.7 (7.3) | 65.8 (7.3) | 68.1 (7.0) | 0.01 |

| Sex | 0.92 | |||

| Female | 39 (14.6) | 23 (14.7) | 16 (14.3) | |

| Male | 229 (85.4) | 133 (85.3) | 96 (85.7) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.97 | |||

| Underweight | 8 (3.0) | 5 (3.2) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Normal | 87 (32.5) | 52 (33.3) | 35 (31.3) | |

| Overweight | 67 (25.0) | 39 (25.0) | 28 (25.0) | |

| Obese | 106 (39.6) | 60 (38.5) | 46 (41.1) | |

| Smoking status | 0.76 | |||

| Never | 32 (11.9) | 19 (12.2) | 13 (11.6) | |

| Current smoker | 115 (42.9) | 64 (41) | 51 (45.5) | |

| Ex-smoker | 121 (45.1) | 73 (46.8) | 48 (42.9) | |

| Pulmonary function test | ||||

| FVC (mL) | 3,429.5 (746.3) | 3,495.1 (745.4) | 3,338.1 (741.2) | 0.09 |

| FVC, % predicted | 82.6 (11.8) | 83.5 (11.8) | 81.4 (11.7) | 0.15 |

| FEV1 (mL) | 1,982.3 (503.1) | 2,076.6 (489.8) | 1,851.0 (494) | < 0.01 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 66 (11.1) | 68 (10.2) | 63.2 (11.7) | < 0.01 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 58 (8.4) | 59.6 (7.6) | 55.7 (9.0) | < 0.01 |

| DLco, % predicted | 78.0 (16.2) | 79.9 (15.4) | 75.4 (17.0) | 0.024 |

| Histology | < 0.01 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 146 (54.5) | 98 (62.8) | 48 (42.9) | |

| Squamous cell | 104 (38.8) | 52 (33.3) | 52 (46.4) | |

| Large cell | 9 (3.4) | 4 (2.6) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Others | 9 (3.4) | 2 (1.3) | 7 (6.3) | |

| Location | 0.10 | |||

| Right upper lobe | 76 (28.4) | 48 (30.8) | 28 (25.0) | |

| Right middle lobe | 11 (4.1) | 6 (3.8) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Right lower lobe | 49 (18.3) | 22 (14.1) | 27 (24.1) | |

| Left upper lobe | 87 (32.5) | 48 (30.8) | 39 (34.8) | |

| Left lower lobe | 45 (16.8) | 32 (20.5) | 13 (11.6) | |

| Type of surgery | 0.35 | |||

| Wedge resection/segmentectomy | 54 (20.1) | 27 (17.3) | 27 (24.1) | |

| Lobectomy | 194 (72.4) | 116 (74.4) | 78 (69.6) | |

| Bilobectomy/pneumonectomy | 20 (7.5) | 13 (8.3) | 7 (6.3) | |

| VATS | 163 (60.8) | 100 (64.1) | 63 (56.3) | 0.19 |

| Clinical stage | 0.17 | |||

| I | 157 (58.6) | 94 (60.3) | 63 (56.3) | |

| II | 69 (25.7) | 43 (27.6) | 26 (23.2) | |

| III | 42 (15.7) | 19 (12.2) | 23 (20.5) | |

| Adjuvant treatment | 63 (23.5) | 34 (21.8) | 29 (25.9) | 0.44 |

Values in the table represent means (standard deviation), or numbers (percent).

BMI body mass index, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1, FVC forced expiratory vital capacity, VATS video-assisted thoracic surgery.

*Among 112 patients who used a bronchodilator, 17 (15.2%), 19 (17.0%), 61 (54.5%), and 15 (13.4%) received LAMA, ICS/LABA, LAMA/LABA, and ICS/LAMA/LABA, respectively. There was no ICS monotherapy.

