Abstract

Background:

Vascular risk factors and lack of formal education may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Objective:

To determine the contribution of vascular risk factors and education to the risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and to estimate the risk for conversion from MCI to AD.

Methods:

This door-to-door survey was performed by an Arab-speaking team in Wadi Ara villages in Israel. All consenting residents aged≥ 65 years were interviewed for medical history and underwent neurological and cognitive examinations. Individuals were cognitively classified as normal (CN), MCI, AD, vascular dementia (VD) or unclassifiable. MCI patients were re-examined at least one year later to determine conversion to AD. The contributions of age, gender, school years and vascular risk factors to the probability of conversion were estimated using logistic regression models.

Results:

Of the 906 participants, 297 (33%) had MCI and 95 (10%) had AD. Older age (p=0.0008), female gender (p=0.023), low schooling (p<0.0001), and hypertension (p=0.0002) significantly accounted for risk of MCI vs. CN, and diabetes was borderline (p=0.051). The risk of AD vs. CN was significantly associated with age (p<0.0001), female gender (p<0.0001), low schooling (p=0.004) and hypertension (p=0.049). Of the 231 subjects with MCI that were re-examined, 65 converted to AD.

Conclusions:

In this population, age, female gender, lack of formal education and hypertension are risk factors for both AD and MCI. Conversion risk from MCI to AD could be estimated as a function of age, time interval between examinations and hypertension.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, prevalence, Arab, risk factors, neuroepidemiology, aging

Introduction

The fact that vascular risk factors contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) beyond female gender, low education and APOE status is nowadays well recognized [1, 2]. In this report we examine the relationships between age, gender, education and vascular risk factors and the risk of MCI and AD and focus on the conversion from MCI to AD in an elderly Arab population with a particularly high prevalence of dementia [3, 4], and low levels of schooling [5]. Moreover, the population is homogenous with respect to ethnicity (Arabic) and religion (Muslim), minimal alcohol consumption [6], obesity (3 out of 4 women by the age of 60) [7], rural environment and low socio-economic status. Given the high rates of consanguinity and increased prevalence of autosomal recessive diseases, several genetic studies of AD have been performed in this population [8–10]. While the APOE4 allele is rare [8], the reported association between polymorphisms in the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene and AD [9] adds further support to the growing evidence linking vascular risk factors to cognitive decline.

Studies on cognitive decline in Arabic populations are reportedly sparse. We have been working on dementia in Arabic populations in northern Israel for many years [1, 3, 4, 11–13]. One specific difficulty encountered is the lack of formal school education in the vast majority of women. Considering the high illiteracy rate, we used clinical assessment and not MMSE cutoff scores that may have generated bias due to the lack of formal schooling especially in women. In a subsequent follow-up phase we analyzed the contribution of vascular risk factors to the conversion rate from MCI to AD on the background of low level of education.

Materials and Methods

Study population and setting

This is a door-to-door observational study with follow-up in Wadi-Ara, an Arab community of 81,400 inhabitants located in northern Israel. All Wadi-Ara residents aged ≥ 65 years on prevalence day (January 1st, 2003) were eligible (n = 2,067, according to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics). There were no other selection criteria. Individuals were first ascertained between January 2003 and December 2008 and were subsequently re-evaluated after ≥ 1 year. The last subject evaluation was performed in 2012. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Sheba Medical Center according to guidelines from the Israel Ministry of Health and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University Hospitals of Cleveland, Case Western Reserve University, Boston and Louisville University. All participants signed a written consent form in Arabic. The interviewer read the consent form to illiterate subjects who then signed by fingerprinting with the index finger of his/her dominant hand.

Subject Evaluation

This work is part of an epidemiological and genetic study of aging-related brain disorders in Wadi-Ara. [3, 14–16] The research team included a neurologist (M.M.) and an academic nurse (A.A.), both fluent Arabic speakers, who examined all subjects in their homes. All subjects resided either with their spouse or in the home of a close relative. None lived alone and none of the subjects were institutionalized, as is the norm in this population. Information about education (school years), medical and family history, medication use, daily activities (social, personal, occupational and recreational), behavior, cognitive abilities and changes in the above was obtained by a nurse-led structured interview of the subject and a close relative. During the second visit, the neurologist performed a complete neurological examination including the motor part of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale in all subjects. All subjects had medical insurance as required by law in Israel (the National Health Insurance Law, 1995) and regularly attended their family physician’s medical practice.

