Abstract

To explore the relationship between soluble ST2 (sST2) and metabolic syndrome (MetS) and determine whether sST2 levels can predict the presence and severity of MetS. We evaluated 550 consecutive subjects (58.91 ± 9.69 years, 50% male) with or without MetS from the Department of Vascular & Cardiology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University-Affiliated Ruijin Hospital. Serum sST2 concentrations were measured. The participants were divided into three groups according to the sST2 tertiles. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between serum sST2 concentrations and the presence of MetS. Serum sST2 concentrations were significantly higher in the MetS group than in those in the no MetS group (14.80 ± 7.01 vs 11.58 ± 6.41 ng/mL, P < 0.01). Subjects with more MetS components showed higher levels of sST2. sST2 was associated with the occurrence of MetS after multivariable adjustment as a continuous log-transformed variable (per 1 SD, odds ratio (OR): 1.42, 95% CI: 1.13–1.80, P < 0.01). Subgroup analysis showed that individuals with MetS have significantly higher levels of sST2 than those without MetS regardless of sex and age. High serum sST2 levels were significantly and independently associated with the presence and severity of MetS. Thus, sST2 levels may be a novel biomarker and clinical predictor of MetS.

Keywords: soluble ST2, metabolic syndrome, inflammation, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a constellation of metabolic abnormalities comprising central obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM) or hyperglycemia, high triglyceride (TG) levels, and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (1). The prevalence rate of MetS has markedly increased over the past decades due to obesity resulting from widespread overnutrition and an inactive lifestyle. The International Diabetes Federation estimates that MetS affects one-quarter of the world’s adult population (2). Therefore, it has gradually become a major public health concern worldwide. MetS is also considered a chronic systemic inflammatory state and the main promoter of cardiovascular disease and multi-organ dysfunction (3, 4). However, there is limited data for predicting MetS and evaluating its severity.

Growth stimulation expressed gene 2 protein (ST2) was first discovered in 1989 (5) and its only known ligand is IL-33 (6). Two main isoforms of ST2 were found: a transmembrane full-length form (ST2L) and a soluble, secreted form (sST2) (7). The binding of ST2L and IL33 plays a protective role in cardiac stress (8, 9). However, sST2 acts as a decoy receptor of IL33 and inhibits IL33-ST2 signaling. sST2 has been identified as a promising biomarker of cardiovascular disease, especially in heart failure (10, 11, 12, 13).

Increasing evidence shows that MetS shares a similar pathophysiological process with cardiovascular disease, including inflammation, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and insulin resistance (14). Thus, it is reasonable to consider that sST2 levels may be able to indicate early microenvironment abnormalities, such as MetS, that predate the onset of cardiovascular disease. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore the diagnostic and predictive value of sST2 levels for the occurrence of MetS and its severity.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study evaluated 550 consecutive subjects from the Department of Vascular & Cardiology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University-Affiliated Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai, China. The inclusion criteria were older than 18 years with no coronary heart disease, heart failure, malignant tumor and autoimmune disease. The diagnosis of MetS was made after enrollment.

This study was approved by the institutional review committee of Ruijin Hospital (Ethics Committee reference number: 2016-019), and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in this study.

Data collection and measures

Baseline data, including medical history, health status, and family history, were obtained via face-to-face interviews. Height, weight, and waist circumference were measured using standard measurements. BMI was calculated using weight and height (kg/m2). Blood pressure was measured in the left arm using a calibrated aneroid sphygmomanometer, with the participant in a seated position after at least 5 min of rest.

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected and centrifuged at 1500 g at 4°C for 15 min. The serum obtained by centrifugation was rapidly stored at –80°C. Echocardiography was conducted within 1 week from the collection of peripheral venous blood samples. Fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, TG, HDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and other routine biochemical parameters were measured using an automatic analyzer. Serum sST2 was measured using the venous serum samples via an ELISA Kit (DST200, R&D) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Echocardiography

All subjects underwent two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. After finding the standard long axial section of the left ventricle, M-mode echocardiography was used to measure the left ventricular end systolic diameter, left ventricular end diastolic diameter, left atrial diameter (LAD), aortic dimension, interventricular septal thickness (IVT), and left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWT). Simpson’s biplane method was used to measure left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Definition of MetS

The most widely accepted and clinically used definitions of MetS were established by the World Health Organization, National Cholesterol Education Program – Third Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP-ATPIII), and International Diabetes Federation. These three definitions differ only in detail. Here, we used the definition of NCEP-ATPIII for MetS, and waist circumference (WC) was adopted as a factor that is more suitable for the Chinese population. Criteria of MetS were as follows (15): (i) Central obesity: WC ≥ 90 cm in men or ≥ 80 cm in women; (ii) TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L or treatment of this lipid abnormality; (iii) HDL-C < 1.03 mmol/L in men or < 1.30 mmol/L in women; (iv) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or taking antihypertensive medications; and (v) fasting blood glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L, previously diagnosed type 2 DM, or taking antidiabetic medications including oral antidiabetic agents or insulin. (Criteria for type 2 DM: symptoms of diabetes + plasma glucose at any time ≥ 11.1 mmol/L or fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or oral glucose tolerance test 2-h ≥ 11.1 mmol/L.)

