Abstract

Background:

The burden of mental illness among the scheduled tribe (ST) population in India is not known clearly.

Aim:

The aim was to identify and appraise mental health research studies on ST population in India and collate such data to inform future research.

Materials and Methods:

Studies published between January 1980 and December 2018 on STs by following exclusion and inclusion criteria were selected for analysis. PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase, Sociofile, Cinhal, and Google Scholar were systematically searched to identify relevant studies. Quality of the included studies was assessed using an appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies and Critical Appraisal Checklist developed by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Studies were summarized and reported descriptively.

Results:

Thirty-two relevant studies were found and included in the review. Studies were categorized into the following three thematic areas: alcohol and substance use disorders, common mental disorders and sociocultural aspects, and access to mental health-care services. Sociocultural factors play a major role in understanding and determining mental disorders.

Conclusion:

This study is the first of its kind to review research on mental health among the STs. Mental health research conducted among STs in India is limited and is mostly of low-to-moderate quality. Determinants of poor mental health and interventions for addressing them need to be studied on an urgent basis.

Keywords: India, mental health, scheduled tribes

INTRODUCTION

Mental health is a highly neglected area particularly in low and middle-income countries (LMIC). Data from community-based studies showed that about 10% of people suffer from common mental disorders (CMDs) such as depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints.[1] A systematic review of epidemiological studies between 1960 and 2009 in India reported that about 20% of the adult population in the community are affected by psychiatric disorders in the community, ranging from 9.5 to 103/1000 population, with differences in case definitions, and methods of data collection, accounting for most of the variation in estimates.[2]

The scheduled tribes (ST) population is a marginalized community and live in relative social isolation with poorer health indices compared to similar nontribal populations.[3] There are an estimated 90 million STs or Adivasis in India.[4] They constitute 8.6% of the total Indian population. The distribution varies across the states and union territories of India, with the highest percentage in Lakshadweep (94.8%) followed by Mizoram (94.4%). In northeastern states, they constitute 65% or more of the total population.[5] The ST communities are identified as culturally or ethnographically unique by the Indian Constitution. They are populations with poorer health indicators and fewer health-care facilities compared to non-ST rural populations, even when within the same state, and often live in demarcated geographical areas known as ST areas.[4]

As per the National Family Health Survey, 2015–2016, the health indicators such as infant mortality rate (IMR) is 44.4, under five mortality rate (U5MR) is 57.2, and anemia in women is 59.8 for STs – one of the most disadvantaged socioeconomic groups in India, which are worse compared to other populations where IMR is 40.7, U5MR is 49.7, and anemia in women among others is 53.0 in the same areas.[6] Little research is available on the health of ST population. Tribal mental health is an ignored and neglected area in the field of health-care services. Further, little data are available about the burden of mental disorders among the tribal communities. Health research on tribal populations is poor, globally.[7] Irrespective of the data available, it is clear that they have worse health indicators and less access to health facilities.[8] Even less is known about the burden of mental disorders in ST population. It is also found that the traditional livelihood system of the STs came into conflict with the forces of modernization, resulting not only in the loss of customary rights over the livelihood resources but also in subordination and further, developing low self-esteem, causing great psychological stress.[4] This community has poor health infrastructure and even less mental health resources, and the situation is worse when compared to other communities living in similar areas.[9,10]

Only 15%–25% of those affected with mental disorders in LMICs receive any treatment for their mental illness,[11] resulting in a large “treatment gap.”[12] Treatment gaps are more in rural populations,[13] especially in ST communities in India, which have particularly poor infrastructure and resources for health-care delivery in general, and almost no capacity for providing mental health care.[14]

The aim of this systematic review was to explore the extent and nature of mental health research on ST population in India and to identify gaps and inform future research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

We searched major databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase, Sociofile, Cinhal, and Google Scholar) and made hand searches from January 1980 to December 2018 to identify relevant literature. Hand search refers to searching through medical journals which are not indexed in the major electronic databases such as Embase, for instance, searching for Indian journals in IndMed database as most of these journals are not available in major databases. Physical search refers to searching the journals that were not available online or were not available online during the study years. We used relevant Medical Subject Heading and key terms in our search strategy, as follows: “Mental health,” “Mental disorders,” “Mental illness,” “Psychiatry,” “Scheduled Tribe” OR “Tribe” OR “Tribal Population” OR “Indigenous population,” “India,” “Psych*” (Psychiatric, psychological, psychosis).

Inclusion criteria

Studies published between January 1980 and December 2018 were included. Studies on mental disorders were included only when they focused on ST population. Both qualitative and quantitative studies on mental disorders of ST population only were included in the analysis.

Exclusion criteria

Studies without any primary data and which are merely overviews and commentaries and those not focused on ST population were excluded from the analysis.

Data management and analysis

Two researchers (SD and SK) initially screened the title and abstract of each record to identify relevant papers and subsequently screened full text of those relevant papers. Any disagreements between the researchers were resolved by discussion or by consulting with an adjudicator (PKM). From each study, data were extracted on objectives, study design, study population, study duration, interventions (if applicable), outcomes, and results. Quality of the included studies was assessed, independently by three researchers (SD, SK, and AS), using Critical Appraisal Checklist developed by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP).[15] After a thorough qualitative assessment, all quantitative data were generated and tabulated. A narrative description of the studies is provided in Table 1 using some broad categories.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Study location/community | Objectives | Study design/type | Sample size, participants and methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee et al., 1986[47] | District of Nadia West Bengal Santal |