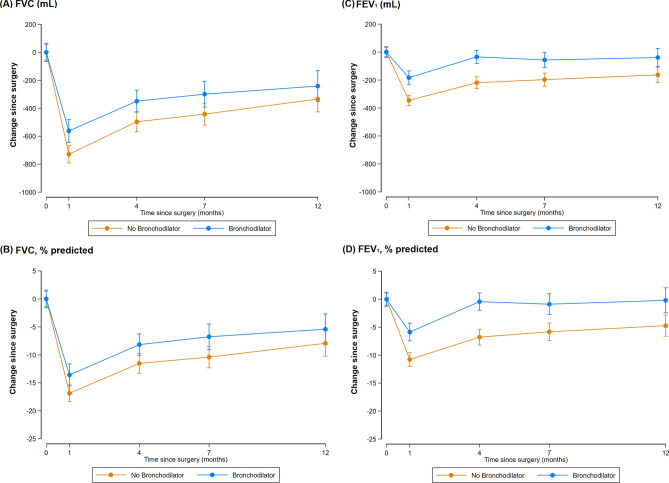

During the follow-up (the average duration of the follow-up was 10.7 months), a greater decline in FEV1 [95% confidence interval (CI)] was observed in patients not treated with perioperative bronchodilator compared with those who received perioperative bronchodilator at 1 month [− 161.1 mL (− 240.2, − 82.0); P < 0.001], 4 months [− 179.2 mL (− 252.1, − 106.3); P < 0.001], and 12 months [− 128.8 mL (− 193.2, − 64.4); P < 0.001] after surgery, respectively (Table 2). When we assessed % pred FEV1, participants treated without a perioperative bronchodilator showed larger decline of − 5.5% (− 8.0, − 2.9), − 6.1% (− 8.6, − 3.7), and − 4.6% (− 6.9, − 2.3) in % pred FEV1 (95% CI) at 1, 4, and 12 months after surgery, respectively than participants treated with perioperative bronchodilators (Table 2 and Fig. 1). When we conducted inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) of preoperative baseline FEV1, the results were similar (data not shown). In terms of forced vital capacity (FVC), patients treated without a perioperative bronchodilator showed greater decline in FVC (95% CI) than those treated with perioperative bronchodilators at 1 months [− 172.6 mL (− 295.1, − 50.1); P = 0.006], 4 months [− 128.8 mL (− 250, − 7.6); P = 0.037], and 12 months [− 105.4 mL (− 220, 9.1); P = 0.071] after surgery, respectively. While the patterns observed for FVC and % pred FVC were similar to those observed for FEV1, the differences between the groups treated with and without perioperative bronchodilators were reduced at 12 months after surgery.

Table 2.

Changes in pulmonary function from baseline to 1, 4, and 12 months following lung resection according to perioperative bronchodilator use.

| No perioperative bronchodilator (N = 156) | Perioperative bronchodilator (N = 112) | Decline in no perioperative bronchodilator group – Decline in perioperative bronchodilator group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference* between two groups | P values* | |||

| FVC (mL) | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 741.5 (− 816.5, − 666.5) | − 568.9 (− 665.8, − 472.1) | − 172.6 (− 295.1, − 50.1) | 0.006 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 485.6 (− 567.5, − 403.7) | − 356.8 (− 446.1, − 267.5) | − 128.8 (− 250.0, − 7.6) | 0.037 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 321.4 (− 394.9, − 248.0) | − 216 (− 303.8, − 128.1) | − 105.4 (− 220.0, 9.1) | 0.071 |

| FVC, % predicted | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 17.2 (− 19.1, − 15.4) | − 13.4 (− 15.8, − 11.0) | − 3.9 (− 6.9, − 0.9) | 0.012 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 11.3 (− 13.4, − 9.3) | − 8.4 (− 10.6, − 6.2) | − 2.9 (− 5.9, 0.1) | 0.054 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 7.6 (− 9.4, − 5.8) | − 4.8 (− 7.0, − 2.6) | − 2.8 (− 5.6, 0) | 0.053 |

| FEV1 (mL) | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 345.7 (− 394.0, − 297.5) | − 184.7 (− 247.4, − 122.0) | − 161.1 (− 240.2, − 82.0) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 219.9 (− 269.2, − 170.6) | − 40.7 (− 94.3, 13.0) | − 179.2 (− 252.1, − 106.3) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 154.5 (− 195.9, − 113.2) | − 25.7 (− 75.1, 23.7) | − 128.8 (− 193.2, − 64.4) | < 0.001 |

| FEV1, % predicted | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 10.9 (− 12.5, − 9.3) | − 5.5 (− 7.5, − 3.4) | − 5.5 (− 8.0, − 2.9) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 6.8 (− 8.4, − 5.1) | − 0.7 (− 2.5, 1.1) | − 6.1 (− 8.6, − 3.7) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 4.4 (− 5.9, − 2.9) | 0.2 (− 1.6, 2.0) | − 4.6 (− 6.9, − 2.3) | < 0.001 |

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (underweight, normal, overweight, or obese), smoking status (never, past, or current), surgical extent (limited resection, lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy), VATS, and preoperative baseline FEV1 (mL).