Specifically, subjects meeting three or more of the five criteria above were considered to have MetS while those meeting one or two or zero of the five criteria could be excluded from MetS diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± s.d., whereas categorical variables were summarized as numbers and percentages. Variables with a skewed distribution were log-transformed to make them fit a normal distribution. Independent Student’ s t-test, one-way ANOVA test, the chi-square test and linear trend test were used to evaluate the differences among groups, as appropriate. Pearson correlation analysis was used to describe the correlations between sST2 levels and metabolic features. Subsequently, univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between serum sST2 levels and the risk for MetS. For these models, we used (i) log-transformed sST2 level as a continuous variable analyzed per SD and (ii) tertiles of sST2 levels analyzed both as an ordinal variable and as categorical data. Subgroup analyses by age (≥60/<60 years) and sex (male/female) were also conducted. All statistical tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0. A two-sided P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Subject characteristics

Overall, 275 (50.0%) subjects were male. The mean age was 58.91 ± 9.69 years, and the mean sST2 level was 12.88 ± 6.84 ng/mL. The baseline subject characteristics are shown in Table 1 by tertiles of serum sST2 concentrations. There were trends across tertiles of higher levels of BMI, WC, systolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and triglyceride levels, along with lower levels of HDL. In addition, subjects with higher sST2 levels had higher concentrations of white blood count, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and NT-proBNP, along with poorer liver and renal function. Among the subjects in the highest and lowest tertile of sST2, 59.0 and 43.2% were male, respectively. The LDL-C and LVEF levels were not significantly different among the patients in the three tertiles.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all subjected divided by serum levels of ST2.

| < 8.97 ng/mL | 8.97–13.70 ng/mL | ≥13.70 ng/mL | P value | P for liner trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 183 | 184 | 183 | ||

| Age, years | 56.74 ± 9.00 | 60.08 ± 8.91 | 59.89 ± 10.74 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Male, sex | 79 (43.2) | 88 (47.8) | 108 (59.0) | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.42 ± 2.95 | 24.28 ± 3.64 | 24.67 ± 3.73 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 80.00 ± 9.94 | 82.60 ± 11.95 | 84.55 ± 13.20 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Current smoking | 30 (16.4) | 43 (23.4) | 54 (29.5) | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol use | 19 (10.4) | 28 (15.2) | 28 (15.3) | 0.29 | 0.17 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125.25 ± 15.98 | 129.67 ± 18.55 | 134.49 ± 18.36 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.31 ± 10.29 | 75.10 ± 11.51 | 76.52 ± 12.21 | 0.44 | 0.31 |

| Family history | 16 (8.7) | 13 (7.1) | 14 (7.7) | 0.19 | 0.70 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | 44 (24.0) | 81 (44.0) | 110 (60.1) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (6.6) | 26 (14.1) | 26 (14.2) | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1 (0.5) | 9 (4.9) | 14 (7.7) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Laboratory measurements | |||||

| WBC (×109) | 5.94 ± 1.77 | 6.43 ± 2.01 | 6.61 ± 2.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 131.92 ± 15.18 | 131.77 ± 15.81 | 135.07 ± 16.74 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Platelet (×109) | 191.51 ± 56.56 | 187.83 ± 60.94 | 187.62 ± 61.64 | 0.78 | 0.53 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.01 ± 0.91 | 5.20 ± 0.95 | 5.26 ± 1.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.74 ± 0.61 | 5.93 ± 0.79 | 6.11 ± 0.96 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 24.15 ± 21.97 | 22.58 ± 15.84 | 27.68 ± 22.47 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.71 ± 3.27 | 38.66 ± 3.41 | 38.57 ± 4.05 | 0.93 | 0.72 |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 74.68 ± 17.83 | 77.39 ± 16.37 | 81.48 ± 20.51 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| eGFRMDRD (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 82.74 ± 17.66 | 80.48 ± 22.03 | 79.47 ± 21.01 | 0.29 | 0.13 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 302.45 ± 80.47 | 336.30 ± 93.09 | 355.21 ± 106.11 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.42 ± 0.89 | 1.69 ± 1.10 | 1.81 ± 1.30 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.42 ± 0.88 | 4.39 ± 1.07 | 4.23 ± 1.06 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.61 ± 0.71 | 2.58 ± 0.91 | 2.52 ± 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.30 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.24 ± 0.37 | 1.19 ± 0.31 | 1.08 ± 0.30 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 0.32 ± 0.52 | 0.49 ± 1.34 | 0.43 ± 0.69 | 0.17 | 0.23 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 2.05 ± 2.22 | 3.95 ± 3.59 | 4.80 ± 3.76 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| NTproBNP (pg/mL) | 114.90 ± 162.25 | 165.17 ± 213.96 | 186.86 ± 272.67 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Echocardiography parameters | |||||