The presence of concomitant diseases and vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and cardiac disease) was determined by the history, informant history and review of relevant documentation such as medical reports and drug prescriptions. When prescriptions of medications used to lower blood pressure, lipids or antidiabetics were present informants were asked accordingly about the presence of the relevant risk factors. Blood pressure was measured on each visit. Hypertension was defined according to the Joint National Committee (JNC) 7 report criteria for hypertension (i.e. systolic pressure ≥140mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥90mmHg) [17].

Cognitive Instruments

Cognitive instruments were used as described elsewhere. [3] Arabic translations of the Minimental State Examination (MMSE; maximum score = 30) and the Brookdale Cognitive Screening Test (BCST; maximum score = 24) were used. The BCST was developed at the Brookdale Institute of Gerontology, Jerusalem, Israel, for use in populations with high illiteracy rates. It includes items on orientation, language, memory, attention, naming, abstraction, concept formation, attention, praxis, calculation, right-left orientation and visuospatial orientation. The Arabic versions of the MMSE and the BCST have been validated, and norms have been published. Since the MMSE involves several tasks that are dependent on literacy, these items scored 0 in subjects with no formal education. A highly significant correlation between MMSE and BCST scores in normal subjects has previously been reported by our group (r = 0.85; p <0.0001). This correlation was of the same magnitude for men (r = 0.82) and women (r = 0.85; p < 0.0001 for both) [5].

Subject Classification

All subjects were classified as healthy cognitively normal (CN), AD, MCI, vascular dementia (VD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) dementia, other dementia or not classifiable according to accepted criteria [18–20] and as described in detail elsewhere [3]. Three neurologists (M.M., R.S. and R.I.) reviewed the results of the field examination of each subject in a bimonthly conference and formed a consensus diagnosis. Since MMSE and BCST scores are strongly dependent on education in both genders in this population we did not use cutoff scores for cognitive classification [5].