*Differences in pulmonary function changes between the “no perioperative bronchodilator” group and the “perioperative bronchodilator” group.

Figure 1.

Changes in pulmonary function from baseline to 1, 4, 7, and 12 months following lung resection according to perioperative bronchodilator use.

When we evaluated if the association between perioperative use of bronchodilator and the change in FEV1 at 4 months after surgery differed in pre-specified subgroups, the positive effects of perioperative bronchodilator use were consistent in all subgroups analyzed (all P-values for interaction > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the sensitivity analysis in patients with lobectomy (N = 194), those treated without a perioperative bronchodilator showed larger decline in FEV1 (95% CI) than those treated with perioperative bronchodilators at 1 month [− 163.0 mL (− 252.5, − 73.5); P < 0.001], 4 months [− 155.1 mL (− 241.1, − 68.9); P < 0.001], and 12 months [− 130.3 mL (− 206.7, − 53.8); P = 0.001] after surgery, respectively (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Among 112 patients who used a bronchodilator, 17 (15.2%), 19 (17.0%), 61 (54.5%), and 15 (13.4%) received long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA), LAMA/LABA, and ICS/LAMA/LABA, respectively. There was no ICS monotherapy. For subgroup analysis based on bronchodilator therapy, ICS was not regarded as a bronchodilator therapy. Thus, 36 (32.1%) including ICS/LABA were categorized into mono bronchodilator therapy with either LAMA or LABA, and 76 (67.9%) including ICS/LAMA/LABA were categorized into dual bronchodilator therapy with both LAMA and LABA. At 4 and 12 months, the dual bronchodilator group showed a trend towards less lung function decline compared with the two other groups (P for trend < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in pulmonary function from baseline to 1, 4, and 12 months following lung resection between mono and dual bronchodilators.

| No perioperative bronchodilator (N = 156) | Mono bronchodilator (N = 36) | Dual bronchodilator (N = 76) | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVC (mL) | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 741.5 (− 816.5, − 666.5) | − 554.3 (− 739.2, − 369.5) | − 568.6 (− 682.1, − 455.1) | 0.008 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 485.6 (− 567.5, − 403.7) | − 399.6 (− 551.2, − 247.9) | − 336.9 (− 447.1, − 226.6) | 0.031 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 321.4 (− 394.9, − 248.0) | − 281.7 (− 435.1, − 128.3) | − 184.1 (− 290.9, − 77.3) | 0.041 |

| FVC, % predicted | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 17.2 (− 19.1, − 15.4) | − 13.4 (− 17.9, − 8.8) | − 13.3 (− 16.1, − 10.5) | 0.014 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 11.3 (− 13.4, − 9.3) | − 8.9 (− 12.6, − 5.1) | − 8.2 (− 11, − 5.5) | 0.063 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 7.6 (− 9.4, − 5.8) | − 6.1 (− 9.9, − 2.3) | − 4.2 (− 6.8, − 1.5) | 0.036 |

| FEV1 (mL) | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 345.7 (− 394.0, − 297.5) | − 148.0 (− 268, − 28.0) | − 195.3 (− 268.7, − 122.0) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 219.9 (− 269.2, − 170.6) | − 50.1 (− 141.2, 41.0) | − 36.9 (− 103.4, 29.5) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 154.5 (− 195.9, − 113.2) | − 32.9 (− 119.3, 53.6) | − 22.5 (− 82.7, 37.7) | < 0.001 |

| FEV1, % predicted | ||||

| Change from baseline to 1 months after surgery | − 10.9 (− 12.5, − 9.3) | − 4.4 (− 8.3, − 0.5) | − 5.8 (− 8.2, − 3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 4 months after surgery | − 6.8 (− 8.4, − 5.1) | − 0.4 (− 3.5, 2.6) | − 0.9 (− 3.1, 1.4) | < 0.001 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months after surgery | − 4.4 (− 5.9, − 2.9) | 0.5 (− 2.6, 3.7) | 0.1 (− 2.1, 2.2) | < 0.001 |