Rate and pattern of mental disorders | Cross-sectional study | 205 families in urbanized tribal community by the method of door-to-door survey | Depression was common. Very low prevalence rate of Neurotic illness, epilepsy and mental retaliation. Married individuals were affected more than the unmarried ones. Males had a slightly higher rate to mental morbidity. The population showed a general tendency of greater vulnerability to mental illness with advancing age |

| Nandi et al., 1992[41] | West Bengal | Assess the change if any in the extent and pattern of mental morbidity in the urbanized group in comparison to the rural group of the same tribe | Cross-sectional study | Urban Santals (771) | Urbanization had little effect on the total mental morbidity. But stress-dependent disorders were more common in the urban tribe |

| Santal | Rural Santals (653) Household survey |

||||

| Ganguly et al., 1995[16] | Western Rajasthan Meena and other tribes |

Understand the health issues related to the use of opium | Qualitative | Traditional opium users (200) from six villages, ethnographic information of opium use | Majority of the addicts were between 40 and 60 years of age. Consumption starts with 10 g/day. Some were hard-core users who consumed around 100 g a day or 250-300 g |

| Aparajitaet al., 1996[36] | Ganjam district, Orissa | Assessing social support network and the satisfaction of the children’s needs belonging to high and low sociocultural status families | Cross-sectional | Disadvantaged group (300) and advantaged group (150) and equal number from both genders from the 8th, 9th, and 10th grades were taken as samples | Children from advantaged socio-cultural environment were found to have health and enriching family climate, whereas children from socioculturally disadvantaged environment were deprived of getting necessary interpersonal and intra family support. In spite of getting negative support and responsibilities from their families, the need satisfaction rate was found to be more in disadvantaged children. Girls received more negative response from their family members than the boys. This paper confirmed the continuous positive social support in satisfying children’s needs in the Indian social system |

| Mixed Population | Structured questionnaire (35 item questionnaire) | ||||

| Chaturvedi et al., 2013[18] | Changlang district, Arunachal Pradesh | Assesses the types of substance use | Cross-sectional | Households (1092) respondents, age ≥10 years (5135) | Prevalence of opium use was more among males. Usage was higher in higher altitudes |

| Tangsa, Singpho, Khamti, and Tutsa | Structured pretested questionnaire | ||||

| Prabhakar and Manoharan, 2005[32] | Tamil Nadu Malayali and Lambadi |

Evaluate health system to examine the health status of the target population | Cross-sectional | Villages (21), respondents (2785), Examine the health system from the perspective of the base hospital | Gender and age susceptibility patterns revealed specific age intervals for mental health disorders |

| Sushila et al., 2005[25] | Southern Rajasthan | Explore factors responsible for physical and mental discomfort; availability of health care facilities; preferred system to cure such problems | Qualitative | Households (156), Bhil, households of village Madri and tribal households from village Jamun | Services of traditional healers are used by the people in all kind of physical and mental discomforts |

| Bhils | The perceptions of illness, socio-cultural beliefs, and practices regarding illness Mixed-methods study |

||||

| Hackett et al., 2007[42] | Wayanad, Kerala | Examine association between CMD, anemia, malnutrition, and physical symptoms | Cross-sectional | Tribes (721) seeking treatment at Swami Vivekananda medical mission | CMD was not associated with anemia, malnutrition and physical symptoms |

| NR | Quantitative data collection by interview and estimation of hemoglobin from blood samples | ||||

| Giri et al., 2007[40] | Jharkhand | Study the sociodemographic and clinical profile of cases through a retrospective case record analysis of tribal populations and compare it with nontribals | Cross-sectional | All the patients registered (1752) in the three community outreach centers (Jonha, Khunti, Saraikella-kharsawan) from November 2005 to April 2006 were included in the study | About half of the cases from both groups are of age-group 20-39 years with gradual decline. Psychiatric morbidity among males was more than females in both tribals and nontribals. Patients with epilepsy were higher in tribal group. Tribals were more irregular with substantial number of dropouts |

| Mixed population of tribals and non tribals | Sociodemographic profile and service utilization were recorded by reviewing the case records of the participants during that time | ||||

| Sobhanjan and Mukhopadhyay, 2007[26] | Sikkim | Examine if perceived stress affects BP, lipids and obesity | Cross-sectional | Healthy volunteers (398) (age ≥20 years, urban males: 100; urban females (100); rural males (103) rural females (95) | Urban Bhutias experienced perceived stress to a significantly higher extent (mean±SD of PSSI value: male: 0.48±0.06, female: 0.48±0.07) than that of rural Bhutias (male: 0.22±0.07, females: 0.20±0.05) |

| Bhutia | Structured questionnaire | ||||

| Chowdhury et al. 2008[37] | Sundarban Delta Not mentioned |

Examine the extent and impact of human-animal conflicts vis-a-vis psychosocial stressors and mental health of the affected people | Cross-sectional | 3082 households (Satjelia, 1572, Lahiripur, 1512), were surveyed among the mixed population of tribals and nontribals Survey, FGD, IDIs, and medical clinics |

During the last 15 years, 111 persons (male 83, female 28) became victims of animal attacks, viz., tiger (82%), crocodile (10.8%), and shark (7.2%), of which 73.9% died. In 94.5% cases, the conflict took place in and around the SRF during livelihood activities. Tracking of 66 widows, resulted from these conflicts, showed that majority of them (51.%) were either disabled or in a very poor health condition, 40.9% were in extreme economic stress and only 10.6% remarried. 1 widow committed suicide and 3 attempted suicide. A total of 178 persons (male 82, female 96) attended the community mental health clinics. Maximum cases were major depressive disorder (14.6%), followed by somatoform pain disorder (14.0%), posttraumatic stress disorder-animal attack related (9.6%), and adjustment disorder (9%). 11.2% cases had a history of deliberate self-harm attempt, of which 55% used pesticides |

| Tripathy et al. 2010[35] | Jharkhand and Odisha | Assess the effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Intervention (2457) and control (2235). Women between the age group of 15 and 49 years | NMR was 32% lower in intervention clusters adjusted for clustering, stratification and baseline differences during the 3 year period and 45% lower in 2 and 3 years. No significant effect on maternal depression was noted |

| Not mentioned | Primary outcome was to see the reduction in neonatal mortality rate and maternal depression scores after implementation of strategies to address the above-mentioned problems in the intervention arm compared to the control arm | ||||

| Mohindra et al., 2011[19] | Waynad District, Kerala/ | Understand the reasons, concerns, and consequences of consumption of alcohol | Qualitative | Households (393), age >15 years | Paniyas reported consumption of alcohol as a problem and is increasing among younger men |

| Paniya | FGDs and semi-structured interviews | Reasons for consumption Easily available, produced illicitly in some colonies, employers using this as a strategy to attract Paniyas to work. The other reasons are range of socioeconomic consequences that are rooted in historic oppression and social discrimination |

|||

| Sreeraj et al., 2012[20] | Ranchi, Jharkhand | Examine the reasons for alcohol intake, belief about addiction, their effect on the severity of addiction in people with different ethnic background | Cross-sectional | Tribal (40) and nontribal (20) communities | Patients from both the groups had a similar age of onset of substance intake, duration of intake in a dependence pattern, and duration of incubation from first intake to intake in dependence pattern. In spite of these similarities problems related to alcohol were more in tribals. Social enhancement, to cope with distressing emotions and peer pressure were some of the reasons for alcohol intake |

| NR | Structured questionnaire through an interview | ||||

| Yalsangi, 2012[34] | Trivandrum, Kerala Paniya Kattunaicken Bettakurumba Mullukurumba Irula |

