Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 or Covid-19 pandemic has affected many operations worldwide. This predicament also owes to the lockdown measures imposed by the affected countries. The total lockdown or partial lockdown devised by countries all over the world meant that most economic activities, be put on hold until the outbreak is contained. The decisions made by authorities of each affected country differs according to various factors, including the country's financial stability. This paper reviews the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on maritime sectors, specifically shipping, fisheries, maritime tourism, and oil and gas sector. The period of this study covers economic activities between the month of January towards the end of July 2020. Also discussed in this journal, is the analysis of the potential post-outbreak situation and the economic stimulus package. This paper serves as a reference for future research on this topic.

Keywords: Covid-19, Fisheries, Oil and gas, Maritime tourism, Shipping, The economic stimulus package

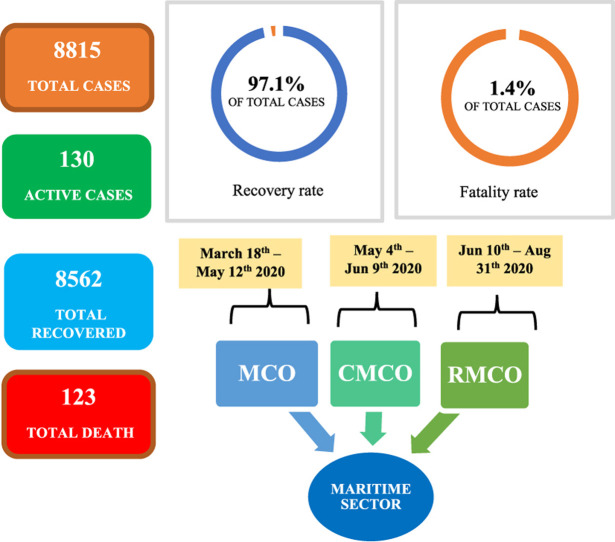

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Novel Coronavirus or Covid-19 was first discovered in Wuhan, China on December 31, 2019. Since the first outbreak in Wuhan, the number of cases has spiked in that region. The Chinese government imposed a lockdown for the entire region to contain the spread of this contagious virus. Whilst China reached peak Covid-19 cases of around 80,000 cases at the end of February 2020, other countries around the world had just discovered and learned about Covid-19 cases in their respective countries. Most countries realised the presence of Covid-19 between the end of February and the middle of March 2020.

Despite some early calls for every country to implement control measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus, considering the chaotic outbreak experienced by the Chinese government, the outbreak has spread faster than most people expected. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO), declared the Covid-19 outbreak a pandemic based on assessments and the increasing number of cases globally (118,000), at that time with 144 countries affected. As of early April 2020, the highest cases recorded was in the United States of America (USA), amounting to 215,344 cases followed by Italy and Spain at 110,574 and 104,118 cases respectively (Worldometer, 2020). At that point in time, the outbreak had affected 203 countries and two international conveyances, with 939,131 confirmed cases and 47,331 deaths. This was the worst outbreak in the world since 1990, besides posing a higher magnitude than the Ebola outbreak in 2014, which largely affected west Africa (Bowles et al., 2016; Huber et al., 2018). There were several actions implemented by the affected countries to contain the virus, including imposing total lockdowns, partial lockdowns, and movement control orders. These measures were not economically friendly. The managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Georgieva (2020) in her speech stated that retail, hospitality, transport, and tourism might face substantial consequences. In fact, Georgieva (2020) foresees a severe economic impact arising from the pandemic; “It is already clear, however, that global growth will turn sharply negative in 2020, as you will see in our World Economic Outlook next week. We anticipate the worst economic fallout since the Great Depression”. Furthermore, she stated that 170 countries might face negative per capita growth.

Moving on from the alarming declaration by the IMF managing director, this study is aimed at reviewing the impact of the Covid-19 outbreak on developing countries, such as Malaysia. In particular, this article will focus on the impact during and post-Covid-19 outbreak.

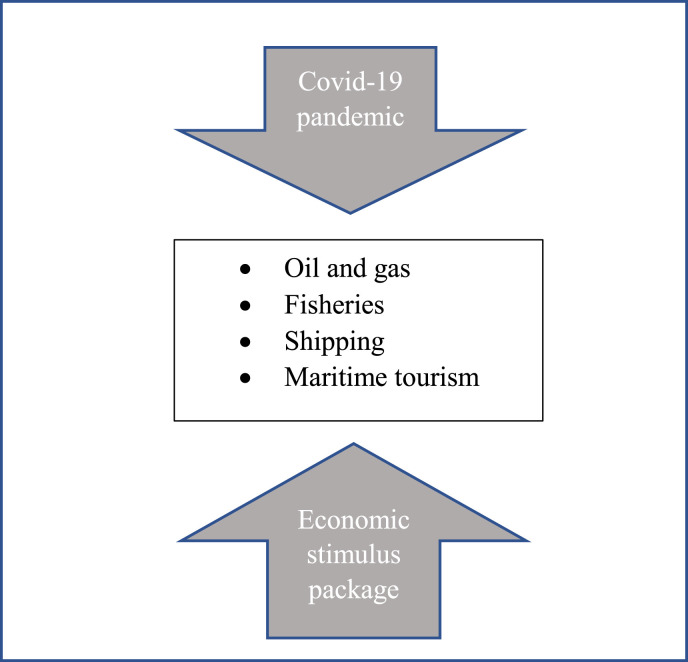

Looking at the reliance of the Malaysian economy on maritime sectors, it was certain that the pandemic would have serious implications on individuals and organisations. Besides that, this study also looks into the economic stimulus packages that were introduced to ensure the sustainability of business sectors. Fig. 1 illustrates an overview of the study.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study.