ICS was not regarded as a bronchodilator therapy. Thus, 36 (32.1%) including ICS/LABA were categorized into mono bronchodilator therapy with either LAMA or LABA, and 76 (67.9%) including ICS/LAMA/LABA were categorized into dual bronchodilator therapy with both LAMA and LABA.

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (underweight, normal, overweight, or obese), smoking status (never, past, or current), surgical extent (limited resection, lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy), VATS, and preoperative baseline FEV1 (mL).

The frequency of overall PPC was 15.7% (n = 42), which did not differ by perioperative bronchodilator therapy (16.7% vs. 14.3%, P = 0.597). Among PPCs, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or pneumonia was the most frequent (n = 32), followed by bronchoscopic toileting (n = 8) and COPD acute exacerbation (n = 6). Postoperative cardiovascular complication (PCC) developed in 37 (13.8%) patients, of which atrial fibrillation (AF) (n = 35) was the most common. In multivariable analysis, there was no significant difference between two groups in terms of PPC and PCC risk (Table 4). In patients who received perioperative bronchodilators, 16 (14.2%) developed AF, while 19 (12.2%) of those treated without a perioperative bronchodilator developed AF (P = 0.064) (data not shown). Hospital length of stay, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, and readmission to ICU also did not differ between two groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Postoperative complications and hospital length of stay according to perioperative bronchodilator.

| No perioperative bronchodilator (N = 156) | Perioperative Bronchodilator (N = 112) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative pulmonary complication (PPC) | |||

| No. of patients (%) | 26 (16.7) | 16 (14.3) | 0.597 |

| Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.58 (0.27, 1.25) | 0.162 |

| Postoperative cardiovascular complication (PCC) | |||

| No. of patients (%) | 20 (12.8) | 17 (15.2) | 0.581 |

| Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.05 (0.49, 2.27) | 0.899 |

| PPC or PCC | |||

| No. of patients (%) | 37 (23.7) | 28 (25.0) | 0.809 |

| Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.86 (0.46, 1.60) | 0.632 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 8.6 (4.4) | 9.6 (6.0) | 0.120 |

| ICU length of stay, days | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.9) | 0.926 |

| ICU readmission during hospitalization for surgery, n (%) | 4 (2.6) | 5 (4.5) | 0.498 |

Values in the table are n (percent), mean (standard deviation) or adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

*Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (underweight, normal, overweight, or obese), smoking status (never, past, or current), surgical extent (limited resection, lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy), VATS, preoperative baseline FEV1 (mL) and DLco (% predicted).

Discussion

In this study in patients with COPD who underwent lung cancer surgery, we found that only 41.8% of patients were treated with bronchodilators during the perioperative period, and that most of these patients (75%) were diagnosed with COPD and started the bronchodilator therapy ahead of their lung cancer surgery. Importantly, our study demonstrates that declines in lung function following surgery, especially declines in FEV1, were alleviated by the use of perioperative bronchodilators at all time points, including 1, 4, and 12 months postoperatively. This finding persisted after the analyses were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, surgical extent, surgical approach and preoperative baseline FEV1. In addition, the positive effects of perioperative use of bronchodilator were consistent in all subgroups analyzed. To our knowledge, this is the largest study investigating the usefulness of perioperative bronchodilator therapy in patients with lung cancer with COPD.

COPD subliminally coexists with lung cancer. A previous study showed a prevalence of coexisting COPD in lung cancer of 50%, six times greater prevalence of COPD in newly diagnosed lung cancer cases than in an age-, sex-, and smoking-matched control group18. Another study also showed that COPD was present in 50.2% of smokers diagnosed with NSCLC, and most of the patients (92.8%) with COPD were unaware of the disease before their diagnosis of lung cancer10. In line with these findings, only 42% of the patients with COPD in our study were treated with bronchodilators during the perioperative period, and most patients began bronchodilator therapy with their COPD diagnosis during the preparation for the lung cancer surgery. These findings indicate that the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of COPD among patients with NSCLC remain common in the clinical practice.