Assess the community health program run in a tribal area in Nilgiris | Cross-sectional- Program Evaluation | 218, ST with an age of ≥25 and more were selected. No upper limit. Mixed-methods study | The intervention area had better awareness score (5.13±2.27) than that of control area (1.57±2.82) |

| Manimunda et al. 2012[23] | The Andaman and Nicobar Islands | Estimate the prevalence and determinants of tobacco use and nicotine dependency | Cross-sectional | 18,018, both ST and non-ST population with an age group of ≥14 years | Prevalence of current tobacco use was 48.9%. Tobacco chewing alone was prevalent in 40.9% of the population. One-tenth (9%) of the males were nicotine dependent, while it was 3% in females. Three-fourths of the tobacco users initiated use of tobacco before reaching 21 years of age. Age, current use of alcohol, poor educational status, marital status, socioeconomic groups, and comorbidities were the main determinants of tobacco use and nicotine dependence |

| Nicobarese tribe, Ranchi tribes | Structured questionnaire FTND test was used to estimate nicotine dependence |

||||

| Diwan, 2012[28] | Ranchi, Jharkhand Not mentioned |

Examine the main and interaction effects of ethnicity, marital status, and stress on mental health of tribal school teachers | Cross-sectional study | 400, female school teachers of Ranchi town (160 tribal and 160 non tribal) GHQ-12, Stress scale was used to collect the data |

Out of the three factors namely stress, marital status, and ethnicity, only ethnicity was found to produce main effect on mental health. Neither second-order interaction nor third-order interaction was found to be significant |

| Diwan., 2012[46] | Ranchi, Jharkhand | Know the impact of gender, socio-economic status, and age upon the mental health of tribal factory workers | Cross-sectional | 400, tribal female workers from different factories | Out of the three factors namely gender, socio economic status, and age, gender was found to produce main effect on mental health |

| Not mentioned | Personal data schedule, GHQ-12 | ||||

| Singh et al., 2013[24] | Roing and Anini districts, Arunachal Pradesh | Evaluate psychological traits of Idu Mishmi tribes to validate earlier report of high suicide rates | Cross-sectional, qualitative | 218, unrelated school children aged 13-19 years, family members of unrelated individuals aged 19-85 years who had committed suicide | Suicide attempt was higher in Idu Mishmi population (14.22%) than urban population (0.4%-4.2%). Females were at higher risk. Depression (8.26%) was comparable with earlier reports, whereas anxiety syndrome (6.42%), alcohol abuse (36.24%), and eating disorder such as binge eating (6.42%) and bulimia nervosa (1.38%) were also recorded in the population |

| Idu Mishmi | Data collection done using mixed-methods approach | ||||

| Chaturvedi et al., 2013[18] | Arunachal Pradesh Tangsa, Singpho, Khamti and Tutsa |

Estimate prevalence of opium use among tribes, association between sociodemographic factors and opium use | Cross-sectional | Age >15 years (3421), participated in substance survey, secondary data were used which were collected in a previous survey which assessed the types of substance use | Higher prevalence of opium use in men (10.6%) compared to women (2.1%). Opium use was significantly higher among Singpho and Khamti tribes. Variation seen according to age, educational level, occupation, marital status, and religion of the respondents |

| Raina et al., 2013[43] | Bharmour, Himachal Pradesh | Systematic methods for developing cognitive screening instrument for tribals | Cross-sectional | 50, 60-75+ age groups, trained sample randomly picked | Modifications and testing of modified version of MMSE questionnaire resulted in an effective customized screening tool exclusive for Brahmouri population |

| Gaddi | Different phases for development of MMSE questionnaire relevant for Bharmouri population | ||||

| Longkumer et al., 2013[29] | Nagaland | Explore the existing knowledge and attitudes regarding mental disorders and see whether formal education has any relationship with their attitudes toward such disorders | Cross-sectional | Christian males (500) and (272) females in the age above 21 years | A great majority recognized mental health problem in the case vignette but used general terms such as psychosocial problem/mental problem/mental illness. Majority attributed the problem to psychosocial problems and chose a psychiatrist/psychologist over other options. However, a considerable number of participants reported evil spirit possession as the cause of mental disorders and preferred seeking for divine intervention as a treatment mode |

| Nagas/Ao Naga Tribes | A brief instruction, respondent’s personal identification chart, a case vignette and a questionnaire based on the vignette | ||||

| Raina et al., 2014[44] | Himachal Pradesh | Know the prevalence of dementia and to generate a hypothesis on the differential distribution across populations | Cross-sectional | 2000, 60 years and above age, Two-phase study; screening and clinical phase | No case of dementia reported in tribal population |

| Not mentioned | Screening - urban, rural, and migrant populations using HMSE questionnaire For tribal population modified version of MMSE was used Clinical evaluation- involved a psychiatrist and public health expert |

||||

| Nizamie et al., 2015[31] | Jharkhand NR |

Develop an effective health-care delivery model for epilepsy to reduce treatment gap in a rural community | Cross-sectional | 114,068 6 health workers, traditional practitioners (267 faith healers and qualified practitioners, local practitioners) Involved training, awareness campaigns, diagnosis, treatment delivery, follow-up, and free medication |