| Aortic dimension (mm) | 32.51 ± 3.05 | 32.95 ± 3.64 | 33.36 ± 3.60 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| LAD (mm) | 36.97 ± 4.16 | 38.36 ± 4.38 | 38.82 ± 4.57 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 47.40 ± 4.29 | 47.95 ± 4.67 | 48.30 ± 4.76 | 0.17 | 0.06 |

| LVESD (mm) | 29.69 ± 3.56 | 30.10 ± 3.88 | 30.62 ± 4.24 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| IVT (mm) | 9.12 ± 1.28 | 9.41 ± 1.58 | 9.60 ± 1.40 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| LVPWT (mm) | 8.80 ± 1.10 | 9.01 ± 1.36 | 9.23 ± 1.32 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| LVEF (%) | 66.81 ± 4.80 | 66.44 ± 4.89 | 65.89 ± 5.22 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

Data are presented as mean ± s.d. or n (%).

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CCB, calcium channel blockers; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; IVT, interventricular septal thickness; LAD, left atrial diameter; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end systolic diameter; LVPWT, left ventricular posterior wall thickness; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; WBC, white blood cell.

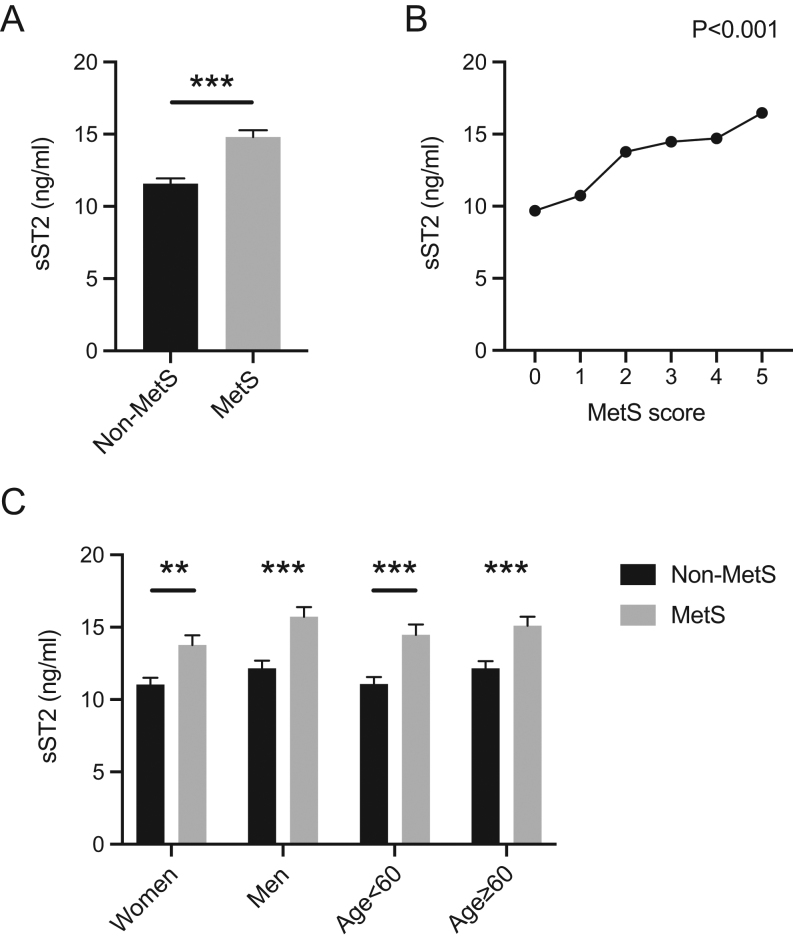

sST2 levels were associated with the presence of MetS

sST2 concentrations were significantly higher in the MetS group than that in the no MetS group (14.80 ± 7.01 vs 11.58 ± 6.41 ng/mL, P < 0.01, Fig. 1A). Subjects with higher MetS scores (i.e. more components of MetS) showed higher levels of sST2 (Fig. 1B). As shown in Table 2, sST2 was associated with the presence of MetS after multivariable adjustment as a continuous log-transformed variable (per 1 SD, odds ratio (OR): 1.42, 95% CI: 1.13–1.80, P < 0.01). Analysis of the tertiles of sST2 also showed that the adjusted risk of MetS was higher in subjects in the highest tertile than that in the subjects in the lowest tertile (OR: 2.52, 95% CI: 1.45–4.39, P < 0.01, Ptrend < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Expression of serum soluble ST2 (sST2) levels in the different groups. (A) Comparison of sST2 expression between the metabolic syndrome (MetS) group and the no MetS group. (B) Correlation analysis between sST2 levels and the number of MetS components. (C) sST2 expression by age group (<60 years and ≥60 years) and sex (male and female). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis for MetS in all subjects.

| Unadjusted OR | P value | Adjusted OR for model 1 | P value | Adjusted OR for model 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log ST2 per s.d. | 1.75 (1.45–2.11) | <0.01 | 1.67 (1.35–2.07) | <0.01 | 1.42 (1.13–1.80) | <0.01 |

| ST2 tertiles | 2.01 (1.61–2.51) | <0.01 | 1.88 (1.47–2.42) | <0.01 | 1.58 (1.20–2.08) | <0.01 |