Generally, our findings show that lung function dramatically dropped at 1 month after surgery, slowly recovered until postoperative month 4, and was stable by postoperative month 12. Our findings also show that the perioperative management of COPD using bronchodilators significantly mitigated the lung function decline from baseline, particularly the decline in FEV1, compared to patients who were not treated with perioperative bronchodilator. Numerically, the differences in FEV1 reductions from baseline between the two groups are greater than 100 mL, which corresponds to the minimal clinically important differences in FEV1 in COPD19. Furthermore, in some patients who began bronchodilator treatment just before surgical resection, FEV1 recovered after resection, up to the baseline FEV1 before the initiation of bronchodilator treatment, which was not observed in patients not treated with perioperative bronchodilator (Fig. 1). This significant alleviation of postoperative lung function decline may reduce symptom burden such as dyspnoea caused by lung resection. The detection and proper management of COPD is thus necessary during the preparation for surgical treatment in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer.

For some patients with severe bullous emphysema, lung resection (especially upper lobectomy) might have lung volume reduction effect20. In this regard, we evaluated the emphysema index (EI) in preoperative chest computed tomography (CT) scan of 120 patients who underwent upper lobectomy, using software (Synapse 3D Vincent, Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan). After excluding four patients with poor-quality image, EI was measured in 116 patients. The number of patients with EI of 5% or more, which is considered as a threshold for clinical importance21, was only 15 (13%), and it did not differ between groups with and without bronchodilator therapy (11.9% vs. 14.3%, P = 0.710). Thus, we think that the difference of lung function decline between two groups is unlikely due to a different effect from lung volume reduction.

Among the different bronchodilators, dual bronchodilators showed favourable outcomes in terms of mean changes in FEV1 from baseline, compared to mono bronchodilators that did not show statistically significant changes. The recently introduced dual once-daily bronchodilators have been shown to have greater efficacy for lung function improvement with comparable safety profiles over monocomponent17. Given the similar price range for dual and mono bronchodilators in South Korea, dual once-daily bronchodilators might offer more benefits for the preservation of lung function after surgical resection.

Poor pulmonary function is the major barrier for COPD patients to receive pulmonary resection due to the heightened risk of PPC, which is a major cause of postoperative morbidity and mortality5,22. Decline in lung volumes with atelectasis from the combined effects of supine position, general anesthesia, thoracic incision, and respiratory muscles or diaphragmatic dysfunction, results in the development of PPC23,24. In this study with COPD patients at least moderate degree of airflow limitation (FEV1 < 80% pred), the overall risk of PPC was 15.7%. Of note, PPC prevalence did not differ by perioperative bronchodilator therapy. However, compared to non-perioperative bronchodilator group, those in perioperative bronchodilator group were older and had lower baseline FEV1 and DLco, which are well known risk factors for PPC22,25. Thus, similar prevalence in PPC between two groups could be a signal of possible benefit of perioperative bronchodilator in preventing PPCs, which must be confirmed in future study.