213 patients enrolled in a study completed 12 months treatment leaving 75% seizure free. The model was successful |

| Nimgaonkar and Menon, 2015[33] | Tamil Nadu Bettakurumba, Mullukurumba and other ST |

Improve the health-care delivery through task shifting | Feasibility study | 542, from 184 villages | Low cost task shifting was successfully implemented. Patients were well treated and they volunteered to increase the acceptance |

| Ozer, 2015[39] | Ladakh | To assess how two groups of Ladakhi college students navigate through different degrees of exposure to acculturation and how this affects their mental health | Mixed methods study (cross-sectional) | 292 - quantitative and 12 - qualitative | Students with less acculturation exposure were more oriented toward ethnic culture and to a greater extent experienced impaired mental health when compared with the sample with more acculturation. Most prevalent among the students (34.2%) was a bicultural orientation, integrating both ethnic and mainstream culture. In general, acculturation orientation was not associated with quantitative measures of depression or anxiety. The qualitative analysis revealed agency and cultural identity to be pivotal factors in the process of reproducing culture and negotiating cultural change |

| Mixed population | Structured data collection and IDIs | ||||

| Jeffrey GS et al., 2016[38] | Central India | Understand human displacement’s mental health toll as well as the displacement-related changes that help explain such emotional suffering | Cross-sectional | Heads of the households (159) from Mazira and Behruda villages | Loss of homeland compromises mental health in all aspects |

| Sahariyas | Ethnographic information and semi structured interview | ||||

| Raina et al., 2016[45] | Himachal Pradesh Not mentioned |

Explore the feasibility of using EASI as an alternative to HMSE and its modifications | Cross-sectional | 60 years and above age (2000). Secondary data analysis | As the scores on EASI rise, the scores on HMSE fall both pointing to identification of the same clinical diagnosis, that is, dementia. EASI may be used as alternative to mental state examination |

| Lakhan et al., 2016[30] | Chikalia, Madhya Pradesh | Prevalence of Down’s syndrome in a tribal population and (2) its comorbidity with ID in tribal population | ST mothers (2767) | All mothers of all identified DS children were in young age (18-24 years) when they had babies with DS | |

| Not mentioned | Screening for ID (intellectual through a household survey). Identified cases evaluated by therapists in IDs for diagnosis | ||||

| Janakiram et al., 2016[22] | Tribal colonies in Kalapetta, Kerala | Find out dependency of tobacco use in indigenous population of Waynad, India | Cross-sectional | 103, individuals above age of 15 years in four colonies of Kalapetta | Prevalence of tobacco use in this population was 73.8%. Majority of them (92%) use smokeless forms of tobacco. The mean score for nicotine dependency was 3.85% for smoked tobacco and 4.61% was for smokeless tobacco which denote moderate dependency of tobacco use. Average age of onset of tobacco use was 16.41 years for smoked and 17.53 years for smokeless forms |

| Adivasis | A structured questionnaire, modified and adapted from NIMHANS - the tobacco cessation questionnaire - was done | ||||

| Ali et al., 2016[27] | Ranchi, Jharkhand | Find out the mental health status (emotional, hyperactivity, relationships and conduct problems and pro-social behavior’s) among school-going tribal adolescents | Cross-sectional study | Males (780) in the age range of 13-17 years going to school, belonging to tribal community | Out of the total participants, 5.12% of the students had emotional symptoms, 9.61% had conduct problems, 4.23% had hyperactivity, and 1.41% had significant peer problems |

| Not mentioned | Semi structured sociodemographic data and strengths and difficulties questionnaire to assess the emotional and behavioral disorders were collected | ||||

| Maulik et al., 2017[14] | Andhra Pradesh | Understand the feasibility and acceptability of mental health service utilization in Remote areas using mobile technology Evaluation of the SMART Mental Health project in rural India |

Cross-sectional | Age >18 years (5007), participated in survey | Training was imparted to 21 ASHAs and 2 primary care doctors. 5007 of 5167 eligible individuals were screened, and 238 were |

| Koya | Development of mobile technology-based EDSS | Identified as being positive for CMDs and referred to the primary care doctors for further management | |||

| Interactive voice response system Stigma reduction campaign |

Out of the screened positive, 2 (0.8%) had previously utilized mental health services. During the intervention period, 30 (12.6%) visited the primary care doctor for further diagnosis and treatment, as advised. There was a significant reduction in the depression and anxiety scores between start and end of the intervention among those who had screened positive at the beginning | ||||

| Baseline household survey | Stigma and mental health awareness in the broader community improved during the project Intervention Postintervention |

CMD – Common mental disorder; BP – Blood pressure; SD – Standard deviation; PSSI – Permanent Shear Stability Index; SRF – Sundarbans reserve forest; IDIs – In-depth interviews; FGDs – Focus group discussions; FTND – Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; GHQ – General Health Questionnaire; MMSE – Mini–Mental State Examination; HMSE – Hindi Mental State Examination; NR – Not reported; EASI – Everyday Abilities Scale for India; SMART – Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment; EDSS – Expanded Disability Status Scale; ASHA – Accredited social health activist; ST – Scheduled Tribes; ID – Intellectual Disability, DS – Down Syndrome, NMR – Neonatal Mortality Rate

RESULTS

Search results

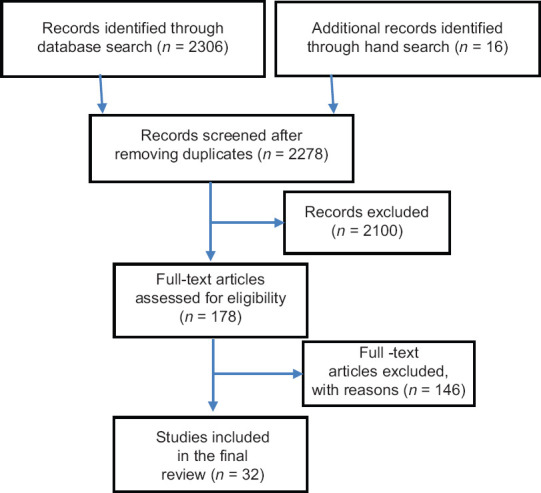

Our search retrieved 2306 records (which included hand-searched articles), of which after removing duplicates, title and abstracts of 2278 records were screened. Of these, 178 studies were deemed as potentially relevant and were reviewed in detail. Finally, we excluded 146 irrelevant studies and 32 studies were included in the review [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing search results