Study design

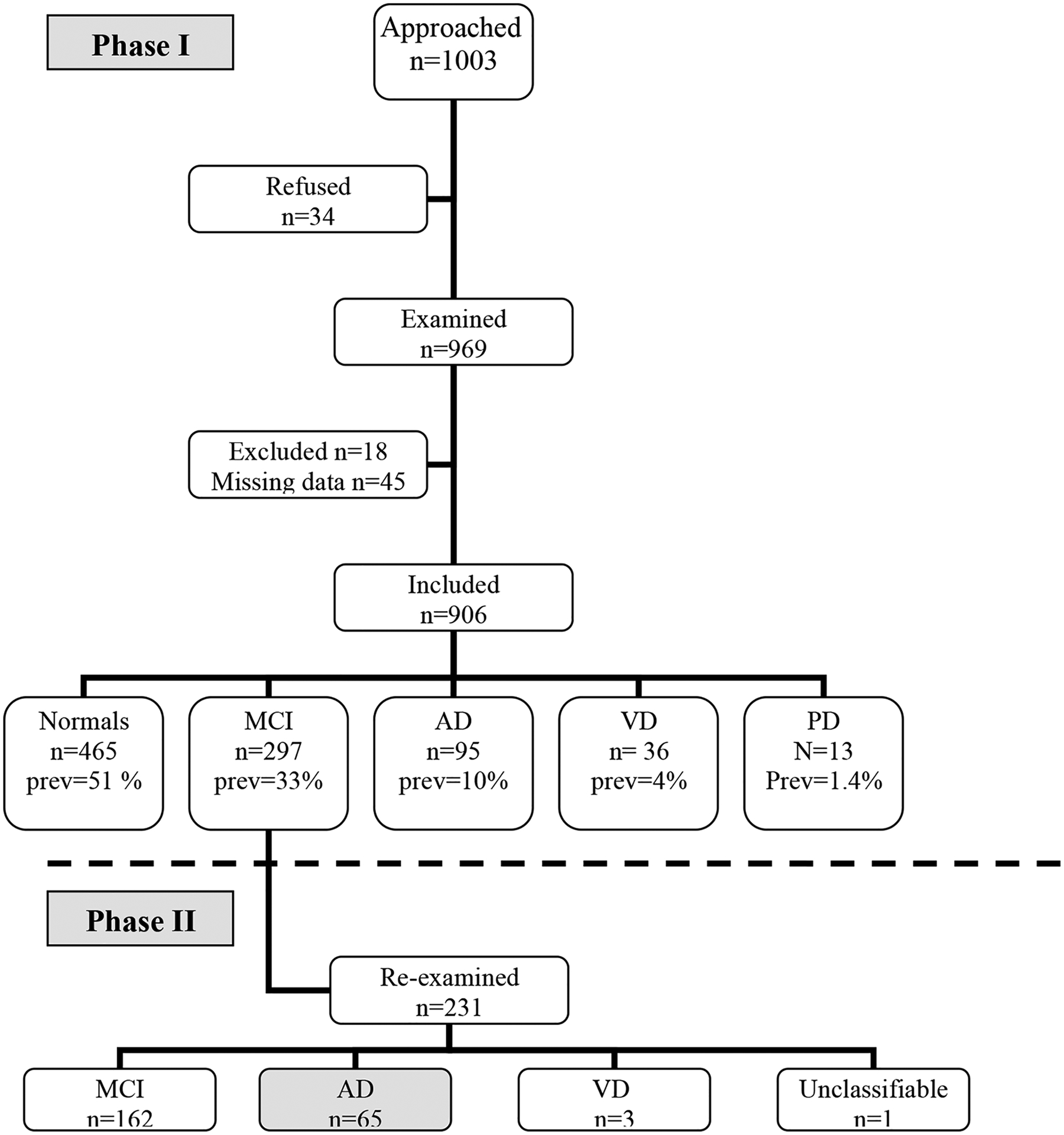

The study was conducted in two phases. In Phase 1, we classified all subjects that agreed to participate as CN, MCI, AD, VD or other. In Phase 2, all subjects diagnosed as MCI were re-examined after ≥1 year using the cognitive classifications described above. Causes for exclusion were reviewed to account for newly developed confounding comorbidities (e.g. end-stage renal failure or stroke).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Statistical Analysis Software). In Phase 1, we examined the effect of age, gender, years of schooling (illiteracy was defined as zero school years - no schooling) and vascular risk factors on the risk of AD vs. CN and MCI vs. CN separately using stepwise logistic regression.

In Phase 2, MCI subjects were re-examined after ≥ 1 year to determine the conversion to AD. We estimated the probability of conversion to AD using a stepwise logistic regression model with age, time interval between the first and second examination, gender, years of schooling and vascular risk factors. Subjects with missing data for any of the explanatory variables were excluded.

The logistic regression model is given by:

where X1,…Xk are the explanatory variables and P is the predicted probability that the subject converts to AD. Once the parameters are estimated, one can use the above model and solve for P as follows:

Results

A total of 1,003 subjects aged ≥65 years were approached (Figure 1). Thirty-four subjects (3.4%) refused, and 63 additional subjects (6%) were excluded for the following reasons: severe systemic disease (n=9), aphasia (n=3), hydrocephalus (n=1), mistaken data (n=3) and incomplete data on vascular risk factors (n=47). A total of 906 subjects were included in the study, of those 36 were diagnosed as VD and 13 as PD. The final analysis included 857 subjects with normal cognition (CN), MCI and AD whose demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. One-half of the subjects were either demented or cognitively impaired. The prevalences of AD and MCI were estimated to be 10% and 33%, respectively. The majority of cognitively impaired were women (comprising 59 % of MCI and 63 % of AD), while only 35 % of CN subjects were women. The mean age of AD patients (78±8 years) was higher than the mean ages of MCI patients (73±6 years) and cognitively normal (CN) subjects (71±6 years).

Figure 1 – Study population and design.

AD=Alzheimer’s disease, MCI=Mild Cognitive Impairment, VD=Vascular Dementia, prev=Prevalence

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and vascular risk factors

| Normal | MCI | AD | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 465 | 297 | 95 | 857 |

| Mean age (SD) | 71 (6) | 73 (6) | 78 (8) | 73 (6) |

| Males (%) | 303 (65) | 122 (41) | 26 (27) | 451 (53) |

| Zero school years (%) | 159 (34) | 196 (66) | 75 (78) | 430 (50) |

| - Male (* %) | 44 (28) | 43 (22) | 11 (15) | 98 (23) |

| - Female (* %) | 115 (72) | 153 (78) | 64 (85) | 332 (77) |

| Hypertension | 235 (51) | 195 (66) | 58 (61) | 488 (57) |

| Diabetes | 161 (33) | 131 (44) | 38 (40) | 330 (39) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 166 (35) | 109 (37) | 23 (24) | 297 (35) |