There is potential cardiovascular safety concerns related to long-acting bronchodilator therapy, especially tachyarrhythmias occurring during the postoperative period26,27. In our study, 35 (13.1%) patients developed postoperative AF, with no difference according to perioperative bronchodilator use. In addition, we observed only one case of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the non-perioperative bronchodilator group.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, it was performed at a single tertiary hospital and represents a retrospective analysis. There could be unmeasured confounders that might have led to the prescription of bronchodilators. Also, we excluded patients who discontinued bronchodilator after surgery (N = 19) and those who started bronchodilator after surgery (N = 18). This per-protocol analysis is subject to confounding. Thus, future studies with prospective designs are required to validate our findings. Secondly, COPD was defined based on pre-bronchodilator pulmonary function tests, and we may have misclassified some patients28. Thus, we limited subjects to patients with FEV1 < 80% as well as FEV1/FVC < 70%, as these have a high probability of having COPD. Most patients in the non-bronchodilator group did not undergo post-bronchodilator spirometry, which reflects a real-world clinical setting. Given the benefit that bronchodilator therapy showed in our study, active screening for COPD including post-bronchodilator spirometry should be part of preoperative evaluations of patients with lung cancer. Thirdly, not all patients underwent repeated pulmonary function tests after the initiation of bronchodilator therapy before surgical resection. Thus, preoperative responsiveness to inhalers including dual long-acting bronchodilators could not be assessed. Instead, we used the results of baseline lung function tests that were obtained before the initiation of bronchodilator therapy in patients who just began the treatment. Considering that the majority of our patients with COPD newly began the bronchodilator treatment, we assumed that reduced postoperative lung function decline observed in the group treated with perioperative bronchodilators might be attributable to a significant increase in FEV1 before surgical resection, as a combined effect of newly prescribed bronchodilator treatment and smoking cessation, based on previous studies13,15. In addition, we did not have data on the compliance or inhaling techniques applied during bronchodilator therapy, but we assumed that compliance rates were good before surgical resection, leading to greater benefits. Finally, information regarding respiratory symptoms, quality of life, or physical activities was not uniformly available. We can therefore not be certain that the beneficial effect of bronchodilator use on postoperative lung functions is accompanied by improvements in the patients’ symptoms or quality of life. Indeed, no specific guideline for physical activity and rehabilitation prior to surgery are available at this time. Future studies therefore need to assess comprehensive care approaches including proper treatment of COPD as well as rehabilitation.

In conclusion, perioperative treatment with bronchodilators in patients with COPD shows benefits in the alleviation of the reduction in lung function, in particular FEV1, after pulmonary resection for NSCLC. An active diagnosis of COPD and treatment with bronchodilators are thus needed for patients with NSCLC scheduled to undergo surgical resection.

Methods

Study subjects

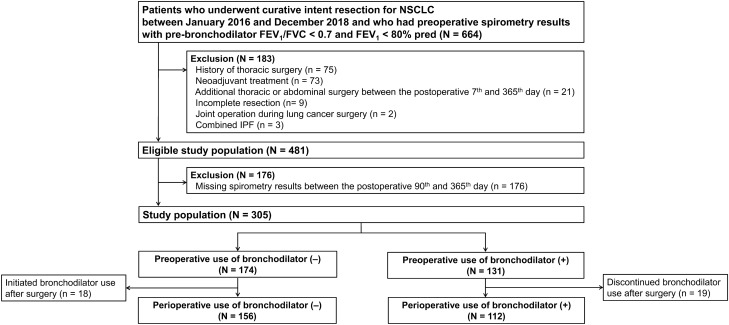

This was a retrospective cohort study in patients with NSCLC who underwent curative intent surgical resection at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea, between January 2016 and December 2018. Since our objective was to evaluate the effect of perioperative bronchodilator therapy and the lung function decline following surgery in NSCLC patients with COPD, we identified 664 subjects who had COPD (defined as pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.70 and FEV1 < 80% pred) at the time of their lung cancer diagnosis.

We excluded patients who had previously undergone thoracic surgery (n = 75), neoadjuvant treatment (n = 73), additional thoracic or abdominal surgery between the 7th and 365th postoperative day (n = 21), incomplete resection (n = 9), or joint operation during lung cancer surgery (n = 2), and those who had combined idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (n = 3). Of the eligible patients, 176 patients whose records did not contain spirometry test data acquired between the 90th and 365th postoperative day were excluded. We then also excluded patients who discontinued bronchodilator treatment after surgery (n = 19) and those who began bronchodilator treatment only after surgery (n = 18). The final sample consisted of 268 patients (229 men and 39 women, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart.

The Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center approved this study (IRB No. 2020-01-131-001) and waived the requirement for informed consent, as only de-identified data routinely collected during clinic visits were analysed. This study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations of our institutions.

Data collection

Demographics, clinical data, and treatment details were obtained from electronic medical records. Demographic information at diagnosis included age, sex, body mass index, and smoking status. Clinical information included pathologic stages, based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th Edition 29, histology (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and others), largest tumor size, and lobar location. Treatment information included extent of lung resection (limited resection, lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy), use of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), and adjuvant treatment.