Quality of the included studies

Summary of quality assessment of the included studies is reported in [Table 2]. Overall, nine studies were of poor quality, twenty were of moderate quality, and three studies were of high quality. The CASP shows that out of the 32 studies, the sample size of 21 studies was not representative, sample size of 7 studies was not justified, risk factors were not identified in 28 studies, methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them in 24 studies, and nonresponse reasons were not addressed in 24 studies. The most common reasons for studies to be of poor-quality included sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; and methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them. Studies under the moderate quality did not have a representative sample; non-responders categories was not addressed; risk factors were not measured correctly; and methods used were not sufficiently described to allow the study to be replicated by other researchers.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the studies

| Author | Year | Instrument used | Score | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee et al.[47] | 1986 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Nandi et al.[41] | 1992 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Ganguly et al.[16] | 1995 | CASP | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Aparajita et al.[36] | 1996 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Chaturvedi et al.[18] | 2003 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Prabhakar and Manoharan[32] | 2005 | CASP | High | Sample size justified; sample is representative; nonresponse categories addressed; risk factors measured correctly; methods used were sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations discussed |

| Sushila et al.[25] | 2005 | CASP | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Hackett et al.[42] | 2007 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Giri et al.[40] | 2007 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Sobhnajan et al.[26] | 2007 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Chowdhury et al.[37] | 2008 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Tripathy et al.[35] | 2010 | CASP | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Mohindra et al.[19] | 2011 | CASP | High | Sample size justified; sample is representative; nonresponse categories addressed; risk factors measured correctly; methods used were sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations discussed |

| Sreeraj et al.[20] | 2012 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Yalsangi[34] | 2012 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Manimundaet al.[23] | 2012 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Renu et al.[28] | 2012 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Renu et al.[46] | 2012 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Singh et al.[24] | 2013 | AXIS | High | Sample size justified; sample is representative; nonresponse categories addressed; risk factors measured correctly; methods used were sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations discussed |

| Chaturvedi et al.[18] | 2013 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Raina et al.[43] | 2013 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Longkumer et al.[23] | 2013 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Raina et al.[44] | 2014 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Nizamie et al.[31] | 2015 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Nimgaonkar and Menon.[33] | 2015 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Ozer[39] | 2015 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Jeffrey G S et al.[37] | 2016 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Raina et al.[45] | 2016 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Lakhan et al.[30] | 2016 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

| Janakiram et al.[22] | 2016 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified; sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them; limitations not discussed |

| Ali et al.[27] | 2016 | AXIS | Poor | Sample size not justified and is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were insufficiently described; limitations not discussed |

| Maulik et al.[14] | 2017 | AXIS | Moderate | Sample is not representative; nonresponse categories not addressed; risk factors not measured correctly; methods used were not sufficiently described to repeat them |

The included studies covered three broad categories: alcohol and substance use disorders, CMD (depression, anxiety, stress, and suicide risk), socio-cultural aspects, and access to mental health services.

Alcohol and substance use disorders

Five studies reviewed the consumption of alcohol and opioid. In an ethnographic study conducted in three western districts in Rajasthan, 200 opium users were interviewed. Opium consumption was common among both younger and older males during nonharvest seasons. The common causes for using opium were relief of anxiety related to crop failure due to drought, stress, to get a high, be part of peers, and for increased sexual performance.[16]

In a study conducted in Arunachal Pradesh involving a population of more than 5000 individuals, alcohol use was present in 30% and opium use in about 5% adults.[17] Contrary to that study, in Rajasthan, the prevalence of opium use was more in women and socioeconomic factors such as occupation, education, and marital status were associated with opium use.[16] The prevalence of opium use increased with age in both sexes, decreased with increasing education level, and increased with employment. It was observed that wages were used to buy opium. In the entire region of Chamlang district of Arunachal Pradesh, female substance users were almost half of the males among ST population.[17] Types of substance used were tobacco, alcohol, and opium. Among tobacco users, oral tobacco use was higher than smoking. The prevalence of tobacco use was higher among males, but the prevalence of alcohol use was higher in females, probably due to increased access to homemade rice brew generally prepared by women. This study is unique in terms of finding a strong association with religion and culture with substance use.[18]

Alcohol consumption among Paniyas of Wayanad district in Kerala is perceived as a male activity, with many younger people consuming it than earlier. A study concluded that alcohol consumption among them was less of a “choice” than a result of their conditions operating through different mechanisms. In the past, drinking was traditionally common among elderly males, however the consumption pattern has changed as a significant number of younger men are now drinking. Drinking was clustered within families as fathers and sons drank together. Alcohol is easily accessible as government itself provides opportunities. Some employers would provide alcohol as an incentive to attract Paniya men to work for them.[19]

In a study from Jharkhand, several ST community members cited reasons associated with social enhancement and coping with distressing emotions rather than individual enhancement, as a reason for consuming alcohol. Societal acceptance of drinking alcohol and peer pressure, as well as high emotional problems, appeared to be the major etiology leading to higher prevalence of substance dependence in tribal communities.[20] Another study found high life time alcohol use prevalence, and the reasons mentioned were increased poverty, illiteracy, increased stress, and peer pressure.[21] A household survey from Chamlang district of Arunachal Pradesh revealed that there was a strong association between opium use and age, occupation, marital status, religion, and ethnicity among both the sexes of STs, particularly among Singhpho and Khamti.[15] The average age of onset of tobacco use was found to be 16.4 years for smoked and 17.5 years for smokeless forms in one study.[22]