| Tertile 1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Tertile 2 | 2.53 (1.61–3.97) | <0.01 | 2.23 (1.35–3.68) | <0.01 | 1.68 (0.98–2.89) | 0.06 |

| Tertile 3 | 4.14 (2.63–6.49) | <0.01 | 3.58 (2.16–5.93) | <0.01 | 2.52 (1.45–4.39) | <0.01 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender and BMI. Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, BMI, alcohol use, smoke, creatinine, LDL-C, hsCRP and NTproBNP. Continuous variables were entered per 1 SD.

hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; OR, odds ratio.

Subgroup analysis by age and sex

Subgroup analysis showed that in both men and women and in subjects aged <60 years and ≥60 years, MetS patients exhibited significantly higher levels of sST2 than those without MetS (Fig. 1C). Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses of the relationship between sST2 and MetS according to age and sex are shown in Table 3. After full adjustment, patients in the highest group of serum sST2 levels had significantly higher risk than those in the lowest group regardless of age and sex. Furthermore, as a continuous variable, sST2 retained significant predictive value particularly in the older group (adjusted OR: 1.83, 95% CI: 1.31–2.56, P < 0.01) and in men (adjusted OR: 1.80, 95% CI: 1.29–2.49, P < 0.01). This indicated that serum sST2 levels were independently associated with the risk for MetS in all subjects, especially in men and in subjects older than 60 years.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis for MetS in subjected divided by age and gender.

| Unadjusted OR | P value | Adjusted OR for model 1 | P value | Adjusted OR for model 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 60 years | ||||||

| Log ST2 per s.d. | 1.74 (1.35–2.25) | <0.01 | 1.62 (1.21–2.17) | <0.01 | 1.28 (0.94–1.76) | 0.12 |

| ST2 tertiles | 2.13 (1.57–2.90) | <0.01 | 1.99 (1.40–2.82) | <0.01 | 1.52 (1.04–2.24) | 0.03 |

| Tertile 1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Tertile 2 | 3.12 (1.66–5.84) | <0.01 | 2.86 (1.40–5.83) | <0.01 | 1.96 (0.90–4.23) | 0.09 |

| Tertile 3 | 4.59 (2.46–8.54) | <0.01 | 3.93 (1.94–7.98) | <0.01 | 2.36 (1.09–5.12) | 0.03 |

| Age ≥ 60 years | ||||||

| Log ST2 per s.d. | 1.75 (1.32–2.32) | <0.01 | 1.83 (1.32–2.54) | <0.01 | 1.83 (1.31–2.56) | <0.01 |

| Tertiles | 1.87 (1.35–2.59) | <0.01 | 1.80 (1.25–2.60) | <0.01 | 1.87 (1.28–2.75) | <0.01 |

| Tertile 1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Tertile 2 | 1.99 (1.02–3.87) | 0.05 | 1.70 (0.82–3.52) | 0.15 | 1.67 (0.79–3.54) | 0.18 |

| Tertile 3 | 3.55 (1.82–6.91) | <0.01 | 3.22 (1.54–6.74) | <0.01 | 3.45 (1.60–7.44) | <0.01 |

| Women | ||||||

| Log ST2 per s.d. | 1.64 (1.26–2.13) | <0.01 | 1.58 (1.19–2.10) | <0.01 | 1.25 (0.92–1.70) | 0.16 |