2. Covid-19 scenario in Malaysia

In Malaysia, the first confirmed case of Covid-19 was recorded on January 25, 2020, involving three Chinese nationals. Responding to these cases, the Covid-19 patients were treated and isolated at a hospital in Johor Bharu. These confirmed cases were considered under control as all businesses and operations were conducted as usual. The first Covid-19 case involving a Malaysian was recorded on February 4, 2020 (BERNAMA, 2020), which took Malaysia's cumulative Covid-19 cases to 10 cases.

On March 16, 2020, the movement control order (MCO), was announced by the prime minister of Malaysia following the increase in number of positive Covid-19 cases. The MCO was effective from 18 to March 30, 2020. The number of positive Covid-19 cases during the date of the announcement, was at 553 (Ministry of Health, 2020). Under the MCO, six main orders were enforced; i) prohibition of any mass gatherings, ii) prohibition of movement of Malaysians from going abroad, iii) prohibition of movement of foreigners into Malaysia, iv) closure of all schools and kindergartens, v) closure of higher educational institutions and skills development centres, vi) closure of all government and private premises except for those involved in essential services (Prime Minister of Malaysia speech, March 16, 2020). The first phase of MCO was initially until March 30, 2020 but ended up being extended several times until May 12, 2020. To strike the balance between public health concerns and economical needs, on May 1, 2020, the prime minister announced the conditional movement control order, or CMCO. The CMCO phase, which took effect on May 4, 2020, allowed the majority of economic sectors to begin operations, subjected to strict Standard Operational Procedures (SOP) (Prime Minister Office, 2020). However, businesses and other recreational activities that involve mass gatherings were not allowed.

Following this, recovery movement control order (RMCO) was introduced, owing to the need of striking balance between economical needs and public health. The choice to implement the RMCO was discussed carefully and decided based on the low number of daily cases (19) on June 7, 2020. This RMCO measure was supposed to take place from the tenth of June until the end of August 2020. During this phase, most activities and business operations are allowed, but have to adhere to the Covid-19 SOP outlined by the government. These include maintaining a physical distance of 1 m, wearing a face mask in close public premises, and the requirement of temperature taking before entering any premises. Adding to that SOP was the recording of details, such as name and contact number via MySejahtera - an application developed by the government of Malaysia, that helps the authorities in conducting contact tracing in the event of a new Covid-19 case (MySejahtera, 2020). Table 1 summarises the MCO, CMCO and RMCO implemented by the Malaysian government, including the durations, announcement date and number of cases. The ‘Number of cases’ column consists of the number of daily cases with total number of cases (in parentheses), followed by the number of ‘active’ cases - after subtracting the number of recovered cases.

Table 1.

Covid-19 control measures in Malaysia.

| Covid-19 measures | Period | Announcement date | Number of cases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCO Phase 1 | March 18 to March 30, 2020 (2 weeks) | March 16, 2020 | 125 (553) active: 511 | Prime Minister Office (2020) |

| MCO Phase 2: 1st extension | April 1 to April 14, 2020 (2 weeks) | March 25, 2020 | 172 (1796) active:1578 | Prime Minister Office (2020) |

| MCO Phase 3: 2nd extension | April 15 to April 28, 2020 (2 weeks) | April 10, 2020 | 118 (4346) active: 2446 | Prime Minister Office (2020) |

| MCO Phase 4: 3rd extension | April 29 – May 4, 2020 (1 week) | April 23, 2020 | 71 (5603) active: 1966 | Prime Minister Office (2020) |

| CMCO | May 4 – May 12 (1 week) | May 1, 2020 | 69 (6071) active: 1758 | Prime Minister Office (2020) |

| CMCO 2 (1st extension) | May 12 – Jun 9, 2020 (4 weeks) | May 10, 2020 | 67 (6656) active: 1523 | Prime Minister Office (2020) |

| RMCO | Jun 10 – Aug 31, 2020 | Jun 7, 2020 | 19 (8322) active: 1531 | Prime Minister Office (2020) |

3. Maritime industry

Kwak et al. (2005), classified the maritime industry into four main sectors, which are i) marine transportation, ii) harbour, iii) fisheries and marine products, iv) shipbuilding and other marine transportation. In Malaysia, maritime sectors play a vital role in improving the local economy. Malaysia's oceans serves as host shipping routes, providing a medium for potential economic activities, such as transportation, tourism, shipbuilding and ship repairing, and port services (Kaur, 2015). This sector contributes to 40% of Malaysia's gross domestic product, where 15% is from oil and gas, followed by fisheries at 9.4% (Hamzah, 2019). The remaining percentage accounted for maritime-related sectors including tourism. The most important maritime sectors according to economic contributions are; i) ocean and coastal shipping, ii) shipbuilding and ship repairing, iii) port services, iv) oil and gas, v) fisheries, and vi) naval defence and other enforcement agencies (Saharuddin, 2001). However, the last sector (naval defence and other enforcement agencies), was cited by the author because of its public contributions, and not from direct economical perspectives. In Malaysia, maritime industry classification is still ambiguous. For the purpose of this analysis, this study will focus on four maritime sectors: i) shipping, ii) oil and gas, iii) fisheries, and iv) maritime tourism.