Common mental disorders and socio-cultural aspects

Suicide was more common among Idu Mishmi in Roing and Anini districts of Arunachal Pradesh state (14.2%) compared to the urban population in general (0.4%–4.2%). Suicides were associated with depression, anxiety, alcoholism, and eating disorders. Of all the factors, depression was significantly high in people who attempted suicide.[24] About 5% out of 5007 people from thirty villages comprising ST suffered from CMDs in a study from West Godavari district in rural Andhra Pradesh. CMDs were defined as moderate/severe depression and/or anxiety, stress, and increased suicidal risk. Women had a higher prevalence of depression, but this may be due to the cultural norms, as men are less likely to express symptoms of depression or anxiety, which leads to underreporting. Marital status, education, and age were prominently associated with CMD.[14] In another study, gender, illiteracy, infant mortality in the household, having <3 adults living in the household, large family size with >four children, morbidity, and having two or more life events in the last year were associated with increased prevalence of CMD.[24] Urban and rural ST from the same community of Bhutias of Sikkim were examined, and it was found that the urban population experienced higher perceived stress compared to their rural counterparts.[25] Age, current use of alcohol, poor educational status, marital status, social groups, and comorbidities were the main determinants of tobacco use and nicotine dependence in a study from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[22] A study conducted among adolescents in the schools of rural areas of Ranchi district in Jharkhand revealed that about 5% children from the ST communities had emotional symptoms, 9.6% children had conduct problems, 4.2% had hyperactivity, and 1.4% had significant peer problems.[27] A study conducted among the female school teachers in Jharkhand examined the effects of stress, marital status, and ethnicity upon the mental health of school teachers. The study found that among the three factors namely stress, marital status, and ethnicity, ethnicity was found to affect mental health of the school teachers most. It found a positive relationship between mental health and socioeconomic status, with an inverse relationship showing that as income increased, the prevalence of depression decreased.[28] A study among Ao-Nagas in Nagaland found that 74.6% of the population attributed mental health problems to psycho-social factors and a considerable proportion chose a psychiatrist or psychologist to overcome the problem. However, 15.4% attributed mental disorders to evil spirits. About 47% preferred to seek treatment with a psychiatrist and 25% preferred prayers. Nearly 10.6% wanted to seek the help of both the psychiatrist and prayer group and 4.4% preferred traditional healers.[28,29] The prevalence of Down syndrome among the ST in Chikhalia in Barwani district of Madhya Pradesh was higher than that reported in overall India. Three-fourth of the children were the first-born child. None of the parents of children with Down syndrome had consanguineous marriage or a history of Down syndrome, intellectual disability, or any other neurological disorder such as cerebral palsy and epilepsy in preceding generations. It is known that tribal population is highly impoverished and disadvantaged in several ways and suffer proportionately higher burden of nutritional and genetic disorders, which are potential factors for Down syndrome.[30]

Access to mental health-care services

In a study in Ranchi district of Jharkhand, it was found that most people consulted faith healers rather than qualified medical practitioners. There are few mental health services in the regions.[31] Among ST population, there was less reliance and belief in modern medicine, and it was also not easily accessible, thus the health-care systems must be more holistic and take care of cultural and local health practices.[32]

The Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment (SMART) Mental Health project was implemented in thirty ST villages in West Godavari District of Andhra Pradesh. The key objectives were to use task sharing, training of primary health workers, implementing evidence-based clinical decision support tools on a mobile platform, and providing mental health services to rural population. The study included 238 adults suffering from CMD. During the intervention period, 12.6% visited the primary health-care doctors compared to only 0.8% who had sought any care for their mental disorders prior to the intervention. The study also found a significant reduction in the depression and anxiety scores at the end of intervention and improvements in stigma perceptions related to mental health.[14] A study in Gudalur and Pandalur Taluks of Nilgiri district from Tamil Nadu used low cost task shifting by providing community education and identifying and referring individuals with psychiatric problems as effective strategies for treating mental disorders in ST communities. Through the program, the health workers established a network within the village, which in turn helped the patients to interact with them freely. Consenting patients volunteered at the educational sessions to discuss their experience about the effectiveness of their treatment. Community awareness programs altered knowledge and attitudes toward mental illness in the community.[33] A study in Nilgiri district, Tamil Nadu, found that the community had been taking responsibility of the patients with the system by providing treatment closer to home without people having to travel long distances to access care. Expenses were reduced by subsidizing the costs of medicine and ensuring free hospital admissions and referrals to the people.[34] A study on the impact of gender, socioeconomic status, and age on mental health of female factory workers in Jharkhand found that the ST women were more likely to face stress and hardship in life due to diverse economic and household responsibilities, which, in turn, severely affected their mental health.[35] Prevalence of mental health morbidity in a study from the Sunderbans delta found a positive relation with psycho-social stressors and poor quality of life. The health system in that remote area was largely managed by “quack doctors” and faith healers. Poverty, illiteracy, and detachment from the larger community helped reinforce superstitious beliefs and made them seek both mental and physical health care from faith healers.[36] In a study among students, it was found that children had difficulties in adjusting to both ethnic and mainstream culture.[27] Low family income, inadequate housing, poor sanitation, and unhealthy and unhygienic living conditions were some environmental factors contributing to poor physical and mental growth of children. It was observed that children who did not have such risk factors maintained more intimate relations with the family members. Children belonging to the disadvantaged environment expressed their verbal, emotional need, blame, and harm avoidances more freely than their counterparts belonging to less disadvantaged backgrounds. Although disadvantaged children had poor interfamilial interaction, they had better relations with the members outside family, such as peers, friends, and neighbors.[37] Another study in Jharkhand found that epilepsy was higher among ST patients compared to non-ST patients.[31] Most patients among the ST are irregular and dropout rates are higher among them than the non-ST patients. Urbanization per se exerted no adverse influence on the mental health of a tribal community, provided it allowed preservation of ethnic and cultural practices. Women in the ST communities were less vulnerable to mental illness than men. This might be a reflection of their increased responsibilities and enhanced gender roles that are characteristic of women in many ST communities.[38] Data obtained using culturally relevant scales revealed that relocated Sahariya suffer a lot of mental health problems, which are partially explained by livelihood and poverty-related factors. The loss of homes and displacement compromise mental health, especially the positive emotional well-being related to happiness, life satisfaction, optimism for future, and spiritual contentment. These are often not overcome even with good relocation programs focused on material compensation and livelihood re-establishment.[39]

DISCUSSION

This systematic review is to our knowledge the first on mental health of ST population in India. Few studies on the mental health of ST were available. All attempts including hand searching were made to recover both published peer-reviewed papers and reports available on the website. Though we searched gray literature, it may be possible that it does not capture all articles. Given the heterogeneity of the papers, it was not possible to do a meta-analysis, so a narrative review was done.