MCI=Mild cognitive impairment, AD=Alzheimer’s disease, VD=Vascular dementia,

percentage out of subjects with zero school years

Age (p<0.0001, OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.15–1.26), female gender (p<0.0001, OR=3.89, 95% CI 1.87–8.13), and hypertension (p=0.049, OR=1.75, 95% CI 0.99–3.08) were associated with AD risk (Table 2), whereas a higher number of school years decreased the risk of AD (p=0.0044, OR=0.81, 95% CI 0.70–0.94). The effect of each of these variables was above and beyond that of the others

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for

| Variable | OR | 95 % CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD vs. controls | |||

| Hypertension | 1.75 | 0.99–3.08 | p=0.049 |

| Age | 1.2 | 1.15–1.26 | p<0.0001 |

| Female gender | 3.89 | 1.87–8.13 | p<0.0001 |

| Education | 0.81 | 0.70–0.94 | p=0.0044 |

| MCI vs. controls | |||

| Hypertension | 1.73 | 1.24–2.43 | p=0.0002 |

| Diabetes | 1.40 | 0.99–1.96 | p=0.051 |

| Age | 1.07 | 1.04–1.10 | p=0.0008 |

| Female gender | 1.51 | 1.03–2.23 | p=0.023 |

| Education | 0.83 | 0.77–0.88 | p<0.0001 |

| Conversion from MCI to AD | |||

| Hypertension | 2.72 | 1.31–5.66 | p=0.0064 |

| Age | 1.18 | 1.10–1.27 | p<0.0001 |

| Interval (months) | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | p=0.0043 |

All interactions were found statistically non-significant. OR=Odd’s ratio, CI=Confidence interval

The risk of MCI also increased with age (p=0.0008, OR=1.07, 95% CI 1.04–1.10), female gender (p=0.023, OR=1.51, 95% CI 1.03–2.23), hypertension (p=0.0002, OR=1.73, 95% CI 1.2–2.43) and decreased with higher number of school years (p<0.0001, OR=0.83, 95% CI 0.77–0.88). Diabetes increased the risk of MCI in a borderline way (p=0.051, OR=1.40, 95% CI 0.99–1.96). The effect of each of these variables was above and beyond that of the others for MCI as it was for AD.

Of the 231 subjects with MCI who were re-examined in Phase 2, 65 converted to AD, three developed VD, 162 remained MCI (three had missing data), and one was unclassifiable. Thus analysis included 224 MCI patients who either remained MCI (n=159) or developed AD (n=65). Stepwise regression analysis showed that age (p<0.0001, OR=1.18, 95% CI 1.10–1.27), the time interval between examinations (p=0.004, OR=1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.04) and hypertension (p=0.0064, OR=2.72, 95% CI 1.31–5.66) predicted conversion from MCI to AD (Table 2). Diabetes, gender and education level were not significant predictors of conversion. A formula for the risk of converting to AD was calculated as follows:

(1=hypertensive, 2=normotensive) where P is the probability for conversion to AD. For example, the risk for converting to AD for a 90 years old hypertensive person after a year (12 months) is calculated as follows:

And hence the probabilty of converting is P=1/(1+exp(−1.41))=0.8 (80%).

Similarly, the risk for a normotensive person of the same age and after same time interval would be Y=12.95−0.02*12−0.168*90+1*2=−0.41 and the probability is P=0.6 (60%).

A classification representing the true state of nature (conversion to AD/ remaining MCI) observed in the cohort, versus the classification recommended by the model, are shown in Table 3. That is, for each person the model calculates the probability to convert to AD. If this probability is greater than 0.5, the person is classified into “convert”. The model predicted a correct decision in 75% of cases. A false positive decision (model predicted conversion to AD while in reality the subject remained MCI) occurred in 36% of cases and false negative in 23 % (model predicted remaining MCI, while to subject converted to AD in reality). Hence the specificity of the model was 93% and its sensitivity 32%.

Table 3.

Classification representing the true state of nature and the decision taken by the model

| Model Decision/ True state | Correct remain MCI | Correct convert to AD | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision remain MCI | TN=147 | FN=44 | TN+FN=191 |

| Decision convert to AD | FP=12 | TP=21 | FP+TP=33 |

| Total | TN+FP=159 | FN+TP=65 | 224 |

The columns represent the true state of nature and the rows represent the decision taken by the model.

TP=true positive, TN=True negative, FP=False positive, FN=False negative

Correct decisions percent=(TP+TN)/total= 75%

Sensitivity=TP/(TP+FN)=proportion of correct decisions to convert out of total correct conversions= 32% [29]

Specificity=TN/(TN+FP)=proportion of correct decisions not to convert out of total no conversions =93% [29]

False positive percent=FP/(TP+FP)=36%, False negative percent=FN/(TN+FN)=23%.