3.1. Shipping sector

Malaysia's strategic location with coastal lines, has been regarded as added value to its development and prosperity. As one of the country that rely on the seaborne trade, shipping sector is prominent to Malaysia, making Malaysia a leading maritime nation (Mohd Zaideen, 2019). Malaysia hosts the Strait of Malacca, one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. This strait is considered to be among the most heavily used straits for international navigation, with more than 80,000 ships traversing these sea lanes annually (Mohd Zaideen et al., 2019), carrying an estimated 25% of the world's traded goods. This has allowed Malaysia to place itself firmly as a major world transhipment hub, with a regular port of call for different types of vessels. VLCC, tanker vessels, LNG carriers, cargo vessels, container vessels, bulk carriers, passenger vessels, and fishing vessels are among vessels that navigate the strait in accordance to the analysis of the vessel characteristics reporting to the ship reporting system, STRAITREP (Marine Department Malaysia, 2020). Government-owned ports, such as Port Klang and Port of Tanjung were ranked 12th and 18th among the busiest ports in the world (World Shipping Council, 2020), a witness to Malaysia's distinction in the maritime sector. The merit of shipping and port division has contributed to the expansion of the Malaysian economy, hence making Malaysia a developing maritime nation.

Malaysia depends greatly on the seas to facilitate its trade while providing lots of economic opportunities to the coastal communities. Many economic activities are carried out at sea, and the sector has also provided a potential source of employment and career opportunities.

Covid-19 pandemic is affecting world shipping businesses and markets in terms of growth and fleet development. The collected data from a global network of Automatic Identification System (AIS) receivers, shows a depletion in world shipping activity from the month of March to June 2020, when the most severe restrictions were enforced. These restrictions produced a variation of mobility quantified between −5.62% and −13.77% for container ships, between 2.28% and −3.32% for dry bulk, between −0.22% and −9.27% for wet bulk, and between −19.57% and −42.77% for passenger ship (Millefiori et al., 2020). Like many other countries, Malaysia has also responded to the pandemic by imposing lockdown measures and restricting movement. Putting the country into lockdown caused demand to drop across the board, and lead to disruption of transportation networks encompassing the maritime sector specifically the port and shipping sector, rail, air, and trucking industries (Loske, 2020). It is reported that Malaysia's exports decreased by 25.5%year-on-year in May 2020 - the hardest decline since May 2009, while imports dropped by 30.4% year on year (BERNAMA, 2020). The Covid-19 pandemic has also showcased the flaw of port efficiency and hinterland connectivity in Malaysia's response to crises. For example, vendors fail to pick up their cargo at port due to the closure of their warehouses, and some ports have reduced workforce, which exacerbates the cargo congestion. The shortage of workers is taking a toll on global shipping with interruptions in transit, delays, and accumulation of cargo both at the origin and destination ports. This has indirectly caused interference to the supply chain, especially on the movement of essential goods like food and medical supplies. Also during the MCO, the movement of goods has been rather limited, which then results in the high stacks of containers for non-essential goods, especially in Port Klang as reported by the Federation of Malaysian Freight Forwarders (Shankar, 2020). Problems like this often lead to port disruptions apart from the slowdown in supply chains, thus interrupting all links of international trade.

International trade plays a large role in the Malaysian economy. Malaysia mainly exports electrical and electronics (E&E) products and commodity-based products, especially petroleum, crude petroleum and rubber products (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2020). One of Malaysia's main trade partners in 2019 was China with 14% of total exports. The slump in demand for goods from China is generating a ripple effect on everything from container ships to oil tankers (Berti, 2020). These challenges have weakened the efficient movement of trade flows and supply chain operations worldwide, which can significantly erode the transport services trade liberalisation and trade facilitation gains achieved over the years (UNCTAD, 2020). As a result of that, Malaysia's total trade is expected to register a decline due to softer global demand caused by unfavourable economic conditions during MCO. Although the shipping sector is regarded as essential services, and was allowed to operate, Malaysia Shipowners' Association (MASA) chairman, Datuk Abdul Hak Md Amin, mentioned that shipping companies suffered heavy losses during the MCO, with an average potential short-term loss of between RM15 million and RM30 million for normal operations due to the decline in revenue (Malaysia Shipowners' Association, 2020). The decline in trade during the pandemic was similar in other regional countries, such as Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia. This decline fuelled the prediction that many jobs would be wiped out by the downturn brought by the pandemic. The increase in unemployment would further prolong the downturn in economic activity. In fact, due to control measures and travel restrictions, there are 300,000 seafarers stranded at sea because of the crew change crisis (International Transport Workers Federation, 2020). Despite all that, Malaysia still relies on shipping operations for the supply of Covid-19 personal protective equipment (PPE), which received increased demand during the pandemic.

Malaysia's shipping industry is still battling to cope with the fragility of the global supply chain. What shipping will look like post-Covid-19 is unpredictable as Malaysia enters the RMCO phase up until August 31, 2020. Governments are called upon to assist and provide financial support for businesses that have been impacted by the Covid-19 outbreak.

3.2. Oil and gas sector

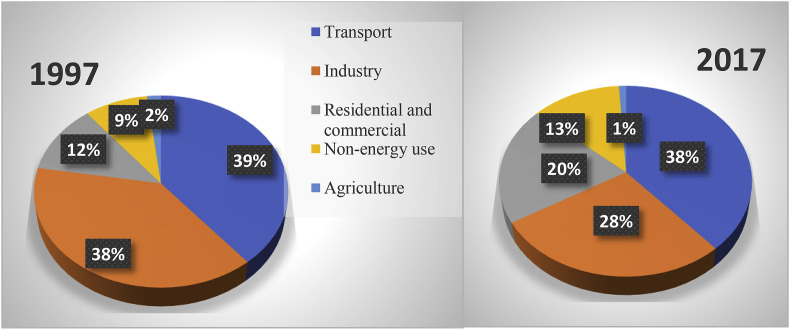

The operating locations of the oil and gas exploration and production activities are concentrated near Kelantan and Terengganu, two states in the East Coast region of Peninsular Malaysia (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2015). The other two operating areas are Sabah and Sarawak on the island of Borneo. Fig. 2 illustrates the demand for petroleum products across different sectors in Malaysia. It can be observed that petroleum products are largely consumed for transportation. Indeed, the amount of petroleum products consumed for transportation did not display a drastic change for more than 20 years.