| Tertiles | 1.90 (1.39–2.61) | 0.01 | 1.86 (1.31–2.64) | <0.01 | 1.45 (1.00–2.12) | 0.05 |

| Tertile 1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Tertile 2 | 3.58 (1.93–6.63) | <0.01 | 3.06 (1.57–5.96) | <0.01 | 2.20 (1.08–4.48) | 0.03 |

| Tertile 3 | 3.63 (1.89–6.97) | <0.01 | 3.41 (1.68–6.93) | <0.01 | 2.12 (1.00–4.59) | 0.05 |

| Men | ||||||

| Log ST2 per s.d. | 1.86 (1.41–2.45) | <0.01 | 1.87 (1.35–2.58) | <0.01 | 1.80 (1.29–2.49) | <0.01 |

| Tertiles | 2.12 (1.54–2.91) | <0.01 | 1.98 (1.36–2.87) | <0.01 | 1.91 (1.31–2.78) | <0.01 |

| Tertile 1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Tertile 2 | 1.69 (0.87–3.29) | 0.13 | 1.69 (0.77–3.73) | 0.19 | 1.46 (0.66–3.24) | 0.35 |

| Tertile 3 | 4.29 (2.27–8.11) | <0.01 | 4.08 (1.90–8.77) | <0.01 | 3.49 (1.63–7.44) | <0.01 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender and BMI. Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, BMI, alcohol use, smoke, creatinine, LDL-C, hsCRP and NTproBNP. Continuous variables were entered per 1 s.d.

hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; OR, odds ratio.

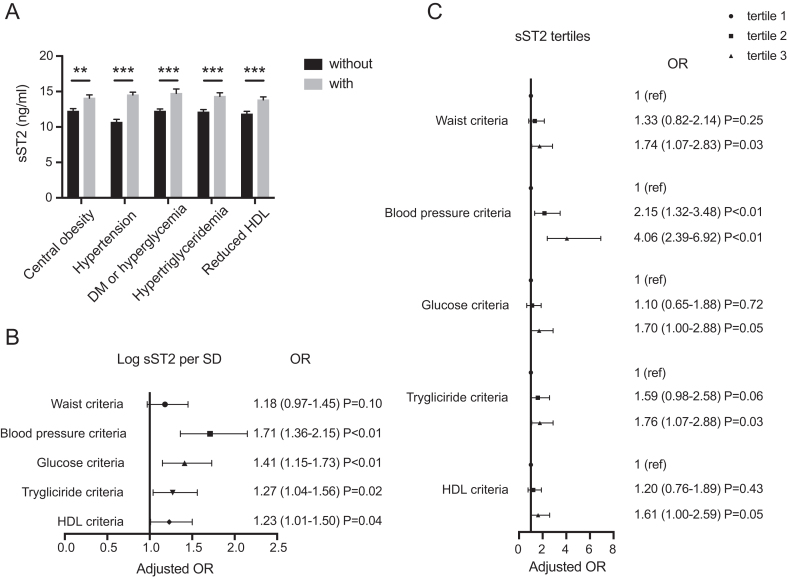

Relationship between sST2 and MetS components

We further analyzed the relationship between sST2 and each MetS component. Subjects with central obesity, hypertension, DM or hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and lower HDL had significantly higher concentrations of serum sST2 than those without it (Fig. 2A). After adjustment for the full model including age, sex, BMI, alcohol use, smoking, and levels of creatinine, LDL-C, hsCRP, and NT-proBNP (model 3), the association between sST2 and each specific disease remained statistically significant (Fig. 2B and C). The ORs corresponding to a 1 s.d. increase of log-transformed sST2 level for the presence of hypertension, DM, hypertriglyceridemia, and lower HDL were 1.71 (95% CI: 1.36–2.15, P < 0.01), 1.41 (95% CI: 1.15–1.73, P < 0.01), 1.27 (95% CI: 1.04–1.56, P = 0.02), and 1.23 (95% CI: 1.01–1.50, P = 0.04), respectively. Subjects in the highest level of sST2 had a significantly higher risk of meeting each diagnostic criterion of MetS than those in the lowest group, especially the blood pressure criteria (OR: 4.06, 95% CI: 2.39–6.92, P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Relationship between soluble ST2 (sST2) and the components of metabolic syndrome (MetS). (A) Serum sST2 levels were compared between patients grouped by individual MetS components. (B) Full model Logistic regression for log-transformed sST2 and each component of MetS. (C) Full model logistic regression for sST2 tertiles and each component of MetS. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (age, sex, BMI, alcohol use, smoking, and levels of creatinine, LDL-C, hsCRP, and NT-proBNP were adjusted).