Discussion

We found that hypertension is a risk factor for AD and MCI and also for the conversion from MCI to AD beyond the contribution of age, female gender and low schooling. We established a formula that estimates the risk for conversion to AD given age, time interval since MCI diagnosis and hypertension.

We observed that the prevalence of AD was almost three times higher in women compared to men. Female gender has been found to be a risk factor for AD in both developed and underdeveloped countries [21, 22]. In agreement with another large study [23], our results suggest that illiteracy does not entirely account for the higher rate of AD in women. We did not find an effect of gender on the conversion from MCI to AD. A study on conversion from MCI to AD in Brazil also found that education separately, besides age and sex, did not influence progression to AD [24]. A recent large study evaluating the incidence of cognitively impaired not demented and the conversion to AD in a population with a mean 12 years of schooling found that men had significantly lower conversion rates [23].

We have previously reported that the prevalence of VD in this community is similar to that reported for other low literacy cohorts [3]. An unanswered question that remains relates to the possible effect treatment of hypertension and the period of life at which this may, if at all, be influential for preventing cognitive decline or conversion to AD. It was suggested that the contribution of hypertension to the risk for AD is especially prominent in individuals with questionable dementia rather than those with intact cognitive or clinically overt dementia [25].

The major strengths of this study include the ascertainment methodology (door-to-door with no recruitment bias), low refusal rate and cognitive data from a follow-up exam for the estimation of conversion from MCI to AD. Several caveats are also noted. Diagnoses were not supported by neuroimaging data or autopsy. Also, cognitive screening tests as a sole measure can lead to misclassification of cognitively normal but illiterate subjects as demented. To avoid this bias, diagnoses in this study were established by taking into account clinical findings rather than scores from cognitive screening. The use of an instrument like the AD8, demonstrated to be culturally neutral might have contributed transparency to the clinical categorization determination [26, 27]. An Arabic version of this instrument would be useful for future studies. An additional caveat was our limited ability to evaluate the effect of education on risk of MCI and AD in women because most of the women were illiterate. Previous studies have shown that the combination of comparatively invasive and expensive adjunctive tests including volumetric MRI and FDG-PET scans, measurement of AD-related biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid, and APOE genotype can predict conversion at an accuracy rate of 74% [28]. Our model including clinical and demographic risk factors was able to predict correctly the conversion from MCI to AD in 75 % of subjects with a specificity as high as 93%, but low sensitivity. Although the routine use of such a formula with low specificity (32%) has limited value, it may aid in diagnosis based primarily on cognitive tests, particularly among persons with little or no formal schooling. The work supports the importance of efforts to control hypertension and increase literacy of women.

Acknowledgment:

Supported by the NIH RO1 AG017173 and Martin Kellner’s Research Fund, American Technion Society.