Fig. 2.

Malaysia's energy consumption according to sector.

Sources: Energy Commission (2019).

However, the implementation of MCO has drastically reduced the usage of automobiles, industrial activities, shipping, and transportation. This impact was immediately felt by Malaysia's oil and gas sector. The drop in demand was estimated to be more than 30% in April 2020. Lack of physical demand for crude oil quickly resulted in the plunge of oil prices. LNG prices, which were already under pressure from weak fundamentals, have also fallen further as working from home arrangements has caused a sharp decline in the usage of electricity in Malaysia. Towards the end of mid-June 2020, the lockdown restrictions began to ease and the slow return of the market to normal conditions is underway. The same occurrence was observed for the oil and gas sector as demands increased across the world where it was mostly utilised for transportation purposes. Covid-19 pandemic has impacted the world's crude oil price per barrel, due to low consumption from lockdowns and restricted movement around the world. The decline in oil consumption was attributed to the low consumption used domestically and in commercial transportation, including international flights. It is reported that the Brent crude oil price plummeted by 30%, the sharpest drop since the Gulf War in 1941, to around $34 per barrel (Scheneider and Domonoske, 2020).

Until early April 2020, none of the Malaysian oil and gas companies issued a statement on employee layoff. This may be due to the fear of public backlash. Having said that, Aker Solutions, a Norway based company, which has operations in Malaysia had declared a plan on employee sanctions to reduce the company's costs. In their statement, they mentioned about staff reduction, which will involve the company's Malaysia branch in Port Klang. Subsequent to this, Shahril Samsudin, Chief Executive Officer of Sapura Energy Berhad, a multinational oil and gas company in Malaysia, has been reported to introduce fifty steps in cost reductions. These include a 50% salary cut for higher management with immediate effect, and reduction of manpower (Malaysia National News Agency, 2020). Recently, Sapura Energy CEO had announced to lay off 800 of their workforce as one of the cost reducing steps (Aziz, 2020). Another major oil-related multinational company, British Petroleum (BP), cut 15% of its workforce equivalent to 10,000 out of the total staff worldwide (Nasralla and Bousso, 2020). This staff reduction will involve BP staff worldwide including Malaysia, which will take place by the end of 2020. On top of that, BP CEO had reported shifting to renewable energy following the severity of the coronavirus crisis. Based on the current scenario of MCO and lockdowns around the world, the oil and gas sector will only be able to recover once the pandemic is over. Given the projection of the cease in Covid-19 cases is expected to be after six months, or until the end of 2020, this sector will not recover anytime soon. While most countries shut their borders, demand for petroleum products mainly from transportation will remain stagnant.

3.3. Fisheries sector

Malaysia lies on the shallow continental Sunda Shelf, which is a productive area for marine biotic resources that local fishers have harvested for centuries (Forbes, 2014). The shallowness allows the rays of the sun to penetrate the depth of the waters, hence generating the growth of plankton, which is a natural diet for many types of fish (Rusli, 2012). The marine fisheries industry in Malaysia contributes extensively to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as well as to the national economy in terms of income and foreign exchange. This sector generates employment, provides sources of protein for food, while contributing to the Malaysian economy locally and through the export potential (Solaymani and Kari, 2014). A study on fishermen in east coast Malaysia indicated that 70% of their household income came from fishing (Solaymani and Kari, 2014). In addition to that, fishing has been the sole source of income and food for island communities in Malaysia (Islam et al., 2017). The total export value of fish and fishery products in 2017 were RM3.157 billion or $738 million (Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2017), while the import value was RM4.34 billion or $1.01 billion. The total fish consumption recorded in the same year was 35.4 kg per person per year (Fish Development Authorities Malaysia, 2016). From a global perspective, the fisheries sector is highly driven by international trade. Therefore, the closure of some country borders severely affected the import and export activities (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2020). Furthermore, the lockdown imposed by most countries affected by the pandemic, had reduced the demand for fish products, especially from restaurants, hotels, and other tourism attractions.

Looking at the import and export values of the fisheries sector in Malaysia, this sector is dependent on global trade. Therefore, the control measures imposed by many countries had restricted international trade. In other words, there will be a drop in earnings from fish and fishery products exported to other countries, and disruptions of supply from the imported fish and fish products due to the closure of the borders. For instance, in mid-February 2020, the seafood export from Malaysia to Singapore was already down by 50% (Aruno et al., 2020). From another perspective, local consumers have to shift their consumption from a combination of local fish and imported fish to focusing on local fish. This disruption of export and import activities predominantly affected the income of fishermen from the first until the fourth phase of MCO (refer Table 1). In the first phase of MCO, the income of Malaysian fishermen declined by 50% due to the fear of them being contracted by Covid-19 virus, adding to the low demand by Malaysians who preferred to spend more time at home during this phase (Berita RTM, 2020). It was found that the small scale fishermen were most affected by the pandemic, especially those residing in the island far from access to larger communities (Jomitol et al., 2020). The price of fish sold to the middle person was reported to be 50–70% lower than before the implementation of MCO (Jomitol et al., 2020). Moreover, there are 33% of fisheries’ sector workers in Malaysia reported to have lost their job as a result of slow demand of fish and fish-related products (Waiho et al., 2020).