Bronchodilator therapy

In this study, bronchodilator therapy was confined to LAMA, LABA, or LAMA/LABA with or without ICS. ICS administration was not counted as bronchodilator therapy. Perioperative use of a bronchodilator was defined as at least one prescription of aforementioned inhalers both (1) within 60 days prior to the surgery and (2) within 180 days after the surgery. Patients who underwent preoperative bronchodilator therapy were further categorised into a monotherapy (either LAMA or LABA) and a dual therapy (LAMA/LABA) group, irrespective of ICS use.

Pulmonary function tests

Preoperative spirometry was generally performed within 1 or 2 months prior to surgery, and postoperative spirometry was performed during follow-up, at around the 1st (0–2nd), 4th (3–5th), 7th (6–8th), and 12th (9–15th) months. All spirometry tests were performed in a pulmonary function lab, using a Vmax 22 system (SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA) according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society criteria30. Absolute FEV1 and FVC values were obtained and the percentages of predicted FEV1 and FVC were calculated using a reference equation obtained from a representative South Korean sample31. The diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide of the lung (DLco) was also routinely measured preoperatively, using the same apparatus, and absolute DLco values (mL/mmHg/min) were converted to percentages of predicted values using a formula based on a representative South Korean sample32,33.

Postoperative cardiopulmonary complications

PPC and PCC occurred during hospitalization or readmission within the first 60 days postoperatively were identified from prospectively collected data. PPC was defined as any of the following condition; (1) significant atelectasis requiring bronchoscopic toileting or reintubation; (2) pneumonia; (3) ARDS, (4) acute exacerbation of COPD24,34. PCC was defined as following; (1) acute myocardial infarction; (2) atrial arrhythmia associated with the use of antiarrhythmic drugs or anticoagulant; (3) ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation. (4) cardiac arrest or any cardiac related death34,35. All postoperative complications were classified according to Clavien–Dindo classification36, grade II or higher complication were included for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Differences in baseline characteristics were compared between patient groups treated with and without the perioperative use of a bronchodilator using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. The primary outcome was the change in FEV1 following perioperative bronchodilator treatment. We compared quantitative changes in pulmonary function, including absolute values of FVC and FEV1, and the percentages of predicted values (% pred) for FEV1 and FVC at each time point in patient groups treated with and without a perioperative bronchodilator using linear mixed models with random intercepts and random slopes37. We estimated differences in the changes of pulmonary function from preoperative values (with 95% CI) between participants treated with and those treated without a perioperative bronchodilator. To control for potential confounding factors, we adjusted analyses for age, sex, body mass index [underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–22.9 kg/m2), overweight (23–24.9 kg/m2), or obese (≥ 25 kg/m2)], smoking status (never, past, or current), surgical extent (limited resection, lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy), VATS, and preoperative baseline FEV1 (mL). We also performed the same analysis using IPTW of preoperative baseline FEV138. To evaluate if changes in pulmonary function correlated with the type of bronchodilator used, we conducted additional analyses after separating patients into mono and dual bronchodilator groups. In addition, we performed stratified analyses to evaluate if the association of perioperative use of bronchodilator with change in FEV1 at 4 months after surgery differed in pre-specified subgroups defined by age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), sex, obesity (no vs. yes), smoking (never vs. ever), and adjuvant therapy (no vs. yes). We also performed sensitivity analyses in patients who received lobectomy (N = 194). We considered a P-value < 0.05 as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

S.H.S., S.S., Y.I., J.C., D.K., H.Y.P. contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. S.H.S., S.S., Y.I., B.-H.J., K.L., S.-W.U., H.K., O.J.K., J.H.C., H.K.K., Y.S.C., J.K., J.I.Z., Y.M.S., and H.Y.P. contributed data acquisition. S.H.S., S.S., Y.I., and G.H.L. had full access to all of the data in the study. D.K. takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have read and contributed critical revision to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Sun Hye Shin, Sumin Shin, Yunjoo Im, Danbee Kang and Hye Yun Park.

Contributor Information

Danbee Kang, Email: dbee.kang@skku.edu.