References

- [1].Israeli-Korn SD, Masarwa M, Schechtman E, Abuful A, Strugatsky R, Avni S, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R (2010) Hypertension increases the probability of Alzheimer’s disease and of mild cognitive impairment in an Arab community in northern Israel. Neuroepidemiology 34, 99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Honig LS, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R (2005) Aggregation of vascular risk factors and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology 65, 545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Afgin AE, Massarwa M, Schechtman E, Israeli-Korn SD, Strugatsky R, Abuful A, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R (2012) High prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease in arabic villages in northern Israel: impact of gender and education. J Alzheimers Dis 29, 431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bowirrat A, Treves TA, Friedland RP, Korczyn AD (2001) Prevalence of Alzheimer’s type dementia in an elderly Arab population. Eur J Neurol 8, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Inzelberg R, Schechtman E, Abuful A, Masarwa M, Mazarib A, Strugatsky R, Farrer LA, Green RC, Friedland RP (2007) Education effects on cognitive function in a healthy aged Arab population. Int Psychogeriatr 19, 593–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Baron-Epel O, Haviv-Messika A, Tamir D, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Green M (2004) Multiethnic differences in smoking in Israel: pooled analysis from three national surveys. Eur J Public Health 14, 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kalter-Leibovici O, Atamna A, Lubin F, Alpert G, Keren MG, Murad H, Chetrit A, Goffer D, Eilat-Adar S, Goldbourt U (2007) Obesity among Arabs and Jews in Israel: a population-based study. Isr Med Assoc J 9, 525–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bowirrat A, Friedland RP, Chapman J, Korczyn AD (2000) The very high prevalence of AD in an Arab population is not explained by APOE epsilon4 allele frequency. Neurology 55, 731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Meng Y, Baldwin CT, Bowirrat A, Waraska K, Inzelberg R, Friedland RP, Farrer LA (2006) Association of polymorphisms in the Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene with Alzheimer disease in an Israeli Arab community. Am J Hum Genet 78, 871–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rogaeva E, Meng Y, Lee JH, Gu Y, Kawarai T, Zou F, Katayama T, Baldwin CT, Cheng R, Hasegawa H, Chen F, Shibata N, Lunetta KL, Pardossi-Piquard R, Bohm C, Wakutani Y, Cupples LA, Cuenco KT, Green RC, Pinessi L, Rainero I, Sorbi S, Bruni A, Duara R, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R, Hampe W, Bujo H, Song YQ, Andersen OM, Willnow TE, Graff-Radford N, Petersen RC, Dickson D, Der SD, Fraser PE, Schmitt-Ulms G, Younkin S, Mayeux R, Farrer LA, St George-Hyslop P (2007) The neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 39, 177–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Inzelberg R, Afgin AE, Massarwa M, Schechtman E, Israeli-Korn SD, Strugatsky R, Abuful A, Kravitz E, Farrer LA, Friedland RP (2013) Prayer at midlife is associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline in Arabic women. Curr Alzheimer Res 10, 340–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Bowirrat A, Waraska K, Korczyn A, Baldwin CT (2003) Genetic and environmental epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease in arabs residing in Israel. J Mol Neurosci 20, 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bowirrat A, Friedland RP, Farrer L, Baldwin C, Korczyn A (2002) Genetic and environmental risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease in Israeli Arabs. J Mol Neurosci 19, 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Glik A, Masarwa M, Abuful A, Deeb A, Strugatsky R, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R (2009) Essential tremor might be less frequent than Parkinson’s disease in North Israel Arab villages. Mov Disord 24, 119–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Inzelberg R, Mazarib A, Masarwa M, Abuful A, Strugatsky R, Friedland RF (2006) Essential tremor prevalence is low in Arabic villages in Israel: door-to-door neurological examinations. J Neurol 253, 1557–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Israeli-Korn SD, Massarwa M, Schechtman E, Strugatsky R, Avni S, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R (2010) Mild cognitive impairment is associated with mild parkinsonian signs in a door-to-door study. J Alzheimers Dis 22, 1005–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr., Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr., Roccella EJ (2003) The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 289, 2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL, Eastwood R, Gauthier S, Tuokko H, McDowell I (1997) Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 349, 1793–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34, 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Andersen K, Launer LJ, Dewey ME, Letenneur L,Ott A, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, Kragh-Sorensen P, Baldereschi M, Brayne C, Lobo A, Martinez-Lage JM, Stijnen T, Hofman A (1999) Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia: The EURODEM Studies. EURODEM Incidence Research Group. Neurology 53, 1992–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S (1998) The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55, 809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Godinho C, Camozzato AL, Onyszko D, Chaves ML (2012) Estimation of the risk of conversion of mild cognitive impairment of Alzheimer type to Alzheimer’s disease in a south Brazilian population-based elderly cohort: the PALA study. Int Psychogeriatr 24, 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Letenneur L, Gilleron V, Commenges D, Helmer C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF (1999) Are sex and educational level independent predictors of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease? Incidence data from the PAQUID project. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 66, 177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wysocki M, Luo X, Schmeidler J, Dahlman K, Lesser GT, Grossman H, Haroutunian V, Beeri MS (2012) Hypertension is associated with cognitive decline in elderly people at high risk for dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 20, 179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Galvin JE, Roe CM, Coats MA, Morris JC (2007) Patient’s rating of cognitive ability: using the AD8, a brief informant interview, as a self-rating tool to detect dementia. Arch Neurol 64, 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Galvin JE, Roe CM, Morris JC (2007) Evaluation of cognitive impairment in older adults: combining brief informant and performance measures. Arch Neurol 64, 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Young J, Modat M, Cardoso MJ, Mendelson A, Cash D, Ourselin S (2013) Accurate multimodal probabilistic prediction of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage Clin 2, 735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schechtman E (2002) Odds ratio, relative risk, absolute risk reduction, and the number needed to treat--which of these should we use? Value Health 5, 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]