The demand for fish and fish-related products from local consumers may have improved since the announcement of CMCO, which took effect from May 4, 2020. However, the earnings from exported fish and fish-related products will require more time to recover as some of the main exported countries, such as the Republic of Iran and the United States of America are currently battling the pandemic (Worldometers, 2020).

3.4. Maritime tourism

Maritime tourism or also known as marine tourism or coastal tourism, is referring to the activities comprising of sea transportation such as cruising, beach activities, scuba diving, snorkelling, fishing sport, and other recreational activities that occur in the marine environment (Kizielewicz, 2012). In Malaysia, islands are among the most popular maritime tourism spots (Mapjabil et al., 2015). Tourism value earned through Redang Island marine park alone was recorded at RM10.1 million annually. Out of all the tourists that visit Redang Island marine park, more than 40% are foreigners while the rest are local tourists (Marine Park of Malaysia, 2017).

Malaysia hopes to see a soar in the tourism industry in the year 2020 through the Visit Malaysia 2020 campaign, but all hopes have been turned upside down since the pandemic hit China. The chief executive officer of Malaysia Hotel Association estimated more than 60% losses. Wage cut and unpaid leave were executed for companies to survive through this pandemic. However, the same could not be done by a smaller company (Bethke, 2020). In general, 50% of foreign tourists are mainly from Singapore and China. Thus, the pandemic, which initially took place in China, had caused a huge drop in the number of tourists to Malaysia (Foo et al., 2020). Around 170,000 hotel bookings had been cancelled from early January to the middle of March 2020, which caused a total loss of RM68 million (Foo et al., 2020). This figure did not include the amount of losses preceding that period until CMCO was implemented. In regard to this, it is reported that many hotels had ceased operations which led to countless hotel staff being left unemployed. According to the report of The Star Malaysia, a sample size of 56,299 workers in the hotel industry was taken and found that 2041 staff were laid off while 9773 (17%) were asked to take unpaid leave, and 5054 (9%) got pay cuts due to the pandemic (Karim et al., 2020).

The announcement by the prime minister to reopen local tourism had provided hope to this sector (Prime Minister Office, 2020). Despite the country's border remaining closed due to the pandemic, the surge in domestic tourism showed a positive sign in this sector. In general, domestic tourism can be described as people travelling within the country. According to the Department of Statistics in 2019, a total of 239.1 million domestic tourists were recorded with a growth of 8.1% as compared to the previous year in 2018 (RM221.3 million). There are various domestic tourism campaigns initiated by the Ministry of Tourism as other agencies offer discounts and promotions to attract more local tourists (Ministry of tourism arts and culture Malaysia, 2020; New Straits Times, 2020; The Star, 2020). As such, the recovery plan is essential for the improvement of domestic tourism in the country. The government has taken efforts to boost domestic tourism in Malaysia, such as encouraging Malaysians to travel domestically. The closing of the border had put Malaysia into two scenarios. First, Malaysia might lose profit from foreign tourists, but at the same time, Malaysians had no choice except to spend their vacation in Malaysia. This eventually will improve the economy. Nevertheless, opening the border would not be an option at the moment as many countries are still struggling to contain the pandemic with higher Covid-19 cases reported daily. Looking at this situation, maritime tourism has to rely solely on local tourists to compensate for the drop in foreign tourists.

4. Economic stimulus package

The Malaysian government has introduced economic stimulus packages to ease the burden of individuals and business organisations affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. In general, the stimulus packages serve three main purposes; to protect the rakyat (nation), support businesses, and strengthen the economy as summarised in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 .

Table 2.

Stimulus package towards protecting the rakyat (nation).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

Economic stimulus package towards business sector.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Stimulus package towards strengthening the economy.

|

|

|

Table 5.

Tax-related initiatives.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first aim, protecting the rakyat, is designed to reduce the burden of the nation affected by the pandemic through one-off cash aids. Other efforts include providing special monthly allowances to motivate frontliners directly involved in combating the virus, as well as towards various agencies assigned in enforcing MCO. There is also a moratorium offered by banking institutions for six-month periods on specific loans.

The second aim, supporting businesses, listed out stimulus packages for all business sectors (Table 3). Among these initiatives are financing facilities for all SMEs, a moratorium on loan repayment, and other grants to encourage business sustainability. From the listed packages, there are several efforts directly focused on the fisheries sector. These include a RM40million grant to enable fishermen and other agriculture businesses to sell their product directly to the consumer, RM1 billion towards Food Security Fund through various assistance to increase domestic production, and RM100,000–200,000 for development of agro-based products towards farmers' associations and fishermen's associations. These initiatives not only to ensure the survival of fishermen, but also help to achieve food security in Malaysia.

Apart from the fisheries sector, there are various initiatives concentrated on supporting the tourism sector. These include microcredit facilities with a 4% interest rate with delayed repayment of instalment, and 15% discount rates for electricity bills for the tourism sector. Besides that, a RM500 million government provision for travel discount vouchers, tourism encouragement in Malaysia through matching grants, and tourism promotions. This will boost local tourism after three months of close down. Further, the Malaysia government has also introduced some initiatives aimed at strengthening the economy. Apart from upgrading current facilities, it is expected to provide more work for local companies.

Other than that, there are some tax-related initiatives introduced to benefit individuals and business sectors (Table 5). For instance, individual and business firms are eligible for postponement of income tax payment. Tax deduction on the purchase of PPE will ensure staff safety is taken care of by the employer. To encourage international shipping business participation, companies that established and operate business in Malaysia are granted double tax deduction. If we look closely at the tax initiatives, there is an exemption of individual income tax on local tourism spend to encourage local tourism. Table 6 presents specific economic initiatives for maritime sectors in the study.