The quality of the studies was assessed by CASP. The assessment shows that the research conducted on mental health of STs needs to be carried out more effectively. The above mentioned gaps need to be filled in future research by considering the resources effectively while conducting the studies.

Mental and substance use disorders contribute majorly to the health disparities. To address this, one needs to deliver evidence-based treatments, but it is important to understand how far these interventions for the indigenous populations can incorporate cultural practices, which are essential for the development of mental health services.[30] Evidence has shown a disproportionate burden of suicide among indigenous populations in national and regional studies, and a global and systematic investigation of this topic has not been undertaken to date. Previous reviews of suicide epidemiology among indigenous populations have tended to be less comprehensive or not systematic, and have often focused on subpopulations such as youth, high-income countries, or regions such as Oceania or the Arctic.[46] The only studies in our review which provided data on suicide were in Idu Mishmi, an isolated tribal population of North-East India, and tribal communities from Sunderban delta.[24,37] Some reasons for suicide in these populations could be the poor identification of existing mental disorders, increased alcohol use, extreme poverty leading to increased debt and hopelessness, and lack of stable employment opportunities.[24,37] The traditional consumption pattern of alcohol has changed due to the reasons associated with social enhancement and coping with distressing emotions rather than individual enhancement.[19,20]

Faith healers play a dominant role in treating mental disorders. There is less awareness about mental health and available mental health services and even if such knowledge is available, access is limited due to remoteness of many of these villages, and often it involves high out-of-pocket expenditure.[35] Practitioners of modern medicine can play a vital role in not only increasing awareness about mental health in the community, but also engaging with faith healers and traditional medicine practitioners to help increase their capacity to identify and manage CMDs that do not need medications and can be managed through simple “talk therapy.” Knowledge on symptoms of severe mental disorders can also help such faith healers and traditional medicine practitioners to refer cases to primary care doctors or mental health professionals.

Remote settlements make it difficult for ST communities to seek mental health care. Access needs to be increased by using solutions that use training of primary health workers and nonphysician health workers, task sharing, and technology-enabled clinical decision support tools.[3] The SMART Mental Health project was delivered in the tribal areas of Andhra Pradesh using those principles and was found to be beneficial by all stakeholders.[14]

Given the lack of knowledge about mental health problems among these communities, the government and nongovernmental organizations should collect and disseminate data on mental disorders among the ST communities. More research funding needs to be provided and key stakeholders should be involved in creating awareness both in the community and among policy makers to develop more projects for ST communities around mental health. Two recent meetings on tribal mental health – Round Table Meeting on Mental Health of ST Populations organized by the George Institute for Global Health, India, in 2017,[51] and the First National Conference on Tribal Mental Health organized by the Indian Psychiatric Society in Bhubaneswar in 2018 – have identified some key areas of research priority for mental health in ST communities. A national-level policy on mental health of tribal communities or population is advocated which should be developed in consultation with key stakeholders. The Indian Psychiatric Society can play a role in coordinating research activities with support of the government which can ensure regular monitoring and dissemination of the research impact to the tribal communities. There is a need to understand how mental health symptoms are perceived in different ST communities and investigate the healing practices associated with distress/disaster/death/loss/disease. This could be done in the form of cross-sectional or cohort studies to generate proper evidence which could also include the information on prevalence, mental health morbidity, and any specific patterns associated with a specific disorder. Future research should estimate the prevalence of mental disorders in different age groups and gender, risk factors, and the influence of modernization. Studies should develop a theoretical model to understand mental disorders and promote positive mental health within ST communities. Studies should also look at different ST communities as cultural differences exist across them, and there are also differences in socioeconomic status which impact on ability to access care.

Research has shown that the impact and the benefits are amplified when research is driven by priorities that are identified by indigenous communities and involve their active participation; their knowledge and perspectives are incorporated in processes and findings; reporting of findings is meaningful to the communities; and indigenous groups and other key stakeholders are engaged from the outset.[47] Future research in India on ST communities should also adhere to these broad principles to ensure relevant and beneficial research, which have direct impact on the mental health of the ST communities.

There is also a need to update literature related to mental health of ST population continuously; develop culturally appropriate validated instruments to measure mental morbidity relevant to ST population; and use qualitative research to investigate the perceptions and barriers for help-seeking behavior.[48]

CONCLUSION

The current review helps not only to collate the existing literature on the mental health of ST communities but also identify gaps in knowledge and provide some indications about the type of research that should be funded in future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gururaj G, Girish N, Isaac MK. Mental. Neurological and Substance abuse disorders: Strategies towards a systems approach. Burden of Disease in India; Equitable development – Healthy future New Delhi, India. National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Math SB, Srinivasaraju R. Indian Psychiatric epidemiological studies: Learning from the past. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S95–103. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tewari A, Kallakuri S, Devarapalli S, Jha V, Patel A, Maulik PK. Process evaluation of the systematic medical appraisal, referral and treatment (SMART) mental health project in rural India. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:385. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1525-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India. Report of the High Level Committee on Socio-economic, Health and Educational Status of Tribal Communities of India. New Delhi: Government of India; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Census of India. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Institute for Population Sciences and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2001-Mental Health: New Understanding. New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Report of the Expert Committee on Tribal Health: Tribal Health in India – Bridging the Gap and a Roadmap for the Future. New Delhi: Government of India; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Government of India, Rural Health Statistics 2016-17. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Statistics Division. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T. Common mental disorders and disability across cultures. Results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA. 1994;272:1741–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.22.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M INDIGO Study Group. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373:408–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong G, Kermode M, Raja S, Suja S, Chandra P, Jorm AF. A mental health training program for community health workers in India: Impact on knowledge and attitudes. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maulik PK, Kallakuri S, Devarapalli S, Vadlamani VS, Jha V, Patel A. Increasing use of mental health services in remote areas using mobile technology: A pre-post evaluation of the SMART Mental Health project in rural India. J Global Health. 2017;7:1–13. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Systematic review Checklist. Available from: http://www.casp.uk.net/checklists. 2017 .