Discussion

MetS shares a similar pathophysiological process with cardiovascular disease, and thus it is reasonable to consider that sST2 levels, as a novel biomarker of cardiovascular disease, may also be a biomarker of MetS. In this study, serum sST2 levels increased with an increase in the number of metabolic abnormalities. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses demonstrated that high sST2 level was an independent risk factor for the presence of MetS, especially in men and in subjects older than 60 years. Thus, serum sST2 may be a biomarker for MetS. To our best knowledge, this study is the first to provide evidence on a correlation between serum sST2 levels and the presence and severity of MetS in the Chinese population.

Several studies have demonstrated that a continuous low-grade chronic systemic inflammatory state is an important pathophysiological feature of MetS, and some inflammatory factors are associated with it (16). Soluble ST2, as an important serum biomarker, has been shown to be involved in some inflammation-associated diseases. For example, during the acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lungs, the serum levels of sST2 significantly increased with the development of inflammation (17). Serum sST2 levels were also found to be higher in asthma, which is a typical inflammatory disease, and was strongly correlated with the severity of asthma exacerbation (18). However, unlike the above single-system inflammation-associated diseases, inflammation in MetS arise from adipocytes, macrophages, and impaired endothelial cells and involves multiple systems and metabolic processes throughout the body (16).

sST2 was found to be associated with the inflammatory process of several cells, tissues, and organs (19). In this study, we observed a consistent increase in sST2 and hsCRP, which is considered a sensitive marker of inflammation. Thus, we speculated that sST2 could indicate the inflammation level in patients with MetS, in many ways influencing multiple aspects. Further, we found high sST2 levels in patients with central obesity. Monocyte-derived macrophages residing in adipose tissue can secrete various proinflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1. Therefore, obesity itself is a state of inflammation, which may be reflected or influenced by sST2. Moreover, hypertension, DM, and dyslipidemia are also regarded as chronic inflammation processes involving multiple organs (20, 21, 22). ST2 itself may participate in the pathophysiological process of each component of MetS by affecting the inflammatory and immune response, thus taking part in the occurrence and development of MetS as well as reflecting its severity.

It is generally believed that sST2 functions through the IL33-ST2 axis, that is, it binds to IL33 as bait and blocks IL33 activation of downstream signaling pathways. However, whether the IL33-ST2 axis confers pro- or anti-inflammation effects depends on the disease type. For example, in an ovalbumin-induced murine model of asthma, ST2-deficient mice developed attenuated airway inflammation and IL-5 production. Meanwhile, IL-33 administration exacerbated airway inflammation in wild-type mice (23). In another inflammation-associated disease, IL-33 treatment lowered the development of atherosclerosis and macrophage accumulation in ApoE-/- mice fed with a high-fat diet. This effect can be blocked by sST2, thus leading to a larger atherosclerosis plaque (24). This characteristic may be due to the activation of different downstream pathways. The inflammatory process in MetS involves multiple organs and systems. Therefore, the role of sST2 in MetS may not be simply summarized as proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory, despite its relationship with disease severity. As such, further studies are warranted.

Each component of MetS has the potential to affect the endothelium and cause vascular dysfunction or disrupt vascular homeostasis. In turn, endothelial dysfunction can aggravate MetS. Vascular dysfunction is a key contributor to the pathogenesis of MetS. Our research shows that sST2 is strongly correlated with high systolic blood pressure but not diastolic blood pressure, consistent with the findings of a previous study (25). This result indicates that sST2 may correlate with vascular stiffness and compliance. Both ST2 and IL-33 are expressed and act in human endothelial cells (26, 27). As such, sST2, which is derived from ST2 and interacts with IL-33, may also play an important role in vascular biology.

Furthermore, the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is another reason for endothelial dysfunction and metabolic disorders in MetS (28, 29). Fat cell and macrophage accumulation can increase ROS production and fatty acid concentration during hyperlipidemia. This in turn inhibits the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation, and the production of ROS also increases sharply. Excessive ROS can oxidize various lipid components, such as oxidized LDL, which plays an important role in endothelial dysfunction and the development of MetS. Studies have shown that ROS can activate the IL33/ST2 axis and promote the release of IL33, which can in turn inhibit ROS production (8, 30). Therefore, the ST2-IL33 axis plays a protective role in endothelial dysfunction caused by oxidative stress, while sST2 functions in the opposite direction.

Abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism is an important characteristic of MetS. Studies have shown that sST2 is associated with glucose and lipid metabolism. In type 2 diabetes patients with normal blood glucose tolerance, circulating sST2 levels were significantly higher and were significantly associated with fasting blood glucose and HbA1c (31). Bariatric surgery in severely obese diabetes patients improves metabolic status, and circulating sST2 levels decrease with improvements in liver function and lipid metabolism markers (32). In line with these findings, we found that sST2 is correlated with DM and dyslipidemia. The liver is the main organ for glucolipid metabolism, and we also observed worse liver function in patients with the highest sST2 tertile. However, the role of the IL33-ST2 pathway in liver metabolism remains controversial (33, 34), and the involvement of sST2 in glucose and lipid metabolism abnormalities needs to be further studied.