Table 6.

Specific measures to stimulate maritime sectors.

| Sectors | Measures |

|---|---|

| Shipping |

|

| Maritime tourism |

|

| Fisheries |

|

| Oil and Gas |

|

Based on the economic situations of four maritime sectors and economic stimulus packages introduced by the government, the economic impacts during and post Covid-19 pandemic are reviewed. Almost all four sectors received negative impacts from the Covid-19 pandemic based on five attributes derived from the literature as summarised in Table 7 . However, maritime tourism has suffered greatly during the pandemic (MCO – CMCO period), owing to the total closure of business operations. Shipping, on the other hand, is an essential service undergoing continuous operation during the outbreak despite the slow demand. Thus, the impact on the sector is less in comparison to the other three sectors, except for the case of poor seafarers’ crew change management in many countries.

Table 7.

The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on maritime sectors.

| Sectors | Product/service demand | Social impact | Financial impact | Business operation | Global business |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shipping | Exports: ↓ 25.5%, Imports: ↓ 30%, |

300,000 seafarers trapped at sea globally. | 15–60 million losses | Business as usual with strict SOP | Container ship: ↓13.77% Passenger ship: ↓42.77% |

| Maritime tourism | Not allowed during MCO - CMCO | Laid off: 2041 (3.6%), unpaid leave: 9773 (17%), pay cut: 5054 (9%). |

60% losses | Total closure during MCO -CMCO | No international tourist due to closing of border |

| Fisheries | Low local and global demand | Fishermen income: ↓50% Job losses: 33% |

Price of fish: ↓50–70% | Business as usual with strict SOP | Seafood imported to Singapore: ↓50% |

| Oil and gas | Local demand: ↓ 30% | Sapura Energy: 50% salary cut off for higher management, 800 staff lay off (20%) | No data | Business as usual with strict SOP | Oil prices: ↓ 30% BP: Cut off 15% staff worldwide (10,000) |

For the post-pandemic period (RMCO period onwards), the impact on the sectors that received more government incentives will be lessened, coupled with relaxation of control measures. This includes the reopening of eateries and local tourism attractions. Therefore, fisheries and maritime tourism are particularly expected to recover faster than other sectors. The shipping sector may take time to recover from the slow demand but the RMCO period allows most businesses to operate. This will contribute to the increase in import and export activities, hence improving shipping sector business. Meanwhile, the oil and gas sector may face significant economic impact post-pandemic due to low crude oil prices attributed to the low demand worldwide, as many countries are still grappling with the Covid-19 virus. Some economists predict that the oil and gas sector may experience slow recovery until 2024 (Barbosa et al., 2020). The decision of some major oil companies to transition towards renewable energy, combined with the pressure for greener energy may exacerbate the future of the oil and gas sector.

5. Potential strategies for a way forward

Although the control measure is needed to delay the contraction of the virus within the Malaysian community, the impact on the Malaysian economy shall not be undermined. Undeniably, the Covid-19 outbreak has been causing a huge impact on maritime communities in terms of business operation, financial, social impact (relating to employability) as well as global business. Despite negatively affecting the economy and the nation's wellbeing, the pandemic forces the industry to not only accelerate their capability in responding to disruptions, but also to devise better long-term strategies in dealing with uncertainties and adopt more sustainable operation.

For instance, the capability of shipping services to continue providing undisputed transportation of foods and medical supplies is critical. Hence, the shipping sectors will need to become agile and resilient in adapting to this changing situation. They need to focus on erecting effective response strategies and execution plans so that they can recover quickly during disruptions and resume stronger than before. On the other hand, we can assume that the Covid-19 pandemic will be a tipping point for the application of remote technologies and automation in shipping. Autonomous port for instance, may be able to manage the crew change with limited contact, which reduces the possibility of virus contraction. The pandemic could be a significant driver in the adaption of new technologies, collaborative solutions and greater utilisation of space and resources (Schwerdtfeger, 2020). The innovation in the shipping system seems to be more sustainable, safe, efficient and reliable in minimizing pollution and maximizing energy efficiency.

For the oil and gas industry, Malaysia has to look into the option of energy transition which has been taken by major oil and gas players. The transition may not occur within a short period of time, thus requires early investment and technical knowledge to materialise it. This is very important as the oil and gas sector has long been a major economic contributor to Malaysia. The strategy for energy transition shall consider the large number of employees, which is currently around 40,000 involved in the sector. An effective capital management will enable smooth energy transition.

For fisheries sector, diversify the supply chain strategy including selling fish and seafood products through online platforms. This may help the sector to sustain through this period. Existing online platforms, such as Myfishman, provide commendable support to local fishermen (Harper, 2020). This platform recorded more demand during the pandemic as movement is limited. Having said that, the usage of online platform in the fisheries sector is still progressing as it currently supports the fishermen in the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. A comprehensive and wider coverage of online fisheries platforms is required to make this sector more sustainable. Other than that, a better post-harvest technology needs to be equipped to maintain the freshness of produce, should there be some delay in transportations for both local and global market.

Malaysia is now developing measures to build a more resilient tourism economy by preparing plans to support the sustainable recovery of tourism post Covid-19. The tourism sector suffered the most during the Covid-19 outbreak and requires a carefully planned strategy to mitigate it. Therefore, government support must be coordinated to ensure capacity building and productivity of the tourism key player. A lot of initiatives should be conducted by tourism players to encourage domestic tourism as this will be the only safest possible solution until the pandemic is ceased. Reshaping the industry towards a sustainable and innovative ecosystem will definitely benefit the tourism sector as well as local economies.