Hye Yun Park, Email: hyeyunpark@skku.edu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-86791-1.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park HY, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer incidence in never smokers: A cohort study. Thorax. 2020 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moro-Sibilot D, et al. Comorbidities and Charlson score in resected stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;26:480–486. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00146004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 4.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Brunelli A, Kim AW, Berger KI, Addrizzo-Harris DJ. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e166S–e190S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Licker MJ, et al. Operative mortality and respiratory complications after lung resection for cancer: Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and time trends. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2006;81:1830–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellenberger C, et al. Patient and procedural features predicting early and mid-term outcome after radical surgery for non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018;10:6020–6029. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.10.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soriano JB, Zielinski J, Price D. Screening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2009;374:721–732. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuchi Y, et al. COPD in Japan: The Nippon COPD Epidemiology study. Respirology. 2004;9:458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the mortality of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014;9:812–817. doi: 10.1097/jto.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cazzola M, Matera MG. Bronchodilators: Current and future. Clin. Chest Med. 2014;35:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GOLD. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2020 REPORT). http://www.goldcopd.org. Accessed 9 Apr 2020. (2019).

- 13.Kobayashi S, Suzuki S, Niikawa H, Sugawara T, Yanai M. Preoperative use of inhaled tiotropium in lung cancer patients with untreated COPD. Respirology. 2009;14:675–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolukbas S, Eberlein M, Eckhoff J, Schirren J. Short-term effects of inhalative tiotropium/formoterol/budenoside versus tiotropium/formoterol in patients with newly diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring surgery for lung cancer: A prospective randomized trial. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011;39:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makino T, et al. Long-acting muscarinic antagonist and long-acting beta2-agonist therapy to optimize chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prior to lung cancer surgery. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018;8:647–652. doi: 10.3892/mco.2018.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki H, et al. Efficacy of perioperative administration of long-acting bronchodilator on postoperative pulmonary function and quality of life in lung cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Preliminary results of a randomized control study. Surg. Today. 2010;40:923–930. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calzetta L, Rogliani P, Matera MG, Cazzola M. A systematic review with meta-analysis of dual bronchodilation with LAMA/LABA for the treatment of stable COPD. Chest. 2016;149:1181–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young RP, et al. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur. Respir. J. 2009;34:380–386. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00144208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones PW, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in pharmacological trials. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014;189:250–255. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1863PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Agteren JE, Carson KV, Tiong LU, Smith BJ. Lung volume reduction surgery for diffuse emphysema. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016;10:CD001001. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001001.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han MK, et al. Association between emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease outcomes in the COPDGene and SPIROMICS Cohorts: A post hoc analysis of two clinical trials. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;198:265–267. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0051LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin S, et al. Joint effect of airflow limitation and emphysema on postoperative outcomes in early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;48:1743–1750. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01148-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Licker M, et al. Perioperative medical management of patients with COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2007;2:493–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miskovic A, Lumb AB. Postoperative pulmonary complications. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017;118:317–334. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park B, et al. A retrospective comparative analysis of elderly and younger patients undergoing pulmonary resection for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016;14:13. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0762-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gershon A, et al. Cardiovascular safety of inhaled long-acting bronchodilators in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:1175–1185. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CH, et al. Inhaled bronchodilators and the risk of tachyarrhythmias. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015;190:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lange P, et al. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:111–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edge SB, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, (editors). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition (Springer, 2010).

- 30.Miller MR, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2005;58:230–242. doi: 10.4046/trd.2005.58.3.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Thoracic Society. Single-breath carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (transfer factor). Recommendations for a standard technique—1995 update. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.152, 2185–2198. 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520796 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Park J, Choi I, Park K. Normal predicted standards of single breath carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of lung in healthy nonsmoking adults. Korean J. Intern. Med. 1985;28:176–183. doi: 10.3904/kjim.1986.1.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee H, et al. Prognostic value of 6-min walk test to predict postoperative cardiopulmonary complications in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jammer I, et al. Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: A statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:88–105. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzmaurice GM, Ravichandran C. A primer in longitudinal data analysis. Circulation. 2008;118:2005–2010. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.714618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robins JM, Rotnitzky A, Zhao LP. Estimation of regression coefficients when some regressors are not always observed. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1994;89:846–866. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1994.10476818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.