On the other hand, our present study demonstrated that sST2 levels were associated with cardiac hypertrophy, as indicated by the relationship of sST2 with LAD, IVT and LVPWT, which is in accordance with another study of patients with MetS (35). However, cardiac hypertrophy may only be a secondary outcome of hypertension and inflammation, so evidence for a direct link between sST2 and cardiac hypertrophy is lacking.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it is a small-scale and single-center study. Therefore, we could not completely avoid the influence of confounding factors on our findings. Second, we did not detect the serum level of IL-33, and thus it is unclear whether sST2 functions through IL33. Third, because of the cross-sectional design, we cannot determine the causal relationship between MetS and sST2, thus needing further investigation, especially basic experiments. Moreover, studies with a larger sample size are needed to validate the diagnostic value of sST2 levels in MetS.

Conclusion

The present study found that high serum sST2 levels were significantly and independently associated with the presence and severity of MetS. Subjects with more MetS components showed higher levels of sST2. Thus, sST2 levels may be a novel biomarker of MetS.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81670352 and 81970327 to R T, 82000368 to Q F).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all the enrolled subjects for their patience and understanding.

References

- 1.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ.The metabolic syndrome. Lancet 2005. 365 1415–1428. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(0566378-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti G, Zimmet P & Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome - a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Medicine 2006. 23 469–480. ( 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin YH, Zhang RC, Hou LB, Wang KJ, Ye ZN, Huang T, Zhang J, Chen X, Kang JS.Distribution and clinical association of plasma soluble ST2 during the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2016. 118 140–145. ( 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.06.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik S, Wong ND, Franklin SS, Kamath TV, L’Italien GJ, Pio JR, Williams GR.Impact of the metabolic syndrome on mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in United States adults. Circulation 2004. 110 1245–1250. ( 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140677.20606.0E) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klemenz R, Hoffmann S, Werenskiold AK.Serum- and oncoprotein-mediated induction of a gene with sequence similarity to the gene encoding carcinoembryonic antigen. PNAS 1989. 86 5708–5712. ( 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5708) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li Xet al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity 2005. 23 479–490. ( 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergers G, Reikerstorfer A, Braselmann S, Graninger P, Busslinger M.Alternative promoter usage of the Fos-responsive gene Fit-1 generates mRNA isoforms coding for either secreted or membrane-bound proteins related to the IL-1 receptor. EMBO Journal 1994. 13 1176–1188. ( 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06367.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT.IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2007. 117 1538–1549. ( 10.1172/JCI30634) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seki K, Sanada S, Kudinova AY, Steinhauser ML, Handa V, Gannon J, Lee RT.Interleukin-33 prevents apoptosis and improves survival after experimental myocardial infarction through ST2 signaling. Circulation: Heart Failure 2009. 2 684–691. ( 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.873240) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, Hurwitz S, Tominaga S, Rouleau JL, Lee RT.Identification of serum soluble ST2 receptor as a novel heart failure biomarker. Circulation 2003. 107 721–726. ( 10.1161/01.cir.0000047274.66749.fe) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aimo A, Vergaro G, Passino C, Ripoli A, Ky B, Miller WL, Bayes-Genis A, Anand I, Januzzi JL, Emdin M.Prognostic value of soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. JACC: Heart Failure 2017. 5 280–286. ( 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aimo A, Vergaro G, Ripoli A, Bayes-Genis A, Pascual Figal DA, de Boer RA, Lassus J, Mebazaa A, Gayat E, Breidthardt Tet al. Meta-analysis of soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 and prognosis in acute heart failure. JACC: Heart Failure 2017. 5 287–296. ( 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimpo M, Morrow DA, Weinberg EO, Sabatine MS, Murphy SA, Antman EM, Lee RT.Serum levels of the interleukin-1 receptor family member ST2 predict mortality and clinical outcome in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004. 109 2186–2190. ( 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127958.21003.5A) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tune JD, Goodwill AG, Sassoon DJ, Mather KJ.Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Translational Research 2017. 183 57–70. ( 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.01.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith Jr SCet al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005. 112 2735–2752. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutherland JP, Mckinley B, Eckel RH.The metabolic syndrome and inflammation. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders 2004. 2 82–104. ( 10.1089/met.2004.2.82) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tajima S, Oshikawa K, Tominaga S, Sugiyama Y.The increase in serum soluble ST2 protein upon acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2003. 124 1206–1214. ( 10.1378/chest.124.4.1206) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe M, Nakamoto K, Inui T, Sada M, Honda K, Tamura M, Ogawa Y, Yokoyama T, Saraya T, Kurai Det al. Serum sST2 levels predict severe exacerbation of asthma. Respiratory Research 2018. 19 169. ( 10.1186/s12931-018-0872-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griesenauer B, Paczesny S.The ST2/IL-33 axis in immune cells during inflammatory diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2017. 8 475. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00475) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy CG, Goulopoulou S, Webb RC.Paying the toll for inflammation. Hypertension 2019. 73 514–521. ( 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11782) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oguntibeju OO.Type 2 diabetes mellitus, oxidative stress and inflammation-examining the links. International Journal of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Pharmacology 2019. 11 45–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Libby P.Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002. 420 868–874. ( 10.1038/nature01323) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Murphy G, Russo RC, Stolarski B, Garcia CC, Komai-Koma M, Pitman N, Li Y, Niedbala Wet al. IL-33 induces antigen-specific IL-5+ T cells and promotes allergic-induced airway inflammation independent of IL-4. Journal of Immunology 2008. 181 4780–4790. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4780) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AM, Xu D, Asquith DL, Denby L, Li Y, Sattar N, Baker AH, McInnes IB, Liew FY.IL-33 reduces the development of atherosclerosis. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2008. 205 339–346. ( 10.1084/jem.20071868) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho JE, Larson MG, Ghorbani A, Cheng S, Vasan RS, Wang TJ, Januzzi Jr JL.Soluble ST2 predicts elevated SBP in the community. Journal of Hypertension 2013. 31 1431–1436; discussion 1436. ( 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283611bdf) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moussion C, Ortega N, Girard JP.The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘alarmin’? PLoS ONE 2008. 3 e3331. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartunek J, Delrue L, Van Durme F, Muller O, Casselman F, De Wiest B, Croes R, Verstreken S, Goethals M, de Raedt Het al. Nonmyocardial production of ST2 protein in human hypertrophy and failure is related to diastolic load. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2008. 52 2166–2174. ( 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinen I, Shimabukuro M, Yamakawa K, Higa N, Matsuzaki T, Noguchi K, Ueda S, Sakanashi M, Takasu N.Vascular lipotoxicity: endothelial dysfunction via fatty-acid-induced reactive oxygen species overproduction in obese Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Endocrinology 2007. 148 160–165. ( 10.1210/en.2006-1132) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang EH, Vanhoutte PM.Endothelial dysfunction: a strategic target in the treatment of hypertension? Pflugers Archiv 2010. 459 995–1004. ( 10.1007/s00424-010-0786-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida M, Anderson EL, Squillace DL, Patil N, Maniak PJ, Iijima K, Kita H, O'Grady SM.Oxidative stress serves as a key checkpoint for IL-33 release by airway epithelium. Allergy 2017. 72 1521–1531. ( 10.1111/all.13158) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardellini M, Rizza S, Casagrande V, Cardolini I, Ballanti M, Davato F, Porzio O, Canale MP, Legramante JM, Mavilio Met al. Soluble ST2 is a biomarker for cardiovascular mortality related to abnormal glucose metabolism in high-risk subjects. Acta Diabetologica 2019. 56 273–280. ( 10.1007/s00592-018-1230-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demyanets S, Kaun C, Kaider A, Speidl W, Prager M, Oravec S, Hohensinner P, Wojta J, Rega-Kaun G.The pro-inflammatory marker soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 (ST2) is reduced especially in diabetic morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Cardiovascular Diabetology 2020. 19 26. ( 10.1186/s12933-020-01001-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pejnovic N, Jeftic I, Jovicic N, Arsenijevic N, Lukic ML.Galectin-3 and IL-33/ST2 axis roles and interplay in diet-induced steatohepatitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2016. 22 9706–9717. ( 10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9706) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao Y, Liu Y, Yang M, Guo X, Zhang M, Li H, Li J, Zhao J.IL-33 treatment attenuated diet-induced hepatic steatosis but aggravated hepatic fibrosis. Oncotarget 2016. 7 33649–33661. ( 10.18632/oncotarget.9259) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celic V, Majstorovic A, Pencic-Popovic B, Sljivic A, Lopez-Andres N, Roy I, Escribano E, Beunza M, Melero A, Floridi Fet al. Soluble ST2 levels and left ventricular structure and function in patients with metabolic syndrome. Annals of Laboratory Medicine 2016. 36 542–549. ( 10.3343/alm.2016.36.6.542) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a