6. Conclusion

This study provides an overview of the Covid-19 scenario in Malaysia. Furthermore, this study examines the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on four maritime sectors based on the review from January until end July 2020. Additionally, a post-pandemic situation was presented, which considered the current situation and the various economic stimulus packages introduced by the Malaysian government. Services sectors such as maritime tourism is the most affected, owing to the fact that it is considered a non-essential service, hence experiences total close down during the MCO until CMCO period. However, economic initiatives and domestic tourism may mediate the post-pandemic impacts. Based on the four sectors involved, shipping is considered less affected in comparison to other sectors, considering the high demands of PPE products and test kits during the pandemic. The oil and gas sector on the other hand, received no sector-specific incentives despite being the major economic contributor. Overall, the stimulus packages are expected to assist all the business sectors to sustain through this economic downturn. Apart from the government incentives, drastic changes are required in overall operation efficiencies for each sector to better respond to unprecedented situations. Malaysia's ability to contain the spread of the Covid-19 virus, through the introduction of the RMCO measure, provides an extra advantage to regain economic strength following the economic downturn during the MCO and CMCO period.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aruno C., Lai A., Timbuong J., Aravinthan R. The Star Online; 2020, February 17. Seafood Export to Singapore Down by Half.https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/02/17/seafood-export-to-s ingapore-down-by-half [Google Scholar]

- Aziz A. The Edge Malaysia; 2020, June 25. Sapura to Cut off 20% of its 4000 Fulltime Staff.https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/sapura-energy-cut-20-its-fulltime-employees-worldwide [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa F., Bresciani G., Graham P., Nyquist S., Yanosek K. McKinsey and Company; 2020. Oil and Gas after COVID-19: the Day of Reckoning or a New Age of Opportunity?https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/oil-and-gas-after-covid-19-the-day-of-reckoning-or-a-new-age-of-opportunity [Google Scholar]

- Berita R.T.M. 2020. Nelayan Kuala Selangor terjejas Teruk Ekoran Covid 19. Radio Televisyen Malaysia.https://berita.rtm.gov.my/index.php/ekonomi/16727-nelayan-kuala-selangor-terjejas-teruk-ekoran-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- BERNAMA . The Malaysian Reserve; 2020, July 20. COVID-19, Intensifies the Urgency to Accelerate Shipping Masterplan.https://themalaysianreserve.com/2020/07/20/covid-19-intensifies-the-urgency-to-accelerate-shipping-masterplan/ [Google Scholar]

- Berti A. Ship Technology; 2020, April. The Impact of Covid-19 on the Global Shipping Sector. [Google Scholar]

- Bethke L. Deutsche Welle; 2020, May 11. The coronavirus crisis has hit tourism in Malaysia hard.https://www.dw.com/en/the-coronavirus-crisis-has-hit-tourism-in-malaysia-hard/a-53392776 [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., Hjort J., Melvin T., Werker E. 2016. Ebola , Jobs and Economic Activity in Liberia. 271–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department Malaysia Marine. 2020. Vessel Traffic in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fisheries Malaysia . 2017. Export and Import of Fishery Commodities.https://www.dof.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/3260 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia . Mohd Uzir Mahidin; 2020. Malaysia economic performance fourth quarter 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Energy Commission . Energy Commission; 2019. The Malaysia Energy Statistics Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- Fish Development Authorities Malaysia . 2016. Annual Market Report.http://www.lkim.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Buku-Laporan-Risikan-2016-Update-17-Julai-2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Foo L.-P., Chin M.-Y., Tan K.-L., Phuah K.-T. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism industry in Malaysia. Curr. Issues Tourism. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1777951. 0(0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . 2020. Novel Coronavirus (COVID 19)http://www.fao.org/2019-ncov/q-and-a/impact-on-fisheries-and-aquaculture/en/ United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes V.L. Springer; 2014. Indonesia's Delimited Maritime Boundaries. [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva K. International Monetary Fund; 2020. Confronting the Crisis: Priorities for the Global Economy.https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/07/sp040920-SMs2020-Curtain-Raiser [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah B.A. 2019, December 21. Maritime Sector in Need of Reform. New Strait Times.https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/columnists/2019/12/549605/maritime-sector-need-reform [Google Scholar]

- Harper J. BBC; 2020. June 2). Asia's Fishermen and Farmers Go Digital during Virus.https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52767227 [Google Scholar]

- Huber C., Finelli L., Stevens W. vol. 218. 2018. (The Economic and Social Burden of the 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa). (1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Transport Workers Federation . ITF; 2020. 300,000 Seafarers Trapped at Sea: Mounting Crew Change Crisis Demands Faster Action from Governments.https://www.itfseafarers.org/en/news/300000-seafarers-trapped-sea-mounting-crew-change-crisis-demands-faster-action-governments [Google Scholar]

- Islam G.M.N., Tai S.Y., Kusairi M.N., Ahmad S., Aswani F.M.N., Muhamad Senan M.K.A., Ahmad A. Community perspectives of governance for effective management of marine protected areas in Malaysia. Ocean Coast Manag. 2017;135:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jomitol J., Payne A.J., Sakirun S., Bural M.O. 2020. The Impacts of Covid-19 to Small Scale Fisheries in Tun Mustapha Park , Sabah , Malaysia ; what Do We Know So Far ? May, 1–13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karim W., Haque A., Anis Z., Ulfy M.A. The movement control order (MCO) for COVID-19 crisis and its impact on tourism and hospitality sector in Malaysia. Int. Tour. Hosp. J. 2020 doi: 10.37227/ithj-2020-02-09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur C.R. 2015. Contribution of the Maritime Sector to Malaysia's Economy and Future Opportunities.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285479599_The_economic_contribution_of_the_marine_economy_Southeast_Asia_leads_the_way [Google Scholar]