- 16.Ganguly KK, Sharma HK, Krishnamachari KA. An ethnographic account of opium consumers of Rajasthan (India): Socio-medical perspective. Addiction. 1995;90:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaturvedi HK, Mahanta J. Sociocultural diversity and substance use pattern in Arunachal Pradesh, India. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaturvedi HK, Mahanta J, Bajpai RC, Pandey A. Correlates of opium use: Retrospective analysis of a survey of tribal communities in Arunachal Pradesh, India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohindra KS, Narayana D, Anushreedha SS, Haddad S. Alcohol use and its consequences in South India: Views from a marginalised tribal population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:70–3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sreeraj VS, Prasad S, Khess CR, Uvais NA. Reasons for substance use: A comparative study of alcohol use in tribals and non-tribals. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:242–6. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.106020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janakiram C, Joseph J, Vasudevan S, Taha F, DeepanKumar CV, Venkitachalam R. Prevalence and dependancy of tobacco use in an indigenous population of Kerala, India. Oral Hygiene and Health. 2016;4 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manimunda SP, Benegal V, Sugunan AP, Jeemon P, Balakrishna N, Thennarusu K, et al. Tobacco use and nicotine dependency in a cross-sectional representative sample of 18,018 individuals in Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:515. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh PK, Singh RK, Biswas A, Rao VR. High rate of suicide attempt and associated psychological traits in an isolated tribal population of North-East India. J Affect Dis. 2013;151:673–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sushila J. Perception of Illness and Health Care among Bhils: A Study of Udaipur District in Southern Rajasthan. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobhanjan S, Mukhopadhyay B. Perceived psychosocial stress and cardiovascular risk: Observations among the Bhutias of Sikkim, India. Stress Health. 2008;24:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali A, Eqbal S. Mental Health status of tribal school going adolescents: A study from rural community of Ranchi, Jharkhand. Telangana J Psychiatry. 2016;2:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diwan R. Stress and mental health of tribal and non tribal female school teachers in Jharkhand, India. Int J Sci Res Publicat. 2012;2:2250–3153. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longkumer I, Borooah PI. Knowledge about attitudes toward mental disorders among Nagas in North East India. IOSR J Humanities Soc Sci. 2013;15:41–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakhan R, Kishore MT. Down syndrome in tribal population in India: A field observation. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016;7:40–3. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.172167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nizamie HS, Akhtar S, Banerjee S, Goyal N. Health care delivery model in epilepsy to reduce treatment gap: WHO study from a rural tribal population of India. Epilepsy Res Elsevier. 2009;84:146–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prabhakar H, Manoharan R. The Tribal Health Initiative model for healthcare delivery: A clinical and epidemiological approach. Natl Med J India. 2005;18:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nimgaonkar AU, Menon SD. A task shifting mental health program for an impoverished rural Indian community. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;16:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yalsangi M. Evaluation of a Community Mental Health Programme in a Tribal Area- South India. Achutha Menon Centre For Health Sciences Studies, Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Working Paper No 12. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tripathy P, Nirmala N, Sarah B, Rajendra M, Josephine B, Shibanand R, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women's groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1182–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aparajita C, Anita KM, Arundhati R, Chetana P. Assessing Social-support network among the socio culturally disadvantaged children in India. Early Child Develop Care. 1996;121:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chowdhury AN, Mondal R, Brahma A, Biswas MK. Eco-psychiatry and environmental conservation: Study from Sundarban Delta, India. Environ Health Insights. 2008;2:61–76. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeffery GS, Chakrapani U. Eco-psychiatry and Environmental Conservation: Study from Sundarban Delta, India. Working Paper- Research Gate.net. 2016 Sep [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozer S. Acculturation, adaptation, and mental health among Ladakhi College Students a mixed methods study of an indigenous population. J Cross Cultl Psychol. 2015;46:435–53. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giri DK, Chaudhary S, Govinda M, Banerjee A, Mahto AK, Chakravorty PK. Utilization of psychiatric services by tribal population of Jharkhand through community outreach programme of RINPAS. Eastern J Psychiatry. 2007;10:25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Chowdhury AN, Banerjee T, Boral GC, Sen B. Urbanization and mental morbidity in certain tribal communities in West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:334–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hackett RJ, Sagdeo D, Creed FH. The physical and social associations of common mental disorder in a tribal population in South India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:712–5. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raina SK, Raina S, Chander V, Grover A, Singh S, Bhardwaj A. Development of a cognitive screening instrument for tribal elderly population of Himalayan region in northern India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013;4:147–53. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.112744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raina SK, Raina S, Chander V, Grover A, Singh S, Bhardwaj A. Identifying risk for dementia across populations: A study on the prevalence of dementia in tribal elderly population of Himalayan region in Northern India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:640–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.120494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raina SK, Chander V, Raina S, Kumar D. Feasibility of using everyday abilities scale of India as alternative to mental state examination as a screen in two-phase survey estimating the prevalence of dementia in largely illiterate Indian population. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:459–61. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diwan R. Mental health of tribal male-female factory workers in Jharkhand. IJAIR. 2012;2278:234–42. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banerjee T, Mukherjee SP, Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Mukherjee A, Sen B, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in an urbanized tribal (Santal) community - A field survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:243–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leske S, Harris MG, Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Baxter AJ, Logan JM, et al. Systematic review of interventions for Indigenous adults with mental and substance use disorders in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:1040–54. doi: 10.1177/0004867416662150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pollock NJ, Naicker K, Loro A, Mulay S, Colman I. Global incidence of suicide among Indigenous peoples: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2018;16:145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1115-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silburn K, et al. Evaluation of the Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health (Australian institute for primary care, trans.) Melbourne: LaTrobe University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 51.George Institute for Global Health. Roundtable Meeting on Mental Health of Scheduled Tribe Populations. 2017. Available from: https://www.georgeinstitute.org.in/projects/areas/mental-health-of-scheduled-tribepopulations-in-india .