- Kizielewicz J. Theoretical considerations on understanding of the phenomenon of maritime tourism in Poland and the world. Zesz. Nauk./Akademia Morska w Szczecinie. 2012;31(103):108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S.J., Yoo S.H., Chang J.I. The role of the maritime industry in the Korean national economy: an input-output analysis. Mar. Pol. 2005;29(4):371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2004.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loske D. The impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics: an empirical analysis in German food retail logistics. Transport. Res. Interdiscipl. Perspect. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaysia National News Agency . 2020, April 27. Sapura Energy Potong Gaji Pengurusan, Kakitangan. Berita Harian.https://www.bharian.com.my/bisnes/korporat/2020/04/682457/sapura-energy-potong-gaji-pengurusan-kakitangan?lmk0a&fbclid=IwAR2yFiOergk5RKUbMY9nZrTE0Q71qHPmefIK7uDs6EM7_Y7VhLtRknn9V7E [Google Scholar]

- Malaysia Shipowners’ Association . Malaysia Shipowners' Association; 2020. Legacy Issues, Pandemic – A Perfect Storm for Shipping Industry.http://masa.org.my/legacy-issues-pandemic-a-perfect-storm-for-shipping-industry/ [Google Scholar]

- Mapjabil J., Rahman B.A., Yusoh M.P., Marzuki M., Zulhalmi M. Tourism attractions and development of Pangkor Island: a study of foreign tourists' perceptions. Tourism Attract. Develop. Pangkor Island: Stud. For. Tourists’ Percept. 2015;11(12):100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Millefiori L.M., Braca P., Zissis D., Spiliopoulos G., Marano S., Willett P.K., Carniel S. 2020. COVID-19 Impact on Global Maritime Mobility. In arXiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of finance . 2020. 11 Laksana Report Implementation of Prihatin.https://www.treasury.gov.my/pdf/Laporan-Pelaksanaan-Pakej-Prihatin-Rakyat-12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . 2020. Current Situation of Covid-19 Pandemic in Malaysia.http://covid-19.moh.gov.my/ [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of tourism arts and culture Malaysia Domestic travel campaign. 2020. https://www.tourism.gov.my/campaigns/view/cc1m

- Mohd Zaideen I.M. The paradox in implementing Ballast Water Management Convention 2004 (BWMC) in Malaysian water. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019;148:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Zaideen I.M., Jeevan J., Saharuddin A.H. Strategies to promote navigational safety and marine environmental protection: with reference to the Straits of Malacca and Singapore. Int. J. E-Navigation Maritime Econ. 2019;11 044–053. [Google Scholar]

- MySejahtera . 2020. MySejahtera.https://mysejahtera.malaysia.gov.my/intro_en/ [Google Scholar]

- Nasralla S., Bousso R. 2020, June 8. Oil Major BP to Cut 15% of Workforce. The Edge Malaysia.https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/oil-major-bp-cut-15-workforce [Google Scholar]

- New Straits Times . 2020. Sunway Launches Campaign to Boost Domestic Tourism.https://www.nst.com.my/business/2020/07/605420/sunway-launches-campaign-boost-domestic-tourism [Google Scholar]

- Park of Malaysia Marine. Marine Park of Malaysia; 2017. Total of Visitors in Marine Park from Year 2000 to Year 2016.http://marinepark.dof.gov.my/files/Total of visitor to marine park from 2000 to year 2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers . 2015. Oil and Gas in Malaysia (Issue April) [Google Scholar]

- Prime Minister Office . Prime Minister Office; 2020. Official Statements of Prime Minister of Malaysia.https://www.pmo.gov.my/2020/03/perutusan-khas-covid-19-18-mac-2020/ [Google Scholar]

- Rusli M.H.B.M. Protecting vital sea lines of communication: a study of the proposed designation of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore as a particularly sensitive sea area. Ocean Coast Manag. 2012;57:79–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saharuddin A.H. National ocean policy - new opportunities for Malaysian ocean development. Mar. Pol. 2001;25(6):427–436. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(01)00027-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheneider A., Domonoske C. Oil Prices, Stocks Plunge after Saudi Arabia Stuns World with Massive Discounts. NPR; 2020. March 8)https://www.npr.org/2020/03/08/813439501/saudi-arabia-stuns-world-with-massive-discount-in-oil-sold-to-asia-europe-and-u- [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger M. 2020. May). What Will Ports Look like after COVID-19? Port Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A.C. The Edge; 2020. April). Allow the Movement of Non-essential Goods Containers to Warehouses. [Google Scholar]

- Solaymani S., Kari F. Poverty evaluation in the Malaysian fishery community. Ocean Coast Manag. 2014;95:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Star . 2020. Sabah Launches Campaign to Boost Domestic Tourism.https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/07/02/sabah-launches-campaign-to-boost-domestic-tourism [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD . 2020. COVID-19 and Maritime Transport: Impact and Responses. Report No. UNCTAD/DTL/TLB/INF/2020/1, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Waiho K., Fazhan H., Ishak S.D., Kasan N.A., Liew H.J., Norainy M.H., Ikhwanuddin M. Potential impacts of COVID-19 on the aquaculture sector of Malaysia and its coping strategies. Aquacult. Rep. 2020;18 doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Shipping Council . 2020. Ports. Global Trade.http://www.worldshipping.org/about-the-industry/global-trade/ports [Google Scholar]

- Worldometers . 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic Live Cases.https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]